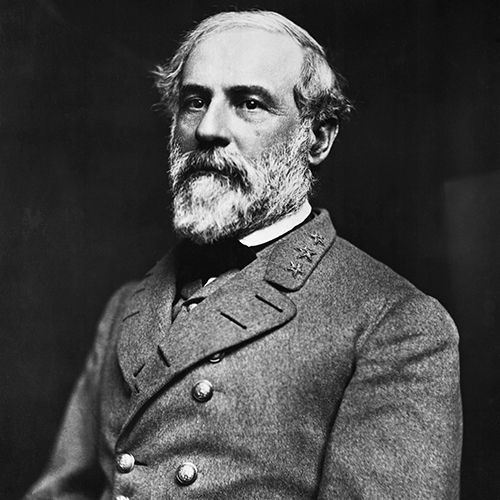

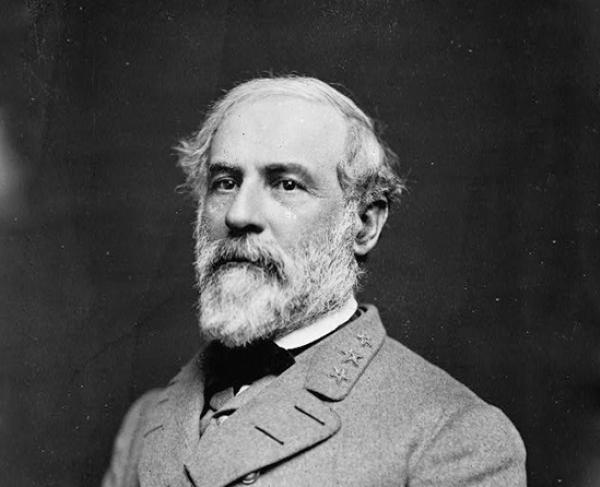

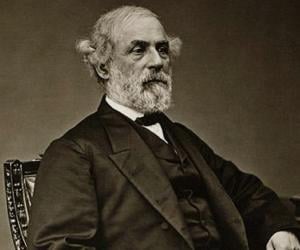

Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee was the leading Confederate general during the U.S. Civil War and has been venerated as a heroic figure in the American South.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Who Was Robert E. Lee?

Robert E. Lee became military prominence during the U.S. Civil War, commanding his home state's armed forces and becoming general-in-chief of the Confederate troops toward the end of the conflict. Though the Union won the war, Lee earned renown as a military tactician for scoring several significant victories on the battlefield. He became president of Washington College and, renamed Washington and Lee University after he died in 1870.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Robert Edward Lee BORN: January 19, 1807 DIED: October 12, 1870 BIRTHPLACE: Stratford, Virginia SPOUSE: Mary Custis (1831-1870) CHILDREN: George Washington Custis, William “Rooney,” Robert Jr, Mary, Anne, Eleanor Agnes, and Mildred ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Capricorn

Early Years

A Confederate general who led southern forces against the Union Army in the U.S. Civil War, Robert Edward Lee was born on Jan. 19, 1807, at his family home of Stratford Hall in northeastern Virginia.

Lee saw himself as an extension of his family's greatness. At 18, he enrolled at West Point Military Academy, where he put his drive and serious mind to work. He placed second in his graduating class after four spotless years without a demerit and wrapped up his studies with perfect scores in artillery, infantry, and cavalry.

Wife and Children

After graduating from West Point, Lee married Mary Custis, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington (from her first marriage before meeting George Washington) in 1831. The couple wed on Mary Custis’s family plantation in Arlington, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C. They would make the estate their primary home for the next 30 years. In 1857, Mary inherited the Arlington plantation outright following her father’s death. However, after the outbreak of the Civil War, Union troops occupied the plantation, and the federal government seized the land. In 1864, the government began constructing a new national cemetery to bury and honor the war’s military dead. After that, the former Custis/Lee home was transformed into one of the most hallowed places in American history— Arlington National Cemetery .

Together, they had seven children: four daughters (Mary, Annie, Agnes, and Mildred) and three sons (Custis, Rooney, and Rob) who followed their father to serve in the Confederate Army during the Civil War.

Early Military Career

While Mary and the children spent their lives on Mary's father's plantation, Lee stayed committed to his military obligations. His loyalties moved him around the country, from Savannah to St. Louis to New York.

In 1846, Lee got the chance he had been waiting for his whole military career when the United States went to war with Mexico. Serving under General Winfield Scott, Lee distinguished himself as a brave battle commander and a brilliant tactician. In the aftermath of the U.S. victory over its neighbor, Lee was held up as a hero. Scott showered Lee with particular praise, saying that if the United States went into another war, the government should consider taking out a life insurance policy on the commander.

But life away from the battlefield proved difficult for Lee to handle. He struggled with the mundane tasks associated with his work and life. For a time, he returned to his wife's family's plantation to manage the estate following the death of his father-in-law. The property had fallen under hard times, and for two long years, he tried to make it profitable again.

Robert E. Lee and Slavery

Lee did not own slaves in his youth, but he and Mary Custis Lee inherited enslaved people from both his mother and her father, and it’s believed Lee himself owned between 10-15 enslaved people during his lifetime. His racial attitudes reflected much of his background, and while he wrote to Mary about the moral and political evils of slavery, he held views of white superiority. He saw slavery as necessary to maintain order between races. He opposed abolitionism, which he saw as a northern effort to inflict political will on the South.

When Lee’s father-in-law died in 1857, Lee became executor of his estate, tasked with managing the Arlington plantation. During this period, despite his father-in-law’s decree that his slaves be freed within five years of his death, Lee was accused of being a cruel and harsh overseer, with reports of beatings of some of the 200 enslaved people under his control, particularly those who had tried to escape.

In late 1862, to fulfill the terms of his father-in-law’s will, Lee signed deeds freeing some 150 of the enslaved workers at Arlington and other Custis plantations. Just a few months later, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in January 1863, freeing enslaved peoples in Confederate territory. Despite the Proclamation, Lee, during his Gettysburg campaign later that year, continued his practice of seizing freed Blacks in Union territory to be sent into slavery in the South. Towards the end of the war, with the Confederacy desperate for recruits, he supported the idea of allowing enslaved peoples to serve in the army in exchange for their freedom. Still, the war ended before the policy was enacted.

Confederate Leader

In October 1859, Lee was summoned to put an end to an enslaved person insurrection led by John Brown at Harper's Ferry. Lee's orchestrated attack took just an hour to end the revolt, and his success put him on a shortlist of names to lead the Union Army should the nation go to war.

But Lee's commitment to the Army was superseded by his commitment to Virginia. After turning down an offer from President Abraham Lincoln to command the Union forces, Lee resigned from the military and returned home. While Lee had misgivings about centering a war on the slavery issue, after Virginia voted to secede from the nation on April 17, 1861, Lee agreed to help lead the Confederate forces.

Over the next year, Lee again distinguished himself on the battlefield. On June 1, 1862, he took control of the Army of Northern Virginia and drove back the Union Army during the Seven Days Battles near Richmond. In August of that year, he gave the Confederacy a crucial victory at Second Manassas (also known as the Second Battle of Bull Run).

But not all went well. He courted disaster when he tried to cross the Potomac at the Battle of Antietam on Sept. 17, barely escaping the site of the bloodiest single-day skirmish of the war, which left some 22,000 combatants dead.

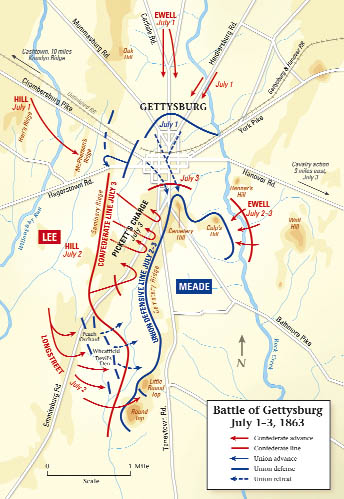

From July 1-3, 1863, Lee's forces suffered another round of heavy casualties in Pennsylvania. The three-day stand-off, known as the Battle of Gettysburg , wiped out a vast chunk of Lee's army, halting his invasion of the North while helping to turn the tide for the Union.

By the fall of 1864, Union General Ulysses S. Grant had gained the upper hand, decimating much of Richmond, the Confederacy's capital, and Petersburg. By early 1865, the fate of the war was clear, a fact driven home on April 2 when Lee was forced to abandon Richmond. A week later, a reluctant and despondent Lee surrendered to Grant at a private home in Appomattox, Virginia.

"I suppose there is nothing for me to do but go and see General Grant," he told an aide. "And I would rather die a thousand deaths."

Final Years and Death

Saved from being hanged as a traitor by a forgiving Lincoln and Grant, Lee returned to his family in April 1865. He eventually accepted a job as president of Washington College in western Virginia and devoted his efforts toward boosting the institution's enrollment and financial support.

In late September 1870, Lee suffered a massive stroke. He died at his home in Lexington, Virginia, surrounded by family, on Oct. 12. He was buried in a chapel at nearby Washington College. Shortly afterward, the college was renamed Washington and Lee University.

Disputed Legacy and Statue

In the decades after the Civil War, sympathizers regarded Lee as a heroic figure of the South. Several monuments to the late general sprung up before the end of the 19th century, notably in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Dallas, Texas. Lee’s birthday is commemorated in several southern states. Until 2020, Lee-Jackson Day (also commemorating Civil War General Stonewall Jackson ) was celebrated each January in Virginia. Texas celebrates Lee on his Jan. 19th birthday as part of Confederate Heroes Day. Mississippi and Alabama celebrate a combined state holiday in late January honoring both Lee and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr , while Florida commemorates Robert E. Lee Day as an unofficial state holiday.

Lee's complicated legacy became part of the culture wars that engulfed the country more than a century later. While some sought to have statues of Confederate leaders removed from public view, others argued that doing so represented an attempt to erase history. In 2017, after the City Council of Charlottesville, Virginia, voted to move a Lee statue from a park, Charlottesville became the site of several protests and counter-protests; in August, numerous demonstrators clashed, resulting in one death and 19 injuries.

In late October 2017, President Donald Trump 's chief of staff, John Kelly, further fanned the flames of the controversy with his appearance on Fox News. Addressing the topic of a Virginia church's decision to remove plaques that honored both Lee and Washington, Kelly called the Confederate general an "honorable man" and pointed to the "lack of an ability to compromise" as the cause of the Civil War. This analysis drew the ire of opponents.

Robert E. Lee in Movies

Robert E. Lee has been the subject of numerous biographies, documentaries, and novels, including several “alternative history” books depicting the South as winning the Civil War. Among the most popular books featuring Lee is a trilogy of novels . The first, written by Jeffrey Shaara, was the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Killer Angels, which became the basis for the 1993 film Gettysburg , starring Martin Sheen as Lee. After Jeffrey’s death, his son Michael completed the trilogy, publishing Gods and Generals and The Last Full Measure , the former of which was adapted into a 2003 film of the same name, starring Robert Duvall—himself a descendant of Robert E. Lee—as the famed general.

- I suppose there is nothing for me to do but go and see General Grant. And I would rather die a thousand deaths.

- Do your duty in all things. You cannot do more; you should never wish to do less.

- I cannot trust a man to control others who cannot control himself.

- Whiskey: I like it, I always did, and that is the reason I never use it.

- Obedience to lawful authority is the foundation of manly character.

- The education of a man is never completed until he dies.

- Never do a wrong thing to make a friend or keep one.

- You cannot be a true man until you learn to obey.

- In this enlightened age, there are few, I believe, but what will acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil in any country.

- You see what a poor sinner I am and how unworthy to possess what was given me; for that reason, it has been taken away.

- Everybody kind of perceives me as being angry. It's not anger, it's motivation.

- It is good that war is so horrible, or we might grow to like it.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Civil War Figures

The 13 Most Cunning Military Leaders

Clara Barton

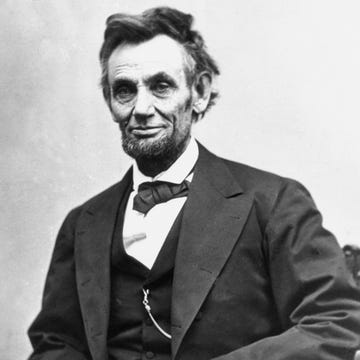

Abraham Lincoln

The Story of President Ulysses S. Grant’s Arrest

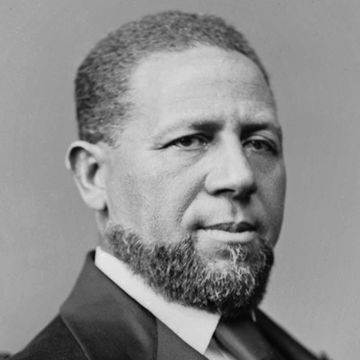

Hiram R. Revels

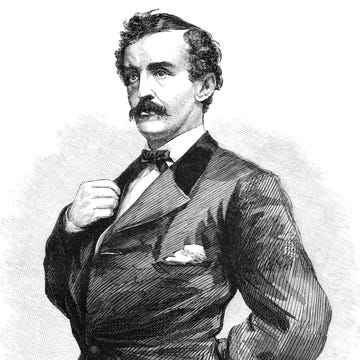

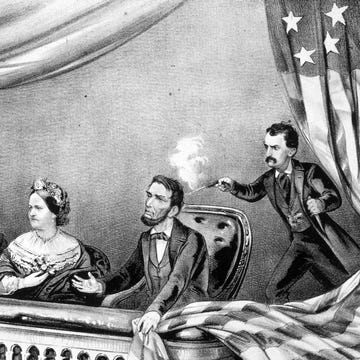

John Wilkes Booth

The Final Days of Abraham Lincoln

Stonewall Jackson

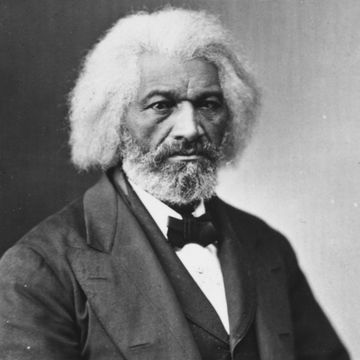

Frederick Douglass

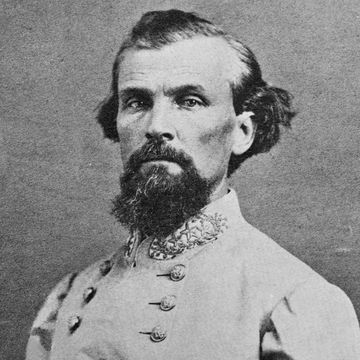

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Robert Edward Lee

January 19, 1807–October 12, 1870

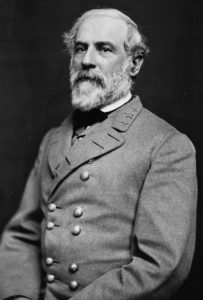

Robert E. Lee was a prominent Confederate army officer who commanded the Army of Northern Virginia throughout most of the Civil War. He also served as General-in-Chief of Confederate forces near the end of the war.

Robert E. Lee was a prominent U.S. Army officer before the Civil War. When Virginia seceded from the Union, he resigned from his position and accepted the leadership of the Army of Northern Virginia. Near the end of the Civil War, he was named General-in-Chief of Confederate forces. Image Source: Wikipedia.

Early Life and Career of Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was born on January 19, 1807, at Stratford, a family plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was the fifth child of Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee and Ann Hill Carter Lee. Lee’s father was a Revolutionary War hero, a delegate to the Continental Congress, the Governor of Virginia from 1791 to 1794, and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. Despite his military and political renown, the Panic of 1796-1797 financially ruined the elder Lee and by 1809 he spent a year in debtor’s prison. After his release, Lee moved his family to Alexandria, Virginia. While living there, Robert attended local schools. In 1812, Lee’s father traveled to the West Indies and never returned, dying there in 1818. Lee’s mother had to raise her children with the help of relatives.

U.S. Military Academy Cadet

In 1824, Lee’s uncle, William Henry Fitzhugh, secured an appointment for Lee to the United States Military Academy. Lee entered the academy in 1825, graduating second in his class in 1829.

U.S. Army Officer

After graduation, Lee received a brevet commission as a second lieutenant in the Army Corps of Engineers. When Lee returned home while awaiting assignment, his mother died on July 26, 1829.

While at home, Lee also began courting Mary Custis, great-granddaughter of Martha Washington. In August, the army stationed Lee in Georgia. When he was home on leave a year later, Mary accepted Lee’s second marriage proposal, and the two wed on June 30, 1831. Later that year, the army transferred Lee to Fort Monroe in Virginia. For the next fifteen years, Lee was away from his family, performing various engineering duties for the army, including helping to establish the state line between Ohio and Michigan in 1835. During the period, Lee received promotions to second lieutenant in 1832, to first lieutenant in 1836, and to captain in 1838.

Mexican-American War

During the Mexican-American War (1846 to 1848) , Lee first served as an engineer under General John Wool, primarily laying out transportation routes. In 1847, he transferred to the staff of General Winfield Scott , who later stated that Lee was “the greatest soldier I ever saw in the field.” Lee served with distinction at the battles of Veracruz (March 1847) , Cerro Gordo (April 1847) , and Chapultepec (September 1847) , where he was wounded. Lee received a brevet promotion to major after the Battle of Cerro Gordo on April 18, 1847.

Superintendent of the United States Military Academy

After the Mexican-American War, Lee resumed his peacetime engineering duties with the army. In 1852, U.S. Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis appointed him superintendent of the United States Military Academy, where he served until 1855. In March 1855, the army promoted Lee to lieutenant colonel and gave him command of the recently formed 2nd U.S. Cavalry in Texas. His unit’s primary task was to subdue the Comanche Indians.

Slaveholder

While serving in Texas, Lee’s father-in-law, George Washington Custis, died in 1857, and Lee returned to Alexandria, Virginia to serve as executor of the estate. Custis’s will stipulated that his slaves receive their freedom within five years of his death. The slaves erroneously believed that they became free at the time of Custis’s death. Lee disagreed, and when some slaves attempted to escape, Lee began hiring them out, sometimes breaking up their families. Lee also filed legal petitions to keep Custis’s chattel enslaved indefinitely. Only when the courts denied his petitions did Lee consent to his father-in-law’s wishes and free his slaves.

John Brown’s Raid

In October 1859, President James Buchanan ordered Lee to lead a detachment of U.S. Marines to Harpers Ferry, Virginia to suppress a raid on the federal arsenal led by Ohioan and abolitionist John Brown . On October 18, after failed negotiations with Brown, Lee ordered his marines to storm the building housing the insurrectionists. In a matter of minutes, Lee’s men crushed the foray and captured Brown. Later that year, Lee stood guard at Brown’s execution on December 2, 1859.

Robert E. Lee During the Civil War

Confederate officer.

When the session crisis escalated after Abraham Lincoln’s election to the U.S. Presidency in 1860, Lee struggled with performing his sworn duty as a soldier and preserving his allegiance to his home state of Virginia. Serving as the acting head of the Department of Texas during the winter of 1860, Lee refused to cede federal property to local secessionists. In March of the following year, the War Department recalled Lee to Washington and promoted him to full colonel. On April 17, 1861, Virginia seceded from the Union. The next day, Lee declined a promotion to major general in the army being assembled to suppress the Southern insurrection. On April 20, he resigned from his commission in the U.S. Army. Three days later Lee accepted the command of Virginia’s forces.

Rocky Beginning

The first year of the Civil War was not kind to Lee or his reputation. In an uncoordinated attack hampered by rain, fog, and mountainous terrain, Lee’s forces were defeated at the Battle of Cheat Mountain (September 12 to 15) in western Virginia. Confederate President Jefferson Davis relieved Lee of his field command and sent him east to supervise the construction of coastal defenses in Georgia and the Carolinas. Davis then recalled Lee to Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital, where he served as a military adviser to the Confederate president. While acting in that capacity, Lee ordered his men to dig a network of defensive trenches around the Confederate capital. That operation earned him the derogatory sobriquet, “King of Spades.”

Army of Northern Virginia

The spring of 1862 marked a change in Lee’s military fortunes. By late May, Major General George McClellan had advanced the Federal Army of the Potomac to the outskirts of Richmond during his Peninsula Campaign . On June 1, General Joseph E. Johnston was severely wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines , and Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia .

Seven Days Battles

As McClellan planned for a siege of Richmond, Lee prepared to take the initiative. On June 25, he launched the first of six assaults on Federal troops in seven days, collectively known as the Seven Days Battles (June 25 to July 1, 1862) . Although the Battle of Gaines Mills was the only engagement in the series that produced a tactical Confederate victory, the offensive achieved Lee’s strategic objective of driving McClellan away from Richmond.

Northern Virginia Campaign

The Army of the Potomac retreated down the peninsula until U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and General-in-Chief-of-the-Army Henry Halleck recalled it on August 3, to support Major General Pope’s Army of Virginia operating near Washington. With McClellan’s army off of the peninsula, Lee turned his attention to Pope and scored a major victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 28 to 30, 1862) , opening the way for a Confederate invasion of the North.

Maryland Campaign

In September 1862, Lee moved the Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland. His Maryland Offensive had three major goals: relieve Virginia from the ravages of war, resupply his army through foraging in the North, and erode Northern morale enough to influence upcoming midterm elections in the North. McClellan dispatched the Army of the Potomac to Maryland to check Lee’s advance. The two armies met at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland. During the bloodiest day of fighting in the Civil War , the armies fought to a standoff. With his advance stalled and supplies running low, Lee withdrew to Virginia.

Fredericksburg Campaign

Disappointed with McClellan’s failure to pursue Lee’s retreating army, President Lincoln placed Ambrose Burnside in command of the Army of the Potomac on November 7, 1862, and urged him to mount an offensive. A reluctant Burnside crossed the Rappahannock River on December 12. The next day he ordered a disastrous series of frontal attacks against Lee’s well-positioned army near Fredericksburg, Virginia. After suffering more than 12,000 casualties , Burnside called off the offensive and re-crossed the river. Lee’s reputation and his army’s morale soared with the decisive Confederate victory at the Battle of Fredericksburg .

Chancellorsville Campaign

On January 26, 1863, Lincoln replaced Burnside with Major General Joseph (“Fighting Joe”) Hooker in his quest to find a Union officer who could out-general Lee. On April 27, Hooker led the Army of the Potomac back across the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers. He soon found one near Chancellorsville, Virginia on May 1. Outnumbering Lee’s army by a ratio of two to one , Hooker planned to use his numerical superiority to flank and entrap Lee’s army. However, Lee expected Hooker’s plan and split his outnumbered army to check the Federal flanking movements. After five days of intense fighting, Hooker withdrew his army from the field. Many consider the Battle of Chancellorsville to be the highlight of Lee’s military career. Once again he had fended off an advance by a much larger force, raising the already high morale of his army and prompting him to lobby for another invasion of the North.

Gettysburg Campaign

While Lee was defeating Hooker at Chancellorsville, Major General Ulysses S. Grant was besieging the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi on the Mississippi River. With Hooker’s army in retreat, many Confederate officials proposed sending some of Lee’s army west to relieve Vicksburg. Reluctant to reduce the number of troops protecting Virginia, Lee instead proposed another invasion of the North. With his stature at an all-time high, Lee’s views prevailed, and Jefferson Davis authorized him to launch another offensive.

On June 3, 1863, Lee began moving portions of his army northwest toward the Blue Ridge Mountains. The Rebels crossed the mountains and moved north through the Shenandoah Valley, capturing the Union garrison at Winchester, Virginia, in the Second Battle of Winchester (June 13 to 15, 1863) . Lee’s army then began moving into Maryland and Pennsylvania.

By that time, Hooker realized Lee’s movements and dispatched the Army of the Potomac to stop Lee’s advance. As the Federals sought to locate Lee’s forces, Hooker engaged in a heated dispute with his superiors and rashly offered to resign as commander of the Army of the Potomac. President Lincoln quickly accepted the resignation, and on June 28, he replaced Hooker with Major General George Meade. Three days later, Meade’s army engaged Lee at the Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg.

Battle of Gettysburg

From July 1 through July 3, the two armies clashed in the Battle of Gettysburg, the largest battle of the Civil War. Meade’s army arrived at Gettysburg ahead of the Rebels and secured the high ground on the first day of battle. Seeing that the Federals held the better ground, some of Lee’s lieutenant commanders, particularly James Longstreet , advised Lee to move the Confederate army around Gettysburg and face Meade’s army on another day at a place of the Rebels’ choosing. Fearing the effect that withdrawing might have on his army’s morale and, perhaps, placing too much stock in the illusory invincibility of the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee instead ordered ill-advised attacks against the Federal lines on the second and third days of the battle.

The results were catastrophic, particularly the assault on the Union center on July 3, later known as Pickett’s Charge . As Lee watched the remnants of his army return from the failed assault on Cemetery Ridge, he acknowledged, “It is all my fault.” That evening, the shattered Army of Northern Virginia began an arduous ten-day march back to Virginia, bringing Lee’s offensive to an ignominious end. Meade did not pursue Lee as he withdrew, and for the rest of the season, both armies were content to recuperate from the battle.

A Formidable Opponent

Meade’s failure to pursue Lee immediately after Gettysburg, coupled with his subsequent inaction in 1863, again prompted President Lincoln to find a general who would use the Union’s dominant resources to defeat the Confederacy. On February 29, 1864, President Lincoln signed legislation restoring the rank of lieutenant general in the United States Army. On March 2, the president nominated Ulysses S. Grant, conqueror of Vicksburg and champion of Chattanooga, for the post. Congress confirmed the nomination on the same day. On March 3, Lincoln summoned Grant to Washington. A week later, on March 10, the president issued an executive order appointing Grant as General-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States. On March 17, 1864, Grant issued General Orders, Number 12, taking command of the armies.

Overland Campaign

Grant immediately devised a plan to have all Union armies act in concert and then set his sights on defeating Lee. Making his headquarters with Meade’s Army of the Potomac, Grant launched his Overland Campaign in the spring, determined to go where Lee went. Although it took nearly a year, Grant’s strategy eventually prevailed. Against the better-equipped and much larger Union army , Lee held his own at the bloody Battles of the Wilderness (May 5-7, 1864) , Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21, 1864) , and Cold Harbor (May 31 – June 12, 1864) , endured a prolonged Siege at Petersburg (June 9, 1864 – March 25, 1865).

General-in-Chief of Confederate Forces

By the end of 1864, the Confederacy’s military plight had become dire. Grant had Lee’s army bottled up in Petersburg and William T. Sherman captured Savannah on December 21 after making Georgia howl during his notorious March to the Sea . As the situation worsened, Southerners began questioning President Jefferson Davis’s effectiveness as commander-in-chief. Opposition to Davis reached a crescendo on January 23, 1865, when the Confederation Congress enacted legislation creating the post of General-in-Chief of Confederate forces. A week later, the bedeviled president appointed Robert E. Lee to the post. On February 6, the Confederate War Department issued General Orders, No. 3 announcing Lee’s appointment. On February 9, Lee issued his first general order as General-in-Chief announcing that he had assumed the post.

Surrender at Appomattox Court House

The change in leadership had little effect on the outcome of the war. In March 1865, Lee led his beleaguered forces in a desperate escape attempt that ended at Appomattox Court House. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Grant.

Robert E. Lee’s Life After the Civil War

The Civil War lingered on for several weeks after the surrender at Appomattox Court House, but it was over for Lee. He returned to Richmond to reunite with his family. On October 2, 1865, Lee became president of Washington University in Lexington, Virginia. On the same day, Lee signed an amnesty oath, swearing his allegiance to the Constitution and to the United States. On December 25, 1868, President Andrew Johnson issued a proclamation that unconditionally pardoned those who “directly or indirectly” rebelled against the United States. Johnson’s pardon ensured that Lee would not face charges of treason. Still, the federal government did not restore Lee’s citizenship during his lifetime. On August 5, 1975, over 100 years after Lee’s death, President Gerald R. Ford signed legislation restoring Lee’s citizenship.

Lee served as president of Washington College for five years. During that time, he supported President Johnson’s Reconstruction plan and opposed the policies of so-called Radicals in Congress. He counseled compliance with federal authority but remained opposed to extending voting and civil rights to freed blacks.

Death of Robert E. Lee

On September 28, 1870, Lee suffered a stroke at his home in Lexington, Virginia. He died two weeks later on October 12. Lee’s remains were buried beneath the Lee Chapel on the campus of Washington University (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington.

- Written by Harry Searles

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Robert E. Lee

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 29, 2022 | Original: October 29, 2009

Robert E. Lee was a Confederate general who led the South’s attempt at secession during the Civil War . He challenged Union forces during the war’s bloodiest battles, including Antietam and Gettysburg , before surrendering to Union General Ulysses S. Grant in 1865 at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, marking the end of the devastating conflict that nearly split the United States.

WATCH: Civil War Journal on HISTORY Vault

Who Was Robert E. Lee?

Robert Edward Lee was born in Stratford Hall, a plantation in Virginia, on January 19, 1807, to a wealthy and socially prominent family. His mother, Anne Hill Carter, also grew up on a plantation and his father, Colonel Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, was descended from colonists and become a Revolutionary War leader and three-term governor of Virginia.

But the family hit hard times when Lee’s father made a series of bad investments that left him in debtors’ prison. He fled to the West Indies and died in 1818 while trying to return to Virginia when Lee was barely a teen.

With little money for his education, Lee went to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point for a military education. He graduated second in his class in 1829—and the following month he would lose his mother.

Did you know? Robert E. Lee graduated second in his class from West Point. He did not receive a single demerit during his four years at the academy.

Robert E. Lee's Children

After graduation, Lee’s military career quickly took off as he chose a position with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers .

A year later, he began courting a childhood connection, Mary Custis Washington. Given his father’s diminished reputation, Lee had to propose twice to win approval to wed Mary, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington and the step-great-granddaughter of President George Washington .

The pair married in 1831; Lee and his wife had seven children, including three sons, George, William and Robert, who followed him into the military to fight for the Confederate States during the Civil War.

As the couple were establishing their family, Lee frequently travelled with the military on engineering projects. He first distinguished himself in battle during the Mexican-American War under General Winfield Scott in the battles of Veracruz , Churubusco and Chapultepec. Scott once declared that Lee was “the very best soldier that I ever saw in the field.”

Was Robert E. Lee a Slave Owner?

Lee did not grow up on a large plantation, but his wife inherited an enslaved worker in 1857 from her father, George Washington Park Custis.

Lee executed his father-in-law's will, which included Arlington House near Washington, D.C., a poorly managed plantation with debts and nearly 200 enslaved people, whom Custis wanted freed within five years of his death.

As a result of his father-in-law, Lee became owner of hundreds of enslaved workers. While historical accounts vary, Lee’s treatment of the enslaved peoples was described as being so combative and harsh that it led to revolts.

Lee at Harpers Ferry

During the 1850s, tensions between the abolitionist movement and slave owners reached a boiling point, and the union of states was near a breaking point. Lee entered the fray by halting a raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859, capturing radical abolitionist John Brown and his followers.

The following year, Abraham Lincoln was elected president, prompting seven Southern states — Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas — to secede in protest. U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis became the president of the Confederate States of America.

The first attack of the Civil War came on April 12, 1861, when Confederates took control of South Carolina’s Fort Sumter .

Lee’s home state of Virginia seceded less than a week later, creating the defining moment of his career. When he was asked to lead Union forces, he resigned from military service rather than fight against his Virginia friends and neighbors.

General Robert E. Lee

Lee wasn’t a secessionist, but he immediately joined the Confederates and was named general and commander of the South’s fight for secession.

Lee has been widely criticized for his aggressive strategies that led to mass casualties. In the Battle of Antietam, on September 17, 1862, Lee made his first attempt at invading the North in the bloodiest single day of the war.

Antietam ended with roughly 23,000 casualties and the Union claiming victory for General George McClellan . Less than a week later, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation .

The battles continued through the cold, harsh winter and into the summer of 1863, when Lee’s troops challenged Union forces in Pennsylvania during the three-day Battle of Gettysburg, which claimed 28,000 Confederate soldiers’ lives and 23,000 casualties on the Union side.

The war dragged on for two more years until a victory for Lee became impossible. With a dwindling army, Lee surrendered to Grant on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, effectively ending the Civil War.

Arlington House

At the start of the war, Lee and his family headed South, leaving Arlington House, but they did not reclaim their property.

The federal government seized the estate (now the site of Arlington National Cemetery ) and used it for military graves for thousands of fallen Union soldiers, possibly to prevent Lee from ever returning home.

The Lee family residence is now managed by the National Park Service as Arlington House: the Robert E. Lee Memorial , and is open to the public for tours.

As a well-educated man with considerable social and military experience, Lee is known for many of his quotes regarding slavery , duty and military service, including:

- In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral and political evil in any country.

- Whiskey — I like it, I always did, and that is the reason I never use it.

- It is well that war is so terrible — lest we should grow too fond of it.

- So far from engaging in a war to perpetuate slavery, I am rejoiced that slavery is abolished. I believe it will be greatly for the interest of the South.

- I cannot trust a man to control others who cannot control himself.

- The education of a man is never completed until he dies.

- Do your duty in all things. You cannot do more, you should never wish to do less.

Robert E. Lee Day

In August of 1865, soon after the end of the war, Lee was invited to serve as president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University ), where he and his family are buried.

Since his death at age 63 on October 12, 1870, following a stroke, he has retained a place of distinction in most Southern states.

Lee’s January 19 birthday is observed (to varying degrees) on the third Monday in January as Robert E. Lee Day, an official state holiday in Mississippi and Alabama, and on January 19 in Florida and Tennessee.

Robert E. Lee Statues

The Confederate general remains one of the most divisive figures in American history.

Statues and other memorials built in his honor have become flashpoints in cities such as New Orleans , Louisiana, Baltimore, Maryland and Dallas, Texas. Many Robert. E. Lee statues have been removed, but Virginia’s 2017 decision to take one down sparked a violent protest that turned deadly in Charlottesville.

While Lee did not support secession, he never defended the rights of enslaved peoples. Instead, he led the Confederates as they attempted to dissolve the United States that his own father helped create.

Robert E. Lee. PBS American Experience . Arlington House. Arlington National Cemetery . Robert E. Lee. Washington & Lee University . Robert E. Lee. Stratford Hall . The Civil War. American Battlefield Trust . Robert E. Lee Quotes. Son of the South . The Reader’s Companion to American History. Eric Foner and John A. Garraty, Editors. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- Exhibitions Home

- Current Exhibitions

- All Exhibitions

- Loan Procedures for Institutions

- Special Presentations

The Civil War in America Biographies

Robert E. Lee

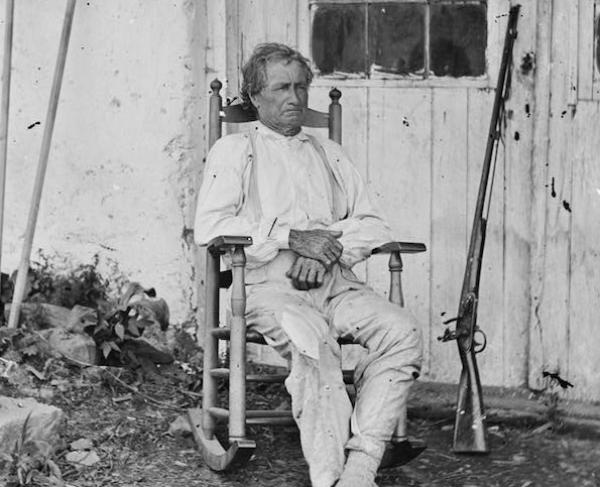

General Robert E. Lee (1807–1870). Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Digital ID # cwpb 04402

General Robert E. Lee (1807–1870) has continuously ranked as the leading iconic figure of the Confederacy. A son of Revolutionary War hero Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee, Robert graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1829, ranking second in a class of forty six—and without a single demerit. His prewar record as an officer was distinguished by numerous engineering projects, service in the Mexican War , and nearly three years as commandant at West Point. In March and April 1861, Lee was offered command of the principal Union Army. Yet, after Virginia seceded on April 17, he determined that "to lift my hand against my own State and people is impossible." After resigning from the U.S. Army, he assumed command of Virginia's forces on April 23. Lee’s genius as a military tactician came to the fore after he was given command of the Army of Northern Virginia in June 1862. Despite being consistently outnumbered by the enemy, he led his forces in a series of remarkable victories that included Second Manassas (Second Bull Run), Fredericksburg , and Chancellorsville . The Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 marked Lee’s last major campaign on Northern soil. Remaining thereafter in Virginia, he mounted skillful defenses against the Union's unrelenting Overland Campaign and the siege of Petersburg (spring 1864–spring 1865). After Petersburg and Richmond fell, Lee was finally compelled to surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Later that year, Lee accepted the presidency of Washington College External (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, a position he retained until his death on October 12, 1870.

Related Items

- To Secede or Not to Secede

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities

Robert E. Lee (1807–1870)

Robert E. Lee was a Confederate general during the American Civil War (1861–1865) who led the Army of Northern Virginia from June 1862 until its surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Descended from several of Virginia’s First Families, Lee was a well-regarded officer of the United States Army before the war. His decision to fight for the Confederacy was emblematic of the wrenching choices faced by Americans as the nation divided. After an early defeat in western Virginia, he repulsed George B. McClellan ‘s army from the Confederate capital during the Seven Days’ Battles (1862) and won stunning victories at Manassas (1862), Fredericksburg (1862), and Chancellorsville (1863). The Maryland and Pennsylvania campaigns he led resulted in major contests at Antietam (1862) and Gettysburg (1863), respectively, with severe consequences for the Confederacy. Lee offered a spirited defense during the Overland Campaign (1864) against Ulysses S. Grant , but was ultimately outmaneuvered and forced into a prolonged siege at Petersburg (1864–1865). Lee’s generalship was characterized by bold tactical maneuvers and inspirational leadership; however, critics have questioned his strategic judgment, his waste of lives in needless battles, and his unwillingness to fight in the Western Theater. In 1865, his beloved home at Arlington having been turned into a national cemetery, Lee became president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington . There he promoted educational innovation and presented a constructive face to the devastated Southern public. Privately Lee remained bitter and worked to obstruct societal changes brought about by the war, including the enfranchisement of African Americans. By the end of his life he had become a potent symbol of regional pride and dignity in defeat, and has remained an icon of the Lost Cause . He died on October 12, 1870.

Early Years

In peacetime Henry Lee steadily lost money and reputation because of unwise land speculation. He was sent to debtor’s prison while Robert was still an infant. In 1813, badly beaten by a political mob, and dodging his creditors, he skipped bail to sail for the West Indies. Robert never saw his father again.

Now dependent on the generosity of their kin, the family moved to Alexandria. Robert attended a relative’s plantation school and the Alexandria Academy, where he was given a classical education. His boyhood was enriched by a supportive and engaging extended family and academic success, but pinched by poverty and his mother’s failing health.

Misfortune again touched Robert’s life in 1821 with a scandal involving his half brother. Henry Lee IV shocked Virginians by seducing his young ward—her name was Elizabeth “Betsy” McCarty and she was Henry IV’s sister-in-law—embezzling her inheritance, and possibly murdering their child. Believing this disgrace would lead to social isolation, Robert convinced his mother to let him join the army.

Family and Military Life

Lee entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1825, where he excelled both scholastically and militarily. Admired for his geniality and fine presence, he was appointed cadet adjutant. However, he was unable to best Charles Mason, a talented New Yorker who took top honors academically, and who, like Lee, boasted a demerit-free record. (Mason went on to become chief justice of the Iowa Supreme Court.) Lee graduated second in the class of 1829 and joined the Corps of Engineers.

Two years later Lee wed Mary Anna Randolph Custis , the witty, artistic great-granddaughter of Martha Washington. The couple had seven children, to whom Lee was powerfully attached. He also became increasingly tied to the Custis family seat at Arlington, with its splendid grounds and historical associations. In Lee’s uncertain army life, Arlington became an important anchor.

For seventeen years, Lee worked to strengthen the nation’s frontier defenses. Assigned throughout the country, he redirected rivers, designed coastal fortifications, and surveyed newly acquired territory. In the army Lee was known for his sociability and attention to detail, but called himself “an indifferent engineer.” Opportunities for advancement were meager and the work required extended absences from his family. Lee considered leaving the service virtually every year. “I would advise no young man to enter the army,” he regretfully admitted in a letter to his wife.

The Mexican War (1846–1848) disrupted the routine of army duty. Though Lee did not approve of the war, he relished the opportunity for action. For several months he laid out transportation routes, but early in 1847 he was put on the staff of General Winfield Scott . Lee admired Scott’s ability to overcome disadvantage by what the general termed “headwork,” by which he meant outthinking the enemy, planning precisely, and reacting to crises intellectually and not emotionally. In addition, Scott depended heavily on his young engineer for reconnaissance and tactical planning. Lee fought with distinction at battles such as Vera Cruz (March 1847), Cerro Gordo (April 1847), and Chapultepec (September 1847). He received two brevet promotions for his performance at Cerro Gordo. Scott would later call Lee “the very best soldier I ever saw in the field.” Although the Mexican War gave Lee valuable battlefield experience, he did not lead troops or design strategic campaigns in this conflict.

After the war, Lee returned to structural engineering until 1852, when U.S. secretary of war Jefferson Davis appointed him superintendent of West Point. Lee had not wanted the post and found it stressful. He was a careful steward of the academy, but found little opportunity for innovation. His rigid belief in the virtue of “duty” was not appreciated by the cadets, among whom he was unpopular. One notable contribution was his focus on equestrian instruction. Under Lee’s leadership some of America’s greatest cavalry officers were trained, among them J. E. B. Stuart , Fitzhugh Lee , and Philip H. Sheridan.

In March 1855, Lee eagerly accepted a lieutenant colonelship in the newly established 2nd U.S. Cavalry. Assigned to Texas, his unit was responsible for subduing the Comanche and chasing Mexican banditos . It proved a difficult posting. Lee found the work frustrating, and the isolation and harsh landscape oppressive. His beloved mother-in-law and favorite sister died early in the 1850s, causing him to embrace a somber brand of evangelical Protestantism, which left him dejected and self-critical. When his father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis, died in 1857, Lee willingly returned to Arlington to settle the estate.

The Politics of Slavery

As Custis’s executor, Lee found himself confronted with the political reality of slavery. He disliked the institution—more for its inefficiency than from moral repugnance—yet defended it throughout his life. Custis, however, had liberated his slaves in a messy will that stipulated that they be released within five years. Lee interpreted this to mean that the slaves could be held for the entire period. The slaves, believing they were already free, accosted Lee and escaped in large numbers. Lee responded by hiring out many Arlington slaves, breaking up families that had been together for decades. He then filed legal petitions to keep them enslaved indefinitely. Only when the courts ruled against him did Lee finally free the slaves.

Lee was again exposed to the volatile politics of slavery when ordered in October 1859 to suppress an attempted slave insurrection led by the radical abolitionist John Brown at Harpers Ferry . Commanding a small detachment of marines, Lee led a model operation in which none of Brown’s hostages was injured, and Brown was taken alive. The ramifications of the disturbing incident were reinforced when Lee witnessed Brown’s ominous predictions of the bloodshed to come, and stood guard at his execution.

The Union Divides

The malaise over slavery followed Lee when he returned to full-time duty in February 1860. As acting head of the Department of Texas he refused to allow that state’s secessionists to wrest federal property from him. As the crisis deepened, however, his thinking became increasingly conflicted. Although he did not believe in secession, he also declared that if “the Union can only be maintained by the sword & bayonet … its existence will lose all interest with me.” He particularly hoped that Virginia would remain in the Union so that his various loyalties—to country, army, state, and family—could remain intact. Recalled to Washington, he was promoted in March 1861 to full colonel by the new U.S. president, Abraham Lincoln, and once again swore an oath of allegiance to the United States. A few weeks later, Lee was forced to confront his ambivalence when Virginia seceded and he was offered command of Union forces recruited to protect Washington, D.C.

Mary Lee later called the moment “the severest struggle” of her husband’s life. Faced with a divided family and the collapse of his career, Lee spent two days consulting scripture and quietly considering his future. On April 20, 1861, he resigned from the U.S. Army, telling friends that he could not participate in an invasion of the South. A few days later he accepted command of Virginia’s forces.

As general, Lee was first assigned a desk job, where he undertook a methodical organization of Virginia’s forces. Finally given a field command in western Virginia, he was “mortified” when Union general William S. Rosecrans defeated him at Cheat Mountain in September 1861. Jefferson Davis relieved Lee and sent him to oversee the construction of fortifications along the Carolina and Georgia coasts, then returned him to an advisory position. Although frustrated, Lee later benefited from the connections he built with political leaders in the Confederate capital at Richmond .

On June 1, 1862, Lee began his celebrated relationship with the Army of Northern Virginia when Davis ordered him to temporarily replace Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston , wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines during the Peninsula Campaign . Lee’s immediate task was to check the advance of Union general George B. McClellan, whose Army of the Potomac was threatening Richmond. Devising a strategy that combined bold field maneuvers and defensive earthworks—the latter led to some calling him the “King of Spades”—Lee confronted McClellan from June 25 until July 1 in the Seven Days’ Battles. His men decisively won only one of the contests— Gaines’s Mill —and the plan suffered from overly complicated movements as well as poor communications. Nonetheless, by relentless fighting and skillful use of terrain, Lee was able to frighten McClellan away from the Confederate capital.

The Seven Days’ Battles previewed much of Lee’s battlefield style. They allowed horrific casualties—at Malvern Hill , the Army of Northern Virginia lost 5,300 men killed, wounded, or captured in a fight that included a massive assault that gained nothing—but showcased Lee’s expert use of entrenchments, and how he exploited opportunities through improvisation and sheer brio. The victory also inspired his men, who rallied to their new commander with an esprit that would last throughout the war.

The Golden Year for the Confederacy

After the Seven Days’ Battles, Lincoln placed John Pope in command of a new Army of Virginia, consisting of three corps that already had performed poorly against Confederate general Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign (1862). Rightly suspecting that he might now face both McClellan’s and Pope’s armies, Lee initiated an aggressive campaign. Under his orders, Jackson confronted Union general Nathaniel P. Banks at Cedar Mountain on August 9, 1862, to win a narrow victory. Ignoring conventional wisdom, Lee then divided his force, tricking Pope into chasing Jackson, who faked a retreat. After a dramatic march, Jackson lured Pope’s overconfident army into a fierce battle at Manassas Junction on August 28. The following day, Lee’s other wing commander, James Longstreet , brought up his men to rejoin the two corps in the heat of fighting—an immensely difficult battlefield maneuver. On August 30, Longstreet hit Pope’s vulnerable left flank, crushed the Union force, and chased them to the horizon. (The three-day battle has come to be known as the Second Battle of Manassas.) Jackson followed the retreating Union troops, but was halted at the Battle of Chantilly on September 1.

Critics complained that Lee took too many risks on the campaign, that luck and Pope’s ineptitude rather than Confederate skill held it together, and that the days had again been shockingly “sanguinary.” Yet the boldness of his actions had given Lee the momentum. In the coming months his agility and elusiveness continually “baffled” superior Union forces, often turning their offensive drives into desperate defensive stands.

In this spirit Lee undertook an invasion of Union territory, a move that was popular with the public and the troops. Lee wanted to spare Virginians the ravages of two armies and he was anxious for his men to live off Maryland’s greener pastures. He and Davis hoped that if the war directly threatened Northerners it would create a political crisis that could topple the U.S. government and attract foreign assistance to the South. They also thought that slaveholding Maryland might be “liberated” and brought to their side.

But the arduous march north was poorly outfitted, and the men arrived in Maryland weakened by hunger and diminished by a high rate of desertion and straggling. (By some estimates Lee lost a third of his army.) Greeted without the expected enthusiasm, for the first time they suffered the disadvantage of being on hostile territory. The invasion had been a high-stakes gamble, but Lee increased the odds against him by again dividing his army, despite his officers’ skepticism. Jackson’s corps was sent to take logistically important Harpers Ferry, and the rest faced McClellan’s advancing men. The two armies clashed at South Mountain on September 14, where Lee was able to delay, but not defeat, the Union forces.

Three days later they met again near the town of Sharpsburg, Maryland. McClellan, who had accidentally intercepted Lee’s campaign plans, also had an advantage in artillery and men. But the Union effort on September 17 was badly executed and its numerical superiority never fully exploited. Lee was able to thwart disaster by adroitly shifting forces to meet each of the violent contests that raged along Antietam Creek. At the end of the bloody day, however, the Union held the advantage.

Lee saved his army by deftly retreating across the Potomac River , and a brief fight at Shepherdstown helped convince McClellan not to pursue him. Though the campaign featured a victory at Harpers Ferry and some impressive tactical parrying, Lee had achieved none of his strategic objectives. In addition, Lincoln used his advantage to wrest the moral high ground from the South, issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, and effectively collapsing the possibility of foreign assistance to the Confederacy.

Lee’s army reestablished its formidable reputation at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. This time the Confederates faced a Union contingent a third again its size, under General Ambrose E. Burnside . Concentrating his forces, and establishing positions that took full advantage of the weaponry of the day, Lee allowed the Northern men to fruitlessly attack his defensive strongholds on Marye’s Heights, slaughtering thousands. The Union army survived by escaping across the Rappahannock River, but the defeat badly strained Northern morale.

Early in 1863, Lincoln again changed generals, placing the Army of the Potomac’s military machine under Joseph Hooker . Hooker believed he could trap Lee by attacking him simultaneously from several directions. Facing a Union force double his size at a crossroads called Chancellorsville, west of Fredericksburg, Lee again precariously divided his army. Over the course of the fighting, which lasted from May 1 until May 6 and included another Union charge up Marye’s Heights, Lee was able to squeeze the Union forces from two directions and then reunite his troops. The Confederates captured the most favorable artillery positions, launched a devastating barrage, then pressed the attack until Hooker had to pull back. Through surprise and daring, Lee had turned a vulnerable defensive position into a brilliant tactical offense.

Even the Union prisoners cheered when Lee rode in front of his troops in this moment of triumph. Yet in many ways it was an empty victory. More than 20 percent of his soldiers lay on the gory fields, or were maimed or missing. Stonewall Jackson, wounded accidentally by his own men, died on May 10. Lee himself complained that “our loss was severe, and again we had gained not an inch of ground and the enemy could not be pursued.”

Lee risked his scarce resources in such large and costly battles because he hoped to destroy the enemy’s army—or to discourage Northerners so profoundly that they would demand an end to the conflict. In each contest he attacked with ferocity, hoping for a final annihilation of the Union forces. In addition, much of the Southern public was buoyed by theatrical successes such as Chancellorsville and anxious for quick victory. But this Napoleonic style of warfare was less effective against improved weaponry and technology, such as railroads, that allowed troops to be easily reinforced. Even the fanatical Confederate Edmund Ruffin noted that such “great & bloody battles” led to “no important results whatever, except to damage, weaken, & impoverish both the contending powers.” Later historians have also questioned Lee’s strategy and debated whether the Confederacy might have been more successful in a war of attrition, wearing down the North by using irregular tactics on the difficult Southern terrain, much as Washington and Lee’s own father did against the British.

Gettysburg to the End of the War

Lee’s reputation had now grown to the point that he and his army had become a major source of national unity in the Confederacy. Civilians as well as soldiers looked to him for leadership and inspiration, rather than to Davis’s problematic government. With his authority at its height, Lee convinced Confederate officials to approve another northward excursion. Always reluctant to fight on fronts not directly related to Virginia’s defense, he argued against sending his men to reinforce besieged Vicksburg, Mississippi. In June 1863, after reorganizing his army, he moved up the Shenandoah Valley (where he fought and won the Second Battle of Winchester), through Maryland, and into Pennsylvania. Lee welcomed the fresh foraging, and again hoped to cripple Union morale by delivering a knockout punch that would win peace on Confederate terms.

The battle that resulted was fought at Gettysburg for three days from July 1 until July 3, 1863. The first day’s contest began as an incidental cavalry encounter and escalated as both sides augmented their forces. By evening, Lee’s men—including forces under Confederate generals A. P. Hill , Richard S. Ewell , and Jubal A. Early —had driven their opponents outside Gettysburg, but the Union troops made a prescient decision to retreat to high ground south of town. Lee also recognized the value of these heights and ordered Ewell to take a critical rise called Culp’s Hill , but he failed to provide Ewell with either the precise instructions or the reinforcements needed to gain a success.

The next day, Lee determined to attack the Northern forces, despite the misgivings of his lieutenants, including Longstreet, in particular. He had two serious disadvantages. Under generals George G. Meade (who had taken command of the Army of the Potomac a few days earlier) and Winfield Scott Hancock, the Union line had been strengthened overnight by entrenchments and an ingenious fish-hook formation that allowed for easy reinforcement of its weaker sections. Lee’s second problem was a lack of information. Cavalry general J. E. B. Stuart, who served as the eyes and ears of Lee’s army, was absent (with Lee’s approval) on an extended expedition, foraging and harassing Union troops away from the front lines. Lee had hoped for an early morning attack on both the Union right and left flanks, but the shortage of reliable intelligence caused delays, misguided marches, and unexpected exposure to Union fire. Despite spirited fighting by Longstreet’s corps at critical spots such as Little Round Top and Devil’s Den, the Union line held.

Casualties During Pickett’s Charge

Lee hoped to recoup the Army of Northern Virginia’s pride that autumn during the Bristoe Campaign, but Meade refused to be enticed into another major engagement, and the Confederates had little success. Still determined to “strike them a blow” Lee eagerly awaited the spring season, undaunted by the appointment of Ulysses S. Grant as general-in-chief of Union armies. Grant, the victor at Vicksburg, came east to lead the Army of the Potomac personally.

What ensued was the Overland Campaign, some seven weeks of brutal, relentless fighting. The armies first met on May 5 and 6, 1864, in the scrubby woods, known locally as the Wilderness , near the old Chancellorsville battlefield. Lee knew his resources were too limited to force Grant back to Washington, D.C., but he had not expected the Union to push onward after its appalling casualties in a stalemated contest at the Battle of the Wilderness . Some of the heaviest fighting of the war took place the following week near Spotsylvania Court House, particularly around a Confederate breastwork known as the Bloody Angle. Lee, outnumbered two to one, was able to hold his own through swift tactical maneuvering and his forceful personal role in rallying the ranks. Still, Grant edged southward. Lee forestalled the drive when on June 3 the Union flung itself against the zigzagged Confederate fortifications at Cold Harbor, suffering 7,000 casualties, many of whom fell in an ill-conceived assault. Nonetheless, Grant continued the forward movement, maneuvering past Lee a few weeks later and into a siege at Petersburg .

Lee’s inspirational leadership of his soldiers was notable throughout the war, but in this campaign it became legendary. The men looked up to Lee because of his splendid bearing, his courage on the field, his fair dealings, and his willingness to share their hardships. He also led them to victory, and to many he became the embodiment of the Army of Northern Virginia’s alleged invincibility. During the campaigns of 1864 he was conspicuous on the field—rallying the troops, directing battle maneuvers, plugging gaps, and sometimes acting more like a brigade commander than the general in charge. This hands-on role is one reason Lee was able to frustrate Grant’s powerful machine for so long. It also reinforced his soldiers’ worshipful regard. “You are the country to these men,” General Henry A. Wise reportedly told Lee at the end of the conflict. “They have fought for you.”

Diminished by some 35,000 casualties during the Overland Campaign—the most famous of whom, J. E. B. Stuart, was killed at the Battle of Yellow Tavern —the Army of Northern Virginia held on in miserable trench conditions for nearly nine months. Always a reluctant politician, Lee was unable to wrest critical supplies from the Confederate authorities. His army quashed a Union attempt to exploit the huge explosion of a mine dug under its fortifications at the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864, but various efforts at offensive action failed. After a final repulse at Fort Stedman on March 25, 1865, Lee’s defeat was only a matter of time. Hoping to move the remnant of his army southward to join Joseph Johnston’s troops, Lee signaled Davis that Petersburg and Richmond must be abandoned. On April 6, during the Appomattox Campaign , the Confederates suffered a costly defeat at Sailor’s Creek , which left them desperately short of men and supplies. Cornered, Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House. “I fought the enemy at every step,” he told a confidant in what amounted to a final assessment of his war efforts. “I believe I got out of [my army] all they could do or all any men could do.”

Later Years

Despite his defeat , Lee was hugely admired in the postwar South. Counseling his soldiers to return home peaceably, Lee showed by example how to accept loss with dignity. The war had taken a terrific personal toll on the Lees: death had claimed numerous family members and Arlington had been confiscated for use as a national cemetery. Penniless, Lee accepted an offer to be president of Washington College, a small, nearly destitute school in Lexington. His stated goal was the instruction of the rising generation and the rebuilding of his state. Lee proved to be an able educator, though he did not relish the work. He added practical subjects such as engineering and journalism to the traditional classical studies, attracted funding from both the North and the South, and introduced a rigorous disciplinary code. Publicly he counseled Southerners to face the future with stoicism and hard work.

Privately, he was far from content. Although Lee was granted parole at Appomattox, his personal fate was uncertain until his citizenship was returned with the amnesty of 1868. After this time, though still maintaining a low public profile, he worked to establish a conservative state government, wrote angry private diatribes against the principle of majority rule, and advocated disenfranchising the newly liberated African Americans. Racial conflicts also plagued Washington College, to which he responded ambivalently. He considered writing his memoirs but decided they could become provocative and edited his father’s reminiscences instead. Saddened and embittered, Lee told a friend that the “great mistake” of his life had been “taking a military education.” Lee died of a probable stroke on October 12, 1870.

The South went into universal mourning and Lee became a charismatic symbol of honor and sacrifice in the region. In the nineteenth century, proponents of the Lost Cause view of the Civil War used both myth and fact to mold a public image of Lee as a titan of personal virtue and military genius. Early in the twentieth century, several national figures, including U.S. president Woodrow Wilson , praised him as a unifying personality, citing his efforts to pacify the South after the war. Recent scholarship has more-closely probed Lee’s motives and battlefield decisions, as well as his support for a racially stratified society. Since his decision to withdraw from the Union in 1861, his actions have provoked controversy. Yet Lee remains a significant historical figure, whose importance lies as much in the questions he prods Americans to ask about patriotism and loyalty as it does in his battlefield prowess.

- Antebellum Period (1820–1860)

- Civil War, American (1861–1865)

- Mexican War (1846–1848)

- Reconstruction and the New South (1865–1901)

- Alexander, Edward Porter. Fighting for the Confederacy . Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

- Carmichael, Peter, ed. Audacity Personified . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004.

- Connelly, Thomas L. The Marble Man . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977.

- Davis, William C. The Cause Lost: Myths and Realities of the Confederacy . Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1996.

- Fellman, Michael. “Robert E. Lee, Postwar Southern Nationalist.” Civil War History 46: 185–204.

- Freeman, Douglas Southall. R. E. Lee . 4 Volumes. New York: Charles Scribner, 1934–1937.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. Lee the Soldier . Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. General Lee’s Army . New York: The Free Press, 2008.

- McClure, John M. “The Freedman’s Bureau School in Lexington versus ‘General Lee’s Boys.’” In Virginia’s Civil War , edited by Peter Wallenstein and Bertram Wyatt-Brown. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005.

- Nolan, Alan T. Lee Considered . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Pryor, Elizabeth Brown. Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee through His Private Letters . New York: Viking, 2007.

- Taylor, Walter Herron. Lee’s Adjutant: The Wartime Letters of Colonel Walter Herron Taylor, 1862–1865 . Edited by R. Lockwood Tower. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1995.

- Thomas, Emory M. “Young Man Lee.” In Leadership during the Civil War , edited by Roman G. Heleniak and Lawrence L. Hewitt. Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Publishing Co., 1992.

- Name First Last

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Never Miss an Update

Partners & affiliates.

Encyclopedia Virginia 946 Grady Ave. Ste. 100 Charlottesville, VA 22903 (434) 924-3296

Indigenous Acknowledgment

Virginia Humanities acknowledges the Monacan Nation , the original people of the land and waters of our home in Charlottesville, Virginia.

We invite you to learn more about Indians in Virginia in our Encyclopedia Virginia .

Robert E. Lee

Born to Revolutionary War hero Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee in Stratford Hall, Virginia, Robert Edward Lee seemed destined for military greatness. Despite financial hardship that caused his father to depart to the West Indies, young Robert secured an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated second in the class of 1829. Two years later, he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis, a descendant of George Washington 's adopted son, John Parke Custis . Yet with all his military pedigree, Lee had not set foot on a battlefield. Instead, he served seventeen years as an officer in the Corps of Engineers, supervising and inspecting the construction of the nation's coastal defenses. Service during the 1846 war with Mexico, however, changed that. As a member of General Winfield Scott 's staff, Lee distinguished himself, earning three brevets for gallantry, and emerging from the conflict with the rank of colonel.

From 1852 to 1855, Lee served as superintendent of West Point, and was therefore responsible for educating many of the men who would later serve under him - and those who would oppose him - on the battlefields of the Civil War. In 1855 he left the academy to take a position in the cavalry and in 1859 was called upon to put down abolitionist John Brown ’s raid at Harpers Ferry.

Because of his reputation as one of the finest officers in the United States Army, Abraham Lincoln offered Lee the command of the Federal forces in April 1861. Lee declined and tendered his resignation from the army when the state of Virginia seceded on April 17, arguing that he could not fight against his own people. Instead, he accepted a general’s commission in the newly formed Confederate Army. His first military engagement of the Civil War occurred at Cheat Mountain, Virginia (now West Virginia) on September 11, 1861. It was a Union victory but Lee’s reputation withstood the public criticism that followed. He served as military advisor to President Jefferson Davis until June 1862 when he was given command of the wounded General Joseph E. Johnston 's embattled army on the Virginia peninsula.

Lee renamed his command the Army of Northern Virginia, and under his direction it would become the most famous and successful of the Confederate armies. This same organization also boasted some of the Confederacy's most inspiring military figures, including James Longstreet , Stonewall Jackson and the flamboyant cavalier J.E.B. Stuart . With these trusted subordinates, Lee commanded troops that continually manhandled their blue-clad adversaries and embarrassed their generals no matter what the odds.

Yet despite foiling several attempts to seize the Confederate capital, Lee recognized that the key to ultimate success was a victory on Northern soil. In September 1862, he launched an invasion into Maryland with the hope of shifting the war's focus away from Virginia. But when a misplaced dispatch outlining the invasion plan was discovered by Union commander George McClellan the element of surprise was lost, and the two armies faced off at the battle of Antietam . Though his plans were no longer a secret, Lee nevertheless managed to fight McClellan to a stalemate on September 17, 1862. Following the bloodiest one-day battle of the war, heavy casualties compelled Lee to withdraw under the cover of darkness. The remainder of 1862 was spent on the defensive, parrying Union thrusts at Fredericksburg and, in May of the following year, Chancellorsville .

The masterful victory at Chancellorsville gave Lee great confidence in his army, and the Rebel chief was inspired once again to take the fight to enemy soil. In late June of 1863, he began another invasion of the North, meeting the Union host at the crossroads town of Gettysburg , Pennsylvania. For three days Lee assailed the Federal army under George G. Meade in what would become the most famous battle of the entire war. Accustomed to seeing the Yankees run in the face of his aggressive troops, Lee attacked strong Union positions on high ground. This time, however, the Federals wouldn't budge. The Confederate war effort reached its high water mark on July 3, 1863 when Lee ordered a massive frontal assault against Meade's center, spear-headed by Virginians under Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett . The attack known as Pickett's charge was a failure and Lee, recognizing that the battle was lost, ordered his army to retreat. Taking full responsibility for the defeat, he wrote Jefferson Davis offering his resignation, which Davis refused to accept.

After the simultaneous Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg , Mississippi, Ulysses S. Grant assumed command of the Federal armies. Rather than making Richmond the aim of his campaign, Grant chose to focus the myriad resources at his disposal on destroying Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. In a relentless and bloody campaign, the Federal juggernaut bludgeoned the under-supplied Rebel band. In spite of his ability to make Grant pay in blood for his aggressive tactics, Lee had been forced to yield the initiative to his adversary, and he recognized that the end of the Confederacy was only a matter of time. By the summer of 1864, the Confederates had been forced into waging trench warfare outside of Petersburg . Though President Davis named the Virginian General-in-Chief of all Confederate forces in February 1865, only two months later, on April 9, 1865, Lee was forced to surrender his weary and depleted army to Grant at Appomattox Court House , effectively ending the Civil War.

Lee returned home on parole and eventually became the president of Washington College in Virginia (now known as Washington and Lee University). He remained in this position until his death on October 12, 1870 in Lexington, Virginia.

Test Your Knowledge

John L. Burns

Joseph H. De Castro

Related battles, you may also like.

The Civil War

A Smithsonian magazine special report

Making Sense of Robert E. Lee

“It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.”— Robert E. Lee, at Fredericksburg

Roy Blount, Jr.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/lee_father.jpg)

Few figures in American history are more divisive, contradictory or elusive than Robert E. Lee, the reluctant, tragic leader of the Confederate Army, who died in his beloved Virginia at age 63 in 1870, five years after the end of the Civil War. In a new biography, Robert E. Lee , Roy Blount, Jr., treats Lee as a man of competing impulses, a “paragon of manliness” and “one of the greatest military commanders in history,” who was nonetheless “not good at telling men what to do.”

Blount, a noted humorist, journalist, playwright and raconteur, is the author or coauthor of 15 previous books and the editor of Roy Blount’s Book of Southern Humor . A resident of New York City and western Massachusetts, he traces his interest in Lee to his boyhood in Georgia. Though Blount was never a Civil War buff, he says “every Southerner has to make his peace with that War. I plunged back into it for this book, and am relieved to have emerged alive.”

“Also,” he says, “Lee reminds me in some ways of my father.”

At the heart of Lee’s story is one of the monumental choices in American history: revered for his honor, Lee resigned his U.S. Army commission to defend Virginia and fight for the Confederacy, on the side of slavery. “The decision was honorable by his standards of honor—which, whatever we may think of them, were neither self-serving nor complicated,” Blount says. Lee “thought it was a bad idea for Virginia to secede, and God knows he was right, but secession had been more or less democratically decided upon.” Lee’s family held slaves, and he himself was at best ambiguous on the subject, leading some of his defenders over the years to discount slavery’s significance in assessments of his character. Blount argues that the issue does matter: “To me it’s slavery, much more than secession as such, that casts a shadow over Lee’s honorableness.”

In the excerpt that follows, the general masses his troops for a battle over three humid July days in a Pennsylvania town. Its name would thereafter resound with courage, casualties and miscalculation: Gettysburg.