Online Game Addiction and the Level of Depression Among Adolescents in Manila, Philippines

Article sidebar, main article content.

Introduction: World Health Organization recognizes online game addiction as a mental health condition. The rise of excessive online gaming is emerging in the Philippines, with 29.9 million gamers recorded in the country. The incidence of depression is also increasing in the country. The current correlational analysis evaluated the association between online game addiction and depression in Filipino adolescents.

Methods: A paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaire assessing depression and online game addiction was distributed from August to November, 2018. The questionnaire included socio-demographic profiles of the respondents, and the 14-item Video Game Addiction Test (VAT) (Cronbach's ?=0.91) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Cronbach's ?=0.88) to determine levels of online game addiction and depression, respectively. Multiple regression analyses were used to test the association between depression and online game addiction.

Results: Three hundred adolescents (59% males, 41% females) participated in the study. Fifty-three out of 300 respondents (12.0% males, 5.7% females) had high level of online game addiction as reflected in their high VAT scores. In this study, 37 respondents (6.7% males, 5.7% females) had moderately severe depression and 6 (2.0%) females had severe depression. Online game addiction was positively correlated with depression in this study ( r =0.31; p <0.001). When multiple regression analysis was computed, depression was found to be a predictor of online game addiction ( Coefficient =0.0121; 95% CI-8.1924 - 0.0242; p =0.05).

Conclusion: Depression, as associated with online game addiction, is a serious threat that needs to be addressed. High level of online game addiction, as positively correlated to the rate of depression among adolescents in Manila, could potentially be attributed to the booming internet industry and lack of suffiicent mental health interventions in the country. Recommended interventions include strengthening depression management among adolescents and improving mental health services for this vulnerable population groups in schools and within the communities.

Article Details

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- The Author retains copyright in the Work, where the term “Work” shall include all digital objects that may result in subsequent electronic publication or distribution.

- Upon acceptance of the Work, the author shall grant to the Publisher the right of first publication of the Work.

- Attribution—other users must attribute the Work in the manner specified by the author as indicated on the journal Web site;

- The Author is able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the nonexclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the Work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), as long as there is provided in the document an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post online a prepublication manuscript (but not the Publisher’s final formatted PDF version of the Work) in institutional repositories or on their Websites prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work. Any such posting made before acceptance and publication of the Work shall be updated upon publication to include a reference to the Publisher-assigned DOI (Digital Object Identifier) and a link to the online abstract for the final published Work in the Journal.

- Upon Publisher’s request, the Author agrees to furnish promptly to Publisher, at the Author’s own expense, written evidence of the permissions, licenses, and consents for use of third-party material included within the Work, except as determined by Publisher to be covered by the principles of Fair Use.

- the Work is the Author’s original work;

- the Author has not transferred, and will not transfer, exclusive rights in the Work to any third party;

- the Work is not pending review or under consideration by another publisher;

- the Work has not previously been published;

- the Work contains no misrepresentation or infringement of the Work or property of other authors or third parties; and

- the Work contains no libel, invasion of privacy, or other unlawful matter.

- The Author agrees to indemnify and hold Publisher harmless from Author’s breach of the representations and warranties contained in Paragraph 6 above, as well as any claim or proceeding relating to Publisher’s use and publication of any content contained in the Work, including third-party content.

Revised 7/16/2018. Revision Description: Removed outdated link.

Ryan V. Labana, Polytechnic University of the Philippines

Jehan l. hadjisaid, polytechnic university of the philippines, adrian r. imperial, polytechnic university of the philippines, kyeth elmerson jumawid, polytechnic university of the philippines, marc jayson m. lupague, polytechnic university of the philippines, daniel c. malicdem, polytechnic university of the philippines.

ePC. 2019 Video Game Industry Statistics, Trends & Data [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from https://www.wepc.com/news/video-game-statistics/ .

Griffiths MD, Davies MN, & Chappell D. Online computer gaming: a comparison of adolescent and adult gamers. J Adolesc 2004; 27: 87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.10.007.

Barnett J & Coulson M. Virtually real: A psychological perspective on massively multiplayer online games. Review of General Psychology 2010; 14: 167-179. doi: 10.1037/a0019442.

Elson M & Ferguson CJ. Gun violence and media effects: Challenges for science and public policy. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2013; 203: 322-324. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128652.

Ferguson CJ, Coulson M, & Barnett J. A meta-analysis of pathological gaming prevalence and comorbidity with mental health, academic and social problems. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2011; 45: 1573-1578. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.005.

Statista. Distribution of computer and video gamers in the United States from 2006 to 2019, by gender. [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from https://www.statista.com/statistics/232383/gender-split-of-us-computer-and-video-gamers/

Newzoo. The Filipino Gamer, 2017 [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from https://newzoo.com/insights/infographics/the-filipino-gamer/ .

Veltri NF, Krasnova H, Baumann A, & Kalayamthanam N. Gender differences in online gaming: A literature review. Proceedings of the 20th Americas Conference on Information Systems, Savannah, 2014 [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.667.4530&rep=rep1&type=pdf .

Griffiths MD & Hunt N. Computer game playing in adolescence: Prevalence and demographic indicators. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 1995; 5: 189-193. doi: 10.1002/casp.2450050307

Kuss DJ & Griffiths MD. Internet gaming addiction: A systematic review of empirical research. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 2012; 10: 278-296. doi: 10.1007/s11469-011-9318-5

Grusser SM, Thalemann R, Albrecht U, & Thalemann CN. Excessive computer usage in adolescents-a psychometric evaluation. Wiener KlinischeWochenschrift 2005; 117: 188-195. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0339-6.

Wood RTA & Griffiths MD. A qualitative investigation of problem gambling as an escape based coping strategy. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 2007; 80: 107-125. doi: 10.1348/147608306X107881.

Wan, CS & Chiou WB. Why are adolescents addicted to online gaming? An interview study in Taiwan. Cyber Psychology& Behavior 2006; 9: 762-766. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.762.

Wood RTA, Griffiths MD, & Parke A. Experiences of time loss among videogame players: An empirical study. CyberPsychology& Behavior 2007; 10: 38-44. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9994.

Fu KW, Chan WSC, Wong PWC, & Yip PSF. Internet addiction: Prevalence, discriminant validity and correlates among adolescents in Hong Kong. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010; 196: 486–492. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075002.

Griffiths M. Does internet and computer "addiction" exist? Some case study evidence. Cyber Psychology & Behavior 2004;3(2): 211-218. doi: 10.1089/109493100316067.

Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, & King DL. Video game addiction: Past, present, and future. Current Psychiatry Review, 2012; 8:0000-000. doi: 10.2174/157340012803520414 .

Griffiths MD. Online games, addiction, and overuse of. InThe International Encyclopdia of Digital Communication and Society.1st ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2015. doi: 10.1002/9781118290743.wbiedcs044.

Beutel ME, Hoch C, Woelfing K, Mueller KW. Clinical characteristics of computer game and Internet addiction in persons seeking treatment in an outpatient clinic for computer game addiction. Z. Psychosom. Med. Psychother. 2011, 57, 77–90. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2011.57.1.77.

Kuss DJ & Griffiths MD. Internet and gaming addiction: A systematic literature review of neuroimaging studies. Brain Sci 2012; 2: 347-374. doi: 10.3390/brainsci2030347.

Anderson CA, Funk JB, & Griffiths MD. Contemporary issues in adolescent video game playing: brief overview and introduction to the special issue. J Adolesc 2004; 27(1), 1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.10.001.

UNICEF. At a glance: Philippines [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/philippines_statistics.html#123 .

Lee YJ, Cho SJ, Cho IH, & Kim SJ. Insufficient sleep and suicidality in adolescents. Sleep2012; (4):455-60. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1722.

Keaten J & Cheng M. Cumpolsive video-game playing could be mental health problem [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2018-06-compulsive-video-game-mental-health-problem.html .

Hymas C & Dodds L. Addictive video games may change children's brains in the same way as drugs and alcohol, study reveals [Accessed 2020 June 15] Available from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/06/12/addictive-video-games-may-change-childrens-brains-way-drugs/ .

Peng W & Liu M. Online gaming dependency: A preliminary study in China. CyberpsycholBehav Soc Netw 2010; 13 (3). doi: 10.1089=cyber.2009.0082.

Craven R. Targeting neural correlates of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006;7:1. doi: 10.1038/nrn1840.

Verecio R. Online gaming addiction among BSIT students of Leyte Normal University Philippines its implication towards academic performance. INDJSRT 2018; 11(47): 1-4. DOI: 10.17485/ijst/2018/v11i47/137972.

Cortes MDS, Alcalde JV, & Camacho JV. Effects of computer gaming on High School students' performance in Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines. 国際公共政策研究 (International Public Policy Research). 2012; 16(2):75- 88. [Accessed December 2020]. Available from: https://ir.library.osaka.ac.jp/repo/ouka/all/24497/osipp_030_075.pdf .

Lumbay C, Larisma CCM, Centillas Jr. CL. Computer gamers'academic performance in a Technological State College in Leyte, Philippines. Journal of Social Sciences 2017; 6(2):41-49. doi: 10.25255/jss.2017.6.2S.41.49.

Rappler. Mental illness, Suicide Cases Rising Among Youth [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/211671-suicide-cases-mental-health-illness-youth-rising-philippines .

Rappler. How does the PH fare in mental health care? [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/184754-philippines-mental-health-care .

World Population Review. Manila Population 2019 [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from http://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/manila-population/ .

Philippine Statistics Authority. Population of the City of Manila Climbed to 1.7 Million (Results from the 2010 Census of Population and Housing) [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from https://psa.gov.ph/content/population-city-manila-climbed-17-million-results-2010-census-population-and-housing .

OpenEpi. Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health. [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from http://openepi.com/SampleSize/SSPropor.htm .

van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, van den Eijnden RJ, Vermulst AA, & van de Mheen D. Video game addiction test: validity and psychometric characteristics. Cyber psychol Behav Soc Netw2012; 15(9):507-11. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0007.

Meerkerk GJ, Van Den Eijnden RJ, Vermulst AA, & Garretsen HF. The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): some psychometric properties. Cyber psychol Behav 2009; 12(1):1-6. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0181.

van Rooij AJ, Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Shorter GW, Shoenmakers TM, van de Mheen D. The (co occurrence of problematic video gaming, substance use, and psychosocial problems in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2014; 3(3):157–165. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.013.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16(9):606-13. PMCID: PMC1495268.

Rikkers W, Lawrence D, Hafekost J, Zubrick SR. Internet use and electronic gaming by children and adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems in Australia –results from the second child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. BMC Public Health 2016; 16:399. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3058-1.

Weigh H-T, Chen M-H, Huang P-C, Bai Y-M. The association between online gaming, social phobia, and depression: an internet survey. BMC Psychiatry 2012; 12:92 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-92.

Zamani E, Chashmi M, & Hedayati N. Effect of addiction to computer games on physical and mental health of female and male students of guidance school in City of Isfahan. Addict Health 2009.; 1(2): 98-104. PMCID: PMC3905489.

Dong G, Lu Q, Zhou H, Zhao X. Precursor or sequela: pathological disorders in people with internet addiction disorder. PLoS One 2011; 6(2):e14703. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014703.

Brown I. A theoretical model of the behavioral addictions—Applied to offending. In. Hodge JE, McMurranM,Hollins CR. Eds. Chichester, UK: John Wiley; 1997, p. 13-65.

Schmit S, Chauchard E, Chabrol H, & Sejourne N. Evaluation of the characteristics of addiction to online video games among adolescents and young adults. Encephale 2011; 37 (3): 217-223. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2010.06.006. Epub 2010 Aug 17.

Wenzel T, Rushiti F, Aghani F, Diaconu G, Maxhuni B, & Zitterl W. Suicidal ideation, post-traumatic stress and suicide statistics in Kosovo. An analysis five years after the war. Suicidal ideation in Kosovo. Torture 2009; 19(3):238-47. PMID: 20065542.

Newman C. Minding the gap in Philippines’ mental health. [Accessed 2020 June 15] Available from https://www.bworldonline.com/minding-gap-philippines-mental-health/ .

Lagon HM. Guidance and counseling in the Philippines: A journey to maturity. [Accessed 2020 June 26]. Available from https://archive.dailyguardian.com.ph/guidance-and-counseling-in-the-philippines-a-journey-to-maturity/ .

Teh LA, Acosta AC, Hechanova MRM, Alianan AS. Attitudes of Psychology graduate students toward face-to-face and online counseling. Philippine Journal of Psychology 2014; 47 (2): 65-97.

Rappler. National hotline for mental health assistance now open [Accessed 2020 June 15]. Available from https://www.rappler.com/nation/146077-doh-hotline-mental-health-assistance-open-suicide-prevention .

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Ending Discrimination Against People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: The Evidence for Stigma Change. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/23442.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 December 2020

Effect of internet use and electronic game-play on academic performance of Australian children

- Md Irteja Islam 1 , 2 ,

- Raaj Kishore Biswas 3 &

- Rasheda Khanam 1

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 21727 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

71k Accesses

23 Citations

32 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Risk factors

This study examined the association of internet use, and electronic game-play with academic performance respectively on weekdays and weekends in Australian children. It also assessed whether addiction tendency to internet and game-play is associated with academic performance. Overall, 1704 children of 11–17-year-olds from young minds matter (YMM), a cross-sectional nationwide survey, were analysed. The generalized linear regression models adjusted for survey weights were applied to investigate the association between internet use, and electronic-gaming with academic performance (measured by NAPLAN–National standard score). About 70% of the sample spent > 2 h/day using the internet and nearly 30% played electronic-games for > 2 h/day. Internet users during weekdays (> 4 h/day) were less likely to get higher scores in reading and numeracy, and internet use on weekends (> 2–4 h/day) was positively associated with academic performance. In contrast, 16% of electronic gamers were more likely to get better reading scores on weekdays compared to those who did not. Addiction tendency to internet and electronic-gaming is found to be adversely associated with academic achievement. Further, results indicated the need for parental monitoring and/or self-regulation to limit the timing and duration of internet use/electronic-gaming to overcome the detrimental effects of internet use and electronic game-play on academic achievement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

What colour are your eyes? Teaching the genetics of eye colour & colour vision. Edridge Green Lecture RCOphth Annual Congress Glasgow May 2019

Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students

Introduction.

Over the past two decades, with the proliferation of high-tech devices (e.g. Smartphone, tablets and computers), both the internet and electronic games have become increasingly popular with people of all ages, but particularly with children and adolescents 1 , 2 , 3 . Recent estimates have shown that one in three under-18-year-olds across the world uses the Internet, and 75% of adolescents play electronic games daily in developed countries 4 , 5 , 6 . Studies in the United States reported that adolescents are occupied with over 11 h a day with modern electronic media such as computer/Internet and electronic games, which is more than they spend in school or with friends 7 , 8 . In Australia, it is reported that about 98% of children aged 15–17 years are among Internet users and 98% of adolescents play electronic games, which is significantly higher than the USA and Europe 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 .

In recent times, the Internet and electronic games have been regarded as important, not just for better results at school, but also for self-expression, sociability, creativity and entertainment for children and adolescents 13 , 14 . For instance, 88% of 12–17 year-olds in the USA considered the Internet as a useful mechanism for making progress in school 15 , and similarly, electronic gaming in children and adolescents may assist in developing skills such as decision-making, smart-thinking and coordination 3 , 15 .

On the other hand, evidence points to the fact that the use of the Internet and electronic games is found to have detrimental effects such as reduced sleeping time, behavioural problems (e.g. low self-esteem, anxiety, depression), attention problems and poor academic performance in adolescents 1 , 5 , 12 , 16 . In addition, excessive Internet usage and increased electronic gaming are found to be addictive and may cause serious functional impairment in the daily life of children and adolescents 1 , 12 , 13 , 16 . For example, the AU Kids Online survey 17 reported that 50% of Australian children were more likely to experience behavioural problems associated with Internet use compared to children from 25 European countries (29%) surveyed in the EU Kids Online study 18 , which is alarming 12 . These mixed results require an urgent need of understanding the effect of the Internet use and electronic gaming on the development of children and adolescents, particularly on their academic performance.

Despite many international studies and a smaller number in Australia 12 , several systematic limitations remain in the existing literature, particularly regarding the association of academic performance with the use of Internet and electronic games in children and adolescents 13 , 16 , 19 . First, the majority of the earlier studies have either relied on school grades or children’s self assessments—which contain an innate subjectivity by the assessor; and have not considered the standardized tests of academic performance 16 , 20 , 21 , 22 . Second, most previous studies have tested the hypothesis in the school-based settings instead of canvassing the whole community, and cannot therefore adjust for sociodemographic confounders 9 , 16 . Third, most studies have been typically limited to smaller sample sizes, which might have reduced the reliability of the results 9 , 16 , 23 .

By considering these issues, this study aimed to investigate the association of internet usage and electronic gaming on a standardized test of academic performance—NAPLAN (The National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy) among Australian adolescents aged 11–17 years using nationally representative data from the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing—Young Minds Matter (YMM). It is hypothesized that the findings of this study will provide a population-wide, contextual view of excessive Internet use and electronic games played separately on weekdays and weekends by Australian adolescents, which may be beneficial for evidence-based policies.

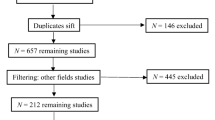

Subject demographics

Respondents who attended gave NAPLAN in 2008 (N = 4) and 2009 (N = 29) were removed from the sample due to smaller sample size, as later years (2010–2015) had over 100 samples yearly. The NAPLAN scores from 2008 might not align with a survey conducted in 2013. Further missing cases were deleted with the assumption that data were missing at random for unbiased estimates, which is common for large-scale surveys 24 . From the initial survey of 2967 samples, 1704 adolescents were sampled for this study.

The sample characteristics were displayed in Table 1 . For example, distribution of daily average internet use was checked, showing that over 50% of the sampled adolescents spent 2–4 h on internet (Table 1 ). Although all respondents in the survey used internet, nearly 21% of them did not play any electronic games in a day and almost one in every three (33%) adolescents played electronic games beyond the recommended time of 2 h per day. Girls had more addictive tendency to internet/game-play in compare to boys.

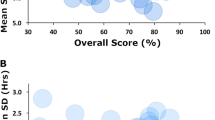

The mean scores for the three NAPLAN tests scores (reading, writing and numeracy) ranged from 520 to 600. A gradual decline in average NAPLAN tests scores (reading, writing and numeracy) scores were observed for internet use over 4 h during weekdays, and over 3 h during weekends (Table 2 ). Table 2 also shows that adolescents who played no electronic games at all have better scores in writing compared to those who play electronic games. Moreover, Table 2 shows no particular pattern between time spent on gaming and NAPLAN reading and numeracy scores. Among the survey samples, 308 adolescents were below the national standard average.

Internet use and academic performance

Our results show that internet (non-academic use) use during weekdays, especially more than 4 h, is negatively associated with academic performance (Table 3 ). For internet use during weekdays, all three models showed a significant negative association between time spent on internet and NAPLAN reading and numeracy scores. For example, in Model 1, adolescents who spent over 4 h on internet during weekdays are 15% and 17% less likely to get higher reading and numeracy scores respectively compared to those who spend less than 2 h. Similar results were found in Model 2 and 3 (Table 3 ), when we adjusted other confounders. The variable addiction tendency to internet was found to be negatively associated with NAPLAN results. The adolescents who had internet addiction were 17% less and 14% less likely to score higher in reading and numeracy respectively than those without such problematic behaviour.

Internet use during weekends showed a positive association with academic performance (Table 4 ). For example, Model 1 in Table 4 shows that internet use during weekends was significant for reading, writing and national standard scores. Youths who spend around 2–4 h and over 4 h on the internet during weekends were 21% and 15% more likely to get a higher reading scores respectively compared to those who spend less than 2 h (Model 1, Table 4 ). Similarly, in model 3, where the internet addiction of adolescents was adjusted, adolescents who spent 2–4 h on internet were 1.59 times more likely to score above the national standard. All three models of Table 4 confirmed that adolescents who spent 2–4 h on the internet during weekends are more likely to achieve better reading and writing scores and be at or above national standard compared to those who used the internet for less than 2 h. Numeracy scores were unlikely to be affected by internet use. The results obtained from Model 3 should be treated as robust, as this is the most comprehensive model that accounts for unobserved characteristics. The addiction tendency to internet/game-play variable showed a negative association with academic performance, but this is only significant for numeracy scores.

Electronic gaming and academic performance

Time spent on electronic gaming during weekdays had no effect on the academic performance of writing and language but had significant association with reading scores (Model 2, Table 5 ). Model 2 of Table 5 shows that adolescents who spent 1–2 h on gaming during weekdays were 13% more likely to get higher reading scores compared to those who did not play at all. It was an interesting result that while electronic gaming during weekdays tended to show a positive effect on reading scores, internet use during weekdays showed a negative effect. Addiction tendency to internet/game-play had a negative effect; the adolescents who were addicted to the internet were 14% less likely to score more highly in reading than those without any such behaviour.

All three models from Table 6 confirm that time spent on electronic gaming over 2 h during weekends had a positive effect on readings scores. For example, the results of Model 3 (Table 6 ) showed that adolescents who spent more than 2 h on electronic gaming during weekdays were 16% more likely to have better reading scores compared to adolescents who did not play games at all. Playing electronic games during weekends was not found to be statistically significant for writing and numeracy scores and national standard scores, although the odds ratios were positive. The results from all tables confirm that addiction tendency to internet/gaming is negatively associated with academic performance, although the variable is not always statistically significant.

Building on past research on the effect of the internet use and electronic gaming in adolescents, this study examined whether Internet use and playing electronic games were associated with academic performance (i.e. reading, writing and numeracy) using a standardized test of academic performance (i.e. NAPLAN) in a nationally representative dataset in Australia. The findings of this study question the conventional belief 9 , 25 that academic performance is negatively associated with internet use and electronic games, particularly when the internet is used for non-academic purpose.

In the current hi-tech world, many developed countries (e.g. the USA, Canada and Australia) have recommended that 5–17 year-olds limit electronic media (e.g. internet, electronic games) to 2 h per day for entertainment purposes, with concerns about the possible negative consequences of excessive use of electronic media 14 , 26 . However, previous research has often reported that children and adolescents spent more than the recommended time 26 . The present study also found similar results, that is, that about 70% of the sampled adolescents aged 11–17 spent more than 2 h per day on the Internet and nearly 30% spent more than 2-h on electronic gaming in a day. This could be attributed to the increased availability of computers/smart-phones and the internet among under-18s 12 . For instance, 97% of Australian households with children aged less than 15 years accessed internet at home in 2016–2017 10 ; as a result, policymakers recommended that parents restrict access to screens (e.g. Internet and electronic games) in children’s bedrooms, monitor children using screens, share screen hours with their children, and to act as role models by reducing their own screen time 14 .

This research has drawn attention to the fact that the average time spent using the internet, which is often more than 4 h during weekdays tends to be negatively associated with academic performance, especially a lower reading and numeracy score, while internet use of more than 2 h during weekends is positively associated with academic performance, particularly having a better reading and writing score and above national standard score. By dividing internet use and gaming by weekdays and weekends, this study find an answer to the mixed evidence found in previous literature 9 . The results of this study clearly show that the non-academic use of internet during weekdays, particularly, spending more than 4 h on internet is harmful for academic performance, whereas, internet use on the weekends is likely to incur a positive effect on academic performance. This result is consistent with a USA study that reported that internet use is positively associated with improved reading skills and higher scores on standardized tests 13 , 27 . It is also reported in the literature that academic performance is better among moderate users of the internet compared to non-users or high level users 13 , 27 , which was in line with the findings of this study. This may be due to the fact that the internet is predominantly a text-based format in which the internet users need to type and read to access most websites effectively 13 . The results of this study indicated that internet use is not harmful to academic performance if it is used moderately, especially, if ensuring very limited use on weekdays. The results of this study further confirmed that timing (weekdays or weekends) of internet use is a factor that needs to be considered.

Regarding electronic gaming, interestingly, the study found that the average time of gaming either in weekdays or weekends is positively associated with academic performance especially for reading scores. These results contradicted previous literatures 1 , 13 , 19 , 27 that have reported negative correlation between electronic games and educational performance in high-school children. The results of this study were consistent with studies conducted in the USA, Europe and other countries that claimed a positive correlation between gaming and academic performance, especially in numeracy and reading skills 28 , 29 . This is may be due to the fact that the instructions for playing most of the electronic games are text-heavy and many electronic games require gamers to solve puzzles 9 , 30 . The literature also found that playing electronic games develops cognitive skills (e.g. mental rotation abilities, dexterity), which can be attributable to better academic achievement 31 , 32 .

Consistent with previous research findings 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , the study also found that adolescents who had addiction tendency to internet usage and/or electronic gaming were less likely to achieve higher scores in reading and numeracy compared to those who had not problematic behaviour. Addiction tendency to Internet/gaming among adolescents was found to be negatively associated with overall academic performance compared to those who were not having addiction tendency, although the variables were not always statistically significant. This is mainly because adolescents’ skipped school and missed classes and tuitions, and provide less effort to do homework due to addictive internet usage and electronic gaming 19 , 35 . The results of this study indicated that parental monitoring and/ or self-regulation (by the users) regarding the timing and intensity of internet use/gaming are essential to outweigh any negative effect of internet use and gaming on academic performance.

Although the present study uses a large nationally representative sample and advances prior research on the academic performance among adolescents who reported using the internet and playing electronic games, the findings of this study also have some limitations that need to be addressed. Firstly, adolescents who reported on the internet use and electronic games relied on self-reported child data without any screening tests or any external validation and thus, results may be overestimated or underestimated. Second, the study primarily addresses the internet use and electronic games as distinct behaviours, as the YMM survey gathered information only on the amount of time spent on internet use and electronic gaming, and included only a few questions related to addiction due to resources and time constraints and did not provide enough information to medically diagnose internet/gaming addiction. Finally, the cross-sectional research design of the data outlawed evaluation of causality and temporality of the observed association of internet use and electronic gaming with the academic performance in adolescents.

This study found that the average time spent on the internet on weekends and electronic gaming (both in weekdays and weekends) is positively associated with academic performance (measured by NAPLAN) of Australian adolescents. However, it confirmed a negative association between addiction tendency (internet use or electronic gaming) and academic performance; nonetheless, most of the adolescents used the internet and played electronic games more than the recommended 2-h limit per day. The study also revealed that further research is required on the development and implementation of interventions aimed at improving parental monitoring and fostering users’ self-regulation to restrict the daily usage of the internet and/or electronic games.

Data description

Young minds matter (YMM) was an Australian nationwide cross-sectional survey, on children aged 4–17 years conducted in 2013–2014 37 . Out of the initial 76,606 households approached, a total of 6,310 parents/caregivers (eligible household response rate 55%) of 4–17 year-old children completed a structured questionnaire via face to face interview and 2967 children aged 11–17 years (eligible children response rate 89%) completed a computer-based self-reported questionnaire privately at home 37 .

Area based sampling was used for the survey. A total of 225 Statistical Area 1 (defined by Australian Bureau of Statistics) areas were selected based on the 2011 Census of Population and Housing. They were stratified by state/territory and by metropolitan versus non-metropolitan (rural/regional) to ensure proportional representation of geographic areas across Australia 38 . However, a small number of samples were excluded, based on most remote areas, homeless children, institutional care and children living in households where interviews could not be conducted in English. The details of the survey and methodology used in the survey can be found in Lawrence et al. 37 .

Following informed consent (both written and verbal) from the primary carers (parents/caregivers), information on the National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) of the children and adolescents were also added to the YMM dataset. The YMM survey is ethically approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia and by the Australian Government Department of Health. In addition, the authors of this study obtained a written approval from Australian Data Archive (ADA) Dataverse to access the YMM dataset. All the researches were done in accordance with relevant ADA Dataverse guidelines and policy/regulations in using YMM datasets.

Outcome variables

The NAPLAN, conducted annually since 2008, is a nationwide standardized test of academic performance for all Australian students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 to assess their skills in reading, writing numeracy, grammar and spelling 39 , 40 . NAPLAN scores from 2010 to 2015, reported by YMM, were used as outcome variables in the models; while NAPLAN data of 2008 (N = 4) and 2009 (N = 29) were excluded for this study in order to reduce the time lag between YMM survey and the NAPLAN test. The NAPLAN gives point-in-time standardized scores, which provide the scope to compare children’s academic performance over time 40 , 41 . The NAPLAN tests are one component of the evaluation and grading phase of each school, and do not substitute for the comprehensive, consistent evaluations provided by teachers on the performance of each student 39 , 41 . All four domains—reading, writing, numeracy and language conventions (grammar and spelling) are in continuous scales in the dataset. The scores are given based on a series of tests; details can be found in 42 . The current study uses only reading, writing and numeracy scores to measure academic performance.

In this study, the National standard score is a combination of three variables: whether the student meets the national standard in reading, writing and numeracy. Based on national average score, a binary outcome variable is also generated. One category is ‘below standard’ if a child scores at least one standard deviation (one below scores) from the national standard in reading, writing and numeracy, and the rest is ‘at/above standard’.

Independent variables

Internet use and electronic gaming.

In the YMM survey, owing to the scope of the survey itself, an extensive set of questions about internet usage and electronic gaming could not be included. Internet usage omitted the time spent in academic purposes and/or related activities. Playing electronic games included playing games on a gaming console (e.g. PlayStation, Xbox, or similar console ) online or using a computer, or mobile phone, or a handled device 12 . The primary independent covariates were average internet use per day and average electronic game-play in hours per day. A combination of hours on weekdays and weekends was separately used in the models. These variables were based on a self-assessed questionnaire where the youths were asked questions regarding daily time spent on the Internet and electronic game-play, specifically on either weekends or weekdays. Since, internet use/game-play for a maximum of 2 h/day is recommended for children and adolescents aged between 5 and 17 years in many developed countries including Australia 14 , 26 ; therefore, to be consistent with the recommended time we preferred to categorize both the time variables of internet use and gaming into three groups with an interval of 2 h each. Internet use was categorized into three groups: (a) ≤ 2 h), (b) 2–4 h, and (c) > 4 h. Similar questions were asked for game-play h. The sample distribution for electronic game-play was skewed; therefore, this variable was categorized into three groups: (a) no game-play (0 h), (b) 1–2 h, and (c) > 2 h.

Other covariates

Family structure and several sociodemographic variables were used in the models to adjust for the differences in individual characteristics, parental inputs and tastes, household characteristics and place of residence. Individual characteristics included age (continuous) and sex of the child (boys, girls) and addiction tendency to internet use and/or game-play of the adolescent. Addiction tendency to internet/game-play was a binary independent variable. It was a combination of five behavioural questions relating to: whether the respondent avoided eating/sleeping due to internet use or game-play; feels bothered when s/he cannot access internet or play electronic games; keeps using internet or playing electronic games even when s/he is not really interested; spends less time with family/friends or on school works due to internet use or game-play; and unsuccessfully tries to spend less time on the internet or playing electronic games. There were four options for each question: never/almost never; not very often; fairly often; and very often. A binary covariate was simulated, where if any four out of five behaviours were reported as for example, fairly often or very often, then it was considered that the respondent had addictive tendency.

Household characteristics included household income (low, medium, high), family type (original, step, blended, sole parent/primary carer, other) 43 and remoteness (major cities, inner regional, outer regional, remote/very remote). Parental inputs and taste included education of primary carer (bachelor, diploma, year 10/11), primary carer’s likelihood of serious mental illness (K6 score -likely; not likely); primary carer’s smoking status (no, yes); and risk of alcoholic related harm by the primary carer (risky, none).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the sample and distributions of the outcome variables were initially assessed. Based on these distributions, the categorization of outcome variables was conducted, as mentioned above. For formal analysis, generalized linear regression models (GLMs) 44 were used, adjusting for the survey weights, which allowed for generalization of the findings. As NAPLAN scores of three areas—reading, writing and numeracy—were continuous variables, linear models were fitted to daily average internet time and electronic game play time. The scores were standardized (mean = 0, SD = 1) for model fitness. The binary logistic model was fitted for the dichotomized national standard outcome variable. Separate models were estimated for internet and electronic gaming on weekends and weekdays.

We estimated three different models, where models varied based on covariates used to adjust the GLMs. Model 1 was adjusted for common sociodemographic factors including age and sex of the child, household income, education of primary carer’s and family type 43 . However, the results of this model did not account for some unobserved household characteristics (e.g. taste, preferences) that are unobserved to the researcher and are arguably correlated with potential outcomes. The effects of unobserved characteristics were reduced by using a comprehensive set of observable characteristics 45 , 46 that were available in YMM data. The issue of unobserved characteristics was addressed by estimating two additional models that include variables by including household characteristics such as parental taste, preference and inputs, and child characteristics in the model. In addition to the variables in Model 1, Model 2 included remoteness, primary carer’s mental health status, smoking status and risk of alcoholic related harm by the primary carer. Model 3 further included internet/game addiction of the adolescent in addition to all the covariates in Model 2. Model 3 was expected to account for a child’s level of unobserved characteristics as the children who were addicted to internet/games were different from others. The model will further show how academic performance is affected by internet/game addiction. The correlation among the variables ‘internet/game addiction’ and ‘internet use’ and ‘gaming’ (during weekdays and weekends) were also assessed, and they were less than 0.5. Multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), which was under 5 for all models, suggesting no multicollinearity 47 .

p value below the threshold of 0.05 was considered the threshold of significance. All analysis was conducted in R (version 3.6.1). R-package survey (version 3.37) was used for modelling which is suited for complex survey samples 48 .

Data availability

The authors declare that they do not have permission to share dataset. However, the datasets of Young Minds Matter (YMM) survey data is available at the Australian Data Archive (ADA) Dataverse on request ( https://doi.org/10.4225/87/LCVEU3 ).

Wang, C. -W., Chan, C. L., Mak, K. -K., Ho, S. -Y., Wong, P. W. & Ho, R. T. Prevalence and correlates of video and Internet gaming addiction among Hong Kong adolescents: a pilot study. Sci. World J . 2014 (2014).

Anderson, E. L., Steen, E. & Stavropoulos, V. Internet use and problematic internet use: a systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 22 , 430–454 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Oliveira, M. P. MTd. et al. Use of internet and electronic games by adolescents at high social risk. Trends Psychol. 25 , 1167–1183 (2017).

Google Scholar

UNICEF. Children in a digital world. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2017)

King, D. L. et al. The impact of prolonged violent video-gaming on adolescent sleep: an experimental study. J. Sleep Res. 22 , 137–143 (2013).

Byrne, J. & Burton, P. Children as Internet users: how can evidence better inform policy debate?. J. Cyber Policy. 2 , 39–52 (2017).

Council, O. Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics 132 , 958 (2013).

Paulus, F. W., Ohmann, S., Von Gontard, A. & Popow, C. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 60 , 645–659 (2018).

Posso, A. Internet usage and educational outcomes among 15-year old Australian students. Int J Commun 10 , 26 (2016).

ABS. 8146.0—Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2016–2017 (2018).

Brand, J. E. Digital Australia 2018 (Interactive Games & Entertainment Association (IGEA), Eveleigh, 2017).

Rikkers, W., Lawrence, D., Hafekost, J. & Zubrick, S. R. Internet use and electronic gaming by children and adolescents with emotional and behavioural problems in Australia–results from the second Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. BMC Public Health 16 , 399 (2016).

Jackson, L. A., Von Eye, A., Witt, E. A., Zhao, Y. & Fitzgerald, H. E. A longitudinal study of the effects of Internet use and videogame playing on academic performance and the roles of gender, race and income in these relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27 , 228–239 (2011).

Yu, M. & Baxter, J. Australian children’s screen time and participation in extracurricular activities. Ann. Stat. Rep. 2016 , 99 (2015).

Rainie, L. & Horrigan, J. A decade of adoption: How the Internet has woven itself into American life. Pew Internet and American Life Project . 25 (2005).

Drummond, A. & Sauer, J. D. Video-games do not negatively impact adolescent academic performance in science, mathematics or reading. PLoS ONE 9 , e87943 (2014).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Green, L., Olafsson, K., Brady, D. & Smahel, D. Excessive Internet use among Australian children (2012).

Livingstone, S. EU kids online. The international encyclopedia of media literacy . 1–17 (2019).

Wright, J. The effects of video game play on academic performance. Mod. Psychol. Stud. 17 , 6 (2011).

Gentile, D. A., Lynch, P. J., Linder, J. R. & Walsh, D. A. The effects of violent video game habits on adolescent hostility, aggressive behaviors, and school performance. J. Adolesc. 27 , 5–22 (2004).

Rosenthal, R. & Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban Rev. 3 , 16–20 (1968).

Willoughby, T. A short-term longitudinal study of Internet and computer game use by adolescent boys and girls: prevalence, frequency of use, and psychosocial predictors. Dev. Psychol. 44 , 195 (2008).

Weis, R. & Cerankosky, B. C. Effects of video-game ownership on young boys’ academic and behavioral functioning: a randomized, controlled study. Psychol. Sci. 21 , 463–470 (2010).

Howell, D. C. The treatment of missing data. The Sage handbook of social science methodology . 208–224 (2007).

Terry, M. and Malik, A. Video gaming as a factor that affects academic performance in grade nine. Online Submission (2018).

Houghton, S. et al. Virtually impossible: limiting Australian children and adolescents daily screen based media use. BMC Public Health. 15 , 5 (2015).

Jackson, L. A., Von Eye, A., Fitzgerald, H. E., Witt, E. A. & Zhao, Y. Internet use, videogame playing and cell phone use as predictors of children’s body mass index (BMI), body weight, academic performance, and social and overall self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27 , 599–604 (2011).

Bowers, A. J. & Berland, M. Does recreational computer use affect high school achievement?. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 61 , 51–69 (2013).

Wittwer, J. & Senkbeil, M. Is students’ computer use at home related to their mathematical performance at school?. Comput. Educ. 50 , 1558–1571 (2008).

Jackson, L. A. et al. Does home internet use influence the academic performance of low-income children?. Dev. Psychol. 42 , 429 (2006).

Barlett, C. P., Anderson, C. A. & Swing, E. L. Video game effects—confirmed, suspected, and speculative: a review of the evidence. Simul. Gaming 40 , 377–403 (2009).

Suziedelyte, A. Can video games affect children's cognitive and non-cognitive skills? UNSW Australian School of Business Research Paper (2012).

Chiu, S.-I., Lee, J.-Z. & Huang, D.-H. Video game addiction in children and teenagers in Taiwan. CyberPsychol. Behav. 7 , 571–581 (2004).

Skoric, M. M., Teo, L. L. C. & Neo, R. L. Children and video games: addiction, engagement, and scholastic achievement. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 12 , 567–572 (2009).

Leung, L. & Lee, P. S. Impact of internet literacy, internet addiction symptoms, and internet activities on academic performance. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 30 , 403–418 (2012).

Xin, M. et al. Online activities, prevalence of Internet addiction and risk factors related to family and school among adolescents in China. Addict. Behav. Rep. 7 , 14–18 (2018).

PubMed Google Scholar

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., et al. The mental health of children and adolescents: report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing (2015).

Hafekost, J. et al. Methodology of young minds matter: the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 50 , 866–875 (2016).

Australian Curriculum ARAA. National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy: Achievement in Reading, Persuasive Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy: National Report for 2011 . Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (2011).

Daraganova, G., Edwards, B. & Sipthorp, M. Using National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) Data in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) . Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (2013).

NAP. NAPLAN (2016).

Australian Curriculum ARAA. National report on schooling in Australia 2009. Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth… (2009).

Vu, X.-B.B., Biswas, R. K., Khanam, R. & Rahman, M. Mental health service use in Australia: the role of family structure and socio-economic status. Children Youth Serv. Rev. 93 , 378–389 (2018).

McCullagh, P. Generalized Linear Models (Routledge, Abingdon, 2019).

Book Google Scholar

Gregg, P., Washbrook, E., Propper, C. & Burgess, S. The effects of a mother’s return to work decision on child development in the UK. Econ. J. 115 , F48–F80 (2005).

Khanam, R. & Nghiem, S. Family income and child cognitive and noncognitive development in Australia: does money matter?. Demography 53 , 597–621 (2016).

Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., Neter, J. & Li, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models (McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York, 2005).

Lumley T. Package ‘survey’. 3 , 30–33 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Western Australia, Roy Morgan Research, the Australian Government Department of Health for conducting the survey, and the Australian Data Archive for giving access to the YMM survey dataset. The authors also would like to thank Dr Barbara Harmes for proofreading the manuscript.

This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Health Research and School of Commerce, University of Southern Queensland, Workstation 15, Room T450, Block T, Toowoomba, QLD, 4350, Australia

Md Irteja Islam & Rasheda Khanam

Maternal and Child Health Division, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), Mohakhali, Dhaka, 1212, Bangladesh

Md Irteja Islam

Transport and Road Safety (TARS) Research Centre, School of Aviation, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia

Raaj Kishore Biswas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.I.I.: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Investigation, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. R.K.B.: Methodology, Software, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original draft preparation. R.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Md Irteja Islam .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Islam, M.I., Biswas, R.K. & Khanam, R. Effect of internet use and electronic game-play on academic performance of Australian children. Sci Rep 10 , 21727 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78916-9

Download citation

Received : 28 August 2020

Accepted : 02 December 2020

Published : 10 December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78916-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

I want to play a game: examining sex differences in the effects of pathological gaming, academic self-efficacy, and academic initiative on academic performance in adolescence.

- Sara Madeleine Kristensen

- Magnus Jørgensen

Education and Information Technologies (2024)

Measurement Invariance of the Lemmens Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-9 Across Age, Gender, and Respondents

- Iulia Maria Coșa

- Anca Dobrean

- Robert Balazsi

Psychiatric Quarterly (2024)

Academic and Social Behaviour Profile of the Primary School Students who Possess and Play Video Games

- E. Vázquez-Cano

- J. M. Ramírez-Hurtado

- C. Pascual-Moscoso

Child Indicators Research (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cent Asian J Glob Health

- v.9(1); 2020

Online Game Addiction and the Level of Depression Among Adolescents in Manila, Philippines

Ryan v. labana.

1 Department of Biology, College of Science, Polytechnic University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Jehan L. Hadjisaid

2 Senior High School, Polytechnic University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Adrian R. Imperial

Kyeth elmerson jumawid, marc jayson m. lupague, daniel c. malicdem, introduction:.

World Health Organization recognizes online game addiction as a mental health condition. The rise of excessive online gaming is emerging in the Philippines, with 29.9 million gamers recorded in the country. The incidence of depression is also increasing in the country. The current correlational analysis evaluated the association between online game addiction and depression in Filipino adolescents.

A paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaire assessing depression and online game addiction was distributed from August to November, 2018. The questionnaire included socio-demographic profiles of the respondents, and the 14-item Video Game Addiction Test (VAT) (Cronbach's α=0.91) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Cronbach's α=0.88) to determine levels of online game addiction and depression, respectively. Multiple regression analyses were used to test the association between depression and online game addiction.

Three hundred adolescents (59% males, 41% females) participated in the study. Fifty-three out of 300 respondents (12.0% males, 5.7% females) had high level of online game addiction as reflected in their high VAT scores. In this study, 37 respondents (6.7% males, 5.7% females) had moderately severe depression and 6 (2.0%) females had severe depression. Online game addiction was positively correlated with depression in this study ( r =0.31; p <0.001). When multiple regression analysis was computed, depression was found to be a predictor of online game addiction ( Coefficient =0.0121; 95% CI-8.1924 - 0.0242; p =0.05).

Conclusions:

Depression, as associated with online game addiction, is a serious threat that needs to be addressed. High level of online game addiction, as positively correlated to the rate of depression among adolescents in Manila, could potentially be attributed to the booming internet industry and lack of suffiicent mental health interventions in the country. Recommended interventions include strengthening depression management among adolescents and improving mental health services for this vulnerable population groups in schools and within the communities.

Based on the report of the European Mobile Game Market in 2016, there were more than 2.5 billion video gamers across the globe. 1 Several studies have found that the majority of these players were adolescents aged 12-17 years, 2 - 5 with more usage among males than females. 6 In 2017, newzoo.com reported that the active gamers in the Philippines were 52% males and 48% females. 7 In the US, 60% of the video gamers were males and 40% are females. 6 Studies have shown that there are similarities between males and females in regard to choice of games, behavior toward video gaming, and motives for engaging in this activity. 8 Some of the reported reasons to engage in video games include having fun and for recreation, 9 - 10 to de-stress, 11 – 12 and to avoid real life issues. 13 – 14 The prevalence of video gaming addiction varies from region to region based on the socio-cultural context and the criteria used for the assessment. 15 However, it is well established that video gaming is addictive, 16 – 18 and there is clinical evidence for the symptoms of biopsychosocial problems among video game addicts. 19 It is a serious threat to the mental and psychosocial aspects of an individual, as it lead to stress, loss of control, aggression, anxiety, and mood modification. 20 – 21

In the Philippines, online gaming is an emerging industry. The country ranks 29 th in game revenues across the globe. In 2017, there were more than 29.9 million gamers recorded in the country. Most of the gamers were 21–35 years of age, followed by the adolescents 10–20 years of age. 7 Adolescents accounted for 30.5% of the total population in the country. 22 In general, this age group is already facing mental health issues, such as anxiety, mood disorders, and depression. This concern gets more alarming as rates of suicide among high school and college students are growing worldwide. 23

World Health Organization lists video game addiction as a mental health problem. 24 Psychiatric research reported evidence on the links between depression and video game addiction. Among the findings are MRI scans of video game addicts showing disruption of some brain parts and overriding of the 'emotional' part with the 'executive' part. 25 A study in China has also reported that gamers are at increased risk of being depressed in comparison to those who did not play video games. 26 In the field of neuroscience, depression caused by online game addiction is explained as a reduction of synaptic activities due to permanent changes in the dopaminergic pathways. This means that long exposure to online gaming causes changes in a person's sense of natural rewards, often making activities less pleasurable. This neuroadaptation is also associated with chronic depression. 27

There is a paucity of studies on video game addiction in the Philippines, making its implications not well understood. There are reports of the impact of video game addiction on the academic performance of the gamers, 28 – 30 but no study has been found associating video game addiction and depression in the Philippine setting. Based on the 2004 report from the Department of Health in the Philippines, over 4.5 million cases of depression were reported in the country. Recently, World Health Organization reported that 11.6% of the 8,761 surveyed young Filipinos considered committing suicide; 16.8% of them (of 8,761) had attempted it. 31 This phenomenon is said to be instigated by several factors, including the individual's exposures to technology. Video game addiction and depression are two emerging public health issues among adolescents in the Philippines. 31 – 32 This small-scale study aims to understand the association between these two factors and produce baseline information that can be used in formulating evidence-based public health policies in the country.

Research site and participants

This study was conducted in the months of August-November 2018 in the city of Manila, the capital of the Philippines. Manila is situated on the eastern shores of Manila Bay, on the western edge of Luzon (14∘35’45”N 120∘58’38”E). It is one of the most urbanized areas and the center of technological innovation in the country. It has a population of 1.78 million, based on 2016 census. 33 Manila covers 896 barangays (villages), which are grouped into six districts. Based on the 2010 census, the total population of Filipino adolescents, regardless of sex, was 166,391. 34 This population estimate was used for computing the sample size needed for this study. Sample size calculation was estimated using the online calculator from OpenEpi. 35 The completion rate of the questionnaires was 78.13%, for a total of 300 consenting respondents who were all online video gamers. They were selected if they were residents of Manila City and reported playing video games on the regular basis.

Map of Manila from the National Capital Region of the Philippines

Instruments

The study used a paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaire. To determine the level of online game addiction of the respondents, the study used the Video Game Addiction Test (VAT) developed by van Rooij et al . 36 from the 14-item version of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS). 37 VAT was utilized in several studies among adolescents in the past, and it has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity. The scale outcomes were found to be comparable across gender, ethnicity, and learning year, making it a helpful tool in studying video game addiction among various subgroups. 36 The survey contains questions in five categories: loss of control, conflict, salience, mood modification, and withdrawal symptoms. Each question was measured on a 5-point scale: 0–never to 4–very often. The results were then used as an indicator of the level of addiction. This study adapted the calculations conducted by van Rooij et al. 38 wherein the average scale scores of all the respondents were arranged from 0-4 and then were divided into two groups. The first group had an average of 0-2 or 'never' to 'sometimes', while the second group had an average of 3-4 or 'often' to 'very often'. The latter group was considered to have the highest level of problematic gaming or, in this study, with online game addiction. 38 The internal reliability of the VAT in this study was excellent at Cronbach's α of 0.91.

The level of depression of the respondents was determined by using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). 39 It is a 9-item depression module taken from the full PHQ. The questionnaire allows the respondents to rate their health status in the past six weeks. There are 9 diagnostic questions in which the respondents rated 0 for 'not at all', 1 for 'several days', 2 for 'more than half the days', and 3 for 'nearly every day'. The total of the PHQ-9 scores was used to measure severity of depression. Since there are 9 items in the questionnaire and each question can be rated from 0-3, the PHQ-9 scores can range from 0-27. The score was interpreted as ‘no depression’ (0-4 points), ‘mild depression’ (5-9 points), ‘moderate depression’ (10-14 points), ‘moderately severe depression’ (15-19 points), and ‘severe depression’ (20-27 points). 39 In this study, the internal reliability of PHQ-9 had a Cronbach's α of 0.88.

Data gathering procedure

The study randomly surveyed gamers in various parts of Manila. Since there are no reliable records of the gamers in the area available for research, various sampling techniques were utilized. A convenience sampling was done by visiting internet cafes in the city and requesting the gamers to answer the questionnaire during their time-out (from the game). A verbal consent was provided by each respondent after hearing a brief explanation of the research objectives and the necessary instructions. While answering the questionnaire, the respondents were assisted by the investigator for any clarifications and questions. The questionnaire was completed by the respondents in approximately 2.5 minutes. Other procedures included snowball sampling, accidental, and voluntary response sampling after the distribution of invitation to respond among internet cafes, gamers’ social media groups/sites, and online gamers’ organizations. The study was approved by the ethical board of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines.

Statistical analysis

All the responses from the questionnaires were inputted into MS Excel and into SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics of responses were computed and included the frequencies ( f ), percentages (%), averages x and standard deviations (SD). The association between online game addiction and depression was analyzed using Pearson's correlation and was further analyzed using a multiple regression analysis. The study hypothesized that there is no significant correlation between online game addiction and level of depression among adolescents in the City of Manila, Philippines. All statistical results were considered significant at the p value <0.05.

Profile of the respondents

A total of 300 consenting adolescents participated in the study. There were more males ( n =176; 59%) than females ( n =124; 41%) who participated in the study. Most of the respondents were adolescents (aged less than 19 years), except for the six respondents who were already 20 years old during the data gathering. The mean age of the participants was 17 years old (SD=0.90). Figure 2 presents the profiles of the respondents based on their gender and age characteristics. The VAT analysis shows that there were more males (12.0%) who were addicted to online games than females (5.7%). Meanwhile, 15-, 17-, and 18-year old respondents had the highest VAT scores among the six age groups.

Profiles of the respondents based on gender and age

Level of online game addiction

The 14-item VAT was ranked from the highest to the lowest mean score to understand the common conditions experienced by the respondents. The item with the highest mean was No. 13: Do you game because you are feeling down? ( x =2.1, SD=1.40). This question had the third greatest number of “4-very often” ratings ( N =46/300). It was followed by the item No. 3: Do others (e.g., parents or friends) say you should spend less time on games? ( x =2.06, SD=1.41).. The third item with the highest mean score was item No. 7: Do you look forward to the next time you can game? ( x =2.0, SD=1.27). The item with the highest number of “4-very often” rating was item No. 14: Do you game to forget about problem? ( N =67/300). Items 12 and 2 also had high mean scores: Do you neglect to do your homework because you prefer to game? (Item 12; x =1.98, SD=1.34); and Do you continue to use the games despite your intention to stop ? (Item 2; x =1.84, SD=1.20).

Levels of online game addiction based on gender and age

Level of depression

The PHQ-9 was used to quantify the symptoms of depression of the respondents and identify its severity. The majority of the respondents demonstrated no depression (47%), followed by having mild depression (22%), and moderate depression (17%). Of note, the current study revealed 12% of the respondents had moderately severe depression and 2% had severe depression. We found that higher PHQ-9 scores were associated with decreased functional status. The most common symptoms reported by the respondents based on the mean scores of each item in PHQ-9 include …feeling tired or having little energy ( x =1.89, SD=1.30), …poor appetite or overeating ( x =1.87, SD=1.37), … feeling down, depressed or hopeless ( x =1.81, SD=1.18), …trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much ( x =1.78, SD=1.33), and …trouble concentrating on things, such as reading newspaper or watching television ( x =1.75, SD=1.40). Interestingly, the six respondents who were identified to have “severe” depression were all females, and four of them had high VAT scores.

Level of depression of the respondents based on the PHQ-9 scores

Association between online game addiction and depression

The association between online game addiction based on the VAT scores and the level of depression among the respondents was evaluated through Pearson's correlation analysis. Results ( Table 3 ) show that the level of online game addiction was positively correlated with the level of depression ( r =0.31, p <0.001) but was not significantly correlated with age or gender ( r =-0.80, p <0.171 and r = 0.10, p <0.097, respectively).

Pearson's correlation coefficient among gender, age, online game addiction, and depression of the adolescents in Manila

A multiple linear regression was calculated to predict online game addiction based on gender and depression. This regression analysis was performed with all participants and with the subset of participants with high VAT scores, which indicated online game addiction. A significant regression equation was found (F(2.50)= 2.247, 0.10), with an R 2 of 0.082. Table 4 shows that depression was a significant predictor of online game addiction.

Multiple regression analysis for prediction of online game addiction based on age and level of depression

The correlation between online game addiction and the levels of depression in this study was weak but statistically significant. This positive correlation was previously reported in other research studies across the globe. 40 – 41 In a study conducted by Rikkers et al. 40 among children and adolescents (11-17 years old) in Australia, electronic gaming was positively associated with emotional and behavioral problems including depression. Longer gaming hours were also associated with severe depressive symptoms, somatic symptoms, and pain symptoms among young people in Taiwan. 41 Online game addiction was associated by Zamani et al. 42 not only with depression but also with sleep disorder, physical complaints, and social dysfunctions of students in Iran. In a study conducted by Dong et al., 43 depression came out as one of the outcomes of the internet addiction disorder.

In the current study, most of the respondents looked forward to the next time they would game, with the most common reason of engaging in games reported to be easing the moments of feeling down. Another reason of the respondents’ addiction to online games was that they want to forget about problems. It is considered as one of the core symptoms of addiction as described by Brown. 44 The second most common experience of the respondents was the 'inability to voluntarily reduce the time spent on online games', which is another core symptom of addiction. 45 Most of the respondents admitted that they were getting advice from their parents or friends to spend less time on games, but they could not control it, despite their intention to stop. In fact, gaming negatively affected homework completion among many study participants. This effect was previously studied among high school students in Los Baños, Philippines, where the video gamers had 39% probability to fail in school. In this previously published study, 6 out of 10 video gamers spent their daily allowances on computer games, giving them access to continuously spend their time playing. 29 The addiction of the adolescents in Manila could have been influenced by the ubiquitous nature of internet in the city. Internet cafes are very accessible in the country, and they are thriving in almost all corners of the city. In addition, the rent for internet and online games in Metro Manila costs 10 to 20 pesos per hour only (US $0.19 to US $0.38 per hour), making playing video games affordable. Some internet hubs are even offering discounts and promotions for longer stays of 10-12 straight hours of playing online games.

Based on the most cited symptoms of the respondents in this study, it could be implied that adolescents cope with their emotional distress by playing online games. This means that the high occurrence of online game addiction goes along with the high occurrence of depression among the same group. In regard to depression, most respondents in this study were feeling tired, having poor appetite, feeling hopeless, having trouble falling asleep, or having trouble concentrating on things that require enough attention, like reading books. These symptoms were also reported by Schmit et al. 45 as related to online game addiction, where the people who spent longer hours playing online games got higher scores for loneliness and isolation. This study did not capture the number of hours spent by the respondents in online games, which could be incorporated in the next study for further analysis.

Depression, as associated to online game addiction, may lead to anxiety, compulsion, and suicide ideations. 46 This is a serious threat to the population health that needs to be addressed. Interventions may include strengthening depression management among adolescents, either in school or in the community. There are several ways to manage depression. The schools and the community should reinforce sports by making it more challenging, engaging, and motivating. In the Philippines, numerous factors make receiving mental health care a challenge. There is only one psychiatrist for every 250,000 mentally ill patients, budget dedicated to mental health interventions is limited, 47 a guidance and counseling system has not yet matured, 48 and there was even a report that online counseling was preferred by the students than its face-to-face counterpart. 49 The poor availability of the mental health interventions in the country may lead to upsurge of depression cases among adolescents. Meanwhile, the booming online game industry in the country leads to the increased numbers of addicted adolescents to online game addiction. Policy makers, the government, and its stakeholders should start addressing these issues before it becomes an even bigger health concern, especially in the face of ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.