This is what the racial education gap in the US looks like right now

Racial achievement gaps in the United States has been slow and unsteady. Image: Unsplash/Santi Vedrí

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} David Elliott

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, education, gender and work.

- Racial achievement gaps in the United States are narrowing, a Stanford University data project shows.

- But progress has been slow and unsteady – and gaps are still large across much of the country.

- COVID-19 could widen existing inequalities in education.

- The World Economic Forum will be exploring the issues around growing income inequality as part of The Jobs Reset Summit .

In the United States today, the average Black and Hispanic students are about three years ahead of where their parents were in maths skills.

They’re roughly two to three years ahead of them in reading, too.

And while white students’ test scores in these subjects have also improved, they’re not rising by as much. This means racial achievement gaps – a key way of monitoring whether all students have access to a good education – in the country are narrowing, research by Stanford University shows.

But while the trend suggests progress is being made in improving racial educational disparities, it doesn’t show the full picture. Progress, the university says, has been slow and uneven.

Have you read?

How can africa prepare its education system for the post-covid world, higher education: do we value degrees in completely the wrong way, this innovative solution is helping indian children get an education during the pandemic.

Standardized tests

Stanford’s Educational Opportunity Monitoring Project uses average standardized test scores for nine-, 13- and 17-year-olds to measure these achievement gaps.

It’s able to do this because the same tests have been used by the National Assessment of Educational Progress to observe maths and reading skills since the 1970s.

In the following decades, as the above chart shows, achievement gaps have significantly declined in all age groups and in both maths and reading. But it’s been something of a roller-coaster.

Substantial progress stalled at the end of the 1980s and throughout the 1990s and in some cases the gaps grew larger. Since then, they’ve been declining steadily and are now significantly smaller than they were in the 1970s.

But these gaps are still “very large”. In fact, the difference in standardized test scores between white and Black students currently amounts to roughly two years of education. And the gap between white and Hispanic students is almost as big.

Schools not to blame

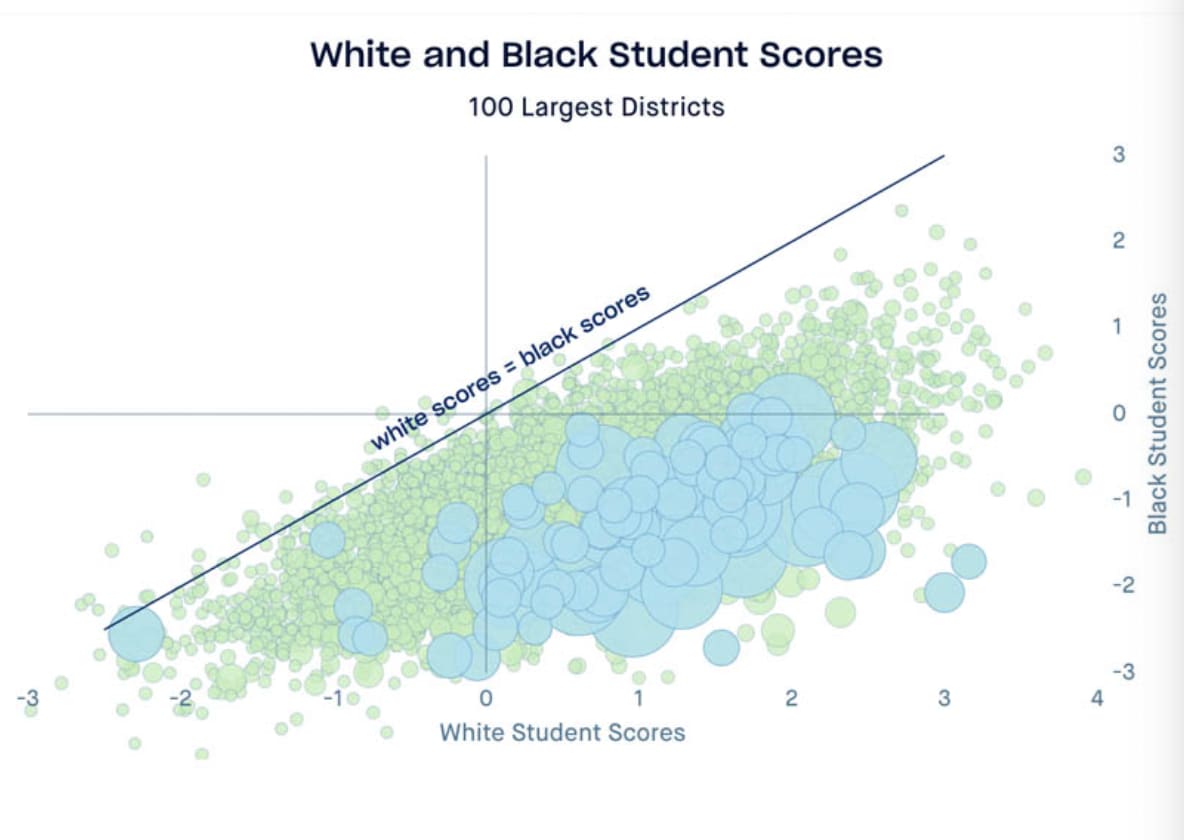

This disparity exists across the US. Racial achievement gaps have narrowed in most states – although they’ve widened in a small number. In almost all of the country’s 100 largest school districts , though, there’s a big achievement gap between white and Black students.

So why is this? Stanford says its data doesn’t support the common argument that schools themselves are to blame for low average test scores, which is often made because white students tend to live in wealthier communities where schools are presumed to be better.

In fact, it says, the scores actually represent gaps in educational opportunity, which can be traced back to a child’s early experiences. These experiences are formed at home, in childcare and preschool, and in communities – and they provide opportunities to develop socioemotional and academic capacities.

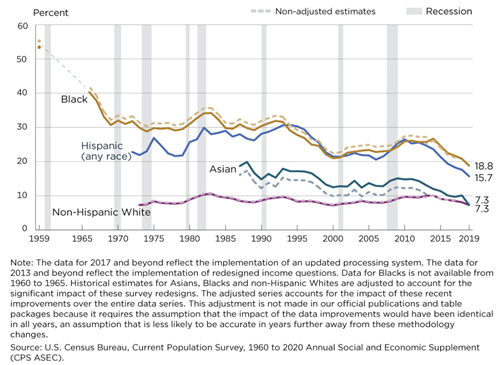

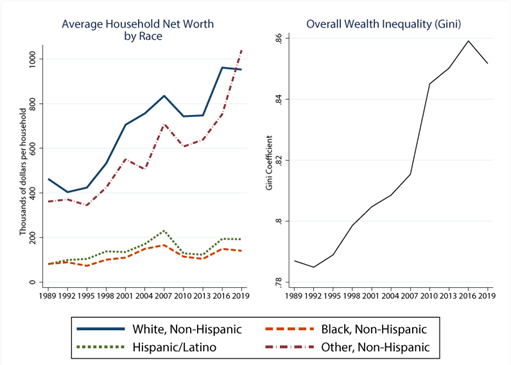

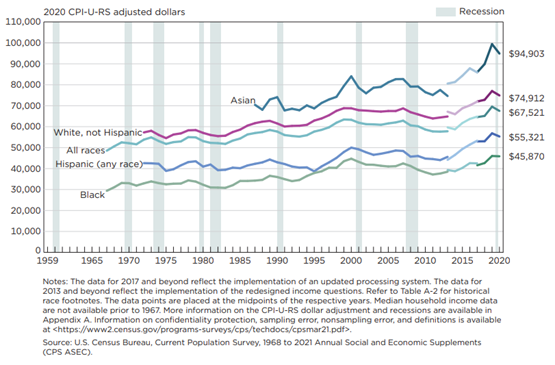

Higher-income families are more likely to be able to provide these opportunities to their children, so a family’s socioeconomic resources are strongly related to educational outcomes , Stanford says. It notes that in the US, Black and Hispanic children’s parents typically have lower incomes and levels of educational attainment than those of white children.

Other factors, such as patterns of residential and school segregation and a state’s educational and social policies, could also have a role in the size of achievement gaps.

And discipline could play its part, too, according to another Stanford study. It linked the achievement gap between Black and white students to the fact that the former are punished more harshly for similar misbehaviour, for example being more likely to be suspended from school than the latter.

Long-term effects

Stanford says using data to map race and poverty could provide the insights needed to help improve educational opportunity for all children.

And this kind of insight is needed now more than ever. The school shutdowns forced by COVID-19 could have exacerbated existing achievement gaps , according to research from McKinsey. The consultancy says the resulting learning losses – predicted to be greater for low-income Black and Hispanic students – could have long-term effects on the economic well-being of the affected children.

Black and Hispanic families are less likely to have high-speed internet at home, making distance learning difficult. And students living in low-income neighbourhoods are less likely to have had decent home schooling, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Earlier in the pandemic, it said coronavirus would "explode" achievement gaps , suggesting it could expand them by the equivalent of another half a year of schooling.

The World Economic Forum’s Jobs Reset Summit brings together leaders from business, government, civil society, media and the broader public to shape a new agenda for growth, jobs, skills and equity.

The two-day virtual event, being held on 1-2 June 2021, will address the most critical areas of debate, articulate pathways for action, and mobilize the most influential leaders and organizations to work together to accelerate progress.

The Summit will develop new frameworks, shape innovative solutions and accelerate action on four thematic pillars: Economic Growth, Revival and Transformation; Work, Wages and Job Creation; Education, Skills and Lifelong Learning; and Equity, Inclusion and Social Justice.

The World Economic Forum will be exploring the issues around growing income inequality, and what to do about it, as part of The Jobs Reset Summit .

The summit will look at ways to shape more inclusive, fair and sustainable organizations, economies and societies as we emerge from the current crisis.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Education and Skills .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How focused giving can unlock billions and catapult women’s wealth

Mark Muckerheide

May 21, 2024

AI is changing the shape of leadership – how can business leaders prepare?

Ana Paula Assis

May 10, 2024

From virtual tutors to accessible textbooks: 5 ways AI is transforming education

Andrea Willige

These are the top ranking universities in Asia for 2024

May 8, 2024

Globally young people are investing more than ever, but do they have the best tools to do so?

Hallie Spear

May 7, 2024

Reskilling Revolution: The Role of AI in Education 4.0

U.S. Government Accountability Office

Racial Disparities in Education and the Role of Government

The death of George Floyd and other Black men and women has prompted demonstrations across the country and brought more attention to the issues of racial inequality. Over the past several years, GAO has been asked to examine various racial inequalities in public programs and we have made recommendations to address them.

Today is the first of 3 blog posts in which we will address these reports. The first deals with equality in education.

School Discipline

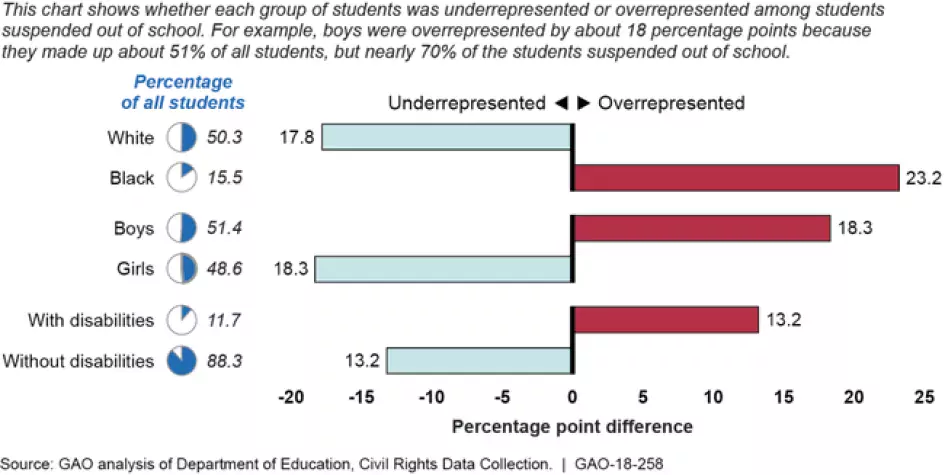

Unequal treatment can start at a young age. In 2018 , we reported that starting in pre-school, children as young as 3 and 4 have been suspended and expelled from school—a pattern that can continue throughout a child’s education. In K-12 public schools, Black students, boys, and students with disabilities were disproportionately disciplined (e.g., suspended or expelled), according to our review of the Department of Education’s national civil rights data.

These disparities were widespread and persisted regardless of the type of disciplinary action, level of school poverty, or type of public school attended. For example, while only 15.5% of public school students were Black, about 39% of students suspended from school were Black—an overrepresentation of about 23 percentage points (see figure).

Students Suspended from School Compared to Student Population, by Race, Sex, and Disability Status, School Year 2013-14

Note: Disparities in student discipline such as those presented in this figure may support a finding of discrimination, but taken alone, do not establish whether unlawful discrimination has occurred .

Minority students may also be more likely to attend alternative public schools because of issues like poor grades and disruptive behavior. In 2019 , we found that Black boys transferred to alternative schools at rates higher than any other group for disciplinary reasons, and that they, along with Hispanic boys and boys with disabilities, attended alternative schools in greater proportions than they did regular public schools attended by the majority of U.S. public school students. For example, Black boys accounted for 16 percent of students at alternative schools, but only 8 percent of students at regular public schools in 2015-16.

Education Quality and Access

The link between racial and ethnic minorities and poverty is long-standing. Studies have noted concerns about this segment of the population that falls at the intersection of poverty and minority status in schools and how this affects their access to quality education. In 2018 , we reported that during high school, students in high-poverty areas had less access to college-prep courses. Schools in high-poverty areas were also less likely to offer math and science courses than most public 4-year colleges expected students to take in high school. The racial composition of the highest poverty schools was also 80% Black or Hispanic.

The Department of Education has several initiatives to help students prepare for college. For example, GEAR UP (Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs) seeks to increase the number of low-income students who are prepared to enter and succeed in postsecondary education. In 2016, Education awarded about $323 million in grants through GEAR UP.

In our 2018 report, we described an investigation the Department of Education conducted in 2014 looking at whether Black students in a Virginia school district had the same access to educational opportunities as other students. It found a significant disparity between the numbers of Black and White high school students who take AP, advanced courses, and dual-credit programs.

Addressing Disparity in Schools

So, what can be done to identify and address racial disparities in K-12 public schools? In 2016 , we recommended that the Department of Education, which is to ensure equal access to education and promote educational excellence through vigorous enforcement of civil rights in our nation’s schools, routinely analyze its Civil Rights dataset, which could help it identify issues and patterns of disparities. Our recommendation was implemented in 2018.

The Department of Justice also plays a role in enforcing federal civil rights laws in the context of K-12 education. For example, it monitors and enforces open federal school desegregation orders where Justice is a party to the litigation. At the time of our study, many of these desegregation orders had been in place for 30 and 40 years. For example, in a 2014 opinion in a long-standing desegregation case, the court described a long period of dormancy in the case and stated that lack of activity had taken its toll, noting, that the district had not submitted the annual reports required under the consent order to the court for the past 20 years. In 2016, we recommended that the Department of Justice systematically track key summary information across its portfolio of open desegregation cases to help inform its monitoring. Our recommendation was implemented in 2019.

To learn more about GAO’s work on education, visit our key issues pages on Ensuring Access to Safe, Quality K-12 Education and Postsecondary Education Access and Affordability .

Comments on GAO’s WatchBlog? Contact [email protected] .

GAO Contacts

Related Posts

Growing Disparities in Retirement Account Savings

Back to School—Obstacles to Educating K-12 Students Persist

What Financial Aid Offers Don’t Tell You About the Cost of College

Related products, k-12 education: discipline disparities for black students, boys, and students with disabilities, product number, k-12 education: certain groups of students attend alternative schools in greater proportions than they do other schools, k-12 education: public high schools with more students in poverty and smaller schools provide fewer academic offerings to prepare for college.

GAO's mission is to provide Congress with fact-based, nonpartisan information that can help improve federal government performance and ensure accountability for the benefit of the American people. GAO launched its WatchBlog in January, 2014, as part of its continuing effort to reach its audiences—Congress and the American people—where they are currently looking for information.

The blog format allows GAO to provide a little more context about its work than it can offer on its other social media platforms. Posts will tie GAO work to current events and the news; show how GAO’s work is affecting agencies or legislation; highlight reports, testimonies, and issue areas where GAO does work; and provide information about GAO itself, among other things.

Please send any feedback on GAO's WatchBlog to [email protected] .

Cornell Chronicle

- Architecture & Design

- Arts & Humanities

- Business, Economics & Entrepreneurship

- Computing & Information Sciences

- Energy, Environment & Sustainability

- Food & Agriculture

- Global Reach

- Health, Nutrition & Medicine

- Law, Government & Public Policy

- Life Sciences & Veterinary Medicine

- Physical Sciences & Engineering

- Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Coronavirus

- News & Events

- Public Engagement

- New York City

- Photos of the Week

- Big Red Sports

- Freedom of Expression

- Student Life

- University Statements

- Around Cornell

- All Stories

- In the News

- Expert Quotes

- Cornellians

Income, segregated schools drive Black-white education gaps

By james dean, cornell chronicle.

Given the same levels of family, school and neighborhood hardship, Black students would be more likely than white students to complete high school and attend college – reversing current disparities, finds new research co-authored by Cornell sociologist Peter Rich .

Accounting for the unequal contexts in which Black and white children grow up and go to school also narrows test-score gaps substantially – by more than 60%, according to the study, which followed nearly 130,000 Michigan students from kindergarten through college enrollment.

The researchers say the findings show that a generation of federal education reforms aimed at closing racial gaps in achievement and attainment has not adequately addressed their two primary drivers: systemic economic inequality, and severely segregated schools.

“Our analysis reveals a stark divide in the social origins of Black and white children coming of age in the beginning of the 21st century – and the toll this divide takes on educational inequality,” the authors write.

Rich, an assistant professor of sociology and demographer in the Cornell Jeb E. Brooks School of Public Policy, is the author with Katherine Michelmore, Ph.D. ’14, associate professor of public policy at the University of Michigan, of “ Contextual Origins of Black-White Educational Disparities in the 21st Century: Evaluating Long-Term Disadvantage Across Three Domains ,” published Oct. 1 in Social Forces.

Sociologists and policymakers have long sought to assess the extent to which family background, school quality and neighborhood environment each contribute to educational disparities.

Rich and Michelmore’s work updates that understanding for the No Child Left Behind era, by tracking students educated entirely after passage of the 2001 legislation focused on school accountability and choice. Michigan offered an ideal case study, they said, since its students mirror the nation demographically and could be observed over 16 years, from 2002 to 2018. The authors obtained restricted access to student records through a partnership with the Michigan Education Research Initiative and the Michigan Department of Education.

Students’ eligibility for subsidized lunches provided a measure of family economic hardship. Roughly half of all white students were disadvantaged at some point in time, compared with over 90% of Black students. The researchers also created indexes of school and neighborhood disadvantage, including factors such a school’s percentage of low-income students and average scores on eighth- and 11th-grade math tests, or a neighborhood’s poverty and unemployment rates.

Controlling for disadvantage across each context over time, the scholars determined that, consistent with prior research, family resources explain by far the biggest share of Black-white education gaps.

“This finding implies that material differences in the contexts inherited by Black and white children – rather than individual effort – drive the large education gaps we observe,” they write. “These trends have persisted through the recent era of federal accountability reforms.”

After family background, Rich and Michelmore found that schools – specifically, schools that are highly segregated due to systemic inequality in wealth and housing – are “consequential,” disproportionately exposing Black students to disadvantage for longer durations.

“Results from our study support concerns that schools exacerbate Black-white inequality,” they write, countering recent debates suggesting that neighborhood context primarily drives differences in student outcomes.

When they controlled for all three contexts together, the researchers found that gaps of nearly 13% in high school graduation and 17% in college enrollment were not only eliminated but reversed, and disparities in test scores narrowed dramatically.

Strengthening those insights, they said, was a longitudinal methodology that more accurately captured the effects of economic hardship over students’ careers until college. Researchers commonly rely on data reported for a single year, they said, which can obscure distinctions between students who are eligible for subsidized lunches consistently, sporadically or never.

“If you only look at a snapshot in time, you’re missing the true portrait of a student’s family economic hardship,” said Rich, a faculty affiliate in Cornell’s Center for the Study of Inequality . “That’s especially important for questions around racial inequality, because Black children are far more likely to live in economic hardship for longer periods of time.”

The authors said their analysis suggests a need for complex policy solutions addressing systemic inequities. Despite decades of ostensibly race-neutral policies, they concluded, Black-white educational disparities persist because of a long history of racial exclusion that has limited Black Americans’ access to homeownership, high-achieving schools, college degrees and high-paying jobs.

“We underscore the relevance of this study to renewed attention to systemic racism as an urgent crisis,” they write. “Our findings amplify the argument that uprooting systemic racism requires an ongoing confrontation with how this history warps Black and white childhood opportunities.”

The research was partly funded by the Cornell Population Center and the Center for Aging and Policy Studies , a consortium based at Syracuse University.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

You might also like

Gallery Heading

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

How covid taught america about inequity in education.

Harvard Correspondent

Remote learning turned spotlight on gaps in resources, funding, and tech — but also offered hints on reform

“Unequal” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. This part looks at how the pandemic called attention to issues surrounding the racial achievement gap in America.

The pandemic has disrupted education nationwide, turning a spotlight on existing racial and economic disparities, and creating the potential for a lost generation. Even before the outbreak, students in vulnerable communities — particularly predominately Black, Indigenous, and other majority-minority areas — were already facing inequality in everything from resources (ranging from books to counselors) to student-teacher ratios and extracurriculars.

The additional stressors of systemic racism and the trauma induced by poverty and violence, both cited as aggravating health and wellness as at a Weatherhead Institute panel , pose serious obstacles to learning as well. “Before the pandemic, children and families who are marginalized were living under such challenging conditions that it made it difficult for them to get a high-quality education,” said Paul Reville, founder and director of the Education Redesign Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (GSE).

Educators hope that the may triggers a broader conversation about reform and renewed efforts to narrow the longstanding racial achievement gap. They say that research shows virtually all of the nation’s schoolchildren have fallen behind, with students of color having lost the most ground, particularly in math. They also note that the full-time reopening of schools presents opportunities to introduce changes and that some of the lessons from remote learning, particularly in the area of technology, can be put to use to help students catch up from the pandemic as well as to begin to level the playing field.

The disparities laid bare by the COVID-19 outbreak became apparent from the first shutdowns. “The good news, of course, is that many schools were very fast in finding all kinds of ways to try to reach kids,” said Fernando M. Reimers , Ford Foundation Professor of the Practice in International Education and director of GSE’s Global Education Innovation Initiative and International Education Policy Program. He cautioned, however, that “those arrangements don’t begin to compare with what we’re able to do when kids could come to school, and they are particularly deficient at reaching the most vulnerable kids.” In addition, it turned out that many students simply lacked access.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right. You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it,” says Fernando Reimers of the Graduate School of Education.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

The rate of limited digital access for households was at 42 percent during last spring’s shutdowns, before drifting down to about 31 percent this fall, suggesting that school districts improved their adaptation to remote learning, according to an analysis by the UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge of U.S. Census data. (Indeed, Education Week and other sources reported that school districts around the nation rushed to hand out millions of laptops, tablets, and Chromebooks in the months after going remote.)

The report also makes clear the degree of racial and economic digital inequality. Black and Hispanic households with school-aged children were 1.3 to 1.4 times as likely as white ones to face limited access to computers and the internet, and more than two in five low-income households had only limited access. It’s a problem that could have far-reaching consequences given that young students of color are much more likely to live in remote-only districts.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right,” said Reimers. “You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it.” Too many students, he said, “have no connectivity. They have no devices, or they have no home circumstances that provide them support.”

The issues extend beyond the technology. “There is something wonderful in being in contact with other humans, having a human who tells you, ‘It’s great to see you. How are things going at home?’” Reimers said. “I’ve done 35 case studies of innovative practices around the world. They all prioritize social, emotional well-being. Checking in with the kids. Making sure there is a touchpoint every day between a teacher and a student.”

The difference, said Reville, is apparent when comparing students from different economic circumstances. Students whose parents “could afford to hire a tutor … can compensate,” he said. “Those kids are going to do pretty well at keeping up. Whereas, if you’re in a single-parent family and mom is working two or three jobs to put food on the table, she can’t be home. It’s impossible for her to keep up and keep her kids connected.

“If you lose the connection, you lose the kid.”

“COVID just revealed how serious those inequities are,” said GSE Dean Bridget Long , the Saris Professor of Education and Economics. “It has disproportionately hurt low-income students, students with special needs, and school systems that are under-resourced.”

This disruption carries throughout the education process, from elementary school students (some of whom have simply stopped logging on to their online classes) through declining participation in higher education. Community colleges, for example, have “traditionally been a gateway for low-income students” into the professional classes, said Long, whose research focuses on issues of affordability and access. “COVID has just made all of those issues 10 times worse,” she said. “That’s where enrollment has fallen the most.”

In addition to highlighting such disparities, these losses underline a structural issue in public education. Many schools are under-resourced, and the major reason involves sources of school funding. A 2019 study found that predominantly white districts got $23 billion more than their non-white counterparts serving about the same number of students. The discrepancy is because property taxes are the primary source of funding for schools, and white districts tend to be wealthier than those of color.

The problem of resources extends beyond teachers, aides, equipment, and supplies, as schools have been tasked with an increasing number of responsibilities, from the basics of education to feeding and caring for the mental health of both students and their families.

“You think about schools and academics, but what COVID really made clear was that schools do so much more than that,” said Long. A child’s school, she stressed “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care.”

“You think about schools and academics” … but a child’s school “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care,” stressed GSE Dean Bridget Long.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

This safety net has been shredded just as more students need it. “We have 400,000 deaths and those are disproportionately affecting communities of color,” said Long. “So you can imagine the kids that are in those households. Are they able to come to school and learn when they’re dealing with this trauma?”

The damage is felt by the whole families. In an upcoming paper, focusing on parents of children ages 5 to 7, Cindy H. Liu, director of Harvard Medical School’s Developmental Risk and Cultural Disparities Laboratory , looks at the effects of COVID-related stress on parent’ mental health. This stress — from both health risks and grief — “likely has ramifications for those groups who are disadvantaged, particularly in getting support, as it exacerbates existing disparities in obtaining resources,” she said via email. “The unfortunate reality is that the pandemic is limiting the tangible supports [like childcare] that parents might actually need.”

Educators are overwhelmed as well. “Teachers are doing a phenomenal job connecting with students,” Long said about their performance online. “But they’ve lost the whole system — access to counselors, access to additional staff members and support. They’ve lost access to information. One clue is that the reporting of child abuse going down. It’s not that we think that child abuse is actually going down, but because you don’t have a set of adults watching and being with kids, it’s not being reported.”

The repercussions are chilling. “As we resume in-person education on a normal basis, we’re dealing with enormous gaps,” said Reville. “Some kids will come back with such educational deficits that unless their schools have a very well thought-out and effective program to help them catch up, they will never catch up. They may actually drop out of school. The immediate consequences of learning loss and disengagement are going to be a generation of people who will be less educated.”

There is hope, however. Just as the lockdown forced teachers to improvise, accelerating forms of online learning, so too may the recovery offer options for educational reform.

The solutions, say Reville, “are going to come from our community. This is a civic problem.” He applauded one example, the Somerville, Mass., public library program of outdoor Wi-Fi “pop ups,” which allow 24/7 access either through their own or library Chromebooks. “That’s the kind of imagination we need,” he said.

On a national level, he points to the creation of so-called “Children’s Cabinets.” Already in place in 30 states, these nonpartisan groups bring together leaders at the city, town, and state levels to address children’s needs through schools, libraries, and health centers. A July 2019 “ Children’s Cabinet Toolkit ” on the Education Redesign Lab site offers guidance for communities looking to form their own, with sample mission statements from Denver, Minneapolis, and Fairfax, Va.

Already the Education Redesign Lab is working on even more wide-reaching approaches. In Tennessee, for example, the Metro Nashville Public Schools has launched an innovative program, designed to provide each student with a personalized education plan. By pairing these students with school “navigators” — including teachers, librarians, and instructional coaches — the program aims to address each student’s particular needs.

“This is a chance to change the system,” said Reville. “By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now.”

“Students have different needs,” agreed Long. “We just have to get a better understanding of what we need to prioritize and where students are” in all aspects of their home and school lives.

“By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now,” says Paul Reville of the GSE.

Already, educators are discussing possible responses. Long and GSE helped create The Principals’ Network as one forum for sharing ideas, for example. With about 1,000 members, and multiple subgroups to address shared community issues, some viable answers have begun to emerge.

“We are going to need to expand learning time,” said Long. Some school systems, notably Texas’, already have begun discussing extending the school year, she said. In addition, Long, an internationally recognized economist who is a member of the National Academy of Education and the MDRC board, noted that educators are exploring innovative ways to utilize new tools like Zoom, even when classrooms reopen.

“This is an area where technology can help supplement what students are learning, giving them extra time — learning time, even tutoring time,” Long said.

Reimers, who serves on the UNESCO Commission on the Future of Education, has been brainstorming solutions that can be applied both here and abroad. These include urging wealthier countries to forgive loans, so that poorer countries do not have to cut back on basics such as education, and urging all countries to keep education a priority. The commission and its members are also helping to identify good practices and share them — globally.

Innovative uses of existing technology can also reach beyond traditional schooling. Reimers cites the work of a few former students who, working with Harvard Global Education Innovation Initiative, HundrED , the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills , and the World Bank Group Education Global Practice, focused on podcasts to reach poor students in Colombia.

They began airing their math and Spanish lessons via the WhatsApp app, which was widely accessible. “They were so humorous that within a week, everyone was listening,” said Reimers. Soon, radio stations and other platforms began airing the 10-minute lessons, reaching not only children who were not in school, but also their adult relatives.

Share this article

You might like.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Six receive honorary degrees

Harvard recognizes educator, conductor, theoretical physicist, advocate for elderly, writer, and Nobel laureate

Everything counts!

New study finds step-count and time are equally valid in reducing health risks

Bridging social distance, embracing uncertainty, fighting for equity

Student Commencement speeches to tap into themes faced by Class of 2024

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

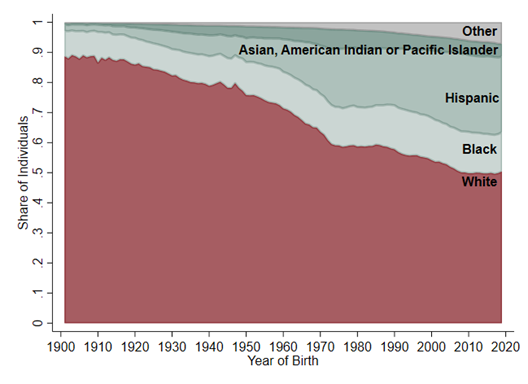

The U.S. student population is more diverse, but schools are still highly segregated

Sequoia Carrillo

Pooja Salhotra

The U.S. student body is more diverse than ever before. Nevertheless, public schools remain highly segregated along racial, ethnic and socioeconomic lines.

That's according to a report released Thursday by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). More than a third of students (about 18.5 million of them) attended a predominantly same-race/ethnicity school during the 2020-21 school year, the report finds. And 14% of students attended schools where almost all of the student body was of a single race/ethnicity.

The report is a follow up to a 2016 GAO investigation on racial disparity in K-12 schools. That initial report painted a slightly worse picture, but findings from the new report are still concerning, says Jackie Nowicki, the director of K-12 education at the GAO and lead author of the report.

Why White School Districts Have So Much More Money

"There is clearly still racial division in schools," says Nowicki. She adds that schools with large proportions of Hispanic, Black and American Indian/Alaska Native students – minority groups with higher rates of poverty than white and Asian American students – are also increasing. "What that means is you have large portions of minority children not only attending essentially segregated schools, but schools that have less resources available to them."

"There are layers of factors here," she says. "They paint a rather dire picture of the state of schooling for a segment of the school-age population that federal laws were designed to protect."

School segregation happens across the country

Segregation has historically been associated with the Jim Crow laws of the South. But the report finds that, in the 2020-21 school year, the highest percentage of schools serving a predominantly single-race/ethnicity student population – whether mostly white, mostly Hispanic or mostly Black etc. – were in the Northeast and the Midwest.

School segregation has "always been a whole-country issue," says U.S. Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Va., who heads the House education and labor committee. He commissioned both the 2016 and 2022 reports. "The details of the strategies may be different, but during the '60s and '70s, when the desegregation cases were at their height, cases were all over the country."

How The Systemic Segregation Of Schools Is Maintained By 'Individual Choices'

The GAO analysis also found school segregation across all school types, including traditional public schools, charter schools and magnet schools. Across all charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately run, more than a third were predominantly same-race/ethnicity, serving mostly Black and Hispanic students.

There's history behind the report's findings

Nowicki and her team at the GAO say they were not surprised by any of the report's findings. They point to historical practices, like redlining , that created racially segregated neighborhoods.

And because 70% of U.S. students attend their neighborhood public schools, Nowicki says, racially segregated neighborhoods have historically made for racially segregated schools.

The 50 Most Segregating School Borders In America

"There are historical reasons why neighborhoods look the way they look," she explains. "And some portion of that is because of the way our country chose to encourage or limit where people could live."

Though the 1968 Fair Housing Act outlawed housing discrimination on the basis of race, the GAO says that in some states, current legislation reinforces racially isolated communities.

"Our analysis showed that predominantly same-race/ethnicity schools of different races/ethnicities exist in close proximity to one another within districts, but most commonly exist among neighboring districts," the report says.

School district secessions have made segregation worse

One cause for the lack of significant improvement, according to the GAO, is a practice known as district secession, where schools break away from an existing district – often citing a need for more local control – and form their own new district. The result, the report finds, is that segregation deepens.

"In the 10 years that we looked at district secessions, we found that, overwhelmingly, those new districts were generally whiter, wealthier than the remaining districts," Nowicki says.

Six of the 36 district secessions identified in the report happened in Memphis, Tenn., which experienced a historic district merger several years ago. Memphis City Schools, which served a majority non-white student body, dissolved in 2011 due to financial instability. It then merged with the neighboring district, Shelby County Schools, which served a wealthier, majority white population.

This Supreme Court Case Made School District Lines A Tool For Segregation

Joris Ray was a Memphis City Schools administrator at the time of the merger. He recalls that residents of Shelby County were not satisfied with the new consolidated district. They successfully splintered off into six separate districts.

As a result, the GAO report says, racial and socioeconomic segregation has grown in and around Memphis. All of the newly formed districts are whiter and wealthier than the one they left, which is now called Memphis-Shelby County Schools.

Why Busing Didn't End School Segregation

"This brings negative implications for our students overall," says Ray, who has led Memphis-Shelby County Schools since 2019. "Research has shown that students in more diverse schools have lower levels of prejudice and stereotypes and are more prepared for top employers to hire an increasingly diverse workforce."

The GAO report finds that this pattern – of municipalities removing themselves from a larger district to form their own, smaller school district – almost always creates more racial and socioeconomic segregation. Overall, new districts tend to have larger shares of white and Asian American students, and lower shares of Black and Hispanic students, the report finds. New districts also have significantly fewer students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, a common measure of poverty.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Still Separate, Still Unequal: Teaching about School Segregation and Educational Inequality

By Keith Meatto

- May 2, 2019

Racial segregation in public education has been illegal for 65 years in the United States. Yet American public schools remain largely separate and unequal — with profound consequences for students, especially students of color.

Today’s teachers and students should know that the Supreme Court declared racial segregation in schools to be unconstitutional in the landmark 1954 ruling Brown v. Board of Education . Perhaps less well known is the extent to which American schools are still segregated. According to a recent Times article , “More than half of the nation’s schoolchildren are in racially concentrated districts, where over 75 percent of students are either white or nonwhite.” In addition, school districts are often segregated by income. The nexus of racial and economic segregation has intensified educational gaps between rich and poor students, and between white students and students of color.

Although many students learn about the historical struggles to desegregate schools in the civil rights era, segregation as a current reality is largely absent from the curriculum.

“No one is really talking about school segregation anymore,” Elise C. Boddie and Dennis D. Parker wrote in this 2018 Op-Ed essay. “That’s a shame because an abundance of research shows that integration is still one of the most effective tools that we have for achieving racial equity.”

The teaching activities below, written directly to students, use recent Times articles as a way to grapple with segregation and educational inequality in the present. This resource considers three essential questions:

• How and why are schools still segregated in 2019? • What repercussions do segregated schools have for students and society? • What are potential remedies to address school segregation?

School segregation and educational inequity may be a sensitive and uncomfortable topic for students and teachers, regardless of their race, ethnicity or economic status. Nevertheless, the topics below offer entry points to an essential conversation, one that affects every American student and raises questions about core American ideals of equality and fairness.

Six Activities for Students to Investigate School Segregation and Educational Inequality

Activity #1: Warm-Up: Visualize segregation and inequality in education.

Based on civil rights data released by the United States Department of Education, the nonprofit news organization ProPublica has built an interactive database to examine racial disparities in educational opportunities and school discipline. In this activity, which might begin a deeper study of school segregation, you can look up your own school district, or individual public or charter school, to see how it compares with its counterparts.

To get started: Scroll down to the interactive map of the United States in this ProPublica database and then answer the following questions:

1. Click the tabs “Opportunity,” “Discipline,” “Segregation” and “Achievement Gap” and answer these two simple questions: What do you notice? What do you wonder? (These are the same questions we ask as part of our “ What’s Going On in This Graph? ” weekly discussions.) 2. Next, click the tabs “Black” and “Hispanic.” What do you notice? What do you wonder? 3. Search for your school or district in the database. What do you notice in the results? What questions do you have?

For Further Exploration

Research your own school district. Then write an essay, create an oral presentation or make an annotated map on segregation and educational inequity in your community, using data from the Miseducation database.

Activity #2: Explore a case study: schools in Charlottesville, Va.

The New York Times and ProPublica investigated how segregation still plays a role in shaping students’ educational experiences in the small Virginia city of Charlottesville. The article begins:

Zyahna Bryant and Trinity Hughes, high school seniors, have been friends since they were 6, raised by blue-collar families in this affluent college town. They played on the same T-ball and softball teams, and were in the same church group. But like many African-American children in Charlottesville, Trinity lived on the south side of town and went to a predominantly black neighborhood elementary school. Zyahna lived across the train tracks, on the north side, and was zoned to a mostly white school, near the University of Virginia campus, that boasts the city’s highest reading scores.

Before you read the rest of the article, and learn about the experiences of Zyahna and Trinity, answer the following questions based on your own knowledge, experience and opinions:

• What is the purpose of public education? • Do all children in America receive the same quality of education? • Is receiving a quality public education a right (for everyone) or a privilege (for some)? • Is there a correlation between students’ race and the quality of education they receive?

Now read the entire article about lingering segregation in Charlottesville and answer the following questions:

1. How is Charlottesville’s school district geographically and racially segregated? 2. How is Charlottesville a microcosm of education in America? 3. How do white and black students in Charlottesville compare in terms of participation in gifted and talented programs; being held back a grade; being suspended from school? 4. How do black and white students in Charlottesville compare in terms of reading at grade level? 5. How do Charlottesville school officials explain the disparities between white and black students? 6. Why are achievement disparities so common in college towns? 7. In what ways do socioeconomics not fully explain the gap between white and black students?

After reading the article and answering the above questions, share your reactions using the following prompts:

• Did anything in the article surprise you? Shock you? Make you angry or sad? Why? • On the other hand, did anything in the article strike you as unsurprising? Explain. • How might education in Charlottesville be made more equitable?

Choose one or more of the following ideas to investigate school segregation in the United States and around the world.

1. Read and discuss “ In a Divided Bosnia, Segregated Schools Persist .” Compare and contrast the situations in Bosnia and Charlottesville. How does this perspective confirm, challenge, or complicate your understanding of the topic?

2. Read and discuss the article and study the map and graphs in “ Why Are New York’s Schools Segregated? It’s Not as Simple as Housing .” How does “school choice” confirm, challenge or complicate your understanding of segregation and educational inequity?

3. Only a tiny number of black students were offered admission to the highly selective public high schools in New York City in 2019, raising the pressure on officials to confront the decades-old challenge of integrating New York’s elite public schools. To learn more about this story, listen to this episode of The Daily . For more information, read these Op-Ed essays and editorials offering different perspectives on the problem and possible solutions. Then, make a case for what should be done — or not done — to make New York’s elite public schools more diverse.

• Stop Fixating on One Elite High School, Stuyvesant. There Are Bigger Problems. • How Elite Schools Stay So White • No Ethnic Group Owns Stuyvesant. All New Yorkers Do. • De Blasio’s Plan for NYC Schools Isn’t Anti-Asian. It’s Anti-Racist. • New York’s Best Schools Need to Do Better

3. Read and discuss “ The Resegregation of Jefferson County .” How does this story confirm, challenge or complicate your understanding of the topic?

Activity #3: Investigate the relationship between school segregation, funding and inequality.

Some school districts have more money to spend on education than others. Does this funding inequality have anything to do with lingering segregation in public schools? A recent report says yes. A New York Times article published in February begins:

School districts that predominantly serve students of color received $23 billion less in funding than mostly white school districts in the United States in 2016, despite serving the same number of students, a new report found. The report, released this week by the nonprofit EdBuild, put a dollar amount on the problem of school segregation, which has persisted long after Brown v. Board of Education and was targeted in recent lawsuits in states from New Jersey to Minnesota. The estimate also came as teachers across the country have protested and gone on strike to demand more funding for public schools.

Answer the following questions based on your own knowledge, experience and opinions.

• Who pays for public schools? • Is there a correlation between money and education? Does the amount of money a school spends on students influence the quality of the education students receive?

Now read the rest of the Times article about funding differences between mostly white school districts and mostly nonwhite ones, and then answer the following questions:

1. How much less total funding do school districts that serve predominantly students of color receive compared to school districts that serve predominantly white students? 2. Why are school district borders problematic? 3. How many of the nation’s schoolchildren are in “racially concentrated districts, where over 75 percent of students are either white or nonwhite”? 4. How much less money, on average, do nonwhite districts receive than white districts? 5. How are school districts funded? 6. How does lack of school funding affect classrooms? 7. What is the new kind of ”white flight” in Arizona and why is it a problem? 8. What is an “enclave”? What does the statement “some school districts have become their own enclaves” mean?

• Did anything in the article surprise you? Shock you? Make you angry or sad? Why? • On the other hand, did anything in the article strike you as unsurprising? Explain. • How could school funding be made more equitable?

Choose one or more of the following ideas to investigate the interrelationship among school segregation, funding and inequality.

1. Research your local school district budget, using public records or local media, such as newspapers or television reporting. What is the budget per student? How does that budget compare with the state average? The national average? 2. Compare your findings about your local school budget to your research about segregation and student outcomes, using the Miseducation database. Do the results of your research suggest any correlations?

Activity #4: Examine potential legal remedies to school segregation and educational inequality.

How do we get better schools for all children? One way might be to take the state to court. A Times article from August reports on a wave of lawsuits that argue that states are violating their constitutions by denying children a quality education. The article begins:

By his own account, Alejandro Cruz-Guzman’s five children have received a good education at public schools in St. Paul. His two oldest daughters are starting careers in finance and teaching. Another daughter, a high-school student, plans to become a doctor. But their success, Mr. Cruz-Guzman said, flows partly from the fact that he and his wife fought for their children to attend racially integrated schools outside their neighborhood. Their two youngest children take a bus 30 minutes each way to Murray Middle School, where the student population is about one-third white, one-third black, 16 percent Asian and 9 percent Latino. “I wanted to have my kids exposed to different cultures and learn from different people,” said Mr. Cruz-Guzman, who owns a small flooring company and is an immigrant from Mexico. When his two oldest children briefly attended a charter school that was close to 100 percent Latino, he said he had realized, “We are limiting our kids to one community.” Now Mr. Cruz-Guzman is the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit saying that Minnesota knowingly allowed towns and cities to set policies and zoning boundaries that led to segregated schools, lowering test scores and graduation rates for low-income and nonwhite children.

Read the entire article and then answer the following questions:

1. What does Mr. Cruz-Guzman’s suit allege against the State of Minnesota? 2. Why are advocates for school funding equity focused on state government, as opposed to the federal government? 3. What did a state judge rule in New Mexico? What did the Kansas Supreme Court rule? 4. What fraction of fourth and eighth graders in New Mexico is not proficient in reading? What does research suggest may improve their test scores? 5. According to a 2016 study, if a school spends 10 percent more per pupil, what percentage more would students earn as adults? 6. What does the economist Eric Hanushek argue about the correlation between spending and student achievement? 7. What remedy for school segregation is Daniel Shulman, the lead lawyer in the Minnesota desegregation suit, considering? Why are charter schools nervous about the case? 8. How does Khulia Pringle see some charter schools as “culturally affirming”? What problems does Ms. Pringle see with busing white children to black schools and vice versa?

• Did anything in the article surprise you? What other emotional responses did you have while reading? Why? • On the other hand, did anything in the article strike you as unsurprising? Explain. • Do the potential “cultural” benefits of school segregation outweigh the costs?

Choose one or more of the following ideas to investigate potential remedies to school segregation and educational inequality.

1. Read the obituaries “ Jean Fairfax, Unsung but Undeterred in Integrating Schools, Dies at 98 ” and “ Linda Brown, Symbol of Landmark Desegregation Case, Dies at 75 .” How do their lives inform your grasp of legal challenges to segregation?

2. Watch the following video about school busing . How does this history inform your understanding of the benefits and challenges of busing?

3. Read about how parents in two New York City school districts are trying to tackle segregation in local middle schools . Then decide if these models have potential for other districts in New York or around the country. Why or why not?

Activity #5: Consider alternatives to integration.

Is integration the best and only choice for families who feel their children are being denied a quality education? A recent Times article reports on how some black families in New York City are choosing an alternative to integration. The article begins:

“I love myself!” the group of mostly black children shouted in unison. “I love my hair, I love my skin!” When it was time to settle down, their teacher raised her fist in a black power salute. The students did the same, and the room hushed. As children filed out of the cramped school auditorium on their way to class, they walked by posters of Colin Kaepernick and Harriet Tubman. It was a typical morning at Ember Charter School in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, an Afrocentric school that sits in a squat building on a quiet block in a neighborhood long known as a center of black political power. Though New York City has tried to desegregate its schools in fits and starts since the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, the school system is now one of the most segregated in the nation. But rather than pushing for integration, some black parents in Bedford-Stuyvesant are choosing an alternative: schools explicitly designed for black children.

Before you read the rest of the article, answer the following questions based on your own knowledge, experience and opinions:

• Should voluntary segregation in schools be permissible? Why or why not? • What potential benefits might voluntary segregation offer? • What potential problems might it pose?

Now, read the entire article and then answer these questions:

1. What is the goal of Afrocentric schools? 2. Why are some parents and educators enthusiastic about Afrocentric schools? 3. Why are some experts wary of Afrocentric schools? 4. What does Alisa Nutakor want to offer minority students at Ember? 5. What position does the city’s schools chancellor take on Afrocentric schools? 6. What “modest desegregation plans” have some districts offered? With what result? 7. Why did Fela Barclift found Little Sun People? 8. Why are some parents ambivalent about school integration? According to them, how can schools be more responsive to students of color? 9. What does Mutale Nkonde mean by the phrase “not all boats are rising”? 10. What did Jordan Pierre gain from his experience at Eagle Academy?

• Did anything in the article surprise you? What other emotional responses did you have while reading? Why? • On the other hand, did anything in the article strike you as unsurprising? Explain. • Did the article challenge your opinion about voluntary segregation? How?

Choose one or more of the following ideas to investigate some of the complicating factors that influence where parents decide to send their children to school.

1. Read and discuss “ Choosing a School for My Daughter in a Segregated City .” How does reading about segregation, inequity and school choice from a parent’s perspective confirm, challenge or complicate your understanding of the topic?

2. Read “ Do Students Get a Subpar Education in Yeshivas? ” How might a student’s religious affiliation complicate the issue of segregation and inequity in education?

Activity #6: Learn more and take action.

Segregation still persists in public schools more than 60 years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision. What more can you learn about the issue? What choices can you make? Is there anything students can do about the issue?

Write a personal essay about your experience with school segregation. For inspiration, read Erin Aubrey Kaplan’s op-ed essay, “ School Choice Is the Enemy of Justice ,” which links a contemporary debate with the author’s personal experience of school segregation.

Interview a parent, grandparent or another adult about their educational experiences related to segregation, integration and inequity in education. Compare their experiences with your own. Share your findings in a paper, presentation or class discussion.

Take action by writing a letter about segregation and educational inequity in your community. Send the letter to a person or organization with local influence, such as the school board, an elected official or your local newspaper.

Discuss the issue in your school or district by raising the topic with your student council, parent association or school board. Be prepared with information you discovered in your research and bring relevant questions.

Additional Resources

Choices in Little Rock | Facing History and Ourselves

Beyond Brown: Pursuing the Promise | PBS

Why Are American Public Schools Still So Segregated? | KQED

Toolkit for “Segregation by Design” | Teaching Tolerance

Exploring Equity: Race and Ethnicity

- Posted February 18, 2021

- By Gianna Cacciatore

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Inequality and Education Gaps

- Moral, Civic, and Ethical Education

- Teachers and Teaching

The history of education in the United States is rife with instances of violence and oppression along lines of race and ethnicity. For educators, leading conversations about race and racism is a challenging, but necessary, part of their work.

“Schools operate within larger contexts: systems of race, racism, and white supremacy; systems of migration and ethnic identity formation; patterns of socialization; the changing realities of capitalism and politics,” explains historian and Harvard lecturer Timothy Patrick McCarthy , co-faculty lead of Race and Ethnicity in Context, a new module offered at the Harvard Graduate School of Education this January as part of a pilot of HGSE’s Equity and Opportunity Foundations course. “How do we understand the role that racial and ethnic identity play with respect to equity and opportunity within an educational context?”

>> Learn more about Equity and Opportunity and HGSE’s other foundational learning experiences.

For educators exploring question in their own homes, schools, and communities, McCarthy and co-faculty lead Ashley Ison, an HGSE doctoral student, offer five ways to get started.

1. Begin with the self.

Practitioners enter conversations about race and racism from different backgrounds, with different lived experiences, personal and professional perspectives, and funds of knowledge in their grasps. Given diverse contexts and realities, it is important that leaders encourage personal transformation and growth. Educators should consider how race and racism, as well as racial and ethnic identity formation, impact their lives as educational professionals, as parents, and as policymakers – whatever roles they hold in society. “This is personal work, but that personal work is also political work,” says Ison.

2. Model vulnerability.

Entering into discussions of race and racism can be challenging, even for those with experience in this work. A key part of enabling participants to lean into the challenge is being vulnerable. “You have trust your students,” explains McCarthy. “Part of that is modeling authentic vulnerability and proximity to the work.” This can be done by modeling discussion skills, like sharing the space and engaging directly with the comments of other participants, as well as by opening up personally to participants.

“Fear can impact how people feel talking about race and ethnicity in an inter-group space,” says Ison. Courage, openness, and trust are key to overcoming that fear and enabling listening, which ultimately allows for critical thinking and change.

3. Be transparent.

Part of being vulnerable is being fully transparent with your students from day one. “Intentions are important,” explains McCarthy. “The gap between intention and impact is often rooted in a lack of transparency about where you’re coming from or where you are hoping to go.”

4. Center voices of color.

Voice and story are powerful tools in this work. Leaders must consider whose voices and stories take precedence on the syllabus. “Consider highlighting authors of color, in particular, who are thinking and writing about these issues,” says Ison. Becoming familiar with a variety of perspectives can help practitioners understand the voices and ideas that exist, she explains.

“Voice and storytelling can bear witness to the various kinds of systematic injustices and inequities we are looking at, but they also function as sources of power for imagining and reimagining the world we are trying to build, all while providing a deeper knowledge of the world as it has existed historically,” adds McCarthy.

5. Prioritize discussion and reflection.

Since this work is as much about critical thinking as it is about content, it is important for educators to make space for discussion and reflection, at the whole-class, small-group, and individual levels. Ison and McCarthy encourage educators to allow students to generate and guide the discussion of predetermined course materials. They also recommend facilitating small group reflections that may spark conversation that can extend into other spaces outside of the classroom.

Selected Resources:

- Poor, but Privileged

- NPR: "The Importance of Diversity in Teaching Staff”

- TED Talk with Clint Smith: "The Danger of Silence"

More Stories from the Series:

- Exploring Equity: Citizenship and Nationality

- Exploring Equity: Gender and Sexuality

- Exploring Equity: Dis/ability

- Exploring Equity: Class

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Navigating Tensions Over Teaching Race and Racism

Disrupting Whiteness in the Classroom

Combatting Anti-Asian Racism

Equipping educators with restorative justice techniques to upend discrimination and stereotype

Racial and ethnic equity in US higher education

Higher education in the United States (not-for-profit two-year and four-year colleges and universities) serves a diversifying society. By 2036, more than 50 percent of US high school graduates will be people of color, 1 Peace Bransberger and Colleen Falkenstern, Knocking at the college door: Projections of high school graduates through 2037 – Executive summary , Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE), December 2020. and McKinsey analysis shows that highly research-intensive (R1) institutions (131 as of 2020 2 Institutions with very high research activity as assessed by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. ) have publicly shared plans or aspirations regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Ninety-five percent of R1 institutions also have a senior DEI executive, and diversity leaders in the sector have formed their own consortiums to share expertise. 3 Two examples are the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education and the Liberal Arts Diversity Consortium.

Despite ongoing efforts, our analysis suggests that historically marginalized racial and ethnic populations—Black, Hispanic and Latino, and Native American and Pacific Islander—are still underrepresented in higher education among undergraduates and faculty and in leadership. Students from these groups also have worse academic outcomes as measured by graduation rates. Only 8 percent of institutions have at least equitable student representation while also helping students from underrepresented populations graduate at the same rate as the general US undergraduate population. 4 For a closer look at the data behind the racial and ethnic representation among students and faculty in higher education, see Diana Ellsworth, Erin Harding, Jonathan Law, and Duwain Pinder, “ Racial and ethnic equity in US higher education: Students and faculty ,” McKinsey, July 14, 2022. Not included in this discussion are Asian Americans, who face a distinct set of challenges in higher education. These issues deserve a separate discussion.

These finding are not novel, but what is significant is the slow rate of progress. Current rates of change suggest that it would take about 70 years for all not-for-profit institutions to reflect underrepresented students fully in their incoming student population, primarily driven by recent increases in Hispanic and Latino student attendance. For Black and Native American students and for faculty from all underrepresented populations, there was effectively no progress from 2013 to 2020. 5 For a closer look at college completion rates, see Diana Ellsworth, Erin Harding, Jonathan Law, and Duwain Pinder, “ Racial and ethnic equity in US higher education: Completion rates ,” McKinsey, July 14, 2022.

Intensified calls for racial and ethnic equity in every part of society have made the issue particularly salient. In this article, we outline some of the key insights from our report on racial and ethnic equity in higher education in the United States. We report our analysis of racial and ethnic representation in student and faculty bodies and of outcomes for underrepresented populations. Then we discuss how institutions can meet goals around racial and ethnic equity.

A mirror of wider systemic inequities

Colleges and universities are places of teaching and learning, research and creative expression, and impact on surrounding communities. As the data and analysis in this report illustrate, these institutions have been reflections of existing racial and socioeconomic inequities across society.

These hierarchies include chronic disparities in outcomes throughout the education system. Consider that students from underrepresented populations still graduate from high school at lower rates compared to White and Asian students and tend to be less prepared for college. 6 “Public high school graduation rates,” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), US Department of Education, May 2021; “Secondary school completion: College and career readiness benchmarks,” American Council on Education (ACE), 2020; “Secondary school completion: Participation in advanced placement,” ACE, 2020. Evidence suggests that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are exacerbating these high school inequities, 7 For more, see Emma Dorn, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg, “ COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning ,” McKinsey, July 27, 2021. which heavily influence the makeup of higher education’s student population. Forty-one percent of all 18- to 21-year-olds were enrolled in undergraduate studies in 2018 compared to 37 percent of Black students, 36 percent of Hispanic students, and 24 percent of American Indian students. 8 “College enrollment rates,” NCES, US Department of Education, May 2022.

Our analysis suggests that higher education has opportunities to address many of these gaps. However, our analysis of student representation over time also suggests that progress has been uneven. In 2013, 38 percent of all not-for-profit institutions had a more diverse population than would be expected given the racial and ethnic makeup of the traditional college-going population—that is, 18- to 24-year-olds, our proxy for equitable racial representation—within a given home state. By 2020, that number was 44 percent. At this rate, the student bodies of not-for-profit institutions overall will reach representational parity in about 70 years, but that growth would be driven entirely by increases in the share of Hispanic and Latino students.

Many institutions have indicated that in addition to increasing student-body diversity, they also seek to improve graduation rates for students from underrepresented populations. A positive finding from our analysis is that nearly two-thirds of all students attend not-for-profit institutions with higher-than-average graduation rates for students from underrepresented populations. However, when we overlay institution representativeness with graduation rates, only 8 percent of students attend four-year institutions that have student bodies that reflect their students’ home states’ traditional college population and that help students from underrepresented populations graduate within six years at an above-average rate (Exhibit 1). 9 For institution-specific completion data, see Diana Ellsworth, Erin Harding, Jonathan Law, and Duwain Pinder, “ Racial and ethnic equity in US higher education: Completion rates ,” McKinsey, July 14, 2022.

In addition, our analysis shows that from 2013 to 2020, only one-third of four-year institutions had improved both racial and ethnic representation and completion rates for students from underrepresented populations at a higher rate than underrepresented populations’ natural growth rate in that period (2 percent). If we look at improvements in racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic representation among students, only 7 percent of four-year institutions have progressed.

Among faculty, complex reasons including the changing structure of academia and patterns of racial inequity in society mean that faculty members from underrepresented populations are less likely to be represented and to ascend the ranks than their White counterparts. 10 Colleen Flaherty, “The souls of Black professors,” Inside Higher Ed, October 21, 2020; Fernanda Zamudio-Suarez, “Race on campus: Anti-CRT laws take aim at colleges,” email, The Chronicle of Higher Education , April 26, 2022; Mike Lauer, “Trends in diversity within the NIH-funded workforce,” National Institutes of Health (NIH), August 7, 2018. Additionally, representational disparity among faculty is more acute in R1 institutions. When we analyzed the full-time faculty population relative to the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher (given that most faculty positions require at least a bachelor’s degree), in 2020, approximately 75 percent of not-for-profit institutions were less diverse than the broader bachelor’s degree–attaining population, and 95 percent of institutions defined as R1 were less diverse. Additionally, the pace of change is slow: it would take nearly 300 years to reach parity for all not-for-profit institutions at the current pace and 450 years for R1 institutions.

Higher education’s collective aspirations for parity of faculty diversity could arguably be even greater. Faculty diversity could be compared to the total population (rather than just the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher) for several reasons. First, comparing faculty diversity to bachelor’s degree recipients incorporates existing inequities in higher-education access and completion across races and ethnicities (which have been highlighted above). Second, the impact of faculty (especially from the curriculum they create and teach, as well as the research, scholarship, and creative expression they produce) often has repercussions across the total US population.

Therefore, in this research, we compared faculty diversity to the total population. Our analysis shows that 88 percent of not-for-profit colleges and universities have full-time faculties that are less diverse than the US population as of 2020. That number rises to 99 percent for institutions defined as R1. Progress in diversifying full-time faculty ranks to match the total population over the past decade has been negligible; it would take more than 1,000 years at the current pace to reach parity for all not-for-profit institutions. (R1 institutions will never reach parity at current rates.) When looking at both faculty and students, few institutions are racially representative of the country; only 11 percent of not-for-profit institutions and 1 percent of R1 institutions are (Exhibit 2).