Proof and Problem Solving

This is a homepage for mat299, proof and problem solving, with dr. gilbert at southern new hampshire university. this course introduces students to the practice of proof-writing in the context of integers and basic operations, divisibility, sets, relations, and functions. the focus of the course is on constructing and defending proofs. students will also learn mathematical typesetting and latex syntax using google colab and mathjax., mat 299 - mathematical proof and problem solving.

Course Timeline and Notebooks

Below is a tentative timeline for our course. It includes preparatory work that should be done prior to each class meeting, a detailed set of notes corresponding to each class meeting, and assignments following each class meeting.

| Class Meeting | Before Class | During Class | After Class |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Review Syllabus | Introduction and What to Expect | HW 1: Intro to Colab and LaTeX |

| 2 | HW 2 | ||

| 3 | |||

| 4 | |||

| 5 | HW 3 | ||

| 6 | |||

| 7 | HW 4 | ||

| 8 | |||

| 9 | Catch-Up Day | ||

| 10 | HW 5 | ||

| 11 | |||

| 12 | HW 6 | ||

| 13 | |||

| 14 | HW 7 | ||

| 15 | |||

| 16 | |||

| 17 | Exam I, Part I | ||

| 18 | Exam I, Part II | ||

| 19 | HW 8 | ||

| 20 | |||

| 21 | HW 9 | ||

| 22 | |||

| 23 | HW 10 | ||

| 24 | |||

| 25 | |||

| 26 | Exam II, Part I | ||

| 27 | Exam II, Part II | ||

| 28+ | Oral Proof Defenses |

Back to Hompage

- Help & FAQ

Problem-solving, proving, and learning: The relationship between problem-solving processes and learning opportunities in the activity of proof construction

- Graduate School of Education, Learning & Teaching

Rutgers, The State University

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

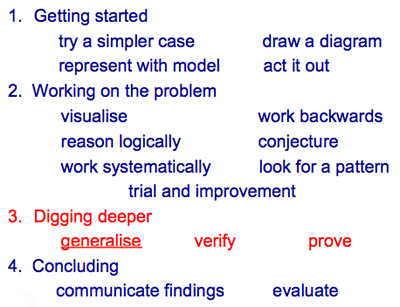

In university mathematics courses, the activity of proof construction can be viewed as a problem-solving task in which the prover is asked to form a logical justification demonstrating that a given statement must be true. The purposes of this paper are to describe some of the different types of reasoning and problem-solving processes used by undergraduates to construct proofs in their university mathematics courses, and to consider the relationship between the reasoning that students use when constructing a proof and what they have the opportunity to learn from their proving experience.

| Original language | American English |

|---|---|

| Pages (from-to) | 351-360 |

| Number of pages | 10 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 24 |

| Issue number | 3-4 |

| DOIs | |

| State | Published - 2005 |

ASJC Scopus subject areas

- Applied Psychology

- Applied Mathematics

- Problem solving

- Problem-solving processes

Access to Document

- 10.1016/j.jmathb.2005.09.005

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Mathematics Medicine & Life Sciences 100%

- Learning Mathematics 70%

- Universities Mathematics 62%

- mathematics Social Sciences 52%

- Reasoning Mathematics 48%

- Relationships Mathematics 46%

- university Social Sciences 35%

- Students Engineering & Materials Science 28%

T1 - Problem-solving, proving, and learning

T2 - The relationship between problem-solving processes and learning opportunities in the activity of proof construction

AU - Weber, Keith

N2 - In university mathematics courses, the activity of proof construction can be viewed as a problem-solving task in which the prover is asked to form a logical justification demonstrating that a given statement must be true. The purposes of this paper are to describe some of the different types of reasoning and problem-solving processes used by undergraduates to construct proofs in their university mathematics courses, and to consider the relationship between the reasoning that students use when constructing a proof and what they have the opportunity to learn from their proving experience.

AB - In university mathematics courses, the activity of proof construction can be viewed as a problem-solving task in which the prover is asked to form a logical justification demonstrating that a given statement must be true. The purposes of this paper are to describe some of the different types of reasoning and problem-solving processes used by undergraduates to construct proofs in their university mathematics courses, and to consider the relationship between the reasoning that students use when constructing a proof and what they have the opportunity to learn from their proving experience.

KW - Learning

KW - Problem solving

KW - Problem-solving processes

KW - Reasoning

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=29444445929&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=29444445929&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1016/j.jmathb.2005.09.005

DO - 10.1016/j.jmathb.2005.09.005

M3 - Article

SN - 0732-3123

JO - Journal of Mathematical Behavior

JF - Journal of Mathematical Behavior

Undergraduate Students’ Understanding of Proof: Relationships Between Proof Conceptions, Beliefs, and Classroom Experiences with Learning Proof

- Published: 19 May 2015

- Volume 1 , pages 91–134, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- Despina A. Stylianou 1 ,

- Maria L. Blanton 2 &

- Ourania Rotou 3

6104 Accesses

24 Citations

Explore all metrics

This article presents the results from a study of 535 early undergraduate students at six universities that was designed to describe their views of the meaning of proof and how these views relate to their attitudes and beliefs towards proof and their classroom experiences with learning proof. Results show that early undergraduate students have difficulty with mathematical proof. In particular, the study showed that students’ proof choices were strongly influenced by surface characteristics of the tasks. However, a large number of students appear to appreciate and acknowledge the rigor and central role of deductive proof in mathematics despite the difficulties they may face in producing proofs. Further, the study showed a strong positive relationship between students’ beliefs about the role of proof and themselves as learners of proof, but weak relationship between proof ability and self-reported experiences with learning proof.

Similar content being viewed by others

About the Teaching and Learning of Proof and Proving: Cognitive Issues, Curricular Issues and Beyond

Perceptions on proof and the teaching of proof: a comparison across preservice secondary teachers in Australia, USA and Korea

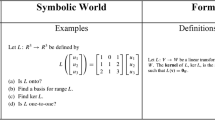

Student perspectives on proof in linear algebra

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Arguments that the “essence of mathematics lies in proofs” (Ross 1998 , p. 2) and that “proof is not a thing separable from mathematics…. [but] is an essential component of doing, communicating, and recording mathematics” (Schoenfeld 1994 , p. 76) reinforce the centrality of proof in mathematical thinking. Moreover, not only does the act of proof “distinguish mathematical behavior from scientific behavior in other disciplines” (Dreyfus 1990 , p. 126), it also serves as a tool for learning mathematics (Hanna 1990 , 1995 ; Hersh 1993 ). As such, mathematicians and mathematics educators have called for the learning of proof to become a central goal of mathematics learning and instruction (NCTM 2000 ; RAND Mathematics Study Panel 2003 ). The Committee on the Undergraduate Program in Mathematics, appointed by the Mathematical Association of America (MAA) to identify major issues and develop tentative recommendations for an undergraduate mathematics Curriculum Guide (MAA 2000 ), has emphasized this goal and has recommended that proof should be a part of students’ mathematical experiences—especially of those students in mathematics-related programs. The report states that “students should understand and appreciate the core of mathematical culture: the value and validity of careful reasoning, precise definition and close argument” (p. 6).

Yet, research in mathematics education indicates that most students, in particular at the secondary school level, face substantial difficulties with proof (see Harel and Sowder 2007 ; Stylianou et al. 2009 for reviews). There also is evidence that college students face similar difficulties with proof as their high school counterparts. Most notably, Harel and Sowder ( 1998 ) showed that college students focus their attention on the format of the proof rather than the content. However, we know little about the conceptions of students as they are beginning to immerse themselves in college mathematics. Perhaps more importantly, we have not yet explored the relationship between students’ understanding of proof and their beliefs towards proof. Indeed, we now know that mathematics performance in general, and the reading and writing of proofs in mathematics in particular, is a complex one that depends on a wide expanse of beliefs, knowledge, and cognitive skills and that is uniquely shaped by the realm in which learning occurs (Heinze et al. 2005 ). It is not at all clear, however, which of these beliefs and skills are the most salient for undergraduate students nor how they interact with one another (Moore 1994 ). Consequently, research that examines students’ conceptions of proof in relation to their beliefs and attitudes towards proof, as well as their experiences in learning proof, is greatly needed.

Purpose of the Study

We intend to extend existing research on students’ understanding of proof by describing early undergraduate Footnote 1 students’ views of proof, how these views compare with their beliefs about proof, and relationships between their views of proof and their classroom experiences learning proof. More specifically, the following research questions guided the work presented here:

What types of arguments do early undergraduate students accept as proof Footnote 2 ? That is, are students’ judgments of an argument influenced by its appearance in the form of the mathematical proof and the context in which it is used rather than the correctness of the argument? Do students of different achievement levels in mathematics vary in their ability to choose deductive arguments?

What are early undergraduate students’ beliefs about the nature of proof, about themselves as learners of proof, and about the teaching of proof?

What are early undergraduate students’ classroom experiences with learning proof (as self-reported)?

How do early undergraduate students’ choices of arguments as proofs compare with their beliefs about proof?

Theoretical Background

Perspective on the function of proof in mathematics.

Traditionally, the function of proof has been considered to be that of verification of the correctness of mathematical conjectures. However, as a number of scholars have suggested at various times (e.g., Balacheff 1991 ; Bell 1976 ; DeVilliers 1990 ; Hanna 1990 ; Hersh 1993 ; Lakatos 1976 ), proof has other critical functions in mathematics in addition to verification. In particular, DeVilliers ( 1990 ) proposed that mathematical proof has six interrelated roles: verification, explanation, communication, discovery, systematization, and intellectual challenge. While all six roles are important, our study addressed the first three roles of proof primarily. Footnote 3 In line with Knuth ( 2002a , b ), we found that, while these roles were proposed in regard to the role of proof in the discipline of mathematics, they provide a useful framework for thinking about school mathematics in general, and students’ conceptions of mathematical proof in particular. Below we explicate three of these roles as a framework for our study.

The first role of proof—verification as a means to demonstrate the truth of a mathematical conjecture or an assertion—is the most widely held view of proof (Hanna 1990 ). Indeed, most people who have some understanding of the nature of mathematics as a science expect that for each correct conjecture there is a “sequence of logical transformations moving from hypothesis to conclusion” (DeVilliers 1990 ) whose role is to guarantee the truth of the conjecture in an absolute and definite manner. Although Davis and Hersh ( 1981 ) characterize this as a naïve view of mathematics (as proof can be fallible), formal verifications maintain an important and useful role in mathematics.

Verification, however, is not the only aspect of proof for practicing mathematicians. Often proofs are used as a means to gain further insight into a conjecture, to understand the underlying reasons why the conjecture is true. Of course, not all proofs have equally explanatory power. Hanna ( 1990 ) separates proofs into those that establish certainty and those that explain. Some claim that, in fact, the explanatory role of proof is of greater importance to mathematicians than its verification role (e.g., Hersh 1993 ).

A third role of proof is communication. This refers to the “social interaction about the meaning, validity, and importance of the mathematical knowledge offered by the proof produced” (Harel and Sowder 2007 , p. 817). The emphasis falls on the social process of interaction among individuals while doing mathematics. Lakatos ( 1976 ) has argued that, within the mathematics community, proof is at the center of mathematical discussions that allow an argument to evolve in a dynamical manner. This social interaction also involves the subjective negotiation of not only the meanings of concepts concerned, but implicitly also of the criteria for an acceptable argument. As Hanna ( 1989 ) has said, this social negotiation is very important in the acceptance of a particular result and its proof by mathematicians.

Overall, proof in mathematics is multifaceted and should be viewed as such by learners of mathematics. Indeed, a mature proof conception should include all three functions of proof discussed above, even though previous studies suggest that students view proof only in its first role (verification tool). This multifaceted view of proof leads to the first research question that guided our study, namely, to detail undergraduate students’ conceptions of the various roles of proof and to use these views as a lens for understanding students’ difficulties in proof.

Students’ Beliefs About Proof

One of the goals of the study was to identify students’ beliefs about proof as a subject, about themselves as learners of proof, and about the teaching of proof. Beliefs, attitudes and emotions are used to describe a wide range of affective responses to mathematics (McLeod 1992 ). While all three may impact mathematics learning, it is argued that beliefs about mathematics may reveal students’ deeply held convictions and may play a prominent role in students’ problem-solving behaviors (McLeod 1992 ; Schoenfeld 1992 ). Beliefs are developed gradually over a long time, are influenced by students’ personal experiences, and are influenced by larger cultural factors. Students’ beliefs emerge from personal experience (even personal experience of culture), and, once formed, influence their personal experience by shaping ways they construe contexts in which they operate. Consequently, students’ beliefs both summarize and shape their experience. As Schoenfeld ( 1992 ) noted, “whether acknowledged or not, whether conscious or not, beliefs shape mathematical behavior. Beliefs are extracted from one’s experiences and from the culture in which one is embedded” (p. 360).

McLeod ( 1992 ), in a review of the literature on affective issues, used a variation of the classification of beliefs proposed by Lester et al. ( 1989 ), who described beliefs in terms of the subjective knowledge of students regarding mathematics, beliefs about self as learner of mathematics, and beliefs about mathematics teaching. He concluded that beliefs in the first two of these dimensions play a central role in mathematics learning. Indeed, a brief review of this literature suggests that there is a significant correlation between achievement in mathematics and confidence in doing mathematics, as well as between achievement and perceived motivation and personal control (Fennema and Sherman 1977 ; Lester et al. 1989 ; Reyes 1984 ; Schoenfeld 1989 ). However, McLeod noted a void in the literature on students’ beliefs about mathematics instruction (and, as a result, how beliefs on mathematics instruction may relate to students’ achievement in mathematics)—a void that remains two decades later.

Research on the learning of mathematical proof has not documented students’ beliefs about proof nor their beliefs about their own role in learning proof. Even less is known regarding the possible relationship between these beliefs and students’ achievement in either constructing or evaluating proof. One of our goals in this study was to gain further insights into students’ beliefs with respect to proof in the three dimensions suggested by Lester et al. ( 1989 )—verification, explanation, communication—and the relationship of these beliefs to students’ proof conceptions.

Participants

The participants were 535 undergraduate students from six American universities. The study focused on early undergraduate students—those students who were successful in high school mathematics, hence, enrolled in further, college level mathematics. Participation was voluntary and based on the criteria that participants (1) had not previously taken formal courses in mathematical proof, (2) had not completed any courses beyond an early college mathematics course (first or second semester calculus or equivalent), and (3) were enrolled in a course for which the instructor had agreed to administer data instruments during class instruction. Footnote 4 Most students had not, at the time of the study, declared a major, but were enrolled in mathematics courses that are typical for students who aim to major in mathematics, the sciences, or engineering. Footnote 5 At each university one mathematics professor was asked to oversee the process and ensure that participants satisfied the criteria we set. Once the data were collected, we checked the student-reported data and screened out students who did not satisfy our criteria (for example, data from a group of students who reported being enrolled in a linear algebra course were disregarded).

While it was not possible to randomly select student participants, effort was made to use a variety of educational settings in order to have a sample that could be considered representative with respect to demographics and university type. More specifically, the six data collection sites included large and small public and private universities located in Eastern, Western, and Mid-Western regions of United States. Institutions were selected to represent urban and rural areas and varied with respect to their degree of focus on research. In particular, four of these universities were located on the East Coast, one in the Mid-Western region and one on the West coast. Two of the universities are considered to be research institutions, offering graduate programs in mathematics and the sciences, while the remaining four have a stronger emphasis on teaching at the undergraduate level. One of the six institutions has a strong urban identity with a distinctively diverse student body while one other university has a rural character. The remaining four universities are located in mid-size cities in the US. The six universities also varied with respect to the socio-economic profile of their student bodies: one is a private university, while two others are public universities whose mission is to provide access to students of low socio-economic status and also to students who may be first-generation college graduates, Footnote 6 , Footnote 7

Indeed, statistics (gender, ethnicity, scores on the Scholastic Achievement Test [SAT®]), based on student self-reporting suggest that our sample is representative of the overall college student population of the US. Table 1 , which compares the sample’s representativeness with regards to gender and ethnicity to the overall US college student population (ETS 2003 ), suggests that the demographics for participants in the study are aligned with the overall US college student population.

A subset of 60 students also participated in a written test and an interview. This was a convenience sample; that is, as these students would have to meet with us three times, we invited only those that were geographically accessible to us. The self-reported demographic data, however, suggest that the subset was similar in preparation and demographics to the larger sample of 535 study participants.

Research Instruments

An instrument consisting of (1) a short background demographic questionnaire, (2) a multiple-choice test, (3) a survey questionnaire, (4) a written test, and (5) an interview was designed specifically for the purposes of this study. The first three were administered to the entire sample (as will be explained in the next section), while the last two were only administered to a subset of the study sample.

Background Questionnaire

The first part of the research instrument consisted of questions aiming to provide information regarding the demographics of our study sample. Students were asked to provide information regarding their gender, ethnicity, mathematics aptitude as measured by the Scholastic Achievement Test [SAT®], their general mathematics background (e.g., mathematics classes students completed and grades they received), and their background with respect to proof. This information helped us determine whether our sample was representative of the overall college student population of the US. It was also used for background factors in the data analyses of the multiple-choice part of the instrument.

Multiple-Choice Test

The multiple-choice test was designed to examine students’ views on what comprised a proof, its role and function in mathematics, and students’ competency in evaluating simple mathematical proofs. As such, each item had one correct answer. That is, each item could be scored as correct (1 point) or incorrect (0 points). The test consisted of 38 items that fell in one of two categories:

Items 1–5 elicited students’ views on the overall role (e.g., students’ beliefs on what constitutes proof), meaning, and function of proof.

Items 6–38 examined students’ ability in evaluating simple proofs and elicited their views on the role of these specific proofs. In this case, students were presented with mathematical conjectures and a range of four arguments in support of each of them. Students were asked to select (a) the argument nearest to the approach they would have used had they been asked to produce one, (b) the argument they viewed as most rigorous (mathematically correct), and (c) the argument they would use to convince a peer. They were also asked to assess each argument for its validity, explanatory power and generality. Items 6–14, 15–22, 23–30, and 31–38 corresponded to one of four conjectures respectively, Fig. 1 shows one conjecture Footnote 8 with four supporting arguments and the multiple choice questions asked of students regarding them. The complete instrument is presented in the Appendix .

One mathematical conjecture with four argument choices and corresponding multiple-choice items

The order of the different types of arguments varied among the items. For example, the first argument for the first conjecture was empirical, while the third argument for the second statement was empirical. Similarly, the order of the questions following each conjecture and supporting arguments also varied for each conjecture.

The design of the items was modeled after several studies that examined similar constructs with students of younger levels (e.g., Healy and Hoyles 2000 ), pre-service teachers’ conceptions of proof (e.g., Knuth 2002a , b ; Martin and Harel 1989 ), and undergraduate students’ ability to judge validity of proofs (e.g., Morris 2002 ; Selden and Selden 2003 ). The instrument design followed partly the framework proposed by Balacheff ( 1988 ) and its implementation by Healy and Hoyles ( 2000 ) in that each conjecture was followed by four arguments of specific types:

an argument characterized as empirical (e.g., Argument A in Fig. 1 ),

an argument that relied on common properties presented in a narrative but with insufficient explanation (e.g., Argument B in Fig. 1 ). This argument can, by some standards, be considered deductive,

an argument that could be characterized as a deductive proof written in simple formal style using mathematical symbols (e.g., Argument C in Fig. 1 ), and

a visual argument that relied on common properties of a generic case (e.g., Argument D in Fig. 1 ).

In short, each argument could be classified in two different ways: First with respect to the mode of presentation (i.e., narrative, numeric, visual or symbolic), and, second with respect to the proof schema each represented (i.e., empirical vs. deductive, Footnote 9 as proposed by Balacheff ( 1988 ) and Harel and Sowder ( 1998 )). Note that the instrument included some distractor items in the deductive category. That is, some “deductive-in-appearance” arguments that were nonsensical mathematically were included in the instrument.

The instrument included four mathematical conjectures (shown in Table 9 ) that also varied with respect to mathematical content and level of difficulty. It is important to note that the tasks included in the instrument were ones that first and second-year college students with little exposure to advanced mathematics could understand. Our goal was to make the instrument mathematically accessible to all students in order to maximize students’ levels of response.

Survey Questionnaire

The survey questionnaire was also given to the entire sample—all students who were given the multiple-choice test also completed the survey. It consisted of 45 Likert-Scale questions that aimed to elicit students’ beliefs about proof and their previous classroom experiences with proof, both in college and in high school. The design of the instrument followed common Likert-scale survey methods (e.g., it used varied positive and negative responses that were subsequently reversed, etc.) (Hinkle et al. 1994 ).

To identify students’ beliefs about proof, following the theoretical framework proposed by Lester et al. ( 1989 ) the survey focused on three contexts of proof: (a) beliefs about proof, (b) beliefs about themselves as learners of proof, and (c) students’ previous experiences with proof in instructional settings. Table 10 shows examples of items that were designed to address each of these three contexts of proof. A fourth group of items was developed to address students’ previous experiences with proof. Overall, the survey was designed to:

Identify patterns in student views about mathematical proof and about themselves as learners of proof—enabling us to classify their views in general profiles.

Investigate relationships between students’ profiles (identified through the survey) and students’ proof conceptions (as assessed by the multiple-choice instrument).

Identify patterns in students’ previous experiences with proof (as self-reported).

Written Test

A subset of 60 students were asked to construct proofs for the four conjectures contained in the multiple-choice instrument instead of responding to multiple-choice items themselves. Two weeks later they were also given the multiple-choice instrument and survey.

Pilot Testing and Refining the Research Instrument

The validity and reliability of the instrument was established using a series of psychometric procedures. First, to establish content (face) validity of the multiple-choice instrument, we asked several mathematicians and mathematics educators with experience in the teaching of college mathematics to review the tasks and discuss their appropriateness for the purposes of our study. Further, all parts of the instrument, as well as the written open-format test and the interview procedures, were pilot-tested twice during the two years previous to the study reported here. The pilot instrument was administered to a group of 100 students during the first year at one university and 400 students the subsequent year at all six participating universities. The data from student responses were analyzed each year and each part of the instrument was modified during each phase of pilot testing on the basis of these responses.

Each year we conducted an item analysis (item difficulty and item discrimination). Item difficulty index ( p -value), defined as the proportion of examinees who answered the item correctly, can range from 0 to 1. Items with higher p-values (e.g., p -value = 0.9) are easier than items with lower p-values (e.g., p -value = 0.3). Although, in the final pilot test, p -values for the multiple-choice items indicated a range in level of difficulty (0.12 ≤ p -value ≤ 0.68), overall, p -values were positively skewed suggesting that the test was moderately difficult. In particular, 12 items were considered difficult ( p -value < 0.30) and the remaining 26 items were considered moderately difficult (0.31 < p -value < 0.7).

Item discrimination is an index that indicates the contribution of each item to the total score—a correlation between the item score and the total score. Item discrimination scores can range from −1 to 1. The closer the value of item discrimination to the value 1, the more informative the item is. A discrimination value equal to 0 means that the item does not provide any information and such items should be excluded from subsequent analysis. A negative discrimination index is an indication of poorly developed item and should be excluded from the analysis. Several factors may contribute to the negative or near zero discrimination indices. These include items that are poorly worded (items that are poorly worded and might cause confusion should not be included in the scoring of the test as they may result in misleading findings); items that do not measure the same construct as the remaining items in the test (these items contribute in a lower test reliability (internal consistency) and should be removed from the test); items that are scored in error (the key of the items was checked and no errors in scoring had been made). After the initial pilot-testing phase of the study (see Data Collection and Analysis Procedures) , items with negative or zero discrimination values were dropped from the instrument. Hence, all items used on the final version of the instrument were ones that had a positive discrimination index during the final data collection phase.

Finally, the reliability of the multiple-choice test was computed using the Cronbach alpha formula and was equal to 0.79 ( α = 0.79). Similarly, the reliability of the survey questionnaire was computed and was equal to 0.89.

Data Collection and Analysis Procedures

Data collection.

The short background demographic questionnaire, the multiple-choice test, and the survey questionnaire were administered to 535 students in the six participating universities early in the Fall semester under comparable testing conditions. To minimize order effects, the order in which the multiple-choice test and the survey questionnaire were administered was interchanged: Half the students received the multiple-choice instrument first and the survey questionnaire second, while the remaining participants received the two parts in reverse order.

A subset of the participants was also asked to participate in the written test and a subsequent interview.

Written test: Two weeks prior to taking the multiple-choice test and survey questionnaire described above, 60 students were asked to also construct proofs to four conjectures. All students were administered the written test within a classroom setting and were given sufficient time to respond to the items (students were given 1 hour to complete the test and were offered more time if needed). The 60 students attended an urban and a rural college on the East Coast.

Interview: Of the 60 students who took the written test, 40 participated in interviews. The interviews occurred 2 weeks following the administration of the multiple-choice test. An effort was made to interview students who represented the broader spectrum of participants, both with respect to demographics and with respect to performance on the multiple-choice test. That is, students who received high or low scores on the multiple-choice instrument were encouraged to participate in the interview (all 60 students were invited to do so). The 30-min clinical interview consisted of a set of structured questions to probe the reasons for students’ responses in the written and the multiple-choice instruments. Each interview was tailored to the student in it. The student was asked to discuss possible discrepancies in his responses, the reasons for choices he had made for a particular argument as either “rigorous” or “explanatory”, and why he had assessed a certain argument as logically flawed, etc. Our aim for these interviews was to gain further insight into students’ written and multiple-choice test responses.

Data Analysis

In order to better understand the findings of the study, we applied an integrated approach for analyzing data. Information from the multiple-choice test, background demographic questionnaire, survey questionnaire, written test and interviews were used in an integrated manner in order to identify patterns and better understand the findings of the study. In general, data from the multiple-choice were presented in terms of total test scores, while information collected from the various parts of the questionnaire was presented in the form of percentages.

To analyze the data from the survey questionnaire, students were placed into three groups based on their score on the multiple-choice part of the instrument: (a) high-performing (students who scored 26–38 correct responses), (b) middle-performing (students who scored 14–25), and (c) low-performing (students who scored 1–13). Further, students in each group were classified into four profiles based on their beliefs about proof and their own role in their learning of proof (as in Carlson et al. 1999 ).

The questions we were interested in answering involved frequencies of students in the different groups (e.g. high- and low-performing, or agree and disagree) and how each of these groups compared in their approach to proof. For example, we were interested in examining whether more low- than high-performing students chose a specific approach in producing proof. In other words, were there any patterns between performance level and students’ approach to or perception of producing proof? Hence, one example of a hypothesis is the following: “There was no statistically significant difference between the number of students in the high- and low-performing groups in choosing the deductive-symbolic argument”.

Because the main focus of the hypotheses tested was the comparison of the frequencies between two or more groups, a chi-square test for dependent samples was applied. Data on frequency are not expected to be normally distributed. In such cases, non-parametric tests like the Chi-square test is recommended (Hinkle et al. 1994 ), as Chi-square is a test that is usually applied to compare two or more groups on nominal level variables.

We recognize that the use of inferential statistics is highly problematic for samples that are not selected randomly; a sample that is representative of the population is a vital factor in generalizing and making inferences about the findings of the study. One way of obtaining such samples is by applying random selection approaches. However, in quasi-experimental studies where such an approach is not feasible, alternative ways like stratified methods can be used to obtain a sample that is representative of the population. In the current study, we attempted to recruit sites that represent the overall college population. As stated earlier, an evaluation of the selected student sample showed that the participant sample was aligned with the overall US college student population with respect to demographic variables such as gender and race. Thus, we feel confident that inferences about the findings of the study could be generalized to the population.

Written Test and Interview Data Analysis

Following the analysis of the multiple-choice instrument, we attempted to contextualize the descriptive statistics and the statistical correlates identified in the quantitative analyses through data from the student interviews. In particular, proof constructions of students who were interviewed were coded with respect to proof schemas (i.e., as empirical or deductive) using the Harel and Sowder ( 1998 ) classification, and mode of presentation (i.e., as narrative, symbolic, numeric or visual). These proof constructions were subsequently compared and contrasted with students’ choices on the multiple-choice test using correlation tests. In Fig. 2 we present four examples of student-constructed proofs. The work shown of students A and B represents their attempts to construct a proof for Conjecture I. Student A produced a proof we coded as empirical-numeric, while Student B produced a deductive-symbolic proof. Note that the proof is not complete, but the student displayed a disposition towards reasoning in a deductive manner. The work shown of students C and D represents their attempts to construct a proof for Conjecture II. Student C produced an empirical-numeric proof. Student D produced a deductive-narrative proof—even though he attempted to use symbols, his response was presented primarily in a narrative format. Overall, the data that resulted from the written test and interviews were used in this study as supportive to the main data produced by the multiple-choice and survey instruments.

Student-constructed proofs

We first report our findings with respect to the types of arguments that early undergraduate students accept as proof. We then present students’ beliefs about proof and their recollections of instructional experiences regarding proof.

Students’ Proof Conceptions

Examining students’ conceptions regarding the types of arguments that they may accept as proof was the first goal of the study. In the multiple-choice part of the instrument, students were asked to select arguments nearest to the one they would construct if they were asked to produce one. Table 2 shows the distribution of students’ choices in these items.

Students’ Views on the Types of Arguments That Most Resembled Their Own

The first column of Table 2 shows that students’ choices of arguments that most closely resemble what they would produce for Conjectures I–III using the mode of presentation of the conjecture as a lens to understand students’ choices. Students’ choices were almost evenly split between numeric, symbolic, and narrative arguments. Only a small number of students chose the visual argument. For Conjecture IV (supplementary angles) the visual argument (Choice A) was the most popular one (chosen by 38 % of the students). It is worthwhile to point out that Conjectures I–III were about numeric relationships while Conjecture IV was about a geometric relationship.

When using proof schema as a lens (deductive vs. empirical) a different picture emerges: For conjectures I–III about two thirds of the students consistently reported that they would construct one of the two types of deductive proofs—either narrative-deductive or symbolic-deductive (62, 60 and 60 % for Conjectures I–III respectively). For Conjecture IV, 50 % of the students reported that they would construct one of the two types of deductive proofs.

Connecting Student Responses to Their Mathematical Aptitude

In order to better understand students’ overall responses to the multiple-choice tasks, we used data from the background questionnaire to identify some possible factors that may have impacted their choices of arguments that (as they claimed) most closely resembled their own. In particular, we used students’ self-reported scores on the mathematics part of the Scholastic Achievement Test Footnote 10 [SAT®] and looked for differences among high-performing students (SAT score on the mathematics of 660 or higher) and low-performing students (SAT score lower than 660). The data (shown in Table 2 ) indicated that high-performing students were consistently more likely to choose the “deductive-symbolic” argument than their low-performing counterparts. For example, for Conjecture I, 58 % of the high-performing students chose the deductive-symbolic argument compared to 22 % of the low-performing ones.

Comparing Students’ Proof Constructions with Their Responses to the Multiple-Choice Instrument

Two weeks prior to the administration of the research instrument, a subset of the study participants was asked to construct their own proofs for each of the four conjectures. Hence, we were able to compare students’ actual proof constructions and their self-reports as to which one of the given arguments would be closest to the one they would construct. Students’ own proof constructions were coded with respect to proof schemas (i.e., as empirical or deductive) and with respect to mode of presentation (i.e., as narrative, symbolic, numeric or visual) as shown in Fig. 2 .

Table 3 shows the distribution of types of students’ responses in each item as well as their choices in the multiple-choice instrument. There were some remarkable discrepancies in the similarity of students’ choices in the multiple choice instrument regarding the argument they selected as closest to their own approach and their actual proof constructions for each of the four conjectures. The majority of the students who completed the written test consistently constructed proofs that we classified as “empirical-numeric” (45, 49 and 75 % for Conjectures I–III, respectively) even though the majority of the same students (62, 60 and 60 % for Conjectures I–III, respectively) reported that they would construct either a narrative-deductive or a symbolic-deductive argument. In fact, for Conjecture II, the argument that was the most commonly reported as closest to one’s own approach was the least popular type for students’ own proof construction Footnote 11 : 37 % of the students reported that a deductive-symbolic argument was most like their own, while only 17 % of them actually constructed this type of argument. For all three conjectures the discrepancy between students’ own constructions and their choices was statistically significant ( χ 2 = 52.66, df = 9, p < 0.5; χ 2 = 27.33, df = 9, p < .05; χ 2 = 68.66, df = 9, p < .05 for Conjectures I–III respectively). Further, Table 3 shows that when students attempted to go beyond the empirical-numeric approach, they were more likely to give informal narrative arguments rather than either symbolic or visual arguments.

Our follow-up interviews indicated that students often selected the deductive argument because they viewed it as the best proof, one that matched relatively well their intuitive understanding of the given conjecture, even though they would not be able to construct one on their own. The excerpt from Tyler’s interview illustrates this point:

Um, yeah, the reason why I wrote this was… I knew um what it had to say, I just didn’t know how to say this kind of thing. So, the easier… I took the easy way out and just did uh… some examples to kind of prove my point, rather than… I would have done it like (b) [deductive-symbolic] if I could just formulate my ideas better in my head.

Taken together, the data from students’ responses to the multiple-choice instrument and students’ proof constructions suggest that students are better at choosing a correct mathematical proof than constructing one.

Perceptions on the Role and Function of Proof

A second goal of the study was to examine students’ perceptions on the role of proofs in mathematics as a discipline. Students were asked not only to choose the approach that would most closely resemble their own hypothetical approach, but also to select the arguments they viewed as most rigorous (mathematically correct), and the arguments they viewed as most explanatory. Table 4 shows the distribution of students’ choices in these items.

Regardless of students’ choices of the argument closest to their own approaches, there was a remarkable similarity in students’ responses across the four conjectures when asked to choose the “most rigorous” approach. For each of the four conjectures, over half of the participants were able to identify correctly the deductive-symbolic argument as the most rigorous proof (68, 56, 52 and 58 % for Conjectures I–IV respectively) while less than one-fifth chose either the empirical-numeric or the empirical-visual arguments for any of the four Conjectures.

Furthermore, when asked to choose the most “explanatory” argument, that is, the argument they “would use to explain the problem to one of their peers”, students’ choices for Conjectures I, III and IV were relatively closely aligned with their choices of the arguments that would be close to their own approach. In other words, students most closely identified their own hypothetical proof constructions as arguments that were explanatory and communicable. However, for Conjecture II, students’ choices were evenly distributed among the four given arguments. Even so, it is worth noting that for all four conjectures the majority of the students (at least 75 % of the students for each conjecture) did not choose a deductive argument as explanatory.

The narrative argument was the most frequently chosen by students as the most “explanatory” one for Conjectures I–III. During the follow-up interviews we asked students who selected this argument as the most explanatory specifically for reasons why they did so. Many suggested that they had made this choice because they believe that natural language is more explanatory than symbols. When asked for their reasons for choosing the symbolic-deductive arguments as rigorous the same students suggested that they has made this choice because symbols are more “mathematical”. These are illustrated in the interview excerpts below:

It kind of has more laymen terms in it and um… cause (c) [deductive-symbolic argument] is a good answer but it just has a lot of variables in it. It’s easier to think this way rather… like when I first read it, I didn’t think that an even number has to be divisible by two and so I’ll set one to two times an integer. I just kind of thought of that can be divided by two and has the same common factor, so… more with words… […] the rigorous one would be (c) [the symbolic-deductive argument]. Um, it is more mathematically um based.

[I chose the narrative argument] because it is a simple, straightforward as saying like, all right two plus two is four.

Why did you choose different arguments to be the most rigorous and to be the most explanatory?

Rigorous is more like it is true, whereas explanatory is just showing you it is true.

(a) [narrative] is definitely the one I would use to explain it to somebody. Um cause it’s easier to explain in language than in symbols, like mathematical symbols […] [The symbolic-deductive argument] is more like mathematics, you know, like using equations and… it uses actual mathematics to prove instead of just words.

Responses to other questions in the multiple-choice instrument provided further insight into how the students assessed each type of argument. Four questions following each of the three conjectures asked students to determine whether they considered each of the arguments to be either logically flawed, correct but not rigorous, one that shows that the statement is true for some cases, or a strong mathematical argument. (In Fig. 1 , item 10 shows how the question was posed.) As Table 5 shows, students were aware of the limits of an empirical approach. The majority of the students (56, 51, 52 and 43 % for Conjectures I–IV, respectively) assessed the empirical-numeric argument to be “true for only a few cases”, while only a small subset (12, 15, 14 and 21 % for Conjectures I–IV respectively) assessed empirical-numeric arguments to be “strong mathematical argument(s)”.

At the same time, the majority of the students (64, 59, 52 and 53 % for Conjectures I–IV respectively) assessed the deductive-symbolic argument to be a “strong mathematical argument”. Finally, students’ assessment of the narrative and the visual arguments were fairly uniform across the three conjectures: about 40 % of the students said that the arguments were correct but not rigorous.

A third goal of the study was to identify students’ beliefs about proof as a subject, about themselves as learners of proof, and about the teaching of proof, and the relationship of these beliefs to students’ choices of arguments as proofs. Towards this end we used students’ responses to the survey questionnaire in the research instrument.

Table 6 gives a summary of the percentage of students who agreed with statements regarding students’ beliefs towards mathematical proof in relation to their performance on the multiple-choice part of the instrument. Students were placed in three groups based on their score on the multiple-choice part of the instrument Footnote 12 : (a) high-performing (students who scored 26–38 correct responses), (b) middle-performing (students who scored 14–25), and (c) low-performing (students who scored 1–13). Using these criteria, a total of 36 students (6 %) were categorized as high performing, 248 students (46 %) were categorized as middle-performing, and 249 students (46 %) were categorized as low performing. Footnote 13 For the high- and low-performing groups, we report here the percent of students who indicated agreement and disagreement with each of the statements. “Agreed” reflects the percent of students selecting “agree” or “strongly agree” on each of the statements, and “Disagreed” reflects the percent of students selecting “disagree” or “strongly disagree”.

The data in Table 6 suggest that there is a difference in high- and low-performing students’ beliefs about proof and beliefs about themselves as learners of proof. High-performing students tended to hold more positive beliefs about proof than their low-performing counterparts. For example, four fifths (80 %) of the high-performing students agreed that “constructing proofs is an important part of doing mathematics”, while less than half (48 %) of the low-performing students agreed with the same statement. The difference between these distributions was highly significant for this question ( χ 2 = 5.607, df = 1, p < .05). Similarly, high- and low-performing students differed in their choices for questions 25, 26, and 27, which focused on the centrality of proof in learning mathematics ( χ 2 = 4.001, df = 1, p < .05; χ 2 = 9.434, df = 1, p < .05; χ 2 = 13.340, df = 1, p < .05, respectively).

High-performing students also appeared to be more confident in themselves as learners of proof than low-performing students. For example, 83 % of the high-performing students agreed that “It bothers [them] if an instructor tells [them] just to accept a mathematical statement without explaining why it’s true” (item 34) and 92 % of the same set of students agreed or strongly agreed that “[they] feel better about [their] understanding of mathematics if [they] understand why mathematical theorems are true”. Only 51 and 52 % of the low-performing students agreed with these two statements. The difference between the distributions of students’ choices for the first item (item 34) was highly significant for this question ( χ 2 = 4.271, df = 1, p < .05). Differences in high and low-performing students’ responses for questions 30 and 32, which focused on their positive attitude toward proof, were also significant ( χ 2 = 3.952, df = 1, p < .05; χ 2 = 9.233, df = 1, p < .05 respectively).

There was little difference between the two groups’ beliefs about the teaching of proof. For example, 58 and 60 % of the high-performing and low-performing students, respectively, agreed or strongly agreed that “If a mathematical statement requires proof, I think it is the instructor’s (not students’) responsibility to present this to the class”.

Linking Student Profiles on Beliefs About Proof to Students’ Proof Conceptions

As the first two belief categories (“beliefs about proof” and “beliefs about self as learner of proof”) revealed the most difference between high- and low-performing students, these data were further analyzed to help us gain a better understanding of the differences. Students were classified into profiles based on their beliefs about proof and the learning of proof, and these profiles were associated with students’ scores on the multiple-choice test.

First, students were classified into four different profiles according to their responses in the survey items that addressed their beliefs about proof and their own role in their learning of proof. The profiles were: (1) negative or (2) positive with respect to their beliefs about proof, and (3) passive or (4) active with respect to their perceived role in their own learning of proof. Six items (24–29) were used to characterize positive or negative views about proof, and seven items (30–35 and 40) were used to characterize students’ active or passive stance on their role in their own learning of proof.

Students’ choices in these survey items were quantified by a Likert scale (1: strongly disagree, 2:disagree, 3: neutral, 4: agree, and 5: strongly agree). Students who received a score of 24 or higher (of a possible 30) for their responses to items regarding their beliefs about proof were characterized as holding positive views, while students who received a score of 18 or lower on these items were characterized as holding negative views. Footnote 14 Similarly, students who received a score of 28 or higher (of a possible 35) for their responses to items regarding their perceived role in their own learning of proof were characterized as having an active stance, while students who received a score of 21 or lower on these items were characterized as having a passive stance towards proof. Footnote 15 Each student was characterized as either “positive” or “negative” and as “passive” or “active”.

Once again, we looked at the percentage of students who were classified into each profile in relation to their performance on the multiple-choice part of the instrument. Table 7 gives a summary of these data. In comparing these data, we found that 52 % of the high-performing students held a positive and active stance towards proof and the learning of proof, while only 25 % of the low-performing group held similar views. That is, high-performing students are more likely to hold a positive and active stance towards proof than their low-performing counterparts. The data for the “negative and passive” profile supported this result: 44 % of the low-performing students held a negative and passive stance towards proof, while only 24 % of the high-performing students held this stance.

Students’ Perceived Instructional Experiences in Learning Proof

We used data from the survey questionnaire and the background questionnaire to consider students’ self-reported classroom experiences with proof in relation to their proof conceptions. Table 8 summarizes these data.

Table 8 indicates that students who participated in this study reported to have instructors who did not make proof a central part of their mathematical experience. In particular, only 25 % of students reported that previous classroom experiences emphasized the importance of developing proofs, and only 19 % reported that constructing proofs was a regular part of classroom activity. Indeed, although 49 % of students reported that instructors did prove mathematical claims and theorems they made to the class, this percentage suggests that instructors were likely as not to make assertions without justification. Moreover, students reported that when instructors did provide a proof, most (80 %) presented only one argument. Even then, only 49 % of students agreed that their instructors expected students to understand the proofs presented to them. It is worth noting that 62 % percent of students reported that prior instructors used examples to prove mathematical claims.

When students were asked to describe their own experiences and role in constructing proofs, they consistently noted that their participation was peripheral. Less than one fifth (19 %) of the students reported to have “played a significant role in developing proofs during math class.” This was further corroborated by the fact that only 7 % of these students presented their proofs to the class and less than a fourth (23 %) experienced instruction in which proofs were “constructed through whole-class discussions that [built] on students’ ideas”. Indeed, for the majority of the students (67 %), their “experience is that math class is more about taking notes on the instructor’s lectures than arguing with [their] peers about why mathematical statements might be true or not”. Less than one forth of the students worked either individually (23 %) or in groups (12 %) to construct proofs (Tables 9 and 10 ).

These self-reported experiences were consistent regardless of the performance level of students. That is, there was little difference in student responses based on their designation as high performing or low performing.

Regardless of the types of arguments that students accept as proof as indicated by the multiple-choice portion of the instrument, they reported having similar experiences in their mathematics classes with respect to doing proofs. The same finding applies to groups with different mathematics aptitude: students with either high- or low-aptitude with respect to mathematics ability (as indicated by their self-reported SAT mathematics scores) reported similar instructional experiences.

This paper reports results from a study that examined U.S. undergraduate students’ conceptions of proof. In this section we summarize and discuss the main findings with respect to the four main goals of the study: understanding undergraduate students’ conceptions of proof based on the arguments they accept as proof, their beliefs about proof, their self-reported classroom experiences with proof and how these three issues compare.

What Are Early Undergraduate Students’ Conceptions of Proof?

A majority of students chose the deductive argument from proposed arguments for each of four conjectures as the one that would most likely closely resemble their own (had they been asked to construct one), and they also chose deductive arguments to be the “most rigorous ones” and recognized that empirical arguments were limited (“true for only a few cases”). This finding conflicts with previous work in this area. Previous studies on secondary school students, as well as on some classes of college students, reported students’ strong preference for empirical arguments (with respect to proof schema) and numeric arguments (with respect to mode of presentation). Healy and Hoyles ( 2000 ), for example, showed that secondary school students accept empirical arguments as proofs. Similarly, Martin and Harel ( 1989 ) showed that pre-service elementary teachers have a strong preference for inductive arguments, a result that was more recently affirmed by Morris ( 2002 ).

The finding may be explained, in part, by the difference in age between our study participants and other studies which focused primarily on high school students. It is worth recalling that the instrument intentionally consisted of tasks which required that students know something about the mathematical ideas entailed by a conjecture and by the proposed arguments for it. It is possible that, had the study used a set of tasks requiring higher-level mathematical knowledge, the study participants might have responded differently (e.g., they might have then chosen empirical arguments) and this is an issue that is worth pursuing further. Nonetheless, the fact that students in this study appear to have a better conception of what constitutes an acceptable proof than seen in prior studies is encouraging and provides college mathematics instructors a base on which they can build further instruction on proof. Finally, it is worth investigating whether a possible difference in time and curricular trends between past work and this study: It is possible that students in the past few years may have had greater experience and exposure to mathematical proof so they can, at least, identify a deductive argument. However, at this time this is only a hypothesis; while there have been efforts to make proof a regular part of high school students’ mathematics experience, and national mathematics organizations (e.g., the Mathematical Association of America and the U.S. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics) have been calling for proof to take a more central role in the mathematics curriculum, one might question the fidelity of the implementation of these calls. At this time, there are no actual data to show that this has actually happened and participating students’ reports on their classroom experiences with proof certainly do not suggest that this is the case.

Note that students’ choices as to which argument they might accept as proof varied for each of Conjectures I–IV, making it initially hard for us to discern a clear pattern in students’ proof conceptions. This discrepancy invited us to consider the nature of the four conjectures. For Conjectures I and III, more students chose the argument presented in narrative form, while for Conjecture II, the majority of the students chose the argument presented in symbolic form. One possible explanation for the discrepancy with respect to students’ choices in mode of presentation could be due to the statements of Conjectures I and III in natural language and that of Conjecture II in more symbolic form. In other words, the statement of the problem (whether in natural or symbolic language) might affect how students try to prove it (assuming the respondent has had no formal class that focuses on proof, as was the case with our subjects). Similarly, Conjectures I and III reside in number theory, while Conjecture IV in geometry, where diagrams are a more natural part of arguments. As a result, a higher number of students might have chosen a visual argument for Conjecture IV. Both the way a conjecture is stated and the content topic (i.e., geometry) could be considered surface features, and, as such, might have affected students’ solution choice. Studies on expertise indeed show that novices tend to focus on surface characteristics of tasks such as content topic and mode of presentation (e.g., Chi et al. 1988 ; Schoenfeld 1985 ; Stylianou and Silver 2004 ).

Even though the majority of those students who were also asked to construct their own arguments did not construct valid deductive proofs, the same students still indicated a preference for general arguments. This somewhat conflicting finding suggests that students may understand the essence of deductive mathematical arguments (at least in the case of relatively intuitive conjectures that were used in the instrument for this study) but lack the ability to use the representational system necessary to write symbolic-deductive arguments (Weber and Alcock 2006 , 2009 ). Students’ proofs were well-aligned with findings in earlier studies in that, when asked to produce a proof, students construct empirical-numeric proofs. In broader terms, the discrepancy between the arguments that students actually produced and those they selected as closest to what they would construct on their own is reminiscent of research regarding comprehension versus production (e.g., Clark and Hecht 1983 ). That is, it is often easier to understand a proof than to produce one. The knowledge that early college students appreciate deductive arguments yet lack a rich mathematical representational system to articulate their ideas might lead textbook authors and instructors to make ideas of proof more explicit in curricular materials and instruction.

With respect to students’ conceptions on the function of proof, the results show that students do not perceive deductive arguments as explanatory. Instead, students chose the narrative arguments as the “most explanatory” ones. This finding is similar to the findings of Healy and Hoyles ( 2000 ) for middle school students. In their study, too, students saw as explanatory those arguments that were presented to them in words. Healy and Hoyles suggested that it is possible that students

simultaneously held two different conceptions of proof: those about arguments they considered would receive best mark and those about arguments they would adopt for themselves. In the former category algebraic arguments were popular. In the latter, students preferred arguments that they could evaluate and that they found convincing and explanatory, preferences that excluded algebra (p. 425).

It appears that the four or more years of additional mathematics instruction that the students in our sample received did little to change this double-conception held by middle school students. This finding confirms views expressed earlier in the literature. As Schoenfeld ( 1994 ) suggested, proof in traditional high school and undergraduate instruction is used mostly as a verification tool, and not in a way that creates “personal meaning or explanatory power for students” (p. 75). Hence, many students may perceive proof as a task for the instructor, not as a tool for thinking more deeply about mathematics (Alibert 1988 ). Harel and Sowder ( 1998 ) argued that teachers use “proof methods and implication rules that in many cases are utterly extraneous to what convinces [students]” (p. 237). Moreover, proving a statement for which the proof already exists or is intuitively obvious leads to the perception that proof activity is not a process of discovery (Schoenfeld 1994 ; Wheeler 1990 ) and results in a focus on knowing what, which conceals the value of knowing why .

Finally, our analysis showed that students’ proof conceptions were related to their overall mathematics aptitude and achievement. High-performing students on the SAT were consistently more likely to choose the “deductive-symbolic” argument than were low-performing students. This might indicate that proof cannot be viewed as an isolated competency or as an isolated part of mathematics instruction and curriculum, but one part of the overall mathematical competency.

What Are Undergraduate Students’ Beliefs About Proof?

Overall, high-performing students tended to hold a more positive and active stance with respect to their beliefs about proof than their low-performing counterparts. Hence, our findings resonate with findings on general beliefs about mathematics and general mathematics performance. That is, just as high-performing students tend to hold more positive beliefs about mathematics and about themselves as learners of mathematics (McLeod 1992 ), they also tend to hold more positive beliefs about proof and about themselves as learners of proof than their low-performing counterparts.

Results from our analysis suggest that classrooms with passive learning environments might implicitly reinforce low performance on proof activity in particular and mathematical activity in general. It, therefore, raises the instructional challenge to build classrooms where students can be actively engaged in learning about proof as a way to potentially alter a negative, passive stance towards it. The extent to which classroom environments can facilitate an active, positive stance on proof remains an area for further research.

What Are Students’ (Self-Reported) Classroom Experiences with Learning Proof?

Overall, students who participated in this study report to have experienced little instruction that focuses on proof. It is possible that their perception of the kind of instruction they did receive often marginalized their participation in constructing proofs and did not help them develop the representational systems to build general arguments. The finding that students experience with proof is limited is not surprising; previous studies have shown similar findings. For example, in a relatively broad study involving 62 mathematics and science teachers in 18 high schools in six states, Porter ( 1993 ) found that “on average, no instructional time is allocated to students learning to develop proofs, not even in geometry”. Similarly, the report on the videotape study in the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) noted that “the most striking finding in this review of 90 classes was the rarity of explicit mathematical reasoning in the classes […] almost total absence of explicit mathematical reasoning” (Manaster 1998 , p. 803).

Students’ reports that prior instructors often used examples to prove mathematical claims is also worth noting. This raises the question of whether students’ reliance on empirical arguments (e.g., Knuth et al. 2002 ; Porteous 1986 ) might be a reflection of their instructional experiences as much as cognitive issues in their understanding of proof. It also raises the question regarding when instruction should shift from the use of empirical arguments to helping students learn to develop more general arguments (some research indicates that this can begin as early as the elementary grades—see Kaput et al. ( 2008 ); Stylianou et al. 2009 ).

Overall, these data suggest that, regardless of entry-level college students’ understanding of proof, they report to have had limited classroom experiences with seeing or constructing proofs. Additionally, these experiences were often the presentation of empirical arguments by their instructors, with students playing a passive role in their development. As such, these data bring to light persistent instructional paradigms that remove the learner from actively participating in classroom activity and in which individual learning is valued over collaborative learning. Moreover, these types of classroom experiences could help explain why, even at the college level, students often initially cannot construct general arguments and rely instead on empirical arguments. Even though our data suggest that students do know how to recognize a more appropriate deductive argument, their responses to the survey suggest that they have not had the kinds of instructional experiences that would support their learning how to build general, deductive, rigorous arguments.

Finally, this limited experience with proof appears to be consistent in both high- and low-performing students. Regardless of students’ conceptions of proof as indicated by the multiple-choice portion of the instrument and regardless of their overall mathematics achievement as indicated by the SAT, they reported having similar experiences in their mathematics classes with respect to doing proofs.

This study suggests that there is much work to be done in K-14 education to prepare students to understand and construct proofs. In particular, the results suggest that students have potential to develop general arguments, but lack the representational systems to do this. Moreover, the results reported here suggest that students often are not participants in the process of constructing proof, nor do they typically see non-empirical arguments during instruction. This challenges curriculum and instruction to provide experience and opportunity to help students build the tools necessary for understanding and developing proofs.

We define “early undergraduates” to be students who are in their first or second year in college and have not completed a course beyond second semester calculus and have not taken a formal course on proof.

The term “proof” is often reserved to describe formal and precise arguments given by mathematicians. For example, the Harper Collins Dictionary of Mathematics defines proof as “a sequence of statements each of which is either validly derived from those preceding it or is an axiom or assumption, and the final member of which, the conclusion, is the statement of which the truth is thereby established”. However, here we use a broader definition of proof as an argument that one makes to justify a claim and to convince oneself and others of the claim’s veracity. By this definition, proofs can have varying levels of strength.

While proof can play an important role in the discovery of new mathematics (DeVilliers 1990 ) and can be central to the systematization of results such as theorems and axioms into a broader deductive system, it is highly unlikely that undergraduate students have had opportunities to experience these roles of proof. Earlier studies, e.g., NAEP results (Silver and Kenney 2000 ), have shown that students’ experiences with proof are limited, hence we chose to focus on the most “obvious” roles of verification, explanation and communication that are the most likely to have been part of these students’ experience.

No data were collected regarding the current instruction or instructors of the participating students. The instrument was administered early in the semester, hence the current instructor may not have had a significant impact on the students, and, the students were explicitly asked to report on their previous mathematics education, not experiences in their current class.

The majority of the participants were enrolled in a typical first or second semester calculus course. We did not solicit participation from students enrolled in courses such as calculus or quantitative literacy courses for non-science majoring students.

While we attended to university SES data, we did not collect SES data on individual students.

As the preparation of the students at all participating colleges was comparable (by study design) we chose not to investigate type of university as a source of variation in our results. This would be beyond the scope of this study.

We called these statements “conjectures” rather than “theorems” or “statements” to minimize the possibility that students would tacitly assume that they were offered as true statements. We hoped that they would take each statement as coming from someone who genuinely wondered whether it was true,

A number of researchers in the field have identified the three main types of proof schemas as empirical, inductive and deductive. Some, like Harel and Sowder ( 1998 ) have refined these categorizations by identifying sub-categories. Here, we only use the broad three categories.

The SAT is a measure of the critical thinking skills for academic success in college. It measures skills in three areas: critical reading, math, and writing, and it is typically taken by high school juniors and seniors. Each section of the SAT is scored on a scale of 200–800, with two writing sub-scores for multiple-choice and the essay. For more information visit www.ets.org or www.collegeboard.org

This was with the exception of visual arguments that none of the students used in their own construction of proofs.

We need to re-iterate that as these items elicited students’ personal views or preferences with respect to proof, a “score” only indicates the degree of sophistication with respect to proof conception.

There is a large discrepancy in the number of students in each of the three groups. In particular, there were only 36 high-performing students. While changing the criteria for high-, middle- and low-performing could have provided more balanced numbers, it would also diffuse any differences and response patterns.

A score of 24 or higher indicated that students primarily agreed or strongly agreed on the 6 items that were used to characterize positive or negative beliefs about proof, while a score of 18 or lower indicated that students primarily disagreed or strongly disagreed on these items. Scores of 19 to 23 could indicate mixed and “neutral” beliefs that made it difficult to provide a clear profile for these students.

A score of 28 or higher indicated that students primarily agreed or strongly agreed on the 7 items that were used to characterize students’ active or passive stance on their role in the learning of proof, while a score of 21 or lower indicated that students primarily disagreed or strongly disagreed on the 7 items.

Alibert, D. (1988). Towards new customs in the classroom. For the Learning of Mathematics, 8 (2), 31–35.

Google Scholar

Balacheff, N. (1988). Aspects of proof in pupils’ practice of school mathematics. In D. Pimm (Ed.), Mathematics, teachers and children (pp. 216–230). London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Balacheff, N. (1991). The benefits and limits of social interaction: The case of mathematical proof. In A. Bishop, S. Mellin-Olsen, & J. van Dormolen (Eds.), Mathematical knowledge: Its growth through teaching (pp. 175–192). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Bell, A. (1976). A study of pupils’ proof-explanations in mathematical situations. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 7 , 23–40.

Article Google Scholar

Carlson, M., Buskirk, T., & Halloun, I. (1999). Assessing College Students’ Views About Mathematics With the Views About Mathematics Survey . http://sigmaa.maa.org/rume/crume2011/RUME2011_FinalSchedule_files/ContributedReportsShortPapers/Carlson%20Rasmussen_proceedings.pdf

Chi, M. T. H., Glaser, R., & Farr, M. J. (1988). The nature of expertise . Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Clark, E., & Hecht, B. (1983). Comprehension, production, and language acquisition. Annual Review of Psychology, 34 , 325–349.

Committee on the Undergraduate Program in Mathematics. (2000). Curriculum Guide. Mathematical Association of America. http://www.maa.org/news/cupm_text.html

Davis, P. J., & Hersh, R. (1981). The mathematical experience . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

DeVilliers, M. (1990). The role and function of proof in mathematics. Pythagoras, 24 , 7–24.

Dreyfus, T. (1990). Advanced mathematical thinking. In P. Nesher & J. Kilpatrick (Eds.), Mathematics and cognition: A research synthesis by the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education (pp. 113–134). Great Britain: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Educational Testing Services. (2003). Sex, race, ethnicity and the performance on the GRE General Test . Princeton: ETS.