- Resources & Tools

Take Action

Join the movement of young people working to protect our health and lives

Action Center

New research: quality sex education has broad, long-term benefits for young people’s’ physical and mental health.

An extensive review finds that in addition to helping to prevent teen pregnancy and STIs, sex education can help prevent child sexual abuse, create safer school spaces for LGBTQ young people, and reduce relationship violence

Washington, DC – New research published in the Journal of Adolescent Health has identified a wide variety of benefits of comprehensive, quality sex education.

For Three Decades of Research: The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education , Eva S. Goldfarb, Ph.D. and Lisa D. Lieberman, Ph.D. examined studies from over three decades of research on sex education and found “evidence for the effectiveness of approaches that address a broad definition of sexual health and take positive, affirming, inclusive approaches to human sexuality.”

From the authors:

“We undertook this research because of the glaring lack of work that examines the impact of sex education on all aspects of sexual health, rather than limiting the scope to pregnancy and STI prevention. Our research found that sex education has the potential do so much more. The impact of quality sex education that addresses the broad range of sexual health topics extends beyond pregnancy and STIs and can improve school success, mental health, and safety. As with all other areas of the curriculum, building an early foundation and scaffolding learning with developmentally appropriate content and teaching are key to long-term development of knowledge, attitudes, and skills that support healthy sexuality.

Further, if students are able to avoid early pregnancy, STIs, sexual abuse and interpersonal violence and harassment, while feeling safe and supported within their school environment, they are more likely to experience academic success, a foundation for future stability.”

The paper found that sex education efforts can also succeed in classrooms outside of the health education curriculum. Given that most schools have limited time allotted to health or sex education, a coordinated and concerted effort to teach and reinforce important sexual health concepts throughout other areas of the curriculum is a promising strategy.

Members of the Future of Sex Education Initiative, a coalition of organizations working to ensure all students in grades K–12 receive comprehensive, quality sex education which developed the National Sex Education Standards, welcomed the research:

Debra Hauser, President, Advocates for Youth:

“This paper confirms what educators and young people see every day in classrooms and school communities: sex education helps young people have healthier, safer lives and more affirming environments. We owe it to every young person to make sure they not only have the information and skills they need to protect their health, but that they are safe in their schools and their homes.”

Chris Harley, President & CEO, SIECUS:

“At SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change, we have been asserting that individual and social benefits of sex education extend far beyond simply decreasing rates of unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections among young people. This new wealth of research is just the start of illuminating that the power and importance of comprehensive, inclusive sex education is in it’s ability to do so much more. The findings are clear: sex education helps all of our young people lead happier, healthier, safer lives—no matter who they are or how they identify. ”

Dan Rice, Executive Director, Answer:

“When it comes to most topics taught in school, the motto is often “ Knowledge is Power ;” but there’s often a double standard when it comes to sex education. This paper provides the evidence that access to comprehensive sex education is not only empowering to all students, but can also help to improve their emotional and social development.”

Eva S. Goldfarb, Ph.D. , and Lisa D. Lieberman, Ph.D. are available for comment; please reach out to [email protected] .

10.26.2020 Previous Post

Statement from Debra Hauser on confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett

Next Post 11.04.2020

Statement on Election Results and Ongoing Count

Sign up for updates, sign up for updates.

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- HIV and AIDS

- Hypertension

- Mental disorders

- Top 10 causes of death

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- Data collection tools

- Global Health Observatory

- Insights and visualizations

- COVID excess deaths

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Questions and answers /

Comprehensive sexuality education

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) gives young people accurate, age-appropriate information about sexuality and their sexual and reproductive health, which is critical for their health and survival.

While CSE programmes will be different everywhere, the United Nations’ technical guidance – which was developed together by UNESCO, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women, UNAIDS and WHO – recommends that these programmes should be based on an established curriculum; scientifically accurate; tailored for different ages; and comprehensive, meaning they cover a range of topics on sexuality and sexual and reproductive health, throughout childhood and adolescence.

Topics covered by CSE, which can also be called life skills, family life education and a variety of other names, include, but are not limited to, families and relationships; respect, consent and bodily autonomy; anatomy, puberty and menstruation; contraception and pregnancy; and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

Sexuality education equips children and young people with the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that help them to protect their health, develop respectful social and sexual relationships, make responsible choices and understand and protect the rights of others.

Evidence consistently shows that high-quality sexuality education delivers positive health outcomes, with lifelong impacts. Young people are more likely to delay the onset of sexual activity – and when they do have sex, to practice safer sex – when they are better informed about their sexuality, sexual health and their rights.

Sexuality education also helps them prepare for and manage physical and emotional changes as they grow up, including during puberty and adolescence, while teaching them about respect, consent and where to go if they need help. This in turn reduces risks from violence, exploitation and abuse.

Children and adolescents have the right to be educated about themselves and the world around them in an age- and developmentally appropriate manner – and they need this learning for their health and well-being.

Intended to support school-based curricula, the UN’s global guidance indicates starting CSE at the age of 5 when formal education typically begins. However, sexuality education is a lifelong process, sometimes beginning earlier, at home, with trusted caregivers. Learning is incremental; what is taught at the earliest ages is very different from what is taught during puberty and adolescence.

With younger learners, teaching about sexuality does not necessarily mean teaching about sex. For instance, for younger age groups, CSE may help children learn about their bodies and to recognize their feelings and emotions, while discussing family life and different types of relationships, decision-making, the basic principles of consent and what to do if violence, bullying or abuse occur. This type of learning establishes the foundation for healthy relationships throughout life.

Many people have a role to play in teaching young people about their sexuality and sexual and reproductive health, whether in formal education, at home or in other informal settings. Ideally, sound and consistent education on these topics should be provided from multiple sources. This includes parents and family members but also teachers, who can help ensure young people have access to scientific, accurate information and support them in building critical skills. In addition, sexuality education can be provided outside of school, such as through trained social workers and counsellors who work with young people.

Well-designed and well-delivered sexuality education programmes support positive decision-making around sexual health. Evidence shows that young people are more likely to initiate sexual activity later – and when they do have sex, to practice safer sex – when they are better informed about sexuality, sexual relations and their rights.

CSE does not promote masturbation. However, in our documents, WHO recognizes that children start to explore their bodies through sight and touch at a relatively early age. This is an observation, not a recommendation.

The UN’s guidance on sexuality education aims to help countries, practitioners and families provide accurate, up-to-date information related to young people’s sexuality, which is appropriate to their stage of development. This may include correcting misperceptions relating to masturbation such as that it is harmful to health, and – without shaming children – teaching them about their bodies, boundaries and privacy in an age-appropriate way.

There is sound evidence that unequal gender norms begin early in life, with harmful impacts on both males and females. It is estimated that 18%, or almost 1 in 5 girls worldwide, have experienced child sexual abuse.

Research shows, however, that education in small and large groups can contribute to challenging and changing unequal gender norms. Based on this, the UN’s international guidance on sexuality education recommends teaching young people about gender relations, gender equality and inequality, and gender-based violence.

By providing children and young people with adequate knowledge about their rights, and what is and is not acceptable behaviour, sexuality education makes them less vulnerable to abuse. The UN’s international guidance calls for children between the age of 5 and 8 years to recognize bullying and violence, and understand that these are wrong. It calls for children aged 12–15 years to be made aware that sexual abuse, sexual assault, intimate partner violence and bullying are a violation of human rights and are never the victim’s fault. Finally, it calls for older adolescents – those aged 15–18 – to be taught that consent is critical for a positive sexual relationship with a partner. Children and young people should also be taught what to do and where to go if problems like violence and abuse occur.

Through such an approach, sexuality education improves children’s and young people’s ability to react to abuse, to stop abuse and, finally, to find help when they need it.

There is clear evidence that abstinence-only programmes – which instruct young people to not have sex outside of marriage – are ineffective in preventing early sexual activity and risk-taking behaviour, and potentially harmful to young people’s sexual and reproductive health.

CSE therefore addresses safer sex, preparing young people – after careful decision-making – for intimate relationships that may include sexual intercourse or other sexual activity. Evidence shows that such an approach is associated with later onset of sexual activity, reduced practice of risky sexual behaviours (which also helps reduce the incidence of sexually transmitted infections), and increased contraception use.

On sexuality education, as with all other issues, WHO provides guidance for policies and programmes based on extensive research evidence and programmatic experience.

The UN global guidance on sexuality education outlines a set of learning objectives beginning at the age of 5. These are intended to be adapted to a country’s local context and curriculum. The document itself details how this process of adaptation should occur, including through consultation with experts, parents and young people, alongside research to ensure programmes meet young people’s needs.

Comprehensive sexuality education: For healthy, informed and empowered learners

Did you know that only 37% of young people in sub-Saharan Africa can demonstrate comprehensive knowledge about HIV prevention and transmission? And two out of three girls in many countries lack the knowledge they need as they enter puberty and begin menstruating? Early marriage and early and unintended pregnancy are global concerns for girls’ health and education: in East and Southern Africa pregnancy rates range 15-25%, some of the highest in the world. These are some of the reasons why quality comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is essential for learners’ health, knowledge and empowerment.

What is comprehensive sexuality education or CSE?

Comprehensive sexuality education - or the many other ways this may be referred to - is a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality. It aims to equip children and young people with knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that empowers them to realize their health, well-being and dignity; develop respectful social and sexual relationships; consider how their choices affect their own well-being and that of others; and understand and ensure the protection of their rights throughout their lives.

CSE presents sexuality with a positive approach, emphasizing values such as respect, inclusion, non-discrimination, equality, empathy, responsibility and reciprocity. It reinforces healthy and positive values about bodies, puberty, relationships, sex and family life.

How can CSE transform young people’s lives?

Too many young people receive confusing and conflicting information about puberty, relationships, love and sex, as they make the transition from childhood to adulthood. A growing number of studies show that young people are turning to the digital environment as a key source of information about sexuality.

Applying a learner-centered approach, CSE is adapted to the age and developmental stage of the learner. Learners in lower grades are introduced to simple concepts such as family, respect and kindness, while older learners get to tackle more complex concepts such as gender-based violence, sexual consent, HIV testing, and pregnancy.

When delivered well and combined with access to necessary sexual and reproductive health services, CSE empowers young people to make informed decisions about relationships and sexuality and navigate a world where gender-based violence, gender inequality, early and unintended pregnancies, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections still pose serious risks to their health and well-being. It also helps to keep children safe from abuse by teaching them about their bodies and how to change practices that lead girls to become pregnant before they are ready.

Equally, a lack of high-quality, age-appropriate sexuality and relationship education may leave children and young people vulnerable to harmful sexual behaviours and sexual exploitation.

What does the evidence say about CSE?

The evidence on the impact of CSE is clear:

- Sexuality education has positive effects, including increasing young people’s knowledge and improving their attitudes related to sexual and reproductive health and behaviors.

- Sexuality education leads to learners delaying the age of sexual initiation, increasing the use of condoms and other contraceptives when they are sexually active, increasing their knowledge about their bodies and relationships, decreasing their risk-taking, and decreasing the frequency of unprotected sex.

- Programmes that promote abstinence as the only option have been found to be ineffective in delaying sexual initiation, reducing the frequency of sex or reducing the number of sexual partners. To achieve positive change and reduce early or unintended pregnancies, education about sexuality, reproductive health and contraception must be wide-ranging.

- CSE is five times more likely to be successful in preventing unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections when it pays explicit attention to the topics of gender and power

- Parents and family members are a primary source of information, values formation, care and support for children. Sexuality education has the most impact when school-based programmes are complemented with the involvement of parents and teachers, training institutes and youth-friendly services .

How does UNESCO work to advance learners' health and education?

Countries have increasingly acknowledged the importance of equipping young people with the knowledge, skills and attitudes to develop and sustain positive, healthy relationships and protect themselves from unsafe situations.

UNESCO believes that with CSE, young people learn to treat each other with respect and dignity from an early age and gain skills for better decision making, communications, and critical analysis. They learn they can talk to an adult they trust when they are confused about their bodies, relationships and values. They learn to think about what is right and safe for them and how to avoid coercion, sexually transmitted infections including HIV, and early and unintended pregnancy, and where to go for help. They learn to identify what violence against children and women looks like, including sexual violence, and to understand injustice based on gender. They learn to uphold universal values of equality, love and kindness.

In its International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education , UNESCO and other UN partners have laid out pathways for quality CSE to promote health and well-being, respect for human rights and gender equality, and empower children and young people to lead healthy, safe and productive lives. An online toolkit was developed by UNESCO to facilitate the design and implementation of CSE programmes at national level, as well as at local and school level. A tool for the review and assessment of national sexuality education programmes is also available. Governments, development partners or civil society organizations will find this useful. Guidance for delivering CSE in out-of-school settings is also available.

Through its flagship programme, Our rights, Our lives, Our future (O3) , UNESCO has reached over 30 million learners in 33 countries across sub-Saharan Africa with life skills and sexuality education, in safer learning environments. O3 Plus is now also reaching and supporting learners in higher education institutions.

To strengthen coordination among the UN community, development partners and civil society, UNESCO is co-convening the Global partnership forum on CSE together with UNFPA. With over 65 organizations in its fold, the partnership forum provides a structured platform for intensified collaboration, exchange of information and good practices, research, youth advocacy and leadership, and evidence-based policies and programmes.

Good quality CSE delivery demands up to date research and evidence to inform policy and implementation . UNESCO regularly conducts reviews of national policies and programmes – a report found that while 85% of countries have policies that are supportive of sexuality education, significant gaps remain between policy and curricula reviewed. Research on the quality of sexuality education has also been undertaken, including on CSE and persons with disabilities in Asia and East and Southern Africa .

How are young people and CSE faring in the digital space?

More young people than ever before are turning to digital spaces for information on bodies, relationships and sexuality, interested in the privacy and anonymity the online world can offer. UNESCO found that, in a year, 71% of youth aged 15-24 sought sexuality education and information online.

With the rapid expansion in digital information and education, the sexuality education landscape is changing . Children and young people are increasingly exposed to a broad range of content online some of which may be incomplete, poorly informed or harmful.

UNESCO and its Institute of Information Technologies in Education (IITE) work with young people and content creators to develop digital sexuality education tools that are of good quality, relevant and include appropriate content. More research and investment are needed to understand the effectiveness and impact of digital sexuality education, and how it can complement curriculum-based initiatives. Part of the solution is enabling young people themselves to take the lead on this, as they are no longer passive consumers and are thinking in sophisticated ways about digital technology.

A foundation for life and love

- Safe, seen and included: report on school-based sexuality education

- International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education

- Safe, seen and included: inclusion and diversity within sexuality education; briefing note

- Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) country profiles

- Evidence gaps and research needs in comprehensive sexuality education: technical brief

- The journey towards comprehensive sexuality education: global status report

- Definition of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) thematic indicator 4.7.2: Percentage of schools that provided life skills-based HIV and sexuality education within the previous academic year

- From ideas to action: addressing barriers to comprehensive sexuality education in the classroom

- Facing the facts: the case for comprehensive sexuality education

- UNESCO strategy on education for health and well-being

- UNESCO Health and education resource centre

- Campaign: A foundation for life and love

- UNESCO’s work on health and education

Related items

- Health education

- Sex education

Advertisement

Comprehensive Sex Education Addressing Gender and Power: A Systematic Review to Investigate Implementation and Mechanisms of Impact

- Open access

- Published: 16 December 2021

- Volume 20 , pages 58–74, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Kerstin Sell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2481-7237 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Kathryn Oliver 3 &

- Rebecca Meiksin 3

15k Accesses

5 Citations

36 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Delivered globally to promote adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health, comprehensive sex education (CSE) is rights-based, holistic, and seeks to enhance young people’s skills to foster respectful and healthy relationships. Previous research has demonstrated that CSE programmes that incorporate critical content on gender and power in relationships are more effective in achieving positive sexual and reproductive health outcomes than programmes without this content. However, it is not well understood how these programmes ultimately affect behavioural and biological outcomes. We therefore sought to investigate underlying mechanisms of impact and factors affecting implementation and undertook a systematic review of process evaluation studies reporting on school-based sex education programmes with a gender and power component.

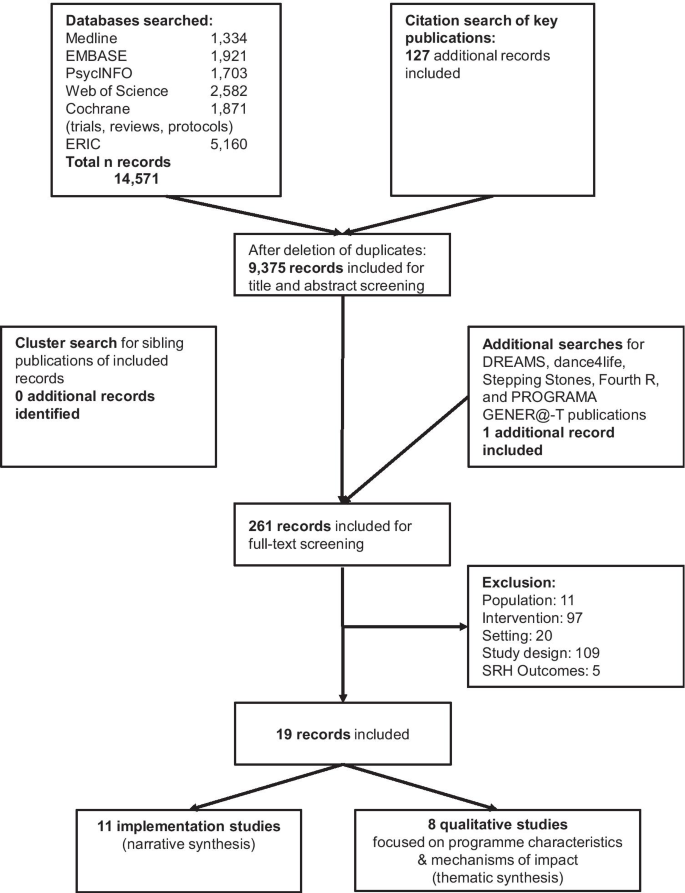

We searched six scientific databases in June 2019 and screened 9375 titles and abstracts and 261 full-text articles. Two distinct analyses and syntheses were conducted: a narrative review of implementation studies and a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies that examined programme characteristics and mechanisms of impact.

Nineteen articles met the inclusion criteria of which eleven were implementation studies. These studies highlighted the critical role of the skill and training of the facilitator, flexibility to adapt programmes to students’ needs, and a supportive school/community environment in which to deliver CSE to aid successful implementation. In the second set of studies ( n = 8), student participation, student-facilitator relationship-building, and open discussions integrating student reflection and experience-sharing with critical content on gender and power were identified as important programme characteristics. These were linked to empowerment, transformation of gender norms, and meaningful contextualisation of students’ experiences as underlying mechanisms of impact.

Conclusion and policy implications

Our findings emphasise the need for CSE programming addressing gender and power that engages students in a meaningful, relatable manner. Our findings can inform theories of change and intervention development for such programmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Gender-transformative school-based sexual health intervention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial

Factors influencing the integration of comprehensive sexuality education into educational systems in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review

Trends and Challenges in Comprehensive Sex Education (CSE) Research in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Narrative Review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

School-based comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) constitutes a public health intervention, promoted globally, to improve young people’s sexual and reproductive health and well-being. CSE, described by UNESCO as ‘a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality’ (UNESCO, 2018a , p. 16), seeks to equip children and young people with a set of skills, attitudes, and scientifically accurate knowledge to nourish respectful social and sexual relationships (UNESCO, 2018a ). It commonly incorporates a positive notion of sexuality, a holistic understanding of sexual health, and emphasises the sexual rights of young people as a human right (Berglas, 2016 ; Haberland & Rogow, 2015 ; UNFPA, 2015 ). CSE is therefore increasingly considered best practice in sexuality education (Vanwesenbeeck, 2020 ). Footnote 1

CSE is recognised to impact positively on a range of adolescent sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes, including but not limited to the following: knowledge of SRH and human rights, communication skills, sexual and emotional well-being, and attitudes supporting gender equity (Goldfarb & Lieberman, 2021 ; Ketting et al., 2016 ; UNFPA, 2015 ). Systematic reviews have demonstrated that CSE programmes also tend to have positive impacts on knowledge, attitudes, and skills although they often demonstrate weak or inconsistent effects on behavioural outcomes such as sexual risk-taking, number of partners, age at initiation of sex, and condom use (Denford et al., 2017 ; Kirby, Laris, & Rolleri, 2007 ; UNESCO, 2018b ).

CSE is also considered an important tool in efforts to promote gender equality, reduce gender-based violence (GBV) (Miller, 2018 ; UNESCO, 2018a ), including intimate partner violence (Kantor et al., 2021 ; Makleff et al., 2019 ), and in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (Starrs et al., 2018 ). These efforts are rooted in an understanding that gender inequality, gender norms, and SRH are closely intertwined, with gender inequality and restrictive gender norms contributing substantially to adverse health outcomes, including in the area of SRH (Heise et al., 2019 ). Conceptualising gender as a hierarchical social system differentiating between women and men and commonly ascribing higher power, resources, and status to men and things masculine, Heise et al. argue that gender norms uphold this social system via unwritten rules that define acceptable behaviour for women, men, and gender minorities (Heise et al., 2019 ). These norms act as a powerful determinant of adolescent SRH (Pulerwitz et al., 2019 ). Gender inequality places girls and women at higher risk of gender-based violence, STIs, biological, social and behavioural vulnerability to HIV, and unintended pregnancy (Dellar et al., 2015 ; Heise et al., 2019 ; Park et al., 2018 ; Wingood & DiClemente, 2000 ). Traditional gender norms place adolescents at higher risk of unsafe sex as it affects their ability to negotiate safe sex (Wood et al., 2015 ), whilst masculinity norms can drive risky sexual behaviour in men, including avoiding condom use and contraception (Heise et al., 2019 ).

As adolescence is considered a key developmental phase during which gender norms and attitudes intensify, this period presents a window of opportunity for intervention (Amin et al., 2018 ; Buller & Schulte, 2018 ; Kågesten et al., 2016 ). Therefore, schools and school-based CSE have been argued to constitute key sites to promote healthier gender norms and gender equality at scale (Jamal et al., 2015 ). Whilst the focus of our work is on adolescents, it is increasingly recognised that school-based interventions geared towards younger children and continued through the school trajectory may be very effective in addressing gender norms and roles (Goldfarb & Lieberman, 2021 ).

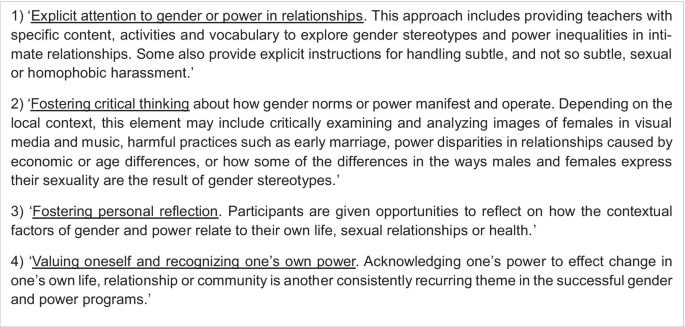

A systematic review of randomised controlled trials of sexuality education programmes that were not abstinence-only and focused on the prevention of HIV, other STIs, and unintended pregnancies as primary outcomes showed that interventions were more likely to have a positive effect on these three biological outcomes if they explicitly addressed ‘gender and power’ in relationships as compared to interventions that did not include this component Footnote 2 (Haberland, 2015 ). In the review, the gender and power content constituted ‘at least one explicit lesson, topic or activity covering an aspect of gender or power in sexual relationships, for example, how harmful notions of masculinity and femininity affect behaviors, are perpetuated and can be transformed; rights and coercion; gender inequality in society; unequal power in intimate relationships; fostering young women’s empowerment; or gender and power dynamics of condom use’ (Haberland, 2015 , p. 3). In addition to demonstrating the effectiveness of the programmes with gender and power content, Haberland identified four common characteristics of effective programmes: ‘Fostering critical thinking’, ‘explicit attention to gender or power in relationships’, ‘fostering personal reflection’, and ‘valuing oneself and recognising one’s own power’ (ibid, pages 6–7).

As a result of the work of Haberland and others, explicit attention to gender and gender-related power has been incorporated into many CSE programmes, e.g. by incorporating gender norms and power dynamics into the theory of change in CSE programmes (Berglas, 2016 ). Such ‘gender-transformative’ programming considers the roots of gender-based health inequities, incorporates strategies to address these, and ultimately seeks to shift gender relations and norms that contribute to these inequities (Ruane-McAteer et al., 2019 ; World Health Organization, 2011 ). However, whilst there is both a strong rationale and great emphasis on incorporating gender and power content in CSE (UNESCO, 2018a ) and evaluating gender- and power-related outcomes (Haberland & Rogow, 2015 ; UNFPA, 2015 ), these programmes’ pathways of change remain under-researched (Ketting et al., 2016 ; Kippax & Stephenson, 2005 ; Ruane-McAteer et al., 2019 ). In complex public health interventions such as CSE, gender and power components are likely to interact with context and impact on intervention effects in a non-linear manner (Petticrew et al., 2013 ; Rutter et al., 2017 ). Evaluation studies exploring these processes can therefore contribute to understanding how interventions work by elucidating mechanisms of impact, effective implementation strategies, and contextual factors shaping programme outcomes (MRC, 2015 ).

Building on Haberland’s work, we undertook a systematic review of process evaluations of school-based CSE and other sex education programmes with gender and power components targeting adolescents. By sex education, we mean interventions which seek to promote healthy sexual and relationship behaviours, excluding abstinence-only interventions. We sought to gain an in-depth understanding of how inclusion of gender and power content shapes programme implementation and outcomes with the ultimate goal of informing CSE programming by delineating effective implementation strategies and programme characteristics, as well as mechanisms of impact. We synthesised evidence on (i) implementation, (ii) programme characteristics, and (iii) mechanisms of impact.

Search Strategy

Searches for this review were conducted in six scientific databases: Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, ERIC, and the Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews. The search strategy was developed iteratively based on repeated scoping searches and employed the following four concepts: programmes and interventions; sexuality education/schools; gender; power and rights (full search strategy available in online supplementary material ). Synonyms and proximity operators were used to enable identification of studies that were not explicitly labelled as addressing gender and power or as evaluation studies. Additionally, we screened articles referencing the seminal Haberland review ( 2015 ) and its sibling publication (Haberland & Rogow, 2015 ).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied for screening:

Publication date : Studies published from 2013 onwards, as this was the cut-off date for the searches of the seminal review that informed our work.

Population: Adolescents aged 10 to 18.

Intervention: Employing a broad definition of sexuality education, studies were included when reporting on CSE or other programmes with sex education content that included a relevant ‘gender and power’ component according to three criteria: Programmes (a) were labelled as gender-transformative programmes, (b) addressed the social construction of gender, and/or (c) highlighted problems related to gender inequality as structural and not as individual problems.

Setting: Interventions based in schools. Activities set in middle or high schools or reporting on a school curriculum, including after-school programmes.

Study design : Process evaluations and other primary studies that reported data on implementation, context, or mechanisms of impact but were not labelled process evaluations. Thus, we included all kinds of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods empirical studies reporting on process.

Programme outcomes : Studies on interventions that were designed to improve biological outcomes (e.g. reduction in unwanted pregnancy, reduction of STIs and HIV), behavioural outcomes (e.g. condom use, age at sexual debut, number of sexual partners, self-efficacy), social outcomes (e.g. equitable attitudes and norms with respect to gender, gender and sexual diversity; communication skills and emotional skills), or knowledge-related outcomes related to SRH were included. This included GBV-related outcomes (e.g. bystander intentions and behaviour, GBV victimisation and perpetration).

Previous work identified ‘gender and power’ content as an important working component in sex education (Haberland, 2015 ). Thus, even if our ultimate aim was to inform CSE programming, we included studies about sex education programmes that were not explicitly labelled as ‘CSE’, as well as other school-based interventions, as long as they included gender and power content meeting the above definition. As it has been demonstrated that a wider range of interventions in the school environment may affect (sexual) health (Shackleton et al., 2016 ), we expected to improve our understanding of the wider social context of the intervention by including a broader set of studies.

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

Publication date : Studies published before 2013 were excluded.

Population: Studies reporting primarily on children in primary school, young adults, and adults were excluded.

Intervention: Studies were excluded when they reported on interventions which did not seek to challenge traditional gender roles and norms and when they demonstrated an understanding of gender as a biological determinant or as a marker of sexual reproductive categories, as opposed to a social construct amenable to change.

Setting: Interventions based outside of schools such as community-based interventions without a school component were excluded.

Study design : Non-peer-reviewed reports, editorials, conference abstracts, study protocols, baseline surveys, opinion papers, dissertations, book chapters, and reviews were excluded. Outcome evaluations were initially included but a decision to exclude these studies was made post hoc in order to focus the scope of this review.

Programme outcomes : Studies reporting on interventions that were targeting educational attainment outcomes or socio-emotional skills only were excluded.

Screening Process

The systematic review software EPPI-reviewer was used for screening (University College London, 2017 ). After piloting and refinement of the screening criteria including double screening of a subset of studies, the first author conducted title and abstract and then full text screening. Items coded as ambiguous were discussed with a second author to reach a consensus.

A cluster-search was performed for evaluation studies of five programmes that were referred to multiple times in screened full-texts but were not represented among included records. Additionally, reference lists of articles included in our review were cluster-searched for sibling publications reporting on the same programmes and a Google and Google Scholar search for the programmes and lead authors of all included articles was performed to identify further relevant process-focused articles (Booth et al., 2013 ).

Assessment of Study Quality

For assessment of study quality, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative research was used (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018 ). It comprises 10 questions that prompt the user to consider potential for bias, along with methodological and ethical issues. We derived scores from these questions to indicate study quality, with a 10 out of 10 indicating high quality. As we were primarily interested in qualitative results, mixed-methods implementation studies were assessed with the CASP checklist for qualitative research as well.

Data Extraction

Data from included studies was extracted into a Microsoft Excel–based data extraction sheet. Study and intervention details, qualitative outcomes, and large sections of text covering process-related aspects (mechanisms of change, context, and implementation (MRC, 2015 )) were extracted comprehensively. Data on process was extracted from the introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections of included studies and it was noted which of these sections the respective data originated from.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

Based on the respective research question asked, the study design, and methods, the included studies were categorised into two mutually exclusive types. One group of studies examined programme implementation, employing quantitative and/or qualitative methods. These studies were reporting data explicitly about intervention implementation, which was defined as ‘the structures, resources and processes through which delivery is achieved, and the quantity and quality of what is delivered’ (MRC, 2015 , p. 10), including contextual factors (Pfadenhauer et al., 2017 ). The second set of studies investigated the impacts on social and behavioural outcomes and underlying processes, employing qualitative methods. These studies had a focus on exploring the links between programme outcomes, programme characteristics, and/or mechanisms of impact. We subsequently refer to the first group of studies as ‘implementation studies’ and to the second group of studies as ‘studies exploring mechanisms of impact’. We conducted two distinct syntheses, one of each of these study types.

Synthesis 1: Data Analysis and Narrative Synthesis of Implementation Studies

The synthesis of implementation studies was informed by the Context and Implementation of Complex interventions (CICI) framework (Pfadenhauer et al., 2017 ). Categories within this framework comprise the implementation agents (individuals concerned with running or receiving an intervention), implementation process, implementation strategies, and context (Pfadenhauer et al., 2017 ). Results from implementation studies were organised into the distinct implementation categories and summarised narratively.

Synthesis 2: Data Analysis and Thematic Synthesis of Studies Exploring Mechanisms of Impact

We conducted a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies exploring programme outcomes, characteristics, and mechanisms of impact (Thomas & Harden, 2008 ). We conceptualised mechanisms of impact as the link between intervention activities and outcomes including ‘[p]articipant responses to, and interactions with, the intervention’ as well as mediators (MRC, 2015 , p. 24).

Data analysis was undertaken at the level of the extracted data: the sections of the data extraction sheet containing data on qualitative outcomes and process from the results and discussion sections of included qualitative studies were analysed thematically. Data excerpts served as the unit of analysis for coding. Codes were developed inductively and subsequently compared across studies and grouped and regrouped together in an iterative process to develop themes, resulting in the development of an initial mindmap. This process was informed by key findings from the preceding synthesis of implementation studies and by the four programme characteristics previously identified by Haberland ( 2015 , textbox 1 ), which shaped our initial understanding of relevant programme aspects of sex education with gender and power content.

Programme Characteristics of Effective Sex Education Programmes Addressing Gender and Power as Identified and Defined By Haberland ( 2015 )

These four previously identified characteristics were compared, contrasted, and linked with the newly developed themes to facilitate differentiation of the new themes as programme characteristics or potential mechanisms of impact. The themes and respective links are visualised in Fig. 2 .

Where we encountered data that was not sufficiently rich to describe mechanisms of impact, we made inferences about potential mechanisms, which are identified as hypothesised mechanisms in the results section.

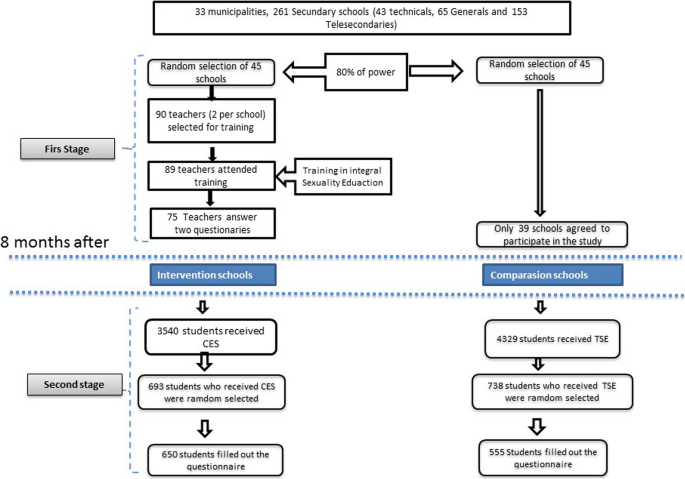

Searches were run on June 22–23, 2019. Database searches yielded 14,571 records and citation searches yielded 127 records, resulting in a total of 14,698 records (Fig. 1 ). After deletion of duplicates, 9375 records were screened on title and abstract and one additional record was added via intervention-specific searches, yielding 261 records which were screened on full-text. Nineteen reports on 18 studies were included in this review, with two implementation reports addressing the same study.

PRISMA flowchart

Characteristics of Included Studies and Programmes

Eleven studies were process evaluations that focused on programme implementation and employed qualitative or mixed methods. Eight studies were qualitative studies exploring qualitative intervention outcomes, programme characteristics, and mechanisms of impact. Only four of these eight studies were explicitly referred to as evaluation studies. For the majority of included studies ( n = 17), there was very little concern with study quality (Table 1 ).

The 19 included primary studies were conducted in 15 countries (Table 1 ). Most evidence was from Europe ( n = 6 countries, 3 studies) and Africa ( n = 6 studies from six countries), followed by North America ( n = 4 studies) and Australia ( n = 4). Most articles reported evaluations of locally implemented programmes targeting boys and girls.

Only five programmes were labelled by the authors as CSE or holistic sex education programmes (Boonmongkon et al., 2019 ; Browes, 2015 ; Chandra-Mouli et al., 2018 ; Rijsdijk et al., 2014 ; Wood et al., 2015 ). Other programmes exhibited key CSE characteristics but were not labelled as such: five articles reported on school-based interventions labelled violence prevention programmes (including dating, domestic, and gender-based violence) (Jaime et al., 2016 ; Joyce et al., 2019 ; Kearney et al., 2016 ; Ollis, 2017 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ). Four programmes were explicitly called gender-transformative (Jaime et al., 2016 ; Sánchez-Hernández et al.,, 2018 ) or ‘healthy’ or ‘positive masculinities’ programmes (Claussen, 2019 ; Namy et al., 2015 ). Three programmes were sports- or PE-based (Jaime et al., 2016 ; Merrill et al., 2018 ; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ) and three were focused on critical media literacy or critical thinking related to gender (Berman & White, 2013 ; Jacobs, 2016 ; Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ). In three of these programmes, the gender and power content constituted the only sex education component of the programme (Berman & White, 2013 ; Jacobs, 2016 ; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ).

Programmers incorporated creative, non-conventional, and innovative teaching methods: participatory methods like role-plays and discussions were utilised in most included studies. Further methods included the following: artwork, dance, drama, film and media production (Berman & White, 2013 ; Jacobs, 2016 ; Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ; Namy et al., 2015 ). Beyond classroom-based intervention components, six studies included activities at the school (Joyce et al., 2019 ; Kearney et al., 2016 ; Namy et al., 2015 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ) and/or community level (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2018 ; Robertson-James et al., 2017 ).

The gender and power content was delivered across a range of different school subjects, i.e. social studies, PE, home economics, health, science, language, and religious education classes (Boonmongkon et al., 2019 ; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ; Wood et al., 2015 ). In addition to teacher or facilitator-led programmes, some included peer mentors and student-led initiatives outside of the classroom (Berman & White, 2013 ; Namy et al., 2015 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ).

Gender and Power Content

Gender and power content was covered at different degrees of depth in included interventions. Whilst addressing gender stereotypes was a common curricular topic, notably fewer interventions included in-depth discussions of gendered relationship power: two addressed the links between gender inequality, relationship power, and GBV (Ollis, 2017 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ). In addition to discussing gendered power, some programmes included the exploration of other dimensions of power, such as power relationships between students and teachers (Claussen, 2019 ), power in the family context (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2018 ), power in an intersectional framework (Jacobs, 2016 ), and how gender-related power is apparent in the media (Jacobs, 2016 ; Ollis, 2017 ). In most programmes, gender and power content was linked with exercises to encourage personal reflection and critical discussions.

Synthesis 1: Narrative Synthesis of Implementation Studies

Included implementation studies stressed the critical role of the implementation agent and their skill set in delivering sex education. Programmes reported in the implementation studies were delivered by teachers (Boonmongkon et al., 2019 ; Browes, 2015 ; Rijsdijk et al., 2014 ; Wood et al., 2015 ), sports coaches (Jaime et al., 2016 ; Merrill et al., 2018 ), and external facilitators (Claussen, 2019 ). Whole-school approaches were further supported by an external project implementer (Joyce et al., 2019 ; Kearney et al., 2016 ; Robertson-James et al., 2017 ). Whilst reports suggest that teacher-delivered CSE was implemented as intended when teachers participated in high-quality training focused on gender and human rights (Wood et al., 2015 ), teachers who were unprepared to deliver CSE were found to omit relevant programme topics and frame adolescent sexuality as a risk or problem (Boonmongkon et al., 2019 ), reflecting teachers’ values (Browes, 2015 ; Rijsdijk et al., 2014 ). Teacher training for CSE was thus recommended to address both teachers’ knowledge and teachers’ gender attitudes (Browes, 2015 ; Wood et al., 2015 ).

Implementation support from an external change agent was described as instrumental in mainstreaming programme content beyond the classroom, e.g. by addressing gender in school policies, providing gender training to teachers, and undertaking a gender-focused audit and staff surveys (Joyce et al., 2019 ; Kearney et al., 2016 ; Robertson-James et al., 2017 ). The latter were fed back to schools as part of the intervention in one study, thus serving as feedback loops enhancing an overall change process (Kearney et al., 2016 ).

Implementation strategies : In programmes delivered by sports coaches and other external facilitators, non-hierarchical participatory teaching strategies promoted student engagement with intervention content and supported implementation. Engagement was reportedly fostered by creating a safe space and building student-facilitator relationships, with facilitators acting in a non-authoritative, non-judgemental, approachable manner and sharing personal experiences whilst addressing real-life issues (Claussen, 2019 ; Jaime et al., 2016 ; Merrill et al., 2018 ). Programmes facilitated by these ‘adult allies’ (Jaime et al., 2016 ) were often delivered in same-sex groups by same-sex facilitators acting as role-models that encouraged student engagement (Claussen, 2019 ; Jaime et al., 2016 ; Merrill et al., 2018 ). Other implementation strategies included a strong focus on interaction, reflection, and discussion (Claussen, 2019 ; Jaime et al., 2016 ; Merrill et al., 2018 ; Wood et al., 2015 ) and allowing for curricular flexibility to adapt programmes to students’ needs and knowledge (Claussen, 2019 ; Rijsdijk et al., 2014 ). One report suggested that the ‘dose delivered’ in process evaluations of these programmes should consider the degree of student engagement and their relating of programme content to their experiences (Jaime et al., 2016 ).

In terms of implementation context , included studies suggest that CSE programming is likely to be met with contradictory messages from schools, families, and communities (Browes, 2015 ) and sometimes with resistance from diverse actors in these settings (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2018 ), especially in conservative contexts, which could impact on programme implementation. While this may restrain programme effectiveness or may lead to programme adaptations (Browes, 2015 ; Chandra-Mouli et al., 2018 ; Wood et al., 2015 ), studies suggested that the implementation process can be tailored to build support for these programmes: successful approaches included framing the programmes around healthy skills instead of sexuality (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2018 ; Wood et al., 2015 ), getting stakeholder and community buy-in during the programme development phase (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2018 ), and building support networks or enhancing pre-existing networks for the programmes in schools and communities (Joyce et al., 2019 ; Kearney et al., 2016 ; Rijsdijk et al., 2014 ; Robertson-James et al., 2017 ), including with other initiatives that promote gender equality, such as non-governmental organisations providing teacher training (Wood et al., 2015 ).

Synthesis 2: Thematic Synthesis of Studies Exploring Mechanisms of Impact

The qualitative studies reporting on programme outcomes, characteristics, and/or mechanisms of impact primarily reported what happened in the classroom during delivery of eligible sex education interventions, focusing on the learning methods employed, the role of facilitators, and students’ reactions to the sessions. The reported outcomes predominantly constituted observations of students’ classroom behaviour and their comments about the programme and content whilst data on programme impact on SRH outcomes beyond the classroom were limited due to the nature of the included studies. However, our findings identify likely mechanisms of impact on SRH outcomes.

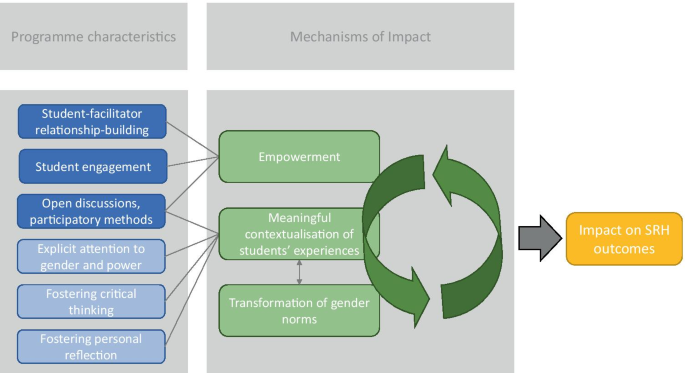

Six themes emerged in our analysis. Three constitute key programme characteristics: (i) student-facilitator relationship-building, (ii) student participation, and (iii) open discussions or ‘dialogues’ integrating student reflection and experience-sharing with critical content on gender and power. Three additional themes represented potential mechanisms of impact: empowerment , meaningful contextualisation of students’ experiences, and transformation of gender norms . Figure 2 depicts the themes and crosslinks, including further relevant programme characteristics identified in a previous review (Haberland, 2015 ).

Overview of programme characteristics (blue boxes) and potential mechanisms of impact (green boxes); light blue boxes represent programme characteristics that were identified in Haberland’s review ( 2015 ); dark blue boxes represent characteristics that were identified in our review

Programme Characteristics

Student-facilitator relationship-building.

Evidence from our thematic synthesis highlighted the importance of the facilitator’s role in building (egalitarian) relationships with students and enabling a teaching atmosphere where open discussions could take place, with codes echoing the factors that facilitated implementation described in the narrative synthesis above, in particular the relevance of safe spaces and facilitators as potential ‘allies’ (Jacobs, 2016 ; Namy et al., 2015 ; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ). Other important facilitator skills included emotional awareness and a ‘strong awareness of the socially constructed nature of gender’ (Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ). Across studies, a trusting atmosphere in the class and a confidential, safe space were highlighted as both a result of facilitators’ efforts to build relationships with students and as a prerequisite to successful programming and to the open discussions that emerged as another key theme (Jacobs, 2016 ; Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ; Namy et al., 2015 ; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ).

Student Participation

Our findings suggest there was a high degree of student participation in included interventions. This included students co-creating the curriculum (Jacobs, 2016 ; Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ) or taking on leadership roles in student initiatives that were linked to the programme, e.g. mentoring of younger students or participation in after-school clubs (Namy et al., 2015 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ). Programmers noted students’ sense of shared responsibility and their ownership of programme messages (Berman & White, 2013 ; Jacobs, 2016 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ), whilst students appreciated the opportunity to practice leadership and transferable skills and benefitted from supportive peer networks (Berman & White, 2013 ; Jacobs, 2016 ; Namy et al., 2015 ; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ).

Open Discussions to Discuss Gender and Power

All programmes but one (Ngabaza et al., 2016 ) were characterised by use of participatory methods, in particular open discussions where gender and power content was discussed critically and where students shared their experiences. The open discussions or ‘dialogues’ (Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ) served as a venue for students to exercise their curiosity and ask questions about sensitive topics, to be heard and share personal stories, to feel that their experience was validated, and to take on others’ perspectives (Jacobs, 2016 ; Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ). In one sports-based programme, ‘boys listening to girls’ enabled participants to recognise gender stereotypes (Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ). Topics invoking emotional responses such as pornography or cheating on a partner were observed as instrumental in fostering students’ critical thinking about gender and power and creating awareness of gender norms and stereotypes (Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ; Ollis, 2017 ). The use of these open discussions thus went along with course content paying ‘explicit attention to gender and power in relationships’ and content ‘fostering critical thinking’, alongside ‘personal reflection’, the programme characteristics Haberland ( 2015 ) had previously described and which informed our analysis. In addition to critical examination of the status quo, some programmes explored alternative discourses to dominant gender narratives (Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ; Namy et al., 2015 ), including from an intersectional perspective (Jacobs, 2016 ).

Themes Representing Potential Mechanisms of Impact

Empowerment.

Empowerment emerged as a theme that was linked to the three programme characteristics described above, all of which contributed to a shift of power in the classroom: Facilitators’ emphasis on building egalitarian relationships with students, student leadership, enhanced peer support, and open discussions where students make their voices heard are empowering and rebalance otherwise hierarchical relations between students and teachers, representing a disruption of ‘traditional power dynamics’ (Jacobs, 2016 ). In three programmes, students who were involved as student mentors or participated in optional programme retreats displayed the strongest ownership of programme messages and experienced the greatest programme effects (Berman & White, 2013 ; Namy et al., 2015 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ), demonstrating the link between enhanced student participation, empowerment, and outcomes. This resonates with the synthesis of implementation studies, which demonstrated that intervention activities taking place outside of the classroom, such as whole-school approaches, and interventions including the wider community, were found to enhance implementation. These interventions may lead to a change of hierarchies and relationships at a broader contextual level and further strengthening of student empowerment.

The empowerment theme corresponds with what Haberland coined ‘valuing oneself and one’s own power’, the acknowledgement of students’ own power as change agents (Haberland, 2015 ). We therefore hypothesise that student empowerment constitutes one mechanism of impact: sex education taught in an egalitarian, participatory manner may empower students to adapt attitudes and norms, enhance self-efficacy, and ultimately influence behaviour and SRH outcomes beyond the classroom.

Meaningful Contextualisation of Students’ Experiences and Transformation of Gender Norms

Across most included studies, open discussions and other participatory methods were utilised by facilitators to connect students’ reports of their own experiences with broader societal topics, including gender and power. Authors report that these participatory methods increased critical thinking and critical awareness of harmful gender norms, gender inequality, and GBV (Berman & White, 2013 ; Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ; Namy et al., 2015 ; Ollis, 2017 ; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ). Enhanced non-violent attitudes, willingness to change (Namy et al., 2015 ), and improved class climate (Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ) were described as further outcomes of the programmes.

In addition to reporting positive outcomes attributed to the participatory methods and critical discussions of gender and power content, authors also reported that the personalisation of programme content resonated strongly with students (Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ; Namy et al., 2015 ; Ollis, 2017 ) and that students identified the questioning of dominant beliefs as a crucial step towards behaviour change (Namy et al., 2015 ).

The open discussions thus served as a forum in which personal reflection and sharing of personal experiences made the sex education content more relevant and relatable for students, while programmes’ explicit focus on gender and power enabled critical examination of the patriarchal societal context of those experiences, especially unequal power in relationships, rigid gender norms, and gender stereotypes. Thus, evidence from our review points towards two interlinking mechanisms of impact: The first is meaningful contextualisation of students’ experiences, which highlights the importance of personalisation of programme messages to support students in developing an understanding of the societal context of their sexual and romantic relationships. This is closely linked with the second mechanism, transformation of gender norms. As Namy et al. ( 2015 ) observed, intervention participants showed an increased appreciation of ‘multiple masculinities’ and demonstrated willingness to change when they recognised personal identification with harmful masculinities. This shows an initial shift in gender norms and illustrates its link with the contextualisation of students’ experiences, as well as empowerment. It further suggests that discussing alternatives to dominant norms may expand the range of possible behaviours beyond traditionally gendered behaviours (Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ), enabling behaviour change that ultimately affects SRH outcomes.

Interaction of Mechanisms of Impact

At the same time, the use of participatory learning methods, in particular open discussions, encouragement of student participation, and egalitarian relationships of students and facilitators lead to a palpable shift in power in hierarchical school environments, complementing students’ theoretical discussions and reflections with a lived and embodied experience of empowerment. Based on this link and other connections between mechanisms as outlined above, we hypothesise that the mechanisms empowerment, meaningful contextualisation of students’ experiences, and transformation of gender norms act synergistically, build upon each other, and influence one another in affecting students’ behaviours and ultimately SRH outcomes (Fig. 2 ).

Unintended Effects

Included studies also highlighted that sex education with gender and power content may leave entrenched norms unchanged, in particular when student exposure to the programme was limited to only a few classroom sessions (Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ; Namy et al., 2015 ), and that teachers at times reinforced gender stereotypes (Ngabaza et al., 2016 ), resonating with similar findings from the implementation studies.

Nineteen studies met the inclusion criteria of this process-focused systematic review of school-based sex education programmes addressing gender and power. The review found that gender and power content was incorporated and operationalised differently in a diverse range of programmes. Implementation studies highlighted the importance of high-quality facilitator training, flexibility to adapt programmes to students’ needs, and building support for sex education programmes among school and local communities. We found that (i) student participation, (ii) student-facilitator relationship-building, and (iii) open discussions integrating student reflection and experience-sharing with critical content on gender and power constituted important programme characteristics that data suggest contribute to programme effectiveness. Evidence from our thematic synthesis suggests that linked to these intervention characteristics meaningful contextualisation of students’ experiences, empowerment, and transformation of gender norms may constitute mechanisms of impact that ultimately affect SRH outcomes.

Results in Context

Focusing on both CSE and other sex education interventions that include critical content on gender and power enabled comparisons across studies to enhance our understanding of how sex education with this component works. To place these results in context, we draw on the broader literature of CSE evaluation and the theoretical literature on sex education theory, empowerment, and critical pedagogy.

- Implementation

Our narrative synthesis of findings from implementation studies largely corresponds with other summaries of aspects that facilitate intervention implementation and engagement with CSE, e.g. regarding the importance of educator training and skill, support from external facilitators, non-hierarchical participatory teaching methods to engage students in intervention activities, and a supportive school and community context (Kirby et al., 2007 ; UNESCO, 2018a ; Vanwesenbeeck, 2020 ). These other reviews have further emphasised the critical role of an enabling school environment and multicomponent approaches for CSE implementation (UNESCO, 2018a ; Vanwesenbeeck, 2020 ).

Whether teachers or external facilitators are best placed to deliver CSE is an area of active debate. For example, in a UK-focused overview of best-practices in sex and relationships education (SRE), students deemed teachers unsuitable to deliver SRE whilst teachers and SRE professionals considered teacher-led SRE to be the most sustainable model long-term (Pound et al., 2017 ). This is reflected in our review where studies involving outside facilitators appeared to be pilot or one-off projects, or required substantial resources (e.g. Jaime et al., 2016 ; Joyce et al., 2019 ; Kearney et al., 2016 ; Williams & Neville, 2017 ). However, our results suggest that programmes were generally more successful in empowering students and engaging them in a meaningful way when implemented by an outside facilitator. Pound et al. argue that one of the challenges of teachers implementing SRE is the breeching of boundaries between teachers and students, which may be less of a problem when outside facilitators are involved (Pound et al., 2016 ). Given that the overall importance of the skill level of the teacher or facilitator for achieving positive programme effects has been strongly emphasised, it remains somewhat unclear to which extent programme ‘success’ can be attributed to the programme content as opposed to the skill level of the implementing agent, in particular with respect to addressing gender and power and facilitating participatory sessions. Whilst this may present an avenue for further research work, it is promising that authors in one implementation study included in our review argued that high-quality teacher training would enable teachers with previously limited CSE teaching skills to implement progressive sex education programmes as intended (Wood et al., 2015 ).

Hypothesised Mechanisms of Impact

In our thematic synthesis, empowerment of students emerged as a likely mechanism of impact on SRH outcomes. This is not unexpected, as empowerment is central to many CSE programmes (UNFPA, 2015 ; Vanwesenbeeck, 2020 ) and constitutes a key strategy in health promotion more generally (Laverack, 2004 ). In sex education, student empowerment is theorised to expand the range of ‘sexual or gendered subject positions’ (Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ), thus enabling health-promoting attitudes, practices, and behaviours, including sexual agency (Fields, 2008 ; Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ). Our findings suggest that fostering student engagement and egalitarian relationships in the classroom, as well as open discussions allowing students to share experiences and feel validated, led to a shift of power in classrooms and contributed to this mechanism. However, empowerment may be easier envisioned than enacted. Jessica Fields argues that even staunch CSE advocates tend to fall short of embracing the transformative and empowering potential of CSE. By resorting to narratives of danger, they eschew positive messaging that builds on students’ existing sexual knowledge, encourages sexual agency, and equips them to deal with the social challenges that are intertwined with sexuality (Fields, 2008 ). This is echoed by other authors who observe that even in the most progressive contexts sex education teachers fail to achieve a shift in power hierarchies that would enable student empowerment (Naezer et al., 2017 ; Sanjakdar, 2019 ). Thus, while our findings suggest student empowerment is a mechanism of impact that may ultimately affect adolescent SRH, this mechanism likely requires a very facilitative context and skilled implementer.

The second potential mechanism of impact we identified was meaningful contextualisation of students’ experiences, facilitated by open discussions that provided a forum for critical thinking on gender and power and personal reflection. Open discussions as interactive learner-centred approaches are emphasised in CSE guidance (UNESCO, 2018a ), desired by students (Pound et al., 2017 ), and theorised to make CSE relevant for the diverse and heterogeneous SRH needs of adolescents (Engel et al., 2019 ). Similarly, our analyses highlight their central role in CSE programming with gender and power content. Beyond ensuring that programmes are relevant for individual students, open discussions that include critical content on gender and power also address the societal dimensions of sex and relationships, enabling meaningful contextualisation of students’ experiences in particular in relation to gender inequality, and harmful gender norms. As Jessica Fields powerfully states, ‘Sex education offers students an opportunity to grasp sexuality’s place in the context of gender, racial and class inequalities […]’ (Fields, 2008 ). Ensuring that programmes are linked to the social environment of participants’ lived realities is understood to make SRH interventions more effective (Wingood & DiClemente, 2000 ).

The power of the interactive discussions led one group of authors in our review to conclude that students needed these open ‘sexuality dialogues’ more than what’s conventionally understood as sexuality education (Jearey-Graham & Macleod, 2017 ). The term ‘dialogues’ originates from critical pedagogy (Sanjakdar et al., 2015 ). In this framework, schools are understood as sites that reinforce existing social systems and power structures—which critical pedagogy seeks to counter (Sanjakdar et al., 2015 ). This approach is a democratic, joint process of knowledge creation that drives on student voice and curiosity, with teachers encouraging questioning and critical thinking via ‘dialogic teaching’ (Sanjakdar, 2019 ; Sanjakdar et al., 2015 ). The critical pedagogy framework thus incorporates the programme characteristics and mechanisms we identified, including the disruption of traditional power dynamics which was linked to our empowerment mechanism. A critical pedagogy approach in CSE may therefore facilitate a better understanding of the operationalisation of these mechanisms in educational systems and improve programme implementation.

Systematic review evidence suggests that gender-transformative programmes seeking to improve diverse SRH outcomes impact behaviour more effectively than programmes without this approach (Barker et al., 2010 ). Interventions addressing gender norms were identified as most promising in addressing a multitude of risk factors to reduce violence against women and girls (VAWG) (Jewkes et al., 2015 ). In our review, whilst transformation of gender norms emerged as a potential mechanism in our thematic analysis, only few included studies reported using an explicit gender transformative approach, defined as approaches including ‘strategies to foster progressive changes in power relationships between women and men’ by WHO ( 2011 ). This reflects findings from a systematic review of reviews on engaging boys and men in SRH programming that reported an overall dearth of gender transformative programmes (Ruane-McAteer et al., 2019 ). Programmes to prevent VAWG and those set in low- and middle-income countries were most likely to be gender transformative compared to programmes targeting other SRH outcomes (Ruane-McAteer et al., 2019 ), suggesting that the potential of a gender transformative approach has not yet been harnessed across the educational programming seeking to improve adolescent SRH. Our findings also highlight a barrier to implementation of gender transformative programming: programme implementation is highly dependent on implementation agents whose values and skills influence implementation and may reproduce gender stereotypes, thus maintaining gender relations (Boonmongkon et al., 2019 ; Browes, 2015 ; Ngabaza et al., 2016 ; Rijsdijk et al., 2014 ).

Strengths and Limitations

This review employed a broad and comprehensive search strategy across six databases and supplemental searches to include a wide range of studies. Inclusion of studies from 15 countries across diverse world regions may support transferability of our findings across contexts. Whilst we were interested in understanding how gender and power content would work in CSE, which is considered best practice in sexuality education, we included other sex education and school-based programmes with relevant gender and power components to broaden our understanding, in particular on potential mechanisms of impact. Since all included studies still contained relevant CSE content, we are confident that our conclusions are applicable for CSE programming. Similarly, we included studies that reported relevant data on the intervention process but were not strictly process evaluations in order to draw on a larger body of evidence. These decisions led to some ambiguity at the screening stage and heterogeneity among included studies but ultimately enhanced the findings in this work, especially the thematic synthesis.

This review also has limitations. Additional cluster-searching, repeated iterative searches, snowballing, inclusion of grey literature (Booth et al., 2013 ), and inclusion of studies published in languages other than English may have identified additional eligible studies but were beyond the scope of this review. Relevant studies may have been excluded based on programme descriptions, which were often limited in screened reports (Ruane-McAteer et al., 2019 ). Nevertheless, included studies reported a wide range of observations and reinforced key findings across studies, suggesting that included studies provide reliable insights to support implementation of CSE programmes with gender and power content among adolescents.

Implications for Policy, Practice, and Research

Whilst our synthesis does not allow for causal inference on mechanisms of impact that describe how school-based CSE interventions with a gender and power component ultimately impact adolescents’ SRH outcomes, the evidence suggesting empowerment, meaningful contextualisation of students’ experiences, and transformation of gender norms as relevant mechanisms correspond with the theoretical literature and existing empirical evidence. These mechanisms are facilitated by student participation, open discussions, and student-facilitator relationship-building and rely on skills of facilitators and a supportive context for effective intervention delivery.

This research can thus contribute to the growing body of literature to inform programme design, adaptation, transferability, and the evaluation of interventions to improve adolescent SRH. The mechanisms identified in this review can inform future research in which they are empirically tested and refined, for example through linked, rigorous outcome and process evaluations investigating the pathways to change of how sex education programme content impacts on the multiplicity of SRH outcomes, which constitutes a gap in the current literature. Furthermore, as it is considered best practice to guide intervention design, implementation, and the evaluation of complex interventions such as CSE by a relevant theory of change (De Silva et al., 2014 ; Moore & Evans, 2017 ), our results can inform the evaluation of ongoing programmes and inform the theory of change of future programmes—which is currently not often made explicit in interventions to improve SRH (Ruane-McAteer et al., 2019 ). Our review identified only one study which incorporated an explicit focus on complexity into the evaluation of school-based CSE (Joyce et al., 2019 ; Kearney et al., 2016 ). Their results suggest that feedback loops and the evaluation itself may have an important effect on programme implementation and outcomes and should be considered in future intervention planning and theories of change (Kearney et al., 2016 ).

In the field of knowledge co-production in public health research, co-produced (research) knowledge has long been argued to be more relevant to research users, empower communities, increase the chance of research uptake, and to ultimately affect health outcomes, but evidence supporting this has been scarce (Oliver et al., 2019 ). Whilst preliminary, our findings elucidate how the non-hierarchical, discussion-based co-production of knowledge on gender, sex, and relationships in sex education interventions makes this knowledge more relevant to participants, which may inform other interventions employing co-production approaches as part of an intervention in SRH and other public health fields.