Figures and Charts

What this handout is about.

This handout will describe how to use figures and tables to present complicated information in a way that is accessible and understandable to your reader.

Do I need a figure/table?

When planning your writing, it is important to consider the best way to communicate information to your audience, especially if you plan to use data in the form of numbers, words, or images that will help you construct and support your argument. Generally speaking, data summaries may take the form of text, tables or figures. Most writers are familiar with textual data summaries and this is often the best way to communicate simple results. A good rule of thumb is to see if you can present your results clearly in a sentence or two. If so, a table or figure is probably unnecessary. If your data are too numerous or complicated to be described adequately in this amount of space, figures and tables can be effective ways of conveying lots of information without cluttering up your text. Additionally, they serve as quick references for your reader and can reveal trends, patterns, or relationships that might otherwise be difficult to grasp.

So what’s the difference between a table and a figure anyway?

Tables present lists of numbers or text in columns and can be used to synthesize existing literature, to explain variables, or to present the wording of survey questions. They are also used to make a paper or article more readable by removing numeric or listed data from the text. Tables are typically used to present raw data, not when you want to show a relationship between variables.

Figures are visual presentations of results. They come in the form of graphs, charts, drawings, photos, or maps. Figures provide visual impact and can effectively communicate your primary finding. Traditionally, they are used to display trends and patterns of relationship, but they can also be used to communicate processes or display complicated data simply. Figures should not duplicate the same information found in tables and vice versa.

Using tables

Tables are easily constructed using your word processor’s table function or a spread sheet program such as Excel. Elements of a table include the Legend or Title, Column Titles, and the Table Body (quantitative or qualitative data). They may also include subheadings and footnotes. Remember that it is just as important to think about the organization of tables as it is to think about the organization of paragraphs. A well-organized table allows readers to grasp the meaning of the data presented with ease, while a disorganized one will leave the reader confused about the data itself, or the significance of the data.

Title: Tables are headed by a number followed by a clear, descriptive title or caption. Conventions regarding title length and content vary by discipline. In the hard sciences, a lengthy explanation of table contents may be acceptable. In other disciplines, titles should be descriptive but short, and any explanation or interpretation of data should take place in the text. Be sure to look up examples from published papers within your discipline that you can use as a model. It may also help to think of the title as the “topic sentence” of the table—it tells the reader what the table is about and how it’s organized. Tables are read from the top down, so titles go above the body of the table and are left-justified.

Column titles: The goal of column headings is to simplify and clarify the table, allowing the reader to understand the components of the table quickly. Therefore, column titles should be brief and descriptive and should include units of analysis.

Table body: This is where your data are located, whether they are numerical or textual. Again, organize your table in a way that helps the reader understand the significance of the data. Be sure to think about what you want your readers to compare, and put that information in the column (up and down) rather than in the row (across). In other words, construct your table so that like elements read down, not across. When using numerical data with decimals, make sure that the decimal points line up. Whole numbers should line up on the right.

Other table elements

Tables should be labeled with a number preceding the table title; tables and figures are labeled independently of one another. Tables should also have lines demarcating different parts of the table (title, column headers, data, and footnotes if present). Gridlines or boxes should not be included in printed versions. Tables may or may not include other elements, such as subheadings or footnotes.

Quick reference for tables

Tables should be:

- Centered on the page.

- Numbered in the order they appear in the text.

- Referenced in the order they appear in the text.

- Labeled with the table number and descriptive title above the table.

- Labeled with column and/or row labels that describe the data, including units of measurement.

- Set apart from the text itself; text does not flow around the table.

Table 1. Physical characteristics of the Doctor in the new series of Doctor Who

Table 2. Physical characteristics of the Doctor in the new series of Doctor Who

Using figures

Figures can take many forms. They may be graphs, diagrams, photos, drawings, or maps. Think deliberately about your purpose and use common sense to choose the most effective figure for communicating the main point. If you want your reader to understand spatial relationships, a map or photograph may be the best choice. If you want to illustrate proportions, experiment with a pie chart or bar graph. If you want to illustrate the relationship between two variables, try a line graph or a scatterplot (more on various types of graphs below). Although there are many types of figures, like tables, they share some typical features: captions, the image itself, and any necessary contextual information (which will vary depending on the type of figure you use).

Figure captions

Figures should be labeled with a number followed by a descriptive caption or title. Captions should be concise but comprehensive. They should describe the data shown, draw attention to important features contained within the figure, and may sometimes also include interpretations of the data. Figures are typically read from the bottom up, so captions go below the figure and are left-justified.

The most important consideration for figures is simplicity. Choose images the viewer can grasp and interpret clearly and quickly. Consider size, resolution, color, and prominence of important features. Figures should be large enough and of sufficient resolution for the viewer to make out details without straining their eyes. Also consider the format your paper will ultimately take. Journals typically publish figures in black and white, so any information coded by color will be lost to the reader. On the other hand, color might be a good choice for papers published to the web or for PowerPoint presentations. In any case, use figure elements like color, line, and pattern for effect, not for flash.

Additional information

Figures should be labeled with a number preceding the table title; tables and figures are numbered independently of one another. Also be sure to include any additional contextual information your viewer needs to understand the figure. For graphs, this may include labels, a legend explaining symbols, and vertical or horizontal tick marks. For maps, you’ll need to include a scale and north arrow. If you’re unsure about contextual information, check out several types of figures that are commonly used in your discipline.

Quick reference for figures

Figures should be:

- Labeled (under the figure) with the figure number and appropriate descriptive title (“Figure” can be spelled out [“Figure 1.”] or abbreviated [“Fig. 1.”] as long as you are consistent).

- Referenced in the order they appear in the text (i.e. Figure 1 is referenced in the text before Figure 2 and so forth).

- Set apart from the text; text should not flow around figures.

Every graph is a figure but not every figure is a graph. Graphs are a particular set of figures that display quantitative relationships between variables. Some of the most common graphs include bar charts, frequency histograms, pie charts, scatter plots, and line graphs, each of which displays trends or relationships within and among datasets in a different way. You’ll need to carefully choose the best graph for your data and the relationship that you want to show. More details about some common graph types are provided below. Some good advice regarding the construction of graphs is to keep it simple. Remember that the main objective of your graph is communication. If your viewer is unable to visually decode your graph, then you have failed to communicate the information contained within it.

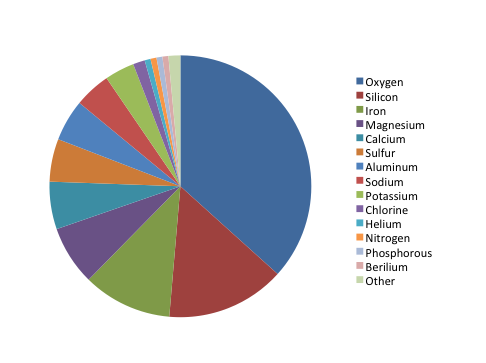

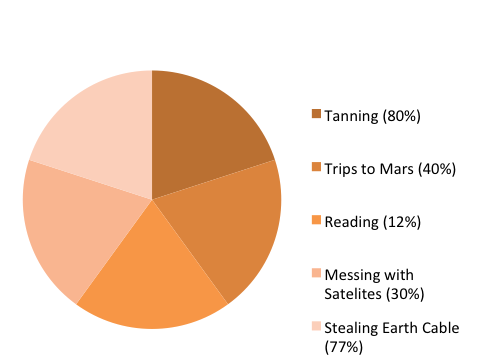

Pie charts are used to show relative proportions, specifically the relationship of a number of parts to the whole. Use pie charts only when the parts of the pie are mutually exclusive categories and the sum of parts adds up to a meaningful whole (100% of something). Pie charts are good at showing “big picture” relationships (i.e. some categories make up “a lot” or “a little” of the whole thing). However, if you want your reader to discern fine distinctions within your data, the pie chart is not for you. Humans are not very good at making comparisons based on angles. We are much better at comparing length, so try a bar chart as an alternative way to show relative proportions. Additionally, pie charts with lots of little slices or slices of very different sizes are difficult to read, so limit yours to 5-7 categories.

The chart shows the relative proportion of fifteen elements in Martian soil, listed in order from “most” to “least”: oxygen, silicon, iron, magnesium, calcium, sulfur, aluminum, sodium, potassium, chlorine, helium, nitrogen, phosphorus, beryllium, and other. Oxygen makes up about ⅓ of the composition, while silicon and iron together make up about ¼. The remaining slices make up smaller proportions, but the percentages aren’t listed in the key and are difficult to estimate. It is also hard to distinguish fifteen colors when comparing the pie chart to the color coded key.

The chart shows the relative proportion of five leisure activities of Venusian teenagers (tanning, trips to Mars, reading, messing with satellites, and stealing Earth cable). Although each of the five slices are about the same size (roughly 20% of the total), the percentage of Venusian teenagers engaging in each activity varies widely (tanning: 80%, trips to Mars: 40%, reading: 12%, messing with satellites: 30%, stealing Earth cable: 77%). Therefore, there is a mismatch between the labels and the actual proportion represented by each activity (in other words, if reading represents 12% of the total, its slice should take up 12% of the pie chart area), which makes the representation inaccurate. In addition, the labels for the five slices add up to 239% (rather than 100%), which makes it impossible to accurately represent this dataset using a pie chart.

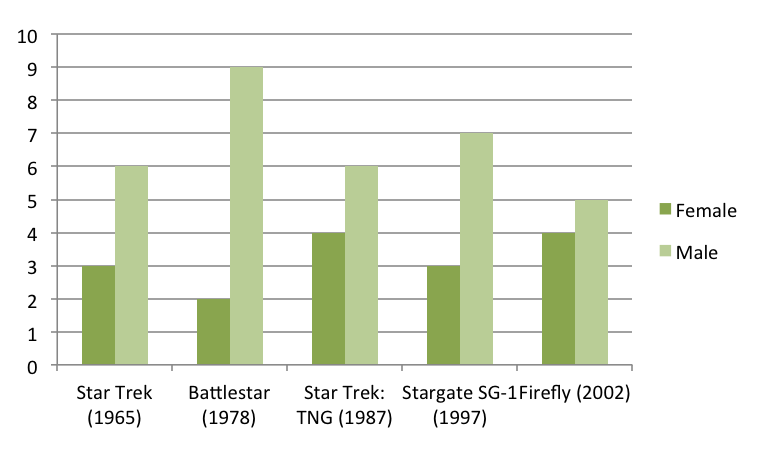

Bar graphs are also used to display proportions. In particular, they are useful for showing the relationship between independent and dependent variables, where the independent variables are discrete (often nominal) categories. Some examples are occupation, gender, and species. Bar graphs can be vertical or horizontal. In a vertical bar graph the independent variable is shown on the x axis (left to right) and the dependent variable on the y axis (up and down). In a horizontal one, the dependent variable will be shown on the horizontal (x) axis, the independent on the vertical (y) axis. The scale and origin of the graph should be meaningful. If the dependent (numeric) variable has a natural zero point, it is commonly used as a point of origin for the bar chart. However, zero is not always the best choice. You should experiment with both origin and scale to best show the relevant trends in your data without misleading the viewer in terms of the strength or extent of those trends.

The graph shows the number of male and female spaceship crew members for five different popular television series: Star Trek (1965), Battlestar (1978), Star Trek: TNG (1987), Stargate SG-1 (1997), and Firefly (2002). Because the television series are arranged chronologically on the x-axis, the graph can also be used to look for trends in these numbers over time.

Although the number of crew members for each show is similar (ranging from 9 to 11), the proportion of female and male crew members varies. Star Trek has half as many female crew members as male crew members (3 and 6, respectively), Battlestar has fewer than one-fourth as many female crew members as male crew members (2 and 9, respectively), Star Trek: TNG has four female crew members and six male crew members, Stargate SG-1 has less than one-half as many female crew members as male crew members (3 and 7, respectively), and Firefly has four female and five male crew members.

Frequency histograms/distributions

Frequency histograms are a special type of bar graph that show the relationship between independent and dependent variables, where the independent variable is continuous, rather than discrete. This means that each bar represents a range of values, rather than a single observation. The dependent variables in a histogram are always numeric, but may be absolute (counts) or relative (percentages). Frequency histograms are good for describing populations—examples include the distribution of exam scores for students in a class or the age distribution of the people living in Chapel Hill. You can experiment with bar ranges (also known as “bins”) to achieve the best level of detail, but each range or bin should be of uniform width and clearly labeled.

XY scatter plots

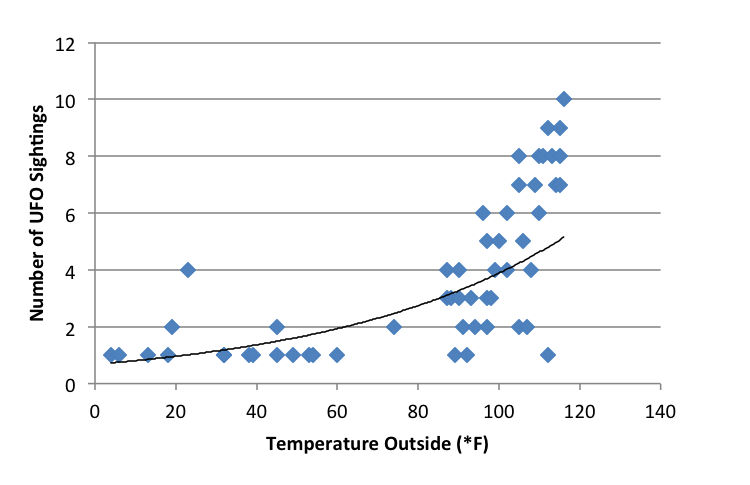

Scatter plots are another way to illustrate the relationship between two variables. In this case, data are displayed as points in an x,y coordinate system, where each point represents one observation along two axes of variation. Often, scatter plots are used to illustrate correlation between two variables—as one variable increases, the other increases (positive correlation) or decreases (negative correlation). However, correlation does not necessarily imply that changes in one variable cause changes in the other. For instance, a third, unplotted variable may be causing both. In other words, scatter plots can be used to graph one independent and one dependent variable, or they can be used to plot two independent variables. In cases where one variable is dependent on another (for example, height depends partly on age), plot the independent variable on the horizontal (x) axis, and the dependent variable on the vertical (y) axis. In addition to correlation (a linear relationship), scatter plots can be used to plot non-linear relationships between variables.

The scatter plot shows the relationship between temperature (x-axis, independent variable) and the number of UFO sightings (y-axis, dependent variable) for 53 separate data points. The temperature ranges from about 0°F and 120°F, and the number of UFO sightings ranges from 1 to 10. The plot shows a low number of UFO sightings (ranging from 1 to 4) at temperatures below 80°F and a much wider range of the number of sightings (from 1 to 10) at temperatures above 80°F. It appears that the number of sightings tends to increase as temperature increases, though there are many cases where only a few sightings occur at high temperatures.

XY line graphs

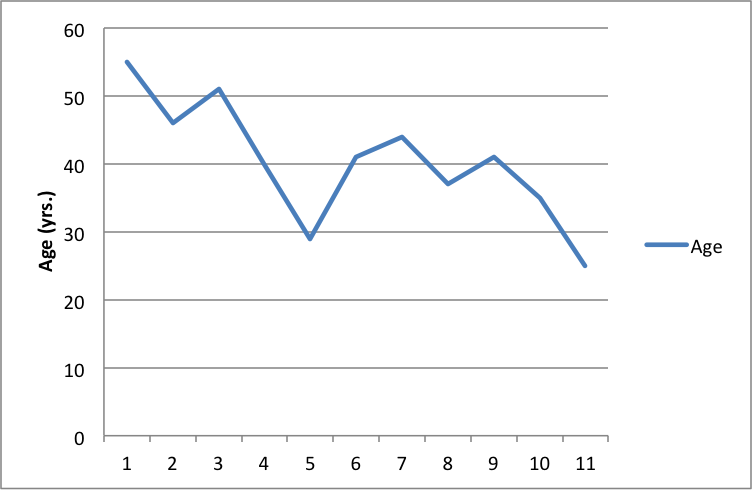

Line graphs are similar to scatter plots in that they display data along two axes of variation. Line graphs, however, plot a series of related values that depict a change in one variable as a function of another, for example, world population (dependent) over time (independent). Individual data points are joined by a line, drawing the viewer’s attention to local change between adjacent points, as well as to larger trends in the data. Line graphs are similar to bar graphs, but are better at showing the rate of change between two points. Line graphs can also be used to compare multiple dependent variables by plotting multiple lines on the same graph.

Example of an XY line graph:

The line graph shows the age (in years) of the actor of each Doctor Who regeneration for the first through the eleventh regeneration. The ages range from a maximum of about 55 in the first regeneration to a minimum of about 25 in the eleventh regeneration. There is a downward trend in the age of the actors over the course of the eleven regenerations.

General tips for graphs

Strive for simplicity. Your data will be complex. Don’t be tempted to convey the complexity of your data in graphical form. Your job (and the job of your graph) is to communicate the most important thing about the data. Think of graphs like you think of paragraphs—if you have several important things to say about your data, make several graphs, each of which highlights one important point you want to make.

Strive for clarity. Make sure that your data are portrayed in a way that is visually clear. Make sure that you have explained the elements of the graph clearly. Consider your audience. Will your reader be familiar with the type of figure you are using (such as a boxplot)? If not, or if you’re not sure, you may need to explain boxplot conventions in the text. Avoid “chartjunk.” Superfluous elements just make graphs visually confusing. Your reader does not want to spend 15 minutes figuring out the point of your graph.

Strive for accuracy. Carefully check your graph for errors. Even a simple graphical error can change the meaning and interpretation of the data. Use graphs responsibly. Don’t manipulate the data so that it looks like it’s saying something it’s not—savvy viewers will see through this ruse, and you will come off as incompetent at best and dishonest at worst.

How should tables and figures interact with text?

Placement of figures and tables within the text is discipline-specific. In manuscripts (such as lab reports and drafts) it is conventional to put tables and figures on separate pages from the text, as near as possible to the place where you first refer to it. You can also put all the figures and tables at the end of the paper to avoid breaking up the text. Figures and tables may also be embedded in the text, as long as the text itself isn’t broken up into small chunks. Complex raw data is conventionally presented in an appendix. Be sure to check on conventions for the placement of figures and tables in your discipline.

You can use text to guide the reader in interpreting the information included in a figure, table, or graph—tell the reader what the figure or table conveys and why it was important to include it.

When referring to tables and graphs from within the text, you can use:

- Clauses beginning with “as”: “As shown in Table 1, …”

- Passive voice: “Results are shown in Table 1.”

- Active voice (if appropriate for your discipline): “Table 1 shows that …”

- Parentheses: “Each sample tested positive for three nutrients (Table 1).”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bates College. 2012. “ Almost everything you wanted to know about making tables and figures.” How to Write a Paper in Scientific Journal Style and Format , January 11, 2012. http://abacus.bates.edu/~ganderso/biology/resources/writing/HTWtablefigs.html.

Cleveland, William S. 1994. The Elements of Graphing Data , 2nd ed. Summit, NJ: Hobart Press..

Council of Science Editors. 2014. Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers , 8th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

University of Chicago Press. 2017. The Chicago Manual of Style , 17th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Graphic Essays and Comics

Overview | Recommended Software | Student-Made Examples | Other Examples | Instructional Video

A graphic essay (sometimes called a visual essay) uses a combination of text and images to explore a specific topic. Graphic essays can look like comics, graphic novels, magazines, collages, artist books, textbooks, or even websites. Graphic essays often first take the form of written essays and then have graphic elements added to enrich the reader experience. Unlike infographics, which also combine text and images, graphic essays are often more text-based and usually have a narrative arc or specific reading order.

Comics are a genre used to express ideas through images combined with text or other visual information. Comics can take the form of a single panel or a series of juxtaposed panels of images, sometimes called a strip. Text is conveyed via captions below the panel(s), or speech bubbles and onomatopoeias within the panel(s), to indicate dialogue, narration, sound effects, or other information. Graphic novels are often considered to be a longer form of comics, typically in book form.

A web-based graphic essay can take the form of a blog or a single page website, such as a Microsoft Sway page or an interactive Prezi. For Microsoft Sway and Prezi graphic essays, see the examples below. If you are creating a blog we recommend visiting the Web-Based Projects page .

Graphic Essay Design Tip: Graphic essays can take many forms, so we recommend being creative within the scope of your project! Get some help from DesignLab to brainstorm options and talk through the various tools available!

Make an Appointment

Recommended Software

There are many different software programs that can be used to create graphic essays. Below is a list of the software that we recommend for making a graphic essay. We organized the software by category and put the software from top to bottom from best to worst. We recommend using a software you know well or learning the software well enough to establish an easy workflow, so you can spend less time troubleshooting and spend more time on your project. Check out our Software Support page for links to tutorials for all of these programs.

General Graphic Essay Software

Web-Based Graphic Essay Software

Comic-Specific Graphic Essay Software

Student-Made Examples

Print style graphic essay.

Becoming a Witness by Jessica Posnock

Creative Graphic Essay

Virtual Communication by Max Hautala *Award Winning*

Curb Magazine (2012) by Journalism 417

Web-Based (Magazine) Graphic Essay

Curb Magazine (Current) by Journalism 417

Web-Based (Sway) Graphic Essay

Language Influences Culture, Thoughts, and Identity by Kristen Luckow *Award Winning*

Dyslexia by Maria Swanke *Award Winning*

Other Examples

Web-based (blog) graphic essay.

Switch It Up: Graphic Essay by Amanda Zieba

Graphic Novel

Graphic Novels in the Classroom by Gene Yang

Instructional Video

Using Graphic Organizers for Writing Essays, Summaries and Research

Ask any student – essay writing is one of the most despised tasks of their educational career. Perhaps there is so much displeasure associated with the task because it’s perceived as too linear – there isn’t enough visual and creative appeal. But if you use graphic organizer for writing essays then you can make writing enjoyable – or at least less terrible.

Not only enjoyable but graphic organizers (or diagrams) can make the writing process a snap. They’ll help you think outside the box, draw conclusions you wouldn’t normally observe, and make the entire process faster and more efficient.

Why Use Graphic Organizers for Writing

The phrase “graphic organizer” is just a fancy way of saying “diagram” or “visual aid.” Basically, they are a visual representation of the information you’ve acquired in the research process. There are quite a few reasons why you should use them when writing essays or summaries.

- Helps you visualize your research and how elements connect with each other

- Enhance your essays, summaries and research papers with visual elements

- Track correlations between your thoughts, observations, facts or general ideas

When it comes to essay writing, the most common graphic organizers are webs, mind maps, and concept maps .

Using Webs for Brainstorming

Webbing is a great way to see how various topics are interrelated. This graphic organizer is particularly useful during the brainstorming step of the writing process.

A web can sometimes get a bit messy. Usually, there are lots of arrows to connect overlapping ideas. However, even with lines crisscrossing every which way, it is still a great way to visualize your thoughts. If you’re using an online diagramming software like Creately you can overcome some of this because we automatically arrange the object for you.

Once you’ve created a map to document all your ideas and establish connections, you can easily transition to other forms of diagramming to better organize the information.

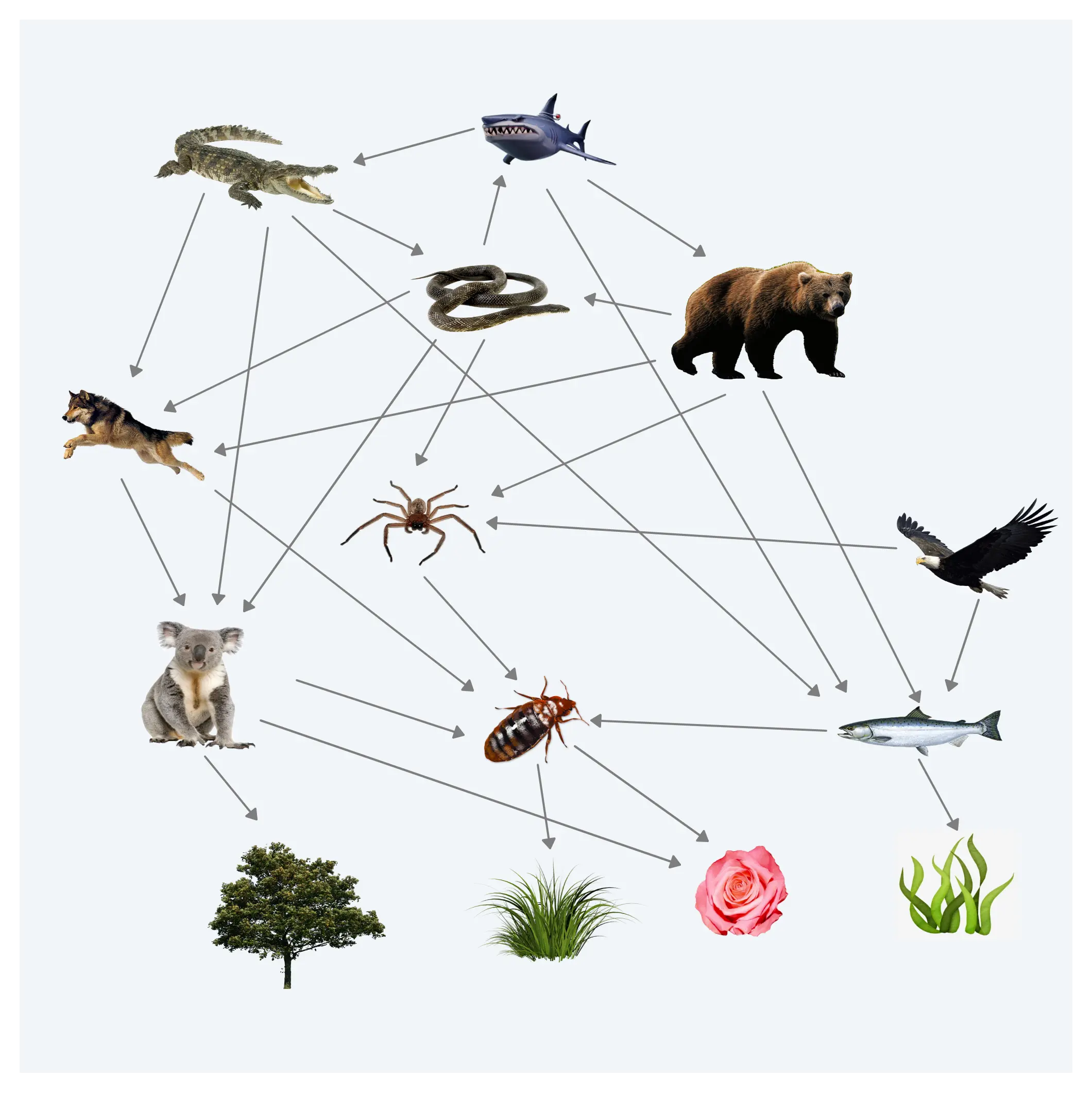

For example if you’re writing a research paper about the food web of the Australian bushes you can start creating a food web diagram similar to the one below. This way you can easily visualize the web while writing the paper. This is a simple example but graphic organizers become even more important when the subject gets complex.

Although simple this example shows the importance of using graphic organizers for writing summaries. A comprehensive diagram pretty much does the summation for you.

Using Mind Maps as Graphic Organizers

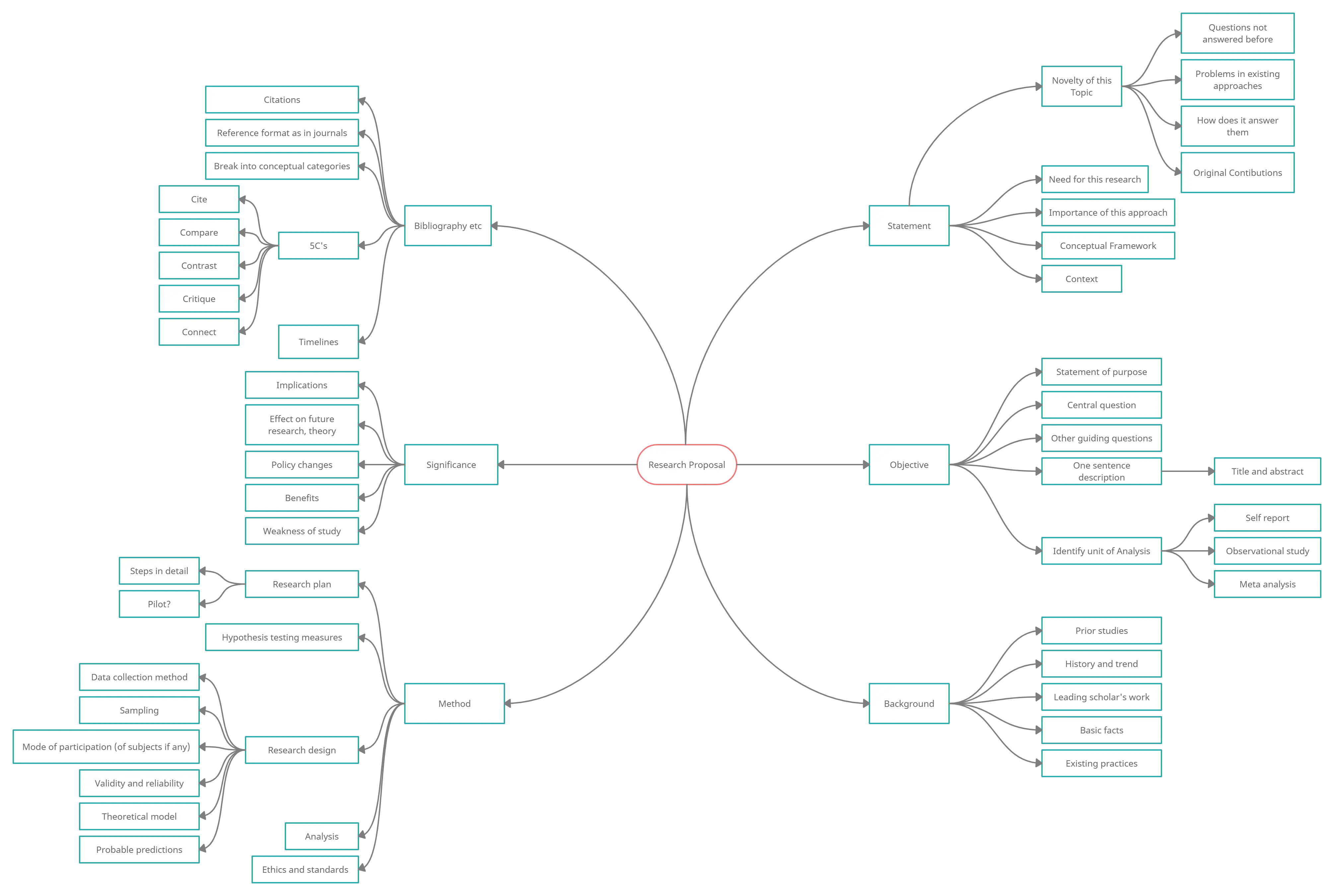

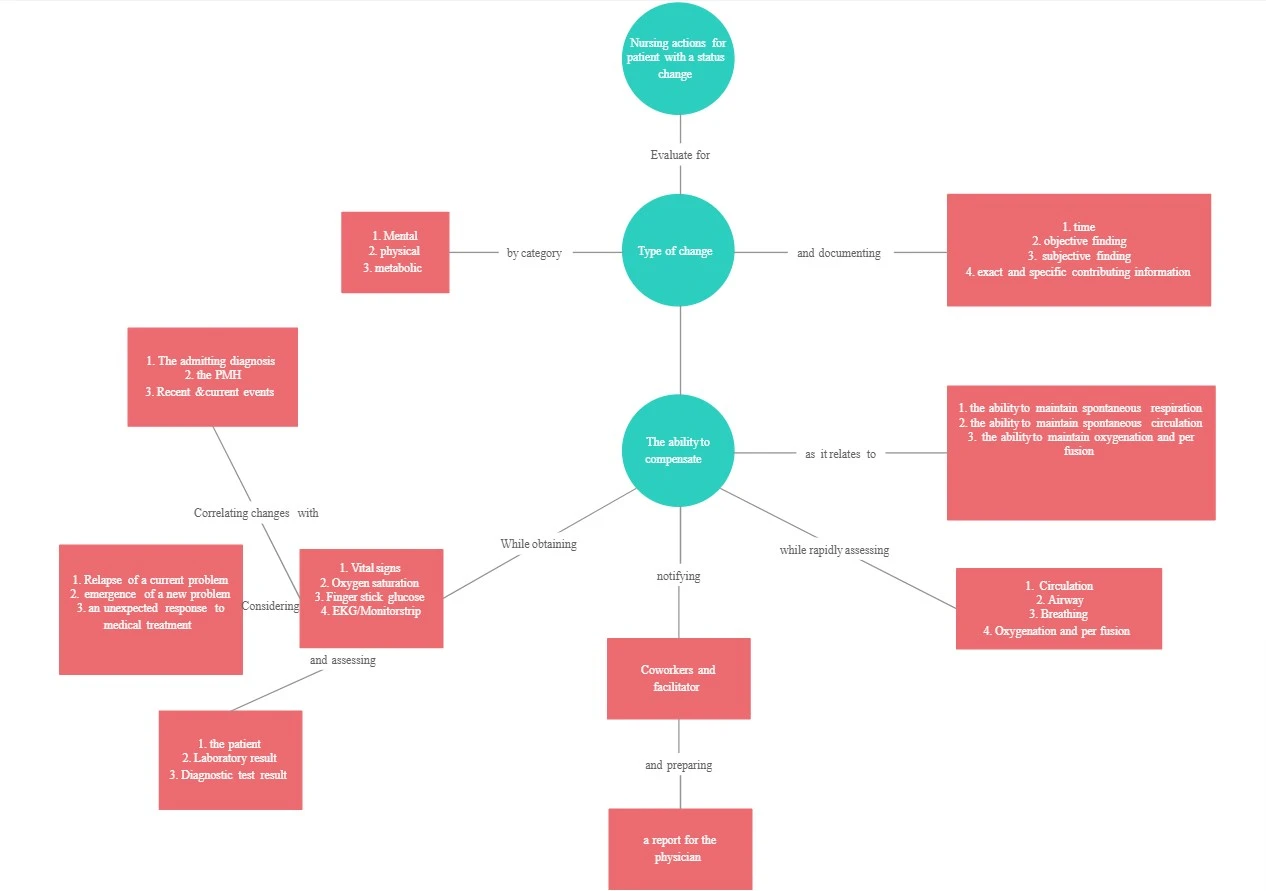

Mind maps are a great way to depict a hierarchy. What is hierarchical organization ? The concept is simple: a singular topic dominates with each subsequent idea decreasing in importance.

Usually, the mind map starts with the thesis (or main idea) at the center. From there, you can branch out with your supporting evidence.

Use this process to replace your traditional note taking technique – note cards, outlines, whatever. You’ll quickly realize a mind map is a great way to formulate the structure of your essay. The thing to note here is that the nature of the mind maps force you think about sub topics and how to organize your ideas. And once the ideas are organized writing the essay become very easy.

Above is a mind map of a research proposal. Click on it to see the full image or you can see the fully editable template via this link . As you can see in this mind map the difference areas of the research proposal is highlighted. Similarly when your writing the research paper you can use a mind map to break it down to sub topics. We have more mind map templates for you to get started.

Concept Maps

A concept map will help you visualize the connection between ideas. You can easily see cause and effect – how one concept leads to another. Often times, concept mapping includes the use of short words or phrases to depict the budding relationship between these concepts.

If you look closely you can see that its very similar to a mind map. But a concept maps gives more of a free reign compares to the rigid topic structure of a mind map. I’d say it’s the perfect graphic organizer for writing research papers where you have the license to explore.

By creating a concept map , you can also see how a broad subject can be narrowed down into specific ideas. This is a great way to counter writers block. Often, we look at the big picture and fail to see the specifics that lead to it. Identifying contributing factors and supporting evidence is difficult. But with a concept map, you can easily see how the smaller parts add up to the whole.

Why Bother With Graphic Organizers?

If you already detest the writing process, adding another step might seem insane. However, there really are several advantages of using them. If you haven’t already accepted the benefits of each individual diagram style, here are some more perks of graphic organizers in general:

- Quality essays are based on detail. No one is going to accept your opinions and reasoning just because you say so. You’ll need proof. And organizing that proof will require attention to detail. Graphic organizers can help you see that detail and how it contributes to the overall concept.

- Graphic organizers are flexible. You don’t need one of those giant pink erasers. You don’t need to restructure your outline. All you have to do is draw a few arrows and bam – the relationship has totally changed.

- No matter what you are writing about, a graphic organizer can help. They can be used to structure an essay on the Great Wall, theoretical physics, or Spanish speaking countries.

- If you write an outline, can you easily see how point A influences point X? Probably not. But if little thought bubble A is sitting out there all by itself, you can visualize the way it ties into point R, T and X.

- Some of us find it difficult to put our opinions, thoughts, and ideas into writing. However, communicating our feelings with little doodles and sketches is far less threatening.

- As a writer, our brain often feels like a 2-year-old’s toy box – a big jumbled mess. Taking that mess and putting it onto paper with some semblance of organization is challenging. Rather than trying to take your thoughts from total chaos to a perfectly structured list, just try to get them out of your brain and onto paper in the form of a diagram.

- A graphic organizer helps you establish validity and relevance. You can easily nix the ideas that don’t support or enhance your thesis.

The next time you are faced with a writing project, take a few minutes to explore the efficiency of graphic organizers. You can find a wealth of templates here.

Have you ever used a graphic organizer to structure an essay? How did it go? Do you have a diagram suggestion for the writing process that wasn’t mentioned here? Let us know!

Join over thousands of organizations that use Creately to brainstorm, plan, analyze, and execute their projects successfully.

More Related Articles

These are awesome guest posts contributed by our users and technology enthusiasts. Do you have something interesting to share? Want to get exposed to a massive tech audience? Check out our Guest Posting Guidelines to how to proceed.

How to Use Graphic Organizers to Write Better Essays

Lucid Content

Reading time: about 6 min

If you’re a student, there’s no way around the inevitable: You’re going to have to write essays. Lots of essays. In fact, the five-paragraph essay is so fundamental to the high school curriculum that it’s still used on the ACTs, and knowing how to recognize the organizational structure of essays will help you score higher on the SATs.

Even though it seems like a chore, knowing how to organize and write an essay can have a lasting effect on your life, from getting into a better college to scoring a better job to performing better in that job long after your high school days are over.

Here’s a secret: Using graphic organizers for writing essays can help you write better essays faster. (And don’t count yourself out if you’re an educator—you can offer these tools to help your students succeed.) We’ll show you exactly how to do it.

Why use graphic organizers

When ACT graders or teachers are looking your essay, they’re looking for very specific criteria; essentially, they’re looking at how well you’ve organized your thoughts. Many students don’t take the time to outline their essay structure before writing, and that always means a lower score on a test and a lower grade on the essay in class.

Using a writing template can feel like an unnecessary step in an already complicated process. If you need extra motivation to implement these organizers into your writing routine, consider all of their benefits. Graphic organizers can help you:

- Save time by showing you where each piece of the essay “lives.”

- Have more productive brainstorming sessions, either by yourself or with a group.

- Make connections between ideas and create a more cohesive argument.

- Pinpoint holes in your arguments and either adjust the thesis or find supporting statements.

- Keep track of your research.

- Organize your thoughts and come to interesting, more compelling conclusions.

- Stay in the right direction when you feel lost in a sea of words.

- Manage anxiety by converting the fear of a blank assignment into an action plan with a clear map.

With all those benefits, it’s hard to ignore how useful and vital graphic organizers are to writing. And once you’ve become adept at organizing your thoughts for something like a school essay, you’ll find that skill carries with you throughout your life, whether you’re trying to become a more intelligent debater to negotiate prices. It goes beyond just the essay to becoming a better thinker. And it starts with a simple template.

We’ll walk you through several use cases for graphic organizers and provide templates for you to download and fill in when you’re ready to write.

Brainstorming graphic organizers

Brainstorming is important, not only to come up with ideas for topics but to determine what information you need to include in the essay once you’ve determined your topic. Though many think of brainstorming as just freeflow thinking, brainstorming is most productive when you work within specific parameters.

That’s why essay brainstorming graphic organizers are useful, whether you’re using one to brainstorm on your own or you’re working with a group.

In Lucidchart, our mind map shapes and templates double as brainstorming graphic organizers. Start with an essay prompt as your central shape and then fill in the shapes that branch off your prompt with topic ideas. Alternatively, you can add your selected topic to the center and start brainstorming the different ideas you need to cover in your paper.

When the template is filled in, you’ll have a clear starting point for your essay or research paper.

Research paper graphic organizers

Nothing paralyzes students with fear quite like a research paper. These long-form papers require—as the name implies—quite a bit of research, and their purpose is to teach students how to look for valid sources to support their arguments.

But keeping track of all those sources and tying them into your argument can be tricky. That’s where a research paper graphic organizer can be a student’s greatest ally.

This template lays out the writing process itself. After you come up with a general topic, like “the disappearance of honey bees,” fill in the “Research Paper Topic” box.

Then, start looking for reputable sources (Wikipedia doesn’t count) and use the five sources boxes to hold the most relevant quotes and statistics you find. Using those quotes and statistics, you can then fill out a thesis statement that is supported by the research.

Then, you’ll be able to focus your paragraphs on a single topic each that supports the thesis statement and your overarching argument. After you’ve filled out the template, the backbone of the research paper is complete: All that’s left to do is fill in the spaces between sources and arguments.

5-paragraph essay graphic organizer

When it comes to writing the five-paragraph essay, writing diagrams are key. By using graphic organizers for writing, you’re no longer staring at a giant blank piece of paper with no idea how or where to begin. Your graphic organizer is your map.

Although using writing diagrams may seem time-consuming, the fact is that taking the time to fill a graphic organizer in before writing actually saves time. If there’s a problem with the argument, it will show up on the diagram, or if there’s not enough evidence to support your argument, you’ll know before you’ve wasted time writing the paper. And, as we said before, even if your writing is terrible, if your argument is sound, you’ll still score a decent grade.

Try this 5-paragraph essay template to get you started.

Don’t feel pressured to come up with a compelling title right away. Instead, it’s more important that you come up with a thesis statement that can be supported by three solid arguments. Fill in that thesis statement and your arguments. Then, for each argument, figure out three supporting details to support your case.

That’s it! You’ve got the most essential parts of your 5-paragraph essay completed.

Now, come up with an introduction that sets the stage for your argument and a conclusion that wraps up and restates your thesis and supporting arguments in a compelling way. Now you have a solid plan for your paper and can approach it with confidence.

If you’d like a more linear graphic that exactly follows the structure of the 5-paragraph, use the writing template below and follow the same process.

Visuals, such as graphic organizers for writing, can help you better understand concepts, think creatively, and collaborate with your classmates—and there are plenty of other templates where these came from.

Lucidchart offers hundreds of templates to help you through your studies, including timelines, Venn diagrams, word maps, and more. Sign up for Lucidchart and upgrade to an Educational account for free.

Resources for teachers

Providing graphic resources to students is essential; after all, many of your students will be visual learners, so while you may beautifully explain how the process works, there will be some who won’t understand until they see a template of the essay itself.

Lucidchart has many resources for teachers, from lesson plans to writing templates. While you’re teaching your students how to write essays or research papers, it’s useful to print out the templates and fill them out together (even using a completed template as a separate assignment with a separate grade) so that your students can get a feel for properly filling out graphic organizers before attempting it on their own.

About Lucidchart

Lucidchart, a cloud-based intelligent diagramming application, is a core component of Lucid Software's Visual Collaboration Suite. This intuitive, cloud-based solution empowers teams to collaborate in real-time to build flowcharts, mockups, UML diagrams, customer journey maps, and more. Lucidchart propels teams forward to build the future faster. Lucid is proud to serve top businesses around the world, including customers such as Google, GE, and NBC Universal, and 99% of the Fortune 500. Lucid partners with industry leaders, including Google, Atlassian, and Microsoft. Since its founding, Lucid has received numerous awards for its products, business, and workplace culture. For more information, visit lucidchart.com.

Related articles

Mind mapping as a tool for the writing process.

Check out how Annika, a recent English graduate of the University of Michigan, used mind mapping in Lucidchart to develop her honors thesis.

Bring your bright ideas to life.

or continue with

By registering, you agree to our Terms of Service and you acknowledge that you have read and understand our Privacy Policy .

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Erin Wright Writing

Writing-Related Software Tutorials

How to Write Figure Captions for Graphs, Charts, Photos, Drawings, and Maps

By Erin Wright

Figures are visuals such as charts, graphs, photos, drawings, and maps. Figures are normally identified by the capitalized word Figure and a number followed by a caption. A caption is a short block of text that gives information about the figure. The following seven tips explain how to write figure captions in your book, article, or research paper.

Although closely related, tables aren’t considered figures. See “ How to Write Table Titles ” for more information.

These tips are general guidelines based on our primary style guides . Each style guide has its own caption format (e.g., line spacing , margins, fonts). Therefore, you should consult your designated guide for specific recommendations, as necessary.

Seven Tips for Writing Figure Captions

Figure 1 and figure 2, located at the bottom of this post, demonstrate the guidelines explained in these tips.

1. Use captions instead of titles.

Figures in traditionally published books and scholarly writing usually have captions instead of titles. 2

However, some journals use titles and captions for figures. 3 Before submitting an article to a specific journal, always check its formatting requirements.

2. Place captions under figures.

Captions typically appear under figures. 4 Sometimes captions appear beside or even above figures; however, the decision to place captions in uncommon locations is normally made by the layout designer or production editor, not by the writer or copy editor. 5

Style Guide Alert: Written Music

The MLA Handbook (MLA style) and the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago style) use the word Example rather than Figure to identify samples of written music in text. In addition, Chicago style places captions above written music instead of below, while MLA style keeps captions under written music. 6

Note that the academic version of Chicago style, Turabian, also recommends placing captions above written music but uses Figure instead of Example . 7

If you have music samples labeled as Example in addition to other figures, the music samples should be numbered separately from the figures (e.g., Example 1, Figure 1, Example 2, Figure 2).

3. Use a period after figure numbers.

Figures can be identified with regular numbers:

They can also be identified by double numbering in which the first number identifies the chapter and the second number identifies the figure:

Figure 7.10. (the tenth figure in chapter 7)

Figure 7.11. (the eleventh figure in chapter 7)

Figure 7.12. (the twelfth figure in chapter 7)

Whether you are using regular numbers or double numbering, use a period after the figure number to separate it from the caption text. 8

You may occasionally see the period omitted in favor of bold font combined with extra space before the caption text. 9 Like placing captions in uncommon locations, this decision is usually made by a layout designer or production editor rather than the writer or copy editor.

4. Use sentence-style capitalization.

Captions should feature sentence-style capitalization rather than headline-style capitalization . 10 This recommendation applies to complete sentences and to phrases and sentence fragments.

5. End captions with a period … most of the time.

Two of our primary style guides, the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA style) and the MLA Handbook (MLA style) use periods at the end of all captions even if they are incomplete sentences. 12

One of our other primary style guides, The Chicago Manual of Style (along with its academic version, Turabian) says that periods can be omitted if your captions are all phrases or sentence fragments. But, if your captions consist of complete sentences mixed with phrases and sentence fragments, always use periods. 13

6. Include a variety of information (if necessary).

A caption should briefly describe the figure. You can also include additional information such as copyright statements, source citations, definitions of symbols, and explanations of units of measurement. 14

There’s no official guideline for how long a caption can be. But, keep your readers in mind when writing captions because long blocks of unbroken text can be difficult to read (and therefore easy to ignore). If you think your caption is too long, consider other ways to present the necessary information, including the use of legends, labels, and keys within the figure itself.

7. Reference all figures in your text.

Each figure should be referenced in a sentence in your text, preferably before the figure appears in the document. The purpose of in-text references is to show your readers how figures connect to the content they are reading.

See “ How to Reference Figures and Tables in Sentences ” for examples and information relative to specific style guides.

The captions attached to figure 1 and figure 2, below, are examples based on the seven tips explained above.

Figure 1. Above left , Bartholomew; above right , Peabody; below left , Mr. Heckle; below right , Mr. Jeckle. Photography by Erin Wright.

Figure 2. Study participants’ favorite activities rated by occurrences per day. Reproduced by permission from Erin Wright, The Pets Are Running the Show (Whiting, IN: Fake Press, 2019), 57.

Related Resources

Three Ways to Insert Tables in Microsoft Word

How to Create and Customize Charts in Microsoft Word

How to Insert Figure Captions and Table Titles in Microsoft Word

How to Change the Style of Table Titles and Figure Captions in Microsoft Word

How to Update Table and Figure Numbers in Microsoft Word

How to Create and Update a List of Tables or Figures in Microsoft Word

How to Cross-Reference Tables and Figures in Microsoft Word

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2020), 7.23–7.25.

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 6th ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2010), 5.23.

- AMA Manual of Style , 10th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 4.2.7.

- The Chicago Manual of Style , 17th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 3.21. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 5.23; “ Tables and Illustrations ,” Formatting a Research Paper, The MLA Style Center, accessed September 9, 2019; Kate L. Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations , 9th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 26.3.2.

- “ Headlines and Titles of Works ,” Style Q&A, The Chicago Manual of Style Online, accessed September 10, 2019.

- The Chicago Manual of Style , 3.5. “ Tables and Illustrations ,” The MLA Style Center.

- Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations , 26.3.2.

- The Chicago Manual of Style , 3.23; Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 5.23; “ Tables and Illustrations ,” The MLA Style Center; Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations , 26.3.2.

- The Chicago Manual of Style , 3.23.

- “ Tables and Illustrations ,” The MLA Style Center.

- The Chicago Manual of Style , 3.21; Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 5.23; Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Research Paper, Theses, and Dissertations , 26.3.3.2.

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 5.23; “ Tables and Illustrations ,” The MLA Style Center.

- The Chicago Manual of Style , 3.21; Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations , 26.3.3.1.

- The Chicago Manual of Style , 3.25; Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 5.23; Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations , 26.3.3.2

- Microsoft Word Tutorials

- Adobe Acrobat Tutorials

- PowerPoint Tutorials

- Writing Tips

- Editing Tips

- Writing-Related Resources

Assigning a Graphic Essay as an Essay Alternative

One of my favorite ways to assess my students’ essay-writing skills without actually assigning a traditional essay is with the graphic essay . A graphic essay is an excellent essay alternative for the middle school ELA or high school English classroom.

A graphic essay is a graphic representation that contains all of the essential essay elements. It combines writing, visual elements, and design. When assigning a graphic essay, you can have students include any particular aspect from the essay that you want.

Getting Started

The first step to completing a graphic essay project in your classroom is to have a clear idea of the skills and content you want to assess. For example, if you are working on an argument and persuasive unit, are you looking to assess a counterargument? If you are working on an informative piece, are you looking for explanatory evidence?

Once you know what you want to assess, start mapping out the student requirements. I’m pretty old-school when it comes to things and prefer to draft out my notes with paper and pencil. When I do this, I make a list of all of the elements that I want my students to include. For a recent project, I wanted them to include a variety of features: introduction, big ideas with supporting evidence, counter argument, quick facts, visual data representation, and a Works Cited page.

Work Before Design

Once you have your graphic essay outlined, it is time to assign it to the students. However, and I cannot stress this enough, you don’t want them to focus on the visual and graphic elements first. That is just a hot mess waiting to happen. You know how it will go. Some students will spend the entire class period deciding between a blue or green spot color design element. By the time the class period ends, they’ll have a lovely purple box on their graphic essay, but that will probably all they have accomplished—one box.

Instead, try this. Have your students work on a brainstorming organizer first. You’ll want them to brainstorm, write, and curate all of the content for the graphic essay before they start the design process. When I complete this project in my classroom, I have them draft everything, find all of the images they want to include, and submit that work for a grade before they even start the design process.

Students either love or hate the graphic design process of this alternative essay project, and that is to be expected. When we get to the design process of this project, I try to give my students several different options for creating the final project that matches different graphic design comfort levels. A few of my students usually want to use Adobe Photoshop and design everything from scratch, a few need extra guidance working in a Google Slide, and the majority are excited to try a new online platform. Please note, this is not an ad. These websites did not pay to be included in this post.

One thing that I cannot emphasize enough for this type of project is that I grade content and not design. Let me repeat that: I assess the content of the work and not the quality of the design.

Here’s a look at some of the different platforms I suggest my students use to create their graphic essay. This list is in order from easiest to most advanced.

1. Google Docs – Most students are already familiar with Google Docs. Using the draw tool, students can create images, place text, and color to their Google Docs. For my students who need the most assistance with the design process, I have them use my initial template (which I created using the draw tool in Google Docs) and a plug and play template.

2. Google Slides – Some students might prefer Google Slides over Google Docs because they might feel like they have more freedom. Using Google Slides, students can change the dimensions of each slide to 8.5×11 inches (or larger), and use the textbox tool, shape tool, and other design tools to create the graphic essay.

3. Canva.com – I love Canva because it provides students with different design templates and elements. While there is a paid version, I tell all of my students to use the free option. Using Canva, students can select a flier because that is preset to 8.5×11 inch dimensions. Once students are in Canva, there are a ton of free design tools. Students can choose from a variety of options, including preset text designs, frames, shapes, data (which is excellent for inserting bar graphs and pie charts), and pictures. Students can even upload their own images to the site as well!

4. Adobe Spark – Adobe Spark is another great online tool for students to create graphic essays and other multimedia presentations. Students can choose a custom size to create an 8.5×11 inch poster, and Adobe Spark also has premade text elements and templates to choose from.

5. Piktochart.com – Personally, I like Piktochart more for having students create infographics instead of graphic essays, but Piktochart still works. Students can the custom size or letter size to create their graphic. Piktochart has more advanced design features, and one unique design feature is that students can design their project in blocks. Similar to Canva and Adobe Spark, students can also upload their own images to their creation.

Graphic Essay Sampler

Subscribe to receive a sample of the graphic essay assignment!

I won’t send you spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

Powered By ConvertKit

Sharing the File

Once students finish creating their graphic essays, I like to have them upload their creations to one location so that all of my students can see the work that everyone created. My favorite site for this is Padlet. If you haven’t used Padlet before, it is like an online corkboard. Students can post their designs to your class’s board. Students can also comment on other students’ work if you want to add a gallery walk element to this project.

Subscribe to my email list.

Subscribe to receive freebies, teaching ideas, and my latest content by email.

Built with ConvertKit

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Format Images in an Essay

- 5-minute read

- 27th April 2022

Writing an essay ? It may enhance your argument to include some images, as long as they’re directly relevant to the essay’s narrative. But how do you format images in an essay? Read on for tips on inserting and organizing images, creating captions, and referencing.

Inserting Images

To insert an image into the text using Microsoft Word:

● Place the cursor where you want to add a picture.

● Go to Insert > Pictures .

● Click on This Device to add pictures from your own computer or select Online Pictures to search for a picture from the internet.

● Select the image you wish to use and click Insert .

See our companion blog post for further detail on inserting images into documents using Word.

Organizing Images

There are two common methods of organizing images in your essay: you can either place them next to the paragraph where they are being discussed (in-text), or group them all together at the end of the essay (list of figures). It can be clearer to display images in-text, but remember to refer to your university style guide for its specifications on formatting images.

Whichever method you decide upon, always remember to refer directly to your images in the text of your essay. For example:

● An example of Cubism can be seen in Figure 1.

● Cubist paintings have been criticized for being overly abstract (see Figure 1).

● Many paintings of this style, including those by Picasso (Figure 1), are very abstract.

Every image that you include in your essay needs to have a caption. This is so that the reader can identify the image and where it came from. Each caption should include the following:

● A label (e.g., Figure 1 ).

● A description of the image, such as “Picasso’s Guernica ,” or “ Guernica : One of Picasso’s most famous works.”

● The source of the image. Even if you have created the image yourself, you should attribute it correctly (for example, “photo by author”).

Have a look at this example:

Figure 1: Picasso’s Guernica

Photo: Flickr

Here, the image is given both a label and a title, and its source is clearly identified.

Creating Captions Using Microsoft Word

If you are using Word, it’s very simple to add a caption to an image. Simply follow the steps below:

● Click on the image.

● Open the References toolbar and click Insert Caption .

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Fill in or select the required details and click OK .

You can also add a caption manually.

Referencing Captions

At this point, you’ll need to refer to your style guide again to check which referencing system you’re using. As mentioned above, all sources should be clearly identified within the caption for the image. However, the format for captions will vary depending on your style guide. Here, we give two examples of common style guides:

- APA 7th Edition

The format for a caption in APA style is as follows:

Note. By Creator’s Initials, Last Name (Year), format. Site Name (or Museum, Location). URL

The image format refers to whether it’s a photograph, painting, or map you are citing. If you have accessed the image online, then you should give the site name, whereas if you have viewed the image in person, you should state the name and location of the museum. The figure number and title should be above the image, as shown:

Figure 1

Note . By P. Picasso (1937), painting. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/huffstutterrobertl/5257246455

If you were to refer to the image in the text of your essay, simply state the creator’s last name and year in parentheses:

(Picasso, 1937).

Remember that you should also include the details of the image in your reference list .

MLA style dictates that an image caption should be centered, and each figure labeled as “Fig.” and numbered. You then have two options for completing the caption:

1. Follow the Works Cited format for citing an image, which is as follows:

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Image Title.” Website Name , Day Month Year, URL.

2. Provide key information about the source, such as the creator, title, and year.

In this case, we have followed option 1:

Fig. 1. Picasso, Pablo. “Guernica.” Flickr , 1937, https://www.flickr.com/photos/huffstutterrobertl/5257246455

When referring to the image in the text of the essay, you need only cite the creator’s last name in parentheses:

And, again, remember to include the image within the Works Cited list at the end of your essay.

Expert Proofreading and Formatting

We hope this guide has left you a little clearer on the details of formatting images in your essays . If you need any further help, try accessing our expert proofreading and formatting service . It’s available 24 hours a day!a

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

K-12 Resources By Teachers, For Teachers Provided by the K-12 Teachers Alliance

- Teaching Strategies

- Classroom Activities

- Classroom Management

- Technology in the Classroom

- Professional Development

- Lesson Plans

- Writing Prompts

- Graduate Programs

What is a Graphic Organizer and How to Use it Effectively

Janelle cox.

- September 16, 2020

As educators, we’re always looking for new ways to help students classify and communicate their ideas more effectively. A visual guide, such as a graphic organizer, can do just that, as well as help students plan and structure their ideas in an organized manner. Here we will take a brief look at what a graphic organizer is, the different types of graphic organizers that you can use, as well as how you can use them effectively in the classroom.

What is a Graphic Organizer?

A graphic organizer is a powerful, visual learning tool that teachers like to use to help students organize their ideas. They can also be used to clarify or simplify complex concepts, help with problem solving or decision making , or be used to plan research or brainstorm ideas.

What are the Different Types of Graphic Organizers?

While there are several types of graphic organizers, each with a specific purpose, we will briefly go over the top five most popular used in the classroom.

Venn Diagram

A Venn diagram is a graphic organizer that has two interlocking circles. This type of organizer is used to identify differences and similarities. Students write details about how the topics are different in the outer parts of the circles and how they are the same in the shared inner space of circles.

Venn diagrams can be used to compare and contrast two characters. For example, students would write how each character is different in the outer spaces and how they are the same in the overlapping space in the middle. Then, students can use this graphic organizer to help them write an essay about each character.

Concept Map

A concept map is a graphic organizer that looks like a web with arrows connecting each circle. This type of map helps students identify a main concept as well as sub-concepts. It can be used to help visually organize thoughts as well as illustrate hierarchical information.

There are a variety of ways this type of organizer can be used in the classroom. Students can show relationships between specific concepts, characters in a story, or even vocabulary words. Many teachers like to use it to assess students’ prior knowledge on a topic.

A T-chart is a graphic organizer that is used to compare and contrast two different things. Students can use a T-chart to make comparisons related to a variety of topics or subjects; they can also be used in any content area or genre. For example, in social studies students can compare two different political candidates, then use the chart to help them in a class debate.

An idea web is a graphic organizer that is used for brainstorming and helps students organize ideas or concepts. Much like a concept map, an idea web is comprised of circles that are connected. This type of organizer is mainly used to help students brainstorm story ideas. For example, a topic is written in the center circle and students write in the details in the surrounding smaller circles.

A KWL chart is another popular graphic organizer, especially in the elementary classroom. This visual learning tool consists of three questions, each in their own column (‘what I K now’, ‘what I W ant to know’, and ‘what I L earned’). This is a great graphic organizer for activating prior knowledge.

This organizer is used both before and after learning a concept. Before learning, students write down “what they want to know” and “what they already know” about the topic. Then, after the concept is learned, students write down “what they learned” in the third column of the chart. This three-step process is great for developing a sense of purpose and helps students become more engaged in the topic they are learning.

How to Use Graphic Organizers Effectively

Graphic organizers can be a helpful learning tool, especially when they can guide students to a deeper understanding of what they are learning. To effectively support student learning, it’s important to always model how to use the organizer, as well as instruct students on why you choose the graphic organizer that you did for that specific topic.

For example, explain to students that you choose a Venn diagram as a starting point for an essay they will be writing because it will help them compare two characters in an organized manner before they begin writing their essay. When students understand what they are doing and why they are doing it, it will give them a sense of purpose.

Graphic organizers are great tools to meet the needs of all learners . By presenting information in a graphic format, you can easily make a lesson accessible to all students. To increase the effectiveness of a graphic organizer, always make sure to model beforehand and explain why you are using it and what you are using it for. Also, make sure that each graphic organizer that you choose is aligned with your learning goal; this will ensure that students will apply the information learned and develop a deeper understanding of the concept.

- #GraphicOrganizer

More in Classroom Management

The Importance of Art Class

In today’s technology-driven classrooms, art remains an important component of student development. Despite often being the first to be cut from…

Beyond Monkey Bars: The Vital Role of Recess in Child Development

Do students need recess? This question has been discussed for years among parents and educators….

Brain Breaks: The Science Behind it and the Benefits

The Science Behind Brain Breaks Most educators experience students’ glazed eyes, heads down,…

Classroom Attention-Getters to Use for Engaging Students

For many teachers, classroom management is a challenge. Without various strategies in your…

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident than in academia. From the quick scribbles of eager students to the inquisitive thoughts of renowned scholars, academic essays depict the power of the written word. These well-crafted writings propel ideas forward and expand the existing boundaries of human intellect.

What is an Academic Essay

An academic essay is a nonfictional piece of writing that analyzes and evaluates an argument around a specific topic or research question. It serves as a medium to share the author’s views and is also used by institutions to assess the critical thinking, research skills, and writing abilities of a students and researchers.

Importance of Academic Essays

4 main types of academic essays.

While academic essays may vary in length, style, and purpose, they generally fall into four main categories. Despite their differences, these essay types share a common goal: to convey information, insights, and perspectives effectively.

1. Expository Essay

2. Descriptive Essay

3. Narrative Essay

4. Argumentative Essay

Expository and persuasive essays mainly deal with facts to explain ideas clearly. Narrative and descriptive essays are informal and have a creative edge. Despite their differences, these essay types share a common goal ― to convey information, insights, and perspectives effectively.

Expository Essays: Illuminating ideas

An expository essay is a type of academic writing that explains, illustrates, or clarifies a particular subject or idea. Its primary purpose is to inform the reader by presenting a comprehensive and objective analysis of a topic.

By breaking down complex topics into digestible pieces and providing relevant examples and explanations, expository essays allow writers to share their knowledge.

What are the Key Features of an Expository Essay

Provides factual information without bias

Presents multiple viewpoints while maintaining objectivity

Uses direct and concise language to ensure clarity for the reader

Composed of a logical structure with an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion

When is an expository essay written.

1. For academic assignments to evaluate the understanding of research skills.

2. As instructional content to provide step-by-step guidance for tasks or problem-solving.

3. In journalism for objective reporting in news or investigative pieces.

4. As a form of communication in the professional field to convey factual information in business or healthcare.

How to Write an Expository Essay

Expository essays are typically structured in a logical and organized manner.

1. Topic Selection and Research

- Choose a topic that can be explored objectively

- Gather relevant facts and information from credible sources

- Develop a clear thesis statement

2. Outline and Structure

- Create an outline with an introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion

- Introduce the topic and state the thesis in the introduction

- Dedicate each body paragraph to a specific point supporting the thesis

- Use transitions to maintain a logical flow

3. Objective and Informative Writing

- Maintain an impartial and informative tone

- Avoid personal opinions or biases

- Support points with factual evidence, examples, and explanations

4. Conclusion

- Summarize the key points

- Reinforce the significance of the thesis

Descriptive Essays: Painting with words

Descriptive essays transport readers into vivid scenes, allowing them to experience the world through the writer ‘s lens. These essays use rich sensory details, metaphors, and figurative language to create a vivid and immersive experience . Its primary purpose is to engage readers’ senses and imagination.

It allows writers to demonstrate their ability to observe and describe subjects with precision and creativity.

What are the Key Features of Descriptive Essay

Employs figurative language and imagery to paint a vivid picture for the reader

Demonstrates creativity and expressiveness in narration

Includes close attention to detail, engaging the reader’s senses

Engages the reader’s imagination and emotions through immersive storytelling using analogies, metaphors, similes, etc.

When is a descriptive essay written.

1. Personal narratives or memoirs that describe significant events, people, or places.

2. Travel writing to capture the essence of a destination or experience.

3. Character sketches in fiction writing to introduce and describe characters.

4. Poetry or literary analyses to explore the use of descriptive language and imagery.

How to Write a Descriptive Essay

The descriptive essay lacks a defined structural requirement but typically includes: an introduction introducing the subject, a thorough description, and a concluding summary with insightful reflection.

1. Subject Selection and Observation

- Choose a subject (person, place, object, or experience) to describe

- Gather sensory details and observations

2. Engaging Introduction

- Set the scene and provide the context

- Use of descriptive language and figurative techniques

3. Descriptive Body Paragraphs

- Focus on specific aspects or details of the subject

- Engage the reader ’s senses with vivid imagery and descriptions

- Maintain a consistent tone and viewpoint

4. Impactful Conclusion

- Provide a final impression or insight

- Leave a lasting impact on the reader

Narrative Essays: Storytelling in Action

Narrative essays are personal accounts that tell a story, often drawing from the writer’s own experiences or observations. These essays rely on a well-structured plot, character development, and vivid descriptions to engage readers and convey a deeper meaning or lesson.

What are the Key features of Narrative Essays

Written from a first-person perspective and hence subjective

Based on real personal experiences

Uses an informal and expressive tone

Presents events and characters in sequential order

When is a narrative essay written.

It is commonly assigned in high school and college writing courses to assess a student’s ability to convey a meaningful message or lesson through a personal narrative. They are written in situations where a personal experience or story needs to be recounted, such as:

1. Reflective essays on significant life events or personal growth.

2. Autobiographical writing to share one’s life story or experiences.

3. Creative writing exercises to practice narrative techniques and character development.

4. College application essays to showcase personal qualities and experiences.

How to Write a Narrative Essay

Narrative essays typically follow a chronological structure, with an introduction that sets the scene, a body that develops the plot and characters, and a conclusion that provides a sense of resolution or lesson learned.

1. Experience Selection and Reflection

- Choose a significant personal experience or event

- Reflect on the impact and deeper meaning

2. Immersive Introduction

- Introduce characters and establish the tone and point of view

3. Plotline and Character Development

- Advance the plot and character development through body paragraphs

- Incorporate dialog , conflict, and resolution

- Maintain a logical and chronological flow

4. Insightful Conclusion

- Reflect on lessons learned or insights gained

- Leave the reader with a lasting impression

Argumentative Essays: Persuasion and Critical Thinking

Argumentative essays are the quintessential form of academic writing in which writers present a clear thesis and support it with well-researched evidence and logical reasoning. These essays require a deep understanding of the topic, critical analysis of multiple perspectives, and the ability to construct a compelling argument.

What are the Key Features of an Argumentative Essay?

Logical and well-structured arguments

Credible and relevant evidence from reputable sources

Consideration and refutation of counterarguments

Critical analysis and evaluation of the issue

When is an argumentative essay written.

Argumentative essays are written to present a clear argument or stance on a particular issue or topic. In academic settings they are used to develop critical thinking, research, and persuasive writing skills. However, argumentative essays can also be written in various other contexts, such as:

1. Opinion pieces or editorials in newspapers, magazines, or online publications.

2. Policy proposals or position papers in government, nonprofit, or advocacy settings.

3. Persuasive speeches or debates in academic, professional, or competitive environments.

4. Marketing or advertising materials to promote a product, service, or idea.

How to write an Argumentative Essay

Argumentative essays begin with an introduction that states the thesis and provides context. The body paragraphs develop the argument with evidence, address counterarguments, and use logical reasoning. The conclusion restates the main argument and makes a final persuasive appeal.

- Choose a debatable and controversial issue

- Conduct thorough research and gather evidence and counterarguments

2. Thesis and Introduction

- Craft a clear and concise thesis statement

- Provide background information and establish importance

3. Structured Body Paragraphs

- Focus each paragraph on a specific aspect of the argument

- Support with logical reasoning, factual evidence, and refutation

4. Persuasive Techniques

- Adopt a formal and objective tone

- Use persuasive techniques (rhetorical questions, analogies, appeals)

5. Impactful Conclusion

- Summarize the main points

- Leave the reader with a strong final impression and call to action

To learn more about argumentative essay, check out this article .

5 Quick Tips for Researchers to Improve Academic Essay Writing Skills

Use clear and concise language to convey ideas effectively without unnecessary words

Use well-researched, credible sources to substantiate your arguments with data, expert opinions, and scholarly references

Ensure a coherent structure with effective transitions, clear topic sentences, and a logical flow to enhance readability

To elevate your academic essay, consider submitting your draft to a community-based platform like Open Platform for editorial review

Review your work multiple times for clarity, coherence, and adherence to academic guidelines to ensure a polished final product

By mastering the art of academic essay writing, researchers and scholars can effectively communicate their ideas, contribute to the advancement of knowledge, and engage in meaningful scholarly discourse.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![what is a graphic in an essay What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers