Memory Writing Prompts: Dive into Reflective Narratives

My name is Debbie, and I am passionate about developing a love for the written word and planting a seed that will grow into a powerful voice that can inspire many.

What are Memory Writing Prompts?

How memory writing prompts can deepen reflective narratives, the benefits of engaging with memory writing prompts, how to use memory writing prompts to spark reflective writing, memory writing prompts for reflective writing, examples of memory writing prompts to get started, tips for crafting compelling reflective narratives using memory writing prompts, enhancing self-reflection through regular memory writing practice, frequently asked questions, in conclusion.

Memory writing prompts are thought-provoking cues designed to help you access and explore the depths of your memories. As human beings, our minds store a vast amount of experiences and emotions that shape who we are. These prompts serve as triggers, sparking our recollection and allowing us to delve into our past.

Whether you’re looking to preserve cherished moments, ignite your creativity, or simply explore your own personal narrative, memory writing prompts can be a valuable tool. They can help you unlock forgotten memories, unearth details long lost, and provide a space for self-reflection.

- Memory writing prompts encourage introspection and self-discovery.

- They offer an opportunity to explore personal anecdotes, moments of growth, or life-changing events.

- Using these prompts can enhance storytelling abilities and writing skills, allowing you to express yourself more vividly on paper.

So, whenever you feel stuck or want to embark on a journey through your own memories, try out these prompts. They can take various forms, ranging from questions about significant individuals in your life to nostalgic descriptions of special places. Let your memories flow and allow your writing to capture the essence of your experiences.

Memory writing prompts offer a powerful tool to enhance the depth and richness of your reflective narratives. By tapping into personal memories and experiences, these prompts encourage you to delve into the nuances of life, adding layers of authenticity and emotional connection to your writing. Whether you are a seasoned writer or just starting to explore the art of storytelling, memory prompts can ignite your creativity and bring your narratives to life.

One of the key benefits of using memory prompts is their ability to activate vivid details and sensory imagery. By prompting you to recall specific moments or emotions from your past, these prompts help you re-engage with your memories on a deeper level. As you write about these experiences, you naturally begin to incorporate sensory language, painting a more vivid picture for your readers. This not only creates a more engaging narrative but also allows your audience to better connect with your story on an emotional level.

Furthermore, memory prompts provide a framework for introspection and self-reflection. Through intentional writing exercises, you can explore the meaning and significance of past events, gaining new insights and understanding. When you revisit your memories and connect them to your current thoughts and emotions, you invite a deeper level of self-awareness and personal growth. Additionally, the act of writing about your memories can offer catharsis and healing, allowing you to process and make sense of challenging or transformative experiences.

Incorporating memory writing prompts into your writing practice can be a transformative experience. By accessing your personal memories and infusing them into your narratives, you can enrich your storytelling, uncover new perspectives, and foster self-growth. So, grab your pen, choose a memory prompt, and prepare to embark on a captivating journey of self-discovery through reflective narratives.

Memory writing prompts offer an incredible opportunity to unlock a treasure trove of forgotten memories and enrich our lives in numerous ways. Whether you’re seeking therapeutic benefits or a creative outlet, engaging with these prompts can bring about positive changes in your overall well-being. Here are some of the key advantages of incorporating memory writing prompts into your daily routine:

- Self-reflection and personal growth: Writing about our memories is a powerful tool for self-reflection. It allows us to revisit past experiences, analyze them from a new perspective, and gain insights into our own personal growth. Reflecting on our memories helps us better understand our emotions, behaviors, and thought processes.

- Preservation of personal history: Our memories make up the fabric of who we are. By engaging with memory writing prompts, we can capture our life stories, preserving them for future generations. These written accounts provide a valuable legacy that helps our loved ones understand the depth and richness of our lives.

- Improved mental well-being: Writing about memories has therapeutic benefits, aiding in the processing of emotions and stress reduction. Engaging with writing prompts can be cathartic, allowing us to release pent-up feelings and gain a sense of closure. Additionally, writing stimulates our cognitive functions, improving memory recall and overall mental acuity.

Incorporating memory writing prompts into your daily routine can be an enlightening and fulfilling experience. By delving into your past, you can uncover hidden facets of your identity, gain new perspectives, and find solace in revisiting long-forgotten experiences. So grab a pen, find a quiet space, and let the power of memory writing prompts guide you on a transformative journey of self-discovery and reflection!

Reflective writing allows us to explore our memories, thoughts, and experiences in a meaningful way. It enables us to gain insights, process emotions, and gain a deeper understanding of ourselves. Memory writing prompts can be a powerful tool to ignite this reflective process. Here are some tips on how to effectively use memory writing prompts to spark your reflective writing:

- Select meaningful prompts: Choose memory writing prompts that resonate with you personally. Whether it’s a specific event, a significant person, or a place that holds special memories, pick prompts that evoke emotions and offer opportunities for self-reflection.

- Create a safe and comfortable writing space: Find a quiet place where you can write without distractions. Make sure you have a comfortable chair, good lighting, and all the tools you need to jot down your thoughts. Creating a cozy and relaxed writing environment can help you delve deeper into your reflections.

- Set aside dedicated time: Reflective writing requires time and focus. Dedicate a specific time slot each day or week to engage in this practice. Whether it’s early morning when your mind is fresh or before bed when you can unwind, find a time that works best for you, and stick to it.

By using memory writing prompts, we embark on a journey of self-discovery, enabling us to gain insights, find closure, and even heal emotional wounds. Reflective writing serves as a medium to express ourselves, understand our experiences better, and ultimately grow as individuals. So, grab your pen and paper, or open up a blank document, and let your memories guide you towards a deeper level of self-reflection and understanding.

Memory writing is a powerful tool that helps us revisit our past experiences and create a meaningful narrative. If you’re looking to get started with memory writing, here are some unique and creative prompts to spark your imagination:

- A Childhood Adventure: Recall an exciting adventure from your childhood. Describe the sights, sounds, and emotions you experienced during this memorable moment.

- A Special Relationship: Write about a person who has had a significant impact on your life. Share anecdotes, experiences, and lessons learned from this unique relationship.

- A Place of Solitude: Take yourself back to a place where you found peace and tranquility. Describe the setting, the sensations it evoked, and the emotions you felt in that moment.

Furthermore, you can explore writing prompts like:

- A Life-Changing Decision: Reflect on a decision that altered the course of your life. Explain the factors that influenced your choice and how it has shaped you into the person you are today.

- A Hilarious Mishap: Recount a funny incident from your life that still brings a smile to your face. Share the details, the unexpected twists, and the comedic value of this unforgettable event.

- A Lesson from Nature: Connect with the natural world and recount a moment where you learned a valuable lesson from the elements around you. Describe the setting, the lesson learned, and how it impacted your perspective.

These prompts are meant to ignite your memory and unlock a treasure trove of stories within. Remember, every memory holds significance, no matter how small or insignificant it may seem at first glance. Happy writing!

Reflective narratives can be powerful tools for self-reflection and personal growth. By using memory writing prompts, you can tap into your past experiences and delve deep into cherished memories or significant events. Here are some tips to help you craft compelling narratives that will captivate your readers and evoke genuine emotions:

1. Identify a memorable prompt: The first step is to choose a memory writing prompt that resonates with you. It could be a specific question about a significant milestone, a challenging moment, or a joyful memory. Select a prompt that sparks your interest and ignites your passion to explore further.

2. Bring your memory to life: Once you’ve selected a memory prompt, it’s time to immerse your readers in the experience. Use descriptive language to paint a vivid picture and engage their senses. You want your readers to feel like they are present in the moment with you. Be specific and precise in your descriptions, focusing on sights, sounds, smells, and even the way you felt physically and emotionally.

3. Reflect on the significance: A compelling reflective narrative goes beyond simply recounting an event; it dives into the deeper meaning behind it. Take the time to reflect on how this memory has impacted your life, changed your perspective, or influenced your decisions. Share your insights and lessons learned, allowing your readers to connect with your personal growth journey.

4. Be honest and vulnerable: Authenticity is key when crafting reflective narratives. Don’t shy away from sharing your true emotions and vulnerabilities. Being open and honest will create a genuine connection with your readers, making your narrative more relatable and impactful.

5. Structure your narrative: Organize your narrative in a logical and coherent manner. Consider using an introduction to set the stage and to capture your readers’ attention. Use paragraphs to separate different aspects of your memory, and utilize transitions to guide your readers smoothly from one idea to the next. Finally, wrap up your narrative with a meaningful conclusion that leaves a lasting impression on your audience.

By following these tips and infusing your reflective narrative with your unique voice, you can create a compelling piece that not only sheds light on your past but also resonates with others, sparking their own introspection and personal growth. Embrace the power of memory writing prompts and let your narratives take your readers on a transformative journey.

Self-reflection is a powerful practice that allows us to understand ourselves better, learn from past experiences, and make positive changes in our lives. One effective way to enhance self-reflection is through regular memory writing practice. By engaging in this simple yet profound exercise, we can delve deeper into our thoughts, emotions, and memories, gaining valuable insights along the way.

A regular memory writing practice involves setting aside dedicated time each day or week to write about significant events, experiences, or moments that have impacted us. This could range from personal milestones and achievements to challenging situations and lessons learned. The act of writing not only serves as an outlet for self-expression, but it also helps us organize our thoughts and reflect on our past with clarity.

So how can regular memory writing practice enhance self-reflection? Here are a few key ways:

- Increased self-awareness: Through the process of writing about our memories, we become more aware of our emotions, reactions, and thought patterns. This heightened self-awareness allows us to identify behavioral patterns, triggers, and areas where personal growth is needed.

- Deepened understanding: By revisiting past experiences and examining them from various angles, we gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and the events that have shaped us. Writing helps us process complex emotions, analyze our actions, and discover underlying motivations, enabling personal development and growth.

- Enhanced problem-solving: Memory writing practice enables us to evaluate past challenges and the strategies used to overcome them. By reflecting on our decision-making and problem-solving processes, we can identify effective approaches and avoid repeating mistakes in the future.

Q: What are memory writing prompts? A: Memory writing prompts are thought-provoking questions or prompts that encourage you to reflect on past experiences and memories. They serve as inspiration for writing reflective narratives that allow you to explore and capture the depth of your memories.

Q: How do memory writing prompts work? A: Memory writing prompts work by triggering memories and emotions related to a specific moment or event. By asking questions that recall details or evoke certain feelings, these prompts help you tap into your memory bank and produce more honest and vivid narratives.

Q: Why should I use memory writing prompts? A: Memory writing prompts can be highly beneficial for numerous reasons. Firstly, they provide an opportunity for self-reflection and personal growth. Engaging with memories in writing allows you to better understand your experiences, learn from them, and gain new insights. Additionally, memory writing prompts can inspire creativity, improve writing skills , and serve as a therapeutic practice for your mental well-being.

Q: Who can benefit from using memory writing prompts? A: Anyone can benefit from using memory writing prompts. Whether you’re an aspiring writer looking to enhance your storytelling abilities, an individual seeking self-reflection and personal growth, or simply someone wanting to explore your memories in a meaningful way, memory writing prompts offer an accessible and effective tool.

Q: How can I use memory writing prompts effectively? A: To use memory writing prompts effectively, find a quiet and comfortable space where you feel inspired. Select a prompt that resonates with you or choose one randomly. Allow yourself to dive into your memories, recalling specific details and sensations associated with the prompt. Write freely and without judgment, letting the words flow as you explore the depth of your memory. Finally, read and reflect on what you’ve written, capturing any new insights or emotions that arise.

Q: Are there any tips for finding the right memory writing prompts? A: Absolutely! When looking for memory writing prompts, consider choosing prompts that are personal to you. Prompts related to significant life events, transformative moments, or emotionally charged experiences tend to evoke deeper reflections. Additionally, you can find memory writing prompts in books, online resources, or even create your own based on specific themes or time periods in your life.

Q: Can memory writing prompts be used for therapeutic purposes? A: Yes, memory writing prompts can indeed be used as a therapeutic practice. Engaging with memories and writing about them can help process emotions, heal past wounds , and reduce stress or anxiety. The act of reflection and storytelling can provide a sense of relief and offer an avenue for personal growth and self-discovery.

Q: Are memory writing prompts only for professional writers? A: Not at all! Memory writing prompts are not limited to professional writers. These prompts are for anyone looking to explore their memories, express themselves through writing, or engage in self-reflection. In fact, memory writing prompts can be particularly helpful for novice writers as they offer a structured starting point and guidance for crafting a compelling narrative.

Q: Can memory writing prompts be beneficial for preserving family histories? A: Definitely! Memory writing prompts serve as excellent tools for preserving family histories. By encouraging individuals to recall and document their past experiences, these prompts can help capture important family stories, traditions, and memories that might otherwise be lost over time. They enable future generations to connect with their roots and understand their family’s history on a deeper level.

Q: Where can I find memory writing prompts? A: You can find memory writing prompts in various places. Many books, both fiction and nonfiction, include prompts for self-reflection. Numerous websites and blogs also provide an array of memory writing prompts suited to different topics and styles. You can even create your own prompts inspired by specific memories or experiences, making the process more personalized and meaningful to you.

In conclusion, memory writing prompts offer a powerful tool for exploring our past and sharing our experiences through reflective narratives.

If I Had a Pot of Gold Writing Prompt: Imagine Riches and Adventures

Academic Insights: Revisiting Creative Writing in High School

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Reach out to us for sponsorship opportunities.

Welcome to Creative Writing Prompts

At Creative Writing Prompts, we believe in the power of words to shape worlds. Our platform is a sanctuary for aspiring writers, seasoned wordsmiths, and everyone. Here, storytelling finds its home, and your creative journey begins its captivating voyage.

© 2024 Creativewriting-prompts.com

Search for creative inspiration

19,890 quotes, descriptions and writing prompts, 4,964 themes

Memories - quotes and descriptions to inspire creative writing

- bonfire night

- celebration

- childhood memories

- good memories

- happy memories

- memory cards

- painful memories

- photographs

- revisiting a place

The best of my memories as far back and forwards as I may reach, form the golden thread of both soul and spine.

Memories us together bring both new fuel and fire, igniting an everlasting flame that speaks of magic and legend.

Memories of vivid hue come dancing in as if the wind was their favourite tune, as if they ever ready to samba.

Let us build our memories of the best times and forgive the worst, for our future is together. That's the way it is when you love someone, that's the way it has to be. There is no perfect, only perfect for one another.

The brain has little concept of time, and so the painful memory is experienced as a current event. This is why, once we have come to terms with them and gained new perspectives on what happened, it is important to move on and recall the happy times instead. This way you deal with them, disarm them, and choose real health for yourself. This way you love yourself and set yourself free.

My memories, the good and painful, are photographs - and I can choose what kind of album I wish to build.

The negative memories come with a cost, as addictive as they feel, once lessons are learnt there is nothing in them of value. The positive memories come as a friend with a picnic basket, they are good and nourishing, supportive and kind. And so I choose to build myself this way, letting the bad ones wander off on their own and encouraging the good ones to blossom and grow. This way I become confident, well balanced and in control of me, able to appreciate each moment as a gift and to see a positive future.

Each raindrop is the drop that kissed your skin in those days that we were together, me and you, my baby boy. Each one is the same because they sing of these such treasured memories, of the comforting love that remains and the hopes I hold for your future. And so, I love the rain better than photographs, for each one is a perfect moment.

Memories are often invoked by a fragrance, for me it is the smell of potatoes being fried in old oil - then I am at the seaside, shingle underfoot, fishing boats glistening in the afternoon sun. Yet for me the strongest memory, the one that feels most like being sunk into one of those alternative reality machines, is the giggle from baby Hans. It is more delicate than wind-chimes and just as chaotic, just as melodic. In those moments I have Clarissa once more, newborn, fresh, an unknown future before her.

The golden-brown gazelle became the caramel of my memories.

Sign in or sign up for Descriptionar i

Sign up for descriptionar i, recover your descriptionar i password.

Keep track of your favorite writers on Descriptionari

We won't spam your account. Set your permissions during sign up or at any time afterward.

🖋 50 Impactful Memoir Writing Prompts to Get You Writing TODAY

If you’re thinking about writing your memoir but facing a blank page, I have a few great memoir writing prompts that will get you writing TODAY . Let’s do this! ⚡️

Writer’s Block? Nah!

Creative writing prompts are useful tools for unlocking memories so you can get your life stories onto the page. I have a deep respect for the creative process, and I’m a fan of creative writing prompts because they work. They’re a diving board into your memories, helping to unlock past experiences you may have forgotten. If you struggle with writer’s block, memoir prompts are more like the well-meaning swim coach that gives you a purposeful nudge, right into the water. Once you’re in, you’re in! 🏊🏻♀️

Writing is an intuitive process, and this is especially true for memoir . It can be helpful to think about specific memories or moments in your life that were particularly meaningful to you. Other times, it can be helpful to focus on a specific theme or area of your life that you would like to explore in your writing. Don’t be surprised if you end up pivoting in a different direction, too. If you stay open, the story you are meant to write will reveal itself to you (this might sound silly, but it’s been true for me and all the books I’ve written ).

Creative writing prompts can be a warm-up to the actual writing, or the writing itself. You can decide the shape of your memoir once you know what you’re writing about and have generated enough material that can serve as the foundation of your memoir. You can smooth your prose and make everything cohere into a memoir everyone will want to read. 🤗

But right now? Get writing.

Using Creative Writing Prompts

Creative writing prompts and writing exercises that help you write your memoir by providing structure and ideas to get you started. They offer simple but thoughtful questions to help you excavate the stories that are wanting to be discovered. ⛏

Prompts can be as simple as asking you to describe a significant event in your life, or they can be open-ended, like asking you to write about a specific theme or feeling. Sometimes you’ll end up writing about something completely different than the memoir prompt, and that’s okay. Trust wherever it takes you.

The more writing you do, the more memories will get unlocked. Not only that, but a little bit of writing each day adds up to a lot of writing if you just keep going . And as an added bonus, you’ll be developing your writing skills with each prompt you write. 🏋🏻♀️

Memoirs are a great way to share your life story with the world. These prompts will help you get the most out of your writing and get your creative juices flowing.

Why Memoir Writing Matters

Memoir writing as a creative process that serves the writer and ultimately the reader. 🤓

For the writer, writing our personal narratives is a way to remember and process our own life experiences, to help us understand the significant events of our lives that helped shaped who we are. Writing these stories down can be a source of comfort and healing, providing a space to reflect on our past and make sense of our present. They offer a creative outlet for exploring our thoughts, feelings, and memories, and are a great way to connect with our past selves.

For the reader , memoirs can be a source of inspiration for others, offering a glimpse into someone else’s life and providing hope, motivation, and insight. I’ve always viewed memoir as proof that we’re not alone, that others have been through similar experiences and can relate to us. Great stories help us appreciate what we have in the present moment, and offer compassion for ourselves and others.

What are Some Good Memoir Topics to Write About?

Unless you already know what you want to write about in a memoir, and it can be difficult to know where to start. 🤷🏻♀️

Some good topics include your childhood, your family and friends, your education and career, your hobbies and interests, and any significant life events. These topics can also be used as creative writing prompts to help you get started on writing your memoir, even if you plan to focus on something different.

Most memoirs have a specific theme, which can help you frame your writing and your manuscript. Learn more about themes (vs topics) here , and download a printable list of themes that you can use while writing and revising your work.

Memoir Prompt Writing Tips

Before you begin, here are a few things to keep in mind.

Be honest and raw

Be honest with yourself and your writing. Don’t worry about putting on a show or looking perfect. Don’t start changing family members’ names because you’re worried they’ll get mad. Remember that no one is going to see your work at this stage unless you show it to them.

Experienced memoir writers know it takes many drafts to get to a polished manuscript, but you have to start at the beginning, and beginnings are usually pretty messy. Give yourself permission to write without any inhibitions — no censoring of your words or thoughts. Just get it down, and then decide what to do with it once you’re finished. If you really hate it or feel horribly embarrassed, you can always toss it out. But you probably won’t. 😉

Write by hand

When it comes to writing prompts, I’m a strong proponent of writing by hand. Before you panic, you’ll only be doing this for ten minutes (see below), and there’s a connection that’s made between the brain and the page when you write by hand. I do most of my writing on my computer — I’m a fast typist and a fast thinker, so I prefer to have my fingers on the keyboard … except when I’m responding to a prompt. Something important happens when we write by hand, and it gets missed when we’re on the computer or on our phones.

If you’re not convinced, try it for one week and see what happens.

Establish a daily writing practice

When you decide you’re going to write, a daily practice helps keep you on track. Have a writing process in place ensures that you get the writing done, and with each day that passes, you become a better writer.

Some memoir writers swear by Julia Cameron’s morning pages , which I love but don’t always have the time to do. My recommendation is to set the bar low — begin with writing ten minutes a day. Choose a prompt, set the timer, and keep your hand moving (thank you, Natalie Goldberg ). When the timer goes off, stop. You can spend another 10 minutes revising and reshaping the work, or you can put it aside to rest.

If you do this daily, you’ll have 365 individual vignettes by the end of the year (366 if it’s a leap year). Whether you choose to use them in your memoir is up to you, but these are excellent starting points and you’ll usually find some gems in there, which you can submit individually to literary magazines or string together into a collection of personal essays or narratives. If micro memoirs are your thing, I have some proposed writing schedules here that might help.

The most important thing is to write, and write daily. 📆

Tell a story and give us details

Every memoir tells a specific story the writers wants to share. Memoirs are not a recounting of every fact or statistic of your entire life like an autobiography or biography, but a glimpse into a particular moment.

I like to use the example of a photograph — sometimes what is outside the frame is just as important as what’s inside the frame. Use sensory details to bring us in the moment with you. What’s happening?

When you’re ready, and once you’ve selected the pieces you want to spend time on, you can revise your work. This will give you a chance to do a deeper dive into whatever it is that want to say, and shape the work for a reader. But again, you don’t have to worry about that now, just be assured that you can “fix” whatever you need to fix, later. 👩🏻🔧

Mem oir Writing Prompts & Ideas

Let’s get started! Use the following memoir prompts to get your creativity flowing. These open-ended prompts are very flexible so choose at random, switch them up, make them yours. Use them as a starting point, trust the process, and GO. 🏃🏻♀️

- The Alphabet Autobiography (similar to the abecedarian poetic form). You’ll write one sentence of line for each letter of the alphabet, from A to Z. Start with the letter A, and think about something (or someone) in your life that begins with A. It doesn’t have to “important” — don’t overthink it. Go with whatever comes up first, and keep going until you reach the end of the alphabet.

- Write about a family heirloom.

- What were the cartoon characters of your childhood, and which one did you identify with?

- Write about your first best friend.

- Not everyone has owned a pet, but we all have animal companions in some form. Think stuffed animal, class pet, a totem animal. Write about the first one that comes to mind.

- Write about a favorite teacher.

- What’s the first thing you did this morning?

- Have you ever had a near-death experience?

- Write about your first love.

- What was the most embarrassing thing that happened to you in high school?

- What is the best memory you have of a place you traveled to?

- When was the last time you saw a relative you don’t know very well? Tell us what you think about them. How are they related to you?

- Tell us about your favorite article of clothing. Where did you get it, why do you love it, what does it say about you?

- What was the first thing you ever bought yourself?

- What is your favorite gift you’ve ever given (or received)?

- Who do you love to spend time with? Why?

- Think of a time you lied.

- Think of a time when you stole something.

- Think of a time when you laughed so hard, you cried.

- Think of a time when you felt triumphant.

- Think of a time when you were completely and utterly in love.

- What was the worst day of your life?

- What’s your favorite season? Why?

- What’s your favorite holiday? Why?

- When were you the happiest you’ve ever been?

- When you were the saddest you’ve ever been?

- What is one of your most vivid memories of your parents?

- When was the last time you felt jealous?

- Write about a random act of kindness someone did for you.

- What is your favorite smell?

- Write about your name. What does it mean? Do you have a nickname? Does it suit you?

- What is something no one knows about you?

- Tell us a recipe that you make by heart. How did you learn it? How often do you make it?

- Did you have a comfort object growing up? What was it, and when did you need it?

- Write about a recurring dream.

- When you look in the mirror, what feature do you notice first? Write about that.

- What was the first place you ever traveled to?

- How has your worldview changed since you were a child?

- What was your first car?

- When was the last time you went swimming?

- What’s a job you would love to do?

- How many siblings do you have, and what are their names?

- Tell us about your favorite kind of sandwich.

- Write about your scars.

- What’s your go-to cocktail?

- How many times have you moved in your life?

- Describe the house you grew up in.

- How many tattoos and piercings do you have, and why did you get them?

- Write about the last time you were in nature, and what happened.

- Write about a camping trip.

More Great Resources

- Experiment with micro memoirs and establish a simple writing practice to help you write regularly.

- Read this post, 10 Tips on How to Write a Book About Your Life , for an overview of the writing process.

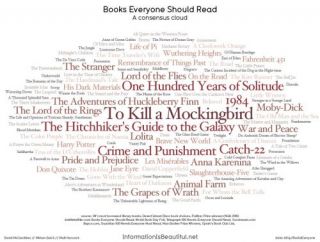

- Read this post, Top 10 Must-Read Books on How to Write a Memoir , which features books by some great writers of the genre.

- Want to know when I add more prompts? Join my newsletter ! 💌

How Memories are a Catalyst for Creative Prose

Words by thomas chisholm.

As the sum of a person’s history, the foundation of their identity, memories are inherently meaningful. They can be the reason why a person or a character behaves a certain way. They also work as creative vessels for narrative. An author unleashes a memory’s creative power through stream of consciousness writing and a recollected memory splinters the mind into different moments. A light shines on what was once forgotten. The stream of consciousness becomes a series of discoveries. When put to paper, the expanses that stream can cross and connect are endless.

In writing, a memory is a deviation from the forward momentum of a story. When a character recalls the past, an opportunity arises in the narrative for off-kilter prose. The crooked nature of an old memory creates an opportunity for embracing the surreal. The memory-deviation creates an opening for the stream of associations. But stream of consciousness writing takes the reader down a rabbit hole and exhausts them. There’s a fine line between astonishing prose and total self-indulgence. Utilizing it specifically in the depiction of memories prevents the prose from straying into indulgence. Showing a reader how unusual a mundane memory is can help them understand why it’s worth exploring.

Realism, though put on a pedestal, is still genre fiction. It’s often seen as the default mode of writing in literary fiction. We hold highbrow fiction to such a high standard. And as Zadie Smith once so dutifully pointed out: the genre is beyond its saturation point. In both fiction and nonfiction memory can be the vessel that breaks the mundane spell of realism’s supremacy. The past informs the present; deviating away from the main plot into the past is a standard device in storytelling. For the sake of prose, let memory be a way to break the spell.

I’m developing a short story about a kid who attends a funeral for the first time. When he tries to remember the deceased great uncle he barely knew, it comes through a little patchy. I let the memory take on a quality like magical realism:

I’m sitting on the floor with the TV at my back and Hot Wheels in my hands. I look up at the tall adults clouded in a fog of cigarette smoke. Uncle Howard cackles with faceless companions, beer cans in hand, all three of them have slicked over salt and pepper hair.

It’s not meant to be spooky or metaphorical. The memory is fuzzy because the character doesn’t know who the other adults are, and much like a dream, they don’t have faces. I’ve invited the surreal into the narrative and created a moment of intrigue for the reader.

Tom McCarthy’s Remainde r , the book our friend Zadie Smith once championed as a better path for contemporary novels, offers a different take on memory writing. In it, a man does everything he can to live his life in memory. He comes into money after a mysterious accident causes him severe brain trauma. He uses the money to recreate and sustain moments that felt meaningful for him. It requires him to buy buildings, renovate them, and hire actors who live in adjacent rooms and rotate through routines. All the while he floats in a euphoric sense of presence, in a reproduction of the past.

McCarthy exploits the absence of the present moment for an entire novel. He scratches a nostalgic itch: what happens when we can get that beloved moment back? It’s deliberately indulgent without being stream of consciousness.

Yet memory’s greatest strength is its associative nature—when it reaches out and brushes up against infinity. Authors use memory as a jumping off point to explore endless possibilities. W. G. Sebald offers an especially associative take on memory writing in his novel The Rings of Saturn . Association writing is how memory enters a stream of consciousness. Sebald tames the narrative impulse to expand outward without end by rooting his novel in a walking journey along the eastern coast of Britain. The Rings of Saturn successfully expands and contracts because it always returns to the same place: a man walking up the coast. In the following section from the novel, the main character sits on a beach and a memory triggers another about a dream:

[T]he storm . . . had broken over Southwold in the late afternoon. For a while, the topmost summit regions of this massif, dark as ink, glistened like the icefields of the Caucasus, and as I watched the glare fade I remembered that years before, in a dream, I had once walked the entire length of a mountain range just as remote and just as unfamiliar. It must have been a distance of a thousand miles or more, through ravines, gorges and valleys, across ridges, slopes and drifts, along the edges of great forests, over wastes of rock, shale and snow. And I recalled that in my dream, once I had reached the end of my journey, I looked back, and that it was six o’clock in the evening. The jagged peaks of the mountains I had left behind rose in almost fearful silhouette against a turquoise sky in which two or three pink clouds drifted.

In this one short section, Sebald blends geography and meteorology with personal experience, dreams, and landscape descriptions. His text creates a moment of dreamlike fusion; a network of infinite connections with unpredictable outcomes, reminding the reader of a world full of connections that we can access at any time.

Sebald’s narrative works so effortlessly because he anchors his ruminative text in a place . By doing this, his narrative can wander as far and wide as he can imagine, and keep the reader engaged, because it keeps returns to the geographic place of the trek. With his place always shifting, Sebald is able to repeat this cycle over and over again until he reaches the end of his journey. The place of Sebald’s text acts as a vessel for containing his associations within.

Without the set up of a walking trip, the novel would be a pulpy mess of freeform associations. Though beautiful and philosophically stimulating, it wouldn’t be much of a pleasure to read. Instead, Sebald gives his readers a tidy box containing the infinite nature of one human’s mind.

If your writing suffers from a lack of ideas, turning to specific memories can help immensely. Memory writing is exploratory and if it doesn’t result in an experimental piece worth developing, it will at least reveal a story worth telling.

Thomas Chisholm

Thomas Chisholm is a creative writer, editor, zine-maker, and an alumnus of The Evergreen State College. Though originally from the Metro-Detroit area, he’s called the lands and seas of Puget Sound home since 2009. Primarily residing in Seattle, he blogs about music at Three Imaginary Girls and is working on comics with a creative partner. His creative work has appeared in Inkwell and Vanishing Point Magazine .

Recent Posts

- EVIL RATS ON NO STAR LIVE

- An Interview with Hart Hanson

- An Interview with Marit Weisenberg

- The Next End

- April Staff Picks

- Contest Winners

- Creative Nonfiction

- Dually Noted

- Facts of Fiction

- Flash Fiction

- Literary Horoscopes

- Read-alongs

- Short Story

- Staff Picks

- Editor's Note

- Uncategorized

22 writing prompts that jog childhood memories

by Kim Kautzer | May 23, 2018 | Writing & Journal Prompts

My childhood memories are rich and varied.

I loved visiting my grandma’s apartment, with its fringed window shades and faint smell of eucalyptus. Her desk drawers, lined in green felt, spilled over with card decks, cocktail napkins, and golf tees. Every door in the house was fitted with wobbly crystal doorknobs. The bathroom smelled of Listerine.

My brother and I would sleep in the small bedroom off the kitchen—the very room our mom shared with her own brother growing up in the north side of Chicago.

I can picture myself reaching way down into Grandma’s frost-filled chest freezer for the ever-present box of Eskimo Pies. Her well-stocked pantry and doily-covered tabletops contained loads of delectable treats I was often denied at home: pastries, chocolate-covered marshmallow cookies, and delicate bowls of jellied orange sticks and other candy .

This was the 1960s, long before big-box stores came on the scene. Together Grandma and I would walk to the corner of Roscoe and Broadway, where we’d explore the wonders of Simon’s Drugstore, Heinemann’s Bakery, and Martha’s Candies.

Those childhood m emories of my grandma are largely synonymous with food.

In my mind’s eye, I can still picture driving from Illinois to Wisconsin beneath a canopy of crimson leaves against an blindingly blue sky. I remember Passover dinners with a million Jewish relatives in the basement of some wizened old uncle’s apartment building.

Other childhood memories recall the mysteries of new baby brothers coming on the scene, building a hideout among the branches of a fallen tree, and giving my best friend’s parakeet a ride down the stairs in her aqua Barbie convertible.

It’s good to write down our recollections . As vivid as the moment seems at the time, memories fade. These prompts will help jog them. This can be a great homeschool writing activity! Invite your older children to participate. They’re in closer proximity to their memories, and can usually remember the details more vividly.

There are no rules : Jot your thoughts in snippets or write them out diary-style. Either way, do your best to recall the sensory details that made the moment important, for it’s those little things that keep the memory alive.

Writing Prompts about Childhood Memories

- Who was your best childhood friend ? Write about some of the fun things you used to do together.

- Describe one of your earliest childhood memories . How old were you? What bits and pieces can you recall?

- When you were little, did you ever try to run away from home ? What made you want to leave? What did you pack? How far did you get?

- Can you remember your mom’s or grandmother’s kitchen ? Use sight and smell words to describe it.

- Describe the most unusual or memorable place you have lived.

- Did you have your own bedroom growing up, or did you share with a sibling? Describe your room.

- Were you shy as a child? Bossy? Obnoxious? Describe several of your childhood character traits . How did those qualities show themselves? Are you still that way today?

- What childhood memories of your mother and father do you have? Describe a couple of snapshot moments.

- Write about a holiday memory . Where did you go? What did you do? What foods do you remember?

- Describe your favorite hideaway .

- Did you attend a traditional school, or were you homeschooled? Describe a school-related memory .

- Think of a time when you did something you shouldn’t have done. Describe both the incident and the feelings they created.

- Have you ever needed stitches, broken a bone, or been hospitalized? Describe a childhood injury or illness .

- Do you have quirky or interesting relatives on your family tree? Describe one or two of them.

- Describe your most memorable family vacatio n . Where did you go? Did something exciting or unusual happen? Did you eat new or unique foods ?

- Books can be childhood friends. What were some of your favorites? Why were they special?

- Did you grow up with family traditions ? Describe one.

- Describe a game or activity you used to play with a sibling .

- What was your most beloved toy ? Describe its shape, appearance, and texture. What feelings come to mind when you think of that toy?

- Think of a childhood event that made you feel anxious or scared . Describe both the event itself and the feelings it stirred up.

- Write about some sayings, expressions, or advice you heard at home when you were growing up. Who said them? What did they mean? Do you use any of those expressions today?

- What are your happiest childhood memories ? Describe one event and the feelings associated with it.

I hope you’ll get much use out of these writing prompts about childhood memories. What’s one of your most vivid childhood memories? Share a snippet in the comments!

Let’s Stay Connected!

Subscribe to our newsletter.

- Gift Guides

- Reluctant or Struggling Writers

- Special Needs Writers

- Brainstorming Help

- Editing & Grading Help

- Encouragement for Moms

- Writing Games & Activities

- Writing for All Subjects

- Essays & Research Papers

- College Prep Writing

- Grammar & Spelling

- Writing Prompts

Recent Posts

- An exciting announcement!

- 10 Stumbling Blocks to Writing in Your Homeschool

- Help kids with learning challenges succeed at homeschool writing

- How to correct writing lessons without criticizing your child

63 Best Memoir Writing Prompts To Stoke Your Ideas

You’re writing a memoir. But you’re not sure what questions or life lessons you want to focus on.

Even if only family members and friends will read the finished book, you want to make it worth their time.

This isn’t just a whimsical collection of anecdotes from your life.

You want to convey something to your readers that will stay with them.

And maybe you want your memoir’s impact to serve as your legacy — a testament to how you made a small (or large) difference.

The collection of memoir questions in this post can help you create a legacy worth sharing.

So, if you don’t already have enough ideas for a memoir, read on.

A Strong Theme

Overcoming obstacles, emotional storytelling, satisfying ending, examples of good starting sentences for a memoir , 63 memoir writing prompts , what are the primary parts of a memoir.

Though similar to autobiographies, memoirs are less chronological and more impressionable – less historical and more relatable.

Resultantly, they’re structured differently.

With that in mind, let’s look at five elements that tie a memoir together, rendering it more enjoyable.

Biographies are histories that may not hew to a cohesive theme. But memoirs focus on inspiring and enlightening experiences and events.

As such, books in the genre promote a theme or idea that binds the highlighted happenings to an overarching reflection point or lesson.

Many people are super at sniffing out insincerity, and most folks prefer candidness.

So while exact dates and logistical facts may be off in a memoir, being raw and real with emotions, revelations, and relational impacts is vital. To put it colloquially: The best personal accounts let it all hang out.

People prefer inspiring stories. They want to read about people overcoming obstacles, standing as testaments to the tenacious nature of the human spirit. Why?

Because it engenders hope. If this person was able to achieve “x,” there’s a possibility I could, too. Furthermore, people find it comforting that they’re not the only ones who’ve faced seemingly insurmountable impediments.

Readers crave emotion. And for many of the stoic masses, books, plays, television shows, and films are their primary sources of sentimentality.

Historically, the best-performing memoirs are built on emotional frameworks that resonate with readers. The goal is to touch hearts, not just heads.

In a not-so-small way, memoirs are like romance books: Readers want a “happy” ending. So close strongly. Ensure the finale touches on the book’s central themes and emotional highlights.

End it with a smile and note of encouragement, leaving the audience satisfied and optimistic.

Use the following questions as memoir writing exercises . Choose those that immediately evoke memories that have stayed with you over the years.

Group them by theme — family, career, beliefs, etc. — and address at least one question a day.

For each question, write freely for around 300 to 400 words. You can always edit it later to tighten it up or add more content.

1. What is your earliest memory?

2. What have your parents told you about your birth that was unusual?

3. How well did you get along with your siblings, if you have any?

4. Which parent were you closest to growing up and why?

5. What parent or parental figure had the biggest influence on you growing up?

6. What is your happiest childhood memory?

7. What is your saddest or most painful childhood memory?

8. Did you have good parents? How did they show their love for you?

9. What words of theirs from your childhood do you remember most, and why?

10. What do you remember most about your parents’ relationship?

11. Were your parents together, or did they live apart? Did they get along?

12. How has your relationship with your parents affected your own love relationships?

13. Who or what did you want to be when you grew up?

14. What shows or movies influenced you most during your childhood?

15. What were your favorite books to read, and how did they influence you?

16. If you grew up in a religious household, how did you see “God”?

17. How did you think “God” saw you? Who influenced those beliefs?

18. Describe your spiritual journey from adolescence to the present?

19. Who was your first best friend? How did you become friends?

20. Who was your favorite teacher in elementary school, and why?

21. Did you fit in with any social group or clique in school? Describe your social life?

22. What were your biggest learning challenges in school (academic or social)?

23. Who was your first crush, and what drew you to them? How long did it last?

24. What was your favorite subject in school, and what did you love about it?

25. What do you wish you would have learned more about growing up?

26. What did you learn about yourself in high school? What was your biggest mistake?

27. What seemed normal to you growing up that now strikes you as messed up?

28. How old were you when you first moved away from home?

29. Who gave you your first kiss? And what do you remember most about it?

30. Who was your first love ? What do you remember most about them?

31. Was there ever a time in your life when you realized you weren’t straight?

32. Describe a memorable argument you had with one of your parents? How did it end?

33. Have you lost a parent? How did it happen, and how did their death affect you?

34. What was your first real job? What do you remember most about it?

35. How did you spend the money you earned with that job?

36. At what moment in your life did you feel most loved?

37. At what moment in your life did you feel most alone?

38. What do you remember most about your high school graduation? Did it matter?

39. What’s something you’ve done that you never thought you would do?

40. What has been the greatest challenge of your life up to this point?

41. What did you learn in college that has had a powerful influence on you?

42. How has your family’s financial situation growing up influenced you?

43. How has someone’s harsh criticism of you led you to an important realization?

44. Do you consider yourself a “good person”? Why or why not?

45. Who was the first person who considered you worth standing up for?

46. If you have children, whom did you trust with them when they were babies?

47. Did you have pets growing up? Did you feel close or attached to any of them?

More Related Articles

66 Horror Writing Prompts That Are Freaky As Hell

15 Common Grammar Mistakes That Kill Your Writing Credibility

61 Fantasy Writing Prompts To Stoke Your Creativity

48. Describe someone from your past whom you’d love to see again.

49. Do you have a lost love? If yes, describe them, how you met, and how you lost them.

50. Describe a moment when you made a fool of yourself and what it cost you.

51. What is something you learned later in life that you wish you’d learned as a child?

52. How do you want others to see you? What words come to mind?

53. What do you still believe now that you believed even as a child or as a teenager?

54. What do you no longer believe that you did believe as a child or teenager?

55. When have you alienated people by being vocal about your beliefs?

56. Are you as vocal about your beliefs as you were when you were a young adult ?

57. Are you haunted by the consequences of beliefs you’ve since abandoned?

58. How have your political beliefs changed since you were a teenager?

59. Have you ever joined a protest for a cause you believe in? Would you still?

60. How has technology shaped your life for the past 10 years?

61.Has your chosen career made you happy — or cost you and your family too much?

62. What comes to mind if someone asks you what you’re good at? Why does it matter?

63. How is your family unique? What makes you proudest when you think about them?

We’ve looked at the elements that make memoirs shine. Now, let’s turn our attention to one of the most important parts of a personal account: the opening sentence.

We’ve scoured some of the most successful, moving memoirs of all time to curate a list of memorable starting sentences. Notice how all of them hint at the theme of the book.

Let’s jump in.

1. “They called him Moishe the Beadle, as if his entire life he had never had a surname.” From Night, a first-hand account of the WWII Holocaust by Elie Wiesel

2. “My mother is scraping a piece of burned toast out of the kitchen window, a crease of annoyance across her forehead.” From Toast: The Story of a Boy’s Hunger, foodie Nigel Slater’s account of culinary events that shaped his life.

3. “Then there was the bad weather.” From A Moveable Feast , Ernest Hemingway’s telling of his years as an young expat in Paris

4. “You know those plants always trying to find the light?” From Over the Top: A Raw Journey of Self-Love by Queer Eye for the Straight Guy’s beloved star, Jonathan Van Ness

5. “What are you looking at me for? I didn’t come to stay.” From Maya Angelou’s masterpiece, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings , the story of persevering in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles

6. “I’m on Kauai, in Hawaii, today, August 5, 2005. It’s unbelievably clear and sunny, not a cloud in the sky.” From What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami, a memoir about the fluidity of running and writing

7. “The soil in Leitrim is poor, in places no more than an inch deep. ” From All Will be Well , Irish writer John McGahern’s recounting of his troubled childhood

8. “The past is beautiful because one never realizes an emotion at the time.” From Educated , Tara Westover’s engrossing account of her path from growing up in an uneducated survivalist family to earning a doctorate in intellectual history from Cambridge University

9. “I flipped through the CT scan images, the diagnosis obvious.” From When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi, the now-deceased doctor’s journey toward mortality after discovering he had terminal cancer

10. “Romantic love is the most important and exciting thing in the entire world.” From Everything I Know About Love by Dolly Alderton, a funny, light-hearted memoir about one woman’s amorous journey from teenager to twentysomething

Final Thoughts

These memoir topics should get ideas flooding into your mind. All you have to do, then, is let them out onto the page. The more you write, the easier it will be to choose the primary focus for your memoir. And the more fun you’ll have writing it.

That’s not to say it’ll be easy to create a powerful memoir. It won’t be. But the more clarity you have about its overall mission, the more easily the words will flow.

Enjoy these memoir writing exercises. And apply the same clarity of focus during the editing process. Your readers will thank you.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Privacy Policy

- Create a Website

- $1,000 Blog Tour

- Happiness Tour

- 5/11 Blog Tour

- Guest Posts

- Writing Prompts

- Writing Exercises

- Writing Tips

- Holiday Writing

- Writing Contest

- Comedy Channel

- Prompts eBook

- Kids Writing Book

- 9 to 5 Writer Book

- Writing Tips eBook

- Happiness Book

- TpT Reviews

- Read These Books

- Motivation Help

- Time Management

- Healthy Living

- Grades 9-10

- Grades 11-12

- First Grade

- Second Grade

- Third Grade

- Fourth Grade

- Fifth Grade

- 1,000 Character Writing Prompts

- 1,000 Creative Holiday Prompts

Free Creative Writing Prompts #13: Memory

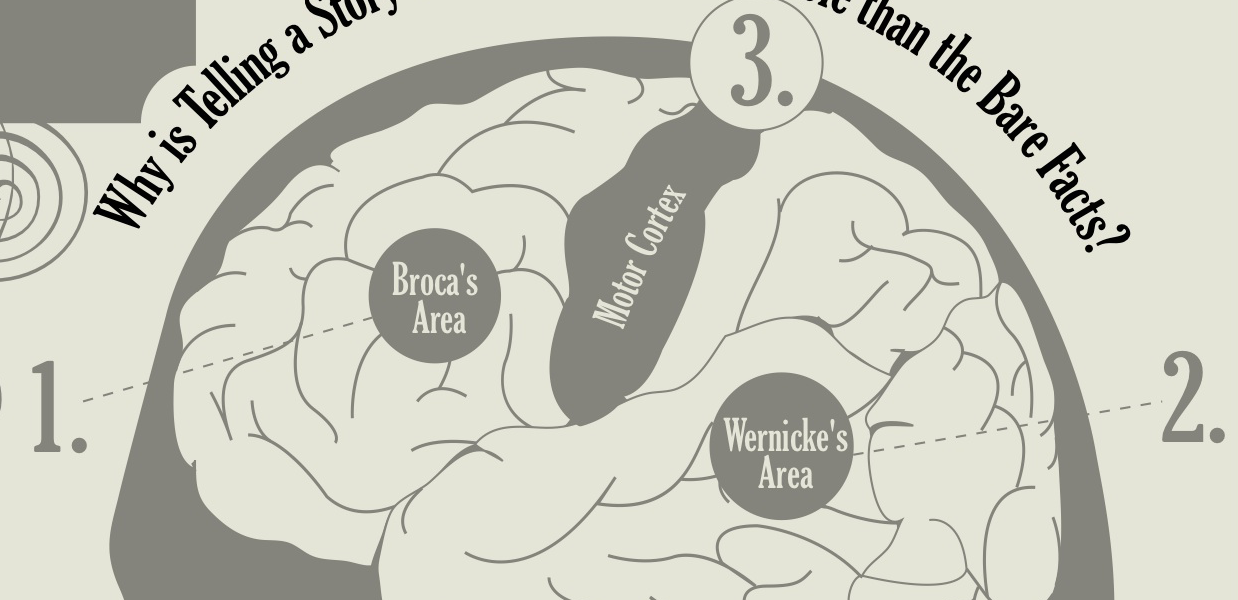

Memory. It can play tricks on us. It can fail us when we're down and out. It can save us when the pressure is on. I have a huge fascination with the brain and how it works. The people that are able to use their brains effectively can do such wonderful things in the world. And then there are those who avoid using their brains completely and settle into an instinct-filled life. Keeping hopeful memories alive is one way to keep that desire to use your brain. Aside from all of that positive hippie mumbo jumbo I always spout ;), the memory is a great place to draw from for your writing. Here are some free creative writing prompts about memory. Free Creative Writing Prompts: Memory

1. What is your earliest childhood memory? What do you think was going on around your memory that you don't quite remember? Would you have changed this memory if you could?

2. You have suddenly been given enhanced brain power and you can remember everything that's ever happened to you nearly at the same time. What do you remember that causes you to change how you behave currently? What are some lessons you learned that you promptly forgot?

3. You and a significant other are recounting the story of how you met to a couple of friends. How do your stories differ and explain why you think that is.

4. If you could change one memory for the better, what would it be and why? Go into extreme detail including the context and subtext of everything going on during this unfortunate memory.

5. Trace the origins of one of your habits. For example: Why do you kiss your hand and touch the roof of your car every time you go through a yellow light? Did you have a friend who started doing that and you followed her lead? Figure out when you started doing something that you now do all the time.

6. You have just gotten in a car accident and have complete and total amnesia. How do you cope with this and how do the people around you attempt to jog your memory back to working condition?

7. You have to deal with a parent who is suffering through Alzheimer's disease. What do you do to preserve the ailing memory of your mom or dad and how do you deal with the emotions that you're experiencing?

8. If you could forget one memory that haunts you, what would it be and why? Go into extreme detail including the context and subtext of everything going on during this memory. How would life change once you've forgotten it?

9. Create a story of how you enhanced your brain power over 100% using nutritional supplements, exercises, and a whole lot of hard work. Perhaps creating this story actually will improve your brain!

10. Remember back to an extremely happy time in your life. Write down as many details as you can remember about the time, including what you were wearing, how the room was decorated, what it smelled like, etc. It's not always easy to remember a lot of stuff from your past. Here's a trick. Remember something that occurred around the same time as the memory you're trying to dig up. Especially something emotional. Try to remember very specific things about a teacher you had, or a girl you like, etc. This can help to trigger your brain to look in that time period and you may come up with exactly what you were looking for. Until next time...happy writing! Bonus Prompt - If you could switch brains with any one person who would it be? Keep in mind (ha!) that you may lose your memories and they would be replaced by this person's.

Related Articles to Free Creative Writing Prompts Free Creative Writing Prompts from the Heart, Part 1 Free Creative Writing Prompts #2: Love Creative Writing Exercises #2: Relaxation

Done with this page? Go back to Creative Writing Prompts.

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

- Latest Posts

Write a Story Based on These Prompts or This Article!

Use the above prompts or article as inspiration to write a story or other short piece.

Enter Your Title

Add a Picture/Graphic Caption (optional)

Click here to upload more images (optional)

Author Information (optional)

To receive credit as the author, enter your information below.

Submit Your Contribution

- Check box to agree to these submission guidelines .

- I am at least 16 years of age.

- I understand and accept the privacy policy .

- I understand that you will display my submission on your website.

(You can preview and edit on the next page)

What Other Visitors Have Said

Click below to see contributions from other visitors to this page...

'Lost in my own mind' Not rated yet It was a cold winter day, My mother and I decided to go over to my grandparents to relax next to their fire place. I grabbed my jacket and gloves as …

Click here to write your own.

- What's New?

ADDITIONAL INFO

What Is Creative Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 20 Examples)

Creative writing begins with a blank page and the courage to fill it with the stories only you can tell.

I face this intimidating blank page daily–and I have for the better part of 20+ years.

In this guide, you’ll learn all the ins and outs of creative writing with tons of examples.

What Is Creative Writing (Long Description)?

Creative Writing is the art of using words to express ideas and emotions in imaginative ways. It encompasses various forms including novels, poetry, and plays, focusing on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary tropes.

Table of Contents

Let’s expand on that definition a bit.

Creative writing is an art form that transcends traditional literature boundaries.

It includes professional, journalistic, academic, and technical writing. This type of writing emphasizes narrative craft, character development, and literary tropes. It also explores poetry and poetics traditions.

In essence, creative writing lets you express ideas and emotions uniquely and imaginatively.

It’s about the freedom to invent worlds, characters, and stories. These creations evoke a spectrum of emotions in readers.

Creative writing covers fiction, poetry, and everything in between.

It allows writers to express inner thoughts and feelings. Often, it reflects human experiences through a fabricated lens.

Types of Creative Writing

There are many types of creative writing that we need to explain.

Some of the most common types:

- Short stories

- Screenplays

- Flash fiction

- Creative Nonfiction

Short Stories (The Brief Escape)

Short stories are like narrative treasures.

They are compact but impactful, telling a full story within a limited word count. These tales often focus on a single character or a crucial moment.

Short stories are known for their brevity.

They deliver emotion and insight in a concise yet powerful package. This format is ideal for exploring diverse genres, themes, and characters. It leaves a lasting impression on readers.

Example: Emma discovers an old photo of her smiling grandmother. It’s a rarity. Through flashbacks, Emma learns about her grandmother’s wartime love story. She comes to understand her grandmother’s resilience and the value of joy.

Novels (The Long Journey)

Novels are extensive explorations of character, plot, and setting.

They span thousands of words, giving writers the space to create entire worlds. Novels can weave complex stories across various themes and timelines.

The length of a novel allows for deep narrative and character development.

Readers get an immersive experience.

Example: Across the Divide tells of two siblings separated in childhood. They grow up in different cultures. Their reunion highlights the strength of family bonds, despite distance and differences.

Poetry (The Soul’s Language)

Poetry expresses ideas and emotions through rhythm, sound, and word beauty.

It distills emotions and thoughts into verses. Poetry often uses metaphors, similes, and figurative language to reach the reader’s heart and mind.

Poetry ranges from structured forms, like sonnets, to free verse.

The latter breaks away from traditional formats for more expressive thought.

Example: Whispers of Dawn is a poem collection capturing morning’s quiet moments. “First Light” personifies dawn as a painter. It brings colors of hope and renewal to the world.

Plays (The Dramatic Dialogue)

Plays are meant for performance. They bring characters and conflicts to life through dialogue and action.

This format uniquely explores human relationships and societal issues.

Playwrights face the challenge of conveying setting, emotion, and plot through dialogue and directions.

Example: Echoes of Tomorrow is set in a dystopian future. Memories can be bought and sold. It follows siblings on a quest to retrieve their stolen memories. They learn the cost of living in a world where the past has a price.

Screenplays (Cinema’s Blueprint)

Screenplays outline narratives for films and TV shows.

They require an understanding of visual storytelling, pacing, and dialogue. Screenplays must fit film production constraints.

Example: The Last Light is a screenplay for a sci-fi film. Humanity’s survivors on a dying Earth seek a new planet. The story focuses on spacecraft Argo’s crew as they face mission challenges and internal dynamics.

Memoirs (The Personal Journey)

Memoirs provide insight into an author’s life, focusing on personal experiences and emotional journeys.

They differ from autobiographies by concentrating on specific themes or events.

Memoirs invite readers into the author’s world.

They share lessons learned and hardships overcome.

Example: Under the Mango Tree is a memoir by Maria Gomez. It shares her childhood memories in rural Colombia. The mango tree in their yard symbolizes home, growth, and nostalgia. Maria reflects on her journey to a new life in America.

Flash Fiction (The Quick Twist)

Flash fiction tells stories in under 1,000 words.

It’s about crafting compelling narratives concisely. Each word in flash fiction must count, often leading to a twist.

This format captures life’s vivid moments, delivering quick, impactful insights.

Example: The Last Message features an astronaut’s final Earth message as her spacecraft drifts away. In 500 words, it explores isolation, hope, and the desire to connect against all odds.

Creative Nonfiction (The Factual Tale)

Creative nonfiction combines factual accuracy with creative storytelling.

This genre covers real events, people, and places with a twist. It uses descriptive language and narrative arcs to make true stories engaging.

Creative nonfiction includes biographies, essays, and travelogues.

Example: Echoes of Everest follows the author’s Mount Everest climb. It mixes factual details with personal reflections and the history of past climbers. The narrative captures the climb’s beauty and challenges, offering an immersive experience.

Fantasy (The World Beyond)

Fantasy transports readers to magical and mythical worlds.

It explores themes like good vs. evil and heroism in unreal settings. Fantasy requires careful world-building to create believable yet fantastic realms.

Example: The Crystal of Azmar tells of a young girl destined to save her world from darkness. She learns she’s the last sorceress in a forgotten lineage. Her journey involves mastering powers, forming alliances, and uncovering ancient kingdom myths.

Science Fiction (The Future Imagined)

Science fiction delves into futuristic and scientific themes.

It questions the impact of advancements on society and individuals.

Science fiction ranges from speculative to hard sci-fi, focusing on plausible futures.

Example: When the Stars Whisper is set in a future where humanity communicates with distant galaxies. It centers on a scientist who finds an alien message. This discovery prompts a deep look at humanity’s universe role and interstellar communication.

Watch this great video that explores the question, “What is creative writing?” and “How to get started?”:

What Are the 5 Cs of Creative Writing?

The 5 Cs of creative writing are fundamental pillars.

They guide writers to produce compelling and impactful work. These principles—Clarity, Coherence, Conciseness, Creativity, and Consistency—help craft stories that engage and entertain.

They also resonate deeply with readers. Let’s explore each of these critical components.

Clarity makes your writing understandable and accessible.

It involves choosing the right words and constructing clear sentences. Your narrative should be easy to follow.

In creative writing, clarity means conveying complex ideas in a digestible and enjoyable way.

Coherence ensures your writing flows logically.

It’s crucial for maintaining the reader’s interest. Characters should develop believably, and plots should progress logically. This makes the narrative feel cohesive.

Conciseness

Conciseness is about expressing ideas succinctly.

It’s being economical with words and avoiding redundancy. This principle helps maintain pace and tension, engaging readers throughout the story.

Creativity is the heart of creative writing.

It allows writers to invent new worlds and create memorable characters. Creativity involves originality and imagination. It’s seeing the world in unique ways and sharing that vision.

Consistency

Consistency maintains a uniform tone, style, and voice.

It means being faithful to the world you’ve created. Characters should act true to their development. This builds trust with readers, making your story immersive and believable.

Is Creative Writing Easy?

Creative writing is both rewarding and challenging.

Crafting stories from your imagination involves more than just words on a page. It requires discipline and a deep understanding of language and narrative structure.

Exploring complex characters and themes is also key.

Refining and revising your work is crucial for developing your voice.

The ease of creative writing varies. Some find the freedom of expression liberating.

Others struggle with writer’s block or plot development challenges. However, practice and feedback make creative writing more fulfilling.

What Does a Creative Writer Do?

A creative writer weaves narratives that entertain, enlighten, and inspire.

Writers explore both the world they create and the emotions they wish to evoke. Their tasks are diverse, involving more than just writing.

Creative writers develop ideas, research, and plan their stories.

They create characters and outline plots with attention to detail. Drafting and revising their work is a significant part of their process. They strive for the 5 Cs of compelling writing.

Writers engage with the literary community, seeking feedback and participating in workshops.

They may navigate the publishing world with agents and editors.

Creative writers are storytellers, craftsmen, and artists. They bring narratives to life, enriching our lives and expanding our imaginations.

How to Get Started With Creative Writing?

Embarking on a creative writing journey can feel like standing at the edge of a vast and mysterious forest.

The path is not always clear, but the adventure is calling.

Here’s how to take your first steps into the world of creative writing:

- Find a time of day when your mind is most alert and creative.

- Create a comfortable writing space free from distractions.

- Use prompts to spark your imagination. They can be as simple as a word, a phrase, or an image.

- Try writing for 15-20 minutes on a prompt without editing yourself. Let the ideas flow freely.

- Reading is fuel for your writing. Explore various genres and styles.

- Pay attention to how your favorite authors construct their sentences, develop characters, and build their worlds.

- Don’t pressure yourself to write a novel right away. Begin with short stories or poems.

- Small projects can help you hone your skills and boost your confidence.

- Look for writing groups in your area or online. These communities offer support, feedback, and motivation.

- Participating in workshops or classes can also provide valuable insights into your writing.

- Understand that your first draft is just the beginning. Revising your work is where the real magic happens.

- Be open to feedback and willing to rework your pieces.

- Carry a notebook or digital recorder to jot down ideas, observations, and snippets of conversations.

- These notes can be gold mines for future writing projects.

Final Thoughts: What Is Creative Writing?

Creative writing is an invitation to explore the unknown, to give voice to the silenced, and to celebrate the human spirit in all its forms.

Check out these creative writing tools (that I highly recommend):

Read This Next:

- What Is a Prompt in Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 200 Examples)

- What Is A Personal Account In Writing? (47 Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Short Story (Ultimate Guide + Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Romance Novel [21 Tips + Examples)

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Apr 14, 2023

How to Write a Memoir: Turn Your Personal Story Into a Successful Book

Writing a memoir can be a meaningful way to reflect on your life's journey and share your unique perspective with people around you. But creating a powerful (and marketable) book from your life's memories — one that can be enjoyed by readers across the world — is no easy task.

In this article, we'll explore the essential ingredients that make up an impactful and commercially viable memoir and provide you with tips to craft your own.

Here’s how to write a memoir in 6 steps:

1. Figure out who you’re writing for

2. narrow down your memoir’s focus, 3. distill the story into a logline , 4. choose the key moments to share, 5. don’t skimp on the details and dialogue, 6. portray yourself honestly.

Before you take on the challenge of writing a memoir, make sure you have a clear goal and direction by defining the following:

- What story you’re telling (if you’re telling “the story of your life,” then you may be looking at an autobiography , not a memoir),

- What the purpose of your memoir is,

- Which audience you’re writing it for.

Some authors write a memoir as a way to pass on some wisdom, to process certain parts of their lives, or just as a legacy piece for friends and family to look back on shared memories. Others have stronger literary ambitions, hoping to get a publishing deal through a literary agent , or self-publishing it to reach a wide audience.

Whatever your motivation, we’d recommend approaching it as though you were to publish it. You’ll end up with a book that’s more polished, impactful, and accessible 一 even if it’ll only ever reach your Aunt Jasmine.

🔍 How do you know whether your book idea is marketable? Acclaimed ghostwriter Katy Weitz suggests researching memoir examples from several subcategories to determine whether there’s a readership for a story like yours.

Know your target reader

If you’re not sure where to start it doesn’t hurt to figure out your target audience 一 the age group, gender, and interests of the people you’re writing it for. A memoir targeted at business execs is a very different proposition from one written to appeal to Irish-American baseball fans.

If you want a little help in asking the right questions to define your audience, download our author market research checklist below.

FREE RESOURCE