- Countries and Their Cultures

- Culture of Samoa

Culture Name

Orientation.

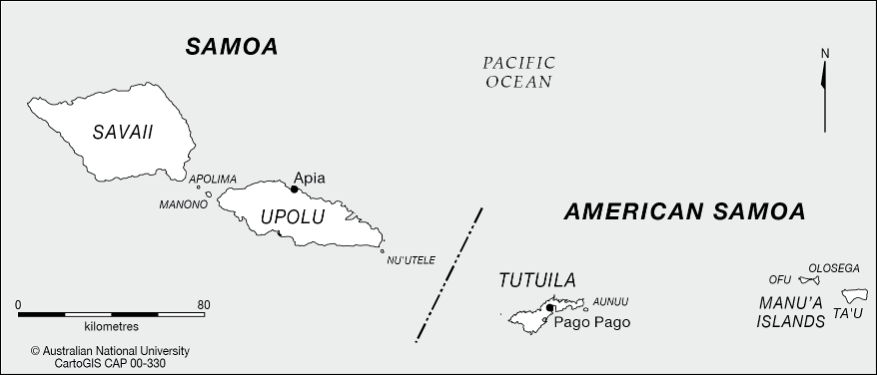

Identification. Oral tradition holds that the Samoan archipelago was created by the god Tagaloa at the beginning of history. Until 1997, the western islands were known as Western Samoa or Samoa I Sisifo to distinguish them from the nearby group known as American Samoa or Amerika Samoa. The distinction was necessitated by the partitioning of the archipelago in 1899. All Samoans adhere to a set of core social values and practices known as fa'a Samoa and speak the Samoan language. The official name today is Samoa.

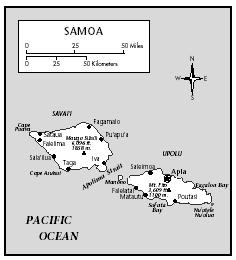

Location and Geography. Samoa includes nine inhabited islands on top of a submarine mountain range. The largest islands are Savai'i at 703 square miles (1820 square kilometers) and Upolu at 430 square miles (1114 square kilometers), on which the capital, Apia, is located. The capital and port developed around Apia Bay from an aggregation of thirteen villages.

Demography. The population is estimated at 172,000 for the year 2000, 94 percent of which is is ethnically Samoan. A small number of people of mixed descent are descendants of Samoans and European, Chinese, Melanesians, and other Polynesians who settled in the country in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

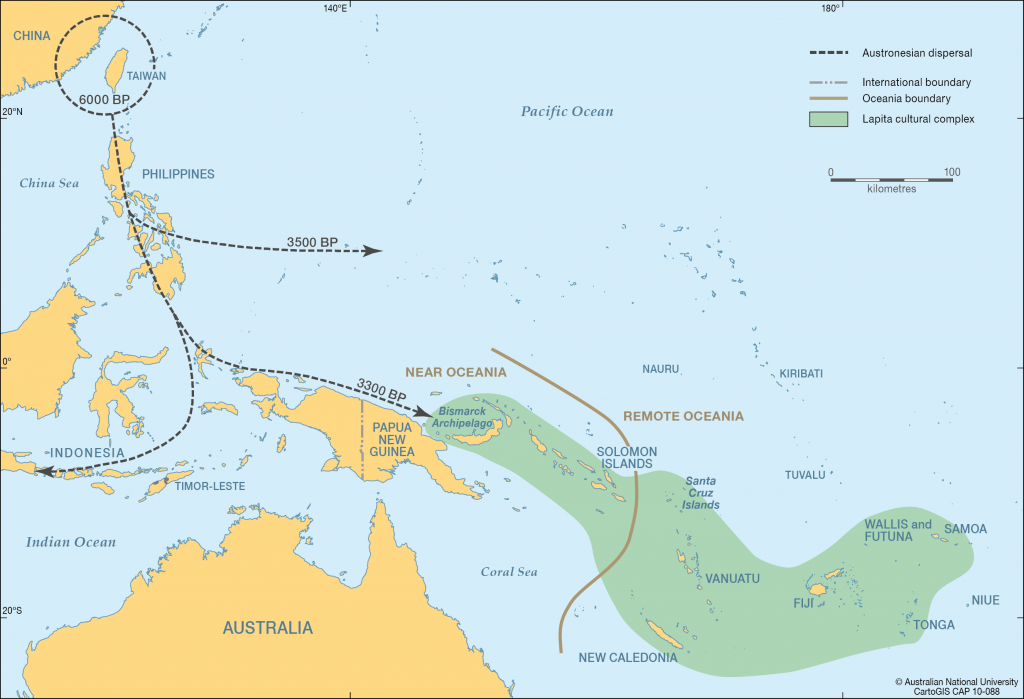

Linguistic Affiliation. Samoan belongs to a group of Austronesian languages spoken throughout Polynesia. It has a chiefly or polite variant used in elite communication and a colloquial form used in daily communication. Samoan is the language of instruction in elementary schools and is used alongside English in secondary and tertiary education, government, commerce, religion, and the broadcast media. The language is a cherished symbol of cultural identity.

Symbolism. A representation of the Southern Cross appears on both the national flag and the emblem of state. The close link between Samoan society and Christianity is symbolized in the national motto "Samoa is founded on God" ( Fa'avae ile Atua Samoa ) and in a highlighted cross on the national emblem. The sea and the coconut palm, both major food sources, also are shown on the emblem. An orator's staff and sinnet fly whisk and a multilegged wooden bowl in which the beverage kava is prepared for chiefs are symbolic of the authority of tradition. A political movement, O le Mau a Pule , promoted independence in the first half of the twentieth century, calling for Samoa for Samoans ( Samoa mo Samoa ) and engaging in confrontations with colonial powers over the right to self-government. For some, the struggles of the Mau, in particular the martyrdom of a national chief in a confrontation with New Zealand soldiers, are symbols of the nation's determination to reclaim sovereignty. Samoans celebrate the peaceful attainment of constitutional independence in 1962 on 1 June.

The national anthem and a religious anthem, Lota Nu'u ua ou Fanau ai ("My Village in Which I Was Born") are sung to celebrate national identity. Samoans refer to their country in these anthems as a gift from God and refer to themselves in formal speech as the children of Samoa, brothers and sisters, and the Samoan family.

History and Ethnic Relations

The western part of the archipelago came under German control, and the eastern part under American naval administration. The German administration was determined to impose its authority and tried to undermine the Samoan polity and replace its titular heads with the kaiser. These attempts provoked varying degrees of anger between 1900 and 1914, when a small New Zealand expeditionary force, acting on British orders, ended the German administration.

After World War I, New Zealand administered Western Samoa under a League of Nations mandate. It too was determined to establish authority and pursued a course similar to that of the Germans. It proved an inept administration, and its mishandling of the S.S. Talune's arrival, which resulted in the death of 25 percent of the population from influenza and its violent reaction to the Mau procession in 1929, left Samoans suspicious and disillusioned. These and other clumsy attempts to promote village and agricultural development strengthened Samoans' determination to reclaim their autonomy. Their calls found the ear of a sympathetic Labor government in New Zealand in the mid-1930s, but World War II intervened before progress was made.

After World War II, the United Nations made Samoa a trusteeship and gave New Zealand responsibility for preparing it for independence. A better trained and more sympathetic administration and a determined and well-educated group of Samoans led the country through a series of national consultations and constitutional conventions. That process produced a unique constitution that embodied elements of Samoan and British political traditions and led to a peaceful transition to independence on 1 January 1962.

National Identity. The national and political cultures that characterize the nation are unambiguously Samoan. This is in large part a consequence of a constitutional provision that limited both suffrage and political representation to those who held chiefly titles and are widely regarded as protectors of culture and tradition. These arrangements continued until 1991, when the constitution was amended to permit universal suffrage. While representation is still limited to chiefs, the younger titleholders now being elected generally have broader experience and more formal education than their predecessors.

Ethnic Relations. Samoan society has been remarkably free of ethnic tension, largely as a result of the dominance of a single ethnic group and a history of intermarriage that has blurred ethnic boundaries. Samoans have established significant migrant communities in a number of countries, including New Zealand, Australia, and the United States, and smaller communities in other neighbors.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

The spatial arrangement of villages beyond the capital has changed little. Most villages lie on flat land beside the sea and are connected by a coastal road. Clusters of sleeping houses, their associated cooking houses, and structures for ablutions are arranged around a central common ( malae ). Churches, pastors' homes, meeting houses and guest houses, and women's committee meeting houses also occupy prominent positions around the malae. Schools stand on land provided by villages and frequently on the malae.

The availability of migrant remittances has transformed the design and materials used in private homes and public buildings. Houses typically have large single rectangular spaces around which some furniture is spread and family portraits, certificates, and religious pictures are hung. Homes increasingly have indoor cooking and bathing facilities. The new architecture has reshaped social relations. Indigenous building materials are being replaced by sawn lumber framing and cladding, iron roofing, and concrete foundations. The coral lime cement once used in larger public buildings has been replaced by concrete and steel.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Samoans eat a mixture of local and imported foods. Local staples include fish, lobster, crab, chicken, and pork; lettuce and cabbage; root vegetables such as talo, ta'amu, and yams; tree crops such as breadfruit and coconut; and local beverages such as coffee and cocoa. Imported foods include rice, canned meat and fish, butter, jam, honey, flour, sugar, bread, tea, and carbonated beverages.

Many families drink beverages such as tea throughout the day but have a single main meal together in the evening. A range of restaurants, including a McDonald's, in the capital are frequented largely by tourists and the local elite.

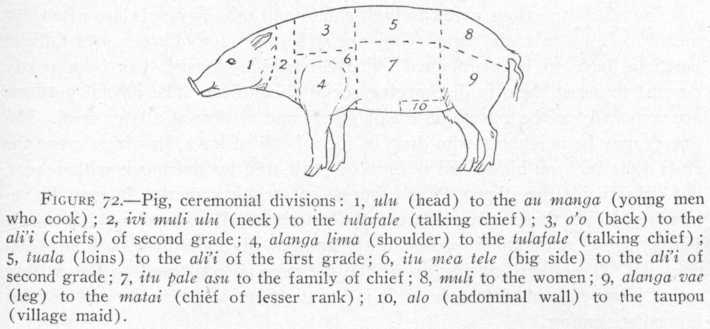

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Sharing of food is a central element of ceremonies and features in Sunday meals known as toana'i , the feasts that accompany weddings and funerals and the conferring of chiefly titles, and annual feasts such as White Sunday. Special meals are marked by a larger than usual amount of food, a greater range of delicacies, and formality. Food also features in ceremonial presentations and exchanges between families and villages. The presentation of cooked whole pigs is a central feature of such events, and twenty-liter drums of salted beef are increasingly popular. Kava ( 'ava ), a beverage made from the powdered root of Piper methysticum, made and shared in a ceremonially defined order at meetings of chiefs ( matai ) and less formally among men after work.

Basic Economy. The agricultural and industrial sectors employ 70 percent of the workforce and account for 65 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). The service sector employs 30 percent of those employed and accounts for 35 percent of the GDP. Much of this sector is associated with the tourist industry, which is limited by intense competition from other islands in the region and its dependence on economic conditions in source countries.

Land Tenure and Property. Much agricultural production comes from the 87 percent of the land held under customary tenure and associated with villages. The control of this land is vested in elected chiefs (matai), who administer it for the families ( aiga ) they head. The remaining 13 percent is land held by the crown and a small area of freehold residential land around the capital.

Trade. Samoa produces some primary commodities for export: hardwood timber, copra and coconut products, root vegetables, coffee, cocoa, and fish. Agricultural produce constitutes 90 percent of exports. The most promising export crop, taro, was effectively eliminated by leaf blight in 1993. A small industrial sector designed to provide import substitution and exports processes primary commodities such as coconut cream and oil, animal feed, soap, biscuits, cigarettes, and beer. A multinational corporation has established a wiring harness assembly plant whose production is reexported; and a clothing assembly plant is planned.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Samoan society is meritocratic. Those with recognized ability have traditionally been elected to leadership of families. Aside from four nationally significant chiefly titles, the influence of most titles is confined to the families and villages with which they are associated. Title holders gained status and influence not only from accumulating resources but also from their ability to mobilize and redistribute them. These principles work against significant permanent disparities in wealth. The power of chiefs has been reduced, and the wealth returned by expatriates has flowed into all sectors of society, undermining traditional rank-wealth correlations. The public influence of women is becoming increasingly apparent. A commercial elite that has derived its power from the accumulation and investment of private wealth has become increasingly influential in politics.

Political Life

Government. The legislative branch of the government consists of a unicameral Legislative Assembly ( O Le Fono a Faipule ) elected to five-year terms by universal suffrage. A twelve-member cabinet nominated by the prime minister is appointed by the head of state, Malietoa Tanumafili II, who has held that position since 1962. Forty-seven members are elected by Samoans in eleven electorates based on traditional political divisions. Two members at large represent general electors. Only holders of matai titles can be elected to the Fono.

Legislation is administered by a permanent public service that consists of people chosen on the basis of merit. The quality of public service has been questioned periodically since independence. Concern with the quality of governance has led the current government to engage in training programs aimed at institutional strengthening.

Social Problems and Control. The role of village politics in the maintenance of order is important because the state has no army and a relatively small police force. This limits the ability of the state to enforce laws and shapes its relations with villages, which retain significant autonomy.

Samoans accept and trust these institutions but have found that they are ineffective in areas such as the pursuit of commercial debts. Recent cases have pointed to tension between collective rights recognized, emphasized, and enforced by village polities, and the individual rights conferred by the constitution in areas such as freedom of religion and speech.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The government is responsible for health, education, and welfare in cooperation with villages and churches. Health care and education are provided for a nominal cost. Families provide for their members' welfare. The state grants a small old-age pension, and the Catholic Church runs a senior citizens' home.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

The most influential nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are the churches, in which 99 percent of Samoans participate actively and which actively comment on the government's legislative program and activity. A small number of NGOs work for the rights of women and the disabled, environmental conservation, and transparency in government. Professional associations exert some influence on the drafting of legislation. These organizations have a limited impact on the life of most residents.

Gender Roles and Statuses

The organization of traditional production was clearly gendered, and the parts of this mode of production that remain intact are still gendered. The constitution provides for equality of opportunity, and there are no entrenched legal, social, or religious obstacles to equality for women. There is some evidence of growing upward social mobility by women.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Samoan society is composed of extended families ( aiga potopoto ), each of which is associated with land and a chiefly title. All Samoans inherit membership and land use rights in the aiga of their parents' parents. They may choose to live with one or more of aiga and develop strong ties with those in which they live. Choices are determined by matters such as the availability of resources and status of various groups and personal preference. Aiga potopoto include resident members who work the land, "serve" the chief, and exercise full rights of membership and nonresident members who live outside the group but have some rights in its activities. Resident members live in clusters of households within the village, share some facilities and equipment, and work on family-land controlled by the matai.

Inheritance. Rights to reside on and use land are granted to members of a kin group who request them, subject to availability. Rights lapse at death, and matai may then reassign them. There is a growing tendency to approve the transmission of rights to parcels of land from parents to children, protecting investments in development and constituting a form of de facto freehold tenure. Since neither lands nor titles can be formally transmitted without the consent of the kin group, the only property that can be assigned is personal property.

Many residents die intestate and with little personal property. With increasing personal wealth, provision for the formal disposition of wealth may assume greater importance. This is not a foreign concept, since matai have traditionally made their wishes known before death in a form of will known as a mavaega . The Public Trust Office and legal practitioners handle the administration of estates.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. Younger people are expected to respect their elders and comply with their demands. Justification for this principle is found in Samoan tradition and Christian scripture. The only exception exists in early childhood, when infants are protected and indulged by parents, grandparents, and older siblings. After around age five, children are expected to take an active, if limited, part in the family economy. From then until marriage young people are expected to comply unquestioningly with their parents' and elders' wishes.

Great importance is attached to the family's role in socialization. A "good" child is alert and intelligent and shows deference, politeness, and obedience to elders and respect for Samoan custom ( aganu'u fa'a samoa ) and Christian principles and practices. The belief that the potential for learning these qualities is partly genetic and partly social and is defined initially within the family is grounded in both Samoan and Christian thought.

Formal education is provided in secular and religious institutions. There are elementary, intermediate, and secondary secular schools run by the government or churches and church-linked classes that provide religious instruction. There is great respect and desire for higher education, and a significant part of the education budget is committed to supporting the National University of Samoa, the nursing school, the teachers training college, the trades training institute, and overseas training.

Religious Beliefs. Samoa is overwhelmingly Christian. The major denominations—Congregationalist, Methodist, Roman Catholic, and Latter-Day Saints—have been joined recently by smaller ones such as the SDA and charismatic Pentecostal groups such as Assembly of God. Clergy and leaders are prepared at theological training institutions at home and abroad. Small Baha'i and Muslim groups have formed in recent years.

Medicine and Health Care

Parallel systems of introduced and indigenous knowledge and practice coexist. Certain conditions are believed to be "Samoan illnesses" ( ma'i samoa ) that are explained and treated by indigenous practitioners and others to be "European illnesses" ( ma'i papalagi ), which are best understood and treated by those trained in the Western biomedical tradition.

Bibliography

Ahlburg, D. A. Remittances and Their Impact. A Study of Tonga and Western Samoa , 1991.

Boyd, M. "The Record in Western Samoa to 1945." In A. Ross, ed., New Zealand's Record in the Pacific in the Twentieth Century , 1969.

Davidson, J. W. Samoa mo Samoa , 1967.

Fairbairn Pacific Consultants Ltd. The Western Samoan Economy: Paving the Way for Sustainable Growth and Stability , 1994.

Field, M. Mau: Samoa's Struggle against New Zealand Oppression , 1984.

Gilson, R. P. Samoa 1830–1900: The Politics of a Multicultural Community , 1970.

Macpherson, C., and L. Macpherson. Samoan Medical Beliefs and Practices , 1991.

Meleisea, M. Lagaga: A Short History of Western Samoa , 1987.

——. Change and Adaptations in Western Samoa , 1992.

Moyle, Richard M., ed. The Samoan Journals of John Williams 1830 and 1832 , 1984.

O'Meara, T. "Samoa: Customary Individualism." In R. G. Crocombe, ed., Land Tenure in the Pacific , 3rd ed. 1987.

——. Samoan Planters: Tradition and Economic Development in Polynesia , 1990.

Pitt, D. C. Tradition and Economic Progress in Samoa , 1970.

Shankman, P. Migration and Underdevelopment: The Case of Western Samoa , 1976.

University of the South Pacific. Pacific Constitutions Vol. I: Polynesia , 1983.

World Bank. Pacific Island Economies: Toward Higher Growth in the 1990s , 1991.

——. Pacific Island Economies: Building a Resilient Economic Base for the Twenty-First Century , 1996.

—C LUNY M ACPHERSON

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

- How to Use FamilySearch

- What's New at FamilySearch

- Temple and Family History

- Easy Activities

- Why Family History Matters

- Genealogy Records

- Research Tips

- Websites, Apps, and Tools

- RootsTech Blog

- Preserve Photos and Documents

- Record Your Story

Samoan Culture and Traditions: The Spirit of Fa’a Samoa

Fa’a Samoa , in the beautiful Samoan language, literally means “The Samoan Way.” The phrase refers to the Samoan culture and traditions that color the everyday lives of many Samoan people.

At the heart of fa’a Samoa is ‘aiga , the Samoan word for family. The definition of ‘a iga includes one’s wider family group, such as extended family and community. Reflected all throughout Samoan culture and tradition is the importance of maintaining close family and community ties.

As you read through our list of Samoan traditions, see if you can spot the spirit of fa’a Samoa— the spirit of family.

1. Fa’amatai

Much of Samoan culture is reflected in a collectivist system of governance called fa’amatai . In this system, both family and village leaders are expected to show qualities of selflessness, putting the best interests of the community and family members above their own interests. In turn, these village leaders, who are known as matais, are highly respected by those they serve.

Although this traditional structure has begun to change over time, the principles of service and community remain. Samoan people are known for their warm smiles and friendly personalities. They have a gift for welcoming and accepting just about anyone they meet. So it’s no surprise that qualities such as hospitality, cooperation, respect, and consensus are highly valued in Samoan culture.

2. Samoan Cuisine

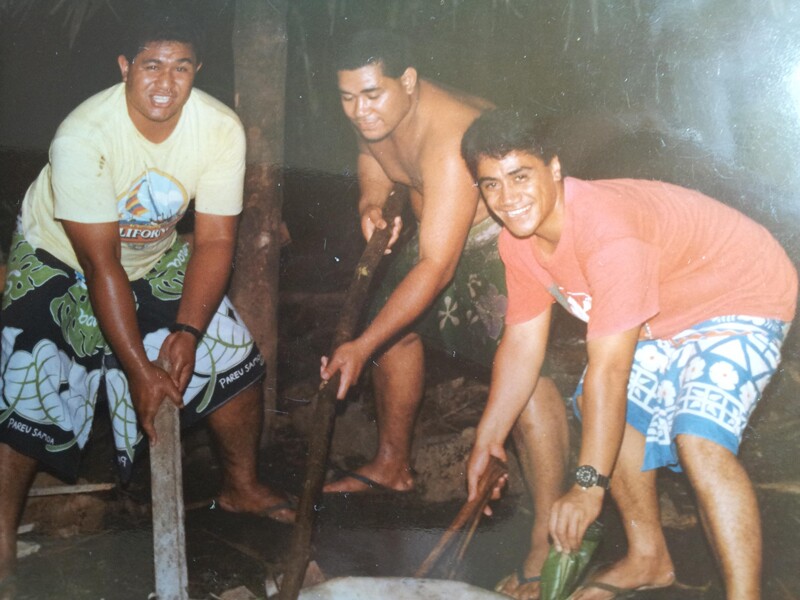

Many cultural events and even daily life are centered around food and feasts. Local cuisine includes a lot of coconut milk and cream. On Sunday mornings, many families cook on a Samoan umu, an above-ground stone oven. Staples such as breadfruit, taro, coconuts, bananas, fish, chicken, and pork all play a leading role in Samoan meals, the everyday and celebratory meals alike.

3. Samoan Tattooing

Samoan culture is rich with traditions. One well known tradition is the tatau, or Samoan tattooing. In Western culture, tattoos are often considered a form of adornment or self-expression, rather like clothing styles. In Samoa, the tatau has a deeper, historical significance.

Samoan tattoos are unique symbols representing an individual’s faith and family ties. They also communicate status or respect within a community. The process of getting a tatau is long and painful, making the act of getting one a deeper reflection of an individual’s devotion to the community.

4. Weddings

Weddings are another beautiful Samoan tradition. In true, friendly, selfless fashion, Samoan couples do not expect gifts from their guests. Instead, they are the ones that give out the gifts, based on the social status of their guests. In Samoan culture, this gift giving helps the couple instantly begin to establish themselves as a new family in their community.

5. Entertainment

Entertainment in Samoa includes a lot of singing, dancing, food, and enjoying the beautiful landscape. Depending on the weather, you are likely to see a lot of deep-sea diving, surfing, fishing, volleyball, and rugby happening on the islands. Below are a few additional uniquely Samoan forms of entertainment.

Kilikiti—Samoa’s Version of Cricket

The national sport of Samoa is kilikiti, a uniquely Samoan version of cricket that was created after English missionaries introduced cricket to the islands in the 19th century. The sport’s bat, called “pate,” is often made from the hibiscus or breadfruit tree , and the rubber ball is made from tightly-wrapped latex fiber of the pulu vao tree or rubber tree.

Coconut Husking

Another traditional form of entertainment is coconut husking. In this tradition, Samoans break open coconuts with large stick—they may even use their teeth for husking. Communities often hold coconut husking competitions .

Siva Afi—Fire Knife Dancing

Siva Afi refers to fire knife dancing, a traditional dance that includes the twirling of a flaming knife while performing impressive acrobatic stunts . Anciently, the dance was performed by Samoan warriors as a way to demonstrate strength and battle prowess.

Samoan heritage is beautiful and full of rich, human connection. Its influence has spread to benefit communities well outside of the islands. Do you and your family come from Samoa or American Samoa? Share what fa’a Samoa means to you in your Memories. Discover the stories of your Samoan ancestors at FamilySearch.org , and continue the legacy.

Search for your American Samoan Ancestors

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Historyplex

An Introduction to the Enchantingly Rich Samoan Culture

The culture in the islands of Samoa makes for a fascinating read. Read on to find out more about a system based on mutual respect, strong societal values, and fraternity - the Samoan culture.

The culture in the islands of Samoa makes for a fascinating read. Read on to find out more about a system based on mutual respect, strong societal values, and fraternity – the Samoan culture.

The Samoan Islands in the South Pacific are politically divided into two groups: the western and eastern islands. The western half of these islands forms the independent country called Samoa , while the eastern part is an unincorporated territory of the United States, known as American Samoa.

This article deals with the culture of both these regions collectively, since it is geography, rather than politics, that defines the way of life for the people of this Polynesian archipelago. American Samoa is being increasingly influenced by Western civilization (although in the case of Samoa, the US actually lies to the East), but the native culture remains venerated, and is largely followed to the letter. Hence, the word ‘Samoa’ in this article refers to the geographical region of the Samoan islands, unless otherwise stated.

Samoans, along with other Polynesian islanders, were famed in the middle ages for their exceptional navigational ability. This, combined with the remote location of these islands, made Europeans quite curious about the culture of these islands.

Let’s take a look at the culture of this mystical and isolated region.

Fa’a Samoa (The Way of Samoa)

The culture and traditions of Samoa are based on Fa’a Samoa , which literally translates to The Way of Samoa . The three crucial parts of the cultural traditions are family, faith and music . Let’s understand the nuances of these aspects of the Samoan life.

Fa’amatai (or fa’a matai)

If you break the word into two parts, matai means the head of the family, and the prefix fa’a stands , as we saw before, for ‘the way of’. Hence, this aspect deals with the customs, rules, and traditions of Samoan families.

The matai is a revered position in the Samoan culture. Matais perform the ritual duties of a Samoan family, and in the modern administrative system, are the only ones allowed to run for parliamentary office. Earlier, matais were also the only ones allowed to vote, although this right has since been diluted to grant suffrage to the masses. Matais of individual families (large, joint families called aiga ) in a village make up the town council, or the fono . The larger the aiga , the more respect its matai commands.

There are two types of matai : ali’i (high chief) and tulafale (orator chief). The ali’i’s wife is called faletua whereas the tulafale’s wife is called tausi. The orator chiefs speak on behalf of the high chiefs at public events and ceremonies. They are also responsible for record keeping of data pertaining to genealogies (gafa) and pedigree (fa’alupega). Men and women have equal rights to become a matai.

In Samoa, about 80% of the population lives on family land, on which the government has no say, right, or claim. Looking after this land is a crucial duty of a matai, encapsulated in the local proverb,

E le soifua umi le tagata fa’atau fanua — The man who sells family land will not live to an old age, for devils will bring about his early death.

Everyone is entitled to become a matai through his/her ancestry. However, the title isn’t passed in a hereditary fashion. Titles aren’t inherited, but awarded by the extended family, who decide which candidate would serve them best. The title is bestowed upon a person in a ceremony called saofa’i . The titles are added before the Christian name.

In modern times, the traditional honor of the matai is being devalued by instances of conferring the title to gain political leverage, or personal gains. However, the occurrence of such events is still comparatively rare.

ʻAva Ceremony

Basically conducted to mark important events and ceremonies, the ‘ ava ceremony is a unique and vital ritual in the Samoan culture. Important events, such as the conferring of matai titles, are not considered complete if ‘ava has not been served.

The basic rituals remain the same, with certain alterations depending on the occasion and the parties involved. One of the main rituals in this ceremony is preparing the ‘ava drink. The right to prepare the drink is a coveted honor among Samoan families. The beverage is made from the roots of Piper methysticum , the kava plant. A process has been designed by the community for preparing and serving this drink. The person who serves the beverage is called tautu’ava , and the one who makes it, the aumaga . It is prepared in a bowl called tanoa which is hosted on a number of sticks for support and served in a smaller cup made from the shell of a coconut, called ipu tau ‘ava . Even the seating position for these ceremonies is decided by tradition, with the chief and the orators receiving prominence.

Samoan houses are called fale . Mirroring the communal emphasis on values such as respect and fraternity, these fale have no walls, and are built as domes or cones, supported by pillars. The site on which they are built is called tulaga fale . Fale are lashed together by a plaited rope called ‘ afa , which is made from coconut fiber. Preparing the ‘afa is a complex procedure that involves performing numerous processes on the versatile fiber, such as soaking, beating, and braiding. All these procedures are collectively known as ‘lashing of the ‘afa’, which can take months to complete. The entrance to the house faces the main road in the village. The area immediately outside this entrance is called malae and is used for important ceremonies and gatherings.

Although fale don’t have doors, privacy is achieved through blinds made from natural fibers or large leaves. A similar process is used to divide the house into various sections.

Traditionally, no metal was used in the construction of these houses; it was only after the arrival of Europeans that Samoans started using metal in their construction, and traditional methods are still popular.

There are many types of fale, such as the faleo’o (beach fale) fale tele (big house), and afolau (long house).

Fale is also used to describe other buildings ‘housing’ some facility. For example, hospitals are called fale ma’i which means ‘house of the ill’.

The word tufuga denotes the mastery of an individual over a particular vocation. For example, fau fale means house builder. However, if you add tufuga before the term, the resultant tufuga fau fale means ‘master house builder’. Tufuga is similarly used in other instances, such as tufuga ta tatau (master tattoo artist), or tufuga fau va’a (master navigator). The assistants of a tufuga are called autufuga . To avail the services of a tufuga, people have to follow appropriate customs, and can’t just hire them like any other workman.

The traditional attire in Samoa consists of puletasi , a skirt and tunic worn by women. The skirt and the tunic are usually of matching colors and patterns. Additionally, they’re adorned with traditional Samoan designs. Both men and women wear the lava-lava , a type of sarong. The puletasi and lava-lava are usually worn to traditional events and other formal occasions. Today, there are a lot of variations to these dresses, and in cities, Samoans usually wear contemporary clothing.

Most — 99% — of the population in Samoa is Christian . The Baha’i Faith is the largest minority. There are only seven Baha’i Houses of Worship in the world, one of which is in Samoa. Hinduism and Buddhism are followed by extremely small communities.. In Samoan society, it is very important to participate in and donate to religious functions and events. The constitution provides every citizen with freedom of religion, which is usually upheld with great respect; reports of religious disturbances are very rare .

Although Samoans are officially Christian, they — especially the ones from the independent Samoa — have integrated various native customs into the prevalent norms of Christianity, so that the Christianity observed on these islands is a highly homogenized mixture of local traditions and traditional Christianity.

Fa’aaloaloga

Fa’aaloaloga means the formal presentation of gifts in Samoan culture. It is performed at almost every function, from weddings to funerals. It is a very prominent part of the culture and every Samoan must abide by it. Gifts are always given first to religious representatives, then people with highest ranks and then to the chiefs. The gifts can include things like money and mats and are usually presented on a tray with some drink and biscuits. Depending on the rank of the person, these gifts are amplified — in size or type.

Like all coastal regions, Samoan cuisine depends heavily on seafood and coconuts . A special part of Samoan dining is the communal Sunday umu . Umus are ovens made of hot rocks, and are used to cook various foods, such as whole pigs, seafood such as crayfish and seaweed, coconut products, taro leaves, and rice. Sundays are traditionally ‘rest days’, and many families gather to prepare and enjoy the umu feast. The elders eat first, and then invite the others to join in.

Music and Dance

Music in Samoa is not so much a pastime as a cultural obligation, an inseparable aspect of Fa’a Samoa . Music is used by Samoans for expressing every emotion; Music is used to both celebrate and commiserate, as well as to admire and reflect upon the usual, day-to-day life.

The prominent instruments include conch shells, pan flutes, nose-blown flutes, and numerous idiophonic instruments, i.e., instruments played by striking two components together; while the vocal component is usually manifested in the form of ever-enthusiastic — if not always musically refined — chorus.

Samoan music hasn’t gathered universal acclaim, but some ensembles, such as the bands Past to Present and The Katinas have gained considerable following in Oceania and the United States, besides fame in their homeland. Modern bands have incorporated contemporary instruments, such as the guitar and the keyboard, into their music in a moderately successful bid to appeal to wider audience.

Samoan dance, like their music, stems from the desire to reflect every emotion through art. A popular genre of dance is Siva , which is usually performed by men. A unique and spectacular part of Samoan dance is the Siva afi , or the fire knife dance . Traditionally, machetes wrapped in towels at both ends were used in this thrilling spectacle, with the towels set on fire. In modern renditions, the steel blade is usually substituted by wooden staffs, or are blunted or shortened considerably. These modern practices, especially popular in the more westernized American Samoa, do not sit well with the Samoan traditionalists.

The culture of these Polynesian islands places great emphasis on respect for the established social hierarchy, communal events, and its unique brand of music. The Samoans respect these customs immensely, and this isolated Polynesian society has been held together by these very strands of societal norms for centuries.

Like it? Share it!

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Further insights.

Privacy Overview

Legacies of Colonialism in Samoa

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E5), students will examine the legacies of the colonial era and how Samoans have striven to overcome them. Students will explore how ideologies shape language and the West’s view on Samoa and its people.

- Explore the legacies of colonialism in Samoa.

- Recognize how derogatory language toward Samoans misshaped the global view of Samoa and the Samoan people.

To Decolonize, We Must End the World as We Know It

How Can Societies Decolonize Conservation?

Nameless Woman

Imphal as a Pond

The Trauma Mantras

Spotlighting War’s Cultural Destruction in Ukraine

The Responsibility of Witnesses to Genocide

A Call for Anthropological Poems of Resistance, Refusal, and Wayfinding

Cultivating Modern Farms Using Ancient Lessons

How Israeli Prisons Terrorize Palestinians—Inside and Outside Their Walls

The Viral Atrocities Posted by Israeli Soldiers

What It’s Like to Grow Old on the Margins

Dismantling the “Man the Hunter” Myth

Taking on Parkinson’s Disease—With Boxing Gloves and Punching Bags

A Long Road Ahead

The Psychedelics Industry Is Booming—but Who’s Being Left Out?

“T”

Who Pays the Price When Cochlear Implants Go Obsolete?

What Is Linguistic Anthropology?

The lack of isolation of individual countries and the practice of creating a world with more fluent borders.

A set of words that is spoken and understood by a group of people.

Something that was passed on by the people who have lived before us.

- Several countries played a role in the colonization of Samoa: Germany, New Zealand, and the United States. Lead students in considering how each country influenced Samoan culture.

- The legacies of colonial rule in Samoa are complex, as some are viewed negatively while others are seen in a positive light. Explore with students how Western traditions, views, and beliefs infused Samoan culture.

- Investigate how, despite colonization, Samoans have generally been able to preserve their traditions and cultures.

- Language can carry bias and affect a person’s empathy. Colonizing nations often used derogatory language to refer to the people they colonized, inhibiting the ability to understand them. Discuss how words like “savage” and “heathen” resulted in negative and false interpretations of non-Western cultures.

- Language is a powerful tool. It can uplift, and it can harm. Examine the impact language and its usage has had on the global view of Samoans.

Cervone, Carmen, Martha Augoustinos, and Anne Maass. 2021. “The Language of Derogation and Hate: Functions, Consequences, and Reappropriation.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 40 (1): 80–101.

McMullin, Dan Taulapapa. 2011. “Fa’afafine Notes: On Tagaloa, Jesus, and Nafanua.” Amerasia Journal 37 (3): 114–131.

Sailiata, Kirisitina Gail. 2014. The Samoan Cause: Colonialism, Culture, and the Rule of Law. Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan.

Tuia, Tagataese Tuia. 2019. “Globalization, Culture and Education in Samoa.” International Online Journal of Primary Education 8 (1): 51–63.

- Discuss the colonial legacies that are still found in Samoa.

- What, if any, influence did colonialism have on the educational system in Samoa?

- How does language shape our view of other people and ourselves? Include examples to support your points.

- Discuss how derogatory language can be used to devalue other people and how this can impact our society.

- Watch “How Language Shapes the Way We Think” in Additional Resources. Create a list of your thoughts while you are watching this video. How would derogatory language play a role in the topic of this video?

- Can language be used to intentionally manipulate other people’s perceptions of the world? Write an essay arguing your opinion.

- Create an infographic highlighting a selected colonial nation in Samoa.

- Create a list of at least two cultural aspects that were influenced by Germany and New Zealand and that can still be found in Samoa.

Slides: “ Post-Colonial Legacies”

Podcast: Dayonara Gaoteote’s “ Keeping SĀMOA in American Samoa ” in American Samoa Politics: Performing SĀMOA

Video: Lera Boroditsky’s TEDx Talk “ How Language Shapes the Way We Think”

Video: UN Story’s “ The Shocking Link Between Hate Speech and Genocide”

Nadine Rodriguez, Freedom Learning Group

Unpacking the Mead–Freeman Controversy

Y ou may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

I n short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on SAPIENS.

A ccompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

We’re glad you enjoyed the article! Want to republish it?

This article is currently copyrighted to SAPIENS and the author. But, we love to spread anthropology around the internet and beyond. Please send your republication request via email to editor•sapiens.org.

Accompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Cultural values and education in Western Samoa: Tensions between colonial roots and influences and contemporary indigenous needs

Related Papers

Oceanic Culture History: Essays in Honour of Roger Green

Jeffrey T Clark

Bradd Shore

Over the course of three decades my understanding of Samoa has been profoundly affected by Robert Levy's seminal work on Tahiti. No influence on my thinking has been more compelling. In this article I pay tribute to Levy by tracing the influence of his ideas on my understanding of Samoan ethno-psychology.

George Appell

Ruben Iosefa

The lack of studies done on Pacific Islander students is evident in the literature, but more so regarding Samoan students. The majority of literature on the Samoan people focuses on identity, family, culture and rarely on the Samoan student. Even more so on the Samoan college student. It is imperative to understand such a fast growing minority population in the United States and the relationship between education and assimilation that can either prove beneficial or detrimental to the student’s experiences. It is also imperative to seek how assimilation within this population has challenged the old model of what assimilation is; that is, one cannot partially assimilate, but must rather fully assimilate in order to be successful. The question I sought to answer was: How does the Samoan culture either positively or negatively affect the Samoan student’s college experience? I took a quantitative approach by distributing surveys to 50 Samoan college graduates or current students from a 2-year or 4-year college in the United States. All participants were 18 years of age or older. The literature argues that academic success has been equated to assimilation into American society; but is this always the case? The majority of respondents participated in Samoan culture and cited church, family and education as the main sources of culture. The majority of respondents also performed well in school, which suggests that one does not have to assimilate in order to be successful, as the literature stated. My results were consistent with my hypothesis that family and church played a huge role in the Samoan college student’s experience. This study is slightly skewered towards those who are or were successful in college. Further research should be done on reasons why Samoans did not finish school; or why they take personal responsibility for their failures, instead of blaming them on the Samoan culture. This study seeks to help educate and inform the Samoan community regarding education and the advantages and/or disadvantages of assimilating.

Seth Quintus , Ethan Cochrane

Noah Borrero

The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus

Max Quanchi

Dr Donella J Cobb , Associate Professor Fuaialii Dr Tagataese Tupu Tuia Tuia

Since Samoan fa'afaletui (meeting) was first conceptualized as a research methodology, fa'afaletui has experienced an uncomfortable coupling with Western research approaches and methods. This article takes an epistemological turn by looking closely at the Indigenous principles and cultural practices that underpin fa'afaletui as a traditional conversational practice to bring fresh insight into fa'afaletui as a research methodology and method.

Eric George

This essay will look at the dichotomy between traditional Samoan religion and Christianity within that context – a comparison of certain ideological implications between the two.

Sadat Muaiava

Contact between the indigenous peoples of the Pacific and the western world has had immense sociocultural and linguistic impacts on indigenous communities. Perhaps the major source of sociocultural and linguistic impact in the Pacific can be attributed to the arrival of Christianity. This is certainly the case for Samoa. The fusion between fa'asamoa (Samoan culture) and the lotu (church) is evidence of Christianity's profound impact. The fusion is also evidence of the Samoan people's unequivocal stance for cultural safeguarding. As missionaries sought to eradicate much of the Samoan beliefs system, the Samoan leaders at the time were content to construct the new doctrine around the fa'asamoa. The highest class in the church is the faife'au (church pastor). A decade after continued missionary work in Samoa, the faife'au and his family were introduced by the missionaries, once they had deemed that the Samoan church was fit for self-governance. Today, both in Samoa and overseas, the church is structured around the Samoan indigenous political order. To some degree, the faife'au was also bestowed the highest of honorific status in Samoa. Yet the Samoan parsonage family is unique in the Samoan class structure. The aim of this article is to discuss this uniqueness by examining the feagaiga (covenant) and tagata'ese (stranger) experiences of the Samoan parsonage family. Both the feagaiga and tagata'ese concepts are fused entities that have been constructed by both the fa'asamoa and lotu. The Samoan parsonage family has been neglected in both the Pacific mainstream and theological literatures until now.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Culture Contact in the Pacific: Essays on Contact, Encounter and Response, ed. Max Quanchi and Ron Adams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993)

Bronwen Douglas

Mike Carson

Helene Martinsson-Wallin

Journal of Linguistic Anthropology Vol 6 no. 2: 255-7

William O Beeman

Yu-chien Huang

American Anthropologist

Andrew Peter

J. Polynesian Soc

deborah gough

David J Addison

Anne Freese

Ilana Gershon

Georges Benguigui

Joakim Wehlin

Sean P. Connaughton

Talanoa Radio: Exploring the Interface of Development, Culture and Community Radio in the South Pacific

Linda S . Austin

Dan Taulapapa McMullin

Springer eBooks

Alessandro Duranti

International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies

Sadiya Abubakar

Ralph Linton

Archaeology in Oceania

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Case: Food in Sāmoa

Garrett Hillyer

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Identify common contemporary dietary crises in Samoa and draw connections to food history in the region.

- Articulate the central role of food in Samoan culture (and other Indigenous Oceanian cultures, more broadly).

- Describe the complications of looking to food pasts to solve food problems in the present.

Introduction

Like many island nations and territories in Oceania, the two polities of Sāmoa (the Independent State of Sāmoa and the U.S. territory of American Samoa) are undergoing a serious health crisis. Problematic conditions linked to dietary habits are resulting in increased hospitalizations, surgeries, and even deaths. These conditions include type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, among others.

During my time conducting food research throughout the archipelago, which included years of participant observation , I noticed that imported processed foods were heavily featured in contemporary daily diets. While living with a host family on the island of Manono in the Independent State of Sāmoa, not a day went by that we didn’t eat hot dogs, instant ramen, white bread, or canned corned beef, which were generally accompanied by soda or other sugary drinks and juices. We also frequently ate ancestral foods, or foods produced, procured, and eaten long before outsider arrival in Sāmoa. These included foods like baked taro, breadfruit, and yams, or starchy varieties of bananas stewed in coconut cream, along with locally caught fish or locally raised chickens and pigs, and sometimes served with a glass of vai tīpolo , which is a juice derived from a local citrus fruit.

In either case, when we ate, we ate a lot . My host family was culturally obligated to take care of me, as a guest in their home, and this primarily centered on providing me with ample amounts of food. I once remarked to a friend in my village that I could barely finish my daily meals, to which he replied, “Good. That means your family is taking care of you.” As a Samoan, he knew that my host family would be highly regarded by their neighbors for their ability to host and to provide. Even without guests in the home, though, Samoan families still tend to eat large meals for similar reasons, because providing for one’s children or parents is also a sign of familial respect, care, and love. This provision primarily comes in the form of food. Ensuring that one’s family has plenty to eat is an assurance that one is of service and utility to their family, and therefore in keeping with the Faʻasāmoa —the Samoan way of life.

Though my research was more concerned with charting changes over time in Samoan foodways than with contemporary dietary disease, the issue of health and wellness constantly came up when discussing my work with others. Whether talking with Samoan scholars at different universities and archival centers, or with my host family or my friends in the village, I tended to hear the same sentiment shared over and over again: If only Samoans ate the foods they used to eat , then dietary disease would go away entirely. However, the uncomfortable truth that some acknowledged and many avoided remained: Newer, imported foods are just too tasty, too ingrained into Samoan diets, and too deeply embedded into Samoan culture itself to cut out entirely.

This chapter presents a historical overview of Samoan food and food culture, introducing readers to the roots of Sāmoa’s contemporary health crisis. In so doing, it offers a window into a problem that is not unique to Sāmoa alone. However, while dietary disease is on the rise around the world, the unique place of food in many Indigenous Oceanian cultures as a means of conveying notions of respect, love, and wealth means that many Indigenous Oceanian peoples are eating more and more imported processed foods. In what follows, therefore, I also show how these new and imported foods are entangled with deeper notions of Samoan taste, making it all the more difficult to eliminate them from Samoan diets. Finally, I ask readers to consider whether a “back to the future” approach—that is, an approach in which Samoans return to eating ancestral foods completely—is really feasible.

Food in Sāmoa’s Deep Past

When the Lapita peoples arrived in the Samoan archipelago around 3,500 years ago, they came prepared. Having long since mastered the domestication of animals like dogs, chickens, and pigs, the cultivation of crops like coconut, taro, and breadfruit, and the development of cooking techniques like the earth oven, Lapita peoples successfully colonized the Samoan archipelago as well as other island groups in Oceania.

As a distinct Samoan language and culture developed out of the first Lapita peoples, it eventually became predicated upon a matai , or chief, system. Daily life was paced by the will of matai who were obligated to look after the villages over which they held political influence. This meant, among other things, regulating the production and procurement of food. Matai delegated land for cultivation, organized and regulated the procurement of fish and shellfish, and deemed when it was appropriate to kill and prepare more specialized foods, such as chickens and pigs. In turn, non- matai village members were obligated to pay food tributes to their matai during important ceremonies and rituals, providing matai with prized food items like the heads of fish or loins of a pig.

As Sāmoa’s population grew, Samoan society and the matai system became even more stratified, and several different rankings developed. Some of these highly stratified rankings could be seen in food production, procurement, preparation, and service. For example, young men without matai titles were expected to carry out most of the day-to-day production and procurement of food, such as minding plantations and catching fish. They were also the primary cooks, as Samoan cooking with an ʻumu , or earth oven, is considered a laborious and dangerous job. Though some women held matai titles—and very high-ranking titles, at that—the vast majority of matai were men. As a result, women were primarily expected to raise families and maintain the cleanliness of villages and homes, although they also had specific food duties, such as procuring shellfish from shallow coastal waters. Age roles developed, too. Generally speaking, younger men and women were responsible for more laborious tasks while older people, titled or not, were taken care of by their children and grandchildren.

At regular intervals, peoples of all ranks came together for ceremonies and celebrations to mark significant moments in time, such as weddings, funerals, birthdays, and victories in war, and large feasting always accompanied these events. The strength and dignity of a village was often derived from their ability to host traveling parties from other villages. Likewise, the strength and dignity of villages represented by traveling parties, or guests, was often derived from their ability to present food gifts and tributes to their hosts in return. In this sense, food was integral in establishing relationships between peoples and groups.

As Samoan food culture developed, so too did Samoan tastes. Many oral traditions speak of lolo , or rich, fatty foods as being most prized. This is perhaps due to the fact that so much of Samoan food consisted of coconut cream, which is a rich, fatty substance that was often cooked with and/or served with baked taro, breadfruit, fish, and other staple foods. In fact, some of the elders I spoke with during my research told me that this is why the heads of fish or the loins of a pig are gifted to the highest-ranking matai —because these pieces contain the most lolo flavor.

This early period of Samoan food history was marked by intense labor. It is not easy to climb a coconut tree or to pull taro up from the root, not to mention moving the rocks necessary to form an ʻumu . Even a seemingly ‘easy’ task like picking shellfish off coastal rocks and coral still takes a significant amount of energy. This work—the work of food—regulated Samoan society for generations, but it also meant that peoples burned a significant number of calories to maintain steady diets.

Food in Sāmoa’s Recent Past

Europeans first sighted Sāmoa in the mid-18th century, but contact between Europeans and Samoans was very limited until 1830, when missionaries from England began working to convert Samoans to Christianity. Around this same time, a global whaling industry boomed, which brought several pālagi , or non-Samoans, to Samoan shores, to refuel their ships, trade their cargo, or to settle permanently and profit from Sāmoa’s burgeoning economy. As the Samoan economy boomed, European and American colonial interests peaked as colonial agents sought to profit from industries like whaling and copra . By 1900, the Samoan archipelago was split into two halves, and without much voice given to Samoans themselves.

Though this history of colonialism goes much deeper, it is important to note here that these early pālagi brought with them something that would change Samoan food forever—canned goods. These included canned vegetables, fish (especially salmon), and beef, including the highly prized pīsupo , or corned beef, so named because in its early canned form it resembled cans of pea soup. Given their scarcity, and especially their lolo flavor, canned fish and meats became especially highly prized items in Samoan society. Where once a high-ranking matai might have expected a certain cut of pig or piece of fish as a food tribute from their village or a traveling party, they eventually grew to expect imported pālagi foods. Still, throughout the nineteenth century, limited supply of canned goods, a small overall population, and the fact that most Samoans remained largely within ancestral subsistence economies, all prevented an exponential growth of Sāmoa’s pālagi food presence.

By the mid-20th century, however, a combination of factors changed this. Catastrophic natural disasters brought in food aid from countries like New Zealand, Australia, and the United States, including flour, yeast, rice, and sugar in great supply. This influx gave way to new foods like pani popo (literally “coconut bread”), or buns baked in coconut cream, and koko alaisa (literally “cocoa rice”), or rice cooked in hot cocoa. In addition, the world wars in the early-to-mid-20th century meant more people, industry, and cash in Sāmoa’s economy, giving more Samoans exposure and access to pālagi foods. As with many island groups in Oceania, food items like SPAM became a bigger part of daily diets, and with more Samoans able to afford more pālagi foods, Samoan tables began looking more and more pālagi by the minute, while also retaining many ancestral foods like taro, coconut, and breadfruit. While restaurants, bars, bakeries, dairies, and grocery stores had existed in Sāmoa since the mid-nineteenth century, they rapidly expanded through the mid- and late-20th century. Before long, both Samoan polities had several eateries and groceries selling ultra-processed foods . For example, the Independent State of Sāmoa boasts its own McDonald’s fast food restaurant, while the less populated American Sāmoa claims two , along with other fast food establishments like Carl’s Jr. and Pizza Hut.

Food in Sāmoa’s Present and Future

While foods changed, Samoan cultural values surrounding food persisted. This is not to say that Samoan culture remained static, as it continued to change during the 20th century, just as it had prior to European arrival in the islands. Rather, the ties between food, gifting, ceremony, respect, and provision remained a central tenant of the Faʻasāmoa . As such, Samoans continued to place incredible value on providing prized lolo foods to family, friends, matai , and any other peoples with whom they wished to sustain positive relationships. At the same time, within families, providing one another with plenty to eat remained a crucial way to communicate love, respect, and care. Consider, too, that with ease of access comes a lack of activity. Where foods were once difficult to cultivate, catch, and cook, they are now readily available on grocery shelves, and with the transition of many from subsistence to sedentary lifestyles and work, less activity means fewer calories burned. Some food scholars have labeled this kind of change in food choices and activity levels as the “ nutrition transition .”

We also need to consider the interplay of food and colonialism. While this subject is too complex to go into here, it should be noted that power dynamics between smaller island nations like Sāmoa and larger nations like New Zealand, Australia, and the United States often involve some degree of hegemony . In regard to food, this can mean the exportation of unhealthy foods into Sāmoa without correlating funding for the medical problems that inevitably arise from eating such foods. For example, the Independent State of Sāmoa tried to implement various bans on imports, including a recent ban on turkey tails, but they received pushback from wealthier nations who threatened to restrict their induction into the World Trade Organization, not to mention significant local uproar from Samoan people who love turkey tails’ lolo flavor. With limited political recourse or external public health support, and widespread local demand for imported foods, both Samoan polities find themselves struggling to combat dietary disease. Craig Santos Perez, a CHamoru scholar and poet, calls this kind of power dynamic “ gastrocolonialism ,” which he broadly defines as “structural force-feeding.” According to Perez, gastrocolonialism not only erodes food cultural knowledge and increases dependency on imported foods, but it also leads to chronic diseases linked to poor diet. This is certainly true of Sāmoa.

In a recent documentary (which forms the foundation for an assignment at the end of this chapter), a Samoan doctor called type 2 diabetes a “tsunami in the Pacific.” Indeed, several recent studies show that both Samoan polities and several other Oceanian territories and nations have some of the highest per capita cases of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other diet-related conditions in the world. Later in the documentary, the same doctor states that when he was young, he ate mostly ancestral foods, whereas Samoan children today eat imported processed foods in bulk. Like many Samoans, the doctor’s opinion is that a return to ancestral foods will mitigate dietary diseases in the region. However, is the answer that simple? Is removing imported foods from Samoan society and culture feasible?

Considering that imported processed foods have been an integral part of Samoan food culture for over a century, and that gifting and eating in bulk is intertwined with Samoan cultural norms, it becomes much harder to grapple with the possibility of ridding Samoan culture of imported foods. In fact, many Samoans dedicated to making these changes are adopting and adapting non-Samoan means of improving public health. For example, Zumba classes and CrossFit groups have become increasingly popular ways to stay active, and fruits and leafy green vegetables are being pushed by government and grassroots campaigns to try to convince Samoans to eat more healthfully. In this sense, the notion of returning to Sāmoa’s food past is complicated by the fact that innovative, contemporary public health practices are simultaneously promoted as the answer to the problems of Sāmoa’s food present. On the other hand, some farmers are attempting to grow a kind of slow food movement in Sāmoa, predicated on revitalizing ancestral agricultural practices and diets. This suggests that perhaps looking to the past can provide a path to a healthy and sustainable food future. On the other other hand, what does a “back to the future” approach mean for Samoans who feel that eating imported foods is the mark of a thriving people? And who are activists—especially outsider activists—to tell Samoans that they cannot eat the same foods that have given so much meaning to cultural exchanges for so long?

This short text does not propose clear answers to the complicated questions it poses. Perhaps, however, readers will now be interested to further engage with food studies in Sāmoa, and Oceania more broadly, to address things like food adoption and adaptation, the relationship between food and health, the entanglement of food and colonialism, and the complications of eradicating imported foods from Indigenous Oceanian societies and cultures. The assignments following this chapter provide an opportunity to begin that engagement, and welcome all readers to begin discussing these serious issues with one another.

Discussion Questions

- Given what you learned in this chapter about Samoan food culture, what is the role of food in the cultures with which you are familiar? In what ways is Samoan food culture distinct from and/or similar to these food cultures?

- What are some of the ways that dietary disease can be linked to food culture? How can food culture help prevent dietary disease?

- What is the link between colonialism and dietary disease?

- In its concluding section, this chapter asks if the answer to Sāmoa’s (and Oceania’s) dietary disease crisis is taking a “back to the future” approach? What might be learned from looking at diets from the past? What might be learned from contemporary public health practices?

Exploring Food in Print

While it is not always possible to travel to Oceanic islands to speak directly with people to learn about the past and present of their food culture, much can be learned from materials housed in archives. Go to the National University of Australia’s TROVE digital archives and browse through issues of The Pacific Islands Monthly . While it is important to remember that this magazine was written for a Euro-American audience, it contains advertisements and stories about food across Oceania. Click on the “Browse this collection” button, and then click on any of the thumbnails that appear, while also scrolling or using the drop-down menu to see more recent issues. Once you select an issue, use the search tool to look for things like “food,” “beef,” “taro,” “beer,” “cookies,” “diabetes,” or any other food-related search term you can think of.

Write a description of what you found in the issue you selected, considering the following questions:

- What did you learn about food and food culture in Oceania?

- In the descriptions or stories about food that you read, what words or phrases stuck out for you?

- What did the images tell you about food culture in the region?

- How might the magazine’s audience be affected by the choice of food stories and/or advertisements in the issue?

Exploring Food in Song

Listen to the popular Samoan song “ Oka oka laʻu hani ,” and read the lyrics below as you listen. What kinds of foods does the song tell about, and how does the song use food symbolism? What might this tell you about changes in Samoan food culture that took place during the 20th century? (The song was written in the 1930s, and this version, performed by the Five Stars, is from the 1980s.)

|

| Oh oh my honey My dearest honey Who I compare to a can of Hellaby’s [corned beef], Or the very best corned beef, Or some cookies/biscuits from Fiji, Or the very best Chop Suey, With the tomatoes and peas If it’s agreeable for you With the will of your heart We’ll get married In accordance with the law For it’s wrong to just play around There is a devil [That is an act of the devil] And if you have a baby It will be a baby of the night [a demon] Dear, dear, goodbye We are parting ways But the distance isn’t too great Shout inland When you have the time Telephone me at some hour Or write a letter And send it to me by motorcar |

Exploring Food in Film

Watch the documentary “ Samoa Diabetes Epidemic: Part 4 ” from Attitude, and write a one- to two-page summary that reflects your understanding of Sāmoa’s contemporary health crisis. Drawing on what you learned in this chapter and in the film, offer your thoughts on potential solutions to this dietary “tsunami in the Pacific.”

Additional Resources

Teaching Oceania , a resource compiled by the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Center for Pacific Islands Studies (CPIS)

Laudan, R. 2013. “Modern Cuisines: The Globalization of Middling Cuisines, 1920–2000,” in Laudan, Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sharma, J. 2012. “Food and Empire,” in Jeffrey Pilcher, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Food History . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

On “Gastrocolonialism,” see: Craig Santos Perez, “ Facing Hawaiʻi’s Future – Book Review ,” Kenyon Review (July 2013).

- Note that in this text, the word "Samoan" is written without a macron over the a (ā). This follows Samoan linguist expertise, which notes that "Samoan" is not a Samoan word, but an English word, and English does not standardly use macrons. The Samoan word would either be "Gagana Sāmoa," or "Sāmoa," meaning "Samoan language" or "of Samoa," respectively. ↵

an organized society; a state as a political entity.

a qualitative method of data gathering in which the researcher effectively takes part in the process or activity being studied.

the descendants of Austronesian-speaking peoples from modern-day Southern China and Island Southeast Asia, and Papuan-speaking peoples from modern-day Oceania, specifically from the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu; named for the site in New Caledonia where their distinctive pottery (dating as far back as 1600 BCE) was first identified by 20th-century archaeologists; Lapita peoples were masterful oceanic navigators.

dried coconut, from which coconut oil is obtained and used in a range of cosmetic and soap products, among others.

descriptive of maintaining or supporting oneself, especially at a minimal level; may refers to an economy in which peoples procure, produce, and consume their own food and provisions rather than participating in a market, cash-based economy, and thereby purchasing their food and other provisions.

food and drink products that have undergone extensive forms of transformation from their base ingredients, usually by transnational and other very large corporations; often highly stabilized using physical or chemical techniques.

characterized by little physical movement, activity, or exercise.

a shift in dietary consumption and energy expenditure that coincides with economic, demographic, and epidemiological changes.

the systems by which one country or socio-political group rules, governs, or dominates another.

an Indigenous person from present-day Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands.

any systemic relationship in which military, corporate, educational, and media powers (generally those of large and economically powerful nations) shape, influence, and dictate the food choices, options, and knowledge of other nations and territories.

the average amount of something produced or consumed per person; often used in place of "per person" in statistical observances.

Food Studies: Matter, Meaning, Movement Copyright © 2022 by Garrett Hillyer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Digital Object Identifier (DOI)

https://doi.org/10.22215/fsmmm/hg21

Share This Book

Samoan Culture

For most Samoans, the family is of the utmost importance. It is believed that each person is a representative of their family and thus should act in such a way that honours all family members. Each is expected to contribute to the family’s cumulative success. Much emphasis is placed on one’s willingness to share and cooperate with those around them. Indeed, in adherence to fa’a Samoa , many Samoans believe that a person should place their kin before all else.

Family Structure

Extended families (referred to as ‘ aiga potopoto ’) each have an associated land and chiefly title. The more immediate extended family unit is typically known as the ‘ aiga ’. Related aiga will typically live in close proximity to each other. Most commonly, a village will consist of several aiga, each with its own Matai. The Matai is selected on the basis of loyalty and service to the group and is responsible for the well-being of each member of the aiga. Often, the larger the aiga and the more members it has, the more influence it holds in village affairs. The Samoan system of a Matai and aiga helps provide a strong support network and helps individuals understand their responsibilities and duties within the network.

Younger people are expected to defer to their elders and those of higher status than them, such as the Matai. Children are taught from a young age to respect their elders, avoid shaming their family and to sustain certain aspects of tradition. From the age of five, children are expected to play an active role in the family. Samoans will often use the same word to refer to their father and uncles ( tamā ) as well as for their mother and aunts ( tinā ). This reflects the close relationship one may have with extended family.

The aiga potopoto system is also important to help determine the land one inhabits. All Samoans inherit membership and land use rights in the aiga of their parents’ parents. The land that is given to an aiga by the Matai is often the pride of that family. The land is passed down from generation to generation, usually to children who were well behaved and obedient.

Samoans tend to live in proximity with multiple generations of family, wherein parents, their married children and grandchildren all live together in separate houses in one land area. Samoans abroad may live in smaller households. They will maintain family ties with family in Samoa in various ways, such as remittances.

Gender Roles

Samoan society tends to be patriarchal and this is reflected in the household structure. Women often maintain the home and take care of children, whilst men are seen as the primary income providers. Men are typically the key decision-makers; however, matriarchs are not uncommon. For example, within an aiga, there may be a female Matai. She is required to be connected to the family or village by blood and is a daughter of a Matai (specifically an Ali’i). If the Matai of the aiga is a female, she will be the head decision-maker of the family. Moreover, the public influence of women is becoming more apparent and more women are becoming a part of the workforce.

Dating and Marriage

Samoan youth tend to meet at church activities or in the village. Most dating in Samoa is done by the male visiting the female in the presence of her family. During these interactions, gifts may be presented to the female’s family. Messages may be sent back and forth through a friend or communicator (sometimes referred to as a ‘ soa ’). After some time, the family of the female may agree to let the couple marry. Sometimes, permission of the male’s family is also sought prior to marriage. It is generally very important to reach an agreement and forge positive connections between a couple’s families. Some believe in the saying "if you marry someone, you also marry the family".

The first marriage ceremony is generally a civil ceremony whereby the marriage becomes official in terms of the law. After a week or so, a church ceremony is often held for the couple. In contemporary Samoan society, a traditional wedding tends to be a Christian wedding containing many elements of Polynesian culture such as food and dance. One example is the bride’s taualuga dance, which is a dance nearly all Samoan girls are expected to be prepared to do at their wedding. Depending on how closely the two families live, according to fa’a Samoa, most weddings will also contain the traditional exchange of lauga (oratory speeches given by talking chiefs) and gifts (e.g. fine mats and money).

In some areas, couples will live together and may have children prior to marriage. This was once a common practice but is becoming rare in today’s society. The term ‘ usu ’ is considered the polite way to refer to this form of union. It is common for people not to consider a marriage as complete until the first child is born. During this time, some families will exchange a dowry that is usually symbolic.

Get a downloadable PDF that you can share, print and read.

Grow and manage diverse workforces, markets and communities with our new platform

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services Editing Proofreading Rewriting

- Extra Tools Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us About Us Testimonials FAQ

- Studentshare

- Miscellaneous

- Samoan History and Culture

Samoan History and Culture - Essay Example

- Subject: Miscellaneous

- Type: Essay

- Level: Masters

- Pages: 7 (1750 words)

- Downloads: 2

- Author: flatleybeaulah

Extract of sample "Samoan History and Culture"

- Cited: 0 times

- Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied

CHECK THESE SAMPLES OF Samoan History and Culture

Nationalism in pacific settlements, curating a weekend film festival, history and origin of tattooing, tongan cultural diversity, mead's coming of age in samoa as an attempt to popularize anthropology, beyond the all blacks representations, the coming of age, individual and society.

- TERMS & CONDITIONS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- COOKIES POLICY

Improving writing skills since 2002

(855) 4-ESSAYS

Type a new keyword(s) and press Enter to search

Samoan culture.

- Word Count: 845

- Approx Pages: 3

- View my Saved Essays

- Downloads: 18

- Grade level: High School

- Problems? Flag this paper!