Looking for a sneak-peek?

The real magic of Learnerbly can't be expressed in a minute and a half but we know that sometimes seeing is believing. Enter your details below to see a brief tour of our platform.

Not seeing a form? Try refreshing the page.

Why is Learning Important? A Deep Dive Into the Benefits of Being a Lifelong Learner

Free Guide: 5 L&D Trends to Watch Out for in 2021

Learning and development is changing and to stay ahead of the curve you need to know the ways in which it’s doing so.

Learning is important (at least to us here at Learnerbly 😉).

But why is learning important?

Education - both formal and informal - is essential to the development of considerate, compassionate, and cooperative societies, the success of organizations, and the personal pursuit of happiness.

In this article, we unpack what continuous learning and education can mean to the life of each individual, to the organization's they are part of, and to their broader societies.

Looking at this issue from a different angle, we then reflect on some of the potential consequences of not practicing continuous learning—or at least of not prioritizing education in our day-to-day lives.

What Does Learning Even Mean?

Learning is essential to humanity. It’s so embedded in our lives that we rarely consider what it means .

Learning is the process of gaining new skills, knowledge, understanding, and values. This is something people can do by themselves, although it’s generally made easier with education: the process of helping someone or a group of others to learn.

With educational support, learning can happen more efficiently. Education is also how we collect and share all the skills and knowledge we learn individually. Benefitting from education instead of having to build new skills and knowledge by ourselves from scratch is part of what it means to live in a society instead of in isolation.

Learning and education impart more than just knowledge and skills. They also transmit the values, attitudes, and behaviors we have decided to share.

For example, education has helped us to create and maintain the shared belief that when someone does something particularly harmful, they deserve a fair legal trial no matter their crime.

In simple terms, learning and education help hold together human life and civilization as we know it. They are what we use to make our societies better for ourselves, those around us, and those who come after us.

This is why the right to free elementary education is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights , which states that “education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms” and that “it shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups”.

What Does Learning Mean for Us Today?

Learning is not unique to humans. Scientists have observed many different animals teaching their young skills like how to find food and keep themselves safe.

Among humans, educational practices can be traced back practically as far as human life goes. Evidence of teaching and learning has been found from remnants of human life dating back thousands of years BCE—and that’s just where we’ve found written evidence. Oral and practical education (for example, early humans physically teaching their children to hunt and forage for food) likely go back even further.

Learning has continued all over the world throughout the history of human life, in more ways than we have time to write about here. However, the Fourth Industrial Revolution will have a massive impact on how we as a global society approach education going forward.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution refers to the rapid rise of new technologies including big data, artificial intelligence, automation, and the Internet of Things. Life in this new technological landscape demands that we change our approach to education in a number of ways.

One major shift we’ll all have to make is the move from viewing education as something finite (something we do at school and university so we can go into the working world and then never have to study again) to something that keeps going throughout our lives as we gain new skill after new skill.

To face a future of constant technological change, we’ll need to adapt to continuous learning as a new norm. In his book Future Shock, US writer and businessperson Alvin Toffler wrote that “the illiterate of the 21st Century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn and relearn.”

The future of education lies in integrating continuous learning into our everyday personal and professional lives even more than we already do.

This might be why the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra has proposed that compulsory, publicly funded education covers not just elementary school—as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights puts forward—but continuous learning, too.

Sitra cites US American biologist E.O. Wilson, who said “We are drowning in information, but yearn for wisdom. Therefore, the world will be led by those… who are able to compile the correct information at precisely the right moment while thinking critically and making important decisions wisely.”

How Learning Supports Our Wellbeing

We’ve talked about why education is important to society as a whole, but continuous learning also benefits the personal life of anyone who engages with it. Here's how.

Research suggests that people who practice continuous or lifelong learning are happier on average. This may be because lifelong learning helps people to keep developing their passions and interests, which bring us happiness.

Learning about topics that interest us makes most of us feel happy, at least in the moment, as does spending time honing hobbies we are passionate about (which is also an act of lifelong learning!). It stands to reason that building time for these things into your personal life would contribute to your overall happiness.

Continuous learning also helps us to keep pursuing our personal and professional development goals, and all the achievements along the way are a great source of happiness for many of us.

It also helps us keep boredom at bay, which is another way of increasing our happiness.

Several scientific studies have shown that lifelong learning activities can help people maintain better brain function as they age.

One study found that people with Alzheimer’s who practice more learning throughout their lives start to display dementia symptoms later than those who have spent less time learning. In other words, lifelong learning might be able to slow the onset of Alzheimer’s.

Another study found that spending time learning to play a new musical instrument can help delay cognitive decline. A third study found that spending time learning new skills, namely digital photography and quilting, helped elderly people to improve their memories.

How Learning Supports Our Work

Continuous learning—especially in the form of workplace learning—also offers a host of professional benefits for both employees and their organizations. These include:

One key way that continuous learning helps both employees and their companies is by helping people upskill, which means improving their existing skill sets and broadening them with new skills.

Upskilling is good for employees because it equips them with the knowledge and skills they need to pursue their personal and professional development goals, for example by upskilling towards a promotion.

Building a more highly skilled workforce through continuous learning is also beneficial to companies. More skilled employees can do their jobs better and faster, and research shows that companies with a strong learning culture are 52% more productive.

Employees learning new skills to pursue promotions also benefits companies because internal promotion is generally a more time-efficient and cost-effective solution than hiring externally.

Lastly, companies who support their employees' continuous learning boast demonstrably higher staff engagement, which in turn boosts productivity and profitability . This is also beneficial to individual employees, because being engaged at work generally means enjoying your job and finding it meaningful.

Adaptability

As we mentioned earlier, the Fourth Industrial Revolution is pushing employees to pursue continuous learning throughout their lives as they will have to constantly adapt to new knowledge and technological changes, which keep appearing faster and faster.

Engaging in continuous learning means becoming accustomed to incorporating new knowledge all the time, and this is essential in order to keep adapting.

It's important to make learning continuous because this gives people the skills they need to adapt, empowering them to stay competitive in the job market, pursue promotions in their current jobs, and keep pace with knowledge and technological changes in their everyday lives.

Investing in an adaptable workforce by supporting continuous learning is also key to any company that wants to remain competitive and relevant in its industry.

Learning also drives innovation, which describes the new ideas and technological and cultural developments that people come up with to solve problems and improve their societies.

Research shows that companies that have a strong learning culture are 92% more likely to innovate by developing new products and processes, and 56% more likely to be first to market with these new developments.

Innovation is important for society as a whole because the benefits of these new developments can be shared to help improve all of our lives. The fast-tracking of the Covid-19 vaccines are a great example of an organizational innovation that has been developed to combat a global pandemic.

Learning can also help people build the critical thinking skills they need to view problems in new, innovative ways.

What Happens If We Don’t Prioritize Learning?

Another way to reflect on why learning is so important is to think about all the potential negative consequences of not prioritizing learning enough.

The flipside of everything we’ve said in this article is that a society that didn’t prioritize learning would have a lack of shared knowledge and skills for people to benefit from. It would also have a lack of shared ideas and values, which could stoke conflict and war as people and their leaders might struggle more to find common goals on which they can agree.

Not prioritizing learning about other people and cultures would also diminish our ability to understand people who are different from us, and this too would contribute to increased conflict and violence.

People who don’t prioritize continuous learning enough in their own lives are likely to be less happy or fulfilled, as they spend less time exploring their interests and working on personal development.

Elderly people who spend less time on learning are likely to experience faster cognitive degeneration than those who learn regularly.

Companies that don’t prioritize their people’s learning are less productive, less profitable, and have lower staff engagement rates than those that do. They’re also less likely to remain competitive in their industries or produce novel products or services.

People who don’t get enough learning support at work are more likely to be disengaged and see their skills stagnate compared to those who work with companies that invest in their people’s learning.

They will also struggle more with pursuing career development , as they have little support for the upskilling they need to do to grow in their work.

Lastly, if we don’t prioritize learning enough as we face an uncertain—but certainly technologically advancing—future, we will likely have a more difficult time adjusting to the changes ahead of us and making the most of future opportunities.

Continuous learning is important because it helps people to feel happier and more fulfilled in their lives and careers, and to maintain stronger cognitive functioning when they get older.

Making learning continuous helps companies boost their productivity, profitability, adaptability to change, and potential to innovate in their industries.

Learning is important to society as a whole because it helps different groups of people to share knowledge, agree on mutual values, and understand one another better.

Don’t forget to share this post!

Continue reading.

.jpg)

9 tech companies with great employee value propositions

.jpg)

How to define a winning employee value proposition (EVP)

.jpg)

7 tips for upskilling your first-time managers

Get industry insights, guides, and updates sent to your inbox, you will receive a monthly recap of our latest blog posts, expert interviews and product updates..

- How it works

- Our Providers

- Ebooks & Reports

- Help Centre

Visit our sister organization:

THE LEARNING CURVE

a magazine devoted to gaining skills and knowledge.

THE LEARNING AGENCY LAB ’S LEARNING CURVE COVERS THE FIELD OF EDUCATION AND THE SCIENCE OF LEARNING. READ ABOUT METACOGNITIVE THINKING OR DISCOVER HOW TO LEARN BETTER THROUGH OUR ARTICLES, MANY OF WHICH HAVE INSIGHTS FROM EXPERTS WHO STUDY LEARNING.

The Learning Process And Why It Matters

- May 17, 2020

- No Comments

Learning is as essential to being human as breathing. It is something we all do throughout our lives, consciously and unconsciously, at work, at school, at home. But what is learning, exactly? What does it mean to learn?

For much of human history, people assumed the ability to learn was the same thing as intelligence. “If you’re smart, you can learn.” Research today supports a far different conclusion.

Yet still far too little has changed in how people learn.

As a society, we are in need of richer forms of education, where information and knowledge work alongside the creativity and problem-solving that matter in today’s economy.

Experts long argued education was about information, facts, dates and details. The idea was that you should learn in order to become knowledgeable. If you could apply that knowledge then it meant you’d learned something. It turns out that this approach to learning doesn’t always fit the world that we live in today. Nor does it match up with what science has shown works.

In the last several decades, science has found that learning is not a byproduct of natural intelligence, but a process. It turns out to be far more accurate to see learning as a method, or system, towards building understanding. Learning does not occur spontaneously based on your IQ or general aptitude.

Learning depends on many other skills: such as focusing and centering your attention, planning and sticking to a program; tenacity, resilience, and the ability to reflect on information. Using a method to learn – or better said, learning how to learn – is the difference between mastery and rote review. This is how truly effective learning can be achieved.

The precise process or method used for learning has been shown to consistently predict success. After analyzing decades of research, experts revealed a startling, consistent finding. Learning methods strongly affect outcomes across professional fields.

Depending on which learning process students used, scientists were able to closely predict their GPAs.

Learning as a process is about more than science, results and prediction however. It is about how society works today, and the changing role of ‘expertise.’ The omnipresence of the internet and our shifting attention spans mean that facts, and memorizing them, has become less valuable.

Technology tends to handle details, logistics and facts for us. The bigger questions instead become: how do our brains really work, and how do we gain mastery?

Finding the best way to learn in the first place, means to set rigorous targets. What is it you truly want or need to learn?

Within the bounds of these targets, it should be normal to expect struggle and setbacks. Still most individuals need the promise of an eventual return from their efforts. Goals should be realistic, so that it feels possible to learn – but also ambitious enough to spark excitement.

Ambition surrounding a goal can also carry us through difficulty and hardship on the path.

Recognizing that struggle is often a part of learning prevents us from becoming too discouraged, and giving up entirely. That is – ‘learning is a process.’

Learning as a process means that through method, effort, focus, and practice, we can get a lot better at gaining expertise.

Here are six steps to outline the key areas necessary to learn effectively:

Learning is about creating a sense of meaning. The ability to connect a topic to another subject you can about, can make it much simpler to learn. Consider a cherished activity or topic, and figure out how it can be connected to the new field of interest. Involve someone you know or love. If you want to learn to sew, sew something for someone you love.

The other key tool is making learning active, making it meaningful. By active, we mean mentally active. So ask yourself lots of questions as you learn or study something. What does this mean? What does it matter? Could I explain to a friend?

Braindumps are particularly effective. Just write down our thoughts after studying something. As learning researcher Pooja Agarwal argues “No matter what you call it, try this quick retrieval strategy during your instruction before the end of the school year. Here’s how it works:Pause your lesson, lecture, or activity.Ask students to write down everything they can remember. Continue your lesson, lecture, or activity.’”

Learning often involves making errors. In fact, it’s inevitable.

Learning can also be understood as knowledge management. As in professional management, success requires forethought, targets and timelines. Goal setting means creating precise targets without vagueness or generalization. Realistic, specific goals keep learners from becoming discouraged.

If a goal is too large or abstract, it can be difficult to picture achieving it. The learner might lose their drive, because the goal is too far in the future. On the other hand, rigor in choosing your learning goals is crucial. Learning material ought to be challenging, rather than easy, or based on already known concepts.

Reach beyond the comfort zone to ideas slightly beyond your grasp. This is where learning occurs.

At the same time, be sure to learn in chunks. To gain knowledge we need to have a dedicated way to a aquire that knowledge and organize it in a way that makes sense. Practically speaking, set aside time for learning and try for small, 30 minutes studying sessions.

Also make sure to think about organizing your learning in ways that build on prior knowledge. Indeed, what you know is that best predictor of what you can learn.

Not all practice is made equal however. Superior practice involves being mentally awake, where the mind is at work. Rote memorization or re-readi ng for instance are not active as practice or learning modes. Much better are non-passive techniques, like creating small tests and quizzes, or imagining explaining the topic to a third party.

Not only should learning build on what has been done already, but it should include being able to dredge up older, related topics. A famous study suggested students who tried to remember a passage without looking at it learned it more thoroughly than those who just read it again and again. To give an example, after reading this article, there would be more learning benefits from creating a quiz of related questions, than going back over the text.

In short, there’s no such things as effortless learning. All learning takes work.

If you imagine being better at presenting Powerpoints, present more often! It’s also possible to improve upon your knowledge base through self-questioning and self-explanation. Ask: Is this really logical? Why is this thing that way, and not another way? Making an idea clear to another person, or yourself, is one of the best ways to gain knowledge. Working on a team is positive for that reason: by exchanging information, each team member has the chance to improve.

Teaching as a means to learn is certainly a challenge. While extending our knowledge, it is important to support the affective or emotive self. Keep track of improvements and any headway made to keep up morale.

Graphic organizers, brain or idea mapping can equally be used to see relationships emerge in a mass of knowledge. Visually seeing the way pieces of information or certain skills connect on a page builds understanding. Aim to see the same information in new ways, by combining topics. Connections become more obvious through combining.

This part is about seeing beyond the cut and dry. What is the bigger picture in how this topic relates to others? Try posing questions about the connections between topics. How does this subject work? Think abstractly.

Ultimately this means beginning by thinking like an expert in the field. Learning plant biology by thinking like a plant biologist. Understand neuroscience by conceptualizing the field the way a real neuroscientist would.

Finally towards the end of a learning process, consider what knowledge or skills have been gathered. Have some previous thought processes shifted? What is the connection between this content and your other knowledge bases? In essence, have I learned something? What’s next?

If you have other thoughts about the learning process, drop them in the comments. I’ll be sure to respond. -Ulrich Boser

Download the PDF File Here

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Essay on Lifelong Learning

Students are often asked to write an essay on Lifelong Learning in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Lifelong Learning

What is lifelong learning.

Lifelong learning is the idea of always finding new things to learn, no matter how old you are. It’s like being in school your whole life, but without the tests and homework! It’s about keeping your mind active and always being curious.

Why is Lifelong Learning Important?

Benefits of lifelong learning.

Lifelong learning can make life more interesting. It can help us make better decisions and solve problems more easily. It can even help us live longer, healthier lives. Plus, it’s fun to learn new things!

How to Practice Lifelong Learning

Practicing lifelong learning can be as simple as reading a book, taking a class, or even just asking questions. It’s about staying curious and open to new ideas. So keep exploring, keep asking, and keep learning!

250 Words Essay on Lifelong Learning

Understanding lifelong learning, why lifelong learning is important.

Lifelong learning is very important for many reasons. First, it helps us to stay updated. The world is always changing, and we need to keep up with it. If we stop learning, we might miss out on new things. Second, it makes us more interesting. People who keep learning are often more fun to talk to. They have lots of new ideas and stories to share. Third, it keeps our minds sharp. Just like our bodies, our minds need exercise too. Learning is a great way to give our minds a workout.

Ways to Practice Lifelong Learning

There are many ways to keep learning. You can read books, take online courses, or join clubs. You can also learn from your friends and family. Everyone has something to teach, and everyone has something to learn.

The Benefits of Lifelong Learning

Lifelong learning has many benefits. It can help you get better at your job, make you smarter, and even make you happier. People who keep learning often feel more confident and satisfied with their lives.

In conclusion, lifelong learning is a journey that never ends. It is a wonderful way to keep growing, stay interesting, and live a happy life. So, let’s promise ourselves to never stop learning, no matter how old we are.

500 Words Essay on Lifelong Learning

Lifelong Learning is a continuous process of gaining new knowledge and skills throughout one’s life. It’s not just about school or college, but also about learning from everyday experiences. It could be learning a new hobby, a new language, or even about a new culture. The main idea is to keep growing and expanding your mind all the time.

Secondly, it helps you adapt to changes. The world is always changing, with new technologies, new ideas, and new ways of doing things. By continuing to learn, you can keep up with these changes and make the most of new opportunities.

Finally, lifelong learning can make life more interesting and enjoyable. It can help you discover new interests, meet new people, and even achieve personal goals.

How to Practice Lifelong Learning?

Practicing lifelong learning is easier than you might think. Here are a few simple ways you can include learning in your daily life.

Secondly, try new things. This could be a new hobby, a new sport, or even a new food. Trying new things can help you discover what you enjoy and what you’re good at.

Lastly, reflect on your experiences. Think about what you’ve done, what you’ve learned, and how you can use this knowledge in the future.

Lifelong learning has many benefits. It can improve your skills and knowledge, making you more valuable in the job market. It can also improve your self-confidence and self-esteem, helping you feel more capable and successful.

Furthermore, lifelong learning can help you connect with others. By learning about different cultures, ideas, and perspectives, you can understand and relate to people better.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition (2000)

Chapter: 10 conclusions, 10 conclusions.

The pace at which science proceeds sometimes seems alarmingly slow, and impatience and hopes both run high when discussions turn to issues of learning and education. In the field of learning, the past quarter century has been a period of major research advances. Because of the many new developments, the studies that resulted in this volume were conducted to appraise the scientific knowledge base on human learning and its application to education. We evaluated the best and most current scientific data on learning, teaching, and learning environments. The objective of the analysis was to ascertain what is required for learners to reach deep understanding, to determine what leads to effective teaching, and to evaluate the conditions that lead to supportive environments for teaching and learning.

A scientific understanding of learning includes understanding about learning processes, learning environments, teaching, sociocultural processes, and the many other factors that contribute to learning. Research on all of these topics, both in the field and in laboratories, provides the fundamental knowledge base for understanding and implementing changes in education.

This volume discusses research in six areas that are relevant to a deeper understanding of students’ learning processes: the role of prior knowledge in learning, plasticity and related issues of early experience upon brain development, learning as an active process, learning for understanding, adaptive expertise, and learning as a time-consuming endeavor. It reviews research in five additional areas that are relevant to teaching and environments that support effective learning: the importance of social and cultural contexts, transfer and the conditions for wide application of learning, subject matter uniqueness, assessment to support learning, and the new educational technologies.

LEARNERS AND LEARNING

Development and learning competencies.

Children are born with certain biological capacities for learning. They can recognize human sounds; can distinguish animate from inanimate objects; and have an inherent sense of space, motion, number, and causality. These raw capacities of the human infant are actualized by the environment surrounding a newborn. The environment supplies information, and equally important, provides structure to the information, as when parents draw an infant’s attention to the sounds of her or his native language.

Thus, developmental processes involve interactions between children’s early competencies and their environmental and interpersonal supports. These supports serve to strengthen the capacities that are relevant to a child’s surroundings and to prune those that are not. Learning is promoted and regulated by the children’s biology and their environments. The brain of a developing child is a product, at the molecular level, of interactions between biological and ecological factors. Mind is created in this process.

The term “development” is critical to understanding the changes in children’s conceptual growth. Cognitive changes do not result from mere accretion of information, but are due to processes involved in conceptual reorganization. Research from many fields has supplied the key findings about how early cognitive abilities relate to learning. These include the following:

“Privileged domains:” Young children actively engage in making sense of their worlds. In some domains, most obviously language, but also for biological and physical causality and number, they seem predisposed to learn.

Children are ignorant but not stupid: Young children lack knowledge, but they do have abilities to reason with the knowledge they understand.

Children are problem solvers and, through curiosity, generate questions and problems: Children attempt to solve problems presented to them, and they also seek novel challenges. They persist because success and understanding are motivating in their own right.

Children develop knowledge of their own learning capacities— metacognition—very early. This metacognitive capacity gives them the ability to plan and monitor their success and to correct errors when necessary.

Children’ natural capabilities require assistance for learning: Children’s early capacities are dependent on catalysts and mediation. Adults play a critical role in promoting children’s curiosity and persistence by directing children’s attention, structuring their experiences, supporting their

learning attempts, and regulating the complexity and difficulty of levels of information for them.

Neurocognitive research has contributed evidence that both the developing and the mature brain are structurally altered during learning. For example, the weight and thickness of the cerebral cortex of rats is altered when they have direct contact with a stimulating physical environment and an interactive social group. The structure of the nerve cells themselves is correspondingly altered: under some conditions, both the cells that provide support to the neurons and the capillaries that supply blood to the nerve cells may be altered as well. Learning specific tasks appears to alter the specific regions of the brain appropriate to the task. In humans, for example, brain reorganization has been demonstrated in the language functions of deaf individuals, in rehabilitated stroke patients, and in the visual cortex of people who are blind from birth. These findings suggest that the brain is a dynamic organ, shaped to a great extent by experience and by what a living being does.

Transfer of Learning

A major goal of schooling is to prepare students for flexible adaptation to new problems and settings. Students’ abilities to transfer what they have learned to new situations provides an important index of adaptive, flexible learning; seeing how well they do this can help educators evaluate and improve their instruction. Many approaches to instruction look equivalent when the only measure of learning is memory for facts that were specifically presented. Instructional differences become more apparent when evaluated from the perspective of how well the learning transfers to new problems and settings. Transfer can be explored at a variety of levels, including transfer from one set of concepts to another, one school subject to another, one year of school to another, and across school and everyday, nonschool activities.

People’s abilitiy to transfer what they have learned depends upon a number of factors:

People must achieve a threshold of initial learning that is sufficient to support transfer. This obvious point is often overlooked and can lead to erroneous conclusions about the effectiveness of various instructional approaches. It takes time to learn complex subject matter, and assessments of transfer must take into account the degree to which original learning with understanding was accomplished.

Spending a lot of time (“time on task”) in and of itself is not sufficient to ensure effective learning. Practice and getting familiar with subject matter take time, but most important is how people use their time while

learning. Concepts such as “deliberate practice” emphasize the importance of helping students monitor their learning so that they seek feedback and actively evaluate their strategies and current levels of understanding. Such activities are very different from simply reading and rereading a text.

Learning with understanding is more likely to promote transfer than simply memorizing information from a text or a lecture. Many classroom activities stress the importance of memorization over learning with understanding. Many, as well, focus on facts and details rather than larger themes of causes and consequences of events. The shortfalls of these approaches are not apparent if the only test of learning involves tests of memory, but when the transfer of learning is measured, the advantages of learning with understanding are likely to be revealed.

Knowledge that is taught in a variety of contexts is more likely to support flexible transfer than knowledge that is taught in a single context. Information can become “context-bound” when taught with context-specific examples. When material is taught in multiple contexts, people are more likely to extract the relevant features of the concepts and develop a more flexible representation of knowledge that can be used more generally.

Students develop flexible understanding of when, where, why, and how to use their knowledge to solve new problems if they learn how to extract underlying themes and principles from their learning exercises. Understanding how and when to put knowledge to use—known as conditions of applicability—is an important characteristic of expertise. Learning in multiple contexts most likely affects this aspect of transfer.

Transfer of learning is an active process. Learning and transfer should not be evaluated by “one-shot” tests of transfer. An alternative assessment approach is to consider how learning affects subsequent learning, such as increased speed of learning in a new domain. Often, evidence for positive transfer does not appear until people have had a chance to learn about the new domain—and then transfer occurs and is evident in the learner’s ability to grasp the new information more quickly.

All learning involves transfer from previous experiences. Even initial learning involves transfer that is based on previous experiences and prior knowledge. Transfer is not simply something that may or may not appear after initial learning has occurred. For example, knowledge relevant to a particular task may not automatically be activated by learners and may not serve as a source of positive transfer for learning new information. Effective teachers attempt to support positive transfer by actively identifying the strengths that students bring to a learning situation and building on them, thereby building bridges between students’ knowledge and the learning objectives set out by the teacher.

Sometimes the knowledge that people bring to a new situation impedes subsequent learning because it guides thinking in wrong directions.

For example, young children’s knowledge of everyday counting-based arithmetic can make it difficult for them to deal with rational numbers (a larger number in the numerator of a fraction does not mean the same thing as a larger number in the denominator); assumptions based on everyday physical experiences can make it difficult for students to understand physics concepts (they think a rock falls faster than a leaf because everyday experiences include other variables, such as resistance, that are not present in the vacuum conditions that physicists study), and so forth. In these kinds of situations, teachers must help students change their original conceptions rather than simply use the misconceptions as a basis for further understanding or leaving new material unconnected to current understanding.

Competent and Expert Performance

Cognitive science research has helped us understand how learners develop a knowledge base as they learn. An individual moves from being a novice in a subject area toward developing competency in that area through a series of learning processes. An understanding of the structure of knowledge provides guidelines for ways to assist learners acquire a knowledge base effectively and efficiently. Eight factors affect the development of expertise and competent performance:

Relevant knowledge helps people organize information in ways that support their abilities to remember.

Learners do not always relate the knowledge they possess to new tasks, despite its potential relevance. This “disconnect” has important implications for understanding differences between usable knowledge (which is the kind of knowledge that experts have developed) and less-organized knowledge, which tends to remain “inert.”

Relevant knowledge helps people to go beyond the information given and to think in problem representations, to engage in the mental work of making inferences, and to relate various kinds of information for the purpose of drawing conclusions.

An important way that knowledge affects performances is through its influences on people’s representations of problems and situations. Different representations of the same problem can make it easy, difficult, or impossible to solve.

The sophisticated problem representations of experts are the result of well-organized knowledge structures. Experts know the conditions of applicability of their knowledge, and they are able to access the relevant knowledge with considerable ease.

Different domains of knowledge, such as science, mathematics, and history, have different organizing properties. It follows, therefore, that to

have an in-depth grasp of an area requires knowledge about both the content of the subject and the broader structural organization of the subject.

Competent learners and problem solvers monitor and regulate their own processing and change their strategies as necessary. They are able to make estimates and “educated guesses.”

The study of ordinary people under everyday cognition provides valuable information about competent cognitive performances in routine settings. Like the work of experts, everyday competencies are supported by sets of tools and social norms that allow people to perform tasks in specific contexts that they often cannot perform elsewhere.

Conclusions

Everyone has understanding, resources, and interests on which to build. Learning a topic does not begin from knowing nothing to learning that is based on entirely new information. Many kinds of learning require transforming existing understanding, especially when one’s understanding needs to be applied in new situations. Teachers have a critical role in assisting learners to engage their understanding, building on learners’ understandings, correcting misconceptions, and observing and engaging with learners during the processes of learning.

This view of the interactions of learners with one another and with teachers derives from generalizations about learning mechanisms and the conditions that promote understanding. It begins with the obvious: learning is embedded in many contexts. The most effective learning occurs when learners transport what they have learned to various and diverse new situations. This view of learning also includes the not so obvious: young learners arrive at school with prior knowledge that can facilitate or impede learning. The implications for schooling are many, not the least of which is that teachers must address the multiple levels of knowledge and perspectives of children’s prior knowledge, with all of its inaccuracies and misconceptions.

Effective comprehension and thinking require a coherent understanding of the organizing principles in any subject matter; understanding the essential features of the problems of various school subjects will lead to better reasoning and problem solving; early competencies are foundational to later complex learning; self-regulatory processes enable self-monitoring and control of learning processes by learners themselves.

Transfer and wide application of learning are most likely to occur when learners achieve an organized and coherent understanding of the material; when the situations for transfer share the structure of the original

learning; when the subject matter has been mastered and practiced; when subject domains overlap and share cognitive elements; when instruction includes specific attention to underlying principles; and when instruction explicitly and directly emphasizes transfer.

Learning and understanding can be facilitated in learners by emphasizing organized, coherent bodies of knowledge (in which specific facts and details are embedded), by helping learners learn how to transfer their learning, and by helping them use what they learn.

In-depth understanding requires detailed knowledge of the facts within a domain. The key attribute of expertise is a detailed and organized understanding of the important facts within a specific domain. Education needs to provide children with sufficient mastery of the details of particular subject matters so that they have a foundation for further exploration within those domains.

Expertise can be promoted in learners. The predominant indicator of expert status is the amount of time spent learning and working in a subject area to gain mastery of the content. Secondarily, the more one knows about a subject, the easier it is to learn additional knowledge.

TEACHERS AND TEACHING

The portrait we have sketched of human learning and cognition emphasizes learning for in-depth comprehension. The major ideas that have transformed understanding of learning also have implications for teaching.

Teaching for In-Depth Learning

Traditional education has tended to emphasize memorization and mastery of text. Research on the development of expertise, however, indicates that more than a set of general problem-solving skills or memory for an array of facts is necessary to achieve deep understanding. Expertise requires well-organized knowledge of concepts, principles, and procedures of inquiry. Various subject disciplines are organized differently and require an array of approaches to inquiry. We presented a discussion of the three subject areas of history, mathematics, and science learning to illustrate how the structure of the knowledge domain guides both learning and teaching.

Proponents of the new approaches to teaching engage students in a variety of different activities for constructing a knowledge base in the subject domain. Such approaches involve both a set of facts and clearly defined principles. The teacher’s goal is to develop students’ understanding of a given topic, as well as to help them develop into independent and thoughtful problem solvers. One way to do this is by showing students that they already have relevant knowledge. As students work through different prob-

lems that a teacher presents, they develop their understanding into principles that govern the topic.

In mathematics for younger (first- and second-grade) students, for example, cognitively guided instruction uses a variety of classroom activities to bring number and counting principles into students’ awareness, including snack-time sharing for fractions, lunch count for number, and attendance for part-whole relationships. Through these activities, a teacher has many opportunities to observe what students know and how they approach solutions to problems, to introduce common misconceptions to challenge students’ thinking, and to present more advanced discussions when the students are ready.

For older students, model-based reasoning in mathematics is an effective approach. Beginning with the building of physical models, this approach develops abstract symbol system-based models, such as algebraic equations or geometry-based solutions. Model-based approaches entail selecting and exploring the properties of a model and then applying the model to answer a question that interests the student. This important approach emphasizes understanding over routine memorization and provides students with a learning tool that enables them to figure out new solutions as old ones become obsolete.

These new approaches to mathematics operate from knowledge that learning involves extending understanding to new situations, a guiding principle of transfer ( Chapter 3 ); that young children come to school with early mathematics concepts ( Chapter 4 ); that learners cannot always identify and call up relevant knowledge (Chapters 2 , 3 , and 4 ); and that learning is promoted by encouraging children to try out the ideas and strategies they bring with them to school-based learning ( Chapter 6 ). Students in classes that use the new approaches do not begin learning mathematics by sitting at desks and only doing computational problems. Rather, they are encouraged to explore their own knowledge and to invent strategies for solving problems and to discuss with others why their strategies work or do not work.

A key aspect of the new ways of teaching science is to focus on helping students overcome deeply rooted misconceptions that interfere with learning. Especially in people’s knowledge of the physical, it is clear that prior knowledge, constructed out of personal experiences and observations— such as the conception that heavy objects fall faster than light objects—can conflict with new learning. Casual observations are useful for explaining why a rock falls faster than a leaf, but they can lead to misconceptions that are difficult to overcome. Misconceptions, however, are also the starting point for new approaches to teaching scientific thinking. By probing students’ beliefs and helping them develop ways to resolve conflicting views, teachers can guide students to construct coherent and broad understandings of scientific concepts. This and other new approaches are major break-

throughs in teaching science. Students can often answer fact-based questions on tests that imply understanding, but misconceptions will surface as the students are questioned about scientific concepts.

Chèche Konnen (“search for knowledge” in Haitian Creole) was presented as an example of new approaches to science learning for grade school children. The approach focuses upon students’ personal knowledge as the foundations of sense-making. Further, the approach emphasizes the role of the specialized functions of language, including the students’ own language for communication when it is other than English; the role of language in developing skills of how to “argue” the scientific “evidence” they arrive at; the role of dialogue in sharing information and learning from others; and finally, how the specialized, scientific language of the subject matter, including technical terms and definitions, promote deep understanding of the concepts.

Teaching history for depth of understanding has generated new approaches that recognize that students need to learn about the assumptions any historian makes for connecting events and schemes into a narrative. The process involves learning that any historical account is a history and not the history. A core concept guiding history learning is how to determine, from all of the events possible to enumerate, the ones to single out as significant. The “rules for determining historical significance” become a lightening rod for class discussions in one innovative approach to teaching history. Through this process, students learn to understand the interpretative nature of history and to understand history as an evidentiary form of knowledge. Such an approach runs counter to the image of history as clusters of fixed names and dates that students need to memorize. As with the Chèche Konnen example of science learning, mastering the concepts of historical analysis, developing an evidentiary base, and debating the evidence all become tools in the history toolbox that students carry with them to analyze and solve new problems.

Expert Teachers

Expert teachers know the structure of the knowledge in their disciplines. This knowledge provides them with cognitive roadmaps to guide the assignments they give students, the assessments they use to gauge student progress, and the questions they ask in the give-and-take of classroom life. Expert teachers are sensitive to the aspects of the subject matter that are especially difficult and easy for students to grasp: they know the conceptual barriers that are likely to hinder learning, so they watch for these tell-tale signs of students’ misconceptions. In this way, both students’ prior knowledge and teachers’ knowledge of subject content become critical components of learners’ growth.

Subject-matter expertise requires well-organized knowledge of concepts and inquiry procedures. Similarly, studies of teaching conclude that expertise consists of more than a set of general methods that can be applied across all subject matter. These two sets of research-based findings contradict the common misconception about what teachers need to know in order to design effective learning environments for students. Both subject-matter knowledge and pedagogical knowledge are important for expert teaching because knowledge domains have unique structures and methods of inquiry associated with them.

Accomplished teachers also assess their own effectiveness with their students. They reflect on what goes on in the classroom and modify their teaching plans accordingly. Thinking about teaching is not an abstract or esoteric activity. It is a disciplined, systematic approach to professional development. By reflecting on and evaluating one’s own practices, either alone or in the company of a critical colleague, teachers develop ways to change and improve their practices, like any other opportunity for learning with feedback.

Teachers need expertise in both subject matter content and in teaching.

Teachers need to develop understanding of the theories of knowledge (epistemologies) that guide the subject-matter disciplines in which they work.

Teachers need to develop an understanding of pedagogy as an intellectual discipline that reflects theories of learning, including knowledge of how cultural beliefs and the personal characteristics of learners influence learning.

Teachers are learners and the principles of learning and transfer for student learners apply to teachers.

Teachers need opportunities to learn about children’s cognitive development and children’s development of thought (children’s epistemologies) in order to know how teaching practices build on learners’ prior knowledge.

Teachers need to develop models of their own professional development that are based on lifelong learning, rather than on an “updating” model of learning, in order to have frameworks to guide their career planning.

LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS

Tools of technology.

Technology has become an important instrument in education. Computer-based technologies hold great promise both for increasing access to knowledge and as a means of promoting learning. The public imagination has been captured by the capacity of information technologies to centralize and organize large bodies of knowledge; people are excited by the prospect of information networks, such as the Internet, for linking students around the globe into communities of learners.

There are five ways that technology can be used to help meet the challenges of establishing effective learning environments:

Bringing real-world problems into classrooms through the use of videos, demonstrations, simulations, and Internet connections to concrete data and working scientists.

Providing “scaffolding” support to augment what learners can do and reason about on their path to understanding. Scaffolding allows learners to participate in complex cognitive performances, such as scientific visualization and model-based learning, that is more difficult or impossible without technical support.

Increasing opportunities for learners to receive feedback from software tutors, teachers, and peers; to engage in reflection on their own learning processes; and to receive guidance toward progressive revisions that improve their learning and reasoning.

Building local and global communities of teachers, administrators, students, parents, and other interested learners.

Expanding opportunities for teachers’ learning.

An important function of some of the new technologies is their use as tools of representation. Representational thinking is central to in-depth understanding and problem representation is one of the skills that distinguish subject experts from novices. Many of the tools also have the potential to provide multiple contexts and opportunities for learning and transfer, for both student-learners and teacher-learners. Technologies can be used as learning and problem-solving tools to promote both independent learning and collaborative networks of learners and practitioners.

The use of new technologies in classrooms, or the use of any learning aid for that matter, is never solely a technical matter. The new electronic technologies, like any other educational resource, are used in a social environment and are, therefore, mediated by the dialogues that students have with each other and the teacher.

Educational software needs to be developed and implemented with a full understanding of the principles of learning and developmental psychology. Many new issues arise when one considers how to educate teachers to use new technologies effectively: What do they need to know about learning processes? What do they need to know about the technologies? What kinds of training are most effective for helping teachers use high-quality instructional programs? Understanding the issues that affect teachers who will be using new technologies is just as pressing as questions of the learning potential and developmental appropriateness of the technologies for children.

Assessment to Support Learning

Assessment and feedback are crucial for helping people learn. Assessment that is consistent with principles of learning and understanding should:

Mirror good instruction.

Happen continuously, but not intrusively, as a part of instruction.

Provide information (to teachers, students, and parents) about the levels of understanding that students are reaching.

Assessment should reflect the quality of students’ thinking, as well as what specific content they have learned. For this purpose, achievement measurement must consider cognitive theories of performance. Frameworks that integrate cognition and context in assessing achievement in science, for example, describe performance in terms of the content and process task demands of the subject matter and the nature and extent of cognitive activities likely to be observed in a particular assessment situation. The frameworks provide a basis for examining performance assessments that are designed to measure reasoning, understanding, and complex problem solving.

The nature and purposes of an assessment also influence the specific cognitive activities that are expressed by the student. Some assessment tasks emphasize a particular performance, such as explanation, but deemphasize others, such as self-monitoring. The kind and quality of cognitive activities observed in an assessment situation are functions of the content and process demands of the tasks involved. Similarly, the task demands for process skills can be conceived along a continuum from constrained to open. In open situations, explicit directions are minimized in order to see how students generate and carry out appropriate process skills as they solve problems. Characterizing assessments in terms of components of competence and the content and process demands of the subject matter brings specificity to assessment objectives, such as “higher level thinking” and “deep understanding.” This approach links specific content with the

underlying cognitive processes and the performance objectives that the teacher has in mind. With articulated objectives and an understanding of the correspondence between task features and cognitive activities, the content and process demands of tasks are brought into alignment with the performance objectives.

Effective teachers see assessment opportunities in ongoing classroom learning situations. They continually attempt to learn about students’ thinking and understanding and make it relevant to current learning tasks. They do a great deal of on-line monitoring of both group work and individual performances, and they attempt to link current activities to other parts of the curriculum and to students’ daily life experiences.

Students at all levels, but increasingly so as they progress through the grades, focus their learning attention and energies on the parts of the curriculum that are assessed. In fact, the art of being a good student, at least in the sense of getting good grades, is tied to being able to anticipate what will be tested. This means that the information to be tested has the greatest influence on guiding students’ learning. If teachers stress the importance of understanding but then test for memory of facts and procedures, it is the latter that students will focus on. Many assessments developed by teachers overemphasize memory for procedures and facts; expert teachers, by contrast, align their assessment practices with their instructional goals of depth-of-understanding.

Learning and Connections to Community

Outside of formal school settings, children participate in many institutions that foster their learning. For some of these institutions, promoting learning is part of their goals, including after-school programs, as in such organizations as Boy and Girl Scout Associations and 4–H Clubs, museums, and religious education. In other institutions or activities, learning is more incidental, but learning takes place nevertheless. These learning experiences are fundamental to children’s—and adults’ —lives since they are embedded in the culture and the social structures that organize their daily activities. None of the following points about the importance of out-of-school learning institutions, however, should be taken to deemphasize the central role of schools and the kinds of information that can be most efficiently and effectively taught there.

A key environment for learning is the family. In the United States, many families hold a learning agenda for their children and seek opportunities for their children to engage with the skills, ideas, and information in their communities. Even when family members do not focus consciously on instructional roles, they provide resources for children’s learning that are relevant to school and out-of-school ideas through family activities, the funds of

knowledge available within extended families and their communities, and the attitudes that family members display toward the skills and values of schooling.

The success of the family as a learning environment, especially in the early years, has provided inspiration and guidance for some of the changes recommended in schools. The rapid development of children from birth to ages 4 or 5 is generally supported by family interactions in which children learn by observing and interacting with others in shared endeavors. Conversations and other interactions that occur around events of interest with trusted and skilled adults and child companions are especially powerful environments for learning. Many of the recommendations for changes in schools can be seen as extensions of the learning activities that occur within families. In addition, recommendations to include families in classroom activities and educational planning hold promise of bringing together two powerful systems for supporting children’s learning.

Classroom environments are positively influenced by opportunities to interact with parents and community members who take interest in what they are doing. Teachers and students more easily develop a sense of community as they prepare to discuss their projects with people who come from outside the school and its routines. Outsiders can help students appreciate similarities and differences between classroom environments and everyday environments; such experiences promote transfer of learning by illustrating the many contexts for applying what they know.

Parents and business leaders represent examples of outside people who can have a major impact on student learning. Broad-scale participation in school-based learning rarely happens by accident. It requires clear goals and schedules and relevant curricula that permit and guide adults in ways to help children learn.

Designing effective learning environments includes considering the goals for learning and goals for students. This comparison highlights the fact that there are various means for approaching goals of learning, and furthermore, that goals for students change over time. As goals and objectives have changed, so has the research base on effective learning and the tools that students use. Student populations have also shifted over the years. Given these many changes in student populations, tools of technology, and society’s requirements, different curricula have emerged along with needs for new pedagogical approaches that are more child-centered and more culturally sensitive, all with the objectives of promoting effective learning and adaptation (transfer). The requirement for teachers to meet such a diversity of challenges also illustrates why assessment needs to be a tool to help teach-

ers determine if they have achieved their objectives. Assessment can guide teachers in tailoring their instruction to individual students’ learning needs and, collaterally, inform parents of their children’s progress.

Supportive learning environments, which are the social and organizational structures in which students and teachers operate, need to focus on the characteristics of classroom environments that affect learning; the environments as created by teachers for learning and feedback; and the range of learning environments in which students participate, both in and out of school.

Classroom environments can be positively influenced by opportunities to interact with others who affect learners, particularly families and community members, around school-based learning goals.

New tools of technology have the potential of enhancing learning in many ways. The tools of technology are creating new learning environments, which need to be assessed carefully, including how their use can facilitate learning, the types of assistance that teachers need in order to incorporate the tools into their classroom practices, the changes in classroom organization that are necessary for using technologies, and the cognitive, social, and learning consequences of using these new tools.

First released in the Spring of 1999, How People Learn has been expanded to show how the theories and insights from the original book can translate into actions and practice, now making a real connection between classroom activities and learning behavior. This edition includes far-reaching suggestions for research that could increase the impact that classroom teaching has on actual learning.

Like the original edition, this book offers exciting new research about the mind and the brain that provides answers to a number of compelling questions. When do infants begin to learn? How do experts learn and how is this different from non-experts? What can teachers and schools do-with curricula, classroom settings, and teaching methods—to help children learn most effectively? New evidence from many branches of science has significantly added to our understanding of what it means to know, from the neural processes that occur during learning to the influence of culture on what people see and absorb.

How People Learn examines these findings and their implications for what we teach, how we teach it, and how we assess what our children learn. The book uses exemplary teaching to illustrate how approaches based on what we now know result in in-depth learning. This new knowledge calls into question concepts and practices firmly entrenched in our current education system.

Topics include:

- How learning actually changes the physical structure of the brain.

- How existing knowledge affects what people notice and how they learn.

- What the thought processes of experts tell us about how to teach.

- The amazing learning potential of infants.

- The relationship of classroom learning and everyday settings of community and workplace.

- Learning needs and opportunities for teachers.

- A realistic look at the role of technology in education.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 The learning process

When my son Michael was old enough to talk, and being an eager but naïve dad, I decided to bring Michael to my educational psychology class to demonstrate to my students “how children learn”. In one task I poured water from a tall drinking glass to a wide glass pie plate, which according to Michael changed the “amount” of water—there was less now than it was in the pie plate. I told him that, on the contrary, the amount of water had stayed the same whether it was in the glass or the pie plate. He looked at me a bit strangely, but complied with my point of view—agreeing at first that, yes, the amount had stayed the same. But by the end of the class session he had reverted to his original position: there was less water, he said, when it was poured into the pie plate compared to being poured into the drinking glass. So much for demonstrating “learning”!

(Kelvin Seifert)

Learning is generally defined as relatively permanent changes in behavior, skills, knowledge, or attitudes resulting from identifiable psychological or social experiences. A key feature is permanence: changes do not count as learning if they are temporary. You do not “learn” a phone number if you forget it the minute after you dial the number; you do not “learn” to eat vegetables if you only do it when forced. The change has to last. Notice, though, that learning can be physical, social, or emotional as well as cognitive. You do not “learn” to sneeze simply by catching cold, but you do learn many skills and behaviors that are physically based, such as riding a bicycle or throwing a ball. You can also learn to like (or dislike) a person, even though this change may not happen deliberately.

Each year after that first visit to my students, while Michael was still a preschooler, I returned with him to my ed-psych class to do the same “learning demonstrations”. And each year Michael came along happily, but would again fail the task about the drinking glass and the pie plate. He would comply briefly if I “suggested” that the amount of water stayed the same no matter which way it was poured, but in the end he would still assert that the amount had changed. He was not learning this bit of conventional knowledge, in spite of my repeated efforts.

But the year he turned six, things changed. When I told him it was time to visit my ed-psych class again, he readily agreed and asked: “Are you going to ask me about the water in the drinking glass and pie plate again?” I said yes, I was indeed planning to do that task again. “That’s good”, he responded, “because I know that the amount stays the same even after you pour it. But do you want me to fake it this time? For your students’ sake?”

Teachers’ perspectives on learning

For teachers, learning usually refers to things that happen in schools or classrooms, even though every teacher can of course describe examples of learning that happen outside of these places. Even Michael, at age 6, had begun realizing that what counted as “learning” in his dad’s educator-type mind was something that happened in a classroom, under the supervision of a teacher (me). For me, as for many educators, the term has a more specific meaning than for many people less involved in schools. In particular, teachers’ perspectives on learning often emphasize three ideas, and sometimes even take them for granted: (1) curriculum content and academic achievement, (2) sequencing and readiness, and (3) the importance of transferring learning to new or future situations.

Viewing learning as dependent on curriculum

When teachers speak of learning, they tend to emphasize whatever is taught in schools deliberately, including both the official curriculum and the various behaviors and routines that make classrooms run smoothly. In practice, defining learning in this way often means that teachers equate learning with the major forms of academic achievement—especially language and mathematics—and to a lesser extent musical skill, physical coordination, or social sensitivity (Gardner, 1999, 2006). The imbalance occurs not because the goals of public education make teachers responsible for certain content and activities (like books and reading) and the skills which these activities require (like answering teachers’ questions and writing essays). It does happen not (thankfully!) because teachers are biased, insensitive, or unaware that students often learn a lot outside of school.

A side effect of thinking of learning as related only to curriculum or academics is that classroom social interactions and behaviors become issues for teachers—become things that they need to manage. In particular, having dozens of students in one room makes it more likely that I, as a teacher, think of “learning” as something that either takes concentration (to avoid being distracted by others) or that benefits from collaboration (to take advantage of their presence). In the small space of a classroom, no other viewpoint about social interaction makes sense. Yet in the wider world outside of school, learning often does happen incidentally, “accidentally” and without conscious interference or input from others: I “learn” what a friend’s personality is like, for example, without either of us deliberately trying to make this happen. As teachers, we sometimes see incidental learning in classrooms as well, and often welcome it; but our responsibility for curriculum goals more often focuses our efforts on what students can learn through conscious, deliberate effort. In a classroom, unlike in many other human settings, it is always necessary to ask whether classmates are helping or hindering individual students’ learning.

Focusing learning on changes in classrooms has several other effects. One, for example, is that it can tempt teachers to think that what is taught is equivalent to what is learned—even though most teachers know that doing so is a mistake, and that teaching and learning can be quite different. If I assign a reading to my students about the Russian Revolution, it would be nice to assume not only that they have read the same words, but also learned the same content. But that assumption is not usually the reality. Some students may have read and learned all of what I assigned; others may have read everything but misunderstood the material or remembered only some of it; and still others, unfortunately, may have neither read nor learned much of anything. Chances are that my students would confirm this picture, if asked confidentially. There are ways, of course, to deal helpfully with such diversity of outcomes; for suggestions, see especially Chapter 11 “Planning instruction” and Chapter 12 “Teacher-made assessment strategies”. But whatever instructional strategies I adopt, they cannot include assuming that what I teach is the same as what students understand or retain of what I teach.

Viewing learning as dependent on sequencing and readiness

The distinction between teaching and learning creates a secondary issue for teachers, that of educational readiness . Traditionally the concept referred to students’ preparedness to cope with or profit from the activities and expectations of school. A kindergarten child was “ready” to start school, for example, if he or she was in good health, showed moderately good social skills, could take care of personal physical needs (like eating lunch or going to the bathroom unsupervised), could use a pencil to make simple drawings, and so on. Table 2 shows a similar set of criteria for determining whether a child is “ready” to learn to read (Copple & Bredekamp, 2006). At older ages (such as in high school or university), the term readiness is often replaced by a more specific term, prerequisites. To take a course in physics, for example, a student must first have certain prerequisite experiences, such as studying advanced algebra or calculus. To begin work as a public school teacher, a person must first engage in practice teaching for a period of time (not to mention also studying educational psychology!).

Table 2: Reading readiness in students vs in teachers

|

|

|

| Copple & Bredekamp, 2006. | |

Note that this traditional meaning, of readiness as preparedness, focuses attention on students’ adjustment to school and away from the reverse: the possibility that schools and teachers also have a responsibility for adjusting to students. But the latter idea is in fact a legitimate, second meaning for readiness: If 5-year-old children normally need to play a lot and keep active, then it is fair to say that their kindergarten teacher needs to be “ready” for this behavior by planning for a program that allows a lot of play and physical activity. If she cannot or will not do so (whatever the reason may be), then in a very real sense this failure is not the children’s responsibility. Among older students, the second, teacher-oriented meaning of readiness makes sense as well. If a teacher has a student with a disability (for example, the student is visually impaired), then the teacher has to adjust her approach in appropriate ways—not simply expect a visually impaired child to “sink or swim”. As you might expect, this sense of readiness is very important for special education, so I discuss it further in Chapter 6 “Students with special educational needs”. But the issue of readiness also figures importantly whenever students are diverse (which is most of the time), so it also comes up in Chapter 5 “Student diversity”.

Viewing transfer as a crucial outcome of learning

Still another result of focusing the concept of learning on classrooms is that it raises issues of usefulness or transfer, which is the ability to use knowledge or skill in situations beyond the ones in which they are acquired. Learning to read and learning to solve arithmetic problems, for example, are major goals of the elementary school curriculum because those skills are meant to be used not only inside the classroom, but outside as well. We teachers intend, that is, for reading and arithmetic skills to “transfer”, even though we also do our best to make the skills enjoyable while they are still being learned. In the world inhabited by teachers, even more than in other worlds, making learning fun is certainly a good thing to do, but making learning useful as well as fun is even better. Combining enjoyment and usefulness, in fact, is a “gold standard” of teaching: we generally seek it for students, even though we may not succeed at providing it all of the time.

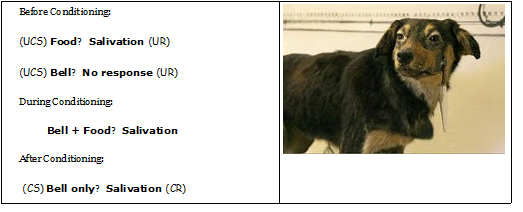

Major theories and models of learning