- The First 6 Months - Tackling the Literature Review

For most PhD students, the first year is dominated by writing a literature review . For anyone yet to meet this particular beast, a literature review is a summary of all the key research completed in your field, highlighting gaps in understanding that future studies need to address. This is commonly completed in your first year to build your knowledge of the subject and identify questions which your research could aim to answer. Your literature review also forms part of your confirmation report, which you need to complete at the end of your first year to be confirmed as a doctoral candidate. This will be a really rewarding document to look back on at the end of the PhD to see how your research has contributed to the field. However, knowing where to start can be daunting so here are my top tips to help.

#1 Decide on your review style early on

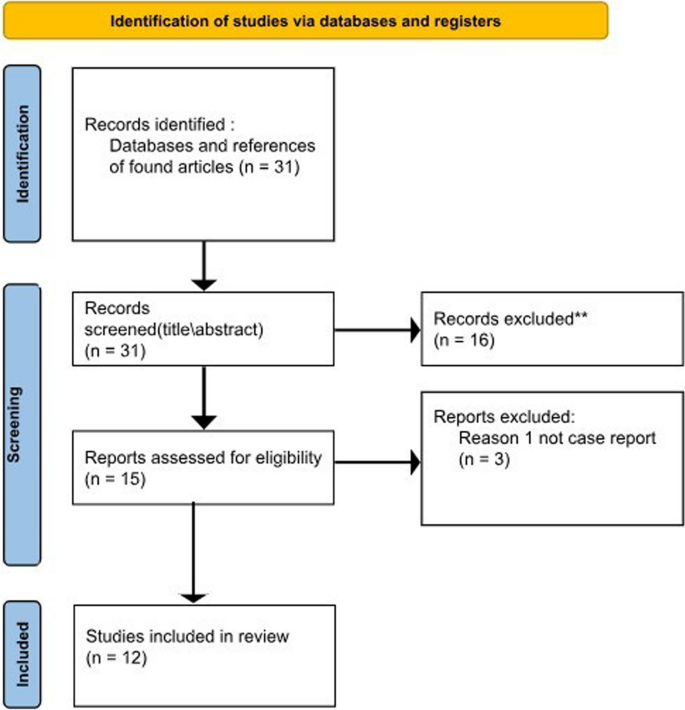

Your literature review can be systematic or narrative. A narrative review is the way most people think to approach a literature review: you start with a few key words and then grow your search organically by following the citations of key papers. You can keep changing your search words to find more articles and can decide which papers you want to use with minimal justification. The alternative is a systematic review. As the name suggests this style has a stricter system with defined search terms and exclusion/inclusion criteria. This helps you find all the possible articles which you then narrow down the ones to review using detailed criteria. Which style of review is appropriate will depend on your topic and research question. Talk to your supervisor about which type of review you are aiming for.

#2 Find an organisation method that works for you

The key challenge with the literature review is managing the sheer volume of papers you read. As I have advised before, write EVERYTHING down. You will never remember exactly what you read or where you found it. A sure sign of a PhD student is that we have a billion tabs open – all papers that we intend to read at some point but will probably never get round to! This means that the icon for each tab is so small that even keeping the article open isn’t a sure-fire way to find it again! Deciding on a notetaking system that works for you is really important; the earlier into your reading journey you do this, the easier it will be. I personally use a spreadsheet with the article name, first author, year, key words (which I can use to filter for relevant paragraphs when writing) and key notes about the paper. This system also means I can check that I haven’t read a paper before (trust me, it happens!!). People record their notes differently - my trusty spreadsheet might not work for you. Find what suits you and then stick to it. It's also important to decide on a reference management system early on so you can add your articles in as your read them and keep an accurate bibliography. This will make it easier when you need to import citations into your literature review and means you can make your reference list automatically through systems like EndNote or Mendeley.

#3 Know when to start writing

Obviously, you can’t start writing straight away – you have to read the literature to be able to review it! However, it’s hard to know when to stop reading and put pen to paper. This is a personal decision, but I started writing as soon as I felt I had a good understanding of a mini topic. I divided my literature review into key sections and then researched and wrote a draft for each in turn. This broke up the tasks into smaller chunks and made it feel more achievable. Starting writing can also show you areas where you’re missing references to support your point. This creates a feedback cycle of more reading and more writing to strength your review.

Start writing whichever section you feel most confident in. This doesn’t have to be the first section. My background is in Biomedical Sciences so I was more confident on those sections than the topics which were newer to me. Writing these paragraphs first helped me build confidence and develop my writing style. Send this first section to your supervisors so they can get a feel for your writing voice early on. The first time you send your work off is really daunting but remember they are there to help and support you, not assess you. Their feedback will help grow your literature review to the standard of your future thesis.

#4 Keep updating and refreshing articles

The nature of literature is that it keeps growing. This means you can’t do one search and assume that 6 months later you still have all the relevant articles. New research is being published every day so make sure to keep checking for any key developments. The library team at your university may be able to help you set up alerts for key words so that you never miss a crucial paper. If there are a few key players in your area, follow them on social media so you’ll see if they publish anything new. Accepting that you will miss papers the first-time round is all part of the process of reviewing and it can be exciting to see how the field has changed in the 6 months since you last checked results.

#5 Trust that you are the right person to write the review

I felt very strange about summarising (and sometimes criticising) the work of established researchers. However, over the course of writing your literature review you will start to better understand the field and be able to critically analyse the work that has gone before you. Imposter syndrome has a huge effect on review authors but trust that you are the right person to write this review and by the end you’ll know enough to summarise the work completed. All PhD students struggle with this feeling so talk to other researchers; there may also be some university provided courses on imposter syndrome to help you see your abilities more clearly.

Doing my literature review in the last six months has increased my confidence when discussing my project with others. Taking the time to do your review well will stand you in better stead when you start collecting research presenting results. Plus, it’s satisfying to see all the progress you’ve made when you look at your 10,000-word document. You can do it!!

Our postgrad newsletter shares courses, funding news, stories and advice

You may also like....

Here's what you need to know about applying for a Masters or PhD at one of the Netherlands' excellent universities, with advice on applications, fees, funding and arrivals.

Applications for many PhD and Masters programmes at German universities are still open – this is what you need to know about studying in Germany this year.

FindAPhD. Copyright 2005-2024 All rights reserved.

Unknown ( change )

Have you got time to answer some quick questions about PhD study?

Select your nearest city

You haven’t completed your profile yet. To get the most out of FindAPhD, finish your profile and receive these benefits:

- Monthly chance to win one of ten £10 Amazon vouchers ; winners will be notified every month.*

- The latest PhD projects delivered straight to your inbox

- Access to our £6,000 scholarship competition

- Weekly newsletter with funding opportunities, research proposal tips and much more

- Early access to our physical and virtual postgraduate study fairs

Or begin browsing FindAPhD.com

or begin browsing FindAPhD.com

*Offer only available for the duration of your active subscription, and subject to change. You MUST claim your prize within 72 hours, if not we will redraw.

Do you want hassle-free information and advice?

Create your FindAPhD account and sign up to our newsletter:

- Find out about funding opportunities and application tips

- Receive weekly advice, student stories and the latest PhD news

- Hear about our upcoming study fairs

- Save your favourite projects, track enquiries and get personalised subject updates

Create your account

Looking to list your PhD opportunities? Log in here .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved June 24, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

A guide for first year PhD students: Expectations, responsibilities, advice

The first year of a PhD can feel like a rollercoaster ride. First-year PhD students are ambitious and want to fulfil expectations. At the same time, they may be unsure of what these expectations and their responsibilities are. This guide aims to provide first-year PhD students with some directions and advice.

The first year as a PhD student: Excitement, ambition, overwhelm

Starting a PhD is exciting. Securing a PhD position is a major life event, and often something that first-year year PhD students have been working towards for a long time.

First-year PhD students want to do well, make progress with their projects and meet their supervisors’ expectations. However, it is not always clear what that means.

Questions like these, and insecurities, often develop early on in a PhD journey.

What to expect as a first-year PhD student

Succeeding in academia has many facets, including your thesis or dissertation, but also learning new skills, and developing relationships with supervisors, colleagues and scholars in your field. All of that takes energy.

Set realistic expectations for yourself in the first year of your PhD. Not everything will work out as planned. Research takes time, and setbacks are inevitable.

First-year PhD students can also expect to read and explore a lot. At times, this involves going down the rabbit hole of academic literature: processing new information, frameworks and perspectives before discarding them again.

Responsibilities of a first-year PhD student

However, frequently a key responsibility of a PhD student is to develop a firm research proposal in the first year, which is often coupled with an extensive literature review.

All in all, a first-year PhD student is responsible to get organised and create a feasible plan for the coming years. The first year is meant to set the foundation for the PhD trajectory .

Unless the PhD programme is followed online, and unless there is a pandemic raging, first-year PhD students are additionally often expected to actively participate in the research group, lab or department in which they are based.

A supervisor’s expectations of a first-year PhD student

While this can certainly happen, I dare to say that this is not the norm.

For instance, PhD supervisors tend to appreciate some levels of regularity and consistency. While it is absolutely normal to have periods where you make more progress (for instance in writing) than in others, it is not good to contact your supervisor every day for a month, and then fall off the earth for half a year.

Lastly, supervisors often expect PhD students to take matters into their own hands. Instead of simply waiting for instruction, this means that first-year PhD students should be in the driver’s seat of their journey. Therefore, it is no surprise that proactiveness is one of the 10 qualities of successful PhD students.

25 things every first year PhD student should do

Thesis/dissertation, academic skills, relationships and networking, health and well-being, master academia, get new content delivered directly to your inbox, deciding between a one- or a two-year master's degree, email signatures for phd students (content, tips and examples), related articles, key quotes to motivate and drive academic success, 10 reasons not to do a master’s degree, 10 signs of a bad phd supervisor, 3 sample recommendation letters for brilliant students.

- What Is a PhD Literature Review?

- Doing a PhD

A literature review is a critical analysis of published academic literature, mainly peer-reviewed papers and books, on a specific topic. This isn’t just a list of published studies but is a document summarising and critically appraising the main work by researchers in the field, the key findings, limitations and gaps identified in the knowledge.

- The aim of a literature review is to critically assess the literature in your chosen field of research and be able to present an overview of the current knowledge gained from previous work.

- By the conclusion of your literature review, you as a researcher should have identified the gaps in knowledge in your field; i.e. the unanswered research questions which your PhD project will help to answer.

- Quality not quantity is the approach to use when writing a literature review for a PhD but as a general rule of thumb, most are between 6,000 and 12,000 words.

What Is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

First, to be clear on what a PhD literature review is NOT: it is not a ‘paper by paper’ summary of what others have done in your field. All you’re doing here is listing out all the papers and book chapters you’ve found with some text joining things together. This is a common mistake made by PhD students early on in their research project. This is a sign of poor academic writing and if it’s not picked up by your supervisor, it’ll definitely be by your examiners.

The biggest issue your examiners will have here is that you won’t have demonstrated an application of critical thinking when examining existing knowledge from previous research. This is an important part of the research process as a PhD student. It’s needed to show where the gaps in knowledge were, and how then you were able to identify the novelty of each research question and subsequent work.

The five main outcomes from carrying out a good literature review should be:

- An understanding of what has been published in your subject area of research,

- An appreciation of the leading research groups and authors in your field and their key contributions to the research topic,

- Knowledge of the key theories in your field,

- Knowledge of the main research areas within your field of interest,

- A clear understanding of the research gap in knowledge that will help to motivate your PhD research questions .

When assessing the academic papers or books that you’ve come across, you must think about the strengths and weaknesses of them; what was novel about their work and what were the limitations? Are different sources of relevant literature coming to similar conclusions and complementing each other, or are you seeing different outcomes on the same topic by different researchers?

When Should I Write My Literature Review?

In the structure of your PhD thesis , your literature review is effectively your first main chapter. It’s at the start of your thesis and should, therefore, be a task you perform at the start of your research. After all, you need to have reviewed the literature to work out how your research can contribute novel findings to your area of research. Sometimes, however, in particular when you apply for a PhD project with a pre-defined research title and research questions, your supervisor may already know where the gaps in knowledge are.

You may be tempted to skip the literature review and dive straight into tackling the set questions (then completing the review at the end before thesis submission) but we strongly advise against this. Whilst your supervisor will be very familiar with the area, you as a doctoral student will not be and so it is essential that you gain this understanding before getting into the research.

How Long Should the Literature Review Be?

As your literature review will be one of your main thesis chapters, it needs to be a substantial body of work. It’s not a good strategy to have a thesis writing process here based on a specific word count, but know that most reviews are typically between 6,000 and 12,000 words. The length will depend on how much relevant material has previously been published in your field.

A point to remember though is that the review needs to be easy to read and avoid being filled with unnecessary information; in your search of selected literature, consider filtering out publications that don’t appear to add anything novel to the discussion – this might be useful in fields with hundreds of papers.

How Do I Write the Literature Review?

Before you start writing your literature review, you need to be clear on the topic you are researching.

1. Evaluating and Selecting the Publications

After completing your literature search and downloading all the papers you find, you may find that you have a lot of papers to read through ! You may find that you have so many papers that it’s unreasonable to read through all of them in their entirety, so you need to find a way to understand what they’re about and decide if they’re important quickly.

A good starting point is to read the abstract of the paper to gauge if it is useful and, as you do so, consider the following questions in your mind:

- What was the overarching aim of the paper?

- What was the methodology used by the authors?

- Was this an experimental study or was this more theoretical in its approach?

- What were the results and what did the authors conclude in their paper?

- How does the data presented in this paper relate to other publications within this field?

- Does it add new knowledge, does it raise more questions or does it confirm what is already known in your field? What is the key concept that the study described?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of this study, and in particular, what are the limitations?

2. Identifying Themes

To put together the structure of your literature review you need to identify the common themes that emerge from the collective papers and books that you have read. Key things to think about are:

- Are there common methodologies different authors have used or have these changed over time?

- Do the research questions change over time or are the key question’s still unanswered?

- Is there general agreement between different research groups in the main results and outcomes, or do different authors provide differing points of view and different conclusions?

- What are the key papers in your field that have had the biggest impact on the research?

- Have different publications identified similar weaknesses or limitations or gaps in the knowledge that still need to be addressed?

Structuring and Writing Your Literature Review

There are several ways in which you can structure a literature review and this may depend on if, for example, your project is a science or non-science based PhD.

One approach may be to tell a story about how your research area has developed over time. You need to be careful here that you don’t just describe the different papers published in chronological order but that you discuss how different studies have motivated subsequent studies, how the knowledge has developed over time in your field, concluding with what is currently known, and what is currently not understood.

Alternatively, you may find from reading your papers that common themes emerge and it may be easier to develop your review around these, i.e. a thematic review. For example, if you are writing up about bridge design, you may structure the review around the themes of regulation, analysis, and sustainability.

As another approach, you might want to talk about the different research methodologies that have been used. You could then compare and contrast the results and ultimate conclusions that have been drawn from each.

As with all your chapters in your thesis, your literature review will be broken up into three key headings, with the basic structure being the introduction, the main body and conclusion. Within the main body, you will use several subheadings to separate out the topics depending on if you’re structuring it by the time period, the methods used or the common themes that have emerged.

The important thing to think about as you write your main body of text is to summarise the key takeaway messages from each research paper and how they come together to give one or more conclusions. Don’t just stop at summarising the papers though, instead continue on to give your analysis and your opinion on how these previous publications fit into the wider research field and where they have an impact. Emphasise the strengths of the studies you have evaluated also be clear on the limitations of previous work how these may have influenced the results and conclusions of the studies.

In your concluding paragraphs focus your discussion on how your critical evaluation of literature has helped you identify unanswered research questions and how you plan to address these in your PhD project. State the research problem you’re going to address and end with the overarching aim and key objectives of your work .

When writing at a graduate level, you have to take a critical approach when reading existing literature in your field to determine if and how it added value to existing knowledge. You may find that a large number of the papers on your reference list have the right academic context but are essentially saying the same thing. As a graduate student, you’ll need to take a methodological approach to work through this existing research to identify what is relevant literature and what is not.

You then need to go one step further to interpret and articulate the current state of what is known, based on existing theories, and where the research gaps are. It is these gaps in the literature that you will address in your own research project.

- Decide on a research area and an associated research question.

- Decide on the extent of your scope and start looking for literature.

- Review and evaluate the literature.

- Plan an outline for your literature review and start writing it.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.9(7); 2013 Jul

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

1 Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE), CNRS, Montpellier, France

2 Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), FRB, Aix-en-Provence, France

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

- interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

- an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

- a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

- keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

- keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

- use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

- define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

- do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

- discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

- trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

- incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

- be thorough,

- use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

- look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

- the major achievements in the reviewed field,

- the main areas of debate, and

- the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Undergraduate courses

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Postgraduate events

- Fees and funding

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Term dates and calendars

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

- Give to Cambridge

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges & departments

- Email & phone search

- Museums & collections

- Current students

- PhD students

- Progression

- Department of Computer Science and Technology

Sign in with Raven

- People overview

- Research staff

- Professional services staff

- Affiliated lecturers

- Overview of Professional Services Staff

- Seminars overview

- Weekly timetable

- Wednesday seminars

- Wednesday seminar recordings ➥

- Wheeler lectures

- Computer Laboratory 75th anniversary ➥

- women@CL 10th anniversary ➥

- Job vacancies ➥

- Library resources ➥

- How to get here

- William Gates Building layout

- Contact information

- Department calendar ➥

- Accelerate Programme for Scientific Discovery overview

- Data Trusts Initiative overview

- Pilot Funding FAQs

- Research Funding FAQs

- Cambridge Ring overview

- Ring Events

- Hall of Fame

- Hall of Fame Awards

- Hall of Fame - Nominations

- The Supporters' Club overview

- Industrial Collaboration

- Annual Recruitment Fair overview

- Graduate Opportunities

- Summer internships

- Technical Talks

- Supporter Events and Competitions

- How to join

- Collaborate with Us

- Cambridge Centre for Carbon Credits (4C)

- Equality and Diversity overview

- Athena SWAN

- E&D Committee

- Support and Development

- Targeted funding

- LGBTQ+@CL overview

- Links and resources

- Queer Library

- women@CL overview

- About Us overview

- Friends of women@CL overview

- Twentieth Anniversary of Women@CL

- Tech Events

- Students' experiences

- Contact overview

- Mailing lists

- Scholarships

- Initiatives

- Dignity Policy

- Outreach overview

- Women in Computer Science Programme

- Google DeepMind Research Ready programme overview

- Accommodation and Pay

- Application

- Eligibility

- Raspberry Pi Tutorials ➥

- Wiseman prize

- Research overview

- Application areas

- Research themes

- Algorithms and Complexity

- Computer Architecture overview

- Creating a new Computer Architecture Research Centre

- Graphics, Vision and Imaging Science

- Human-Centred Computing

- Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

- Mobile Systems, Robotics and Automation

- Natural Language Processing

- Programming Languages, Semantics and Verification

- Systems and Networking

- Research groups overview

- Computer Architecture Group overview

- Student projects

- Energy and Environment Group overview

- Declaration

- Publications

- EEG Research Group

- Past seminars

- Learning and Human Intelligence Group overview

- Quantum Computing Group

- Technical Reports

- Admissions information

- Undergraduate admissions overview

- Open days and events

- Undergraduate course overview overview

- Making your application

- Admissions FAQs

- Super curricular activities

- MPhil in Advanced Computer Science overview

- Applications

- Course structure

- Funding competitions

- Prerequisites

- PhD in Computer Science overview

- Application forms

- Research Proposal

- Funding competitions and grants

- Part-time PhD Degree

- Premium Research Studentship

- Current students overview

- Part IB overview

- Part IB group projects overview

- Important dates

- Design briefs

- Moodle course ➥

- Learning objectives and assessment

- Technical considerations

- After the project

- Part II overview

- Part II projects overview

- Project suggestions

- Project Checker groups

- Project proposal

- Advice on running the project

- Progress report and presentation

- The dissertation

- Supervisor briefing notes

- Project Checker briefing notes

- Past overseer groups ➥

- Part II Supervision sign-up

- Part II Modules

- Part II Supervisions overview

- Continuing to Part III overview

- Part III of the Computer Science Tripos

- Overview overview

- Information for current Masters students overview

- Special topics

- Part III and ACS projects overview

- Submission of project reports

- ACS projects overview

- Guidance for ACS projects

- Part III projects overview

- Guidance for Part III projects

- Preparation

- Registration

- Induction - Masters students

- PhD resources overview

- Deadlines for PhD applications

- Protocol for Graduate Advisers for PhD students

- Guidelines for PhD supervisors

- Induction information overview

- Important Dates

- Who is here to help

- Exemption from University Composition Fees

- Being a research student

- Researcher Development

- Research skills programme

- First Year Report: the PhD Proposal

- Second Year Report: Dissertation Schedule

- Third Year Report: Progress Statement

- Fourth Year: writing up and completion overview

- PhD thesis formatting

- Writing up and word count

- Submitting your dissertation

- Papers and conferences

- Leave to work away, holidays, and intermission

- List of PhD students ➥

- PAT, recycling, and Building Services

- Freshers overview

- Cambridge University Freshers' Events

- Undergraduate teaching information and important dates

- Course material 2023/24 ➥

- Course material 2024/25 ➥

- Exams overview

- Examination dates

- Examination results ➥

- Examiners' reports ➥

- Part III Assessment

- MPhil Assessment

- Past exam papers ➥

- Examinations Guidance 2023-24

- Marking Scheme and Classing Convention

- Guidance on Plagiarism and Academic Misconduct

- Purchase of calculators

- Examinations Data Retention Policy

- Guidance on deadlines and extensions

- Mark Check procedure and Examination Review

- Lecture timetables overview

- Understanding the concise timetable

- Supervisions overview

- Part II supervisions overview ➥

- Part II supervision sign-up ➥

- Supervising in Computer Science

- Supervisor support

- Directors of Studies list

- Academic exchanges

- Advice for visiting students taking Part IB CST

- Summer internship: Optimisation of DNN Accelerators using Bayesian Optimisation

- UROP internships

- Resources for students overview

- Student SSH server

- Online services

- Managed Cluster Service (MCS)

- Microsoft Software for personal use

- Installing Linux

- Part III and MPhil Machines

- Transferable skills

- Course feedback and where to find help overview

- Providing lecture feedback

- Fast feedback hotline

- Staff-Student Consultative Forum

- Breaking the silence ➥

- Student Administration Offices

- Intranet overview

- New starters and visitors

- Forms and templates

- Building management

- Health and safety

- Teaching information

- Research admin

- Miscellaneous

- Fourth Year: writing up and completion

- PhD resources

All candidates for the PhD Degree are admitted on a probationary basis. A student's status with the Student Registry is that he or she will be registered for the CPGS in Computer Science . At the end of the first academic year, a formal assessment of progress is made. In the Department of Computer Science and Technology, this takes the form of a single document of no more than 10,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, bibliography and appendices.

The document is principally a PhD Proposal . That is, a document that demonstrates a clear path from the candidate's current position to a complete PhD thesis at the end of the third year. The document has two purposes: (i) to help the candidate to reflect on and plan their research project and (ii) to allow the Computer Laboratory to assess the student's progress and planned research.

In the document, the candidate should do the following:

- Identify a potential problem or topic to address for the PhD.

- identifying the seminal prior research in the topic area

- the most closely related prior work, and

- their strengths and weaknesses.

The goal is to show the limitations (or lack) of previous work. One method that could be employed to do this is to provide both a taxonomy of prior work and a gap analysis table: a table whose rows are the closest related work, the columns are the desired attributes of the solution, and each table entry is a Yes or a No. This would then clearly show that no prior work meets all the desired attributes.

This section of the document might be expected to form the basis of part of the candidate's final PhD thesis.

Candidates should have already done some preliminary research. This may be early attempts at proofs, a detailed analysis of existing methods, a critique of existing systems, assembly and testing of investigative apparatus, conduct of a pilot experiment, etc. This section of the document may form the basis of a chapter of the final PhD thesis. It is common for the candidate to have produced an academic paper (even if this is a minor paper for a workshop, for example), where they are the main author. The paper does not need to have been published, but the assessors should be able to see that it is of potentially publishable quality. Such a paper can be submitted as an appendix to the document; in this case the material in the paper should not be reproduced in the document, but should be summarised briefly in a self-contained way.

This should indicate, at a high level, the research that might be undertaken in the second and third years of the PhD. It needs to show that there is a viable route to a thesis in two years' time. In particular, it must state the specific research question or questions that are being addressed. If there are more than one question being addressed, it needs to be made clear how they are interconnected and how answering them would result in a coherent thesis story. They need to also be accompanied with a brief discussion of why they are important and interesting questions that are worthy of a Cambridge PhD, and why they are new (the gap analysis table could be used for this). Next, the candidate needs to describe the proposed method of attacking the questions, for example, by listing the major steps to completion through the next two years.

Some candidates find it useful to structure this as a cohesive one-page summary of the proposed thesis, with a tentative title, a paragraph setting the context, and three or four paragraphs describing chunks of the proposed research, each of which could be the basis for an academic paper and each of which could be expected to be a chapter of the final thesis. The chapters should make a cohesive overarching narrative of the thesis, rather than be stand-alone pieces of work.

A paragraph identifying criteria for success is recommended where the candidate explains how they will convince the research community that their approach is successful.

Potential risks are recommended to be identified: what could derail this methodology (technically) and if this happens what is plan B?

- Timeplan: provide a detailed timetable, with explicit milestones for each term in the next two years against which the candidate will measure their progress. This would ideally include technical tasks that are planned to be accomplished during each time chunk.

It is essential that the supervisor(s) agrees that the document may be submitted. The document will be read by two other members of staff (assessors), who will interview the student about the content of the document in a viva. It should therefore give sufficient information that the assessors can satisfy themselves that all is well. It is expected that the interview will take place before the end of the first year.

Submission deadlines (electronic)

- For students admitted in Michaelmas Term, by June 30, 23:59

- For students admitted in Lent Term, October 30, 23:59

- For students admitted in Easter Term, by January 30, 23:59

All submissions should be made electronically via the filer.

Electronic version (in PDF format) should be provided via the PhD report and thesis upload page . This deposits uploaded files on the departmental filer at /auto/anfs/www-uploads/phd = \\filer.cl.cam.ac.uk\webserver\www-uploads\phd.

Students intending to take up research placements during the vacations which begin on, before, or shortly after the submission deadlines must submit their report one month before departure to enable the examination process to be completed before the internship begins . No other extensions will be permitted unless otherwise authorized by the Secretary of the Degree Committee.

Oral examination

The student will be invited to discuss the documents with two assessors appointed by the student's principal supervisor. Neither of the assessors should be the student's principal supervisor though one may be the student's second advisor. Occasionally, the principal supervisor may be invited to clarify elements of the PhD Proposal and to attend the viva as an observer.

Where the initial PhD Proposal document is unsatisfactory, the assessors must ask for a revised submission and arrange a further discussion. Where the PhD Proposal is acceptable, it may still help the student to record suggested modifications in a final version of the Proposal. A copy of the revised document must be submitted to the Secretary of the Degree Committee.

The PhD Proposal document is internal to the Laboratory. However, since it is the basis for formal progress reports including registration for the PhD Degree and those made to funding bodies, assessors should endeavour to arrange a meeting where the documents should be assessed and discussed by the end of the student's first year at the latest. The Secretary of the Degree Committee should be informed of the result by the assessors and by the supervisor on the Postgraduate Feedback and Reporting System as soon as possible thereafter.

The report will be considered by the Degree Committee which will make its recommendations on the registration of the student to the Board of Graduate Studies.

In those cases where the student's progress is wholly inadequate, the supervisor should give them a written warning by 15 September (or the appropriate corresponding date - 15 December or 15 March) that they are in danger of termination, with copy to the Secretary of the Degree Committee.

The word limit is a maximum; it is not a target. Successful PhD Proposal documents can be significantly shorter than the limit. Writing within the word limit is important. It is part of the discipline of producing reports. When submitting reports (and the final PhD thesis), students will be required to sign a Statement of Word Length to confirm that the work does not exceed the limit of length prescribed (above) for the CPGS examination.

Originality

Attention is drawn to the University's guidance concerning plagiarism. The University states that "Plagiarism is defined as submitting as one's own work that which derives in part or in its entirety from the work of others without due acknowledgement. It is both poor scholarship and a breach of academic integrity." The Faculty's guidance concerning plagiarism and good academic practice can be found at https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/exams/plagiarism.html .

Reports may be soft-bound in comb-binding or stapled.

Secretary of the Degree Committee September 2013, updated September 2021, updated March 2022

Department of Computer Science and Technology University of Cambridge William Gates Building 15 JJ Thomson Avenue Cambridge CB3 0FD

Information provided by [email protected]

Privacy policy

Social media

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

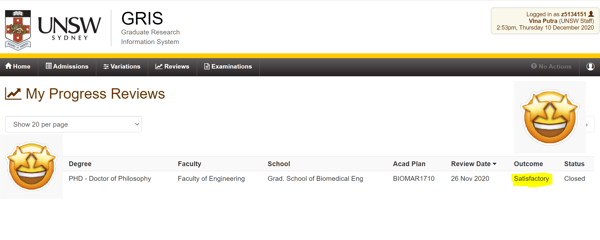

Welcome to the research world! - My first PhD annual progress review

"The week has been chockers!", let me just quote what my supervisor said today, as the last week of November finally came to an end and we embraced the many nerve-racking moments that we went through in the past month and year, as we prepare to wind down for end of year.

From thesis students completion, final exam and finalizing marks for a class, the end of the year has been all about assessment. The most important moment for PhD students who begin their enrolment in the beginning of the year, is the annual progress review (APR) that usually takes place in the end of November. I am one of those PhD students, so the most important thing about this week was I have successfully gained the confirmation!

Yes, the confirmation is the term given to the first year PhD students who have successfully gone through the first 9 months of candidature, including completion of all the mandatory writings and trainings, and these are assessed in the review meeting. The goal of this review meeting is to discuss about candidates' progress and research plans and also serves as the opportunity for candidates and supervisors to raise any issues that might be impacting their research. Before attending APR, students are also required to attend workshops to be informed about what are expected from a candidate in order to receive a satisfactory outcome.

In my university (UNSW), candidates ideally has 1 APR meeting every year for 3-4 years of their candidature. The third one is usually the final meeting that determines timely completion and thesis submission according to the projected date. The outcome of each APR meeting will be decided by the panel whether the student achieved satisfactory, marginal or unsatisfactory progress. An unsatisfactory outcome means that the next review will be held within 3 or 6 months instead of within a year to make sure that the student get all the support and resources they need to complete their thesis.

The APR meeting is organized by the school's postgraduate coordinator (this is what is like in biomedical Engineering, UNSW, Sydney). For each candidate, a panel are assigned which consist of 3 academic staffs that may hold different position (professors or associate professor or lecturer) or have different research field/background. One month before the APR, the school sends a calendar invite and information about the meeting, and forms that the candidate and panel require to complete. In my university, a first year PhD student is required to also complete and submit a bunch of documents to be assessed by the panel include:

- Literature review (average is of 30-50 pages)

- Research proposal (containing a shorter literature review as background, then justification of research, aims, methods, and plans for the next 4 years)

- Milestones (Year 1 milestones and activities done to achieve them, and milestones for Year 2. Average of 4 key milestones is usually enough as it is better to not overestimate your available time and resources)

- Proof documents (e.g. email or screen shots) of completion of mandatory workshops and courses such as research integrity, research data management, data storage, student welcome and orientation

- Proof of completion of mandatory coursework such as writing courses, or research essentials

So, when all the documents are gathered a month prior to the schedule APR meeting, the student must complete a review form through the GRIS ( Graduate Research Information System ) platform. GRIS is where candidates information and progresses are managed. The forms that candidates need to complete ask about students research aim, achievement, weekly work hours, meeting and support from supervisor, and any issues that need to be resolved. The forms then get forwarded to the supervisor where they fill out similar information about the candidate. The whole form is completed by the panel on the day of APR with the outcome achieved by the candidate.

So, the way first APR meeting works in my school (Biomedical Engineering) follows this format:

- 5 minutes welcome and introduction - where the chair introduces everyone in the panel and supervisory team

- 15 minutes presentation by the candidate - this is the opportunity for the candidate to really report about research progress, future plans and explaining mostly results achieved. For a first year candidate, it is important to have a strong, SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-based) milestones, that become the key performance indicator to be assessed in the following year. Important TIP: This is the most important aspect being assessed a a first year candidate, make sure that you are clear with your aims!

- 5-10 minutes discussion about research - this is where the panel asks about research background, data and the statistics, some science and justification for experiments. In this part, the candidate really wants to show in depth understanding about the research, that should reflect the wealth of knowledge one writes in their literature review.

- 5 - 10 minutes discussion between panel and the candidate alone - this is the opportunity to raise issues or ask for help outside the supervisory team

- 5 - 10 minutes discussion between panel and the supervisors alone -this is the opportunity for supervisor to report about the candidate

Since COVID-19 has forced all the review meetings to happen virtually (video conference), I had the privilege to attend my APR meeting at home and with a side note for presentation shown in my second monitor 😅. The meeting went very smoothly and the only hurdle was panel have to manage people leaving and joining back to the call during the individual discussion. And I soon got notified of my satisfactory outcome and the panel report!

Anyway, what is the progress review meeting like in your university or school or faculty? And how are your experience in going through this process? I am very curious to hear about your experience in going through PhD review meeting and the differences. Share in the comment section below!

Research: Expectation vs. Reality

My first in person conference of 2020, similar blog posts.

My 4 Day Cruise Experience

My 4-Day Trip to Istanbul

Get a head start in the first year of your PhD

Even a marathon begins with first steps, and so it makes sense to master motivation, set healthy habits and get writing early to reap the reward of a polished dissertation at the end of the PhD journey, writes Andreï Kostryka

Andreï V. Kostyrka

Created in partnership with

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} RIP assessment?

Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn, how to do self-promotion without the cringe factor, a diy guide to starting your own journal, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools.

The first year of a PhD programme can be overwhelming. The success of a dissertation in many fields depends on the polish, iterations and revisions the research has undergone. So, what you do, what habits and routines you set up in the first year, will make a difference to the result at the end.