Work-life balance -a systematic review

Vilakshan - XIMB Journal of Management

ISSN : 0973-1954

Article publication date: 15 December 2021

Issue publication date: 31 July 2023

This study aims to systematically review the existing literature and develop an understanding of work-life balance (WLB) and its relationship with other forms of work-related behavior and unearth research gaps to recommend future research possibilities and priorities.

Design/methodology/approach

The current study attempts to make a detailed survey of the research work done by the pioneers in the domain WLB and its related aspects. A total of 99 research work has been included in this systematic review. The research works have been classified based on the year of publication, geographical distribution, the methodology used and the sector. The various concepts and components that have made significant contributions, factors that influence WLB, importance and implications are discussed.

The paper points to the research gaps and scope for future research in the area of WLB.

Originality/value

The current study uncovered the research gaps regarding the systematic review and classifications based on demography, year of publication, the research method used and sector being studied.

- Work-life balance

- Flexibility

- Individual’s ability to balance work-life

- Support system

- WLB policy utilization

- Societal culture

S., T. and S.N., G. (2023), "Work-life balance -a systematic review", Vilakshan - XIMB Journal of Management , Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 258-276. https://doi.org/10.1108/XJM-10-2020-0186

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Thilagavathy S. and Geetha S.N.

Published in Vilakshan – XIMB Journal of Management . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence maybe seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

In this technological era, work is becoming demanding with changing nature of work and working patterns (Thilagavathy and Geetha, 2020 ). The proactive, aggressive and demanding nature of business with the intention of reaching the top requires active involvement and comprehensive devotion from the employees, thereby compromising their work-life balance (WLB) (Turanlıgil and Farooq, 2019 ). Research concerning the work-life interface has exploded over the past five decades because of the changing trends in the nature of gender roles, families, work and careers (Powell et al. , 2019 ). Researchers in this domain has published many literature reviews with regard to WLB. It is argued that the study of WLB remains snowed under by a lack of conceptual clarity (Perrigino et al. , 2018 ). Thus, research and theory only partially view the employees’ work-life needs and experiences.

How WLB is conceptualized in the past?

What are the factors that significantly influenced WLB?

In which geographical areas were the WLB studies undertaken?

Which sectors remain unstudied or understudied with regard to WLB?

Methodology

We systematically conducted the literature review with the following five steps, as shown in Figure 1 . The first step was to review the abstracts from the database like EBSCO, Science Direct, Proquest and JSTOR. The articles from publishers like ELSEVIER, Emerald insight, Springer, Taylor and Francis and Sage were considered. The literature survey was conducted using the search terms WLB, balancing work and family responsibility and domains of work and life between the period 1990 to 2019. This search process led to the identification of 1,230 relevant papers. Inclusion criteria: The scholarly articles concerning WLB published in the English language in journals listed in Scopus, web of science or Australian business deans council (ABDC) were included in this review. Exclusion criteria: The scholarly articles concerning WLB published in languages other than English were not taken into consideration. Similarly, unpublished papers and articles published in journals not listed in Scopus, web of science or ABDC were excluded.

In the second step, we identified the duplicates and removed them. Thus, the total number of papers got reduced to 960. Following this, many papers relating to work-life spillover and work-life conflict were removed, resulting in further reduction of the papers to 416. Subsequently, in the third step, the papers were further filtered based on the language. The paper in the English language from journals listed in Scopus, web of science or ABDC were only considered. This search process resulted in the reduction of related papers to 93. The fourth step in the search process was further supplemented with the organic search for the related articles, leading to 99 papers illustrated in Appendix Table 1 . In the fifth step, an Excel sheet was created to review the paper under different headings and the results are as follows.

Literature review

Evolution and conceptualization of work-life balance.

WLB concern was raised earlier by the working mothers of the 1960s and 1970s in the UK. Later the issue was given due consideration by the US Government during the mid of 1980. During the 1990s WLB gained adequate recognition as the issue of human resource management in other parts of the world (Bird, 2006 ). The scholarly works concerning WLB have increased, mainly because of the increasing strength of the women workforce, technological innovations, cultural shifts in attitudes toward the relationship between the work and the family and the diversity of family structures (Greenhaus and Kossek, 2014 ). The research works on WLB include several theoretical work-family models. Though the research on WLB has expanded to a greater extend, there are considerable gaps in our knowledge concerning work-family issues (Powell et al. , 2019 ).

Moreover, in studies where WLB and related aspects are explored, researchers have used different operational definitions and measurements for the construct. Kalliath and Brough (2008) have defined WLB as “The individual’s perception that work and non-work activities are compatible and promote growth in accordance with an individual’s current life priorities.” WLB is “a self-defined, self-determined state of well being that a person can reach, or can set as a goal, that allows them to manage effectively multiple responsibilities at work, at home and in their community; it supports physical, emotional, family, and community health, and does so without grief, stress or negative impact” (Canadian Department of Labor, as cited in Waters and Bardoel, 2006 ).

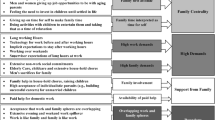

Figure 2 depicts the flowchart of the framework for the literature survey. It clearly shows the factors that have been surveyed in this research article.

Individual factors

The individual factors of WLB include demographic variables, personal demands, family demands, family support and individual ability.

Work-life balance and demography.

WLB has significant variations with demographic variables (Waters and Bardoel, 2006 ). A significant difference was found between age (Powell et al. , 2019 ), gender (Thilagavathy and Geetha, 2020 ) and marital status (Powell et al. , 2019 ) regarding WLB. There is a significant rise in women’s participation in the workforce (Jenkins and Harvey, 2019 ). WLB issues are higher for dual-career couples (Crawford et al. , 2019 ).

Many studies were conducted on WLB with reference to sectors like information technology (IT), information technology enabled services, Banking, Teaching, Academics and Women Employment. A few WLB studies are conducted among services sector employees, hotel and catering services, nurses, doctors, middle-level managers and entrepreneurs. Only very scarce research has been found concerning police, defense, chief executive officers, researchers, lawyers, journalists and road transport.

Work-life balance and personal demands.

High work pressure and high family demand lead to poor physical, psychological and emotional well-being (Jensen and Knudsen, 2017 ), causing concern to employers as this leads to reduced productivity and increased absenteeism (Jackson and Fransman, 2018 ).

Work-life balance and family demands.

An employee spends most of the time commuting (Denstadli et al. , 2017 ) or meeting their work and family responsibilities. Dual career couple in the nuclear family finds it difficult to balance work and life without domestic help (Dumas and Perry-Smith, 2018 ; Srinivasan and Sulur Nachimuthu, 2021 ). Difficulty in a joint family is elderly care (Powell et al. , 2019 ). Thus, family demands negatively predict WLB (Haar et al. , 2019 ).

Work-life balance and family support.

Spouse support enables better WLB (Dumas and Perry-Smith, 2018 ). Family support positively impacted WLB, especially for dual-career couples, with dependent responsibilities (Groysberg and Abrahams, 2014 ).

Work-life balance and individual’s ability.

Though the organizations implement many WLB policies, employees still face the problems of WLB (Dave and Purohit, 2016 ). Employees achieve better well-being through individual coping strategies (Zheng et al. , 2016 ). Individual resources such as stress coping strategy, mindfulness emotional intelligence positively predicted WLB (Kiburz et al. , 2017 ). This indicates the imperative need to improve the individual’s ability to manage work and life.

Organizational factor

Organizational factors are those relating to organization design in terms of framing policies, rules and regulations for administering employees and dealing with their various activities regarding WLB ( Kar and Misra, 2013 ). In this review, organizational factors and their impact on the WLB of the employee have been dealt with in detail.

Work-life balance and organizational work-life policies.

The organization provides a variety of WLB policies (Jenkins and Harvey, 2019 ). Employee-friendly policies positively influenced WLB ( Berg et al. , 2003 ). Further, only a few IT industries provided Flexi timing, work from home and crèches facilities (Downes and Koekemoer, 2012 ). According to Galea et al. (2014) , industry-specific nuance exists.

Work-life balance and organizational demands.

Organizations expect employees to multi-task, causing role overload (Bacharach et al. , 1991 ). The increasing intensity of work and tight deadlines negatively influenced WLB (Allan et al. , 1999 ). The shorter time boundaries make it challenging to balance professional and family life (Jenkins and Harvey, 2019 ). Job demands negatively predicted WLB (Haar et al. , 2019 ).

Work-life balance and working hours.

Work does vacuum up a greater portion of the personal hours (Haar et al. , 2019 ). This causes some important aspects of their lives to be depleted, undernourished or ignored (Hughes et al. , 2018 ). Thus, employees find less time for “quality” family life (Jenkins and Harvey, 2019 ).

Work-life balance and productivity.

Organizational productivity is enhanced by the synergies of work-family practices and work-team design (Johari et al. , 2018 ). Enhanced WLB leads to increased employee productivity (Jackson and Fransman, 2018 ).

Work-life balance and burnout.

WLB is significantly influenced by work exhaustion (burnout). Negative psychological experience arising from job stress is defined as burnout (Ratlif, 1988). Increased work and non-work demands contribute to occupational burnout and, in turn, negatively predict WLB and employee well-being (Jones et al. , 2019 ).

Work-life balance and support system.

Support from Colleagues, supervisors and the head of institutions positively predicted WLB (Ehrhardt and Ragins, 2019 ; Yadav and Sharma, 2021 ). Family-supportive organization policy positively influenced WLB (Haar and Roche, 2010 ).

Work-life balance and employee perception.

The employee’s perception regarding their job, work environment, supervision and organization positively influenced WLB (Fontinha et al. , 2019 ). Employees’ awareness concerning the existence of WLB policies is necessary to appreciate it (Matthews et al. , 2014). The employee’s perception of the need for WLB policies differs with respect to their background (Kiburz et al. , 2017 ).

Work-life balance and job autonomy.

Job autonomy is expressed as the extent of freedom the employee has in their work and working pattern ( Bailey, 1993 ). According to Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) , autonomy and flexibility enable employees to balance competing demands of work-life. Job autonomy will enhance WLB (Johari et al. , 2018 ).

Work-life balance and job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction is the driving force for task accomplishment and employees’ intention to stay (Brough et al. , 2014 ). Employees’ positive perception concerning their job enhances job satisfaction (Singh et al. , 2020 ; Yadav and Sharma, 2021 ). WLB and job satisfaction are positively correlated (Jackson and Fransman, 2018 ).

Work-life balance and organizational commitment.

Alvesson (2002) describes organizational commitment as a mutual and fair social exchange. WLB positively predicted organizational commitment (Emre and De Spiegeleare, 2019 ). Work-life policies offered by an organization lead to increased loyalty and commitment (Callan, 2008 ).

Work-life balance and work-life balance policy utilization.

The utilization of WLB policies (Adame-Sánchez et al. , 2018 ) helps meet job and family demands. Despite the availability of WLB policies, their actual adoption is rather small (Waters and Bardoel, 2006 ) and often lag behind implementation (Adame-Sánchez et al. , 2018 ).

Work-life balance and organizational culture.

Employees perceive WLB policy utilization may badly reflect their performance appraisal and promotion (Bourdeau et al. , 2019 ). Hence, seldom use the WLB policies (Dave and Purohit, 2016 ). The perception of the organization culture as isolated, unfriendly and unaccommodating (Fontinha et al. , 2017 ); a lack of supervisor and manager support and a lack of communication and education about WLB strategies (Jenkins and Harvey, 2019 ). This leads to counterproductive work behavior and work-family backlash (Alexandra, 2014 ). As a result, growing evidence suggests a dark side to WLB policies, but these findings remain scattered and unorganized (Perrigino et al. , 2018 ). Organizational culture significantly affects WLB policy utilization (Callan, 2008 ; Dave and Purohit, 2016 ).

Societal factors

Societal changes that have taken place globally and locally have impacted the individual’s lifestyle. In this modern techno world, a diversified workforce resulting from demographic shifts and communication technology results in blurring of boundaries between work and personal life (Kalliath and Brough, 2008 ).

Work-life balance and societal demands.

Being members of society, mandates employee’s participation in social events. But in the current scenario, this is witnessing a downward trend. The employee often comes across issues of inability to meet the expectation of friends, relatives and society because of increased work pressure. Societal demands significantly predicted WLB (Mushfiqur et al. , 2018 ).

Work-life balance and societal culture.

Societal culture has a strong influence on WLB policy utilization and work and non-work self-efficacy. Specifically, collectivism, power distance and gendered norms had a strong and consistent impact on WLB Policy utilization by employees (Brown et al. , 2019 ). Women’s aspiration to achieve WLB is frequently frustrated by patriarchal norms deep-rooted in the culture (Mushfiqur et al. , 2018 ).

Work-life balance and societal support.

WLB was significantly predicted by support from neighbors, friends and community members (Mushfiqur et al. , 2018 ). Sometimes employees need friend’s viewpoints to get a new perspective on a problem or make a tough decision (Dhanya and Kinslin, 2016 ). Community support is an imperative indicator of WLB ( Phillips et al. , 2016 ).

Analyzes and results

Article distribution based on year of publication.

The WLB studies included for this review were between the periods of 1990–2019. Only a few studies were published in the initial period. A maximum of 44 papers was published during 2016–2019. Out of which, 17 studies were published during the year 2019. In the years 2018, 2017 and 2016 a total of 12, 7 and 8 studies were published, respectively. The details of the article distribution over the years illustrate a rising trend, as shown in Figure 3 .

Geographical distribution

Papers considered for this review were taken globally, including the research works from 26 countries. American and European countries contributed to a maximum of 60% of the publications regarding WLB research. Figure 4 illustrates the contribution of different countries toward the WLB research.

Basic classification

The review included 99 indexed research work contributed by more than 70 authors published in 69 journals. The contribution worth mentioning was from authors like Allen T.D, Biron M, Greenhaus J. H, Haar J.M, Jensen M.T, Kalliath T and Mc Carthy A. The basic categorization revealed that the geographical distribution considered for this review was from 26 different countries, as shown in Figure 4 . The research was conducted in (but not limited to) countries like Africa, Australia, Canada, China, India, Israel, The Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Pakistan, Singapore, Sweden, Turkey, the USA and the UK. American and European countries together contributed to the maximum of 60% of publications. Further, the categorization uncovered that 7 out of the 99 journals contributed to 30% of the WLB papers considered for this review, clearly illustrated in Table 1 .

Methodology-based categorization of papers

The basic information like research methods, sources of data, the proportion of papers using specific methodologies were considered for methodology-based categorization. The categorization revealed that 27 out of 99 papers reviewed were conceptual and the remaining 72 papers were empirical. The empirical papers used descriptive, exploratory, explanatory or experimental research designs. Further, categorization based on the data collection method revealed that 69 papers used the primary data collection method. Additionally, classification uncovered that 57 papers used the quantitative method, whereas 11 papers used the qualitative approach and four used the mixed method. The most prominent primary method used for data collection was the questionnaire method with 58 papers, while the remaining 20 papers used interview (10), case study (5), experimental studies (3), daily dairy (1) or panel discussion (1).

Sector-based categorization of papers

The sector-based categorization of papers revealed that 41.6% (30 papers) of research work was carried out in service sectors. This is followed by 40.2% (29 papers) research in the general public. While one paper was found in the manufacturing sector, the remaining nine papers focused on managers, women, the defense sector, police and the public sector, the details of which are showcased in Table 2 .

Research gap

Individual factor.

The literature survey results demonstrated that the impact of employee education and experience on their WLB had not been examined.

The literature survey has uncovered that the relationship between income and WLB has not been explored.

The influence of domestic help on WLB has not been investigated.

Much of the research work has been carried out in developed countries like the US, UK, European countries and Australia. In contrast, very scarce research works have been found in developing countries and underdeveloped countries.

Not much work has been done in WLB regarding service sectors like fire-fighters, transport services like drivers, railway employees, pilots, air hostesses, power supply department and unorganized sectors.

A review of the relevant literature uncovered that studies concerning the individual’s ability to balance work and life are limited. The individual’s ability, along with WLB policies, considerably improved WLB. Individual strategies are the important ones that need investigation rather than workplace practices.

Kibur z et al . (2017) addressed the ongoing need for experimental, intervention-based design in work-family research. There are so far very scares experimental studies conducted with regard to WLB.

Organizational factor.

A very few studies explored the impact of the WLB policies after the implementation.

Studies concerning the organizational culture, psychological climate and WLB policy utilizations require investigation.

Organizational climates influence on the various factors that predict WLB needs exploration.

Societal factor.

The impact of the societal factors on WLB is not explored much.

Similarly, the influence of societal culture (societal beliefs, societal norms and values systems) on WLB is not investigated.

Discussion and conclusion

The current research work aspires to conduct a systematic review to unearth the research gaps, and propose direction for future studies. For this purpose, literature with regard to WLB was systematically surveyed from 1990 to 2019. This led to identifying 99 scientific research papers from index journals listed in Scopus, the web of science or the ABDC list. Only papers in the English language were considered. The review section elaborated on the evolution and conceptualization of WLB. Moreover, the literature review discussed in detail the relationship between WLB and other related variables. Further, the research works were classified based on the fundamental information revealed that a maximum of 44 papers was published during the year 2016–2019. The geographical distribution revealed that a maximum of research publications concerning WLB was from American and European countries. Further, the basic classification revealed that 7 out of the 69 journals contributed to 30% of the WLB papers considered for this review. The methodology-based classification unearthed the fact that 73% of the papers were empirical studies. Additionally, the categorization uncovered that 79% ( n = 57) of papers used quantitative methods dominated by survey method of data collection. Sector-based categorization made known the fact that a maximum of 41.6% of research work was carried out in the service sector. The research gaps were uncovered based on the systematic literature review and classifications and proposed future research directions.

Limitations

We acknowledge that there is a possibility of missing out a few papers unintentionally, which may not be included in this review. Further, papers in the English language were only considered. Thus, the papers in other languages were not included in this systematic review which is one of the limitations of this research work.

Implications

The discussion reveals the importance and essentiality of the individual’s ability to balance work and life. Consequently, the researchers have proposed future research directions exploring the relationship between the variables. WLB is an important area of research; thus, the proposed research directions are of importance to academicians. The review’s finding demonstrates that there are very scarce studies on the individual’s ability to balance work and life. This leaves a lot of scopes for researchers to do continuous investigation in this area. Hence, it is essential to conduct more research on developing individuals’ ability to balance work and life. There are a few experimental studies conducted so far in WLB. Future experimental studies can be undertaken to enhance the individual’s ability to balance work and life.

Flow chart of the steps in systematic review process

Framework for the literature review

Distribution of papers based on year of publication

Geographical distribution of papers across countries

Journals details

Table 1 List of papers included in the review

Adame-Sánchez , C. , Caplliure , E.M. and Miquel-Romero , M.J. ( 2018 ), “ Paving the way for competition: drivers for work-life balance policy implementation ”, Review of Managerial Science , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 519 - 533 , doi: 10.1007/s11846-017-0271-y .

Ahuja , M. and Thatcher , J. ( 2005 ), “ Moving beyond intentions and towards the theory of trying: effects of work environment and gender on post-adoption information technology use ”, MIS Quarterly , Vol. 29 No. 3 , pp. 427 - 459 .

Allan , C. , O'Donnell , M. and Peetz , D. ( 1999 ), “ More tasks, less secure, working harder: three dimensions of labour utilization ”, Journal of Industrial Relations , Vol. 41 No. 4 , pp. 519 - 535 , doi: 10.1177/002218569904100403 .

Alvesson ( 2002 ), Understanding Organizational Culture , Sage Publications , London . 10.4135/9781446280072

Bacharach , S.B. , Bamberger , R. and Conely , S. ( 1991 ), “ Work-home conflict among nurses and engineers: mediating the impact of stress on burnout and satisfaction at work ”, Journal of Organizational Behavior , Vol. 12 No. 1 , pp. 39 - 63 , doi: 10.1002/job.4030120104 .

Bailey , T.R. ( 1993 ), “ Discretionary effort and the organization of work: employee participation and work reform since Hawthorne ”, Teachers College and Conservation of Human Resources , Columbia University .

Bardoel , E.A. ( 2006 ), “ Work-life balance and human resource development ”, Holland , P. and De Cieri , H. (Eds), Contemporary Issues in Human Resource Development: An Australian Perspective , Pearson Education , Frenchs Forest, NSW , pp. 237 - 259 .

Berg , P. , Kalleberg , A.L. and Appelbaum , E. ( 2003 ), “ Balancing work and family: the role of high - commitment environments ”, Industrial Relations , Vol. 42 No. 2 , pp. 168 - 188 , doi: 10.1111/1468-232X.00286 .

Bird , J. ( 2006 ), “ Work-life balance: doing it right and avoiding the pitfalls ”, Employment Relations Today , Vol. 33 No. 3 , pp. 21 - 30 , doi: 10.1002/ert.20114 .

Bourdeau , S. , Ollier-Malaterre , A. and Houlfort , N. ( 2019 ), “ Not all work-life policies are created equal: career consequences of using enabling versus enclosing work-life policies ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 172 - 193 , doi: 10.5465/amr.2016.0429 .

Brough , P. , Timm , C. , Driscoll , M.P.O. , Kalliath , T. , Siu , O.L. , Sit , C. and Lo , D. ( 2014 ), “ Work-life balance: a longitudinal evaluation of a new measure across Australia and New Zealand workers ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 25 No. 19 , pp. 2724 - 2744 , doi: 10.1080/09585192.2014.899262 .

Callan , S.J. ( 2008 ), “ Cultural revitalization: the importance of acknowledging the values of an organization's ‘golden era’ when promoting work-life balance ”, Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 78 - 97 , doi: 10.1108/17465640810870409 .

Crawford , W.S. , Thompson , M.J. and Ashforth , B.E. ( 2019 ), “ Work-life events theory: making sense of shock events in dual-earner couples ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 194 - 212 , doi: 10.5465/amr.2016.0432 .

Dave , J. and Purohit , H. ( 2016 ), “ Work-life balance and perception: a conceptual framework ”, The Clarion- International Multidisciplinary Journal , Vol. 5 No. 1 , pp. 98 - 104 .

Denstadli , J.M. , Julsrud , T.E. and Christiansen , P. ( 2017 ), “ Urban commuting – a threat to the work-family balance? ”, Journal of Transport Geography , Vol. 61 , pp. 87 - 94 , doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.04.011 .

Downes , C. and Koekemoer , E. ( 2012 ), “ Work-life balance policies: the use of flexitime ”, Journal of Psychology in Africa , Vol. 22 No. 2 , pp. 201 - 208 , doi: 10.1080/14330237.2012.10820518 .

Dumas , T.L. and Perry-Smith , J.E. ( 2018 ), “ The paradox of family structure and plans after work: why single childless employees may be the least absorbed at work ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 61 No. 4 , pp. 1231 - 1252 , doi: 10.5465/amj.2016.0086 .

Ehrhardt , K. and Ragins , B.R. ( 2019 ), “ Relational attachment at work: a complimentary fit perspective on the role of relationships in organizational life ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 62 No. 1 , pp. 248 - 282 , doi: 10.5465/amj.2016.0245 .

Emre , O. and De Spiegeleare , S. ( 2019 ), “ The role of work-life balance and autonomy in the relationship between commuting, employee commitment, and well-being ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 32 No. 11 , pp. 1 - 25 , doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1583270 .

Fontinha , R. , Easton , S. and Van Laar , D. ( 2017 ), “ Overtime and quality of working life in academics and non-academics: the role of perceived work-life balance ”, International Journal of Stress Management , ( in Press ).

Fontinha , R. , Easton , S. and Van Laar , D. ( 2019 ), “ Overtime and quality of working life in academics and non-academics: the role of perceived work-life balance ”, International Journal of Stress Management , Vol. 26 No. 2 , pp. 173 , doi: 10.1037/str0000067 .

Galea , C. , Houkes , I. and Rijk , A.D. ( 2014 ), “ An insider’s point of view: how a system of flexible working hours helps employees to strike a proper balance between work and personal life ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 25 No. 8 , pp. 1090 - 1111 , doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.816862 .

Greenhaus , J.H. and Kossek , E.E. ( 2014 ), “ The contemporary career: a work–home perspective ”, Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior , Vol. 1 No. 1 , pp. 361 - 388 , doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091324 .

Groysberg , B. and Abrahams , R. ( 2014 ), “ Manage your work, manage your life ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 92 No. 3 , pp. 58 - 66 , available at: https://hbr.org/2014/03/manage-your-work-manage-your-life

Haar , J.M. and Roche , M. ( 2010 ), “ Family-supportive organization perceptions and employee outcomes: the mediating effects of life satisfaction ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 21 No. 7 , pp. 999 - 1014 , doi: 10.1080/09585191003783462 .

Haar , J.M. , Sune , A. , Russo , M. and Ollier-Malaterre , A. ( 2019 ), “ A cross-national study on the antecedents of work-life balance from the fit and balance perspective ”, Social Indicators Research , Vol. 142 No. 1 , pp. 261 - 282 , doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-1875-6 .

Hughes , R. , Kinder , A. and Cooper , C.L. ( 2018 ), “ Work-life balance ”, The Wellbeing Workout , pp. 249 - 253 , doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-92552-3_42 .

Jackson , L.T. and Fransman , E.I. ( 2018 ), “ Flexi work, financial well-being, work-life balance and their effects on subjective experiences of productivity and job satisfaction of females in an institution of higher learning ”, South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences , Vol. 21 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 13 , doi: 10.4102/sajems.v21i1.1487 .

Jenkins , K. and Harvey , S.B. ( 2019 ), “ Australian experiences ”, Mental Health in the Workplace , pp. 49 - 66 . Springer , Cham .

Jensen , M.T. and Knudsen , K. ( 2017 ), “ A two-wave cross-lagged study of business travel, work-family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and psychological health complaints ”, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 26 No. 1 , pp. 30 - 41 , doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2016.1197206 .

Johari , J. , Yean Tan , F. and TjikZulkarnain , Z.I. ( 2018 ), “ Autonomy, workload, work-life balance, and job performance among teachers ”, International Journal of Educational Management , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 107 - 120 , doi: 10.1108/IJEM-10-2016-0226 .

Jones , R. , Cleveland , M. and Uther , M. ( 2019 ), “ State and trait neural correlates of the balance between work-non work roles ”, Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging , Vol. 287 , pp. 19 - 30 , doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2019.03.009 .

Kalliath , T. and Brough , P. ( 2008 ), “ Work-life balance: a review of the meaning of the balance construct ”, Journal of Management & Organization , Vol. 14 No. 3 , pp. 323 - 327 , doi: 10.1017/S1833367200003308 .

Kar , S. and Misra , K.C. ( 2013 ), “ Nexus between work life balance practices and employee retention-the mediating effect of a supportive culture ”, Asian Social Science , Vol. 9 No. 11 , p. 63 , doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2019.03.008 , doi: 10.5539/ass.v9n11p63 .

Kiburz , K.M. , Allen , T.D. and French , K.A. ( 2017 ), “ Work-family conflict and mindfulness: investigating the effectiveness of a brief training intervention ”, Journal of Organizational Behavior , Vol. 38 No. 7 , pp. 1016 - 1037 , doi: 10.1002/job.2181 .

Mushfiqur , R. , Mordi , C. , Oruh , E.S. , Nwagbara , U. , Mordi , T. and Turner , I.M. ( 2018 ), “ The impacts of work-life balance (WLB) challenges on social sustainability: the experience of nigerian female medical doctors ”, Employee Relations , Vol. 40 No. 5 , pp. 868 - 888 , doi: 10.1108/ER-06-2017-0131 .

Perrigino , M.B. , Dunford , B.B. and Wilson , K.S. ( 2018 ), “ Work-family backlash: the ‘dark side’ of work-life balance (WLB) policies ”, Academy of Management Annals , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 600 - 630 , doi: 10.5465/annals.2016.0077 .

Phillips , J. , Hustedde , C. , Bjorkman , S. , Prasad , R. , Sola , O. , Wendling , A. and Paladine , H. ( 2016 ), “ Rural women family physicians: strategies for successful work-life balance ”, The Annals of Family Medicine , Vol. 14 No. 3 , pp. 244 - 251 .

Powell , G.N. , Greenhaus , J.H. , Allen , T.D. and Johnson , R.E. ( 2019 ), “ Introduction to special topic forum: advancing and expanding work-life theory from multiple perspectives ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 54 - 71 , doi: 10.5465/amr.2018.0310 .

Ratliff , N. ( 1988 ), “ Stress and burnout in the helping professions ”, Social Casework , Vol. 69 No. 1 , pp. 147 - 154 .

Singh , S. , Singh , S.K. and Srivastava , S. ( 2020 ), “ Relational exploration of the effect of the work-related scheme on job satisfaction ”, Vilakshan – XIMB Journal of Management , Vol. 17 Nos 1/2 , pp. 111 - 128 , doi: 10.1108/XJM-07-2020-0019 .

Srinivasan , T. and Sulur Nachimuthu , G. ( 2021 ), “ COVID-19 impact on employee flourishing: parental stress as mediator ”, Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Advance Online Publication , doi: 10.1037/tra0001037 .

Thilagavathy , S. and Geetha , S.N. ( 2020 ), “ A morphological analyses of the literature on employee work-life balance ”, Current Psychology , pp. 1 - 26 , doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00968-x .

Turanlıgil , F.G. and Farooq , M. ( 2019 ), “ Work-Life balance in tourism industry ”, in Contemporary Human Resources Management in the Tourism Industry , pp. 237 - 274 , IGI Global .

Waters , M.A. and Bardoel , E.A. ( 2006 ), “ Work-family policies in the context of higher education: useful or symbolic? ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 67 - 82 , doi: 10.1177/1038411106061510 .

Yadav , V. and Sharma , H. ( 2021 ), “ Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, and job satisfaction: mediating effect of work-family conflict ”, Vilakshan - XIMB Journal of Management , doi: 10.1108/XJM-02-2021-0050 .

Zheng , C. , Kashi , K. , Fan , D. , Molineux , J. and Ee , M.S. ( 2016 ), “ Impact of individual coping strategies and organizational work-life balance programmes on australian employee well-being ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 27 No. 5 , pp. 501 - 526 , doi: 10.1080/09585192.2015.1020447 .

Further reading

Allen , T.D. ( 2012 ), “ The work and family interface ”, in Kozlowski , S.W.J. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Psychology , Vol. 2 , Oxford University Press , New York, NY , pp. 1163 - 1198 .

Bell , A.S. , Rajendran , D. and Theiler , S. ( 2012 ), “ Job stress, wellbeing, work-life balance and work-life conflict among Australian academics ”, Electronic Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 8 No. 1 , pp. 25 - 37 .

Biron , M. ( 2013 ), “ Effective and ineffective support: how different sources of support buffer the short–and long–term effects of a working day ”, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 22 No. 2 , pp. 150 - 164 , doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2011.640772 .

Carlson , D.S. and Kacmar , K.M. ( 2000 ), “ Work-family conflict in the organization: do life role values make a difference? ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 26 No. 5 , pp. 1031 - 1054 , doi: 10.1177/014920630002600502 .

Clark , S.C. ( 2000 ), “ Work/family border theory: a new theory of work/family balance ”, Human Relations , Vol. 53 No. 6 , pp. 747 - 770 , doi: 10.1177/0018726700536001 .

Daipuria , P. and Kakar , D. ( 2013 ), “ Work-Life balance for working parents: perspectives and strategies ”, Journal of Strategic Human Resource Management , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 45 - 52 .

Gregory , A. and Milner , S. ( 2009 ), “ Editorial: work-life balance: a matter of choice? ”, Gender, Work & Organization , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 13 , doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00429.x .

Hirschi , A. , Shockley , K.M. and Zacher , H. ( 2019 ), “ Achieving work-family balance: an action regulation model ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 150 - 171 , doi: 10.5465/amr.2016.0409 .

Adame-Sánchez , C. , Caplliure , E.M. and Miquel-Romero , M.J. ( 2018 ), “ Paving the way for coopetition: drivers for work–life balance policy implementation ”, Review of Managerial Science , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 519 - 533 , doi: 10.1007/s11846-017-0271-y .

Adame , C. , Caplliure , E.M. and Miquel , M.J. ( 2016 ), “ Work–life balance and firms: a matter of women? ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 69 No. 4 , pp. 1379 - 1383 , doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.111 .

Adame-Sánchez , C. , González-Cruz , T.F. and Martínez-Fuentes , C. ( 2016 ), “ Do firms implement work–life balance policies to benefit their workers or themselves? ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 69 No. 11 , pp. 5519 - 5523 , doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.164 .

Ahuja , M. and Thatcher , J. ( 2005 ), “ Moving beyond intentions and towards the theory of trying: effects of work environment and gender on post-adoption information technology use ”, MIS Quarterly , Vol. 29 , pp. 427 - 459 .

Alam , M. , Ezzedeen , S.R. and Latham , S.D. ( 2018 ), “ Managing work-generated emotions at home: an exploration of the ‘bright side’ of emotion regulation ”, Human Resource Management Review , Vol. 29 No. 4 , doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.12.002 .

Alexandra , B.T. ( 2014 ), “ Fairness perceptions of work−life balance initiatives: effects on counterproductive work behaviour ”, British Journal of Management , Vol. 25 , pp. 772 - 789 .

Allan , C. , O'Donnell . M. and Peetz , D. ( 1999 ), “ More tasks, less secure, working harder: three dimensions of labour utilization ”, Journal of Industrial Relations , Vol. 41 No. 4 , pp. 519 - 535 .

Allen , T.D. ( 2001 ), “ Family-Supportive work environments: the role of organisational perceptions ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 58 No. 3 , pp. 414 - 435 .

Antonoff , M.B. and Brown , L.M. ( 2015 ), “ Work–life balance: the female cardiothoracic surgeons perspective ”, The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery , Vol. 150 No. 6 , pp. 1416 - 1421 , doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.09.057 .

Barber , L.K. , Conlin , A.L. and Santuzzi , A.M. ( 2019 ), “ Workplace telepressure and work life balance outcomes: the role of work recovery experiences ”, Stress and Health , Vol. 35 No. 3 , doi: 10.1002/smi.2864 .

Beckman , C.M. and Stanko , T.L. ( 2019 ), “ It takes three: relational boundary work, resilience, and commitment among navy couples ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 63 No. 2 , doi: 10.5465/amj.2017.0653 .

Bell , A.S. , Rajendran , D. and Theiler , S. ( 2012 ), “ Job stress, wellbeing, work-life balance and work-life conflict among Australian academics ”, Electronic Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 8 , pp. 25 - 37 .

Bird , J. ( 2006 ), “ Work life balance: doing it right and avoiding the pitfalls ”, Employment Relations Today , Vol. 33 No. 3 , pp. 21 - 30 .

Boiarintseva , G. and Richardson , J. ( 2019 ), “ Work-life balance and male lawyers: a socially constructed and dynamic process ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 48 No. 4 , pp. 866 - 879 , doi: 10.1108/PR-02-2017-0038 .

Brescoll , V.L. , Glass , J. and Sedlovskaya , A. ( 2013 ), “ Ask and ye shall receive? The dynamics of employer‐provided flexible work options and the need for public policy ”, Journal of Social Issues , Vol. 69 No. 2 , pp. 367 - 388 , doi: 10.1111/josi.12019 .

Brough , P. , Timm , C. , Driscoll , M.P.O. , Kalliath , T. , Siu , O.L. , Sit , C. and Lo , D. ( 2014 ), “ Work-life balance: a longitudinal evaluation of a new measure across Australia and New Zealand workers ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 25 No. 19 , pp. 2724 - 2744 .

Brown , H. , Kim , J.S. and Faerman , S.R. ( 2019 ), “ The influence of societal and organizational culture on the use of work-life balance programs: a comparative analysis of the United States and the Republic of Korea ”, The Social Science Journal , doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2019.03.008 .

Buffardi , L.C. , Smith , J.S. , O’Brien , A.S. and Erdwins , C.J. ( 1999 ), “ The impact of dependent-care responsibility and gender on work attitudes ”, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , Vol. 4 No. 4 , pp. 356 - 367 .

Callan , S.J. ( 2008 ), “ Cultural revitalisation: the importance of acknowledging the values of an organization’s ‘golden era’ when promoting work-life balance ”, Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 78 - 97 .

Cannizzo , F. , Mauri , C. and Osbaldiston , N. ( 2019 ), “ Moral barriers between work/life balance policy and practice in academia ”, Journal of Cultural Economy , Vol. 12 No. 4 , pp. 1 - 14 , doi: 10.1080/17530350.2019.1605400 .

Chernyak-Hai , L. and Tziner , A. ( 2016 ), “ The ‘I believe’ and the ‘I invest’ of work-family balance: the indirect influences of personal values and work engagement via perceived organizational climate and workplace burnout ”, Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 10 , doi: 10.1016/j.rpto.2015.11.004 .

Cho , E. and Allen , T.D. ( 2019 ), “ The transnational family: a typology and implications for work-family balance ”, Human Resource Management Review , Vol. 29 No. 1 , pp. 76 - 86 .

Clark , S.C. ( 2000 ), “ Work/family border theory: a new theory of work/family balance ”, Human Relations , Vol. 53 No. 6 , pp. 747 - 770 .

Crawford , W.S. , Thompson , M.J. and Ashforth , B.E. ( 2019 ), “ Work-life events theory: making sense of shock events in dual-earner couples ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 194 - 212 .

Daipuria , P. and Kakar , D. ( 2013 ), “ Work-Life balance for working parents: perspectives and strategies ”, Journal of Strategic Human Resource Management , Vol. 2 , pp. 45 - 52 .

Dave , J. and Purohit , H. ( 2016 ), “ Work life balance and perception: a conceptual framework ”, The Clarion- International Multidisciplinary Journal , Vol. 5 No. 1 , pp. 98 - 104 .

Dhanya , J.S.1. and Kinslin , D. ( 2016 ), “ A study on work life balance of teachers in engineering colleges in Kerala ”, Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences , Vol. 9 No. 4 , pp. 2098 - 2104 .

Divine , L.M. , Perez , M.J. , Binder , P.S. , Kuroki , L.M. , Lange , S.S. , Palisoul , M. and Hagemann , A.R. ( 2017 ), “ Improving work-life balance: a pilot program of workplace yoga for physician wellness ”, Gynecologic Oncology , Vol. 145 , p. 170 , doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.389 .

Downes , C. and Koekemoer , E. ( 2012 ), “ Work-life balance policies: the use of flexitime ”, Journal of Psychology in Africa , Vol. 22 No. 2 , pp. 201 - 208 .

Eagle , B.W. , Miles , E.W. and Icenogle , M.L. ( 1997 ), “ Inter-role conflicts and the permeability of work and family domains: are there gender differences? ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 50 No. 2 , pp. 168 - 184 .

Ehrhardt , K. and Ragins , B.R. ( 2019 ), “ Relational attachment at work: a complementary fit perspective on the role of relationships in organizational life ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 62 No. 1 , pp. 248 - 282 , doi: 10.5465/amj.2016.0245 .

Emre , O. and De Spiegeleare , S. ( 2019 ), “ The role of work–life balance and autonomy in the relationship between commuting, employee commitment and well-being ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 32 No. 11 , pp. 1 - 25 , doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1583270 .

Feldman , D.C. ( 2002 ), “ Managers' propensity to work longer hours: a multilevel analysis ”, Human Resource Management Review , Vol. 12 No. 3 , pp. 339 - 357 , doi: 10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00064-5 .

Forsyth , S. and Debruyne , P.A. ( 2007 ), “ The organisational pay-offs for perceived work-life balance support ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources , Vol. 45 No. 1 , pp. 113 - 123 , doi: 10.1177/1038411107073610 .

Galea , C. , Houkes , I. and Rijk , A.D. ( 2014 ), “ An insider’s point of view: how a system of flexible working hours helps employees to strike a proper balance between work and personal life ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 25 No. 8 , pp. 1090 - 1111 .

Greenhaus , J.H. , Collins , K.M. and Shaw , J.D. ( 2003 ), “ The relation between work–family balance and quality of life ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 63 No. 3 , pp. 510 - 531 .

Gregory , A. and Milner , S. ( 2009 ), “ Editorial: work–life balance: a matter of choice? ”, Gender, Work & Organization , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 13 .

Groysberg , B. and Abrahams , R. ( 2014 ), “ Manage your work, manage your life ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 92 No. 3 , pp. 58 - 66 .

Gumani , M.A. , Fourie , M.E. and Blanch , M.J.T. ( 2013 ), “ Inner strategies of coping with operational work amongst SAPS officers ”, SA Journal of Industrial Psychology , Vol. 39 No. 2 , pp. 1151 - 1161 , doi: 10.4102/sajip. v39i2.1151 .

Haar , J. and Roche , M. ( 2010 ), “ Family-Supportive organization perceptions and employee outcomes: the mediating effects of life satisfaction ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 21 No. 7 , pp. 999 - 1014 .

Haar , J.M. , Sune , A. , Russo , M. and Ollier-Malaterre , A. ( 2019 ), “ A cross-national study on the antecedents of work–life balance from the fit and balance perspective ”, Social Indicators Research , Vol. 142 No. 1 , pp. 261 - 282 , doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-1875-6 .

Haider , S. , Jabeen , S. and Ahmad , J. ( 2018 ), “ Moderated mediation between work life balance and employee job performance: the role of psychological wellbeing and satisfaction with co-workers ”, Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones , Vol. 34 No. 1 , pp. 29 - 37 , doi: 10.5093/jwop2018a4 .

Hill , E.J. , Hawkins , A.J. , Ferris , M. and Weitzman , M. ( 2001 ), “ Finding an extra day a week: the positive influence of perceived job flexibility on work and family life balance ”, Family Relations , Vol. 50 No. 1 , pp. 49 - 65 .

Hirschi , A. , Shockley , K.M. and Zacher , H. ( 2019 ), “ Achieving work-family balance: an action regulation model ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 150 - 171 .

Hofmann , V. and Stokburger-Sauer , N.E. ( 2017 ), “ The impact of emotional labor on employees’ work-life balance perception and commitment: a study in the hospitality industry ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 65 , pp. 47 - 58 , doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.003 .

Hughes , D.L. and Galinsky , E. ( 1994 ), “ Gender, job and family conditions, and psychological symptoms ”, Psychology of Women Quarterly , Vol. 18 No. 2 , pp. 251 - 270 .

Jensen , M.T. ( 2014 ), “ Exploring business travel with work–family conflict and the emotional exhaustion component of burnout as outcome variables: the job demands–resources perspective ”, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 23 No. 4 , pp. 497 - 510 , doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2013.787183 .

Jiang , H. and Shen , H. ( 2018 ), “ Supportive organizational environment, work-life enrichment, trust and turnover intention: a national survey of PRSA membership ”, Public Relations Review , Vol. 44 No. 5 , pp. 681 - 689 , doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.08.007 .

Johari , J. , Yean Tan , F. and TjikZulkarnain , Z.I. ( 2018 ), “ Autonomy, workload, work-life balance and job performance among teachers ”, International Journal of Educational Management , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 107 - 120 , doi: 10.1108/IJEM-10-2016-0226 .

Johnston , D.D. and Swanson , D.H. ( 2007 ), “ Cognitive acrobatics in the construction of worker–mother identity ”, Sex Roles , Vol. 57 Nos 5/6 , pp. 447 - 459 , doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9267-4 .

Kalliath , P. , Kalliath , T. , Chan , X.W. and Chan , C. ( 2018 ), “ Linking work–family enrichment to job satisfaction through job Well-Being and family support: a moderated mediation analysis of social workers across India ”, The British Journal of Social Work , Vol. 49 No. 1 , pp. 234 - 255 .

Kalliath , T. and Brough , P. ( 2008 ), “ Work–life balance: a review of the meaning of the balance construct ”, Journal of Management & Organization , Vol. 14 No. 3 , pp. 323 - 327 .

Kim , H.K. ( 2014 ), “ Work-life balance and employees’ performance: the mediating role of affective commitment ”, Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal , Vol. 6 , pp. 37 - 51 .

Kowitlawkul , Y. , Yap , S.F. , Makabe , S. , Chan , S. , Takagai , J. , Tam , W.W.S. and Nurumal , M.S. ( 2019 ), “ Investigating nurses’ quality of life and work‐life balance statuses in Singapore ”, International Nursing Review , Vol. 66 No. 1 , pp. 61 - 69 , doi: 10.1111/inr.12457 .

Li , A. , McCauley , K.D. and Shaffer , J.A. ( 2017 ), “ The influence of leadership behavior on employee work-family outcomes: a review and research agenda ”, Human Resource Management Review , Vol. 27 No. 3 , pp. 458 - 472 , doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.02.003 .

Lingard , H. , Brown , K. , Bradley , L. , Bailey , C. and Townsend , K. ( 2007 ), “ Improving employees’ work-life balance in the construction industry: project alliance case study ”, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 133 No. 10 , pp. 807 - 815 .

Liu , N.C. and Wang , C.Y. ( 2011 ), “ Searching for a balance: work–family practices, work–team design, and organizational performance ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 22 No. 10 , pp. 2071 - 2085 .

Lundberg , U. , Mardberg , B. and Frankenhaeuser , M. ( 1994 ), “ The total workload of male and female white collar workers as related to age, occupational level, and number of children ”, Scandinavian Journal of Psychology , Vol. 35 No. 4 , pp. 315 - 327 .

Lyness , K.S. and Judiesch , M.K. ( 2014 ), “ Gender egalitarianism and work–life balance for managers: multisource perspectives in 36 countries ”, Applied Psychology , Vol. 63 No. 1 , pp. 96 - 129 .

McCarthy , A. , Darcy , C. and Grady , G. ( 2010 ), “ Work-life balance policy and practice: understanding line manager attitudes and behaviors ”, Human Resource Management Review , Vol. 20 No. 2 , pp. 158 - 167 , doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.12.001 .

McCarthy , A. , Cleveland , J.N. , Hunter , S. , Darcy , C. and Grady , G. ( 2013 ), “ Employee work–life balance outcomes in Ireland: a multilevel investigation of supervisory support and perceived organizational support ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 24 No. 6 , pp. 1257 - 1276 .

McDonald , P. , Brown , K. and Bradley , L. ( 2005 ), “ Explanations for the provision-utilisation gap in work-life policy ”, Women in Management Review , Vol. 20 No. 1 , pp. 37 - 55 .

Matteson , M.T. and Ivancevich , J.M. ( 1987 ), “ Individual stress management intervention: evaluation of techniques ”, Journal of Managerial Psychology , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 24 - 31 .

Mattessich , S. , Shea , K. and Whitaker-Worth , D. ( 2017 ), “ Parenting and female dermatologists’ perceptions of work-life balance ”, International Journal of Women's Dermatology , Vol. 3 No. 3 , pp. 127 - 130 , doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.04.001 .

Matthews , R.A. , Mills , M.J. , Trout , R.C. and English , L. ( 2014 ), “ Family-supportive supervisor behaviors, work engagement, and subjective well-being: a contextually dependent mediated process ”, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , Vol. 19 No. 2 , p. 168 , doi: 10.1037/a0036012 .

Maura , M.S. , Russell , J. , Matthews , A. , Henning , J.B. and Woo , V.A. ( 2014 ), “ Family-supportive organizations and supervisors: how do they influence employee outcomes and for whom? ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 25 No. 12 , pp. 1763 - 1785 .

Michel , A. , Bosch , C. and Rexroth , M. ( 2014 ), “ Mindfulness as a cognitive–emotional segmentation strategy: an intervention promoting work–life balance ”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 87 No. 4 , pp. 733 - 754 .

Moore , J.E. ( 2000 ), “ One road to turnover: an examination of work exhaustion in technology professionals ”, MIS Quarterly , Vol. 24 No. 1 , pp. 141 - 168 .

Muna , F.A. and Mansour , N. ( 2009 ), “ Balancing work and personal life: the leader as ACROBAT ”, Journal of Management Development , Vol. 28 No. 2 , pp. 121 - 133 , doi: 10.1108/02621710910932089 .

Mushfiqur , R. , Mordi , C. , Oruh , E.S. , Nwagbara , U. , Mordi , T. and Turner , I.M. ( 2018 ), “ The impacts of work-life-balance (WLB) challenges on social sustainability: the experience of Nigerian female medical doctors ”, Employee Relations , Vol. 40 No. 5 , pp. 868 - 888 , doi: 10.1108/ER-06-2017-0131 .

Onyishi , L.A. ( 2016 ), “ Stress coping strategies, perceived organizational support, and marital status as predictors of work-life balance among Nigerian bank employees ”, Social Indicators Research , Vol. 128 No. 1 , pp. 147 - 159 .

Potgieter , S.C. and Barnard , A. ( 2010 ), “ The construction of work-life balance: the experience of black employees in a call-centre ”, SA Journal of Industrial Psychology , Vol. 36 No. 1 , pp. 8 .

Rudman , L.A. and Mescher , K. ( 2013 ), “ Penalizing men who request a family leave: is flexibility stigma a femininity stigma? ”, Journal of Social Issues , Vol. 69 No. 2 , pp. 322 - 340 , doi: 10.1111/josi.12017 .

Russo , M. , Shteigman , A. and Carmeli , A. ( 2016 ), “ Workplace and family support and work–life balance: implications for individual psychological availability and energy at work ”, The Journal of Positive Psychology , Vol. 11 No. 2 , pp. 173 - 188 , doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1025424 .

Sandow , E. ( 2019 ), “ Til work do us part: the social fallacy of long-distance commuting ”, Integrating Gender into Transport Planning , 121 - 144 . Palgrave Macmillan , Cham , doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-05042-9_6

Sigroha , A. ( 2014 ), “ Impact of work life balance on working women: a comparative analysis ”, The Business and Management Review , Vol. 5 , pp. 22 - 30 .

Spector , P.E. ( 1997 ), Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences , Sage , Thousand Oaks. CA .

Swanson , V. , Power , K.G. and Simpson , R.J. ( 1998 ), “ Occupational stress and family life: a comparison of male and female doctors ”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 71 No. 3 , pp. 237 - 260 .

Tammy , D.A. and Kaitlin , M.K. ( 2012 ), “ Trait mindfulness and work–family balance among working parents: the mediating effects of vitality and sleep quality ”, Journal of Vocational Behaviour , Vol. 80 No. 2 , pp. 372 - 379 , doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.09.002 .

Talukder , A.K.M. , Vickers , M. and Khan , A. ( 2018 ), “ Supervisor support and work-life balance: impacts on job performance in the Australian financial sector ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 47 No. 3 , pp. 727 - 744 , doi: 10.1108/PR-12-2016-0314 .

Tenney , E.R. , Poole , J.M. and Diener , E. ( 2016 ), “ Does positivity enhance work performance? Why, when, and what we don’t know ”, Research in Organizational Behavior , Vol. 36 , pp. 27 - 46 .

Theorell , T. and Karasek , R.A. ( 1996 ), “ Current issues relating to psychosocial job strain and CV disease research ”, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , Vol. 1 No. 1 , pp. 9 - 26 .

Turanlıgil , F.G. and Farooq , M. ( 2019 ), “ Work-life balance in tourism industry ”, in Contemporary Human Resources Management in the Tourism Industry , IGI Global , pp. 237 - 274 .

Waters , M.A. and Bardoel , E.A. ( 2006 ), “ Work – family policies in the context of higher education: useful or symbolic? ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 67 - 82 .

Wayne , J. , Randel , A. and Stevens , J. ( 2006 ), “ The role of identity and work family support in WFE and work-related consequences ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 69 No. 3 , pp. 445 - 461 .

Whitehouse , G. , Hosking , A. and Baird , M. ( 2008 ), “ Returning too soon? Australian mothers' satisfaction with maternity leave duration ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources , Vol. 46 No. 3 , pp. 188 - 302 .

Yadav , R.K. and Dabhade , N. ( 2013 ), “ Work life balance amongst the working women – a case study of SBI ”, International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences , Vol. 7 , pp. 1 - 22 .

Yu , H.H. ( 2019 ), “ Work-life balance: an exploratory analysis of family-friendly policies for reducing turnover intentions among women in U.S. Federal law enforcement ”, International Journal of Public Administration , Vol. 42 No. 4 , pp. 345 - 357 , doi: 10.1080/01900692.2018.1463541 .

Zheng , C. , Kashi , K. , Fan , D. , Molineux , J. and Ee , M.S. ( 2016 ), “ Impact of individual coping strategies and organisational work–life balance programmes on Australian employee well-being ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 27 No. 5 , pp. 501 - 526 .

Zucker , R. ( 2017 ), “ Help your team achieve work-life balance – even when you can’t ”, Harvard Business Review , available at: https://hbr.org/2017/08/help-your-team-achieve-work-life-balance-even-when-you-cant

Acknowledgements

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Compliance of ethical standard statement: The results reported in this manuscript were conducted in accordance with general ethical guidelines in psychology.

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Redefining work-life balance: women at the helm of the post-pandemic coworking revolution

- Original Article

- Published: 11 August 2023

- Volume 26 , pages 755–766, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Xinran Guo 1 &

- Xiaohong Zhu 2

537 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The post-pandemic era has transformed work-life boundaries, driven by factors such as working hours, an increased number of working women and single parents, the implementation of various ICTs, and the rise of flexible work arrangements. This study examines the role of female workers and entrepreneurs in establishing and managing coworking spaces (CSs) designed to improve work-life balance through flexible scheduling and location options. The challenges faced by female entrepreneurs in promoting an inclusive society and economic system are also explored, as well as the benefits experienced by independent workers and teleworkers in terms of networking, social interaction, knowledge exchange, and community building. The “She Economy” is analyzed in three stages: germination, growth, and maturity, considering challenges from both family and workplaces. This paper investigates the background of female identity and the ideological transformation of female identity in the consumption process after the pandemic, using mass media, especially female-focused media, as a lens. Finally, the paper proposes recommendations for the future development of the “She Economy” from the perspectives of communicators, women, and the social environment.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

“If Only I Were a Male”: Work, Value, and the Female Body

Happily Exhausted: Work Family Dynamics in India

New Ways of Working During (and After) the COVID-19 Pandemic: Truly Smart for Women?

Blumberg RL (1984) A general theory of gender stratification. Sociol Theory 2:23–101. https://doi.org/10.2307/223343

Bollinger C, Ding X, Lugauer S (2022) The expansion of higher education and household saving in China. China Econ Rev 71:101736

Article Google Scholar

Brooke M (2019) The Singaporean paralympics and its media portrayal: real sport? Men-only? Commun Sport 7 (4):446–465

Chauhan P (2022) “I Have No Room of My Own”: COVID-19 pandemic and work-from-home through a gender lens. Gend Issues 39(4):507–533

Chunchen S (2008) Symbol consumption and identity ethics. J Moral Civ 1:7–10

Google Scholar

Downing NE, Roush KL (1985) From passive acceptance to active commitment: a model of feminist identity development for women. Couns Psychol 13:695–709

Fei W (2003) Economics of mass media. Zhejiang University Press, Hangzhou, p 27

Han W, Zhang X, Zhang Z (2019) The role of land tenure security in promoting rural women’s empowerment: empirical evidence from rural China. Land Use Policy 86:280–289

Kabeer N (2020) Women’s empowerment and economic development: a feminist critique of storytelling practices in “randomista” economics. Fem Econ 26(2):1–26

Lei W (2018) Media, power and gender: the change of women’s media image and gender equality in New China. Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press, Shanghai, p 255

Li X (2020) How powerful is the female gaze? The implication of using male celebrities for promoting female cosmetics in China. Glob Media China 5(1):55–68

Lin Z, Yang L (2019) Individual and collective empowerment: women’s voices in the# MeToo movement in China. Asian J Women's Stud 25(1):117–131

Lyu X, Fan Y (2020) Research on the relationship of work family conflict, work engagement and job crafting: a gender perspective. Curr Psychol 41:1767–1777

Mao C (2020) Feminist activism via social media in China. Asian J Women's Stud 26(2):245–258

Nowak J (2020) Office space development and respective effects on productivity and work-life balance.

Qiao F, Wang Y (2022) The myths of beauty, age, and marriage: femvertising by masstige cosmetic brands in the Chinese market. Soc Semiot 32(1):35–57

Social Media Research Center (2022) Women in the news about COVID-19: an analysis for the content of 23 Chinese media Peking University, March 7, 2022. https://snm.pku.edu.cn/info/1030/1973.html .

United Nations Women (2020) From insight to action: gender equality in the wake of COVID-19, vol 7. UN Women, United States, p 16

Wang Q (2022) Women starting up in the digital creative industries in China (Doctoral dissertation. Curtin University)

Xiao L, Qi C (2016) Consumer group identity and group uniqueness: a study on the impact of culture-targeted advertising evaluation. Consum Econ 5:6

Xueqi S (2020) Under the epidemic, she economy, silver economy and other subdivisions of the economy become popular. In: Chinese consumer news May 26, 2020. https://www.ccn.com.cn/Content/2020/07-29/1622130251.html

Yanyue L (2019) Analysis of female media image and its empowerment logic -- taking SK-II advertising as an example. News Res Guide 10:212–246

Yeung WJJ, Yang Y (2020) Labor market uncertainties for youth and young adults: an international perspective. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 688(1):7–19

Yin S, Sun Y (2021) Intersectional digital feminism: assessing the participation politics and impact of the MeToo movement in China. Fem Media Stud 21(7):1176–1192

Yu H, Cui L (2019) China’s e-commerce: empowering rural women? China Q 238:418–437

Zani B (2019) Gendered transnational ties and multipolar economies: Chinese migrant women’s Wechat commerce in Taiwan. Int Migr 57(4):232–246

Zeng J (2020) MeToo as connective action: a study of the anti-sexual violence and anti-sexual harassment campaign on Chinese social media in 2018. J Pract 14(2):171–190

Zhang X, Ma L, Xu B, Xu F (2019) How social media usage affects employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intention: an empirical study in China. Inf Manag 56(6):103136

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Ningbo Branch, CITIC Securities Company Limted, Ningbo, China

School of Media and Law, NingboTech Universtiy, Ningbo, China

Xiaohong Zhu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Xiaohong Zhu .

Ethics declarations

Human and animal rights.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Guo, X., Zhu, X. Redefining work-life balance: women at the helm of the post-pandemic coworking revolution. Arch Womens Ment Health 26 , 755–766 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-023-01352-x

Download citation

Received : 08 May 2023

Accepted : 14 July 2023

Published : 11 August 2023

Issue Date : December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-023-01352-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- She economy

- Female media

- Post-pandemic era

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Psychol Med

- v.32(2); Jul-Dec 2010

Work–Life Balance among Married Women Employees

N. krishna reddy.

Department of Psychiatric Social Work, NIMHANS, Bangalore, India

M. N. Vranda

B. p. nirmala, b. siddaramu.

1 Department of Social Work, Jnana Bharathi Post, University of Bangalore, Bangalore, India

Family–work conflict (FWC) and work–family conflict (WFC) are more likely to exert negative influences in the family domain, resulting in lower life satisfaction and greater internal conflict within the family. Studies have identified several variables that influence the level of WFC and FWC. Variables such as the size of family, the age of children, the work hours and the level of social support impact the experience of WFC and FWC. However, these variables have been conceptualized as antecedents of WFC and FWC; it is also important to consider the consequences these variables have on psychological distress and wellbeing of the working women.

to study various factors which could lead to WFC and FWC among married women employees.

Materials and Methods:

The sample consisted of a total of 90 married working women of age between 20 and 50 years. WFC and FWC Scale was administered to measure WFC and FWC of working women. The obtained data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Carl Pearson's Correlation was used to find the relationship between the different variables.

Findings and Conclusion:

The findings of the study emphasized the need to formulate guidelines for the management of WFCs at organizational level as it is related to job satisfaction and performance of the employees.

INTRODUCTION

Indian families are undergoing rapid changes due to the increased pace of urbanization and modernization. Indian women belonging to all classes have entered into paid occupations. At the present time, Indian women's exposure to educational opportunities is substantially higher than it was some decades ago, especially in the urban setting. This has opened new vistas, increased awareness and raised aspirations of personal growth. This, along with economic pressure, has been instrumental in influencing women's decision to enter the work force. Most studies of employed married women in India have reported economic need as being the primary reason given for working.[ 1 , 2 ]

Women's employment outside the home generally has a positive rather than negative effect on marriage. Campbell et al .[ 3 ] studied the effects of family life on women's job performance and work attitudes. The result revealed that women with children were significantly lower in occupational commitment relative to women without children; contrary to expectation, women with younger children outperformed women with older children. Makowska[ 4 ] studied psychosocial determinants of stress and well-being among working women. The significance of the work-related stressors was evidently greater than that of the stressors associated with the family function, although the relationship between family functioning, stress and well-being was also significant.

Multiple roles and professional women

Super[ 5 ] identified six common life roles. He indicated that the need to balance these different roles simultaneously is a reality for most individuals at various stages throughout their lives. Rather than following a transitional sequence from one role to another, women are required to perform an accumulation of disparate roles simultaneously, each one with its unique pressures.[ 6 ] Multiple role-playing has been found to have both positive and negative effects on the mental health and well-being of professional women. In certain instances, women with multiple roles reported better physical and psychological health than women with less role involvement. In other words, they cherished motivational stimulation, self-esteem, a sense of control, physical stamina, and bursts of energy.[ 7 ] However, multiple roles have also been found to cause a variety of adverse effects on women's mental and physical health, including loss of appetite, insomnia, overindulgence, and back pains.[ 8 ]

Work–life balance

An increasing number of articles have promoted the importance of work–life balance. This highlights the current concern within society and organizations about the impact of multiple roles on the health and well-being of professional women and its implications regarding work and family performance, and women's role in society. The following variables influencing the experience of work–life balance were identified while reviewing the international literature.

- The multiple roles performed by women[ 9 – 11 ]

- Role strain experienced because of multiple roles, i.e., role conflict and role overload[ 12 , 13 ]

- Organization culture and work dynamics: Organizational values supporting work–life balance have positive work and personal well-being consequences[ 14 , 15 ]

- Personal resources and social support: Several studies confirmed the positive relationship between personalities, emotional support and well-being[ 16 – 18 ]

- Career orientation and career stage in which women careers need to be viewed in the context of their life course and time lines[ 19 , 20 ]

- Coping and coping strategies: Women use both emotional and problem-focused coping strategies to deal with role conflict.[ 21 ]

Work–family conflict and family–work conflict

Work–life balance is the maintenance of a balance between responsibilities at work and at home. Work and family have increasingly become antagonist spheres, equally greedy of energy and time and responsible for work–family conflict (WFC).[ 22 ] These conflicts are intensified by the “cultural contradictions of motherhood”, as women are increasingly encouraged to seek self-fulfillment in demanding careers, they also face intensified pressures to sacrifice themselves for their children by providing “intensive parenting”, highly involved childrearing and development.[ 23 ] Additional problems faced by employed women are those associated with finding adequate, affordable access to child and elderly care.[ 24 , 25 ]

WFC has been defined as a type of inter-role conflict wherein some responsibilities from the work and family domains are not compatible and have a negative influence on an employee's work situation.[ 12 ] Its theoretical background is a scarcity hypothesis which describes those individuals in certain, limited amount of energy. These roles tend to drain them and cause stress or inter-role conflict.[ 26 – 28 ] Results of previous research indicate that WFC is related to a number of negative job attitudes and consequences including lower overall job satisfaction[ 29 ] and greater propensity to leave a position.[ 30 ]

Family–work conflict (FWC) is also a type of inter-role conflict in which family and work responsibilities are not compatible.[ 12 ] Previous research suggests that FWC is more likely to exert its negative influences in the home domain, resulting in lower life satisfaction and greater internal conflict within the family unit. However, FWC is related to attitudes about the job or workplace.[ 31 ] Both WFC and FWC basically result from an individual trying to meet an overabundance of conflicting demands from the different domains in which women are operating.

Workplace characteristics can also contribute to higher levels of WFC. Researchers have found that the number of hours worked per week, the amount and frequency of overtime required, an inflexible work schedule, unsupportive supervisor, and an inhospitable organizational culture increase the likelihood that women employees will experience conflict between their work and family role.[ 12 , 32 , 33 ] Baruch and Barnett[ 34 ] found that women who had multiple life roles (e.g., mother, wife, employee) were less depressed and had higher self-esteem than women who were more satisfied in their marriages and jobs compared to women and men who were not married, unemployed, or childless. However, authors argued quality of role rather than the quantity of roles that matters. That is, there is a positive association between multiple roles and good mental health when a woman likes her job and likes her home life.

WFC and FWC are generally considered distinct but related constructs. Research to date has primarily investigated how work interferes or conflicts with family. From work–family and family–work perspectives, this type of conflict reflects the degree to which role responsibilities from the work and family domains are incompatible. That is “participation in the work (family) role is made more difficult by virtue of participation in the family (work) role”.[ 12 ]

Frone et al .[ 35 ] suggested that WFC and FWC are related through a bi-directional nature where one can affect the other. The work domain variables such as work stress may cause work roles to interfere with family roles; the level of conflict in the family domain impacts work activities, causing more work conflict, thus creating a vicious cycle. Therefore, work domain variables that relate to WFC indirectly affect FWC through the bi-directional relationship between each construct. Family responsibility might be related to WFC when the employee experiences a very high work overload that impacts the employee's ability to perform even minor family-related roles. Such a situation likely affects WFC through the bi-directional nature of the two constructs. While no researchers have considered the relationship between these constructs in a full measurement model, Carlson and Kacmar[ 36 ] used structural model and found positive and significant paths between WFC and FWC.

Work stress: Its relation with WFC and FWC