- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Retrospective Study: Definition & Examples

By Jim Frost 1 Comment

What is a Retrospective Study?

A retrospective study an experimental design that looks back in time and assesses events that have already occurred. The researchers already know the outcome for each subject when the project starts. Instead of recording data going forward as events happen, these studies use participant recollection and data that were previously recorded for reasons not relating to the project. These studies typically don’t follow patients into the future.

In retrospective designs, the researchers collect their data using existing records. Consequently, they can complete their assessment more quickly and inexpensively than a prospective study that must follow subjects over time and record the data under carefully controlled conditions. However, the data that a retrospective study uses might not have been measured consistently or accurately because they weren’t explicitly designed to be part of a study.

The statistical analysis for a retrospective study is frequently the same as for prospective designs (looking forward). The main difference is that the project occurs after the outcomes are known rather than how researchers analyze the data.

Statisticians consider retrospective designs to be inferior to prospective methods because they tend to introduce more bias and confounding. Retrospective studies are observational studies by necessity because they assess past events and it is impossible to perform a randomized, controlled experiment with them. However, they can be quicker and cheaper to complete, making them a good choice for preliminary research. Findings from a retrospective study can help inform a prospective experimental design. Learn more about Experimental Designs .

Retrospective Study Designs

Retrospective studies use various designs. While these designs differ in detail, they all tend to compare subjects with and without a condition and determine how they differ. Using the usual hypothesis tests, researchers can determine whether there are statistically significant relationships between subject variables (risk factors , personal characteristics, etc.) and the outcome of interest.

Cohort and case-control studies are standard retrospective designs. Let’s learn more about them!

Retrospective Cohort Study

This study design compares groups of subjects who are similar overall but differ in a particular characteristic, such as exposure to a risk factor. Because it is a retrospective study, the researchers find individuals where the outcomes are known when the project starts. Retrospective cohort studies frequently determine whether exposure to risk and protective factors affects an outcome. These are longitudinal studies that use existing datasets to look back at events that have already occurred. Learn more about Longitudinal Studies: Overview, Examples & Benefits .

In these projects, researchers use databases and medical records to identify patients and gather information about them. They can also ask subjects to recall their exposure over time. Then the researchers analyze the data to determine whether the risk factor correlates with the outcome of interest.

Suppose researchers hypothesize that exposure to a chemical increases skin cancer and conduct a retrospective cohort study. In that case, they can form a cohort based on a group commonly exposed to that chemical (e.g., a particular job). Then they access medical databases and records to collect their data. After identifying their subjects and obtaining the medical information, they can immediately analyze the data, comparing the outcomes for those with and without exposure.

Learn more about Cohort Studies .

Case-Control Studies

Case-control designs are generally retrospective studies. Like their cohort counterparts, case-control studies compare two groups of people, those with and without a condition. These designs both assess risk and protective factors.

Retrospective cohort and case-control studies are similar but generally have differing goals. Cohort designs typically assess known risk factors and how they affect outcomes at different times. Case-control studies evaluate a particular incident, and it is an exploratory design to identify potential risk factors.

For example, a case-control assessment might evaluate an episode of severe illness occurring after a company picnic to identify potential food culprits.

Learn more about Case-Control Studies .

Advantages of a Retrospective Study

A retrospective study tends to have the following advantages compared to a prospective design:

Cheaper : You don’t need a lab or equipment to measure information. Others did that for you!

Faster : The events have already occurred in a retrospective study—no need to wait for them to happen and then look for the differences between the groups.

Great for rare diseases : You can specifically look through a database for individuals with a rare disease or condition. In a prospective experiment, you need an immense sample size and hope enough of the rare outcomes occur for you to analyze.

Disadvantages of a Retrospective Study

Unfortunately, they tend to have the following disadvantages relating to a greater propensity for inaccuracies, inconsistencies, lack of controlled conditions, and bias:

- A retrospective study uses data measured for other purposes.

- Different people, procedures, and equipment might have recorded the data, leading to inconsistencies.

- Measurements might have occurred under differing conditions.

- Control variables might not be measured, leading to confounding.

- Recall bias.

Dean R Hess, Retrospective Studies and Chart Reviews , Respiratory Care , October 2004, 49 (10) 1171-1174.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

November 7, 2022 at 8:26 am

Coincidentally, I just read this Israeli retrospective cohort study regarding the incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis in unvaxxed post-COVID-19 patients: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35456309/

Good news for a change.

Comments and Questions Cancel reply

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

Published on February 10, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

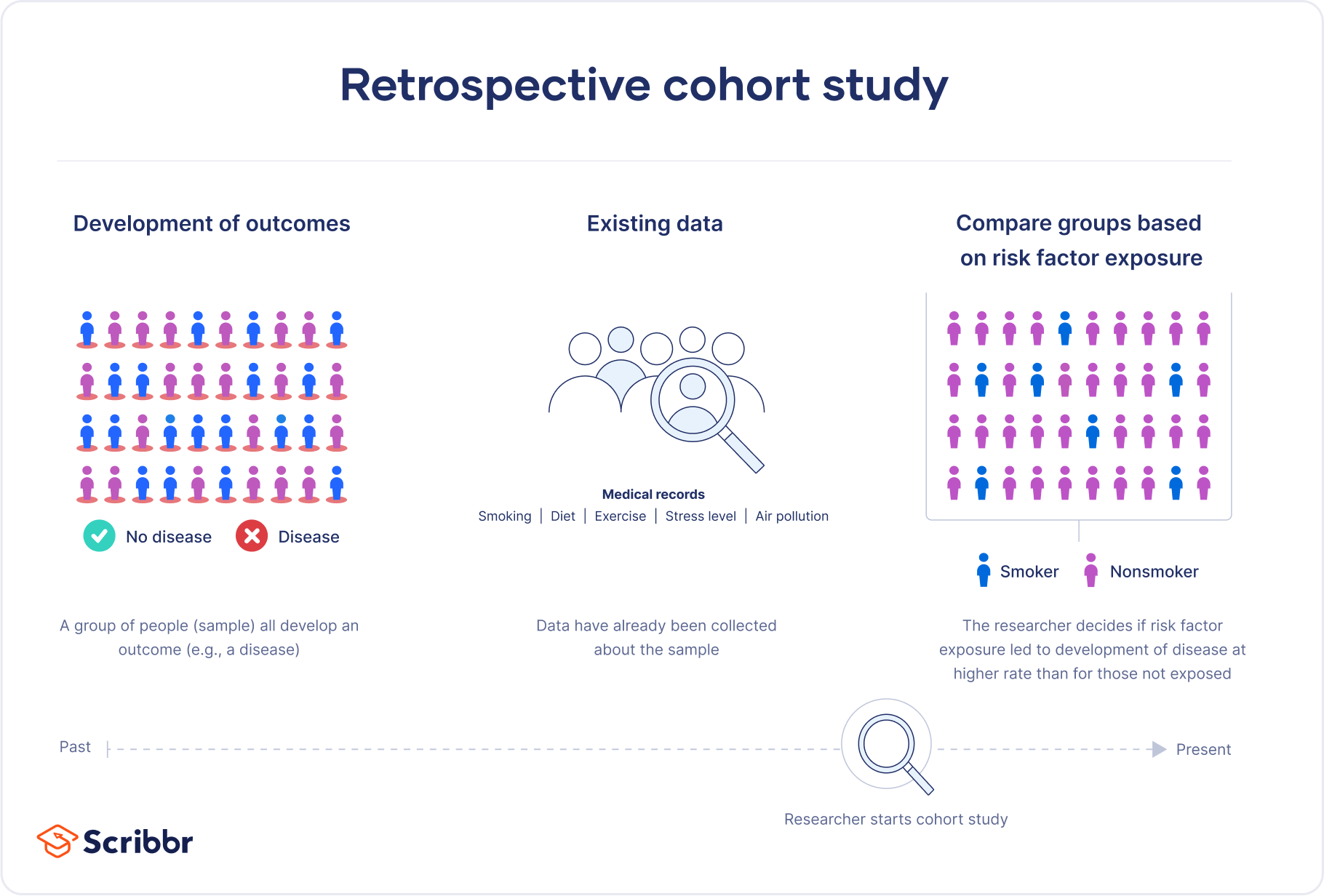

A retrospective cohort study is a type of observational study that focuses on individuals who have an exposure to a disease or risk factor in common. Retrospective cohort studies analyze the health outcomes over a period of time to form connections and assess the risk of a given outcome associated with a given exposure.

It is crucial to note that in order to be considered a retrospective cohort study, your participants must already possess the disease or health outcome being studied.

Table of contents

When to use a retrospective cohort study, examples of retrospective cohort studies, advantages and disadvantages of retrospective cohort studies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

Retrospective cohort studies are a type of observational study . They are often used in fields related to medicine to study the effect of exposures on health outcomes. While most observational studies are qualitative in nature, retrospective cohort studies are often quantitative , as they use preexisting secondary research data. They can be used to conduct both exploratory research and explanatory research .

Retrospective cohort studies are often used as an intermediate step between a weaker preliminary study and a prospective cohort study , as the results gleaned from a retrospective cohort study strengthen assumptions behind a future prospective cohort study.

A retrospective cohort study could be a good fit for your research if:

- A prospective cohort study is not (yet) feasible for the variables you are investigating.

- You need to quickly examine the effect of an exposure, outbreak, or treatment on an outcome.

- You are seeking to investigate an early-stage or potential association between your variables of interest.

Retrospective cohort studies use secondary research data, such as existing medical records or databases, to identify a group of people with an exposure or risk factor in common. They then look back in time to observe how the health outcomes developed. Case-control studies rely on primary research , comparing a group of participants with a condition of interest to a group lacking that condition in real time.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Retrospective cohort studies are common in fields like medicine, epidemiology, and healthcare.

You collect data from participants’ exposure to organophosphates, focusing on variables like the timing and duration of exposure, and analyze the health effects of the exposure. Example: Healthcare retrospective cohort study You are examining the relationship between tanning bed use and the incidence of skin cancer diagnoses.

Retrospective cohort studies can be a good fit for many research projects, but they have their share of advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of retrospective cohort studies

- Retrospective cohort studies are a great choice if you have any ethical considerations or concerns about your participants that prevent you from pursuing a traditional experimental design .

- Retrospective cohort studies are quite efficient in terms of time and budget. They require fewer subjects than other research methods and use preexisting secondary research data to analyze them.

- Retrospective cohort studies are particularly useful when studying rare or unusual exposures, as well as diseases with a long latency or incubation period where prospective cohort studies cannot yet form conclusions.

Disadvantages of retrospective cohort studies

- Like many observational studies, retrospective cohort studies are at high risk for many research biases . They are particularly at risk for recall bias and observer bias due to their reliance on memory and self-reported data.

- Retrospective cohort studies are not a particularly strong standalone method, as they can never establish causality . This leads to low internal validity and external validity .

- As most patients will have had a range of healthcare professionals involved in their care over their lifetime, there is significant variability in the measurement of risk factors and outcomes. This leads to issues with reliability and credibility of data collected.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

The primary difference between a retrospective cohort study and a prospective cohort study is the timing of the data collection and the direction of the study.

A retrospective cohort study looks back in time. It uses preexisting secondary research data to examine the relationship between an exposure and an outcome. Data is collected after the outcome you’re studying has already occurred.

Alternatively, a prospective cohort study follows a group of individuals over time. It collects data on both the exposure and the outcome of interest as they are occurring. Data is collected before the outcome of interest has occurred.

Retrospective cohort studies are at high risk for research biases like recall bias . Whenever individuals are asked to recall past events or exposures, recall bias can occur. This is because individuals with a certain disease or health outcome of interest are more likely to remember and/or report past exposures differently to individuals without that outcome. This can result in an overestimation or underestimation of the true relationship between variables and affect your research.

No, retrospective cohort studies cannot establish causality on their own.

Like other types of observational studies , retrospective cohort studies can suggest associations between an exposure and a health outcome. They cannot prove without a doubt, however, that the exposure studied causes the health outcome.

In particular, retrospective cohort studies suffer from challenges arising from the timing of data collection , research biases like recall bias , and how variables are selected. These lead to low internal validity and the inability to determine causality.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 24, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/retrospective-cohort-study/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a case-control study | definition & examples, what is an observational study | guide & examples, what is recall bias | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Webinars

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

A How-To Guide for Conducting Retrospective Analyses: Example COVID-19 Study

In the urgent setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, treatment hypotheses abound, each of which requires careful evaluation. A randomized controlled trial generally provides the strongest possible evaluation of a treatment, but the efficiency and effectiveness of the trial depend on the existing evidence supporting the treatment. The researcher must therefore compile a body of evidence justifying the use of time and resources to further investigate a treatment hypothesis in a trial. An observational study can help provide this evidence, but the lack of randomized exposure and the researcher’s inability to control treatment administration and data collection introduce significant challenges for non-experimental studies. A proper analysis of observational health care data thus requires an extensive background in a diverse set of topics ranging from epidemiology and causal analysis to relevant medical specialties and data sources. Here we provide 10 rules that serve as an end-to-end introduction to retrospective analyses of observational health care data. A running example of a COVID-19 study presents a practical implementation of each rule in the context of a specific treatment hypothesis. When carefully designed and properly executed, a retrospective analysis framed around these rules will inform the decisions of whether and how to investigate a treatment hypothesis in a randomized controlled trial.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Class of 2024 Candidates

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Dean’s Remarks

- Keynote Address

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Marketing

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2024 Awardees

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- Career Change

- Career Advancement

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

The Case-Control Study : A Practical Review for the Clinician

From the Department of Pediatrics, University of Virginia Medical Center, Charlottesville (Dr Hayden), the Department of Pediatrics and Epidemiology, McGill University, Montreal (Dr Kramer), and the Department of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn (Dr Horwitz).

The retrospective case-control study is an important research strategy commonly encountered in the medical literature. A thoughtfully designed, carefully executed case-control study can be an invaluable source of clinical information, and physicians must often base important decisions about patient counseling and management on their interpretation of such studies. Unfortunately, the retrospective direction of case-control studies—looking "backwards" from an outcome event to an antecedent exposure—is accompanied by numerous methodological hazards. Careful attention must be paid to selection of appropriate study groups; definition and detection of the outcome event; definition and ascertainment of the exposure; assurance that the compared groups were equally susceptible to the outcome event at baseline; and careful statistical analysis. If systematic bias enters the research at any of these points, erroneous conclusions can result. Greater familiarity with the case-control method should enable clinicians to be more critically insightful when interpreting the results of published studies using this design format.

( JAMA 1982;247:326-331)

Hayden GF , Kramer MS , Horwitz RI. The Case-Control Study : A Practical Review for the Clinician . JAMA. 1982;247(3):326–331. doi:10.1001/jama.1982.03320280046028

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Retrospective Studies and Chart Reviews

Chris nickson.

- Nov 3, 2020

- Retrospective studies are designed to analyse pre-existing data, and are subject to numerous biases as a result

- Retrospective studies may be based on chart reviews (data collection from the medical records of patients)

- case series

- retrospective cohort studies (current or historical cohorts)

- case-control studies

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS USED IN RETROSPECTIVE STUDIES

- Compare outcomes between treatment and control group

- Used if treatment and control group are selected by a chance mechanism

- Divide all patients into subgroups according to a risk factor, then perform comparison within these subgroups

- Used if only one key confounding variable exists

- Find pairs of patients that have specific characteristics in common, but received different treatments; compares outcome only in these pairs

- Used if only a few confounders exist and if the size of one of the comparison groups is much larger than the other

- More than one confounder is controlled simultaneously, if a larger number of confounders needs to be adjusted for computer software and statistical advice is necessary

- Used if sample size is large

- Simple description of data

- Used if sample size is low and other options failed

ADVANTAGES OF RETROSPECTIVE STUDIES

- quicker, cheaper and easier than prospective cohort studies

- can address rare diseases and identify potential risk factors (e.g. case-control studies)

- not prone to loss of follow up

- may be used as the initial study generating hypotheses to be studied further by larger, more expensive prospective studies

DISADVANTAGES OF RETROSPECTIVE STUDIES

- inferior level of evidence compared with prospective studies

- controls are often recruited by convenience sampling, and are thus not representative of the general population and prone to selection bias

- prone to recall bias or misclassification bias

- subject to confounding (other risk factors may be present that were not measured)

- cannot determine causation, only association

- some key statistics cannot be measured

- temporal relationships are often difficult to assess

- retrospective cohort studies need large sample sizes if outcomes are rare

SOURCES OF ERROR IN CHART REVIEWS AND THEIR SOLUTIONS

From Kaji et al (2014) and Gilbert et al (1996):

- establish whether necessary information is available in the charts

- establish if there are sufficient charts to perform the analysis with adequate precision

- perform a sample size calculation

- Declare any conflict of interest Provide evidence of institutional review board approval

- Submit the data collection form, as well as the coding rules and definitions, as an online appendix

- Case selection or exclusion using explicit protocols and well described the criteria

- Ensure all available charts have an equal chance of selection

- Provide a flow diagram showing how the study sample was derive from the source population

- define the predictor and outcome variables to be collected a priori

- Develop a coding manual and publish as an online appendix

- Use standardized abstraction forms to guide data collection

- Provide precise definitions of variables

- Pilot test the abstraction form

- Ensure uniform handling of data that is conflicting, ambiguous, missing, or unknown

- Perform a sensitivity analysis if needed

- Blind chart reviewers to the etiologic relation being studied or the hypotheses being tested. If groups of patients are to be compared, the abstractor should be blinded to the patient’s group assignment

- Describe how blinding was maintained in the article

- Train chart abstractors to perform their jobs.

- Describe the qualifications and training of the chart abstracters.

- Ideally, train abstractors before the study starts, using a set of “practice” medical records.

- Ensure uniform training, especially in multi-center studies

- Monitor the performance of the chart abstractors

- Hold periodic meetings with chart abstractors and study coordinators to resolve disputes and review coding rules.

- A second reviewer should re-abstract a sample of charts, blinded to the information obtained by the first correlation reviewer.

- Report a kappa-statistic, intraclass coefficient, or other measure of agreement to assess inter-rater reliability of the data

- Provide justification for the criteria for each variable

SOURCES OF ERROR FROM THE USE OF ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORDS

Potential biases introduced from:

- use of boilerplates (a unit of writing that can be reused over and over without change)

- items copied and pasted

- default tick boxes

- delays in time stamps relative to actual care

References and Links

- CCC — Case-control studies

Journal articles

- Gilbert EH, Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, Barta DC, Steiner J. Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: Where are the methods? Ann Emerg Med. 1996 Mar;27(3):305-8. PMID: 8599488 .

- Kaji AH, Schriger D, Green S. Looking through the retrospectoscope: reducing bias in emergency medicine chart review studies. Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Sep;64(3):292-8. PMID: 24746846 .

- Sauerland S, Lefering R, Neugebauer EA. Retrospective clinical studies in surgery: potentials and pitfalls. J Hand Surg Br. 2002 Apr;27(2):117-21. PMID: 12027483 .

- Worster A, Bledsoe RD, Cleve P, Fernandes CM, Upadhye S, Eva K. Reassessing the methods of medical record review studies in emergency medicine research. Ann Emerg Med. 2005 Apr;45(4):448-51. PMID: 15795729 .

Critical Care

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at the Alfred ICU in Melbourne. He is also a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University . He is a co-founder of the Australia and New Zealand Clinician Educator Network (ANZCEN) and is the Lead for the ANZCEN Clinician Educator Incubator programme. He is on the Board of Directors for the Intensive Care Foundation and is a First Part Examiner for the College of Intensive Care Medicine . He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives.

After finishing his medical degree at the University of Auckland, he continued post-graduate training in New Zealand as well as Australia’s Northern Territory, Perth and Melbourne. He has completed fellowship training in both intensive care medicine and emergency medicine, as well as post-graduate training in biochemistry, clinical toxicology, clinical epidemiology, and health professional education.

He is actively involved in in using translational simulation to improve patient care and the design of processes and systems at Alfred Health. He coordinates the Alfred ICU’s education and simulation programmes and runs the unit’s education website, INTENSIVE . He created the ‘Critically Ill Airway’ course and teaches on numerous courses around the world. He is one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) and is co-creator of litfl.com , the RAGE podcast , the Resuscitology course, and the SMACC conference.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Twitter, he is @precordialthump .

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Posted on 6th December 2017 by Saul Crandon

Introduction

Case-control and cohort studies are observational studies that lie near the middle of the hierarchy of evidence . These types of studies, along with randomised controlled trials, constitute analytical studies, whereas case reports and case series define descriptive studies (1). Although these studies are not ranked as highly as randomised controlled trials, they can provide strong evidence if designed appropriately.

Case-control studies

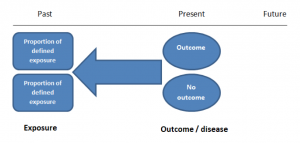

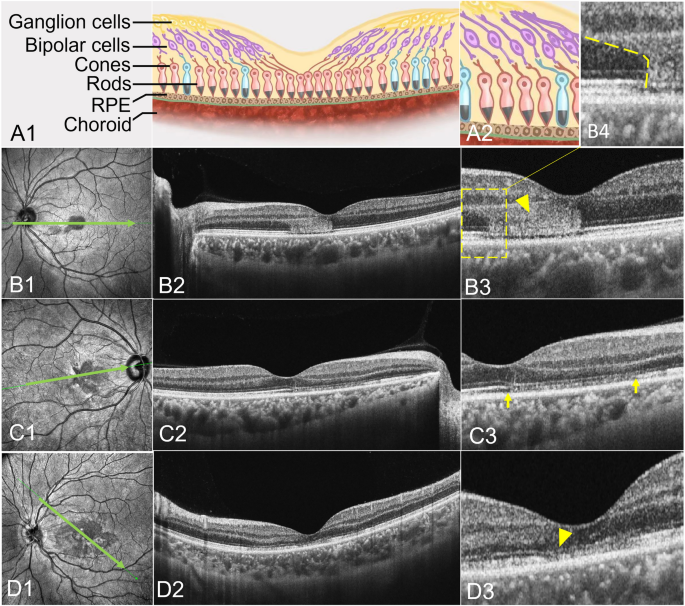

Case-control studies are retrospective. They clearly define two groups at the start: one with the outcome/disease and one without the outcome/disease. They look back to assess whether there is a statistically significant difference in the rates of exposure to a defined risk factor between the groups. See Figure 1 for a pictorial representation of a case-control study design. This can suggest associations between the risk factor and development of the disease in question, although no definitive causality can be drawn. The main outcome measure in case-control studies is odds ratio (OR) .

Figure 1. Case-control study design.

Cases should be selected based on objective inclusion and exclusion criteria from a reliable source such as a disease registry. An inherent issue with selecting cases is that a certain proportion of those with the disease would not have a formal diagnosis, may not present for medical care, may be misdiagnosed or may have died before getting a diagnosis. Regardless of how the cases are selected, they should be representative of the broader disease population that you are investigating to ensure generalisability.

Case-control studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their outcome / disease status.

As such, controls should also be selected carefully. It is possible to match controls to the cases selected on the basis of various factors (e.g. age, sex) to ensure these do not confound the study results. It may even increase statistical power and study precision by choosing up to three or four controls per case (2).

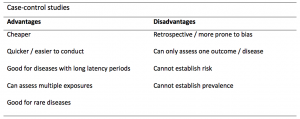

Case-controls can provide fast results and they are cheaper to perform than most other studies. The fact that the analysis is retrospective, allows rare diseases or diseases with long latency periods to be investigated. Furthermore, you can assess multiple exposures to get a better understanding of possible risk factors for the defined outcome / disease.

Nevertheless, as case-controls are retrospective, they are more prone to bias. One of the main examples is recall bias. Often case-control studies require the participants to self-report their exposure to a certain factor. Recall bias is the systematic difference in how the two groups may recall past events e.g. in a study investigating stillbirth, a mother who experienced this may recall the possible contributing factors a lot more vividly than a mother who had a healthy birth.

A summary of the pros and cons of case-control studies are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies.

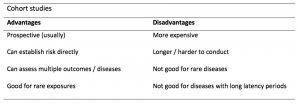

Cohort studies

Cohort studies can be retrospective or prospective. Retrospective cohort studies are NOT the same as case-control studies.

In retrospective cohort studies, the exposure and outcomes have already happened. They are usually conducted on data that already exists (from prospective studies) and the exposures are defined before looking at the existing outcome data to see whether exposure to a risk factor is associated with a statistically significant difference in the outcome development rate.

Prospective cohort studies are more common. People are recruited into cohort studies regardless of their exposure or outcome status. This is one of their important strengths. People are often recruited because of their geographical area or occupation, for example, and researchers can then measure and analyse a range of exposures and outcomes.

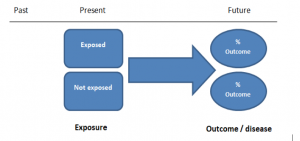

The study then follows these participants for a defined period to assess the proportion that develop the outcome/disease of interest. See Figure 2 for a pictorial representation of a cohort study design. Therefore, cohort studies are good for assessing prognosis, risk factors and harm. The outcome measure in cohort studies is usually a risk ratio / relative risk (RR).

Figure 2. Cohort study design.

Cohort studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their exposure status.

As a result, both exposed and unexposed groups should be recruited from the same source population. Another important consideration is attrition. If a significant number of participants are not followed up (lost, death, dropped out) then this may impact the validity of the study. Not only does it decrease the study’s power, but there may be attrition bias – a significant difference between the groups of those that did not complete the study.

Cohort studies can assess a range of outcomes allowing an exposure to be rigorously assessed for its impact in developing disease. Additionally, they are good for rare exposures, e.g. contact with a chemical radiation blast.

Whilst cohort studies are useful, they can be expensive and time-consuming, especially if a long follow-up period is chosen or the disease itself is rare or has a long latency.

A summary of the pros and cons of cohort studies are provided in Table 2.

The Strengthening of Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE)

STROBE provides a checklist of important steps for conducting these types of studies, as well as acting as best-practice reporting guidelines (3). Both case-control and cohort studies are observational, with varying advantages and disadvantages. However, the most important factor to the quality of evidence these studies provide, is their methodological quality.

- Song, J. and Chung, K. Observational Studies: Cohort and Case-Control Studies . Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.  2010 Dec;126(6):2234-2242.

- Ury HK. Efficiency of case-control studies with multiple controls per case: Continuous or dichotomous data . Biometrics . 1975 Sep;31(3):643–649.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.  Lancet 2007 Oct;370(9596):1453-14577. PMID: 18064739.

Saul Crandon

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Very well presented, excellent clarifications. Has put me right back into class, literally!

Very clear and informative! Thank you.

very informative article.

Thank you for the easy to understand blog in cohort studies. I want to follow a group of people with and without a disease to see what health outcomes occurs to them in future such as hospitalisations, diagnoses, procedures etc, as I have many health outcomes to consider, my questions is how to make sure these outcomes has not occurred before the “exposure disease”. As, in cohort studies we are looking at incidence (new) cases, so if an outcome have occurred before the exposure, I can leave them out of the analysis. But because I am not looking at a single outcome which can be checked easily and if happened before exposure can be left out. I have EHR data, so all the exposure and outcome have occurred. my aim is to check the rates of different health outcomes between the exposed)dementia) and unexposed(non-dementia) individuals.

Very helpful information

Thanks for making this subject student friendly and easier to understand. A great help.

Thanks a lot. It really helped me to understand the topic. I am taking epidemiology class this winter, and your paper really saved me.

Happy new year.

Wow its amazing n simple way of briefing ,which i was enjoyed to learn this.its very easy n quick to pick ideas .. Thanks n stay connected

Saul you absolute melt! Really good work man

am a student of public health. This information is simple and well presented to the point. Thank you so much.

very helpful information provided here

really thanks for wonderful information because i doing my bachelor degree research by survival model

Quite informative thank you so much for the info please continue posting. An mph student with Africa university Zimbabwe.

Thank you this was so helpful amazing

Apreciated the information provided above.

So clear and perfect. The language is simple and superb.I am recommending this to all budding epidemiology students. Thanks a lot.

Great to hear, thank you AJ!

I have recently completed an investigational study where evidence of phlebitis was determined in a control cohort by data mining from electronic medical records. We then introduced an intervention in an attempt to reduce incidence of phlebitis in a second cohort. Again, results were determined by data mining. This was an expedited study, so there subjects were enrolled in a specific cohort based on date(s) of the drug infused. How do I define this study? Thanks so much.

thanks for the information and knowledge about observational studies. am a masters student in public health/epidemilogy of the faculty of medicines and pharmaceutical sciences , University of Dschang. this information is very explicit and straight to the point

Very much helpful

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Cluster Randomized Trials: Concepts

This blog summarizes the concepts of cluster randomization, and the logistical and statistical considerations while designing a cluster randomized controlled trial.

Expertise-based Randomized Controlled Trials

This blog summarizes the concepts of Expertise-based randomized controlled trials with a focus on the advantages and challenges associated with this type of study.

An introduction to different types of study design

Conducting successful research requires choosing the appropriate study design. This article describes the most common types of designs conducted by researchers.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Critical Analysis of Retrospective Study Designs: Cohort and Case Series

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Orthopedics, Division of Foot and Ankle Surgery, West Penn Hospital, 4800 Friendship Avenue, N1, Pittsburgh, PA 15224, USA.

- 2 Department of Orthopedics, West Penn Hospital Foot & Ankle Surgery, Allegheny Health Network, 4800 Friendship Avenue, N1, Pittsburgh, PA 15224, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 3 Department of Orthopedics, West Penn Hospital Foot & Ankle Surgery, Allegheny Health Network, 4800 Friendship Avenue, N1, Pittsburgh, PA 15224, USA.

- PMID: 38388124

- DOI: 10.1016/j.cpm.2023.09.002

Retrospective studies represent an often used research methodology in the podiatric scientific literature, with cohort studies and case series being two of the most prevalent designs. Choosing a retrospective method is often dependent on multiple factors, two of the most important being details of the research question to be explored and the sample size that can be acquired. When analyzing literature, a reader must understand how retrospective studies work to critically examine the methods, results, and discussions to determine if the conclusion is reasonable and might be applied to clinical practice.

Keywords: Case series; Cohort study; Retrospective study.

Copyright © 2023 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Disclosure The authors have no financial disclosures.

Similar articles

- Study Designs in Clinical Research. Mendoza AE, Yeh DD. Mendoza AE, et al. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2021 Aug;22(6):640-645. doi: 10.1089/sur.2020.469. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2021. PMID: 34270360

- Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, Stephenson M, Aromataris E. Munn Z, et al. JBI Evid Synth. 2020 Oct;18(10):2127-2133. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099. JBI Evid Synth. 2020. PMID: 33038125

- The future of Cochrane Neonatal. Soll RF, Ovelman C, McGuire W. Soll RF, et al. Early Hum Dev. 2020 Nov;150:105191. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105191. Epub 2020 Sep 12. Early Hum Dev. 2020. PMID: 33036834

- Observational designs in clinical multiple sclerosis research: Particulars, practices and potentialities. Jongen PJ. Jongen PJ. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019 Oct;35:142-149. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.07.006. Epub 2019 Jul 20. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019. PMID: 31394404 Review.

- Study designs in dermatology: Practical applications of study designs and their statistics in dermatology. Silverberg JI. Silverberg JI. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Nov;73(5):733-40; quiz 741-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.062. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015. PMID: 26475533 Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- W.B. Saunders

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Get Started

- Determine Protocol Type

- Not Human Subjects Research and Not Research

Case Study Types

Is my case study considered human subjects research, retrospective case study review/report.

- Generally completed by a retrospective review of medical records that highlights a unique treatment, case, or outcome

- Often clinical in nature

- A report about five or fewer clinical experiences or observations identified during clinical care

- Does not involve biospecimens or FDA-regulated products (e.g., drugs, devices, biologics) that have not been approved for use in humans

- Does not include articles requiring exemption from FDA oversight

- Does not include articles under an IND/IDE

Prospective Single Subject Case Study Review/Report

- Often social/behavioral in nature

- In-depth prospective analysis and report involving unique or exceptional observations or experiences about one, or a few, individual human subjects

- Is intended to contribute to generalizable knowledge

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

Guide to retrospective case study data reports

Section 1 – what is being analyzed.

- Case Studies Home

- Raton Basin, Colorado

- Killdeer, North Dakota

- Northeastern Pennsylvania

- Southwestern Pennsylvania

- Wise County, Texas

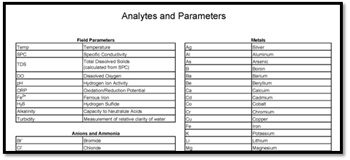

For each case study site, EPA researchers took samples from a variety of sources and tested them for a broad range of substances and chemicals, including components of hydraulic fracturing fluids. Water conditions, such as temperature and dissolved oxygen referred to as “parameters” were also monitored and recorded. These are listed in the first table labeled, “Analytes and Parameters.” (Analytes tab)

Although each case study site has different geology and hydrology, EPA generally uses the same water quality test methods for all the sites to assess conditions in the area.

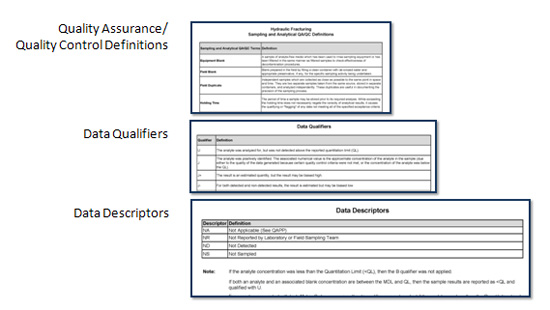

Section 2 – Understanding the Data

Many of the data have notes and labels that represent important descriptions for understanding what the values listed mean. All of the possible data notes and abbreviations are listed in the following reference tables:

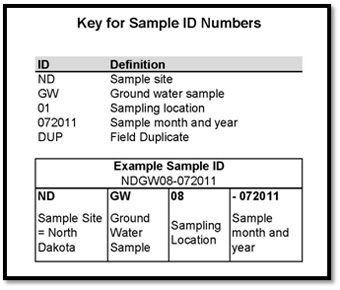

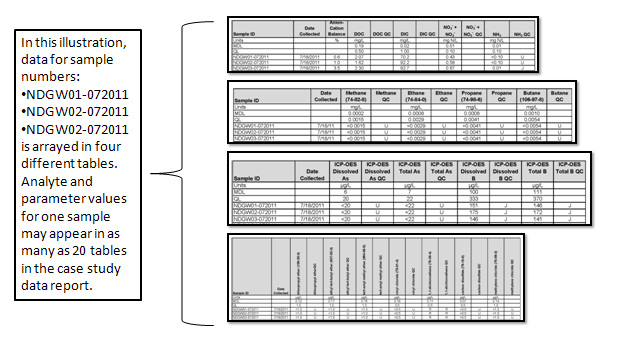

Section 3 – Key for Sample ID Numbers

Each sample taken has a unique identification number. The Key explains the numbering system for the samples.

Section 4 – Data Tables

Data for the samples are grouped together in tables for Parameters, Metals, Volatile Organic Compounds, etc. The sample ID’s will appear in more than one table depending on the analytes included in each table.

- Hydraulic Fracturing Study Home

- Final Assessment

- EPA Published Research

- Fact Sheets

- Questions & Answers about the Final Assessment

- EPA Hydraulic Fracturing - Agency Main Page

- Open access

- Published: 27 June 2024

Chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity and its symptoms in patients with breast cancer: a scoping review

- Hyunjoo Kim 1 , 2 ,

- Bomi Hong 3 ,

- Sanghee Kim 4 ,

- Seok-Min Kang 5 &

- Jeongok Park ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4978-817X 4

Systematic Reviews volume 13 , Article number: 167 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity is a significant concern because it is a major cause of morbidity. This study aimed to provide in-depth information on the symptoms of chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity (CRCT) by exploring literature that concurrently reports the types and symptoms of CRCT in patients with breast cancer.

A scoping review was performed according to an a priori protocol using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s guidelines. The participants were patients with breast cancer. The concept was the literature of specifically reported symptoms directly matched with CRCT and the literature, in English, from 2010, and the context was open. The search strategy included four keywords: “breast cancer,” “chemotherapy,” “cardiotoxicity,” and “symptoms.” All types of research designs were included; however, studies involving patients with other cancer types, animal subjects, and symptoms not directly related to CRCT were excluded. Data were extracted and presented including tables and figures.

A total of 29 articles were included in the study, consisting of 23 case reports, 4 retrospective studies, and 2 prospective studies. There were no restrictions on the participants’ sex; however, all of them were women, except for one case report. The most used chemotherapy regimens were trastuzumab, capecitabine, and doxorubicin or epirubicin. The primary CRCT identified were myocardial dysfunction and heart failure, followed by coronary artery disease, pulmonary hypertension, and other conditions. Major tests used to diagnose CRCT include echocardiography, electrocardiography, serum cardiac enzymes, coronary angiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. In all case reports, CRCT was diagnosed through an incidental checkup according to the patient’s symptom presentation; however, only 10 of these studies showed a baseline checkup before chemotherapy. The five most common CRCT symptoms were dyspnea, chest pain, peripheral edema, fatigue, and palpitations, which were assessed by patient-reported symptom presentation rather than using a symptom assessment tool. Dyspnea with trastuzumab treatment and chest pain with capecitabine treatment were particularly characteristic. The time for first symptom onset after chemotherapy ranged from 1 hour to 300 days, with anthracycline-based regimens requiring 3–55 days, trastuzumab requiring 60–300 days, and capecitabine requiring 1–7 days.

Conclusions

This scoping review allowed data mapping according to the study design and chemotherapy regimens. Cardiac assessments for CRCT diagnosis were performed according to the patient’s symptoms. There were approximately five types of typical CRCT symptoms, and the timing of symptom occurrence varied. Therefore, developing and applying a CRCT-specific and user-friendly symptom assessment tool are expected to help healthcare providers and patients manage CRCT symptoms effectively.

Peer Review reports

Breast cancer is currently the most common cancer worldwide. Its incidence and mortality rates in East Asia in 2020 accounted for 24% and 20% of the global rates, respectively, and these rates are expected to continue increasing until 2040 [ 1 ]. In the USA, since the mid-2000s, the incidence rate of breast cancer has been increasing by 0.5% annually, while the mortality rate has been decreasing by 1% per year from 2011 to 2020 [ 2 ]. Despite the improved long-term survival rate in patients with breast cancer due to the development of chemotherapy, the literature has highlighted that cardiotoxicity, a cardiac problem caused by chemotherapy, could be a significant cause of death among these patients [ 3 ]. Chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity (CRCT) can interfere with cancer treatment and progress to congestive heart failure during or after chemotherapy [ 4 ], potentially lowering the survival rate and quality of life of patients with cancer [ 5 ].

The term cardiotoxicity was first used in the 1970s to describe cardiac complications resulting from chemotherapy regimens, such as anthracyclines and 5-fluorouracil. The early definition of cardiotoxicity centered around heart failure, but the current definition is broad and still imprecise [ 6 ]. The 2022 guidelines on cardio-oncology from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) define cardiotoxicity as including cardiac dysfunction, myocarditis, vascular toxicity, arterial hypertension, and cardiac arrhythmias. Some of these definitions reflect the symptoms. For example, cardiac dysfunction, which accounts for 48% of cardiotoxicity in patients with cancer, is divided into asymptomatic and symptomatic cardiac dysfunction. Asymptomatic cardiac dysfunction is defined based on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), myocardial global longitudinal strain, and cardiac biomarkers. Symptomatic cardiac dysfunction indicates heart failure and presents with ankle swelling, breathlessness, and fatigue [ 7 ]. The ESC guidelines for heart failure present more than 20 types of symptoms [ 8 ]; however, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have been conducted to determine which heart failure symptoms and their characteristics are associated with CRCT in patients with breast cancer. Similarly, there is a lack of information related to vascular toxicity such as myocardial infarction [ 7 ].

Professional societies in cardiology and oncology have proposed guidelines for the prevention and management of cardiotoxicity in patients with cancer. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the ESC, it is recommended to identify high-risk patients, comprehensively evaluate clinical signs and symptoms associated with CRCT, and conduct cardiac evaluations before, during, and after chemotherapy [ 7 , 9 , 10 ]. In addition, guidelines for patients with cancer, including those for breast cancer survivorship care, emphasize that patients should be aware of the potential risk of CRCT and report symptoms, such as fatigue or shortness of breath to their healthcare providers [ 7 , 11 , 12 ]. Although these guidelines encompass cardiac monitoring as well as symptom observation, many studies have focused solely on objective diagnostic tests, such as echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and cardiac biomarkers [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ], which means that there is little interest in CRCT symptoms in patients under breast cancer care.

This lack of interest in CRCT symptoms may be related to the absence of a specific symptom assessment tool for CRCT. Symptom monitoring of CRCT in patients with breast cancer was conducted through patient interviews and reported using the appropriate terminology [ 23 ]. In terms of interviews, patients with cancer experienced the burden of expressing symptoms between cardiovascular problems and cancer treatment. Qualitative research on patients with cancer indicates that these patients experience a daily battle to distinguish the symptoms they experience during chemotherapy [ 24 ]. To reduce the burden of identifying CRCT symptoms, it is crucial to educate patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy about these symptoms. To report cardiotoxicity, healthcare providers in oncology can use a dictionary of terms called the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) for reporting adverse events in patients with cancer [ 25 ]. Patients can also use Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO), which allows unfiltered reporting of symptoms directly to the clinical database [ 26 ]. PRO consists of 78 symptomatic adverse events out of approximately 1,000 types of CTCAE [ 27 ]. Basch et al. suggested that PRO could enable healthcare providers to identify patient symptoms before they worsen, thereby improving the overall survival rate of patients with metastatic cancer [ 28 ]. This finding implies that symptoms can provide valuable clues for enhancing the timeliness and accuracy of clinical assessments of CRCT [ 29 ]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the scope of research focusing on CRCT symptoms for prevention and early detection of CRCT in patients with breast cancer. The detailed research questions are as follows:

What are the general characteristics of the studies related to CRCT in patients with breast cancer?

What diagnostic tools and monitoring practices are used to detect CRCT?

What are the characteristics and progression of symptoms associated with CRCT?

A scoping review is a research method for synthesizing evidence that involves mapping the scope of evidence on a particular topic [ 30 ]. It aims to clarify key concepts and definitions, identify key characteristics of factors related to a concept, and highlight gaps or areas for further research [ 30 ]. This study used a scoping review methodology based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) framework. The JBI methodology, refined from the framework initially developed by Arksey and O’Malley [ 31 ], involves developing a research question, establishing detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria, and selecting and analyzing literature accordingly [ 32 ]. In contrast to systematic reviews, scoping reviews can encompass a variety of study designs and are particularly suitable when the topic has not been extensively studied [ 33 ]; hence, the decision was made to conduct a scoping review.

Development of a scoping review protocol

To conduct this review, an a priori scoping review protocol was developed to enhance transparency and increase the usefulness and reliability of the results. The protocol included the title, objective, review questions, introduction, eligibility criteria, participants, concept, context, types of evidence source, methods, search strategy, source of evidence selection, data extraction, data analysis and presentation, and deviation from the protocol [ 34 ] (Supplementary File 1).

Eligibility criteria

A participant-concept-context (PCC) framework was constructed based on the following research criteria. The participants were patients with breast cancer. The concept was that studies that specifically reported symptoms directly matched to CRCT in patients with breast cancer and the literature, published in English since 2010, in line with the year the CRCT guidelines were announced by the Cardio-Oncology Society. The context was open. We included all types of research designs. The exclusion criteria were studies that included patients with other types of cancer, involved animal subjects, and reported symptoms not directly related to CRCT.

Search strategy

The keywords consisted of “breast cancer,” “chemotherapy,” “cardiotoxicity,” and “symptoms.” The keywords for “cardiotoxicity” were constructed according to the clinical cardiotoxicity report and ESC guidelines [ 7 , 35 ]. The keywords for “symptoms” included 40 specific symptoms of arrhythmia, heart failure, and cardiac problems [ 36 , 37 ] (Supplementary Table 1). We used PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL.

Source of evidence selection

Duplicate studies were removed using EndNote 21. The titles and abstracts were then reviewed according to the inclusion criteria, the primary literature was selected, and the final literature was selected through a full-text review. Any disagreements were resolved through discussions between the investigators.

Data extraction

The data from the literature included the general characteristics of the study, as well as information on the patients, chemotherapy, cardiotoxicity, and symptoms. The general characteristics of the study included author, publication year, country of origin, study design; patient information including sample size, sex, age, cancer type, and cancer stage; chemotherapy information including chemotherapy regimen; cardiotoxicity information including type of cardiotoxicity, diagnostic tests, and times of assessment; and symptom information including type of symptom, characteristics of symptom worsening or improvement, onset time, progression time, and time to symptom improvement. Information on whether to receive chemotherapy after the diagnosis of cardiotoxicity was explored.

Data analysis and presentation

The contents of the included studies were divided into three categories: (1) general characteristics, which encompassed study designs, patients, and medications; (2) type of CRCT and cardiac assessment for CRCT; and (3) characteristics and progression of the symptoms associated with CRCT. CRCT symptom-related data are presented in tables and figures.

In total, 487 studies were identified through database searches, and 116 duplicates were subsequently removed. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, we excluded 197 studies in which participants had cancers other than breast cancer, no symptoms, or symptom-related expressions. Of the remaining 174 studies, 146 were excluded after full-text review. Among the excluded studies, 79 were mainly clinical trials that the symptoms were not directly related to CRCT, 62 did not report specific symptoms, four were in the wrong population, and one was unavailable for full-text review. An additional study was included after a review of references, bringing the final count to 29 studies included in the analysis (Fig. 1 ).

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews flowchart

General characteristics of studies including designs, sex and age, chemotherapy regimen, and CRCT criteria

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the studies included in this review. The majority of these studies were published in the USA ( n =14), with Japan ( n =3), and Romania ( n =2) following. The study designs primarily consisted of case reports ( n =23), retrospective studies ( n =4), and prospective studies ( n =2).