If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 7

- Introduction to the age of empire

- The age of empire

The Spanish-American War

- Imperialism

- The Progressives

- The Progressive Era

- The presidency of Theodore Roosevelt

- Progressivism

- The Cuban movement for independence from Spain in 1895 garnered considerable American support. When the USS Maine sank, the United States believed the tragedy was the result of Spanish sabotage and declared war on Spain.

- The Spanish-American War lasted only six weeks and resulted in a decisive victory for the United States. Future US president Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt rose to national prominence due to his role in the conflict.

- Although the United States promised it would not annex Cuba after victory, it did require Cuba to permit significant American intervention in Cuban affairs.

- As a result of the war, the United States acquired Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines as territories.

The conflict between empire and democracy

Trouble in cuba, a splendid little war, consequences of the spanish-american war, what do you think.

- On American imperialism at the turn of the twentieth century, see George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 299-377.

- For more on the relationship between empire and democracy, see Richard H. Immerman, Empire for Liberty: A History of American Imperialism from Benjamin Franklin to Paul Wolfowitz (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- For more on yellow journalism, see W. Joseph Campbell, The Year that Defined American Journalism: 1897 and the Clash of Paradigms (New York: Routledge, 2006).

- See Edward J. Marolda, ed. Theodore Roosevelt, the US Navy and the Spanish-American War (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001).

- On the Spanish fleet compared to the American fleet, see " The Philippines ," Digital History, 2016.

- See Frank N. Schubert, Black Valor: Buffalo Soldiers and the Medal of Valor, 1870-1898 (New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 1997), 133-173.

- Hay quoted in Walter Mills, The Martial Spirit (New York: Arno Press, 1979), 340; on deaths from disease see The American Pageant: A History of the American People , 15th (AP) edition (Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2013), 616.

- On the Platt Amendment, see Louis A. Perez, Jr., Cuba Under the Platt Amendment, 1902-1934 (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1986).

- Taft quoted in Kennedy and Cohen, The American Pageant , 623.

- For more on the war in the Philippines, see David J. Silbey, A War of Frontier and Empire: The Philippine-American War, 1899-1902 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007).

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Spanish American War

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 2, 2022 | Original: May 14, 2010

The Spanish-American War was an 1898 conflict between the United States and Spain that ended Spanish colonial rule in the Americas and resulted in U.S. acquisition of territories in the western Pacific and Latin America.

Causes: Remember the Maine!

The war originated in the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain, which began in February 1895.

Spain’s brutally repressive measures to halt the rebellion were graphically portrayed for the U.S. public by several sensational newspapers engaging in yellow journalism , and American sympathy for the Cuban rebels rose.

Did you know? The term yellow journalism was coined in the 19th century to describe journalism that relies on eye-catching headlines, exaggeration and sensationalism to increase sales.

The growing popular demand for U.S. intervention became an insistent chorus after the still-unexplained sinking in Havana harbor of the American battleship USS Maine , which had been sent to protect U.S. citizens and property after anti-Spanish rioting in Havana.

War Is Declared

Spain announced an armistice on April 9 and speeded up its new program to grant Cuba limited powers of self-government.

But the U.S. Congress soon afterward issued resolutions that declared Cuba’s right to independence, demanded the withdrawal of Spain’s armed forces from the island, and authorized the use of force by President William McKinley to secure that withdrawal while renouncing any U.S. design for annexing Cuba.

Spain declared war on the United States on April 24, followed by a U.S. declaration of war on the 25th, which was made retroactive to April 21.

Spanish American War Begins

The ensuing war was pathetically one-sided, since Spain had readied neither its army nor its navy for a distant war with the formidable power of the United States.

In the early morning hours of May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey led a U.S. naval squadron into Manila Bay in the Philippines. He destroyed the anchored Spanish fleet in two hours before pausing the Battle of Manila Bay to order his crew a second breakfast. In total, fewer than 10 American seamen were lost, while Spanish losses were estimated at over 370. Manila itself was occupied by U.S. troops by August.

The elusive Spanish Caribbean fleet under Adm. Pascual Cervera was located in Santiago harbor in Cuba by U.S. reconnaissance. An army of regular troops and volunteers under Gen. William Shafter (including then-former assistant secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt and his 1st Volunteer Cavalry, the “Rough Riders”) landed on the coast east of Santiago and slowly advanced on the city in an effort to force Cervera’s fleet out of the harbor.

Cervera led his squadron out of Santiago on July 3 and tried to escape westward along the coast. In the ensuing battle all of his ships came under heavy fire from U.S. guns and were beached in a burning or sinking condition.

Santiago surrendered to Shafter on July 17, thus effectively ending the brief but momentous war.

Treaty of Paris

The Treaty of Paris ending the Spanish American War was signed on December 10, 1898. In it, Spain renounced all claim to Cuba, ceded Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States and transferred sovereignty over the Philippines to the United States for $20 million.

Philippine insurgents who had fought against Spanish rule soon turned their guns against their new occupiers. The Philippine-American War began in February of 1899 and lasted until 1902. Ten times more U.S. troops died suppressing revolts in the Philippines than in defeating Spain.

Impact of the Spanish-American War

The Spanish American War was an important turning point in the history of both antagonists. Spain’s defeat decisively turned the nation’s attention away from its overseas colonial adventures and inward upon its domestic needs, a process that led to both a cultural and a literary renaissance and two decades of much-needed economic development in Spain.

The victorious United States, on the other hand, emerged from the war a world power with far-flung overseas possessions and a new stake in international politics that would soon lead it to play a determining role in the affairs of Europe and the rest of the globe.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Spanish-American War

By Paul A. Kopacz

Although often regarded as a minor conflict, the Spanish-American War (1898) made a major impact on Greater Philadelphia. As a populous urban center, Philadelphia and its immediate environs contributed a substantial number of troops to the United States’ volunteer army but also provided an outlet for those dissenters who decried warfare. In addition, the war influenced the region’s economy by significantly boosting war-production manufacturing while also creating shortages that affected local industries and consumers. After the successful conclusion of hostilities, Philadelphia hosted a three-day victory festival that drew national attention, but debate continued over the United States’ acquisition of former Spanish territory. And over half a century later, one of the Spanish-American War’s most celebrated warships became a floating museum docked at Penn’s Landing.

The Spanish-American War propelled the victorious United States into the forefront of world affairs, allowed America to take a seat among leading military powers, and established the young nation as a fledgling empire. A unique combination of social, economic, and political pressures helped push the United States into open warfare against Spain, but officially, President William McKinley (1843-1901) asked Congress for the authority to commit American troops in order to liberate Cuba, and its people, from oppressive Spanish rule. Once war had been declared on April 25, 1898, the U.S. government began recruiting state National Guard regiments to create the foundation of a national army. Aroused by months of inflammatory newspaper articles that vividly depicted Spanish atrocities and Cuban suffering, and stimulated to patriotic heights by the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor, Philadelphia-area residents did not hesitate to enlist. Philadelphia contributed four regiments of volunteer infantry (the 1 st , 2 nd , 3 rd , and 6 th ), one battery of artillery (Light Battery A), and one troop of cavalry (First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry) for a total of 4,849 soldiers. Wilmington and northern Delaware sent almost three hundred men (Companies A, C, F, H, and K) into the Army. In New Jersey, Camden County opened a recruiting office to fill a proposed Sixth Regiment, but the war ended before the Sixth could be mustered into service. Of all these volunteers only Light Battery A and the First Troop City Cavalry deployed for service overseas, although an armistice was declared before they saw action. Sailors from the area, however, served aboard warships that engaged in combat in both Cuba and the Philippines.

Although local support for the war was pervasive, it was not unanimous. The Universal Peace Union, based in Philadelphia and led by Alfred H. Love (1830-1913), condemned armed conflict with Spain before and after hostilities began. Love went so far as to send a peace initiative to the Spanish Queen Regent, by a European courier, after the United States declared war. When this came to light, the Philadelphia Bulletin openly questioned his loyalty, inciting angry mobs to march on his home and burn his bullet-ridden effigy in Chester . Denounced as a traitor, he was even turned away by the prisoners of Eastern State Penitentiary , where he had counseled inmates every Sunday for the previous forty-two years. Meanwhile, the City Council, under political pressure, evicted the UPU from its office on Independence Square.

Munitions Surge

The war economy bestowed benefits but also imposed hardships. On the upside, military manufacturing provided employment for men, women, and even children still suffering from the Panic of 1893. E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company , attempting to supply the government’s insatiable need for gunpowder , aggressively expanded operations and hiring at its brown powder mill north of Wilmington and its smokeless powder plant in South Jersey. Camden shipbuilder John H. Dialogue and Son employed workers to build U.S. naval vessels. In Philadelphia extensive shipyards such as William Cramp & Sons and League Island Navy Yard , in addition to building large warships, added extra shifts to provide gunboats to patrol and protect coastal waterways. Workers at Midvale Steel and the Frankford Arsenal worked around the clock to produce naval artillery and small arms ammunition, while smaller companies and seamstresses working at home labored to provide American fighting men with apparel and accoutrements. Everything from uniforms and tents to buttons, blankets, caps, and summer drawers were stored or produced in the Schuylkill Arsenal.

While the war with Spain benefited some industries, the conflict in Cuba threatened to disrupt others. During the early months of 1898, as tensions increased between the United States and Spain, local cigar manufacturers, anticipating hostilities, imported as much tobacco from Cuba as they could, even purchasing supplies previously shipped to Europe. By the time war began, farsighted Philadelphia-area cigar makers had stockpiled enough Cuban tobacco to keep their workers rolling and their customers smoking for at least another year. Philadelphia sugar manufacturers faced a different dilemma. An ongoing two-year struggle between revolutionaries and Spanish authorities had already impeded Cuban sugar exports and forced desperate refinery owners to search the world for other sources of supply. When war between the United States and Spain began, raw sugar from such distant places as Java, the Philippines, Egypt, and Mauritius in the Indian Ocean made its way into Philadelphia ports. During the war, thousands of tons of beet sugar from Germany were also imported. These alternative sources of sugar enabled refineries in Philadelphia to continue operating.

These auxiliary supply strategies kept the cigar and sugar industries running but increased costs for consumers. Throughout the Philadelphia region, shortages caused by the war resulted in higher prices for food staples such as oatmeal, beans, meat, canned fruits and vegetables, potatoes, coffee, and tea. Flour became exceptionally dear and the price of bread skyrocketed. Prices rose so rapidly that distributors of flour became reluctant to sell large quantities because they expected that they might make a greater profit at a later date. Prices also increased and availability dropped for dry goods such as duck and dyed cotton, which were in great demand for Army use.

After suffering two crushing naval losses and with its armies on the brink of defeat, Spain accepted the futility of continuing the struggle and negotiated an armistice that began on August 12, 1898; a formal peace treaty followed four months later. Once hostilities concluded, the city of Philadelphia planned a Peace Jubilee to celebrate the nation’s victory over Spain. The focal point of the Philadelphia Peace Jubilee was the construction of a towering, electrically illuminated, Athenian arch that spanned Broad Street near Sansom, bisecting a Court of Honor of ornate columns lining Broad Street from City Hall to Walnut Street. The celebration commenced on October 25, 1898, with a grand naval pageant of boats on the Delaware River. Two days later twenty-five thousand soldiers, many from Philadelphia, marched down the Court of Honor under the respectful gaze of President William McKinley. The festivities concluded October 28 with a vast civic parade representing many of the city’s diverse ethnic, social, business, civil, and educational organizations. Spectators traveled from all over the United States to attend, and most major newspapers covered the occasion.

Questioning Imperialism

As in the rest of the United States, the aftermath of the Spanish-American War led some Philadelphia-area inhabitants to openly question their nation’s new role as an imperial power. After the war, American soldiers remained overseas to occupy Cuba and America’s new possessions: Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippine Islands. Generally, these occupations were temporary and peaceful, but in the Philippines U.S. troops combatted a fierce native insurgency for years. Staunch Filipino resistance compelled the Philadelphia American League (1899) to condemn imperialism as a violation of the republican principle of government by consent of the governed. Philadelphia African Americans also spoke out against American colonialism. Black newspapers such as the Philadelphia Defender , Odd Fellows Journal , and the Christian Banner sympathized with the plight of the Filipinos but remonstrated that the United States government should worry less about foreign entanglements and, instead, redress the lack of equality and civil rights endured at home by its own citizens of color.

The region later gained a visible monument to the Spanish-American War in the form of the USS Olympia , the flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron, which led a devastating attack on a Spanish fleet in Manila Bay that destroyed every enemy warship without the loss of a single American vessel. This stunning victory brought both Commodore George Dewey (1837-1917) and his flagship national recognition. The Olympia was eventually retired in 1922 to the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and in 1957 the Navy ceded the ship to the Cruiser Olympia Association, a nonprofit organization established to acquire Olympia artifacts and raise funds for the boat’s preservation. Docked at Penn’s Landing , the next year the ship opened to the public as a floating museum.

The Spanish-American War lasted little more than three and a half months, but its legacy lived on in the Philadelphia region for years. In many ways, the conflict with Spain served as a rudimentary rehearsal for America’s next war, World War I (1917-18). The martial spirit and patriotism displayed in 1898 revived and grew in 1917 as tens of thousands of local men answered the call to join the Army and Navy. The ethos of military production that powered the region’s economy during the Spanish American War intensified during the Great War, and area civilians endured even more severe privations. The Spanish-American War had prepared the region to proceed and persevere through the First World War.

Paul A. Kopacz is the recipient of a master’s degree in history from Villanova University . (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

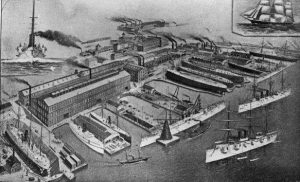

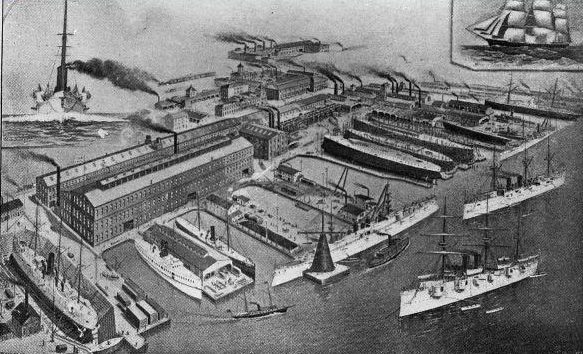

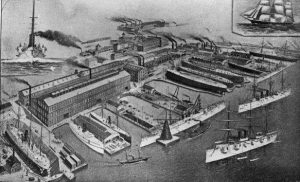

William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company

PhillyHistory.org

William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company shipyard was founded in 1830 and became a leader in U.S. iron ship building in the late nineteenth century. Located on the waterfront in the Fishtown neighborhood of Philadelphia, the shipyard became a major employer of Kensington and Fishtown residents. During the Spanish-American War, Cramp’s shipyard built the battleships Indiana and Massachusetts , as well as the armored cruiser the New York and the protected cruiser the Columbia . The USS Indiana , Massachusetts , and New York all fought in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

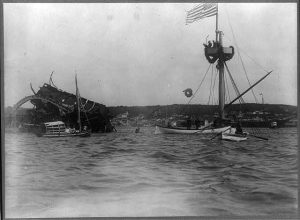

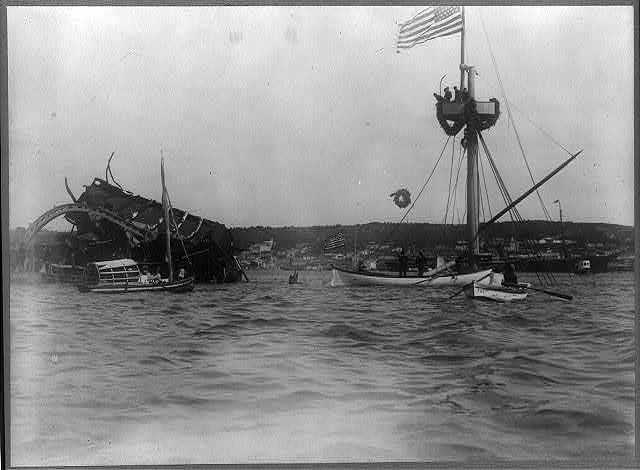

Destruction of the USS Maine , Havana Harbor, 1898

Library of Congress

A key event that led to the Spanish-American War was the explosion and sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor in 1898. The explosion killed 260 officers and men on board, and blame for the explosion was initially placed upon the Spanish. The aftermath of the explosion can be seen here, as the twisted remains of the Maine protruded above the water. This assumed attack on the United States motivated many Philadelphians to enlist in the war effort, contributing four regiments of volunteer infantry (the First, Second, Third, and Sixth), one battery of artillery (Light Battery A), and one troop of cavalry (First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry) for a total of 4,849 soldiers. Wilmington and northern Delaware sent almost three hundred men (Companies A, C, F, H, and K) into the army.

The actual cause of the explosion that sunk the USS Maine remains debated. Although President William McKinley’s administration deemed the explosion the result of an external explosion by a mine, later investigations suggest the possibility that the explosion occurred from an internal coal fire that spread to the artillery magazines.

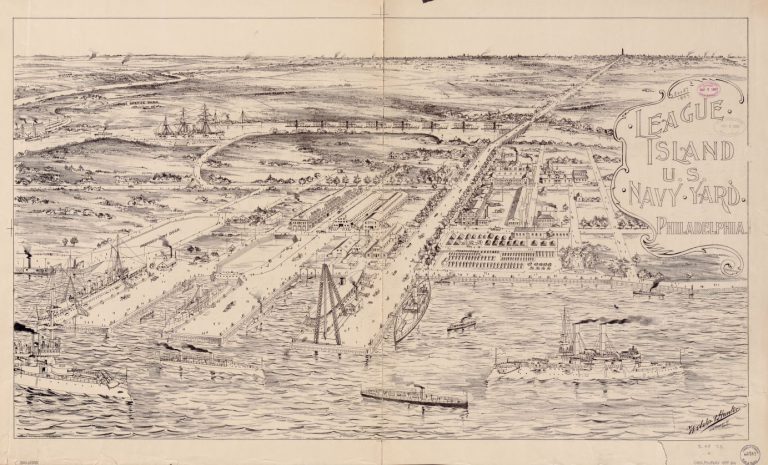

League Island Navy Yard

The United States Navy, which had been based in a yard on Front Street at the Delaware River since 1776, sought land for a new navy yard in the 1860s. The U.S. Navy decided that League Island, shown here, would be the site of its new shipyard in 1868 and by 1871 construction was complete. The League Island Navy Yard featured one drydock, built in 1891, but the Spanish-American War created the need for additional drydocks along with new shop buildings. The League Island Navy Yard remained an integral part of the United States Navy through both world wars. The navy finally ended most of its activity at the site in 1990. In 2000, the city of Philadelphia took over the majority of the League Island Navy Yard to redevelop the space for business.

Philadelphia Peace Jubilee Athenian Arch

After suffering two crushing naval losses and with its armies on the brink of defeat, Spain accepted the futility of continuing the struggle and negotiated an armistice that began on August 12, 1898; a formal peace treaty followed four months later. Once hostilities concluded, the city of Philadelphia planned a Peace Jubilee to celebrate the nation’s victory over Spain. The focal point of the Philadelphia Peace Jubilee was a towering, electrically illuminated, Athenian arch, shown here in 1898, that spanned Broad Street near Sansom, bisecting a Court of Honor of ornate columns lining Broad Street from city hall to Walnut Street.

The celebration commenced on October 25, 1898, with a grand naval pageant of boats on the Delaware River. Two days later twenty-five thousand soldiers, many from Philadelphia, marched down the Court of Honor under the respectful gaze of President William McKinley. The festivities concluded October 28 with a vast civic parade representing many of the city’s diverse ethnic, social, business, civil, and educational organizations. Spectators traveled from all over the United States to attend, and most major newspapers covered the occasion.

The USS Olympia

Visit Philadelphia

Philadelphia remains tied to the Spanish-American War in the form of the USS Olympia (left), the flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron, which led a devastating attack on a Spanish fleet in Manila Bay that destroyed every enemy warship without the loss of a single American vessel. This stunning victory brought both Commodore George Dewey (1837–1917) and his flagship national recognition. The Olympia was eventually retired in 1922 to the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and in 1957 the navy ceded the ship to the Cruiser Olympia Association, a nonprofit organization established to acquire Olympia artifacts and raise funds for the boat’s preservation. Docked at Penn’s Landing, the next year the ship opened to the public as a floating museum. (Photograph by M. Fischetti)

Related Topics

- Greater Philadelphia

- Philadelphia and the World

- Philadelphia and the Nation

- Workshop of the World

Time Periods

- Nineteenth Century after 1854

- Center City Philadelphia

- Independence Seaport Museum

- Veterans and Veterans’ Organizations

- Camden, New Jersey

- Chester, Pennsylvania

- World War I

Related Reading

Burr, Lawrence. US Cruisers 1883-1904 . Long Island City: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2008.

Dorwart, Jeffery M. and Philip English Mackey. Camden County, New Jersey 1616-1976: A Narrative History . Camden County, New Jersey: Camden County Cultural & Heritage Commission, 1976.

Jackson, Joseph. Encyclopedia of Philadelphia . Harrisburg, Pa.: The National Historical Association, 1931-33.

Lee, Francis Bazley. New Jersey as a Colony and as a State , Vol. 4. New York: The Publishing Society of New Jersey, 1902.

Marks, George P. III ed. The Black Press Views American Imperialism (1898-1900) . New York: Arno Press and The New York Times, 1971.

Miller, Bonnie M. From Liberation to Conquest: The Visual and Popular Cultures of the Spanish American War of 1898 . Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011.

Record of Pennsylvania Volunteers in the Spanish American War, 1898 . Harrisburg, Pa.: W. S. Ray, State Printer, 1900.

Toll, Jean Barth and Mildred S. Gillam eds. Invisible Philadelphia: Community through Voluntary Organizations . Philadelphia: Atwater Kent Museum, 1995.

Traxel, David. 1898: The Birth of the American Century . New York: Alfred A. Knopf: Distributed by Random House, 1898.

Vitiello, Domenic. Engineering Philadelphia: The Sellers Family and the Industrial Metropolis . Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2013.

Weigley, Russell F., ed. Philadelphia: A 300-Year History . New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1982.

Zilg, Gerard Colby. Du Pont: Behind the Nylon Curtain . Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1974.

Related Collections

- Cruiser Olympia Association Collection 1954-1996 J. Welles Henderson Research Center (Independence Seaport Museum) 211 S. Christopher Columbus Boulevard, Philadelphia.

- E.I. du Pont de Nemour & Company Records, 1800-1905 Hagley Museum and Library 200 Hagley Road, Wilmington, Delaware.

- J. Hampton Moore Peace Jubilee Celebration Collection 1898-1899 Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia.

- Carpenter Family Papers Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia.

- Universal Peace Union Records, Peace Collection Swarthmore College 500 College Avenue, Swarthmore, Pa.

Related Places

- USS Olympia, Independence Seaport Museum

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Setting sale: USS Olympia now on the market (WHYY, March 31, 2011)

- Historic USS Olympia patched at Penn's Landing (WHYY, July 27, 2011)

- Olympia sticking in Philadelphia, still dealing with 'severe skin problem' (WHYY, April 4, 2014)

- PhilaPlace: Cramp Shipyard — “A Community Organization and a Community Institution” (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Philadelphia Peace Jubilee of 1898 (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- League Island before the Navy Yard (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The World of 1898: The Spanish American War (Library of Congress)

- American Imperialism: The Spanish American War Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)

Connecting the Past with the Present, Building Community, Creating a Legacy

Chapter 20: An Age of Empire—American Foreign Policy, 1890-1914

The spanish-american war and overseas empire, learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the origins and events of the Spanish-American War

- Analyze the different American opinions on empire at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War

- Describe how the Spanish-American War intersected with other American expansions to solidify the nation’s new position as an empire

The Spanish-American War was the first significant international military conflict for the United States since its war against Mexico in 1846; it came to represent a critical milestone in the country’s development as an empire. Ostensibly about the rights of Cuban rebels to fight for freedom from Spain, the war had, for the United States at least, a far greater importance in the country’s desire to expand its global reach.

The Spanish-American War was notable not only because the United States succeeded in seizing territory from another empire, but also because it caused the global community to recognize that the United States was a formidable military power. In what Secretary of State John Hay called “a splendid little war,” the United States significantly altered the balance of world power, just as the twentieth century began to unfold.

Whereas Americans thought of the Spanish colonial regime in Cuba as a typical example of European imperialism, this 1896 Spanish cartoon depicts the United States as a land-grabbing empire. The caption, written in Catalan, states “Keep the island so it won’t get lost.”

THE CHALLENGE OF DECLARING WAR

Despite its name, the Spanish-American War had less to do with the foreign affairs between the United States and Spain than Spanish control over Cuba and its possessions in the Far East. Spain had dominated Central and South America since the late fifteenth century. But, by 1890, the only Spanish colonies that had not yet acquired their independence were Cuba and Puerto Rico. On several occasions prior to the war, Cuban independence fighters in the Cuba Libre movement had attempted unsuccessfully to end Spanish control of their lands. In 1895, a similar revolt for independence erupted in Cuba; again, Spanish forces under the command of General Valeriano Weyler repressed the insurrection. Particularly notorious was their policy of re-concentration in which Spanish troops forced rebels from the countryside into military-controlled camps in the cities, where many died from harsh conditions.

As with previous uprisings, Americans were largely sympathetic to the Cuban rebels’ cause, especially as the Spanish response was notably brutal. Evoking the same rhetoric of independence with which they fought the British during the American Revolution, several people quickly rallied to the Cuban fight for freedom. Shippers and other businessmen, particularly in the sugar industry, supported American intervention to safeguard their own interests in the region. Likewise, the “Cuba Libre” movement founded by José Martí , who quickly established offices in New York and Florida, further stirred American interest in the liberation cause. The difference in this uprising, however, was that supporters saw in the renewed U.S. Navy a force that could be a strong ally for Cuba. Additionally, the late 1890s saw the height of yellow journalism, in which newspapers such as the New York Journal , led by William Randolph Hearst, and the New York World , published by Joseph Pulitzer, competed for readership with sensationalistic stories. These publishers, and many others who printed news stories for maximum drama and effect, knew that war would provide sensational copy.

However, even as sensationalist news stories fanned the public’s desire to try out their new navy while supporting freedom, one key figure remained unmoved. President William McKinley, despite commanding a new, powerful navy, also recognized that the new fleet—and soldiers—were untested. Preparing for a reelection bid in 1900, McKinley did not see a potential war with Spain, acknowledged to be the most powerful naval force in the world, as a good bet. McKinley did publicly admonish Spain for its actions against the rebels, and urged Spain to find a peaceful solution in Cuba, but he remained resistant to public pressure for American military intervention.

McKinley’s reticence to involve the United States changed in February 1898. He had ordered one of the newest navy battleships, the USS Maine , to drop anchor off the coast of Cuba in order to observe the situation, and to prepare to evacuate American citizens from Cuba if necessary. Just days after it arrived, on February 15, an explosion destroyed the Maine , killing over 250 American sailors. Immediately, yellow journalists jumped on the headline that the explosion was the result of a Spanish attack, and that all Americans should rally to war. The newspaper battle cry quickly emerged, “Remember the Maine!” Recent examinations of the evidence of that time have led many historians to conclude that the explosion was likely an accident due to the storage of gun powder close to the very hot boilers. But in 1898, without ready evidence, the newspapers called for a war that would sell papers, and the American public rallied behind the cry.

Although later reports would suggest the explosion was due to loose gunpowder onboard the ship, the press treated the explosion of the USS Maine as high drama. Note the lower headline citing that the ship was destroyed by a mine, despite the lack of evidence.

McKinley made one final effort to avoid war, when late in March, he called on Spain to end its policy of concentrating the native population in military camps in Cuba, and to formally declare Cuba’s independence. Spain refused, leaving McKinley little choice but to request a declaration of war from Congress. Congress received McKinley’s war message, and on April 19, 1898, they officially recognized Cuba’s independence and authorized McKinley to use military force to remove Spain from the island. Equally important, Congress passed the Teller Amendment to the resolution, which stated that the United States would not annex Cuba following the war.

WAR: BRIEF AND DECISIVE

The Spanish-American War lasted approximately ten weeks, and the outcome was clear: The United States triumphed in its goal of helping liberate Cuba from Spanish control. Despite the positive result, the conflict did present significant challenges to the United States military. Although the new navy was powerful, the ships were, as McKinley feared, largely untested. Similarly untested were the American soldiers. The country had fewer than thirty thousand soldiers and sailors, many of whom were unprepared to do battle with a formidable opponent. But volunteers sought to make up the difference. Over one million American men—many lacking a uniform and coming equipped with their own guns—quickly answered McKinley’s call for able-bodied men. Nearly ten thousand African American men also volunteered for service, despite the segregated conditions and additional hardships they faced, including violent uprisings at a few American bases before they departed for Cuba. The government, although grateful for the volunteer effort, was still unprepared to feed and supply such a force, and many suffered malnutrition and malaria for their sacrifice.

To the surprise of the Spanish forces who saw the conflict as a clear war over Cuba, American military strategists prepared for it as a war for empire. More so than simply the liberation of Cuba and the protection of American interests in the Caribbean, military strategists sought to further Mahan’s vision of additional naval bases in the Pacific Ocean, reaching as far as mainland Asia. Such a strategy would also benefit American industrialists who sought to expand their markets into China. Just before leaving his post for volunteer service as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. cavalry, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt ordered navy ships to attack the Spanish fleet in the Philippines, another island chain under Spanish control. As a result, the first significant military confrontation took place not in Cuba but halfway around the world in the Philippines. Commodore George Dewey led the U.S. Navy in a decisive victory, sinking all of the Spanish ships while taking almost no American losses. Within a month, the U.S. Army landed a force to take the islands from Spain, which it succeeded in doing by mid-August 1898.

The victory in Cuba took a little longer. In June, seventeen thousand American troops landed in Cuba. Although they initially met with little Spanish resistance, by early July, fierce battles ensued near the Spanish stronghold in Santiago. Most famously, Theodore Roosevelt led his Rough Riders, an all-volunteer cavalry unit made up of adventure-seeking college graduates, and veterans and cowboys from the Southwest, in a charge up Kettle Hill, next to San Juan Hill, which resulted in American forces surrounding Santiago. The victories of the Rough Riders are the best known part of the battles, but in fact, several African American regiments, made up of veteran soldiers, were instrumental to their success. The Spanish fleet made a last-ditch effort to escape to the sea but ran into an American naval blockade that resulted in total destruction, with every Spanish vessel sunk. Lacking any naval support, Spain quickly lost control of Puerto Rico as well, offering virtually no resistance to advancing American forces. By the end of July, the fighting had ended and the war was over. Despite its short duration and limited number of casualties—fewer than 350 soldiers died in combat, about 1,600 were wounded, while almost 3,000 men died from disease—the war carried enormous significance for Americans who celebrated the victory as a reconciliation between North and South.

“Smoked Yankees”: Black Soldiers in the Spanish-American War

The decision to fight or not was debated in the black community, as some felt they owed little to a country that still granted them citizenship in name only, while others believed that proving their patriotism would enhance their opportunities. (credit: Library of Congress)

The most popular image of the Spanish-American War is of Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, charging up San Juan Hill. But less well known is that the Rough Riders struggled mightily in several battles and would have sustained far more serious casualties, if not for the experienced black veterans—over twenty-five hundred of them—who joined them in battle. These soldiers, who had been fighting the Indian wars on the American frontier for many years, were instrumental in the U.S. victory in Cuba.

The choice to serve in the Spanish-American War was not a simple one. Within the black community, many spoke out both for and against involvement in the war. Many black Americans felt that because they were not offered the true rights of citizenship it was not their burden to volunteer for war. Others, in contrast, argued that participation in the war offered an opportunity for black Americans to prove themselves to the rest of the country. While their presence was welcomed by the military which desperately needed experienced soldiers, the black regiments suffered racism and harsh treatment while training in the southern states before shipping off to battle.

Once in Cuba, however, the “Smoked Yankees,” as the Cubans called the black American soldiers, fought side-by-side with Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, providing crucial tactical support to some of the most important battles of the war. After the Battle of San Juan, five black soldiers received the Medal of Honor and twenty-five others were awarded a certificate of merit. One reporter wrote that “if it had not been for the Negro cavalry, the Rough Riders would have been exterminated.” He went on to state that, having grown up in the South, he had never been fond of black people before witnessing the battle. For some of the soldiers, their recognition made the sacrifice worthwhile. Others, however, struggled with American oppression of Cubans and Puerto Ricans, feeling kinship with the black residents of these countries now under American rule.

ESTABLISHING PEACE AND CREATING AN EMPIRE

As the war closed, Spanish and American diplomats made arrangements for a peace conference in Paris. They met in October 1898, with the Spanish government committed to regaining control of the Philippines, which they felt were unjustly taken in a war that was solely about Cuban independence. While the Teller Amendment ensured freedom for Cuba, President McKinley was reluctant to relinquish the strategically useful prize of the Philippines. He certainly did not want to give the islands back to Spain, nor did he want another European power to step in to seize them. Neither the Spanish nor the Americans considered giving the islands their independence, since, with the pervasive racism and cultural stereotyping of the day, they believed the Filipino people were not capable of governing themselves. William Howard Taft, the first American governor-general to oversee the administration of the new U.S. possession, accurately captured American sentiments with his frequent reference to Filipinos as “our little brown brothers.”

As the peace negotiations unfolded, Spain agreed to recognize Cuba’s independence, as well as recognize American control of Puerto Rico and Guam. McKinley insisted that the United States maintain control over the Philippines as an annexation, in return for a $20 million payment to Spain. Although Spain was reluctant, they were in no position militarily to deny the American demand. The two sides finalized the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898. With it came the international recognition that there was a new American empire that included the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The American press quickly glorified the nation’s new reach, as expressed in the cartoon below, depicting the glory of the American eagle reaching from the Philippines to the Caribbean.

This cartoon from the Philadelphia Press, showed the reach of the new American empire, from Puerto Rico to the Philippines.

Domestically, the country was neither unified in their support of the treaty nor in the idea of the United States building an empire at all. Many prominent Americans, including Jane Addams, former President Grover Cleveland, Andrew Carnegie, Mark Twain, and Samuel Gompers, felt strongly that the country should not be pursuing an empire, and, in 1898, they formed the Anti-Imperialist League to oppose this expansionism. The reasons for their opposition were varied: Some felt that empire building went against the principles of democracy and freedom upon which the country was founded, some worried about competition from foreign workers, and some held the xenophobic viewpoint that the assimilation of other races would hurt the country. Regardless of their reasons, the group, taken together, presented a formidable challenge. As foreign treaties require a two-thirds majority in the U.S. Senate to pass, the Anti-Imperialist League’s pressure led them to a clear split, with the possibility of defeat of the treaty seeming imminent. Less than a week before the scheduled vote, however, news of a Filipino uprising against American forces reached the United States. Undecided senators were convinced of the need to maintain an American presence in the region and preempt the intervention of another European power, and the Senate formally ratified the treaty on February 6, 1899.

The newly formed American empire was not immediately secure, as Filipino rebels, led by Emilio Aguinaldo, fought back against American forces stationed there. The Filipinos’ war for independence lasted three years, with over four thousand American and twenty thousand Filipino combatant deaths; the civilian death toll is estimated as high as 250,000. Finally, in 1901, President McKinley appointed William Howard Taft as the civil governor of the Philippines in an effort to disengage the American military from direct confrontations with the Filipino people. Under Taft’s leadership, Americans built a new transportation infrastructure, hospitals, and schools, hoping to win over the local population. The rebels quickly lost influence, and Aguinaldo was captured by American forces and forced to swear allegiance to the United States. The Taft Commission, as it became known, continued to introduce reforms to modernize and improve daily life for the country despite pockets of resistance that continued to fight through the spring of 1902. Much of the commission’s rule centered on legislative reforms to local government structure and national agencies, with the commission offering appointments to resistance leaders in exchange for their support. The Philippines continued under American rule until they became self-governing in 1946.

Philippine president Emilio Aguinaldo was captured after three years of fighting with U.S. troops. He is seen here boarding the USS Vicksburg after taking an oath of loyalty to the United States in 1901.

After the conclusion of the Spanish-American War and the successful passage of the peace treaty with Spain, the United States continued to acquire other territories. Seeking an expanded international presence, as well as control of maritime routes and naval stations, the United States grew to include Hawaii, which was granted territorial status in 1900, and Alaska, which, although purchased from Russia decades earlier, only became a recognized territory in 1912. In both cases, their status as territories granted U.S. citizenship to their residents. The Foraker Act of 1900 established Puerto Rico as an American territory with its own civil government. It was not until 1917 that Puerto Ricans were granted American citizenship. Guam and Samoa, which had been taken as part of the war, remained under the control of the U.S. Navy. Cuba, which after the war was technically a free country, adopted a constitution based on the U.S. Constitution. While the Teller Amendment had prohibited the United States from annexing the country, a subsequent amendment, the Platt Amendment, secured the right of the United States to interfere in Cuban affairs if threats to a stable government emerged. The Platt Amendment also guaranteed the United States its own naval and coaling station on the island’s southern Guantanamo Bay and prohibited Cuba from making treaties with other countries that might eventually threaten their independence. While Cuba remained an independent nation on paper, in all practicality the United States governed Cuba’s foreign policy and economic agreements.

Section Summary

In the wake of the Civil War, American economic growth combined with the efforts of Evangelist missionaries to push for greater international influence and overseas presence. By confronting Spain over its imperial rule in Cuba, the United States took control of valuable territories in Central America and the Pacific. For the United States, the first step toward becoming an empire was a decisive military one. By engaging with Spain, the United States was able to gain valuable territories in Latin America and Asia, as well as send a message to other global powers. The untested U.S. Navy proved superior to the Spanish fleet, and the military strategists who planned the war in the broader context of empire caught the Spanish by surprise. The annexation of the former Spanish colonies of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, combined with the acquisition of Hawaii, Samoa, and Wake Island, positioned the United States as the predominant world power in the South Pacific and the Caribbean. While some prominent figures in the United States vehemently disagreed with the idea of American empire building, their concerns were overruled by an American public—and a government—that understood American power overseas as a form of prestige, prosperity, and progress.

Review Questions

- What was the role of the Taft Commission?

- What challenges did the U.S. military have to overcome in the Spanish-American War? What accounted for the nation’s eventual victory?

Answers to Review Questions

- The Taft Commission introduced reforms to modernize and improve daily life in the Philippines. Many of these reforms were legislative in nature, impacting the structure and composition of local governments. In exchange for the support of resistance leaders, for example, the commission offered them political appointments.

- The Spanish-American War posed a series of challenges to the United States’ military capacities. The new U.S. Navy, while impressive, was still untested, and no one was certain how the new ships would perform. Further, the country had a limited army, with fewer than thirty thousand soldier and sailors. While over one million men ultimately volunteered for service, they were untrained, and the army was ill-prepared to house, arm, and feed them all. Eventually, American naval strength, combined with the proximity of American supplies relative to the distance Spanish forces traveled, made the decisive difference. In a war upon the sea, the U.S. Navy proved superior in both the Philippines and the blockade of Cuba.

Anti-Imperialist League a group of diverse and prominent Americans who banded together in 1898 to protest the idea of American empire building

Rough Riders Theodore Roosevelt’s cavalry unit, which fought in Cuba during the Spanish-American War

yellow journalism sensationalist newspapers who sought to manufacture news stories in order to sell more papers

- US History. Authored by : P. Scott Corbett, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Paul Vickery, and Sylvie Waskiewicz. Provided by : OpenStax College. Located at : http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11740/latest/

Spanish American War: Implications & American Imperialism

- President McKinley

- Conflict in Cuba

- Conflict in the Philippines

- Conflict in Puerto Rico

- Rough Riders

- Theodore Roosevelt

- Treaty of Paris

- Implications & American Imperialism

- Outcomes & Further Imperialism A key outcome of the Spanish-American War was the acquisition of overseas territories, arguably for the first time in U.S. history. The United States became an imperial power, owning colonies it had no intention of incorporating into the nation as states. It newly ruled over Hawai'i, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines directly. The United States also exercised a large amount of indirect control over Cuba through the mechanism of the Platt Amendment, a U.S. law whose substance was written into the Cuban constitution. It placed limits on Cuban sovereignty regarding financial affairs and the nature of Cuba's government, mandated U.S. ownership of a base at Guantanamo, and forced Cuban acquiescence in U.S. intervention to guarantee these measures. The U.S. empire was a layered one. Cuba experienced effective control, but indirectly. Hawai'i was governed as an incorporated territory, theoretically eligible for statehood, but its racial mix made that an unappealing prospect for many Americans. Hawai'i did not become a state until 1959. Guam was ruled directly by the U.S. Navy—which used it as a coaling station—and it remains part of the United States, governed by the Office of Insular Affairs in the Department of the Interior. Both the Philippines and Puerto Rico were governed directly as colonies through the Bureau of Insular Affairs, but their paths quickly diverged. Puerto Rico developed close links with the United States through revolving migration, economic and tourism ties, and increased political rights for its citizens. Puerto Rico is still part of the United States, as the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. The Philippines developed more modest and ambiguous relations with the United States, since Filipinos had restricted migration rights, and U.S. economic investment in the islands was limited. The Philippines achieved independence in 1946. The layered and decentralized nature of the U.S. empire developed out of the particular legal and political processes used to decide how to rule over territories acquired in the Spanish-American War. These decisions were widely and publicly debated in the early twentieth century, as Americans wrestled with the changing nature of territorial expansion involving overseas colonies. The Spanish-American War and the resulting acquisition of colonies prompted heated debates in the United States about what it meant to be American. These debates may well be among the most important consequences of the war for the nation. One set of agruments revolved around whether the United States should acquire overseas colonies, and if so, how they should be governed. A vocal and prominent anti-imperialist movement had many older leaders, representatives of a fading generation. Most politicians of the day advocated acquiring the colonies as demonstration of U.S. power and benevolence. Still, there remained a contentious debate about the status of these new territories, legally settled only by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Insular Cases, beginning in 1901 with Downes v. Bidwell and confirmed subsequently by almost two dozen additional cases. The 1901 decision found that Puerto Rico was “not a foreign country” but “foreign to the United States in a domestic sense.” In other words, not all laws or constitutional protections extended to unincorporated territories such as Puerto Rico and the Philippines. Many Americans were disturbed by these decisions, finding no provision in the Constitution that anticipated ruling land not intended to be part of the United States. They worried that an important part of U.S. political identity was being discarded. Overriding those concerns, however, was a strong desire on the part of almost all white Americans to avoid the racial implications of incorporating places like the Philippines and especially Cuba into the body politic. Jim Crow segregation was established by the 1890s, and colonial acquisitions promised to complicate an already contentious racial situation in the United States. Cuba was filled with what many commentators called an “unappealing racial mix” of descendants of Spaniards, indigenous peoples, and Africans brought to the island as slaves. U.S. politicians had no desire to bring the racial politics of Cuba into the nation; so Cuba was not annexed. The Philippines was almost as problematic: Filipinos might be the “little brown brothers” of Americans, but in the end they were Asians, including many ethnic Chinese. During these years of Chinese exclusion, the status of Filipinos, U.S. nationals eligible to enter to the United States but not eligible to become citizens, was contested and contradictory. Movement toward granting independence seemed a good way to exclude Filipinos altogether. Puerto Ricans were, apparently, white enough. When they moved to the continental United States, they could naturalize as U.S. citizens, and in 1917, citizenship was extended to all Puerto Ricans. Regarding these groups, however, racial politics complicated both colonial governance and conceptions of U.S. identity.

Credo Reference is an easy-to-use tool for starting research. Gather background information on your topic from hundreds of full-text encyclopedias, dictionaries, thesauri, quotations, and subject-specific titles, as well as 500,000+ images and audio files and over 1,000 videos.

Learn more about Credo Reference using the resources below:

Search Tips

View our tip sheet for information on how to locate materials in this database. View our Credo Reference Research Guide to learn more about navigating this database.

More Places to Search

Explore our General Resources for Research: Multidisciplinary Databases research guide for additional resources.

American Imperialism: Crash Course US History #28

- American Imperialism: Crash Course US History #28 ohn Green teaches you about Imperialism. In the late 19th century, the great powers of Europe were running around the world obtaining colonial possessions, especially in Africa and Asia. The United States, which as a young country was especially susceptible to peer pressure, followed along and snapped up some colonies of its own. The US saw that Spain's hold on its empire was weak, and like some kind of expansionist predator, it jumped into the Cuban War for Independence and turned it into the Spanish-Cuban-Phillipino-American War, which usually just gets called the Spanish-American War. John will tell you how America turned this war into colonial possessions like Puerto Rico, The Philippines, and almost even got to keep Cuba. The US was busy in the Pacific as well, wresting control of Hawaii from the Hawaiians. All this and more in a globe-trotting, oppressing episode of Crash Course US History.

- 1898 and Its Aftermath: America’s Imperial Influence Throughout the late nineteenth century, Cubans and Filipinos led calls for independence against Spanish colonial rule. In 1898 the United States entered the conflict under the guise of supporting liberty and democracy abroad, declaring war on Spain. The Treaty of Paris of 1898, which ended the war as well as Spanish colonial rule, resulted in the U.S. acquisition of territories off its coasts. This microsyllabus, 1898 and Its Aftermath: America’s Imperial Influence, collects articles that use the 1898 Spanish-Cuban-American War as a jumping-off point to understand how issues such as labor, citizenship, weather, and sports were impacted by America’s racism and white supremacy across the globe.

- Meanings of Citizenship in the U.S. Empire: Puerto Rico, Isabel Gonzalez, and the Supreme Court, 1898 to 1905 Erman discusses citizenship in the US with an examination of the case of Isabel Gonzalez. The case, "Gonzales v. Williams" (1904), was the first in which the Supreme Court confronted the citizenship status of inhabitants of territories acquired by the United States during its deliberate turn toward imperialism in the late nineteenth century. As with many cases, a combination of Gonzalez's actions and circumstances gave rise to the challenge. The conclusion is drawn that Isabel Gonzalez's challenge to immigration officials' attempts to exclude her as an alien likely to become a public charge sparked administrative, legal, and media discussions about the status of Puerto Ricans. These discussions explicitly linked problems of colonial administration to issues of immigration and to US doctrines acquiescing in treatment of US citizens--chiefly women and people of color--as dependent and unequal.

- U.S. Control Over Cuban Sugar Production, 1898-1902 For years many Americans have assumed that the United States has exploited Cuba. The greatest opportunity for this control existed when the United States occupied Cuba after the Spanish-American War. The island was ravaged by war, famine, and disease, and the Cubans were exhausted after nearly a decade of depression, and revolution. It would have been easy for the U.S. government and business interests to control Cuba economically. Yet this did not occur. By concentrating our attention upon Cuban sugar production, perhaps the real nature of United States-Cuban economic relations may become apparent.In the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, the McKinley administration found itself caught between two forces. The Congressional Joint Resolution of April 20, 1898, bound the Americans to leave Cuba once the island was pacified, but the Paris Peace Treaty of December 10, 1898, assumed that the United States would remain for a period of reconstruction.

Perspectives

Empire for Liberty

The men who spoke of liberty to shape an American empire How could the United States, a nation founded on the principles of liberty and equality, have produced Abu Ghraib, torture memos, Plamegate, and warrantless wiretaps? Did America set out to become an empire? And if so, how has it reconciled its imperialism--and in some cases, its crimes--with the idea of liberty so forcefully expressed in the Declaration of Independence? Empire for Liberty tells the story of men who used the rhetoric of liberty to further their imperial ambitions, and reveals that the quest for empire has guided the nation's architects from the very beginning--and continues to do so today. Historian Richard Immerman paints nuanced portraits of six exceptional public figures who manifestly influenced the course of American empire: Benjamin Franklin, John Quincy Adams, William Henry Seward, Henry Cabot Lodge, John Foster Dulles, and Paul Wolfowitz. Each played a pivotal role as empire builder and, with the exception of Adams, did so without occupying the presidency. Taking readers from the founding of the republic to the Global War on Terror, Immerman shows how each individual's influence arose from a keen sensitivity to the concerns of his times; how the trajectory of American empire was relentless if not straight; and how these shrewd and powerful individuals shaped their rhetoric about liberty to suit their needs. But as Immerman demonstrates in this timely and provocative book, liberty and empire were on a collision course. And in the Global War on Terror and the occupation of Iraq, they violently collided.

American imperialism in 1898

Learn more about American imperialism as implicated in the Spanish American War.

American imperialism in 1898; the quest for national fulfillment.

Explore the role of American imperialism during the Spanish American role.

- American Imperialism in the Philippines- CSU Northridge University Library Spain established its first permanent settlement in the Philippines in 1565. Spanish colonial control of the Philippines continued until 1898, when the United States took possession of the islands as a territory after winning the Spanish-American War. The Philippine Revolution, a struggle for independence from Spanish colonial rule, had been ongoing since 1896, and news that the US would replace Spain as colonial overlord was unwelcome to many Filipinos...

- Essay 1: Imperialism and Migration-NPS The United States was conceived in imperialism. The origins of US imperial history date back to the expansion of Europeans in their search for Asia and their wars against Asians, beginning with the ancient Greeks and continuing through Portugal and Spain's 15th century voyages of "exploration."

- The History Of American Imperialism, From Bloody Conquest To Bird Poop Historian Daniel Immerwahr shares surprising stories of U.S. territorial expansion, including how the desire for bird guano compelled the seizure of remote islands. His book is How to Hide an Empire.

- << Previous: Treaty of Paris

- Last Updated: Feb 15, 2023 1:32 PM

- URL: https://southern.libguides.com/spanish-american-war

Home — Essay Samples — War — The Spanish American War

Essays on The Spanish American War

The spanish american war and its long term effects on us, the main causes and factors of the spanish american war, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Role of Spanish American War in American International Trade

The english defeat of the spanish armada in the anglo-spanish war, american involvement in imperialism and wars: spanish, world war, impact of spanish american war, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Relevant topics

- Vietnam War

- Syrian Civil War

- Israeli Palestinian Conflict

- Atomic Bomb

- Nuclear Weapon

- Treaty of Versailles

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Spanish Civil War: how the works of Ernest Hemingway and Robert Capa still define the conflict today

Profesor de Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad, Universidad CEU San Pablo

Disclosure statement

Miguel Ángel de Santiago Mateos does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Universidad CEU San Pablo provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation ES.

View all partners

From 1936 to 1939, the Spanish civil war divided neighbours, friends and families, and people both inside and outside Spain kept a close eye on what was happening in the country.

Two of the best-known international figures who, through their images and writings, managed to convey what was happening in Spain were the war photographer Robert Capa and the writer Ernest Hemingway .

There was also a personal closeness between them that impacted their work. In fact, Capa’s photographs served as inspiration for Hemingway’s writings .

Ernest Hemingway: a correspondent committed to the Republic

Hemingway, who had a previous connection with Spain, was a well known writer when he decided to return to journalism to cover the Spanish conflict for the North American Newspapers Alliance (NANA).

Hemingway’s stay during the war resulted in thirty dispatches for the American press and one more, with greater personal involvement, published in the Soviet newspaper Pravda . He also found time to describe Spanish society in writings centred on everyday life. His public image as an intrepid reporter was helped by the fact that he was, at the time, one of the best known correspondents in the world, and one of the best paid .

In time, his work expanded beyond dispatches from the Spanish Civil War to include one of his best known works: For Whom the Bell Tolls . Drawing on a combination of real life experiences and fictional content, the Nobel Prize laureate conveyed his impassioned vision in defence of the Republican cause and the Spanish people.

Hemingway’s novel came to symbolise the Spanish conflict in the collective imagination. This was amplified by the film of the same name , starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, which garnered nine Oscar nominations.

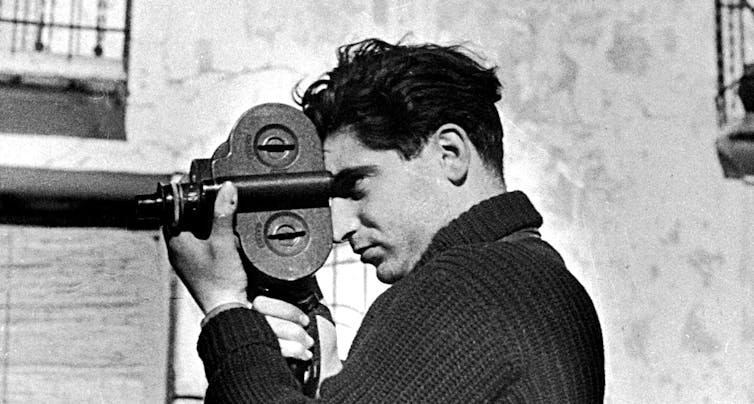

Robert Capa: an intrepid, influential photographer

Robert Capa’s images often capture what Henri Cartier-Bresson called the “decisive momnent”, meaning the culmination or apex of the event being photographed. In his photographs, the mid ground predominates, eschewing either general panoramas or minute details, with depersonalised subjects and gestures presented in stark black and white. His images are often grainy and lacking in sharpness, lending them an unique atmosphere.

Capa photographed several conflicts, including the Normandy landings . These photos are notable for their proximity to the events, which the images narrate with great clarity.

These images of D-Day inspired a similar visual language in Steven Spielberg’s film Saving Private Ryan . This is especially evident in the opening Normandy landing scene, where the aesthetic helps to create an unreal and unsettling atmosphere, mainly due to the grain of the film and the slight blurring that characterised Capa’s work.

However, Capa is most well known for his work in the Spanish Civil War. It should be noted that Robert Capa was a pseudonym adopted in 1936 – Capa’s birth name was Endré Ernö Friedmann. In addition to Capa himself, two others had previously published work under this name: his partner, Gerda Taro, who created the pseudonym and died on the Brunete front in 1937, and David Seymour (nicknamed Chim) . Once Capa was the only one using this assumed name he began to publish his first reports in the pages of the magazine Vu , almost from the very beginning of the war. Subsequently, other publications such as Regards , Ce Soir and the British magazine Picture Post began to publish his output.

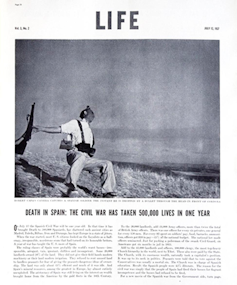

The Falling Soldier: an iconic photo mired in controversy

Although The Falling Soldier , one of Capa’s best-known photographs, was published in French magazines in 1936, it did not reach international fame until it appeared in Life in July 1937 .

It is undoubtedly one of the most widely published images of the conflict, but the circumstances surrounding this photograph – taken at the height of the conflict – have contributed to controversy over its authenticity . Its veracity has been defended by, among others, his official biographer, Richard Whelan. In a January 1999 interview with El País semanal , Whelan stated:

“The controversy has been definitively cleared up in Capa’s favour thanks to the discovery of the identity of the man in the photograph, Federico Borrell García, who was killed in Cerro Muriano, 12 kilometres north of Córdoba, on 5 September 1936.”

While not wishing to undermine the photo’s symbolic value, one of Professor José Manuel Susperregui’s investigations has deepened the controversy by relocating, on the basis of an topographic study, The Falling Soldier to Cerro del Cuco instead of Cerro Muriano.

His study concludes by stating that:

“This new information on location completely changes the reading of The Falling Soldier, and demonstrates that the author’s own version of this photograph is totally false, dismantling the various accounts based on his version of events. Additionally, other theories attribute its authorship to his companion Gerda Taro.”

Regardless of its authenticity, the image’s value is indisputable and enduring. Not only is it one of Robert Capa’s most popular photographs, it is also the best known photograph of the Spanish Civil War and one of the most famous war photos ever. It also set a precedent for spontaneity and action war photography.

The physical and intellectual proximity of foreign correspondents and Spanish journalists in the Civil War led to ideologically charged photographs and reports, which arguably bordered on propaganda, often enhanced by the name on the byline. In their new narrative perspective, civilians and anonymous people became the protagonists of war images. In the same way, everyday life was also brought into reporting.

Capa’s Falling Soldier and Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls are all but synonymous with the Spanish Civil War. Both works, much like their authors, have become emblematic of the Republican cause.

This article was originally published in Spanish

- Photography

- Ernest Hemingway

- Spanish Civil War

- War photography

- The Conversation Europe

- Robert Capa

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

African Americans in the Spanish-American War Essay

Introduction, the debate of african american involvement in the war.

The Spanish American war took place between the months of February and December in 1898. This war saw the transformation of American society from being a modest nation to a crucial player in the international arena. It also resulted in the acquisition of Guam, Puerto Rico and the Philippines through the treaty of Paris.

At the time of the Spanish American war, American society was pursuing expansionist strategies and this presented different dynamics for racial relations in the military. In that decade, the army had grown both in size and might and they therefore felt little need for black soldiers. In fact most African Americans that had been recruited in the army in the 1890s got vey poor receptions upon returning to their country. They would frequently be subjected to antiracists sentiments while serving in that army. Therefore by the time the US began pondering over expansionist strategies, tensions were still prevalent between black and white soldiers and many questioned the necessity of actually involving African Americans in any war. On the other hand, Black Americans were interested in demonstrating their ability to defend the founding principles of their nation by involving themselves in war. Despite this interest in participation, most blacks rarely got the opportunity to enter into war zones. On top of that, they were unhappy with the way they were being treated in their own countries but this did not make any of them resort to violent means.

After America witnessed the sinking of the Maine, it became clear that they had to engage in war with the Spaniards. However, this event occurred unexpectedly and caught the US off guard as its army size was not sufficient to cater for its expansionist strategies. Therefore, the country had to resort to unconventional measures for recruitment. It looked towards the African American population because these black soldiers had ample experience. Also, it was assumed that their bodies could easily adapt to humid conditions that can render them immune to the tropical diseases of the Spanish territories.

The first expedition focused on Cuba where the first black units were disseminated and they included the 10 th , 9 th , 24 th and 25 th Cavalries. They had to wait in Florida before entering Cuba and it was while in this state where racial prejudices against them were reaffirmed. Nonetheless, when they entered Cuba, they were designated to a route that lacked roads and it was quite difficult for them to march towards their targets. On the other hand, the 1 st volunteer cavalry (Rough riders) consisting of Theodore Roosevelt and other white soldiers were also assigned to this same area. They had better routes and were therefore the first to meet enemy fire. In one of their encounters at San Juan Hill, the white soldiers from the rough riders found themselves surrounding by Spaniards. They were at a very disadvantageous position and were it not for black soldiers from the 10 th and 9 th cavalries who came in and engaged enemy fire, the rough riders would have died mercilessly.

Aside from that, black soldiers also participated in Las Guasimas and El Caney battles where they demonstrated heroic actions on behalf of their country. It was this participation that led to recognition of five black soldiers who were given Medals of Honor. Twenty five soldiers were also granted certificates of merit. Examples included George Anderson, Lt, Jacob Smith, Cpt. Horace Wheaton and Colonel Charles Young. Later on in 1922, the Spanish American war was reviewed and eight more soldiers were accredited for their actions. The tenacity and courage with which these soldiers fought for their countries was quite admirable especially given the fact that a substantial number of them accepted missions that had been rejected by white only soldiers. For instance in the month of July 1989, the 24 th infantry accepted a mission that eight white units refused.

Despite all this patriotism, there was a lot of controversy concerning the treatment of the black soldiers who participated in this war as racists often tried to downplay their importance in the war. Those volunteers who came back from the Spanish American war were treated in a cruel manner by their fellow citizens. Most of them were not allowed to eat at the same table or even in the same restaurant as white patrons. For instance, in Kansas City, white soldiers would often be invited into restaurants and given free food while the black soldiers would be greeted by sneers. This implied that white supremacists try to ignore the importance of those soldiers during the war. They assumed that America was only able to secure the three Spanish territories as a result of white only efforts. In fact, it is this point of view that was recorded by many war analysts as very little emphasis was given to a holistic view of all the citizens that took part in the war. Most of the returning soldiers were not promoted within the army and very few of them were encouraged to continue serving their nation.

The Spanish American war was crucial to African Americans in a number of ways. First of all, it allowed for the use of black commanders within their units, secondly, it provided them with an opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism outside of US soil and lastly it led to eventual recognition by Great American leaders such as President Roosevelt who had served alongside the black soldiers.

- U.S. Involvement in International Affairs

- Theodore Roosevelt as the Man and the American

- US International Affairs Between 1890 and 1920

- Status of Women and Free African Americans

- Discussion Against the Afro-Centric School in Toronto

- The African Burial Ground Project

- Lynching History of African Americans: An Absurd Illegal Justice System in the 19th Century

- African Slavery and European Plantation Systems: 1525-1700

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 14). African Americans in the Spanish-American War. https://ivypanda.com/essays/african-americans-in-the-spanish-american-war/

"African Americans in the Spanish-American War." IvyPanda , 14 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/african-americans-in-the-spanish-american-war/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'African Americans in the Spanish-American War'. 14 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "African Americans in the Spanish-American War." December 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/african-americans-in-the-spanish-american-war/.

1. IvyPanda . "African Americans in the Spanish-American War." December 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/african-americans-in-the-spanish-american-war/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "African Americans in the Spanish-American War." December 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/african-americans-in-the-spanish-american-war/.

Getting Personal About Wilderness

Tisbe Rinehart is at home in the forests of the Pacific Northwest. At the UW, she has shared her love of the Northwest landscape as an outdoor educator and guide with UWild , including trips for first-year students starting their UW experience.

“At first, the students are so nervous about going to the UW,” says Rinehart, who will receive her BA with departmental honors in comparative history of ideas (CHID) this June. “By the end of a multi-day adventure trip, they have a friend group and feel more comfortable.”

Rinehart’s own introduction to the outdoors was less idyllic. As a high school sophomore, Rinehart was sent to a Wilderness Therapy program that was, ostensibly, a treatment for troubled teens. The experience was fraught for Rinehart, but it did wake in her an appreciation for the natural world.

It also inspired her senior thesis as a CHID major in the UW College of Arts & Sciences . Combining her Wilderness Therapy experience with extensive research on the Troubled Teen Industry , Rinehart wrote a novel — yes, a novel — about that industry for her thesis. She says the project, which brought together her past and present, has also helped prepare her for the future.

Adventures in the Woods of Washington

Raised in Los Gatos, California, near San Jose, Rinehart chose the UW in part because of its location. “I really liked how it is a beautiful campus that feels like its own city, but it’s in a major metropolitan area,” Rinehart says. “At the same time, national parks are super accessible.”