Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Home / Guides / Writing Guides / Parts of a Paper / How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement

A thesis can be found in many places—a debate speech, a lawyer’s closing argument, even an advertisement. But the most common place for a thesis statement (and probably why you’re reading this article) is in an essay.

Whether you’re writing an argumentative paper, an informative essay, or a compare/contrast statement, you need a thesis. Without a thesis, your argument falls flat and your information is unfocused. Since a thesis is so important, it’s probably a good idea to look at some tips on how to put together a strong one.

Guide Overview

What is a “thesis statement” anyway.

- 2 categories of thesis statements: informative and persuasive

- 2 styles of thesis statements

- Formula for a strong argumentative thesis

- The qualities of a solid thesis statement (video)

You may have heard of something called a “thesis.” It’s what seniors commonly refer to as their final paper before graduation. That’s not what we’re talking about here. That type of thesis is a long, well-written paper that takes years to piece together.

Instead, we’re talking about a single sentence that ties together the main idea of any argument . In the context of student essays, it’s a statement that summarizes your topic and declares your position on it. This sentence can tell a reader whether your essay is something they want to read.

2 Categories of Thesis Statements: Informative and Persuasive

Just as there are different types of essays, there are different types of thesis statements. The thesis should match the essay.

For example, with an informative essay, you should compose an informative thesis (rather than argumentative). You want to declare your intentions in this essay and guide the reader to the conclusion that you reach.

To make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, you must procure the ingredients, find a knife, and spread the condiments.

This thesis showed the reader the topic (a type of sandwich) and the direction the essay will take (describing how the sandwich is made).

Most other types of essays, whether compare/contrast, argumentative, or narrative, have thesis statements that take a position and argue it. In other words, unless your purpose is simply to inform, your thesis is considered persuasive. A persuasive thesis usually contains an opinion and the reason why your opinion is true.

Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are the best type of sandwich because they are versatile, easy to make, and taste good.

In this persuasive thesis statement, you see that I state my opinion (the best type of sandwich), which means I have chosen a stance. Next, I explain that my opinion is correct with several key reasons. This persuasive type of thesis can be used in any essay that contains the writer’s opinion, including, as I mentioned above, compare/contrast essays, narrative essays, and so on.

2 Styles of Thesis Statements

Just as there are two different types of thesis statements (informative and persuasive), there are two basic styles you can use.

The first style uses a list of two or more points . This style of thesis is perfect for a brief essay that contains only two or three body paragraphs. This basic five-paragraph essay is typical of middle and high school assignments.

C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia series is one of the richest works of the 20th century because it offers an escape from reality, teaches readers to have faith even when they don’t understand, and contains a host of vibrant characters.

In the above persuasive thesis, you can see my opinion about Narnia followed by three clear reasons. This thesis is perfect for setting up a tidy five-paragraph essay.

In college, five paragraph essays become few and far between as essay length gets longer. Can you imagine having only five paragraphs in a six-page paper? For a longer essay, you need a thesis statement that is more versatile. Instead of listing two or three distinct points, a thesis can list one overarching point that all body paragraphs tie into.

Good vs. evil is the main theme of Lewis’s Narnia series, as is made clear through the struggles the main characters face in each book.

In this thesis, I have made a claim about the theme in Narnia followed by my reasoning. The broader scope of this thesis allows me to write about each of the series’ seven novels. I am no longer limited in how many body paragraphs I can logically use.

Formula for a Strong Argumentative Thesis

One thing I find that is helpful for students is having a clear template. While students rarely end up with a thesis that follows this exact wording, the following template creates a good starting point:

___________ is true because of ___________, ___________, and ___________.

Conversely, the formula for a thesis with only one point might follow this template:

___________________ is true because of _____________________.

Students usually end up using different terminology than simply “because,” but having a template is always helpful to get the creative juices flowing.

The Qualities of a Solid Thesis Statement

When composing a thesis, you must consider not only the format, but other qualities like length, position in the essay, and how strong the argument is.

Length: A thesis statement can be short or long, depending on how many points it mentions. Typically, however, it is only one concise sentence. It does contain at least two clauses, usually an independent clause (the opinion) and a dependent clause (the reasons). You probably should aim for a single sentence that is at least two lines, or about 30 to 40 words long.

Position: A thesis statement always belongs at the beginning of an essay. This is because it is a sentence that tells the reader what the writer is going to discuss. Teachers will have different preferences for the precise location of the thesis, but a good rule of thumb is in the introduction paragraph, within the last two or three sentences.

Strength: Finally, for a persuasive thesis to be strong, it needs to be arguable. This means that the statement is not obvious, and it is not something that everyone agrees is true.

Example of weak thesis:

Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are easy to make because it just takes three ingredients.

Most people would agree that PB&J is one of the easiest sandwiches in the American lunch repertoire.

Example of a stronger thesis:

Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are fun to eat because they always slide around.

This is more arguable because there are plenty of folks who might think a PB&J is messy or slimy rather than fun.

Composing a thesis statement does take a bit more thought than many other parts of an essay. However, because a thesis statement can contain an entire argument in just a few words, it is worth taking the extra time to compose this sentence. It can direct your research and your argument so that your essay is tight, focused, and makes readers think.

EasyBib Writing Resources

Writing a paper.

- Academic Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- College Admissions Essay

- Expository Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Research Paper

- Thesis Statement

- Writing a Conclusion

- Writing an Introduction

- Writing an Outline

- Writing a Summary

EasyBib Plus Features

- Citation Generator

- Essay Checker

- Expert Check Proofreader

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tools

Plagiarism Checker

- Spell Checker

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Grammar and Plagiarism Checkers

Grammar Basics

Plagiarism Basics

Writing Basics

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1929 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,694 quotes across 1929 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

Writing Academic Essays: Tips and Support: Argumentative Essay

- Informative Process Analysis

- Cause and Effect Essay

- Compare and Contrast Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Newspapers, Databases & Articles

- MLA Help, Grammar and Writing

What is an Argumentative Essay?

- Writing a Argumentative essay (video)

Other Web References

- Counterarguments

- Counterarguments from the BGSU Writers Lab

Argument Essay Assignment- Revised from LearningStudio assignment

Argumentative Essay.

Any time you try to persuade someone, you are doing argumentative writing - an argumentative essay can be cause and effect, persuasive, compare and contrast, etc. In an argumentative or persuasive essay, you i dentify something that you think is a problem, then propose a solution.

You discuss several possible solutions to it, and then argue that one solution is much better better than the others.

Steps:

· Identifying the problem . Early in your essay, you will need to identify the problem under consideration. This will require describing, defining and/or limiting the problem for background support. For example, if homelessness is the problem in the book, you may want to focus on homelessness in the U.S., or perhaps even more narrowly, on homelessness affecting U.S. children. In this part of the essay, it may also be necessary to establish the problem, to argue that it really exists and that it's really a problem. Before discussing solutions, you may have to argue that the problem is both real and worthy of our attention.

· Discussing possible solutions. Once the problem has been identified, you will turn to a discussion of possible solutions to the problem. You should discuss at least two or three alternative solutions, and each should be plausible (believable) and feasible (workable). Far-fetched or oversimplified solutions are of no use in this essay.

· Arguing that one solution is better than others . Your discussion of possible solutions will consist of examining the pros and cons of each and, by the end of the essay, it should be clear that one solution is better than all the others. As in the position paper, it is vital that you not only assert your own arguments , but also present and respond to counterarguments. Once you have asserted that this one solution is the best, the bulk of your paper will be including reasons why it is the best, again incorporating research into this section whenever possible. (See video)

· Including Counterarguments, to address the opposing viewpoint that the thing you are calling a problem may not be a problem for others. Due to the fact that all the solutions you discuss in the essay will be plausible and feasible, it is unlikely that you will be able to utterly and entirely refute all of them. In fact, you may be tempted to suggest that all the solutions should be used at once. Don't do this. In order to pass this essay, your thesis must state that, even though all the solutions might be helpful, one solution is definitely better than the others. However, this raises the question of what constitutes “better”? There are a variety of criteria. Perhaps one solution would solve the problem more thoroughly, more quickly, less expensively, or with less risk.

Details: The essay should be approximately 500 words. Please write about something you know about firsthand (meaning nothing that has to be researched by either you or me to be understood). Topics should come from your life and may be related to your job, family, or social situations. Some off-the-top-of-my-head examples are how to get kids to do chores, how to lower the speed of cars through your neighborhood, getting children to nap, getting your college roommate to be neater, etc. Again, stick to topics you know. DO NOT USE OUTSIDE SOURCES FOR ANY REASON. Please also use MLA format, as your grade depends on it. You must have a 25% or lower similarity score as usual; if not, you will be turned in as a violation of the Honor Code of Saint Leo University for plagiarism. Please ask me for help if you have questions.

- << Previous: Compare and Contrast Essay

- Next: Newspapers, Databases & Articles >>

- Last Updated: May 28, 2024 4:38 PM

- URL: https://slulibrary.saintleo.edu/essays_writing

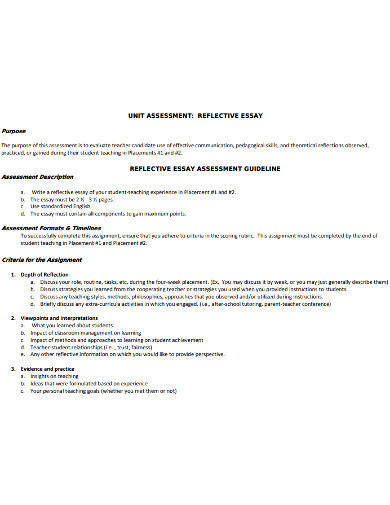

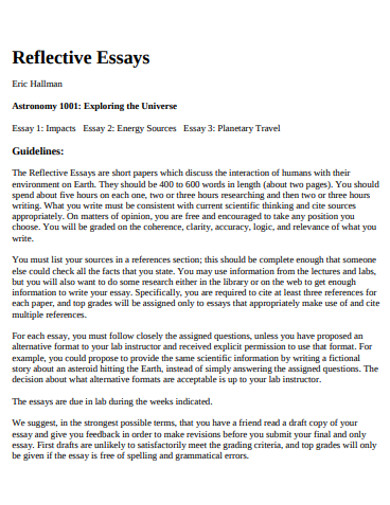

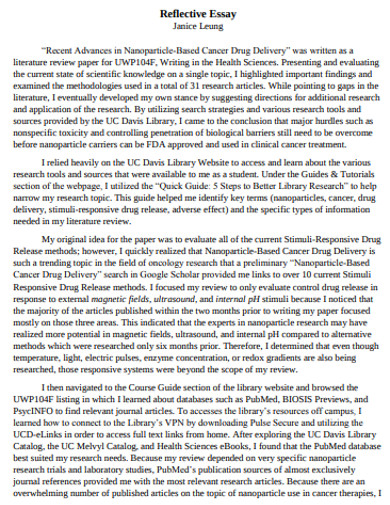

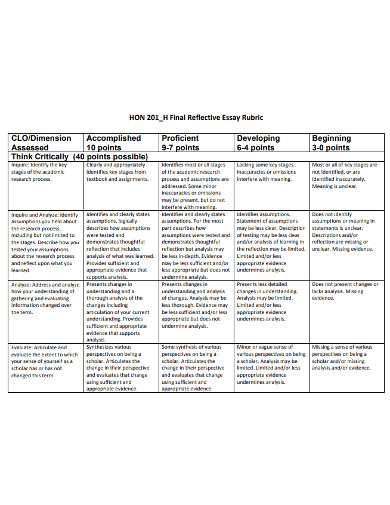

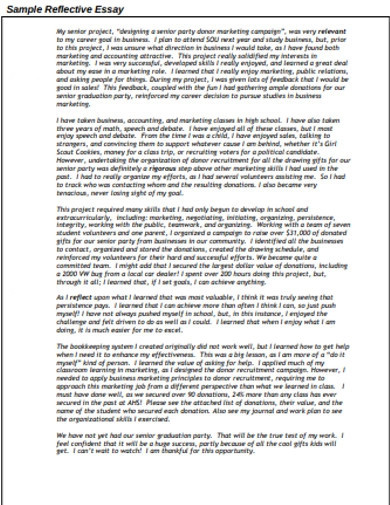

Reflective Essay

Reflective essay generator.

Sometimes, it is our experiences that startled and challenged our own voyage that strengthens and improves us to be the best versions of ourselves. If your life experience greatly moved you, there is a certain essay that allows you to compose your own endeavor. In this article, read through because we will be discussing the fundamentals of writing a reflective essay.

They say that being wise is better than being knowledgeable. Wisdom is acquired through reflection of one’s experience as well as of the environment. The more we reflect the more we become aware of ourselves. We become mindful of our existence as well as the meaning of life and all the things that surround us. Here we present different formats of essays like essays in doc .

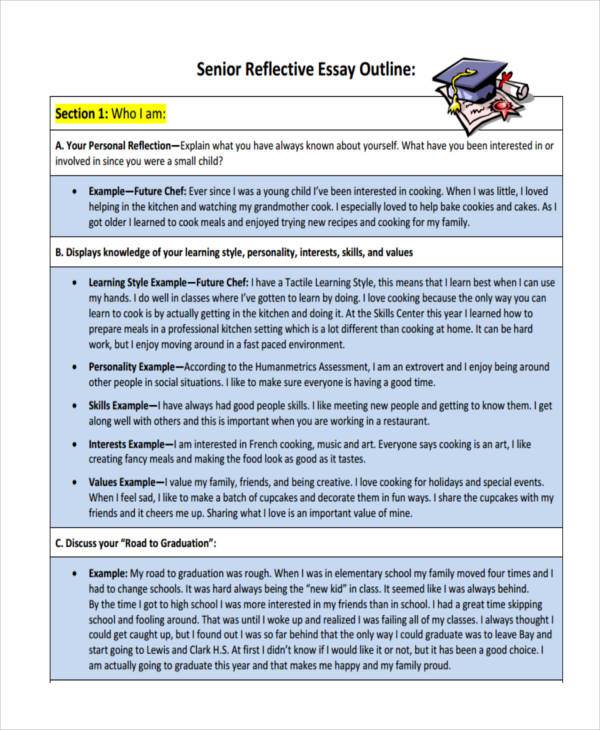

Reflective Essay Outline Template

- Google Docs

Size: 188 KB

Reflective Essay About Life Experience

- Apple Pages

Size: 142 KB

Reflective Essay Template

Size: 237 KB

Self Reflective Essay Template

Size: 114 KB

Personal Reflective Essay Template

Size: 126 KB

Personal Reflective Sample

High School Essay

- PDFReflective Essay Example Reflective Essay Example Reflective Essay Example

Size: 102 KB

Reflective Essay Outline

Size: 247 KB

Student Reflective Example

Size: 42 KB

Communication Reflective

Size: 66 KB

What Is a Reflective Essay?

A reflective essay is a written piece of literature that focuses on presenting and narrating a person’s experience and how it becomes an instrument towards a change of perception in life.

It is a way for a writer to share an important event in his/her life and how it affected him/her so that others may learn something from it. Reflective writing root on life-changing events. The writer shares a specific experience, provides a narration of the incident including the material elements. It offers a realization so that others who may have had the same experience can draw out a shared mutual lesson from it.

How to Write a Reflective Essay

To write a reflective short essay , you need to have the right disposition as well as the momentum. Remember that you are not just writing to say something but to share an important lesson in life.

1. Think of an important event. What you will be writing on your reflective essay is something that is rooted in your own personal experience or encounter of something. Think deep and concentrate. You may also see personal essay examples & samples.

2. Introduce your topic. In your introduction, write the concrete event or experience that you want to share. Pattern it in a story form.

3. Develop your point. Write the main content of your essay with at least three to five paragraphs supporting your main topic.

Final Reflective Essay

Size: 49 KB

Internship Reflective Essay

Size: 285 KB

Leadership Reflective Example

Size: 634 KB

Nursing Reflective Essay

Size: 331 KB

Research Reflective Example

Size: 155 KB

Tips on Writing a Reflective Essay

Writing a reflective essay is not persuasive writing where you have to convince your readers to accept your opinion. You simply have to share an experience.

1. Write a draft. Do not jump hastily onto formal writing . Write a draft where you can create a bulleted list of the things that you want to share.

2. Think logically. When presenting a story, do it in a chronological manner so that your readers can understand the plot. Do this as well when presenting your ideas.

3. Create a summary. Use a summary writing to briefly state your insights and to give your final thoughts of the topic.

Importance of a Reflective Essay

In this era that we currently live in, personal reflection can be considered a thing of the past. Because of the gradual change and development of the things around us, we find it difficult to pause and reflect on the things that happen to our lives. You may also see academic essay examples .

The importance of writing an essay is to present to us the things that we rarely encounter in our day-to-day activities. In this time when material things are all that mattered, we have become unappreciative of the abstract things like love, compassion, and mercy. We cannot learn these things from those electronic gadgets that keep us busy.

How to Start a Reflective Essay Correctly

As mentioned above, a reflective essay presents and narrates the experience of a writer and how it changes the way he/she perceives life. In a simpler sense, it talks about how the author reflected on a certain adventure. As an essayist, since it’s you who bears the story and lessons, you are the one who is responsible for expressing it.