English Current

ESL Lesson Plans, Tests, & Ideas

- North American Idioms

- Business Idioms

- Idioms Quiz

- Idiom Requests

- Proverbs Quiz & List

- Phrasal Verbs Quiz

- Basic Phrasal Verbs

- North American Idioms App

- A(n)/The: Help Understanding Articles

- The First & Second Conditional

- The Difference between 'So' & 'Too'

- The Difference between 'a few/few/a little/little'

- The Difference between "Other" & "Another"

- Check Your Level

- English Vocabulary

- Verb Tenses (Intermediate)

- Articles (A, An, The) Exercises

- Prepositions Exercises

- Irregular Verb Exercises

- Gerunds & Infinitives Exercises

- Discussion Questions

- Speech Topics

- Argumentative Essay Topics

- Top-rated Lessons

- Intermediate

- Upper-Intermediate

- Reading Lessons

- View Topic List

- Expressions for Everyday Situations

- Travel Agency Activity

- Present Progressive with Mr. Bean

- Work-related Idioms

- Adjectives to Describe Employees

- Writing for Tone, Tact, and Diplomacy

- Speaking Tactfully

- Advice on Monetizing an ESL Website

- Teaching your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation

- Teaching Different Levels

- Teaching Grammar in Conversation Class

- Members' Home

- Update Billing Info.

- Cancel Subscription

- North American Proverbs Quiz & List

- North American Idioms Quiz

- Idioms App (Android)

- 'Be used to'" / 'Use to' / 'Get used to'

- Ergative Verbs and the Passive Voice

- Keywords & Verb Tense Exercises

- Irregular Verb List & Exercises

- Non-Progressive (State) Verbs

- Present Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Present Simple vs. Present Progressive

- Past Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Subject Verb Agreement

- The Passive Voice

- Subject & Object Relative Pronouns

- Relative Pronouns Where/When/Whose

- Commas in Adjective Clauses

- A/An and Word Sounds

- 'The' with Names of Places

- Understanding English Articles

- Article Exercises (All Levels)

- Yes/No Questions

- Wh-Questions

- How far vs. How long

- Affect vs. Effect

- A few vs. few / a little vs. little

- Boring vs. Bored

- Compliment vs. Complement

- Die vs. Dead vs. Death

- Expect vs. Suspect

- Experiences vs. Experience

- Go home vs. Go to home

- Had better vs. have to/must

- Have to vs. Have got to

- I.e. vs. E.g.

- In accordance with vs. According to

- Lay vs. Lie

- Make vs. Do

- In the meantime vs. Meanwhile

- Need vs. Require

- Notice vs. Note

- 'Other' vs 'Another'

- Pain vs. Painful vs. In Pain

- Raise vs. Rise

- So vs. Such

- So vs. So that

- Some vs. Some of / Most vs. Most of

- Sometimes vs. Sometime

- Too vs. Either vs. Neither

- Weary vs. Wary

- Who vs. Whom

- While vs. During

- While vs. When

- Wish vs. Hope

- 10 Common Writing Mistakes

- 34 Common English Mistakes

- First & Second Conditionals

- Comparative & Superlative Adjectives

- Determiners: This/That/These/Those

- Check Your English Level

- Grammar Quiz (Advanced)

- Vocabulary Test - Multiple Questions

- Vocabulary Quiz - Choose the Word

- Verb Tense Review (Intermediate)

- Verb Tense Exercises (All Levels)

- Conjunction Exercises

- List of Topics

- Business English

- Games for the ESL Classroom

- Pronunciation

- Teaching Your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation Class

Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation

An argumentative essay presents an argument for or against a topic. For example, if your topic is working from home , then your essay would either argue in favor of working from home (this is the for side) or against working from home.

Like most essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction that ends with the writer's position (or stance) in the thesis statement .

Introduction Paragraph

(Background information....)

- Thesis statement : Employers should give their workers the option to work from home in order to improve employee well-being and reduce office costs.

This thesis statement shows that the two points I plan to explain in my body paragraphs are 1) working from home improves well-being, and 2) it allows companies to reduce costs. Each topic will have its own paragraph. Here's an example of a very basic essay outline with these ideas:

- Background information

Body Paragraph 1

- Topic Sentence : Workers who work from home have improved well-being .

- Evidence from academic sources

Body Paragraph 2

- Topic Sentence : Furthermore, companies can reduce their expenses by allowing employees to work at home .

- Summary of key points

- Restatement of thesis statement

Does this look like a strong essay? Not really . There are no academic sources (research) used, and also...

You Need to Also Respond to the Counter-Arguments!

The above essay outline is very basic. The argument it presents can be made much stronger if you consider the counter-argument , and then try to respond (refute) its points.

The counter-argument presents the main points on the other side of the debate. Because we are arguing FOR working from home, this means the counter-argument is AGAINST working from home. The best way to find the counter-argument is by reading research on the topic to learn about the other side of the debate. The counter-argument for this topic might include these points:

- Distractions at home > could make it hard to concentrate

- Dishonest/lazy people > might work less because no one is watching

Next, we have to try to respond to the counter-argument in the refutation (or rebuttal/response) paragraph .

The Refutation/Response Paragraph

The purpose of this paragraph is to address the points of the counter-argument and to explain why they are false, somewhat false, or unimportant. So how can we respond to the above counter-argument? With research !

A study by Bloom (2013) followed workers at a call center in China who tried working from home for nine months. Its key results were as follows:

- The performance of people who worked from home increased by 13%

- These workers took fewer breaks and sick-days

- They also worked more minutes per shift

In other words, this study shows that the counter-argument might be false. (Note: To have an even stronger essay, present data from more than one study.) Now we have a refutation.

Where Do We Put the Counter-Argument and Refutation?

Commonly, these sections can go at the beginning of the essay (after the introduction), or at the end of the essay (before the conclusion). Let's put it at the beginning. Now our essay looks like this:

Counter-argument Paragraph

- Dishonest/lazy people might work less because no one is watching

Refutation/Response Paragraph

- Study: Productivity increased by 14%

- (+ other details)

Body Paragraph 3

- Topic Sentence : In addition, people who work from home have improved well-being .

Body Paragraph 4

The outline is stronger now because it includes the counter-argument and refutation. Note that the essay still needs more details and research to become more convincing.

Working from home may increase productivity.

Extra Advice on Argumentative Essays

It's not a compare and contrast essay.

An argumentative essay focuses on one topic (e.g. cats) and argues for or against it. An argumentative essay should not have two topics (e.g. cats vs dogs). When you compare two ideas, you are writing a compare and contrast essay. An argumentative essay has one topic (cats). If you are FOR cats as pets, a simplistic outline for an argumentative essay could look something like this:

- Thesis: Cats are the best pet.

- are unloving

- cause allergy issues

- This is a benefit > Many working people do not have time for a needy pet

- If you have an allergy, do not buy a cat.

- But for most people (without allergies), cats are great

- Supporting Details

Use Language in Counter-Argument That Shows Its Not Your Position

The counter-argument is not your position. To make this clear, use language such as this in your counter-argument:

- Opponents might argue that cats are unloving.

- People who dislike cats would argue that cats are unloving.

- Critics of cats could argue that cats are unloving.

- It could be argued that cats are unloving.

These underlined phrases make it clear that you are presenting someone else's argument , not your own.

Choose the Side with the Strongest Support

Do not choose your side based on your own personal opinion. Instead, do some research and learn the truth about the topic. After you have read the arguments for and against, choose the side with the strongest support as your position.

Do Not Include Too Many Counter-arguments

Include the main (two or three) points in the counter-argument. If you include too many points, refuting these points becomes quite difficult.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below.

- Matthew Barton / Creator of Englishcurrent.com

Additional Resources :

- Writing a Counter-Argument & Refutation (Richland College)

- Language for Counter-Argument and Refutation Paragraphs (Brown's Student Learning Tools)

EnglishCurrent is happily hosted on Dreamhost . If you found this page helpful, consider a donation to our hosting bill to show your support!

24 comments on “ Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation ”

Thank you professor. It is really helpful.

Can you also put the counter argument in the third paragraph

It depends on what your instructor wants. Generally, a good argumentative essay needs to have a counter-argument and refutation somewhere. Most teachers will probably let you put them anywhere (e.g. in the start, middle, or end) and be happy as long as they are present. But ask your teacher to be sure.

Thank you for the information Professor

how could I address a counter argument for “plastic bags and its consumption should be banned”?

For what reasons do they say they should be banned? You need to address the reasons themselves and show that these reasons are invalid/weak.

Thank you for this useful article. I understand very well.

Thank you for the useful article, this helps me a lot!

Thank you for this useful article which helps me in my study.

Thank you, professor Mylene 102-04

it was very useful for writing essay

Very useful reference body support to began writing a good essay. Thank you!

Really very helpful. Thanks Regards Mayank

Thank you, professor, it is very helpful to write an essay.

It is really helpful thank you

It was a very helpful set of learning materials. I will follow it and use it in my essay writing. Thank you, professor. Regards Isha

Thanks Professor

This was really helpful as it lays the difference between argumentative essay and compare and contrast essay.. Thanks for the clarification.

This is such a helpful guide in composing an argumentative essay. Thank you, professor.

This was really helpful proof, thankyou!

Thanks this was really helpful to me

This was very helpful for us to generate a good form of essay

thank you so much for this useful information.

Thank you so much, Sir. This helps a lot!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Counterarguments

A counterargument involves acknowledging standpoints that go against your argument and then re-affirming your argument. This is typically done by stating the opposing side’s argument, and then ultimately presenting your argument as the most logical solution. The counterargument is a standard academic move that is used in argumentative essays because it shows the reader that you are capable of understanding and respecting multiple sides of an argument.

Counterargument in two steps

Respectfully acknowledge evidence or standpoints that differ from your argument.

Refute the stance of opposing arguments, typically utilizing words like “although” or “however.”

In the refutation, you want to show the reader why your position is more correct than the opposing idea.

Where to put a counterargument

Can be placed within the introductory paragraph to create a contrast for the thesis statement.

May consist of a whole paragraph that acknowledges the opposing view and then refutes it.

- Can be one sentence acknowledgements of other opinions followed by a refutation.

Why use a counterargument?

Some students worry that using a counterargument will take away from their overall argument, but a counterargument may make an essay more persuasive because it shows that the writer has considered multiple sides of the issue. Barnet and Bedau (2005) propose that critical thinking is enhanced through imagining both sides of an argument. Ultimately, an argument is strengthened through a counterargument.

Examples of the counterargument structure

- Argument against smoking on campus: Admittedly, many students would like to smoke on campus. Some people may rightly argue that if smoking on campus is not illegal, then it should be permitted; however, second-hand smoke may cause harm to those who have health issues like asthma, possibly putting them at risk.

- Argument against animal testing: Some people argue that using animals as test subjects for health products is justifiable. To be fair, animal testing has been used in the past to aid the development of several vaccines, such as small pox and rabies. However, animal testing for beauty products causes unneeded pain to animals. There are alternatives to animal testing. Instead of using animals, it is possible to use human volunteers. Additionally, Carl Westmoreland (2006) suggests that alternative methods to animal research are being developed; for example, researchers are able to use skin constructed from cells to test cosmetics. If alternatives to animal testing exist, then the practice causes unnecessary animal suffering and should not be used.

Harvey, G. (1999). Counterargument. Retrieved from writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/counter- argument

Westmoreland, C. (2006; 2007). “Alternative Tests and the 7th Amendment to the Cosmetics Directive.” Hester, R. E., & Harrison, R. M. (Ed.) Alternatives to animal testing (1st Ed.). Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry.

Barnet, S., Bedau, H. (Eds.). (2006). Critical thinking, reading, and writing . Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Contributor: Nathan Lachner

How to Write a Counter Argument (Step-by-Step Guide)

Have you been asked to include a counter argument in an essay you are writing? Unless you are already an experienced essay writer, you may have no idea where to even start. We're here to help you tackle your counter argument like a pro.

What Is a Counter Argument?

A counter argument is precisely what it sounds like — an argument that offers reasons to disagree with an essay's thesis statement. As you are writing your essay, you will likely pen multiple supporting arguments that outline precisely why readers should logically agree with the thesis. In a counter argument paragraph, you show that you also understand common reasons to believe differently.

In any given essay, you may write one or more counter arguments — and then, frequently, immediately refute them. Whether you are required to include a counter argument or you simply want to, always include:

- A simple statement explaining the counter argument. As it will likely follow paragraphs in which you fleshed out your argument, this can start with words like "Some people are concerned that", or "critics say", or "On the other hand".

- Then include further reasoning, data, or statistics.

- Following this, you will want to discredit the counter argument immediately.

Why Include a Counter Argument?

Including a counter argument (or multiple, for that matter) in an essay may be required, but even in cases where it is not, mentioning at least one counter argument can make your essay much stronger. You may, at first glance, believe that you are undermining yourself and contradicting your thesis statement. That's not true at all. By including a counter argument in your essay, you show that:

- You have done your research and are intimately familiar with each aspect of your thesis, including opposition to it.

- You have arrived at your conclusion through the power of reason, and without undue bias.

- You do not only blindly support your thesis, but can also deal with opposition to it.

In doing so, your essay will become much more reasoned and logical, and in practical terms, this likely means that you can count on a higher grade.

How To Write a Counter Argument (Step-by-Step Guide)

You have been laboring over your essay for a while, carefully researching each aspect of your thesis and making strong arguments that aim to persuade the reader that your view is the correct one — or at least that you are a solid writer who understands the subject matter and deserves a good grade for your efforts.

If you are passionate about the topic in question, it can be hard to decide how to incorporate a counter argument. Here's how to do it, step-by-step:

1. Brainstorm

You have already researched your topic, so you know on what grounds people most frequently oppose your argument. Write them down. Pick one, or a few, that you consider to be important and interesting. Formulate the counter argument as if you were on the opposing side.

2. Making the Transition

Your counter argument paragraph or paragraphs differ from the rest of your essay, so you will want to introduce a counter argument with a transition. Common ways to do this are to introduce your counter argument with phrases like:

- Admittedly, conversely, however, nevertheless, or although.

- Opponents would argue that...

- Common concerns with this position are...

- Critics say that...

3. Offering Evidence

Flesh the counter argument out by offering evidence — of the fact that people hold that position (where possible, quote a well-known opponent), as well as reasons why. Word your counter argument in such a way that makes it clear that you have carefully considered the position, and are not simply belittling it. This portion of your counter argument will require doing additional research in most cases.

4. Refute the Counter Argument

You are still arguing in favor of your main thesis. You will, therefore, not just want to describe the opposing side and leave it at that — you will also thoughtfully want to show why the opposing argument is not valid, in your opinion, and you will want to include evidence here, as well.

5. Restate Your Argument

After refuting your counter argument, you can go ahead and restate your argument. Why should people believe what you have to say, despite any opposition?

How To Write A Good Counter Argument

As you're writing a counter argument, you might run into some difficulties if you fervently believe in the truth of your argument. Indeed, in some cases, your argument may appear to you to be so obvious that you don't understand why anyone could think differently.

To help you write a good counter argument, keep in mind that:

- You should never caricature the opposing viewpoint. Show that you deeply understand it, instead.

- To do this, it helps if you validate legitimate concerns you find in an opponent's point of view.

- This may require quite a bit of research, including getting into the opposing side's mindset.

- Refute your counter argument with compassion, and not smugly.

Examples of Counter Arguments with Refutation

Still not sure? No worries; we have you covered. Take a look at these examples:

- Many people have argued that a vaccine mandate would strip people of their individual liberties by forcing them to inject foreign substances into their bodies. While this is, in a sense, true, the option of remaining unvaccinated likewise forces other people to be exposed to this virus; thereby potentially stripping them of the most important liberty of all — the liberty to stay alive.

- The concern has been raised that the death penalty could irreversibly strip innocent people of their lives. The answer to this problem lies in raising the bar for death penalty sentences by limiting them to only those cases in which no question whatsoever exists that the convicted party was truly guilty. Modern forensic science has made this infinitely easier.

In short, you'll want to acknowledge that other arguments exist, and then refute them. The tone in which you do so depends on your goal.

What is a counter argument in a thesis?

A counter argument is one that supports the opposing side. In an essay, it shows that you understand other viewpoints, have considered them, and ultimately dismissed them.

Where do I place the counter argument in an essay?

Place the counter argument after your main supporting arguments.

How long should the counter argument be?

It may be a single paragraph or multiple, depending on how important you believe the counter argument to be and the length of the essay.

What is the difference between a counter argument and a rebuttal?

A counter argument describes the opposing side in some detail before it is refuted. In a rebuttal, you may simply oppose the opposition.

Related posts:

- How to Write an Effective Claim (with Examples)

- How To Write A Movie Title In An Essay

- How to Write a D&D Campaign (Step-by-Step)

- Bean Counters - Meaning, Origin and Usage

- I Beg to Differ - Meaning, Origin and Usage

- Bone of Contention - Meaning, Usage and Origin

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

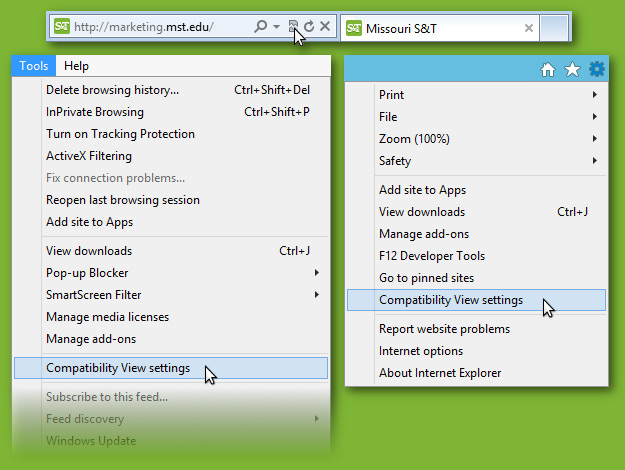

Your version of Internet Explorer is either running in "Compatibility View" or is too outdated to display this site. If you believe your version of Internet Explorer is up to date, please remove this site from Compatibility View by opening Tools > Compatibility View settings (IE11) or clicking the broken page icon in your address bar (IE9, IE10)

Missouri S&T Missouri S&T

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- writingcenter.mst.edu

- Online Resources

- Writing Guides

- Counter Arguments

Writing and Communication Center

- 314 Curtis Laws Wilson Library, 400 W 14th St Rolla, MO 65409 United States

- (573) 341-4436

- [email protected]

Counter Argument

One way to strengthen your argument and demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the issue you are discussing is to anticipate and address counter arguments, or objections. By considering opposing views, you show that you have thought things through, and you dispose of some of the reasons your audience might have for not accepting your argument. Ask yourself what someone who disagrees with you might say in response to each of the points you’ve made or about your position as a whole.

If you can’t immediately imagine another position, here are some strategies to try:

- Do some research. It may seem to you that no one could possibly disagree with the position you are taking, but someone probably has. Look around to see what stances people have and do take on the subject or argument you plan to make, so that you know what environment you are addressing.

- Talk with a friend or with your instructor. Another person may be able to play devil’s advocate and suggest counter arguments that haven’t occurred to you.

- Consider each of your supporting points individually. Even if you find it difficult to see why anyone would disagree with your central argument, you may be able to imagine more easily how someone could disagree with the individual parts of your argument. Then you can see which of these counter arguments are most worth considering. For example, if you argued “Cats make the best pets. This is because they are clean and independent,” you might imagine someone saying “Cats do not make the best pets. They are dirty and demanding.”

Once you have considered potential counter arguments, decide how you might respond to them: Will you concede that your opponent has a point but explain why your audience should nonetheless accept your argument? Or will you reject the counterargument and explain why it is mistaken? Either way, you will want to leave your reader with a sense that your argument is stronger than opposing arguments.

Two strategies are available to incorporate counter arguments into your essay:

Refutation:

Refutation seeks to disprove opposing arguments by pointing out their weaknesses. This approach is generally most effective if it is not hostile or sarcastic; with methodical, matter-of-fact language, identify the logical, theoretical, or factual flaws of the opposition.

For example, in an essay supporting the reintroduction of wolves into western farmlands, a writer might refute opponents by challenging the logic of their assumptions:

Although some farmers have expressed concern that wolves might pose a threat to the safety of sheep, cattle, or even small children, their fears are unfounded. Wolves fear humans even more than humans fear wolves and will trespass onto developed farmland only if desperate for food. The uninhabited wilderness that will become the wolves’ new home has such an abundance of food that there is virtually no chance that these shy animals will stray anywhere near humans.

Here, the writer acknowledges the opposing view (wolves will endanger livestock and children) and refutes it (the wolves will never be hungry enough to do so).

Accommodation:

Accommodation acknowledges the validity of the opposing view, but argues that other considerations outweigh it. In other words, this strategy turns the tables by agreeing (to some extent) with the opposition.

For example, the writer arguing for the reintroduction of wolves might accommodate the opposing view by writing:

Critics of the program have argued that reintroducing wolves is far too expensive a project to be considered seriously at this time. Although the reintroduction program is costly, it will only become more costly the longer it is put on hold. Furthermore, wolves will help control the population of pest animals in the area, saving farmers money on extermination costs. Finally, the preservation of an endangered species is worth far more to the environment and the ecological movement than the money that taxpayers would save if this wolf relocation initiative were to be abandoned.

This writer acknowledges the opposing position (the program is too expensive), agrees (yes, it is expensive), and then argues that despite the expense the program is worthwhile.

Some Final Hints

Don’t play dirty. When you summarize opposing arguments, be charitable. Present each argument fairly and objectively, rather than trying to make it look foolish. You want to convince your readers that you have carefully considered all sides of the issues and that you are not simply attacking or caricaturing your opponents.

Sometimes less is more. It is usually better to consider one or two serious counter arguments in some depth, rather than to address every counterargument.

Keep an open mind. Be sure that your reply is consistent with your original argument. Careful consideration of counter arguments can complicate or change your perspective on an issue. There’s nothing wrong with adopting a different perspective or changing your mind, but if you do, be sure to revise your thesis accordingly.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Responding to Counterarguments

Basics of counterarguments.

When constructing an argument, it is important to consider any counterarguments a reader might make. Acknowledging the opposition shows that you are knowledgeable about the issue and are not simply ignoring other viewpoints. Addressing counterarguments also gives you an opportunity to clarify and strengthen your argument, helping to show how your argument is stronger than other arguments.

Incorporating counterarguments into your writing can seem counterintuitive at first, and some writers may be unsure how to do so. To help you incorporate counterarguments into your argument, we recommend following the steps: (a) identify, (b) investigate, (c) address, and (d) refine.

Identify the Counterarguments

First you need to identify counterarguments to your own argument. Ask yourself, based on your argument, what might someone who disagrees counter in response? You might also discover counterarguments while doing your research, as you find authors who may disagree with your argument.

For example, if you are researching the current opioid crisis in the United States, your argument might be: State governments should allocate part of the budget for addiction recovery centers in communities heavily impacted by the opioid crisis . A few counterarguments might be:

- Recovery centers are not proven to significantly help people with addiction.

- The state’s money should go to more pressing concerns such as...

- Establishing and maintaining a recovery center is too costly.

- Addicts are unworthy of assistance from the state.

Investigate the Counterarguments

Analyze the counterarguments so that you can determine whether they are valid. This may require assessing the counterarguments with the research you already have or by identifying logical fallacies . You may also need to do additional research.

In the above list, the first three counterarguments can be researched. The fourth is a moral argument and therefore can only be addressed in a discussion of moral values, which is usually outside the realm of social science research. To investigate the first, you could do a search for research that studies the effectiveness of recovery centers. For the second, you could look at the top social issues in states around the country. Is the opioid crisis the main concern or are there others? For the third, you could look for public financial data from a recovery center or interview someone who works at one to get a sense of the costs involved.

Address the Counterarguments

Address one or two counterarguments in a rebuttal. Now that you have researched the counterarguments, consider your response. In your essay, you will need to state and refute these opposing views to give more credence to your argument. No matter how you decide to incorporate the counterargument into your essay, be sure you do so with objectivity, maintaining a formal and scholarly tone .

Considerations when writing:

- Will you discredit the counteragument by bringing in contradictory research?

- Will you concede that the point is valid but that your argument still stands as the better view? (For example, perhaps it is very costly to run a recovery center, but the societal benefits offset that financial cost.)

- Placement . You can choose to place the counterargument toward the beginning of the essay, as a way to anticipate opposition, or you can place it toward the end of the essay, after you have solidly made the main points of your argument. You can also weave a counterargument into a body paragraph, as a way to quickly acknowledge opposition to a main point. Which placement is best depends on your argument, how you’ve organized your argument, and what placement you think is most effective.

- Weight . After you have addressed the counterarguments, scan your essay as a whole. Are you spending too much time on them in comparison to your main points? Keep in mind that if you linger too long on the counterarguments, your reader might learn less about your argument and more about opposing viewpoints instead.

Refine Your Argument

Considering counterarguments should help you refine your own argument, clarifying the relevant issues and your perspective. Furthermore, if you find yourself agreeing with the counterargument, you will need to revise your thesis statement and main points to reflect your new thinking.

Templates for Responding to Counterarguments

There are many ways you can incorporate counterarguments, but remember that you shouldn’t just mention the counterargument—you need to respond to it as well. You can use these templates (adapted from Graff & Birkenstein, 2009) as a starting point for responding to counterarguments in your own writing.

- The claim that _____ rests upon the questionable assumption that _____.

- X may have been true in the past, but recent research has shown that ________.

- By focusing on _____, X has overlooked the more significant problem of _____.

- Although I agree with X up to a point, I cannot accept the overall conclusion that _____.

- Though I concede that _____, I still insist that _____.

- Whereas X has provided ample evidence that ____, Y and Z’s research on ____ and ____ convinces me that _____ instead.

- Although I grant that _____, I still maintain that _____.

- While it is true that ____, it does not necessarily follow that _____.

Graff, G., & Birkenstein, C. (2009). They say/I say: The moves that matter in academic writing (2 nd ed.). Norton.

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Addressing Assumptions

- Next Page: Revising

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

21 Argument, Counterargument, & Refutation

In academic writing, we often use an Argument essay structure. Argument essays have these familiar components, just like other types of essays:

- Introduction

- Body Paragraphs

But Argument essays also contain these particular elements:

- Debatable thesis statement in the Introduction

- Argument – paragraphs which show support for the author’s thesis (for example: reasons, evidence, data, statistics)

- Counterargument – at least one paragraph which explains the opposite point of view

- Concession – a sentence or two acknowledging that there could be some truth to the Counterargument

- Refutation (also called Rebuttal) – sentences which explain why the Counterargument is not as strong as the original Argument

Consult Introductions & Titles for more on writing debatable thesis statements and Paragraphs ~ Developing Support for more about developing your Argument.

Imagine that you are writing about vaping. After reading several articles and talking with friends about vaping, you decide that you are strongly opposed to it.

Which working thesis statement would be better?

- Vaping should be illegal because it can lead to serious health problems.

Many students do not like vaping.

Because the first option provides a debatable position, it is a better starting point for an Argument essay.

Next, you would need to draft several paragraphs to explain your position. These paragraphs could include facts that you learned in your research, such as statistics about vapers’ health problems, the cost of vaping, its effects on youth, its harmful effects on people nearby, and so on, as an appeal to logos . If you have a personal story about the effects of vaping, you might include that as well, either in a Body Paragraph or in your Introduction, as an appeal to pathos .

A strong Argument essay would not be complete with only your reasons in support of your position. You should also include a Counterargument, which will show your readers that you have carefully researched and considered both sides of your topic. This shows that you are taking a measured, scholarly approach to the topic – not an overly-emotional approach, or an approach which considers only one side. This helps to establish your ethos as the author. It shows your readers that you are thinking clearly and deeply about the topic, and your Concession (“this may be true”) acknowledges that you understand other opinions are possible.

Here are some ways to introduce a Counterargument:

- Some people believe that vaping is not as harmful as smoking cigarettes.

- Critics argue that vaping is safer than conventional cigarettes.

- On the other hand, one study has shown that vaping can help people quit smoking cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then go on to explain more about this position; you would give evidence here from your research about the point of view that opposes your own opinion.

Here are some ways to begin a Concession and Refutation:

- While this may be true for some adults, the risks of vaping for adolescents outweigh its benefits.

- Although these critics may have been correct before, new evidence shows that vaping is, in some cases, even more harmful than smoking.

- This may have been accurate for adults wishing to quit smoking; however, there are other methods available to help people stop using cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then continue your Refutation by explaining more reasons why the Counterargument is weak. This also serves to explain why your original Argument is strong. This is a good opportunity to prove to your readers that your original Argument is the most worthy, and to persuade them to agree with you.

Activity ~ Practice with Counterarguments, Concessions, and Refutations

A. Examine the following thesis statements with a partner. Is each one debatable?

B. Write your own Counterargument, Concession, and Refutation for each thesis statement.

Thesis Statements:

- Online classes are a better option than face-to-face classes for college students who have full-time jobs.

- Students who engage in cyberbullying should be expelled from school.

- Unvaccinated children pose risks to those around them.

- Governments should be allowed to regulate internet access within their countries.

Is this chapter:

…too easy, or you would like more detail? Read “ Further Your Understanding: Refutation and Rebuttal ” from Lumen’s Writing Skills Lab.

Note: links open in new tabs.

reasoning, logic

emotion, feeling, beliefs

moral character, credibility, trust, authority

goes against; believes the opposite of something

ENGLISH 087: Academic Advanced Writing Copyright © 2020 by Nancy Hutchison is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, counterarguments – rebuttal – refutation.

- © 2023 by Roberto León - Georgia College & State University

Ignoring what your target audience thinks and feels about your argument isn't a recipe for success. Instead, engage in audience analysis : ask yourself, "How is your target audience likely to respond to your propositions? What counterarguments -- arguments about your argument -- will your target audience likely raise before considering your propositions?"

Counterargument Definition

C ounterargument refers to an argument given in response to another argument that takes an alternative approach to the issue at hand.

C ounterargument may also be known as rebuttal or refutation .

Related Concepts

Audience Awareness ; Authority (in Speech and Writing) ; Critical Literacy ; Ethos ; Openness ; Researching Your Audience

Guide to Counterarguments in Writing Studies

Counterarguments are a topic of study in Writing Studies as

- Rhetors engage in rhetorical reasoning : They analyze the rebuttals their target audiences may have to their claims , interpretations , propositions, and proposals

- Rhetors may develop counterarguments by questioning a rhetor’s backing , data , qualifiers, and/or warrants

- Rhetors begin arguments with sincere summaries of counterarguments

- a strategy of Organization .

Learning about the placement of counterarguments in Toulmin Argument , Arisotelian Argument , and Rogerian Argument will help you understand when you need to introduce counterarguments and how thoroughly you need to address them.

Why Do Counterarguments Matter?

If your goal is clarity and persuasion, you cannot ignore what your target audience thinks, feels, and does about the argument. To communicate successfully with audiences, rhetors need to engage in audience analysis : they need to understand the arguments against their argument that the audience may hold.

Imagine that you are scrolling through your social media feed when you see a post from an old friend. As you read, you immediately feel that your friend’s post doesn’t make sense. “They can’t possibly believe that!” you tell yourself. You quickly reply “I’m not sure I agree. Why do you believe that?” Your friend then posts a link to an article and tells you to see for yourself.

There are many ways to analyze your friend’s social media post or the professor’s article your friend shared. You might, for example, evaluate the professor’s article by using the CRAAP Test or by conducting a rhetorical analysis of their aims and ethos . After engaging in these prewriting heuristics to get a better sense of what your friend knows and feels about the topic at hand, you may feel more prepared to respond to their arguments and also sense how they might react to your post.

Toulmin Counterarguments

There’s more than one way to counter an argument.

In Toulmin Argument , a counterargument can be made against the writer’s claim by questioning their backing , data , qualifiers, and/or warrants . For example, let’s say we wrote the following argument:

“Social media is bad for you (claim) because it always (qualifier) promotes an unrealistic standard of beauty (backing). In this article, researchers found that most images were photoshopped (data). Standards should be realistic; if they are not, those standards are bad (warrant).”

Besides noting we might have a series of logical fallacies here, counterarguments and dissociations can be made against each of these parts:

- Against the qualifier: Social media does not always promote unrealistic standards.

- Against the backing : Social media presents but does not promote unrealistic standards.

- Against the data : This article focuses on Instagram; these findings are not applicable to Twitter.

- Against the warrant : How we approach standards matters more than the standards themselves; standards do not need to be realistic, but rather we need to be realistic about how we approach standards.

In generating and considering counterarguments and conditions of rebuttal, it is important to consider how we approach alternative views. Alternative viewpoints are opportunities not only to strengthen and contrast our own arguments with those of others; alternative viewpoints are also opportunities to nuance and develop our own arguments.

Let us continue to look at our social media argument and potential counterarguments. We might prepare responses to each of these potential counterarguments, anticipating the ways in which our audience might try to shift how we frame this situation. However, we might also concede that some of these counterarguments actually have good points.

For example, we might still believe that social media is bad, but perhaps we also need to consider more about

- What factors make it worse (nuance the qualifier)?

- Whether or not social media is a neutral tool or whether algorithms take advantage of our baser instincts (nuance the backing )

- Whether this applies to all social media or whether we want to focus on just one social media platform (nuance the data )

- How should we approach social standards (nuance the warrant )?

Identifying counterarguments can help us strengthen our arguments by helping us recognize the complexity of the issue at hand.

Neoclassical Argument – Aristotelian Argument

Learn how to compose a counterargument passage or section.

While Toulmin Argument focuses on the nuts and bolts of argumentation, a counterargument can also act as an entire section of an Aristotelian Argument . This section typically comes after you have presented your own lines of argument and evidence .

This section typically consists of two rhetorical moves :

Examples of Counterarguments

By introducing counterarguments, we show we are aware of alternative viewpoints— other definitions, explanations, meanings, solutions, etc. We want to show that we are good listeners and aren’t committing the strawman fallacy . We also concede some of the alternative viewpoints that we find most persuasive. By making concessions, we can show that we are reasonable ( ethos ) and that we are listening . Rogerian Argument is an example of building listening more fully into our writing.

Using our social media example, we might write:

I recognize that in many ways social media is only as good as the content that people upload to it. As Professor X argues, social media amplifies both the good and the bad of human nature.

Once we’ve shown that we understand and recognize good arguments when we see them, we put forward our response to the counterclaim. In our response, we do not simply dismiss alternative viewpoints, but provide our own backing, data, and warrants to show that we, in fact, have the more compelling position.

To counter Professor X’s argument, we might write:

At the same time, there are clear instances where social media amplifies the bad over the good by design. While content matters, the design of social media is only as good as the people who created it.

Through conceding and countering, we can show that we recognize others’ good points and clarify where we stand in relation to others’ arguments.

Counterarguments and Organization

Learn when and how to weave counterarguments into your texts.

As we write, it is also important to consider the extent to which we will respond to counterarguments. If we focus too much on counterarguments, we run the risk of downplaying our own contributions. If we focus too little on counterarguments, we run the risk of seeming aloof and unaware of reality. Ideally, we will be somewhere in between these two extremes.

There are many places to respond to counterarguments in our writing. Where you place your counterarguments will depend on the rhetorical situation (ex: audience , purpose, subject ), your rhetorical stance (how you want to present yourself), and your sense of kairos . Here are some common choices based on a combination of these rhetorical situation factors:

- If a counterargument is well-established for your audience, you may want to respond to that counterargument earlier in your essay, clearing the field and creating space for you to make your own arguments. An essay about gun rights, for example, would need to make it clear very quickly that it is adding something new to this old debate. Doing so shows your audience that you are very aware of their needs.

- If a counterargument is especially well-established for your audience and you simply want to prove that it is incorrect rather than discuss another solution, you might respond to it point by point, structuring your whole essay as an extended refutation. Fact-checking and commentary articles often make this move. Responding point by point shows that you take the other’s point of view seriously.

- If you are discussing something relatively unknown or new to your audience (such as a problem with black mold in your dormitory), you might save your response for after you have made your points. Including alternative viewpoints even here shows that you are aware of the situation and have nothing to hide.

Whichever you choose, remember that counterarguments are opportunities to ethically engage with alternative viewpoints and your audience.

The following questions can guide you as you begin to think about counterarguments:

- What is your argument ? What alternative positions might exist as counterarguments to your argument?

- How can considering counterarguments strengthen your argument?

- Given possible counterarguments, what points might you reconsider or concede?

- To what extent might you respond to counterarguments in your essay so that they can create and respond to the rhetorical situation ?

- Where might you place your counterarguments in your essay?

- What might including counterarguments do for your ethos ?

Recommended Resources

- Sweetland Center for Writing (n.d.). “ How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument? ” University of Michigan.

- The Writing Center (n.d.) “ All About Counterarguments .” George Mason University.

- Lachner, N. (n.d.). “ Counterarguments .” University of Nevada Reno, University Writing and Speaking Center.

- Jeffrey, R. (n.d.). “ Questions for Thinking about Counterarguments .” In M. Gagich and E. Zickel, A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing.

- Kause, S. (2011). “ On the Other Hand: The Role of Antithetical Writing in First Year Composition Courses .” Writing Spaces Vol. 2.

- Burton, G. “ Refutatio .” Silvae Rhetoricae.

Toulmin, S. (1958). The Uses of Argument. Cambridge University Press.

Perelman, C. and Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1971). “The Dissociation of Concepts”; “The Interaction of Arguments,” in The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation (pp. 411-459, 460-508), University of Notre Dame Press.

Mozafari, C. (2018). “Crafting Counterarguments,” in Fearless Writing: Rhetoric, Inquiry, Argument (pp. 333-337), MacMillian Learning

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

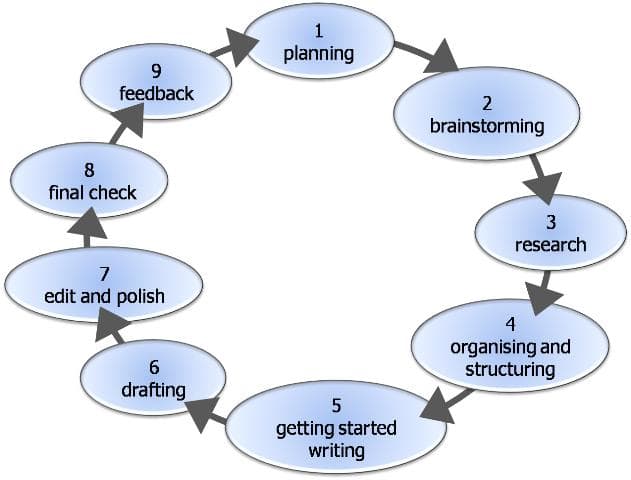

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

Counter Argument in Essay Writing: How to Write a Good Counter Argument

Counterarguments oppose an author’s ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and opinions. These counterarguments are usually found in essays used in class or during specific examinations, thus requiring students to develop this particular skill.

And to develop an effective essay, you must be able to present your views and counter-arguments in a manner that does not leave your audience confused. But for many, this is not the case, and they find it challenging.

But not anymore. This post delves deeper to help you understand a counter-argument and how to write one, among other crucial details.

Here is the explanation.

What Is a Counter Argument

A counter-argument is a logical and rational way to disagree with an opposing viewpoint or assertion. In other words, it is a statement that opposes an argument developed in another article.

These arguments also attempt to disprove or question the validity of the original idea. It is important to note that this type of argument should be used only when there is insufficient evidence supporting the original claim or if you have new evidence.

New Service Alert !!!

We are now taking exams and courses

Further, counterarguments are used in many different situations. For example, if you are preparing for an argumentative essay or speech and need to find arguments against your position, you can use them.

Further, you can use these arguments when debating or in any other type of argument. When you give someone a counter-argument, you show them that there is more than one way to look at the situation and explain why their point of view is not the only one. You are attempting to show that what they say is not necessarily true and that they should consider other options.

Also see: How Do You Write a Toulmin Argumentative Essay

It’s important to note that counterarguments don’t always have to be negative. Sometimes they can be positive but negate the original statement.

How to Write a Good Counter Argument

Good counterarguments are based on solid research and thoughtful analysis. The best way to write a strong counter-argument is to do the following;

Be thorough

You should answer all of the points made by your opponent in their essay and explain why you don’t agree with those points.

For example, if someone says that people shouldn’t eat meat because it is unhealthy and is animal cruelty, you should address both points in your response. Explain the importance of eating meat and how it is not animal cruelty.

Provide enough evidence

In your arguments, include evidence from experts in your field. This will help bolster your credibility and make your view seem more convincing than if you were simply presenting personal opinions or subjective interpretations of facts.

You should clearly state the opposing position, include evidence to support it, and then explain why you disagree with this position based on your research and analysis of the evidence presented.

Be fair and objective

Being fair and objective when writing a counter-argument means that you should not attack the person or group you are writing about. Instead, you should focus on the issue in question. This makes your writing more persuasive to the reader.

It also means explaining why your position is correct, and your opponent’s wrong. You should not present your argument as the only possible or accurate one. Instead, define the several possible positions on an issue, and point out what those positions are.

You should also not ignore any part of your opponent’s position, even if it seems weak or wrong to you. For example, if your opponent states, “War is always bad,” you should acknowledge this and explain by saying, war is bad but sometimes justifiable and thus not always wrong.

Additionally, it would help if you did not misrepresent any position by taking things out of context.

Counter Argument Transition Words

When writing a counter-argument, it is vital to ensure that your argument is well-structured and organized. This means you must have a clear opening paragraph, evidence to support your claims, and a conclusion that summarizes everything.

However, you must use the correct words for your readers to follow your argument. These words are known as transitions, and they help you logically connect your ideas and allow the argument to flow smoothly. These transition words are used to connect one paragraph with another, as well as one sentence with another.

The following is a list of counter-argument transition words that can help you write a better counter-argument in your essay.

Moreover, however, conversely, moreover, nonetheless, on the other hand, although, despite this, nonetheless, on the contrary, yet, still, but, instead, in conclusion, to conclude, to sum up, and likewise.

You can also first, second, and thirdly to show how your points flow.

Counter Argument Sentence Starters

The easiest and most effective way to start a counter-argument sentence is by using inviting and “non-hostile” phrases. These can be phrases or words that you use to reference your opponent’s argument, which shows you have taken time to look at their points.

It is essential to understand that these sentence starters do not necessarily have to be negative or critical but can also be positive. The key is to use them to make your reader appreciate both points but still believe you.

Examples of counter-argument sentence starters can be, I disagree, you are wrong, you are right, would you agree? “Why do you think so?” and “How come?”

Others include;

- What might be some reasons why?

- Are there certain circumstances that would make this accurate?

- How could this not be true?

- What would happen if we did not believe it?

- How accurate is this statement?

Do Synthesis Essays Need a Counter Argument

Synthesis essays require you to have a counter-argument to your thesis, especially in the first paragraph. A synthesis essay is an academic assignment that requires you to combine multiple sources into one coherent paper. When you are writing a synthesis essay, you will include both positive and negative arguments.

You can find multiple sources online or in your local library. Once you have all your information gathered, start by reading through each source and making notes of relevant points to your topic. This will help you see what each source says about the subject and how similar or different they are.

Finally, you should organize your notes and ideas into paragraph form to flow smoothly while making sense. Once this is done, it’s time to write your counter-argument paragraph.

Does an Argumentative Essay Need a Counter Argument

An argumentative essay needs you to have a counter-argument. This is because you are required to write a paper that presents your thesis and then backs it up with evidence, and the counter-argument is a part of this process.

It is the other side of the story. The idea here is that you present an argument but then offer another point of view on the same topic in the counter-argument section. This can be done in many ways, but it should always be backed up by evidence from your research.

An argumentative essay is a piece of writing that presents a position and then defends it with evidence and reasoning. The essay’s purpose is to convince the reader that the author’s point of view is correct. However, it also has the counter-argument section, with responses to an existing idea and clearly shows the alternative point of view.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.7.3: Counter Argument Paragraphs

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 20657

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Counter-Argument Paragraphs

The purpose of a counter argument is to consider (and show that you are considering) perspectives other than your own. A counter-argument tears down other viewpoints; it does not build up your own, which you should do in separate paragraphs.

Placement of Counter-Arguments in an Essay

A counter argument can appear anywhere in the essay, but it most commonly appears:

- As part of your introduction—before you propose your thesis—where the existence of a different view is the motive for your essay. This works if your entire essay will be a counter-argument and you are not building up your own argument.

- As a section or paragraph just after your introduction, in which you lay out the expected reaction or standard position of opposing viewpoints before turning away to develop your own.

- As a quick move within a paragraph, where you imagine a counter-argument not to your main idea but to the sub-idea that the paragraph is arguing or is about to argue.

- As a section or paragraph just before the conclusion of your essay, in which you imagine what someone might object to in what you have argued. (However, this is really too late to be very effective in persuading someone to your position. It only shows you are considering other points of view.

Watch that you don't overdo it. A turn into counter argument here and there will sharpen and energize your essay, but too many such turns will have the reverse effect by obscuring your main idea or suggesting that you're ambivalent about your point of view. At the worst, it can sound like you are contradicting yourself. Writing a lead-in sentence with subordination or concession can help avoid this problem.

Example Counter-Argument

The following paragraph explains an opposing point of view to the writer's position in almost the whole paragraph. Words in bold italics explain the essential component of a counter-argument that a writer is doing in the following sentence(s).

| Considering the many challenges facing K-12 public schools, it’s understandable that many people would be eager to pursue new options. Supporters of school choice point out that under the current public school system, parents with economic means already exercise school choice by moving from areas with failing or dangerous schools to neighborhoods with better, safer schools. Their argument is that school choice would allow all parents the freedom, regardless of income level, to select the school that provides the best education (Chub and Moe). Schools would then have to compete for students by offering higher academic results and greater safety. Schools unable to measure up to the standards of successful schools would fail and possibly close. Activists within the school choice movement can be applauded for seeking to improve public education, but the changes they propose would in fact seriously damage public education as a whole. |

The next paragraph is the counter-argument to the previous paragraph. Notice, however, that this count-argument does have some problems. The writer doesn't distinguish between public and private charter schools and also creates some logical fallacies in the process. Counter-arguments should be logically solid, cite sources, and argue logically.

| One of the biggest dangers of school choice is the power behind large corporations specializing in opening and operating charter schools. Two notable companies are Green Dot, which is the leading public school operator in Los Angeles (Green Dot), and KIPP, which operates 65 schools in 19 different states (KIPP). These companies represent a growing trend of privatization of public schools by large corporations. It is feared that these corporations could grow to a point that public control of education would be lost. Education policy would be left in the hands of entrepreneurial think tanks, corporate boards of directors, and lobbyists who are more interested in profit than educating students (Miller and Gerson). The results of this could be just as bad or worse than what is currently happening in underperforming schools. Education should be left in the hands of professional educators and not business people with MBAs. |

At this point, the writer would then begin to argue their point of view with sub-claims and facts developed in a number of paragraphs to support their thesis.

If a writer is constructing an entire essay as a counter-argument, then the writer will need to fully develop multiple, well-supported arguments against the other point of view. The writer may also want to point out any logical flaws or other errors in the argument that they oppose.

Contributors and Attributions

- Revision, Adaptation, and Original Content. Provided by: Libretexts. License: CC BY-SA 4.0: Attribution.

This page most recently updated on June 6, 2020.

The Study Blog : Tips

8 counter argument examples to help you write a strong essay.

By Evans Oct 26, 2020

A one-sided essay is like a beautiful dish with no flavor. Everyone looks at it, but nobody wants to partake of it. An essay presenting one side of a debate shows that you are not reasonable. Instead of persuading your readers, it ends up feeling like you’re just forcing an opinion on them. How do you change this? How do you make your essay interesting and persuasive? Counter argument! You heard me right. Using the counter argument is one of the best ways that you can strengthen your essay.

Before we proceed further, what exactly is a counter-argument? An academic essay means that you need to come up with a thesis, a strong one at that, and even stronger points that support that particular thesis . You also need to come up with an argument that opposes your thesis. This is what we call a counter-argument. It is basically, an argument that is against your thesis.

Are tight deadlines, clashing assignments, and unclear tasks giving you sleepless nights?

Do not panic, hire a professional essay writer today.

What is the purpose of a counter-argument?

When writing an essay, especially to persuade, you need to put yourself in the shoes of your readers. What are they likely to think about your thesis? How can they possibly argue against it? What questions might they have against the idea you are trying to sell to them? A counter-argument allows you to creatively and wisely respond to these questions. A counter-argument clears any doubts that your reader may have on your argument. It also shows them that you are the bigger person by actually addressing arguments against your thesis.

Counter argument examples

Let’s say your argument is about getting the patient to consent to it, rather than have the doctors decide on it.

A reader might argue: a patient may be too sickly to even consent for euthanasia.

Refutal: you can refute the counter-argument by proving that it is possible to get a patient in the right frame long enough to sign the consent form.

Overprotective parents

Argument: overprotective parents often treat their grown-up children like babies. As a result, these children grow to be very dependent on the parents and unable to make decisions on their own.

Counter-argument: parents have seen more than their children. Protecting them from the problems they encountered saves the children from getting hurt.

Refutal: Though parents think that shielding their grown children protects them from the dangerous world, they only end up protecting children from living. As a result, if such a child makes a mistake, it might be very hard for them to recover from it.

Getting a dog as a pet for young children

Argument: getting a dog as a pet for younger children is not a very good idea as children may not understand how to take care of the dog.

Counter-argument: having a pet teaches the children responsibility.

Rebuttal: While it is true that having a pet can teach kids how to become more responsible, the fact remains that taking care of a pet is a full-time job. A pet is not like a toy that you can discard when tired of it. Young kids may not have the stamina or the time to take care of a pet.

Exposure to technology

Argument: Technology provides children with an amazing learning experience. Children who have been exposed to technology learn pretty first how to deal and respond to different situations better than students who have no exposure to technology.

You may also like: How to write a technology essay: tips, topics, and examples

Counter argument: early exposure to entertainment and violence affects the cognitive skills of a child.

Rebuttal: Although some form of technology may affect the cognitive skills of a child, it doesn’t mean that children should be kept away from technology. There are learning programs that provide a better learning experience as compared to formal education. Doing away with technology is not the answer. The answer is controlling what children are exposed to.

Argument: taking part in elections is not only a right but a responsibility that every citizen should participate in.

Counter-argument: It is better not to vote than vote in a corrupt person.

Rebuttal: While you might feel like not taking part in the voting process keeps you from the guilt of choosing the wrong person, the truth is that you only give other people the right to choose for you. This means that if a corrupt person gets in, you’re still responsible for not voting for a better candidate.

Argument: Smoking should not be allowed on campuses.

Counter-argument: smoking is not illegal, especially to someone above 18 years old. Since it is not illegal, students should be allowed to smoke within the campus vicinity.

Rebuttal: indeed, smoking is not illegal. However, smoking on campus can prove to be fatal especially to students with health issues such as asthma. It is widely known that smoking affects not just the person holding the cigar but everyone else around them. Therefore, to keep students safe, smoking should not be allowed on campus.

Animal testing

Argument: animals should not be used as test subjects.

Counter-argument: animals happen to be the best test method for health products

Rebuttal: While it is true that over the years animals have been used as test subjects, it doesn’t change the fact that these tests often subject animals to excruciating pain. Research shows that there are better alternatives that can be used, thereby saving animals from unnecessary pain.

Cyberbullying

Argument: Cyberbullying is a serious issue and therefore it is very important to understand how to protect yourself from cyberbullies.

Counter-argument: the victims do not need to learn how to protect themselves and use the internet fearfully. The internet should be made secure for every user and all cyberbullying should be put to jail.

Rebuttal: nobody deserves to be afraid while using the internet. However, while it is a very good idea to have all cyberbullies jailed, that remains to be just a dream. This is because almost everyone can be a cyber-bully at one point or another. It, therefore, remains your responsibility to protect yourself and also learn how to handle cyberbullying.

Earn Good Grades Without Breaking a Sweat

✔ We've helped over 1000 students earn better grades since 2017. ✔ 98% of our customers are happy with our service

Final thoughts

As the examples show, a good persuasive essay should contain your thesis statement , a counter-argument, and a rebuttal of the counter-argument. This makes your essay strong, very persuasive, and with a very good flavor.

You may also like: The little secret why your friends are earning better grades

Popular services

The little secret why your friends are earning better grades.

Hire an Expert from our write my essay service and start earning good grades.

Can Someone Write My Paper for Me Online? Yes, We Can!

Research topics

Essay Topics

Popular articles

Six Proven ways to cheat Turnitin with Infographic

Understanding Philosophy of Nursing: Complete Guide With Examples

50+ Collection of the Most Controversial Argumentative Essay Topics

50+ Economics research Topics and Topic Ideas for dissertation

20+ Interesting Sociology research topics and Ideas for Your Next Project

RAISE YOUR HAND IF YOU ARE TIRED OF WRITING COLLEGE PAPERS!

Hire a professional academic writer today.

Each paper you order from us is of IMPECCABLE QUALITY and PLAGIARISM FREE

Use code PPH10 to get 10% discount. Terms and condition apply.

Ready to hire a professional essay writer?

Each paper you receive from us is plagiarism-free and will fetch you a good grade. We are proud to have helped 10,000+ students achieve their academic dreams. Enjoy our services by placing your order today.

Write my paper

Do my assignment

Essay writing help

Research paper help

College homework help

Essay writing guide

College admission essay

Writing a research paper

Paper format for writing

Terms & conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Policy

Money-Back Guarantee

Our services

Copyright © 2017 Paper Per Hour. All rights reserved.

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

| {{item.snippet}} |

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students