- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1 What Is Practice Research and Why Is It Important

- Published: April 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Chapter 1 of Practice Research in the Human Services: A University-Agency Partnership Model discusses the evolving definition of practice research. It highlights the need to identify ways to improve practice in the complex situations that characterize human services, by developing knowledge that emerges directly from everyday practice. Practice research often focuses on the relationships between service providers and service users, between service providers and their managers, between agency-based service providers and community advocacy and support groups, and between agency managers and policymakers. The chapter outlines the “practice” and “research” components of practice research, the role of theory, and the importance of local context in shaping specific approaches to practice research. It provides an overview of the university-agency partnership that provided the platform for carrying out the studies described in the volume, and offers perspectives on the related phenomena associated with learning organizations and evidence-informed practice.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 19 |

| November 2022 | 7 |

| December 2022 | 8 |

| January 2023 | 9 |

| February 2023 | 8 |

| March 2023 | 13 |

| April 2023 | 6 |

| May 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 8 |

| July 2023 | 8 |

| August 2023 | 7 |

| September 2023 | 10 |

| October 2023 | 15 |

| November 2023 | 10 |

| December 2023 | 10 |

| January 2024 | 8 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| March 2024 | 10 |

| April 2024 | 14 |

| May 2024 | 7 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

Published on January 27, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

Table of contents

Types of action research, action research models, examples of action research, action research vs. traditional research, advantages and disadvantages of action research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about action research.

There are 2 common types of action research: participatory action research and practical action research.

- Participatory action research emphasizes that participants should be members of the community being studied, empowering those directly affected by outcomes of said research. In this method, participants are effectively co-researchers, with their lived experiences considered formative to the research process.

- Practical action research focuses more on how research is conducted and is designed to address and solve specific issues.

Both types of action research are more focused on increasing the capacity and ability of future practitioners than contributing to a theoretical body of knowledge.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

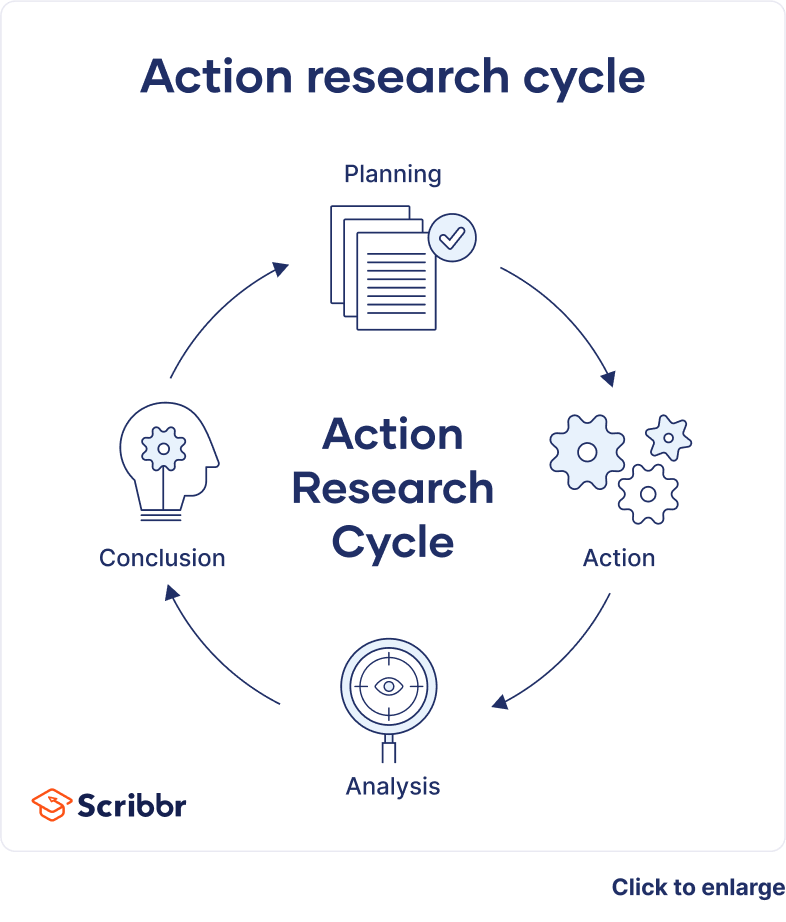

Action research is often reflected in 3 action research models: operational (sometimes called technical), collaboration, and critical reflection.

- Operational (or technical) action research is usually visualized like a spiral following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

- Collaboration action research is more community-based, focused on building a network of similar individuals (e.g., college professors in a given geographic area) and compiling learnings from iterated feedback cycles.

- Critical reflection action research serves to contextualize systemic processes that are already ongoing (e.g., working retroactively to analyze existing school systems by questioning why certain practices were put into place and developed the way they did).

Action research is often used in fields like education because of its iterative and flexible style.

After the information was collected, the students were asked where they thought ramps or other accessibility measures would be best utilized, and the suggestions were sent to school administrators. Example: Practical action research Science teachers at your city’s high school have been witnessing a year-over-year decline in standardized test scores in chemistry. In seeking the source of this issue, they studied how concepts are taught in depth, focusing on the methods, tools, and approaches used by each teacher.

Action research differs sharply from other types of research in that it seeks to produce actionable processes over the course of the research rather than contributing to existing knowledge or drawing conclusions from datasets. In this way, action research is formative , not summative , and is conducted in an ongoing, iterative way.

| Action research | Traditional research | |

|---|---|---|

| and findings | ||

| and seeking between variables | ||

As such, action research is different in purpose, context, and significance and is a good fit for those seeking to implement systemic change.

Action research comes with advantages and disadvantages.

- Action research is highly adaptable , allowing researchers to mold their analysis to their individual needs and implement practical individual-level changes.

- Action research provides an immediate and actionable path forward for solving entrenched issues, rather than suggesting complicated, longer-term solutions rooted in complex data.

- Done correctly, action research can be very empowering , informing social change and allowing participants to effect that change in ways meaningful to their communities.

Disadvantages

- Due to their flexibility, action research studies are plagued by very limited generalizability and are very difficult to replicate . They are often not considered theoretically rigorous due to the power the researcher holds in drawing conclusions.

- Action research can be complicated to structure in an ethical manner . Participants may feel pressured to participate or to participate in a certain way.

- Action research is at high risk for research biases such as selection bias , social desirability bias , or other types of cognitive biases .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.

Action research is focused on solving a problem or informing individual and community-based knowledge in a way that impacts teaching, learning, and other related processes. It is less focused on contributing theoretical input, instead producing actionable input.

Action research is particularly popular with educators as a form of systematic inquiry because it prioritizes reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice. Educators are able to simultaneously investigate an issue as they solve it, and the method is very iterative and flexible.

A cycle of inquiry is another name for action research . It is usually visualized in a spiral shape following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2024, January 12). What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 14, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/action-research/

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th edition). Routledge.

Naughton, G. M. (2001). Action research (1st edition). Routledge.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is an observational study | guide & examples, primary research | definition, types, & examples, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing the Research Paper

Writing in a formal, academic, and technical manner can prove a difficult transition for clinicians turned researchers; however, there are several ways to improve your professional writing skills. This chapter should be considered a collection of tools to consider as you work to articulate and disseminate your research.

Chapter 7: Learning Objectives

This is it! You’re ready to tell the world of the work you’ve done. As you prepare to write your research paper, you’ll be able to

- Discuss the most general components of a research paper

- Articulate the importance of framing your work for the reader using a template based on the research approach

- Identify the major components of a manuscript describing original research

- Identify the major components of a manuscript describing quality improvement projects

- Contrast the specifications of guidelines and protocols

- Identify the major components of a narrative review

Guiding Principles

Although it is wise to identify a potential journal or like avenue as you begin to write up you research, this is not always feasible. For this reason, it is a good idea to have an adequate understanding of the general expectations of what is required of written research articles and manuscripts. Here are some things to keep in mind:

Consider the articles you read

As you begin to research potential research interests, pay close attention to the style of writing found in peer-reviewed and academic journals. You will notice that the ‘tone’ of ‘voice’ is often formal and rarely uses the first-person narrative. You will be expected to develop writing of this caliber in order to be published in a reputable peer-reviewed forum. One of the most difficult concepts for novice researchers to understand is that professional or technical writing is very different from casual or conversational writing. There is little room for anecdotes, opinions, or overly descriptive narratives. Keep your writing succinct and focused.

Keep it simple, silly! (KISS)

Recall when you were first introduced to writing a paper in an early English Composition course. It is likely that you were told that the key components of a paper are the introduction, body, and conclusion. This is truly the foundational structure of any good paper. Consider the following outline for your writing assignments:

Introduction

- Brief overview of the topic which identifies the gap of understanding about a particular topic that you hope to address (why is it important?)

- Statement of problem (what issue are you going to address?)

- Purpose statement/thesis statement (what is the objective of this paper?)

Typically the body of the paper will be broken down into themes or elements outlined in the introduction. Occasionally rather than themes or topics to be addressed, the ‘body’ of the paper will have specific components such as a literature review, methodology, data analysis, discussion, and/or recommendation section. Each of these sections may have specific requirements within that section. Later in this chapter, you will be introduced to specific requirements of different types of research papers.

The body of any paper is the ‘meat and potatoes’ of the work. That is, this is the section wherein you both present and explain your ideas in support of the purpose of the paper (described in the introduction). The body of your paper, regardless of specific structure, is where the majority of your evidentiary base should be included. That is, many of the statements you make in these sections will require substantiation from outside resources. It is vital to include appropriate citations of all references used. To save yourself time, cite and reference correctly as you write. Doing so will help ensure that you stay organized as your work evolves.

Sections such as methods or data analyses, will not require as much substantiation and should be considered very ‘cut and dry’. That is, there will be little to no discussion or interpretation of the evidence here. Results sections, similarly, should be focused on the presentation of results specific to your investigation, including statistical analyses. When reporting results of your work consider the format and whether it makes sense to summarize results in a table, figure, or appendix. The appropriate method will depend on both the type and amount of information that you are trying to convey.

The discussion section is the point at which you should frame your results in the context of your interpretation of the existing literature and how your work addresses the gap in knowledge. You’ll work to substantiate your interpretation by utilizing references to present evidence to support your rational. Pay close attention to your approach as you discuss your results and the impact of your work. Be careful not to make declarative statements if your data does not support a cause-and-effect relationship. Additionally, be careful not to draw inference as a result of bias. That is, use caution in skewing the evidence to support your hypothesis.

The conclusion is exactly that. This is your opportunity to wrap your thoughts up succinctly. A good conclusion will remind the reader of the point or focus of the paper, reiterate the arguments outlined in the body as well as summarize any discussion or recommendations posed in those respective sections, and articulate what the content of the paper added to the knowledge base of the subject. This is not a time to introduce new arguments, concepts, or evidence. The reader should be able to finish the paper understanding the purpose of the paper, the main arguments, and the impact of the work on the subject.

References should be cited correctly in text as well as appropriately formatted at the end of each body of work. The format of your references will depend on the guidelines required of the intended journal or forum you’re submitting to. For example, papers written utilizing the American Psychological Association (APA) formatting standards will include reference pages which are organized on a separate page, titled ‘References’, and organized alphabetically by author surname. If you’re not quite sure of where you’ll be submitting your paper for publication, it may be best to write using APA format; because the references are listed in ascending alphabetical order, adding or removing references during the revision process will be minimally impactful on the designation of subsequent references. Altering your references can then be done once you identify a method of dissemination and review specific guidelines.

Understanding how to present your work can be difficult. It’s one thing to plan and do the research; it’s quite another to put it down on paper in a logical and articulate way. As we discussed in chapters 1 and 2, planning is essential to the success of your research. Similarly, planning the layout of your manuscript will help ensure that you stay both organized and focused. Although most articles can be generalized as having an introduction, body, and conclusion; the specific components within each of those sections varies depending on the approach to research.

Original Research

Although many journals may outline specific requirements for how your manuscript or research paper is to be formatted, there are some generally acceptable formats. One of the most generalizable formats is referred to as IMRaD. IMRaD is an acronym and includes the following elements:

- Introduction- 25%

- Methods- 25%

- Results- 35%

- Discussion/conclusion- 15%

- Clearly state the focus for the work. Provide a brief overview of the issue and the gap in knowledge identified; including both a problem and purpose statement in the context of what is currently understood about the topic. This is where you ‘reel’ the reader in and also highlight the important themes which are consistently addressed in the existing literature.

- General and specific approaches

- Participant selection/randomization

- Instrumentation/measurements utilized

- Here is where you report specific findings and outcomes of your work. There should be very little discussion in this section. Rather, you should present your results and comment, briefly, on how this may relate to the existing literature and state the bottom line. That is, what do these findings suggest. These succinct comments should frame the lens of the discussion section.

- In the discussion section you can further elaborate on your interpretation, based in the evidence, of how your findings relate to what other researchers have found. You can discuss flaws in your work as well as suggestions for direction of future research. You should address each of the main points you presented in your introduction section(s).

QI Projects

When presenting your QI project; a systematic reporting tool, such as the SQUIRE method , is helpful to ensure that you appropriately present the information in a way that both adds to the understanding of the problem as well as a descriptive approach to solving the issue.

SQUIRE Method

Titling your QI project

- Your title should indicate that the project addresses a specific initiative to improve healthcare.

Example of QI Project title

Quality Improvement Initiative to Standardize High Flow Nasal Cannula for Bronchiolitis: Decreases Hospital and Intensive Care Stay

- Addresses specific initiative to improve healthcare

- Directly identifies the bounds and focus of the project

- Provide enough information to help with searching and indexing of your work

- Summarize all key findings in the format required by the publication. Typical sections include background (including statement of the problem), methods, intervention, results, and conclusion

- Include a description on the nature and significance of the problem

- Summary of what is currently understood about the problem

- Overview of framework, model, concepts and/or theory used to explain the problem. Include an assumptions, delimitations, or definitions used to both describe the problem as well as develop the intervention and why the intervention was intended to work.

- Describe the purpose of the project

- Describe the contextual elements relevant to both the problem and intervention (e.g. environmental factors contributing to the problem)

- Include team-based approach, if applicable

- Describe the approach used to assess the impact of the intervention as well as what approach was used to evaluate/assess the intervention

- What tools did you use to study both the process and intervention and why?

- What tools are in place for ongoing assessment of efficacy of the project?

- How is completeness and accuracy of the data measured?

- Describe the quantitative/qualitative methods used to draw inference from the data collected

- Describe how ethical considerations were addressed and whether the project was overseen by an Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Initial steps of intervention and evolution over time; including modifications to the intervention or project

- Details of the process measures and outcome

- Key findings including relevance to the rational and specific aims

- Strengths of the projects

- Nature of the association between intervention and outcome

- Comparison of the findings with those of other publications

- Impact of the project

- Reasons for differences between observed and anticipated outcomes; include contextual rationale

- Costs and strategic implications

- Limits to the generalizability of the work

- Factors that may have limited internal validity (e.g. confounding variables, bias, design)

- Efforts made to minimize or adjust for limitations

- Usefulness of the work

- Sustainability

- Potential for application to other contexts

- Implications for practice and further study

- Suggested next steps

- This section would be included if you received funding for the projects.

Narrative Reviews

As mentioned in chapter 2, development of either guidelines or protocols is an intensive process which often requires a systematic team approach to ensure that the scope and purpose of the work is as generalizable as possible. The best approach for the development of guidelines can be found by reviewing the World Health Organization handbook for guideline development .

Presenting a narrative review of a topic is an excellent way to contribute to the knowledge base on a particular subject as well as to provide framework for development of a protocol or guideline. The elements included in presentation of a narrative review are not all that different from those of traditional research studies; however, there are some notable differences. Here is a brief outline of what should be included in a quality narrative review, adapted from Green, Johnson, and Adams (2006) and Ferarri (2015):

- Objective: State the purpose of the paper

- Background: Describe why the paper is being written; include problem statement and/or research question

- Methods: Include methods used to conduct the review; including those used to evaluate articles for inclusion into your work

- Discussion: Frame the findings of the review in the context of the problem

- Conclusion: State what new information your work contributes as a result of your review and synthesis

- Key words: List MeSH terms and words that may help organize and/or locate your work

- Clearly state the focus for the work. Provide a brief overview of the issue and the gap in knowledge identified; including both a problem and purpose statement

- Provide an overview of how information related to the review was located. This includes what terms were searched and where as well as why studies were included in your review. Delimiting your search is important to describe the scope of the review

- Themes or constructs should be identified throughout the review of the literature and arranged in a way such that the discussion of the theme and the link to the evidence should directly address the purpose of your inquiry

- What sets a review apart from an annotated bibliography is synthesis of the evidence around major points identified consistently throughout the research (i.e. themes). Both consensus and diverging approaches should be included in the discussion of the evidence. This should not be considered simply a comparison of the existing evidence, but should be framed through the lens of the author’s interpretation of that evidence.

- Tie back to the purpose as well as the major conclusions identified in the review. No new information should be discussed here, apart from suggestions for future research opportunities

An extremely important part of disseminating your work is ensuring that you have correctly attributed thoughts and content that you did not create. Depending on the nature of your research, discipline, or intended publication, the format by which you list your references or outline resources utilized may differ. Regardless of referencing formatting guidelines, it is imperative to keep your references organized as you draft different iterations of your work. For example, it may be easier to draft your work utilizing American Psychological Association (APA) formatting guidelines, which arrange references by author’s last name, in ascending alphabetical order, than in other formats which require that references be numbered in order of appearance in the text. As you add, delete, or rearrange references within the text of your manuscript, it may be both difficult and time consuming to constantly re-number each of your references. Note : Depending on the reference guidelines for your intended journal, you may be required to list the abbreviated names of journals. Finding this information can be difficult. Consider this resource for locating and identifying how best to list journal titles within a reference.

Key Takeaways

- Identifying an appropriate outline for the research approach you selected is essential to developing a publishable manuscript

- Academic writing is formal in both voice and tone

- Academic writing is technical

- Refrain from the use of the first person narratives, including anecdotes, or interjecting your unsubstantiated opinion

- All research papers have an introduction, body, and conclusion

- Specific components of the introduction and body will vary depending on the approach

- Proper citation, referencing, or attributing must be included in all work

Green, B.N., Johnson, C.D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 3 (5), 101-117.

Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. The European Medical Writers Association, 2 4(4), 230-235. doi: 10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

SQUIRE. (2017). Explanation and elaboration of SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines . SQUIRE. http://www.squire-statement.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&pageId=504

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO handbook for guideline development, 2nd Ed . World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145714

Practical Research: A Basic Guide to Planning, Doing, and Writing Copyright © by megankoster. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Practical Relevance, Usefulness, and Effectiveness

- First Online: 14 July 2022

Cite this chapter

- Edgar Göll 10

Part of the book series: Zukunft und Forschung ((ZUFORSCH))

305 Accesses

Futures research always involves a host of individual and collective actors, each with their own expectations and needs (see “Understanding the Type, Role, and Specificity of the Research Audience”). For instance, in contract research funders put a premium on practical relevance and utility. Generally, future researchers should work to ensure that their results are impactful by considering possible follow-on measures as they design the study (see “Aligning Research with Ambitions for Action”). Ultimately, however, it is the findings that determine whether the research objectives have actually been achieved. Through the application of targeted models (“Theoretical Foundation”), concepts (“Operational Quality”), and methods (“Method Selection”), future researchers can produce well-founded results that add to the knowledge base (“Scientific Relevance”). Yet findings are practically relevant, useful, and effective only if they meet the knowledge requirements of the funder and are utilizable by all the pertinent actors.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Further Reading

Bell, W. (2003). Foundations of futures studies (vol. 1). Transaction Publishers.

Google Scholar

Bortz, J., & Döring, N. (1995). Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation für Sozialwissenschaftler (chap. 3, 95–126). Springer.

Bourdieu, P. (1993). Soziologische Fragen . Edition Suhrkamp.

Grunwald, A. (2009). Wovon ist die Zukunftsforschung eine Wissenschaft? In R. Popp & E. Schüll (Eds.), Zukunftsforschung und Zukunftsgestaltung: Beiträge aus Wissenschaft und Praxis , 25–35. Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Kreibich, R. (2008). Zukunftsforschung für die gesellschaftliche Praxis . IZT—Institut für Zukunftsstudien und Technologiebewertung. ArbeitsBericht no. 29. Berlin.

Martino, J. P. (1983). Technological forecasting for decision making (chap. 17–19, 226–283). North-Holland.

Neuhaus, C. (2006). Zukunft im Management: Orientierungen für das Management von Ungewissheit in strategischen Prozessen . Carl Auer.

Rust, H. (2008). Zukunftsillusionen: Kritik der Trendforschung . VS Verlag.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute for Future Studies and Technology Assessment (IZT), Berlin, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Edgar Göll .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Research Forum on Public Safety and Security, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Lars Gerhold

VDI Technologiezentrum GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany

Dirk Holtmannspötter

FUTURESAFFAIRS, Büro für aufgeklärte Zukunftsforschung, Berlin, Germany

Christian Neuhaus

Salzburg University of Applied Sciences, Salzburg, Austria

Elmar Schüll

Foresightlab, Berlin, Germany

Beate Schulz-Montag

Z_punkt GmbH, Berlin, Germany

Karlheinz Steinmüller

Innovations- und Zukunftsforschung, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Göll, E. (2022). Practical Relevance, Usefulness, and Effectiveness. In: Gerhold, L., et al. Standards of Futures Research. Zukunft und Forschung. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-35806-8_14

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-35806-8_14

Published : 14 July 2022

Publisher Name : Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-35805-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-35806-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Imperial College London Imperial College London

Latest news.

Inspiration flourishes at the Great Exhibition Road Festival 2024

King’s Birthday Honours for Imperial academics

Imperial students’ crop preservation startup wins 2024 Ideas to Impact Challenge

- Centre for Higher Education Research and Scholarship

- Research and Innovation

- Educational research methods

- Before you start

Practical considerations

Before you start - Practical considerations

Careful consideration of the practical and ethical considerations involved in carrying out a piece of educational research needs to take place at the outset. Although this is something of an iterative process and some practical issues may not emerge or pose a potential challenge until after the research process has started, time spent attending to the practical aspects early on will help minimise complications and will contribution to the identification of an appropriate research question.

The table below provides an overview of some of the main considerations that might inform your decisions about the ways in which you wish to conduct your research:

| Consideration | Questions to ask yourself |

|---|---|

| Access to participants or data | Are you likely to be able to gain access to the participants or data you need to actually conduct the research? Are the sensitivities of ethical considerations involved likely to be too challenging to be easily overcome? |

| Consent | If access is given, are the intended participants likely to give or be able to give their informed consent? Will they be willing or able to cooperate? |

| Personal and professional considerations | Are your personal skills, motivations, beliefs and commitments compatible with the sort of research you are intending to carry out? Do you have the right level of expertise to make appropriate decisions about what to prioritise? |

| Time | Can the project actually be done (and is it manageable) within the time you have available? Are participants or colleagues likely to be able to give up their time as required? Have you factored in time for following up and writing up, and contingency time for if certain things don't go to plan? |

| Costs and resources | Are the resources and materials you need (human and material) within the scope of your research funding? Will your research incur printing, postage or administrative support costs? Will participants have access to the resources they need (e.g. software or appropriate venues) to participate? |

| Supervision | Is there someone available who can adequately supervise the research or provide expert guidance? |

| Value | Can and will this research actually make any difference? |

'It is difficult to overstate the importance of researchers doing their homework before planning the research in any detail […]. The researcher is advised to consider carefully the practicability of the research before embarking on a lost cause in trying to conduct a study that is doomed from the very start because insufficient attention has been paid to practical constraints and issues.' Cohen, Manion and Morrison, 2018, pp. 158-60 'As the saying goes, "the best way to eat an elephant is one bite at a time"!' Cohen, Manion and Morrison, 2018, p. 160

Further reading

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2018), Chapter 9 – “Choosing a research project” (Section 9.5: “Ensuring that the research can be conducted”) in Cohen, L.,

Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (eds), Research Methods in Education (Abingdon, Routledge, 8th edn, pp. 158-160.

Hands-on research and the practical application of scientific concepts is critical for students as they learn and grow throughout their education. Allowing students to see the real world relevance of the subject matter they are learning goes a long way towards engaging students in the material. Students who can see how the material can be applied to their daily lives are more likely to find it compelling and be interested in asking questions and exploring.

Additionally, hands-on research and practical application of concepts can help students develop important skills such as problem-solving, critical thinking, and collaboration. These are skills that transcend fields, and they are essential for navigating higher education and the workforce. Opportunities to develop these skills in a secondary education setting can set students on a road to success.

The Headwaters Research Experience provides students with a robust experience to discover and nurture these vital skills. Students are able to take their science education to a new level while being mentored by a professional scientist in designing and conducting an original research project. Students see through the project from conception to publication by conducting field research (or compiling pre-existing available datasets) and learning how to analyze their findings.

Our Fall Research Experience participants just presented their research last week:

The Headwaters Research Experience encourages hands-on research and practical application of concepts while students are still in the secondary education phase of their lives. Students exposed to this type of education emerge from the program with a completely different outlook with regards to science and they see opportunities to pursue science open in front of them. This isn’t an experience that all students are able to have through their traditional school programs, which is why Headwaters offers this program – we believe in expanding access to hands-on science and guiding students as they explore new skills.

Sign Up for Our Spring Research Experience

Sign-ups are live for our Spring Research Experience and we are offering four additional mentor hours to students who sign up through December 31st! Mentoring is a key complement to the practical skills side of science education at Headwaters!

Hailey Levien Blide

Bay Area Program Coordinator

Hailey is originally from Davis, CA and has lived in the Bay Area for three years. She got her degree from UC Berkeley in Conservation and Resource Studies. Hailey manages after school programs, field days, and camps all throughout the East Bay! Her scientific background is in botany, fire ecology, and forestry. When she’s not sharing her love of science and nature with kids, she can be found doing her favorite activities: baking, gardening, birding, backpacking, and exploring new terrain.

Tara Webster (she/they)

Fundraising Coordinator

Tara is an experienced higher education science and engineering educator who strives for inclusive excellence through empathy, compassion, mutual aid, and community advocacy. Passionate about the educational advancement of traditionally underserved students, Tara uses outdoor science outreach to increase the representation and retention of first-generation BIPOC students in STEM. As a first-generation college graduate, she received her B.S. and M.S. in biology from the University of Nevada, Reno. She is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in STEM Education with an emphasis on justice-centered learning of social and political issues in post-secondary STEM classrooms.

Outside of her professional and academic pursuits, she is a self-taught carpenter and enjoys spending time in her pollinator garden with her dogs, cat, and chickens.

Program and Fundraising Manager

Rian Fried graduated from Brandeis University with a double major with B.A.s in Environmental Studies and International and Global Studies and a minor in Economics. He has worked at summer camps and most recently Supervised the program ambassadors for Sierra Nevada Alliance. He joined Headwaters because of his passion for science! He moved to Tahoe a few months after graduating for the winter season and fell in love with the area. In Rian’s free time, he loves skiing, rock climbing, mountain biking, and basically anything else outside.

Katie Cannon

Program Manager of the Bay Area

Katie is the Program Manager of the Bay Area, managing after school and summer camps. Katie is originally from North Carolina and just recently made the move to California. She has her degree in special education and is working on her master of arts in biology through Project Dragonfly out of Miami University in Ohio. When not working, Katie loves to hang out with her rescue dog Charley and explore new areas in her new hometown.

Morgan Long

Program Manager

Morgan manages school programs and summer camps in the Tahoe, Reno and Sacramento areas. She has a Master’s degree in ecology, evolution and conservation biology from the University of Nevada, Reno where she studied black bear denning and hibernation. Morgan is excited to share her excitement for research and ecology with Headwaters students. Originally from Minnesota, she loves any activity that involves snow.

Savannah Blide

Program and Fundraising Assistant

Savannah graduated with a degree in Environmental Studies and Public Policy from UC Berkeley. Her thesis was on social and policy dimensions of public lands protection. Savannah grew up in Truckee and is passionate about protecting our environment and engaging others in her love of nature. She loves food systems and being outside, and has most recently worked as a farmer in Nevada County. In her free time, she is happiest swimming in the river, mountain biking, and trying new recipes.

Courtney Kudera

Data Analyst and Research Experience Manager

Megan Seifert

Executive Director

Megan holds a PhD in zoology from Washington State University and is passionate about science and the environment. Her focus is on teaching more people the process of science and she hopes to bring it to as many students as possible across the US. In her free time, Meg enjoys Nordic skiing, running, and playing with her family in the Sierra.

Anne Espeset

Grants and Programs

Anne holds a Ph.D. in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology from the University of Nevada, Reno where she researched the impacts of human-induced changes on sexually selected signals of a butterfly. She has also been a part of several scientific outreach programs, including a community science project (Pieris Project) and the University of Nevada’s Museum of Natural History. Anne is excited to continue sharing the scientific process and research with a diversity of students through the Headwaters Science Institute!

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Arab J Urol

- v.12(1); 2014 Mar

Why should I do research? Is it a waste of time?

Athanasios dellis.

a 2nd Department of Surgery, Aretaieion Hospital, University of Athens, Greece

Andreas Skolarikos

b 2nd Department of Urology, Sismanogleion Hospital, University of Athens, Greece

Athanasios G. Papatsoris

- • In medicine, research is the search for scientific knowledge, which is crucial for the development of novel medications and techniques.

- • Conducting research provides a deeper understanding of several scientific topics of the specialty of each doctor.

- • Research through RCTs represents the principal methodological approach.

- • There are two main research processes; qualitative and quantitative studies.

- • It is important to develop Research Units in hospitals and medical centres.

- • Ethics and the high quality of research are ensured by committees (i.e., Internal Board Review, Ethics Research Committee).

- • Research sessions could be implemented in the job plans of doctors.

- • Research is not a waste of time, but a scientific investment.

To answer the questions ‘Why should I do research? Is it a waste of time?’ and present relevant issues.

Medline was used to identify relevant articles published from 2000 to 2013, using the following keywords ‘medicine’, ‘research’, ‘purpose’, ‘study’, ‘trial’, ‘urology’.

Research is the most important activity to achieve scientific progress. Although it is an easy process on a theoretical basis, practically it is a laborious process, and full commitment and dedication are of paramount importance. Currently, given that the financial crisis has a key influence in daily practice, the need to stress the real purpose of research is crucial.

Research is necessary and not a waste of time. Efforts to improving medical knowledge should be continuous.

What is research?

Research is a general term that covers all processes aiming to find responses to worthwhile scientific questions by means of a systematic and scientific approach. In fact, research is the search for scientific knowledge, a systematically formal process to increase the fund of knowledge and use it properly for the development of novel applications.

There are several types of research, such as basic science laboratory research, translational research, and clinical and population-based research. Medical research through randomised clinical trials (RCTs) represents the principal methodological approach for the structured assessment of medical outcomes. RCTs provide prospective and investigator-controlled studies, representing the highest level of evidence (LoE) and grade of recommendation, and define the ultimate practice guideline [1] . However, many constraints, such as ethical, economic and/or social issues, render the conduct of RCTs difficult and their application problematic. For instance, in one of the largest RCTs in urology, on preventing prostate cancer with finasteride, the LoE was 1 [2] . In this RCT, after 7 years of finasteride chemoprevention, the rate of cancer decreased from 24.4% to 18.4%. Based on this study, it could be postulated that finasteride chemoprevention should be offered to men in the general population in an attempt to reduce the risk of prostate cancer. However, the findings of this RCT could not be implemented universally due to financial issues [3] .

There are two main research processes, i.e., qualitative and quantitative studies. Although very different in structure and methods, these studies represent two arms of the same research body. Qualitative studies are based mainly on human experience, using notions and theoretical information without quantifying variables, while quantitative studies record information obtained from participants in a numerical form, to enable a statistical analysis of the data. Therefore, quantitative studies can be used to establish the existence of associative or causal relationships between variables.

From a practical perspective, adding a Research Unit to a Medical Department would ultimately enhance clinical practice and education. As such, almost all hospitals in Western countries have research and development (R&D) departments, where the R&D can be linked with clinical innovation. Basic areas in this field include business planning, sales policies and activities, model design, and strategic propositions and campaign development. However, if researchers are not motivated, the research could be counterproductive, and the whole process could ultimately be a waste of time and effort [4] .

The ethics and the high quality of research are ensured by committees, such as the Internal Review Board, and Ethics Research Committees, especially in academic hospitals. They consist of highly educated and dedicated scientists of good faith as well as objectivity, to be the trustees of ethical and properly designed and performed studies.

Do we need research?

Research is the fuel for future progress and it has significantly shaped perspectives in medicine. In urology there are numerous examples showing that current practice has rapidly changed as a result of several key research findings. For example, from the research of Huggins and Hodges (who won the Nobel Prize in 1966), hormone therapy has become the standard treatment for patients with advanced/metastatic prostate cancer. The use of ESWL to treat stones in the urinary tract is another example of research that has improved practice in urology. The current trend in urology to use robotic assistance in surgery is a relatively recent example of how constant research worldwide improves everyday clinical practice [5] . Furthermore, in a more sophisticated field, research is used to identify factors influencing decision-making, clarify the preferred alternatives, and encourage the selection of a preferred screening option in diseases such as prostate cancer [6,7] .

Conducting research provides a deeper understanding of several scientific topics within the specialty of each doctor. Furthermore, it helps doctors of a particular specialty to understand better the scientific work of other colleagues. Despite the different areas of interest between the different specialties, there are common research methods.

In a University, PhD and MSc students concentrate their efforts at higher research levels. Apart from having to produce a challenging and stimulating thesis, young researchers try to develop their analytical, conceptual and critical thinking skills to the highest academic level. Also, postgraduate students thus prepare themselves for a future job in the global market.

During the research process several approaches can be tested and compared for their safety and efficacy, while the results of this procedure can be recorded and statistically analysed to extract the relevant results. Similarly, any aspects of false results and side-effects, e.g., for new medications, can be detected and properly evaluated to devise every possible improvement. Hence, research components under the auspices of dedicated supervisors, assisted by devoted personnel, are of utmost importance. Also, funding is a catalyst for the optimum progress of the research programme, and it must be independent from any other financial source with a possible conflict. Unfortunately, in cases of economic crisis in a hospital, the first department that is trimmed is research.

Is research time a waste of time?