Assignment of a claim or cause of action

Practical law uk practice note 1-522-7861 (approx. 32 pages), get full access to this document with practical law.

Try free and see for yourself how Practical Law resources can enhance productivity, increase efficiency, and improve response times.

About Practical Law

This document is from Thomson Reuters Practical Law, the legal know-how that goes beyond primary law and traditional legal research to give lawyers a better starting point. We provide standard documents, checklists, legal updates, how-to guides, and more.

- Increase efficiency

- Enhance productivity

- Improve response time

- Substantive Law

- 1 Scope of this note

- Effect of contractual prohibition on assignment

- 3 At what stage may a claim be assigned?

- 4 To whom can a cause of action be assigned?

- Legal assignment or equitable assignment?

- Requirements for a legal assignment

- Requirements for an equitable assignment

- Effect of consideration

- No loss occurring to assignee before assignment of claim

- General principles

- Exceptions to the rules on maintenance and champerty

- Security for costs

- Costs incurred by the assignor before the assignment

- Who is liable for costs awarded in favour of the defendant?

- Assignment of benefit and burden of solicitors' retainer

- When might an office-holder assign a claim?

- Who may assign a claim in insolvency?

- Claims capable of assignment by an office-holder

- Claims not capable of assignment by an office-holder

- Assignment of claims to an office-holder

- Potential liability of office-holder

- 10 Drafting an assignment of a cause of action

- Legal assignment

- Equitable assignment

- Assigning proceedings that have been commenced

- Counterclaims where a claim has been assigned

Assignment of claims

An untraditional approach to combining the claims of plaintiffs; how it differs from class actions, joinder, consolidation, relation and coordination

A large class of plaintiffs engages you to bring a common action against a defendant or set of defendants. As counsel, you resolve to combine the plaintiffs’ various claims into a single lawsuit. In this article, we touch on some of the traditional approaches, such as a class action, joinder, consolidation, relation, and coordination. To that list, we add as an approach the assignment of claims, a procedural vehicle validated by the United States Supreme Court, but not typically employed to combine the claims of numerous plaintiffs.

Class actions

In Hansberry v. Lee (1940) 311 U.S. 32, the United States Supreme Court explained that “[t]he class suit was an invention of equity to enable it to proceed to a decree in suits where the number of those interested in the subject of the litigation is so great that their joinder as parties in conformity to the usual rules of procedure is impracticable. Courts are not infrequently called upon to proceed with causes in which the number of those interested in the litigation is so great as to make difficult or impossible the joinder of all because some are not within the jurisdiction or because their whereabouts is unknown or where if all were made parties to the suit its continued abatement by the death of some would prevent or unduly delay a decree. In such cases where the interests of those not joined are of the same class as the interests of those who are, and where it is considered that the latter fairly represent the former in the prosecution of the litigation of the issues in which all have a common interest, the court will proceed to a decree.” ( Id. at pp. 41-42.)

In California’s state courts, class actions are authorized by Code of Civil Procedure section 382, which applies when the issue is “‘one of a common or general interest, of many persons, or when the parties are numerous, and it is impracticable to bring them all before the court.’” ( Noel v. Thrifty Payless, Inc. (2019) 7 Cal.5th 955, 968; see also, e.g., Cal. Rules of Court, rules 3.760-3.771.) “The party advocating class treatment must demonstrate the existence of an ascertainable and sufficiently numerous class, a well-defined community of interest, and substantial benefits from certification that render proceeding as a class superior to the alternatives.” ( Brinker Restaurant Corp. v. Superior Court (2012) 53 Cal.4th 1004, 1021.) “The community of interest requirement involves three factors: ‘(1) predominant common questions of law or fact; (2) class representatives with claims or defenses typical of the class; and (3) class representatives who can adequately represent the class.’” ( Linder v. Thrifty Oil Co. (2000) 23 Cal.4th 429, 435; see Civ. Code, § 1750 et seq. [Consumers Legal Remedies Act]; cf. Fed. Rules Civ.Proc., rule 23(a) [prerequisites for federal class action].)

Parties, acting as co-plaintiffs, can also obtain economies of scale by joining their claims in a single lawsuit. Under California’s permissive joinder statute, Code of Civil Procedure section 378 (section 378), individuals may join in one action as plaintiffs if the following conditions are met:

(a)(1) They assert any right to relief jointly, severally, or in the alternative, in respect of or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences and if any question of law or fact common to all these persons will arise in the action; or

(2) They have a claim, right, or interest adverse to the defendant in the property or controversy which is the subject of the action.

(b) It is not necessary that each plaintiff be interested as to every cause of action or as to all relief prayed for. Judgment may be given for one or more of the plaintiffs according to their respective right to relief.

This strategy of joining multiple persons in one action has been referred to as a “mass action” in some decisions involving numerous plaintiffs. (See Aghaji v. Bank of America, N.A. (2016) 247 Cal.App.4th 1110, 1113; Petersen v. Bank of America Corp . (2014) 232 Cal.App.4th 238, 240 ( Petersen ); cf. 28 U.S.C. § 1332(d)(11)(B) [federal definition of “mass action”].)

In Petersen , for example, 965 plaintiffs who borrowed money from Countrywide Financial Corporation in the mid-2000’s banded together and filed a single lawsuit against Countrywide and related entities. ( Petersen , supra , 232 Cal.App.4th at pp. 242-243.) The plaintiffs alleged Countrywide had developed a strategy to increase its profits by misrepresenting the loan terms and using captive real estate appraisers to provide dishonest appraisals that inflated home prices and induced borrowers to take loans Countrywide knew they could not afford. ( Id. at p. 241.) The plaintiffs alleged Countrywide had no intent to keep these loans, but to bundle and sell them on the secondary market to unsuspecting investors who would bear the risk the borrowers could not repay. ( Id. at pp. 241, 245.) Countrywide and the related defendants demurred on the ground of misjoinder of the plaintiffs in violation of section 378. The trial court sustained the demurrer without leave to amend and dismissed all plaintiffs except the one whose name appeared first in the caption. ( Id . at p. 247.) The Court of Appeal reversed and remanded for further proceedings. ( Id . at p. 256.)

Petersen resolved two questions. First, it concluded the operative pleading alleged wrongs arising out of “‘the same . . . series of transactions’” that would entail litigation of at least one common question of law or fact. ( Petersen, supra, 232 Cal.App.4th at p. 241.) The appellate court noted the individual damages among the 965 plaintiffs would vary widely, but the question of liability provided a basis for joining the claims in a single action. ( Id. at p. 253.) Second, the appellate court concluded “California’s procedures governing permissive joinder are up to the task of managing mass actions like this one.” ( Id. at p. 242.)

Consolidation

Code of Civil Procedure section 1048, subdivision (a) provides that, “[w]hen actions involving a common question of law or fact are pending before the court, it may order a joint hearing or trial of any or all the matters in issue in the actions; it may order all the actions consolidated and it may make such orders concerning proceedings therein as may tend to avoid unnecessary costs or delay.” (See also Fed. Rules Civ.Proc., rule 42.)

There are two types of consolidation. The first is a consolidation for purposes of trial only, when the actions remain otherwise separate. The second is a complete consolidation or consolidation for all purposes, when the actions are merged into a single proceeding under one case number and result in only one verdict or set of findings and one judgment. ( Hamilton v. Asbestos Corp., Ltd. (2000) 22 Cal.4th 1127, 1147 ( Hamilton ).)

Consolidation is designed to promote trial convenience and economy by avoiding duplication of procedure, particularly in the proof of issues common to the various actions. (4 Witkin, Cal. Procedure (5th ed. 2008) Pleadings, § 341, p. 470.) Unless all parties in the involved cases stipulate, consolidation requires a written, noticed motion (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 3.350(a); Sutter Health Uninsured Pricing Cases (2009) 171 Cal.App.4th 495, 514), and is subject to the trial court’s discretion. ( Hamilton, supra, 22 Cal.4th at p. 1147.)

In a procedure somewhat similar to consolidation, under California Rules of Court, rule 3.300(a), a pending civil action may be related to other civil actions (whether still pending or already resolved by dismissal or judgment) if the matters “[a]rise from the same or substantially identical transactions, incidents, or events requiring the determination of the same or substantially identical questions of law or fact” or “[a]re likely for other reasons to require substantial duplication of judicial resources if heard by different judges.” ( Id. , rule 3.300(a)(2), (4).) An order to relate cases may be made only after service of a notice on all parties that identifies the potentially related cases. No written motion is required. ( Id ., rule 3.300(h)(1).) The Judicial Council provides a standard form for this purpose. When a trial court agrees the cases listed in the notice are related, all are typically assigned to the trial judge in whose department the first case was filed. ( Id ., rule 3.300(h)(1)(A).)

Related cases are not consolidated cases. Related cases maintain their separate identities but are heard by the same trial judge. Consolidated cases, in contrast, essentially merge and proceed under a single case number.

Coordination

Under Code of Civil Procedure section 404, the Chairperson of the Judicial Council is authorized to coordinate actions filed in different courts that share common questions of fact or law. (See Cal. Rules of Court, rule 3.500 et seq.) The principles underlying coordination are similar to those that govern consolidation of actions filed in a single court. (See Pesses v. Superior Court (1980) 107 Cal.App.3d 117, 123; see also 28 U.S.C. § 1407 [complex and multidistrict litigation].)

Thus, for example, in McGhan Med. Corp. v. Superior Court (1992) 11 Cal.App.4th 804 ( McGhan ), the plaintiffs petitioned for coordination of 300 to 600 breast implant cases pending in 20 different counties. Coordination was denied because the motion judge found that common questions did not predominate “in that the cases involve[d] different implants, different designs, different warnings, different defendants, different theories of defect, different modes of failure, and different injuries.” ( Id. at p. 808.) Among other factors, the trial court concluded that it was impractical to send hundreds of cases to a single county and that the benefits of coordination could be best achieved by voluntary cooperation among the judges in the counties where the cases were pending. ( Id. at p. 808, fn. 2.)

The Court of Appeal reversed in an interlocutory proceeding, ruling the trial court had misconceived the requirements of a coordinated proceeding. ( McGhan, supra, 11 Cal.App.4th at p. 811.) As the appellate court explained, Code of Civil Procedure section 404.7 gives the Judicial Council great flexibility and broad discretion over the procedure in coordinated actions. ( Id. at p. 812.) Thus, on balance, the coordinating judge would be better off confronting the coordination drawbacks (including difficulties arising from unique cases, discovery difficulties, multiple trials, the necessity of travel, and occasional delay) because the likely benefits (efficient discovery and motion practice) were so much greater. ( Id. at pp. 812-814.)

Civil Code section 954 states “[a] thing in action, arising out of the violation of a right of property, or out of an obligation, may be transferred by the owner.” The term “thing in action” means “a right to recover money or other personal property by a judicial proceeding.” (Civ. Code, § 953.) California’s Supreme Court has summarized these provisions by stating: “A cause of action is transferable, that is, assignable, by its owner if it arises out of a legal obligation or a violation of a property right. . . .” ( Amalgamated Transit Union, Local 1756, AFL-CIO v. Superior Court (2009) 46 Cal.4th 993, 1003.) The enactment of Civil Code sections 953 and 954 lifted many restrictions on assignability of causes of action. ( Wikstrom v. Yolo Fliers Club (1929) 206 Cal. 461, 464; AMCO Ins. Co. v. All Solutions Ins. Agency, LLC (2016) 244 Cal.App.4th 883, 891 ( AMCO ).)

Thus, California’s statutes establish the general rule that causes of action are assignable. ( AMCO, supra , 244 Cal.App.4th at pp. 891-892.) This general rule of assignability applies to causes of action arising out of a wrong involving injury to personal or real property. ( Time Out, LLC v. Youabian, Inc. (2014) 229 Cal.App.4th 1001, 1009; see also, e.g., Bush v. Superior Court (1992) 10 Cal.App.4th 1374, 1381 [“‘assignability of things [in action] is now the rule; nonassignability, the exception. . .’”].)

Although the assignment of claims on behalf of others to an assignee, or group of assignees, is not unique, it has not typically been used as a procedural vehicle for combining the claims of numerous plaintiffs. But, that’s not to say it can’t be done.

In fact, the United States Supreme Court has sanctioned such an approach. In Sprint Communications Co., L.P. v. APCC Services, Inc. (2008) 554 U.S. 269 ( Sprint ), approximately 1,400 payphone operators assigned legal title to their claims for amounts due from Sprint, AT&T, and other long-distance carriers to a group of collection firms described as “aggregators.” ( Id. at p. 272.) The legal issue presented to the United States Supreme Court was whether the assignees had standing to pursue the claims in federal court even though they had promised to remit the proceeds of the litigation to the assignor. ( Id . at p. 271.) The Court concluded the assignees had standing.

In support of its conclusion, the Court recognized the long-standing right to assign lawsuits:

. . . [C]ourts have long found ways to allow assignees to bring suit; that where assignment is at issue, courts — both before and after the founding — have always permitted the party with legal title alone to bring suit; and that there is a strong tradition specifically of suits by assignees for collection. We find this history and precedent ‘well nigh conclusive’ in respect to the issue before us: Lawsuits by assignees, including assignees for collection only, are ‘cases and controversies of the sort traditionally amenable to, and resolved by, the judicial process.’

( Sprint , supra , 554 U.S . at p. 285.)

On this basis, the Court concluded:

Petitioners have not offered any convincing reason why we should depart from the historical tradition of suits by assignees, including assignees for collection. In any event, we find that the assignees before us satisfy the Article III standing requirements articulated in more modern decisions of this Court.

( Sprint , supra , 554 U.S at pp. 285-286.)

The Court also considered the argument that the aggregators were attempting to circumvent the class-action requirements of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23. ( Sprint, supra, 554 U.S. at pp. 290-291.) The Court rejected this argument as a barrier to aggregation by assignment on the grounds that (1) class actions were permissive, not mandatory, and (2) “class actions constitute but one of several methods for bringing about aggregation of claims, i.e., they are but one of several methods by which multiple similarly situated parties get similar claims resolved at one time and in one federal forum. [Citations.]” ( Id. at p. 291.)

Granted, Sprint arose in the context of Article III, a “prudential standing” analysis. However, in reaching its decision that assignees had standing, the Court relied significantly on three California state decisions addressing assignment of rights under California law. (See Sprint, supra, 554 U.S. at pp. 294-296.)

Under California law, assignment of claims is not a panacea. Not all claims can be assigned. In California, assignment is not allowed for tort causes of action based on “wrongs done to the person, the reputation or the feelings of an injured party,” including “causes of action for slander, assault and battery, negligent personal injuries, seduction, breach of marriage promise, and malicious prosecution.” ( AMCO, supra , 244 Cal.App.4th at p. 892 [exceptions to assignment also include “legal malpractice claims and certain types of fraud claims”].) Other assignments are statutorily prohibited. (See, e.g., Civ. Code, § 2985.1 [regulating assignment of real property sales contracts]; Gov. Code, § 8880.325 [state lottery prizes not assignable].)

Likewise, because a right of action cannot be split, a partial assignment will require the joinder of the partial assignor as an indispensable party. (See, e.g., Bank of the Orient v. Superior Court (1977) 67 Cal.App.3d 588, 595 [“[W]here . . . there has been a partial assignment all parties claiming an interest in the assignment must be joined as plaintiffs . . . ”]; 4 Witkin, Cal. Procedure, supra, Pleadings, § 131(2), p. 198 [“If the assignor has made only a partial assignment, the assignor remains beneficially interested in the claim and the assignee cannot sue alone”].)

That said, California’s rules of law regarding standing and assignments do not prohibit an assignee’s aggregation of a large number of claims against a single defendant or multiple defendants into a single lawsuit. To the contrary, no limitations or conditions on this type of aggregation of assigned claims is imposed from other rules of law, such as California’s compulsory joinder statute. (See Sprint , supra , 554 U.S. at p. 292 [to address practical problems that might arise because aggregators, not payphone operators, were suing, district “court might grant a motion to join the payphone operators to the case as ‘required’ parties” under Fed. Rules Civ.Proc., rule 19].)

There are many procedural approaches to evaluate when seeking to combine the claims of multiple plaintiffs. Class actions and joinders are more traditional methods that trial counsel rely on to bring claims together. Although a largely unexplored procedural approach, assignment appears to be an expedient way of combining the claims of numerous plaintiffs. It avoids the legal requirements imposed for class actions and joinders, and it sidesteps a trial judge’s discretion regarding whether to consolidate, relate, or coordinate actions. Indeed, under the right circumstances, an assignment of claims might provide a means of bypassing class action waivers in arbitration agreements. Perhaps an assignment of claims should be added to the mix of considerations when deciding how to bring a case involving numerous plaintiffs with similar claims against a common defendant or set of defendants.

Judith Posner

Judith Posner is an attorney at Benedon & Serlin, LLP , a boutique appellate law firm.

Gerald Serlin

Gerald Serlin is an attorney at Benedon & Serlin, LLP , a boutique appellate law firm.

Subject Matter Index

Copyright © 2024 by the author. For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine

- Featured Articles

- Recent Issues

- Advertising

- Contributors Writer's Guidelines

- Search Advanced Search

When Assigning the Right to Pursue Relief, Always Remember to Assign Title to, Or Ownership in, The Claim

- Posted on: Oct 4 2016

Whether a party has standing to bring a lawsuit is often considered through the constitutional lens of justiciability – that is, whether there is a “case or controversy” between the plaintiff and the defendant “within the meaning of Art. III.” Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 498 (1975). To have Article III standing, “the plaintiff [must have] ‘alleged such a personal stake in the outcome of the controversy’ as to warrant [its] invocation of federal-court jurisdiction and to justify exercise of the court’s remedial powers on [its] behalf.” Id. at 498–99 (quoting Baker v. Carr , 369 U.S. 186, 204 (1962)).

To show a personal stake in the litigation, the plaintiff must establish three things: First, he/she has sustained an “injury in fact” that is both “concrete and particularized” and “actual or imminent.” Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife , 504 U.S. 555, 560 (1992) (internal quotation marks omitted). Second, the injury has to be caused in some way by the defendant’s action or omission. Id . Finally, a favorable resolution of the case is “likely” to redress the injury. Id . at 561.

When a person or entity receives an assignment of claims, the question becomes whether he/she can show a personal stake in the outcome of the litigation, i.e. , a case and controversy “of the sort traditionally amenable to, and resolved by, the judicial process.’” Sprint Commc’ns Co., L.P. v. APCC Servs., Inc., 554 U.S. 269, 285 (2008) (quoting Vt. Agency of Natural Res. v. United States ex rel. Stevens, 529 U.S. 765, 777–78 (2000)).

To assign a claim effectively, the claim’s owner “must manifest an intention to make the assignee the owner of the claim.” Advanced Magnetics, Inc. v. Bayfront Partners, Inc. , 106 F.3d 11, 17 (2d Cir. 1997) (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted). A would-be assignor need not use any particular language to validly assign its claim “so long as the language manifests [the assignor’s] intention to transfer at least title or ownership , i.e., to accomplish ‘a completed transfer of the entire interest of the assignor in the particular subject of assignment.’” Id. (emphasis added) (citations omitted). An assignor’s grant of, for example, “‘the power to commence and prosecute to final consummation or compromise any suits, actions or proceedings,’” id. at 18 (quoting agreements that were the subject of that appeal), may validly create a power of attorney, but that language would not validly assign a claim, because it does “not purport to transfer title or ownership” of one. Id.

On September 15, 2016, the New York Appellate Division, First Department, issued a decision addressing the foregoing principles holding that one of the plaintiffs lacked standing to assert claims because the assignment of the right to pursue remedies did not constitute the assignment of claims. Cortlandt St. Recovery Corp. v. Hellas Telecom., S.à.r.l. , 2016 NY Slip Op. 06051.

BACKGROUND :

Cortlandt involved four related actions in which the plaintiffs – Cortlandt Street Recovery Corp. (“Cortlandt”), an assignee for collection, and Wilmington Trust Co. (“WTC”), an indenture trustee – sought payment of the principal and interest on notes issued in public offerings. Each action alleged that Hellas Telecommunications, S.a.r.l. and its affiliated entities, the issuer and guarantor of the notes, transferred the proceeds of the notes by means of fraudulent conveyances to two private equity firms, Apax Partners, LLP/TPG Capital, L.P. – the other defendants named in the actions.

The defendants moved to dismiss the actions on numerous grounds, including that Cortlandt, as the assignee for collection, lacked standing to pursue the actions. To cure the claimed standing defect, Cortlandt and WTC moved to amend the complaints to add SPQR Capital (Cayman) Ltd. (“SPQR”), the assignor of note interests to Cortlandt, as a plaintiff. The plaintiffs alleged that, inter alia , SPQR entered into an addendum to the assignment with Cortlandt pursuant to which Cortlandt received “all right, title, and interest” in the notes.

The Motion Court granted the motions to dismiss, holding that, among other things, Cortlandt lacked standing to maintain the actions and that, although the standing defect was not jurisdictional and could be cured, the plaintiffs failed to cure the defect in the proposed amended complaint. Cortlandt St. Recovery Corp. v. Hellas Telecom., S.à.r.l. , 47 Misc. 3d 544 (Sup. Ct., N.Y. Cnty. 2014).

The Motion Court’s Ruling

As an initial matter, the Motion Court cited to the reasoning of the court in Cortlandt Street Recovery Corp. v. Deutsche Bank AG, London Branch , No. 12 Civ. 9351 (JPO), 2013 WL 3762882, 2013 US Dist. LEXIS 100741 (S.D.N.Y. July 18, 2013) (the “SDNY Action”), a related action that was dismissed on standing grounds. The complaint in the SDNY Action, like the complaints before the Motion Court, alleged that Cortlandt was the assignee of the notes with a “right to collect” the principal and interest due on the notes. As evidence of these rights, Cortlandt produced an assignment, similar to the ones in the New York Supreme Court actions, which provided that as the assignee with the right to collect, Cortlandt could collect the principal and interest due on the notes and pursue all remedies with respect thereto. In dismissing the SDNY Action, Judge Oetken found that the complaint did not allege, and the assignment did not provide, that “title to or ownership of the claims has been assigned to Cortlandt.” 2013 WL 3762882, at *2, 2013 US Dist. LEXIS 100741, at *7. The court also found that the grant of a power of attorney (that is, the power to sue on and collect on a claim) was “not the equivalent of an assignment of ownership” of a claim. 2013 WL 3762882 at *1, 2013 US Dist. LEXIS 100741 at *5. Consequently, because the assignment did not transfer title or ownership of the claim to Cortlandt, there was no case or controversy for the court to decide ( i.e. , Cortlandt could not prove that it had an interest in the outcome of the litigation).

The Motion Court “concur[red] with” Judge Oeken’s decision, holding that “the assignments to Cortlandt … were assignments of a right of collection, not of title to the claims, and are accordingly insufficient as a matter of law to confer standing upon Cortlandt.” In so holding, the Motion Court observed that although New York does not have an analogue to Article III, it is nevertheless analogous in its requirement that a plaintiff have a stake in the outcome of the litigation:

New York does not have an analogue to article III. However, the New York standards for standing are analogous, as New York requires “[t]he existence of an injury in fact—an actual legal stake in the matter being adjudicated.”

Under long-standing New York law, an assignee is the “real party in interest” where the “title to the specific claim” is passed to the assignee, even if the assignee may ultimately be liable to another for the amounts collected.

Citations omitted.

Based upon the foregoing, the Motion Court found that Cortlandt lacked standing to pursue the actions.

Cortlandt appealed the dismissal. With regard to the Motion Court’s dismissal of Cortlandt on standing grounds, the First Department affirmed the Motion Court’s ruling, holding:

The [IAS] court correctly found that plaintiff Cortlandt Street Recovery Corp. lacks standing to bring the claims in Index Nos. 651693/10 and 653357/11 because, while the assignments to Cortlandt for the PIK notes granted it “full rights to collect amounts of principal and interest due on the Notes, and to pursue all remedies,” they did not transfer “title or ownership” of the claims.

The Takeaway

Cortlandt limits the ability of an assignee to pursue a lawsuit when the assignee has no direct interest in the outcome of the litigation. By requiring an assignee to have legal title to, or an ownership interest in, the claim, the Court made clear that only a valid assignment of a claim will suffice to fulfill the injury-in-fact requirement. Cortlandt also makes clear that a power of attorney permitting another to conduct litigation on behalf of others as their attorney-in-fact is not a valid assignment and does not confer a legal title to the claims it brings. Therefore, as the title of this article warns: when assigning the right to pursue relief, always remember to assign title to, or ownership in, the claim.

Tagged with: Business Law

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

CACI No. 326. Assignment Contested

Judicial council of california civil jury instructions (2024 edition).

© Judicial Council of California .

Page last reviewed May 2024

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

- Support Center

- System Status

Understanding the cause of action in California legal proceedings

- April 26, 2024

Jennifer Anderson

The precise legal definition of a cause of action is important to understand for legal professionals today.

For many legal practitioners within the State of California, a “cause of action” (or “CoA” as we’ll sometimes refer to it here) is synonymous with litigation – and for good reason. At its core, a CoA is what makes up a valid lawsuit; preparation , as always, is key.

Ultimately, a CoA is the state law equivalent of the “claim for relief” set forth in Federal Rule of Civil Procedure, Rule 8 . It is the legal theory and corresponding set of facts that gives one litigant the right to seek judicial relief against another.

And while it’s certainly possible to get highly academic and historical about this common mechanism, we’re not going to do that here.

In this article, we simply aim to explore what you need to know about causes of action within the California judicial system – from properly pleading a CoA to the mistakes that might lead to the dismissal of one or more CoAs within a complaint.

And, just for good measure, I’ll finish off by sharing the best tip I ever received for drafting bulletproof CoAs in California.

Legal definition of a cause of action

The legal definition of a cause of action refers to a set of facts or circumstances that give an individual the right to seek judicial relief. It represents the legal grounds on which a plaintiff can bring a lawsuit against a defendant.

A cause of action must include a legally recognized harm or injury caused by the defendant’s actions or failure to act, as well as the necessary elements to establish liability, such as duty, breach, causation, and damages.

Common types of causes of action include breach of contract, negligence, fraud, and violation of statutory rights.

What makes up a cause of action?

In an effort to avoid legalese, think of a cause of action as a ticket into the courtroom. It’s what a plaintiff must present to the court to say, “Here’s why I believe I’m entitled to some form of legal relief.” Without pleading a valid CoA, you won’t get very far in the process.

The cause of action starts with two main ingredients: a legal theory and a set of facts. The theory is your legal basis for seeking relief; it’s the rule that you believe has been violated.

The set of facts, on the other hand, is your story. It’s the specific events that occurred that you claim have infringed upon your rights or caused you harm.

Let’s break those down a bit:

Legal theory

Your legal theory is the backbone of your CoA. Whether it’s a breach of contract, negligence, or any other legal violation, your theory must have some basis in statutes or common law.

In California, some legal theories are so common that the court system actually provides form complaints to help litigants properly plead their CoA. As mentioned prior, some examples include breach of contract , general negligence , products liability , and motor vehicle negligence .

That said, the list of legal theories that form the bases of California causes of action is long. So, if you don’t find yours among California’s prepared forms, don’t give up. Somebody, somewhere, has probably sued someone using the same CoA you wish to assert. ( See the last section of this article for more on that).

Statement of facts

It’s one thing to have a solid legal theory, but the facts are what breathe life into your CoA. In fact, the California Code of Civil Procedure requires that litigants plead a “statement of facts constituting the cause of action, in ordinary and concise language .” (Emphasis added).

The italicized portion of the statute is important. You don’t want to give the court a long-winded recitation of facts that includes extraneous details. Rather, you just want to tell them what they need to know in order to determine whether your lawsuit can proceed.

This means your facts should address each element of your cause of action. Elements, of course, are the necessary components of a particular claim. For a breach of contract CoA, for example, you’d need to lay out facts showing:

- The existence of the contract,

- The obligations it created,

- How those obligations were breached, and

- The resulting damage to you.

Note that this is one area where California practice varies substantially from Federal practice . While Federal courts generally only require notice pleading ( i.e. , giving just enough detail to let the defendant know what your lawsuit is about), California is a fact-pleading state.

That means your complaint needs to assert specific facts that, if proven, would result in you winning your case.

The importance of getting it right

Even though California has fairly generous policies when it comes to amending complaints , the importance of adequately pleading the elements of your cause of action cannot be overstated.

Indeed, a meticulous approach to drafting CoAs is not just about adhering to procedural formalities; it’s about avoiding costly delays (at best) and having your case dismissed (at worst).

Specifically, poorly drafted CoAs are the gateway to a demurrer, a procedural challenge that can derail your lawsuit before you and your client ever set foot in a courtroom. Let’s talk about that risk for a moment, shall we?

Understanding the demurrer

A demurrer serves as a sort of bouncer in the California legal process. A demurrer is a responsive pleading that objects to your complaint and asks the court to throw out your lawsuit. And, in case you’re wondering, “failure to state facts sufficient to constitute a cause of action” is one of the chief bases for a demurrer.

In essence, it is the defendant’s first opportunity to scrutinize the sufficiency of the allegations stated in your complaint. By filing a demurrer, the defendant is asserting that, even if everything you’ve claimed is true, your causes of action cannot possibly survive.

And even though demurrers to complaints are rarely favored by California judges , (a) they do cause delays in your case (which always come with costs to your client), and (b) they can give an early signal to your judge that you’re not a careful practitioner.

Indeed, drafting a cause of action that withstands a demurrer’s test isn’t merely about avoiding dismissal; it’s about affirming the legitimacy and seriousness of your legal endeavor.

A well-constructed CoA serves as a testament to the credibility of your client’s grievances, and reinforces the narrative that their claims are worthy of the court’s attention and, ultimately, relief.

Common pitfalls to avoid

Let’s boil all of this down to some cold, hard advice on drafting adequate CoAs. More particularly, let’s begin by recapping what not to do when trying to draft causes of action that will survive a demurrer:

- Lack of specificity: Perhaps the most frequent misstep is failing to provide enough detail. Unlike a claim for relief in Federal Court, a California CoA needs to be more than just a broad assertion; it requires a narrative that clearly outlines how each element of the legal theory is supported by the facts. Generic claims without specifics are ripe for dismissal.

- Overloading information: On the flip side, inundating your CoA with an excess of irrelevant details can dilute its effectiveness. It’s crucial to strike a balance, focusing on the pertinent facts that directly support your legal theory. Again, the goal is to craft a coherent and compelling narrative that guides the court through your reasoning.

- Misunderstanding the legal bases: Applying the wrong legal principles or misinterpreting statutes can fatally undermine your CoA. This includes overlooking updates to laws or relevant case law precedents. Continuous legal education and thorough research are your best defenses against this pitfall.

Hot tip for drafting a bulletproof CoA

One of the best tips I ever got when it comes to drafting demurrer-proof CoAs was handed to me by an older attorney when I was in my first year of practice. When I initially heard his advice, I thought perhaps he’d lost his mind.

“Go look at the jury instructions,” he said.

“Jury instructions?” I thought to myself. “We haven’t even filed the complaint and this guy wants me preparing for trial? That’s preposterous!”

Oh, how wrong I was.

Once I overcame my young attorney bravado (and after scratching my head over how to draft the complaint for a couple of hours), I followed his advice. And guess what I found? Everything you need to draft the perfect CoA is right there in the California Civil Jury Instructions .

Let’s say you’re drafting a complaint for breach of contract. Well, Jury Instruction 303 is literally titled “Breach of Contract – Essential Factual Elements.”

He was right! Everything I needed to allege (and eventually prove) was laid out in black and white.

The instruction read something like this:

To recover damages from Defendant for breach of contract, Plaintiff must prove all of the following:

- That Plaintiff and Defendant entered into a contract;

- That Plaintiff did all, or substantially all, of the significant things that the contract required;

- That Plaintiff was excused from having to [specify things that plaintiff did not do, e.g., obtain a guarantor on the contract];

- That [specify occurrence of all conditions required by the contract for Defendant’s performance, e.g., the property was rezoned for residential use];

- That [specify condition(s) that did not occur] [was/were] [waived/excused];

- That Defendant failed to do something that the contract required;

- That Defendant did something that the contract prohibited;

- That Plaintiff was harmed; and

- That Defendant’s breach of contract was a substantial factor in causing Plaintiff’s harm.

Understanding the legal definition of a cause of action is essential for legal professionals, especially in the California judicial system, where precise and effective drafting can make or break a case.

Properly structuring and pleading causes of action not only enhances the chances of a successful lawsuit but also demonstrates competence and professionalism.

By avoiding common issues such as lack of specificity, overloading information, and misunderstanding the exact legal definition and application of a cause of action and other legal bases, practitioners can craft robust causes of action that withstand procedural challenges.

That’s it, folks. All you have to do is fill in the factual details and, Voila ! You’ve got yourself a bulletproof cause of action. It’s not the equivalent of legal rocket science, but it is important to spend the time to do it right.

A free, detailed guide on all the basics of eFiling

Learn all the basics about eFiling with this eBook guide. If you have a workflow that needs improving, are new to eFiling, or just want a handy companion guide to share with your colleagues, then this is for you. Download this free eBook now.

Share this article on social media:

More to explore.

How can litigation technology support your law firm?

Personal injury firm based in Oakland sees success with One

A lawyer’s guide to improving your law firm’s profitability

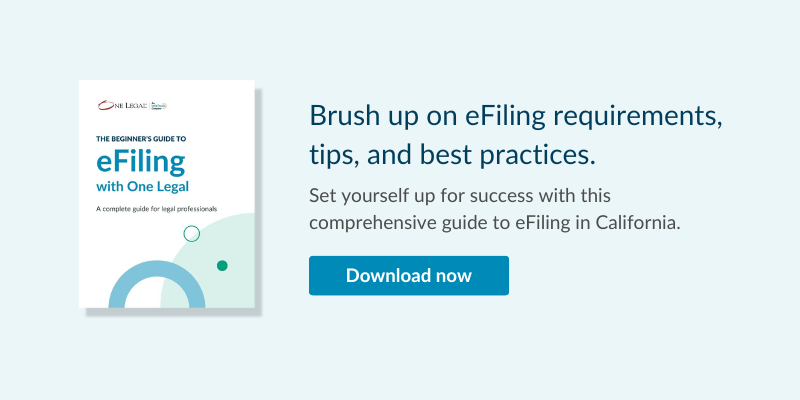

What is One Legal?

We’re California’s leading litigation services platform, offering eFiling, process serving, and courtesy copy delivery in all 58 California counties. Our simple, dependable platform is trusted by over 20,000 law firms to file and serve over a million cases each year.

All of your litigation support needs at your fingertips

© InfoTrack US, Inc.

- Accessibility statement

- Privacy policy

- Terms of service

Legal Up Virtual Conference

Register now to get actionable strategies and inspiration to level up your legal career.

By Katie E. Brach

In the context of large construction defect litigation, we are seeing more partial settlement strategies involving assignments of claims. The most common is when the Developer/General Contractor agrees as part of a partial global settlement to assign its indemnity claims against one or more of the Non-Settling Subcontractor Cross-Defendants to the Plaintiff. In theory, this type of settlement arrangement is beneficial to both the Developer/General Contractor and the Homeowner/Association Plaintiff because it allows the General Contractor to settle out around a stubborn or non-contributing subcontractor without having exposure to the fees and costs associated with a voluntary dismissal of its Cross-Complaint, and it provides the Plaintiff with additional damage claims and an avenue for recovery of attorney’s fees under the assigned subcontract(s). This type of settlement is also designed to put additional pressure on the non-settling Subcontractor(s) by leaving them exposed to the balance of Plaintiff’s and General Contractor’s claims and essentially placing them in the position of the “last defendant standing” in Plaintiff’s game of musical chairs. While this strategy may have its advantages in pressuring global resolution, the procedural implications of such a deal (if not properly executed) can be problematic if the case ultimately proceeds to trial. Therefore, it is important that counsel on both sides carefully consider the terms of any proposed settlement with an assignment before making such a commitment.

First, it is likely the settlement will need to be subject to the Court declaring it in good faith pursuant to Code of Civil Procedure section 877 et seq., which means that a valuation will have to be placed on the assignment. In the context of proving whether the settlement is in “good faith” pursuant to CCP §887.6, the value of the assigned rights is not necessarily going to be the total amount of recoverable damages assigned. In California, the Courts have approved valuations of assigned rights at 20% of the total recoverable value for those rights. See Erreca’s v. Superior Court , (1993) 19 Cal.App.4th 1475. In Errecas’s , the discounted value was deemed reasonable to account for unknown factors such as the cost of prosecuting the claims, the probability of prevailing on the claims, the likelihood of collecting on any potential judgment, and the increased difficulty in proving a negligence claim as opposed to a strict liability claim. Id. at 1496-1499. In addition to placing a value on the assignment, the monetary portion of the settlement will need to be allocated amongst Plaintiff’s claims in support of any good faith motion. The allocations and value of the assignment will inevitably play a critical role down the road with respect to Plaintiff’s ultimate recovery against the Non-Settling Subcontractors on its direct claims, so Plaintiff and the Non-Settling Subcontractor(s) should be mindful of the arguments they make during the good faith process because those same arguments will apply to the potential off sets available in relation to future jury verdicts or judgments.

Second, if the General Contractor’s Cross-Complaint is being assigned to Plaintiff, all parties need to be cognizant of the application of the assignment, and change in party positions, with relation to the pleadings on file. Pursuant to Cal. Code Civ. Proc. §368.5, when claims are assigned during a pending action, the action “may be continued in the name of the original party, or the court may allow the person to whom the transfer is made to be substituted in the action or proceeding.” Therefore, Plaintiff has the option of continuing the prosecution of the General Contractor’s Cross-Complaint against the Non-Settling Subcontractors in the name of the General Contractor, or the Plaintiff can seek to be substituted in as Cross-Complainant in place of the General Contractor. No action by the Court is required to continue a case in the name of the original party after an assignment of interest in the action. Cleverdon v. Gray, (1944) 62 Cal.App.2d 612, 616. However, if the Plaintiff wants to be substituted in place of the General Contractor, the Plaintiff must bring a motion to the Court to obtain an order for the substitution and seek leave to file a supplemental Cross-Complaint to allege the assignment and substitution. It is within the trial court’s discretion whether or not to allow the substitution. Alameda County Home Inv. Co v. Whitaker, (1933) 217 Cal. 231, 234.

Third, a change in counsel may be necessary and further actions by the General Contractor may be required. In the event of a transfer of interest in a pending action, the attorney for the nominal party/assignor does not automatically cease to be the attorney of record. Casey v. Overhead Door Corp., (1999) 74 Cal.App.4th 112. If the Plaintiff is going to continue to prosecute the Cross-Complaint in the name of the General Contractor, the Plaintiff’s attorney should substitute in as the attorney of record for the General Contractor (after Plaintiff dismisses its Complaint as to the General Contractor, of course). This is something that counsel for the General Contractor should discuss with his or her client when contemplating an assignment. The General Contractor should be aware that Plaintiff’s Counsel, who was actively prosecuting claims against the General Contractor, could potentially become the General Contractor’s counsel of record. While control of the continued litigation of the Cross-Complaint will rest solely with the Plaintiff, the General Contractor remains a nominal party to the action with exposure to the potential entry of an adverse judgment against it. Union Bank v. County of Los Angeles, (1963) 223 Cal.App.2d 687.

Although the assignment will likely include an assumption by Plaintiff of all liability in connection with the continued prosecution of the Cross-Complaint, including responsibility for all orders and/or judgments entered for or against General Contractor, further legal action by the General Contractor may be required to enforce the provisions of the assignment in the event of an adverse ruling. Conversely, further legal action by Plaintiff may be required to enforce the provisions of the assignment in the event General Contractor refuses to cooperate with Plaintiff’s requests for assistance in the form of witness testimony or documentation in support of the Cross-Complaint.

In short, an assignment of claims during the pendency of litigation can be a powerful tool in negotiating a settlement, but any counsel recommending an assignment must make sure they fully understand the terms of the assignment and advise their clients of the risks and benefits associated with such an agreement. For more information regarding assignment of claims, contact Partner Katie Brach in LGC’s San Diego office.

- LEGAL GLOSSARY

More results...

- Browse By Topic – Start Here

- Self-Help Videos

- Documents & Publications

- Find A Form

- Download E-Books

- Community Organizations

- Continuing Legal Education (MCLE)

- SH@LL Self-Help

- Free Legal Consultation (Lawyers In The Library)

- Ask a Lawyer

- Onsite Research

- Interlibrary Loan

- Document Delivery

- Borrower’s Account

- Book Catalog Search

- Passport Services

- Contact & Hours

- Library News

- Our Board of Trustees

- My E-Commerce Account

SacLaw Library

Www.saclaw.org.

- Documentary Transfer Tax

- Identifying grantors and grantees

- Free Sources

- Community Resources

Filing a Complaint to Start a Civil Lawsuit in California

This Guide provides general information and resources pertaining to filing a civil lawsuit in Sacramento County Superior Court . The steps for filing a lawsuit in other counties, small claims court, family law, probate, or a federal court are not discussed in this Guide.

Forms you may need

All cases require a Complaint. [1] In some cases, there is a fill-in-the-blanks Judicial Council form to use; in other cases, you must research and type your Complaint on 28-line pleading paper. See Step 2 below for more information about selecting complaint forms.

In addition to the Complaint, the Judicial Council forms commonly used when filing a lawsuit are:

- Civil Case Cover Sheet ( CM-010 )

- Summons ( SUM-100 )

- Alternative Dispute Resolution Information Package ( CV\E–100 )

The Sacramento County Superior Court requires two additional forms in unlimited civil cases only :

- Stipulation and Order to Mediation – Unlimited Civil ( CV-E-179 )

- Program Case Notice for Unlimited ( CV\E-143U )

Other counties may have different requirements. Check their Local Rules for information.

Steps required to file a lawsuit

Filing a lawsuit with the court is the first step any plaintiff in a civil case must take to ask the court to decide a dispute. These first papers filed with the court identify who you are suing, the basis for your lawsuit, and the court in which your lawsuit is filed. When you file the paperwork and pay the fee, the court creates a file for your case, and issues a case number.

Research your case

Prior to starting your lawsuit, you will need to research the laws related to your situation. It is essential that you research these issues, because the answers you find will help you select the proper forms or documents to start your case; determine the court where you will file your case; and identify who to name as the defendant(s) in your lawsuit. Some of the legal issues you will want to research include:

Causes of action (legal grounds for your lawsuit)

In every lawsuit, there must be at least one legal cause of action. A cause of action is the specific legal claim for which the plaintiff seeks compensation. In other words, the cause of action is the legal reason why the defendant owes the plaintiff money or other compensation. There are hundreds of available causes of action; you will want to thoroughly research your case, to ensure you’re including all the applicable causes of action.

Every cause of action comprises several “elements,” each of which you will need to prove to win your case. When researching and selecting your causes of action, you will need to pay careful attention to these elements, to determine if you have the facts and evidence necessary to prove each element.

Statutes of limitation (deadline to file the case)

A lawsuit must be filed within a limited amount of time of whatever wrongdoing is alleged in the lawsuit. This deadline is referred to as the statute of limitations. Most of these limitations are defined in the California Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) §§ 335-366.3 .

The statute of limitations for several common causes of action in California include:

- Personal injury or wrongful death: 2 years (CCP § 335.1).

- Damage to personal property: 3 years (CCP § 338).

- Breach of a written contract: 4 years (CCP § 337).

- Breach of an oral contract: 2 years (CCP § 339).

Determining the appropriate statute of limitations in a case can be deceptively complex. Additionally, research is often required to determine the exact date the statute started running.

Additional restrictions exist if the defendant is a government entity, as government entities and their employees are generally immune from lawsuits that seek damages. In some cases the government is required to waive this immunity, but only if a prospective plaintiff timely files an appropriate claim under the California Government Claims Act ( Govt. Code §§ 900 et seq . ). The time limit to file a claim is often much shorter than the statute of limitations for a private individual, typically six months or less. For more information, see our article Claims Against the Government .

Because the failure to file within the statute of limitations or failure to file a required claim in a timely manner is usually fatal to a case, one of your first research goals should be to determine the applicable statute limitations and whether a claim requirement exists in your case.

For more information on researching and calculating statutes of limitations, see our article on Statutes of Limitation .

Venue (choosing the correct court)

As a plaintiff, you have the ability to choose to file a lawsuit, and some degree of choice over where the lawsuit is filed. Typically, a lawsuit is filed in your choice of:

- The county where the real property ( i.e . land) that is the subject of the lawsuit is located ( CCP § 392 );

- The county where the accident or other wrongdoing that is the subject of the lawsuit took place ( CCP § 393 );

- The county where any defendant lives at the time the lawsuit is filed ( CCP § 395 );

- The county where the contract that is the subject of the lawsuit was to be performed ( CCP § 393 ); or

- The county where defendant corporation, LLC, or other business entity has its principal place of business ( CCP § 395.5 ).

A contract may also specify the court that will hear any disputes related to the contract.

If the lawsuit arises out of a loan or other extension of credit that was primarily for:

- personal or household use ( CCP § 395(b) ),

- a retail installment contract ( Civil Code § 1812.10 ),

- a financed automobile ( Civil Code § 2984.4 ),

the plaintiff must file and serve a Declaration or Statement of Venue, stating the facts that allow the case to be heard in the county in which the lawsuit is being filed ( CCP § 396a ). You can find a sample Declaration of Venue on our forms page here .

Complete all necessary forms

You will need to complete several forms to begin your case, including:

- Complaint (form or customized pleading, depending on type of case)

- Summons ( SUM-100 )

- Civil Case Cover Sheet (CM-010)

The Complaint is the main document you will use to initiate your lawsuit. In it, you will outline your case against the defendant; describe the legal basis for your lawsuit (your causes of action ); provide the facts giving rise to your claim; and explain what you’d like the court to order the plaintiff do, such as pay damages or perform a certain action. The specific forms or documents you will need depend on the nature of your lawsuit.

Judicial Council standardized forms

The Judicial Council has developed fill-in-the-blanks forms for a few common types of lawsuits: breach of contract and personal injury or property damage. You must include the basic Complaint and one or more Causes of Action:

Breach of Contract

Complaint- Contract (PLD-C-001) and one or more :

- Cause of Action- Breach of Contract (PLD-C-001(1) )

- Cause of Action- Common Counts ( PLD-C-001(2))

- Cause of Action- Fraud (PLD-C-001(3))

Personal Injury/Torts

Complaint- Personal Injury, Property Damage, Wrongful Death (PLD-PI-001 ) and one or more :

- Cause of Action- Motor Vehicle (PLD-PI-001(1))

- Cause of Action- General Negligence (PLD-PI-001(2))

- Cause of Action- Intentional Tort (PLD-PI-001(3))

- Cause of Action- Premises Liability (PLD-PI-001(4))

- Cause of Action- Products Liability (PLD-PI-0 01(5) )

- Exemplary Damages Attachment (PLD-PI-001(6))

For instructions on completing a Complaint using fill–in–the–blank forms, see Chapter 5 of Win Your Lawsuit ( KFC 968 .Z9 D86 (Self-Help)).

All Other Cases:

If there is no fill-in-the-blank form, you will need to research and write the complaint yourself, using 28-line pleading paper. Pleading paper pre-formatted for Sacramento County Superior Court may be downloaded from our website. You will still need the Judicial Council forms for Summons and Civil Case Cover Sheet.

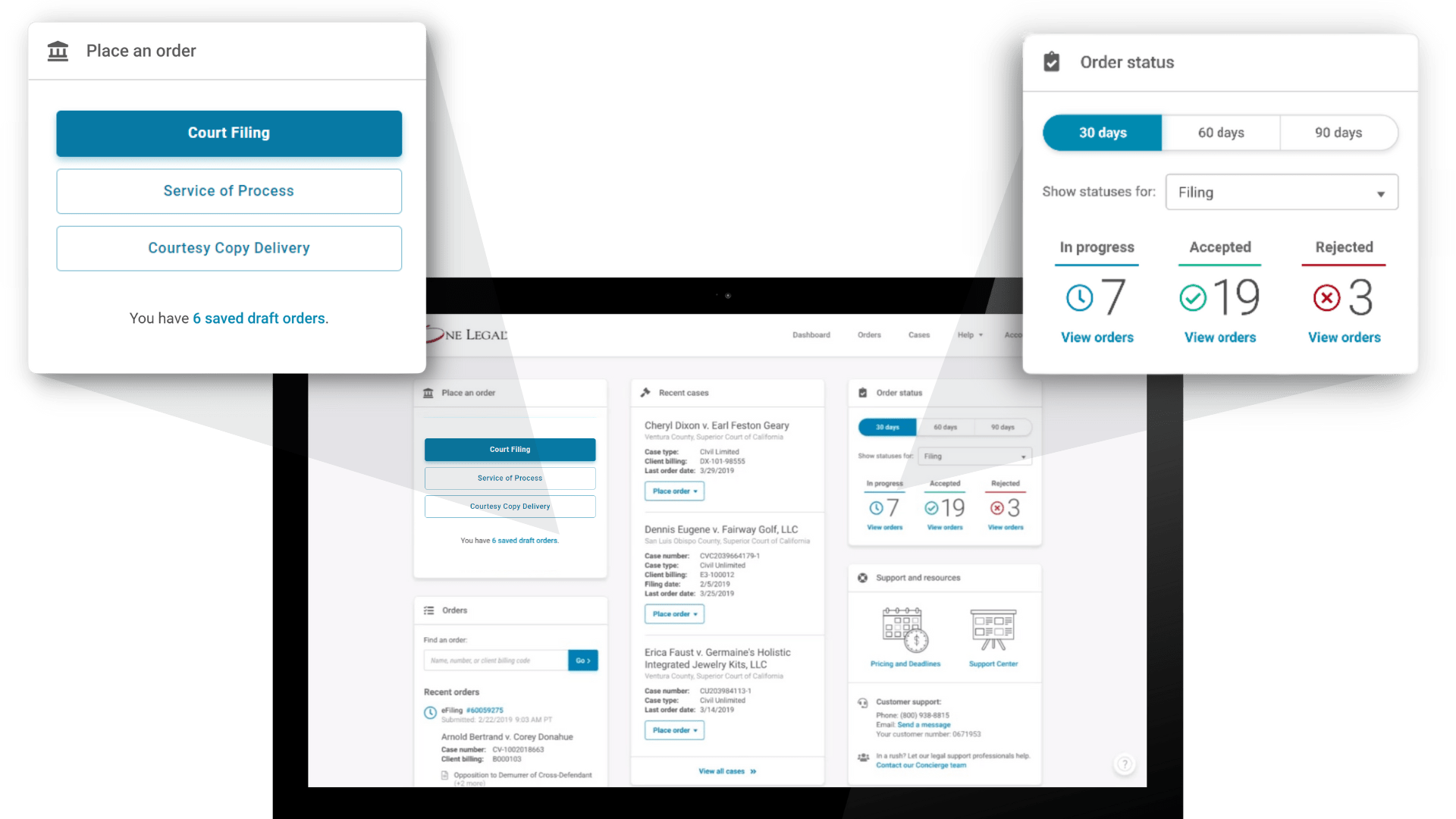

Make copies

After completing and signing your forms/pleadings, make two additional copies of your documents, and assemble your packet for filing as follows:

- Original Civil Case Cover Sheet (CM-010), and two copies, together in one packet

- Original Summons (SUM-100), and two copies, together in one packet

- Original Complaint with all causes of action and attachments, and two copies, together in one packet.

In Sacramento, the original of each multiple-page document is not stapled , while each of the copies is stapled . ( Sacramento County Superior Court Local Rule 2.02 .) Each county has its own rules regarding this, so if you are filing in another court, be sure to check that court’s rules. In counties that use physical files for documents, rather than scanning them, originals must be two-hole punched at the top of the page. Two-hole punching in Sacramento is optional.

File your documents

In Sacramento, new complaints are filed in the drop box in Room 100 on the first floor of the Gordon D. Schaber Courthouse at 720 Ninth Street in downtown Sacramento.

4.1: Determine your filing fee

The filing fees currently range between $225 and $435, depending on the type of case, and damages demanded. Current fees are available on the Sacramento County Superior Court’s fee schedule or the website of your local court. Payment must be made by check or cashier’s check only. If you qualify for a fee waiver, you may file a request with the court along with your Complaint, instead of the fee. For more information, see our guide on Fee Waivers .

Step 4.2: File your documents in the drop-box

Near the dropbox, you will find a supply of Civil Document Drop-Off Sheets and a date stamp machine. Date-stamp the back of each of your original documents. This will be the filing date of your documents.

Following the instructions posted at the drop box, place your documents in the drop box. Be sure you include:

- Civil Document Drop-Off Sheet;

- The packets you made in Step 3;

- A check or cashier’s check for the filing fee, or the Fee Waiver forms if asking the court to waive the filing fee;

- Self-addressed stamped envelope, if you want the court to return a filed/endorsed copy of these documents to you. Be sure to include sufficient postage to return your document packet.

The court will process your paperwork and scan it into the electronic filing system. This may take several weeks; the Sacramento Court’s Civil Department page lists the dates of documents currently being processed. If you included a self-addressed stamped envelope, the court will return a filed/endorsed copy to you. Otherwise, you may download endorsed copies of your documents at no charge from the Sacramento Court’s Public Portal .

Have your documents served

Once you receive the endorsed copies, you must arrange to have each defendant served. Service must be completed by someone over the age of 18, who is not a party to the case. This can be the Sheriff’s Civil Bureau, a registered process server, an attorney, or a friend or family member who is over 18 and not a party in the case.

Each defendant must be served with a stamped copy of:

- Summons (SUM-100)

- Complaint plus all causes of action

- ADR Package

If you are filing an unlimited civil case in Sacramento County, you must also serve:

- Stipulation and Order to Mediation – Unlimited Civil (CV-E-MED-179 )

- Program Case Notice for Unlimited (CV\E-143U)

You may make as many photocopies of the endorsed documents as necessary. Service of photocopies is acceptable.

The defendant must usually be served by the server handing it directly to the defendant. For more about service of the summons and complaint, see the California Courts’ guide on “Service of Court Papers.”

What’s next?

If the defendant files an Answer (or other response), the parties begin the long process of preparing for trial. There will be many more documents to file and serve throughout the lawsuit. For an overview, see our article, “ Steps in a Lawsuit .”

If the defendant does not file an answer, you can request a default judgment after their time to respond runs out. This prevents them from filing anything in the case (other than a request to set aside the default judgment). But be aware that the defendant can file an answer late if you have not yet filed your request for default . For more information, see our guides on Requesting a Default Judgment by Clerk and Requesting a Default Judgment by Court .

SH@LL (Self-Help at the Law Library) (formerly Civil Self Help Center) 609 9 th Street, Sacramento CA 95814 (916) 476-2731 (Appointment Request Line)

Services Provided: SH@LL provides general information and basic assistance to self-represented litigants on a variety of civil legal issues, including name changes. All assistance is provided by telephone. Visit “What we can help with ” for a list of qualifying cases.

Eligibility: Must be a Sacramento County resident or have a qualifying case in the Sacramento County Superior Court.

For more information

The following books have information about the process of filing and prosecuting a lawsuit, and/or information about the causes of action you may wish to include. They are all available at the Law Library.

California Civil Practice: Procedure ( KFC 995 .A65 B3 (Vol. 2, Chap. 7))

California Civil Procedure Before Trial ( KFC 995 .C34 (Vol. 2, Chap. 15)). Electronic Access: On the Law Library’s computers, using OnLaw.

California Causes of Action ( KFC 1003 .C35 ). Electronic Access: On the Law Library’s computers, using VitalLaw .

California Elements of an Action ( KFC 1003 .S74 )

California Forms of Pleading and Practice ( KFC 1010 .A65 (Ready Reference)). Electronic access: On the Law Library’s computers, using Lexis Advance . Includes common topics such as:

- Attorney Professional Liability, Vol. 7, Chap. 76

- Automobiles, Vol. 8, Chaps. 80-92

- Claim and Delivery, Vol. 12, Chap. 119

- Contract, Vol. 13, Chap. 140

- Conversion, Vol. 13, Chap. 150

- Injunctions, Vol. 26, Chap. 303

- Libel and Slander, Vol. 30, Chap. 340

- Medical Malpractice, Vol. 36, Chap. 415

- Negligence, Vol. 33, Chap. 380

- Partition of Real Property, Vol. 35, Chap. 397

- Premises Liability, Vol. 36, Chap. 421

- Products Liability, Vol. 40, Chap. 460

California Jurisprudence 3d (CalJur 3d) ( KFC 80 .C35 (Ready Reference))

California Practice Guide: Civil Procedure Before Trial ( KFC 995 .W45 (Vol. 1, Chap. 6; Forms Volume, Chap. 6))

California Practice Guide: Civil Procedure Before Trial: Statutes of Limitations ( KFC 995 .W45)

California Practice Guide: Civil Procedure Before Trial: Claims and Defenses ( KFC 995 .W45 )

Litigation By the Numbers ( KFC 995 .G67 (Chap. 1))

Win Your Lawsuit ( KFC 968 .Z9 D86 (Self-Help))

- A few types of specialized cases require a Petition. These always require additional research and are not covered in this guide. ↑

This material is intended as general information only. Your case may have factors requiring different procedures or forms. The information and instructions are provided for use in the Sacramento County Superior Court. Please keep in mind that each court may have different requirements. If you need further assistance consult a lawyer.

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Bush v. Superior Court (Rains) (1992)

WILLIAM BUSH et al., Petitioners, v. THE SUPERIOR COURT OF SACRAMENTO COUNTY, Respondent; D. W. RAINS et al., Real Parties in Interest.

(Superior Court of Sacramento County, No. 516498, Joe S. Gray, Judge.)

(Opinion by Blease, Acting P. J., with Sims and Scotland, JJ., concurring.) [10 Cal. App. 4th 1375]

Wilke, Fleury, Hoffelt, Gould & Birney, Philip R. Birney, Peter J. Pullen, Hardy, Erich, Brown & Wilson and John Quincy Brown III for Petitioners.

No appearance for Respondent.

Shernoff, Bidart & Darras, Randy D. Curry and William M. Shernoff for Real Parties in Interest.

BLEASE, Acting P. J

In this mandamus proceeding we decide that plaintiffs (the Rains) may settle their claims against one concurrent tortfeasor by taking as part of the settlement an assignment of that tortfeasor's American Motorcycle fn. 1 claim for equitable indemnity against other concurrent tortfeasors. The petitioners are defendants in an action brought by the Rains as assignees of the American Motorcycle claim. Petitioners seek relief from the overruling of their demurrers. They say the assignment violates public policy and the action should be abated because there is another action pending on the same cause of action, the Rains' personal injury tort action against them. We issued an alternative writ of mandate to consider the novel questions of law posed.

We will deny the petition. The California rule is that a chose in action is presumptively assignable ( Civ. Code, §§ 953, 954) and petitioners have shown no good reason why they should be excepted from its application.

Petitioners' most troublesome claim is that if the Rains prevail in both the indemnity and tort actions they will recover more than full compensation for their injuries because the assignment has value only if the settling tortfeasor paid more for the Rains' injuries than is warranted by its comparative share of fault. The rhetorical force of this argument lies in the failure to recognize that in the indemnity action the Rains stand in the shoes of the settling party; it is the settling party's money that is in issue. If the assignment has value it is the petitioners who seek a windfall, an offset of the excess paid by the settling party which is attributable to petitioners' share of fault.

Thus, we will reject petitioners' claim for two reasons. First, if such a recovery occurs it will not be at the expense of petitioners-the most they [10 Cal. App. 4th 1379] will be asked to bear is "liability for damage ... in direct proportion to their respective fault," the same exposure to liability that existed before the assignment. (Li v. Yellow Cab Co. (1975) 13 Cal. 3d 804 , 813 [119 Cal. Rptr. 858, 532 P.2d 1226, 78 A.L.R.3d 393], italics added.) The Rains would receive by means of the assignment only that to which the settling tortfeasor was entitled. Second, the policy against overcompensation does not outweigh the policy of fostering settlement which is advanced by permitting such an assignment.

Facts and Procedural Background

In light of the generic nature of petitioners' claims the necessary background may be stated briefly. After their home burned, D. W. and O. L. Rains, real parties in interest, sued their fire insurance carrier, State Farm Fire and Casualty Insurance Company (State Farm), alleging that in bad faith it failed to pay benefits due them under the insurance policy and that O. L. Rains suffered consequential and severe emotional distress. In a separate action O. L. Rains sued petitioners Robert Wright and William Bush for medical malpractice and American Therapeutics, Inc., for products liability alleging that permanent physical injuries arose from the side effects of a drug prescribed in the treatment of the emotional distress.

The Rains settled the bad faith action with State Farm for $1,750,000 and an assignment of its claims against the petitioners and American Therapeutics, Inc., for equitable indemnity. The Rains then filed the complaint in this action for the amount paid by State Farm to them which is attributable to petitioners' comparative fault. Petitioners demurred on grounds that the complaint failed to state a cause of action and that there is another action pending between the same parties on the same cause of action. The superior court overruled the demurrers.

Introduction

In Li v. Yellow Cab Co., supra, 13 Cal. 3d 804 , the California Supreme Court discarded the common law rule under which a plaintiff's contributory negligence barred recovery in tort. It adopted a rule of comparative negligence, "a system under which liability for damage will be borne by those whose negligence caused it in direct proportion to their respective fault." (Id. at p. 813, fn. omitted.) In American Motorcycle, supra, 20 Cal. 3d 578 , it discarded the analogous all-or-nothing cause of action for equitable indemnity between tortfeasors and replaced it with a rule of partial indemnity. "In [10 Cal. App. 4th 1380] order to attain [the system envisioned in Li], in which liability for an indivisible injury caused by concurrent tortfeasors will be borne by each individual tortfeasor 'in direct proportion to [his] respective fault,' we conclude that the current equitable indemnity rule should be modified to permit a concurrent tortfeasor to obtain partial indemnity from other concurrent tortfeasors on a comparative fault basis." (Id. at p. 598.)

The issues are whether such a cause of action lawfully may be assigned to the plaintiff, and if so, whether an action upon the assignment can be maintained when the plaintiff is also suing other concurrent tortfeasors on the underlying tort. Petitioners contend that in these circumstances an action on the assignment would offend traditional principles of equity and indemnity and violate public policy.

A. An American Motorcycle Claim Is Assignable to a Third Party.

[1] The right to equitable indemnity stems from the principle that one who has been compelled to pay damages which ought to have been paid by another wrongdoer may recover from that wrongdoer. [2a] Petitioners argue that the Rains' complaint is deficient because it fails to plead that they were compelled to pay damages. The argument neglects the elementary consideration that an assignee of a chose in action does not sue in his own right but stands in the shoes of the assignor. (See, e.g., Brown v. Guarantee Ins. Co. (1957) 155 Cal. App. 2d 679 , 695-696 [319 P.2d 69, 66 A.L.R.2d 1202].) A thing or chose in action would never be assignable if the assignee independently had to meet the requirements already satisfied by the assignor. If he could meet the requirements he would need no assignment; if not he could not use the assignment.

Under the early English common law the doctrines of champerty and maintenance prohibited an assignment of a chose in action. (See, e.g., 14 Am.Jur.2d, Champerty and Maintenance, § 1, p. 842.) In California this common law doctrine has been superceded by statute. [3] " [S]ections 953 and 954 of the Civil Code [of 1872] have lifted many of the restrictions imposed by the rule of the common law upon this subject." (Wikstrom v. Yolo Fliers Club (1929) 206 Cal. 461, 464 [274 P. 959]; Jackson v. Deauville Holding Co. (1933) 219 Cal. 498, 501 [27 P.2d 643].) These presently provide: "A thing in action is a right to recover money or other personal property by a judicial proceeding." ( Civ. Code, § 953.) "A thing in action, arising out of the violation of a right of property, or out of an obligation, may be transferred by the owner." ( Civ. Code, §§ 954, 1458.) [10 Cal. App. 4th 1381]

These statutes establish the policy of the state, the " 'assignability of things [in action] is now the rule; nonassignability, the exception; and this exception is confined to wrongs done to the person, the reputation, or the feelings of the injured party. ...' " (Webb v. Pillsbury (1943) 23 Cal. 2d 324 , 327 [144 P.2d 1, 150 A.L.R. 504], brackets in Webb; see also Wikstrom, supra, 206 Cal. at p. 463; Jackson, supra, 219 Cal. at p. 500.) [2b] For this reason it is petitioners' burden to show that some exception to the rule applies in this case. They fail to do so.

They argue that no precedent has "authorized" a plaintiff in a tort action to acquire an American Motorcycle claim by assignment. They offer nothing to suggest that such a claim is per se unassignable, e.g., unassignable to a bona fide third party purchaser. The thing assigned is not a wrong which is personal to the holder of the right of indemnity, as is shown by analogous rights which have been held assignable. [4] For example, a subrogation right is assignable. (See, e.g., Quinn v. Warnes (1983) 144 Cal. App. 3d 309 [ 192 Cal. Rptr. 660 ], upholding an assignment of subrogation rights by a worker's compensation insurance carrier to the third party tort defendant.)

A subrogation right bears a strong resemblance to the right to equitable indemnity sanctioned by American Motorcycle.

"Subrogation is an equitable remedy which arises under the following basic circumstances: (1) The obligor (defendant) owes a debt or duty of some kind to the creditor (subrogor). (2) The subrogee (plaintiff), pursuant to his own obligation to the creditor, pays that debt or discharges that duty. (3) These circumstances make it inequitable that the subrogee should bear the loss while the obligor is unjustly enriched." (4 Witkin, Cal. Procedure (3d ed. 1985) Pleading, § 112, p. 147, original italics.) Under American Motorcycle the tortfeasor from whom the plaintiff first recovers is in effect a subrogee, entitled to recover insofar as it has borne liability for damages attributable to the fault of other concurrent tortfeasors.

Another analogous remedy is contribution. (See 4 Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence (5th ed. 1941) § 1416, p. 1070.) While we have found no California authority on point, out-of-state cases hold that such a chose in action is assignable. (See, e.g., McKay v. Citizens Rapid Transit Co. (1950) 190 Va. 851 [59 S.E.2d 121, 20 A.L.R.2d 918].)

[2c] Thus, if the assignment of an American Motorcycle claim offends traditional doctrines of indemnity it must arise from the status of the assignee as the plaintiff in the tort action rather than the fact of assignment per se. [10 Cal. App. 4th 1382] B. Assignment of an American Motorcycle Claim to a Tort Plaintiff Offends No Traditional Principle of Indemnity.

The Rains rely on Fortman v. Safeco Ins. Co. (1990) 221 Cal. App. 3d 1394 [ 271 Cal. Rptr. 117 ] as a precedent upholding an "assignment of a cause of action for equitable indemnity" to the tort plaintiff. In that case the plaintiff in a tort action settled with the defendant and his excess insurance coverage carrier; the latter settlement was for $1,125,000 of its $2 million policy limits and an assignment of its equitable subrogation claim against the defendant's primary insurer. The primary insurer had repeatedly rejected settlement offers within the primary insurance policy limits. (Id. at pp. 1396-1397.) While Fortman is an example of an assignment of a subrogation claim to the original obligor, it furnishes little precedential support because the issue whether such an assignment could be made was not discussed.

[5] (See fn. 2.) However, Fortman does point to a closely related claim as to which assignment to the tort plaintiff has been sanctioned by case law, a first party insurance bad faith claim. fn. 2