Mixed methods research: what it is and what it could be

- Open access

- Published: 29 March 2019

- Volume 48 , pages 193–216, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Rob Timans 1 ,

- Paul Wouters 2 &

- Johan Heilbron 3

123k Accesses

98 Citations

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 06 May 2019

This article has been updated

Combining methods in social scientific research has recently gained momentum through a research strand called Mixed Methods Research (MMR). This approach, which explicitly aims to offer a framework for combining methods, has rapidly spread through the social and behavioural sciences, and this article offers an analysis of the approach from a field theoretical perspective. After a brief outline of the MMR program, we ask how its recent rise can be understood. We then delve deeper into some of the specific elements that constitute the MMR approach, and we engage critically with the assumptions that underlay this particular conception of using multiple methods. We conclude by offering an alternative view regarding methods and method use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mixed Methods

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

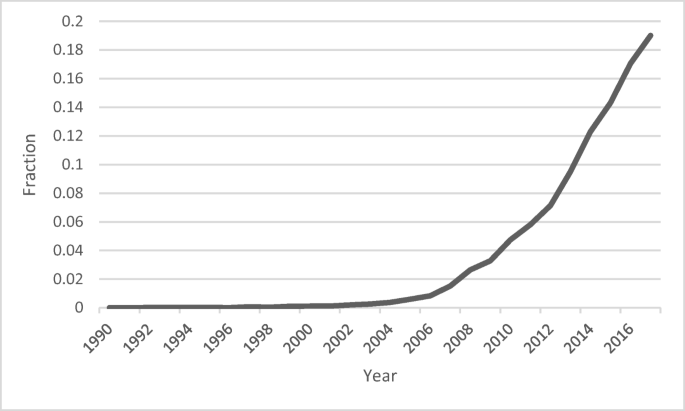

The interest in combining methods in social scientific research has a long history. Terms such as “triangulation,” “combining methods,” and “multiple methods” have been around for quite a while to designate using different methods of data analysis in empirical studies. However, this practice has gained new momentum through a research strand that has recently emerged and that explicitly aims to offer a framework for combining methods. This approach, which goes by the name of Mixed Methods Research (MMR), has rapidly become popular in the social and behavioural sciences. This can be seen, for instance, in Fig. 1 , where the number of publications mentioning “mixed methods” in the title or abstract in the Thomson Reuters Web of Science is depicted. The number increased rapidly over the past ten years, especially after 2006. Footnote 1

Fraction of the total of articles mentioning Mixed Method Research appearing in a given year, 1990–2017 (yearly values sum to 1). See footnote 1

The subject of mixed methods thus seems to have gained recognition among social scientists. The rapid rise of the number of articles mentioning the term raises various sociological questions. In this article, we address three of these questions. The first question concerns the degree to which the approach of MMR has become institutionalized within the field of the social sciences. Has MMR become a recognizable realm of knowledge production? Has its ascendance been accompanied by the production of textbooks, the founding of journals, and other indicators of institutionalization? The answer to this question provides an assessment of the current state of MMR. Once that is determined, the second question is how MMR’s rise can be understood. Where does the approach come from and how can its emergence and spread be understood? To answer this question, we use Pierre Bourdieu’s field analytical approach to science and academic institutions (Bourdieu 1975 , 1988 , 2004 , 2007 ; Bourdieu et al. 1991 ). We flesh out this approach in the next section. The third question concerns the substance of the MMR corpus seen in the light of the answers to the previous questions: how can we interpret the specific content of this approach in the context of its socio-historical genesis and institutionalization, and how can we understand its proposal for “mixing methods” in practice?

We proceed as follows. In the next section, we give an account of our theoretical approach. Then, in the third, we assess the degree of institutionalization of MMR, drawing on the indicators of academic institutionalization developed by Fleck et al. ( 2016 ). In the fourth section, we address the second question by examining the position of the academic entrepreneurs behind the rise of MMR. The aim is to understand these agents’ engagement in MMR, as well as its distinctive content as being informed by their position in this field. Viewing MMR as a position-taking of academic entrepreneurs, linked to their objective position in this field, allows us to reflect sociologically on the substance of the approach. We offer this reflection in the fifth section, where we indicate some problems with MMR. To get ahead of the discussion, these problems have to do with the framing of MMR as a distinct methodology and its specific conceptualization of data and methods of data analysis. We argue that these problems hinder fruitfully combining methods in a practical understanding of social scientific research. Finally, we conclude with some tentative proposals for an alternative view on combining methods.

A field approach

Our investigation of the rise and institutionalization of MMR relies on Bourdieu’s field approach. In general, field theory provides a model for the structural dimensions of practices. In fields, agents occupy a position relative to each other based on the differences in the volume and structure of their capital holdings. Capital can be seen as a resource that agents employ to exert power in the field. The distribution of the form of capital that is specific to the field serves as a principle of hierarchization in the field, differentiating those that hold more capital from those that hold less. This principle allows us to make a distinction between, respectively, the dominant and dominated factions in a field. However, in mature fields all agents—dominant and dominated—share an understanding of what is at stake in the field and tend to accept its principle of hierarchization. They are invested in the game, have an interest in it, and share the field’s illusio .

In the present case, we can interpret the various disciplines in the social sciences as more or less autonomous spaces that revolve around the shared stake in producing legitimate scientific knowledge by the standards of the field. What constitutes legitimate knowledge in these disciplinary fields, the production of which bestows scholars with prestige and an aura of competence, is in large part determined by the dominant agents in the field, who occupy positions in which most of the consecration of scientific work takes place. Scholars operating in a field are endowed with initial and accumulated field-specific capital, and are engaged in the struggle to gain additional capital (mainly scientific and intellectual prestige) in order to advance their position in the field. The main focus of these agents will generally be the disciplinary field in which they built their careers and invested their capital. These various disciplinary spaces are in turn part of a broader field of the social sciences in which the social status and prestige of the various disciplines is at stake. The ensuing disciplinary hierarchy is an important factor to take into account when analysing the circulation of new scientific products such as MMR. Furthermore, a distinction needs to be made between the academic and the scientific field. While the academic field revolves around universities and other degree-granting institutions, the stakes in the scientific field entail the production and valuation of knowledge. Of course, in modern science these fields are closely related, but they do not coincide (Gingras and Gemme 2006 ). For instance, part of the production of legitimate knowledge takes place outside of universities.

This framework makes it possible to contextualize the emergence of MMR in a socio-historical way. It also enables an assessment of some of the characteristics of MMR as a scientific product, since Bourdieu insists on the homology between the objective positions in a field and the position-takings of the agents who occupy these positions. As a new methodological approach, MMR is the result of the position-takings of its producers. The position-takings of the entrepreneurs at the core of MMR can therefore be seen as expressions in the struggles over the authority to define the proper methodology that underlies good scientific work regarding combining methods, and the potential rewards that come with being seen, by other agents, as authoritative on these matters. Possible rewards include a strengthened autonomy of the subfield of MMR and an improved position in the social-scientific field.

The role of these entrepreneurs or ‘intellectual leaders’ who can channel intellectual energy and can take the lead in institution building has been emphasised by sociologists of science as an important aspect of the production of knowledge that is visible and recognized as distinct in the larger scientific field (e.g., Mullins 1973 ; Collins 1998 ). According to Bourdieu, their position can, to a certain degree, explain the strategy they pursue and the options they perceive to be viable in the trade-off regarding the risks and potential rewards for their work.

We do not provide a full-fledged field analysis of MMR here. Rather, we use the concept as a heuristic device to account for the phenomenon of MMR in the social context in which it emerged and diffused. But first, we take stock of the current situation of MMR by focusing on the degree of institutionalization of MMR in the scientific field.

The institutionalization of mixed methods research

When discussing institutionalization, we have to be careful about what we mean by this term. More precisely, we need to be specific about the context and distinguish between institutionalization in the academic field and institutionalization within the scientific field (see Gingras and Gemme 2006 ; Sapiro et al. 2018 ). The first process refers to the establishment of degrees, curricula, faculties, etc., or to institutions tied to the academic bureaucracy and academic politics. The latter refers to the emergence of institutions that support the autonomization of scholarship such as scholarly associations and scientific journals. Since MMR is still a relatively young phenomenon and academic institutionalization tends to lag scientific institutionalization (e.g., for the case of sociology and psychology, see Sapiro et al. 2018 , p. 26), we mainly focus here on the latter dimension.

Drawing on criteria proposed by Fleck et al. ( 2016 ) for the institutionalization of academic disciplines, MMR seems to have achieved a significant degree of institutionalization within the scientific field. MMR quickly gained popularity in the first decade of the twenty-first century (e.g., Tashakkori and Teddlie 2010c , pp. 803–804). A distinct corpus of publications has been produced that aims to educate those interested in MMR and to function as a source of reference for researchers: there are a number of textbooks (e.g., Plowright 2010 ; Creswell and Plano Clark 2011 ; Teddlie and Tashakkori 2008 ); a handbook that is now in its second edition (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2003 , 2010a ); as well as a reader (Plano Clark and Creswell 2007 ). Furthermore, a journal (the Journal of Mixed Methods Research [ JMMR] ) was established in 2007. The JMMR was founded by the editors John Creswell and Abbas Tashakkori with the primary aim of “building an international and multidisciplinary community of mixed methods researchers.” Footnote 2 Contributions to the journal must “fit the definition of mixed methods research” Footnote 3 and explicitly integrate qualitative and quantitative aspects of research, either in an empirical study or in a more theoretical-methodologically oriented piece.

In addition, general textbooks on social research methods and methodology now increasingly devote sections to the issue of combining methods (e.g., Creswell 2008 ; Nagy Hesse-Biber and Leavy 2008 ; Bryman 2012 ), and MMR has been described as a “third paradigm” (Denscombe 2008 ), a “movement” (Bryman 2009 ), a “third methodology” (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2010b ), a “distinct approach” (Greene 2008 ) and an “emerging field” (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2011 ), defined by a common name (that sets it apart from other approaches to combining methods) and shared terminology (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2010b , p. 19). As a further indication of institutionalization, a research association (the Mixed Methods International Research Association—MMIRA) was founded in 2013 and its inaugural conference was held in 2014. Prior to this, there have been a number of conferences on MMR or occasions on which MMR was presented and discussed in other contexts. An example of the first is the conference on mixed method research design held in Basel in 2005. Starting also in 2005, the British Homerton School of Health Studies has organised a series of international conferences on mixed methods. Moreover, MMR was on the list of sessions in a number of conferences on qualitative research (see, e.g., Creswell 2012 ).

Another sign of institutionalization can be found in efforts to forge a common disciplinary identity by providing a narrative about its history. This involves the identification of precursors and pioneers as well as an interpretation of the process that gave rise to a distinctive set of ideas and practices. An explicit attempt to chart the early history of MMR is provided by Johnson and Gray ( 2010 ). They frame MMR as rooted in the philosophy of science, particularly as a way of thinking about science that has transcended some of the most salient historical oppositions in philosophy. Philosophers like Aristotle and Kant are portrayed as thinkers who sought to integrate opposing stances, forwarding “proto-mixed methods ideas” that exhibited the spirit of MMR (Johnson and Gray 2010 , p. 72, p. 86). In this capacity, they (as well as other philosophers like Vico and Montesquieu) are presented as part of MMR providing a philosophical validation of the project by presenting it as a continuation of ideas that have already been voiced by great thinkers in the past.

In the second edition of their textbook, Creswell and Plano Clark ( 2011 ) provide an overview of the history of MMR by identifying five historical stages: the first one being a precursor to the MMR approach, consisting of rather atomised attempts by different authors to combine methods in their research. For Creswell and Plano Clark, one of the earliest examples is Campbell and Fiske’s ( 1959 ) combination of quantitative methods to improve the validity of psychological scales that gave rise to the triangulation approach to research. However, they regard this and other studies that combined methods around that time, as “antecedents to (…) more systematic attempts to forge mixed methods into a complete research design” (Creswell and Plano Clark 2011 , p. 21), and hence label this stage as the “formative period” (ibid., p. 25). Their second stage consists of the emergence of MMR as an identifiable research strand, accompanied by a “paradigm debate” about the possibility of combining qualitative and quantitative data. They locate its beginnings in the late 1980s when researchers in various fields began to combine qualitative and quantitative methods (ibid., pp. 20–21). This provoked a discussion about the feasibility of combining data that were viewed as coming from very different philosophical points of view. The third stage, the “procedural development period,” saw an emphasis on developing more hands-on procedures for designing a mixed methods study, while stage four is identified as consisting of “advocacy and expansion” of MMR as a separate methodology, involving conferences, the establishment of a journal and the first edition of the aforementioned handbook (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2003 ). Finally, the fifth stage is seen as a “reflective period,” in which discussions about the unique philosophical underpinnings and the scientific position of MMR emerge.

Creswell and Plano Clark thus locate the emergence of “MMR proper” at the second stage, when researchers started to use both qualitative and quantitative methods within a single research effort. As reasons for the emergence of MMR at this stage they identify the growing complexity of research problems, the perception of qualitative research as a legitimate form of inquiry (also by quantitative researchers) and the increasing need qualitative researchers felt for generalising their findings. They therefore perceive the emergence of the practice of combining methods as a bottom up process that grew out of research practices, and at some point in time converged towards a more structural approach. Footnote 4 Historical accounts such as these add a cognitive dimension to the efforts to institutionalize MMR. They lay the groundwork for MMR as a separate subfield with its own identity, topics, problems and intellectual history. The use of terms such as “third paradigm” and “third methodology” also suggests that there is a tendency to perceive and promote MMR as a distinct and coherent way to do research.

In view of the brief exploration of the indicators of institutionalisation of MMR, it seems reasonable to conclude that MMR has become a recognizable and fairly institutionalized strand of research with its own identity and profile within the social scientific field. This can be seen both from the establishment of formal institutions (like associations and journals) and more informal ones that rely more on the tacit agreement between agents about “what MMR is” (an example of this, which we address later in the article, is the search for a common definition of MMR in order to fix the meaning of the term). The establishment of these institutions supports the autonomization of MMR and its emancipation from the field in which it originated, but in which it continues to be embedded. This way, it can be viewed as a semi-autonomous subfield within the larger field of the social sciences and as the result of a differentiation internal to this field (Steinmetz 2016 , p. 109). It is a space that is clearly embedded within this higher level field; for example, members of the subfield of MMR also qualify as members of the overarching field, and the allocation of the most valuable and current form of capital is determined there as well. Nevertheless, as a distinct subfield, it also has specific principles that govern the production of knowledge and the rewards of domination.

We return to the content and form of this specific knowledge later in the article. The next section addresses the question of the socio-genesis of MMR.

Where does mixed methods research come from?

The origins of the subfield of MMR lay in the broader field of social scientific disciplines. We interpret the positions of the scholars most involved in MMR (the “pioneers” or “scientific entrepreneurs”) as occupying particular positions within the larger academic and scientific field. Who, then, are the researchers at the heart of MMR? Leech ( 2010 ) interviewed 4 scholars (out of 6) that she identified as early developers of the field: Alan Bryman (UK; sociology), John Creswell (USA; educational psychology), Jennifer Greene (USA; educational psychology) and Janice Morse (USA; nursing and anthropology). Educated in the 1970s and early 1980s, all four of them indicated that they were initially trained in “quantitative methods” and later acquired skills in “qualitative methods.” For two of them (Bryman and Creswell) the impetus to learn qualitative methods was their involvement in writing on, and teaching of, research methods; for Greene and Morse the initial motivation was more instrumental and related to their concrete research activity at the time. Creswell describes himself as “a postpositivist in the 1970s, self-education as a constructivist through teaching qualitative courses in the 1980s, and advocacy for mixed methods (…) from the 1990s to the present” (Creswell 2011 , p. 269). Of this group, only Morse had the benefit of learning about qualitative methods as part of her educational training (in nursing and anthropology; Leech 2010 , p. 267). Independently, Creswell ( 2012 ) identified (in addition to Bryman, Greene and Morse) John Hunter, Allen Brewer (USA; Northwestern and Boston College) and Nigel Fielding (University of Surrey, UK) as important early movers in MMR.

The selections that Leech and Creswell make regarding the key actors are based on their close involvement with the “MMR movement.” It is corroborated by a simple analysis of the articles that appeared in the Journal of Mixed Methods Research ( JMMR ), founded in 2007 as an outlet for MMR.

Table 1 lists all the authors that have published in the issues of the journal since its first publication in 2007 and that have either received more than 14 (4%) of the citations allocated between the group of 343 authors (the TLCS score in Table 1 ), or have written more than 2 articles for the Journal (1.2% of all the articles that have appeared from 2007 until October 2013) together with their educational background (i.e., the discipline in which they completed their PhD).

All the members of Leech’s selection, except for Morse, and the members of Creswell’s selection (except Hunter, Brewer, and Fielding) are represented in the selection based on the entries in the JMMR . Footnote 5 The same holds for two of the three additional authors identified by Creswell. Hunter and Brewer have developed a somewhat different approach to combining methods that explicitly targets data gathering techniques and largely avoids epistemological discussions. In Brewer and Hunter ( 2006 ) they discuss the MMR approach very briefly and only include two references in their bibliography to the handbook of Tashakkori and Teddlie ( 2003 ), and at the end of 2013 they had not published in the JMMR . Fielding, meanwhile, has written two articles for the JMMR (Fielding and Cisneros-Puebla 2009 ; Fielding 2012 ). In general, it seems reasonable to assume that a publication in a journal that positions itself as part of a systematic attempt to build a research tradition, and can be viewed as part of a strategic effort to advance MMR as a distinct alternative to more “traditional” academic research—particularly in methods—at least signals a degree of adherence to the effort and acceptance of the rules of the game it lays out. This would locate Fielding closer to the MMR movement than the others.

The majority of the researchers listed in Table 1 have a background in psychology or social psychology (35%), and sociology (25%). Most of them work in the United States or are UK citizens, and the positions they occupied at the beginning of 2013 indicates that most of these are in applied research: educational research and educational psychology account for 50% of all the disciplinary occupations of the group that were still employed in academia. This is consistent with the view that MMR originated in applied disciplines and thematic studies like education and nursing, rather than “pure disciplines” like psychology and sociology (Tashakkori and Teddlie ( 2010b ), p. 32). Although most of the 20 individuals mentioned in Table 1 have taught methods courses in academic curricula (for 15 of them, we could determine that they were involved in the teaching of qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), there are few individuals with a background in statistics or a neighbouring discipline: only Amy Dellinger did her PhD in “research methodology.” In addition, as far as we could determine, only three individuals held a position in a methodological department at some time: Dellinger, Tony Onwuegbuzie, and Nancy Leech.

The pre-eminence of applied fields in MMR is supported when we turn our attention to the circulation of MMR. To assess this we proceeded as follows. We selected 10 categories in the Web of Science that form a rough representation of the space of social science disciplines, taking care to include the most important so-called “studies.” These thematically orientated, interdisciplinary research areas have progressively expanded since they emerged at the end of the 1960s as a critique of the traditional disciplines (Heilbron et al. 2017 ). For each category, we selected the 10 journals with the highest 5-year impact factor in their category in the period 2007–2015. The lists were compiled bi-annually over this period, resulting in 5 top ten lists for the following Web of Science categories: Economics, Psychology, Sociology, Anthropology, Political Science, Nursing, Education & Educational Research, Business, Cultural Studies, and Family Studies. After removing multiple occurring journals, we obtained a list of 164 journals.

We searched the titles and abstracts of the articles appearing in these journals over the period 1992–2016 for occurrences of the terms “mixed method” or “multiple methods” and variants thereof. We chose this particular period and combination of search terms to see if a shift from a more general use of the term “multiple methods” to “mixed methods” occurred following the institutionalization of MMR. In total, we found 797 articles (out of a total of 241,521 articles that appeared in these journals during that time), published in 95 different journals. Table 2 lists the 20 journals that contain at least 1% (8 articles) of the total amount of articles.

As is clear from Table 2 , the largest number of articles in the sample were published in journals in the field of nursing: 332 articles (42%) appeared in journals that can be assigned to this category. The next largest category is Education & Educational Research, to which 224 (28 percentage) of the articles can be allocated. By contrast, classical social science disciples are barely represented. In Table 2 only the journal Field Methods (Anthropology) and the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (Psychology) are related to classical disciplines. In Table 3 , the articles in the sample are categorized according to the disciplinary category of the journal in which they appeared. Overall, the traditional disciplines are clearly underrepresented: for the Economics category, for example, only the Journal of Economic Geography contains three articles that make a reference to mixed methods.

Focusing on the core MMR group, the top ten authors of the group together collect 458 citations from the 797 articles in the sample, locating them at the center of the citation network. Creswell is the most cited author (210 citations) and his work too receives most citations from journals in nursing and education studies.

The question whether a terminological shift has occurred from “multiple methods” to “mixed methods” must be answered affirmative for this sample. Prior to 2001 most articles (23 out of 31) refer to “multiple methods” or “multi-method” in their title or abstract, while the term “mixed methods” gains traction after 2001. This shift occurs first in journals in nursing studies, with journals in education studies following somewhat later. The same fields are also the first to cite the first textbooks and handbooks of MMR.

Taken together, these results corroborate the notion that MMR circulates mainly in nursing and education studies. How can this be understood from a field theoretical perspective? MMR can be seen as an innovation in the social scientific field, introducing a new methodology for combining existing methods in research. In general, innovation is a relatively risky strategy. Coming up with a truly rule-breaking innovation often involves a small probability of great success and a large probability of failure. However, it is important to add some nuance to this general observation. First, the risk an innovator faces depends on her position in the field. Agents occupying positions at the top of their field’s hierarchy are rich in specific capital and can more easily afford to undertake risky projects. In the scientific field, these are the agents richest in scientific capital. They have the knowledge, authority, and reputation (derived from recognition by their peers; Bourdieu 2004 , p. 34) that tends to decrease the risk they face and increase the chances of success. Moreover, the positions richest in scientific capital will, by definition, be the most consecrated ones. This consecration involves scientific rather than academic capital (cf. Wacquant 2013 , p. 20) and within disciplines these consecrated positions often are related to orthodox position-takings. This presents a paradox: although they have the capital to take more risks, they have also invested heavily in the orthodoxy of the field and will thus be reluctant to upset the status quo and risk destroying the value of their investment. This results in a tendency to take a more conservative stance, aimed at preserving the status quo in the field and defending their position. Footnote 6

For agents in dominated positions this logic is reversed. Possessing less scientific capital, they hold less consecrated positions and their chances of introducing successful innovations are much lower. This leaves them too with two possible strategies. One is to revert to a strategy of adaptation, accepting the established hierarchy in the field and embarking on a slow advancement to gain the necessary capital to make their mark from within the established order. However, Bourdieu notes that sometimes agents with a relatively marginal position in the field will engage in a “flight forward” and pursue higher risk strategies. Strategies promoting a heterodox approach challenge the orthodoxy and the principles of hierarchization of the field, and, if successful (which will be the case only with a small probability), can rake in significant profits by laying claim to a new orthodoxy (Bourdieu 1975 , p. 104; Bourdieu 1993 , pp. 116–117).

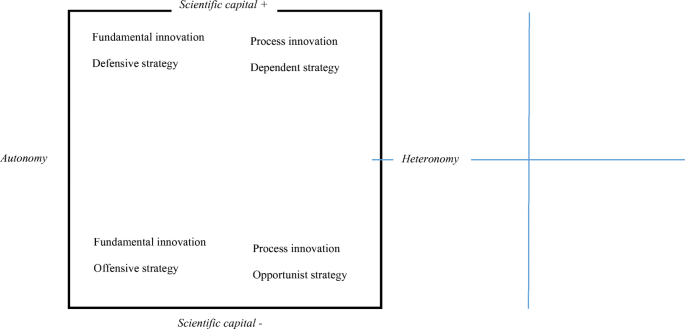

Thus, the coupling of innovative strategies to specific field positions based on the amount of scientific capital alone is not straightforward. It is therefore helpful to introduce a second differentiation in the field that, following Bourdieu ( 1975 , p. 103), is based on the differences between the expected profits from these strategies. Here a distinction can be made between an autonomous and a heteronomous pole of the field, i.e., between the purest, most “disinterested” positions and the most “temporal” positions that are more pervious to the heteronomous logic of social hierarchies outside the scientific field. Of course, this difference is a matter of degree, as even the works produced at the most heteronomous positions still have to adhere to the standards of the scientific field to be seen as legitimate. But within each discipline this dimension captures the difference between agents predominantly engaged in fundamental, scholarly work—“production solely for the producers”—and agents more involved in applied lines of research. The main component of the expected profit from innovation in the first case is scientific, whereas in the second case the balance tends to shift towards more temporal profits. This two-fold structuring of the field allows for a more nuanced conception of innovation than the dichotomy “conservative” versus “radical.” Holders of large amounts of scientific capital at the autonomous pole of the field are the producers and conservators of orthodoxy, producing and diffusing what can be called “orthodox innovations” through their control of relatively powerful networks of consecration and circulation. Innovations can be radical or revolutionary in a rational sense, but they tend to originate from questions raised by the orthodoxy of the field. Likewise, the strategy to innovate in this sense can be very risky in that success is in no way guaranteed, but the risk is mitigated by the assurance of peers that these are legitimate questions, tackled in a way that is consistent with orthodoxy and that does not threaten control of the consecration and circulation networks.

These producers are seen as intellectual leaders by most agents in the field, especially by those aspiring to become part of the specific networks of production and circulation they maintain. The exception are the agents located at the autonomous end of the field who possess less scientific capital and outright reject this orthodoxy produced by the field’s elite. Being strictly focused on the most autonomous principles of legitimacy, they are unable to accommodate and have no choice but to reject the orthodoxy. Their only hope is to engage in heterodox innovations that may one day become the new orthodoxy.

The issue is less antagonistic at the heteronomous side of the field, at least as far as the irreconcilable position-takings at the autonomous pole are concerned. The main battle here is also for scientific capital, but is complemented by the legitimacy it brings to gain access to those who are in power outside of the scientific field. At the dominant side, those with more scientific capital tend to have access to the field of power, agents who hold the most economic and cultural capital, for example by holding positions in policy advisory committees or company boards. The dominated groups at this side of the field will cater more to practitioners or professionals outside of the field of science.

Overall, there will be fewer innovations on this side. Moreover, innovative strategies will be less concerned with the intricacies of the pure discussions that prevail at the autonomous pole and be of a more practical nature, but pursued from different degrees of legitimacy according to the differences in scientific capital. This affects the form these more practical, process-orientated innovations take. At the dominant side of this pole, agents tend to accept the outcome of the struggles at the autonomous pole: they will accept the orthodoxy because mastery of this provides them with scientific capital and the legitimacy they need to gain access to those in power. In contrast, agents at the dominated side will be more interested in doing “what works,” neutralizing the points of conflict at the autonomous pole and deriving less value from strictly following the orthodoxy. This way, a four-fold classification of innovative strategies in the scientific field emerges (see Fig. 2 ) that helps to understand the context in which MMR was developed.

Scientific field and scientific innovation

In summary, the small group of researchers who have been identified as the core of MMR consist predominantly of users of methods, who were educated and have worked exclusively at US and British universities. The specific approach to combining methods that is proposed by MMR has been successful from an institutional point of view, achieving visibility through the foundation of a journal and association and a considerable output of core MMR scholars in terms of books, conference proceedings, and journal articles. Its origins and circulation in vocational studies rather than classical academic disciplines can be understood from the position these studies occupy in the scientific field and the kinds of position-taking and innovations these positions give rise to. This context allows a reflexive understanding of the content of MMR and the issues that are dominant in the approach. We turn to this in the next section.

Mixed methods research: Position-taking

The position of the subfield of MMR in the scientific field is related to the position-takings of agents that form the core of this subfield (Bourdieu 1993 , p. 35). The space of position takings, in turn, provides the framework to study the most salient issues that are debated within the subfield. Since we can consider MMR to be an emerging subfield, where positions and position takings are not as clearly defined as in more mature and settled fields, it comes as no surprise that there is a lively discussion of fundamental matters. Out of the various topics that are actively discussed, we have distilled three themes that are important for the way the subfield of MMR conveys its autonomy as a field and as a distinct approach to research. Footnote 7 In our view, these also represent the main problems with the way MMR approaches the issue of combining methods.

Methodology making and standardization

The first topic is that the approach is moving towards defining a unified MMR methodology. There are differences in opinion as to how this is best achieved, but there is widespread agreement that some kind of common methodological and conceptual foundation of MMR is needed. To this end, some propose a broad methodology that can serve as distinct marker of MMR research. For instance, in their introduction to the handbook, Tashakkori and Teddlie ( 2010b ) propose a definition of the methodology of mixed methods research as “the broad inquiry logic that guides the selection of specific methods and that is informed by conceptual positions common to mixed methods practitioners” (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2010b , p. 5). When they (later on in the text) provide two methodological principles that differentiate MMR from other communities of scholars, they state that they regard it as a “crucial mission” for the MMR community to generate distinct methodological principles (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2010b , pp. 16–17). They envision an MMR methodology that can function as a “guide” for selecting specific methods. Others are more in favour of finding a philosophical foundation that underlies MMR. For instance, Morgan ( 2007 ) and Hesse-Biber ( 2010 ) consider pragmatism as a philosophy that distinguishes MMR from qualitative (constructivism) and quantitative (positivist) research and that can provide a rationale for the paradigmatic pluralism typical of MMR.

Furthermore, there is wide agreement that some unified definition of MMR would be beneficial, but it is precisely here that there is a large variation in interpretations regarding the essentials of MMR. This can be seen in the plethora of definitions that have been proposed. Johnson et al. ( 2007 ) identified 19 alternative definitions of MMR at the time, out of which they condensed their own:

[MMR] is the type of research in which a researcher or team of researchers combines elements of qualitative and quantitative research approaches (e.g., use of qualitative and quantitative viewpoints, data collection, analysis, inference techniques) for the broad purpose of breath and depth of understanding and corroboration. Footnote 8

Four years later, the issue is not settled yet. Creswell and Plano Clark ( 2011 ) list a number of authors who have proposed a different definition of MMR, and conclude that there is a common trend in the content of these definitions over time. They take the view that earlier texts on mixing methods stressed a “disentanglement of methods and philosophy,” while later texts locate the practice of mixing methods in “all phases of the research process” (Creswell and Plano Clark 2011 , p. 2). It would seem, then, that according to these authors the definitions of MMR have become more abstract, further away from the practicality of “merely” combining methods. Specifically, researchers now seem to speak of mixing higher order concepts: some speak of mixing methodologies, others refer to mixing “research approaches,” or combining “types of research,” or engage in “multiple ways of seeing the social world” (Creswell and Plano Clark 2011 ).

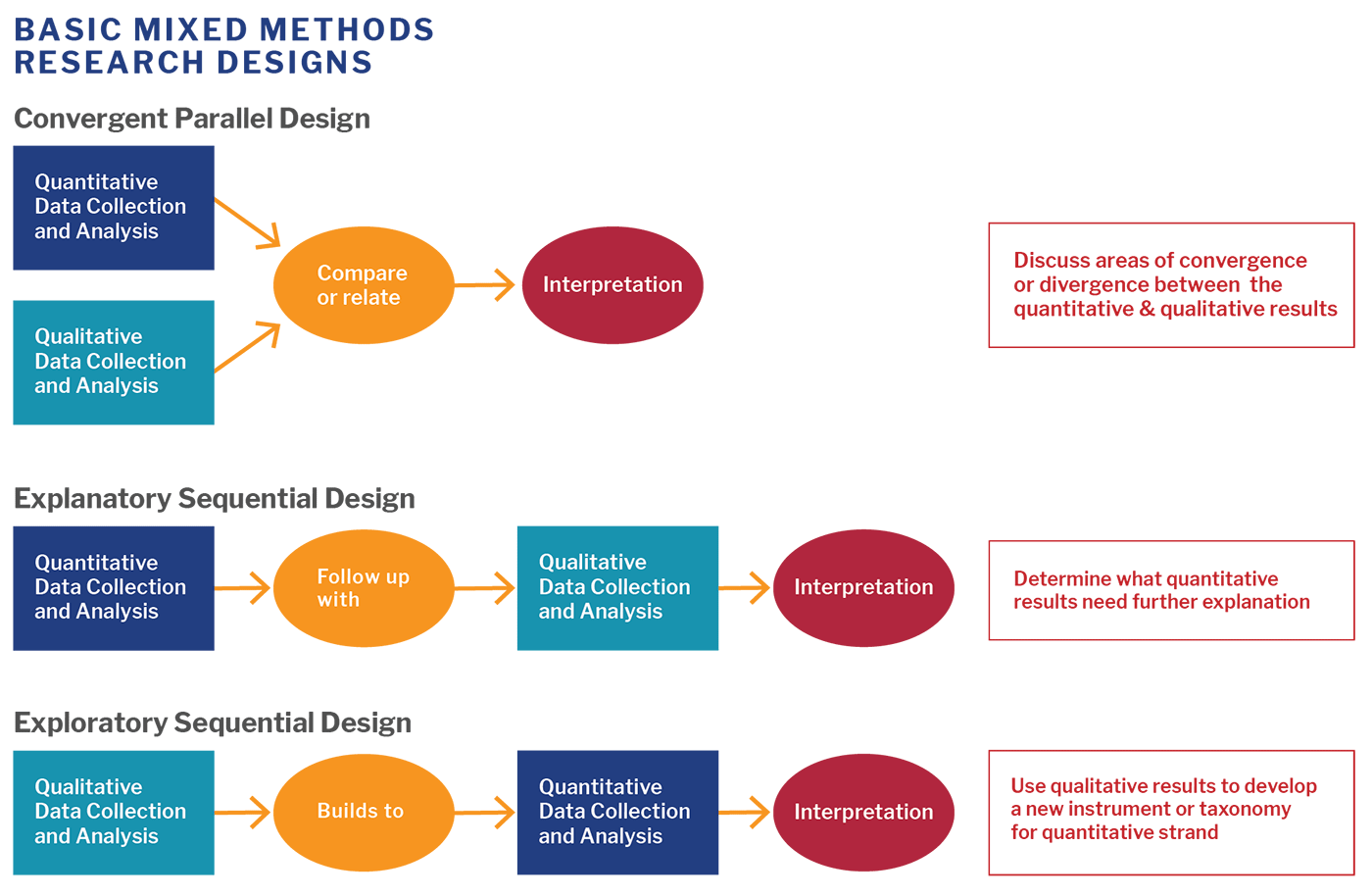

This shift is in line with the direction in which MMR has developed and that emphasises practical ‘manuals’ and schemas for conducting research. A relatively large portion of the MMR literature is devoted to classifications of mixed methods designs. These classifications provide the basis for typologies that, in turn, provide guidelines to conduct MMR in a concrete research project. Tashakkori and Teddlie ( 2003 ) view these typologies as important elements of the organizational structure and legitimacy of the field. In addition, Leech and Onwuegbuzie ( 2009 ) see typologies as helpful guides for researchers and of pedagogical value (Leech and Onwuegbuzie 2009 , p. 272). Proposals for typologies can be found in textbooks, articles, and contributions to the handbook(s). For example, Creswell et al. ( 2003 , pp. 169-170) reviewed a number of studies and identified 8 different ways to classify MMR studies. This list was updated and extended by Creswell and Plano Clark ( 2011 , pp. 56-59) to 15 typologies. Leech and Onwuegbuzie ( 2009 ) identified 35 different research designs in the contributions to Teddlie and Tashakkori (2003) alone, and proposed their own three-dimensional typology that resulted in 8 different types of mixed methods studies. As another example of the ubiquity of these typologies, Nastasi et al. ( 2010 ) classified a large number of existing typologies in MMR into 7”meta-typologies” that each emphasize different aspects of the research process as important markers for MMR. According to the authors, these typologies have the same function in MMR as the more familiar names of “qualitative” or “quantitative” methods (e.g., “content analysis” or “structural equation modelling”) have: to signal readers of research what is going on, what procedures have been followed, how to interpret results, etc. (see also Creswell et al. 2003 , pp. 162–163). The criteria underlying these typologies mainly have to do with the degree of mixing (e.g., are methods mixed throughout the research project or not?), the timing (e.g., sequential or concurrent mixing of methods) and the emphasis (e.g., is one approach dominant, or do they have equal status?).

We find this strong drive to develop methodologies, definitions, and typologies of MMR as guides to valid mixed methods research problematic. What it amounts to in practice is a methodology that lays out the basic guidelines for doing MMR in a “proper way.” This entails the danger of straight-jacketing reflection about the use of methods, decoupling it from theoretical and empirical considerations, thus favouring the unreflexive use of a standard methodology. Researchers are asked to make a choice for a particular MMR design and adhere to the guidelines for a “proper” MMR study. Such methodological prescription diametrically opposes the initial critique of the mechanical and unreflexive use of methods. The insight offered by Bourdieu’s notion of reflexivity is, on the contrary, that the actual research practice is fundamentally open in terms of being guided by a logic of practice that cannot be captured by a preconceived and all-encompassing logic independent of that practice. Reflexivity in this view cannot be achieved by hiding behind the construct of a standardized methodology—of whatever signature—it can only be achieved by objectifying the process of objectification that goes on within the context of the field in which the researcher is embedded. This reflexivity, then, requires an analysis of the position of the researcher as a critical component of the research process, both as the embodiment of past choices that have consequences for the strategic position in the scientific field, and as predispositions regarding the choice for the subject and content of a research project. By adding the insight of STS researchers that the point of deconstructing science and technology is not so much to offer a new best way of doing science or technology, but to provide insights into the critical moments in research (for a take on such a debate, see, for example, Edge 1995 , pp. 16–20), this calls for a sociology of science that takes methods much more seriously as objects of study. Such a programme should be based on studying the process of codification and standardization of methods in their historical context of production, circulation, and use. It would provide a basis for a sociological understanding of methods that can illuminate the critical moments in research alluded to above, enabling a systematic reflection on the process of objectification. This, in turn, allows a more sophisticated validation of using—and combining—methods than relying on prescribed methodologies.

The role of epistemology

The second theme discussed in a large number of contributions is the role epistemology plays in MMR. In a sense, epistemology provides the lifeblood for MMR in that methods in MMR are mainly seen in epistemological terms. This interpretation of methods is at the core of the knowledge claim of MMR practitioners, i.e., that the mixing of methods means mixing broad, different ways of knowing, which leads to better knowledge of the research object. It is also part of the identity that MMR consciously assumes, and that serves to set it apart from previous, more practical attempts to combine methods. This can be seen in the historical overview that Creswell and Plano Clark ( 2011 ) presented and that was discussed above. This reading, in which combining methods has evolved from the rather unproblematic level (one could alternatively say “naïve” or “unaware”) of instrumental use of various tools and techniques into an act that requires deeper thinking on a methodological and epistemological level, provides the legitimacy of MMR.

At the core of the MMR approach we thus find that methods are seen as unproblematic representations of different epistemologies. But this leads to a paradox, since the epistemological frameworks need to be held flexible enough to allow researchers to integrate elements of each of them (in the shape of methods) into one MMR design. As a consequence, the issue becomes the following: methods need to be disengaged from too strict an interpretation of the epistemological context in which they were developed in order for them to be “mixable,”’, but, at the same time, they must keep the epistemology attributed to them firmly intact.

In the MMR discourse two epistemological positions are identified that matter most: a positivist approach that gives rise to quantitative methods and a constructivist approach that is home to qualitative methods. For MMR to be a feasible endeavour, the differences between both forms of research must be defined as reconcilable. This position necessitates an engagement with those who hold that the quantitative/qualitative dichotomy is unbridgeable. Within MMR an interesting way of doing so has emerged. In the first issue of the Journal of Mixed Methods Research, Morgan ( 2007 ) frames the debate about research methodology in the social sciences in terms of Kuhnian paradigms, and he argues that the pioneers of the emancipation of qualitative research methods used a particular interpretation of the paradigm-concept to state their case against the then dominant paradigm in the social sciences. According to Morgan, they interpreted a paradigm mainly in metaphysical terms, stressing the connections among the trinity of ontology, epistemology, and methodology as used in the philosophy of knowledge (Morgan 2007 , p. 57). This allowed these scholars to depict the line between research traditions in stark, contrasting terms, using Kuhn’s idea of “incommensurability” in the sense of its “early Kuhn” interpretation. This strategy fixed the contrast between the proposed alternative approach (a “constructivist paradigm”), and the traditional approach (constructed as “the positivist paradigm”) to research as a whole, and offered the alternative approach as a valid option rooted in the philosophy of knowledge. Morgan focuses especially on the work of Egon Guba and Yvonne Lincoln who developed what they initially termed a “naturalistic paradigm” as an alternative to their perception of positivism in the social sciences (e.g., Guba and Lincoln 1985 ). Footnote 9 MMR requires a more flexible or “a-paradigmatic stance” towards research, which would entail that “in real-world practice, methods can be separated from the epistemology out of which they emerged” (Patton 2002 , quoted in Tashakkori and Teddlie 2010b , p. 14).

This proposal of an ‘interpretative flexibility’ (Bijker 1987 , 1997 ) regarding paradigms is an interesting proposition. But it immediately raises the question: why stop there? Why not take a deeper look into the epistemological technology of methods themselves, to let the muted components speak up in order to look for alternative “mixing interfaces” that could potentially provide equally valid benefits in terms of the understanding of a research object? The answer, of course, was already seen above. It is that the MMR approach requires situating methods epistemologically in order to keep them intact as unproblematic mediators of specific epistemologies and, thus, make the methodological prescriptions work. There are several problems with this. First, seeing methods solely through an epistemological lens is problematic, but it would be less consequential if it were applied to multiple elements of methods separately. This would at least allow a look under the hood of a method, and new ways of mixing methods could be opened up that go beyond the crude “qualitative” versus “quantitative” dichotomy. Second, there is also the issue of the ontological dimension of methods that is disregarded in an exclusively epistemological framing of methods (e.g., Law 2004 ). Taking this ontological dimension seriously has at least two important facets. First, it draws attention to the ontological assumptions that are woven into methods in their respective fields of production and that are imported into fields of users. Second, it entails the ontological consequences of practising methods: using, applying, and referring to methods and the realities this produces. This latter facet brings the world-making and boundary-drawing capacities of methods to the fore. Both facets are ignored in MMR. We say more about the first facet in the next section. With regard to the second facet, a crucial element concerns the data that are generated, collected, and analysed in a research project. But rather than problematizing the link between the performativity of methods and the data that are enacted within the frame of a method, here too MMR relies on a dichotomy: that between quantitative and qualitative data. Methods are primarily viewed as ways of gathering data or as analytic techniques dealing with a specific kind of data. Methods and data are conceptualised intertwiningly: methods too are seen as either quantitative or qualitative (often written as QUANT and QUAL in the literature), and perform the role of linking epistemology and data. In the final analysis, the MMR approach is based on the epistemological legitimization of the dichotomy between qualitative and quantitative data in order to define and combine methods: data obtain epistemological currency through the supposed in-severable link to certain methods, and methods are reduced to the role of acting as neutral mediators between them.

In this way, methods are effectively reduced to, on the one hand, placeholders for epistemological paradigms and, on the other hand, mediators between one kind of data and the appropriate epistemology. To put it bluntly, the name “mixed methods research” is actually a misnomer, because what is mixed are paradigms or “approaches,” not methods. Thus, the act of mixing methods à la MMR has the paradoxical effect of encouraging a crude black box approach to methods. This is a third problematic characteristic of MMR, because it hinders a detailed study of methods that can lead to a much richer perspective on mixing methods.

Black boxed methods and how to open them

The third problem that we identified with the MMR approach, then, is that with the impetus to standardize the MMR methodology by fixing methods epistemologically, complemented by a dichotomous view of data, they are, in the words of philosopher Bruno Latour, “blackboxed.” This is a peculiar result of the prescription for mixing methods as proposed by MMR that thus not only denies practice and the ontological dimensions of methods and data, but also casts methods in the role of unyielding black boxes. Footnote 10 With this in mind, it will come as no surprise that most foundational contributions to the MMR literature do not explicitly define what a method is, nor that they do not provide an elaborative historical account of individual methods. The particular framing of methods in MMR results in a blind spot for the historical and social context of the production and circulation of methods as intellectual products. Instead it chooses to reify the boundaries that are drawn between “qualitative” and “quantitative” methods and reproduce them in the methodology it proposes. Footnote 11 This is an example of “circulation without context” (Bourdieu 2002 , p. 4): classifications that are constructed in the field of use or reception without taking the constellation within the field of production seriously.

Of course, this does not mean that the reality of the differences between quantitative and qualitative research must be denied. These labels are sticky and symbolically laden. They have come, in many ways, to represent “two cultures” (Goertz and Mahony 2012 ) of research, institutionalised in academia, and the effects of nominally “belonging” to (or being assigned to) one particular category have very real consequences in terms of, for instance, access to research grants and specific journals. However, if the goal of an approach such as MMR is to open up new pathways in social science research, (and why should that not be the case?) it is hard to see how that is accomplished by defining the act of combining methods solely in terms of reified differences between research using qualitative and quantitative data. In our view, methods are far richer and more interesting constructs than that, and a practice of combining methods in research should reflect that. Footnote 12

Addressing these problems entices a reflection on methods and using (multiple) methods that is missing in the MMR perspective. A fruitful way to open up the black boxes and take into account the epistemological and ontological facets of methods is to make them, and their use, the object of sociological-historical investigation. Methods are constituted through particular practices. In Bourdieusian terms, they are objectifications of the subjectively understood practices of scientists “in other fields.” Rather than basing a practice of combining methods on an uncritical acceptance of the historically grown classification of types of social research (and using these as the building stones of a methodology of mixing methods), we propose the development of a multifaceted approach that is based on a study of the different socio-historical contexts and practices in which methods developed and circulated.

A sociological understanding of methods based on these premises provides the tools to break with the dichotomously designed interface for combining methods in MMR. Instead, focusing on the historical and social contexts of production and use can reveal the traces that these contexts leave, both in the internal structure of methods, how they are perceived, how they are put into practice, and how this practice informs the ontological effects of methods. Seeing methods as complex technologies, with a history that entails the struggles among the different agents involved in their production, and use opens the way to identify multiple interfaces for combining them: the one-sided boxes become polyhedra. The critical study of methods as “objects of objectification” also entices analyses of the way in which methods intervene between subject (researcher) and object and the way in which different methods are employed in practice to draw this boundary differently. The reflexive position generated by such a systematic juxtaposition of methods is a fruitful basis to come to a richer perspective on combining methods.

We critically reviewed the emerging practice of combining methods under the label of MMR. MMR challenges the mono-method approaches that are still dominant in the social sciences, and this is both refreshing and important. Combining methods should indeed be taken much more seriously in the social sciences.

However, the direction that the practice of combining methods is taking under the MMR approach seems problematic to us. We identified three main concerns. First, MMR scholars seem to be committed to designing a standardized methodological framework for combining methods. This is unfortunate, since it amounts to enforcing an unnecessary codification of aspects of research practices that should not be formally standardized. Second, MMR constructs methods as unproblematic representations of an epistemology. Although methods must be separable from their native epistemology for MMR to work, at the same time they have to be nested within a qualitative or a quantitative research approach, which are characterized by the data they use. By this logic, combining quantitative methods with other quantitative methods, or qualitative methods with other qualitative methods, cannot offer the same benefits: they originate from the same way of viewing and knowing the world, so it would have the same effect as blending two gradations of the same colour paint. The importance attached to the epistemological grounding of methods and data in MMR also disregards the ontological aspects of methods. In this article, we are arguing that this one-sided perspective is problematic. Seeing combining methods as equivalent to combining epistemologies that are somehow pure and internally homogeneous because they can be placed in a qualitative or quantitative framework essentially amounts to reifying these categories.

It also leads to the third problem: the black boxing of methods as neutral mediators between these epistemologies and data. This not only constitutes a problem for trying to understand methods as intellectual products, but also for regarding the practice of combining methods, because it ignores the social-historical context of the development of individual methods and hinders a sociologically grounded notion of combining methods.

We proceed from a different perspective on methods. In our view, methods are complex constructions. They are world-making technologies that encapsulate different assumptions on causality, rely on different conceptual relations and categorizations, allow for different degrees of emergence, and employ different theories of the data that they internalise as objects of analysis. Even more importantly, their current form as intellectual products cannot be separated from the historical context of their production, circulation, and use.

A fully developed exposition of such an approach will have to await further work. Footnote 13 So far, the sociological study of methods has not (yet) developed into a consistent research programme, but important elements can be derived from existing contributions such as MacKenzie ( 1981 ), Chapoulie ( 1984 ), Platt ( 1996 ), Freeman ( 2004 ), and Desrosières ( 2008a , b ). The work on the “social life of methods” (e.g., Savage 2013 ) also contains important leads for the development of a systematic sociological approach to method production and circulation. Based on the discussion in this article and the contributions listed above, some tantalizing questions can be formulated. How are methods and their elements objectified? How are epistemology and ontology defined in different fields and how do those definitions feed into methods? How do they circulate and how are they translated and used in different contexts? What are the main controversies in fields of users and how are these related to the field of production? What are the homologies between these fields?

Setting out to answer these questions opens up the possibility of exploring other interesting combinations of methods that emerge from the combination of different practices, situated in different historical and epistemological contexts, and with their unique set of interpretations regarding their constituent elements. One of these must surely be the data-theoretical elements that different methods incorporate. The problematization of data has become all the more pressing now that the debate about the consequences of “big data” for social scientific practices has become prominent (Savage and Burrows 2007 ; Levallois et al. 2013 ; Burrows and Savage 2014 ). Whereas MMR emphasizes the dichotomy between qualitative and quantitative data, a historical analysis of the production and use of methods can explore the more subtle, different interpretations and enactments of the “same” data. These differences inform method construction, controversies surrounding methods and, hence, opportunities for combining methods. These could then be constructed based on alternative conceptualisations of data. Again, while in some contexts it might be enlightening to rely on the distinction between data as qualitative or quantitative, and to combine methods based on this categorization, it is an exciting possibility that in other research contexts other conceptualisations of data might be of more value to enhance a specific (contextual) form of knowledge.

Change history

06 may 2019.

Unfortunately, figure 2 was incorrectly published.

The search term used was “mixed method*” in the “topic” search field of SSCI, A&HCI, and CPCI-SSH as contained in the Web of Science. A Google NGram search (not shown) confirmed this pattern. The results of a search for “mixed methods” and “mixed methods research” showed a very steep increase after 1994: in the first case, the normalized share in the total corpus increased by 855% from 1994 till 2008. Also, Creswell ( 2012 ) reports an almost hundred-fold increase in the number of theses and dissertations with mixed methods’ in the citation and abstract (from 26 in 1990–1994 to 2524 in 2005–2009).

Retrieved from https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/journal-of-mixed-methods-research/journal201775#aims-and-scope on 1/17/2019.

In terms of antecedents of mixed methods research, it is interesting to note that Bourdieu, whose sociology of science we draw on, was, from his earliest studies in Algeria onwards, a strong advocate of combining research methods. He made it into a central characteristic of his approach to social science in Bourdieu et al. ( 1991 [1968]). His approach, as we see below, was very different from the one now proposed under the banner of MMR. Significantly, there is no mention of Bourdieu’s take on combining methods in any of the sources we studied.

Morse’s example in particular warns us that restricting the analysis to the authors that have published in the JMMR runs the risk of missing some important contributors to the spread of MMR through the social sciences. On her website, Morse lists 11 publications (journal articles, book chapters, and books) that explicitly make reference to mixed methods (and a substantial number of other publications are about methodological aspects of research), so the fact that she has not (yet) published in the JMMR cannot, by itself, be taken as an indication of a lesser involvement with the practice of combining methods. See the website of Janice Morse at https://faculty.utah.edu/u0556920-Janice_Morse_RN,_PhD,_FAAN/hm/index.hml accessed 1/17/2019.

Bourdieu ( 1999 , p. 26) mentions that one has to be a scientific capitalist to be able to start a scientific revolution. But here he refers explicitly to the autonomy of the scientific field, making it virtually impossible for amateurs to stand up against the historically accumulated capital in the field and incite a revolution.

The themes summarize the key issues through which MMR as a group comes “into difference” (Bourdieu 1993 , p. 32). Of course, as in any (sub)field, the agents identified above often differ in their opinions on some of these key issues or disagree on the answer to the question if there should be a high degree of convergence of opinions at all. For instance, Bryman ( 2009 ) worried that MMR could become “a ghetto.” For him, the institutional landmarks of having a journal, conferences, and a handbook increase the risk of “not considering the whole range of possibilities.” He added: “I don’t regard it as a field, I kind of think of it as a way of thinking about how you go about research.” (Bryman, cited in Leech 2010 , p. 261). It is interesting to note that Bryman, like fellow sociologists Morgan and Denscombe, had published only one paper in the JMMR by the end of 2016 (Bryman passed away in June of 2017). Although these papers are among the most cited papers in the journal (see Table 1 ), this low number is consistent with the more eclectic approach that Bryman proposed.

Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, and Turner ( 2007 , p. 123).

Guba and Lincoln ( 1985 ) discuss the features of their version of a positivistic approach mainly in ontological and epistemological terms, but they are also careful to distinguish the opposition between naturalistic and positivist approaches from the difference between what they call the quantitative and the qualitative paradigms. Since they go on to state that, in principle, quantitative methods can be used within a naturalistic approach (although in practice, qualitative methods would be preferred by researchers embracing this paradigm), they seem to locate methods on a somewhat “lower,” i.e., less incommensurable level. However, in their later work (both together as well as with others or individually) and that of others in their wake, there seems to have been a shift towards a stricter interpretation of the qualitative/quantitative divide in metaphysical terms, enabling Teddlie and Tashakkori (2010b) to label this group “purists” (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2010b , p. 13).

See, for instance, Onwuegbuzie et al.’s ( 2011 ) classification of 58 qualitative data analysis techniques and 18 quantitative data analysis techniques.

This can also be seen in Morgan’s ( 2018 ) response to Sandelowski’s ( 2014 ) critique of the binary distinctions in MMR between qualitative and quantitative research approaches and methods. Morgan denounces the essentialist approach to categorizing qualitative and quantitative research in favor of a categorization based on “family resemblances,” in which he draws on Wittgenstein. However, this denies the fact that the essentialist way of categorizing is very common in the MMR corpus, particularly in textbooks and manuals (e.g., Plano Clark and Ivankova 2016 ). Moreover, and more importantly, he still does not extend this non-essentialist model of categorization to the level of methods, referring, for instance, to the different strengths of qualitative and quantitative methods in mixed methods studies (Morgan 2018 , p. 276).

While it goes beyond the scope of this article to delve into the history of the qualitative-quantitative divide in the social sciences, some broad observations can be made here. The history of method use in the social sciences can briefly be summarized as first, a rather fluid use of what can retrospectively be called different methods in large scale research projects—such as the Yankee City study of Lloyd Warner and his associates (see Platt 1996 , p. 102), the study on union democracy of Lipset et al. ( 1956 ), and the Marienthal study by Lazarsfeld and his associates (Jahoda et al. 1933 ); see Brewer and Hunter ( 2006 , p. xvi)—followed by an increasing emphasis on quantitative data and the objectification and standardization of methods. The rise of research using qualitative data can be understood as a reaction against this use and interpretation of method in the social sciences. However, out of the ensuing clash a new, still dominant classification of methods emerged, one that relies on the framing of methods as either “qualitative” or “quantitative.” Moreover, these labels have become synonymous with epistemological positions that are reproduced in MMR.

A proposal to come to such an approach can be found in Timans ( 2015 ).

Bijker, W. (1987). The social construction of bakelite: Toward a theory of invention. In W. Bijker, T. Hughes, T. Pinch, & D. Douglas (Eds.), The social construction of technological systems: New directions in the sociology and history of technology . Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

Google Scholar

Bijker, W. (1997). Of bicycles, bakelites, and bulbs: Toward a theory of sociotechnical change . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1975). La spécifité du champ scientifique et les conditions sociales du progrès de la raison. Sociologie et Sociétés, 7 (1), 91–118.

Article Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1988). Homo academicus . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production . Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1999). Les historiens et la sociologie de Pierre Bourdieu. Le Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire Moderne et Contemporaine/SHMC, 1999 (3&4), 4–27.

Bourdieu, P. (2002). Les conditions sociales de la circulation internationale des idées. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, 145 (5), 3–8.

Bourdieu, P. (2004). Science of science and reflexivity . Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Bourdieu, P. (2007). Sketch for a self-analysis . Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Bourdieu, P., Chamboredon, J., & Passeron, J. (1991). The craft of sociology: Epistemological preliminaries . Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter.

Book Google Scholar

Brewer, J., & Hunter, A. (2006). Multimethod research: A synthesis of styles . London, UK: Sage.

Bryman, A. (2009). Sage Methodspace: Alan Bryman on research methods. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bHzM9RlO6j0 . Accessed 3/7/2019.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Burrows, R., & Savage, M. (2014). After the crisis? Big data and the methodological challenges of empirical sociology. Big Data & Society, 1 (1), 1–6.

Campbell, D., & Fiske, D. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56 (2), 81–105.

Chapoulie, J. (1984). Everett C. Hughes et le développement du travail de terrain en sociologie. Revue Française de Sociologie, 25 (4), 582–608.

Collins, R. (1998). The sociology of philosophies: A global theory of intellectual change . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Creswell, J. (2008). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. (2011). Controversies in mixed methods research. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J., Plano Clark, V., Gutmann, M., & Hanson, W. (2003). Advanced mixed methods research designs. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denscombe, M. (2008). Communities of practice a research paradigm for the mixed methods approach. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2 (3), 270–283.

Desrosières, A. (2008a). Pour une sociologie historique de la quantification - L’Argument statistique I . Paris, France: Presses des Mines.

Desrosières, A. (2008b). Gouverner par les nombres - L’Argument statistique II . Paris, France: Presses des Mines.

Edge, D. (1995). Reinventing the wheel. In D. Edge, S. Jasanof, G. Markle, J. Petersen, & T. Pinch (Eds.), Handbook of science and technology studies . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fielding, N. (2012). Triangulation and mixed methods designs data integration with new research technologies. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6 (2), 124–136.

Fielding, N., & Cisneros-Puebla, C. (2009). CAQDAS-GIS convergence: Toward a new integrated mixed method research practice? Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 3 (4), 349–370.

Fleck, C., Heilbron, J., Karady, V., & Sapiro, G. (2016). Handbook of indicators of institutionalization of academic disciplines in SSH. Serendipities, Journal for the Sociology and History of the Social Sciences, 1 (1) Retrieved from http://serendipities.uni-graz.at/index.php/serendipities/issue/view/1 . Accessed 10/10/2018.

Freeman, L. (2004). The development of social network analysis: A study in the sociology of science . Vancouver, Canada: Empirical Press.

Gingras, Y., & Gemme, B. (2006). L’Emprise du champ scientifique sur le champ universitaire et ses effets. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, 164 , 51–60.

Goertz, G., & Mahony, J. (2012). A tale of two cultures: Qualitative and quantitative research in the social sciences . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Greene, J. (2008). Is mixed methods social inquiry a distinctive methodology? Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2 (1), 7–22.

Guba, E., & Lincoln, Y. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Heilbron, J., Bedecarré, M., & Timans, R. (2017). European journals in the social sciences and humanities. Serendipities, Journal for the Sociology and History of the Social Sciences, 2 (1), 33–49 Retrieved from http://serendipities.uni-graz.at/index.php/serendipities/issue/view/5 . Accessed 10/10/2018.

Hesse-Biber, S. (2010). Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Jahoda, M., Lazarsfeld, P., & Zeisel, H. (1933). Die Arbeitslosen von Marienthal. Psychologische Monographen, 5 .

Johnson, R., & Gray, R. (2010). A history of philosophical and theoretical issues for mixed methods research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Johnson, R., Onwuegbuzie, A., & Turner, L. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1 (2), 112–133.

Law, J. (2004). After method: Mess in social science research . London, UK: Routledge.

Leech, N. (2010). Interviews with the early developers of mixed methods research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Leech, N., & Onwuegbuzie, T. (2009). A typology of mixed methods research designs. Quality & Quantity, 43 (2), 265–275.

Levallois, C., Steinmetz, S., & Wouters, P. (2013). Sloppy data floods or precise social science methodologies? In P. Wouters, A. Beaulieu, A. Scharnhorst, & S. Wyatt (Eds.), Virtual knowledge . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lipset, S., Trow, M., & Coleman, J. (1956). Union democracy: The internal politics of the international typographical union . Glencoe, UK: Free Press.

MacKenzie, D. (1981). Statistics in Britain: 1865–1930: The social construction of scientific knowledge . Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Morgan, D. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1 (1), 48–76.

Morgan, D. (2018). Living with blurry boundaries: The values of distinguishing between qualitative and quantitative research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12 (3), 268–276.

Mullins, N. (1973). Theories and theory groups in contemporary American sociology . New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Nagy Hesse-Biber, S., & Leavy, P. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of emergent methods . New York, NY and London, UK: Guilford Press.

Nastasi, B., Hitchcock, J., & Brown, L. (2010). An inclusive framework for conceptualizing mixed method design typologies. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Onwuegbuzie, A., Leech, N., & Collins, K. (2011). Toward a new era for conducting mixed analyses: The role of quantitative dominant and qualitative dominant crossover mixed analyses. In M. Williams & P. Vogt (Eds.), Handbook of innovation in social research methods . London, UK: Sage.

Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Plano Clark, V., & Creswell, J. (Eds.). (2007). The mixed methods reader . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Plano Clark, V., & Ivankova, N. (2016). Mixed methods research: A guide to the field . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Platt, J. (1996). A history of sociological research methods in America: 1920–1960 . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Plowright, D. (2010). Using mixed methods – Frameworks for an integrated methodology . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sandelowski, M. (2014). Unmixing mixed methods research. Research in Nursing & Health, 37 (1), 3–8.

Sapiro, G., Brun, E., & Fordant, C. (2018). The rise of the social sciences and humanities in France: Iinstitutionalization, professionalization and autonomization. In C. Fleck, M. Duller, & V. Karady (Eds.), Shaping human science disciplines: Institutional developments in Europe and beyond . Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Savage, M. (2013). The ‘social life of methods’: A critical introduction. Theory, Culture and Society, 30 (4), 3–21.

Savage, M., & Burrows, R. (2007). The coming crisis of empirical sociology. Sociology, 41 (5), 885–899.

Steinmetz, G. (2016). Social fields, subfields and social spaces at the scale of empires: Explaining the colonial state and colonial sociology. The Sociological Review, 64(2_suppl). 98-123.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2010a). Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2010b). Overview of contemporary issues in mixed methods. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chapter Google Scholar

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2010c). Epilogue. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2011). Mixed methods research: Contemporary issues in an emerging field. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2008). Foundations of mixed methods research – Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Timans, R. (2015). Studying the Dutch business elite: Relational concepts and methods . Doctoral dissertation, Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Wacquant, L. (2013). Bourdieu 1993: A case study in scientific consecration. Sociology, 47 (1), 15–29.

Download references

Acknowledgments

This research is part of the Interco-SSH project, funded by the European Union under the 7th Research Framework Programme (grant agreement no. 319974). Johan Heilbron would like to thank Louise and John Steffens, members of the Friends Founders’ Circle, who assisted his stay at the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study in 2017-18 during which he completed his part of the present article.

Author information