- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

presentation

Definition of presentation

- fairing [ British ]

- freebee

- largess

Examples of presentation in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'presentation.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1a

Phrases Containing presentation

- breech presentation

Dictionary Entries Near presentation

present arms

presentation copy

Cite this Entry

“Presentation.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/presentation. Accessed 30 Jun. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of presentation, medical definition, medical definition of presentation, more from merriam-webster on presentation.

Nglish: Translation of presentation for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of presentation for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about presentation

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), popular in wordplay, it's a scorcher words for the summer heat, flower etymologies for your spring garden, 12 star wars words, 'swash', 'praya', and 12 more beachy words, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, games & quizzes.

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

Michelangelo (1475—1564)

Lorenzo Monaco (c. 1370—1425)

Leonardo da Vinci (1452—1519)

Giorgio Vasari (1511—1574) Italian painter, architect, and biographer

See all related overviews in Oxford Reference »

More Like This

Show all results sharing this subject:

presentation drawing

Quick reference.

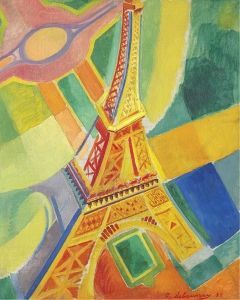

A term coined in the 20th century by the Hungarian art historian Johannes Wilde to describe certain drawings made by Michelangelo, for example those he gave as presents to various aristocratic young men. Presentation drawings were finished, non-utilitarian works of art, as opposed to preparatory drawings for a work in another medium. The earliest known presentation drawings dating from the Italian Renaissance are two drawings of the 1420s by Lorenzo Monaco.

From: presentation drawing in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms »

Subjects: Art & Architecture

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries.

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'presentation drawing' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 30 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Character limit 500 /500

What is Concept Art — Definition, Types & Iconic Examples

I n the vast, vibrant universe of art, there’s a special realm that often goes unnoticed by the casual observer. It’s called concept art, and it’s more than just pretty pictures on a canvas. It’s the backbone of some of your favorite movies, video games, and even theme parks. Concept art is the creative force that shapes these worlds long before they reach your screen or doorstep.

What is Concept Art Defined By?

First, let’s define concept art.

Diving into the heart of the matter, let's unravel the true definition and purpose of Concept Art in the field of creative industry.

CONCEPT ART DEFINITION

What is concept art.

Concept Art is essentially the visual representation of an idea before it is developed into a final product. It is used in various industries to define the look and feel of a product, movie, video game, or animation before it is produced.

Concept Art provides a tangible, visual blueprint, allowing teams to unify their vision and move forward in the creation process with a clear direction. It is the intersection of imagination and reality, the first step in bringing fantastical worlds and compelling characters to life.

What is Concept Art Used For?

- Vision Realization

- Team Alignment

- Project Direction

Who Creates Concept Art for Films?

The role of concept artists.

As the architects of imagination, concept artists play a crucial role in the creative industry. These artists are the pioneers, entrusted with the task of translating abstract ideas into concrete visuals.

Their canvases are blank slates, ready to be adorned with the blueprints of uncharted worlds, enigmatic characters, and unique aesthetics.

SO YOU WANT TO BE A CONCEPT ARTIST?

What concept artists do.

Concept artists begin with a brief, a kernel of an idea, or a narrative. They then utilize their artistic skills and creative vision to develop a series of images or designs that align with this initial concept. This process often involves sketching, digital painting, or creating 3D models. These visuals are then presented to directors, producers, or developers, serving as a guide for the final product.

Different Industries Where Concept Artists Are Needed

The need for concept artists spans a multitude of industries, each demanding its unique aesthetic and conceptual focus.

Video Games : In the gaming industry, concept artists design everything from characters, and environments, to the objects players interact with. Their work sets the visual tone of the game and influences the player's in-game experiences.

So You Wanna Make Games? • Episode 2: Concept Art

Film : Concept artists in film work closely with directors and production designers to bring their vision to life. Concept art in film is used to create visuals for settings, props, and sometimes even characters, contributing significantly to the movie's overall look and feel.

Animation : In animation , concept artists lay the groundwork for the entire animated piece. They dream up characters, storyboard scenes, and establish the animation's overall visual style, playing an integral role in shaping the animated universe.

Having explored what Concept Art is and the pivotal role concept artists play across various industries, let's now delve into the creative process behind Concept Art, detailing the journey from initial idea to final visual masterpiece.

How is Film Concept Art Created?

The creative process of concept art.

Concept Art is more than just a visual masterpiece; it's a creative journey. This process transforms a mere idea into a tangible piece of art. Here's a closer look at the stages involved.

Initial Ideas and Brainstorming

The seed of the creative process lies in the initial ideas and brainstorming. At this stage, concept artists often participate in collaborative sessions with directors , producers, or game designers to understand the vision of the project. Artists may discuss themes, styles, and overall aesthetics, taking inspiration from various sources. These sessions are about exploring possibilities, pushing boundaries, and discovering the potential of the initial concept.

Sketching and Creating Drafts

Once the initial ideas have been laid out, concept artists proceed to the sketching and drafting stage. This is where ideas begin to take a tangible form. Artists might start with rough sketches, experimenting with various designs, color schemes , and compositions.

Concept Art Process • Part 1: Sketching

Whether it's a character, a piece of environment, or a prop, each element undergoes several iterations. Digital tools like Photoshop or 3D modeling software may be used to refine these drafts.

Finalizing Designs and Presenting to Clients or Teams

The final stage involves refining and finalizing designs. At this point, the artist incorporates the feedback received during the drafting stage, fine-tuning the design to its minutest details. The final concept art is a polished, comprehensive visual representation of the idea, ready to guide the production team.

Once finalized, the concept artist presents their designs to the clients or teams. This presentation is crucial for aligning everyone with the project's visual direction. The finalized concept art now stands as a visual guidepost, directing every decision made in the project's subsequent production stages.

Related Posts

- Best Animation Software →

- What is Characterization? →

- VFX Compositing Techniques Explained →

Styles of Concept Art

Tools of the trade.

Concept Art creation is a complex process that requires a precise set of tools. From traditional materials to modern digital software, the choices can be overwhelming, but each contributes to the unique look and feel of the final design.

Here is a great video on tips to using these tools combined with consistency and curiosity to become a better concept artist.

How to Get Better at Concept Art. Really.

Traditional tools used in concept art.

Traditional tools have been the bedrock of the arts for centuries and continue to play a vital role in Concept Art today.

Sketchbooks : Sketchbooks are the starting point for most artists. They allow for spontaneous creativity, enabling artists to jot down ideas, sketch characters, or map out environments at any time.

Pencils and Pens : Pencils and pens offer versatility. From broad strokes to fine details, they provide a variety of line weights and styles.

Markers and Paints : Markers, watercolors, and acrylic paints add color to concept drawings. They help convey mood, atmosphere, and lighting within a design.

Digital Tools and Software Commonly Used by Modern Concept Artists

In the modern era, digital tools have become just as crucial as traditional ones. They provide a new level of flexibility, precision, and efficiency in Concept Art creation.

Graphics Tablets : A graphics tablet provides a natural, intuitive way for artists to draw digitally. It offers pressure sensitivity and precision, which can be essential for creating detailed work.

Photoshop : Adobe Photoshop is a staple in digital art. Its myriad of features like layers, brushes, and filters make it ideal for creating and modifying Concept Art.

3D Modeling Software : Software like Blender or Maya enables artists to create 3D models of characters or environments. This can be particularly helpful in presenting a more realistic view of a design.

Digital Painting Software : Platforms like Procreate or Corel Painter are designed specifically for digital painting, offering a range of brushes and effects that mimic traditional painting techniques.

Concept art is at the heart of visual storytelling, transforming ideas into captivating experiences. Whether it's video games, films, or animation, concept artists shape aesthetics and emotions, pushing creative boundaries. Let's appreciate the significant role of concept art in crafting immersive universes.

The Art Department in Film

Now that we have a firm understanding of concept art and its role in visual storytelling, let's delve deeper into the film industry's art department, the creative powerhouse that brings these concepts to life on the big screen.

Up Next: The Art Department in Film →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards..

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- Ethos, Pathos & Logos — Definition and Examples of Persuasive Advertising Techniques

- Ultimate AV Script Template to Write Better Ads [FREE AV Script Template]

- What is Dramatic Irony? Definition and Examples

- What is Situational Irony? Definition and Examples

- How to Write a Buzzworthy Explainer Video Script [Free Template]

- 0 Pinterest

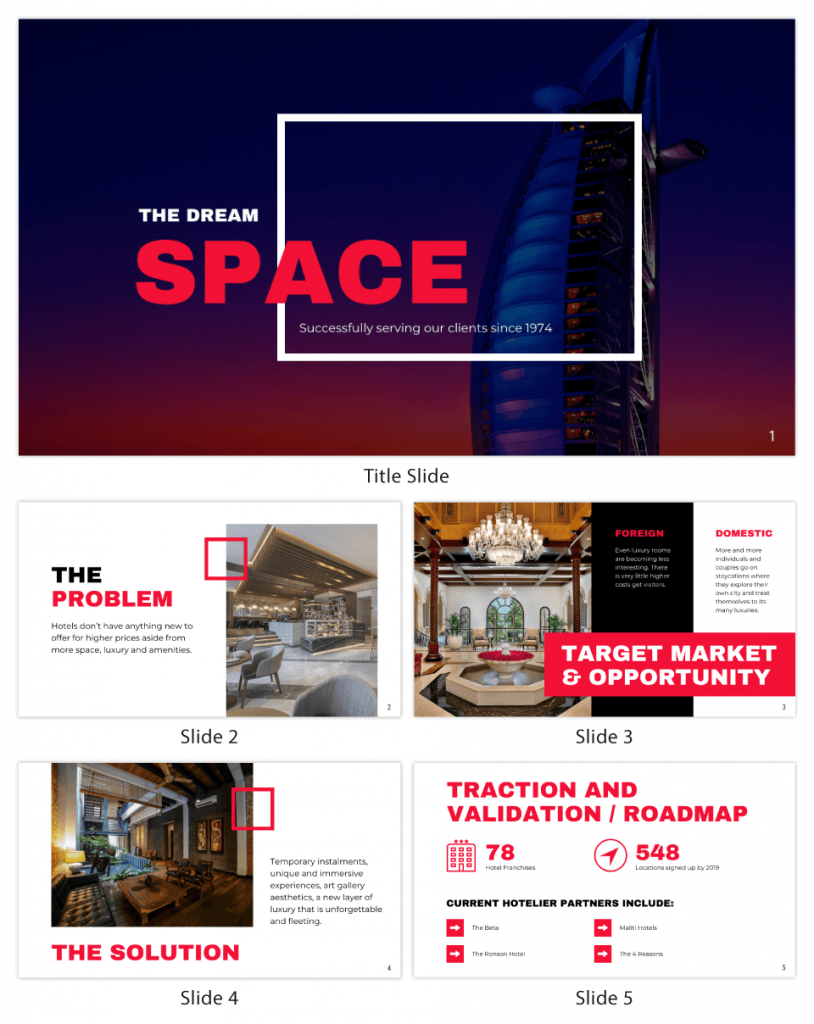

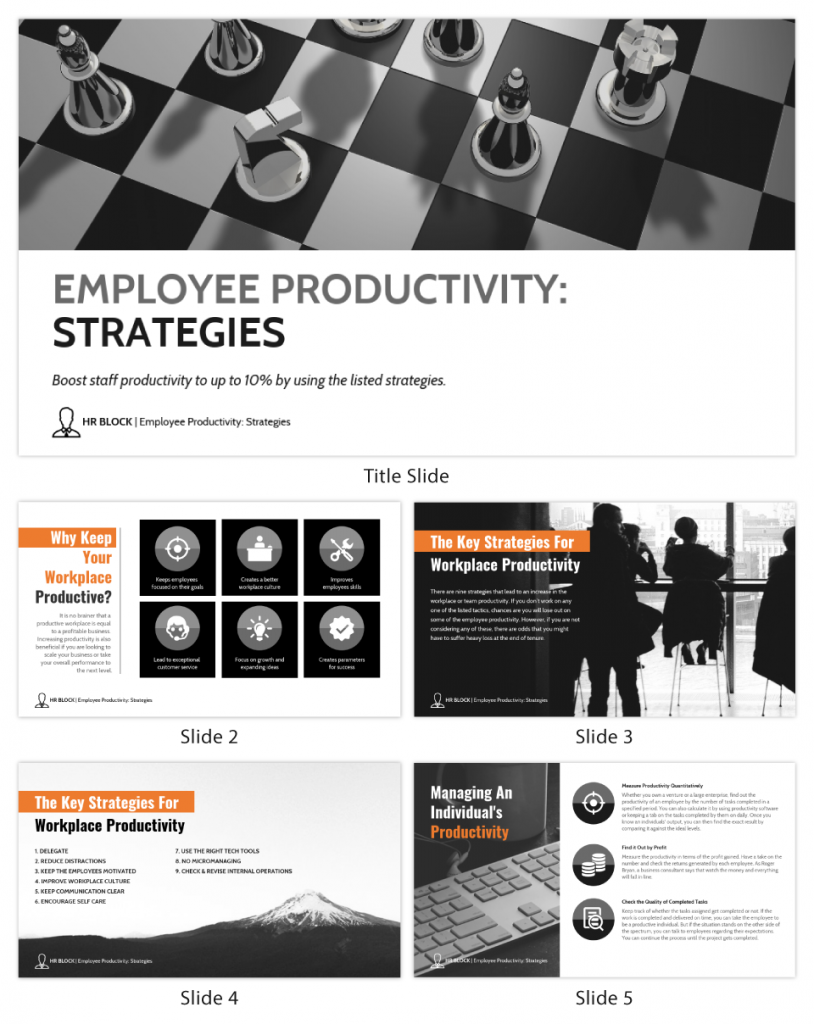

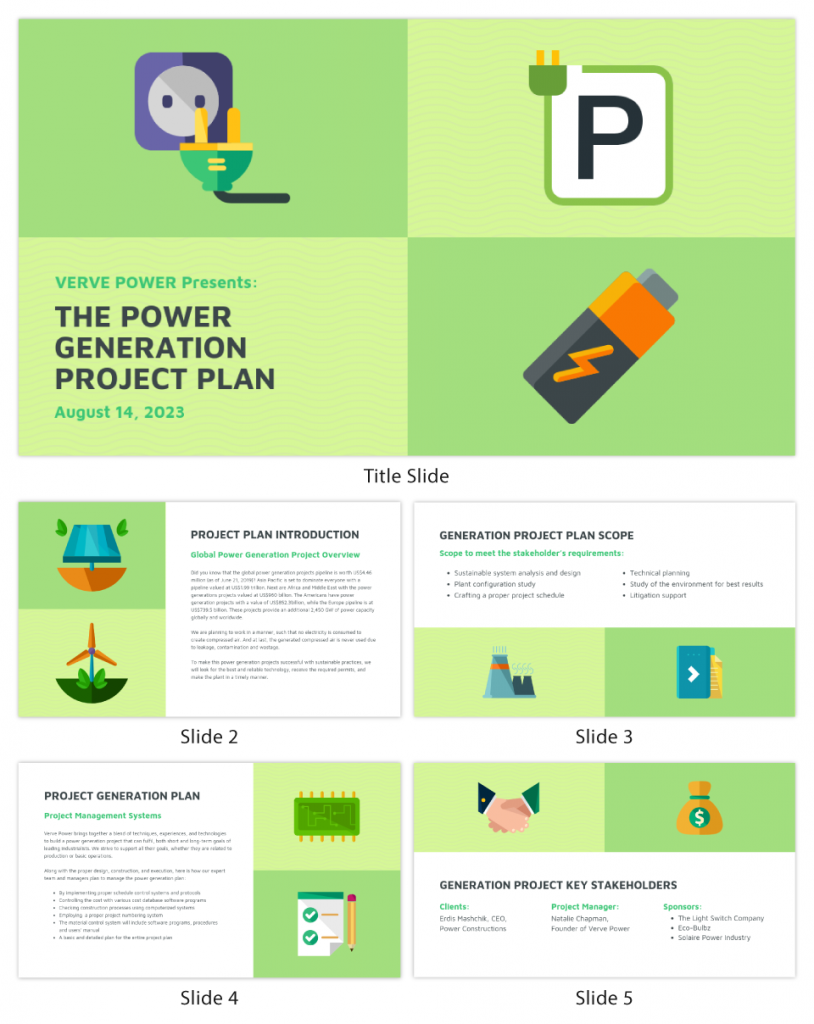

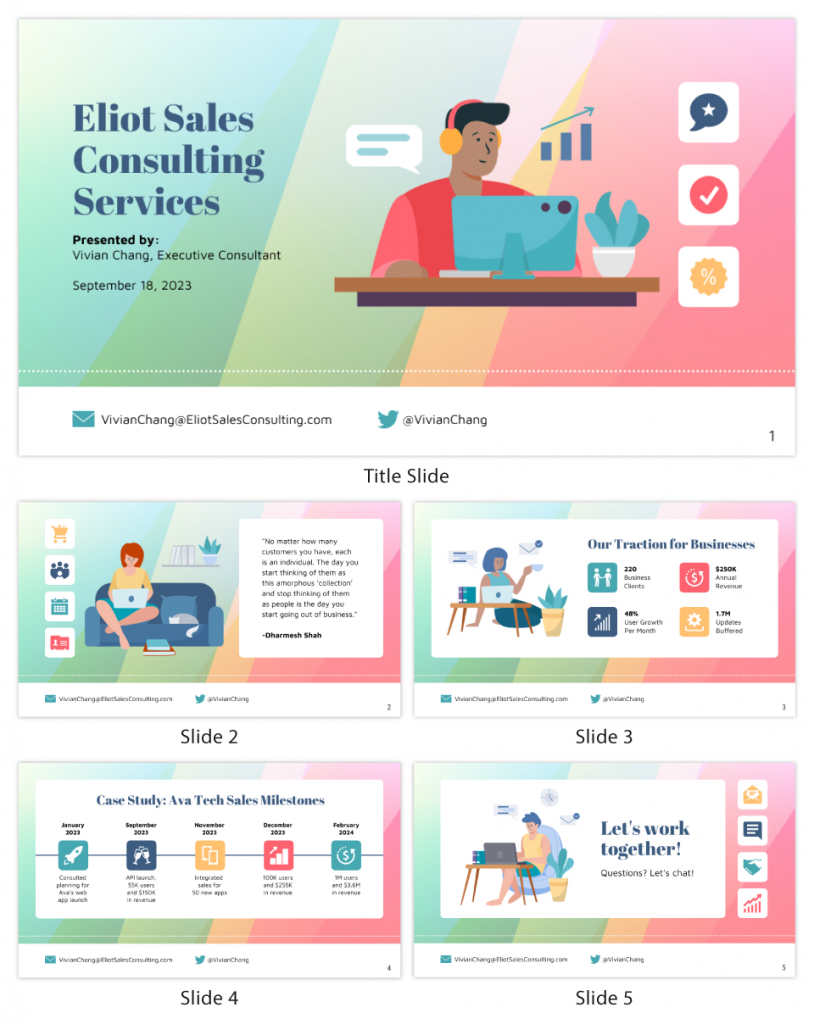

30 Presentation Terms & What They Mean

Delivering a captivating presentation is an art that requires more than just confidence and oratory skills. From the design of your slides to the way you carry yourself on stage, every little detail contributes to the overall effectiveness of your presentation. For those who wish to master this art, getting familiar with the associated terminology is a great place to start.

In this article, we’ll explore “30 Presentation Terms & What They Mean,” shedding light on the key terms and concepts in the world of presentations. Whether you’re a professional looking to refine your skills, a student aiming to ace your next presentation, or just someone curious about the subject, this guide is sure to provide you with valuable insights.

Dive in as we explore everything from slide decks and speaker notes to body language and Q&A sessions.

Each term is elaborated in depth, giving you a comprehensive understanding of their meanings and applications. This knowledge will not only make you more comfortable with presentations but will also empower you to deliver them more effectively.

2 Million+ PowerPoint Templates, Themes, Graphics + More

Download thousands of PowerPoint templates, and many other design elements, with a monthly Envato Elements membership. It starts at $16 per month, and gives you unlimited access to a growing library of over 2,000,000 presentation templates, fonts, photos, graphics, and more.

Business PPT Templates

Corporate & pro.

Animated PPT Templates

Fully animated.

BeMind Minimal Template

Ciri Template

Pitch PowerPoint

Explore PowerPoint Templates

Table of Contents

- Speaker Notes

- White Space

- Aspect Ratio

- Grid System

- Master Slide

- Infographic

- Data Visualization

- Call-to-Action (CTA)

- Color Palette

- Negative Space

- Storyboarding

- Bullet Points

- Eye Contact

- Body Language

- Q&A Session

1. Slide Deck

A slide deck, in its most basic sense, is a collection of slides that are presented in sequence to support a speech or presentation. The slides typically contain key points, graphics, and other visual aids that make the presentation more engaging and easier to understand.

Beyond merely displaying information, a well-crafted slide deck can tell a story, create an emotional connection, or illustrate complex concepts in a digestible way. Its design elements, including the choice of colors, fonts, and images, play a significant role in how the presentation is received by the audience.

2. Speaker Notes

Speaker notes are a feature in presentation software that allows presenters to add notes or cues to their slides. These notes are only visible to the presenter during the presentation. They can include additional information, reminders, prompts, or even the full script of the speech.

While the audience sees the slide deck, the speaker can use these notes as a guide to ensure they cover all necessary points without memorizing the entire speech. It’s essential to use speaker notes strategically – they should aid the presentation, not become a script that hinders natural delivery.

A template is a pre-designed layout for a slide deck. It typically includes a set design, color scheme, typefaces, and placeholders for content like text, images, and graphs. Templates can significantly reduce the time and effort required to create a professional-looking presentation.

While templates can be incredibly helpful, it’s important to choose one that aligns with the theme, purpose, and audience of the presentation. Customizing the template to match your brand or topic can further enhance its effectiveness.

4. Transition

In the realm of presentations, a transition refers to the visual effect that occurs when you move from one slide to the next. Simple transitions include fade-ins and fade-outs, while more complex ones might involve 3D effects, wipes, or spins.

Transitions can add a touch of professionalism and dynamism to a presentation when used correctly. However, overuse or choosing flashy transitions can be distracting and detract from the content. The key is to use transitions that complement the presentation’s tone and pace without overshadowing the message.

5. Animation

Animation is the process of making objects or text in your slide deck appear to move. This can involve anything from making bullet points appear one by one, to having graphics fly in or out, to creating a simulation of a complex process. Animation can add interest, emphasize points, and guide the audience’s attention throughout the presentation.

While animations can make a presentation more engaging, they must be used judiciously. Excessive or overly complex animations can distract the audience, complicate the message, and look unprofessional. As with transitions, animations should support the content, not detract from it.

6. Multimedia

Multimedia refers to the combination of different types of media — such as text, images, audio, video, and animation — within a single presentation. Incorporating multimedia elements can make a presentation more engaging, cater to different learning styles, and aid in explaining complex ideas.

However, it’s important to ensure that multimedia elements are relevant, high-quality, and appropriately scaled for the presentation. Additionally, depending on the presentation venue, technical considerations such as file sizes, internet speed, and audio quality need to be taken into account when using multimedia.

7. White Space

In the context of presentation design, white space (or negative space) refers to the unmarked portions of a slide, which are free of text, images, or other visual elements. Despite its name, white space doesn’t necessarily have to be white — it’s any area of a slide not filled with content.

White space can give a slide a clean, balanced look and can help draw attention to the most important elements. It can also reduce cognitive load, making it easier for the audience to process information. Good use of white space is often a key difference between professional and amateur designs.

8. Aspect Ratio

Aspect ratio is the proportional relationship between a slide’s width and height. It’s typically expressed as two numbers separated by a colon, such as 4:3 or 16:9. The first number represents the width, and the second represents the height.

The choice of aspect ratio can affect how content fits on the screen and how the presentation appears on different displays. For instance, a 16:9 aspect ratio is often used for widescreen displays, while a 4:3 ratio may be more suitable for traditional computer monitors and projectors.

9. Grid System

The grid system is a framework used to align and layout design elements in a slide. It’s comprised of horizontal and vertical lines that divide the slide into equal sections or grids.

The grid system aids in creating visual harmony, balance, and consistency across slides. It can guide the placement of text, images, and other elements, ensuring that they’re evenly spaced and aligned. It’s an important tool for maintaining a professional and organized appearance in a presentation.

10. Readability

Readability refers to how easy it is for an audience to read and understand the text on your slides. It involves factors such as font size, typeface, line length, spacing, and contrast with the background.

Ensuring good readability is crucial in presentations. If your audience can’t easily read and understand your text, they’ll be more likely to disengage. Large fonts, simple language, high-contrast color schemes, and ample white space can enhance readability.

11. Infographic

An infographic is a visual representation of information, data, or knowledge. They’re used in presentations to communicate complex data in a clear, concise, and engaging way. Infographics can include charts, graphs, icons, pictures, and text.

While infographics can effectively communicate complex ideas, they must be designed carefully. Too much information, confusing visuals, or a lack of a clear hierarchy can make an infographic difficult to understand. It’s important to keep the design simple and focus on the key message.

To embed in a presentation context means to incorporate external content, such as a video, a document, or a website, directly into a slide. When an object is embedded, it becomes part of the presentation file and can be viewed or played without leaving the presentation.

Embedding can be a useful tool to incorporate interactive or supplementary content into a presentation. However, it’s important to remember that it can increase the file size of the presentation and may require an internet connection or specific software to function correctly.

13. Palette

A palette, in terms of presentations, refers to the set of colors chosen to be used throughout the slide deck. This can include primary colors for backgrounds and text, as well as secondary colors for accents and highlights.

The right color palette can help convey the mood of a presentation, reinforce branding, and increase visual interest. It’s important to choose colors that work well together and provide enough contrast for readability. Tools like color wheel or color scheme generators can be helpful in choosing a harmonious palette.

14. Vector Graphics

Vector graphics are digital images created using mathematical formulas rather than pixels. This means they can be scaled up or down without losing quality, making them ideal for presentations that may be viewed on different screen sizes.

Vector graphics often have smaller file sizes than their pixel-based counterparts (raster graphics), which can help keep your presentation file manageable. Common types of vector graphics include logos, icons, and illustrations.

15. Mood Board

A mood board is a collection of images, text, colors, and other design elements that serve as visual inspiration for a presentation. It helps establish the aesthetic, mood, or theme of the presentation before the design process begins.

Creating a mood board can be a valuable step in the presentation design process. It can help you visualize how different elements will work together, communicate your design ideas to others, and maintain consistency across your slides.

16. Hierarchy

In design, hierarchy refers to the arrangement of elements in a way that implies importance. In presentations, visual hierarchy helps guide the viewer’s eye to the most important elements first.

Hierarchy can be created through the use of size, color, contrast, alignment, and whitespace. Effective use of hierarchy can make your slides easier to understand and keep your audience focused on the key points.

17. Stock Photos

Stock photos are professionally taken photographs that are bought and sold on a royalty-free basis. They can be used in presentations to add visual interest, convey emotions, or illustrate specific concepts.

While stock photos can enhance a presentation, it’s important to use them judiciously and choose images that align with your presentation’s tone and content. Overuse of generic or irrelevant stock photos can make a presentation feel impersonal or unprofessional.

18. Sans Serif

Sans serif refers to a category of typefaces that do not have small lines or strokes attached to the ends of larger strokes. Sans serif fonts are often used in presentations because they’re typically easier to read on screens than serif fonts, which have these small lines.

Some popular sans serif fonts for presentations include Helvetica, Arial, and Calibri. When choosing a font for your slides, readability should be a primary consideration.

19. Hyperlink

A hyperlink, or link, is a clickable element in a slide that directs the viewer to another slide in the deck, a different document, or a web page. Hyperlinks can be used in presentations to provide additional information or to navigate to specific slides.

While hyperlinks can be useful, they should be used sparingly and appropriately. Links that direct the viewer away from the presentation can be distracting and disrupt the flow of your talk.

PDF stands for Portable Document Format. It’s a file format that preserves the fonts, images, graphics, and layout of any source document, regardless of the computer or software used to create it. Presentations are often saved and shared as PDFs to ensure they look the same on any device.

While a PDF version of your presentation will maintain its appearance, it won’t include interactive elements like animations, transitions, and hyperlinks. Therefore, it’s best used for distributing slide handouts or when the presentation software used to create the deck isn’t available.

21. Raster Graphics

Raster graphics are digital images composed of individual pixels. These pixels, each a single point with its own color, come together to form the full image. Photographs are the most common type of raster graphics.

While raster graphics can provide detailed and vibrant images, they don’t scale well. Enlarging a raster image can lead to pixelation, where the individual pixels become visible and the image appears blurry. For this reason, raster images in presentations should be used at their original size or smaller.

22. Typeface

A typeface, often referred to as a font, is a set of characters with the same design. This includes letters, numbers, punctuation marks, and sometimes symbols. Typefaces can have different styles and weights, such as bold or italic.

The choice of typeface can significantly impact the readability and mood of a presentation. For example, serif typefaces can convey tradition and authority, while sans serif typefaces can appear modern and clean. The key is to choose a typeface that aligns with the purpose and audience of your presentation.

23. Visual Content

Visual content refers to the graphics, images, charts, infographics, animations, and other non-text elements in a presentation. These elements can help capture the audience’s attention, enhance understanding, and make the presentation more memorable.

While visual content can enhance a presentation, it’s important not to overload slides with too many visual elements, as this can confuse or overwhelm the audience. All visual content should be relevant, clear, and support the overall message of the presentation.

24. Call to Action

A call to action (CTA) in a presentation is a prompt that encourages the audience to take a specific action. This could be anything from visiting a website, signing up for a newsletter, participating in a discussion, or implementing a suggested strategy.

A strong CTA aligns with the goals of the presentation and is clear and compelling. It often comes at the end of the presentation, providing the audience with a next step or a way to apply what they’ve learned.

25. Thumbnails

In presentations, thumbnails are small versions of the slides that are used to navigate through the deck during the design process. They provide an overview of the presentation’s flow and can help identify inconsistencies in design.

Thumbnails are typically displayed in the sidebar of presentation software. They allow you to easily move, delete, or duplicate slides, and can provide a visual check for overall consistency and flow.

26. Aspect Ratio

27. interactive elements.

Interactive elements are components in a presentation that the audience can interact with. These could include hyperlinks, embedded quizzes, interactive infographics, or multimedia elements like audio and video.

Interactive elements can make a presentation more engaging and memorable. However, they require careful planning and should always be tested before the presentation to ensure they work as intended.

28. Placeholders

In the context of presentations, placeholders are boxes that are included in a slide layout to hold specific types of content, such as text, images, or charts. They guide the placement of content and can help ensure consistency across slides.

Placeholders can be especially useful when working with templates, as they provide a predefined layout to follow. However, they should be used flexibly – not every placeholder needs to be used, and additional elements can be added if necessary.

29. Master Slide

The master slide is the top slide in a hierarchy of slides that stores information about the theme and slide layouts of a presentation. Changes made to the master slide, such as modifying the background, fonts, or color scheme, are applied to all other slides in the presentation.

Master slides can help ensure consistency across a presentation and save time when making global changes. However, it’s important to note that individual slides can still be modified independently if necessary.

In presentations, a layout refers to the arrangement of elements on a slide. This includes the placement of text, images, shapes, and other elements, as well as the use of space and alignment.

Choosing the right layout can make your slides look organized and professional, guide the viewer’s eye, and enhance your message. Most presentation software offers a variety of pre-defined layouts, but these can usually be modified to better suit your content and design preferences.

What is Public Speaking? [Definition, Importance, Tips Etc!]

By: Author Shrot Katewa

![definition presentation art What is Public Speaking? [Definition, Importance, Tips Etc!]](https://artofpresentations.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Featured-Image-What-is-Public-Speaking.jpg)

If you are an ambitious professional, you will have to engage in some form of public speaking at some point in time in your life! The truth is, it is better to start with public speaking sooner rather than later! However, to better understand the subject, we must start with the definition of public speaking.

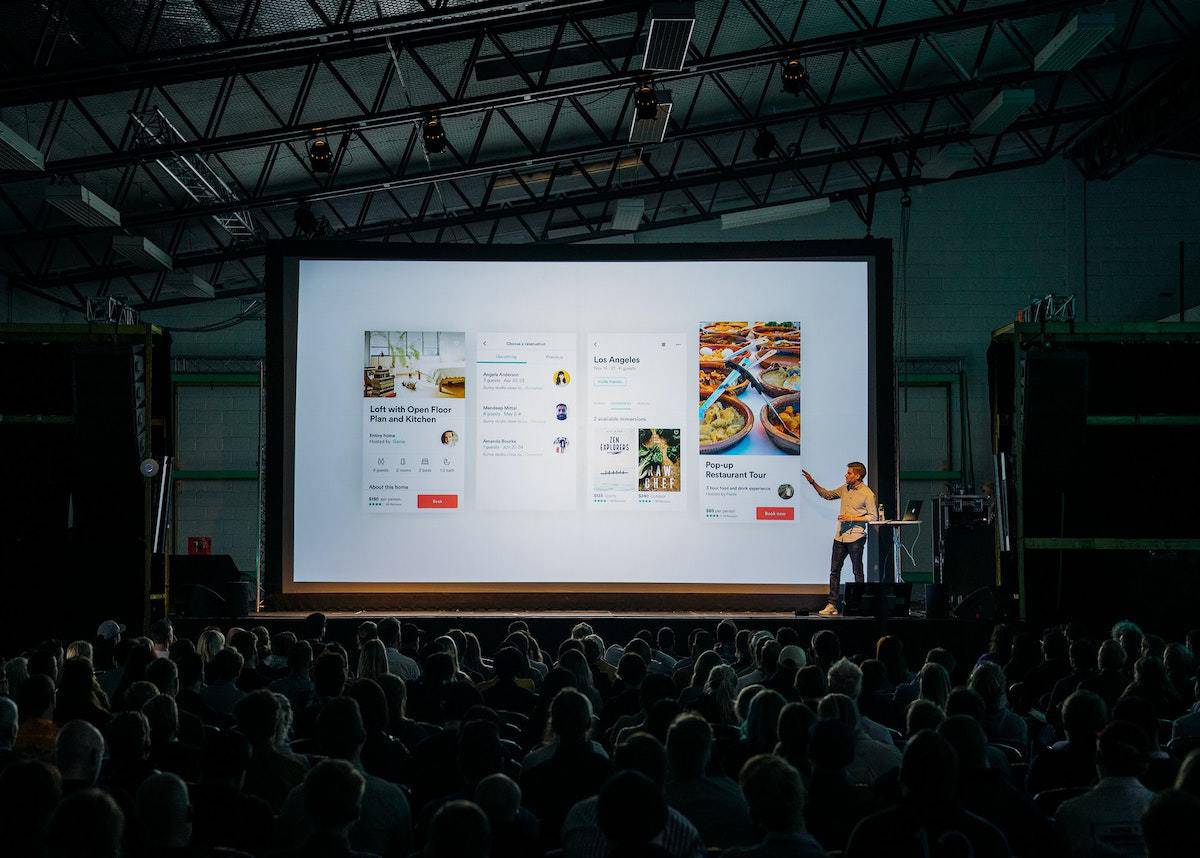

Public speaking is the art of conveying a message verbally to an audience of more than one individual. An average public speaker addresses a crowd of over 50 people, while some keynote presenters can expect an audience of a few thousand. With digital public speaking, this can be scaled infinitely.

In this post, you will learn everything you need to know to get started with public speaking, including why it is essential in the modern world, what skills make up the art form, and what you can expect when trying to turn your public speaking skills into a revenue-generating business or career.

Why is Public Speaking Important?

With over 77% of people having some degree of public speaking anxiety, according to Very Well Mind , and some positioning it as a greater fear than that of death itself, you might wonder why one needs to conquer such fear? What could be so essential about public speaking, after all?

Public speaking is critical because it allows you to connect with a group of people and persuade them to see things your way. It is the highest form of scaled influence and has existed as a change-making phenomenon in politics, society, and culture for over 2000 years.

Compare this to any social media platform, CEO-position duration, and professorship, and you’ll see that public speaking has been the most persistent form of influencing across time. In other words, it is transferrable and timeless.

You don’t have to worry about it going out of fashion because it has outlasted the fashion industry itself. Every other position of power relies on some degree of public speaking skills, even if an individual is not actively delivering keynotes.

What Are Public Speaking Skills?

At this point, you might be thinking, “wait, how is public speaking different from public speaking skills?” And I understand that because people often assume public speaking itself is a skill. Public Speaking is a performance art that relies on multiple skills to deliver a cohesive presentation of a singular skill.

Public speaking skills are the pillars that hold up an excellent presentation and include argument construction, audience engagement, stage presence management, timely delivery, and appropriate pacing. You can also improve your public speaking by using humor, rhetorical questions, and analogies.

Argument Construction

The way you position an argument matters more than the argument itself. That’s why in most rhetorical classes, you’re made to pick the “for” or “against” side at random, so you get good at making arguments regardless of the legitimacy of the position.

Usually, an argument follows the “problem,” “potential solution,” “reasons the said solution is the best” model though some constructions include countering general skepticism regarding a proposed solution.

Audience Engagement

This skill will help you lengthen your talk without having to script every second, but that’s not its primary goal. Audience engagement shouldn’t be used as fluff but as a means to retain your public’s attention, especially if a topic is particularly dry or the talk is too long.

Stage Presence Management

This is the aspect of audience engagement that has more to do with yourself. For instance, if you ask a question, you’re getting your audience’s attention by engaging with them.

However, if you strike a particular pose, make an exaggerated gesture, or simply carry yourself in a way that draws attention, you’re managing your stage presence (and increasing your audience’s involvement).

Timely Delivery

Timing is critical in public speaking because, given the fact that speechwriters exist, one can get away without constructing an argument or even writing the words to their talk. However, you cannot get away with bad delivery because if you don’t hold your audience’s attention, you’re only speaking to yourself.

Appropriate Pacing

Pacing your talk is essential because you cannot dump data on your audience without producing a cognitive overload. That’s why you must balance information with rhetoric and pace your presentation to bring your audience along with you.

Importance of Public Speaking Skills for Students

Whether you’re a student thinking of joining a public speaking club or a debating society, or a teacher looking to introduce your students to public speaking, knowing that it is an extracurricular art form that brings the greatest number of long-term benefits to students can be quite comforting.

The importance of public speaking for students lies in its cognitive benefits and social significance. Students who learn public speaking are more confident, can communicate their ideas better, and use speaking as a tool to polish their thoughts. This sets them up for success in public-facing roles.

More importantly, these benefits go hand-in-hand with long-term career success and social satisfaction because, unlike academic skills, public speaking expertise remains beneficial even after students say goodbye to their respective universities.

Benefits of Public Speaking

As mentioned above, the benefits of public speaking often outlast the student life and remain relevant to personal success. Whether you choose a corporate job or want to be a full-time speaker, you will be able to take the skills you build as a speaker and apply them to your life.

Benefits of public speaking include but aren’t limited to higher self-confidence, clarity of thought, personal satisfaction with one’s ability to communicate, a larger network, some degree of organic celebrity status, and higher levels of charisma.

Higher Self-Confidence

Self-confidence, as essential as it is, is a tricky subject because it relies entirely on one’s self-image. And if you don’t view yourself as confident, you aren’t confident.

The best way to improve your confidence is to observe yourself being confident : i.e., get into an activity that requires confidence. Given that oratory is one of the earliest art forms developed by humans, we can safely assume that it is also the one that has more inherent prestige involved.

Clarity of Thought

Public speaking forces one to learn new words and improves how one structures an argument. Since speaking also allows us to think and formulate thoughts into full-fledged concepts, a public speaker is better able to think with clarity.

Improved Ability to Communicate

Building on clarity of thought, one’s ability to communicate is enhanced once they have thought through their positions and arguments. Public speaking helps you communicate better in both the content and delivery of your thoughts.

Better Network

Humans are social animals, and networking is intrinsic to our success. They say that most of life’s significant events aren’t “what” events (as in “what happened?”) but “who” events (as in “who did you connect with?” or “who connected with you?”). Public speaking affords you the confidence to multiply the odds of better “who” events.

Natural Celebrity

We admire those who can do what we can’t. And since public speaking is such a valuable artform regarding which over 77% of people have trouble, it is pretty straightforward to conclude that the one who can pull this off will have higher social status among any group.

Increased Charisma

Finally, building on the previous perk of better social status, with Olivia Fox-Cabane’s definition of charisma as power and empathy, one can see how an organic celebrity status among one’s friend circle can also lead to improved charisma.

That said, not every public speaker is charismatic all the time. And to make sure you make the most of your ability to be charismatic as a public speaker, check out Fox Cabane’s book .

Types of Public Speaking

In the artform’s infancy, public speaking was public speaking. There was nothing else but an individual speaking to fellow city residents in a forum, trying to persuade them to get behind a certain reform or rollback one. Now public speaking has branched into various types.

Types of public speaking are divided across two dimensions: medium and mission .

Digital public speaking, on-stage speeches, and pre-recorded talks are three types differentiated by category. Keynote address, seminar, and debate are three forms differentiated by end-result.

- Division by medium allows us to see the type of speech by the method of delivery. You can conduct keynote, seminar, and debate in the digital type, but a live discussion is very likely off the table when you’re uploading a pre-recorded talk.

- Division by end-result allows us to see how public speaking can differ depending on the content format regardless of delivery. You can give a keynote address on stage or even have it pre-recorded. As long as you get the key point across, you’re doing your job.

Apple’s keynotes are consumed far more often online than they are in-person. So, being clear on the end result allows hybridization across different formats, especially with technology. Still, you should optimize the content and delivery of your talk for the medium you set as the primary one and let the others be optional.

In other words, if you’re conducting a seminar and interaction matters, do not sacrifice live interaction trying to force your seminar into a pre-recorded format.

However, once the seminar has been delivered digitally, or in person, the video can be uploaded as pre-recorded for those who want to follow along or are simply curious about your seminar’s content and might sign up for the next one.

To understand which format or type to set as your primary one, you must know the pros and cons of each kind of public speaking.

Digital public speaking emerged alongside the telethon selling format on cable TV. While the first telethons weren’t entirely digital, the format’s inception lies firmly in this period because TV’s shift to streaming brought about the first boom in digital public speaking.

In 2020, there was yet another shift as Corporate America got thoroughly familiarized with Zoom, a digital conferencing tool.

And once people knew how to use it to participate in meetings, listening to live talks was only a few clicks away. Zoom launched webinar mode, making it even more convenient to start giving talks to a large digital audience.

Still, there are multiple platforms through which you can engage in digital public speaking, including Facebook Live, Youtube Streaming, and even Twitch.

Pros of Digital Public Speaking

- Low overhead – You don’t need to book a conference center; people don’t have to pay to fly.

- Easy for higher frequency – You can easily deliver more talks in a shorter period, thanks to the lack of traveling involved.

Cons of Digital Public Speaking

- Harder to hold the audience’s attention – Task-switching is the key obstacle in digital public speaking, making it harder to deliver keynotes. However, interactive digital workshops really thrive in this environment.

Pros of on-Stage Public Speaking

- Better translates to other arenas – If you learn to speak from the stage, you can speak to smaller groups, give talks digitally, and hold a confident conversation. This doesn’t always work the other way: Zoom maestros aren’t as equipped to give a talk from a stage.

- Instant authority – The Lab Coat Effect is one where we automatically infer authority if someone resembles a figure of authority. That’s why stage presentations are important for big ideas. The audience is more receptive when they see you on a stage regardless of your credentials.

Cons of on-Stage Public Speaking

- Limits the ability to interact – Since the format allows monologuing, it can be easy to get carried away giving your talk without bringing the audience along. In some instances, it can be downright tough to engage more personally with people because the crowd is too big.

- Hard to master – While it can ultimately be an advantage, you must recognize it for the drawback that is initially, as getting on stage is difficult for most people with no prior experience. Even seasoned public speakers admit to being nervous before each talk.

Pros of Pre-Recorded Talks

- Room for error – Since pre-recorded talks are not live, you can get away with making errors, especially if you’re adept at editing. You also don’t have to be in front of a crowd and can talk to the camera as if it were your friend. This allows even the uninitiated to get involved with public speaking without taking extensive training.

- Simultaneous delivery for multiple talks – While it isn’t important for most people to give multiple tasks at once, it is possible to do so with a set of pre-recorded talks. If you’re a busy executive or a business owner, you can be more productive. If you’re trying to elevate your career as a professional speaker, a few pre-recorded webinars delivered to potential clients for free can help get your foot in the door without too much effort.

Cons of Pre-Recorded Talks

- Can become a crutch – The convenience of these talks is also their greatest drawback. You cannot give pre-recorded talks exclusively because that severely limits your public speaking muscles. Using them in conjunction with other forms of speaking is the ideal balance for skill maintenance and productivity boosting.

- Lower engagement – Since you are not able to interact live, you’re limited to predetermined engagement tools like asking people to imagine a scenario or posing rhetorical questions. You can pop in live at the end of your talk to take live questions. This hybridization or pre-recorded public speaking with digital public speaking is best for consultants and thought leaders.

Examples of Public Speaking

To be a great public speaker, you must consume great relevant content. That’s why you need to know what type of audio content constitutes public speaking. The following section covers examples of public speaking:

| In-person Keynote | On-stage public speaking |

| Zoom Webinar | Digital public speaking |

| Solo podcast | Recorded talk |

| Google Talks on Youtube | On-stage public speaking + Recorded talk |

| Graduation address / Commencement Address | On stage public speaking |

| Model UN Debate | On-stage public speaking + Recorded talk |

| Youtuber Apology/Explanation video | Recorded talk / Digital Public speaking |

| State of the Union Address | On-stage public speaking + Digital public speaking + Recorded talk |

| Facebook live stream webinar | Digital public speaking + Recorded talk |

Basic Elements of Public Speaking

Now that you know what kind of content you should consume as a budding public speaker let’s look at the key elements to watch out for. Most well-constructed speeches will include the following:

- Signposting – The beginning portion introduces not just the topic but sections of the talk, including what will be addressed later on. Look at the third paragraph of this post to get an idea of what signposting is.

- Main argument – This rests in the body of the speech, where the speaker makes the main point. You should never make a point without supporting it with logic, fact, and even a compelling narrative.

- Supporting the argument – As mentioned above, your argument needs support. Use analogies, metaphors, and of course, data to back up the point you’re making.

- Recap – The conclusion is the final part where your talk’s recap sits. Here, you tell your audience briefly the main points you have made without taking them down the details lane.

Tips to Become a Better Public Speaker

To become a better public speaker, you must use the observe, internalize, and practice formula. Here’s how you should go about it:

- Observe – Look at the types and examples of public speaking listed in this article and consume different talks that fall into all sorts of categories. Don’t rely too much on one speaker, or you may inadvertently become a knock-off.

- Internalize – By consuming content without judgment, you’ll start to internalize what you find compelling. You must let go of conscious deconstruction tendencies and simply consume content until it is second nature to you.

- Practice – Finally, the toughest and the most critical part of becoming a public speaker is simply practicing more often. Find opportunities to give talks. If you don’t find on-stage openings, simply give recorded talks or even stream your keynote. With enough practice, you’ll find your talks rising to the level of great public speakers whose content you so thoroughly consumed.

Credit to cookie_studio (on Freepik) for the featured image of this article (further edited)

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Shape and mass

- Volume and space

- Time and movement

- Principles of design

- Design relationships between painting and other visual arts

- Techniques and methods

- Fresco secco

- Buon fresco

- Watercolour

- Synthetic mediums

- French pastels

- Oil pastels

- Glass paintings

- Ivory painting

- Sand, or dry, painting

- Mechanical mediums

- Mixed mediums

- Mural painting

- Easel and panel painting

- Miniature painting

- Manuscript illumination and related forms

- Scroll painting

- Screen and fan painting

- Modern forms

- Kinds of imagery

- Portraiture

- Other subjects

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Tate - Painting

- LiveAbout - An Introduction to Painting

- Boise State Pressbooks - Introduction To Art - Painting

- Art in Context - What is Painting? – Explore the World of Visual Art Painting

- Humanities LibreTexts - Painting

- painting - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- painting - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

painting , the expression of ideas and emotions, with the creation of certain aesthetic qualities, in a two-dimensional visual language . The elements of this language—its shapes, lines, colours, tones, and textures—are used in various ways to produce sensations of volume, space, movement, and light on a flat surface. These elements are combined into expressive patterns in order to represent real or supernatural phenomena, to interpret a narrative theme, or to create wholly abstract visual relationships. An artist’s decision to use a particular medium, such as tempera , fresco , oil , acrylic , watercolour or other water-based paints, ink , gouache , encaustic , or casein , as well as the choice of a particular form, such as mural , easel, panel, miniature, manuscript illumination , scroll, screen or fan, panorama , or any of a variety of modern forms, is based on the sensuous qualities and the expressive possibilities and limitations of those options. The choices of the medium and the form, as well as the artist’s own technique, combine to realize a unique visual image.

(Read Sister Wendy’s Britannica essay on viewing art.)

Earlier cultural traditions—of tribes, religions, guilds, royal courts, and states—largely controlled the craft, form, imagery, and subject matter of painting and determined its function, whether ritualistic, devotional, decorative, entertaining, or educational. Painters were employed more as skilled artisans than as creative artists . Later the notion of the “fine artist” developed in Asia and Renaissance Europe. Prominent painters were afforded the social status of scholars and courtiers; they signed their work, decided its design and often its subject and imagery, and established a more personal—if not always amicable—relationship with their patrons .

During the 19th century painters in Western societies began to lose their social position and secure patronage. Some artists countered the decline in patronage support by holding their own exhibitions and charging an entrance fee. Others earned an income through touring exhibitions of their work. The need to appeal to a marketplace had replaced the similar (if less impersonal) demands of patronage, and its effect on the art itself was probably similar as well. Generally, artists in the 20th century could reach an audience only through commercial galleries and public museums, although their work may have been occasionally reproduced in art periodicals. They may also have been assisted by financial awards or commissions from industry and the state. They had, however, gained the freedom to invent their own visual language and to experiment with new forms and unconventional materials and techniques. For example, some painters combined other media, such as sculpture , with painting to produce three-dimensional abstract designs. Other artists attached real objects to the canvas in collage fashion or used electricity to operate coloured kinetic panels and boxes. Conceptual artists frequently expressed their ideas in the form of a proposal for an unrealizable project, while performance artists were an integral part of their own compositions . The restless endeavour to extend the boundaries of expression in art produced continuous international stylistic changes. The often bewildering succession of new movements in painting was further stimulated by the swift interchange of ideas by means of international art journals, traveling exhibitions, and art centres. Such exchanges accelerated in the 21st century with the explosion of international art fairs and the advent of social media , the latter of which offered not only new means of expression but direct communication between artists and their followers. Although stylistic movements were hard to identify, some artists addressed common societal issues, including the broad themes of racism, LGBTQ rights, and climate change .

This article is concerned with the elements and principles of design in painting and with the various mediums, forms, imagery, subject matter, and symbolism employed or adopted or created by the painter. For the history of painting in ancient Egypt , see Egyptian art and architecture . The development of painting in different regions is treated in a number of articles: Western painting ; African art ; Central Asian arts ; Chinese painting ; Islamic arts ; Japanese art ; Korean art ; Native American art ; Oceanic art and architecture ; South Asian arts ; Southeast Asian arts . For the conservation and restoration of paintings, see art conservation and restoration . For a discussion of the forgery of works of art, see forgery . For a discussion of the role of painting and other arts in religion, as well as of the use of religious symbols in art, see religious symbolism and iconography . For information on other arts related to painting, see articles such as drawing ; folk art ; printmaking .

Elements and principles of design

The design of a painting is its visual format: the arrangement of its lines, shapes, colours, tones, and textures into an expressive pattern . It is the sense of inevitability in this formal organization that gives a great painting its self-sufficiency and presence.

The colours and placing of the principal images in a design may be sometimes largely decided by representational and symbolic considerations . Yet it is the formal interplay of colours and shapes that alone is capable of communicating a particular mood, producing optical sensations of space, volume, movement, and light and creating forces of both harmony and tension , even when a painting’s narrative symbolism is obscure.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What It Takes to Give a Great Presentation

- Carmine Gallo

Five tips to set yourself apart.

Never underestimate the power of great communication. It can help you land the job of your dreams, attract investors to back your idea, or elevate your stature within your organization. But while there are plenty of good speakers in the world, you can set yourself apart out by being the person who can deliver something great over and over. Here are a few tips for business professionals who want to move from being good speakers to great ones: be concise (the fewer words, the better); never use bullet points (photos and images paired together are more memorable); don’t underestimate the power of your voice (raise and lower it for emphasis); give your audience something extra (unexpected moments will grab their attention); rehearse (the best speakers are the best because they practice — a lot).

I was sitting across the table from a Silicon Valley CEO who had pioneered a technology that touches many of our lives — the flash memory that stores data on smartphones, digital cameras, and computers. He was a frequent guest on CNBC and had been delivering business presentations for at least 20 years before we met. And yet, the CEO wanted to sharpen his public speaking skills.

- Carmine Gallo is a Harvard University instructor, keynote speaker, and author of 10 books translated into 40 languages. Gallo is the author of The Bezos Blueprint: Communication Secrets of the World’s Greatest Salesman (St. Martin’s Press).

Partner Center

Art Presentation – When Walls Have Meaning

by armandlee | Oct 1, 2015

Art presentation, like other artistic expressions, has become more experimental, more conceptual, more varied, and more personal. Interior design has evolved to meet the emotional and intellectual needs of more educated and worldly clients by challenging convention in the use of space, materials, scale, color, and texture. Personal and public spaces, like everything else, are becoming more interactive. Even traditional environments are filled with eclectic collections from family legacies, world travels, and expressions of personal interest.

As an integral part of interior design, art presentation must work on three dimensions: respecting the art, accessorizing the setting, and reflecting the importance of the art to the owner. Of these three, how the owner feels about the art is the driving force. Custom art presentation, which effectively balances all these considerations, requires an almost infinite assortment of profiles, finishes, and design details.

The Importance of the Art

In cases where the art is seen primarily as an investment, the presentation would be done to preserve and enhance its monetary value. In that case, archival presentation, conserving historic elements where possible, or using period-appropriate, formal presentation techniques would be a likely solution.

However, most important art is not valued primarily as an investment. Most art is used to set a tone and express ideas and feelings that are specific to the owner. Whether it is to evoke a comforting nostalgia, ritualize an event, impart energy or serenity, playfulness, humor, irony, worldly sophistication, personal style, or a simple appreciation of beauty, the presentation can greatly enhance that aspect of the artwork that is important to the owner. Only when the art presentation reinforces the emotional and intellectual relationship between the owner and the art does the presentation ‘feel right.’

Accessorizing the Setting

Where is the art to be displayed and how is it used? Is it in an intimate, personal space? Or will it be displayed in a formal, public one? Is the art to be a central focus, independently adding to the emotional and intellectual quality or the space? Or is it primarily to support the design idea?

Making appropriate framing and art presentation choices requires a close partnership with the designer. Site visits can help the art presenter understand the genre, and get accurate field measurements. Custom finish samples can be prepared to take into the setting or to coordinate with other suppliers. Custom profiles can be created to reference an important shape or pattern. Custom mirror engraving and silvering can be used to help the designer achieve a particular look or mood. Custom hanging methods, including an analysis of the appropriate angle at which to hang, lean, or cant the art of the wall can all influence the impact of the art. For three-dimensional works, cabinet or pedestal designs that complement the art and the setting require the design and fabrication skills of a fine cabinetmaker. The art of presentation is doing whatever it takes to get the details right.

With so many design rules being broken for interest and effect, understanding the underlying design principle for the space in which the artwork will reside is essential for satisfying art presentation. One of the more common design challenges is incorporating contemporary art in a traditional setting, or classic art in a contemporary setting. Frames and presentation treatments that make that transition comfortable frequently have ambiguous references to period design rendered with an unusual finish or a change in scale. The Tulip frame, shown right, combines sleek lines and a silver finish common in contemporary design, with a fluid carved corner detail more common to Art Nouveau. It is appropriate in traditional as well as contemporary settings, used as a mirror or as a complement to art.

Another common role for art is to add drama and formality to an ‘industrial’ or high-tech setting where the finish materials are exposed brick, brushed, rusted or painted steel, or hewn beam. ‘Organic’ finishes over profiles with strong, architectural, and graphic lines are a new formal language for art presentation. For example, the Deco Step frame, shown right, combines geometric forms frequently found in Art Deco design and architecture. The 12K white-gold finish is toned to gives it an organic texture unusual in fine finishes, with the fleeting impression of brushed steel.

The quality of light within the space is also an important consideration. Should UV protective glass be used? Is an independent light source required?

Respecting the Art

After understanding the emotional and physical context for the art, the final presentation decisions are driven by the art itself. Appropriate presentation means respecting the kind and level of detail, the strength of line, the color palette, the subject matter, and the materials used.

Effective presentation of artwork is as much an art as the creation of the art itself. Working knowledge of art history gives the art presenter a context that makes “respecting the art” possible. The eclectic nature of contemporary design requires a balance between convention and novelty. Having trained artists and art historians on staff with expertise in contemporary as well as classical art gives designers the creative resources to break “new ground” in the world of design with confidence.

Articles and Features

A Guide to Abstract Art

By Alice Godwin

From the feverish drips of Jackson Pollock to the geometric shapes of Piet Mondrian, the story of abstract art through Western art history is one filled with twists and turns. Abstraction is one of the myriad styles that make up the landscape of contemporary art . But to understand how abstraction has evolved, it is essential to start from the beginning.

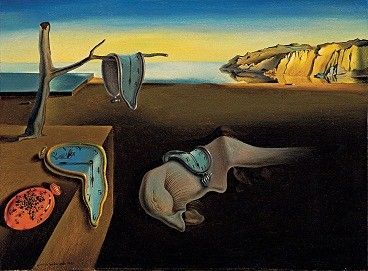

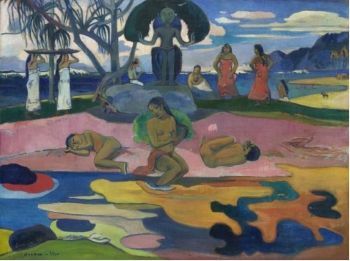

What is Abstract Art?

The definition of this artistic style is rooted in the representation of reality (or lack thereof!). Abstract artists exchange a faithful depiction of the world for a constellation of forms, colors, and gestures that together, conjure an intangible landscape of emotion and sensation.

A Short History of Abstraction

The history of abstract art painting and sculpture is impossible to map as a linear progression. Instead, this dynamic movement has stopped and started, splintered, and sparked entire rebellions against itself.

The Camera & Pioneers of Abstract Art

One of the crucial events in the tale of modern abstract art was the birth of photography in the early 19th century. For the first time, anyone who possessed a camera had the ability to capture the visible world. The function of art was forever changed; artists were no longer the custodians of reality, but explorers, free to tread the unknown paths of form and color with abandon.

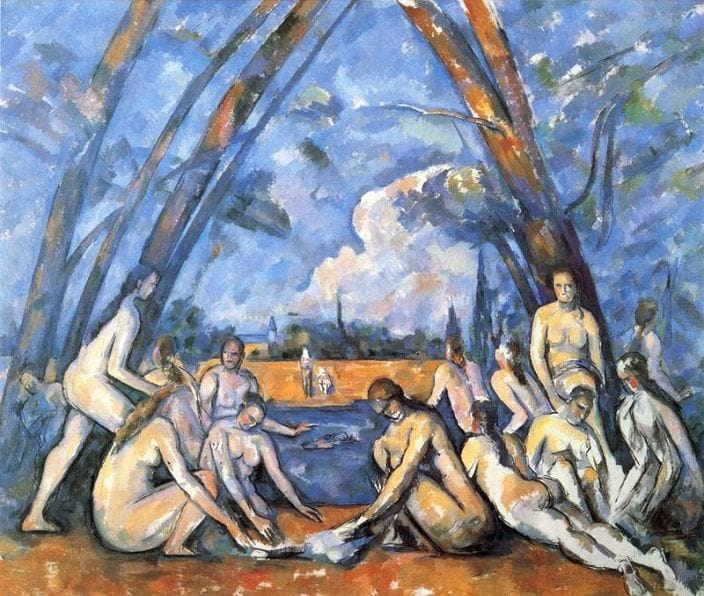

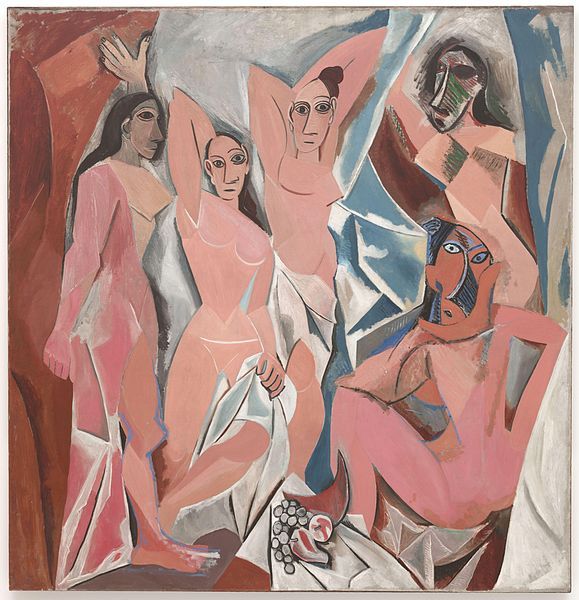

J.M.W Turner’s transcendent vistas abstracted land and seascapes into a sublime suggestion of nature. Claude Monet and the Impressionists rebelled against academic painting in pursuit of the effects of light and atmosphere. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque deconstructed reality by harnessing multiple viewpoints within a single Cubist work of art. Each of these movements paved the way for the eruption of abstraction that would occur in the 20th century, heralded by the crisis of the First World War.

The Early 20th Century Avant-Garde

With the turn of the century, abstraction took its place at the forefront of the avant-garde, challenging the status quo of representational art. In a letter to his gallerist, the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky claimed he had made the first ever abstract picture in 1911. In fact, the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint had beaten him to the punch, making her first radical abstract art paintings in 1906, years before Kandinsky would rid himself of representational content. Af Klint’s beguiling works spoke to a symbolic world of enigmatic forms and colors, which she claimed were inspired by the guiding hands of spirits.

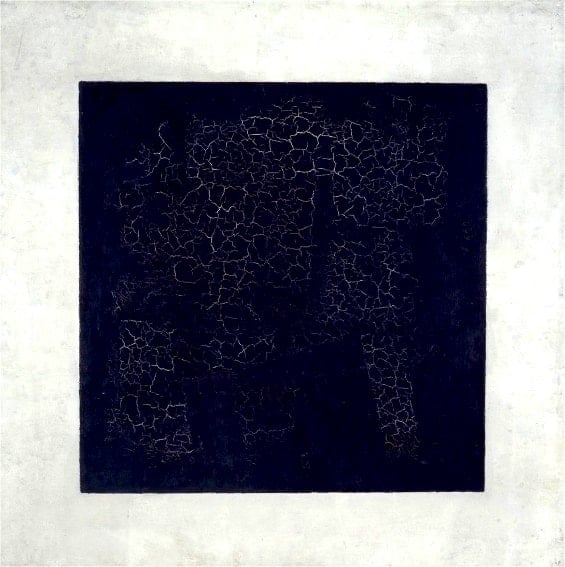

Kazimir Malevich’s The Black Square (1915) epitomized the revolution of abstraction at this moment. With its haunting simplicity, The Black Square marked a return to zero hour and was unveiled at The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10 in St. Petersburg as if it were a Russian Orthodox icon. Both Malevich and Kandinsky were pioneers of Non-Objective Art, which was devoid of any reference to the visible world. Piet Mondrian would similarly distill his art into an array of horizontal and vertical lines in primary colors, described as “the plastic expression of true reality.”

The Rise of Abstract Expressionism Art

In the 1940s, another critical language of abstraction appeared in New York City, which shifted the center of the art world’s gravity across the Atlantic. Jackson Pollock , named the greatest living painter in the United States by Life Magazine in 1949, pioneered an explosive method of dripping and splashing paint onto raw canvas laid on the floor. These gestures were an outpouring of the self, filled with poetic spontaneity. Rather than taking inspiration from the forms and hues of nature, Pollock declared: “I am nature.” Pollock and the other titans of Abstract Expressionism —Franz Kline, Arshile Gorky, and Willem de Kooning—gathered nightly at the Cedar Tavern in downtown Manhattan to discuss this new approach to abstraction.

Riotous gestures gave way to a second phase of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s, which harnessed the expressive potential of color. Helen Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique of pouring paint over unprimed canvas laid the foundations for a generation of Color Field painters, including Kenneth Noland, Sam Gilliam , and Mark Rothko . These artists conjured magnificent fields of color, in which figure and ground were one. Rothko enveloped the viewer in such an intense encounter with color that his paintings could bring them to tears.

By the 1960s and 1970s, an abstract minimalist art style of purity and order had emerged, rooted in the lessons of Malevich. Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Frank Stella , and Agnes Martin viewed art as possessing its own reality, rather than imitating another. Amongst the most famous abstract art of this period was Andre’s arrangement of bricks and Flavin’s neon works , as well as Judd’s rectilinear structures.

Abstraction & Contemporary Art

The identity of abstract art has continued to evolve into the 21st century. Artists such as Albert Oehlen and Christopher Wool pull apart the traditions of abstract art and embrace new technologies that test the very boundaries of what a painting can be. The future of abstraction is impossible to predict. But abstract artists will undoubtedly continue to plumb the depths of emotion and experience that lie beyond the visible world.

Collecting Abstract Art

Abstract works of art possess a vast appeal for collectors, who are able to infer their own meanings from their fabric of form and color. From radiant prime tones to the more restrained palettes of black and white, examples of wall abstract art can be found to suit any home decor.

To date, the most expensive painting of abstract art is Willem de Kooning’s Interchange (1955), sold privately in 2015 for $300 million, followed by Jackson Pollock’s Number 17A (1948), which also was sold privately in 2015 for $200 million. The market continues to thrive, as historic abstract artists once overlooked are now brought into the light. Most notably, the works of women and Black artists, have received growing recognition in recent years, including Joan Mitchell , Alma Thomas , Howardena Pindell , Lee Krasner , Stanley Whitney , Frank Bowling , and Jack Whitten . As galleries and auction houses continue to bring abstract art for sale, taste for this pivotal movement in the history of art remains robust.

Relevant sources to learn more

Discover abstract art for sale on Artland

Learn more about the art movements that had a crucial role in the development of abstract art: Symbolism Impressionism Post-Impressionism Fauvism Expressionism Cubism Constructivism Suprematism De Stijl Bauhaus Abstract Expressionism Op Art Minimalism

Keep reading on Artland Magazine Rethinking Abstract Expressionism: read about the Ninth Street Women Line Art. Follow where it leads Learn about Op Art

Wondering where to start?

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Definition of Art

The definition of art is controversial in contemporary philosophy. Whether art can be defined has also been a matter of controversy. The philosophical usefulness of a definition of art has also been debated.

Contemporary definitions can be classified with respect to the dimensions of art they emphasize. One distinctively modern, conventionalist, sort of definition focuses on art’s institutional features, emphasizing the way art changes over time, modern works that appear to break radically with all traditional art, the relational properties of artworks that depend on works’ relations to art history, art genres, etc. – more broadly, on the undeniable heterogeneity of the class of artworks. The more traditional, less conventionalist sort of definition defended in contemporary philosophy makes use of a broader, more traditional concept of aesthetic properties that includes more than art-relational ones, and puts more emphasis on art’s pan-cultural and trans-historical characteristics – in sum, on commonalities across the class of artworks. Hybrid definitions aim to do justice to both the traditional aesthetic dimension as well as to the institutional and art-historical dimensions of art, while privileging neither.

1. Constraints on Definitions of Art

2.1 some examples, 3.1 skepticisms inspired by views of concepts, history, marxism, feminism, 3.2 some descendants of skepticism, 4.1 conventionalist definitions: institutional and historical, 4.2 institutional definitions, 4.3 historical definitions.

- 4.4 Functional (mainly aesthetic) definitions

4.5 Hybrid (Disjunctive) Definitions

5. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries.

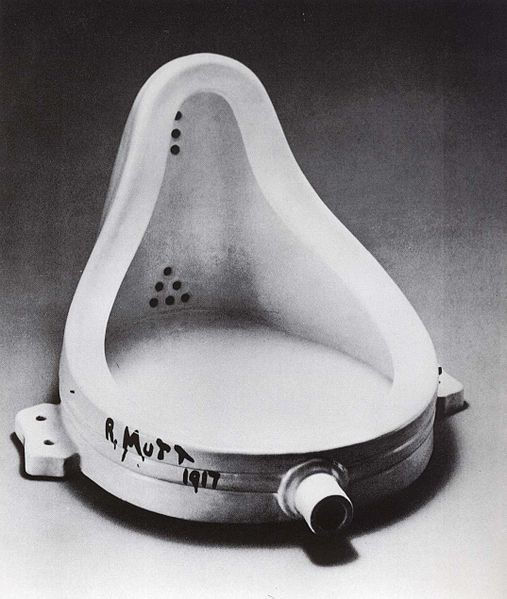

Any definition of art has to square with the following uncontroversial facts: (i) entities (artifacts or performances) intentionally endowed by their makers with a significant degree of aesthetic interest, often greatly surpassing that of most everyday objects, first appeared hundreds of thousands of years ago and exist in virtually every known human culture (Davies 2012); (ii) such entities are partially comprehensible to cultural outsiders – they are neither opaque nor completely transparent; (iii) such entities sometimes have non-aesthetic – ceremonial or religious or propagandistic – functions, and sometimes do not; (iv) such entities might conceivably be produced by non-human species, terrestrial or otherwise; and it seems at least in principle possible that they be extraspecifically recognizable as such; (v) traditionally, artworks are intentionally endowed by their makers with properties, often sensory, having a significant degree of aesthetic interest, usually surpassing that of most everyday objects; (vi) art’s normative dimension – the high value placed on making and consuming art – appears to be essential to it, and artworks can have considerable moral and political as well as aesthetic power; (vii) the arts are always changing, just as the rest of culture is: as artists experiment creatively, new genres, art-forms, and styles develop; standards of taste and sensibilities evolve; understandings of aesthetic properties, aesthetic experience, and the nature of art evolve; (viii) there are institutions in some but not all cultures which involve a focus on artifacts and performances that have a high degree of aesthetic interest but lack any practical, ceremonial, or religious use; (ix) entities seemingly lacking aesthetic interest, and entities having a high degree of aesthetic interest, are not infrequently grouped together as artworks by such institutions; (x) lots of things besides artworks – for example, natural entities (sunsets, landscapes, flowers, shadows), human beings, and abstract entities (theories, proofs, mathematical entities) – have interesting aesthetic properties.

Of these facts, those having to do with art’s contingent cultural and historical features are emphasized by some definitions of art. Other definitions of art give priority to explaining those facts that reflect art’s universality and continuity with other aesthetic phenomena. Still other definitions attempt to explain both art’s contingent characteristics and its more abiding ones while giving priority to neither.

Two general constraints on definitions are particularly relevant to definitions of art. First, given that accepting that something is inexplicable is generally a philosophical last resort, and granting the importance of extensional adequacy, list-like or enumerative definitions are if possible to be avoided. Enumerative definitions, lacking principles that explain why what is on the list is on the list, don’t, notoriously, apply to definienda that evolve, and provide no clue to the next or general case (Tarski’s definition of truth, for example, is standardly criticized as unenlightening because it rests on a list-like definition of primitive denotation; see Field 1972; Devitt 2001; Davidson 2005). Corollary: when everything else is equal (and it is controversial whether and when that condition is satisfied in the case of definitions of art), non-disjunctive definitions are preferable to disjunctive ones. Second, given that most classes outside of mathematics are vague, and that the existence of borderline cases is characteristic of vague classes, definitions that take the class of artworks to have borderline cases are preferable to definitions that don’t (Davies 1991 and 2006; Stecker 2005).

Whether any definition of art does account for these facts and satisfy these constraints, or could account for these facts and satisfy these constraints, are key questions for aesthetics and the philosophy of art.

2. Definitions From the History of Philosophy

Classical definitions, at least as they are portrayed in contemporary discussions of the definition of art, take artworks to be characterized by a single type of property. The standard candidates are representational properties, expressive properties, and formal properties. So there are representational or mimetic definitions, expressive definitions, and formalist definitions, which hold that artworks are characterized by their possession of, respectively, representational, expressive, and formal properties. It is not difficult to find fault with these simple definitions. For example, possessing representational, expressive, and formal properties cannot be sufficient conditions, since, obviously, instructional manuals are representations, but not typically artworks, human faces and gestures have expressive properties without being works of art, and both natural objects and artifacts produced solely for homely utilitarian purposes have formal properties but are not artworks.