- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Human-Centered Design (HCD)

What is human-centered design (hcd).

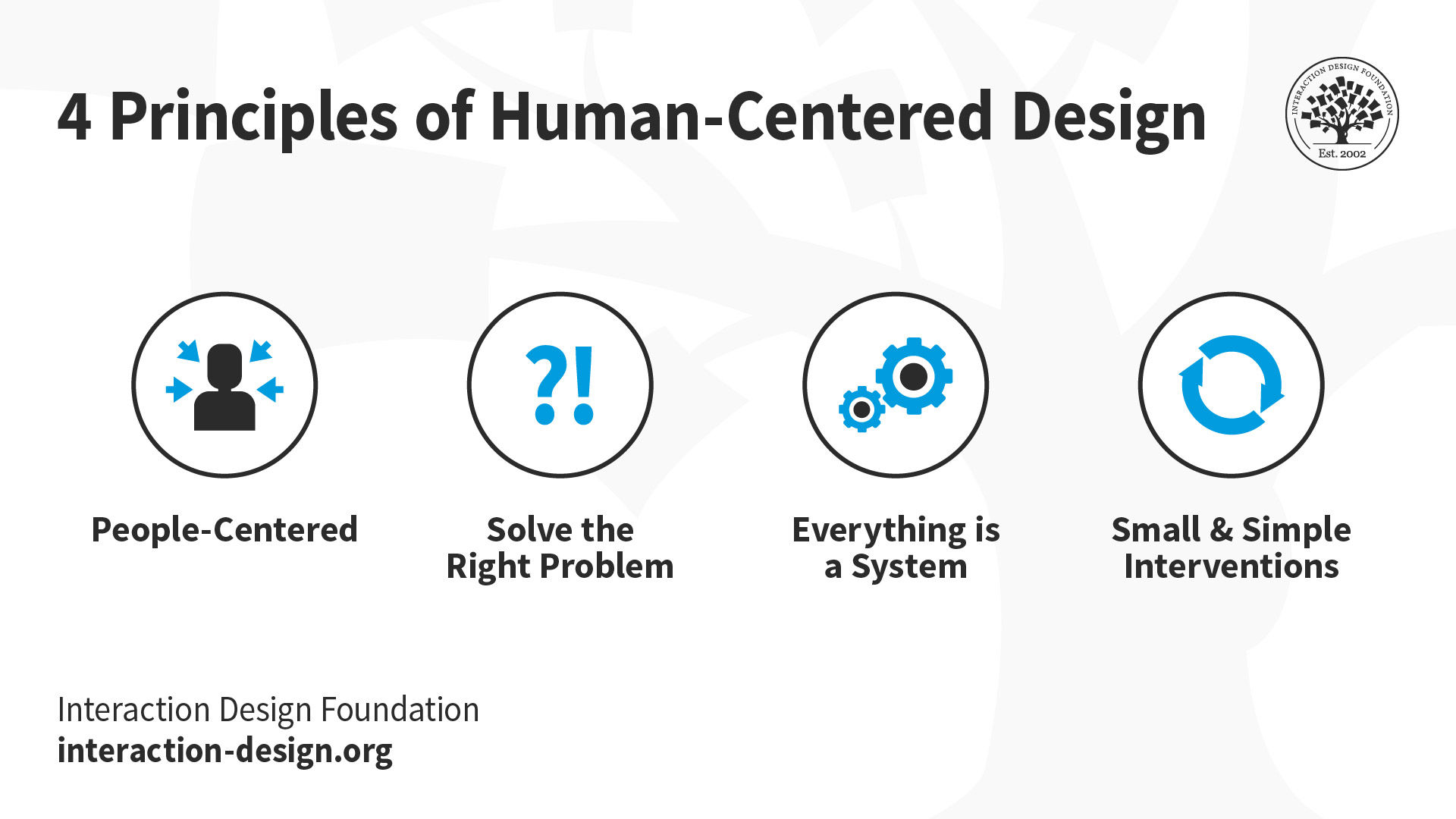

Human-centered design is a practice where designers focus on four key aspects. They focus on people and their context. They seek to understand and solve the right problems, the root problems. They understand that everything is a complex system with interconnected parts. Finally, they do small interventions. They continually prototype, test and refine their products and services to ensure that their solutions truly meet the needs of the people they focus on.

Cognitive science and user experience expert Don Norman sees it as a step above user-centered design .

“The challenge is to use the principles of human-centered design to produce positive results, products that enhance lives and add to our pleasure and enjoyment. The goal is to produce a great product, one that is successful, and that customers love. It can be done.” — Don Norman, “Grand Old Man of User Experience”

See why human-centered design is a vital approach for accommodating real users—real people.

- Transcript loading…

The Trouble with “Users” is They’re Only Human

At many points in technological history, Don Norman helped designers understand their responsibility to the people who use the things they design. Great advances were made in electronics and computing throughout the second half of the 20th century. The problem was, the designers of many systems often overlooked the human limitations of the people who had to interact with them.

Early computers were extremely hard to understand. The first ones — created in the 1940s — required specialists to operate them in closed environments. By the 1980s, things had changed; A large portion of smaller computers were being used by people without specialist knowledge. Problems were bound to arise, and did. The early Unix system Ed (for “Editor”), for example, did not prompt users to save their changes, causing many users to erase their work when turning off their computers. Highly visible prompts to save our work were yet to come.

From no save prompts, to the “Do you want to save changes” dialog box, to auto-save: The save functionality in documents has been iterated over the years to improve the experience for the people working with these tools.

Don Norman also studied the control rooms of potentially hazardous industrial centers and aviation safety. Following the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in 1979, he was involved in analyzing the causes and potential solutions. A partial meltdown of a power-station reactor had released dangerous radioactive material into the environment. The problem centered around, not the highly competent staff members, but the design of the control room itself.

From design mistakes such as this, we learned crucial lessons. It was clear that designers had to accommodate the human needs of their systems’ user ship. There could be no room for ambiguity or misleading controls, for instance. Designers would instead have to anticipate human users extensively through how each system looked, worked and responded to them, which aligns with circular economy principles to maximize resource efficiency and sustainability. So, rather than focus on the aesthetics of the interface and the design itself, designers needed to understand and tailor experiences for the people at the controls, accounting for their various states of mind while interacting with and reacting to changes in the system. To avoid disasters, the dehumanizing idea of “users” had to vanish so designers could put people first in design. It was time for human- or, better still, people-centered design .

Follow the Clear Path to Human-Centered Design

In 1986, Norman and co-author Stephen Draper’s User Centered System Design: New Perspectives on Human-Computer Interaction was published. The result of extensive collaboration between researchers across the U.S., Europe and Japan, this comprehensive volume represented a shift in human-computer interaction. However, the authors realized they didn’t like the term “users”; the emphasis demanded a more “human” entity in control. Their timing was superb. Not only had the home-computing market exploded, but strides in technology would soon usher in the Internet age, greater connectivity and more complexity in the systems that people of all types would use.

Norman coined the term “user experience” shortly afterwards. This signaled a focus on the needs of the people who used products throughout their experiences. Norman explained the reason for the evolution away from “user” was to help designers humanize the people whose needs they designed for. Human-centered design has four principles:

People-centered : Focus on people and their context in order to create things that are appropriate for them. Participatory design ensures user involvement in the process.

Understand and solve the right problems , the root problems: Understand and solve the right problem, the root causes, the underlying fundamental issues. Otherwise, the symptoms will just keep returning.

Everything is a system: Think of everything as a system of interconnected parts.

Small and simple interventions: Do iterative work and don't rush to a solution. Try small, simple interventions and learn from them one by one, and slowly your results will get bigger and better. Continually prototype, test and refine your proposals to make sure that your small solutions truly meet the needs of the people you focus on.

It's important to remember, as we focus on the human aspect, we expand our scope to societies and, ultimately, humanity-centered design . And as our world becomes more intricately involved with complex socio-technical systems and wicked problems to address, the insights we leverage from human-centered design will continue to prove essential.

Interaction Design Foundation, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Learn More about Human-Centered Design

To learn more on human-centered design, take our courses:

Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman

Design for a Better World with Don Norman

Norman, Donald A. Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered . Cambridge, MA, MA: The MIT Press, 2023.

Read this JND article for additional insights about the human-centered design principles.

This thought-provoking MovingWorlds post explores human-centered design extensively.

Questions related to Human-Centered Design

Human-centered design is vital because it ensures that we create solutions tailored to human needs, cultures, and societies. It is a discipline that emphasizes a people-centric approach, solving the right problems, recognizing the interconnectedness of everything, and not rushing to solutions. It involves working with multidisciplinary teams and experts, and most importantly, it has to come from the people, embracing a community-driven design approach. This approach is a subset of humanity-driven design, which aims to address the major challenges humanity faces and, ultimately, save the planet.

Human-centered design (HCD) is a methodology that places the user at the heart of the design process. It seeks to deeply understand users' needs, behaviors and experiences to create effective solutions catering to their unique challenges and desires. HCD emphasizes empathy, extensive user research, and iterative testing to ensure that the final product or solution genuinely benefits its end-users and addresses broader societal issues.

Agile is primarily a project management and product development approach that values delivering workable solutions and iterating based on customer feedback. Agile teams break projects into small, manageable chunks and work in short bursts, called "sprints," which allows for frequent reassessment and course corrections.

While there's some overlap in their collaborative and iterative natures, the core difference lies in their objectives: HCD is about understanding and solving for the human experience, while agile is about efficiently managing and adapting work processes to changing requirements.

Design thinking is a broader concept that includes human-centered design to solve major problems on a global and local scale. Human Centered Design is narrower in scope and aims to make interactive systems usable and useful.

For a more thorough understanding of these design approaches, please watch this informative video.

Human-centered design, as explained by Don Norman in the video above, focuses on people and their needs, even when addressing broad societal issues. It emphasizes creating solutions that cater to individuals, communities, and larger groups. Although it tackles significant challenges, its essence remains rooted in understanding and designing for humanity.

Human-centered design is used to design efficient and usable products. However, Don Norman encourages designers to apply the principles of human-centered design to address large societal problems to ensure solutions meet the needs and experiences of people.

As highlighted in the video above, human-centered designers collaborate with professionals from other fields like engineering, computer science, and public health. HCD’s uniqueness lies in emphasizing design by the people and for the people.

While both prioritize the user, human-centered design is broader than UX design. UX often focuses on websites and digital interfaces, as mentioned in this video.

In contrast, human-centered design encompasses all types of products and indeed even larger societal challenges to ensure solutions cater to people's needs and experiences.

Human-centered design prioritizes understanding and addressing the needs of people. Unlike designs that emphasize aesthetics over usability, human-centered design values function and user well-being, as highlighted in this video.

It considers the broader socio-technical system, ensuring sustainable and user-centric solutions.

Discover the principles of human-centered design through Interaction Design Foundation's in-depth courses: Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman offers a contemporary perspective on design thinking, while Design for a Better World with Don Norman emphasizes designing for positive global impact. To deepen your understanding, Don Norman's seminal book, " Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered ," from MIT Press, is an invaluable resource.

Answer a Short Quiz to Earn a Gift

What is the primary goal of Human-Centered Design (HCD)?

- To create aesthetically pleasing designs

- To focus on people and their needs

- To reduce the cost of production

Which of the following is a core principle of Human-Centered Design?

- Everything is a system.

- Implement the first idea quickly.

- Solve the most superficial problems first.

Why is iterative prototyping important in Human-Centered Design?

- Because it continually tests and refines solutions.

- Because it finalizes designs quickly.

- Because it only applies the first round of user feedback.

How does Human-Centered Design approach problem-solving?

- It addresses surface-level issues.

- It focuses on technical specifications first.

- It understands and solves root problems.

Why is understanding the context important in Human-Centered Design?

- To apply a singular solution

- To reduce the time spent on research

- To tailor solutions to specific user environments and needs

Better luck next time!

Do you want to improve your UX / UI Design skills? Join us now

Congratulations! You did amazing

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

Check Your Inbox

We’ve emailed your gift to [email protected] .

Literature on Human-Centered Design (HCD)

Here’s the entire UX literature on Human-Centered Design (HCD) by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Human-Centered Design (HCD)

Take a deep dive into Human-Centered Design (HCD) with our course Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman .

In this course, taught by your instructor, Don Norman, you’ll learn how designers can improve the world , how you can apply human-centered design to solve complex global challenges , and what 21st century skills you’ll need to make a difference in the world . Each lesson will build upon another to expand your knowledge of human-centered design and provide you with practical skills to make a difference in the world.

“The challenge is to use the principles of human-centered design to produce positive results, products that enhance lives and add to our pleasure and enjoyment. The goal is to produce a great product, one that is successful, and that customers love. It can be done.” — Don Norman

All open-source articles on Human-Centered Design (HCD)

Human-centered design: how to focus on people when you solve complex global challenges.

- 3 years ago

Design Thinking: Top Insights from the IxDF Course

- 3 weeks ago

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is Human-Centered Design?

- 15 Dec 2020

One of the primary reasons startups fail is a lack of market need. Or, in more straightforward terms: The founders built a product or service no one wants.

Creating a successful business requires identifying an underserved need , validating your idea , and crafting an effective value proposition . When taking these steps, one way to ensure you’re on the right path and developing products and services the market will adopt and embrace is bringing prospective customers into the process and leveraging human-centered design.

Access your free e-book today.

Human-centered design is a problem-solving technique that puts real people at the center of the development process, enabling you to create products and services that resonate and are tailored to your audience’s needs.

The goal is to keep users’ wants, pain points, and preferences front of mind during every phase of the process. In turn, you’ll build more intuitive, accessible products that are likely to turn a higher profit because your customers have already vetted the solution and feel more invested in using it.

The Phases of Human-Centered Design

In Harvard Business School Online’s Design Thinking and Innovation Course , HBS Dean Srikant Datar breaks human-centered design down into four stages :

Here’s what each step of the process means and how you can implement it to create products and services people love.

This first phase is dedicated to collecting data and observing your customers to clarify the problem and how you might solve it. Rather than develop products based on assumptions, you conduct user research and assess customer needs to determine what prospective buyers want.

The clarify phase requires empathy—the capability of understanding another person’s experiences and emotions. You need to consider your customers’ perspectives and ask questions to determine what products they’re currently using, why and how they’re using them, and the challenges they’re trying to solve.

During this phase, you want to discover customers’ pain points , which Dean Datar breaks down into two types:

- Explicit : These are pain points users can describe; they’re aware of what frustrates them about their current experience.

- Latent : These are pain points users can’t describe and might not even know exist.

“Users will be upfront about explicit pain points,” says Dean Datar in Design Thinking and Innovation . “But researchers will need to dig into the experience—observing, listening, and trying it for themselves to get at the latent pain points that lead to transformative innovation.”

To determine your customers’ pain points, observe people using your product and conduct user interviews . Ask questions such as:

- What challenge were you trying to solve when you bought this product?

- What other options did you consider when making your decision?

- What made you choose this product over the alternatives?

With each answer, you’ll start to generate insights you can use to create a problem statement from your users’ perspective. That’s what you’ll try to solve in the following phases.

The inspiration you gather in the first phase will lead you to the second: ideate. During this stage, you can apply different design thinking tools, such as systematic inventive thinking (SIT) or brainstorming, to overcome cognitive fixedness —a mindset in which you consciously or unconsciously assume there’s only one way to interpret or approach a situation.

Once you’ve overcome cognitive fixedness, the goal is to generate dozens of ideas to amplify creativity and ensure no one gets attached to a potential solution before it’s been tested.

The develop phase is when you combine and critique the ideas you’ve brainstormed to create a range of possible solutions. By combining and evaluating your ideas, you can better meet users’ needs and determine what you want to move into prototyping to reduce costs, save time, and increase your final product’s quality.

Three characteristics of human-centered design that are vital to consider when critiquing ideas are desirability, feasibility, and viability.

- Desirability : Does this innovation fulfill user needs, and is there a market for it?

- Feasibility : Is this functionally possible? Does the organization have the resources to produce this innovation? Are there any legal, economic, or technological barriers?

- Viability : Is this innovation sustainable? Can the company continue to produce or deliver this product profitably over time?

When you start prototyping, you should have presumed answers to these questions so you can learn more about your concepts quickly and, ideally, at a low cost.

“It’s important to evaluate concepts and create prototypes early and often so that you can foster an experimentation mindset and develop tested solutions that are ready for implementation,” says Dean Datar in Design Thinking and Innovation .

4. Implement

The final phase of the process is implementation. During this stage, it’s crucial to communicate your innovation’s value to internal and external stakeholders, including colleagues and consumers, to bring it to market successfully, encourage adoption, and maintain growth.

In the implementation phase, take time to reflect on your organization’s culture and assess group dynamics. Is your team empowered to develop and iterate on user-focused solutions? You can’t continue creating innovative solutions without the right culture.

It’s important to note that your work isn’t over once you reach the final phase. Customers’ wants and needs will continue to evolve. Your goal is to adapt to meet them. Keeping humans at the center of the development process will ensure you’re continuously innovating and achieving product-market fit.

Human-Centered Design in Action

A great example of human-centered design is a children’s toothbrush that’s still in use today. In the mid-nineties, Oral-B asked global design firm IDEO to develop a new kid’s toothbrush. Rather than replicating what was already on the market—a slim, shorter version of an adult-sized toothbrush—IDEO’s team went directly to the source; they watched children brush their teeth.

What they realized is that kids had a hard time holding the skinnier toothbrushes their parents used because they didn’t have the same dexterity or motor skills. Children needed toothbrushes with a big, fat, squishy grip that was easier to hold on to.

“Now every toothbrush company in the world makes these,” says IDEO Partner Tom Kelley in a speech . “But our client reports that after we made that little, tiny discovery out in the field—sitting in a bathroom watching a five-year-old boy brush his teeth—they had the best-selling kid’s toothbrush in the world for 18 months.”

Had IDEO’s team not gone out into the field—or, in this case, children’s homes—they wouldn’t have observed that small opportunity, which turned a big profit for Oral-B.

Leveraging Human-Centered Design in Your Business

By leveraging human-centered design in your business, you can avoid becoming another startup statistic and instead gain a competitive edge by creating products and services that customers love.

Are you interested in learning more about the benefits of human-centered design? Explore our seven-week Design Thinking and Innovation course , one of our entrepreneurship and innovation courses . Not sure which course is right for you? Download our free flowchart to find your fit.

This post was updated on January 6, 2023. It was originally published on December 15, 2020.

About the Author

What is human-centered design

table of contents

Setting the stage for human-centered design.

In a world of complexities and technological advancements, design has transcended from mere aesthetics to becoming the crucible where functionality and user experience merge. This transformation mandates a revision of traditional design paradigms.

Introducing Human-Centered Design (HCD) as a paradigm shift

Enter Human-Centered Design, a disruptive methodology that situates the human experience at the prime of the design process . Unlike traditional design approaches, which often focus on technical or business requirements, HCD seeks to combine these necessities with a deep understanding of the human psyche.

The DNA of Human-Centered Design

Historical context: when and why hcd came to be.

Emerging from the shadows of ergonomics and cognitive psychology, Human-Centered Design came into prominence in the late 20th century. The difficulties of the Information Age, marked by an unprecedented explosion of digital interfaces, needed a design approach that transcended mere functionality and delved into user satisfaction and inclusivity.

Key pioneers and thought leaders: The architects of HCD

Pioneers such as Don Norman and Jane Fulton Suri have been instrumental in architecting the principles of HCD. Their oeuvre, resonating with empirical research and multidisciplinary insights, has laid the epistemological groundwork for this transformative design ethos.

Defining Human-Centered Design

The ISO defines Human-Centered Design as an "approach to interactive systems development that aims to make systems usable and useful." While this definition encapsulates the foundational elements, it warrants further dissection to appreciate its profundities.

Understanding the human element: A simple explanation

In layman's terms, HCD is the deliberate manipulation of design variables to prioritize human needs, emotions, and capabilities at each phase of the design process.

HCD vs. traditional design: A comparative snapshot

Unlike traditional design paradigms that are often fastidiously linear and compartmentalized, HCD adopts a more cyclical and integrated approach, systematically intertwining user research, ideation, prototyping, and evaluation.

The Core Principles of Human-Centered Design

Empathy: the heart of the process.

Empathy serves as the sine qua non of HCD. It obliges designers to immerse themselves in the user's world, enabling a nuanced understanding of pain points, aspirations, and contextual limitations.

Collaboration: The strength of the collective

HCD extols the virtues of collaborative multidisciplinary teamwork. It incorporates perspectives from psychology, anthropology, and data science to engender simultaneously innovative and practical solutions.

Iteration: The cycle of perpetual improvement

Iterative design is a cornerstone of HCD. This involves a cyclical process of prototyping , testing, analyzing, and refining a product or service in response to user feedback.

Usability: The end goal

The conclusion of the HCD process is a product that not only settles a particular problem but does so in a way that is intuitive, accessible, and pleasurable for the user.

Anatomy of the HCD methodology

The four pillars: stages of human-centered design, research: digging for user gold.

User research, the first pillar, employs qualitative and quantitative methods to excavate deep-seated user needs, preferences, and behavior patterns. This encompasses ethnographic studies, contextual interviews, and even heuristic evaluations.

Ideation: The creative cauldron

In this stage, creative techniques like brainstorming , mind mapping, and lateral thinking are employed to generate many potential solutions.

Prototyping: Making ideas tangible

The abstract is made corporeal through prototyping. This low-fidelity representation of the final product serves as a test bed for ideas, allowing for inexpensive, rapid iterations.

Testing: The reality check

Usability testing offers empirical data on how real users interact with the prototype. It exposes any incongruences between user expectations and the design's performance, thereby directing iterative refinements.

Tools of the Trade: The HCD toolkit

Interview techniques: peeling back the layers.

Semi-structured interviews and the "Five Whys" technique are invaluable tools for unearthing the intrinsic motivations and tacit knowledge that often elude more formal research methods.

Surveys and questionnaires: Data-driven design

Well-crafted questionnaires can yield a cornucopia of quantitative data, enhancing the rigor and objectivity of the design process.

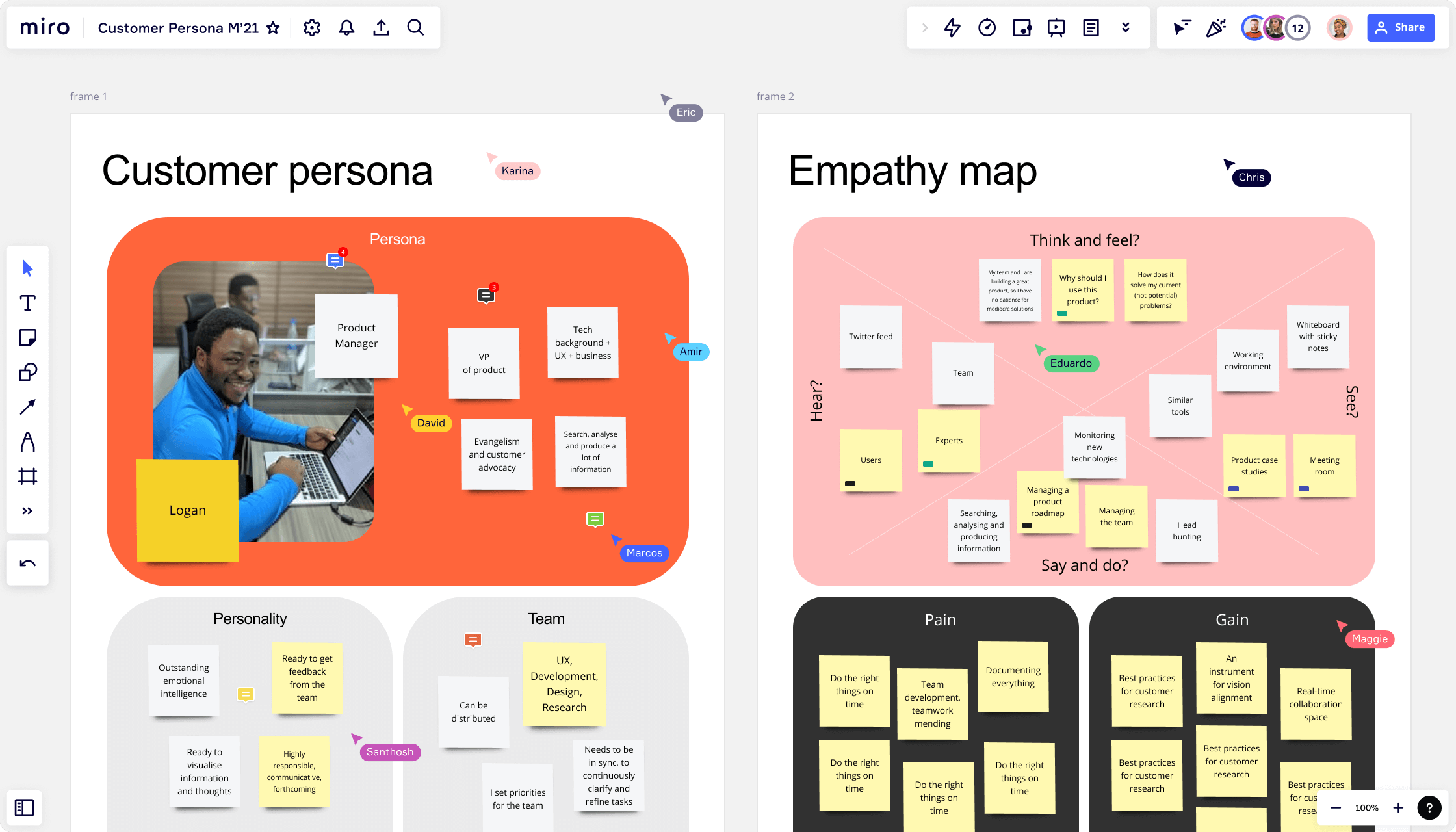

User Personas: Crafting character profiles

Personas , or synthetic profiles of archetypal users, are instrumental in focusing the design process, providing a clear demographic and psychographic context.

Wireframes and mockups: The Blueprint before the build

Wireframes and mockups serve as schematic diagrams of the digital world, delineating the architecture and flow without being burdened by aesthetic details.

The impact of Human-Centered Design

Elevating user experience and usability, real-world examples: hcd success stories.

Companies like Apple and Airbnb have transmogrified entire industries by clever application of HCD principles, demonstrating how empathetic design can catalyze monumental shifts in user experience and market dynamics.

How HCD makes products more intuitive

By synthesizing user needs and technological capabilities, HCD engenders products that are not just functional but also intrinsically intuitive, reducing the cognitive load on the user.

Business Case: The ROI of Human-Centered Design

Customer retention: the loyalty loop.

With increasingly discerning consumers, HCD is a potent tool for engendering brand loyalty through superior user experiences.

Increased sales and market share: Numbers don't lie

Various empirical studies substantiate that companies implementing HCD strategies frequently experience market share and profitability surges.

Brand Enhancement: The Halo Effect

An effectively designed product doesn't just solve a problem. It elevates the brand, creating a halo effect that augments consumer trust and brand equity.

Beyond Business: HCD for societal good

Case studies in healthcare: saving lives by design.

In fields like healthcare, the ramifications of HCD transcend commercial metrics and extend to life-altering impacts, such as improved patient care through intuitive medical devices.

Environmental sustainability: Designing a greener future

HCD principles are increasingly harnessed to solve grand challenges like climate change, emphasizing sustainable practices without compromising usability.

Public policy: When governments embrace HCD

Various governmental bodies are adopting HCD methodologies to craft policies and services that resonate more deeply with citizens, enhancing civic engagement and governance.

Challenges, criticisms, and ethical considerations

The potential downsides of human-centered design, the time and resource conundrum.

While the benefits of HCD are manifold, it is also a resource-intensive process requiring an amalgamation of diverse skill sets, potentially escalating both time and monetary investments.

When HCD fails: Examples and lessons

Even with the best intentions, HCD is not infallible. The failures, often arising from a lack of genuine user involvement or superficial implementation, provide salient lessons for future endeavors.

Ethical questions: The double-edged sword of HCD

Manipulative designs: when user engagement goes too far.

An ethical dilemma exists where design can become too persuasive, trapping users in a cycle of addictive behavior.

Inclusivity and bias: Ensuring HCD is for everyone

To be genuinely human-centered, design must be inclusive, catering to diverse demographics and accessibility needs, avoiding the perpetuation of societal biases.

Conclusion: The lasting legacy of Human-Centered Design

A recap of why hcd matters.

HCD amalgamates empirical rigor with empathetic insights, making it an invaluable framework for crafting solutions that are effective and resonate on a deeply human level.

The future: What's next in the evolution of HCD?

As emerging technologies like AI and Virtual Reality continue to evolve, so too will the methods and applications of Human-Centered Design, promising ever more nuanced and responsive user experiences.

Recommended reading and resources

For those intrigued by the potentialities of HCD, seminal works like "The Design of Everyday Things" by Don Norman or IDEO's "Human-Centered Design Toolkit" offer deep dives into this transformative methodology.

Glossary of terms

Empathy : Deep understanding of user needs and emotions.

Usability : The ease with which users can effectively use a product.

Iterative Design : A cyclical process of refining a product based on user feedback.

Persona : A synthetic profile representing an archetypal user.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Human-Centered Design? : An approach that integrates user needs and business requirements into a cohesive design process.

Why is it important? : It creates more usable, effective, and impactful products, enhancing user satisfaction and business metrics.

How is it different from traditional design methods? : Unlike traditional design, HCD involves users throughout the design process, employs multidisciplinary teams, and emphasizes iterative refinement.

What is collaborative design?

Read article

The 5 Design Thinking Steps

What is design thinking?

Get on board in seconds

Join thousands of teams using Miro to do their best work yet.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Guidance on building better digital services in government

Introduction to human-centered design

Hcd principles.

Reading time: 2 minutes

The guiding principles of human-centered design include:

- No wrong ideas

- Collaboration

When engaging in HCD research:

- Listen deeply for what people say they want and need, and how they may be creating workarounds to meet their needs.

- Listen for the root causes that inform the attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs of the people you’re interviewing.

- Be aware of your own internal biases or judgments.

- Fail early; fail fast; fail small. Know that iteration is learning.

- Learn first, don’t jump to solutions.

- Be inclusive and seek out multiple perspectives from both researchers and research subjects.

- Be flexible in your thinking and plans. Adapt to changing conditions. Sometimes unexpected events or even kinks in the process can open the door to key insights.

HCD in practice

HCD allows us to understand the types of experiences customers want from a system, product, or service. We refer to the customers’ desired experience as the “frontstage” of the design effort. HCD helps us craft the processes that create those desired experiences. We refer to this behind-the-scenes work as “the backstage’’ of the design effort. By tending to both the front and back stages, HCD allows us to put the customer at the center of our design development.

Case in point

The HCD approach has already created immense value for agencies. For example, a redesign of USAJOBS (the hub for federal hiring with nearly 1 billion job searches annually by over 180 million people) resulted in a 30% reduction in help desk tickets after the first round of improvements. This reflects an easier experience for users, and creates savings in support costs.

Header image credit: Vladimir Kononok/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Join 60,000 others in government and subscribe to our newsletter — a round-up of the best digital news in government and across our field.

Digital.gov

An official website of the U.S. General Services Administration

The faculty and students in Human Centered Design share a multidisciplinary approach to research spanning humanities and physical and social sciences, and integrating materials, design, engineering and social science concepts and methods. Our research work embodies true elements of radical design in a way that enriches our health and wellbeing and supports a healthy ecosystem.

Human-Centered Design

Human-centered design (HCD) provides a structured yet flexible approach to problem solving that puts the people who will ultimately benefit from a solution at the center of the design process. It is a powerful and practical tool to enhance community-based participatory research, implementation research, and medical product innovation.

Investigators are using HCD at Pitt to co-create research questions and co-design studies, treatments, interventions, and technology with the community members, patients, and participants who will be most impacted by their research.

In all design efforts we support, the HCD team at CTSI strives to incorporate the principles of design justice to promote accessibility and equity in the design process.

The CTSI Human-Centered Design team is certified through the LUMA Institute to practice, facilitate, and teach HCD. We provide:

- Methods Consultation and Coaching: Want to use HCD in your research but don’t know where to begin? Reach out to our team to get feedback and tips on how to incorporate HCD frameworks and choose methods that best fit your research project.

- Facilitation Consultation and Coaching: Already planning to incorporate HCD in your research but looking for guidance leading design sessions? We can provide consultations and coaching on adapting methods for in-person or virtual sessions, creating agendas and templates, and ensuring accessibility and equity during facilitation.

You can request these services by filling out the intake form below, just select “Human-Centered Design Consultation/Training” and let us know how we can help!

CTSI offers Human-Centered Design Foundations for Health Research Certification training for research teams. Researchers who have completed HCD training have found it highly beneficial , and report using HCD to refine interventions, uncover barriers to implementation, write innovative grants and manuscripts, and collect critical input from team members and community partners.

Pitt faculty and staff doing health research can take advantage of this valuable professional development opportunity to enhance their research. Register or join our waitlist for an upcoming training here:

You can find publicly available HCD toolkits and resources and over 100 HCD health research journal articles in our SharePoint repository.

Assistant Director, Human-Centered Design E-mail: [email protected]

Human-Centered Design Facilitator E-mail: [email protected]

IHCD believes that there is an urgent need to gather data about what works and what fails for people at the edges of the spectrum of ability, age, and culture. IHCD invests in contextual inquiry research with real people interacting with real physical or digital environments. We have recruited a base of over 300 people with physical, sensory, or brain-based conditions who vary in age from late teens to late 80s and culturally diverse. And we have extensive experience recruiting user/experts in other parts of the nation and the world. As a measure of our respect for the expertise of their lived experience, each user/expert is paid for their time.

A primary user/expert personally lives with one or more functional limitations.

A secondary user/expert is a friend, spouse, family member, service provider, therapist, teacher, or anyone who has extensive experience sharing life with primary user/experts and paying close attention to the interface with their environments.

“IHCD’s User Expert Lab has helped to enrich our designs—both physical and digital. Throughout recent redesigns of several subway stations as well as the complete rebuild of mbta.com, the feedback we received for the lab and its users helped to ensure we were designing with the diversity of our customers’ needs in mind. As a result we have found ourselves focused more on user experience than just mere compliance.” - Laura Brelsford, Assistant GM for Accessibility, MBTA

New England ADA Center Research

IHCD’s New England ADA Center releases startling findings about the true nature of disability by region, state, and city. Read all the findings here.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The Application of Human-Centered Design Approaches in Health Research and Innovation: A Narrative Review of Current Practices

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Primary and Community Care, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands.

- PMID: 34874893

- PMCID: PMC8691403

- DOI: 10.2196/28102

Background: Human-centered design (HCD) approaches to health care strive to support the development of innovative, effective, and person-centered solutions for health care. Although their use is increasing, there is no integral overview describing the details of HCD methods in health innovations.

Objective: This review aims to explore the current practices of HCD approaches for the development of health innovations, with the aim of providing an overview of the applied methods for participatory and HCD processes and highlighting their shortcomings for further research.

Methods: A narrative review of health research was conducted based on systematic electronic searches in the PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts (2000-2020) databases using keywords related to human-centered design, design thinking (DT), and user-centered design (UCD). Abstracts and full-text articles were screened by 2 reviewers independently based on predefined inclusion criteria. Data extraction focused on the methodology used throughout the research process, the choice of methods in different phases of the innovation cycle, and the level of engagement of end users.

Results: This review summarizes the application of HCD practices across various areas of health innovation. All approaches prioritized the user's needs and the participatory and iterative nature of the design process. The design processes comprised several design cycles during which multiple qualitative and quantitative methods were used in combination with specific design methods. HCD- and DT-based research primarily targeted understanding the research context and defining the problem, whereas UCD-based work focused mainly on the direct generation of solutions. Although UCD approaches involved end users primarily as testers and informants, HCD and DT approaches involved end users most often as design partners.

Conclusions: We have provided an overview of the currently applied methodologies and HCD guidelines to assist health care professionals and design researchers in their methodological choices. HCD-based techniques are challenging to evaluate using traditional biomedical research methods. Previously proposed reporting guidelines are a step forward but would require a level of detail that is incompatible with the current publishing landscape. Hence, further development is needed in this area. Special focus should be placed on the congruence between the chosen methods, design strategy, and achievable outcomes. Furthermore, power dimensions, agency, and intersectionality need to be considered in co-design sessions with multiple stakeholders, especially when including vulnerable groups.

Keywords: design thinking; design-based research; human-centered design; methodology; mobile phone; review; user-centered design.

©Irene Göttgens, Sabine Oertelt-Prigione. Originally published in JMIR mHealth and uHealth (https://mhealth.jmir.org), 06.12.2021.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for…

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart of the screening…

Illustration of human-centered design processes.…

Illustration of human-centered design processes. HCD: human-centered design; HPI: Hasso Plattner Institute; UCD:…

Levels of end user involvement…

Levels of end user involvement during human-centered design processes.

Similar articles

- Beyond the black stump: rapid reviews of health research issues affecting regional, rural and remote Australia. Osborne SR, Alston LV, Bolton KA, Whelan J, Reeve E, Wong Shee A, Browne J, Walker T, Versace VL, Allender S, Nichols M, Backholer K, Goodwin N, Lewis S, Dalton H, Prael G, Curtin M, Brooks R, Verdon S, Crockett J, Hodgins G, Walsh S, Lyle DM, Thompson SC, Browne LJ, Knight S, Pit SW, Jones M, Gillam MH, Leach MJ, Gonzalez-Chica DA, Muyambi K, Eshetie T, Tran K, May E, Lieschke G, Parker V, Smith A, Hayes C, Dunlop AJ, Rajappa H, White R, Oakley P, Holliday S. Osborne SR, et al. Med J Aust. 2020 Dec;213 Suppl 11:S3-S32.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50881. Med J Aust. 2020. PMID: 33314144

- The future of Cochrane Neonatal. Soll RF, Ovelman C, McGuire W. Soll RF, et al. Early Hum Dev. 2020 Nov;150:105191. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105191. Epub 2020 Sep 12. Early Hum Dev. 2020. PMID: 33036834

- Human-Centered Design of Mobile Health Apps for Older Adults: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Nimmanterdwong Z, Boonviriya S, Tangkijvanich P. Nimmanterdwong Z, et al. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022 Jan 14;10(1):e29512. doi: 10.2196/29512. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022. PMID: 35029535 Free PMC article. Review.

- Human-Centered Design Lessons for Implementation Science: Improving the Implementation of a Patient-Centered Care Intervention. Beres LK, Simbeza S, Holmes CB, Mwamba C, Mukamba N, Sharma A, Munamunungu V, Mwachande M, Sikombe K, Bolton Moore C, Mody A, Koyuncu A, Christopoulos K, Jere L, Pry J, Ehrenkranz PD, Budden A, Geng E, Sikazwe I. Beres LK, et al. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019 Dec;82 Suppl 3(3):S230-S243. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002216. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019. PMID: 31764259 Free PMC article. Review.

- Toward Inclusive Approaches in the Design, Development, and Implementation of eHealth in the Intellectual Disability Sector: Scoping Review. van Calis JFE, Bevelander KE, van der Cruijsen AWC, Leusink GL, Naaldenberg J. van Calis JFE, et al. J Med Internet Res. 2023 May 30;25:e45819. doi: 10.2196/45819. J Med Internet Res. 2023. PMID: 37252756 Free PMC article. Review.

- Co-designing Entrustable Professional Activities in General Practitioner's training: a participatory research study. Andreou V, Peters S, Eggermont J, Schoenmakers B. Andreou V, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2024 May 17;24(1):549. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-05530-y. BMC Med Educ. 2024. PMID: 38760773 Free PMC article.

- Weaving community-based participatory research and co-design to improve opioid use treatments and services for youth, caregivers, and service providers. Turuba R, Katan C, Marchand K, Brasset C, Ewert A, Tallon C, Fairbank J, Mathias S, Barbic S. Turuba R, et al. PLoS One. 2024 Apr 18;19(4):e0297532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0297532. eCollection 2024. PLoS One. 2024. PMID: 38635804 Free PMC article.

- Exploring the multi-level impacts of a youth-led comprehensive sexuality education model in Madagascar using Human-centered Design methods. Baumann SE, Leeson L, Raonivololona M, Burke JG. Baumann SE, et al. PLoS One. 2024 Apr 10;19(4):e0297106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0297106. eCollection 2024. PLoS One. 2024. PMID: 38598416 Free PMC article.

- Attributes, Methods, and Frameworks Used to Evaluate Wearables and Their Companion mHealth Apps: Scoping Review. Moorthy P, Weinert L, Schüttler C, Svensson L, Sedlmayr B, Müller J, Nagel T. Moorthy P, et al. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2024 Apr 5;12:e52179. doi: 10.2196/52179. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2024. PMID: 38578671 Free PMC article. Review.

- Centering healthcare workers in digital health design: Usability and acceptability of two-way texting to improve retention in antiretroviral therapy in a public HIV clinic in Lilongwe, Malawi. Mureithi M, Ng'aari L, Wasunna B, Kiruthu-Kamamia C, Sande O, Chiwaya GD, Huwa J, Tweya H, Jafa K, Feldacker C. Mureithi M, et al. PLOS Digit Health. 2024 Apr 3;3(4):e0000480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000480. eCollection 2024 Apr. PLOS Digit Health. 2024. PMID: 38568904 Free PMC article.

- Lehnert T, Heider D, Leicht H, Heinrich S, Corrieri S, Luppa M, Riedel-Heller S, König HH. Review: health care utilization and costs of elderly persons with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care Res Rev. 2011 Aug 03;68(4):387–420. doi: 10.1177/1077558711399580.68/4/387 - DOI - PubMed

- McPhail S. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2016 Jul;Volume 9:143–56. doi: 10.2147/rmhp.s97248. - DOI - PMC - PubMed

- Matheson GO, Pacione C, Shultz RK, Klügl M. Leveraging human-centered design in chronic disease prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2015 Apr;48(4):472–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.014.S0749-3797(14)00618-7 - DOI - PubMed

- Chan K. A design thinking mindset beyond the public health model. World Med Health Policy. 2018;10(1):111–9. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.253. - DOI

- Vesely R. Applying 'design thinking' to health care organizations. Health Facil Manag. 2017 Mar;30(3):10–1. - PubMed

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- JMIR Publications

- PubMed Central

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Research Areas

Faculty, research associates, and students in the department of Human Centered Design & Engineering advance the study and practice of design to improve cognition, behavior, engagement, or participation among individuals, groups, organizations, and communities of people.

Our approaches are fundamentally interdisciplinary and sociotechnical : we draw on a wide range of disciplinary traditions as we investigate the interaction of people's practices and meanings with technology.

Our department's research and teaching focus on six interrelated areas of study:

Influencing Behavior, Thinking, and Awareness

Design for emergent collaborations and organizations, low resource and underserved populations, material and embodied technologies, data science and data visualization, learning in professional and technical environments.

Faculty and students work collaboratively across many of the areas listed above. Students do not formally identify themselves as belonging to a particular research area and all graduating students receive engineering degrees in Human Centered Design & Engineering, not a particular area of study. While the HCDE researchers listed in each area below emphasize certain areas of study in their teaching and research, all faculty have additional areas of expertise not listed here.

As designers, we have the ability to create interventions that support or prompt changes in people's everyday lives, ideally for the better. We study how interventions affect people's behavior, thinking, or awareness. In addition, we design and assess new tools for making these changes. Focus areas include health and wellness, leisure, education, civic engagement, politics, social influence, persuasive technology, behavior change, reflection and mindfulness, awareness, incentives, and motivation.

|

|

|

We study and build digital technologies that people use to coordinate, collaborate, and interact in other ways. Our work typically focuses on emerging uses, practices, capacities, and organizational arrangements associated with collaborative technologies. We understand, influence, design, implement, and assess sociotechnical systems. Our research spans multiple contexts such as decision making, leisure, work, volunteerism, creativity, and innovation and domains such as crisis informatics, maritime operations, collaborative text production, and infrastructure studies.

|

|

|

We design and evaluate technologies for resource-constrained environments and deploy those technologies to support vulnerable populations. Our work is motivated by a commitment to ensuring the world enjoys the benefits of diverse technological solutions that can serve multiple populations. Areas of research include low-resource environments, high-risk and safety-critical environments, complex systems, crisis informatics, disaster and humanitarian response, humanitarian relief, information and communication technologies for development, and human-computer interaction for development.

|

|

|

We conduct research on the material and embodied technologies that shape emerging sites and process of daily life, from home energy monitoring to 3D printing and technology repair. We are interested in the overlap and collision of atoms and bits, looking at how the merging of craft and digital fabrication technologies condition our social worlds. We look at a range of platforms and form factors, and we are especially interested in how computing extends, resists, and transforms other technologies as well as social relationships, institutions, and communities. Areas of research include cultures of making, craft and repair, physical computing, open source hardware, digital fabrication, infrastructure studies, and science and technology studies.

|

|

|

We focus on the design, implementation, and evaluation of human-centered systems and techniques, such as visual analytics, in support of collaborative activities in environments that generate and require very large and complex data sets.

We focus on learning, with an emphasis on professional and technical activities. This work occurs across areas such as professional development and identity, translation of knowledge into action, expertise in problem framing, representation of design contexts, digital interfaces, reflection, engineering learning, design learning, language learning, and learning from text.

|

|

|

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Community-Based Participatory Research and Human-Centered Design Principles to Advance Hearing Health Equity

Nicole marrone.

1 Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

Carrie Nieman

2 Department of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

3 Johns Hopkins Cochlear Center for Hearing & Public Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD

Inclusive and equitable research is an ethical imperative. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) as well as human-centered design are approaches that center partnership between community members and academic researchers. Together, academic-community research teams iteratively study community priorities, collaboratively develop ethical study designs, and co-create innovations that are accessible and meaningful to the community partners while advancing science. The foundation of the CBPR approach is reliant on its core principles of equity, co-learning, shared power in decision-making, reciprocity, and mutual benefit. While the CBPR approach has been used extensively in public health and other areas of healthcare research, the approach is relatively new to audiology, otolaryngology, and hearing health research. Recent applications of CBPR have been framed broadly within the theoretical positions of the socio-ecological model for a systems-level approach to community-engaged research and the Health Services Utilization model within health services and disparities research using CBPR. Utilizing human-centered design strategies can work in tandem with a CBPR approach to engage a wide range of people in the research process and move toward the development of innovative yet feasible solutions. Leveraging the principles of CBPR is an intricate and dynamic process, and may not be a fit for some topics, some researchers’ skillsets, and may be beyond some projects’ resources. When implemented skillfully and authentically, CBPR can be of benefit by elevating and empowering community voices and cultural perspectives historically marginalized in society and underrepresented within research. The purpose of the current article is to advance an understanding of the CBPR approach, along with principles from human-centered design, in the context of research aimed to advance equity and access in hearing healthcare. The literature is reviewed to provide an introduction for auditory scientists to the CBPR approach and human-centered design, including discussion of the underlying principles of CBPR and where it fits along a community-engaged continuum, theoretical and evaluation frameworks, as well as applications within auditory research. With a focus on health equity, this review of CBPR in the study of hearing healthcare emphasizes how this approach to research can help to advance inclusion, diversity, and access to innovation.

Health equity is critically important within hearing healthcare and auditory research. Central to the Healthy People national public health goals in the U.S. is the overarching goal of eliminating health disparities to achieve health equity across the population ( U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d. ). Improving the inclusion, diversity, equity, and access in hearing healthcare involves parallel improvements in the research processes. There have also been recent national and global calls for increasing accessible and affordable hearing healthcare to eliminate disparities in access to care ( National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016 ; World Health Organization, 2021 ).

A high proportion of the growing aging and diverse population in the U.S. is living with untreated or poorly managed hearing loss ( Arnold et al., 2019 ; Nieman et al., 2016 ; Reed et al., 2020). While the under-diagnosis and under-treatment of hearing loss in the general population is itself poorly understood, even less is known about the accessibility of hearing healthcare among diverse populations, those with low socioeconomic position, and those living in rural communities. In addition, there is limited representation of racial and ethnic minorities within the hearing healthcare workforce ( Council on Graduate Medical Education, 2016 ) and limited representation within auditory research study populations, as evidenced by a recent systematic review of clinical trials in the U.S. on hearing loss interventions for adults ( Pittman et al., 2021 ).

Further, bias may be introduced if the effects of hearing loss on communication, healthcare utilization, and other outcomes are assumed not to be mediated by culture, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, as well as other forms of sociocultural identity such as gender, disability, and language. In other areas of health research, this is referred to as the risk of taking a “monocultural view” ( Kagawa-Singer et al., 2015 ). Specifically, this refers to ignoring the potential explanatory power of multidimensional aspects of culture, and the complexities of the social determinants of health.

Community-engaged and participatory research has had a strong role in improving equity and inclusion throughout public health research ( Viswanathan et al., 2004 ), with emerging use in hearing healthcare research. Community-based participatory research, or CBPR, is an approach that involves a key partnership between researchers and the community. Benefits of a participatory approach include the identification of relevant and culturally appropriate research questions, enhanced data collection and interpretation, and facilitating the translation of research findings into action and social change ( Wallerstein & Duran, 2010 ; Viswanathan et al., 2004 ). Within intervention research, the CBPR approach strengthens both community capacity and community acceptability of the intervention and research study design, leads to practical and feasible research protocols, informs culturally responsive research practices, enhances recruitment and retention strategies, and yields the ability to address health problems resulting from complex interactions of individual, social, cultural, and political factors ( Hacker et al., 2012 ; Jagosh et al., 2012 ; Macaulay et al., 2011 ). Taking this approach within hearing healthcare research is at the intersection of disability and issues related to racial/ethnic diversity and systemic racism (Ellis et al., 2020).

Recently a scoping meta-review of community-engaged research and CBPR was conducted ( Ortiz et al., 2020 ). Over 100 reviews in the literature have been published to date within other disciplines including nursing, psychology, public health, and many others, with often interdisciplinary representations of CBPR and participatory research in the literature. However, none of these prior literature reviews had a focus on auditory research or hearing healthcare. The current review aims to address this gap in the literature.

The purpose of this article is to provide an introduction to CBPR and human-centered design principles to auditory scientists and describe how these approaches can be applied within auditory research to address issues of inclusion, diversity, equity, and access, ultimately contributing to the elimination of disparities in access to hearing healthcare. In this article, our goal is to advance an understanding of what it means to take a CBPR approach in the context of research aimed to advance equity and access to hearing healthcare. Here we propose that CBPR and human-centered design have potential to offer new perspectives from a broader range of stakeholders, including through principled efforts for greater engagement of, by, and for communities historically marginalized by systemic racism and other forms of oppression. Drawing from the literature, the practices involved in CBPR and its underlying principles, along with human-centered design, will be reviewed. Theoretical and evaluation frameworks, applications within hearing healthcare research, and challenges will also be discussed.

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR)

Viswanathan et al. (2004) reported on a review of CBPR sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The purpose of the review was to gather evidence to date in order to begin to develop a more unifying definition of the CBPR approach. Their consensus definition of CBPR describes it as:

a collaborative research approach that is designed to ensure and establish structures for participation by communities affected by the issue being studied, representatives of organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process to improve health and well-being through taking action, including social change. (pp. 3)

Principles of CBPR

Key principles expanding upon this definition included that CBPR involves co-learning and reciprocity by all partners, shared decision-making power within the academic-community partnership, and mutual ownership of the research process and its outcomes ( Viswanathan et al., 2004 ). An often-cited summary of eight principles of CBPR is attributed to Israel et al. (1998) . As summarized in Table 1 , these principles of CBPR are found within equitable partnerships between academic researchers and community representatives:

Comparisons between traditional research and Community-Based Participatory Research across the research process (adapted from Horowitz, Robinson, & Seifer, 2009 ).

| Stage of Research | Traditional Auditory Laboratory or Clinical Research | Community Based Participatory Research |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals, a community or population as a passive subject of study. | Community partners involved as equal members of the research team, recognized and respected in the research process including to set the research agenda. | |

| Based on what is known in scientific literature. | Collaboration with the community, based on an understanding of local values and challenges in combination with the science. | |

| Researchers gain skills and knowledge. | Build on strengths in the community and addresses challenges to help build community capacity as well as researcher capacity. | |

| Typically lacking participation from the community. | Decisions are reviewed iteratively, taking time for feedback from Community-Based Participatory Research members. | |

| Researchers control data and decide how and where to share findings. | Researchers and community partners decide together how to disseminate including peer-reviewed publications as well as communication to community-relevant audiences. |

- Community as a unit of identity;

- Taking a strengths-based approach building on the community’s resources;

- Equitable and collaborative partnership in all phases of the research;

- Mutually benefits all partners;

- Co-learning process that addresses health equity through capacity building and empowerment;

- Cyclical and iterative process;

- Considers health from positive and ecological perspectives;

- Collaborative dissemination of findings within and beyond the community of study.

Rather than a specific research method or set of methods per se, CBPR is an ‘approach,’ or an ‘orientation’ to research ( Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995 ). In fact, many different types of study designs have been conducted within a CBPR approach across different disciplines, including randomized control trials and quasi-experimental studies, surveys, and qualitative studies ( Clark & Ventres, 2016 ; De Las Nueces et al., 2012 ; Salimi et al., 2012 ). Taking a CBPR approach can include quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods data collection. However, as we will discuss further in this review, CBPR is emergent in auditory research.

By describing CBPR as an approach or orientation to the research, it is often explained that its underlying principles differ in part from those of traditional laboratory or clinical research studies. An extensive comparison between traditional research and CBPR was carried out by Horowitz et al. (2009) and has been adapted in Table 1 . Among the important contrasts between traditional research and CBPR is the degree of community involvement at all stages of the research process, including identifying the research problem, study design and implementation, and dissemination of findings. Taking a CBPR approach will not be a fit for all research topics, researchers’ skillsets, and may be beyond some projects’ resources. On a practical level, this is exemplified within CBPR academic-community partnerships as equitably sharing project funding, responsibility, and decision-making power. This equitable partnership between researchers and the community of study not only improves external validity, it can lead to action and builds both community and research capacity that can have impact beyond the study itself ( Oetzel et al., 2018 ).

History of CBPR

The history of CBPR as a research approach stems from the social sciences, psychology, and education fields. There are considered to be two major sources of the history of CBPR, the Global Northern and Global Southern traditions, based on their geographic places of origin ( Wallerstein & Duran, 2017 ). The Northern tradition stems from the work of Lewin, a sociology researcher in the 1930s-1940s. The Southern tradition is attributed in part to the work of Brazilian educator and philosopher Paolo Freire, who advocated community empowerment and experiential learning within education research in the 1970s. Wallerstein (2021) explains that the more recent definition of CBPR reflects both traditions. Specifically, this approach includes the iterative research processes proposed by Lewin and others, giving honor to community knowledge and strengths, as well as the emancipatory, social justice focus of the Southern tradition based on the work of Freire and others. Reflecting its growing importance within health research and reducing health disparities, CBPR is now a core area of education in the discipline of public health along with other participatory health research approaches ( Wallerstein & Duran, 2017 ).

Research taking a CBPR approach has been documented globally to address a variety of health issues as well as social justice in education and social sciences research. For example, researchers in South Africa used CBPR principles to establish community priorities around cervical cancer screenings ( Mosavel et al., 2005 ). Researchers in that study used focus groups, interviews, and field visits, to engage community members’ feedback and establish partnerships that helped develop a cervical cancer prevention program. The result was a program that emphasized health and wellbeing, rather than pathology ( Mosavel et al., 2005 ). Additionally, the China Jintan Child Cohort Study used a CBPR approach to understand the impact of malnutrition and environmental toxins on the health of children ( Liu et al., 2011 ). In that study, researchers engaged community partners, including parents and teachers, to develop the research protocol, conduct field work, as well as communicate results and engage the public around the topic at health education fairs and poster presentations in local schools and hospitals. The authors conclude that a CBPR approach helped ensure that the topic was relevant to the community and that the protocol was acceptable, and the process helped establish a connection with the community.

CBPR Along the Continuum of Power Sharing in Research

Broadly, CBPR fits within a continuum of power sharing and community engagement in research ( Key et al., 2019 ; Wallerstein et al., 2019 ). The continuum extends on one end from fully investigator-driven research to the other end with fully community-driven research ( Figure 1 ). The continuum is not only based on who is driving the research question and direction but who and how the power is distributed between the investigator and study team and community representatives. Along this continuum, CBPR is situated towards the highest degree of community involvement and power sharing in research. An element that distinguishes CBPR from other research approaches along this continuum is having community involvement at all stages of the research process ( Wallerstein & Duran, 2017 ). Specifically, this can include community involvement from the earliest stages of assessing and identifying community needs, strengths, and resources; formulating a research question; designing the research study; data collection, analysis, interpretation; to the later stages of dissemination and identifying new directions for future research. This shared power dynamic is unique to CBPR. These characteristics separate CBPR from the typical approach to investigator-driven study design, as CBPR promotes empowerment and equity by sharing power in all phases of the research with the partnering community. This approach requires having a trusting relationship between academic and community partners, ongoing dialogue and co-learning, and all the while negotiating and balancing the interests of partners ( Resnik & Kennedy, 2010 ; Mohammed et al., 2012 ). See Figure 2 for methodological approaches to establishing longstanding successful CBPR partnerships.

Comparisons between traditional research and CBPR across the research process.

Methodological approaches to establishing longstanding successful CBPR partnerships (see: Examining Community-Institutional Partnerships for Prevention Research Group, 2006 ; Shalowitz et al., 2009 .; Coombe et al., 2020.)

While CBPR is often recommended, or even solicited by funding agencies, as an approach to engage diverse and vulnerable communities in research, it should not be viewed only as a means to enroll greater numbers of people of color or engage marginalized communities in the research. The CBPR approach emphasizes equitable partnership and reciprocity with communities to share power within the conduct of the research study itself ( Examining Community-Institutional Partnerships for Prevention Research Group, 2006 ; Shalowitz et al., 2009 ). Thus, the researcher who takes a CBPR approach recognizes, cultivates, and encourages far greater engagement of community members within the design and conduct of the research study, well beyond the recruitment of participants alone. When investigators recognize the importance of contributions of the community at all stages of the research process, this community engagement enables prioritization and value-shifting that honors the community’s needs and strengths. Further, engagement with community partners throughout the entire research process supports a mechanism for accountability so that the research fulfills its intended purpose, while drawing upon the strengths of the community without marginalization or exploitation to be relevant and effective for the communities served.

To expand the CBPR approach within auditory research, we will need both action from individual investigators and systemic supports. It is important for authors/researchers to appropriately represent their work and how it is positioned within the continuum of community-engaged research (see also Figure 1 ). Additionally, one must not misrepresent research that is conducted within a community setting as CBPR by staying transparent in reporting about the degree to which the study is truly CBPR. Likewise, acknowledging a continuum of community engagement and power-sharing within research, future readers and reviewers of grant proposals and manuscripts within auditory research may do well to watch for indicators of the quality of true CBPR implementation and not mistake community-placed recruitment for CBPR.