“Body Ritual among the Nacirema” by Horace Miner

Most cultures exhibit a particular configuration or style. A single value or pattern of perceiving the world often leaves its stamp on several institutions in the society. Examples are “machismo” in Spanish-influenced cultures, “face” in Japanese culture, and “pollution by females” in some highland New Guinea cultures. Here Horace Miner demonstrates that “attitudes about the body” have a pervasive influence on many institutions in Nacirema society.

The anthropologist has become so familiar with the diversity of ways in which different people behave in similar situations that he is not apt to be surprised by even the most exotic customs. In fact, if all of the logically possible combinations of behavior have not been found somewhere in the world, he is apt to suspect that they must be present in some yet undescribed tribe. The point has, in fact, been expressed with respect to clan organization by Murdock [1] . In this light, the magical beliefs and practices of the Nacirema present such unusual aspects that it seems desirable to describe them as an example of the extremes to which human behavior can go.

Professor Linton [2] first brought the ritual of the Nacirema to the attention of anthropologists twenty years ago, but the culture of this people is still very poorly understood. They are a North American group living in the territory between the Canadian Cree, the Yaqui and Tarahumare of Mexico, and the Carib and Arawak of the Antilles. Little is known of their origin, although tradition states that they came from the east. According to Nacirema mythology, their nation was originated by a culture hero, Notgnihsaw, who is otherwise known for two great feats of strength—the throwing of a piece of wampum across the river Pa-To-Mac and the chopping down of a cherry tree in which the Spirit of Truth resided.

Nacirema culture is characterized by a highly developed market economy which has evolved in a rich natural habitat. While much of the people’s time is devoted to economic pursuits, a large part of the fruits of these labors and a considerable portion of the day are spent in ritual activity. The focus of this activity is the human body, the appearance and health of which loom as a dominant concern in the ethos of the people. While such a concern is certainly not unusual, its ceremonial aspects and associated philosophy are unique.

The fundamental belief underlying the whole system appears to be that the human body is ugly and that its natural tendency is to debility and disease. Incarcerated in such a body, man’s only hope is to avert these characteristics through the use of ritual and ceremony. Every household has one or more shrines devoted to this purpose. The more powerful individuals in the society have several shrines in their houses and, in fact, the opulence of a house is often referred to in terms of the number of such ritual centers it possesses. Most houses are of wattle and daub construction, but the shrine rooms of the more wealthy are walled with stone. Poorer families imitate the rich by applying pottery plaques to their shrine walls.

While each family has at least one such shrine, the rituals associated with it are not family ceremonies but are private and secret. The rites are normally only discussed with children, and then only during the period when they are being initiated into these mysteries. I was able, however, to establish sufficient rapport with the natives to examine these shrines and to have the rituals described to me.

The focal point of the shrine is a box or chest which is built into the wall. In this chest are kept the many charms and magical potions without which no native believes he could live. These preparations are secured from a variety of specialized practitioners. The most powerful of these are the medicine men, whose assistance must be rewarded with substantial gifts. However, the medicine men do not provide the curative potions for their clients, but decide what the ingredients should be and then write them down in an ancient and secret language. This writing is understood only by the medicine men and by the herbalists who, for another gift, provide the required charm.

The charm is not disposed of after it has served its purpose, but is placed in the charmbox of the household shrine. As these magical materials are specific for certain ills, and the real or imagined maladies of the people are many, the charm-box is usually full to overflowing. The magical packets are so numerous that people forget what their purposes were and fear to use them again. While the natives are very vague on this point, we can only assume that the idea in retaining all the old magical materials is that their presence in the charm-box, before which the body rituals are conducted, will in some way protect the worshiper.

Beneath the charm-box is a small font. Each day every member of the family, in succession, enters the shrine room, bows his head before the charm-box, mingles different sorts of holy water in the font, and proceeds with a brief rite of ablution [3] . The holy waters are secured from the Water Temple of the community, where the priests conduct elaborate ceremonies to make the liquid ritually pure.

In the hierarchy of magical practitioners, and below the medicine men in prestige, are specialists whose designation is best translated as “holy-mouth-men.” The Nacirema have an almost pathological horror of and fascination with the mouth, the condition of which is believed to have a supernatural influence on all social relationships. Were it not for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that their teeth would fall out, their gums bleed, their jaws shrink, their friends desert them, and their lovers reject them. They also believe that a strong relationship exists between oral and moral characteristics. For example, there is a ritual ablution of the mouth for children which is supposed to improve their moral fiber.

The daily body ritual performed by everyone includes a mouth-rite. Despite the fact that these people are so punctilious [4] about care of the mouth, this rite involves a practice which strikes the uninitiated stranger as revolting. It was reported to me that the ritual consists of inserting a small bundle of hog hairs into the mouth, along with certain magical powders, and then moving the bundle in a highly formalized series of gestures. [5]

In addition to the private mouth-rite, the people seek out a holy-mouth-man once or twice a year. These practitioners have an impressive set of paraphernalia, consisting of a variety of augers, awls, probes, and prods. The use of these items in the exorcism of the evils of the mouth involves almost unbelievable ritual torture of the client. The holy-mouth-man opens the client’s mouth and, using the above mentioned tools, enlarges any holes which decay may have created in the teeth. Magical materials are put into these holes. If there are no naturally occurring holes in the teeth, large sections of one or more teeth are gouged out so that the supernatural substance can be applied. In the client’s view, the purpose of these ministrations [6] is to arrest decay and to draw friends. The extremely sacred and traditional character of the rite is evident in the fact that the natives return to the holy-mouth-men year after year, despite the fact that their teeth continue to decay.

It is to be hoped that, when a thorough study of the Nacirema is made, there will be careful inquiry into the personality structure of these people. One has but to watch the gleam in the eye of a holy-mouth-man, as he jabs an awl into an exposed nerve, to suspect that a certain amount of sadism is involved. If this can be established, a very interesting pattern emerges, for most of the population shows definite masochistic tendencies. It was to these that Professor Linton referred in discussing a distinctive part of the daily body ritual which is performed only by men. This part of the rite includes scraping and lacerating the surface of the face with a sharp instrument. Special women’s rites are performed only four times during each lunar month, but what they lack in frequency is made up in barbarity. As part of this ceremony, women bake their heads in small ovens for about an hour. The theoretically interesting point is that what seems to be a preponderantly masochistic people have developed sadistic specialists.

The medicine men have an imposing temple, or latipso , in every community of any size. The more elaborate ceremonies required to treat very sick patients can only be performed at this temple. These ceremonies involve not only the thaumaturge [7] but a permanent group of vestal maidens who move sedately about the temple chambers in distinctive costume and headdress.

The latipso ceremonies are so harsh that it is phenomenal that a fair proportion of the really sick natives who enter the temple ever recover. Small children whose indoctrination is still incomplete have been known to resist attempts to take them to the temple because “that is where you go to die.” Despite this fact, sick adults are not only willing but eager to undergo the protracted ritual purification, if they can afford to do so. No matter how ill the supplicant or how grave the emergency, the guardians of many temples will not admit a client if he cannot give a rich gift to the custodian. Even after one has gained and survived the ceremonies, the guardians will not permit the neophyte to leave until he makes still another gift.

The supplicant entering the temple is first stripped of all his or her clothes. In everyday life the Nacirema avoids exposure of his body and its natural functions. Bathing and excretory acts are performed only in the secrecy of the household shrine, where they are ritualized as part of the body-rites. Psychological shock results from the fact that body secrecy is suddenly lost upon entry into the latipso . A man, whose own wife has never seen him in an excretory act, suddenly finds himself naked and assisted by a vestal maiden while he performs his natural functions into a sacred vessel. This sort of ceremonial treatment is necessitated by the fact that the excreta are used by a diviner to ascertain the course and nature of the client’s sickness. Female clients, on the other hand, find their naked bodies are subjected to the scrutiny, manipulation and prodding of the medicine men.

Few supplicants in the temple are well enough to do anything but lie on their hard beds. The daily ceremonies, like the rites of the holy-mouth-men, involve discomfort and torture. With ritual precision, the vestals awaken their miserable charges each dawn and roll them about on their beds of pain while performing ablutions, in the formal movements of which the maidens are highly trained. At other times they insert magic wands in the supplicant’s mouth or force him to eat substances which are supposed to be healing. From time to time the medicine men come to their clients and jab magically treated needles into their flesh. The fact that these temple ceremonies may not cure, and may even kill the neophyte, in no way decreases the people’s faith in the medicine men.

There remains one other kind of practitioner, known as a “listener.” This witchdoctor has the power to exorcise the devils that lodge in the heads of people who have been bewitched. The Nacirema believe that parents bewitch their own children. Mothers are particularly suspected of putting a curse on children while teaching them the secret body rituals. The counter-magic of the witchdoctor is unusual in its lack of ritual. The patient simply tells the “listener” all his troubles and fears, beginning with the earliest difficulties he can remember. The memory displayed by the Nacirema in these exorcism sessions is truly remarkable. It is not uncommon for the patient to bemoan the rejection he felt upon being weaned as a babe, and a few individuals even see their troubles going back to the traumatic effects of their own birth.

In conclusion, mention must be made of certain practices which have their base in native esthetics but which depend upon the pervasive aversion to the natural body and its functions. There are ritual fasts to make fat people thin and ceremonial feasts to make thin people fat. Still other rites are used to make women’s breasts larger if they are small, and smaller if they are large. General dissatisfaction with breast shape is symbolized in the fact that the ideal form is virtually outside the range of human variation. A few women afflicted with almost inhuman hyper-mammary development are so idolized that they make a handsome living by simply going from village to village and permitting the natives to stare at them for a fee.

Reference has already been made to the fact that excretory functions are ritualized, routinized, and relegated to secrecy. Natural reproductive functions are similarly distorted. Intercourse is taboo as a topic and scheduled as an act. Efforts are made to avoid pregnancy by the use of magical materials or by limiting intercourse to certain phases of the moon. Conception is actually very infrequent. When pregnant, women dress so as to hide their condition. Parturition takes place in secret, without friends or relatives to assist, and the majority of women do not nurse their infants.

Our review of the ritual life of the Nacirema has certainly shown them to be a magic-ridden people. It is hard to understand how they have managed to exist so long under the burdens which they have imposed upon themselves. But even such exotic customs as these take on real meaning when they are viewed with the insight provided by Malinowski [8] when he wrote:

Looking from far and above, from our high places of safety in the developed civilization, it is easy to see all the crudity and irrelevance of magic. But without its power and guidance early man could not have mastered his practical difficulties as he has done, nor could man have advanced to the higher stages of civilization.

Footnotes are added by Dowell as modified by Chase

- Murdock, George P. 1949. Social Structure . NY: The Macmillan Co., page 71. George Peter Murdock (1897-1996 [?]) is a famous ethnographer. ↵

- Linton, Ralph. 1936. The Study of Man . NY: D. Appleton-Century Co. page 326. Ralph Linton (1893-1953) is best known for studies of enculturation (maintaining that all culture is learned rather than inherited; the process by which a society's culture is transmitted from one generation to the next), claiming culture is humanity's "social heredity." ↵

- A washing or cleansing of the body or a part of the body. From the Latin abluere, to wash away ↵

- Marked by precise observance of the finer points of etiquette and formal conduct. ↵

- It is worthy of note that since Prof. Miner's original research was conducted, the Nacirema have almost universally abandoned the natural bristles of their private mouth-rite in favor of oil-based polymerized synthetics. Additionally, the powders associated with this ritual have generally been semi-liquefied. Other updates to the Nacirema culture shall be eschewed in this document for the sake of parsimony. ↵

- Tending to religious or other important functions ↵

- A miracle-worker. ↵

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. Magic, Science, and Religion . Glencoe: The Free Press, page 70. Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) is a famous cultural anthropologist best known for his argument that people everywhere share common biological and psychological needs and that the function of all cultural institutions is to fulfill such needs; the nature of the institution is determined by its function. ↵

- Body Ritual of the Nacirema. Authored by : Horace Miner. Located at : https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Body_Ritual_among_the_Nacirema . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Body Ritual Among the Nacirema Summary and Analysis

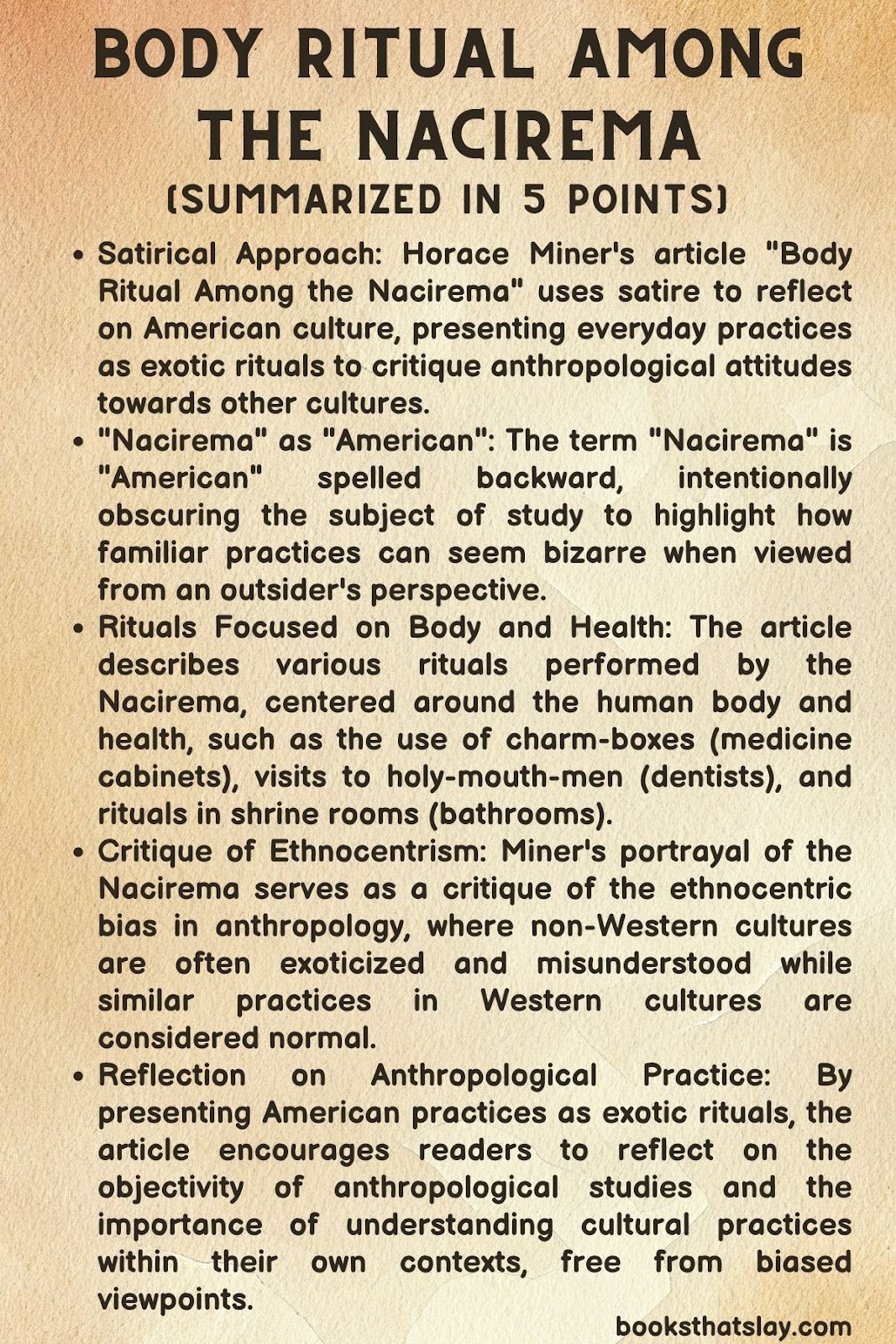

“Body Ritual Among the Nacirema” is a satirical article written by American anthropologist Horace Miner and published in 1956 in the journal “American Anthropologist”.

The piece uses a fictionalized account of American cultural practices to critique the anthropological approach to the study of other cultures, particularly the exoticization and misunderstanding of everyday practices.

Full Summary

The term “Nacirema” is “American” spelled backward, and the article describes the rituals of this “tribe” in a tone typically used by anthropologists to describe non-Western cultures.

The Nacirema are portrayed as a group obsessed with rituals around the human body, particularly its health and appearance.

Key elements of the article include:

- Shrine Rooms : Every household has one or more shrine rooms devoted to ritualistic practices, designed to improve the body’s appearance and health. These rooms contain charm-boxes filled with magical potions, a reference to medicine cabinets and pharmaceuticals.

- Holy-Mouth-Men : The Nacirema visit these practitioners regularly, who perform rituals involving the mouth. This is a portrayal of dentists and the cultural importance placed on oral hygiene.

- Listeners : These are special members of the society who listen to individuals’ problems and use magical techniques to influence the mental health of their clients, representing psychologists or psychiatrists.

- The Latipso Ceremony : In this ritual, people are brought to a temple (latipso spelled backward is hospital) where they undergo extreme and often painful experiences to treat severe physical or mental illnesses, representing hospitals and medical procedures.

- Body Rituals : The Nacirema are described as engaging in numerous body rituals throughout the day, such as scraping and lacerating the surface of the face with a sharp instrument, a satirical description of shaving or makeup application.

Miner’s article serves as a critique of anthropological practices and the Western perspective on “exotic” cultures.

By showing how familiar American practices can seem bizarre and irrational when described in the detached, academic tone often used by anthropologists, Miner emphasizes the importance of understanding and respecting other cultures without biased or ethnocentric viewpoints.

The article continues to be widely read and discussed for its clever inversion of the anthropological gaze and its challenge to ethnocentric thinking.

“Body Ritual Among the Nacirema” by Horace Miner offers a rich subject for analysis, particularly in its critique of anthropological methods and cultural ethnocentrism. Here’s a detailed analysis of the article:

Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism

- Inversion of the Anthropological Gaze : Miner’s article cleverly reverses the typical anthropological study, where Western anthropologists study non-Western cultures. By describing American practices using anthropological terms and an ‘outsider’ perspective, Miner illustrates how familiar behaviors can appear strange or illogical when observed without cultural context.

- Critique of Ethnocentrism : The article challenges readers to recognize their own ethnocentric biases. Ethnocentrism is the act of judging another culture solely by the values and standards of one’s own culture. By exoticizing the mundane aspects of American life, Miner highlights how ethnocentrism can lead to a misunderstanding or devaluing of other cultures.

- Cultural Relativism : This is the principle that an individual’s beliefs and activities should be understood in terms of their own culture. Miner’s satirical approach encourages readers to adopt a more culturally relativistic perspective, understanding practices within their cultural context rather than judging them by external standards.

Anthropological Writing and Representation

- Anthropological Language : Miner’s use of dense, academic language mimics the style of traditional anthropological literature, which can often seem detached and overly clinical. This stylistic choice underscores how the language used in anthropology can obscure understanding and empathy.

- Representation of the “Other” : The Nacirema are depicted as exotic and their rituals as bizarre, echoing how non-Western cultures have historically been portrayed in anthropological studies. This representation challenges the reader to consider how the portrayal of the “other” can be skewed by biases and a lack of cultural understanding.

Modern Consumer Culture and Health Practices

- Body Obsession : The Nacirema’s rituals reflect modern society’s obsession with physical appearance and health. These rituals, from daily hygiene to medical procedures, are a commentary on the lengths to which people go in pursuit of beauty and wellness.

- Medical and Psychological Practices : The portrayal of the “holy-mouth-men” and “listeners” critiques the medicalization and professionalization of health and wellness in modern society, highlighting how such practices, while normal to us, can seem peculiar from an external viewpoint.

Social Commentary

- Critique of American Culture : While the article is a critique of anthropological methods, it also serves as a subtle commentary on American culture’s peculiarities, especially its preoccupation with appearance, health, and wellness.

- Reflection on the Reader’s Perspective : The article often leads to an “aha” moment for readers when they realize that the Nacirema are Americans. This realization forces readers to reflect on their own cultural practices and the initial judgments they made about the Nacirema.

Final Thoughts

“Body Ritual Among the Nacirema” remains a seminal work in anthropology for its incisive critique of the field’s methods and its ability to make the familiar seem foreign.

Miner’s article urges anthropologists and readers alike to approach the study of other cultures with greater awareness of their own biases and with respect for the complexities and nuances of different ways of life.

Sharing is Caring!

A team of Editors at Books That Slay.

Passionate | Curious | Permanent Bibliophiles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Body Ritual among the Nacirema Expository Essay

Culture is the way of life of a social group. From the sociological aspect, culture has five key elements that well describe a people’s ways of thinking and action. The elements include beliefs, norms, values, symbols, and language. Beliefs are avowals that a social group hold to be true.

Symbols, on its aspect, are things that a particular group of people believes to carry specific meanings. From Horace Miner’s article, the Nacirema had shrines in all homes and special charm boxes on the walls of the shrines. In addition, there was a temple where medicine men could treat extremely sick patients. Other symbolic objects were prods, awl, cherry tree and other magical materials. Cultural relativism holds that civilization or way of life is not something complete, but it is relative with the context in which it is practiced.

This sociological concept has it that there is no right or wrong practices. The rightness or wrongness depends on a social group that practices it.

Therefore, an act that is unethical in one ethnic group can be ethical in another ethnic group. There is no way of life that is absolute in itself. For example, the people of Nacirema performed pathological horrors on their mouths a way of improving moral fibers, preventing teeth decay, and making them develop strong relationships with their friend. The context of right and wrong relies on a specific culture.

Ethnocentrism is the inclination of believing that the cultural practices of an ethnic group are extremely significant and comparison of other social group’s cultures is done with respect to the former. An ethnocentric person believes that his/her way of life is the best and goes on to judge other cultures relative to his/her own culture. The concept of ethnocentrism assists in distinguishing between one’s cultures from others. Lastly, qualitative research methodology is a research method that answers questions like ‘why’, ‘how’ and ‘what’.

Professor Linton’s research on the Body Ritual among the Nacirema qualifies to be qualitative in nature since it tries to answer the question why the Nacirema behaved the way they did in the past. The essay discusses the belief systems and practices of the Nacirema in light to the sociological aspects of culture, cultural relativism, and ethnocentrism. Moreover, it will expound on the qualitative research methodology as used in acquiring information about the Nacirema.

Anthropologists have come to unearth the culture of the Nacirema. First, this group believed that Notgnihsaw discovered the nation in which they lived. The group focuses their ritual activities on the human body where they believe that the body is ugly hence should be transformed through the rituals.

The shrine is an important symbol in among the Nacirema such that all families must have at least one. In the shrines, a chest is built on the wall to help in storing charms that people have used. The Nacirema believes that medicine men are the most powerful magical practitioners. In addition, the Nacirema conducts a holy-mouth rite at least once in a year. The entire process involves inserting magical materials using augers, prods, and probes.

The cultural relativism is evident in this context given that the process of gouging of teeth is painful, but the Nacirema continues to practice the act. Medicine men could prick the bodies of the sick using an awl. Moreover, the difficult situation involved in mouth rite reveals the ethnocentric nature of the community since they believe that the culture is the best and continues to use it on its people.

Moreover, the Nacirema strips sick people when they get into the temples for treatment. Notably, medicine men manipulate, scrutinize, and prod the bodies of female patients. Witch doctors had the power to exorcise the devils and curses that parents could have placed on their children. The Nacirema also practiced other rites where females with large or small breasts could change the size of their breasts. Markedly, those with extra hyperactive mammary developments could make money by displaying them to different villages.

The ethnocentrism concept is visible in the manner in which sick individuals continued to seek treatment from the temple even though the conditions that they were undergoing reduced their chances of living again. In the present world, treatment process is not intended to be ruthless and cruel and this practice among the Nacirema is barbaric in this context. Worst still, temple guardians could not admit any sick person before he/she pays rich gifts to the custodians.

This act was mandatory even if the patient was rich or poor. The Nacirema respected and followed these practices, as the people believed that they were the best in their context. Even though the Nacirema rituals on the body were crude, backward, and painful, the people did not complain of any mistreatment. They had strong beliefs in their cultures and had to respect them in order to minimize conflicts among themselves.

The qualitative research methodology has assisted anthropologists in unearthing the diverse practices of the Nacirema. For example, the articles has revealed why the Nacirema engaged in daily mouth rites, built shrines and charm boxes on their walls, did not dispose charms and why they continued to visit temples amidst the painful and embarrassing ordeals in the process.

The article also explains how the Nacirema conducts some rituals like the mouth rite, a patient’s treatment at the temples, and how families enter shrine rooms to mix different components of holy water. Evidently, the sociological aspect has revealed the diverse practices of the Nacirema in the context of what makes them respect the entire process.

- Comparison Between the Body Rituals in Nacirema and American Society

- “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema” by Horace Miner

- Anthropology and the Nacirema Group

- Cultural Revolution in China: Politically, Socially, and Economically

- Angelou Maya’s Presentation on the African Culture

- A Travel Into the Korean Culture: 2012 Korean Festival in Houston

- Traditional and Non-Traditional Culture

- Course Outcomes: Vietnamese Culture and Experiences

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, December 19). Body Ritual among the Nacirema. https://ivypanda.com/essays/body-ritual-among-the-nacirema/

"Body Ritual among the Nacirema." IvyPanda , 19 Dec. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/body-ritual-among-the-nacirema/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Body Ritual among the Nacirema'. 19 December.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Body Ritual among the Nacirema." December 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/body-ritual-among-the-nacirema/.

1. IvyPanda . "Body Ritual among the Nacirema." December 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/body-ritual-among-the-nacirema/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Body Ritual among the Nacirema." December 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/body-ritual-among-the-nacirema/.

The Long Life of the Nacirema

An article that turned an exoticizing anthropological lens on US citizens in 1956 began as an academic in-joke but turned into an indictment of the discipline.

In 1956, the journal American Anthropologist published a short paper by University of Michigan anthropologist Horace Miner titled “ Body Ritual Among the Nacirema ,” detailing the habits of this “North American group.” Among the “exotic customs” it explores are the use of household shrines containing charm-boxes filled with magical potions and visits to a “holy-mouth-man.”

It doesn’t take long for a reader of the paper to recognize the people in question—“Nacirema” is “American” spelled backward. The joke article spread quickly, with other journals publishing excerpts. Writing more than 50 years after its original publication , literature scholar Mark Burde notes that it remained among the most-downloaded anthropology papers.

Yet it was only through chance that the article was published to begin with. Miner initially submitted a version of it to a general-interest publication. In that context, Burde suggests, its satire would have appeared to be directed at the cultural conventions that fill such magazines with ads for breath mints and deodorant soap. He notes lines such as “were it not for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that…their friends [would] desert them.”

When that publication rejected the article, Miner instead submitted it to American Anthropologist. There, the outgoing editor-in-chief initially rejected it, but his successor, Walter Goldschmidt, eventually decided to publish it.

Burde writes that many readers have viewed the paper as a challenge to the basic functioning of anthropology, showing how academic outsiders misunderstand the cultures they claim to chronicle. Some have pointed in particular to the paper’s final paragraph. Here Miner questions how the Nacirema “have managed to exist so long under the burdens which they have imposed upon themselves” and then quotes a 1925 essay by anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski: “Looking from far and above, from our high places of safety in the developed civilization, it is easy to see all the crudity and irrelevance of magic. But without its power and guidance early man could not have mastered his practical difficulties as he has done, nor could man have advanced to the higher stages of civilization.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Many readers have suggested that this ending exposed Malinowski’s prejudices and, more generally, the judgment implicit in ethnographers’ identification of cultures as “primitive” or “civilized.” But Burde writes that this was likely not Miner’s intent since he had approvingly cited the same quotation in the past. Instead, he seems to have been more focused on encouraging readers to recognize the way seemingly exotic “far-away” cultures are thoroughly normal to their members.

In general, Burde argues, readers came to see the article as more subversive than Miner had originally intended. That was partly thanks to shifts in scholarship in the 1960s that drew attention to anthropologists as interested parties with their own subject positions and experiences rather than purely objective observers. Burde suggests that part of what has made the Nacirema a durable concept is the way it straddles the line between academic in-joke and radical critique, delivering “a Montaigneseque message in a Woody Allen-esque package.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- How the Universe Forges Stars from Cosmic Clouds

- The Vital Near-Magic of Fire-Eating Fungi

- The Long History of Live Animal Export

Haunted Soldiers in Mesopotamia

Recent posts.

- Capturing the Civil War

- Growing Guerrilla Warfare

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.2: “Body Ritual among the Nacirema” by Horace Miner

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 22420

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Most cultures exhibit a particular configuration or style. A single value or pattern of perceiving the world often leaves its stamp on several institutions in the society. Examples are “machismo” in Spanish-influenced cultures, “face” in Japanese culture, and “pollution by females” in some highland New Guinea cultures. Here Horace Miner demonstrates that “attitudes about the body” have a pervasive influence on many institutions in Nacirema society.

The anthropologist has become so familiar with the diversity of ways in which different people behave in similar situations that he is not apt to be surprised by even the most exotic customs. In fact, if all of the logically possible combinations of behavior have not been found somewhere in the world, he is apt to suspect that they must be present in some yet undescribed tribe. The point has, in fact, been expressed with respect to clan organization by Murdock [1] . In this light, the magical beliefs and practices of the Nacirema present such unusual aspects that it seems desirable to describe them as an example of the extremes to which human behavior can go.

Professor Linton [2] first brought the ritual of the Nacirema to the attention of anthropologists twenty years ago, but the culture of this people is still very poorly understood. They are a North American group living in the territory between the Canadian Cree, the Yaqui and Tarahumare of Mexico, and the Carib and Arawak of the Antilles. Little is known of their origin, although tradition states that they came from the east. According to Nacirema mythology, their nation was originated by a culture hero, Notgnihsaw, who is otherwise known for two great feats of strength—the throwing of a piece of wampum across the river Pa-To-Mac and the chopping down of a cherry tree in which the Spirit of Truth resided.

Nacirema culture is characterized by a highly developed market economy which has evolved in a rich natural habitat. While much of the people’s time is devoted to economic pursuits, a large part of the fruits of these labors and a considerable portion of the day are spent in ritual activity. The focus of this activity is the human body, the appearance and health of which loom as a dominant concern in the ethos of the people. While such a concern is certainly not unusual, its ceremonial aspects and associated philosophy are unique.

The fundamental belief underlying the whole system appears to be that the human body is ugly and that its natural tendency is to debility and disease. Incarcerated in such a body, man’s only hope is to avert these characteristics through the use of ritual and ceremony. Every household has one or more shrines devoted to this purpose. The more powerful individuals in the society have several shrines in their houses and, in fact, the opulence of a house is often referred to in terms of the number of such ritual centers it possesses. Most houses are of wattle and daub construction, but the shrine rooms of the more wealthy are walled with stone. Poorer families imitate the rich by applying pottery plaques to their shrine walls.

While each family has at least one such shrine, the rituals associated with it are not family ceremonies but are private and secret. The rites are normally only discussed with children, and then only during the period when they are being initiated into these mysteries. I was able, however, to establish sufficient rapport with the natives to examine these shrines and to have the rituals described to me.

The focal point of the shrine is a box or chest which is built into the wall. In this chest are kept the many charms and magical potions without which no native believes he could live. These preparations are secured from a variety of specialized practitioners. The most powerful of these are the medicine men, whose assistance must be rewarded with substantial gifts. However, the medicine men do not provide the curative potions for their clients, but decide what the ingredients should be and then write them down in an ancient and secret language. This writing is understood only by the medicine men and by the herbalists who, for another gift, provide the required charm.

The charm is not disposed of after it has served its purpose, but is placed in the charmbox of the household shrine. As these magical materials are specific for certain ills, and the real or imagined maladies of the people are many, the charm-box is usually full to overflowing. The magical packets are so numerous that people forget what their purposes were and fear to use them again. While the natives are very vague on this point, we can only assume that the idea in retaining all the old magical materials is that their presence in the charm-box, before which the body rituals are conducted, will in some way protect the worshiper.

Beneath the charm-box is a small font. Each day every member of the family, in succession, enters the shrine room, bows his head before the charm-box, mingles different sorts of holy water in the font, and proceeds with a brief rite of ablution [3] . The holy waters are secured from the Water Temple of the community, where the priests conduct elaborate ceremonies to make the liquid ritually pure.

In the hierarchy of magical practitioners, and below the medicine men in prestige, are specialists whose designation is best translated as “holy-mouth-men.” The Nacirema have an almost pathological horror of and fascination with the mouth, the condition of which is believed to have a supernatural influence on all social relationships. Were it not for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that their teeth would fall out, their gums bleed, their jaws shrink, their friends desert them, and their lovers reject them. They also believe that a strong relationship exists between oral and moral characteristics. For example, there is a ritual ablution of the mouth for children which is supposed to improve their moral fiber.

The daily body ritual performed by everyone includes a mouth-rite. Despite the fact that these people are so punctilious [4] about care of the mouth, this rite involves a practice which strikes the uninitiated stranger as revolting. It was reported to me that the ritual consists of inserting a small bundle of hog hairs into the mouth, along with certain magical powders, and then moving the bundle in a highly formalized series of gestures. [5]

In addition to the private mouth-rite, the people seek out a holy-mouth-man once or twice a year. These practitioners have an impressive set of paraphernalia, consisting of a variety of augers, awls, probes, and prods. The use of these items in the exorcism of the evils of the mouth involves almost unbelievable ritual torture of the client. The holy-mouth-man opens the client’s mouth and, using the above mentioned tools, enlarges any holes which decay may have created in the teeth. Magical materials are put into these holes. If there are no naturally occurring holes in the teeth, large sections of one or more teeth are gouged out so that the supernatural substance can be applied. In the client’s view, the purpose of these ministrations [6] is to arrest decay and to draw friends. The extremely sacred and traditional character of the rite is evident in the fact that the natives return to the holy-mouth-men year after year, despite the fact that their teeth continue to decay.

It is to be hoped that, when a thorough study of the Nacirema is made, there will be careful inquiry into the personality structure of these people. One has but to watch the gleam in the eye of a holy-mouth-man, as he jabs an awl into an exposed nerve, to suspect that a certain amount of sadism is involved. If this can be established, a very interesting pattern emerges, for most of the population shows definite masochistic tendencies. It was to these that Professor Linton referred in discussing a distinctive part of the daily body ritual which is performed only by men. This part of the rite includes scraping and lacerating the surface of the face with a sharp instrument. Special women’s rites are performed only four times during each lunar month, but what they lack in frequency is made up in barbarity. As part of this ceremony, women bake their heads in small ovens for about an hour. The theoretically interesting point is that what seems to be a preponderantly masochistic people have developed sadistic specialists.

The medicine men have an imposing temple, or latipso , in every community of any size. The more elaborate ceremonies required to treat very sick patients can only be performed at this temple. These ceremonies involve not only the thaumaturge [7] but a permanent group of vestal maidens who move sedately about the temple chambers in distinctive costume and headdress.

The latipso ceremonies are so harsh that it is phenomenal that a fair proportion of the really sick natives who enter the temple ever recover. Small children whose indoctrination is still incomplete have been known to resist attempts to take them to the temple because “that is where you go to die.” Despite this fact, sick adults are not only willing but eager to undergo the protracted ritual purification, if they can afford to do so. No matter how ill the supplicant or how grave the emergency, the guardians of many temples will not admit a client if he cannot give a rich gift to the custodian. Even after one has gained and survived the ceremonies, the guardians will not permit the neophyte to leave until he makes still another gift.

The supplicant entering the temple is first stripped of all his or her clothes. In everyday life the Nacirema avoids exposure of his body and its natural functions. Bathing and excretory acts are performed only in the secrecy of the household shrine, where they are ritualized as part of the body-rites. Psychological shock results from the fact that body secrecy is suddenly lost upon entry into the latipso . A man, whose own wife has never seen him in an excretory act, suddenly finds himself naked and assisted by a vestal maiden while he performs his natural functions into a sacred vessel. This sort of ceremonial treatment is necessitated by the fact that the excreta are used by a diviner to ascertain the course and nature of the client’s sickness. Female clients, on the other hand, find their naked bodies are subjected to the scrutiny, manipulation and prodding of the medicine men.

Few supplicants in the temple are well enough to do anything but lie on their hard beds. The daily ceremonies, like the rites of the holy-mouth-men, involve discomfort and torture. With ritual precision, the vestals awaken their miserable charges each dawn and roll them about on their beds of pain while performing ablutions, in the formal movements of which the maidens are highly trained. At other times they insert magic wands in the supplicant’s mouth or force him to eat substances which are supposed to be healing. From time to time the medicine men come to their clients and jab magically treated needles into their flesh. The fact that these temple ceremonies may not cure, and may even kill the neophyte, in no way decreases the people’s faith in the medicine men.

There remains one other kind of practitioner, known as a “listener.” This witchdoctor has the power to exorcise the devils that lodge in the heads of people who have been bewitched. The Nacirema believe that parents bewitch their own children. Mothers are particularly suspected of putting a curse on children while teaching them the secret body rituals. The counter-magic of the witchdoctor is unusual in its lack of ritual. The patient simply tells the “listener” all his troubles and fears, beginning with the earliest difficulties he can remember. The memory displayed by the Nacirema in these exorcism sessions is truly remarkable. It is not uncommon for the patient to bemoan the rejection he felt upon being weaned as a babe, and a few individuals even see their troubles going back to the traumatic effects of their own birth.

In conclusion, mention must be made of certain practices which have their base in native esthetics but which depend upon the pervasive aversion to the natural body and its functions. There are ritual fasts to make fat people thin and ceremonial feasts to make thin people fat. Still other rites are used to make women’s breasts larger if they are small, and smaller if they are large. General dissatisfaction with breast shape is symbolized in the fact that the ideal form is virtually outside the range of human variation. A few women afflicted with almost inhuman hyper-mammary development are so idolized that they make a handsome living by simply going from village to village and permitting the natives to stare at them for a fee.

Reference has already been made to the fact that excretory functions are ritualized, routinized, and relegated to secrecy. Natural reproductive functions are similarly distorted. Intercourse is taboo as a topic and scheduled as an act. Efforts are made to avoid pregnancy by the use of magical materials or by limiting intercourse to certain phases of the moon. Conception is actually very infrequent. When pregnant, women dress so as to hide their condition. Parturition takes place in secret, without friends or relatives to assist, and the majority of women do not nurse their infants.

Our review of the ritual life of the Nacirema has certainly shown them to be a magic-ridden people. It is hard to understand how they have managed to exist so long under the burdens which they have imposed upon themselves. But even such exotic customs as these take on real meaning when they are viewed with the insight provided by Malinowski [8] when he wrote:

Looking from far and above, from our high places of safety in the developed civilization, it is easy to see all the crudity and irrelevance of magic. But without its power and guidance early man could not have mastered his practical difficulties as he has done, nor could man have advanced to the higher stages of civilization.

Footnotes are added by Dowell as modified by Chase

- Murdock, George P. 1949. Social Structure . NY: The Macmillan Co., page 71. George Peter Murdock (1897-1996 [?]) is a famous ethnographer. ↵

- Linton, Ralph. 1936. The Study of Man . NY: D. Appleton-Century Co. page 326. Ralph Linton (1893-1953) is best known for studies of enculturation (maintaining that all culture is learned rather than inherited; the process by which a society's culture is transmitted from one generation to the next), claiming culture is humanity's "social heredity." ↵

- A washing or cleansing of the body or a part of the body. From the Latin abluere, to wash away ↵

- Marked by precise observance of the finer points of etiquette and formal conduct. ↵

- It is worthy of note that since Prof. Miner's original research was conducted, the Nacirema have almost universally abandoned the natural bristles of their private mouth-rite in favor of oil-based polymerized synthetics. Additionally, the powders associated with this ritual have generally been semi-liquefied. Other updates to the Nacirema culture shall be eschewed in this document for the sake of parsimony. ↵

- Tending to religious or other important functions ↵

- A miracle-worker. ↵

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. Magic, Science, and Religion . Glencoe: The Free Press, page 70. Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) is a famous cultural anthropologist best known for his argument that people everywhere share common biological and psychological needs and that the function of all cultural institutions is to fulfill such needs; the nature of the institution is determined by its function. ↵

Living Anthropologically

Anthropology – Understanding – Possibility

Home » Blog Posts » Anthropology Courses » The Nacirema

Nacirema thinking.

Body Ritual Among the Nacirema

Horace Miner’s “Body Ritual among the Nacirema” has been reprinted in many anthropology readers, including Applying Anthropology . It endures as a first-day favorite for Introduction to Anthropology courses, and is read far beyond anthropology. It has become the most downloaded article from the American Anthropological Association–see What is the Deal with the Nacirema?!? I usually now use the original 1956 source, a free download from the American Anthropological Association.

In 2018, a Twitter debate emerged on the use of the Nacirema. I love this devastating two-tweet critique from Takami Delisle:

the fact of its extensive damages to Native American groups. Then Miner goes on to talk about "shrine" & "temple" (as opposed to "church") and "holy mouth man" "witch doctor" and on and on. The attempt to "eroticize" Americans is actually exoticizing non-EuroAmerican ppl. — Takami (TAH-kah-mee) (@tsd1888) June 23, 2018

The post below was originally written in 2013.

The Nacirema & Human Nature

I have used “Body Ritual among the Nacirema” as a way to introduce anthropology, ideas of human similarity and difference, ethnocentrism, and cultural relativism. It corresponds to the material in the section on Human Nature and Anthropology . These issues continue to be current. Accounts of human beings as inherently warlike, only tamed by modern states and modern moral codes, have become newly popular and quite entrenched. See War, Peace, & Human Nature: Convergence of Evolution & Culture for a 2013 book that provided a counter-narrative.

One example of an apparent human universal–defecation and urination. In What Did Ancient Romans Do Without Toilet Paper? Stephen E. Nash shows how these practices are shaped by culture, history, and power. “It’s hard to argue that the use of toilet paper is somehow natural. . . . Defecation and urination are more than biological functions; they are cultural activities that involve artifacts and technologies that change through time.”

I’ve used this article on the first day of class, giving students 20 minutes to read and report back. I’ve always wondered how much I should preserve the identity of the Nacirema as a surprise. It seems like it should no longer be a surprise since a simple web-search reveals a Wikipedia Nacirema that gives it all away. There are also several videos on YouTube– Who are the Nacirema? may be one of the better ones, capturing how my classes often proceed.

After the surprise, I have then emphasized how Miner’s article is in some ways prophetic and has enduring relevance. As one student perceptively put it: what if Miner had been able to see tanning beds? Or as Melissa Leyva ends in her YouTube Nacirema , what if Miner had seen the little black boxes and phenomena like “Gotta catch ’em all”? (Leyva’s YouTube account has some good historical and contemporary imagery to subtly accompany the summarized Nacirema reading.)

Critiquing the Nacirema

From the outset, I have also incorporated quotes that could critique how “Body Ritual among the Nacirema” is usually introduced. First, from Renato Rosaldo’s Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis : “In retrospect, one wonders why Miner’s article was taken simply as a good-natured joke rather than as a scathing critique of ethnographic discourse. Who could continue to feel comfortable describing other people in terms that sound ludicrous when applied to ourselves?” (1989:52). Is 'Body Ritual Among the Nacirema' a good-natured joke or scathing critique? Click To Tweet I have used Rosaldo’s quote to underscore how we need to be careful when reading overgeneralizing ethnographic accounts.

Second, and more importantly, from Michaela di Leonardo, Exotics at Home , on how Miner’s language “effaces the colonial encounter through which we have developed notions of ‘witch doctors’ and ‘exotic rituals.’ Miner’s whimsical frame also denies stratification and power dynamics on the American end” (1998:61).

I’ve always felt Miner’s account is misleading on the power dynamics of various ethnocentrisms. The sections from di Leonardo emphasize this aspect. However, the di Leonardo quote has been a bit too much on the first day of an Introduction to Anthropology course. It may work better within the context of a Cultural Anthropology course that is exploring the trajectory of the culture concept in its colonial context.

Should Miner’s article still be used to introduce anthropology? It’s definitely worth careful consideration. If you do use it, please consider the critiques.

Living Anthropologically means documenting history, interconnection, and power during a time of global transformation. We need to care for others as we attempt to build a world together. This blog is a personal project of Jason Antrosio, author of Fast, Easy, and In Cash: Artisan Hardship and Hope in the Global Economy . For updates, subscribe to the YouTube channel or follow on Twitter .

Living Anthropologically is part of the Amazon Associates program and earns a commission from qualifying purchases, including ads and Amazon text links. There are also Google ads and Google Analytics which may use cookies and possibly other tracking information. See the Privacy Policy .

Home > Dedman School of Law > Law Journals > SMU Law Review > Vol. 67 (2014) > Iss. 4

SMU Law Review

The nacirema revisited.

Jeffrey D. Kahn , Southern Methodist University, Dedman School of Law Follow

In 1956, anthropologist Horace Miner published the article for which he is best known, "Body Ritual among the Nacirema." This short but groundbreaking essay described personal rituals practiced by a fascinating but poorly understood people. Inspired by Miner's work and based on close-quarters field research, this essay revisits the strange world of the Nacirema. Two of the more "legal" features of their society are explored: (1) what might be termed the higher-order constitutional design of their society, and (2) the mechanisms of day-to-day maintenance of their social order.

Recommended Citation

Jeffrey D. Kahn, The Nacirema Revisited , 67 SMU L. Rev. 807 (2014)

Since January 21, 2015

Included in

Rule of Law Commons

- Journal Home

- Association Home

- Editorial Board

- Submissions

- Dedman School of Law

- Most Popular Papers

- Receive Email Notices or RSS

Advanced Search

ISSN: 1066-1271

About | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Body Ritual among the Nacirema

This journal article satirizes anthropological papers on "other" cultures, and the culture of the United States. Published in American Anthropologist , vol 58, June 1956. pp. 503–507.

HORACE MINER University of Michigan

The anthropologist has become so familiar with the diversity of ways in which different people behave in similar situations that he is not apt to be surprised by even the most exotic customs. In fact, if all of the logically possible combinations of behavior have not been found somewhere in the world, he is apt to suspect that they must be present in some yet undescribed tribe. The point has, in fact, been expressed with respect to clan organization by Murdock. In this light, the magical beliefs and practices of the Nacirema present such unusual aspects that it seems desirable to describe them as an example of the extremes to which human behavior can go.

Professor Linton first brought the ritual of the Nacirema to the attention of anthropologists twenty years ago, but the culture of this people is still very poorly understood. They are a North American group living in the territory between the Canadian Cree, the Yaqui and Tarahumare of Mexico, and the Carib and Arawak of the Antilles. Little is known of their origin, although tradition states that they came from the east. According to Nacirema mythology, their nation was originated by a culture hero, Notgnihsaw, who is otherwise known for two great feats of strength—the throwing of a piece of wampum across the river Pa-To-Mac and the chopping down of a cherry tree in which the Spirit of Truth resided.

Nacirema culture is characterized by a highly developed market economy which has evolved in a rich natural habitat. While much of the people's time is devoted to economic pursuits, a large part of the fruits of these labors and a considerable portion of the day are spent in ritual activity. The focus of this activity is the human body, the appearance and health of which loom as a dominant concern in the ethos of the people. While such a concern is certainly not unusual, its ceremonial aspects and associated philosophy are unique.

The fundamental belief underlying the whole system appears to be that the human body is ugly and that its natural tendency is to debility and disease. Incarcerated in such a body, man's only hope is to avert these characteristics through the use of ritual and ceremony. Every household has one or more shrines devoted to this purpose. The more powerful individuals in the society have several shrines in their houses and, in fact, the opulence of a house is often referred to in terms of the number of such ritual centers it possesses. Most houses are of wattle and daub construction, but the shrine rooms of the more wealthy are walled with stone. Poorer families imitate the rich by applying pottery plaques to their shrine walls.

While each family has at least one such shrine, the rituals associated with it are not family ceremonies but are private and secret. The rites are normally only discussed with children, and then only during the period when they are being initiated into these mysteries. I was able, however, to establish sufficient rapport with the natives to examine these shrines and to have the rituals described to me.

The focal point of the shrine is a box or chest which is built into the wall. In this chest are kept the many charms and magical potions without which no native believes he could live. These preparations are secured from a variety of specialized practitioners. The most powerful of these are the medicine men, whose assistance must be rewarded with substantial gifts. However, the medicine men do not provide the curative potions for their clients, but decide what the ingredients should be and then write them down in an ancient and secret language. This writing is understood only by the medicine men and by the herbalists who, for another gift, provide the required charm.

The charm is not disposed of after it has served its purpose, but is placed in the charmbox of the household shrine. As these magical materials are specific for certain ills, and the real or imagined maladies of the people are many, the charm-box is usually full to overflowing. The magical packets are so numerous that people forget what their purposes were and fear to use them again. While the natives are very vague on this point, we can only assume that the idea in retaining all the old magical materials is that their presence in the charm-box, before which the body rituals are conducted, will in some way protect the worshiper.

Beneath the charm-box is a small font. Each day every member of the family, in succession, enters the shrine room, bows his head before the charm-box, mingles different sorts of holy water in the font, and proceeds with a brief rite of ablution. The holy waters are secured from the Water Temple of the community, where the priests conduct elaborate ceremonies to make the liquid ritually pure.

In the hierarchy of magical practitioners, and below the medicine men in prestige, are specialists whose designation is best translated as "holy-mouth-men." The Nacirema have an almost pathological horror of and fascination with the mouth, the condition of which is believed to have a supernatural influence on all social relationships. Were it not for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that their teeth would fall out, their gums bleed, their jaws shrink, their friends desert them, and their lovers reject them. They also believe that a strong relationship exists between oral and moral characteristics. For example, there is a ritual ablution of the mouth for children which is supposed to improve their moral fiber.

The daily body ritual performed by everyone includes a mouth-rite. Despite the fact that these people are so punctilious about care of the mouth, this rite involves a practice which strikes the uninitiated stranger as revolting. It was reported to me that the ritual consists of inserting a small bundle of hog hairs into the mouth, along with certain magical powders, and then moving the bundle in a highly formalized series of gestures.

In addition to the private mouth-rite, the people seek out a holy-mouth-man once or twice a year. These practitioners have an impressive set of paraphernalia, consisting of a variety of augers, awls, probes, and prods. The use of these items in the exorcism of the evils of the mouth involves almost unbelievable ritual torture of the client. The holy-mouth-man opens the client's mouth and, using the above mentioned tools, enlarges any holes which decay may have created in the teeth. Magical materials are put into these holes. If there are no naturally occurring holes in the teeth, large sections of one or more teeth are gouged out so that the supernatural substance can be applied. In the client's view, the purpose of these ministrations is to arrest decay and to draw friends. The extremely sacred and traditional character of the rite is evident in the fact that the natives return to the holy-mouth-men year after year, despite the fact that their teeth continue to decay.

It is to be hoped that, when a thorough study of the Nacirema is made, there will be careful inquiry into the personality structure of these people. One has but to watch the gleam in the eye of a holy-mouth-man, as he jabs an awl into an exposed nerve, to suspect that a certain amount of sadism is involved. If this can be established, a very interesting pattern emerges, for most of the population shows definite masochistic tendencies. It was to these that Professor Linton referred in discussing a distinctive part of the daily body ritual which is performed only by men. This part of the rite includes scraping and lacerating the surface of the face with a sharp instrument. Special women's rites are performed only four times during each lunar month, but what they lack in frequency is made up in barbarity. As part of this ceremony, women bake their heads in small ovens for about an hour. The theoretically interesting point is that what seems to be a preponderantly masochistic people have developed sadistic specialists.

The medicine men have an imposing temple, or latipso , in every community of any size. The more elaborate ceremonies required to treat very sick patients can only be performed at this temple. These ceremonies involve not only the thaumaturge but a permanent group of vestal maidens who move sedately about the temple chambers in distinctive costume and headdress.

The latipso ceremonies are so harsh that it is phenomenal that a fair proportion of the really sick natives who enter the temple ever recover. Small children whose indoctrination is still incomplete have been known to resist attempts to take them to the temple because "that is where you go to die." Despite this fact, sick adults are not only willing but eager to undergo the protracted ritual purification, if they can afford to do so. No matter how ill the supplicant or how grave the emergency, the guardians of many temples will not admit a client if he cannot give a rich gift to the custodian. Even after one has gained and survived the ceremonies, the guardians will not permit the neophyte to leave until he makes still another gift.

The supplicant entering the temple is first stripped of all his or her clothes. In everyday life the Nacirema avoids exposure of his body and its natural functions. Bathing and excretory acts are performed only in the secrecy of the household shrine, where they are ritualized as part of the body-rites. Psychological shock results from the fact that body secrecy is suddenly lost upon entry into the latipso . A man, whose own wife has never seen him in an excretory act, suddenly finds himself naked and assisted by a vestal maiden while he performs his natural functions into a sacred vessel. This sort of ceremonial treatment is necessitated by the fact that the excreta are used by a diviner to ascertain the course and nature of the client's sickness. Female clients, on the other hand, find their naked bodies are subjected to the scrutiny, manipulation and prodding of the medicine men.

Few supplicants in the temple are well enough to do anything but lie on their hard beds. The daily ceremonies, like the rites of the holy-mouth-men, involve discomfort and torture. With ritual precision, the vestals awaken their miserable charges each dawn and roll them about on their beds of pain while performing ablutions, in the formal movements of which the maidens are highly trained. At other times they insert magic wands in the supplicant's mouth or force him to eat substances which are supposed to be healing. From time to time the medicine men come to their clients and jab magically treated needles into their flesh. The fact that these temple ceremonies may not cure, and may even kill the neophyte, in no way decreases the people's faith in the medicine men.

There remains one other kind of practitioner, known as a "listener." This witchdoctor has the power to exorcise the devils that lodge in the heads of people who have been bewitched. The Nacirema believe that parents bewitch their own children. Mothers are particularly suspected of putting a curse on children while teaching them the secret body rituals. The counter-magic of the witchdoctor is unusual in its lack of ritual. The patient simply tells the "listener" all his troubles and fears, beginning with the earliest difficulties he can remember. The memory displayed by the Nacirema in these exorcism sessions is truly remarkable. It is not uncommon for the patient to bemoan the rejection he felt upon being weaned as a babe, and a few individuals even see their troubles going back to the traumatic effects of their own birth.

In conclusion, mention must be made of certain practices which have their base in native esthetics but which depend upon the pervasive aversion to the natural body and its functions. There are ritual fasts to make fat people thin and ceremonial feasts to make thin people fat. Still other rites are used to make women's breasts larger if they are small, and smaller if they are large. General dissatisfaction with breast shape is symbolized in the fact that the ideal form is virtually outside the range of human variation. A few women afflicted with almost inhuman hyper-mammary development are so idolized that they make a handsome living by simply going from village to village and permitting the natives to stare at them for a fee.

Reference has already been made to the fact that excretory functions are ritualized, routinized, and relegated to secrecy. Natural reproductive functions are similarly distorted. Intercourse is taboo as a topic and scheduled as an act. Efforts are made to avoid pregnancy by the use of magical materials or by limiting intercourse to certain phases of the moon. Conception is actually very infrequent. When pregnant, women dress so as to hide their condition. Parturition takes place in secret, without friends or relatives to assist, and the majority of women do not nurse their infants.

Our review of the ritual life of the Nacirema has certainly shown them to be a magic-ridden people. It is hard to understand how they have managed to exist so long under the burdens which they have imposed upon themselves. But even such exotic customs as these take on real meaning when they are viewed with the insight provided by Malinowski when he wrote:

Looking from far and above, from our high places of safety in the developed civilization, it is easy to see all the crudity and irrelevance of magic. But without its power and guidance early man could not have mastered his practical difficulties as he has done, nor could man have advanced to the higher stages of civilization.

REFERENCES CITED

Linton, Ralph 1936 The Study of Man. New York, D. Appleton Century Co.

Malinowski, Bronislaw 1948 Magic, Science, and Religion. Glencoe, The Free Press.

Murdock, George P. 1949 Social Structure. New York, The Macmillan Co.

This work is in the public domain worldwide because it has been so released by the copyright holder.

Public domain Public domain false false

- Undated works

Navigation menu

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In everyday life the Nacirema avoids exposure of his body and its natural functions. Bathing and excretory acts are performed only in the secrecy of the household shrine, where they are ritualized as part of the body-rites. Psychological shock results from the fact that body secrecy is suddenly lost upon entry into the latipso. A man, whose own ...

Ugliness of the Body. The fundamental belief of the Nacirema is that the body is ugly and prone to weakness. Therefore, man uses ritual and ceremony to avert his vulnerability. Homes have shrines made of stone for these customs, and those with more money may even have many shrines. The rituals that occur in the shrines are private, discussed ...

Body Rituals: The Nacirema are described as engaging in numerous body rituals throughout the day, such as scraping and lacerating the surface of the face with a sharp instrument, a satirical description of shaving or makeup application. Miner's article serves as a critique of anthropological practices and the Western perspective on "exotic ...

Body Ritual Among the Nacirema is a satirical essay written by Horace Miner in 1956. The essay describes the peculiar and seemingly bizarre rituals and behaviors of a fictional group of people called the Nacirema. However, the essay is a clever critique of American culture and its obsession with body image and the beauty industry.

Body Ritual among the Nacirema Expository Essay. Culture is the way of life of a social group. From the sociological aspect, culture has five key elements that well describe a people's ways of thinking and action. The elements include beliefs, norms, values, symbols, and language. Beliefs are avowals that a social group hold to be true.

Nacirema culture is characterized by a highly developed market economy which has evolved in a rich natural habitat. While much of the people's time is de-voted to economic pursuits, a large part of the fruits of these labors and a consider-able portion of the day are spent in ritual activity. The focus of this activity is the human body, the ...

Magic and Superstition in Ritual. Miner describes many of the rituals of the Nacirema as magic-inspired beliefs and practices. The household shrine houses magical potions that are obtained from medicine men and dispensed by herbalists. These are hoarded by the natives as cure-alls for ills; they believe that they could not survive without the ...

In 1956, the journal American Anthropologist published a short paper by University of Michigan anthropologist Horace Miner titled " Body Ritual Among the Nacirema ," detailing the habits of this "North American group.". Among the "exotic customs" it explores are the use of household shrines containing charm-boxes filled with magical ...

In every-day life the Nacirema avoids exposure of his body and its natural functions. Bathing and excretory acts are performed only in the secrecy of the household shrine, where they are ritualized as part of the body-rites. Psycho- logical shock results from the fact that body secrecy is suddenly lost upon entry into the latipso.

Revised from "Body Ritual Among the Nacirema" by Horace Miner, American Anthropologist Magazine58(3), 1956, pp. 503-7 T he ritual of the Nacirema was first brought to the attention of anthropologists twenty years ago, but the culture of this people is still very poorly under-stood. They are a North American group living in the ter-

Nacirema culture is characterized by a highly developed market economy which has evolved in a rich natural habitat. While much of the people's time is devoted to economic pursuits, a large part of the fruits of these labors and a considerable portion of the day are spent in ritual activity. The focus of this activity is the human body, the ...

The Nacirema & Human Nature. I have used "Body Ritual among the Nacirema" as a way to introduce anthropology, ideas of human similarity and difference, ethnocentrism, and cultural relativism. It corresponds to the material in the section on Human Nature and Anthropology. These issues continue to be current.

BODY RITUAL AMONG THE NACIREMA (Adapted from article by Horace Miner) In this article, Horace Miner demonstrates that attitudes about the body have an ... and by the herbalists who, for another gift, provide the required charm. The charm is not disposed of after it has served its purpose, but is placed in the charm box of the household shrine ...

"Body Ritual among the Nacirema" Horace Miner [1 - footnotes are at the end of this document] ... herbalists who, for another gift, provide the required charm. ¶ 6 The charm is not disposed of after it has served its purpose, but is placed in the charmbox of the household shrine. As these magical materials are specific for

what are the nacirema? they are a north american group. who is their cultural hero. notgnihsaw. what is their fundamental belief. the human body is ugly and that its natural tendency is to debility and disease; man can avert these through ritual and ceremony. what is their "shrine". bathroom? who are the medicine men.

405 Words. 2 Pages. Open Document. "Body Ritual among the Nacirema" is an article by Horace Miner that depicts a group of tribespeople known as the Nacirema, but is referring to Americans, whose cultural beliefs are firmly implanted in the idea that the human body is prone to illness and disfigurement. Miner establishes how the attitudes about ...

In 1956, anthropologist Horace Miner published the article for which he is best known, "Body Ritual among the Nacirema." This short but groundbreaking essay described personal rituals practiced by a fascinating but poorly understood people. Inspired by Miner's work and based on close-quarters field research, this essay revisits the strange world of the Nacirema. Two of the more "legal ...

18 terms. Nairobi0_0. Preview. The body rituals of the Nacirema. 8 terms. ashleybarry. Preview. NDFS 362 Exam #2 pt 2. 22 terms.

BODY RITUAL AMONG THE NACIREMA. Revised from "Body Ritual Among the Nacirema" by Horace Miner, American Anthropologist Magazine 58 (3), 1956, pp. 503-7. The ritual of the Nacirema was first brought to the attention of anthropologists twenty years ago, but the culture of this people is still very poorly understood.

Published in American Anthropologist, vol 58, June 1956. pp. 503-507. Body Ritual among the Nacirema. HORACE MINER. University of Michigan. The anthropologist has become so familiar with the diversity of ways in which different people behave in similar situations that he is not apt to be surprised by even the most exotic customs.