Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 February 2024

Teachers’ perceived work ability: a qualitative exploration using the Job Demands-Resources model

- Petr Hlado ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8398-6367 1 &

- Klara Harvankova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7984-8861 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 304 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1182 Accesses

Metrics details

Teaching is a highly demanding profession; therefore, it is necessary to address how teachers cope with the demands of their job and how these demands affect their work ability. This study aims to investigate teachers’ perceptions of work ability and the underlying mechanisms through which job demands influence their perceived work ability. The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model serves as the theoretical framework for this investigation. A qualitative approach was employed, utilizing in-depth interviews with a sample of 14 upper secondary school teachers in the Czech Republic. The teachers had an average age of 46.9 years (SD = 9.22). The findings revealed a limited awareness among teachers regarding the holistic nature of work ability. Job demands emerged as a factor indirectly impacting perceived work ability through the health impairment process. High job demands and obstacles contributed to teacher stress, resulting in fatigue, impaired physical or mental health, and reduced perceived work ability. Moreover, the study showed how tough job demands extend beyond the professional realm, leading to work-family conflicts that further impair work ability. This study provided empirical support for the inclusion of perceived work ability as an outcome influenced by job demands within the JD-R model. Additionally, it emphasized the need for a comprehensive framework that considers both organizational and individual factors in both work and non-work domains to effectively investigate perceived work ability among teachers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Beyond occupational exhaustion: exploring the influence of positive meaningful work on teachers’ psychoemotional well-being in the digital age

A quantitative study on the impact of working environment on the well-being of teachers in China’s private colleges

Job satisfaction and self-efficacy of in-service early childhood teachers in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era

Introduction.

Teaching is an increasingly demanding profession. Teachers often express concerns about high workloads, bureaucracy, time pressure, multitasking, fear of failure and errors, lack of support from head teachers and co-workers, disruptive student behavior and misbehavior, difficulties in cooperating with parents, and a lack of acknowledgment and appreciation (Mäkelä et al. 2015 ). Moreover, specific physiological and psychological job demands (Erick and Smith 2011 ), along with the limited individual preconditions for their fulfillment, can lead to teachers experiencing feelings of insufficiency, relatively high stress levels, low job satisfaction, and turnover (Bogaert et al. 2014 ). Therefore, addressing how teachers can cope with these job demands and how they affect their work ability is necessary.

Work ability

The work ability (WA) construct was introduced to identify whether individuals can meet the physical and psychosocial demands of their profession. Ilmarinen et al. ( 2008 ) defined WA as a balance between personal resources and work characteristics. This definition highlights an individual’s capacity to fulfill required work tasks and effectively manage job demands (Ilmarinen et al. 1997 ). WA is a dynamic process influenced by various factors, including physical and mental health, functional abilities, qualifications, professional competencies, attitudes, motivation, working conditions, job demands, and environmental factors (Tuomi et al. 2001 ). Overall, WA represents an individual’s ability, or perceptions of their ability, to meet the demands of their job (Hlaďo et al. 2017 ; Ilmarinen 2009 ).

Objective and perceived work ability

Some researchers drew attention to several problems associated with the originally atheoretical nature of the WA construct and noted that WA was in many studies operationalized inconsistently (Cadiz et al. 2019 ). Thus, it is unclear if WA is a single overarching construct or a composite of several related but distinct aspects. The construct of WA has recently been critically evaluated. Currently, two dimensions of WA are distinguished: objective and perceived WA (e.g., Cadiz et al. 2019 ; Freyer et al. 2019 ; McGonagle et al. 2015 ). Objective WA is strictly based on evaluating the employee’s health and functional limitations (McGonagle et al. 2015 ), whereas perceived WA refers to the employee’s self-perception or self-assessment of their ability to continue working in their current job (Brady et al. 2020 ; McGonagle et al. 2022 ). Perceived WA seems to be a more appropriate approach because assessing health conditions as an indicator of WA is of questionable value unless those health conditions are tied to specific job requirements (Brady et al. 2020 ). Perceived WA is not based on reporting diagnosed chronic health conditions but on subjective perceptions of health and other aspects concerning functional capacity to perform job requirements (McGonagle et al. 2015 ). Thus, Brady et al. ( 2020 ) argue that perceptions of WA provide a sufficient assessment of this construct.

Antecedents of work ability

In recent years, several studies, meta-analyses, and reviews have aimed to identify and better understand a range of work-focused antecedents of WA as a way to maintain and enhance WA (Cadiz et al. 2019 ; Cloostermans et al. 2015 ; van den Berg et al. 2009 ). Prior research conducted among a general adult population has revealed that physical, mental, and psychosocial work-related conditions, job demands, and resources can have positive or negative effects on WA (Brady et al. 2020 ; Li et al. 2016 ; van den Berg et al. 2009 ). The research focused specifically on teachers has shown that their WA is negatively affected by, for example, poor indoor environment (Vertanen-Greis et al. 2022 ), noise at work (de Alcantara et al. 2019 ), and other physical demands of work (Sottimano et al. 2017 ). Poorly organized work processes, time pressure, fear of failure or mistakes at work (Ilmarinen et al. 1991 ), monotonous and uninteresting work, and lack of freedom or autonomy (Tuomi et al. 2001 ; van den Berg et al. 2009 ) were also found to be negatively related to WA. Recent studies have shown that specific work characteristics, such as high job demands and lack of discipline, can have adverse effects on the WA of teachers (de Alcantara et al. 2019 ). Additionally, the emotional demands of teaching have been found to significantly impact teachers’ WA, with research indicating a link between students’ misbehavior and reduced WA (Hakanen et al. 2006 ). Other aspects reflected in research on teachers’ WA are job stress and psychological strain arising from the nature of the teaching profession (Vertanen-Greis et al. 2022 ). For example, Hlaďo et al. ( 2020 ) demonstrated the effect of burnout on teachers’ diminished WA.

Conversely, intrinsic aspects of the job, particularly the perceived meaning of work, have been identified as a positive predictor of teachers’ WA (Sottimano et al. 2017 ). Social environmental factors have also been shown to play a significant role in WA, with studies indicating that a supportive organizational climate, favorable interpersonal relations, co-worker and supervisor support, and feedback can positively impact WA (Airila et al. 2014 ; Leijon et al. 2017 ). Finally, research has highlighted the importance of personal resources such as self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-confidence, and sense of coherence for maintaining and promoting WA (Airila et al. 2014 ; Guidetti et al. 2018 ; Hlaďo et al. 2020 ).

Job-demands resources model as a theoretical framework for anchoring work ability

WA literature highlighted the lack of theoretical grounding for the construct (Cadiz et al. 2019 ). Since WA is conceptualized as a balance between personal resources and job demands (Ilmarinen et al. 2008 ), the job demands-resources model (JD-R; Bakker and Demerouti, 2007 ; Demerouti et al. 2001 ) can be used as an integrative conceptual framework for studying WA among teachers. The JD-R model proposes that every job environment includes two general characteristics: job demands and job resources. Job demands are those physical, social, or organizational aspects of a job that require sustained physical or psychological effort and are associated with physical or psychological costs and cause strain (Demerouti et al. 2001 ). Job resources are those aspects of the job that help employees achieve work goals, reduce job demands, and stimulate personal growth, learning, and development (Demerouti et al. 2001 ). The JD-R model, as proposed in the interaction hypothesis, posits that job demands and job resources interact (Taris et al. 2017 ). While elevated job demands are expected to have detrimental effects on strain and health, a high level of job resources is expected to mitigate these effects. In fact, combining a high level of job resources and high job demands is expected to result in a sense of challenge and even higher work motivation (Bakker and Demerouti 2007 ; Bakker et al. 2007 ). Some researchers have suggested that specific job resources should align with the job demands in the workplace to diminish their adverse impact—a concept also referred to as the matching hypothesis (Langseth-Eide 2019 ).

Furthermore, two independent psychological processes have been identified: the health impairment process and the motivational process (Bakker and Demerouti 2007 ). In the first, the health impairment process, high job demands may exhaust an individual’s mental and physical resources and thus may lead to energy depletion and adverse health outcomes. In the second, the motivational process, it is assumed that job resources have motivational potential and lead to high work engagement and positive job outcomes. Considering the motivational process, job resources can promote intrinsic motivation, leading to employee growth, learning, and development, or extrinsic motivation and help achieve work goals. Thus, we differentiate work characteristics of the teaching profession as job demands that invoke strain and job resources that promote growth and facilitate work.

The revised JD-R model (Bakker and Demerouti 2007 ; Taris et al. 2017 ) highlighted the crucial role of personal resources in promoting employee well-being and work engagement. Personal resources are defined as self-related characteristics that are generally linked to resilience and refer to the individual’s sense of ability to successfully control and impact their environment (Hobfoll 2002 ). Within the JD-R model, various personal resources were considered, e.g., extraversion, hope, intrinsic motivation, need satisfaction, optimism, resilience, self-efficacy, and value orientation (Schaufeli and Taris 2014 ). Personal resources can act as mediators or moderators between job characteristics and outcomes, antecedents of strain and motivation, antecedents of work characteristics, or outcomes of work characteristics (Taris et al. 2017 ).

Concerning the JD-R theory (Schaufeli and Taris 2014 ), WA can be integrated into the JD-R model as an outcome that is positively influenced by job resources and personal resources and negatively affected by job demands (Brady et al. 2020 ; see McGonagle et al. 2022 for more details). Applying the JD-R model provides the opportunity to place predictors of WA into categories such as job demands, job resources, or personal resources. Thus, using the JD-R model as a theoretical framework, researchers can better understand the mechanisms underlying the relationship between WA and its predictors, providing insights for intervention and prevention strategies to improve WA among teachers.

Purpose of the present study

First, previous research on WA has mainly been deductive, based on a quantitative approach. The most commonly used tool to measure WA is the Work Ability Index (WAI), which combines objective and perceived measures (see Cadiz et al. 2019 , for more details). There are also concerns about the construct validity and psychometric qualities of this instrument (Cadiz et al. 2019 ). Second, research has identified various predictors of WA, but there is still a lack of profound knowledge about how and why the variables interact. Deductive research, while informative, inherently limits the variables investigated to those specified a priori by the researchers (McGonagle et al. 2022 ). Thus, it can be concluded that deductive research has not identified all potential predictors of WA and the mechanisms by which they affect WA.

We contribute to the literature by addressing these issues with a qualitative approach, which allows insight into perceived work ability (PWA) through the lived experience of teachers in their professional lives. The emic perspective of teachers will help better understand the relationships and processes hypothesized in the JD-R model (Demerouti and Bakker 2006 ) and the conceptual integration of PWA (Cadiz et al. 2019 ). By employing an inductive approach, our research contributes to comprehending and elucidating the mechanisms underlying the impact of job demands on PWA. It also endeavors to uncover teachers’ subjective perceptions of WA and explore additional unidentified factors that may influence it. This study enriches the existing body of knowledge by providing insights into the complex dynamics between PWA and diverse determinants within the teaching profession. Our research also significantly contributes to the literature by focusing on the unique sample, namely teachers. PWA is a construct closely linked to the demands of a particular profession. As a result, PWA can vary depending on the requirements of a specific occupation (Cadiz et al. 2019 ). Considering the distinctive nature of the teaching profession, our study aims to examine PWA among teachers in greater detail. This occupation presents numerous dissimilarities compared to other professions, emphasizing the significance of exploring the specific job challenges that teachers encounter.

In sum, to help expand and deepen understanding of the WA construct regarding the JD-R model, we address the following research questions:

Research Question 1: What do teachers evaluate when asked to assess their PWA?

Research Question 2: What job demands do teachers encounter in their work, and what is their mechanism of acting on PWA?

In light of the research gap and research questions, a qualitative approach has been chosen to capture the emic perspectives of participants regarding how teachers understand PWA. This research design provides a rich understanding of the ways in which teachers’ PWA is formed and allows us to capture the complexity and nuances of this process. Qualitative research facilitates a detailed comparison of participants’ statements, tracks their development and changes over time, explores the underlying mechanisms, and considers the effects of contextual factors, individual situations, and conditions often overlooked by studies applying quantitative design.

The research sample consisted of upper secondary school teachers in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. The sample was chosen intentionally. One of the main criteria was including teachers of different age categories, since WA typically decreases with age (Hlaďo et al. 2020 ; van den Berg et al. 2011 ). Thus, the age variability of the sample is crucial for understanding the aspects that influence PWA at different ages. Access to the research field was provided through the Towards Successful Seniority training program. Participants were recruited from those interested in the training. This decision ensured that participants were interested in the phenomena of WA and would be more open and truthful, as the in-depth interviews included sensitive topics (e.g., health information, family situation, relationships). First, participants were informed about the research objectives and the data collection process and were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of the research. At this stage, preliminary consent to participate in the study was obtained from twenty teachers. Fourteen teachers were gradually selected from this group based on the criteria set. Most of the sample was female ( n = 11), with only three male participants, consistent with the gender composition of teachers in Czech schools. The mean age of the participants was 46.9 years (SD = 9.22). The youngest participant was 27 (i.e., at the beginning of their career), while the oldest participant was 57. The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1 .

Data collection

The method of data collection was in-depth interviews. Before data collection, a structured pyramid interview protocol (Wengraf 2001 ) was created, containing 62 open-ended questions. The order of the questions in the interview protocol was not strictly followed in the interviews. In conducting the interviews, we started from the focal points of interest of the interviewees, which were developed through follow-up questions in the interview protocol. We applied this strategy to maximize the profit of the interviews and to allow participants to highlight aspects and processes that they considered subjectively significant. Moreover, this approach simulates a regular interview. The interview questions were about teachers’ health and lifestyle (e.g., How do your job demands affect your lifestyle?) , competence and job requirements (e.g., How has your profession changed in recent years? ), motivation, values, and appreciation (e.g., How do those around you appreciate your job? ), work environment, community and leadership (e.g., What feedback do you get from your supervisor? ).

The interviews were conducted during September and October 2020 and lasted approximately 90 min. The form (in person, online, phone) or interview location were chosen so the teachers felt comfortable, undisturbed, and safe to articulate their concerns. We ensured that participants were given sufficient time to contemplate their personal experiences. The interviews were recorded and then transcribed verbatim into text form. The total data corpus consisted of 433 pages of text. Data collection was stopped when theoretical data saturation occurred, interviews no longer provided new or significant information, and participants’ statements became repetitive (Corbin and Strauss 2014 ).

Interviews were analyzed using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti (7.5.18). An approach based on the grounded theory of Charmaz ( 2014 ) and Corbin and Strauss ( 2014 ) was adopted for the data analysis. First, open coding was performed, focusing on data fragments. Semantic units were searched for, which were then systematically compared with each other to find similarities or differences and to create relevant codes. Marking all units of text was followed by categorizing them and trying to find relationships between the categories. Second, to identify processes and their products and to understand how contextual circumstances determine them, we followed the strategies of logical and causal chain construction (Miles and Huberman 1994 ). We combined individual isolated events into logically linked sequences of events, for which we further identified causal links and temporal succession.

Ethical considerations

The Research Ethics Commitee of the Masaryk University (EKV-2018-045) reviewed and approved this study’s procedures, which were carried out according to the committee’s recommendations. This study complied with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association (APA). The informed consent form, presented at the beginning of the data collection and obtained from all participants, stated that participation in the study was voluntary, unpaid, anonymous, and confidential.

Work ability construct from the perspective of teachers

In the interviews, we focused closely on how teachers Footnote 1 understand PWA and the extent to which their perceptions match the definition of this construct. In our sample, there was a relatively high degree of variability in teachers’ views of the definition of PWA, and we identified three distinct perceptions: (1) PWA as physical and mental health, (2) PWA as professional competence, and (3) PWA as the capacity to meet job demands.

Perceived work ability as physical and mental health

The first group of teachers limited PWA to physical and mental health, which they consider to be a necessary starting point for engaging in the teaching profession. For instance, Lena believes that PWA encompasses not only a physical condition but also a mental one: For me, work ability principally means a physical condition but also a mental condition, so be just fine (Lena). Nadia’s definition of PWA goes further, incorporating maximum physical and mental well-being: I consider work ability as working in maximum physical and mental well-being (Nadia). In this regard, participants consider health and functional capacity to be the most important factors for performing teaching work, forming the fundamental pillar of PWA (Ilmarinen 2019 ). Thus, their understanding of PWA aligns with the traditional medical view, and, not surprisingly, it was mainly related to aging teachers who may already be experiencing health problems. However, if the teachers in our research defined WA as a satisfactory state of health for meeting job demands, they emphasized mental health over physical health. For example, Mike defines PWA as a sufficient mental state to perform work reasonably and simultaneously not collapse or go mad . The predominant emphasis on mental health is probably because the participants considered teaching a profession with an increased risk of job stress and emotional exhaustion and, thus, mental health problems. Altogether, low mental well-being limits the performance of the teaching profession and, consequently, PWA.

Although teaching can be challenging due to various illnesses, our study participants reported that only certain diagnoses resulted in losing their PWA and made it impossible for them to continue teaching. For instance, Claudia claimed that their voice was a crucial tool in their profession since they spent significant time communicating with students: The constant talking at school is getting to my vocal cords. Last year, I had a vocal cord disease for two months because of work (Claudia). Therefore, our findings suggest that objective measures of WA, which do not account for the subjective experiences of diagnosed illnesses, may not provide a complete picture of an individual’s ability to meet the requirements of the teaching profession. When assessing WA, it is essential to consider the unique challenges that teachers face, such as the job demands of teaching and the impact on their health. This can help identify potential risks and provide appropriate support to help teachers maintain their health and continue in their profession.

Perceived work ability as a professional competence

The second group of teachers in our study reduced PWA to another resource constituting individual capacity for independent fulfillment of job demands, namely professional competence: I see work ability as meaning that a person is fully qualified and completely self-sufficient. Just competent to work; that is what I see as work ability (Georgina). Teachers in our sample explained the emphasis on this aspect, stating that in the teaching profession, it is essential to constantly maintain, update and develop knowledge and skills for effective teaching and working with students. Although competence is considered one of the components of PWA (Ilmarinen 2019 ), the teachers in our research equated professional competence and PWA. In defining it, they failed to recognize that PWA is not merely a measure of learned competencies but an assessment of their quality in terms of fulfilling job demands.

Perceived work ability as the capacity to meet job demands

PWA, understood as the ability to meet the job demands of the teaching profession, is emphasized in the third approach identified within our sample of teachers. This group of teachers does not consider individual capacity separately but always in relation to specific job demands. According to teacher Claudia, PWA means the capacity to perform the job demands associated with teaching: I see it as being able to prepare for the class, having the materials, and being prepared so that I do not waste time and am prepared for students asking questions. It means being able to meet the job requirements . Teachers who adopted this approach were aware of the evolving demands of the teaching profession and view PWA as a dynamic construct that requires ongoing development. For instance, changes in student characteristics over time require the acquisition of new competencies and adaptability to new situations: In my profession, adaptability, the ability to keep up with trends, and, most importantly, context with students are essential because students live in a world that can be quite different with the generation gap. To maintain the ability to understand it a little bit. Alternatively, at least try to understand what they live in and possibly use that in teaching (Danielle). Therefore, from the perspective of these teachers, PWA is the intersection between job requirements and personal predisposition. It involves adapting to changing circumstances, acquiring new competencies, and understanding the students’ context.

Job demands of the teaching profession and their consequences

Based on the interviews, it was revealed that teachers perceive their work as highly demanding and burdensome. The participants reported experiencing a wide array of physical, social, and organizational challenges in their teaching profession. The data analysis further enabled the identification of the nature of the relationships between job demands and other variables, as well as the possible mechanisms of the impact of job demands on teachers’ PWA.

Physical job demands of teaching

Regarding the physical demands of teaching, participants highlighted noise exposure and the dearth of physical activity. According to the participants, teachers endure static workloads or repetitive movements in their profession, which adversely affect their musculoskeletal system. For instance, Georgina explicated this scenario in an interview: We have relatively few natural movements unless you are a PE teacher . During the interviews, teachers acknowledged that their job profile had undergone a significant change in recent years, with their working hours being dominated by sitting at computers: We are always sitting at computers. That is the trend. We prepare presentations and write emails (Nadia). However, teachers in our research considered working in noisy environments more serious: You are always in noise. There is constant noise in the classroom or during breaks. Or, in the dining room, it buzzes like a beehive (Cathy). For some participants, working in a noisy environment is not only burdensome, but they also have to regulate the intensity of noise in the classroom or corridors by directing the students’ behavior. Thus, the physical job demands can result in emotional job demands associated with the social aspects of the teaching profession.

Aging teachers in our study, in particular, perceived physical job demands as stressors that negatively impacted their physical and mental well-being. Consequently, this led to a reduction in their ability to meet job demands effectively. Based on findings among participants, it appears that the adverse physical job demands of teaching deteriorate the teachers’ health. However, these unfavorable physical job demands do not appear to cause a decline in PWA directly. Instead, they do so indirectly through the harmful outcomes of stress and impaired health.

Social and emotional job demands of teaching

The second category of job demands pertains to the social and emotional aspects of teaching. According to the participants, teachers engage in various social interactions that differ in their level and nature, which can be challenging to master effectively. For instance, Georgina finds communication with actors in the school environment stressful, emotionally and mentally exhausting, and detrimental to their health: Being a teacher is a lot about direct contact. There are so many connections, so that is challenging and affects your health . Furthermore, coping with challenging interactions with students and parents was more demanding for the aging teachers in our study. Age could be a factor in this, as aging teachers become less capable of adapting to new job demands.

The interviews we conducted with middle and senior-generation teachers revealed their skepticism, and perhaps resistance, toward the current generation of students. This group of educators perceived the changing characteristics and needs of their students as a burden due to increased communication demands and misunderstandings: I sometimes do not understand the contemporary students because they have different values than I do. They have a completely different setting. It bothers me that they do not mind not knowing anything, that they should turn in assignments on time, and that there are rules that are followed (Frances). Participants emphasized the importance of developing social competencies to adapt to the changing students. The interviews with teachers indicated that a teaching job requires constantly maintaining and developing professional competencies. Nevertheless, this need becomes a job demand only when teachers face obstacles in acquiring the requisite skills to perform their duties effectively. The consequences found among our participants include decreased work motivation and disruption of personal resources, as failing to develop new professional competencies generates feelings of insecurity and doubts about professional qualities. Moreover, we have found that the decline in personal resources has other consequences. Interviews with teachers clearly showed that personal resources have the potential to buffer the adverse effects of job demands on health by reducing job-related stress.

In our research, teachers across different generations perceived parental involvement and communication with parents as burdensome and significant sources of job-related stress. It appeared that working with parents was more demanding for our teachers than working with students: I have never had such trouble with students as I experienced with their parents (Ellen). Although teachers have made attempts to comprehend parents, interview findings revealed that the teacher-parent relationship has deteriorated in recent years, leading to increased demands in communication. Our research has identified the attitudes of parents toward teachers’ work as an additional contributing factor. Some teachers in our sample perceived a lack of respect for their teaching authority from parents, who excessively interfere with their autonomy in teaching: Parents think that they can have a say in everything and that we will do our job the way they tell us to do it. I also do not advise my student’s mother, who works as a shop assistant, on how to sell, whether she is doing it right or wrong (Frances). Lack of respect from parents for teachers as professionals and the tendency to question their expertise have significant implications. Within our study, we observed that parents’ attitudes toward teachers contributed to interpersonal conflicts, subsequently leading to job stress, threatening feelings of professional inadequacy, and disrupting professional identity.

Teachers also considered managing student discipline and addressing student misbehavior as challenging job demands. These responsibilities served as stressors for teachers and had detrimental effects their health: I know from colleagues and myself that when there are really naughty classes, and some students can be naughty a lot, you go into that class feeling sick to your stomach, sick at heart, and you tell yourself: “Just survive.” (Ellen). Teachers regarded managing classroom discipline one of the most challenging job demands. Instances of being unable to address student misbehavior effectively evoked feelings of professional inadequacy and led to a depletion of personal resources. Nonetheless, notable differences were observed among the teachers in our sample concerning their interpretation of inappropriate student behavior. Therefore, we found that there are probably differences among teachers in how they perceive social and emotional job demands.

Organizational job demands of teaching

A homogenous group of job demands found in our research were the organizational aspects of the teaching job. In the interviews, teachers highlighted the unfavorable arrangement of working hours as a significant job demand. Teachers reported that they often teach with short breaks between lessons, filled with other responsibilities. Within the Czech context, teachers commonly carry out regular supervision of students in corridors or lunchrooms during their breaks, which is perceived as an onerous workload. As a result, teachers in our study were often deprived of adequate time for rest and personal hygiene during their working hours: During the five-minute break, the teacher is happy to grab teaching aids and run to the next lesson (Bára) . You usually have only two breaks and do not even get to the bathroom because someone always wants something from you, or the bathroom is occupied (Georgina). The inadequate organization of teachers’ work, characterized by short breaks between lessons, has been associated with irregular or insufficient eating and drinking habits. Our data revealed that such improper work organization not only impacts the regimen of teachers but also contributes to heightened stress levels due to a rush during breaks, increased fatigue and exhaustion from insufficient rest during the day, and leads to health issues and a decline in PWA.

Implications of job demands on non-work domains

Teachers in the Czech Republic are permitted to carry out specific work tasks from their homes. These tasks may include creating learning materials and assignments and grading and evaluating students’ work. However, teachers in our sample did not view working from home as a benefit but rather as a necessity driven by the significant job demands of the teaching profession. In order to cope with their daily job responsibilities and tasks, participants often found themselves compelled to continue working after they return home from school, frequently utilizing their leisure time and working beyond regular working hours: I come to school at the latest at six or seven o’clock in the morning so that I can cover everything. And anyway, I bring my work home (Barbara). For teachers who do part of their work from home, it was difficult to distinguish between work and non-work time. The identified reason is that if a teacher embraces the option of working from home, the work is no longer strictly confined to designated working hours. Furthermore, they felt a sense of obligation to be consistently available to fulfill job requirements whenever the need arises. The high responsibility and job commitment were particularly noticeable among the aging teachers: If someone calls me from school at 7 or 8 p.m., I pick up the phone. It is my free time, but if I am not doing anything else important, there is no reason why I should not pick up the phone and switch to work mode (Cathy). Working from home, as a specific organizational aspect of a teacher’s job, was associated with adverse consequences for individuals because they did not have the opportunity to recover and gain physical and mental energy. Therefore, for teachers in our study, working from home tended to be perceived more as a job demand.

Several teachers in our research acknowledged the difficulties they face in finding and achieving a work-life balance, primarily due to the demanding nature of their job. In our sample, this challenge was especially pronounced for teachers belonging to the sandwich generation, who must simultaneously care for underage children and aging family members alongside their work responsibilities. However, it was also related to aging teachers who care for their elderly parents. Balancing caregiving obligations with work not only depleted their energy resources and reduced their available rest time after work but also served as a barrier to meeting job demands, thereby amplifying job-related stress: It causes me stress and frustration, it bothers me. I cannot refuse to work for the school. It is my job. But time is finite and I struggle to divide it between my family, friends, and leisure (Hannah). The inadequate separation between job responsibilities and leisure time, leading to a poor work-life balance, often contributed in the participants to misunderstandings among family members and subsequently results in work-family conflicts: Then my husband interjects that I cannot organize my work when I have to haul my work home (Gabriella).

Interviews with participants revealed that the combination of high job demands and caregiving responsibilities led to increased stress levels, affected the overall workload (employment and caregiving), and left teachers with inadequate opportunities to rest after work and a sense of depletion. The consequence was impaired physical or mental health and decreased PWA. In this context, it is essential to highlight that job stress among participants in our study was not solely attributable to job demands but also arose from caregiving responsibilities. More specifically, caregiving responsibilities indirectly contributed to job stress by impeding teachers’ capacity to meet job demands due to their non-work burdens.

The responsibility for promoting WA rests not only on head teachers and supervisors but also on each teacher. We believe that to maintain and develop their WA, teachers need to have a proper understanding of this construct. Hence, the present study aimed to investigate teachers’ understanding of PWA. Our study discovered that a substantial portion of teachers involved in our research were unfamiliar with conceptualizing PWA as a balance between personal resources and job demands or the ability to meet the job demands specific to the teaching profession (Gould et al. 2008 ; Ilmarinen 2009 ; Ilmarinen et al. 2008 ). The perspectives shared by participants in the interviews indicated that they tended to focus only on specific dimensions of PWA outlined in the Work Ability House, specifically physical and mental health and professional competencies (Ilmarinen 2019 ). However, some qualitative studies have shown that although health-related issues and job skills are closely related to WA, these variables are not PWA per se but PWA hindrances (McGonagle et al. 2022 ). This suggests a lack of awareness or understanding of the comprehensive nature of the PWA construct among teachers in our research. We posit that the findings in our study stem from the inconsistent definitions of WA found in the literature (Cadiz et al. 2019 ). The critical analysis of the WA construct (Tengland 2011 ) revealed that different authors define WA using diverse characteristics such as health, qualifications, professional competencies, motivation, attitudes, values, and occupational virtues. The lack of agreement in defining WA in the literature and the subsequent misperceptions of the PWA construct by teachers identified in our research might hinder teachers’ strategies in maintaining or promoting their PWA. Therefore, we recommend clarifying PWA to the teachers as an individual’s self-perception or evaluation of their physical and mental capacity to continue working in the teaching profession, given the characteristics of the job demands, job resources, and personal resources.

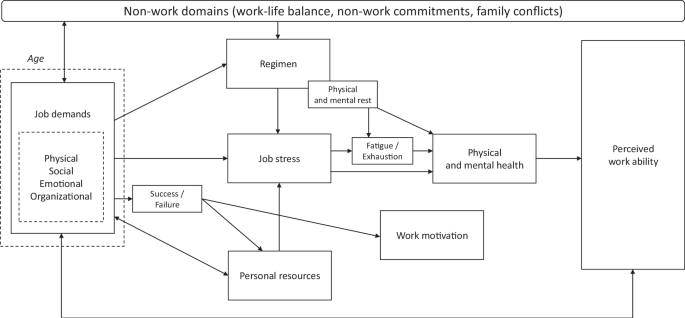

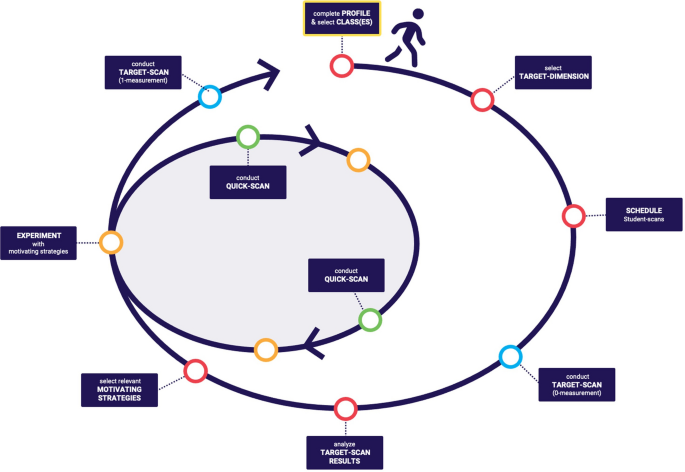

The emic perspective of the teachers was used to identify the mechanisms by which specific aspects of the teaching profession are reflected in teachers’ PWA (Fig. 1 ). In our sample, the physical, social, emotional, and organizational job demands were associated with both physical and psychological costs that teachers incurred in fulfilling them. Job demands are one of the crucial determinants that affect WA (Kunz and Millhoff 2023 ). In the scope of the present study, job demands have been shown to affect PWA rather indirectly. If participants perceived the job demands as too high and burdensome, or if they experienced obstacles meeting them, this usually increased their job stress. If job distress was not reduced appropriately, it subsequently manifested in fatigue, exhaustion, and impaired physical or mental health, making it difficult or impossible for teachers to meet job requirements and thus adversely affecting their PWA. Hence, the mechanism identified in our qualitative study corresponds to the health impairment process captured in the revised JD-R model (Bakker and Demerouti 2007 ; Demerouti et al. 2001 ).

Identified relationships between variables.

Through participant responses, it became evident that teaching is a highly stressful and debilitating occupation, as reported in other research (Herman et al. 2020 ; Mäkelä et al. 2015 ). The present study offers insights into differentiating job stress and exhaustion among teachers as distinct constructs. Teachers in our study perceived job stress as an internal state characterized by heightened tension when faced with excessive or burdensome job demands that surpass their ability to meet them. Thus, as the JD-R model assumes, teachers’ job stress resulted from job demands (Bakker and Demerouti 2007 ). Our study revealed that teachers considered exhaustion a consequence of physical or mental fatigue resulting from prolonged stress or lack of adequate rest. Since the JD-R model includes constructs such as strain and burnout (Bakker and Demerouti 2007 ; Schaufeli and Bakker 2004 ), the distinct perceptions of job stress and exhaustion among teachers in our sample emphasize the need for a more precise differentiation in the JD-R model to provide a more accurate depiction of the health impairment process. In addition, the present study contributes to the existing literature by finding that job stress did not necessarily cause fatigue and exhaustion among teachers in our study, as some previous research has shown (e.g., Wang et al. 2015 ). In the view of our participants, prolonged job stress directly impacted the development of health complaints, highlighting the need for a distinct compensatory mechanism beyond fatigue reduction.

By examining the specific experiences of the participants, we uncovered new insights into the health impairment process embedded and outlined in the revised JD-R model (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004 ). First, organizational job demands were found to disrupt teachers’ routines, resulting in inadequate personal hygiene, unhealthy eating habits, and insufficient rest. These factors directly or indirectly contributed to health deterioration. Second, teachers were often confronted with challenging job demands encroaching on their non-working hours. The disruption of non-work life by work-related tasks impaired the crucial time dedicated to rest and recharging, generated family tensions, and thus adversely affected teachers’ health. Therefore, achieving a work-life balance is paramount as a strategic approach to mitigate the deleterious impact of heightened job demands on PWA through exhaustion and the deterioration of both physical and mental health among educators (Gragnano et al. 2020 ; Sirgy and Lee 2018 ). These findings highlight a notable constraint of the JD-R model, which primarily concentrates on work-related aspects (McGonagle et al. 2022 ). Our empirical evidence indicated that work and family are essential life domains, and balance between these two domains is crucial for PWA. In this regard, our findings align with other quantitative studies that have established a relationship between work-family or work-life balance and WA (Abdelrehim et al. 2023 ; Berglund et al. 2021 ). Our research showed that the work and non-work domains are intricately intertwined and cannot be examined separately. Thus, a necessity arises for designing and verifying a more inclusive framework encompassing organizational and individual factors across both work and non-work realms to investigate teachers’ PWA effectively (cf. McGonagle et al. 2022 ).

The job demands of the teaching profession were frequently negatively associated with PWA in our research, consistent with their definition in the JD-R model (Demerouti et al. 2001 ) and the results of the previous meta-analysis (Brady et al. 2020 ). However, interviews with teachers indicated the conceptual ambiguities between the constructs of job demands and job resources, which were pointed out in a critical review of the JD-R model (Schaufeli and Taris 2014 ). Our findings suggest that job demands within the teaching profession may exhibit a dual nature, not solely yielding adverse effects but also serving as catalysts for personal growth, learning, and development. Thus, depending on the context, job demands can also act as job resources (cf. Schaufeli and Taris 2014 ). More specifically, job demands challenged or stimulated our teachers to overcome obstacles and develop professional competencies. Moreover, our findings present an opportunity for further research. This research should address whether job demands can also serve as job resources, as our qualitative data suggests. Alternatively, it can explore the validity of the interaction hypothesis (Bakker and Demerouti 2007 ; Bakker et al. 2007 ). According to this hypothesis, the motivational effect of job demands should be accompanied by the corresponding job resources.

The experience of success or failure in coping with job demands emerged as a pivotal milestone in this context. More specifically, achieving professional success eliminated the negative impact of job demands for our participants and engendered the growth of personal resources. These personal resources, in turn, acted as protective factors against the detrimental effects of job demands on health by mitigating job-related stress. While previous research (Xanthopoulou et al. 2007 ) has not yielded evidence supporting the moderating role of personal resources in the relationship between job demands and exhaustion, our study suggested that educators with more personal resources demonstrate an enhanced capacity to effectively cope with demanding job responsibilities. This, in turn, helps avert adverse job outcomes, such as heightened job stress, exhaustion, and health complications. Hence, our findings derived from interviews with fourteen teachers supported the assumption of the JD-R model, wherein personal resources influence the perception of job demands and buffer against the deleterious effects of job demands on burnout (Schaufeli and Taris 2014 ).

The main strength of the present study lies in its utilization of a qualitative methodology to explore teachers’ perceptions of WA and the underlying mechanisms through which job demands influence their PWA. We believe we have successfully identified how teachers perceive and interpret WA, capturing the intricate details of the impact of job demands on teachers’ PWA that are challenging to capture through a quantitative approach. Our findings revealed a limited awareness among teachers regarding the holistic nature of WA and the necessity to disseminate information about this construct to teachers. This study provides empirical evidence supporting the incorporation of PWA into the JD-R model as an outcome influenced negatively by job demands (cf. Brady et al. 2020 ; Schaufeli and Taris 2014 ). We contributed to the literature by seeking to expand beyond known predictors of PWA through an inductive approach. Specifically, job demands have been shown to indirectly influence PWA through the health impairment process (Bakker and Demerouti 2007 ; Demerouti et al. 2001 ). Among our participants, high job demands contributed to job stress, resulting in fatigue, physical or mental health impairment, and reduced PWA. Furthermore, our study offered specific examples illustrating how challenging job demands lead to work-family and work-life conflicts, negatively impacting teachers’ WA. Thus, adopting an inductive approach enabled us to identify and elucidate additional factors contributing to PWA, extending beyond the purview of the revised JD-R model.

Practical implications

Our research offers insights with practical implications for supporting and enhancing the PWA of teachers. Given the qualitative nature of our study, we are formulating recommendations specifically tailored for the participants and the head teachers in the schools where our study participants work. However, with caution, the practical implications may be considered applicable to other teachers with characteristics similar to those in our sample.

As some teachers in our research lacked a clear understanding of the WA concept, we deem it necessary to initiate an informational process to introduce them to this crucial concept. We consider teachers’ knowledge and understanding of the WA concept vital, as it serves as a prerequisite for them to take responsibility for maintaining their WA. Head teachers, in particular, can play a pivotal role in this initiative by organizing workshops, lectures, or educational programs for their staff. Additionally, providing articles, infographics, leaflets, and online resources to promote WA could be beneficial.

Teachers in our sample expressed concerns about their unhealthy lifestyle, influenced by physical, social, and organizational job demands, as well as the workplace environment. Head teachers have several avenues to encourage healthy lifestyles among their teaching staff. For instance, teachers in our research complained about insufficient time for rest during the teaching day. Head teachers can ensure adequate break times for teachers to rest, refresh, hydrate, and maintain hygiene. Non-teaching staff could be designated to monitor students in corridors during breaks, releasing teachers from this duty and allowing them more time for rest. Addressing specific complaints from our study, head teachers may consider introducing one-hour breaks for teachers in the teaching schedule. Additionally, concerns about long periods of sitting at computers and noise at school can be mitigated by providing ergonomic desks and chairs and implementing technical solutions to improve acoustics in classrooms and corridors. However, teachers also bear responsibility for their physical and mental health and WA. Hence, teachers should adhere to fundamental principles of a healthy lifestyle, including maintaining healthy eating habits, engaging in physical and mental exercises, maintaining optimal body weight, participating in regular medical examinations, avoiding substance abuse, and ensuring sufficient and high-quality sleep (cf. Airila et al. 2012 ; Garzaro et al. 2019 ).

Our study revealed that teachers’ WA was adversely affected by the social and emotional job demands of their teaching roles, particularly in communication challenges with parents and addressing student discipline. Our study emphasizes the importance of teachers focusing on developing their communication soft skills. Additionally, we recommend that teachers seek support from school leaders and co-workers (Taris et al. 2017 ), emphasizing that individual teachers should not navigate challenging interactions with parents or students alone. In practice, effective strategies include collaborative efforts such as teamwork with other teachers and school counselors, participating in teacher-sharing sessions, or involving school management in problematic meetings with parents and students.

It became evident among our participants that teaching work had an adverse impact on their family and private lives, highlighting the importance of supporting their work-life balance. Various studies have shown that work-life balance can be influenced by organizational programs designed to assist employees in managing the demands of both their job and personal lives (Sirgy and Lee, 2018 ). To support teachers, head teachers can implement organizational measures such as regular workload reviews, flexible work arrangements, part-time work options, assistance with childcare, access to parenting resources, eldercare resources, and family leave policies (Sirgy and Lee 2018 ). Based on insights from our participant interviews, it is apparent that head teachers should prioritize addressing the needs of caregivers establishing effective workplace policies to help them reconcile their caregiving and teaching roles (Pavalko and Henderson 2006 ). Adopting time management principles and fostering the ability to seek social support when needed can be effective strategies for individual teachers.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when reading and interpreting the results. First, the sample used in qualitative research may not be representative of the larger population. This study recruited teachers from those interested in the Towards Successful Seniority training program, potentially leading to a sample bias. It is possible that teachers with a particular inclination towards prioritizing their health, adopting a healthy lifestyle, and seeking strategies to overcome work-related challenges were overrepresented in the sample. Second, the data collected in this study solely reflect the subjective perspectives of a limited number of teachers. Therefore, caution should be exercised when attempting to transfer the findings to the broader population of teachers. Third, researchers may have been influenced by their own biases or expectations, which could have influenced the formulation of interview questions, data analysis, or the interpretation of results. Lastly, the study focused specifically on upper secondary teachers in the Czech Republic, which restricts the transferability of the findings to other teacher groups and cultural contexts. Recognizing the need for caution when extrapolating the results to different settings or educational systems is essential.

Despite these limitations, our study represents one of the initial endeavors to explore in-depth the potential antecedents of PWA within the framework of the JD-R model. The insights gained from this study contribute to the existing body of literature and lay the groundwork for further research on PWA among teachers.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MMYUJU .

When we refer to teachers, we are specifically addressing the participants in our study, not teachers as a general population.

Abdelrehim MG, Eshak ES, Kamal NN (2023) The mediating role of work–family conflicts in the association between work ability and depression among Egyptian civil workers. J Public Health 45(2):e175–e183. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdac061

Article CAS Google Scholar

Airila A, Hakanen J, Punakallio A, Lusa S, Luukkonen R (2012) Is work engagement related to work ability beyond working conditions and lifestyle factors? Int Arch Occup Environ Health 85:915–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-012-0732-1

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Airila A, Hakanen J, Schaufeli WB, Luukkonen R, Punakallio A, Lusa S (2014) Are job and personal resources associated with work ability 10 years later? Work Stress 28(1):87–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2013.872208

Article Google Scholar

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2007) The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J Manag Psychol 22(3):309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker AB, Hakanen JJ, Demerouti E, Xanthopoulou D (2007) Job resources boost work engagement particularly when job demands are high. J Educ Psychol 99(2):274–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.274

Berglund E, Anderzén I, Andersén Å et al. (2021) Work-life balance predicted work ability two years later: a cohort study of employees in the Swedish energy and water sector. BMC Public Health 21(1):1212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11235-4

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bogaert I, De Martelaer K, Deforche B, Clarys P, Zinzen E (2014) Associations between different types of physical activity and teachers’ perceived mental, physical, and work-related health. BMC Public Health 14:534. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-534

Brady GM, Truxillo DM, Cadiz DM, Rineer JR, Caughlin DE, Bodner T (2020) Opening the black box: Examining the nomological network of work ability and its role in organizational research. J Appl Psychol 105(6):637–670. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000454

Cadiz DM, Brady G, Rineer JR, Truxillo DM (2019) A review and synthesis of work ability literature. Work Aging Retire 5(1):114–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/way010

Cloostermans L, Bekkers MB, Uiters E, Proper KI (2015) The effectiveness of interventions for ageing workers on (early) retirement, work ability and productivity: A systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 88(5):521–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-014-0969-y

Charmaz K (2014) Constructing grounded theory. Sage Publications

Corbin J, Strauss A (2014) Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications

de Alcantara MA, de Medeiros AM, Claro RM, de Toledo Vieira M (2019) Determinants of teachers’ work ability in basic education in Brazil: Educatel Study, 2016. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 35(Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00179617

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB (2001) The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 86(3):499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Demerouti E, Bakker AB (2006) The job demands-resources model: challenges for future research. SA J Ind Psychol 37(2):1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974

Erick PN, Smith DR (2011) A systematic review of musculoskeletal disorders among school teachers. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12:260. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-260

Freyer M, Formazin M, Rose U (2019) Factorial validity of the work ability index among employees in Germany. J Occup Rehabil 29:433–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9803-9

Garzaro G, Sottimano I, Di Maso M et al. (2019) Work Ability among Italian Bank Video Display Terminal Operators: Socio-Demographic, Lifestyle, and Occupational Correlates. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(9):1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091653

Gould R, Ilmarinen J, Järvisalo J, Koskinen S (2008) Dimensions of work ability: Results of the Health 2000 Survey. Wassa Graphic Oy, Helsinki

Gragnano A, Simbula S, Miglioretti M (2020) Work–life balance: Weighing the importance of work–family and work–health balance. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030907

Guidetti G, Viotti S, Bruno A, Converso D (2018) Teachers’ work ability: a study of relationships between collective efficacy and self-efficacy beliefs. Psychol Res Behav Manag 11:197–206. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S157850

Hakanen JJ, Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB (2006) Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J Sch Psychol 43(6):495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

Herman KC, Reinke WM, Eddy CL (2020) advances in understanding and intervening in teacher stress and coping: The coping-competence-context theory. J Sch Psychol 78:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.01.001

Hlaďo P, Dosedlová J, Harvánková K et al. (2020) Work ability among upper-secondary school teachers: examining the role of burnout, sense of coherence, and work-related and lifestyle factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(24):9185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249185

Hlaďo P, Pokorný B, Petrovová M (2017) Work ability of the Czech workforce aged 50+ and the relationship between selected demographic and anthropometric variables. Kontakt 19:e145–e155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kontakt.2017.05.001

Hobfoll SE (2002) Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev Gen Psychol 6(4):307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307

Ilmarinen J, Gould R, Järvikoski A, Järvisalo J (2008) Diversity of work ability. In: Gould R, Ilmarinen J, Jarvisalo J, Koskinen S (eds) Dimensions of work ability: results of the Health 2000 Survey. FIOH, p 13–24

Ilmarinen J, Tuomi K, Eskelinen L, Nygård C-H, Huuhtanen P, Klockars M (1991) Summary and recommendations of a project involving cross-sectional and follow-up studies on the aging worker in Finnish municipal occupations (1981–1985). Scand J Work Environ Health 17:135–141

PubMed Google Scholar

Ilmarinen J, Tuomi K, Klockars M (1997) Changes in the work ability of active employees over an 11-year period. Scand J Work Environ Health 23:49–57. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40966691

Ilmarinen J (2019) From work ability research to implementation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(16):2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162882

Ilmarinen J (2009) Work ability—a comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention. Scand J Work Environ Health 35:1–5. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1304

Kunz C, Millhoff CA (2023) A longitudinal perspective on the interplay of job demands and destructive leadership on employees’ work ability in Germany. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 96:735–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-023-01962-z

Langseth-Eide B (2019) It’s been a hard day’s night and I’ve been working like a dog: workaholism and work engagement in the JD-R Model. Front Psychol 10:1444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01444

Leijon O, Balliu N, Lundin A, Vaez M, Kjellberg K, Hemmingsson T (2017) Effects of psychosocial work factors and psychological distress on self-assessed work ability: A 7-year follow-up in a general working population. Am J Ind Med 60(1):121–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22670

Li H, Liu Z, Liu R, Li L, Lin A (2016) The relationship between work stress and work ability among power supply workers in Guangdong, China. BMC Public Health 16:123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2800-z

Mäkelä K, Hirvensalo M, Whipp P (2015) Determinants of PE teachers career intentions. J Teach Phys Educ 34(4):680–699. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2014-0081

McGonagle AK, Bardwell T, Flinchum J, Kavanagh K (2022) Perceived work ability: a constant comparative analysis of workers’ perspectives. Occup Health Sci 6:207–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-022-00116-w

McGonagle AK, Fisher GG, Barnes-Farrell JL, Grosch JW (2015) Individual work factors related to perceived work ability and labor force outcomes. J Appl Psychol 100(2):376–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037974

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Sage Publications

Pavalko EK, Henderson KA (2006) Combining care work and paid work: do workplace policies make a difference? Res Aging 28(3):359–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027505285848

Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB (2004) Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J Organ Behav 25:293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli WB, Taris TW (2014) A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In: Bauer GF, Hämmig O (eds) Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: a transdisciplinary approach. Springer Science + Business Media, p 43–68

Sirgy MJ, Lee DJ (2018) Work-life balance: an integrative review. Appl Res Qual Life 13(1):229–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9509-8

Sottimano I, Viotti S, Guidetti G, Converso D (2017) Protective factors for work ability in preschool teachers. Occup Med 67(4):301–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqx031

Taris TW, Leisink PL, Schaufeli WB (2017) Applying occupational health theories to educator stress: contribution of the job demands-resources model. In: McIntyre TM, McIntyre SE, Francis DJ (eds) Educator stress: an occupational health perspective. Springer, p 237–259

Tengland PA (2011) The concept of work ability. J Occup Rehabil 21(2):275–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-010-9269-x

Tuomi K, Huuhtanen P, Nykyri E, Ilmarinen J (2001) Promotion of work ability, the quality of work and retirement. Occup Med 51(5):318–324. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/51.5.318

van den Berg TI, Elders LA, de Zwart BC, Burdorf A (2009) The effects of work-related and individual factors on the Work Ability Index. Occup Environ Med 66(4):221–220. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2008.039883

van den Berg TI, Robroek SJ, Plat JF, Koopmanschap MA, Burdorf A (2011) The importance of job control for workers with decreased work ability to remain productive at work. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 84(6):705–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-010-0588-1

Vertanen-Greis H, Loyttyniemi E, Uitti J, Putus T (2022) Work ability of teachers associated with voice disorders, stress, and the indoor environment: a questionnaire study in Finland. J Voice. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.09.022

Wang Y, Ramos A, Wu H et al. (2015) Relationship between occupational stress and burnout among Chinese teachers: A cross-sectional survey in Liaoning, China. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 88(5):589–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-014-0987-9

Wengraf T (2001) Qualitative research interviewing: biographic narrative and semi-structured method s . Sage

Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB (2007) The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int J Stress Manag 14(2):121–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the research project Research on perceived work ability among lower secondary school teachers [grant number GA23-05312S], funded by the Czech Science Foundation and the NPO ‘Systemic Risk Institute’ number LX22NPO5101, funded by European Union—Next Generation EU (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, NPO: EXCELES).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Masaryk University, Faculty of Arts, Brno, Czech Republic

Petr Hlado & Klara Harvankova

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization: P.H.; methodology: P.H. and K.H.; data collection: K.H.; formal analysis: P.H.; funding acquisition: P.H.; writing – original draft: P.H.; writing – review & editing: P.H. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Petr Hlado .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures in this study involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee. Prior to the data collection, the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Masaryk University under the number EKV-2018-045.

Informed consent

Informed consent was given by all participants. Teachers were given the option to contact the research team before, during, and after the data collection and the option to withdraw their consent and stop participating in the research at any time.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hlado, P., Harvankova, K. Teachers’ perceived work ability: a qualitative exploration using the Job Demands-Resources model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11 , 304 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02811-1

Download citation

Received : 11 July 2023

Accepted : 07 February 2024

Published : 23 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02811-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Search Menu

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C38 - Classification Methods; Cluster Analysis; Principal Components; Factor Models

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C59 - Other

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C80 - General

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- C83 - Survey Methods; Sampling Methods

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F01 - Global Outlook

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F19 - Other

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F52 - National Security; Economic Nationalism

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F63 - Economic Development

- F66 - Labor

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- H27 - Other Sources of Revenue

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- H43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount Rate

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H61 - Budget; Budget Systems

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H83 - Public Administration; Public Sector Accounting and Audits

- H84 - Disaster Aid

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions