- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Brown v. Board of Education

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 27, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was a landmark 1954 Supreme Court case in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. Brown v. Board of Education was one of the cornerstones of the civil rights movement, and helped establish the precedent that “separate-but-equal” education and other services were not, in fact, equal at all.

Separate But Equal Doctrine

In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racially segregated public facilities were legal, so long as the facilities for Black people and whites were equal.

The ruling constitutionally sanctioned laws barring African Americans from sharing the same buses, schools and other public facilities as whites—known as “Jim Crow” laws —and established the “separate but equal” doctrine that would stand for the next six decades.

But by the early 1950s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ) was working hard to challenge segregation laws in public schools, and had filed lawsuits on behalf of plaintiffs in states such as South Carolina, Virginia and Delaware.

In the case that would become most famous, a plaintiff named Oliver Brown filed a class-action suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in 1951, after his daughter, Linda Brown , was denied entrance to Topeka’s all-white elementary schools.

In his lawsuit, Brown claimed that schools for Black children were not equal to the white schools, and that segregation violated the so-called “equal protection clause” of the 14th Amendment , which holds that no state can “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The case went before the U.S. District Court in Kansas, which agreed that public school segregation had a “detrimental effect upon the colored children” and contributed to “a sense of inferiority,” but still upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Brown v. Board of Education Verdict

When Brown’s case and four other cases related to school segregation first came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court combined them into a single case under the name Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka .

Thurgood Marshall , the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, served as chief attorney for the plaintiffs. (Thirteen years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson would appoint Marshall as the first Black Supreme Court justice.)

At first, the justices were divided on how to rule on school segregation, with Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson holding the opinion that the Plessy verdict should stand. But in September 1953, before Brown v. Board of Education was to be heard, Vinson died, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower replaced him with Earl Warren , then governor of California .

Displaying considerable political skill and determination, the new chief justice succeeded in engineering a unanimous verdict against school segregation the following year.

In the decision, issued on May 17, 1954, Warren wrote that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” as segregated schools are “inherently unequal.” As a result, the Court ruled that the plaintiffs were being “deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.”

Little Rock Nine

In its verdict, the Supreme Court did not specify how exactly schools should be integrated, but asked for further arguments about it.

In May 1955, the Court issued a second opinion in the case (known as Brown v. Board of Education II ), which remanded future desegregation cases to lower federal courts and directed district courts and school boards to proceed with desegregation “with all deliberate speed.”

Though well intentioned, the Court’s actions effectively opened the door to local judicial and political evasion of desegregation. While Kansas and some other states acted in accordance with the verdict, many school and local officials in the South defied it.

In one major example, Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas called out the state National Guard to prevent Black students from attending high school in Little Rock in 1957. After a tense standoff, President Eisenhower deployed federal troops, and nine students—known as the “ Little Rock Nine ”— were able to enter Central High School under armed guard.

Impact of Brown v. Board of Education

Though the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board didn’t achieve school desegregation on its own, the ruling (and the steadfast resistance to it across the South) fueled the nascent civil rights movement in the United States.

In 1955, a year after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. Her arrest sparked the Montgomery bus boycott and would lead to other boycotts, sit-ins and demonstrations (many of them led by Martin Luther King Jr .), in a movement that would eventually lead to the toppling of Jim Crow laws across the South.

Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , backed by enforcement by the Justice Department, began the process of desegregation in earnest. This landmark piece of civil rights legislation was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 .

Runyon v. McCrary Extends Policy to Private Schools

In 1976, the Supreme Court issued another landmark decision in Runyon v. McCrary , ruling that even private, nonsectarian schools that denied admission to students on the basis of race violated federal civil rights laws.

By overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine, the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education had set the legal precedent that would be used to overturn laws enforcing segregation in other public facilities. But despite its undoubted impact, the historic verdict fell short of achieving its primary mission of integrating the nation’s public schools.

Today, more than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education , the debate continues over how to combat racial inequalities in the nation’s school system, largely based on residential patterns and differences in resources between schools in wealthier and economically disadvantaged districts across the country.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

History – Brown v. Board of Education Re-enactment, United States Courts . Brown v. Board of Education, The Civil Rights Movement: Volume I (Salem Press). Cass Sunstein, “Did Brown Matter?” The New Yorker , May 3, 2004. Brown v. Board of Education, PBS.org . Richard Rothstein, Brown v. Board at 60, Economic Policy Institute , April 17, 2014.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- Introduction to the Civil Rights Movement

- African American veterans and the Civil Rights Movement

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- Emmett Till

- The Montgomery Bus Boycott

- "Massive Resistance" and the Little Rock Nine

- The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- SNCC and CORE

- Black Power

- The Civil Rights Movement

- In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) a unanimous Supreme Court declared that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

- The Court declared “separate” educational facilities “inherently unequal.”

- The case electrified the nation, and remains a landmark in legal history and a milestone in civil rights history.

A segregated society

The brown v. board of education case, thurgood marshall, the naacp, and the supreme court, separate is "inherently unequal", brown ii: desegregating with "all deliberate speed”, what do you think.

- James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 387.

- James T. Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 25-27.

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 387.

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 32.

- See Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, and Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality (New York: Knopf, 2004).

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 43-45.

- Supreme Court of the United States, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

- Patterson, Grand Expectations, 394-395.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

Brown v. Board of Education

Following is the case brief for Brown v. Board of Education, United States Supreme Court, (1954)

Case Summary of Brown v. Board of Education:

- Oliver Brown was denied admission into a white school

- As a representative of a class action suit, Brown filed a claim alleging that laws permitting segregation in public schools were a violation of the 14 th Amendment equal protection clause .

- After the District Court upheld segregation using Plessy v. Ferguson as authority, Brown petitioned the United States Supreme Court.

- The Supreme Court held that segregation had a profound and detrimental effect on education and segregation deprived minority children of equal protection under the law.

Brown v. Board of Education Case Brief

Statement of Facts:

Oliver Brown and other plaintiffs were denied admission into a public school attended by white children. This was permitted under laws which allowed segregation based on race. Brown claimed that the segregation deprived minority children of equal protection under the 14 th Amendment. Brown filed a class action, consolidating cases from Virginia, South Carolina, Delaware and Kansas against the Board of Education in a federal district court in Kansas.

Procedural History:

Brown filed suit against the Board of Education in District Court. After the District Court held in favor of the Board, Brown appealed to the United States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Issues and Holding:

Does the segregation on the basis of race in public schools deprive minority children of equal educational opportunities, violating the 14 th Amendment? Yes.

The Court Reversed the District Court’s decision.

Rule of Law or Legal Principle Applied:

Separating educational facilities based on racial classifications is unequal in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14 th Amendment.

The Court held that looking to historical legislation and prior cases could not yield a true meaning of the 14 th Amendment because each is inconclusive.

At the time the 14 th Amendment was enacted, almost no African American children were receiving an education. As such, trying to determine the historical intentions surrounding the 14 th Amendment is not helpful. In addition, few public schools existed at the time the amendment was adopted.

Analyzing the text of the amendment itself is necessary to determine its true meaning. The Court held the basic language of the Amendment suggests the intent to prohibit all discriminatory legislation against minorities.

Despite the fact each facility is essentially the same, the Court held it was necessary to examine the actual effect of segregation on education. Over the past few years, public education has turned into one of the most valuable public services both state and local governments have to offer. Since education has a heavy bearing on the future success of each child, the opportunity to be educated must be equal to each student.

The Court stated that the opportunity for education available to segregated minorities has a profound and detrimental effect on both their hearts and minds. Studies showed that segregated students felt less motivated, inferior and have a lower standard of performance than non-minority students. The Court explicitly overturned Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 U.S. 537 (1896), stating that segregation deprives African-American students of equal protection under the 14 th Amendment.

Concurring/ Dissenting opinion :

Unanimous decision led by Justice Warren.

Significance:

Brown v. Board of Education was the landmark case which desegregated public schools in the United States. It abolished the idea of “ separate but equal .”

Student Resources:

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/rights/landmark_brown.html https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/347/483

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits states from segregating public school students on the basis of race. This marked a reversal of the "separate but equal" doctrine from Plessy v. Ferguson that had permitted separate schools for white and colored children provided that the facilities were equal.

Based on an 1879 law, the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas operated separate elementary schools for white and African-American students in communities with more than 15,000 residents. The NAACP in Topeka sought to challenge this policy of segregation and recruited 13 Topeka parents to challenge the law on behalf of 20 children. In 1951, each of the families attempted to enroll the children in the school closest to them, which were schools designated for whites. Each child was refused admission and directed to the African-American schools, which were much further from where they lived. For example, Linda Brown, the daughter of the named plaintiff, could have attended a white school several blocks from her house but instead was required to walk some distance to a bus stop and then take the bus for a mile to an African-American school. Once the children had been refused admission to the schools designated for whites, the NAACP brought the lawsuit. They were unsuccessful at the trial court level, where the 1896 Supreme Court precedent in Plessy v. Ferguson was found to be decisive. Even though the trial court agreed that educational segregation had a negative effect on African-American children, it applied the standard of Plessy in finding that the white and African-American schools offered sufficiently equal quality of teachers, curricula, facilities, and transportation. Since the NAACP did not challenge the details of those findings, it essentially cast the appeal as a direct challenge to the system imposed by Plessy. When the Supreme Court heard the appeal, it combined Brown with four other cases addressing parallel issues in South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and Washington, D.C. The NAACP was responsible for bringing each of these lawsuits, and it had lost on each of them at the trial court level except the Delaware case of Gebhart v. Belton. Brown stood apart from the others in the group as the only case that challenged the separate but equal doctrine on its face. The others were based on assertions of gross inequality, which would have violated the standard in Plessy as well.

- Earl Warren (Author)

- Hugo Lafayette Black

- Stanley Forman Reed

- Felix Frankfurter

- William Orville Douglas

- Robert Houghwout Jackson

- Harold Hitz Burton

- Tom C. Clark

- Sherman Minton

Supreme Court opinions are rarely unanimous, and it appears that Justice Frankfurter deliberately argued for a re-hearing to stall the case while the Court built a consensus behind its decision. This was designed to prevent proponents of segregation from using dissents to build future challenges to Brown. Despite the eventual unanimity, the judges had a wide range of views. Reed and Clark were not opposed to segregation per se, while Frankfurter and Jackson were hesitant to issue a bold decision that might be difficult to enforce. (Jackson and Reed initially planned to write a dissent together.) Douglas, Black, Burton, and Minton were relatively ready to overturn Plessy from the outset, however, as was Chief Justice Warren. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's appointment of Warren to replace former Chief Justice Frederick Moore Vinson, who died in September 1953, thus may have played a crucial role in how events unfolded. Warren had supported the integration of Mexican-American children into California schools. Warren based much of his opinion on information from social science studies rather than court precedent. This was understandable because few decisions existed on which the Court could rely, yet it would draw criticism for its non-traditional approach. The decision also used language that was relatively accessible to non-lawyers because Warren felt that it was necessary for all Americans to understand its logic.

This decision ranks among the most dramatic issued by the Supreme Court, in part due to Warren's insistence that the Fourteenth Amendment gave the Court the power to end segregation even without Congressional authority. Like the use of non-legal sources to justify his reasoning, Warren's "activist" view of the Court's role remains controversial to the current day. The illegality of segregation does not, however, and a series of later decisions were implemented to try to force states to comply with Brown. Unfortunately, the reality is that this decision's vision of complete desegregation has not been achieved in many areas of the U.S., and the problems of enforcement that Jackson identified have proven difficult to solve.

U.S. Supreme Court

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Argued December 9, 1952

Reargued December 8, 1953

Decided May 17, 1954*

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment -- even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors of white and Negro schools may be equal. Pp. 486-496.

(a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education. Pp. 489-490.

(b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Pp. 492-493.

(c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. P. 493.

(d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal. Pp. 493-494.

(e) The "separate but equal" doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , has no place in the field of public education. P. 495.

(f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees. Pp. 495-496.

- Opinions & Dissents

- Copy Citation

Get free summaries of new US Supreme Court opinions delivered to your inbox!

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

Some case metadata and case summaries were written with the help of AI, which can produce inaccuracies. You should read the full case before relying on it for legal research purposes.

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, supreme court case, brown v. board of education of topeka (1954).

347 U.S. 483 (1954)

“We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Selected by

Caroline Fredrickson

Visiting Professor, Georgetown University Law Center and Senior Fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice

Ilan Wurman

Associate Professor, Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law at Arizona State University

Brown is a consolidated case addressing the constitutionality of school segregation. There, the challengers—African American children and their parents—attacked the “separate but equal” doctrine created in Plessy v. Ferguson . They argued that school segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment by depriving the African American students of equal educational opportunities. In a unanimous decision authored by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Court agreed—overturning Plessy and declaring school segregation unconstitutional. As part of its analysis, the Court cited the negative impact of segregation on children’s mental and emotional development. With this landmark decision, the Court took an important step in desegregating our nation’s schools, opening the door to further legal challenges to Jim Crow laws in other contexts, and reinvigorating the promise of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Read the Full Opinion

Excerpt: Majority Opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren

These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are premised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion.

In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each instance, they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a three-judge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the so-called “separate but equal” doctrine announced by this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson . . . . Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. . . .

The plaintiffs contend that segregated public schools are not “equal” and cannot be made “equal,” and that hence they are deprived of the equal protection of the laws. . . .

In the first cases in this Court construing the Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all state-imposed discriminations against the Negro race. The doctrine of “separate but equal” did not make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, . . . involving not education but transportation. American courts have since labored with the doctrine for over half a century. In this Court, there have been six cases involving the “separate but equal” doctrine in the field of public education. In Cumming v. County Board of Education . . . and Gong Lum v. Rice . . . the validity of the doctrine itself was not challenged. In more recent cases, all on the graduate school level, inequality was found in that specific benefits enjoyed by white students were denied to Negro students of the same educational qualifications. . . . In none of these cases was it necessary to reexamine the doctrine to grant relief to the Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v. Painter . . . , the Court expressly reserved decision on the question whether Plessy v. Ferguson should be held inapplicable to public education.

In the instant cases, that question is directly presented. Here . . . , there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other ‘tangible’ factors. Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education. . . .

Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does. . . .

To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs: “Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law; for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of Negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system.”

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy , this finding is amply supported by modern authority. Any language in Plessy contrary to this finding is rejected.

We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of [equal protection of the laws].

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Help inform the discussion

Brown v. Board of Education

May 17, 1954: The 'separate is inherently unequal' ruling forces Eisenhower to address civil rights

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. . . . We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

In 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote this opinion in the unanimous Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Citing a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, the groundbreaking decision was widely regarded as one of America's most consequential legal judgments of the 20th century, setting the stage for a strong and lasting US Civil Rights Movement. Thurgood Marshall, lead counsel on the case, would go on to become a Supreme Court Justice himself.

The Brown decision reverberated for decades. Determined resistance by whites in the South thwarted the goal of school integration for years. Even though the court ruled that states should move with “all deliberate speed,” that standard was simply too vague for real action. Neither segregationists, who opposed to integration on racist grounds, nor the constitutional scholars who believed the court had overreached were going away without a fight.

President Eisenhower didn't fully support of the Brown decision. The president didn't like dealing with racial issues and failed to speak out in favor of the court's ruling. Although the president usually avoided comment on court decisions, his silence in this case may have encouraged resistance. In many parts of the South, white citizens' councils organized to prevent compliance. Some of these groups relied on political action; others used intimidation and violence.

Despite his reticence, Eisenhower did acknowledge his constitutional responsibility to uphold the Supreme Court’s rulings. In 1957, when mobs prevented the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, Governor Orval Faubus saw political advantages in using the National Guard to block the entry of African American students to Central High. After meeting with Eisenhower, Faubus promised to allow the students to enroll—but then withdrew the National Guard, allowing a violent mob to surround the school. In response, Eisenhower dispatched federal troops, the first time since Reconstruction that a president had sent military forces into the South to enforce federal law.

In explaining his action, however, Eisenhower did not declare that desegregating public schools was the right thing to do. Instead, in a nationally televised address , he asserted that the violence in Little Rock was harming US prestige and influence around the world and giving Communist propagandists an opportunity “to misrepresent our whole nation.” Troops stayed in Little Rock for the entire school year, and in the spring of 1958, Central High had its first African American graduate.

But in September 1958, Faubus closed public schools to prevent their integration. Eisenhower expressed his “regret” over the challenge to the right of all Americans to a public education but took no further action, despite what he had done the year before. There was no violence this time, and Eisenhower believed that he had a constitutional obligation to preserve public order, not to speed school desegregation. When Eisenhower left the White House in January 1961, only 6 percent of African American students attended integrated schools.

Eisenhower and integration

Eisenhower urged advocates of desegregation to go slowly. believing that integration required a change in people's hearts and minds. And he was sympathetic to white southerners who complained about alterations to the social order—their “way of life.” He considered as extremists both those who tried to obstruct decisions of federal courts and those who demanded that they immediately enjoy the rights that the Constitution and the courts provided them.

On only one occasion during his presidency—in June 1958—did Eisenhower meet with African American leaders. The president became irritated when he heard appeals for more aggressive federal action to advance civil rights and failed to heed Martin Luther King Jr.’s advice that he use the bully pulpit of the presidency to build popular support for racial integration. While Eisenhower’s actions mattered, so too did his failure to use his moral authority as president to advance the cause of civil rights.

Eisenhower's record, however, included some significant achievements in civil rights. In 1957, he signed the first civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, providing new federal protections for voting rights. In most southern states, the great majority of African Americans simply could not vote because of literacy tests, poll taxes, and other obstacles. Yet the legislation Eisenhower eventually signed was weaker than the bill that he had sent to Capitol Hill. Southern Democrats secured an amendment that required a jury trial to determine whether a citizen had been denied his or her right to vote—and African Americans could not serve on juries in the south. In 1960, Eisenhower signed a second civil rights law, but it offered only small improvements. The president also used his constitutional powers, where he believed that they were clear and specific, to advance desegregation, for example, in federal facilities in the nation's capital and to complete the desegregation of the armed forces begun during Truman’s presidency. In addition, Eisenhower appointed judges to federal courts whose rulings helped to advance civil rights. This issue, which divided the country in the 1950s, became even more difficult in the 1960s.

The attorney: Thurgood Marshall

NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall argued Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court, and during a quarter-century with the organization, he won a total of 29 cases before the nation's highest court. In 1961, Marshall was appointed to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit by President Kennedy, and in 1965, he became the highest-ranking African American government official in history when President Johnson appointed him solicitor general. Now arguing on behalf of the federal government before the court—Marshall won the majority of those cases as well. In 1967, Johnson nominated Marshall to sit on the court, discussing him with Attorney General Ramsey Clark in a conversation captured on the Miller Center's collection of secret White House tapes:

Featured Video

Eisenhower on integration.

President Eisenhower addresses school integration after the Little Rock Nine.

You are using an outdated browser no longer supported by Oyez. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

1954: brown v. board of education.

On May 17, 1954, in a landmark decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for students of different races to be unconstitutional. The decision dismantled the legal framework for racial segregation in public schools and Jim Crow laws, which limited the rights of African Americans, particularly in the South.

Segregation in Schools

Naacp challenges segregation in court, separate, but equal has 'no place', brown v board quick facts.

What is it? A landmark Supreme Court case.

Significance: Ended 'Separate, but equal,' desegregated public schools.

Date: May 17, 1954

Associated Sites: Brown v Board of Education National Historic Site; US Supreme Court Building

You Might Also Like

- brown v. board of education national historical park

- little rock central high school national historic site

- civil rights

- civil rights movement

- desegregation

- african american history

- brown v. the board of education of topeka

- public education

Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park , Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

Last updated: July 12, 2023

Street Law Inc. Case Summary Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Street Law Case Summary

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Argued: December 9–11, 1952

Reargued : December 7–9, 1953

Decided : May 17, 1954

In 1868, the 14 th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in the wake of the Civil War. It says that states must give people equal protection of the laws and empowered Congress to pass laws to enforce the provisions of the Amendment. Although Congress attempted to outlaw racial segregation in places like hotels and theaters with the Civil Rights Act of 1875, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that law unconstitutional because it regulated private conduct. A few years later, the Supreme Court affirmed the legality of segregation in public facilities in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision . There, the justices said that as long as segregated facilities were of equal quality, segregation did not violate the U.S. Constitution. This concept was known as “separate but equal” and provided the legal foundation for Jim Crow segregation. In Plessy , the Supreme Court said that segregation was a matter of social equality, not legal equality; therefore, the justice system could not interfere. “If one race be inferior to the other socially, the constitution of the United States cannot put them on the same plane.”

By the 1950s, many public facilities had been segregated by race for decades, including many schools across the country. This case is about whether such racial segregation violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14 th Amendment.

In the early 1950s, Linda Brown was a young African American student in Topeka, Kansas. Every day she and her sister, Terry Lynn, had to walk through the Rock Island Railroad Switchyard to get to the bus stop for the ride to the all-Black Monroe School. Linda Brown tried to gain admission to the Sumner School, which was closer to her house, but her application was denied by the Board of Education of Topeka because of her race. The Sumner School was for White children only.

At the time of the Brown case, a Kansas statute permitted, but did not require, cities of more than 15,000 people to maintain separate school facilities for Black and White students. On that basis, the Board of Education of Topeka elected to establish segregated elementary schools.

The Browns felt that the decision of the Board violated the Constitution. They and a group of parents of students denied permission to White-only schools sued the Board of Education of Topeka, alleging that the segregated school system deprived Linda Brown of the equal protection of the laws required under the 14 th Amendment.

The federal district court decided that segregation in public education had a detrimental (harmful) effect upon Black children, but the court denied that there was any violation of Brown’s rights because of the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy. The court said that the schools were substantially equal with respect to buildings, transportation, curricula, and educational qualifications of teachers. The Browns asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review that decision, and it agreed to do so. The Court combined the Brown’s case with similar cases from South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware.

Does segregation of public schools by race violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14 th Amendment?

Constitutional Amendment and Supreme Court Precedents

- 14 th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

“No State shall…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

- Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

A Louisiana law required railroad companies to provide equal but separate facilities for White and Black passengers. A mixed-race customer named Homer Plessy rode in the Whites-only car and was arrested. Plessy argued that the Louisiana law violated the 14 th Amendment by treating Black passengers as inferior to White passengers. The Supreme Court declared that segregation was legal as long as facilities provided to each race were equal. The justices reasoned that the legal separation of the races did not automatically imply that African Americans were inferior, and that legislation and court rulings could not overcome social prejudices. Justice Harlan wrote a strong dissent, arguing that segregation violated the Constitution because it permitted and enforced inequality among people of different races.

- Sweatt v. Painter (1950)

Herman Sweatt was rejected from the University of Texas School of Law because he was African American. He sued school officials alleging a violation of the 14 th Amendment. The Supreme Court examined the educational opportunities at the University of Texas School of Law and the Texas State University for Negroes’ new law school and determined that the facilities, curricula, faculty, and other tangible factors were not equal. Therefore, they ruled that Sweatt’s rights had been violated. In addition to the more straightforward criteria the justices examined at the two schools, they reasoned that other factors, such as the reputation of the faculty and influence of the alumni, could not be equalized.

Arguments for Brown (petitioner)

- The 14 th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause promises equal protection of the laws. That means that states cannot treat people differently based on their race without an extremely good reason. There is not a good reason to keep Black children and White children from attending the same schools.

- Racial segregation in public schools reduces the benefits of education to Black children, solely based on their race. Schools for Black children are often inadequate and have less money and other resources than schools for White children.

- Even if states were ordered by courts to “equalize” their segregated schools, the problems would not go away. State-sponsored segregation creates and reinforces feelings of superiority among White students and inferiority among Black students. Segregation places a badge of inferiority on the Black students, perpetuates a system of separation beyond school, and gives unequal benefits to White students as a result of their informal contacts with one another. It undermines Black students’ motivation to seek educational opportunities and damages identity formation.

- At least two of the high schools in Topeka, Kansas, were already desegregated with no negative effects. The policy should be consistent in all of Topeka’s public primary and secondary schools.

- Segregation is morally wrong.

Arguments for Board of Education of Topeka (respondent)

- The 14 th Amendment states that people should be treated equally; it does not state that people should be treated the same. Treating people equally means giving them what they need. This could include providing an educational environment in which they are most comfortable learning. White students are probably more comfortable learning with other White students; Black students are probably more comfortable learning with other Black students. These students do not have to attend the same schools to be treated equally under the law; they must simply be given an equal environment for learning.

- In Topeka, unlike in Sweatt v. Painter , the schools for Black and White students have similar, equal facilities.

- The United States has a federal system of government that leaves educational decision-making to state and local legislatures. States and local school boards should make decisions about the best environments for school-aged children.

- Housing and schooling have become interdependent. Segregated housing has led to and reinforced segregated schools. Students might need to travel far away from their local school to attend an integrated school. This places a heavy burden on local government to deal with the changes.

The Supreme Court ruled for Linda Brown and the other students; the decision was unanimous. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the opinion of the Court, ruling that segregation in public schools violates the 14 th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

The Court noted that public education was central to American life. Calling it “the very foundation of good citizenship,” they acknowledged that public education was not only necessary to prepare children for their future professions and to enable them to actively participate in the democratic process, but that it was also “a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values” present in their communities. The justices found it very unlikely that a child would be able to succeed in life without a good education. Access to such an education was thus “a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.”

The justices then compared the facilities that the Board of Education of Topeka provided for the education of Black children against those provided for White children. Ruling that they were substantially equal in “tangible factors” that could be measured easily (such as “buildings, curricula, and qualifications and salaries of teachers”), they concluded that the Court must instead examine the more subtle, intangible effect of segregation on the system of public education. The justices then said that separating children solely on the basis of race created a feeling of inferiority in the “hearts and minds” of African American children. Segregating children in public education created and perpetuated the idea that Black children held a lower status in the community than White children, even if their separate educational facilities were substantially equal in “tangible” factors. This deprived Black children of some of the benefits they would receive in an integrated school. The opinion said, “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. This ruling was a clear departure from the reasoning in Plessy v. Ferguson , and, in many ways, it echoed aspects of Justice Harlan’s dissent in that earlier case.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was a single decision signed by all nine Justices. The Court acknowledged the importance and potential controversy of this decision, so they acted uniformly to try to lessen dissent in society. The decision that ordered the desegregation of public schools was praised by many Americans who supported the civil rights movement.

One year after the decision, the Court addressed the implementation of its decision in a case known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka II. Chief Justice Warren once again wrote an opinion for the unanimous Court. The Court acknowledged that desegregating public schools would take place in various ways, depending on the unique problems faced by individual school districts. After charging local school authorities with the responsibility for solving these problems, the Court instructed federal trial courts to oversee the process and determine whether local authorities were desegregating schools in good faith, mandating that desegregation take place with “with all deliberate speed.”

That language proved unfortunate, as it gave the Southern states an incentive to delay compliance with the Court’s mandate.

Many White people fought the implementation of the decision. In Little Rock, Arkansas, the school board agreed to desegregate its schools. But when nine African American students tried to enter Little Rock Central High School, those who still supported segregation, along with the Arkansas National Guard, physically blocked the African American students from entering the school. President Eisenhower quickly deployed the U.S. Army to enforce the integration decision by providing an armed escort to the African American students.

Resistance to integration led to further litigation. In Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (1964), the Court stated that “[t]he time for mere ‘deliberate speed’ has run out, and that phrase can no longer justify denying . . . school children their constitutional rights.”

Today all segregation by law ( de jure segregation) in public education is unconstitutional. However, many schools are still largely made up of students from a single racial or ethnic group because enrollment is assigned based on neighborhoods. This is call de facto segregation because it occurs in practice without a law mandating it.

License and restrictions

This license allows reusers to reproduce, distribute, perform, and display the material for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

The reusers will not modify, adapt or create any derivative works from Street Law Inc. material.

John Jay College Social Justice Landmark Cases eReader Copyright © by John Jay College of Criminal Justice is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Prologue Magazine

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

A landmark case unresolved fifty years later.

Spring 2004, Vol. 36, No. 1

By Jean Van Delinder

"Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments." —Chief Justice Earl Warren, Opinion on Segregated Laws Delivered May 1954

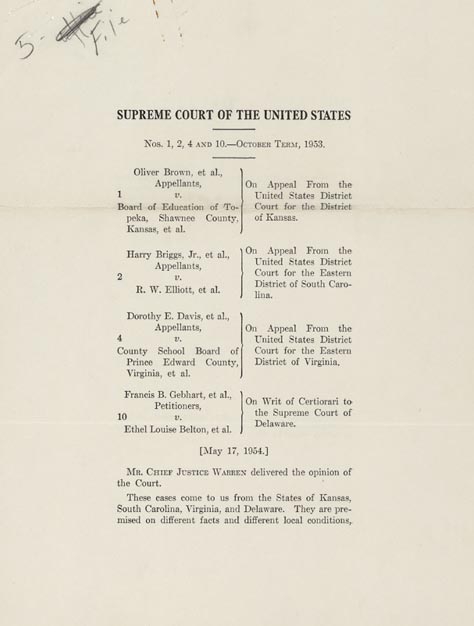

First page of the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. (Records of the Supreme Court of the United States, RG 267)

View in National Archives Catalog

When the United States Supreme Court handed down its unanimous decision in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case fifty years ago this spring, it thrust the issue of school desegregation into the national spotlight.

The ruling that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal" brought racial issues into the forefront of the national consciousness as never before and forced all Americans to confront a racially divided society and undemocratic social practices. At the same time, the decision opened the floodgates of decades of school desegregation suits in both the North and the South.

But the ruling did much more than that. It gave impetus to a young civil rights movement that would write much of American history during the next few decades.

The school segregation issue was ripe for being brought to the first tier of social concerns. Elsewhere in American society, segregation was breaking down.

Important steps were taken in 1941, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802 , forbidding racial discrimination by any defense contractor and establishing a Fair Employment Practices Committee as a regulatory agency to investigate charges of racial discrimination.

In 1947, Major League Baseball saw its first black player in Jackie Robinson . In 1948, President Harry S. Truman ordered the desegregation of the armed forces, which had already seen black and white Americans fighting side by side in World War II. That same year, under the guise of states' rights, racial issues split the Democratic Party.

School segregation came at a high cost even outside of the human costs. For example, school districts had to maintain two school systems within one geographical area. Prior to 1954, Topeka, Kansas, maintained half-empty classrooms in segregated schools in order to keep the races separate. After Brown, this pattern continued with racism disguised as "freedom of choice"—justifying building new schools in outlying areas as merely a response to the population shift to new subdivisions rapidly being built in the western areas of the city (which turned out to be predominantly white and upper class). Left behind were the less affluent, primarily black, residents who had little choice but to send their children to outdated and increasingly inferior schools.

Brown also caused Americans to revisit the role of the national government in regulating local issues. Century-old arguments, reminiscent of the debates over slavery, were revived to defend the primacy of states' rights over federal jurisdiction. The same language used to defend slavery was now being used to defend segregation. Words like "interposition" and "nullification"—which hadn't been heard for more than a century—were used to defend school segregation. 1

Just as the Civil War caused Americans to confront the ugly reality of slavery, so too did Brown inspire Americans to confront its undemocratic system of education.

In recognizing the importance of education as the foundation of a democratic society, the Brown decision expressed the sentiments of Thomas Jefferson that publicly funded education was to be the primary mechanism to develop a natural elite and to ensure that the new republic had a literate citizenry regardless of social class. Jefferson's beliefs were reflected in the words of Chief Justice Earl Warren, who justified the significance of education in the Brown decision as being "the very foundation of good citizenship." 2

The Topeka Brown case is important because it helped convince the Court that even when physical facilities and other "tangible" factors were equal, segregation still deprived minority children of equal educational opportunities.

Over the years, numerous scholars have traced the history of the Brown case and analyzed its impact as federal legislation. Yet most of these studies have been written from a national perspective, distant from the day-to-day life of the local people most affected by school desegregation.

The Topeka Brown records provide a glimpse of what people were doing in their local communities, where the struggle for racial justice was a continuing reality, year in and year out. The records help us to understand the reality of school segregation in places like Topeka, where it was only legal in the elementary schools. What was the effect of "separate-but-equal"?

Overview of the National Case before the Supreme Court

In October 1952, the Supreme Court announced it would hear five pending school desegregation cases collectively. In chronological order, the five consolidated cases were 1949: Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al. (South Carolina); 1950: Bolling v. Sharpe (District of Columbia); 3 May 1951: Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al. (Virginia); June 1951: Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (Kansas); October 1951: Gebhart et al. v. Belton et al. (Delaware).

These cases all document inadequate funding for segregated schools—meaning that many black children lacked playgrounds, ball fields, cafeterias, libraries, auditoriums, and other amenities provided for white children in newer schools. In Summerton, South Carolina, and Hockessin, Delaware, school buses were only provided for whites, while black children had to walk. In Claymont, Delaware, and Farmville, Virginia, there was no senior high school for black pupils.

The Brown case of Topeka, Kansas, itself included twelve other plaintiffs besides Oliver Brown, whose daughter Linda was being bused twenty-one blocks from her home to a segregated school. The nearest school in her neighborhood was only a few blocks away, but it was for whites only.

All of these cases were appealed to the Supreme Court, and the first round of arguments were held December 9–11, 1952. The following June, the Supreme Court ordered that a second round of arguments be heard in October 1953. When Chief Justice Fred Vinson, Jr., died unexpectedly of a heart attack in September, President Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated California Governor Earl Warren to replace Vinson. The Court rescheduled Brown v. Board arguments for December. On May 17, 1954, the Court declared that racial segregation in public schools violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, effectively overturning the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision mandating "separate but equal."

The Brown ruling directly affected legally segregated schools in twenty-one states. In 1954, seventeen states had laws requiring segregated schools (Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware), and four other states had laws permitting rather than requiring segregated schools (Kansas, Arizona, New Mexico, and Wyoming). Kansas's state statutes restricted segregated elementary schools only to cities, such as Topeka, that had populations of more than fifteen thousand.

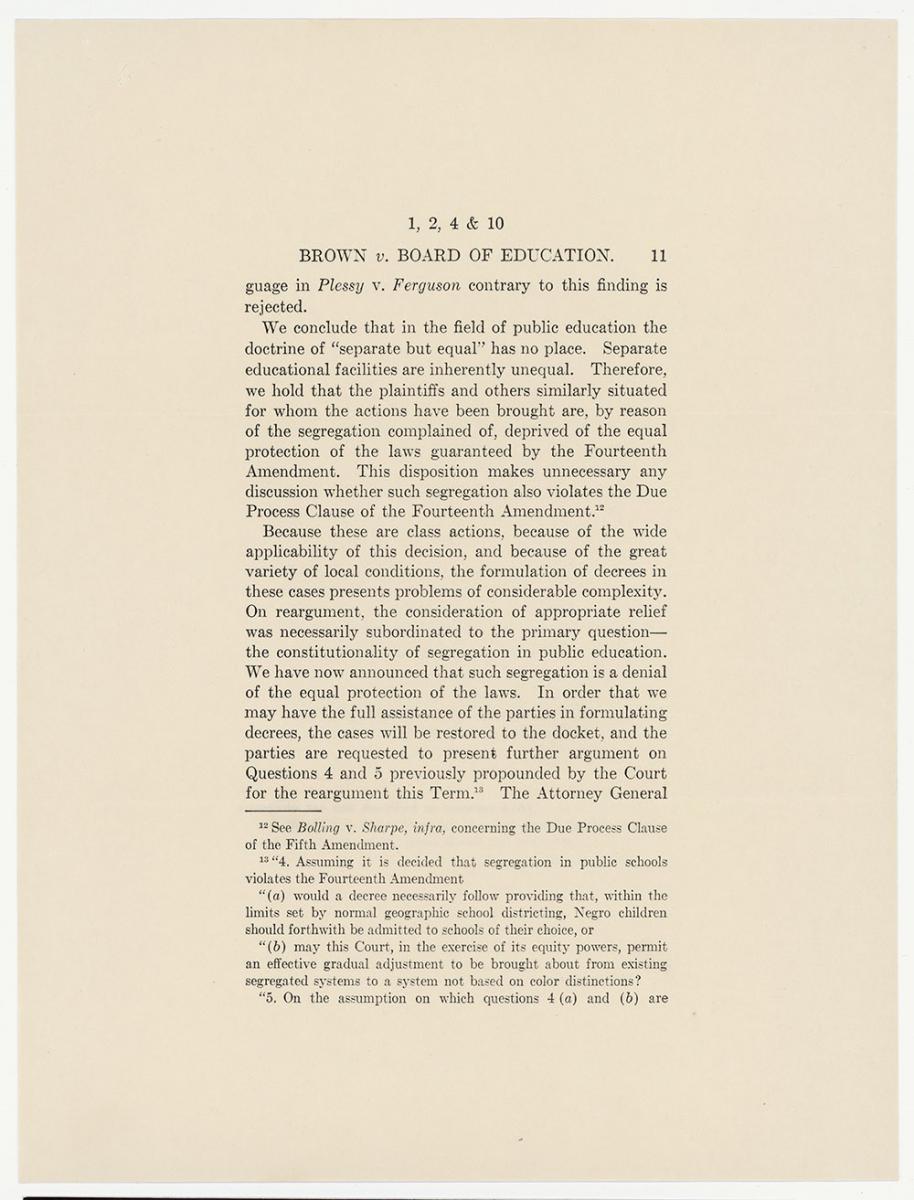

Page 11 of the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which states that the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place in public education. (Records of the Supreme Court of the United States, RG 267)

Though the 1954 ruling declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, it did not specify how this was to be remedied. Originally the Court scheduled arguments on this subject for later in the year, but it did not hear what would become the third round of arguments in Brown until April 1955. 4 On the last day of its term, the Supreme Court ordered desegregation to begin with "all deliberate speed."

In the intervening year, the District of Columbia and some school districts in other states had voluntarily begun to desegregate their schools. However, state-sanctioned opposition to desegregation was already well under way in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia, where the Court's decision had been declared "null, void, and no effect." Across the South, schools were closed and public education was suspended. Public funds were disbursed to parents to subsidize the education of their children in private schools. Some states even went so far as to impose sanctions on anyone who implemented desegregation.

Effects of the Supreme Court Decision in Kansas

In Topeka, resistance to desegregation was more indirect, subtle, and covert. Historically, the color line in Kansas was more permeable than it was South Carolina or Virginia. Its "border state" ideology was directed more toward racial collegiality and inclusion than animosity and exclusion. Kansas had relatively permissive segregation statutes (compared to some southern states).

For example, segregation was permitted in elementary schools where the population exceeded fifteen thousand (cities of the first class). The one segregated high school—Sumner High School in Kansas City, Kansas—had been established in 1905 after a special act of the legislature allowed segregation of a secondary school in this one instance. However, Kansas's permissive racial statutes served to disguise the underlying reality of an unwritten code of racial separation that rivaled locales where total de jure public segregation was practiced. Topeka's continued segregation of its public school system after Brown illustrates how the dismantling of a de jure system of segregation does not necessarily include the end of racist social practices.

Over the several decades following Brown, covert opposition to desegregation was carried out under cover of school redistricting and convoluted attendance boundaries. It was also aided by real estate developers riding the postwar housing boom, who urged white Topekans to buy new houses and move to the newer—and racially homogenous—western suburbs. The City of Topeka obliged this migration by annexing western territory several times between 1950 and 1979. There was a corresponding rise in demand for more schools from the Topeka Board of Education and its successor, Unified School District #501. Between 1957 and 1966, Topeka witnessed the creation of an "alternative predominantly white, school sub-system generally around the peripheral boundary but specifically concentrated in the southern and western portions of the Topeka school system." New schools built after 1959 would have pupil racial ratios that would be all or disproportionately white. Additionally, classroom additions and portable classrooms would be primarily placed at disproportionately white schools.

Though the official end of segregation in 1954 met with far less hostility in Kansas than in Mississippi or South Carolina, African Americans still encountered obstacles. News correspondent Carl T. Rowan had found Topeka to be a "pretty segregated city" when he lived there as a navy trainee during World War II. Returning to Kansas in 1953, he described his earlier experiences by observing, "Topeka was a paradox. There was no Jim Crow in some areas where you had expected it; segregation had deep roots where it was not expected."

The state's permissive segregation laws meant that overt segregation was strictly limited, while covert segregationist practices arose unrestrained. "There was no segregation on city buses, or in any public transportation," Rowan recalled. "But I was unable to go to a movie or into a restaurant with white navy buddies. Hotels, bowling alleys and other public recreation facilities were closed to Negroes."

A decade later and just a few months before the first Brown decision, Rowan still found it difficult to find a restaurant willing to serve him and his companion, attorney Charles Scott, the original lawyer involved in the Brown case. Despite the legal demise of segregation, informal segregation was still intact. Rowan and Scott were asked by one restaurant owner to eat in the kitchen not because of any law requiring racial separation, but simply because it was his "policy." As an attorney, Scott understood that it was much easier to remove segregation laws than to confront and change the informal racial practices that permeated the embarrassing day-to-day reality of racial segregation. "And it stems from Jim Crow schools," Scott declared to Rowan as they left one restaurant without being served, "because when segregation is part of the pattern of learning it permeates every area of life."

Early Challenges to School Segregation in Topeka: 1900–1950

In Kansas, the antecedents of the Brown case can be traced back through eleven previous lawsuits challenging segregation. Beginning in 1880, these suits all challenged the legality of school segregation as it was practiced in Kansas. 5 Of the three cases that involved Topeka's schools, two are especially relevant to the Brown case. The earliest case, dating from 1901, involved the introduction of segregation in recently annexed areas (the Reynolds case), and the other case (the Graham case in 1940) involved the decision of whether or not junior high schools fell under the state's segregation statutes.

Similar patterns of racial upheaval and containment, begun with the annexation issues related to the Reynolds case and the limitation of segregation to elementary schools as illustrated by the Graham case, continued throughout the Brown litigation.

The issues involved in both of these cases were the effect of segregation itself on public education, the system of social practices that had arisen around it, and whether segregation as it existed was a violation of the due process clause in the Fourteenth Amendment, the same issues involved in the Brown decision.

"In approaching this problem," Chief Justice Warren wrote in 1954, "we cannot turn the clock back to 1868 when the [Fourteenth] Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws."

In Kansas, both the Reynolds and Graham cases illustrate the development of the issues that came to fruition nationally in the Brown case.

The Reynolds Case

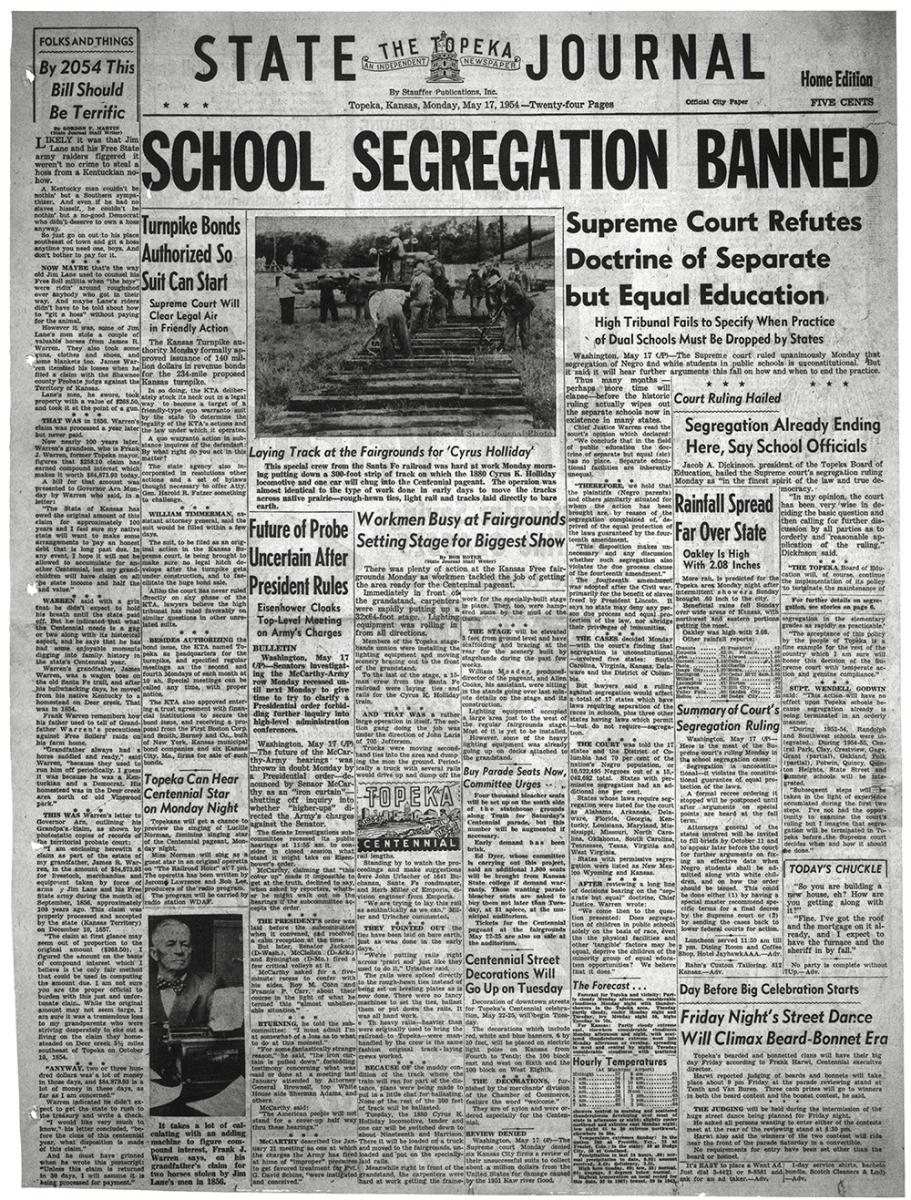

The Topeka State Journal reported the historic May 17, 1954, decision that segregation in public schools must end. (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21, NARA–Central Plains Region [Kansas City])

On February 1, 1901, William Reynolds tried to enroll his eight-year-old son Raul in the new school that was reserved for whites. When he was refused, Reynolds filed suit on behalf of his son. In the complaint, the court record stated that

Because of race and color, and for no other reason whatever, his child has been and is excluded from attending school in said new building by the express order and direction of said board . . . thus putting publicly upon the plaintiff and his child the badge of a servile race, and holds them up to public gaze as unfit to associate, even in a public institution of the state, with other races and nationalities, in violation of the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments to the constitution of the United States, and, in violation of said fourteenth amendment, denies to the plaintiff and his child the equal protection of the laws.

The context behind the Reynolds suit was related to the geographical circumstances of Topeka. The westward growth of Topeka was caused in part by its being geographically constrained by the Kansas River to its north and southeast. Due to the contours of its flood plain, the least desirable land was north and east of the city, an area that came to be predominately African American. The more desirable land—which rarely flooded—was toward the west and south, and was predominately white. This pattern of settlement would continue throughout the twentieth century.

In the 1890s, the city of Topeka annexed part of a rural district, No. 91, south and west of the town's center, locally known as the "Lowman Hill District." Being a rural district, No. 91 did not have segregated schools. After annexation it continued to be integrated because "it did not become convenient or expedient to make provision for separate schools . . . until the said school building was destroyed by fire." After a fire occurred on July 20, 1900, the district implemented segregation by ordering that the fifty African American children living in the area be forced to attend classes in an old building that had been moved to the original site of the burnt-out school and outfitted with second-hand furniture. The district then built a new school for the 130 white children living in the area, which brought about the Reynolds suit.

Reynolds ultimately lost his case, and his son had to attend a segregated school. The school board argued that the new school building was larger and more centrally located in order to accommodate the white children, who outnumbered the African American children living in the area.

We see that as early as 1901, the parents of white children were able to enjoy the benefits of sending their children to newer, neighborhood schools while the parents of African American children had to send their children to segregated schools, many of which were not located close to where they lived.

The Graham Case

Just as land annexation resulted in a challenge to segregation, so too did the shift toward junior high curriculum bring another challenge to Topeka's segregated schools with the Graham case. When the segregation statutes were first written in 1861 and later modified in 1879, junior high schools did not exist, and very few people of any race went on to high school. The subsequent redefinition of state segregation statutes after 1940 was in response to an innovation in the institutional structure of public education accompanied by rapidly increasing enrollments in secondary and post-secondary institutions.

When Topeka adopted the junior high system, it implemented a different educational curriculum for seventh and eighth grade students based on race. White students were provided with a 6-3-3 system, consisting of six years of elementary or grade school, three years of junior high school, and three years of senior high school. Black children were under an 8-1-3 plan.

The 8-1-3 plan meant that African American children in Topeka remained in segregated schools through the eighth grade, choosing either to enter an integrated ninth grade at Boswell Junior High or remain in a segregated class by electing to attend Roosevelt Junior High. White children who left elementary school after sixth grade and attended junior high school were consequently introduced to a much more specialized curriculum.

A 1953 letter from the superintendent of schools advises a black teacher that she won't be retained if segregation is ruled unconstitutional. (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21, NARA–Central Plains Region [Kansas City])

The court transcript of the Graham case illustrates the differences between the segregated elementary schools and the junior high schools. When the plaintiff, who had just finished sixth grade, tried to enroll in Boswell Junior High School, he was refused admittance on the basis of his race. He filed suit, claiming the course of instruction offered at Buchanan Elementary was not equal to that available at Boswell Junior High.Boswell was a new facility and built for the express purpose of being a junior high. It contained many more classrooms than the elementary schools, allowing for students to change classes for specialized teaching. In the segregated schools, one instructor taught most of the subjects.

At segregated Buchanan School, one teacher taught most of the math and English courses, while at Boswell Junior High School different instructors taught all these subjects. In the testimony provided by witnesses in the Graham case, the home economics teacher at Buchanan, Miss Ruth Ridley, reported that though her students were well prepared when they graduated from the eighth grade, they did not have facilities comparable to the better equipped and more up-to-date sewing and cooking rooms at Boswell.

Graham won his case: The junior highs in Topeka were legally desegregated. However, the effect was uncertain—desegregation did not include the teaching and administrative staff. For example, after the Graham case, eight African American teachers lost their jobs due to the integration of the junior highs. The assumption that the curriculum was not equal to the white schools reflected poorly on the high dedication and exemplary training of the black teachers, which many of them rightly resented. At two of the four segregated schools in Topeka, more of the teachers held master's degrees than at any of the white grade schools.

Though no formal policy existed to not hire black teachers, it soon became obvious in Topeka that the number of African American teachers slowly dwindled after April 1953. Before the Brown decision, Topeka had 27 African American teachers who taught 779 students. By 1956, the number of African American pupils had increased to 898, but the number of full-time teachers had declined to 21. After the desegregation of the elementary schools in 1954, for most black teachers in Topeka and elsewhere, Brown did not result in integration; it still meant segregation or even worse, unemployment. This decline in employment of black teachers after integration is a largely unacknowledged fact of desegregation.

Contemporary Challenges to School Segregation in Topeka: 1950–1985

By 1950, the Topeka school system had twenty-two elementary schools (9.6 percent black), six junior high schools (9.9 percent black), and one senior high school (7.6 percent black). As permitted by state law, racial segregation of students at the elementary level was strictly adhered to. The four schools that were maintained for black students were Buchanan, McKinley, Monroe, and Washington. Each of these four schools was geographically located in predominately black areas, although students were brought in from throughout the system. Five of the eighteen white elementary schools were located in predominately white areas, while the remaining thirteen schools, though reserved exclusively for whites, were located in racially mixed neighborhoods.

Segregation was maintained at a considerable cost as the four segregated elementary schools had much smaller student enrollments than their white counterparts. In 1950, all four of the segregated schools had an average of 143 pupil spaces underutilized, while the all-white schools were much more crowded, averaging only 28 spaces underutilized. The average black school had an enrollment of 165 students, while the white schools had an average enrollment of 342. Topeka did not use the available classroom space in the black schools to relieve overcrowding in the white schools. Given that thirteen of the eighteen schools reserved for whites were in racially mixed neighborhoods, it would have been relatively simple to reassign pupils without the additional expense of providing transportation.

Racial segregation was sustained over the next thirty years as the Topeka School Board constantly changed boundary lines ensuring that some its elementary schools remained segregated, and its high schools became more segregated than they were before 1954. In 1955, three former all-black elementary schools were still 100 percent black with only 1 percent of its black children attending elementary schools that were formerly for whites.

From 1931 to 1958, Topeka had one, integrated, senior high school: Topeka Senior High School. Five years after the original Brown decision, when faced with the opportunity to continue the racial parity at the senior high school level that had already existed for more tan twenty years, the Topeka Board of Education made a series of decisions that ensured that racial segregation would be compounded by class. As city boundaries expanded to the south and west, two more high schools were added: Highland Park Senior High School, acquired through annexation in 1959, and Topeka West Senior High School, opened in 1961. The aging Topeka Senior High now had 83.2 percent of the black students in the Topeka school system assigned to it while was approximately 11 percent black, and Highland Park was 5.1 percent black. One year later, were now being Topeka High, while Highland Park had 6.5 percent and Topeka West had 0.3 percent.

The 1960 U.S. Census data indicates that the largest concentration of Topeka's black population with school-age children resided midway between Topeka High and Highland Park. A simple change in the attendance boundary when Highland Park was annexed would have brought its minority enrollment to 50 percent. It would have also alleviated overcrowding at Topeka High, since Highland Park had 497 empty seats. Instead, the Topeka School Board elected to build a third high school (Topeka West) at the western fringe of the growing city, assigning to it 2 black children and 702 white children.

Twenty years after Brown, in 1974, the Topeka school system (U.S.D #501) still underutilized predominately black schools while white schools remained overcrowded. For example, there was a 15.1 percent black enrollment at the elementary level, but more than half of them (56.7 percent) were assigned to seven schools, while the nine of the remaining eleven had an average of 4.5 black children assigned to each of them.

Two of those schools, McClure and Potwin, were all-white in 1974. On September 10, 1973, Johnson v. Whittier was filed as a class action brought on behalf of "all Black children who were then or had during the past ten years been students of elementary and junior high schools in East Topeka and North Topeka." The complaint concentrated more on "equality of facilities than distribution of students, alleging that the children in West Topeka and South Topeka received vastly superior educational facilities and opportunities, including buildings, equipment, libraries and faculties, than could be obtained by students in the areas of East Topeka and North Topeka, which contained higher percentages of minority students."