Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Strengths and Limitations of Case Study Research

Related Papers

Ilse Schrittesser

International studies provide evidence that effective teachers are essential to students' learning success. Research on teacher effectiveness in the United States began in the 1980's, and valid and reliable methods for assessing teacher effectiveness have been developed in its context, research on this topic is still relatively new in German-speaking countries. While effective teaching is a highly complex construct which includes a whole repertoire of skills, there seems evidence that some of these skills play a particularly significant role for effective teaching. The present article will take a close look at these skills from the perspective of two mostly separate discourses: expertise research and the qualities of expert teachers, which are usually discussed in the Anglo-American context, and theories of teacher professionalism which is highly influential in the German speaking countries. The two concepts are explained and it is argued that-interestingly enough-research r...

Anju Chhetri

This article presents the case study as a type of qualitative research. Its aim is to give a detailed description of a case study-its definition, some classifications, and several advantages and disadvantages-in order to provide a better understanding of this widely used type of qualitative approac h. In comparison to other types of qualitative research, case studies have been little understood both from a methodological point of view, where disagreements exist about whether case studies should be considered a research method or a research type, and from a content point of view, where there are ambiguities regarding what should be considered a case or research subject. A great emphasis is placed on the disadvantages of case studies, where we try to refute some of the criticisms concerning case studies, particularly in comparison to quantitative research approaches.

Cambridge Journal of Education

ethiopia-ed.net

Kathleen Armour

Bedrettin Yazan

Case study methodology has long been a contested terrain in social sciences research which is characterized by varying, sometimes opposing, approaches espoused by many research methodologists. Despite being one of the most frequently used qualitative research methodologies in educational research, the methodologists do not have a full consensus on the design and implementation of case study, which hampers its full evolution. Focusing on the landmark works of three prominent methodologists, namely Robert Yin, Sharan Merriam, Robert Stake, I attempt to scrutinize the areas where their perspectives diverge, converge and complement one another in varying dimensions of case study research. I aim to help the emerging researchers in the field of education familiarize themselves with the diverse views regarding case study that lead to a vast array of techniques and strategies, out of which they can come up with a combined perspective which best serves their research purpose.

Nina Oktavia

Case study is believed as the widely used kind of research to view phenomena, despite of some critics on it concerning mostly on its data reliability, validity and subjectivity. This article therefore discusses some aspects of case study which are considered important to be recognized by novice researchers, especially about the way how to design and how to make sure the quality and reliability of the case. In addition, the case studying educational research also becomes the focus to be discussed, completed with some examples, to be able to open our mind to the plenty opportunities for case study in education.

Professional Development in Education

Lars Petter Storm Torjussen

Higher Education Pedagogies

Frances O'Brien

RELATED PAPERS

Brian Duvick

Ágora: Estudos em Teoria Psicanalítica

Laure Westphal

Biomedical Microdevices

Ringga Hardika

Geophysical Research Letters

Hans Schouten

ANKEM DERGİSİ

singapuram venkatesh

Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society

Dan Burghelea

International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health

María Dolores Segarra Muñoz

Duke Mathematical Journal

Raphaël KRIKORIAN

Josef Fulka

Educacao Revista Do Centro De Educacao

Ana Elisa Ribeiro

European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care

André Alexandre

roman caspar

Sodiq Abdul azeez

Accounting Horizons

Jerry Strawser

U.S. Government Printing Office

A. Egon Cholakian

Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society

mounir Haddou

Sofoklis Sotiriou

Journal of the Chilean Chemical Society

Ruben Muñoz

International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Medicine (IJPSM)

IJPSM Journal

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- About This Site

- What is social theory?

- Habermas/Parsons

- Frankfurt School

- Inequalities

- Research Students

- Dirty Looks

- Latest Posts

- Pedagogy & Curriculum

- Contributors

- Publications

Select Page

What are the benefits and drawbacks of case study research?

Posted by Mark Murphy | May 24, 2014 | Method , Research Students | 0

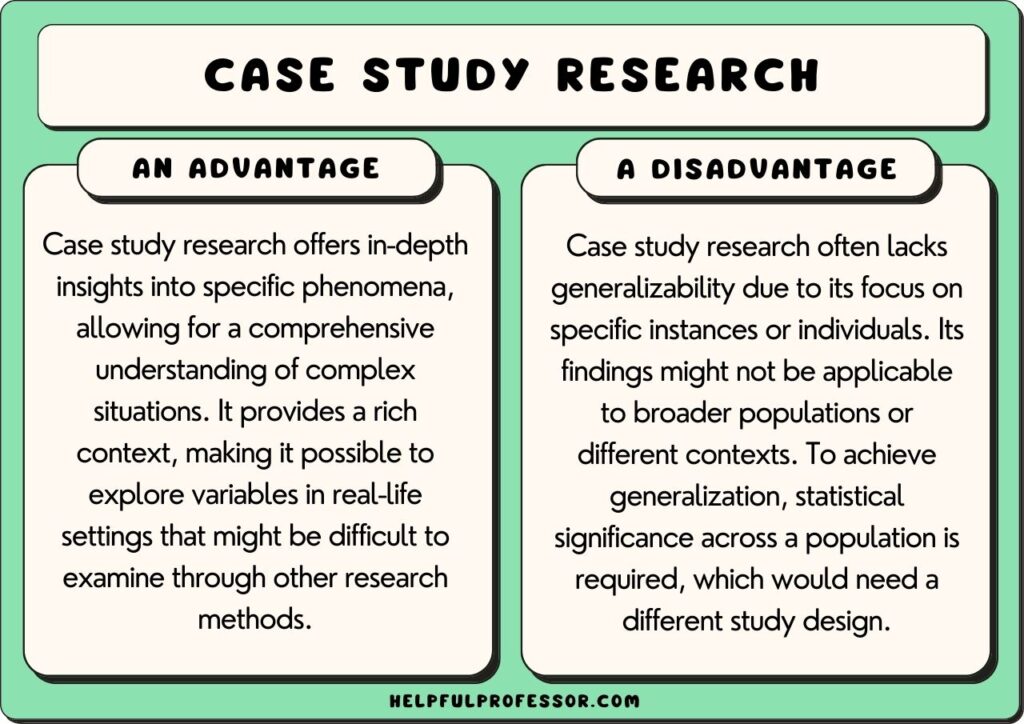

There should be no doubt that with case studies what you gain in depth you lose in breadth – this is the unavoidable compromise that needs to be understood from the beginning of the research process. So this is neither an advantage nor a disadvantage as one aspect cancels out the benefits/drawbacks of the other – there are other benefits and drawbacks that need attention however …

- Their flexibility: case studies are popular for a number of reasons, one being that they can be conducted at various points in the research process. Researchers are known to favour them as a way to develop ideas for more extensive research in the future – pilot studies often take the form of case studies. They are also effective conduits for a broad range of research methods; in that sense they are non-prejudicial against any particular type of research – focus groups are just as welcome in case study research as are questionnaires or participant observation.

- Capturing reality: One of their key benefits is their ability to capture what Hodkinson and Hodkinson call ‘lived reality’ (2001: 3). As they put it, case studies have the potential, when applied successfully, to ‘retain more of the “noise” of real life than many other types of research’ (Hodkinson and Hodkinson, 2001: 3). The importance of ‘noise’ and its place in research is especially important in contexts such as education, for example in schools where background noise is unavoidable. Educational contexts are always complex, and as a result it is difficult to exclude other unwanted variables, ‘some of which may only have real significance for one of their students’ (Hodkinson and Hodkinson, 2001, 4).

- The challenge of generality: At the same time, given their specificity, care needs to be taken when attempting to generalise from the findings. While there’s no inherent flaw in case study design that precludes its broader application, it is preferable that researchers choose their case study sites carefully, while also basing their analysis within existing research findings that have been generated via other research designs. No design is infallible but so often has the claim against case studies been made, that some of the criticism (unwarranted and unfair in many cases) has stuck.

- Suspicion of amateurism: Less partisan researchers might wonder whether the case study offers the time and finance-strapped researcher a convenient and pragmatic source of data, providing findings and recommendations that, given the nature of case studies, can neither be confirmed nor denied, in terms of utility or veracity. Who is to say that case studies offer anything more than a story to tell, and nothing more than that?

- But alongside this suspicion is another more insiduous one – a notion that ‘stories’ are not what social science research is about. This can be a concern for those who favour case study research, as the political consequences can be hard to ignore. That said, so much research is based either on peoples’ lives or the impact of other issues (poverty, institutional policy) on their lives, so the stories of what actually occurs in their lives or in professional environments tend to be an invaluable source of evidence. The fact is that stories (individual, collective, institutional) have a vital role to play in the world of research. And to play the specific v. general card against case study design suggests a tendency towards forms of research fundamentalism as opposed to any kind of rational and objective take on case study’s strengths and limitations.

- Preciousness: Having said that, researchers should not fall into the trap (surprising how often this happens) of assuming that case study data speaks for itself – rarely is this ever the case, an assumption that is as patronising to research subjects as it is false. The role of the researcher is both to describe social phenomena and also to explain – i.e., interpret. Without interpretation the research findings lack meaningful presentation – they present themselves as fact when of course the reality of ‘facts’ is one of the reasons why such research is carried out.

- Conflation of political/research objectives: Another trap that case study researchers sometimes fall into is presenting research findings as if they were self-evidently true, as if the stories were beyond criticism. This is often accompanied by a vague attachment to the notion that research is a political process – one that is performed as a form of liberation against for example policies that seek to ignore the stories of those who ‘suffer’ at the hands of overbearing political or economic imperatives. Case study design should not be viewed as a mechanism for providing a ‘local’ bulwark against the ‘global’ – bur rather as a mechanism for checking the veracity of universalist claims (at least one of its objectives). The valorisation of particularism can only get you so far in social research.

Reference: Hodkinson, P. and H. Hodkinson (2001). The strengths and limitations of case study research. Paper presented to the Learning and Skills Development Agency conference, Making an impact on policy and practice , Cambridge, 5-7 December 2001, downloaded from h ttp://education.exeter.ac.uk/tlc/docs/publications/LE_PH_PUB_05.12.01.rtf.26.01.2013

About The Author

Mark Murphy

Mark Murphy is a Reader in Education and Public Policy at the University of Glasgow. He previously worked as an academic at King’s College, London, University of Chester, University of Stirling, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, University College Dublin and Northern Illinois University. Mark is an active researcher in the fields of education and public policy. His research interests include educational sociology, critical theory, accountability in higher education, and public sector reform.

Related Posts

Reading theory: My nervous encounters with Actor Network Theory

January 20, 2014

The experiences of ‘estranged students’: Call for Participants

April 27, 2018

Academic Cherrypicking; and ‘Lensification’

April 1, 2013

I am moving to Norway

August 14, 2013

Recent Posts

The strengths and limitations of case study research

Hodkinson, P

展开

In the current educational climate, there is considerable pressure from a variety of sources to develop and emphasize scientific approaches to researching educational practice. Thus, Reynolds (1998) called for a science of teaching, and the evidence-based practice movement appears to regard the ideal form of research as the experiment, or randomized controlled trial (Oakley, 2000). The search is on to discover significant truths about teaching and learning that are 'safe' to share with practitioners, and generalisable across all relevant settings. This dominant approach raises older doubts about the value of qualitative case study research. It is argued that such studies cannot be generalised from, and are unlikely to produce findings that have predictive value. Yet a significant proportion of the better recent research in the learning and skills sector has taken the form of small scale investigations. In addition to our own work, of which more below, there are, for example, studies of sample FE colleges (Ainley and Bailey, 1997; Gleeson and Shain, 1999; Shain and Gleeson, 1999) of workplace learning (Lave and Wenger, 1991; Engestrom, 2001) youth training (Lee et al., 1990) and transitions from school to further education, training, employment unemployment etc (Ball et al, 2000). Furthermore, for many researchers based within the learning and skills sector, small scale case study work is one of few types of research that is viable, with the limited resources available. So in this apparently paradoxical context, what is the place and value of case study research? In particular, why have we chosen to conduct two different case study investigations into learning and teaching, within the Economic and Social Research Council's (ESRC) Teaching and Learning Research Programme (TLRP)? One of these studies, conducted by both of us, focuses on the significance of school and departmental cultures in school teachers' learning. The other, where Phil Hodkinson is working with others focuses on Transforming Learning Cultures in Further Education. We will say a little more about each of these, later. This paper is not concerned either with how to conduct case studies effectively (see Stake, 1995, Yin 1994), or with presenting a details analysis of the literature that addresses this complex question (See Gomm, et al., 2000). Rather, we draw upon our own past and current research investigations to examine the strengths of case study research, and then the limitations. We then address directly the problematic question about the extent to which more generalized lessons can be learned from idiosyncratic case study research. We conclude by arguing that case studies are a valuable means of researching the learning and skills sector but that, as with all research, interpreting case study reports requires care and understanding. ; 31 ; 113 ; 1887 ; 1925 ; 1861 ; 1686 ; 97 ; 22 ; 1931 ; 1709 ; 41 ; 1726 ; 120 ; 1764

Computer Assisted Instruction Effectiveness Self-Learning Material and Auto Instruction

10.1097/CIN.0000000000000035

通过 文献互助 平台发起求助,成功后即可免费获取论文全文。

我们已与文献出版商建立了直接购买合作。

你可以通过身份认证进行实名认证,认证成功后本次下载的费用将由您所在的图书馆支付

您可以直接购买此文献,1~5分钟即可下载全文,部分资源由于网络原因可能需要更长时间,请您耐心等待哦~

百度学术集成海量学术资源,融合人工智能、深度学习、大数据分析等技术,为科研工作者提供全面快捷的学术服务。在这里我们保持学习的态度,不忘初心,砥砺前行。 了解更多>>

©2024 Baidu 百度学术声明 使用百度前必读

Using the Learning in Future Environments (LiFE) Index to Assess James Cook University’s Progress in Supporting and Embedding Sustainability

- First Online: 04 June 2019

Cite this chapter

- Colin J. Macgregor 4 ,

- Adam Connell 5 ,

- Kerryn O’Conor 5 &

- Marenn Sagar 5

Part of the book series: World Sustainability Series ((WSUSE))

1158 Accesses

1 Citations

Increasingly, higher education institutions (HEIs) are seeking to assess and report on their sustainability performance. One of the more widely known assessment tools is STARS (Sustainability Tracking, Assessment and Rating System). Developed in 2007, STARS has been criticised because of its pressuring characteristic i.e. it has been designed to support external performance reporting. The LiFE (Learning in Future Environments) index is a non-committal assessment tool that allows HEIs to monitor their progress in supporting and embedding sustainability without the need to reveal their performance externally. LiFE has been adopted by members of the Environmental Association of Universities and Colleges (EAUC) and Australasian Campuses Towards Sustainability (ACTS). This paper presents findings from a study of James Cook University’s experiences with LiFE since 2013. Scores suggest JCU has had an inconsistent response to sustainability over the last five years. The paper describes and discusses some of the factors that have influenced JCU’s scores and highlights some of the factors that emerged to support or interfere with the University’s sustainability aspirations. The paper will be of interest to any HEI using or considering using the LiFE index or anyone who is interested or involved with embedding sustainability in HEIs.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Assessing Sustainability: Measuring Individual and Institutional Progress

An Indicator-Based Approach to Sustainability Monitoring and Mainstreaming at Universiti Sains Malaysia

Pioneering in Sustainability Reporting in Higher Education: Experiences of a Belgian Business Faculty

AASHE (2017) STARS technical manual version 2.1, July 2017. Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. http://www.aashe.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/STARS-2.1-Technical-Manual-Administrative-Update-Three.pdf . Accessed 28 Aug 2018

AASHE (2018) Why participate in STARS?. Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. https://stars.aashe.org/pages/about/why-participate.html . Accessed 24 Sept 2018

ACTS (2014) Learning in future environments: about LiFE. Australian Campuses Towards Sustainability. https://life.acts.asn.au/about-LiFE/ . Accessed 30 Aug 2018

ACTS (2017) Learning in future environments. Australian Campuses Towards Sustainability. https://www.acts.asn.au/learning-in-future-environments-life/ . Accessed 30 Aug 2018

Berks F (2009) Evolution of co-management: role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J Environ Manag 90(5):1692–1702

Article Google Scholar

Berzosa A, Bernaldo MO, Fernandez-Sanchez G (2017) Sustainability assessment tools for higher education: an empirical comparative analysis. J Clean Prod 161:812–820

Boyle C (2004) Considerations on educating engineers in sustainability. Int J Sustain High Educ 5(2):147–155

Cavagnaro E, Curiel G (2012) The three levels of sustainability. Greenleaf Publishing Ltd, Sheffield, UK, 186 pp

Google Scholar

Cole L (2003) Assessing sustainability on Canadian university campuses: development of a campus sustainability assessment framework. MA thesis, Environment and Management, Royal Roads University, Canada

Ceulemans K, Molderez I, Van Liedekerke L (2015) Sustainability reporting in higher education: a comprehensive review of the recent literature and paths for further research. J Clean Prod 106:127–143

EAUC (2018) The platform for sustainability performance in education: AISHE. Environmental Association for Universities and Colleges. http://www.eauc.org.uk/theplatform/aishe . Accessed 28 Aug 2018

Fonseca A, Macdonald A, Dandy E, Valenti P (2011) The state of sustainability reporting at Canadian universities. Int J High Educ 12(1):22–40

Galbraith K. (2009) Environmental studies enrollment soars. The New York Times, 24 Feb 2009. https://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/02/24/environmental-studies-enrollments-soar/ . Accessed 28 Aug 2018

Gridsted T (2011) Sustainable universities—from declarations on sustainability in higher education to national law. Environ Econ 2(2):29–36

Hewlett SA, Sherbin L, Sumberg K (2009) How generation Y and boomers will reshape your agenda. Harv Bus Rev 87(7/8):76–84

Hodkinson P, Hodkinson H (2001) The strengths and limitations of case study research. Paper presented to the learning and skills development agency conference making an impact on policy and practice, Cambridge, 5–7 Dec 2001

Hoover E, Harder MK (2015) What lies beneath the surface? The hidden complexities of organizational change for sustainability in higher education. J Clean Prod 106:175–188

Huber S, Bassen A (2018) Towards a sustainability reporting guideline in higher education. Int J Sustain High Educ 19(2):218–232

JCU (2018a) The state of the tropics project. James Cook University. https://www.jcu.edu.au/tropeco-sustainability-in-action/sustainability-champions . Accessed 18 Sept 2018

JCU (2018b) Sustainable office accreditation. James Cook University. https://www.jcu.edu.au/state-of-the-tropics/project . Accessed 12 Sept 2018

Leal Filho W (2000) Dealing with misconceptions on the concept of sustainability. J Sustain High Educ 1(1):9–19

Legget J (2009) Measuring what we treasure or treasuring what we measure? Investigating where community stakeholders locate the value in their museums. Mus Manag Curatorsh 24(3):213–232

Lopatta K, Jaeschke R (2014) Sustainability reporting at German and Austrian universities. Int J Educ Econ Dev 5(1):66–90

Lozano R (2006) A tool for the graphical assessment of sustainability at universities. J Clean Prod 14(9/11):963–972

Lukman R, Glavic P (2007) What are the key elements of a sustainable university? Clean Technol Environ Policy 9(2):103–114

Macgregor CJ (2015) James Cook University’s holistic response to the sustainable development challenge. In: Leal Filho W (ed) Transformative approaches to sustainable development at universities. World sustainability series. Springer, Switzerland, 25 pp

SDSN (2018) University commitment to the sustainable development goals. Sustainable Development Solutions Network. http://ap-unsdsn.org/regional-initiatives/universities-sdgs/university-commitment/ . Accessed 19 Sept 2018

Sepasi S, Rahdari A, Rexhepi G (2017) Developing a sustainability reporting assessment tool for higher education institutions: The University of California. Sustain Dev 1–11

Stephens JC, Hernandez ME, Roman M, Graham AC, Scholz RW (2008) Higher education as a change agent for sustainability indifferent cultures and contexts. Int J Sustain High Educ 9(3):317–338

Thomas I (2004) Sustainability in tertiary curricula: what is stopping it happening? Int J Sustain High Educ 5(1):33–47

ULSF (2018) Talloires declaration signatories list. University Leaders for a Sustainable Future. http://ulsf.org/talloires-declaration/ . Accessed 21 Aug 2018

Vladimirova K, Le Blanc D (2016) Exploring links between education and sustainable development goals through the lens of UN flagship reports. Sustain Dev 24(4):254–271

Wyness L, Sterling S (2015) Reviewing the incidence and status of sustainability in degree programmes at Plymouth University. Int J Sustain High Educ 16(2):237–250

Yin RK (2012) Applications of case study research, 3rd edn. Sage Publications Inc., USA, 49 pp

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, PO Box 6811, Cairns, QLD, 4870, Australia

Colin J. Macgregor

James Cook University, PO Box 6811, Cairns, QLD, 4870, Australia

Adam Connell, Kerryn O’Conor & Marenn Sagar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Colin J. Macgregor .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability Science and Research, HAW Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Department of Chemistry, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Macgregor, C.J., Connell, A., O’Conor, K., Sagar, M. (2019). Using the Learning in Future Environments (LiFE) Index to Assess James Cook University’s Progress in Supporting and Embedding Sustainability. In: Leal Filho, W., Bardi, U. (eds) Sustainability on University Campuses: Learning, Skills Building and Best Practices. World Sustainability Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15864-4_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15864-4_10

Published : 04 June 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-15863-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-15864-4

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

10 Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

A case study in academic research is a detailed and in-depth examination of a specific instance or event, generally conducted through a qualitative approach to data.

The most common case study definition that I come across is is Robert K. Yin’s (2003, p. 13) quote provided below:

“An empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident.”

Researchers conduct case studies for a number of reasons, such as to explore complex phenomena within their real-life context, to look at a particularly interesting instance of a situation, or to dig deeper into something of interest identified in a wider-scale project.

While case studies render extremely interesting data, they have many limitations and are not suitable for all studies. One key limitation is that a case study’s findings are not usually generalizable to broader populations because one instance cannot be used to infer trends across populations.

Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

1. in-depth analysis of complex phenomena.

Case study design allows researchers to delve deeply into intricate issues and situations.

By focusing on a specific instance or event, researchers can uncover nuanced details and layers of understanding that might be missed with other research methods, especially large-scale survey studies.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue,

“It allows that particular event to be studies in detail so that its unique qualities may be identified.”

This depth of analysis can provide rich insights into the underlying factors and dynamics of the studied phenomenon.

2. Holistic Understanding

Building on the above point, case studies can help us to understand a topic holistically and from multiple angles.

This means the researcher isn’t restricted to just examining a topic by using a pre-determined set of questions, as with questionnaires. Instead, researchers can use qualitative methods to delve into the many different angles, perspectives, and contextual factors related to the case study.

We can turn to Lee and Saunders (2017) again, who notes that case study researchers “develop a deep, holistic understanding of a particular phenomenon” with the intent of deeply understanding the phenomenon.

3. Examination of rare and Unusual Phenomena

We need to use case study methods when we stumble upon “rare and unusual” (Lee & Saunders, 2017) phenomena that would tend to be seen as mere outliers in population studies.

Take, for example, a child genius. A population study of all children of that child’s age would merely see this child as an outlier in the dataset, and this child may even be removed in order to predict overall trends.

So, to truly come to an understanding of this child and get insights into the environmental conditions that led to this child’s remarkable cognitive development, we need to do an in-depth study of this child specifically – so, we’d use a case study.

4. Helps Reveal the Experiences of Marginalzied Groups

Just as rare and unsual cases can be overlooked in population studies, so too can the experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of marginalized groups.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue, “case studies are also extremely useful in helping the expression of the voices of people whose interests are often ignored.”

Take, for example, the experiences of minority populations as they navigate healthcare systems. This was for many years a “hidden” phenomenon, not examined by researchers. It took case study designs to truly reveal this phenomenon, which helped to raise practitioners’ awareness of the importance of cultural sensitivity in medicine.

5. Ideal in Situations where Researchers cannot Control the Variables

Experimental designs – where a study takes place in a lab or controlled environment – are excellent for determining cause and effect . But not all studies can take place in controlled environments (Tetnowski, 2015).

When we’re out in the field doing observational studies or similar fieldwork, we don’t have the freedom to isolate dependent and independent variables. We need to use alternate methods.

Case studies are ideal in such situations.

A case study design will allow researchers to deeply immerse themselves in a setting (potentially combining it with methods such as ethnography or researcher observation) in order to see how phenomena take place in real-life settings.

6. Supports the generation of new theories or hypotheses

While large-scale quantitative studies such as cross-sectional designs and population surveys are excellent at testing theories and hypotheses on a large scale, they need a hypothesis to start off with!

This is where case studies – in the form of grounded research – come in. Often, a case study doesn’t start with a hypothesis. Instead, it ends with a hypothesis based upon the findings within a singular setting.

The deep analysis allows for hypotheses to emerge, which can then be taken to larger-scale studies in order to conduct further, more generalizable, testing of the hypothesis or theory.

7. Reveals the Unexpected

When a largescale quantitative research project has a clear hypothesis that it will test, it often becomes very rigid and has tunnel-vision on just exploring the hypothesis.

Of course, a structured scientific examination of the effects of specific interventions targeted at specific variables is extermely valuable.

But narrowly-focused studies often fail to shine a spotlight on unexpected and emergent data. Here, case studies come in very useful. Oftentimes, researchers set their eyes on a phenomenon and, when examining it closely with case studies, identify data and come to conclusions that are unprecedented, unforeseen, and outright surprising.

As Lars Meier (2009, p. 975) marvels, “where else can we become a part of foreign social worlds and have the chance to become aware of the unexpected?”

Disadvantages

1. not usually generalizable.

Case studies are not generalizable because they tend not to look at a broad enough corpus of data to be able to infer that there is a trend across a population.

As Yang (2022) argues, “by definition, case studies can make no claims to be typical.”

Case studies focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. They explore the context, nuances, and situational factors that have come to bear on the case study. This is really useful for bringing to light important, new, and surprising information, as I’ve already covered.

But , it’s not often useful for generating data that has validity beyond the specific case study being examined.

2. Subjectivity in interpretation

Case studies usually (but not always) use qualitative data which helps to get deep into a topic and explain it in human terms, finding insights unattainable by quantitative data.

But qualitative data in case studies relies heavily on researcher interpretation. While researchers can be trained and work hard to focus on minimizing subjectivity (through methods like triangulation), it often emerges – some might argue it’s innevitable in qualitative studies.

So, a criticism of case studies could be that they’re more prone to subjectivity – and researchers need to take strides to address this in their studies.

3. Difficulty in replicating results

Case study research is often non-replicable because the study takes place in complex real-world settings where variables are not controlled.

So, when returning to a setting to re-do or attempt to replicate a study, we often find that the variables have changed to such an extent that replication is difficult. Furthermore, new researchers (with new subjective eyes) may catch things that the other readers overlooked.

Replication is even harder when researchers attempt to replicate a case study design in a new setting or with different participants.

Comprehension Quiz for Students

Question 1: What benefit do case studies offer when exploring the experiences of marginalized groups?

a) They provide generalizable data. b) They help express the voices of often-ignored individuals. c) They control all variables for the study. d) They always start with a clear hypothesis.

Question 2: Why might case studies be considered ideal for situations where researchers cannot control all variables?

a) They provide a structured scientific examination. b) They allow for generalizability across populations. c) They focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. d) They allow for deep immersion in real-life settings.

Question 3: What is a primary disadvantage of case studies in terms of data applicability?

a) They always focus on the unexpected. b) They are not usually generalizable. c) They support the generation of new theories. d) They provide a holistic understanding.

Question 4: Why might case studies be considered more prone to subjectivity?

a) They always use quantitative data. b) They heavily rely on researcher interpretation, especially with qualitative data. c) They are always replicable. d) They look at a broad corpus of data.

Question 5: In what situations are experimental designs, such as those conducted in labs, most valuable?

a) When there’s a need to study rare and unusual phenomena. b) When a holistic understanding is required. c) When determining cause-and-effect relationships. d) When the study focuses on marginalized groups.

Question 6: Why is replication challenging in case study research?

a) Because they always use qualitative data. b) Because they tend to focus on a broad corpus of data. c) Due to the changing variables in complex real-world settings. d) Because they always start with a hypothesis.

Lee, B., & Saunders, M. N. K. (2017). Conducting Case Study Research for Business and Management Students. SAGE Publications.

Meir, L. (2009). Feasting on the Benefits of Case Study Research. In Mills, A. J., Wiebe, E., & Durepos, G. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (Vol. 2). London: SAGE Publications.

Tetnowski, J. (2015). Qualitative case study research design. Perspectives on fluency and fluency disorders , 25 (1), 39-45. ( Source )

Yang, S. L. (2022). The War on Corruption in China: Local Reform and Innovation . Taylor & Francis.

Yin, R. (2003). Case Study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Positive Psychology Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Animism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Magical Thinking Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Social-Emotional Learning (Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons)

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The value of embedding work-integrated learning and other transitionary supports into the first year curriculum: Perspectives of first year subject coordinators

- Hannah Milliken University of Wollongong, Australia http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7695-712X

- Bonnie Dean University of Wollongong, Australia http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2057-9529

- Michelle J. Eady University of Wollongong, Australia http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5624-0407

The first year of university, also known as the first year experience (FYE), is a crucial time for students as they learn a range of new practices that enable them to study and pursue a discipline or profession of interest. The function of this transitionary time however in relation to providing both a successful transition into university as well as an orientation to the profession is under-developed. Work-integrated learning is a leading pedagogy in tertiary institutions to build student’s career-readiness by applying theory within work experiences. However, despite the growth of WIL across discipline contexts, little is known about the prevalence and impact of WIL practices within the first year of tertiary study. The purpose of this study was to explore the perspectives of those who design and facilitate first year subjects on the value of embedding WIL and other transitionary supports into the first year curriculum. A qualitative case study was employed, with interviews from ten first-year subject coordinators within a single degree and institution. The findings reveal three crucial areas of transition in the first year: Transition into learning, Transition into being a student, and Transition into becoming a professional . Recommendations centre on benefits of a whole-of-course approach to transition and WIL for developing students with the necessary knowledge and skills to succeed both at university and into the workplace.

Author Biographies

- Hannah Milliken, University of Wollongong, Australia School of Nursing, University of Wollongong

School of Nursing, University of Wollongong

Aprile, K.T., & Knight, B.A. (2020). The WIL to learn: students’ perspectives on the impact of work-integrated learning placements on their professional readiness. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(5), 869–882. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1695754

Ayala, J. C., & Manzano, G. (2018). Academic performance of first-year university students: the influence of resilience and engagement. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(7), 1321–1335. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2018.1502258

Baik, C., Naylor, R., Arkoudis, S., & Dabrowski, A. (2019). Examining the experiences of first-year students with low tertiary admission scores in Australian universities. Studies in Higher Education, 44(3), 526–538. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1383376

Bates, G.W., Rixon, A., Carbone, A., & Pilgrim, C. (2019). Beyond employability skills: Developing professional purpose. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(1), 7–26. doi:10.21153/jtlge2019vol10no1art794

Billett, S. (2009). Realising the educational worth of integrating work experiences in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 34(7), 827–843. doi: 10.1080/03075070802706561

Bowles, M., Ghosh, S., & Thomas, L. (2020). Future-proofing accounting professionals: Ensuring graduate employability and future readiness. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 11(1), 1–21. doi:10.21153/jtlge2020vol11no1art886

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Briggs, A. R. J., Clark, J., & Hall, I. (2012). Building bridges: Understanding student transition to university. Quality in Higher Education, 18(1), 3–21. doi:10.1080/13538322.2011.614468

Cheng, M., Barnes, G., Edwards, C. & Valyrakis, M. (2015a). Transition skills and strategies: Key transition skills at the different transition points. Glasgow: The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education.

Cheng, M., Barnes, G., Edwards, C. & Valyrakis, M. (2015b). Transition skills and strategies: Transition models and how students experience change. Glasgow: The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education.

Coll, R.K., & Chapman, R. (2000). Choices of methodology for cooperative education researchers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 1(1), 1–8.

Cooper, L., Orrell, J., & Bowden, M. (2010). Work integrated learning: A guide to effective practice. London: Routledge.

Dean, B.A., & Sykes, C. (2020). How students learn of placement: Transitioning placement practices in work-integrated learning. Vocations & Learning. doi: 10.1007/s12186-020-09257-x

Dean, B.A., Eady, M.J., & Yanamandram, V. (2020). Advancing non-placement work-integrated learning across the degree. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice. 17(4). https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol17/iss4/1

Dean, B.A., Yanamandram, V., Eady, M.J., Moroney, T., O’Donnell, N., & Glover-Chambers, T. (2020). An institutional framework for scaffolding work-integrated learning across a degree. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice. 17(4). https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol17/iss4/6

Edwards, D., Perkins, K., Pearce, J., & Hong, J. (2015). Work integrated learning in STEM in Australian universities. Canberra: Office of Chief Scientist & Australian Council for Educational Research.

Fernandez, M.F.P., Araujo, A.M., Vacas, C.T., Almeida, L.S., & Gonzalez, M.S.R. (2017). Predictors of students’ adjustment during transition to university in Spain. Psicothema, 29(1), 67–72.

Ferns, S., Campbell, M., & Zegwaard, K. (2014). Work integrated learning. In Ferns, S. (Ed) HERDSA guide: Work integrated learning in the curriculum (pp. 1–6). Milperra: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia.

Ferns, S., & Lilly, L. (2016). Driving institutional engagement in WIL: Enhancing graduate employability. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 6(1), 116–133. doi:10.21153/jtlge2015vol6no1art577

Fleming, J., & Zegwaard, K. E. (2018). Methodologies, methods and ethical considerations for conducting research in work-integrated learning. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 19(3), 205–213.

Gibney, A., Moore, N., Murphy, F., & O’Sullivan, S. (2011). The first semester of university life; ‘will I be able to manage it at all?’ Higher Education, 62(3), 351–366. doi:10.1007/s10734-010-9392-9

Gillham, B. (2000). Research interview. London and New York: A&C Black.

Godden, H., Eady, M.J., & Dean, B.A. (forthcoming). Practices and perspectives of first year WIL activities: A case study of primary teacher education, in T. Gerhardt (Ed.) Applications of work integrated learning gen Z and Y students. IGI Global: London.

Hefner, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2009). Social support and mental health among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(4), 491–499. doi:10.1037/a0016918

Hinchliffe, G., & Jolly, A. (2011). Graduate identity and employability. British Educational Research Journal, 37(4), 563–584.

Hodkinson, P., & Hodkinson, H. (2001). The strengths and limitations of case study research. Paper presented at the Learning and Skills Development Agency Conference at Cambridge.

Jackson, D., Fleming, J., & Rowe, A. (2019). Enabling the transfer of skills and knowledge across classroom and work contexts. Vocations and Learning, 12(3), 459-478. doi:10.1007/s12186-019-09224-1

Jindal-Snape, D. (2010). Educational transitions: Moving stories from around the world. New York: Routledge.

Julal, F. S. (2016). Predictors of undergraduate students’ university support service use during the first year of university. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 44(4), 371–381. doi:10.1080/03069885.2015.1119232

Kift, S. M. (2004). Organising first year engagement around learning: Formal and informal curriculum intervention. Paper presented at the 8th Pacific Rim First Year in Higher Education Conference, ―Dealing with Diversity.ǁ Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved February 20, 2010, from http://www.fyhe.com.au/past_papers/Papers04/Sally%20Kift_paper.doc

Kift, S. (2009). Articulating a transition pedagogy to scaffold and to enhance the first year student learning experience in Australian higher education: Final report for ALTC senior fellowship program: Australian Learning and Teaching Council Strawberry Hills, NSW.

Kift, S. (2015). A decade of transition pedagogy: A quantum leap in conceptualising the first year experience. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 2(1), 51–86.

Kornbluh, M. (2015). Combatting challenges to establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(4), 397–414. doi:10.1080/14780887.2015.1021941

Krause, K. L., & Coates, H. (2008). Students’ engagement in first‐year university. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5), 493–505. doi: 10.1080/02602930701698892

Li, J., Han, X., Wang, W., Sun, G., & Cheng, Z. (2018). How social support influences university students' academic achievement and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of self-esteem. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 120–126. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2017.11.016

Lincoln, Y.S., & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications

Lucas, P., Fleming, J., & Bhosale, J. (2018). The utility of case study as a methodology for work-integrated learning research. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 19(3), 215–222.

McIlveen, P., Brooks, S., Lichtenberg, A., Smith, M., Torjul, P., & Tyler, J. (2011). Perceptions of Career Development Learning and Work-Integrated Learning in Australian Higher Education. Australian Journal of Career Development, 20(1), 32–41. doi:10.1177/103841621102000105

Nelson, K. J., Clarke, J. A., Kift, S. M., & Creagh, T. A. (2011). Trends in policies, programs and practices in the Australasian First Year Experience literature 2000-2010. The First Year in Higher Education Research Series on Evidence-based Practice. Number 1.

Orrell, J. (2004). Work-integrated learning programmes: Management and educational quality. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Australian Universities Quality Forum.

Patrick, C.-J., Peach, D., Pocknee, C., Webb, F., Fletcher, M., & Pretto, G. (2008). The WIL (Work Integrated Learning) report: A national scoping study. Queensland: Queensland University of Technology.

Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. CA: Thousand Oakes.

Ramsaroop, S., & Petersen, N. (2020). Building professional competencies through a service learning ‘gallery walk’ in primary school teacher education. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 17(4).

Rowe, A. D., & Zegwaard, K. E. (2017). Developing graduate employability skills and attributes: Curriculum enhancement through work-integrated learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 18(2), 87–99.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017–1067. doi: 10.1037/bul0000058

Saunders, V., & Zuzel, K. (2010). Evaluating employability skills: Employer and student perceptions. Bioscience education, 15(1), 1–15. Doi: 10.3108/beej.15.2

Silva, P., Lopes, B., Costa, M., Melo, A. I., Dias, G. P., Brito, E., & Seabra, D. (2018). The million-dollar question: Can internships boost employment? Studies in Higher Education, 43(1), 2–21. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1144181

Soiferman, L. K. (2017). Students' perceptions of their first-year university experience: What universities need to know. Canada: University of Winnepeg. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573978.pdf

Sotiriadou, P., Logan, D., Daly, A., & Guest, R. (2020). The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skill development and employability. Studies in Higher Education, 45(11), 2132–2148.

van Rooij, E. C., Jansen, E. P., & van de Grift, W. J. (2018). First-year university students’ academic success:The importance of academic adjustment. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 33(4), 749–767. Doi: 10.1007/s10212-017-0347-8

Winchester-Seeto, T. & Piggott, L. (2020). ‘Workplace’ or workforce: What are we preparing students for? Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 17(4), 1-6. https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol17/iss4/11

Young, K., Palmer, S., & Campbell, M. (2017). Good WIL hunting: Building capacity for curriculum re-design. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 8(1), 215–232. doi: 10.21153/jtlge2017vol8no1art670

Copyright Notice .

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Michelle J. Eady, Joel Keen, Employability readiness for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students: Yarning Circles as a methodological approach to illuminate student voice , Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability: Vol. 12 No. 2 (2021)

- Bonnie Amelia Dean, Sarah Ryan, Tracey Glover-Chambers , Conor West, Michelle J. Eady, Venkata Yanamandram, Tracey Moroney, Nuala O’Donnell, Career development learning in the curriculum: What is an academic’s role? , Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability: Vol. 13 No. 1 (2022)

Make a Submission

Case Study Research Method in Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Case studies are in-depth investigations of a person, group, event, or community. Typically, data is gathered from various sources using several methods (e.g., observations & interviews).

The case study research method originated in clinical medicine (the case history, i.e., the patient’s personal history). In psychology, case studies are often confined to the study of a particular individual.

The information is mainly biographical and relates to events in the individual’s past (i.e., retrospective), as well as to significant events that are currently occurring in his or her everyday life.

The case study is not a research method, but researchers select methods of data collection and analysis that will generate material suitable for case studies.

Freud (1909a, 1909b) conducted very detailed investigations into the private lives of his patients in an attempt to both understand and help them overcome their illnesses.

This makes it clear that the case study is a method that should only be used by a psychologist, therapist, or psychiatrist, i.e., someone with a professional qualification.

There is an ethical issue of competence. Only someone qualified to diagnose and treat a person can conduct a formal case study relating to atypical (i.e., abnormal) behavior or atypical development.

Famous Case Studies

- Anna O – One of the most famous case studies, documenting psychoanalyst Josef Breuer’s treatment of “Anna O” (real name Bertha Pappenheim) for hysteria in the late 1800s using early psychoanalytic theory.

- Little Hans – A child psychoanalysis case study published by Sigmund Freud in 1909 analyzing his five-year-old patient Herbert Graf’s house phobia as related to the Oedipus complex.

- Bruce/Brenda – Gender identity case of the boy (Bruce) whose botched circumcision led psychologist John Money to advise gender reassignment and raise him as a girl (Brenda) in the 1960s.

- Genie Wiley – Linguistics/psychological development case of the victim of extreme isolation abuse who was studied in 1970s California for effects of early language deprivation on acquiring speech later in life.

- Phineas Gage – One of the most famous neuropsychology case studies analyzes personality changes in railroad worker Phineas Gage after an 1848 brain injury involving a tamping iron piercing his skull.

Clinical Case Studies

- Studying the effectiveness of psychotherapy approaches with an individual patient

- Assessing and treating mental illnesses like depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD

- Neuropsychological cases investigating brain injuries or disorders

Child Psychology Case Studies

- Studying psychological development from birth through adolescence

- Cases of learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, ADHD

- Effects of trauma, abuse, deprivation on development

Types of Case Studies

- Explanatory case studies : Used to explore causation in order to find underlying principles. Helpful for doing qualitative analysis to explain presumed causal links.

- Exploratory case studies : Used to explore situations where an intervention being evaluated has no clear set of outcomes. It helps define questions and hypotheses for future research.

- Descriptive case studies : Describe an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred. It is helpful for illustrating certain topics within an evaluation.

- Multiple-case studies : Used to explore differences between cases and replicate findings across cases. Helpful for comparing and contrasting specific cases.

- Intrinsic : Used to gain a better understanding of a particular case. Helpful for capturing the complexity of a single case.

- Collective : Used to explore a general phenomenon using multiple case studies. Helpful for jointly studying a group of cases in order to inquire into the phenomenon.

Where Do You Find Data for a Case Study?

There are several places to find data for a case study. The key is to gather data from multiple sources to get a complete picture of the case and corroborate facts or findings through triangulation of evidence. Most of this information is likely qualitative (i.e., verbal description rather than measurement), but the psychologist might also collect numerical data.

1. Primary sources

- Interviews – Interviewing key people related to the case to get their perspectives and insights. The interview is an extremely effective procedure for obtaining information about an individual, and it may be used to collect comments from the person’s friends, parents, employer, workmates, and others who have a good knowledge of the person, as well as to obtain facts from the person him or herself.

- Observations – Observing behaviors, interactions, processes, etc., related to the case as they unfold in real-time.

- Documents & Records – Reviewing private documents, diaries, public records, correspondence, meeting minutes, etc., relevant to the case.

2. Secondary sources

- News/Media – News coverage of events related to the case study.

- Academic articles – Journal articles, dissertations etc. that discuss the case.

- Government reports – Official data and records related to the case context.

- Books/films – Books, documentaries or films discussing the case.

3. Archival records

Searching historical archives, museum collections and databases to find relevant documents, visual/audio records related to the case history and context.

Public archives like newspapers, organizational records, photographic collections could all include potentially relevant pieces of information to shed light on attitudes, cultural perspectives, common practices and historical contexts related to psychology.

4. Organizational records

Organizational records offer the advantage of often having large datasets collected over time that can reveal or confirm psychological insights.

Of course, privacy and ethical concerns regarding confidential data must be navigated carefully.

However, with proper protocols, organizational records can provide invaluable context and empirical depth to qualitative case studies exploring the intersection of psychology and organizations.

- Organizational/industrial psychology research : Organizational records like employee surveys, turnover/retention data, policies, incident reports etc. may provide insight into topics like job satisfaction, workplace culture and dynamics, leadership issues, employee behaviors etc.

- Clinical psychology : Therapists/hospitals may grant access to anonymized medical records to study aspects like assessments, diagnoses, treatment plans etc. This could shed light on clinical practices.

- School psychology : Studies could utilize anonymized student records like test scores, grades, disciplinary issues, and counseling referrals to study child development, learning barriers, effectiveness of support programs, and more.

How do I Write a Case Study in Psychology?

Follow specified case study guidelines provided by a journal or your psychology tutor. General components of clinical case studies include: background, symptoms, assessments, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Interpreting the information means the researcher decides what to include or leave out. A good case study should always clarify which information is the factual description and which is an inference or the researcher’s opinion.

1. Introduction

- Provide background on the case context and why it is of interest, presenting background information like demographics, relevant history, and presenting problem.

- Compare briefly to similar published cases if applicable. Clearly state the focus/importance of the case.

2. Case Presentation

- Describe the presenting problem in detail, including symptoms, duration,and impact on daily life.

- Include client demographics like age and gender, information about social relationships, and mental health history.

- Describe all physical, emotional, and/or sensory symptoms reported by the client.

- Use patient quotes to describe the initial complaint verbatim. Follow with full-sentence summaries of relevant history details gathered, including key components that led to a working diagnosis.

- Summarize clinical exam results, namely orthopedic/neurological tests, imaging, lab tests, etc. Note actual results rather than subjective conclusions. Provide images if clearly reproducible/anonymized.

- Clearly state the working diagnosis or clinical impression before transitioning to management.

3. Management and Outcome

- Indicate the total duration of care and number of treatments given over what timeframe. Use specific names/descriptions for any therapies/interventions applied.

- Present the results of the intervention,including any quantitative or qualitative data collected.

- For outcomes, utilize visual analog scales for pain, medication usage logs, etc., if possible. Include patient self-reports of improvement/worsening of symptoms. Note the reason for discharge/end of care.

4. Discussion

- Analyze the case, exploring contributing factors, limitations of the study, and connections to existing research.

- Analyze the effectiveness of the intervention,considering factors like participant adherence, limitations of the study, and potential alternative explanations for the results.

- Identify any questions raised in the case analysis and relate insights to established theories and current research if applicable. Avoid definitive claims about physiological explanations.

- Offer clinical implications, and suggest future research directions.

5. Additional Items

- Thank specific assistants for writing support only. No patient acknowledgments.

- References should directly support any key claims or quotes included.

- Use tables/figures/images only if substantially informative. Include permissions and legends/explanatory notes.

- Provides detailed (rich qualitative) information.

- Provides insight for further research.

- Permitting investigation of otherwise impractical (or unethical) situations.

Case studies allow a researcher to investigate a topic in far more detail than might be possible if they were trying to deal with a large number of research participants (nomothetic approach) with the aim of ‘averaging’.

Because of their in-depth, multi-sided approach, case studies often shed light on aspects of human thinking and behavior that would be unethical or impractical to study in other ways.

Research that only looks into the measurable aspects of human behavior is not likely to give us insights into the subjective dimension of experience, which is important to psychoanalytic and humanistic psychologists.

Case studies are often used in exploratory research. They can help us generate new ideas (that might be tested by other methods). They are an important way of illustrating theories and can help show how different aspects of a person’s life are related to each other.

The method is, therefore, important for psychologists who adopt a holistic point of view (i.e., humanistic psychologists ).

Limitations

- Lacking scientific rigor and providing little basis for generalization of results to the wider population.

- Researchers’ own subjective feelings may influence the case study (researcher bias).

- Difficult to replicate.

- Time-consuming and expensive.

- The volume of data, together with the time restrictions in place, impacted the depth of analysis that was possible within the available resources.

Because a case study deals with only one person/event/group, we can never be sure if the case study investigated is representative of the wider body of “similar” instances. This means the conclusions drawn from a particular case may not be transferable to other settings.

Because case studies are based on the analysis of qualitative (i.e., descriptive) data , a lot depends on the psychologist’s interpretation of the information she has acquired.

This means that there is a lot of scope for Anna O , and it could be that the subjective opinions of the psychologist intrude in the assessment of what the data means.

For example, Freud has been criticized for producing case studies in which the information was sometimes distorted to fit particular behavioral theories (e.g., Little Hans ).

This is also true of Money’s interpretation of the Bruce/Brenda case study (Diamond, 1997) when he ignored evidence that went against his theory.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studies on hysteria . Standard Edition 2: London.

Curtiss, S. (1981). Genie: The case of a modern wild child .

Diamond, M., & Sigmundson, K. (1997). Sex Reassignment at Birth: Long-term Review and Clinical Implications. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine , 151(3), 298-304

Freud, S. (1909a). Analysis of a phobia of a five year old boy. In The Pelican Freud Library (1977), Vol 8, Case Histories 1, pages 169-306

Freud, S. (1909b). Bemerkungen über einen Fall von Zwangsneurose (Der “Rattenmann”). Jb. psychoanal. psychopathol. Forsch ., I, p. 357-421; GW, VII, p. 379-463; Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis, SE , 10: 151-318.

Harlow J. M. (1848). Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 39 , 389–393.

Harlow, J. M. (1868). Recovery from the Passage of an Iron Bar through the Head . Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society. 2 (3), 327-347.

Money, J., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1972). Man & Woman, Boy & Girl : The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Money, J., & Tucker, P. (1975). Sexual signatures: On being a man or a woman.

Further Information

- Case Study Approach

- Case Study Method

- Enhancing the Quality of Case Studies in Health Services Research

- “We do things together” A case study of “couplehood” in dementia

- Using mixed methods for evaluating an integrative approach to cancer care: a case study

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Med Educ

- v.8(4); 2019 Aug

Limited by our limitations

Paula t. ross.

Medical School, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI USA

Nikki L. Bibler Zaidi

Study limitations represent weaknesses within a research design that may influence outcomes and conclusions of the research. Researchers have an obligation to the academic community to present complete and honest limitations of a presented study. Too often, authors use generic descriptions to describe study limitations. Including redundant or irrelevant limitations is an ineffective use of the already limited word count. A meaningful presentation of study limitations should describe the potential limitation, explain the implication of the limitation, provide possible alternative approaches, and describe steps taken to mitigate the limitation. This includes placing research findings within their proper context to ensure readers do not overemphasize or minimize findings. A more complete presentation will enrich the readers’ understanding of the study’s limitations and support future investigation.

Introduction

Regardless of the format scholarship assumes, from qualitative research to clinical trials, all studies have limitations. Limitations represent weaknesses within the study that may influence outcomes and conclusions of the research. The goal of presenting limitations is to provide meaningful information to the reader; however, too often, limitations in medical education articles are overlooked or reduced to simplistic and minimally relevant themes (e.g., single institution study, use of self-reported data, or small sample size) [ 1 ]. This issue is prominent in other fields of inquiry in medicine as well. For example, despite the clinical implications, medical studies often fail to discuss how limitations could have affected the study findings and interpretations [ 2 ]. Further, observational research often fails to remind readers of the fundamental limitation inherent in the study design, which is the inability to attribute causation [ 3 ]. By reporting generic limitations or omitting them altogether, researchers miss opportunities to fully communicate the relevance of their work, illustrate how their work advances a larger field under study, and suggest potential areas for further investigation.

Goals of presenting limitations

Medical education scholarship should provide empirical evidence that deepens our knowledge and understanding of education [ 4 , 5 ], informs educational practice and process, [ 6 , 7 ] and serves as a forum for educating other researchers [ 8 ]. Providing study limitations is indeed an important part of this scholarly process. Without them, research consumers are pressed to fully grasp the potential exclusion areas or other biases that may affect the results and conclusions provided [ 9 ]. Study limitations should leave the reader thinking about opportunities to engage in prospective improvements [ 9 – 11 ] by presenting gaps in the current research and extant literature, thereby cultivating other researchers’ curiosity and interest in expanding the line of scholarly inquiry [ 9 ].

Presenting study limitations is also an ethical element of scientific inquiry [ 12 ]. It ensures transparency of both the research and the researchers [ 10 , 13 , 14 ], as well as provides transferability [ 15 ] and reproducibility of methods. Presenting limitations also supports proper interpretation and validity of the findings [ 16 ]. A study’s limitations should place research findings within their proper context to ensure readers are fully able to discern the credibility of a study’s conclusion, and can generalize findings appropriately [ 16 ].

Why some authors may fail to present limitations

As Price and Murnan [ 8 ] note, there may be overriding reasons why researchers do not sufficiently report the limitations of their study. For example, authors may not fully understand the importance and implications of their study’s limitations or assume that not discussing them may increase the likelihood of publication. Word limits imposed by journals may also prevent authors from providing thorough descriptions of their study’s limitations [ 17 ]. Still another possible reason for excluding limitations is a diffusion of responsibility in which some authors may incorrectly assume that the journal editor is responsible for identifying limitations. Regardless of reason or intent, researchers have an obligation to the academic community to present complete and honest study limitations.

A guide to presenting limitations

The presentation of limitations should describe the potential limitations, explain the implication of the limitations, provide possible alternative approaches, and describe steps taken to mitigate the limitations. Too often, authors only list the potential limitations, without including these other important elements.

Describe the limitations

When describing limitations authors should identify the limitation type to clearly introduce the limitation and specify the origin of the limitation. This helps to ensure readers are able to interpret and generalize findings appropriately. Here we outline various limitation types that can occur at different stages of the research process.

Study design

Some study limitations originate from conscious choices made by the researcher (also known as delimitations) to narrow the scope of the study [ 1 , 8 , 18 ]. For example, the researcher may have designed the study for a particular age group, sex, race, ethnicity, geographically defined region, or some other attribute that would limit to whom the findings can be generalized. Such delimitations involve conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions made during the development of the study plan, which may represent a systematic bias intentionally introduced into the study design or instrument by the researcher [ 8 ]. The clear description and delineation of delimitations and limitations will assist editors and reviewers in understanding any methodological issues.

Data collection

Study limitations can also be introduced during data collection. An unintentional consequence of human subjects research is the potential of the researcher to influence how participants respond to their questions. Even when appropriate methods for sampling have been employed, some studies remain limited by the use of data collected only from participants who decided to enrol in the study (self-selection bias) [ 11 , 19 ]. In some cases, participants may provide biased input by responding to questions they believe are favourable to the researcher rather than their authentic response (social desirability bias) [ 20 – 22 ]. Participants may influence the data collected by changing their behaviour when they are knowingly being observed (Hawthorne effect) [ 23 ]. Researchers—in their role as an observer—may also bias the data they collect by allowing a first impression of the participant to be influenced by a single characteristic or impression of another characteristic either unfavourably (horns effect) or favourably (halo effort) [ 24 ].

Data analysis

Study limitations may arise as a consequence of the type of statistical analysis performed. Some studies may not follow the basic tenets of inferential statistical analyses when they use convenience sampling (i.e. non-probability sampling) rather than employing probability sampling from a target population [ 19 ]. Another limitation that can arise during statistical analyses occurs when studies employ unplanned post-hoc data analyses that were not specified before the initial analysis [ 25 ]. Unplanned post-hoc analysis may lead to statistical relationships that suggest associations but are no more than coincidental findings [ 23 ]. Therefore, when unplanned post-hoc analyses are conducted, this should be clearly stated to allow the reader to make proper interpretation and conclusions—especially when only a subset of the original sample is investigated [ 23 ].

Study results

The limitations of any research study will be rooted in the validity of its results—specifically threats to internal or external validity [ 8 ]. Internal validity refers to reliability or accuracy of the study results [ 26 ], while external validity pertains to the generalizability of results from the study’s sample to the larger, target population [ 8 ].

Examples of threats to internal validity include: effects of events external to the study (history), changes in participants due to time instead of the studied effect (maturation), systematic reduction in participants related to a feature of the study (attrition), changes in participant responses due to repeatedly measuring participants (testing effect), modifications to the instrument (instrumentality) and selecting participants based on extreme scores that will regress towards the mean in repeat tests (regression to the mean) [ 27 ].

Threats to external validity include factors that might inhibit generalizability of results from the study’s sample to the larger, target population [ 8 , 27 ]. External validity is challenged when results from a study cannot be generalized to its larger population or to similar populations in terms of the context, setting, participants and time [ 18 ]. Therefore, limitations should be made transparent in the results to inform research consumers of any known or potentially hidden biases that may have affected the study and prevent generalization beyond the study parameters.

Explain the implication(s) of each limitation

Authors should include the potential impact of the limitations (e.g., likelihood, magnitude) [ 13 ] as well as address specific validity implications of the results and subsequent conclusions [ 16 , 28 ]. For example, self-reported data may lead to inaccuracies (e.g. due to social desirability bias) which threatens internal validity [ 19 ]. Even a researcher’s inappropriate attribution to a characteristic or outcome (e.g., stereotyping) can overemphasize (either positively or negatively) unrelated characteristics or outcomes (halo or horns effect) and impact the internal validity [ 24 ]. Participants’ awareness that they are part of a research study can also influence outcomes (Hawthorne effect) and limit external validity of findings [ 23 ]. External validity may also be threatened should the respondents’ propensity for participation be correlated with the substantive topic of study, as data will be biased and not represent the population of interest (self-selection bias) [ 29 ]. Having this explanation helps readers interpret the results and generalize the applicability of the results for their own setting.

Provide potential alternative approaches and explanations

Often, researchers use other studies’ limitations as the first step in formulating new research questions and shaping the next phase of research. Therefore, it is important for readers to understand why potential alternative approaches (e.g. approaches taken by others exploring similar topics) were not taken. In addition to alternative approaches, authors can also present alternative explanations for their own study’s findings [ 13 ]. This information is valuable coming from the researcher because of the direct, relevant experience and insight gained as they conducted the study. The presentation of alternative approaches represents a major contribution to the scholarly community.

Describe steps taken to minimize each limitation