An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Acad Pathol

- v.7; Jan-Dec 2020

Educational Case: Acute Cystitis

Ryan l. frazier.

1 Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, USA. Huppmann is now at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, Greenville, SC, USA.

Alison R. Huppmann

The following fictional case is intended as a learning tool within the Pathology Competencies for Medical Education (PCME), a set of national standards for teaching pathology. These are divided into three basic competencies: Disease Mechanisms and Processes, Organ System Pathology, and Diagnostic Medicine and Therapeutic Pathology. For additional information, and a full list of learning objectives for all three competencies, see http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2374289517715040 . 1

Primary Objective

Objective UTB2.1 : Acute Cystitis . Discuss the typical clinical symptomatology of acute cystitis and the organisms commonly causing this disorder.

Competency 2 Organ System Pathology; Topic UTB: Bladder; Learning Goal 2: Bladder Infection.

Secondary Objectives

Objective M2.11: Urine Studies for Cystitis . Explain the role of urine studies, including culture, in selecting antimicrobial therapy for infectious cystitis.

Competency 3 Diagnostic Medicine and Therapeutic Pathology; Topic M: Microbiology; Learning Goal 2: Antimicrobials.

Objective M2.12: Diagnosis of UTI . Describe a testing strategy for a typical uncomplicated community acquired urinary tract infection (UTI) versus a nosocomial UTI in a patient with a Foley catheter and list the key microbiological tests in diagnosis of UTIs.

Patient Presentation

A 27-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician with a report of urinating more frequently and pain with urination. She denies blood in her urine, fevers, chills, flank pain, and vaginal discharge. She reports having experienced similar symptoms a few years ago and that they went away after a course of antibiotics. The patient has no other past medical problems. Pertinent history reveals she has been sexually active with her boyfriend for the past 4 months and uses condoms for contraception. She reports 2 lifetime partners and no past pregnancies or sexually transmitted diseases. Her last menstrual period was 1 week ago.

Diagnostic Findings, Part 1

On physical exam, the patient is afebrile, normotensive, and non-tachycardic. She appears well on observation. She has a soft, nondistended abdomen with normoactive bowel sounds. On palpation, she has moderate discomfort in her suprapubic region but no costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness. A pelvic exam is normal with no evidence of abnormal vaginal or cervical discharge or inflammation.

Questions/Discussion Points, Part 1

What is the differential diagnosis for this patient which diagnosis is most likely and why.

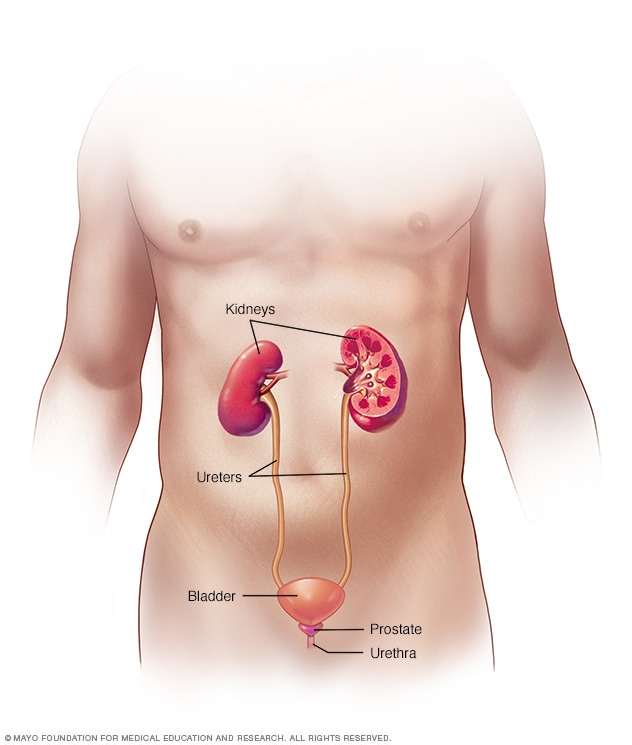

The top entities in the differential diagnosis include a UTI, vaginitis/cervicitis, and pyelonephritis. The most likely diagnosis in this patient is a UTI, specifically, acute cystitis. Classic UTI symptoms include urinary frequency and urgency and dysuria. Other complaints could include suprapubic pain or discomfort, hesitancy, nocturia, and even gross hematuria. Urinary tract infections are classified by the anatomical location in which the infection and inflammation occur. Risk factors that this patient possesses, which will be discussed later, are female sex, age, recent sexual activity, and a history of prior UTI, which we can infer from her report of previous similar symptoms. 2

Vaginitis and cervicitis should also be considered in this patient given her history of sexual activity. However, the patient has no reported vaginal discharge or signs of these infections on pelvic examination. Another important diagnosis to consider is pyelonephritis, which involves infection of the upper urinary tract. This is also not likely given her lack of fever, flank pain, and other key symptoms which will be discussed in a later section.

Is Laboratory Testing Required To Confirm the Diagnosis in This Patient?

Laboratory studies are not needed in this patient due to the high likelihood of a UTI, and empirical treatment can be administered. Thus, the importance of a good history and physical exam is highly emphasized when caring for a patient with a possible UTI. Uncomplicated UTIs are commonly observed and treated in the outpatient setting; they are increasingly being diagnosed without an in-person visit via telephone. 2

Which Populations Are at Higher Risk of Contracting a UTI? Why? Discuss the Terms “Uncomplicated UTI” Versus “Complicated UTI”

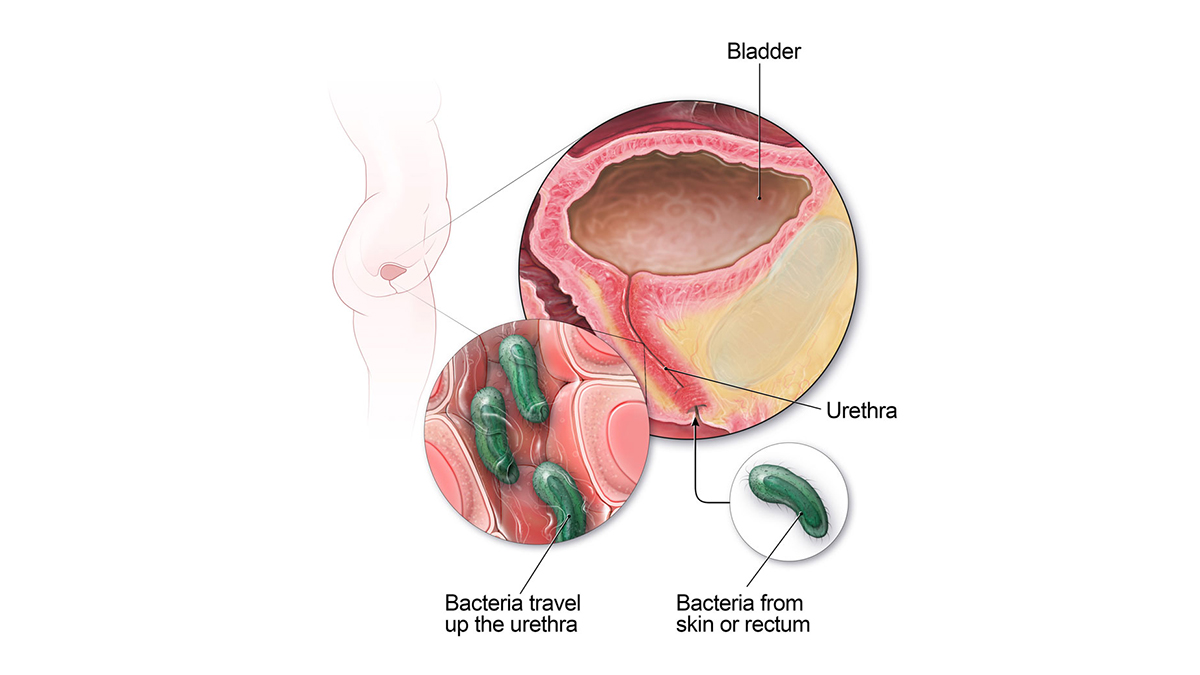

Urinary tract infections are due to the colonization of the urinary tract by microbes. Certain populations are at higher risk of infections of the urinary tract. Women are among those most affected by UTIs, with a lifetime incidence rate of almost 50%. 3 The difference between the sexes is attributed to women’s shorter urethral length. Women who are sexually active are also at risk of UTI due to the proximity of the urethral meatus to the flora-rich anus. If the patient is a premenopausal, otherwise healthy, and nongravid female, as in this case, she has developed an “uncomplicated” infection. 2 , 4

Patients who are predisposed to conditions that make colonization more likely or are exposed to microbes that are more facile in evading the body’s natural protective mechanisms are more apt to contract UTIs, and their infections can be more difficult to treat. These patients have “complicated” infections. Numerous conditions make a patient more susceptible to UTI. These include underlying medical problems or structural abnormalities of the urinary tract such as urinary obstruction, vesicoureteral reflux, underlying urinary tract disease, diabetes, renal papillary necrosis, immunosuppression (medically induced or as a result of HIV infection), treatment with antibiotics, pregnancy, menopause, and spinal cord injuries. 4 The elderly are also at increased risk of UTI, particularly men, many of whom develop obstructive uropathy from benign prostatic hypertrophy. 2 , 4

When Should a Diagnosis of Pyelonephritis Be Suspected?

Infection of the kidney is termed pyelonephritis. These patients tend to present acutely with “upper tract signs,” to include fever, chills, flank pain, and CVA tenderness. Symptoms of lower UTI can also be present; however, this is not usually the case. The clinical presentation may vary and can be life-threatening. In the most severely ill, patients may present in septic shock, with hypotension, tachycardia, and tachypnea, especially when infected with a gram-negative organism. 4

Which Laboratory Studies Can Be Performed on Urine To Evaluate a Potential UTI? What Is the Diagnostic Value of Each Test?

Laboratory tools are commonly utilized in the investigation of UTIs for patients with a complicated UTI, recurrent infections, or an unclear diagnosis based purely on history and physical exam. Again, test results should always be correlated with clinical findings, as false-positive or false-negative results can occur through multiple avenues. Available tests include a urine dipstick, urinalysis with microscopy, and culture and gram stain with sensitivity testing. The first 2 of these have the potential to be performed in physicians’ offices. A clean-catch midstream specimen should be submitted to avoid contamination from vaginal or penile microorganisms. Patients should be given a 2% castile soap towelette and instructed in appropriate specimen collection. Men should cleanse the glans, retracting the foreskin first if uncircumcised. Women should cleanse the periurethral area after spreading the labia. Identification of lactobacilli and epithelial cells from the vagina suggest contamination. 4

General features of the urine can first be examined to include the color, clarity, and odor; but these features are nonspecific. For example, cloudy urine can be caused by the presence of white blood cells and/or bacteria in a UTI; but it can also be caused by numerous other pathologic and non-pathologic substances.

Urine dipstick studies, primarily searching for leukocyte esterase and nitrites, are useful when the pretest probability of UTI is high. Leukocyte esterase is an enzyme possessed by white blood cells. Thus, a positive urine dipstick for leukocyte esterase indicates the presence of inflammatory cells in the patient’s urinary tract. Inflammatory cells in the urine are not specific for a UTI, as leukocytes can also be present in other situations such as glomerulonephritis and vaginal contamination. Nitrite is a breakdown product of nitrates, which are normally found in a healthy patient’s urine. The dipstick test for nitrite is specific for gram-negative organisms which possess an enzyme enabling them to reduce nitrates. It follows, then, that this test is less useful in the setting of potential gram-positive microbe infection. Also notable is that the nitrite test can be falsely negative in a patient with abundant fluid intake and frequent urination. 2 Multiple other factors including medications, diet, and specimen handling can affect urine dipstick results, as can inappropriate handling or expiration of test strips.

Urinalysis with microscopy provides a window into the kidney and urinary tract. The presence of red blood cells, white blood cells, casts, crystals, and bacteria aid in many diagnoses. Specific to UTI, the presence of white blood cells and red blood cells indicates inflammation and, potentially, infection in the urinary tract. 2 Pyuria, the presence of leukocytes in the urine, is not specific to UTIs as noted above; but the absence of leukocytes should cause one to question a diagnosis of UTI unless the culture is positive. The identification of crystals might suggest the presence of renal calculi, which can serve as a nidus for infection. In fact, some stones (eg, struvite) are the direct result of infection with urea-splitting organisms. Overall, urinalysis is useful; however, the clinical history still plays a key role to avoid under- and overdiagnosis. 4

Urine culture is the gold standard diagnostic tool for diagnosing UTIs. 2 , 4 As stated previously, in patients with a convincing clinical history and physical exam consistent with uncomplicated cystitis, no culture is necessary. However, in patients with complicated, severe upper urinary tract, or recurrent UTIs, urine culture should not be foregone, as it is necessary for determining the causative organism and, consequently, for guiding appropriate therapeutic intervention. Furthermore, growth of the organism in culture facilitates sensitivity studies, in which pharmacologic agents are tested on the microbe isolated from the patient. This testing provides medical personnel with information regarding the efficacy of potential therapeutic options in the form of minimal inhibitory concentrations. This information guides narrowing of antibiotic choice from whichever broad-spectrum treatment was initiated when a UTI was first suspected. 2 Some organisms such as Ureaplasma urealyticum may not be grown on routine cultures, so a false-negative result is possible. False-positive results are rare, other than due to contamination, which should be suspected in most cases with growth of multiple types of bacteria or vaginal flora. 4

What Is Asymptomatic Bacteriuria?

The diagnosis of asymptomatic bacteriuria requires 2 criteria: (1) The urine is culture-positive and (2) the patient does not have symptoms or signs of a UTI. The level of bacteria in culture should reach ≥10 5 CFU/mL, although it can be lower in catheterized patients (≥10 2 CFU/mL). Asymptomatic bacteriuria is only treated in some groups of patients, including those who are pregnant or undergoing urologic procedures, as it otherwise does not correlate with symptomatic disease or complications. 2

Which Microorganisms Most Commonly Cause Acute Cystitis?

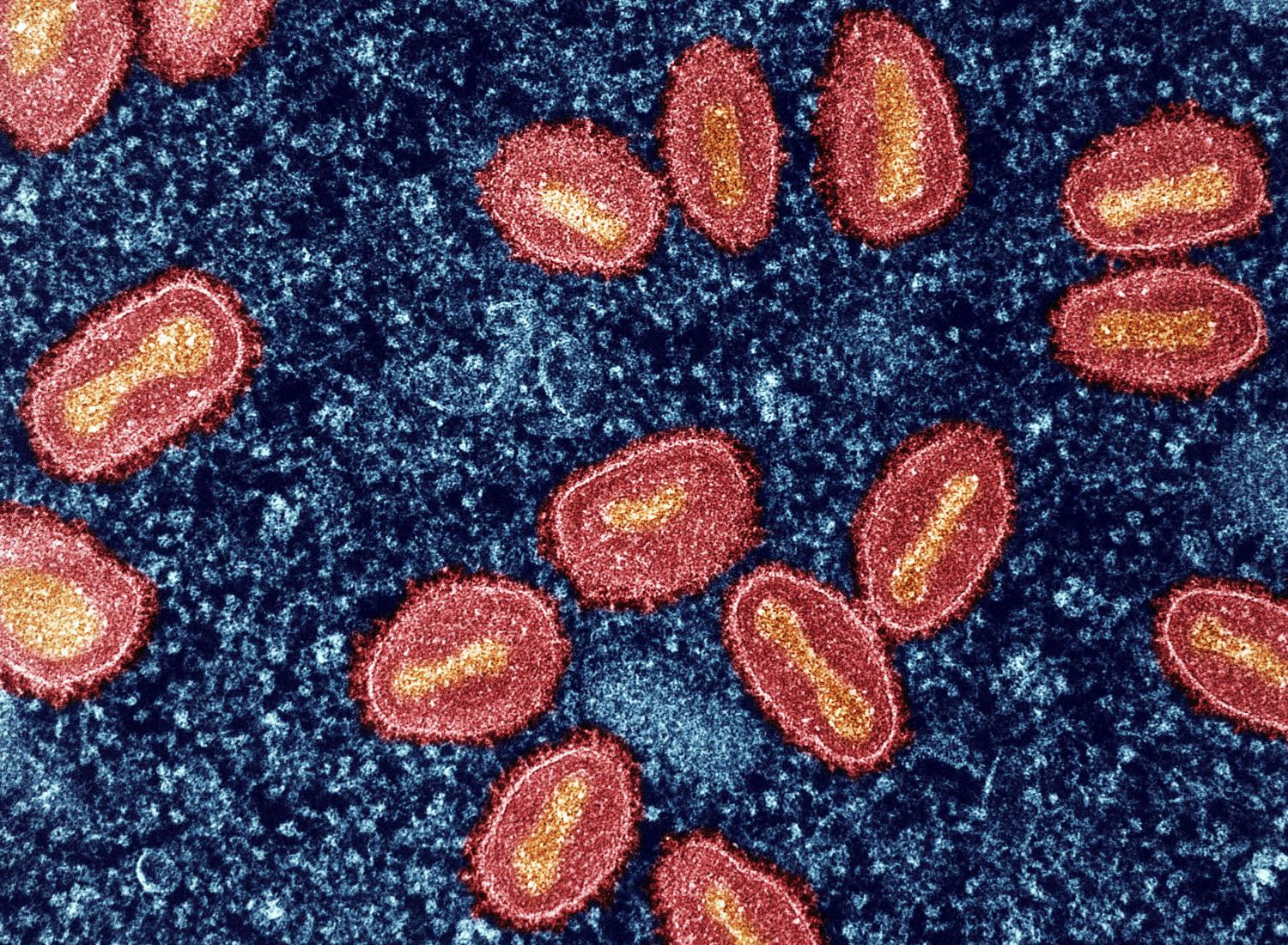

In general, gram-negative aerobic rods are the most commonly isolated pathogens implicated in UTIs. 2 Escherichia coli is the most common causative organism of UTIs, especially in sexually active young women. 2 , 4 Microorganisms such as uropathogenic E coli (UPEC) with an enhanced ability to bind and to adhere to urinary tract epithelia are more capable of causing infection. Adhesins and pili resistant to the innate immune mechanisms of defense are among the advantageous traits that particularly virulent strains of UPEC possess. 4

A variety of other Enterobacteriaceae (discussed below) are also found in the setting of catheter-associated UTIs (CAUTIs). However, gram-positive organisms are clinically significant in some settings. Staphylococcus saprophyticus is not infrequently implicated in uncomplicated UTIs in young, sexually active women. 2 Group B Streptococcus (GBS, Streptococcus agalactiae ) is of particular concern in pregnant patients. In 1 prospective study, GBS was the second most isolated pathogen behind E coli in the urine of asymptomatic bacteriuric pregnant women. 5 Screening pregnant women for asymptomatic bacteriuria plays an important role in decreasing the risk of pyelonephritis during pregnancy. 6 , 7 Table 1 summarizes the typical microorganisms identified in complicated and uncomplicated UTIs along with the appropriate laboratory testing.

Common Causative Organisms and Indicated Laboratory Tests for Patients With Uncomplicated and Complicated Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs).

Abbreviation: STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Discuss CAUTIs and Their Difference From Non-CAUTIs, Including Clinical Features and Causative Microorganisms

Per the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 8 both clinical and laboratory criteria should be met to make the diagnosis of a catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI). The patient should have signs or symptoms of a UTI and no other known source of infection. Culture of the patient’s urine sample should yield greater than 10 3 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL of at least 1 species of bacteria. The cultured urine should be from a single specimen in those patients who are still catheterized. Catheter-associated UTI can also be diagnosed in those whom have had a catheter removed within the preceding 48 hours, in which case a midstream voided urine is the appropriate specimen.

Catheter-associated UTIs are a type of complicated UTI and are among the most common nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections in the United States. 4 Urinary catheters facilitate the ascent of microbes into the urinary tract. There are different methods of catheterization, for example, clean intermittent catheterization, indwelling urethral catheters, and suprapubic catheters. Microorganisms can be introduced during the procedure of catheterization despite the implementation of sterilization methods. Also, without appropriate catheter care, these indwelling devices can become a nidus for infection, permitting various other flora to travel along the tube and into the urinary tract. 4

As previously mentioned, E coli is the most common causative organism of acute cystitis in uncomplicated UTIs. 4 It is also the most commonly isolated organism in CAUTI. 8 , 9 However, patients with catheters are at higher risk of infection by organisms less commonly seen in non-catheterized patients. Patients who are catheterized for both short and long periods of time are at increased risk of infection with fungal organisms as well as Enterobacteriaceae such as Klebsiella , Serratia , Enterobacter , Pseudomonas , Enterococcus , and Proteus species. 4 , 6 , 9 These organisms are exceptionally well-adapted for invasion given the ability many of them possess to form biofilms. The longer a patient is catheterized, the more likely they are to develop bacteriuria, a symptomatic infection, and potentially colonization of the urinary tract. 4 Thus, timely removal of catheters when no longer necessary is wise.

How Should Patients With UTIs Be Treated?

The choice of therapy for UTIs depends on the clinical treatment setting, and whether it is a complicated or uncomplicated UTI. An optimal outpatient antibiotic can be taken orally, has a tolerable side effect profile, and is concentrated to a therapeutic level in the patient’s urine. 4 Antibiotics that fit this profile are appropriate to give patients who have a low risk for infection with a multidrug resistant strain. Options for therapy include nitrofurantoin monohydrate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, fosfomycin, and pivmecillinam. 4 , 10

Recent infectious disease guidelines reflect growing concern for infection with multidrug resistant organisms. 10 When therapy needs to be escalated due to infection with a multidrug resistant organism or tissue-invasive disease with bacteremia, options remain for oral therapy. In these situations, it is advantageous to obtain urine culture and microbe antibiotic sensitivities to better eliminate the infection. If hospitalization is indicated and the patient requires parenteral antibiotics, empiric therapy should be initiated. After microorganism sensitivities return, antibiotic therapy can be narrowed to one of the following: a carbapenem, third-generation cephalosporin, fluoroquinolone, ampicillin, and gentamicin. 4

Pharmacotherapy for complicated UTIs should begin with broad-spectrum therapy and then be narrowed by sensitivities when possible. 4 The grouping which places the patient in the “complicated” category plays a role in treatment selection. For example, UTIs in men typically involve the prostate as well as the bladder, so treatment should target the infection in both organs. Patients who are pregnant require antibiotics that are safe for the fetus. 2 Some complicated UTIs, especially in the case of upper UTIs, are managed inpatient with intravenous antibiotics due to the presence of tissue-invasive disease or bacteremia. In this case, the concentration of antibiotic in the blood and the urine are important. This differs from the treatment of uncomplicated UTIs, which are dependent on the concentration of the pharmacotherapeutic agent in the urine. 4

Potential correction of modifiable risk factors for UTIs, if present, can also be addressed to prevent recurrent infection. This may include correction of an anatomic or structural abnormality of the urinary tract, consideration of alternative birth control types in a woman who uses a diaphragm with spermicide, removing a urinary catheter, or simply counseling a woman to attempt urination after sexual intercourse.

Describe Potential Complications of UTIs

Urinary tract infections can be complicated by several conditions depending on the severity and chronicity of the infection and the implicated organism. Severe upper UTIs can lead to acute kidney injury and, if not treated, can lead to permanent kidney damage and fibrosis. Similarly, upper UTIs can be complicated by renal or perinephric abscess(es). Renal abscesses are most found in patients with preexisting kidney disease. Patients infected by a urea-splitting organism are at risk of struvite stones, which are commonly found in the upper urinary tract. 4

Teaching Points

- Acute cystitis is a form of UTI and commonly presents with urinary frequency, urgency, and dysuria. Uncomplicated cases of UTIs, those seen in otherwise young, healthy, adult women, can be diagnosed by a thorough history and physical exam.

- Urinary tract infections are most often seen in sexually active, young women and older men with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

- Escherichia coli is the most implicated organism in UTIs. Other aerobic gram-negative rods and sometimes gram-positive microorganisms can be implicated, especially in patients with preexisting conditions or indwelling urinary catheters.

- Laboratory investigations, including dipstick tests, urinalysis, and urine culture, can aid physicians in the diagnosis of UTIs when needed and are important to guide effective treatment, especially in complicated UTIs.

- Uncomplicated UTIs can bet treated with outpatient oral antibiotics, with choices to include nitrofurantoin monohydrate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, fosfomycin, and pivmecillinam.

- Complicated UTIs occur in patients at higher risk of infection or in whom the infection may be difficult to treat. Some examples of patients in this category include those with anatomic or other urinary tract obstruction, catheter-associated UTIs, pregnant women, and patients who are immunosuppressed.

- Pyelonephritis is a serious upper UTI which can potentially be life-threatening if not treated promptly.

- Complications of UTIs include renal abscesses, acute kidney injury leading to chronic kidney disease, and struvite calculi.

- Broad-spectrum pharmacotherapy should be initiated for complicated microbial infections of the urinary tract. After sensitivity studies from the patient’s urine return, treatment can be narrowed to avoid the development of multi-drug resistant organisms.

Author’s Note: The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are not necessarily representative of those of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), the Department of Defense (DOD), or the United States Army, Navy, or Air Force.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Ahmed H, Farewell D, Francis NA, Paranjothy S, Butler CC. Risk of adverse outcomes following urinary tract infection in older people with renal impairment: Retrospective cohort study using linked health record data. PLoS Med. 2018; 15:(9) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002652

Bardsley A. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections in older people. Nurs Older People. 2017; 29:(2)32-38 https://doi.org/10.7748/nop.2017.e884

Barnsley Hospital NHS FT/The Rotherham NHS FT. Adult antimicrobial guide. 2022. https://viewer.microguide.global/BHRNFT/ADULT (accessed 13 March 2023)

Bradley S, Sheeran S. Optimal use of Antibiotics for urinary tract infections in long-term care facilities: Successful strategies prevent resident harm. Patient Safety Authority. 2017; 14:(3) http://patientsafety.pa.gov/ADVISORIES/pages/201709_UTI.aspx

Chardavoyne PC, Kasmire KE. Appropriateness of Antibiotic Prescriptions for Urinary Tract Infections. West J Emerg Med. 2020; 21:(3)633-639 https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.1.45944

Deresinski S. Fosfomycin or nitrofurantoin for cystitis?. Infectious Disease Alert: Atlanta. 2018; 37:(9) http://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/fosfomycin-nitrofurantoin-cystitis/docview/2045191847

Doogue MP, Polasek TM. The ABCD of clinical pharmacokinetics. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2013; 4:(1)5-7 https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098612469335

Doyle JF, Schortgen F. Should we treat pyrexia? And how do we do it?. Crit Care. 2016; 20:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1467-2

Fransen F, Melchers MJ, Meletiadis J, Mouton JW. Pharmacodynamics and differential activity of nitrofurantoin against ESBL-positive pathogens involved in urinary tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016; 71:(10)2883-2889 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw212

Geerts AF, Eppenga WL, Heerdink R Ineffectiveness and adverse events of nitrofurantoin in women with urinary tract infection and renal impairment in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013; 69:(9)1701-1707 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1520-x

Greener M. Modified release nitrofurantoin in uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Nurse Prescribing. 2011; 9:(1)19-24 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2011.9.1.19

Confusion in the older patient: a diagnostic approach. 2019. https://www.gmjournal.co.uk/confusion-in-the-older-patient-a-diagnostic-approach (accessed 13 March 2023)

Haasum Y, Fastbom J, Johnell K. Different patterns in use of antibiotics for lower urinary tract infection in institutionalized and home-dwelling elderly: a register-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013; 69:(3)665-671 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1374-7

Health Education England. The Core Capabilities Framework for Advanced Clinical Practice (Nurses) Working in General Practice/Primary Care in England. 2020. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/ACP%20Primary%20Care%20Nurse%20Fwk%202020.pdf (accessed 13 March 2023)

Hoang P, Salbu RL. Updated nitrofurantoin recommendation in the elderly: A closer look at the evidence. Consult Pharm. 2016; 31:(7)381-384 https://doi.org/10.4140/TCP.n.2016.381

Langner JL, Chiang KF, Stafford RS. Current prescribing practices and guideline concordance for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021; 225:(3)272.e1-272.e11 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.04.218

Lajiness R, Lajiness MJ. 50 years on urinary tract infections and treatment-Has much changed?. Urol Nurs. 2019; 39:(5)235-239 https://doi.org/10.7257/1053-816X.2019.39.5.235

Komp Lindgren P, Klockars O, Malmberg C, Cars O. Pharmacodynamic studies of nitrofurantoin against common uropathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015; 70:(4)1076-1082 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dku494

Lovatt P. Legal and ethical implications of non-medical prescribing. Nurse Prescribing. 2010; 8:(7)340-343 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2010.8.7.48941

Malcolm W, Fletcher E, Kavanagh K, Deshpande A, Wiuff C, Marwick C, Bennie M. Risk factors for resistance and MDR in community urine isolates: population-level analysis using the NHS Scotland Infection Intelligence Platform. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018; 73:(1)223-230 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx363

McKinnell JA, Stollenwerk NS, Jung CW, Miller LG. Nitrofurantoin compares favorably to recommended agents as empirical treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in a decision and cost analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011; 86:(6)480-488 https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0800

Medicines.org. Nitrofurantoin. 2022. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/search?q=Nitrofurantoin (accessed 13 March 2023)

NHS England, NHS Improvement. Online library of Quality Service Improvement and Redesign tools. SBAR communication tool – situation, background, assessment, recommendation. 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/qsir-sbar-communication-tool.pdf (accessed 13 March 2023)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NG5: Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 (accessed 13 March 2023)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection (lower) – women. 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/urinary-tract-infection-lower-women/ (accessed 13 March 2023)

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. 2021. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/ (accessed 13 March 2023)

O'Grady MC, Barry L, Corcoran GD, Hooton C, Sleator RD, Lucey B. Empirical treatment of urinary tract infections: how rational are our guidelines?. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019; 74:(1)214-217 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dky405

O'Neill D, Branham S, Reimer A, Fitzpatrick J. Prescriptive practice differences between nurse practitioners and physicians in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in the emergency department setting. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2021; 33:(3)194-199 https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000472

Royal Pharmaceutical Society. A competency framework for designated prescribing practitioners. 2019. https://www.rpharms.com/resources/frameworks (accessed 13 March 2023)

Singh N, Gandhi S, McArthur E Kidney function and the use of nitrofurantoin to treat urinary tract infections in older women. CMAJ. 2015; 187:(9)648-656 https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.150067

Stamatakos M, Sargedi C, Stasinou T, Kontzoglou K. Vesicovaginal fistula: diagnosis and management. Indian J Surg. 2014; 76:(2)131-136 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-012-0787-y

Swift A. Understanding the effects of pain and how human body responds. Nurs Times. 2018; 114:(3)22-26 https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/pain-management/understanding-the-effect-of-pain-and-how-the-human-body-responds-26-02-2018/

Taylor K. Non-medical prescribing in urinary tract infections in the community setting. Nurse Prescribing. 2016; 14:(11)566-569 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2016.14.11.566

Wijma RA, Huttner A, Koch BCP, Mouton JW, Muller AE. Review of the pharmacokinetic properties of nitrofurantoin and nitroxoline. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018; 73:(11)2916-2926 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dky255

Wijma RA, Curtis SJ, Cairns KA, Peleg AY, Stewardson AJ. An audit of nitrofurantoin use in three Australian hospitals. Infect Dis Health. 2020; 25:(2)124-129 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2020.01.001

Urinary tract infection in an older patient: a case study and review

Advanced Nurse Practitioner, Primary Care

View articles

Gerri Mortimore

Senior lecturer in advanced practice, department of health and social care, University of Derby

View articles · Email Gerri

This article will discuss and reflect on a case study involving the prescribing of nitrofurantoin, by a non-medical prescriber, for a suspected symptomatic uncomplicated urinary tract infection in a patient living in a care home. The focus will be around the consultation and decision-making process of prescribing and the difficulties faced when dealing with frail, uncommunicative patients. This article will explore and critique the evidence-base, local and national guidelines, and primary research around the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nitrofurantoin, a commonly prescribed medication. Consideration of the legal, ethical and professional issues when prescribing in a non-medical capacity will also be sought, concluding with a review of the continuing professional development required to influence future prescribing decisions relating to the case study.

Urinary tract infections are common in older people. Haley Read and Gerri Mortimore describe the decision making process in the case of an older patient with a UTI

One of the growing community healthcare delivery agendas is that of the advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) role to improve access to timely, appropriate assessment and treatment of patients, in an attempt to avoid unnecessary health deterioration and/or hospitalisation ( O'Neill et al, 2021 ). The Core Capabilities Framework for Advanced Clinical Practice (Nurses) Working in General Practice/Primary Care in England recognises the application of essential skills, including sound consultation and clinical decision making for prescribing appropriate treatment ( Health Education England [HEE], 2020 ). This article will discuss and reflect on a case study involving the prescribing of nitrofurantoin by a ANP for a suspected symptomatic uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI), in a patient living in a care home. Focus will be around the consultation and decision-making process of non-medical prescribing and will explore and critique the evidence-base, examining the local and national guidelines and primary research around the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nitrofurantoin. Consideration of the legal, ethical and professional issues when prescribing in a non-medical capacity will also be sought, concluding with review of the continuing professional development required to influence future prescribing decisions relating to the case study.

Mrs M, an 87-year-old lady living in a nursing home, was referred to the community ANP by the senior carer. The presenting complaint was reported as dark, cloudy, foul-smelling urine, with new confusion and night-time hallucinations. The carer reported a history of disturbed night sleep, with hallucinations of spiders crawling in bed, followed by agitation, lethargy and poor oral intake the next morning. The SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) tool was adopted, ensuring structured and relevant communication was obtained ( NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021 ). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ( NICE, 2021 ) recognises that cloudy, foul-smelling urine may indicate UTI. Other symptoms include increased frequency or pressure to pass urine, dysuria, haematuria or dark coloured urine, mild fever, night-time urination, and increased sweats or chills, with lower abdominal/loin pain suggesting severe infection. NICE (2021) highlight that patients with confusion may not report UTI symptoms. This is supported by Gupta and Gupta (2019) , who recognise new confusion as hyper-delirium, which can be attributed to several causative factors including infection, dehydration, constipation and medication, among others.

UTIs are one of the most common infections worldwide ( O'Grady et al, 2019 ). Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) define UTI as a presence of colonising bacteria that cause a multitude of symptoms affecting either the upper or lower urinary tract. NICE (2021) further classifies UTIs as either uncomplicated or complicated, with complicated involving other systemic conditions or pre-existing diseases. Geerts et al (2013) postulate around 30% of females will develop a UTI at least once in their life. The incidence increases with age, with those over 65 years of age being five times more likely to develop a UTI at any point. Further increased prevalence is found in patients who live in a care home, with up to 60% of all infections caused by UTI ( Bardsley, 2017 ).

Greener (2011) reported that symptoms of UTIs are often underestimated by clinicians. A study cited by Greener (2011) found over half of GPs did not record the UTI symptoms that the patient had reported. It is, therefore, essential during the consultation to use open-ended questions, listening to the terminology of the patient or carers to clarify the symptoms and creating an objective history ( Taylor, 2016 ).

In this case, the carer highlighted that Mrs M had been treated for suspected UTI twice in the last 12 months. Greener (2011) , in their literature review of 8 Cochrane review papers and 1 systematic review, which looked at recurrent UTI incidences in general practice, found 48% of women went on to have a further episode within 12 months.

Mrs M's past medical history reviewed via the GP electronic notes included:

- Hypertension

- Diverticular disease

- Basal cell carcinoma of scalp

- Retinal vein occlusion

- Severe frailty

- Fracture of proximal end of femur

- Total left hip replacement

- Previous indwelling urinary catheter

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 2

- Urinary and faecal incontinence

- And, most recently, vesicovaginal fistula.

Bardsley (2017) identified further UTI risk factors including postmenopausal females, frailty, co-morbidity, incontinence and use of urethral catheterisation. Vesicovaginal fistulas also predispose to recurrent UTIs, due to the increase in urinary incontinence ( Stamatokos et al, 2014 ). Moreover, UTIs are common in older females living in a care home ( Bradley and Sheeran, 2017 ). They can cause severe risks to the patient if left untreated, leading to complications such as pyelonephritis or sepsis ( Ahmed et al, 2018 ).

Mrs M's medication included:

- Paracetamol 1 g as required

- Lactulose 10 ml twice daily

- Docusate 200 mg twice daily

- Epimax cream

- Colecalciferol 400 units daily

- Alendronic acid 70 mg weekly.

She did not take any herbal or over the counter preparations. Her records reported no known drug allergies; however, she was allergic to Elastoplast. A vital part of clinical history involves reviewing current prescribed and non-prescribed medications, herbal remedies and drug allergies, to prevent contraindications or reactions with potential prescribed medication ( Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2019 ). Several authors, including Malcolm et al (2018) , indicate polypharmacy as a common cause of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), worsening health and affecting a person's quality of life. NICE (2015) only recommends review of patients who are on four or more medications on each new clinical intervention, not taking into account individual drug interactions.

Due to Mrs M's lack of capacity, her social history was obtained via the electronic record and the carer. She moved to the care home 3 years ago, following respite care after her fall and hip replacement. She had never smoked or drank alcohol. Documented family history revealed stroke, ischaemic heart disease and breast cancer. Taylor (2016) reports a good thorough clinical history can equate to 90% of the working diagnosis before examination, potentially reducing unnecessary tests and investigations. This can prove challenging when the patient has confusion. It takes a more investigative approach, gaining access to medical/nursing care notes, and using family or carers to provide further collateral history ( Gupta and Gupta, 2019 ).

As per NICE (2021) guidelines, a physical examination of Mrs M was carried out. On examination it was noted that Mrs M had mild pallor with normal capillary refill time, no signs of peripheral or central cyanosis, and no clinical stigmata to note. Her heart rate was elevated at 112 beats per minute and regular, she had a normal respiration rate of 17 breaths per minute, oxygen saturations (SpO 2 ) were 98% on room air and blood pressure was 116/70 mm/Hg. Her temperature was 37.3oC. According to Doyle and Schortgen (2016) , there is no agreed level of fever; however, it becomes significant when above 38.3oC. Bardsley (2017) adds that older patients do not always present with pyrexia in UTI because of an impaired immune response.

Heart and chest sounds were normal, with no peripheral oedema. The abdomen was non-distended, soft and non-tender on palpation, with no reports of nausea, vomiting, supra-pubic tenderness or loin pain. Loin pain or suprapubic tenderness can indicate pyelonephritis ( Bardsley, 2017 ). Tachycardia, fever, confusion, drowsiness, nausea/vomiting or tachypnoea are strong predictive signs of sepsis ( NICE, 2021 ).

During the consultation, confusion and restlessness were evident. Therefore, it was difficult to ask direct questions to Mrs M regarding pain, nausea and dizziness. Non-verbal cues were considered, as changes in behaviour and restlessness can potentially highlight discomfort or pain ( Swift, 2018 ).

Mrs M's most recent blood tests indicated CKD stage 2, based on an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 82 ml/minute/1.73m 2 . The degree of renal function is vital to establish prior to any prescribing decision, because of the potential increased risk of drug toxicity ( Doogue and Polasek, 2013 ). The agreed level of mild renal impairment is when eGFR is <60 ml/minute/1.73 m 2 , with chronic renal impairment established when eGFR levels are sustained over a 3-month period ( Ahmed et al, 2018 ).

Previous urine samples of Mrs M grew Escherichia coli bacteria, sensitive to nitrofurantoin but resistant to trimethoprim. A consensus of papers, including Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) , highlight the most common pathogen for UTI as E. coli. Fransen et al (2016) indicates that increased use of empirical antibiotics has led to a prevalence of extended spectrum beta lactamase positive (ESBL+) bacteria that are resistant to many current antibiotics. This is not taken into account by the NICE guidelines (2021) ; however, it is discussed in local guidelines ( Barnsley Hospital NHS FT/Rotherham NHS FT, 2022 ).

Mrs M was unable to provide an uncontaminated urine sample due to incontinence. NICE (2021) advocate urine culture as a definitive diagnostic tool for UTIs; however, do not highlight how to objectively obtain this. Bardsley (2017) recognises the benefit of an uncontaminated urinalysis in symptomatic patients, stating that alongside other clinical signs, nitrates and leucocytes strongly predict the possibility of UTI. O'Grady et al (2019) points out that although NICE emphasise urine culture collection, it omits the use of urinalysis as part of the assessment.

Based on Ms M's clinical history and physical examination, a working diagnosis of suspected symptomatic uncomplicated UTI was hypothesised. A decision was made, based on the local antibiotic prescribing guidelines, as well as the NICE (2021) guidelines, to treat empirically with nitrofurantoin modified release (MR), 100 mg twice daily for 3 days, to avoid further health or systemic complications. The use of electronic prescribing was adopted as per local organisational policy and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2019) . Electronic prescribing is essential for legibility and sharing of prescribing information. It also acts as an audit on prescribing practices, providing a contemporaneous history for any potential litigation ( Lovatt, 2010 ).

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) reflect on the origins of nitrofurantoin back to the 1950s, following high penicillin usage leading to resistance of Gram-negative bacteria. Nitrofurantoin has been the first-line empirical treatment for UTIs internationally since 2010, despite other antibacterial agents being discovered ( Wijma et al, 2020 ). Mckinell et al (2011) highlight that a surge in bacterial resistance brought about interest in nitrofurantoin as a first-line option. Their systematic review of the literature indicated through a cost and efficacy decision analysis that nitrofurantoin was a low resistance and low cost risk; therefore, an effective alternative to trimethoprim or fluoroquinolones. The weakness of this paper is the lack of data on nitrofurantoin cure rates and resistance studies, demonstrating an inability to predict complete superiority of nitrofurantoin over other antibiotics. This could be down to the reduced use of nitrofurantoin treatment at the time.

Fransen et al (2016) reported that minimal pharmacodynamic knowledge of nitrofurantoin exists, despite its strong evidence-based results against most common urinary pathogens, and being around for the last 70 years. Wijma et al (2018) hypothesised this was because of the lack of drug approval requirements in the era when nitrofurantoin was first produced, and the growing incidence of antibiotic resistance. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are clinically important to guide effective drug therapy and avoid potential ADRs. Focus on the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of nitrofurantoin is needed to evaluate the correct choice for an individual patient, based on a holistic assessment ( Doogue and Polasek, 2013 ).

Nitrofurantoin is structurally made up of 4 carbon and 1 oxygen atoms forming a furan ring, connected to a nitrogroup (–NO 2 ). Its mode of action is predominantly bacteriostatic, with some bactericidal tendencies in high concentration levels ( Wijma et al, 2018 ). It works by inhibiting bacterial cell growth, breaking down its strands of DNA ( Komp Lindgren et al, 2015 ). Hoang and Salbu (2016) add that nitrofurantoin causes bacterial flavoproteins to create reactive medians that halt bacterial ribosomal proteins, rendering DNA/RNA cell wall synthesis inactive.

Nitrofurantoin is administered orally via capsules or liquid. Greener (2011) highlights the different formulations, which originally included microcrystalline tablets and now include macro-crystalline capsules. The increased size of crystals was found to slow absorption rates down ( Hoang and Salbu, 2016 ). Nitrofurantoin is predominantly absorbed via the gastro-intestinal tract, enhanced by an acidic environment. It is advised to take nitrofurantoin with food, to slow down gastric emptying ( Wijma et al, 2018 ). The maximum blood concentration of nitrofurantoin is said to be <0.6 mg/l. Lower plasma concentration equates to lower toxicity risk; therefore, nitrofurantoin is favourable over fluoroquinolones ( Komp Lindgren et al, 2015 ). Wijma et al (2020) found a reduced effect on gut flora compared to fluoroquinolones.

Distribution of nitrofurantoin is mainly via the renal medulla, with a renal bioavailability of 38.8–44%; therefore, it is specific for urinary action ( Hoang and Salbu, 2016 ). Haasum et al (2013) highlight the inability for nitrofurantoin to penetrate the prostate where bacteria concentration levels can be present. Therefore, they do not advocate the use of nitrofurantoin to treat males with UTIs, because of the risk of treatment failure and further complications of systemic infection. This did not appear to be addressed by local guidelines.

The metabolism of nitrofurantoin is not completely understood; however, Wijma et al (2018) indicate several potential metabolic antibacterial actions. Around 0.8–1.8% is metabolised into aminofurantoin, with 80.9% other unknown metabolites ( medicines.org, 2022 ). Wijma et al (2020) calls for further study into the metabolism of nitrofurantoin to aid understanding of the pharmacodynamics.

Excretion of nitrofurantoin is predominantly via urine, with a peak time of 4–5 hours, and 27–50% excreted unchanged in urine ( medicines.org, 2022 ). Komp Lindgren et al (2015) equates the fast rates of renal availability and excretion to lower toxicity risks and targeted treatment for UTI pathogens. Wijma et al (2018) found high plasma concentration levels of nitrofurantoin in renal impairment. Singh et al (2015) indicate that nitrofurantoin is mainly eliminated via glomerular filtration; therefore, its impairment presents the potential risks of treatment failure and increased ADRs. Early guidelines stipulated the need to avoid nitrofurantoin in patients with mild renal impairment, indicating the need for an eGFR of >60 ml/min due to this toxicity risk. This was based on several small studies, cited by Hoang and Salbu (2016) , looking at concentration levels rather than focused on patient treatment outcomes.

Primary research by Geerts et al (2013) involving treatment outcomes in a large cohort study, led to guidelines changing the limit to mild to moderate impairment or eGFR >45 ml/min. However, the risk of ADRs, including pulmonary fibrosis and hepatic changes, were increased in renal insufficiency with prolonged use. The study participants had a mean age of 47.8 years; therefore, the study did not indicate the effects on older patients. Singh et al (2015) presented a Canadian study, looking at treatment success with nitrofurantoin in older females, with a mean age of 79 years. It indicated effective treatment despite mild/moderate renal impairment. It did not address the levels of ADRs or hospitalisation. Ahmed et al (2018) conducted a large, UK-based, retrospective cohort study favouring use of empirical nitrofurantoin in the older population with increased risk of UTI-related hospitalisation and mild/moderate renal impairment. It concluded not treating could increase mortality and morbidity. This led to guidelines to support empirical treatment of symptomatic older patients with nitrofurantoin.

Dosing is highly variable between the local and national guidelines. Greener (2011) highlights that product information for the macro-crystalline capsules recommends 50–100 mg 4 times a day for 7 days when treating acute uncomplicated UTI. Local guidelines from Barnsley Hospital NHS FT/Rotherham NHS FT Adult antimicrobial guide (2022) stipulate 50–100 mg 4 times daily for 3 days for women, whereas NICE (2021) recommends a MR version of 100 mg twice daily for 3 days.

In a systematic literature review on the pharmacokinetics of nitrofurantoin, Wijma et al (2018) found that use of a 5–7 day course had similar strong efficacy rates, whereas 3 days did not, potentially causing treatment failure, equating to poor patient outcomes and resistant behaviour. Deresinski (2018) conducted a small, randomised controlled trial involving 377 patients either on nitrofurantoin MR 100 mg three times a day for 5 days or fosfomycin single dose treatment after urinalysis and culture. It looked at response to treatment after 28 days. Nitrofurantoin was found to have a 78% cure rate compared to 50% with fosfomycin. Therefore, these studies directly contradict current NICE and local guidelines on treatment dosing of UTI in women. More robust studies on dosing regimens are therefore required.

Fransen et al (2016) conducted a non-human pharmacodynamics study looking at time of action to treat on 11 strains of common UTI bacteria including two ESBL+. It demonstrated the kill rate for E. coli was 16–24 hours, slower than Enterobacter cloacae (6–8 hours) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (8 hours). The findings also indicated that nitrofurantoin appeared effective against ESBL+. Dosing and urine concentrations were measured, and found that 100 mg every 6 hours kept the urine concentration levels significant enough to reach peak levels. This study directly contradicted the findings of Lindgren et al (2015) , who conducted similar non-human kinetic style kill rate studies, and found nitrofurantoin's dynamic action to be within 6 hours for E. coli. Both studies have limitations in that they did not take into account human immune response effects.

Wijma et al (2020) highlighted inconsistent dosing regimens in their retrospective audit involving 150 patients treated for UTIs across three Australian secondary care facilities. The predominant dosing of nitrofurantoin was 100 mg twice daily for 5 days for women and 7 days for males. Although a small audit-based paper, it creates debate regarding the lack of clarity around the correct dosing, leaving it open to error. It therefore requires primary research into the follow up of cure rates on guideline prescribing regimens. Dose and timing remains an important issue to reduce treatment failure. It indicates the need for bacteria-dependant dosing, which currently NICE (2021) does not discuss.

Haasum et al (2013) found poor adherence to guidelines for choice and dosing in elderly patients in their Swedish register-based large population study. It highlighted high use of trimethoprim in frail older care home residents, despite guidelines recommending nitrofurantoin as first-line. A recent retrospective, observational, quantitative study by Langner et al (2021) involving 44.9 million women treated for a UTI in the USA across primary and secondary care, found an overuse of fluoroquinolones and underuse of nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim, especially by primary care physicians for older Asian and socio-economically deprived patients. Both these studies did not seek a true qualitative rationale for choices of antibiotics; therefore, limiting the findings.

Legal and ethical considerations

NMP regulation of best practice is set by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society framework (2019) , incorporating several acts of law including the medicines act 1968, and medicinal products prescribed by the Nurses Act (1992). As per Nursing Midwifery Council (2021) Code of Conduct and Health Education England (2020), ANPs have a duty of care to patients, ensuring that they work within their area of competence and recognise any limitations, demonstrating accountability for decisions made ( Lovatt, 2010 ).

Empirical treatment of UTIs is debated in the literature. O'Grady et al (2019) summarises that empirical treatment can reduce further UTI complications that can lead to acute health needs and hospitalisation, without increased risk of antibiotic resistance. Greener (2011) states that uncomplicated UTIs can be self-limiting; therefore, not always warranting antibiotic treatment if sound self-care advice is adopted. Chardavoyne and Kasmire (2020) discuss delayed prescribing, involving putting the onus on the patient and carers, which was not advisable in the case of Mrs M. Bradley and Sheeran (2017) found that three quarters of antibiotics in care home residents were prescribed inaccurately, hence recommended a watch and wait approach to treatment in the older care home resident, following implementation of a risk reduction strategy.

Taylor (2016) recommended an individual, holistic approach, incorporating ethical considerations such as choice, level of concordance, understanding and agreement of treatment choice. This can prove difficult in a case such as Mrs M. If a patient is deemed to lack capacity, a decision to act in the patient's best interest should be applied ( Gupta and Gupta, 2019 ). Therefore, understanding a patient's beliefs and values via family or carers should be explored, balancing the needs and possible outcomes. The principle of non-maleficence should be adopted, looking at risks versus benefits on prescribing the antibiotic to the individual patient ( Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2019 ).

Non-pharmacological advice was provided to the carers to ensure that Mrs M maintained good fluid intake of 2 litres in 24 hours. NICE (2021) advocates the use of written self-care advice leaflets that have been produced to educate patients and/or carers on non-pharmacological actions, supporting recovery and improving outcomes. The use of paracetamol for symptoms of fever and/or pain was also recommended for Mrs M. Prevention strategies proposed by Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) included looking at the benefits of oestrogen cream in post-menopausal women in reducing the incidence of UTIs. Cranberry juice, probiotics and vitamin C ingestion are not supported by any strong evidence base.

There is a duty of care to ensure that follow up of the patient during and after treatment is delivered by the NMP ( Chardavoyne and Kasmire, 2020 ). Clinical safety netting advice was discussed with the carers to monitor Mrs M for any deterioration, and to seek further clinical review urgently. Particular attention to signs of ADRs and sepsis, and the need for 999 response if these occurred, was advocated. A treatment plan was also sent to the GP to ensure sound communication and continuation of safe care ( Taylor, 2016 ).

Professional development issues

The extended role of prescribing brings additional responsibility, with onus on both the NMP and the employer vicariously, to ensure key skills are updated. This is where continued professional development involving research, training and knowledge is sought and applied, using evidence-based, up-to-date practice ( HEE, 2020 ). Adoption of antibiotic stewardship is highlighted by several papers including Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) . They advise nine points to consider, to increase knowledge around the actions and consequences of the drug by the prescriber. Despite no acknowledgment in NICE (2021) guidance, previous results of infections and sensitivities are also proposed as vital in antibiotic stewardship.

The use of decision support tools, proposed by Malcolm et al (2018) , involves an audit approach looking at antibiograms, that highlight local microbiology resistance patterns to aid antibiotic choices, alongside a risk reduction team strategy. Bradley and Sheeran (2017) looked at improving antibiotic use for UTI treatment in a care home in Pennsylvania. They employed a programme of monitoring and educating clinical staff, patients, carers and relatives in evidence-based self-care and clinical assessment skills over a 30-month period. It demonstrated a reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, and an improvement in monitoring symptoms and self-care practices, creating better patient outcomes. It was evaluated highly by nursing staff, who reported a sense of autonomy and confidence involving team work. Langner et al (2021) calls for further education and feedback to prescribers, involving pharmacists and microbiology data to identify and understand patterns of prescribing.

UTIs can be misdiagnosed and under- or over-treated, despite the presence of local and national guidelines. Continued monitoring of nitrofurantoin use requires priority, due to its first-line treatment status internationally, as this may increase reliance and overuse of the drug, with potential for resistant strains of bacteria becoming prevalent.

Diligent clinical assessment skills and prescribing of appropriate treatment is paramount to ensure risk of serious complications, hospitalisation and mortality are reduced, while quality of life is maintained. The use of competent clinical practice, up-to-date evidence-based knowledge, good communication and understanding of individual patient needs, and concordance are essential to make sound prescribing choices to avoid harm. As well as the prescribing of medications, the education, monitoring and follow-up of the patient and prescribing practices are equally a vital part of the autonomous role of the NMP.

KEY POINTS:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) can be misdiagnosed and under- or over-treated, despite the presence of local and national guidelines

- The incidence of UTI increases with age, with those over 65 years of age being five times more likely to develop a UTI at any point

- Nitrofurantoin has been the first-line empirical treatment for UTIs internationally since 2010. Its mode of action is predominantly bacteriostatic, with some bactericidal tendencies in high concentration levels

- Diligent clinical assessment skills and prescribing of appropriate treatment is paramount to ensure risk of serious complications, hospitalisation and mortality are reduced, while quality of life is maintained

CPD REFLECTIVE PRACTICE:

- How can a good clinical history be gained if the patient lacks capacity?

- What factors need to be considered when safety netting in cases like this?

- What non-pharmacological advice would you give to a patient with a urinary tract infection (or their carers)?

- How will this article change your clinical practice?

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

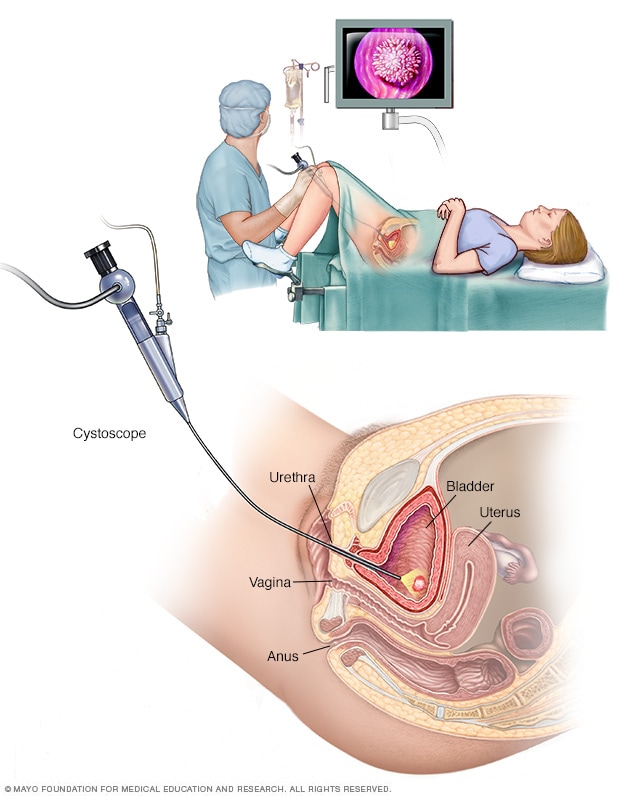

Female cystoscopy

Cystoscopy allows a health care provider to view the lower urinary tract to look for problems, such as a bladder stone. Surgical tools can be passed through the cystoscope to treat certain urinary tract conditions.

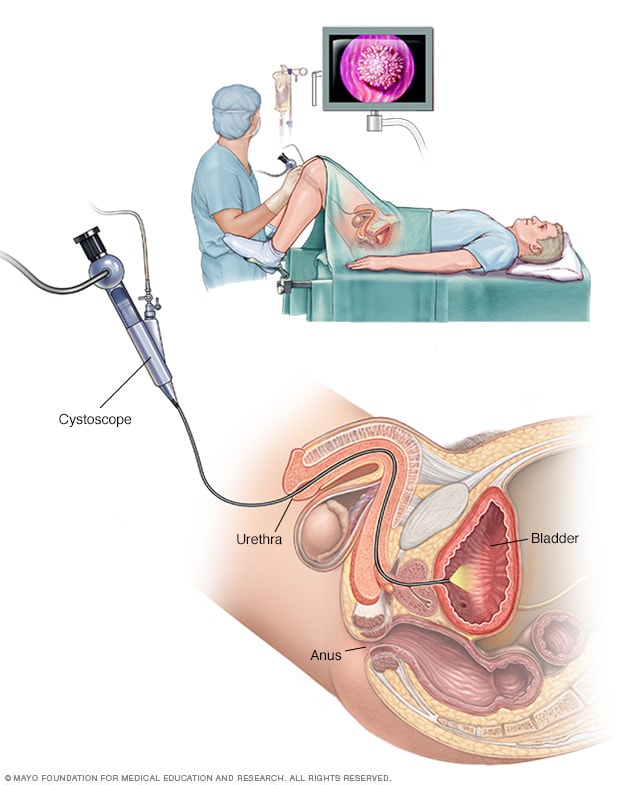

Male cystoscopy

Cystoscopy allows a health care provider to view the lower urinary tract to look for problems in the urethra and bladder. Surgical tools can be passed through the cystoscope to treat certain urinary tract conditions.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose urinary tract infections include:

- Analyzing a urine sample. Your health care provider may ask for a urine sample. The urine will be looked at in a lab to check for white blood cells, red blood cells or bacteria. You may be told to first wipe your genital area with an antiseptic pad and to collect the urine midstream. The process helps prevent the sample from being contaminated.

- Growing urinary tract bacteria in a lab. Lab analysis of the urine is sometimes followed by a urine culture. This test tells your provider what bacteria are causing the infection. It can let your provider know which medications will be most effective.

- Creating images of the urinary tract. Recurrent UTI s may be caused by a structural problem in the urinary tract. Your health care provider may order an ultrasound, a CT scan or MRI to look for this issue. A contrast dye may be used to highlight structures in your urinary tract.

- Using a scope to see inside the bladder. If you have recurrent UTI s, your health care provider may perform a cystoscopy. The test involves using a long, thin tube with a lens, called a cystoscope, to see inside the urethra and bladder. The cystoscope is inserted in the urethra and passed through to the bladder.

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Our caring team of Mayo Clinic experts can help you with your Urinary tract infection (UTI)-related health concerns Start Here

Antibiotics usually are the first treatment for urinary tract infections. Your health and the type of bacteria found in your urine determine which medicine is used and how long you need to take it.

Simple infection

Medicines commonly used for simple UTI s include:

- Trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Bactrim DS)

- Fosfomycin (Monurol)

- Nitrofurantoin (Macrodantin, Macrobid, Furadantin)

- Ceftriaxone

The group of antibiotics known as fluoroquinolones isn't commonly recommended for simple UTI s. These drugs include ciprofloxacin (Cipro), levofloxacin and others. The risks of these drugs generally outweigh the benefits for treating uncomplicated UTI s.

In cases of a complicated UTI or kidney infection, your health care provider might prescribe a fluoroquinolone medicine if there are no other treatment options.

Often, UTI symptoms clear up within a few days of starting treatment. But you may need to continue antibiotics for a week or more. Take all of the medicine as prescribed.

For an uncomplicated UTI that occurs when you're otherwise healthy, your health care provider may recommend a shorter course of treatment. That may mean taking an antibiotic for 1 to 3 days. Whether a short course of treatment is enough to treat your infection depends on your symptoms and medical history.

Your health care provider also may give you a pain reliever to take that can ease burning while urinating. But pain usually goes away soon after starting an antibiotic.

Frequent infections

If you have frequent UTI s, your health care provider may recommend:

- Low-dose antibiotics. You might take them for six months or longer.

- Diagnosing and treating yourself when symptoms occur. You'll also be asked to stay in touch with your provider.

- Taking a single dose of antibiotic after sex if UTI s are related to sexual activity.

- Vaginal estrogen therapy if you've reached menopause.

Severe infection

For a severe UTI , you may need IV antibiotics in a hospital.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Urinary tract infections can be painful, but you can take steps to ease discomfort until antibiotics treat the infection. Follow these tips:

- Drink plenty of water. Water helps to dilute your urine and flush out bacteria.

- Avoid drinks that may irritate your bladder. Avoid coffee, alcohol, and soft drinks containing citrus juices or caffeine until the infection has cleared. They can irritate your bladder and tend to increase the need to urinate.

- Use a heating pad. Apply a warm, but not hot, heating pad to your belly to help with bladder pressure or discomfort.

Alternative medicine

Many people drink cranberry juice to prevent UTI s. There's some indication that cranberry products, in either juice or tablet form, may have properties that fight an infection. Researchers continue to study the ability of cranberry juice to prevent UTI s, but results aren't final.

There's little harm in drinking cranberry juice if you feel it helps you prevent UTI s, but watch the calories. For most people, drinking cranberry juice is safe. However, some people report an upset stomach or diarrhea.

But don't drink cranberry juice if you're taking blood-thinning medication, such as warfarin (Jantovin).

Preparing for your appointment

Your primary care provider, nurse practitioner or other health care provider can treat most UTI s. If you have frequent UTI s or a chronic kidney infection, you may be referred to a health care provider who specializes in urinary disorders. This type of doctor is called a urologist. Or you may see a health care provider who specializes in kidney disorders. This type of doctor is called a nephrologist.

What you can do

To get ready for your appointment:

- Ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as collect a urine sample.

- Take note of your symptoms, even if you're not sure they're related to a UTI .

- Make a list of all the medicines, vitamins or other supplements that you take.

- Write down questions to ask your health care provider.

For a UTI , basic questions to ask your provider include:

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- Are there any other possible causes?

- Do I need any tests to confirm the diagnosis?

- What factors do you think may have contributed to my UTI ?

- What treatment approach do you recommend?

- If the first treatment doesn't work, what will you recommend next?

- Am I at risk of complications from this condition?

- What is the risk that this problem will come back?

- What steps can I take to lower the risk of the infection coming back?

- Should I see a specialist?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions as they occur to you during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider will likely ask you several questions, including:

- When did you first notice your symptoms?

- Have you ever been treated for a bladder or kidney infection?

- How severe is your discomfort?

- How often do you urinate?

- Are your symptoms relieved by urinating?

- Do you have low back pain?

- Have you had a fever?

- Have you noticed vaginal discharge or blood in your urine?

- Are you sexually active?

- Do you use contraception? What kind?

- Could you be pregnant?

- Are you being treated for any other medical conditions?

- Have you ever used a catheter?

Urinary tract infection (UTI) care at Mayo Clinic

- Partin AW, et al., eds. Infections of the urinary tract. In: Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Ferri FF. Urinary tract infection. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2022. Elsevier; 2022. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Bladder infection (urinary tract infection) in adults. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/bladder-infection-uti-in-adults. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/urinary-tract-infections. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Cai T. Recurrent uncomplicated urinary tract infections: Definitions and risk factors. GMS Infectious Diseases. 2021; doi:10.3205/id000072.

- Hooton TM, et al. Acute simple cystitis in women. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- Pasternack MS. Approach to the adult with recurrent infections. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- Cranberry. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/cranberry. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Goebel MC, et al. The five Ds of outpatient antibiotic stewardship for urinary tract infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2021; doi:10.1128/CMR.00003-20.

- Overactive bladder (OAB): Lifestyle changes. Urology Care Foundation. https://urologyhealth.org/urologic-conditions/overactive-bladder-(oab)/treatment/lifestyle-changes. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Nguyen H. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. May 5, 2022.

- AskMayoExpert. Urinary tract infection (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2022.

News from Mayo Clinic

- UTI: This common infection can be serious Jan. 12, 2024, 04:24 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q and A: 6 UTI myths and facts Feb. 02, 2023, 01:42 p.m. CDT

- 5 tips to prevent a urinary tract infection July 12, 2022, 04:41 p.m. CDT

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies

- A Book: Taking Care of You

- Assortment of Health Products from Mayo Clinic Store

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

VICTORIA J. SHARP, MD, DANIEL K. LEE, MD, AND ERIC J. ASKELAND, MD

A more recent article on office-based urinalysis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(8):542-547

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Urinalysis is useful in diagnosing systemic and genitourinary conditions. In patients with suspected microscopic hematuria, urine dipstick testing may suggest the presence of blood, but results should be confirmed with a microscopic examination. In the absence of obvious causes, the evaluation of microscopic hematuria should include renal function testing, urinary tract imaging, and cystoscopy. In a patient with a ureteral stent, urinalysis alone cannot establish the diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Plain radiography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder can identify a stent and is preferred over computed tomography. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the isolation of bacteria in an appropriately collected urine specimen obtained from a person without symptoms of a urinary tract infection. Treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is not recommended in nonpregnant adults, including those with prolonged urinary catheter use.

Urinalysis with microscopy has proven to be an invaluable tool for the clinician. Urine dipstick testing and microscopy are useful for the diagnosis of several genitourinary and systemic conditions. 1 , 2 In 2005, a comprehensive review of urinalysis was published in this journal. 3 This article presents a series of case scenarios that illustrate how primary care physicians can utilize the urinalysis in common clinical situations.

Microscopic Hematuria: Case 1

Microscopic hematuria is common and has a broad differential diagnosis, ranging from completely benign causes to potentially invasive malignancy. Causes of hematuria can be classified as glomerular, renal, or urologic 3 – 5 ( Table 1 6 ) . The prevalence of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria varies among populations from 0.18% to 16.1%. 4 The American Urological Association (AUA) defines asymptomatic microscopic hematuria as three or more red blood cells per high-power field in a properly collected specimen in the absence of obvious causes such as infection, menstruation, vigorous exercise, medical renal disease, viral illness, trauma, or a recent urologic procedure. 5 Microscopic confirmation of a positive dipstick test for microscopic hematuria is required. 5 , 7

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

Case 1: microscopic hematuria.

A 58-year-old truck driver with a 30-year history of smoking one pack of cigarettes per day presents for a physical examination. He reports increased frequency of urination and nocturia, but does not have gross hematuria. Physical examination reveals an enlarged prostate. Results of his urinalysis with microscopy are shown in Table 2 .

Based on this patient's history, symptoms, and urinalysis findings, which one of the following is the most appropriate next step?

A. Repeat urinalysis in six months.

B. Obtain blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels, perform computed tomographic urography, and refer for cystoscopy.

C. Treat with an antibiotic and repeat the urinalysis with microscopy.

D. Inform him that his enlarged prostate is causing microscopic hematuria, and that he can follow up as needed.

E. Perform urine cytology to evaluate for bladder cancer.

The correct answer is B .

For the patient in case 1 , because of his age, clinical history, and lack of other clear causes, the most appropriate course of action is to obtain blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels, perform computed tomographic urography, and refer the patient for cystoscopy. 5 An algorithm for diagnosis, evaluation, and follow-up of patients with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria is presented in Figure 1 . 5 The AUA does not recommend repeating urinalysis with microscopy before the workup, especially in patients who smoke, because tobacco use is a risk factor for urothelial cancer ( Table 3 ) . 5

A previous article in American Family Physician reviewed the American College of Radiology's Appropriateness Criteria for radiologic evaluation of microscopic hematuria. 8 Computed tomographic urography is the preferred imaging modality for the evaluation of patients with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. 5 , 8 It has three phases that can detect various causes of hematuria. The non–contrast-enhanced phase is optimal for detecting stones in the urinary tract; the nephrographic phase is useful for detecting renal masses, such as renal cell carcinoma; and the delayed phase outlines the collecting system of the urinary tract and can help detect urothelial malignancies of the upper urinary tract. 9 Although the delayed phase can detect some bladder masses, it should not replace cystoscopy in the evaluation for bladder malignancy. 9 After a negative microscopic hematuria workup, the patient should continue to be followed with yearly urinalysis until at least two consecutive normal results are obtained. 5

In patients with microscopic hematuria, repeating urinalysis in six months or treating empirically with antibiotics could delay treatment of potentially curable diseases. It is unwise to assume that benign prostatic hyperplasia is the explanation for hematuria, particularly because patients with this condition typically have risk factors for malignancy. Although urine cytology is typically part of the urologic workup, it should be performed at the time of cystoscopy; the AUA does not recommend urine cytology as the initial test. 5

Dysuria and Flank Pain After Lithotripsy: Case 2

After ureteroscopy with lithotripsy, a ureteral stent is often placed to maintain adequate urinary drainage. 10 The stent has one coil that lies in the bladder and another that lies in the renal pelvis. Patients with ureteral stents may experience urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria, flank pain, and hematuria. 10 They may have dull flank pain that becomes sharp with voiding. This phenomenon occurs because the ureteral stent bypasses the normal nonrefluxing uretero-vesical junction, resulting in transmission of pressure to the renal pelvis with voiding. Approximately 80% of patients with a ureteral stent experience stent-related pain that affects their daily activities. 11

POTENTIALLY MISLEADING URINALYSIS

Case 2: dysuria and flank pain after lithotripsy.

A 33-year-old woman with a history of nephrolithiasis presents with a four-week history of urinary frequency, urgency, urge incontinence, and dysuria. She recently had ureteroscopy with lithotripsy of a 9-mm obstructing left ureteral stone; she does not know if a ureteral stent was placed. She has constant dull left flank pain that becomes sharp with voiding. Results of her urinalysis with microscopy are shown in Table 4 .

A. Treat with three days of ciprofloxacin (Cipro), and tailor further antibiotic therapy according to culture results.

B. Treat with 14 days of ciprofloxacin, and tailor further antibiotic therapy according to culture results.

C. Obtain a urine culture and perform plain radiography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder.

D. Perform a 24-hour urine collection for a metabolic stone workup.

E. Perform computed tomography.

The correct answer is C .

The presence of a ureteral stent causes mucosal irritation and inflammation; thus, findings of leukocyte esterase with white and red blood cells are not diagnostic for urinary tract infection, and a urine culture is required. In this setting, plain radiography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder would be useful to determine the presence of a stent. If a primary care physician identifies a neglected ureteral stent, prompt urologic referral is indicated for removal. Retained ureteral stents may become encrusted, and resultant stone formation may lead to obstruction. 10