Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Six Online Activities to Help Students Cope With COVID-19

At the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, UNESCO estimates that 91.3% of the world’s students were learning remotely, with 194 governments ordering country-wide closures of their schools and more than 1.3 billion students learning in online classrooms.

Now that the building blocks of remote education have been put into place and classroom learning is underway, more and more teachers are turning their attention to the mental health of their students. Youth anxiety about the coronavirus is rising , and our young people are feeling isolated, disconnected, and confused. While social-emotional education has typically taken place in the bricks and mortar of schools, we must now adapt these curriculums for an online setting.

I have created six well-being activities for teachers to deliver online using the research-based SEARCH framework , which stands for Strengths, Emotional management, Attention and awareness, Relationships, Coping, and Habits and goals. Research suggests that students who cultivate these skills have stronger coping capacity , are more adaptable and receptive to change , and are more satisfied with their lives .

The virtual activities can be used for specific well-being lessons or advisory classes , or can be woven into other curricula you are teaching, such as English, Art, Humanities, and Physical Education. You might consider using the activities in three ways:

- Positive primer: to energize your students at the start of class to kickstart learning, prompt them to think about their well-being in that moment, get them socially connected online, and get their brain focused for learning.

- Positive pause: to re-energize students at a time when you see class dynamics shifting, energy levels dropping, or students being distracted away from the screen.

- Positive post-script: to reward students and finish off the class in a positive way before they log off.

Rather than viewing these activities as another thing you have to fit in, use them as a learning tool that helps your students stay focused, connected, and energized.

1. Strengths

Activity: Staying Strong During COVID-19 Learning goal: To help students learn about their own strengths Time: 50 minutes Age: 10+

Prior to the lesson, have students complete the VIA strengths questionnaire to identify their strengths.

Step 1: In the virtual class, explain the VIA strengths framework to students. The VIA framework is a research-based model that outlines 24 universal character strengths (such as kindness, courage, humor, love of learning, and perseverance) that are reflected in a student’s pattern of thoughts, feelings, and actions. You can learn more about the framework and find a description of each character strength from the VIA Institute on Character .

Step 2: Place students in groups of four into chat rooms on your online learning platform and ask them to discuss these reflection questions:

- What are your top five strengths?

- How can you use your strengths to stay engaged during remote learning?

- How can you use your strengths during home lockdown or family quarantine?

- How do you use your strengths to help your friends during COVID-19?

Step 3: As a whole class, discuss the range of different strengths that can be used to help during COVID times.

Research shows that using a strength-based approach at school can improve student engagement and grades , as well as create more positive social dynamics among students. Strengths also help people to overcome adversity .

2. Emotional management

Activity: Managing Emotions During the Coronavirus Pandemic Learning goal: To normalize negative emotions and to generate ways to promote more positive emotions Time: 50 minutes Age: 8+

Step 1: Show students an “emotion wheel” and lead a discussion with them about the emotions they might be feeling as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. You can use this wheel for elementary school and this wheel for high school.

Step 2: Create an anonymous online poll (with a service like SurveyMonkey ) listing the following 10 emotions: stressed, curious, frustrated, happy, angry, playful, sad, calm, helpless, hopeful.

Step 3: In the survey, ask students to enter the five emotions they are feeling most frequently.

Step 4: Tally the results and show them on your screen for each of the 10 emotions. Discuss the survey results. What emotions are students most often feeling? Talk about the range of emotions experienced. For example, some people will feel sad when others might feel curious; students can feel frustrated but hopeful at the same time.

Step 5: Select the top two positive emotions and the top two negative emotions from the survey. Put students into groups of four in virtual breakout rooms to brainstorm three things they can do to cope with their negative emotions, and three action steps they can take to have more positive emotions.

Supporting Learning and Well-Being During the Coronavirus Crisis

Activities, articles, videos, and other resources to address student and adult anxiety and cultivate connection

Research shows that emotional management activities help to boost self-esteem and reduce distress in students. Additionally, students with higher emotional intelligence also have higher academic performance .

3. Attention and awareness

Activity: Finding Calm During Coronavirus Times Learning goal: To use a mindful breathing practice to calm our heart and clear our mind Time: 10 minutes Age: All

Step 1: Have students rate their levels of stress on a scale of 1-10, with 1 being very calm and 10 being highly stressed.

Step 2: Do three minutes of square breathing, which goes like this:

- Image a square in front of you at chest height.

- Point your index finger away from you and use it to trace the four sides of the imaginary square.

- As you trace the first side of the square, breathe in for four seconds.

- As you trace the next side of the square, breathe out for four seconds.

- Continue this process to complete the next two sides of the square.

- Repeat the drawing of the square four times.

Step 3: Have students rate their levels of stress on a scale of 1-10, with 1 being very calm and 10 being highly stressed. Discuss if this short breathing activity made a difference to their stress.

Step 4: Debrief on how sometimes we can’t control the big events in life, but we can use small strategies like square breathing to calm us down.

Students who have learned mindfulness skills at school report that it helps to reduce their stress and anxiety .

4. Relationships

Activity: Color conversations Purpose: To get to know each other; to deepen class relationships during remote learning Time: 20 minutes Age: 10+

Step 1: Randomly assign students to one of the following four colors: red, orange, yellow, and purple.

Step 2: Put students into a chat room based on their color group and provide the following instructions to each group:

- Red group: Share a happy memory.

- Orange group: Share something new that you have learned recently.

- Yellow group: Share something unique about you.

- Purple group: Share what your favorite food is and why.

Step 3: Come back to the main screen and ask three students to share something new they learned about a fellow student as a result of this fun activity.

Three Good Things for Students

Help students tune in to the positive events in their lives

This is an exercise you can use repeatedly, as long as you ensure that students get mixed up into different groups each time. You can also create new prompts to go with the colors (for example, dream holiday destination, favorite ice cream flavor, best compliment you ever received).

By building up student connections, you are supporting their well-being, as research suggests that a student’s sense of belonging impacts both their grades and their self-esteem .

Activity: Real-Time Resilience During Coronavirus Times Learning goal: To identify opportunities for resilience and promote positive action Time: 30 minutes Age: 10+

Step 1: Have students brainstorm a list of all the changes that have occurred as a result of the coronavirus. As the students are brainstorming, type up their list of responses on your screen.

Step 2: Go through each thing that has changed, and have the students decide if it is something that is within their control (like their study habits at home) or something they cannot control (like not attending school on campus).

Step 3: Choose two things that the students have identified as within their control, and ask students to brainstorm a list of ways to cope with those changes.

You can repeat this exercise multiple times to go through the other points on the list that are within the students’ control.

Developing coping skills during childhood and adolescence has been show to boost students’ hope and stress management skills —both of which are needed at this time.

6. Habits and goals

Activity: Hope Hearts for the Coronavirus Pandemic Learning goal: To help students see the role that hope plays in setting goals during hard times Time: 50 minutes Age: 10+

Step 1: Find a heart image for students to use (with a program like Canva ).

Step 2: Set up an online whiteboard to post the hearts on (with a program like Miro ).

Step 3: Ask students to reflect on what hope means to them.

Step 4: Ask students to write statements on their hearts about what they hope for the world during coronavirus times, and then stick these on the whiteboard. Discuss common themes with the class. Finally, discuss one small action each student can take to create hope for others during this distressing time.

Step 5: Ask students to write statements on their hearts about what they hope for themselves, and then stick these on the whiteboard. Discuss common themes with the class. Finally, discuss one small action each student can take to work toward the goal they’re hoping for.

Helping students to set goals and have hope at this time can support their well-being. Research suggests that goals help to combat student boredom and anxiety , while having hope builds self-worth and life satisfaction .

The six activities above have been designed to help you stay connected with your students during this time of uncertainty—connected beyond the academic content that you are teaching. The intense change we are all facing has triggered heightened levels of stress and anxiety for students and teachers alike. Weaving well-being into online classrooms gives us the opportunity to provide a place of calm and show students they can use adversity to build up their emotional toolkit. In this way, you are giving them a skill set that has the potential to endure beyond the pandemic and lessons that may stay with them for many years to come.

About the Author

Lea Waters , A.M., Ph.D. , is an academic researcher, psychologist, author, and speaker who specializes in positive education, parenting, and organizations. Professor Waters is the author of the Visible Wellbeing elearning program that is being used by schools across the globe to foster social and emotional elearning. Professor Waters is the founding director and inaugural Gerry Higgins Chair in Positive Psychology at the Centre for Positive Psychology , University of Melbourne, where she has held an academic position for 24 years. Her acclaimed book The Strength Switch: How The New Science of Strength-Based Parenting Can Help Your Child and Your Teen to Flourish was listed as a top read by the Greater Good Science Center in 2017.

You May Also Enjoy

How Teachers Can Navigate Difficult Emotions During School Closures

How to Reduce the Stress of Homeschooling on Everyone

How to Help Students with Learning Disabilities Focus on Their Strengths

Can the Lockdown Push Schools in a Positive Direction?

How to Support Teachers’ Emotional Needs Right Now

How to Teach Online So All Students Feel Like They Belong

- Our Mission

Covid-19’s Impact on Students’ Academic and Mental Well-Being

The pandemic has revealed—and exacerbated—inequities that hold many students back. Here’s how teachers can help.

The pandemic has shone a spotlight on inequality in America: School closures and social isolation have affected all students, but particularly those living in poverty. Adding to the damage to their learning, a mental health crisis is emerging as many students have lost access to services that were offered by schools.

No matter what form school takes when the new year begins—whether students and teachers are back in the school building together or still at home—teachers will face a pressing issue: How can they help students recover and stay on track throughout the year even as their lives are likely to continue to be disrupted by the pandemic?

New research provides insights about the scope of the problem—as well as potential solutions.

The Achievement Gap Is Likely to Widen

A new study suggests that the coronavirus will undo months of academic gains, leaving many students behind. The study authors project that students will start the new school year with an average of 66 percent of the learning gains in reading and 44 percent of the learning gains in math, relative to the gains for a typical school year. But the situation is worse on the reading front, as the researchers also predict that the top third of students will make gains, possibly because they’re likely to continue reading with their families while schools are closed, thus widening the achievement gap.

To make matters worse, “few school systems provide plans to support students who need accommodations or other special populations,” the researchers point out in the study, potentially impacting students with special needs and English language learners.

Of course, the idea that over the summer students forget some of what they learned in school isn’t new. But there’s a big difference between summer learning loss and pandemic-related learning loss: During the summer, formal schooling stops, and learning loss happens at roughly the same rate for all students, the researchers point out. But instruction has been uneven during the pandemic, as some students have been able to participate fully in online learning while others have faced obstacles—such as lack of internet access—that have hindered their progress.

In the study, researchers analyzed a national sample of 5 million students in grades 3–8 who took the MAP Growth test, a tool schools use to assess students’ reading and math growth throughout the school year. The researchers compared typical growth in a standard-length school year to projections based on students being out of school from mid-March on. To make those projections, they looked at research on the summer slide, weather- and disaster-related closures (such as New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina), and absenteeism.

The researchers predict that, on average, students will experience substantial drops in reading and math, losing roughly three months’ worth of gains in reading and five months’ worth of gains in math. For Megan Kuhfeld, the lead author of the study, the biggest takeaway isn’t that learning loss will happen—that’s a given by this point—but that students will come back to school having declined at vastly different rates.

“We might be facing unprecedented levels of variability come fall,” Kuhfeld told me. “Especially in school districts that serve families with lots of different needs and resources. Instead of having students reading at a grade level above or below in their classroom, teachers might have kids who slipped back a lot versus kids who have moved forward.”

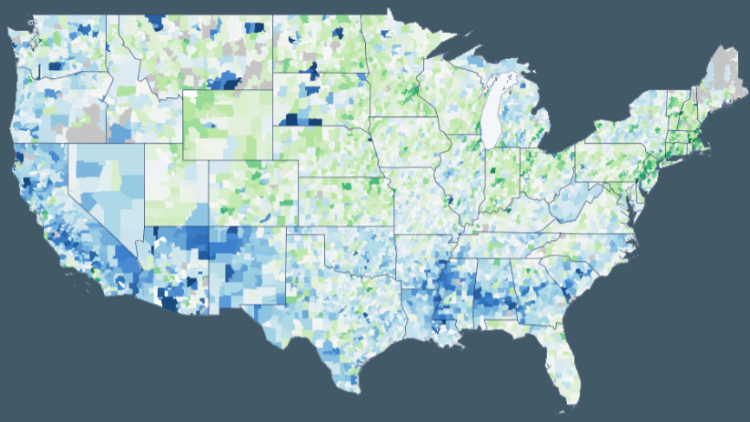

Disproportionate Impact on Students Living in Poverty and Students of Color

Horace Mann once referred to schools as the “great equalizers,” yet the pandemic threatens to expose the underlying inequities of remote learning. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center analysis , 17 percent of teenagers have difficulty completing homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection. For Black students, the number spikes to 25 percent.

“There are many reasons to believe the Covid-19 impacts might be larger for children in poverty and children of color,” Kuhfeld wrote in the study. Their families suffer higher rates of infection, and the economic burden disproportionately falls on Black and Hispanic parents, who are less likely to be able to work from home during the pandemic.

Although children are less likely to become infected with Covid-19, the adult mortality rates, coupled with the devastating economic consequences of the pandemic, will likely have an indelible impact on their well-being.

Impacts on Students’ Mental Health

That impact on well-being may be magnified by another effect of school closures: Schools are “the de facto mental health system for many children and adolescents,” providing mental health services to 57 percent of adolescents who need care, according to the authors of a recent study published in JAMA Pediatrics . School closures may be especially disruptive for children from lower-income families, who are disproportionately likely to receive mental health services exclusively from schools.

“The Covid-19 pandemic may worsen existing mental health problems and lead to more cases among children and adolescents because of the unique combination of the public health crisis, social isolation, and economic recession,” write the authors of that study.

A major concern the researchers point to: Since most mental health disorders begin in childhood, it is essential that any mental health issues be identified early and treated. Left untreated, they can lead to serious health and emotional problems. In the short term, video conferencing may be an effective way to deliver mental health services to children.

Mental health and academic achievement are linked, research shows. Chronic stress changes the chemical and physical structure of the brain, impairing cognitive skills like attention, concentration, memory, and creativity. “You see deficits in your ability to regulate emotions in adaptive ways as a result of stress,” said Cara Wellman, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at Indiana University in a 2014 interview . In her research, Wellman discovered that chronic stress causes the connections between brain cells to shrink in mice, leading to cognitive deficiencies in the prefrontal cortex.

While trauma-informed practices were widely used before the pandemic, they’re likely to be even more integral as students experience economic hardships and grieve the loss of family and friends. Teachers can look to schools like Fall-Hamilton Elementary in Nashville, Tennessee, as a model for trauma-informed practices .

3 Ways Teachers Can Prepare

When schools reopen, many students may be behind, compared to a typical school year, so teachers will need to be very methodical about checking in on their students—not just academically but also emotionally. Some may feel prepared to tackle the new school year head-on, but others will still be recovering from the pandemic and may still be reeling from trauma, grief, and anxiety.

Here are a few strategies teachers can prioritize when the new school year begins:

- Focus on relationships first. Fear and anxiety about the pandemic—coupled with uncertainty about the future—can be disruptive to a student’s ability to come to school ready to learn. Teachers can act as a powerful buffer against the adverse effects of trauma by helping to establish a safe and supportive environment for learning. From morning meetings to regular check-ins with students, strategies that center around relationship-building will be needed in the fall.

- Strengthen diagnostic testing. Educators should prepare for a greater range of variability in student learning than they would expect in a typical school year. Low-stakes assessments such as exit tickets and quizzes can help teachers gauge how much extra support students will need, how much time should be spent reviewing last year’s material, and what new topics can be covered.

- Differentiate instruction—particularly for vulnerable students. For the vast majority of schools, the abrupt transition to online learning left little time to plan a strategy that could adequately meet every student’s needs—in a recent survey by the Education Trust, only 24 percent of parents said that their child’s school was providing materials and other resources to support students with disabilities, and a quarter of non-English-speaking students were unable to obtain materials in their own language. Teachers can work to ensure that the students on the margins get the support they need by taking stock of students’ knowledge and skills, and differentiating instruction by giving them choices, connecting the curriculum to their interests, and providing them multiple opportunities to demonstrate their learning.

Resource Pack (3)

Resource Pack: Thematic (3)

Teaching Pack (3)

Teaching Pack: Lessons (3)

Publication (4)

Web Portal (2)

Middle-School Teachers (1)

High-School Teachers (3)

Digital/Media Literacy (2)

Data/Visualization (3)

Critical Thinking (6)

Leadership (3)

Global Learning (3)

Classroom (4)

Blended (4)

This " Teaching Toolkit " includes 6 individually curated collections to support teaching and learning about the COVID-19 pandemic. These include: Teaching Pack: COVID-19 Relevant Teaching Cases Resource Pack: COVID-19 in U.S: State Variation & Disparities Resource Pack: COVID-19 and Racism Resource Pack: Ethics, Human Rights, Pandemics Teaching Pack: COVID-19 Middle/High-School Resources Teaching Pack: COVID-19 College/Graduate Resources This toolkit is intended to be "educator-facing" and has been assembled by the Global Health Education and Learning Incubator at…

Teaching Toolkit

This Teaching Toolkit includes 6 individual collections curated to support teaching and learning about the COVID-19 pandemic. It provides educators with accessible, evidence-based information for curricula, teaching materials, student assignments and learning experiences.

How can educators leverage the COVID-19 pandemic to engage students in active learning? This collection …

How can educators leverage the COVID-19 pandemic to engage students in active learning? This collection of resources was curated to support high-school and middle-school teachers in bringing timely, high-quality material on the current COVID-19 pandemic into the "classroom" whether it be online, hybrid or physical. Each tile within the collection brings together a key resource on the topic and some sample activities, discussion prompts, or tools to generate ideas for teaching and learning. This teaching pack is…

This curated collection includes teaching cases that could serve as useful resources for educators teaching …

This curated collection includes teaching cases that could serve as useful resources for educators teaching about topics that are relevant to COVID-19, including but not limited to: pandemic risk preparedness, mitigation and response; policy coordination between federal, state and local government; drugs, vaccines and supply chains; international collective action and global governance. Cases include both domestic and international experiences with SARS, H1N1, H5N1, Ebola and COVID-19. While some cases are older, they represent the challenges,…

This set of resources provide insight into the trajectory and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic …

This set of resources provide insight into the trajectory and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Selected publications, data portals, interactives, and graphics depict the national experience over time, and allow users to explore the variation in epidemiology and outcomes by state and population subgroup. Resources were selected to also reflect particular attributes of the U.S. experience, such as the increasing evidence for racial disparities in terms of the most severe outcomes,…

This curated resource portal highlights racial injustice in the United States, spanning from racial disparities …

This curated resource portal highlights racial injustice in the United States, spanning from racial disparities in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) to the continued police violence experienced by persons of color. This sampling of resources provides an overview of the relationship between COVID-19 and the disproportionate number of cases and deaths experienced by Black Americans, broader health trends that result from racial inequities, and injury and mortality trends tied to police violence. The resource collection incorporates…

This curated resource collection includes reports, articles and guidelines that consider both ethics and human …

This curated resource collection includes reports, articles and guidelines that consider both ethics and human rights, as they relate to public health practice and clinical research in the setting of national and international emergencies, particularly epidemics and pandemics. In addition to ethical frameworks developed specifically for pandemic preparedness, the collection also includes insights from prior guidelines focusing on research, compassionate use therapeutics and vaccine trials for Ebola. Others resources outline how to conduct research effectively…

How can educators make course content relevant to learners? The current COVID-19 pandemic offers a …

How can educators make course content relevant to learners? The current COVID-19 pandemic offers a wealth of opportunities for college and graduate educators to integrate real-world events, salient to their students' everyday lives, into existing or new courses. This collection brings together timely, high-quality material that explores global and local patterns of disease, transmission and epidemiology, social determinants of health, health sector and non-health sector responses, and the variation in policies and their impact. Each…

Welcome to the Incubator's Digital Repository

Our digital repository is a searchable library of selected resources that support learning and teaching about interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary population health challenges across the globe. It includes general resources (e.g., reports, articles, country profiles, data, etc.) and teaching resources (e.g., teaching cases, curated resource packs, and lesson-based teaching packs). Open-access sources are prioritized, and include peer-reviewed journals, global reports from multilateral institutions and alliances, and knowledge-related public goods from reputable research and policy organizations.

Take a Video Tour

Download a 2-Page Explainer (PDF)

Download Self-Guided Tour (PDF)

How is COVID-19 affecting student learning?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, initial findings from fall 2020, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld senior research scientist - nwea @megankuhfeld jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea @jsoland beth tarasawa , bt beth tarasawa executive vice president of research - nwea @bethtarasawa angela johnson , aj angela johnson research scientist - nwea erik ruzek , and er erik ruzek research assistant professor, curry school of education - university of virginia karyn lewis karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea @karynlew.

December 3, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced uncertainty into major aspects of national and global society, including for schools. For example, there is uncertainty about how school closures last spring impacted student achievement, as well as how the rapid conversion of most instruction to an online platform this academic year will continue to affect achievement. Without data on how the virus impacts student learning, making informed decisions about whether and when to return to in-person instruction remains difficult. Even now, education leaders must grapple with seemingly impossible choices that balance health risks associated with in-person learning against the educational needs of children, which may be better served when kids are in their physical schools.

Amidst all this uncertainty, there is growing consensus that school closures in spring 2020 likely had negative effects on student learning. For example, in an earlier post for this blog , we presented our research forecasting the possible impact of school closures on achievement. Based on historical learning trends and prior research on how out-of-school-time affects learning, we estimated that students would potentially begin fall 2020 with roughly 70% of the learning gains in reading relative to a typical school year. In mathematics, students were predicted to show even smaller learning gains from the previous year, returning with less than 50% of typical gains. While these and other similar forecasts presented a grim portrait of the challenges facing students and educators this fall, they were nonetheless projections. The question remained: What would learning trends in actual data from the 2020-21 school year really look like?

With fall 2020 data now in hand , we can move beyond forecasting and begin to describe what did happen. While the closures last spring left most schools without assessment data from that time, thousands of schools began testing this fall, making it possible to compare learning gains in a typical, pre-COVID-19 year to those same gains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using data from nearly 4.4 million students in grades 3-8 who took MAP ® Growth™ reading and math assessments in fall 2020, we examined two primary research questions:

- How did students perform in fall 2020 relative to a typical school year (specifically, fall 2019)?

- Have students made learning gains since schools physically closed in March 2020?

To answer these questions, we compared students’ academic achievement and growth during the COVID-19 pandemic to the achievement and growth patterns observed in 2019. We report student achievement as a percentile rank, which is a normative measure of a student’s achievement in a given grade/subject relative to the MAP Growth national norms (reflecting pre-COVID-19 achievement levels).

To make sure the students who took the tests before and after COVID-19 school closures were demographically similar, all analyses were limited to a sample of 8,000 schools that tested students in both fall 2019 and fall 2020. Compared to all public schools in the nation, schools in the sample had slightly larger total enrollment, a lower percentage of low-income students, and a higher percentage of white students. Since our sample includes both in-person and remote testers in fall 2020, we conducted an initial comparability study of remote and in-person testing in fall 2020. We found consistent psychometric characteristics and trends in test scores for remote and in-person tests for students in grades 3-8, but caution that remote testing conditions may be qualitatively different for K-2 students. For more details on the sample and methodology, please see the technical report accompanying this study.

In some cases, our results tell a more optimistic story than what we feared. In others, the results are as deeply concerning as we expected based on our projections.

Question 1: How did students perform in fall 2020 relative to a typical school year?

When comparing students’ median percentile rank for fall 2020 to those for fall 2019, there is good news to share: Students in grades 3-8 performed similarly in reading to same-grade students in fall 2019. While the reason for the stability of these achievement results cannot be easily pinned down, possible explanations are that students read more on their own, and parents are better equipped to support learning in reading compared to other subjects that require more formal instruction.

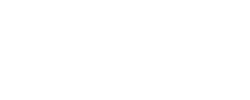

The news in math, however, is more worrying. The figure below shows the median percentile rank in math by grade level in fall 2019 and fall 2020. As the figure indicates, the math achievement of students in 2020 was about 5 to 10 percentile points lower compared to same-grade students the prior year.

Figure 1: MAP Growth Percentiles in Math by Grade Level in Fall 2019 and Fall 2020

Source: Author calculations with MAP Growth data. Notes: Each bar represents the median percentile rank in a given grade/term.

Question 2: Have students made learning gains since schools physically closed, and how do these gains compare to gains in a more typical year?

To answer this question, we examined learning gains/losses between winter 2020 (January through early March) and fall 2020 relative to those same gains in a pre-COVID-19 period (between winter 2019 and fall 2019). We did not examine spring-to-fall changes because so few students tested in spring 2020 (after the pandemic began). In almost all grades, the majority of students made some learning gains in both reading and math since the COVID-19 pandemic started, though gains were smaller in math in 2020 relative to the gains students in the same grades made in the winter 2019-fall 2019 period.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of change in reading scores by grade for the winter 2020 to fall 2020 period (light blue) as compared to same-grade students in the pre-pandemic span of winter 2019 to fall 2019 (dark blue). The 2019 and 2020 distributions largely overlapped, suggesting similar amounts of within-student change from one grade to the next.

Figure 2: Distribution of Within-student Change from Winter 2019-Fall 2019 vs Winter 2020-Fall 2020 in Reading

Source: Author calculations with MAP Growth data. Notes: The dashed line represents zero growth (e.g., winter and fall test scores were equivalent). A positive value indicates that a student scored higher in the fall than their prior winter score; a negative value indicates a student scored lower in the fall than their prior winter score.

Meanwhile, Figure 3 shows the distribution of change for students in different grade levels for the winter 2020 to fall 2020 period in math. In contrast to reading, these results show a downward shift: A smaller proportion of students demonstrated positive math growth in the 2020 period than in the 2019 period for all grades. For example, 79% of students switching from 3 rd to 4 th grade made academic gains between winter 2019 and fall 2019, relative to 57% of students in the same grade range in 2020.

Figure 3: Distribution of Within-student Change from Winter 2019-Fall 2019 vs. Winter 2020-Fall 2020 in Math

It was widely speculated that the COVID-19 pandemic would lead to very unequal opportunities for learning depending on whether students had access to technology and parental support during the school closures, which would result in greater heterogeneity in terms of learning gains/losses in 2020. Notably, however, we do not see evidence that within-student change is more spread out this year relative to the pre-pandemic 2019 distribution.

The long-term effects of COVID-19 are still unknown

In some ways, our findings show an optimistic picture: In reading, on average, the achievement percentiles of students in fall 2020 were similar to those of same-grade students in fall 2019, and in almost all grades, most students made some learning gains since the COVID-19 pandemic started. In math, however, the results tell a less rosy story: Student achievement was lower than the pre-COVID-19 performance by same-grade students in fall 2019, and students showed lower growth in math across grades 3 to 8 relative to peers in the previous, more typical year. Schools will need clear local data to understand if these national trends are reflective of their students. Additional resources and supports should be deployed in math specifically to get students back on track.

In this study, we limited our analyses to a consistent set of schools between fall 2019 and fall 2020. However, approximately one in four students who tested within these schools in fall 2019 are no longer in our sample in fall 2020. This is a sizeable increase from the 15% attrition from fall 2018 to fall 2019. One possible explanation is that some students lacked reliable technology. A second is that they disengaged from school due to economic, health, or other factors. More coordinated efforts are required to establish communication with students who are not attending school or disengaging from instruction to get them back on track, especially our most vulnerable students.

Finally, we are only scratching the surface in quantifying the short-term and long-term academic and non-academic impacts of COVID-19. While more students are back in schools now and educators have more experience with remote instruction than when the pandemic forced schools to close in spring 2020, the collective shock we are experiencing is ongoing. We will continue to examine students’ academic progress throughout the 2020-21 school year to understand how recovery and growth unfold amid an ongoing pandemic.

Thankfully, we know much more about the impact the pandemic has had on student learning than we did even a few months ago. However, that knowledge makes clear that there is work to be done to help many students get back on track in math, and that the long-term ramifications of COVID-19 for student learning—especially among underserved communities—remain unknown.

Related Content

Jim Soland, Megan Kuhfeld, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, Jing Liu

May 27, 2020

Amie Rapaport, Anna Saavedra, Dan Silver, Morgan Polikoff

November 18, 2020

Education Access & Equity K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Sofoklis Goulas, Isabelle Pula

May 16, 2024

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Elizabeth D. Steiner, Ashley Woo

Dr. Neil A. Lewis, Jr.

May 14, 2024

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Nonacademic factors in college searches.

Sarah Wood May 28, 2024

Takeaways From the NCAA’s Settlement

Laura Mannweiler May 24, 2024

New Best Engineering Rankings June 18

Robert Morse and Eric Brooks May 24, 2024

Premedical Programs: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 21, 2024

How Geography Affects College Admissions

Cole Claybourn May 21, 2024

Q&A: College Alumni Engagement

LaMont Jones, Jr. May 20, 2024

10 Destination West Coast College Towns

Cole Claybourn May 16, 2024

Scholarships for Lesser-Known Sports

Sarah Wood May 15, 2024

Should Students Submit Test Scores?

Sarah Wood May 13, 2024

Poll: Antisemitism a Problem on Campus

Lauren Camera May 13, 2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 25 March 2023

The impact of the first wave of COVID-19 on students’ attainment, analysed by IRT modelling method

- Rita Takács ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0314-4179 1 ,

- Szabolcs Takács ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9128-9019 2 , 3 ,

- Judit T. Kárász ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6198-482X 4 , 5 ,

- Attila Oláh 6 , 7 &

- Zoltán Horváth 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 127 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3219 Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Universities around the world were closed for several months to slow down the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. During this crisis, a tremendous amount of effort was made to use online education to support the teaching and learning process. The COVID-19 pandemic gave us a profound insight into how online education can radically affect students and how students adapt to new challenges. The question is how switching to online education affected dropout? This study shows the results of a research project clarifying the impact of the transition to online courses on dropouts. The data analysed are from a large public university in Europe where online education was introduced in March 2020. This study compares the academic progress of students newly enroled in 2018 and 2019 using IRT modelling. The results show that (1) this period did not contribute significantly to the increase in dropout, and we managed to retain our students.(2) Subjects became more achievable during online education, and students with less ability were also able to pass their exams. (3) Students who participated in online education reported lower average grade points than those who participated in on-campus education. Consequently, on-campus students could win better scholarships because of better grades than students who participated in online education. Analysing students’ results could help (1) resolve management issues regarding scholarship problems and (2) administrators develop programmes to increase retention in online education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Impact of artificial intelligence on human loss in decision making, laziness and safety in education

Interviews in the social sciences

Introduction.

During the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, several countries closed their university buildings and switched to online education. Some opinions suggest that online education had a negative effect on dropouts because of several factors, e.g., lack of social connections, poor contact with teachers. In bachelor’s programmes—like university courses in computer science—where dropout rates were high prior to the pandemic, many questions were raised about the impact of the transition to online education.

This study focuses on the effects of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ dropouts and performance in Hungary. Although the manuscript addresses academic dropout, other issues such as inequality or accessibility were also covered in the research.

Theoretical background

Educational theory about student dropout in higher education.

Tinto ( 1975 ) was the first researcher who analysed the dropout phenomenon and invented the interactional theory of student persistence in higher education. He ( 2012 ) highlighted the interactions between the student and the institution regarding how well they fit in academically and socially. Interactional theories suggest that students’ personal characteristics, traits, experience, and commitment can have an effect on students’ persistence (Pascarella and Terenzini, 1983 ; Terenzini and Reason, 2005 ; Reason, 2009 ). Braxton and Hirschy ( 2004 ) also emphasized the need for community on campus as a help of social integration to develop relationships between peers because interactions with other students and faculty members crucially determine whether students persist and continue their studies or leave.

The student dropout rate has been a crucial issue in higher education in the last two decades. Attrition has serious consequences on the individual (e.g., Nagrecha et al., 2017 ) at both economic (Di Pietro, 2006 ; Belloc et al., 2011 ) and educational (Cabrera et al., 2006 ) levels. As a worldwide phenomenon, it draws the attention of policy-makers, stake-holders and academics to the necessity of seeking solutions. The dropout crisis requires complex intervention programmes for encouraging students in order to complete their studies. Addressing such a dropout crisis requires an actionable interdisciplinary movement based on partnerships among stake-holders and academics.

According to Vision 2030 studies published by the European Union, education is vital for economic development because it has a direct influence on entrepreneurship and productivity growth; at the same time, it increases employment opportunities and women empowerment. Education helps to reduce unemployment and enhance students’ abilities and skills that will be needed in the labour market. Due to students’ high attrition, the economy also suffers because experts with a degree usually contribute more to the GDP than people without (Whittle and Rampton, 2020 ).

A comparative analysis of past studies has been conducted in order to identify various causes of students’ dropout. Students’ performance after the first academic year is a topic of significant interest: the lack of students' engagement in academic life and their unpreparedness are mainly responsible for dropout after the first highly crucial period. However, further studies are necessary to better understand this phenomenon.

The characteristics of online education and its effect on dropout

Online education had already existed before the COVID-19 pandemic and had had a vast literature because online courses had been playing an important role in higher education. Online education has its own benefits, e.g., it enables students to work from the comfort of their homes with more convenient, accessible materials. In recent years, numerous investigations have been performed on how to increase the motivation of students by making them feel engaged during the learning processes (Molins-Ruano et al., 2014 ; Jovanovic et al., 2019 ). The other benefit is “humanizing”, which is an academic strategy that looks for solutions to improve equity gaps by recognizing the fact that learning situations are not the same for everyone. The aim of humanizing education is to remove the affective and cognitive barriers which appear during online learning and to provide a technique in higher education towards a more equitable future in which the success of all students is supported (Pacansky-Brock and Vincent-Layton, 2020 ). Humanizing online STEM courses has specific significance because creating such academic pathways can especially help the graduation of vulnerable, for example, non-traditional students. The definition of a non-traditional student belongs to Bean and Metzner ( 1985 ), who distinguished students by different characteristics. Non-traditional students are not on-campus students (but they can participate in online education), who are usually aged 24 years or older, and dominantly have a job and/or a family. Non-traditional students have less interaction with other participants in education, and they are much more influenced by other factors, e.g., family or other external responsibilities. Financial factors, family attitudes and external incentives can also influence dropout. The dropout model for non-traditional university students highlights that underperforming students are likely to leave the institution. Carr ( 2000 ) (in Rovai, 2003 ) noticed that persistence in online courses is regularly 10–20% lower than in on-campus courses. The dropout rate differs from institution to institution: some reports claim that 80% of students graduated, whereas other findings show that less than 50% of students completed their courses. Humanizing recognizes that engagement and accomplishment are the key factors in students’ success. Engagement and achievement are social constructs created through students’ experience. Teachers can help students to socialize and adapt to the academic environment by using humanizing practices like a liquid syllabus. Stommel ( 2013 ) also considers that hybrid pedagogy is a useful tool in order to support students’ learning because it helps teachers to implement new learning activities and facilitate collaboration among students.

Despite the various benefits that online education has, the success of students depends on the student’s capacity to independently and effectively engage in the learning process (Wang et al., 2013 ). Online learners are required to be more autonomous, as the exceptional nature of online settings relies on self-directed learning (Serdyukov and Hill, 2013 ). It is therefore especially critical that online learners, compared to their conventional classroom peers, have the self-generated capacity to control and manage their learning activities.

Online education also needs extra attention because the dropout rate is high in online university programmes. Students in online courses are more likely to drop out (Patterson and McFadden, 2009 ; in Nistor and Neubauer, 2010 ). Numerous studies reported much higher dropout rates than in the case of on-campus courses (Willging and Johnson, 2019 ; Levy, 2007 ; Morris et al., 2005 ; Patterson and McFadden, 2009 ; in Nistor and Neubauer, 2010 ). Many factors that lead to dropout were examined in the past. During online courses, students are less likely to form communities or study groups and the lack of learning support can lead to isolation. Consequently, demotivated students who were dedicated to their chosen major, in the beginning, may decide to drop out. Fortunately, there are different ways to support students who study in an online setting depending on their various psychological attributes. These psychological attributes that are connected to dropout have already been examined. One of the most noticeable hypothetical models of university persistence in online education was proposed by Rovai ( 2003 ). He claims that dropout depends on students’ characteristics e.g., learning style, socioeconomic status, studying skills, etc. Besides these factors, the method of education also has an impact on students’ decisions on whether they complete the course or drop out.

It is vital to distinguish the online education that was introduced as a consequence of the COVID-19 lockdown, when universities were forced to move their education to fully online platforms because online education had already existed in some educational institutions.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on education: Inequalities in home learning and colleges’ provision of distance teaching during school closure of the COVID-19 lockdown

The lives of millions of college students were affected not only by the health and economic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic but also by the closure of educational institutions. Home and academic environments were interlaced, and most institutions were caught unprepared. In this article, we examine the effects of the transition to online learning in areas such as academic attainment.

There are several debates on the effectiveness of moving to online education. Since currently there is little literature about the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to how it affects dropouts at universities, it is worth discussing it in order to have an overview of recent studies on students’ performance. The learning environment changed radically during the first wave of the pandemic in the spring semester of 2020. The transition to home learning and teaching in such a short time without any warning or preparation raised concerns and became the focus of attention for researchers, teachers, policymakers, and all those interested in the educational welfare of students.

A potential learning loss was anticipated, possibly affecting students’ cognitive gains in the long term (Andrew et al., 2020 ; Bayrakdar and Guveli, 2020 ; Brown et al., 2020 ); in fact, an increasing number of studies suggested that the lockdown might have far-reaching academic consequences (Bol, 2020 ). In general, results suggest that students’ motivation was substantially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and that academic and relational changes were the most notable sources of stress on both the students’ side (e.g., Rahiem, 2021 ) and the teachers’ side (e.g., Abilleira et al., 2021 ; Daumiller et al., 2021 ). Engzell et al. ( 2021 ) examined nearly 350,000 students’ academic performance before and after the first wave of the pandemic in the Netherlands. Their results suggest that students made very little development while learning from home. Closures also had a substantial effect on students’ sense of belonging and self-efficacy. Academic knowledge loss could be even more severe in countries with less advanced infrastructure or a longer period of college closures (OECD, 2020 ).

Many researchers started to examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ mental health and academic performance. Clark et al. ( 2021 ) claim that university students are increasingly considered a vulnerable population, as they experience extremely high levels of stress. They draw attention to the fact that students might suffer more from learning difficulties. Daniels et al. ( 2021 ) used a single survey to collect retrospective self-report data from Canadian undergraduate students ( n = 98) about their motivation, engagement and perceptions of success and cheating before COVID-19, which shows that students’ achievements, goals, engagement and perception of success all significantly decreased, while their perception of cheating increased (Daniels et al., 2021 ). Other studies claim that during the COVID-19 pandemic, students were more engaged in studying and had higher perceptions of success. Studies also show that teachers’ strategies changed as well because of the lack of interaction between teachers and students, which led to the fact that students experienced more stress and were more likely to have difficulties in following the material presented and it could be one of the reasons for poor academic performance. Mendoza et al. ( 2021 ) investigated the relationships between anxiety and students’ performance during the first wave of the pandemic among college students. Anxiety regarding learning mathematics was measured among mathematics students studying at the Universidad Nacional de Chimborazo (UNACH) during the autumn semester of the academic year 2020. The total sample contained 120 students, who were studying the subject of mathematics at different levels. The results showed that there were statistically significant differences in the understanding of the contents presented by the teachers in a virtual way. During the COVID-19 pandemic the levels of mathematical anxiety increased. Teaching mathematics at university in an online format requires good quality digital connection and time-limited submission of assignments. This study draws attention to the negative result of the pandemic, i.e. the levels of anxiety might be greater during online education and not only in mathematics education but also in other subjects. Thus it could have an effect on students’ academic performance. However, the results are contradictory to what Said ( 2021 ) found, i.e. there was no difference in students’ performance before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In their empirical study, they investigated the effect of the shift from face-to-face to online distance learning at one of the universities in Egypt. They compared the grades of 376 business students who participated in a face-to-face course in spring 2019 and those of 372 students who participated in the same course fully online in spring 2020 during the lockdown. A T -test was conducted to compare the grades of quizzes, coursework, and final exams of the two groups. The results suggested that there was no statistically significant difference. Another interesting result was that in some cases students had a better performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. At a large public university in Spain, Iglesias-Pradas et al. ( 2021 ) analysed the following instruction-related variables: class size, synchronous/asynchronous delivery of classes, and the use of digital supporting technologies on students’ academic performance. The research compared the academic results of the students during the COVID-19 pandemic with those of previous years. Using quantitative data from academic records across all ( n = 43) courses of a bachelor’s degree programme, the study showed an increase in students’ academic performance during the sudden shift to online education. Gonzalez et al. ( 2020 ) had similar results. Their research group analysed the effects of COVID-19 on the autonomous learning performance of students. 458 students participated in their studies. In the control group, students started their studies in 2017 and 2018, while in the experimental group, students started in 2019. The results showed that there was a significant positive effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on students’ performance: students had changed their learning strategies and improved their efficiency by studying more continuously. Yu et al. ( 2021 ) found similar results. They used administrative data from students’ grade tracking systems and found that the causal effects of online education on students’ exam performance were positive in a Chinese middle school. Taking a difference-in-differences approach, they found that receiving online education during the COVID-19 lockdown improved students’ academic results by 0.22 of a standard deviation (Yu et al., 2021 ).

Currently, there is little literature about COVID-19 in relation to how it affects students’ performance at universities, so it is worth discussing this aspect as well.

Teachers’ approach to their grading strategies and shift to online education during the COVID-19 lockdown

There is a vast literature on the limits of the capacities and challenges of online education (Davis et al., 2019 ; Dumford and Miller, 2018 ; Palvia et al., 2018 ). The lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic created new challenges for teachers all over the world and called for innovative teaching techniques (Adedoyin and Soykan, 2020 ; Gamage et al., 2020 ; Paudel, 2020 ; Peimani and Kamalipour, 2021 ; Rapanta et al., 2020 ; Watermeyer et al., 2021 ). These changes had undoubtedly profound impacts on the academic discourse and everyday practices of teaching. Teachers’ motivations for maintaining effective online teaching during the lockdown were diverse and complex, and therefore, learning outcomes were difficult to be guaranteed. Yu et al. ( 2021 ) examined how innovative teaching could be continued during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly by learning domain-specific knowledge and skills. The results confirmed that during the lockdown teachers who had studied online teaching methods improved their teaching skills and ICT (information and communication technology) efficacy.

Burgess and Sievertsen ( 2020 ) claim that due to the COVID-19 lockdown, educational institutions might cause major interruptions in students’ learning process. Disruption appeared not only in elaborating new knowledge but also in assessment. Given the proof of the significance of exams and tests for learning, educators had to consider postponing rather than renounce assessments. Akar and Coskun ( 2020 ) found that innovative teaching had a slight but positive relationship with creativity. From their point of view, it was not necessarily a consequence of shifting offline teaching to online platforms. Innovative teaching and digital technology were not granted and their impact on student’s performance or teachers’ grading practices is still unclear. The present research aimed to analyse students’ attainment during the COVID-19 pandemic by using student performance data. We focused on the relationship between participation in online courses and dropout decisions, which is connected to teachers’ grading. Examining how grades changed during the lockdown could give us an interesting insight into the educational inequality caused by online education regarding the scholarship system based on student’s grades.

Research questions

We know very little about the effects of transitioning to online education on student dropout and teachers’ grading practices. Even less information is available on the relationship between COVID-19 and dropout, so it is worth a discussion due to the existing controversial and interesting studies on students’ performance. This article gives a suggestion on how the scholarship system could be changed and how we could avoid inequality caused by online education. There is a scholarship system in Hungary that provides financial support to full-time programme students, based on their academic achievement.

Another issue we discuss in this article is dropping out from university programmes, which is a crucial issue worldwide. Between 2010 and 2016 at a large public university in Europe (over 30,000 students) the overall attrition rate is 30%, with the Faculty of Informatics having the worst results (60%) but nowadays these figures are more promising (30|40%). These days at least 800,000 computer scientists may be needed in Europe (Europa.eu, 2015 ), but it seems to be a worldwide issue (Borzovs et al., 2015 ; Ohland et al., 2008 ) to retain students.

This study focuses on the effects of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ dropout and performance in Hungary. Although the manuscript addresses academic dropout, other issues such as inequality or accessibility are also covered in the research. The aim of the paper is therefore to investigate the following questions:

It is inconclusive whether the COVID-19 pandemic had negative effects on students’ performance, which is why we claim that

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant difference in grade point averages between students who participated in online education and those in on-campus education in the second semester of their studies.

Academic achievement (in both traditional and online learning settings) can be measured by accomplishing a specific result in an online assignment and is commonly expressed in terms of a grade point average (GPA; Lounsbury et al., 2005 ; Richardson et al., 2012 ; Wang, 2010 ). According to meta-analyses, GPA is one of the best predictors of dropout (Richardson et al., 2012 ; Broadbent and Poon, 2015 ).

Hypothesis 2: In some subjects (Basic Mathematics practice, Programming, Imperative Programming lecture + practice, Functional Programming, Object-oriented Programming practice + lecture, Algorithms and Data Structures lecture + practice, Discrete Mathematics practice and Analysis practice), it was easier to obtain a passing grade in online education.

Hypothesis 3: More of the students who participated in online education dropped out than those who received on-campus education.

Difficulty and differential analysis of subjects

In the examined higher education system, a BSc programme has six semesters and every subject is graded on a five-point scale, where 1 means fail, and grades from 2 to 5 mean pass, with 5 being the best grade. In the analysis only the final grades were counted in each subject. It is important to see that in order to achieve better grades (or obtain sufficient knowledge), a subject really needs differentiation. It is worth examining the subjects of the various courses because—although there are grades—there is some kind of expected knowledge or skill that the subject should measure. Students are expected to develop these competencies or at least reach an expected level by the end of the semester. To find out whether this kind of competency actually exists (and was developed during online education) and whether the subjects measure this kind of competency, Item Response Theory (IRT) analysis was used to examine the subjects included in the computer science BSc programme. The aim of IRT analysis modelling is to bring the difficulty of the subjects and the ability of the students to the same scale (GRM, Forero and Maydeu-Olivares, 2009 ; Rasch, 1960 ). We had already successfully applied a special IRT model in order to analyse the effects of a student retention programme. In order to prevent student dropout, in a large public university in Europe, a prevention and promotion programme was added to the bachelor’s programme and an education reform was also implemented. In most education systems students have to collect 30 credits per semester by successfully completing 8|10 subjects. We conducted an analysis using data science techniques and the most difficult subjects were identified. As a result, harder subjects were removed, and more introductory courses were built into the curriculum of the first year. A further action—as an intervention—was added to a computer science degree programme: all theoretical lectures became compulsory to attend. According to the results, the dropout level decreased by 28%. The most important benefit of the education reform was that most subjects had become accomplishable (Takács et al., 2021 ). Footnote 1

Hypothesis 1 claims that the online transition due to COVID-19 during the second semester of the 2019 academic year did not result in a change in the requirement system of the subjects. Hypothesis 2 claims that essentially the same expectations were formulated by teachers. In contrast, the way teachers evaluate students necessarily changed. A subject with a given difficulty could be passed by a student with the same ability level with a given probability. Obviously, all subjects that had been less difficult were more likely to be correctly passed than more difficult subjects. The analysis was performed using the IRT, based on the STATA15 software package.

In the study, 862 students were involved in the bachelor’s computer science programme. There were 438 (415) students who started on-campus education in 2018 and 447 students who started on-campus education in 2019, but from March 2020 they participated in online education (Table 1 ). Table 1 shows the result of Hypothesis 1: The grade point average of students who participated in online education (2.5) was lower than that of students who participated in on-campus education (3.3). Table 1 also shows that 447 students participated in online education and only 19 dropped out; 438 students started on-campus education and 50 dropped out. We can conclude that there was no significant difference between students’ dropping out who participated in online education and those who received on-campus education (Hypothesis 3). Note: We can conclude that the grade point average of students who participated in online education (2.5) was lower than that of students who participated in on-campus education (3.3) (Hypothesis 1). On the other hand, there was no significant difference between the drop-out rate of students’ who participated in online education and that of those who received on-campus education (Hypothesis 3). These case numbers make it unnecessary to apply any statistical evidence because the result is obvious.

The subjects were examined by fitting a 2-parameter IRT model to them (scale 1–5 with grades, assuming an ordinal model using the STATA15 programme). ‘Grades’ mean the final grade of the subjects. The STATA15.0 software package was used for the analysis, and the Graded Response Model version of the Ordered item models was chosen from the IRT procedures (GRM; Forero and Maydeu-Olivares, 2009 ).

During the procedure, we examined two parameters: the difficulty of the items and the slope. We took into account those subjects for which the subject matter of the subject remained the same over the years, or the exams did not change substantially (exam grade, according to the same assessment criteria). However, it is important to note that obviously, not the same students completed the assignments each year.

The study involved the following subjects (only professional subjects were considered):

Mathematical Foundations

Programming

Computer Systems lecture+practice

Imperative Programming

Functional Programming

Object-oriented Programming lecture + practice

Algorithms and Data Structures I. lecture

Algorithms and Data Structures I. practice

Discrete Mathematics I. lecture

Discrete Mathematics I. practice

Analysis I. L

Analysis I. P

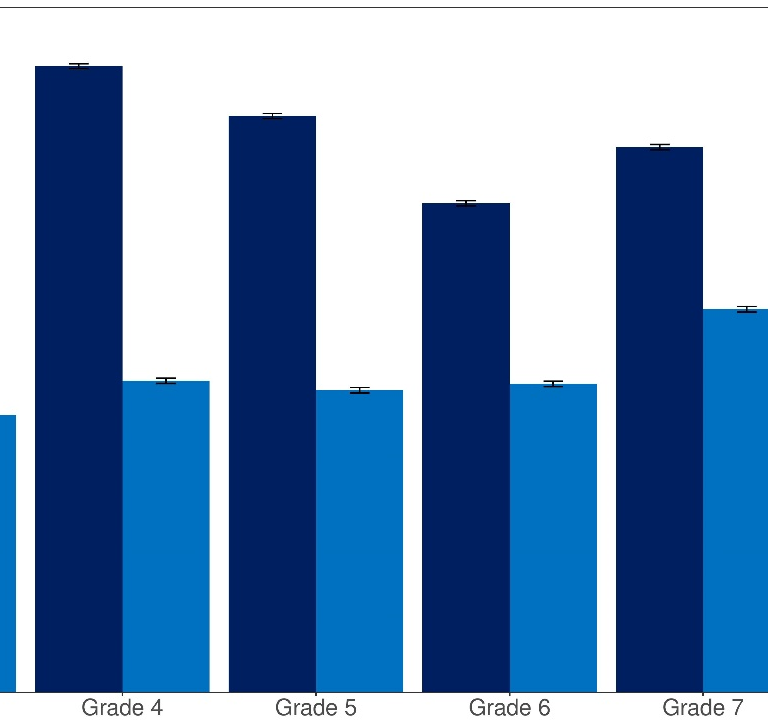

Examination of slope and difficulty coefficients

In this section, we examine Table 2 . As a first step, it is crucial to understand the slope indices of the given objects in different years, whether they change from one year to another. Table 2 shows the result of Hypothesis 2: In most subjects (Basic Mathematics practice, Programming, Imperative Programming lecture + practice, Functional Programming, Object-oriented Programming practice+lecture, Algorithms and Data Structures lecture + practice, Discrete Mathematics practice, and Analysis practice), it was easier to obtain a passing grade in online education.

Two parametric procedures were applied: each subject has a difficulty index and a slope.

While if the student’s ability falls short of the difficulty, the denominator of the fraction will increase, so the probability that the student will be able to pass the exam will increase—they will earn a good grade (Fig. 1 ).

Difficulty levels of the subjects in 2018 and 2019 academic year.

Instead of introducing the whole subject network, we introduce a typical subject that was analysed using the IRT. The analyses of the subject of Discrete Mathematics enable us to adequately illustrate the classic phenomenon that arose. The complete analysis of the subjects can be found in Table 2 .

The period before 2019 and after 2019 are shown separately in the table, as at the beginning of 2020 the lockdown took place when online education was introduced to all students so it had an impact on academic achievement. We presupposed that it had manifested itself in the subjects’ completing difficulty and in their ability to differentiate.

Discrete mathematics I. practice