21 Great Examples of Discourse Analysis

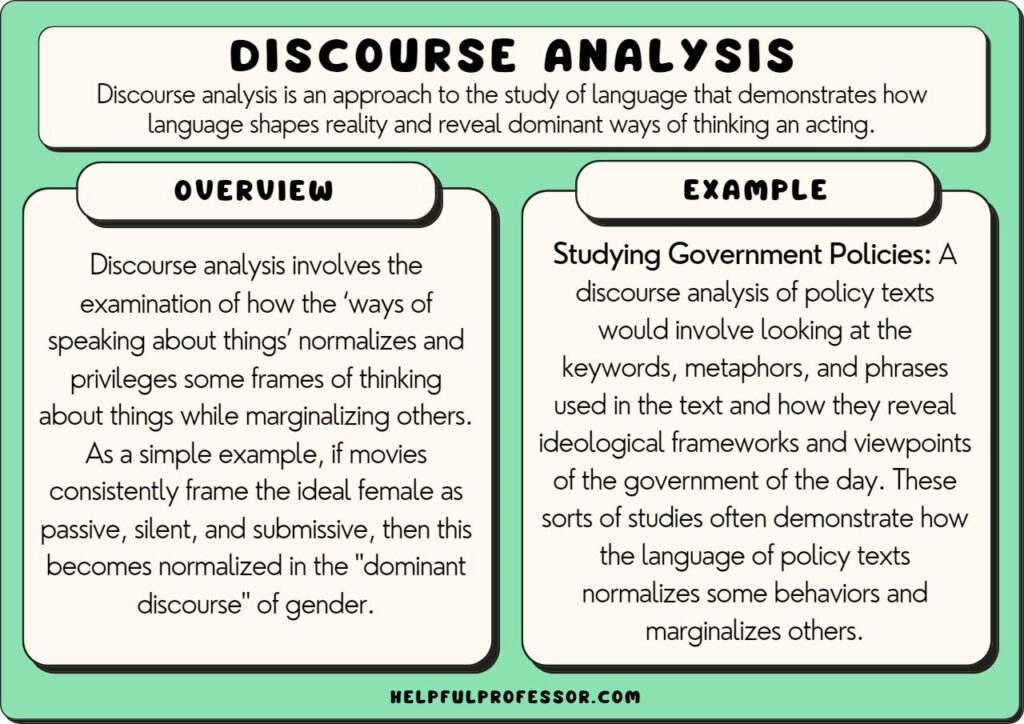

Discourse analysis is an approach to the study of language that demonstrates how language shapes reality. It usually takes the form of a textual or content analysis .

Discourse is understood as a way of perceiving, framing, and viewing the world.

For example:

- A dominant discourse of gender often positions women as gentle and men as active heroes.

- A dominant discourse of race often positions whiteness as the norm and colored bodies as ‘others’ (see: social construction of race )

Through discourse analysis, scholars look at texts and examine how those texts shape discourse.

In other words, it involves the examination of how the ‘ways of speaking about things’ normalizes and privileges some frames of thinking about things while marginalizing others.

As a simple example, if movies consistently frame the ideal female as passive, silent, and submissive, then society comes to think that this is how women should behave and makes us think that this is normal , so women who don’t fit this mold are abnormal .

Instead of seeing this as just the way things are, discourse analysts know that norms are produced in language and are not necessarily as natural as we may have assumed.

Examples of Discourse Analysis

1. language choice in policy texts.

A study of policy texts can reveal ideological frameworks and viewpoints of the writers of the policy. These sorts of studies often demonstrate how policy texts often categorize people in ways that construct social hierarchies and restrict people’s agency .

Examples include:

| The Chronic Responsibility: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Danish Chronic Care Policies(Ravn, Frederiksen & Beedholm, 2015) | The authors examined Danish chronic care policy documents with a focus on how they categorize and pathologize vulnerable patients. |

| The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: a Critical Discourse Analysis (Thomas, 2005) | The author examines how an education policy in one state of Australia positions teacher professionalism and teacher identities. While there are competing discourses about professional identity, the policy framework privileges a narrative that frames the ‘good’ teacher as one that accepts ever-tightening control and regulation over their professional practice. |

2. Newspaper Bias

Conducting a critical discourse analysis of newspapers involves gathering together a quorum of newspaper articles based on a pre-defined range and scope (e.g. newspapers from a particular set of publishers within a set date range).

Then, the researcher conducts a close examination of the texts to examine how they frame subjects (i.e. people, groups of people, etc.) from a particular ideological, political, or cultural perspective.

| Rohingya in media: Critical discourse analysis of Myanmar and Bangladesh newspaper headlines (Isti’anah, 2018) | The author explores the framing of the military attacks on Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar in the 2010s. They compare Bangladesh and Myanmar newspapers, showing that the Bangladesh newspapers construct the Rohingya people as protagonists while the Myanmar papers construct the military as the protagonists. |

| House price inflation in the news: a critical discourse analysis of newspaper coverage in the UK (Munro, 2018) | The study looks at how newspapers report on housing price rises in the UK. It shows how language like “natural” and “healthy” normalizes ever-rising housing prices and aims to dispel alternative discourses around ensuring access to the housing market for the working class. |

| Immigrants and the Western media: a critical discourse analysis of newspaper framings of African immigrant parenting in Canada (Alaazi et al, 2021) | This study looked at 37 Canadian newspaper articles about African immigrant parenting. It finds that African immigrants are framed as inferior in their parenting methods to other Canadian parents. |

3. Language in Interviews

Discourse analysis can also be utilized to analyze interview transcripts. While coding methods to identify themes are the most common methods for analyzing interviews, discourse analysis is a valuable approach when looking at power relations and the framing of subjects through speech.

| What is the practice of spiritual care? A critical discourse analysis of registered nurses’ understanding of spirituality (Cooper et al, 2020) | This study looks at transcripts of interviews with nurses and identified four ways of framing their own approach to spirituality and how it intersects with their work: these are the personal, holistic, and empathetic care . |

| An Ideological Unveiling: Using Critical Narrative and Discourse Analysis to Examine Discursive White Teacher Identity (Coleman, 2018) | This case study looks only at one teacher’s discursive construction of (i.e. the way they talk about and frame) their own whiteness. It shows how teacher education needs to work harder at challenging white students to examine their own white privilege. |

4. Television Analysis

Discourse analysis is commonly used to explore ideologies and framing devices in television shows and advertisements.

Due to the fact advertising is not just textual but rather multimodal , scholars often mix a discourse analytic methodology (i.e. exploring how television constructs dominant ways of thinking) with semiotic methods (i.e. exploration of how color, movement, font choice, and so on create meaning).

I did this, for example, in my PhD (listed below).

| Ideologies of Arab media and politics: a critical discourse analysis of Al Jazeera debates on the Yemeni revolution (Al Kharusi, 2016) | This study transcribed debates on Al Jazeera in relation to the Yemeni revolution and found overall bias against the Yemeni government. |

| Soak up the goodness: Discourses of Australian childhoods on television advertisements (Drew, 2013) | This study explores how Australian childhood identities are constructed through television advertising. It finds that national identity is normalized as something children have from the earliest times in their lives, which may act to socialize them into problematic nationalist attitudes in their formative years. |

5. Film Critique

Scholars can explore discourse in film in a very similar way to how they study discourse in television shows. This can include the framing of sexuality gender, race, nationalism, and social class in films.

A common example is the study of Disney films and how they construct idealized feminine and masculine identities that children should aspire toward.

| Child Rearing and Gender Socialisation: A Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis of Kids’ Popular Fictional Movies (Baig, Khan & Aslam, 2021) | The study shows how the films and construct gendered identities where women are kinder and depicted as attractive to other characters, while men are more active and seek roles as heroes. |

| Critical Discourse Analysis of Gender Representation of Male and Female Characters in the Animation Movie, FROZEN (Alsaraireh, Sarjit & Hajimia, 2020) | This study acknowledges the changes in how Disney films . It shows how women are active protagonists in the film but also shows how the protagonists continue to embody traditional feminine identities including their embrace of softness, selflessness, and self-sacrifice. |

6. Analysis of Political Speech

Political speeches have also been subject to a significant amount of discourse analysis. These studies generally explore how influential politicians indicate a shift in policy and frame those policy shifts in the context of underlying ideological assumptions.

| A Critical Discourse Analysis of Anti-Muslim Rhetoric in Donald Trump’s Historic 2016 AIPAC Policy Speech (Khan et al, 2020) | This study looked at Donald Trump’s use of language to construct a hero-villain and protagonist-other approach to American and Islam. |

| Critical discourse analysis in political communication research: a case study of rightwing populist discourse in Australia (Sengul, 2019) | This author highlights the role of political speech in constructing a singular national identity that attempts to delineate in-groups and out-groups that marginalize people within a multicultural nation. |

9. Examining Marketing Texts

Advertising is more present than ever in the context of neoliberal capitalism. As a result, it has an outsized role in shaping public discourse. Critical discourse analyses of advertising texts tend to explore how advertisements, and the capitalist context that underpins their proliferation, normalize gendered, racialized, and class-based discourses.

| Study | |

|---|---|

| A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis of Online Soft Drink Advertisements (Suphaborwornrat & Piyaporn Punkasirikul, 2022) | This study of online soft drink advertisements contributes to a body of literature that shows how advertising often embraces masculine to appeal to their target audience. However, by repeatedly depicting masculinity, a discourse analysis approach also highlights how the depiction of normative masculinity also reinforces it as an idealized norm in dominant discourse. |

| Representation of Iranian family lifestyle in TV advertising (Labafi, Momeni & Mohammadi, 2021); | Another common theme in discourse analyses of advertising is that of consumerism. By virtue of their economic imperative, the advertisements reinforce consumption as the . While this may seem normal, these studies do highlight how the economic worth of a person subsumes other conceptualizations of identity and humanity, such as those of religion, volunteerism, or communitarianism. |

| Education on the rails: a textual of university advertising in mobile contexts (Symes & Drew, 2017) | In the context of university advertisements, education is often framed as a product rather than a right for citizens. |

11. Analyzing Lesson Plans

As written texts, lesson plans can be analyzed for how they construct discourses around education as well as student and teacher identities. These texts tend to examine how teachers and governing bodies in education prioritize certain ideologies around what and how to learn. These texts can enter into discussions around the ‘history wars’ (what and whose history should be taught) as well as ideological approaches to religious and language learning.

| Uncovering the Ideologies of Internationalization in Lesson Plans through Critical Discourse Analysis (Hahn, 2018) | Japanese lesson plans appear to be implicitly integrating the language of internationalization that has been pushed by government policies over a number of years, despite rare explicit mention. This shows how the discourse of education is systemically changing in Japan. |

| Exploring Canadian Integration through Critical Discourse Analysis of English Language Lesson Plans for Immigrant Learners (Barker, 2021) | This study explores English language lesson plans for immigrants to Canada, showing how the lesson plans tend to encourage learners to assimilate to Canadian language norms which may, in turn, encourage them to abandon or dilute ways of speaking that more effectively reflect their personal sense of self. |

12. Looking at Graffiti

One of my favorite creative uses of discourse analysis is in the study of graffiti. By looking at graffiti, researchers can identify how youth countercultures and counter discourses are spread through subversive means. These counterdiscourses offer ruptures where dominant discourses can be unsettled and displaced.

| An exploration of graffiti on university’s walls: A corpus-based discourse analysis study (Al-Khawaldeh et al, 2017) | The study shows how graffiti is a site for conversations around important issues to youths, including taboo topics, religion, and national identity. |

| Graffiti slogans and the construction of collective identity: evidence from the anti-austerity protests in Greece (Serafis, Kitis & Argiris, 2018) | This study from Greece shows how graffiti can be used in protest movements in ways that attempt to destabilize dominant economic narratives . |

Get a Pdf of this article for class

Enjoy subscriber-only access to this article’s pdf

The Origins of Discourse Analysis

1. foucault.

French philosopher Michel Foucault is a central thinker who shaped discourse analysis. His work in studies like Madness and Civilization and The History of Sexuality demonstrate how our ideas about insanity and sexuality have been shaped through language.

The ways the church speaks about sex, for example, shapes people’s thoughts and feelings about it.

The church didn’t simply make sex a silent taboo. Rather, it actively worked to teach people that desire was a thing of evil, forcing them to suppress their desires.

Over time, society at large developed a suppressed normative approach to the concept of sex that is not necessarily normal except for the fact that the church reiterates that this is the only acceptable way of thinking about the topic.

Similarly, in Madness and Civilization , a discourse around insanity was examined. Medical discourse pathologized behaviors that were ‘abnormal’ as signs of insanity. Were the dominant medical discourse to change, it’s possible that abnormal people would no longer be seen as insane.

One clear example of this is homosexuality. Up until the 1990s, being gay was seen in medical discourse as an illness. Today, most of Western society sees that this way of looking at homosexuality was extremely damaging and exclusionary, and yet at the time, because it was the dominant discourse, people didn’t question it.

2. Norman Fairclough

Fairclough (2013), inspired by Foucault, created some key methodological frameworks for conducting discourse analysis.

Fairclough was one of the first scholars to articulate some frameworks around exploring ‘text as discourse’ and provided key tools for scholars to conduct analyses of newspaper and policy texts.

Today, most methodology chapters in dissertations that use discourse analysis will have extensive discussions of Fairclough’s methods.

Discourse analysis is a popular primary research method in media studies, cultural studies, education studies, and communication studies. It helps scholars to show how texts and language have the power to shape people’s perceptions of reality and, over time, shift dominant ways of framing thought. It also helps us to see how power flows thought texts, creating ‘in-groups’ and ‘out-groups’ in society.

Key examples of discourse analysis include the study of television, film, newspaper, advertising, political speeches, and interviews.

Al Kharusi, R. (2017). Ideologies of Arab media and politics: a CDA of Al Jazeera debates on the Yemeni revolution. PhD Dissertation: University of Hertfordshire.

Alaazi, D. A., Ahola, A. N., Okeke-Ihejirika, P., Yohani, S., Vallianatos, H., & Salami, B. (2021). Immigrants and the Western media: a CDA of newspaper framings of African immigrant parenting in Canada. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 47 (19), 4478-4496. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1798746

Al-Khawaldeh, N. N., Khawaldeh, I., Bani-Khair, B., & Al-Khawaldeh, A. (2017). An exploration of graffiti on university’s walls: A corpus-based discourse analysis study. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics , 7 (1), 29-42. Doi: https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v7i1.6856

Alsaraireh, M. Y., Singh, M. K. S., & Hajimia, H. (2020). Critical DA of gender representation of male and female characters in the animation movie, Frozen. Linguistica Antverpiensia , 104-121.

Baig, F. Z., Khan, K., & Aslam, M. J. (2021). Child Rearing and Gender Socialisation: A Feminist CDA of Kids’ Popular Fictional Movies. Journal of Educational Research and Social Sciences Review (JERSSR) , 1 (3), 36-46.

Barker, M. E. (2021). Exploring Canadian Integration through CDA of English Language Lesson Plans for Immigrant Learners. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics/Revue canadienne de linguistique appliquée , 24 (1), 75-91. Doi: https://doi.org/10.37213/cjal.2021.28959

Coleman, B. (2017). An Ideological Unveiling: Using Critical Narrative and Discourse Analysis to Examine Discursive White Teacher Identity. AERA Online Paper Repository .

Drew, C. (2013). Soak up the goodness: Discourses of Australian childhoods on television advertisements, 2006-2012. PhD Dissertation: Australian Catholic University. Doi: https://doi.org/10.4226/66/5a9780223babd

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language . London: Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1990). The history of sexuality: An introduction . London: Vintage.

Foucault, M. (2003). Madness and civilization . New York: Routledge.

Hahn, A. D. (2018). Uncovering the ideologies of internationalization in lesson plans through CDA. The New English Teacher , 12 (1), 121-121.

Isti’anah, A. (2018). Rohingya in media: CDA of Myanmar and Bangladesh newspaper headlines. Language in the Online and Offline World , 6 , 18-23. Doi: http://repository.usd.ac.id/id/eprint/25962

Khan, M. H., Adnan, H. M., Kaur, S., Qazalbash, F., & Ismail, I. N. (2020). A CDA of anti-Muslim rhetoric in Donald Trump’s historic 2016 AIPAC policy speech. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs , 40 (4), 543-558. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13602004.2020.1828507

Louise Cooper, K., Luck, L., Chang, E., & Dixon, K. (2021). What is the practice of spiritual care? A CDA of registered nurses’ understanding of spirituality. Nursing Inquiry , 28 (2), e12385. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12385

Mohammadi, D., Momeni, S., & Labafi, S. (2021). Representation of Iranians family’s life style in TV advertising (Case study: food ads). Religion & Communication , 27 (58), 333-379.

Munro, M. (2018) House price inflation in the news: a CDA of newspaper coverage in the UK. Housing Studies, 33(7), pp. 1085-1105. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2017.1421911

Ravn, I. M., Frederiksen, K., & Beedholm, K. (2016). The chronic responsibility: a CDA of Danish chronic care policies. Qualitative Health Research , 26 (4), 545-554. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1049732315570133

Sengul, K. (2019). Critical discourse analysis in political communication research: a case study of right-wing populist discourse in Australia. Communication Research and Practice , 5 (4), 376-392. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2019.1695082

Serafis, D., Kitis, E. D., & Archakis, A. (2018). Graffiti slogans and the construction of collective identity: evidence from the anti-austerity protests in Greece. Text & Talk , 38 (6), 775-797. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2018-0023

Suphaborwornrat, W., & Punkasirikul, P. (2022). A Multimodal CDA of Online Soft Drink Advertisements. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network , 15 (1), 627-653.

Symes, C., & Drew, C. (2017). Education on the rails: a textual ethnography of university advertising in mobile contexts. Critical Studies in Education , 58 (2), 205-223. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1252783

Thomas, S. (2005). The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: A critical discourse analysis. Critical Studies in Education , 46 (2), 25-44. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17508480509556423

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Self-Actualization Examples (Maslow's Hierarchy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Forest Schools Philosophy & Curriculum, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori's 4 Planes of Development, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori vs Reggio Emilia vs Steiner-Waldorf vs Froebel

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Critical Discourse Analysis | Definition, Guide & Examples

Critical Discourse Analysis | Definition, Guide & Examples

Published on August 23, 2019 by Amy Luo . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Critical discourse analysis (or discourse analysis) is a research method for studying written or spoken language in relation to its social context. It aims to understand how language is used in real life situations.

When you conduct discourse analysis, you might focus on:

- The purposes and effects of different types of language

- Cultural rules and conventions in communication

- How values, beliefs and assumptions are communicated

- How language use relates to its social, political and historical context

Discourse analysis is a common qualitative research method in many humanities and social science disciplines, including linguistics, sociology, anthropology, psychology and cultural studies.

Table of contents

What is discourse analysis used for, how is discourse analysis different from other methods, how to conduct discourse analysis, other interesting articles.

Conducting discourse analysis means examining how language functions and how meaning is created in different social contexts. It can be applied to any instance of written or oral language, as well as non-verbal aspects of communication such as tone and gestures.

Materials that are suitable for discourse analysis include:

- Books, newspapers and periodicals

- Marketing material, such as brochures and advertisements

- Business and government documents

- Websites, forums, social media posts and comments

- Interviews and conversations

By analyzing these types of discourse, researchers aim to gain an understanding of social groups and how they communicate.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Unlike linguistic approaches that focus only on the rules of language use, discourse analysis emphasizes the contextual meaning of language.

It focuses on the social aspects of communication and the ways people use language to achieve specific effects (e.g. to build trust, to create doubt, to evoke emotions, or to manage conflict).

Instead of focusing on smaller units of language, such as sounds, words or phrases, discourse analysis is used to study larger chunks of language, such as entire conversations, texts, or collections of texts. The selected sources can be analyzed on multiple levels.

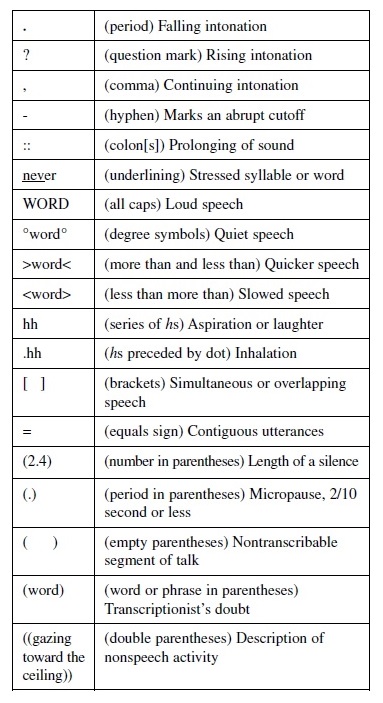

| Level of communication | What is analyzed? |

|---|---|

| Vocabulary | Words and phrases can be analyzed for ideological associations, formality, and euphemistic and metaphorical content. |

| Grammar | The way that sentences are constructed (e.g., , active or passive construction, and the use of imperatives and questions) can reveal aspects of intended meaning. |

| Structure | The structure of a text can be analyzed for how it creates emphasis or builds a narrative. |

| Genre | Texts can be analyzed in relation to the conventions and communicative aims of their genre (e.g., political speeches or tabloid newspaper articles). |

| Non-verbal communication | Non-verbal aspects of speech, such as tone of voice, pauses, gestures, and sounds like “um”, can reveal aspects of a speaker’s intentions, attitudes, and emotions. |

| Conversational codes | The interaction between people in a conversation, such as turn-taking, interruptions and listener response, can reveal aspects of cultural conventions and social roles. |

Discourse analysis is a qualitative and interpretive method of analyzing texts (in contrast to more systematic methods like content analysis ). You make interpretations based on both the details of the material itself and on contextual knowledge.

There are many different approaches and techniques you can use to conduct discourse analysis, but the steps below outline the basic structure you need to follow. Following these steps can help you avoid pitfalls of confirmation bias that can cloud your analysis.

Step 1: Define the research question and select the content of analysis

To do discourse analysis, you begin with a clearly defined research question . Once you have developed your question, select a range of material that is appropriate to answer it.

Discourse analysis is a method that can be applied both to large volumes of material and to smaller samples, depending on the aims and timescale of your research.

Step 2: Gather information and theory on the context

Next, you must establish the social and historical context in which the material was produced and intended to be received. Gather factual details of when and where the content was created, who the author is, who published it, and whom it was disseminated to.

As well as understanding the real-life context of the discourse, you can also conduct a literature review on the topic and construct a theoretical framework to guide your analysis.

Step 3: Analyze the content for themes and patterns

This step involves closely examining various elements of the material – such as words, sentences, paragraphs, and overall structure – and relating them to attributes, themes, and patterns relevant to your research question.

Step 4: Review your results and draw conclusions

Once you have assigned particular attributes to elements of the material, reflect on your results to examine the function and meaning of the language used. Here, you will consider your analysis in relation to the broader context that you established earlier to draw conclusions that answer your research question.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Luo, A. (2023, June 22). Critical Discourse Analysis | Definition, Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/discourse-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

What is qualitative research | methods & examples, what is a case study | definition, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 March 2021

Research impact evaluation and academic discourse

- Marta Natalia Wróblewska ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8575-5215 1 , 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 58 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

5297 Accesses

12 Citations

40 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

- Science, technology and society

The introduction of ‘impact’ as an element of assessment constitutes a major change in the construction of research evaluation systems. While various protocols of impact evaluation exist, the most articulated one was implemented as part of the British Research Excellence Framework (REF). This paper investigates the nature and consequences of the rise of ‘research impact’ as an element of academic evaluation from the perspective of discourse. Drawing from linguistic pragmatics and Foucauldian discourse analysis, the study discusses shifts related to the so-called Impact Agenda on four stages, in chronological order: (1) the ‘problematization’ of the notion of ‘impact’, (2) the establishment of an ‘impact infrastructure’, (3) the consolidation of a new genre of writing–impact case study, and (4) academics’ positioning practices towards the notion of ‘impact’, theorized here as the triggering of new practices of ‘subjectivation’ of the academic self. The description of the basic functioning of the ‘discourse of impact’ is based on the analysis of two corpora: case studies submitted by a selected group of academics (linguists) to REF2014 (no = 78) and interviews ( n = 25) with their authors. Linguistic pragmatics is particularly useful in analyzing linguistic aspects of the data, while Foucault’s theory helps draw together findings from two datasets in a broader analysis based on a governmentality framework. This approach allows for more general conclusions on the practices of governing (academic) subjects within evaluation contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research

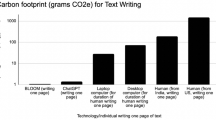

The carbon emissions of writing and illustrating are lower for AI than for humans

Introduction.

The introduction of ‘research impact’ as an element of evaluation constitutes a major change in the construction of research evaluation systems. ‘Impact’, understood broadly as the influence of academic research beyond the academic sphere, including areas such as business, education, public health, policy, public debate, culture etc., has been progressively implemented in various systems of science evaluation—a trend observable worldwide (Donovan, 2011 ; Grant et al., 2009 ; European Science Foundation, 2012 ). Salient examples of attempts to systematically evaluate research impact include the Australian Research Quality Framework–RQF (Donovan, 2008 ) and the Dutch Standard Evaluation Protocol (VSNU–Association of Universities in the Netherlands, 2016 , see ‘societal relevance’).

The most articulated system of impact evaluation to date was implemented in the British cyclical ex post assessment of academic units, Research Excellence Framework (REF), as part of a broader governmental policy—the Impact Agenda. REF is the most-studied and probably the most influential impact evaluation system to date. It has been used as a model for analogous evaluations in other countries. These include the Norwegian Humeval exercise for the humanities (Research Council of Norway, 2017 , pp. 36–37, Wróblewska, 2019 ) and ensuing evaluations of other fields (Research Council of Norway, 2018 , pp. 32–34; Wróblewska, 2019 , pp. 12–16). REF has also directly inspired impact evaluation protocols in Hong-Kong (Hong Kong University Grants Committee, 2018 ) and Poland (Wróblewska, 2017 ). This study is based on data collected in the context of the British REF2014 but it advances a description of the ‘discourse of impact’ that can be generalized and applied to other national and international contexts.

Although impact evaluation is a new practice, a body of literature has been produced on the topic. This includes policy documents on the first edition of REF in 2014 (HEFCE, 2015 ; Stern, 2016 ) and related reports, be it commissioned (King’s College London and Digital Science, 2015 ; Manville et al., 2014 , 2015 ) or conducted independently (National co-ordinating center for public engagement, 2014 ). There also exists a scholarly literature which reflects on the theoretical underpinnings of impact evaluations (Gunn and Mintrom, 2016 , 2018 ; Watermeyer, 2012 , 2016 ) and the observable consequences of the exercise for academic practice (Chubb and Watermeyer, 2017 ; Chubb et al., 2016 ; Watermeyer, 2014 ). While these reports and studies mainly draw on the methods of philosophy, sociology and management, many of them also allude to changes related to language .

Several publications on impact drew attention to the process of meaning-making around the notion of ‘impact’ in the early stages of its existence. Manville et al. flagged up the necessity for the policy-maker to facilitate the development of common vocabulary to enable a broader ‘cultural shift’ (2015, pp. 16, 26. 37–38, 69). Power wrote of an emerging ‘performance discourse of impact’ (2015, p. 44) while Derrick ( 2018 ) looked at the collective process of defining and delimiting “the ambiguous object” of impact at the stage of panel proceedings. The present paper picks up these observations bringing them together in a unique discursive perspective.

Drawing from linguistic pragmatics and Foucauldian discourse analysis, the paper presents shifts related to the introduction of ‘impact’ as element of evaluation in four stages. These are, in chronological order: (1) the ‘problematisation’ of the notion of ‘impact’ in policy and its appropriation on a local level, (2) the creation of an impact infrastructure to orchestrate practices around impact, (3) the consolidation of a new genre of writing—impact case study, (4) academics’ uptake of the notion of impact and its progressive inclusion in their professional positioning.

Each of these stages is described using theoretical concepts grounded in empirical data. The first stage has to do with the process of ‘problematization’ of a previously non-regulated area, i.e., the process of casting research impact as a ‘problem’ to be addressed and regulated by a set of policy measures. The second stage took place when in rapid response to government policy, new procedures and practices were created within universities, giving rise to an impact ‘infrastructure’ (or ‘apparatus’ in the Foucauldian sense). The third stage is the emergence of a crucial element of the infrastructure—a new genre of academic writing—impact case study. I argue that engaging with the new genre and learning to write impact case studies was key in incorporating ‘impact’ into scholars’ narratives of ‘academic identity’. Hence, the paper presents new practices of ‘subjectivation’ as the fourth stage of incorporation of ‘impact’ into academic discourse. The four stages of the introduction of ‘impact’ into academic discourse are mutually interlinked—each step paves the way for the next.

Of the described four stages, only stage three focuses a classical linguistic task: the description of a new genre of text. The remaining three take a broader view informed by sociology and philosophy, focusing on discursive practices i.e., language used in social context. Other descriptions of the emergence of impact are possible—note for instance Power’s four-fold structure (Power, 2015 ), at points analogous to this study.

Theoretical framework and data

This study builds on a constructivist approach to social phenomena in assuming that language plays a crucial role in establishing and maintaining social practice. In this approach ‘discourse’ is understood as the production of social meaning—or the negotiation of social, political or cultural order—through the means of text and talk (Fairclough, 1989 , 1992 ; Fairclough et al., 1997 ; Gee, 2015 ).

Linguistic pragmatics and Foucauldian approaches to discourse are used to account for the changes related to the rise of ‘impact’ as element of evaluation and discourse on the macro and micro scale. In looking at the micro scale of every-day linguistic practices the analysis makes use of linguistic pragmatics, in particular concepts of positioning (Davies and Harré, 1990 ), stage (Goffman, 1969 ; Robinson, 2013 ), metaphor (Cameron, et al., 2009 ; Musolff, 2004 , 2012 ), as well as genre analysis (Swales, 1990 , 2011 ). Analyzing the macro scale, i.e., the establishment of the concept of ‘impact’ in policy and the creation of an impact infrastructure, it draws on selected concepts of Fouculadian governmentality theory (crucially ‘problematisation’, ‘apparatus’, ‘subjectivation’) (Foucault, 1980 , 1988 , 1990 ; Rose, 1999 , pp. ix–xiii).

While the toolbox of linguistic pragmatics is particularly useful in analyzing linguistic aspects of the datasets, Foucault’s governmental framework helps bring together findings from the two datasets in a broader analysis, allowing more general conclusions on the practices of governing (academic) subjects within evaluation frameworks. Both pragmatic and Foucauldian traditions of discourse analysis have been productively applied in the study of higher education contexts (e.g., Fairclough, 1993 , Gilbert and Mulkey, 1984 , Hyland, 2009 , Myers, 1985 , 1989 ; for an overview see Wróblewska and Angermuller, 2017 ).

The analysis builds on an admittedly heterogenous set of concepts, hailing from different traditions and disciplines. This approach allows for a suitably nuanced description of a broad phenomenon—the discourse of impact—studied here on the basis of two different datasets. To facilitate following the argument, individual theoretical and methodological concepts are defined where they are applied in the analysis.

The studied corpus consists of two datasets: a written and oral one. The written corpus includes 78 impact case studies (CSs) submitted to REF2014 in the discipline of linguistics Footnote 1 . Linguistics was selected as a discipline straddling the social sciences and humanities (SSH). SSH are arguably most challenged by the practice of impact evaluation as they have traditionally resisted subjection to economization and social accountability (Benneworth et al., 2016 ; Bulaitis, 2017 ).

The CSs were downloaded in pdf form from REF’s website: https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/ . The documents have an identical structure, featuring basic information: name of institution, unit of assessment, title of CS and core content divided into five sections: (1) summary of impact, (2) underpinning research, (3) references to the research, (4) details of impact (5) sources to corroborate impact. Each CS is about 4 pages long (~2400 words). The written dataset (with a word-count of 173,474) was analyzed qualitatively using MAX QDA software with a focus on the generic aspect of the documents.

The oral dataset is composed of semi-structured interviews with authors of the studied CSs ( n = 20) and other actors involved in the evaluation, including two policy-makers and three academic administrators Footnote 2 . In total, the 25 interviews, each around 60 min long, add up to around 25 h of recordings. The interviews were analyzed in two ways. Firstly, they were coded for themes and topics related to the evaluation process—this was useful for the description of impact infrastructure presented in step 2 of analysis. Secondly, they were considered as a linguistic performance and coded for discursive devices (irony, distancing, metaphor etc.)—this was the basis for findings related to the presentation of one’s ‘academic self’ which are the object of fourth step of analysis. The written corpus allows for an analysis of the functioning of the notion of ‘impact’ in the official, administrative discourse of academia, looking at the emergence of an impact infrastructure and the genre created for the description of impact. The oral dataset in turn sheds light on how academics relate to the notion of impact in informal settings, by focusing on metaphors and pragmatic markers of stage.

The discourse of impact

Problematization of impact.

The introduction of ‘impact’, a new element of evaluation accounting for 20% of the final result, was seen as a surprise and as a significant change in respect to the previous model of evaluation—the Research Assessment Exercise (Warner, 2015 ). The outline of an approach to impact evaluation in REF was developed on the government’s recommendation after a review of international practice in impact assessment (Grant et al., 2009 ). The adopted approach was inspired by the previously-created (but never implemented) Australian RQF framework (Donovan, 2008 ). A pilot evaluation exercise run in 2010 confirmed the viability of the case-study approach to impact evaluation. In July 2011 the Higher Education Council for England (HEFCE) published guidelines regulating the new assessment (HEFCE, 2011 ). The deadline for submissions was set for November 2013.

In the period between July 2011 and November 2013 HEFCE engaged in broad communication and training activities across universities, with the aim of explaining the concept of ‘impact’ and the rules which would govern its evaluation (Power, 2015 , pp. 43–48). Knowledge on the new element of evaluation was articulated and passed down to particular departments, academic administrative staff and individual researchers in a trickle-down process, as explained by a HEFCE policymaker in an account of the run-up to REF2014:

There was no master blue print! There were some ideas, which indeed largely came to pass. But in order to understand where we [HEFCE] might be doing things that were unhelpful and might have adverse outcomes, we had to listen. I was in way over one hundred meetings and talked to thousands of people! (…) [The Impact Agenda] is something that we are doing to universities. Actually, what we wanted to say is: ‘we are doing it with you, you’ve Footnote 3 got to own it’.

Int20, policymaker, example 1 Footnote 4

Due to the importance attributed to the exercise by managers of academic units and the relatively short time for preparing submissions, institutions were responsive to the policy developments. In fact, they actively contributed to the establishment and refinement of concepts related to impact. Institutional learning occurred to a large degree contemporarily to the consolidation of the policy and the refinement of the concepts and definitions related to impact. The initially open, undefined nature of ‘impact’ (“there was no master blue-print”) is described also in accounts of academics who participated in the many rounds of meetings and consultations. See example 2 below:

At that time, they [HEFCE] had not yet come up with this definition [of impact], not yet pinned it down, but they were trying to give an idea of what it was, to get feedback, to get a grip on it. (…) And we realised (…) they didn’t have any more of an idea of this than we did! It was almost like a fishing expedition. (…) I got a sense very early on of, you know, groping.

Int1, academic, example 2

The “pinning down” of an initially fuzzy concept and defining the rules which would come to govern its evaluation was just one aim of the process. The other one was to engage academics and affirm their active role in the policy-making. From an idea which came from outside of the British academic community (from the the government, the research councils) and originally from outside the UK (the Australian RQF exercise), a concept which was imposed on academics (“it is something that we are doing to universities”) the Impact Agenda was to become an accepted, embedded element of the academic life (“you’ve got to own it”). In this sense, the laboriousness of the process, both for the policy-makers and the academics involved, was a necessary price to be paid for the feeling of “ownership” among the academic community. Attitudes of academics, initially quite negative (Chubb et al., 2016 , Watermeyer, 2016 ), changed progressively, as the concept of impact became familiarized and adapted to the pre-existing realities of academic life, as recounted by many of the interviewees, e.g.,:

I think the resentment died down relatively quickly. There was still some resistance. And that was partly academics recognising that they had to [take part in the exercise], they couldn’t ignore it. Partly, the government and the research council has been willing to tweak, amend and qualify the initial very hard-edged guidelines and adapt them for the humanities. So, it was two-way process, a dialogue.

Int16, academic, example 3

The announcement of the final REF regulations (HEFCE, 2011 ) was the climax of the long process of making ‘impact’ into a thinkable and manageable entity. The last iteration of the regulations constituted a co-creation of various actors (initial Australian policymakers of the RQF, HEFCE employees, academics, impact professionals, universities, professional organizations) who had contributed to it at different stages (in many rounds of consultations, workshops, talks and sessions across the country). ‘Impact’ as a notion was ‘talked into being’ in a polyphonic process (Angermuller, 2014a , 2014b ) of debate, critique, consultation (“listening”, “getting feedback”) and adaptation (“tweaking”, “changing”, “amending hard-edged guidelines”) also in view of the pre-existing conditions of academia such as the friction between the ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ sciences (as mentioned in example 3). In effect, impact was constituted as an object of thought, and an area of academic activity begun to emerge around it.

The period of defining ‘impact’ as a new, important notion in academic discourse in the UK, roughly between July 2011 and November 2013, can be conceptualized in terms of the Foucauldian notion of ‘problematization’. This concept describes how spaces, areas of activity, persons, behaviors or practices become targeted by government, separated from others, and cast as ‘problems’ to be addressed with a set of techniques and regulations. ‘Problematisation’ is the moment when a notion “enters into the play of true and false, (…) is constituted as an object of thought (whether in the form of moral reflection, scientific knowledge, political analysis, etc.)” (Foucault, 1988 , p. 257), when it “enters into the field of meaning” (Foucault, 1984 , pp. 84–86). The problematization of an area triggers not only the establishment of new notions and objects but also of new practices and institutions. In consequence, the areas in question become subjugated to a new (political, administrative, financial) domination. This eventually shapes the way in which social subjects conceive of their world and of themselves. But a ‘problematisation’, however influential, cannot persist on its own. It requires an overarching structure in the form of an ‘apparatus’ which will consolidate and perpetuate it.

Impact infrastructure

Soon after the publication of the evaluation guidelines for REF2014, and still during the phase of ‘problematisation’ of impact, universities started collecting data on ‘impactful’ research conducted in their departments and recruiting authors of potential CSs which could be submitted for evaluation. The winding and iterative nature of the process of problematization of ‘impact’ made it difficult for research managers and researchers to keep track of the emerging knowledge around impact (official HEFCE documentation, results of the pilot evaluation, FAQs, workshops and sessions organized around the country, writings published in paper and online). At the stage of collecting drafts of CSs it was still unclear what would ‘count’ as impact and what evidence would be required. Hence, there emerged a need for specific procedures and specialized staff who would prepare the REF submissions.

At most institutions, specific posts were created for employees preparing impact submissions for REF2014. These were both secondment positions such as ‘impact lead’, ‘impact champion’ and full-time ones such as impact officer, impact manager. These professionals soon started organizing between themselves at meetings and workshops. Administrative units focused on impact (such as centers for impact and engagement, offices for impact and innovation) were created at many institutions. A body of knowledge on impact evaluation was soon consolidated, along with a specific vocabulary (‘a REF-able piece of research’, ‘pathways to impact’, ‘REF-readiness’ etc.) and sets of resources. Impact evaluation gave raise to the creation of a new type of specialized university employee, who in turn contributed to turning the ‘generation of impact’, as well as the collection and presentation of related data into a veritable field of professional expertize.

In order to ensure timely delivery of CSs to REF2014, institutions established fixed procedures related to the new practice of impact evaluation (periodic monitoring of impact, reporting on impact-related activities), frames (schedules, document templates), forms of knowledge transfer (workshops on impact generation or on writing in the CS genre), data systems and repositories for logging and storing impact-related data, and finally awards and grants for those with achievements (or potential) related to impact. Consultancy companies started offering commercial services focused on research impact, catering to universities and university departments but also to governments and research councils outside the UK looking at solutions for impact evaluation. There is even an online portal with a specific focus on showcasing researchers’ impact (Impact Story).

In consequence, impact became institutionalized as yet another “box to be ticked” on the list of academic achievements, another component of “academic excellence”. Alongside burdens connected to reporting on impact and following regulations in the area, there came also rewards. The rise of impact as a new (or newly-problematised) area of academic life opened up uncharted areas to be explored and opportunities for those who wished to prove themselves. These included jobs for those who had acquired (or could claim) expertize in the area of impact (Donovan, 2017 , p. 3) and research avenues for those studying higher education and evaluation (after all, entirely new evaluation practices rarely emerge, as stressed by Power, 2015 , p. 43). While much writing on the Impact Agenda highlights negative attitudes towards the exercise (Chubb et al., 2016 ; Sayer, 2015 ), equally worth noting are the opportunities that the establishment of a new element of the exercise opened. It is the energy of all those who engage with the concept (even in a critical way) that contributes to making it visible, real and robust.

The establishment of a specialized vocabulary, of formalized requirements and procedures, the creation of dedicated impact-related positions and departments, etc. contribute to the establishment of what can be described as an ‘impact infrastructure’ (comp. Power, 2015 , p. 50) or in terms of Foucauldian governmentality theory as an ‘apparatus’ Footnote 5 . In Foucault’s terminology, ‘apparatus’ refers to a formation which encompasses the entirety of organizing practices (rituals, mechanisms, technologies) but also assumptions, expectations and values. It is the system of relations established between discursive and non-discursive elements as diverse as “institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions” (Foucault, 1980 , p. 194). An apparatus servers a specific strategic function—responding to an urgent need which arises in a concrete time in history—for instance, regulating the behavior of a population.

There is a crucial discursive element to all the elements of the ‘impact apparatus’. While the creation of organizational units and jobs, the establishment of procedures and regulations, participation in meetings and workshops are no doubt ‘hard facts’ of academic life, they are nevertheless brought about and made real in discursive acts of naming, defining, delimiting and evaluating. The aim of the apparatus was to support the newly-established problematization of impact. It did so by operating on many levels: first of all, and most visibly, newly-established procedures enabled a timely and organized submission to the upcoming REF. Secondly, the apparatus guided the behavior of social actors. It did so not only through directive methods (enforcing impact-related requirements) but also through nurturing attitudes and dispositions which are necessary for the notion of impact to take root in academia (for instance via impact training delivered to early-career scholars).

Interviewed actors involved in implementing the policy in institutions recognized their role in orchestrating collective learning. An interviewed impact officer stated:

My feeling is that ultimately my post should not exist. In ten or fifteen years’ time, impact officers should have embedded the message [about impact] firmly enough that they [researchers] don’t need us anymore.

Int7, impact officer, example 4

A similar vision was evoked by a HEFCE policymaker who was asked if the notion of impact had become embedded in academic institutions:

I hope [after the next edition of REF] we will be able to say that it has become embedded. I think the question then will be “have we done enough in terms of case studies? Do we need something very much lighter-touch?” “Do we need anything at all?”—that’s a question. (…) If [impact] is embedded you don’t need to talk about it.

Int20, policy-maker, example 5

Rather than being an aim in itself, the Impact Agenda is a means of altering academic culture so that institutions and individual researchers become more mindful of the societal impacts of their research. The instillment of a “new impact culture” (see Manville et al., 2014 , pp. 24–29) would ensure that academic subjects consider the question of ‘impact’ even outside of the framework of REF. The “culture shift” is to occur not just within institutions but ultimately within the subjects—it is in them that the notion of ‘impact’ has to become embedded. Hence, the final purpose of the apparatus would be to obscure the origins of the notion of ‘impact’ and the related practices, neutralizing the notion itself, and giving a guise of necessity to an evaluative reality which in fact is new and contingent.

The genre of impact case study as element of infrastructure

In this section two questions are addressed: (1) what are the features of the genre (or what is it like?) and (2) what are the functions of the genre (or what does it do? what vision of research does it instil?). In addressing the first question, I look at narrative patterns, as well as lexical and grammatical features of the genre. This part of the study draws on classical genre analysis (Bhatia, 1993 ; Swales, 1998 ) Footnote 6 . The second question builds on the recognition, present in discourse studies since the 1970s’, that genres are not merely classes of texts with similar properties, but also veritable ‘dispositives of communication’. A genre is a means of articulation of legitimate speech; it does not just represent facts or reflect ideologies, it also acts on and alters the context in which it operates (Maingueneau, 2010 , pp. 6–7). This awareness has engendered broader sociological approaches to genre which include their pragmatic functioning in institutional realities (Swales, 1998 ).

The genre of CS differs from other academic genres in that it did not emerge organically, but was established with a set of guidelines and a document template at a precise moment in time. The genre is partly reproductive, as it recycles existing patterns of academic texts, such as journal article, grant application, annual review, as well as case study templates applied elsewhere. The studied corpus is strikingly uniform, testifying to an established command of the genre amongst submitting authors. Identical expressions are used to describe impact across the corpus. Only very rarely is non-standard vocabulary used (e.g., “horizontal” and “vertical” impact rather then “reach” and “significance” of impact). This coherence can be contrasted with a much more diversified corpus of impact CSs submitted in Norway to an analogous exercise (Wróblewska, 2019 ). The rapid consolidation of the genre in British academia can be attributed to the perceived importance of impact evaluation exercise, which lead to the establishment of an impact infrastructure, with dedicated employees tasked with instilling the ‘culture of impact’.

In its nature, the CS is a performative, persuasive genre—its purpose is to convince the ‘ideal readers’ (the evaluators) of the quality of the underpinning research and the ‘breadth and significance’ of the described impact. The main characteristics of the genre stem directly from its persuasive aim. These are discussed below in terms of narrative patterns, and grammatical and lexical features.

Narrative patterns

On the level of narrative, there is an observable reliance on a generic pattern of story-telling frequent in fiction genres, such as myths or legends, namely the Situation-Problem–Response–Evaluation (SPRE) structure (also known as the Problem-Solution pattern, see Hoey, 1994 , 2001 pp. 123–124). This is a well-known narrative which follows the SPRE pattern: a mountain ruled by a dragon (situation) which threats the neighboring town (problem) is sieged by a group of heroes (response), to lead to a happy ending or a new adventure (evaluation). Compare this to an example of the SPRE pattern in a sample impact narrative from the studied corpus:

Mosetén is an endangered language spoken by approximately 800 indigenous people (…) (SITUATION). Many Mosetén children only learn the majority language, Spanish (PROBLEM). Research at [University] has resulted in the development of language materials for the Mosetenes. (…) (RESPONSE). It has therefore had a direct influence in avoiding linguistic and cultural loss. (EVALUATION).

CS40828 Footnote 7

The SPRE pattern is complemented by patterns of Further Impact and Further Corroboration. The first one allows elaborating the narrative, e.g., by showing additional (positive) outcomes, so that the impact is not presented as an isolated event, but rather as the beginning of a series of collaborations, e.g.,:

The research was published in [outlet] (…). This led to an invitation from the United Nations Environment Programme for [researcher](FURTHER IMPACT).

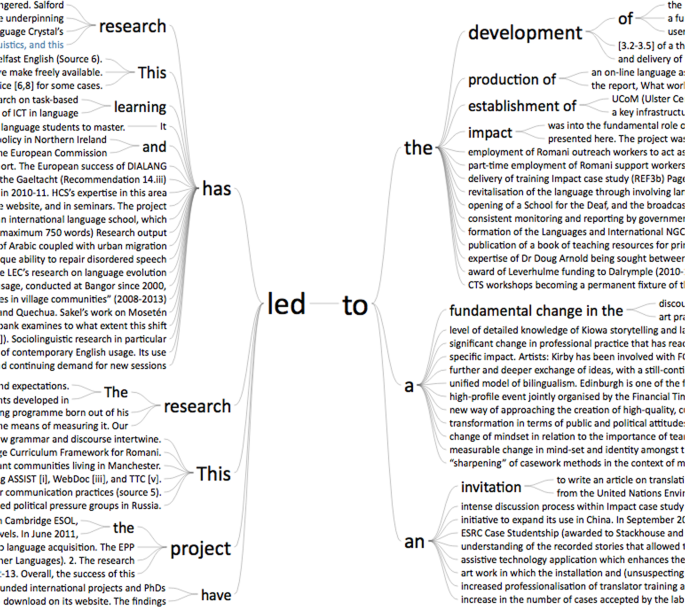

Patterns of ‘further impact’ are often built around linking words, such as: “X led to” ( n = 78) Footnote 8 , “as a result” ( n in the corpus =31), “leading to” ( n = 24), “resulting in” ( n = 13), “followed” (“X followed Y”– n = 14). Figure 1 below shows a ‘word tree’ for a frequent linking structure “led to”. The size of the terms in the diagram represents frequencies of terms in the corpus. Reading the word tree from left to right enables following typical sentence structures built around the ‘led to’ phrase: research led to an impact (fundamental change/development/establishment/production of…); impact “led to” further impact.

Word tree with string ‘led to'. This word tree with string ‘led to’ was prepared with MaxQDA software. It visualises a frequent sentence structure where research led to impact (fundamental change/ development/ establishment/ production of…) or otherwise how impact “led to” further impact.

The ‘Further Corroboration’ pattern provides additional information which strengthens the previously provided corroborative material:

(T)he book has been used on the (…) course rated outstanding by Ofsted, at the University [Name](FURTHER CORROBORATION).

Grammatical and lexical features

Both on a grammatical and lexical level, there is a visible focus on numbers and size. In making the point on the breadth and significance of impact, CS authors frequently showcase (high) numbers related to the research audience (numbers of copies sold, audience sizes, downloads but also, increasingly, tweets, likes, Facebook friends and followers). Adjectives used in the CSs appear frequently in the superlative or with modifiers which intensify them: “Professor [name] undertook a major Footnote 9 ESRC funded project”; “[the database] now hosts one of the world’s largest and richest collections (…) of corpora”; “work which meets the highest standards of international lexicographical practice”; “this experience (…) is extremely empowering for local communities”, “Reach: Worldwide and huge ”.

Use of ‘positive words’ constitutes part of the same phenomenon. These appear often in the main narrative on research and impact, and even more frequently in quoted testimonials. Research is described in the CSs as being new, unique and important with the use of words such as “innovative” ( n = 29), “influential” ( n = 16), “outstanding” ( n = 12), “novel” ( n = 10), “excellent” ( n = 8), “ground-breaking” ( n = 7), “tremendous” ( n = 4), “path-breaking” ( n = 2), etc. The same qualities are also rendered descriptively, with the use of words that can be qualified as boosters e.g., “[the research] has enabled a complete rethink of the relationship between [areas]”; “ vitally important [research]”.

Novelty of research is also frequently highlighted with the adjective “first” appearing in the corpus 70 times Footnote 10 . While in itself “first” is not positive or negative, it carries a big charge in the academic world where primacy of discovery is key. Authors often boast about having for the first time produced a type of research—“this was the first handbook of discourse studies written”…, studied a particular area—“This is the first text-oriented discourse analytic study”…, compiled a type of data—“[We] provid[ed] for the first time reliable nationwide data”; “[the] project created the first on-line database of…”, or proven a thesis: “this research was the first to show that”…

Another striking lexical characteristic of the CSs is the presence of fixed expressions in the narrative on research impact. I refer to these as ‘impact speak’. There are several collocations with ‘impact’, the most frequent being “impact on” ( n = 103) followed by the ‘type’ of impact achieved (impact on knowledge), area/topic (impact on curricula) or audience (Impact on Professional Interpreters). This collocation often includes qualifiers of impact such as “significant”, “wide”, “primary”,“secondary”, “broader”, “key”, and boosters: great, positive, wide, notable, substantial, worldwide, major, fundamental, immense etc. Impact featured in the corpus also as a transitive verb ( n = 22) in the forms “impacted” and “impacting”—e.g., “[research] has (…) impacted on public values and discourse”. This is interesting, as use of ‘impact’ as a verb is still often considered colloquial. Verb collocations with ‘impact’ are connected to achieving influence (“lead to..”, “maximize…”, “deliver impact”) and proving the existence and quality of impact (“to claim”, “to corroborate” impact, “to vouch for” impact, “to confirm” impact, to “give evidence” for impact). Another salient collocation is “pathways to impact” ( n = 14), an expression describing channels of interacting with the public, in the corpus occasionally shortened to just “pathways” e.g., “The pathways have been primarily via consultancy”. This phrase has most likely made its way to the genre of CS from the Research Councils UK ‘Pathways to Impact’ format introduced as part of grant applications in 2009 (discontinued in early 2020).

On a syntactic level, CSs are rich in parallel constructions of enumeration, for instance: “ (t)ranslators, lawyers, schools, colleges and the wider public of Welsh speakers are among (…) users [of research]”; “the research has benefited a broad, international user base including endangered language speakers and community members, language activists, poets and others ”; [the users of the research come] “from various countries including India, Turkey, China, South Korea, Venezuela, Uzbekistan, and Japan ”. Listing, alongside providing figures, is one of the standard ways of signaling the breadth and significance of impact. Both lists and superlatives support the persuasive function of the genre. In terms of verbal forms, passive verbs are clearly favored and personal pronouns (“I, we”) are avoided: “research was conducted”, “advice was provided”, “contracts were undertaken”.

Vision of research promoted by the genre of CS

Impact CS is a new, influential genre which affects its academic context by celebrating and inviting a particular vision of successful research and impact. It sets a standard for capturing and describing a newly-problematized academic object. This standard will be a point of reference for future authors of CSs. Hence, it is worth taking a look at the vision on research it instills.

The SPRE pattern used in the studied CSs favors a vision of research that is linear: work proceeds from research question to results without interference. The Situation and Problem elements are underplayed in favor of elaborate descriptions of the researchers’ ‘Reactions’ (research and outreach/impact activities) and flattering ‘Evaluations’ (descriptions of effects of the research and data supporting these claims). Most narratives are devoid of challenges (the ‘Problem’ element is underplayed, possible drawbacks and failures in the research process are mentioned sporadically). Furthermore, narratives are clearly goal-oriented: impact is shown as included in the research design from the beginning (e.g., impact is frequently mentioned already in section 2 ‘Underpinning research’, rather than the latter one ‘Details of the impact’). Elements of chance, luck, serendipity in the research process are erased—this is reinforced by the presence of patterns of ‘further proof’ and ‘further corroboration’. As such, the bulk of studied CSs channel a vision of what is referred to in Science Studies as ‘normal’ (deterministic, linear) science (Kuhn, 1970 , pp. 10–42). From a purely literary perspective this makes for rather dull narratives: “fairy-tales of researcher-heroes… but with no dragons to be slain” (Selby, 2016 ).

The few CSs which do discuss obstacles in the research process or in securing impact stand out as strikingly diverse from the rest of the corpus. Paradoxically, while apparently ‘weakening’ the argumentation, they render it more engaging and convincing. This effect has been observed also in in an analogous corpus of Norwegian CSs which tend to problematize the pathway from research to impact to a much higher degree (Wróblewska, 2019 , pp. 34–35).

The lexical and grammatical features of the CSs—the proliferation of ‘positive words’, including superlatives, and the adjective “first”— contribute to an idealization of the research process. The documents channel a vision of academia where there is no place for simply ‘good’ research—all CSs seem based on ‘excellent’ and ‘ground-breaking’ projects. The quality of research underpinning impact is recognized in CSs in a straightforward, simplistic way (quotation numbers, peer reviewed papers, publications in top journals, submission to REF), which contributes to normalizing the view of research quality as easily measurable. Similarly, testimonials related to impact are not all equal. Sources of corroboration cited in CSs were carefully selected to appear prestigious and trustworthy. Testimonials and statements from high-ranking officials (but also ‘celebrities’ such as famous intellectuals or political leaders) were particularly sought-after. The end effect reinforces a solidified vision of a hierarchy of worth and trustworthiness in academia.

The prevalence of impersonal verbal forms suggests an de-personalized vision of the research process (“work was conducted”, “papers were published”, “evidence was given…”), where individual factors such as personal aspirations, constraints or ambitions are effaced. The importance given to numbers contributes to a strengthening of a ‘quantifiable’ idea of impact. This is in line with a trend observed in academic writing in general – the inflation of ‘positive words’ (boosters and superlatives) (Vinkers et al., 2015 ). This tendency is amplified in the genre of CS, particularly in its British iteration. In a Norwegian corpus claims to excellence of research and breadth and significance of impact were significantly more modest (Wróblewska, 2019 , pp. 28–30).

The genre of impact CS is a core binding component of the impact infrastructure: all the remaining elements of this formation are mutually connected by a common aim – the generation of CSs. While the CS genre, together with the encompassing impact infrastructure, is vested with a seductive/coercive force, the subjects whose work it represents and who produce it take different positions in its face.

Academics’ positioning towards the Impact Agenda

Academics position themselves towards the concept of impact in many explicit and implicit ways. ‘Positioning’ is understood here as performance-based claims to identity and subjectivity (Davies and Harré, 1990 , Harré and Van Langenhove, 1998 ). Rejecting the idea of stable “inherent” identities, positioning theorists stress how different roles are invoked and enacted in a continuous game of positioning (oneself) and being positioned (by others). Positioning in academic contexts may take the form of indexing identities such as “professor”, “linguist”, “research manager”, “SSH scholar”, “intellectual”, “maverick” etc. (Angermuller, 2013 ; Baert, 2012 , Hamann, 2016 , Hah, 2019 , 2020 ). Also many daily interactions which do not include explicit identity claims involve subject positioning, as they carry value judgments, thereby also evoking counter-statements and colliding social contexts (Tirado and Galvaz, 2008 , pp. 32–45).

My analysis draws attention to the process of incorporating impact into academic subjectivities. I look firstly at the mechanics of academics’ positioning towards impact: the game of opposite discursive acts of distancing and endorsement. Academics reject the notion of ‘impact’ by ironizing, stage management and use of metaphors. Conversely, they may actively incorporate impact into their presentation of academic ‘self’. This discursive engagement with the notion of impact can be described as ‘subjectivation’, i.e., the process whereby subjects re(establish) themselves in relation to the grid of power/knowledge in which they function (in this case the emergent ‘impact infrastructure’).

The relatively high response rate of this study (~50%) and the visible eagerness of respondents to discuss the question of impact suggest an emotional response of academics to the topic of impact evaluation. Yet, respondents visibly struggled with the notion of ‘impact’, often distancing themselves from it through discursive devices, the most salient being ironizing, use of metaphors and stage management.

Ironizing the notion of impact

In many cases, before proceeding to explain their attitude to impact, interviewed academics elaborated on the notion of impact, explaining how the notion applied to their discipline or field and what it meant for them personally. This often meant rejecting the official definition of impact or redefining the concept. In excerpt 6, the interviewee picks up the notion:

Impact… I don’t even like the word! (…) It sounds [like] a very aggressive word, you know, impact, impact ! I don’t want to imp act ! What you want, and what has happened with [my research] really is… more of a dialogue.

Int21, academic, example 6

Another respondent brought up the notion of impact when discussing ethical challenges arising from public dissemination of research.

When you manage to go through that and navigate successfully, and keep producing research, to be honest, that’s impact for me.

Int9, academic, example 7

An analogous distinction was made by a third respondent who discussed the effect of his work on an area of professional activity. While, as he explained, this application of his research has been a source of personal satisfaction, he refused to describe his work in terms of ‘impact’. He stressed that the type of influence he aims for does not lend itself to producing a CS (is not ‘REF-able’):

That’s not impact in the way this government wants it! Cause I have no evidence. I just changed someone’s view. Is that impact? Yes, for me it is. But it is not impact as understood by the bloody REF.

Int3, academic, example 8

These are but three examples of many in the studied corpus where speakers take up the notion of impact to redefine or nuance it, often juxtaposing it with adjacent notions of public engagement, dissemination, outreach, social responsibility, activism etc. A previous section highlighted how the definition of impact was collectively constructed by a community in a process of problematization. The above-cited examples illustrate the reverse of this phenomenon—namely, how individual social actors actively relate to an existing notion in a process of denying, re-defining, and delimiting.

These opposite tendencies of narrowing down and again widening a definition are in line with the theory of the double role of descriptions in discourse. Definitions are both constructions and constructive —while they are effects of discourse, they can also become ‘building blocks’ for ideas, identities and attitudes (Potter, 1996 , p. 99). By participating in impact-related workshops academics ‘reify’ the existing, official definition by enacting it within the impact infrastructure. Fragments cited above exemplify the opposite strategy of undermining the adequacy of the description or ‘ironizing’ the notion (Ibid, p.107). The tension between reifying and ironizing points to the winding, conflictual nature of the process of accepting and endorsing the new ‘culture of impact’. A recognition of the multiple meanings given to the notion of ‘impact’ by policy-makers, academic managers and scholars may caution us in relation to studies on attitudes towards impact which take the notion at face value.

Respondents nuanced the notion of impact also through the use of metaphors. In discourse analysis metaphors are seen in not just as stylistic devices but as vehicles for attitudes and values (Mussolf, 2004 , 2012 ). Many of the respondents make remarks on the ‘realness’ or ‘seriousness’ of the exercise, emphasizing its conventional, artificial nature. Interviewees admitted that claims made in the CSs tend to be exaggerated. At the same time, they stressed that this was in line with the convention of the genre, the nature of which was clear for authors and panelists alike. The practice of impact evaluation was frequently represented metaphorically as a game. See excerpt 9 below:

To be perfectly honest, I view the REF and all of this sort of regulatory mechanisms as something of a game that everybody has to play. The motivation [to submit to REF] was really: if they are going to make us jump through that hoop, we are clever enough to jump through any hoops that any politician can set.

Int14, academic, example 9

Regarding the relation of the narratives in the CSs to truth see example 10:

[A CS] is creative stuff. Given that this is anonymous, I can say that it’s just creative fiction. I wouldn’t say we [authors of CSs] lie, because we don’t, but we kind of… spin. We try to show a reality which, by some stretch of imagination is there. (It’s) a truth. I’m not lying. Can it be shown in different ways? Yes, it can, and then it would be possibly less. But I choose, for obvious reasons, to say that my external funding is X million, which is a truth.

Int3, academic, example 10

The metaphors of “playing a game”, “jumping through hoops” suggest a competition which one does not enter voluntarily (“everybody has to play it”) while those of “creative fiction”, “spinning”, presenting “ a truth” point to an element of power struggle over defining the rules of the game. Doing well in the exercise can mean outsmarting those who establish the framework (politicians) by “performing” particularly well. This can be achieved by eagerly fulfilling the requirements of the genre of CS, and at the same time maintaining a disengaged position from the “regulatory mechanism” of the impact infrastructure.

Stage management

Academics’ positioning towards impact plays out also through management of ‘stage’ of discursive performance, often taking the form of frontstage and backstage markers (in the sense of Goffman’s dramaturgy–1969, pp. 92–122). For instance, references to the confidential nature of the interview (see example 10 above) or the expression “to be perfectly honest” (example 9), are backstage markers. Most of the study’s participants have authored narratives about their work in the strict, formalized genre of CS, thereby performing on the Goffmanian ‘front stage’ for an audience composed of senior management, REF panelists and, ultimately, perhaps “politicians”, “the government”. However, when speaking on the ‘back stage’ context of an anonymous interview, many researchers actively reject the accuracy of the submitted CSs as representations of their work. Many express a nuanced, often critical, view on impact.

Respondents frequently differentiate between the way they perceive ‘impact’ on different ‘levels’, or from the viewpoint of their different ‘roles’ (scholar, research manager, citizen…). One academic can hold different (even contradictory) views on the assessment of impact. Someone who strongly criticizes the Impact Agenda as an administrative practice might be supportive of ‘impact’ on a personal level or vice versa. See the answer of a linguist asked whether ‘impact’ enters into play when he assesses the work of other academics:

When I look at other people’s work work as a linguist, I don’t worry about that stuff. (…) As an administrator, I think that linguistics, like many sciences, has neglected the public. (…) At some point, when we would be talking about promotion (…) I would want to take a look at the impact of their work. (…) And that would come into my thinking in different times.

Int13, academic, example 11

Interestingly, in the studied corpus there isn’t a simple correlation between conducting research which easily ‘lends itself to impact’ and a positive overall attitude to impact evaluation.

Subjectivation