- How It Works

- Testimonials

Essay About Sigmund Freud Theory

INTRODUCTION

Sigmund Freud was one of the most outstanding psychologists of the 20th century, whose contribution in the development of psychology can hardly be underestimated. In this regard, his theory of personality is particularly significant because this theory has changed consistently views of psychologists as well as average people on the concept of personality and its development. In fact, Freud was one of the first psychologists, who suggested the idea of existence of sub-conscience and hidden desires and inclinations of individuals. At the same time, he has managed to classify accurately human personality, its development and key components. What is more important his theory of personality explains the mechanism how human personality shapes and functions as the result of the struggle between inclinations and desires of individuals, their conscious constraints, and their ego. In fact, Freud’s theory of personality was a considerable leap forward to the development of the modern psychology because this theory suggested basic concepts related to personality and the mechanism of their functioning.

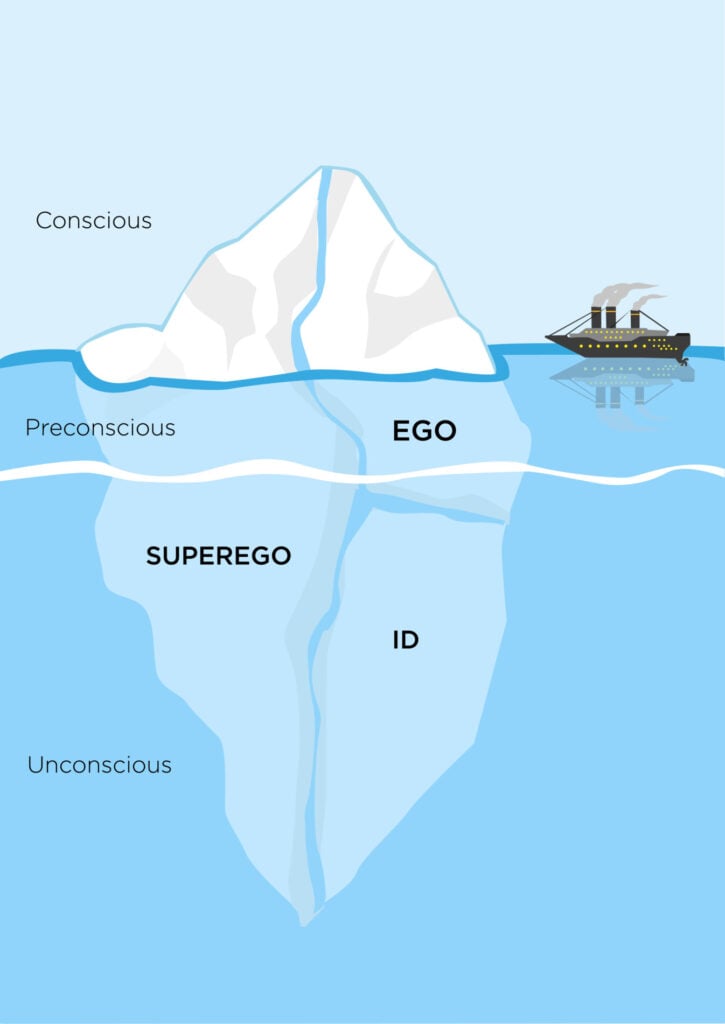

In fact, Freud distinguishes three major elements of human personality, which are in a permanent interaction and struggle. The first element is the Id. According to Freud, the Id is present since the birth of an individual. As the matter of fact, the Id consists of basic human needs. The Id is close to physiological needs of humans and is driven by basic human physiological needs. The Id is deprived of rationalism and evokes strong emotions and desires which make people acting or thinking of action (Engler, 2006). The Id is often irrelevant to the reality because an individual may want something that is unachievable at the moment. For instance, an individual may want to drink but he or she may have no drink at hand. The Id comes first and is present in individuals since the birth. Therefore, the Id is the innate and exists in people since the beginning of their life.

The Ego is another element of human personality, which is shaped in the course of the development of an individual. The Ego is based on the reality principle. This means that the Ego understands the reality of circumstances and reasons prevail in the Ego. What is meant here is the fact that, unlike the Id, which is driven by basic needs of individuals mainly, the Ego considers and evaluates the surrounding reality, desires and wants of an individual and finds the way to satisfy needs and wants of an individual. In contrast to the Id, which is driven by basic needs, the Ego is rational and reasonable because the Ego helps an individual to plan his or her actions and implement the plan to meet his or her needs and wants. For instance, returning to the example of an individual’s desire to have a drink at the Id level, the Ego makes up a plan, namely to take a glass to pour a drink into.

THE SUPEREGO

However, the personality of an individual does not end up with the Ego. In terms of his theory of personality, Freud distinguishes one more element of personality, the Superego, or conscience. In fact, the Superego goes beyond the reason and rationalism of the Ego to develop a plan to satisfy basic needs of an individual. Instead, the Superego evaluates possible human action and behavior referring to moral norms and principles and beliefs, which an individual has acquired in the course of his or her development. Freud stood on the ground that the Superego dictated human sense of right and wrong. In such a way, the Superego is the moral judgment of an individual’s personality. Unlike the Ego, which just plans how to act and to meet individual’s goals and needs, the Superego evaluates and justifies an individual’s behavior in terms of good and bad, right and wrong (Hjelle and Ziegler 1992). For instance, in case of the Id’s desire to have a drink and the Ego’s plan to pour a drink, the Superego will consider, which drink to pour and what the effect drinking can have. To put it more precisely, at the Superego level an individual may consider drinking a gin but the Superego may oppose to it because it is bad to an individual’s health, instead, the Superego may push the individual to drinking juice because it is good for an individual’s health and, therefore, right.

DRIVING FORCES

However, along with basic needs that drive human desires, wants, needs and actions, Freud distinguished two major forces that drove personality: libido (sex) and aggression (Lombardo and Foschi, 2002). Freud believed that libido and aggression define human actions and affect the behavior of individuals to the extent that they can shape the major traits of the personality of an individual. At this point, it is important to place emphasis on the fact that Freud viewed the personality development as a steady process which is vulnerable to change and evolution under the impact of human experience. What is meant here is the fact that an individual is born with the Id. However, the individual develops his or her Ego, which shapes reason and objective understanding of the surrounding reality and the self by the individual (Bradberry, 2007). But Freud stressed that human experience could affect how the individual perceives him- or herself. Moreover, the Superego was also vulnerable to the impact of the individual development. What is meant here is the fact that, in the course of the development, the individual acquires certain experience, knowledge, shapes his or her views and beliefs that lay foundation to the individual’s ego and superego. Therefore, the experience of an individual is crucial for the formation of his or her personality. For instance, a psychological trauma an individual has suffered in the early childhood could have had some effects in the adult life of the individual.

PERSONALITY BALANCE AND DEFENCE MECHANISMS

Finally, Freud argued that the Id, Ego and Superego were often in a state of conflict and struggle but the ultimate goal was the establishment of healthy balance between the Id, Ego and Superego. According to Freud, the Ego attempts to find the balance between the Id and Superego. In practice, this means that an alcoholic can have the desire to drink a gin (the desire is driven by the Id) but he or she takes control over his or her desire because the individual understands the negative impact of alcohol on his or her health and behavior (the refusal occurs under the impact of the Superego, which tells an individual that drinking the gin is wrong), and the final decision is taken by the Ego.

However, Freud pointed out that to keep the balance personality could use defense mechanism, including: denial, displacement, intellectualization, projection, rationalization, reaction formation, regression, repression, sublimation, suppression (Santrock, 2008). Defense mechanisms could be applied depending on the situation and individual’s experience. The main point of defense mechanisms is the protection of the Ego from excessive pressure from the part of the Id or Superego.

Thus, taking into account all above mentioned, it is important to place emphasis on the fact that Freud’s theory of personality has opened wider horizons for the further study of human personality. Freud suggested a new, original view on personality and his innovative ideas laid the foundation to further studies in the field of psychology. At the same time, his view on personality, including its major elements, such as the Id, Ego, and Superego, is still relevant. In fact, Freud’s theory of personality is one of the fundamental theories of modern psychology.

REFERENCES:

Bradberry, T. (2007). The Personality Code. New York: Putnam. Engler, B. (2006). Personality Theories. Houghton Mifflin. Hjelle, L. and D. Ziegler. (1992). Personality: Basic Assumptions, Research and Applications. New York: McGraw Hill. Lombardo, G.P. and Foschi R. (2002). “The European origins of personality psychology.” European psychologist, 7, 134-145. Lombardo G.P. and Foschi R. (2003). “The Concept of Personality between 19th Century France and 20th Century American Psychology.” History of Psychology, vol. 6; 133-142. Santrock, J.W. (2008). “The Self, Identity, and Personality.” In Mike Ryan(Ed.). A Topical Approach To Life-Span Development. New York: McGraw-Hill, p.411-412.

Related posts:

- Trait Theory of Leadership Essay

- Childhood to Young Adulthood Essay

- The Main Four Goals of Psychology

Freud’s Theory of Personality (Explained for Students)

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Learn about our Editorial Process

Sigmund Freud developed a theory of personality which postulates that each individual’s personality is comprised of three entities: the id , the ego , and the superego .

Each of these entities can be thought of as psychological energies that operate within the human psyche. Each has its own objectives and ways of being expressed.

An individual’s overt behavior is a result of the three components of personality trying to fulfil their separate roles.

But what we see on the outside is really just a glimmer of what is happening behind the closed doors of the mind – our covert behavior .

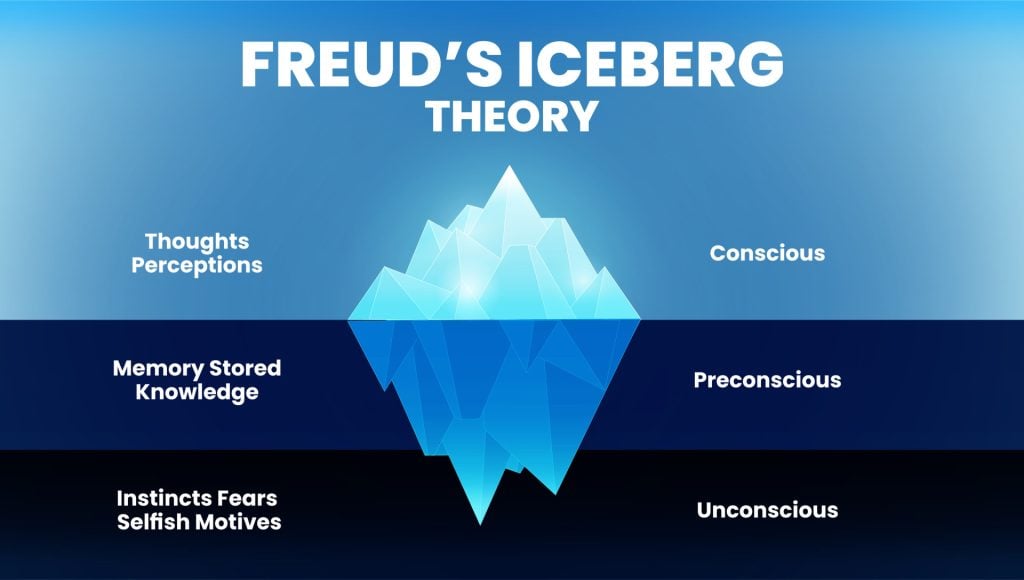

According to Freud, the individual is often unaware of how their behavior is determined because the most primitive part of the personality, the id, usually operates outside of conscious awareness.

Freud’s Three Components of Personality

Freud believes the personality is made up of three components: the id, ego, and superego.

- The Id: The id is the impulsive and instinctual component that operates on the pleasure principle . The id wants its needs satisfied as soon as possible ( aka instant gratification ), and is not concerned with consequences or ethics. The id is present from birth onward and exerts its influence on our behavior outside of conscious awareness. See more: Examples of the Id .

- The ego: The ego is the pragmatic component of the personality and operates on the reality principle . The ego helps control the impulses of the id, but at the same time tries to find ways to satisfy those needs based on the constraints of the situation. The ego relies on the delay of gratification to control the id’s impulsive drives until a solution can be achieved.

- The superego: The superego represents the standards and moral principles of the individual. These standards are internalized over time and come from one’s parents and society. This part of personality emerges around the age of five. It consists of two components: the conscience and the ego ideal . The conscience , part of the superego, contains the rules learned about what is good and bad behavior. When a person does something they know is wrong, the conscience is where the feelings of guilt and shame come from. The ego ideal is what the ego strives to achieve. It represents the best example of what the person should become. The ego ideal can be defined by one’s parents or society. See more: Examples of the superego .

According to Freud’s theory of personality, a person’s behavior is a result of the competing influences of the three components of personality.

For example, when an individual acts impulsively, it is the result of the id. When an individual acts with restraint and discipline, it is the result of a strong ego and well-formed superego.

Here’s a comparative table of the three elements of Freud’s personality theory:

| Ego | Superego | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Seeks pleasure | Mediates reality and desires | Imposes moral standards on behavior | |

| Unconscious | Conscious, Preconscious, Unconscious | Conscious, Preconscious, Unconscious | |

| Pleasure principle | Reality principle | Morality principle | |

| Present from birth | Develops during infancy and uses | Develops around the age of five |

Origins of Freud’s Theory of Personality Theory

Sigmund Freud developed his theory of personality in the late 19 th century. He was heavily influenced by his advisor at the University of Vienna, Ernest von Brücke.

Brücke believed that all living organisms were comprised of finite energy systems. This energy circulates around the various systems within the organism.

Freud postulated the concept of the libido based on this notion. According to Freud, the libido was primarily a sexual energy in the id that is expressed through behavior.

However, the actions of the libido are often inconsistent with the morals of society represented in the superego. This can lead to neurosis or psychosis if the ego is unable to resolve the conflicting demands of each.

Other scholars such as Alfred Adler (2002) and Carl Jung (2014) incorporated aspects of Freud’s thinking into their own theories of human behavior .

See Also: Examples of The Famous Freudian Slip

The Role of Defense Mechanisms in Freud’s Theory

Defense mechanisms are strategies that the individual uses to cope with anxiety (Freud, 1894, 1937). When confronted with disturbing thoughts or conflicting information about the self, defense mechanisms kick-in to help restore emotional balance.

They often involve a distortion of reality and operate outside of conscious awareness.

Although some people consider defense mechanisms to be negative and a sign of dysfunction, Freud believed that defense mechanisms serve a valuable purpose.

They reduce anxiety, help the individual cope, and are necessary for healthy human functioning.

Although at one point maligned as incapable of being scientifically tested, today’s perspective on the utility of defense mechanisms is quite different.

“More than half century of empirical research has demonstrated the impact of defensive functioning in psychological well-being, personality organization and treatment process-outcome” (Di Giuseppe & Perry, 2021, p. 1).

Real-Life Applications of this Theory

The most common application of Freud’s theory of personality is in the treatment of psychological disorders.

Freud’s version of therapy is referred to as psychoanalysis. It is used today primarily to treat depression and anxiety disorders.

The goal in psychoanalysis is to help the patient become more aware of the recurring dysfunctional thoughts and feelings that prevent them from leading a normal life and being happy.

This is accomplished through a variety of techniques, including: free association, inkblot interpretations, resistance and transference analysis, and the interpretation of dreams.

Psychoanalysis can take time because it seeks long-lasting change that results in altering the structure of the individual’s personality and patterns of reasoning.

In a review of the literature, Shedler (2010) states that:

“available evidence indicates that effect sizes for psychodynamic psychotherapies are as large as those reported for other treatments that have been actively promoted as “empirically supported” and “evidence based.” (p. 18).

Criticisms of Freud’s Theory of Personality

Freud’s theories, while groundbreaking in the field of psychology, have not escaped critical evaluation.

- Lack of Empirical Evidence: One of the primary criticisms levied against his theories of personality concerns lack of empirical evidence. Freud’s concepts such as the id, ego, and superego, while interesting, are largely abstract, meaning that they are hard to measure and therefore to validate scientifically. Scientists like Karl Popper consider Freud’s theories as pseudoscientific for this reason, because they lack falsifiability (Popper, 1959).

- Lack of Consideration of Environmental Context: critics point out Freud’s theory disregards the effects of the environment on personality development. Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory , for example, underscores the importance of observational learning, environmental influence, and self-efficacy in shaping one’s personality, rendering Freud’s focus on childhood conflicts and unconscious urges incomplete (Bandura, 1977). It’s important to note that while Freud’s theory has faced criticism, it undeniably made a profound impact on psychology, sparking conversations that continue to shape the field even today.

- Lack of Real-Life Complexity: The conceptual triad of id, ego, and superego, as proposed by Freud, has also been the subject of criticism. Notably, critics have found fault in the overly simplistic nature of these three entity-like components (Rennison, 2015). They argue that the human psyche is complex and cannot be simply divided into these neat compartments. The tripartite structure is seen as too theoretically convenient, lacking nuance and complexity. Cognitive psychologists , especially, deem Freud’s constructs unhelpful in predicting behavioral outcomes due to their inconsistent definitions and applications across contexts.

Freud’s theory of personality involves three structures that exist in the human psyche. Each one has its role in the expression and management of impulses and needs.

While the id represents a person’s instincts and primal urges, the superego represents the internalized standards derived from parental and societal influences. The ego is tasked with fulfilling the ids needs based on the constraints of reality and principles of morality from the superego.

When the ego becomes aware of disturbing thoughts and desires that come from the id, it engages in a defense mechanism. By distorting reality in various ways, the anxiety experienced from becoming aware of those desires is resolved.

Freud’s theory of personality has implications for the treatment of psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety. This form of therapy is referred to as psychoanalysis. Although time consuming, research shows that psychoanalysis is effective.

Other Theories of Personality

- Humanistic Theory of Personality (Rogers and Maslow)

- Trait Theory of Personality (Influential in Leadership Theories)

Adler, A. (2002). The collected clinical works of Alfred Adler (Vol. 1). Alfred Adler Institute. American Psychological Association. Psychodynamic psychotherapy brings lasting benefits through self-knowledge .

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory . London: Prentice-Hall.

Bowins, B. (2004). Psychological defense mechanisms: A New Perspective. American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 64 , 1-26.

Cramer, P. (2000). Defense mechanisms in psychology today: Further processes for adaptation. American Psychologist , 55 (6), 637-646.

Di Giuseppe, M., & Perry, J. C. (2021). The hierarchy of defense mechanisms: Assessing defensive functioning with the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-Sort. Frontiers in Psychology , 12 , 718440.

Freud, S. (1894). The neuro-psychoses of defence . SE, 3: 41-61.

Freud, A. (1937). The Ego and the mechanisms of defense , London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

Freud, S. (2012). The basic writings of Sigmund Freud . Modern library.

Green, C. D. (2019). Where did Freud’s iceberg metaphor of mind come from? History of Psychology , 22 (4), 369b.

Jung, C. G. (2014). The archetypes and the collective unconscious . Routledge.

Popper, K. (1959). The Logic of Scientific Discovery . Hutchinson & Co

Rennison, N. (2015). Freud and psychoanalysis: Everything you need to know about id, ego, super-ego and more . Oldcastle books.

Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist , 65 (2), 98.

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Cooperative Play Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Cooperative Play Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Journal Archive

- Research Papers

- Popular Blog

The Freudian Theory of Personality

Sigmund Freud is considered to be the father of psychiatry. Among his many accomplishments is, arguably, the most far-reaching personality schema in psychology: the Freudian theory of personality. It has been the focus of many additions, modifications, and various interpretations given to its core points. Despite many reincarnations, Freud’s theory is criticized by many (e.g. for its perceived sexism) and it remains the focus of hot discussions on its relevance today.

Freud was a one of a kind thinker. There can be little question that he was influenced by earlier thinking regarding the human mind, especially the idea of there being activity within the mind at a conscious and unconscious level yet his approach to these topics was largely conceptual. His theoretical thoughts were as original as they were unique. It is a testament to Freud’s mind to know that whether you agree, disagree, or are ambivalent about his theory, it remains as a theoretical cornerstone in his field of expertise.

Human Personality: The adult personality emerges as a composite of early childhood experiences, based on how these experiences are consciously and unconsciously processed within human developmental stages, and how these experiences shape the personality.

Not every person completes the necessary tasks of every developmental stage. When they don’t, the results can be a mental condition requiring psychoanalysis to achieve proper functioning.

Stages of Development

Believing that most human suffering is determined during childhood development , Freud placed emphasis on the five stages of psychosexual development. As a child passes through these stages unresolved conflicts between physical drives and social expectation may arise.

These stages are:

- Oral (0 – 1.5 years of age): Fixation on all things oral. If not satisfactorily met there is the likelihood of developing negative oral habits or behaviors.

- Anal (1.5 to 3 years of age): As indicated this stage is primarily related to developing healthy toilet training habits.

- Phallic (3 – 5 year of age): The development of healthy substitutes for the sexual attraction boys and girls have toward a parent of the opposite gender.

- Latency (5 – 12 years of age): The development of healthy dormant sexual feelings for the opposite sex.

- Genital (12 – adulthood): All tasks from the previous four stages are integrated into the mind allowing for the onset of healthy sexual feelings and behaviors.

It is during these stages of development that the experiences are filtered through the three levels of the human mind. It is from these structures and the inherent conflicts that arise in the mind that personality is shaped. According to Freud while there is an interdependence among these three levels, each level also serves a purpose in personality development. Within this theory the ability of a person to resolve internal conflicts at specific stages of their development determines future coping and functioning ability as a fully-mature adult.

Each stage is processed through Freud’s concept of the human mind as a three tier system consisting of the superego, the ego, and the id. The super ego functions at a conscious level. It serves as a type of screening center for what is going on. It is at this level that society and parental guidance is weighed against personal pleasure and gain as directed by ones id. Obviously, this puts in motion situations ripe for conflict.

Much like a judge in a trial, once experiences are processed through the superego and the id they fall into the ego to mediate a satisfactory outcome. Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean a sense of self, but later revised it to mean a set of psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, reality testing, control, planning, defense, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory.

The egocentric center of the human universe, Freud believed that within this one level, the id is constantly fighting to have our way in everything we undertake.

So where does this leave us? In the words of Jim Morrison in a song he wrote for the Doors “I want the world and I want it NOW!” seems to be on the tip of many persons lips. It could have been entitled Ode to the Id .

There are many mental illnesses that place the id in the forefront decision making. In particular, there are those whose lives are lived on a totally narcissistic level. Then there are those with anti-social personalities, psychotic like illnesses, and more. In the world of Freud, it is the neurotic person that is most affected by the principles of his theory.

As a result Freud laid out his plan for treatment: psychoanalysis . The treatment has been in use for many years with many adaptations given to it. On the plus side, psychoanalysis do present a client with the structure and time to resolve neurotic issues. On the negative side there is always expressed concern over the cost. Being that it does take time for psychoanalysis to be effective there is an associated cost that can be prohibitive.

Recent Posts

Eric Fromm and the Social Unconscious

Alfred Adler’s Personality Theory and Personality Types

The Quest for Self-Actualization

The Jungian Model of the Psyche

Mental Disorders and the Limbic-cortical Theory of Consciousness

Processing Information with Nonconscious Mind

Sigmund Freud’s The Ego and the Id

Freud died 80 years ago this week. In this “Virtual Roundtable,” three scholars debate the legacy of his 1923 text.

Sigmund Freud died 80 years ago this week, and his 1923 study, The Ego and the Id , which introduced many of the foundational concepts of psychoanalysis, entered the public domain earlier this year. Freud’s ideas have long been absorbed by popular culture, but what role do they continue to play in the academy, in the clinical profession, and in everyday life? To answer those questions, this roundtable discussion—curated by Public Books and JSTOR Daily —asks scholars about the legacy of The Ego and the Id in the 21st century.

• Elizabeth Lunbeck: Pity the Poor Ego! • Amber Jamilla Musser: The Sunken Place: Race, Racism, and Freud • Todd McGowan: The Superego or the Id

Pity the Poor Ego!

Elizabeth Lunbeck

It would be hard to overestimate the significance of Freud’s The Ego and the Id for psychoanalytic theory and practice. This landmark essay has also enjoyed a robust extra-analytic life, giving the rest of us both a useful terminology and a readily apprehended model of the mind’s workings. The ego, id, and superego (the last two terms made their debut in The Ego and the Id ) are now inescapably part of popular culture and learned discourse, political commentary and everyday talk.

Type “id ego superego” into a Google search box and you’re likely to be directed to sites offering to explain the terms “for dummies”—a measure of the terms’ ubiquity if not intelligibility. You might also come upon images of The Simpsons: Homer representing the id (motivated by pleasure, characterized by unbridled desire), Marge the ego (controlled, beholden to reality), and Lisa the superego (the family’s dour conscience), all of which need little explanation, so intuitively on target do they seem.

If you add “politics” to the search string, you’ll find sites advancing the argument that Donald Trump’s success is premised on his speaking to our collective id, our desires to be free of the punishing strictures of law and morality and to grab whatever we please—“a flailing tantrum of fleshly energy.” Barack Obama in this scheme occupies the position of benign superego: incorruptible, cautious, and given to moralizing, the embodiment of our highest ideas and values but, in the end, not much fun. You’ll also glean from Google that Trump’s ego is fragile and needy but also immense and raging, its state—small or large?—a dire threat to the nation’s stability and security.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

In these examples, the ego is used in two distinct, though not wholly contradictory, ways. With The Simpsons , the ego appears as an agency that strives to mediate between the id and superego. When we speak of Trump’s fragile ego, the term is being used somewhat differently, to refer to the entirety of the self, or the whole person. When we say of someone that their ego is too big, we are criticizing their being and self-presentation, not their (presumably) weak superego.

The idea of the ego as agency is routinely considered more analytically rigorous and thus more “Freudian” than the ego-as-self, yet both interpretations of the ego are found not only in popular culture, but also—perhaps surprisingly—in Freud. Further, I would argue that the second of these Freudian conceptualizations, premised on feelings, is more consonant with a distinctively American construal of the self than are the abstractions of ego psychology. Understanding why this is so necessitates a look at the post-Freud history of the ego in America—in particular at the attempts of some psychoanalysts to clear up ambiguities in Freud’s texts, attempts that luckily for us met with only mixed success.

As Freud proposed in The Ego and the Id , three agencies of the mind jostle for supremacy: the ego strives for mastery over both id and superego, an ongoing and often fruitless task in the face of the id’s wild passions and demands for satisfaction, on the one hand, and the superego’s crushing, even authoritarian, demands for submission to its dictates, on the other. The work of psychoanalysis was “to strengthen the ego”; as Freud famously put it 10 years later, “where id was, there ego shall be.”

The Freudian ego sought to harmonize relations among the mind’s agencies. It had “important functions,” but when it came to their exercise it was weak, its position, in Freud’s words, “like that of a constitutional monarch, without whose sanction no law can be passed but who hesitates long before imposing his veto on any measure put forward by Parliament.” Elsewhere in the essay, the ego vis-à-vis the id was no monarch but a commoner, “a man on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse … obliged to guide it where it wants to go.” Submitting to the id, the ego-as-rider could at least retain the illusion of sovereignty. The superego would brook no similar fantasy in the erstwhile royal, instead establishing “an agency within him” to monitor his desires for aggression, “like a garrison in a conquered city.” Pity the poor ego!

It could be argued that the Viennese émigré psychoanalysts who took over the American analytic establishment in the postwar years did precisely that. They amplified this Freudian ego’s powers of mastery while downplaying its conflicts with the id and superego. They formulated a distinctively optimistic and melioristic school of analytic thought, “ego psychology,” in which the ego was ideally mature and autonomous, a smoothly operating agency of mind oriented toward adaptation with the external environment. More than a few commentators have argued that ego psychology’s celebration of compliance and de-emphasis of conflict fit perfectly with the demands of the postwar corporate state as well as with the prevailing stress on conformity and fitting in. Think here of William H. Whyte’s The Organization Man , published in 1956, or of David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd , from 1950, best sellers that were read as laments for a lost golden age of individualism and autonomy.

Among the professed achievements of the mid-century ego psychologists was clearing up Freud’s productive ambiguity around the term’s meanings; ego would henceforth refer to the agency’s regulatory and adaptive functions, not to the person or the self. Consider that the doyen of ego psychology, Heinz Hartmann, gently chided Freud for sometimes using “the term ego in more than one sense, and not always in the sense in which it was best defined.”

Ego psychologists’ American hegemony was premised on their claim to being Freud’s most loyal heirs; The Ego and the Id ranked high among their school’s foundational texts. Freud’s text, however, supports a conceptualization of the ego not only as an agency of mind (their reading) but also as an experienced sense of self. In it, Freud had intriguingly referred to the ego as “first and foremost a body-ego,” explaining that it “is ultimately derived from bodily sensations.”

Ignored by the ego psychologists, Freud’s statement was taken up in the 1920s and 1930s by, among others, the Viennese analyst Paul Federn, who coined the term “ego feeling” to capture his contention that the ego was best construed as referring to our subjective experience of ourselves, our sense of existing as a person or self. He argued that the ego should be conceived of in terms of experience, not conceptualized as a mental abstraction. Ego feeling, he explained in 1928, was “the sensation, constantly present, of one’s own person—the ego’s perception of itself.” Federn was a phenomenologist, implicitly critiquing Freud and his heirs for favoring systematizing over felt experience while at the same time fashioning himself a follower, not an independent thinker. Marginalization has been the price of his fealty, as he and his insights have been largely overlooked in the analytic canon.

When we talk of the American ego, we are more likely than not speaking Federn-ese. Federn appreciated the evanescence of moods and the complexity of our self-experiences. Talk of our “inner resources” and equanimity, of the necessity of egoism and its compatibility with altruism, of commonplace fantasies of “love, greatness, and ambition” runs through his writings. Even the analytic session is likely focused more manifestly on the “goals of self-preservation, of enrichment, of self-assertion, of social achievements for others, of gaining friends and adherents, up to the phantasy of leadership and discipleship” than on ensuring the ego’s supremacy over the id and superego.

The Ego and the Id supports such a reading of the ego as experiencing self, the individual possessed of knowledge of her bodily and mental “selfsameness and continuity in time.” Federn’s “ego feeling” is also compatible with 1950s vernacular invocations of the “real self” as well as with the sense of identity that Erik Erikson defined in terms of the feelings individuals have of themselves as living, experiencing persons, the authentic self that would become the holy grail for so many Americans in the 1960s and beyond. Erikson, also an ego psychologist but banished from the mainstream of analysis for his focus on the experiential dimension of the self, would capture this same sensibility under the rubric of identity. His delineation of the term identity to refer to a subjective sense of self, taken up overnight within and beyond psychoanalysis, arguably did more to ensure the survival of the discipline in the United States than did the all the labors of Freud’s most dutiful followers.

Thus, while Google may give us images (including cartoons) of a precisely divvied-up Freudian mind, it is the holistic ego-as-self that is as much the subject of most of our everyday therapeutic, analytically inflected talk. This ego-as-self is less readily represented pictorially than its integrated counterpart but nonetheless central to our ways of conveying our experience of ourselves and of others. It is as authentically psychoanalytic as its linguistic double, neither a corruption of Freud’s intentions nor an import from the gauzy reaches of humanistic psychology. When we invoke Trump’s outsized and easily bruised ego, for example, we are calling on this dimension of the term, referring to his sense of self—at once inflated and fragile. Federn has been forgotten, but his feelings-centered analytic sensibility lives on. It may be all the more relevant today, when, as many have observed, our feelings are no longer sequestered from reason and objectivity but, instead, instrumentally mobilized as the coin of the populist realm.

Jump to: Elizabeth Lunbeck , Amber Jamilla Musser , Todd McGowan

The Sunken Place: Race, Racism, and Freud

Amber Jamilla Musser

In a tense scene from the 2017 film Get Out , Missy (Catherine Keener) finds her daughter’s boyfriend, Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), sneaking a cigarette outside and invites him into the sitting room, which also functions as a home office for her therapy clients. Chris, a black photographer, has just met his white girlfriend, Rose’s, liberal family, including her mother, Missy, for the first time. As the two sit across from one another, Missy asks Chris about his childhood, her spoon repeatedly striking the inside of a teacup, and Chris, eyes watering uncontrollably, begins to sink deep into the “sunken place.” As his present surroundings shift out of view, he flails and falls through a large black void, before eventually waking in his own bed, uncertain as to what’s taken place. The therapy office setting is worth noting, for while what follows this early hypnosis scene is a horror-comedy about racism, psychoanalytic ideas of the unconscious help illuminate race relations in the film and beyond.

In the film, the “sunken place” refers to a fugue state that subdues the black characters so that (spoiler alert) the brains of the highest white bidder can be transplanted into their bodies. While this large black void is the product of director Jordan Peele’s imagination, the “sunken place” has culturally come to signify a pernicious aspect of racialization; namely, the nonwhite overidentification with whiteness. Recent memes make this connection clear. In one, Kanye West, who not too long ago argued that President Trump was on “a hero’s journey,” appears in the armchair from Get Outwearing a “Make America Great Again” hat, tears streaming down his face. In another, the actress Stacey Dash, who ran for Congress as a Republican from California, stares blankly out of a window.

Freud’s The Ego and the Id , however, gives us another way to understand the “sunken place.” Writing in 1923,Freud presents a comprehensive map of the psyche as a space where the ego, superego, and id form a dynamic structure that reacts to and is formed by multiple varieties of the unconscious. The superego, Freud argues, acts as a sort of “normative” check on behavior, while the id is libidinal energy and purely hedonistic. The ego, what is consciously enacted, balances these two different modes of the unconscious in order to function.

The Freudian model helps us to understand how racialization, the process of understanding oneself through the prism of racial categories, occurs at the level of the unconscious. When viewed in the context of psychoanalysis, the “sunken place” is what happens when the superego’s attachment to whiteness runs amok; when Chris’s eyes tear up and he involuntarily scratches the armchair, he is enacting bodily resistance that is connected to the id. What’s more, Freud’s structure also allows us to extend this understanding of race beyond the individual, toward thinking about why the “sunken place” can be seen as a metonym for race relations in the United States writ large.

Race itself was largely underdiscussed in Freud’s works. In one of his most explicit engagements with racial difference, 1930’s Civilization and its Discontents , he mostlyconfined his theorizations of racial difference to thinking about the atavistic and primitive. Following Freud, other analysts in the early 20th century tended to ignore underlying racial dynamics at work in their theories. For example, if patients discussed the ethnicity or race of a caretaker or other recurring figure in their lives, analysts tended not to explore these topics further. As a rich body of contemporary critical work on psychoanalysis has explored, this inattention to race created an assumption of universal normativity that was, in fact, attached to whiteness.

While psychoanalysis has historically ignored or mishandled discussions of race, Freud’s The Ego and the Id introduces concepts that are useful in thinking through race relations on both an individual and a national level. His tripartite division of the psyche can help show us how race itself functions as a “metalanguage,” to use Evelyn Higginbotham’s phrase , one that structures the unconscious and the possibilities for the emergence of the ego. In Get Out , “the sunken place” is the stage for a battle between a white-identified superego, which is induced through brain transplantation or hypnosis, and a black-identified id. Outside of the parameters of science fiction, however, this racialized inner struggle offers insight into theorizations of assimilation and racialization more broadly.

Sociologist Jeffrey Alexander describes assimilation, a process of adapting to a form of (implicitly white) normativity, as an attempt to incorporate difference through erasure even while insisting on some inassimilable (racialized) residue. Alexander writes , “Assimilation is possible to the degree that socialization channels exist that can provide ‘civilizing’ or ‘purifying’ processes—through interaction, education, or mass mediated representation—that allow persons to be separated from their primordial qualities. It is not the qualities themselves that are purified or accepted but the persons who formerly, and often still privately, bear them. ” The tensions between these performances of white normativity—“civilization”—and the particular “qualities” that comprise the minority subject that Alexander names are akin to the perpetual struggle Freud describes between the superego, id, and ego.

Drawing on psychoanalysis, recent theorists such as David Eng and Anne Anlin Cheng have emphasized the melancholia that accompanies assimilation—Chris’s involuntary tears in the “sunken place” and the instances of staring out the window, going on evening runs, and the flash-induced screams of the other black characters who have received white-brain implants perhaps being among the most extreme forms. Cheng argues that having to assimilate to a white culture produces melancholy at both the unattainability of whiteness for black and brown subjects and at the repression of racial otherness necessary to sustain white dominance. Cheng’s description of the “inarticulable loss that comes to inform the individual’s sense of his or her own subjectivity” helps explain why the conditions of white normativity can be particularly psychologically harmful for nonwhite subjects.

While Freud’s concepts are useful for understanding the psychological burden of racialization for nonwhite subjects under conditions of white normativity, scholars have also explored how Freud’s concepts of the ego, id, and superego can be used to theorize what it means to frame whiteness as a form of national consciousness. Describing the sadistic impulses of Jim Crow, theorist and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon argued that the ego of the United States is masochistic. In imagining the psychic structure of the country as a whole, he saw a clash between the nation’s aggressive id—which was attempting to dominate black people—and its superego—which felt guilt at the overt racism of a supposedly “democratic” country.

Fanon argued that the United States’ desires to punish black people (manifesting in virulent antiblack violence) were swiftly “followed by a guilt complex because of the sanction against such behavior by the democratic culture of the country in question.” Fanon exposed the hypocrisy inherent in holding anti-racist ideals while allowing racist violence to flourish. The country’s national masochism, he argued, meant that the United States could not recognize its own forms of white aggression; instead, the country embraced a stance of passivity and victimization in relation to nonwhites disavowing their own overt violence. Or, in Freud’s language, the country submerged the id in favor of an idealization of the superego.

We see this dynamic, too, in Get Out , where the white characters fetishize black physicality and talent as somehow inherent to their race, while strenuously denying any charges of racism. In the film, the white characters who wish to inhabit black bodies understand themselves primarily as victims of aging and other processes of debilitation, a logic that allows them to use their alleged affection for blackness to cloak their aggressive, dominative tendencies. Before Chris and Rose meet her parents, Rose tells him that they would have voted for Obama for a third term, a statement repeated in a later scene, by her father (Bradley Whitford), when he notices Chris watching the black domestic workers on the property: “By the way, I would have voted for Obama for a third term if I could. Best president in my lifetime. Hands down.” In such a statement, we can see ways that the masochistic white ego Fanon spoke about remains an accurate reflection of national debates about political correctness, what counts as racism, and the question of reparations.

As Get Out helps dramatize, we can use the legacy of Freud’s parsing of the unconscious to identify the tensions at work within individuals struggling to assimilate to a perceived idea of white normativity. But we can also use psychoanalytic concepts to understand how certain ideas of race have created a white national consciousness, which, in the United States and elsewhere, is in crisis. At this broader scale, we can begin to see how the national superego has sutured normativity to a pernicious idea of whiteness, one that manifests psychological, but also physical, aggression against nonwhite subjects.

For, while the presumption that whiteness is the “normal” and dominant culture situates it in the position of the superego for individuals who are attempting to assimilate, this assumption of superiority is actually an anxious position, haunted by racial others and constantly threatened by the possibility of destabilization. For many, this has led to difficulty reckoning with white culture’s violent tendencies, and to an insistence on its innocence. Working more with these Freudian dynamics might help us think more carefully about both strategies of resistance and survival for nonwhite subjects and what fuller contours of white accountability could look like.

The Superego or the Id

Todd McGowan

To properly understand The Ego and the Id ,we should mentally retitle it The Superego . The two terms most frequently invoked from Freud’s 1923 text are, perhaps unsurprisingly, the ego and the id . We have easily integrated them into our thinking and use them freely in everyday speech. The third term of the structural model—the superego —receives far less attention. This is evident, for instance, in the pop psychoanalysis surrounding Donald Trump. Some diagnose him as a narcissist, someone in love with his own ego. Others say that he represents the American id, because he lacks the self-control that inhibits most people. According to these views, he has either too much ego or too much id. Never one to be self-critical, Trump’s problem doesn’t appear to be an excess of superego. If the superego comes into play at all in diagnosing him, one would say that the problem is his lack of a proper superego.

In the popular reception of Freud’s thought, the discovery of the id typically represents his most significant contribution to an understanding of how we act. The id marks the point at which individuals lack control over what they do. The impulses of the id drive us to act in ways that are unacceptable to the rest of society. And yet, the concept of the id nonetheless serves a comforting function, in that it enables us to associate our most disturbing actions with biological impulses for which we have no responsibility. For this reason, we have to look beyond the id if we want to see how Freud most unsettles our self-understanding.

Freud’s introduction of the superego, in contrast, represents the most radical moment of The Ego and the Id , because it challenges all traditional conceptions of morality. Typically, our sense of the collective good restrains the amorality of our individual desires: we might want to crash our car into the driver who has just cut us off, but our conscience prevents us from disrupting our collective ability to coexist as drivers on the road. Historically, the reception of Freud’s work has considered the superego as this voice of moral conscience, but Freud theorizes that there are amoral roots to this moral voice. According to Freud, the superego does not represent the collective good, but manifests the individual desires of the id, which run counter to the collective good.

With the discovery of the concept of the superego, Freud reshapes how we think of ourselves as moral actors. If Freud is right that the superego “reaches deep down into the id,” then all our purportedly moral impulses have their roots in libidinal enjoyment. When we upbraid ourselves for a wayward desire for a married coworker, this moral reproof doesn’t dissipate the enjoyment of this desire but multiplies it. The more that we experience a desire as transgressive, the more ardently we feel it. In this way, the superego enables us to enjoy our desire while consciously believing that we are restraining it.

The concept of the superego reveals that the traditional picture of morality hides a fundamental amorality, which is why the response to The Ego and the Id has scrupulously avoided it. When we translate radical ideas like the superego into our common understanding, we reveal our assumed beliefs and values. In such a translation, the more distortion a concept suffers, the more it must represent a challenge to our ordinary way of thinking. This is the case with the popular emphasis on the ego and the id relative to the superego. What has been lost is the most radical discovery within this text.

Our failure to recognize how Freud theorizes the superego leaves us unable to contend with the moral crises that confront us today. We can see the catastrophic consequences in our contemporary relationship to the environment, for example. As our guilt about plastic in the oceans, carbon emissions, and other horrors increases, it augments our enjoyment of plastic and carbon rather than detracting from it. Using plastic ceases to be just a convenience and becomes a transgression, which gives us something to enjoy where otherwise we would just have something to use.

Enjoyment always involves a relationship to a limit. But in these cases, enjoyment derives from transgression, the sense of going beyond a limit. Our conscious feeling of guilt about transgression corresponds to an unconscious enjoyment that the superego augments. The more that environmental warnings take the form of directions from the superego, the more they create guilt without changing the basic situation. Far from limiting the enjoyment of our destructive desires, morality becomes, in Freud’s way of thinking, a privileged ground for expressing it, albeit in a disguised form. It turns out that what we think of as morality has nothing at all to do with morality.

The superego produces a sense of transgression and thereby supercharges our desire, turning morality into a way of enjoying ourselves. Picking up Freud’s discovery 50 years later, Jacques Lacan announces, “Nothing forces anyone to enjoy ( jouir ) except the superego. The superego is the imperative of jouissance—Enjoy!” All of our seemingly moral impulses and the pangs of conscience that follow are modes of obeying this imperative.

In this light, we might reevaluate the diagnosis of Donald Trump. If he seems unable to restrain himself and appears constantly preoccupied with finding enjoyment, this suggests that the problem is neither too much ego nor too much id. We should instead hazard the “wild psychoanalytic” interpretation that Trump suffers from too much superego. His preoccupation with enjoying himself—and never enjoying himself enough to find satisfaction—reflects the predominance of the superego in his psyche, making clear that the superego has nothing to do with actual morality, and everything with wanton immorality.

When we understand morality as a disguised form of enjoyment, this does not free us from morality. Instead, the discovery of the superego and its imperative to enjoy demands a new way of conceiving morality. Rather than being the vehicle of morality, the superego is a great threat to any moral action, because it allows us to believe that we are acting morally while we are actually finding a circuitous path to our own enjoyment. Contrary to the popular reading of the superego, authentic moral action requires a rejection of the superego’s imperatives, not obedience to them.

Morality freed from the superego would no longer involve guilt. It would focus on redefining our relationship to law. Rather than seeing law as an external constraint imposed on us by society, we would see it as the form that our own self-limitation takes. This would entail a change in how we relate to the law. If the law is our self-limitation rather than an external limit, we lose the possibility of enjoyment associated with transgression. One can transgress a law but not one’s own self-limitation.

In terms of the contemporary environmental crisis, we would conceive of a constraint on the use of plastic as the only way to enjoy using plastic, not as a restriction on this enjoyment. The limit on use would become our own form of enjoyment because the limit would be our own, not something imposed on us. The superego enjoins us to reject any limit by always pushing our enjoyment further. Identifying the law as our self-limitation provides a way of breaking with the logic of the superego and its fundamentally immoral form of morality.

Given what he chose as the title for the book— The Ego and the Id —it is clear that even Freud himself did not properly identify what was most radical in his discovery. He omitted the superego from the title at the expense of the ego and the id, even though his recognition of the superego and its role in the psyche represents the key insight from the book. In this sense, Freud paved the way for the popular misapprehension that followed.

What is missed or ignored by society often reveals what most unsettles it. Our commonly held beliefs and values might try to mute the disturbance caused by radical ideas like the superego, but they don’t eliminate their influence completely. By focusing on what Freud himself omits, we can uncover the insight in his work most able to help us think beyond the confines of traditional morality. The path of a genuine morality must travel beyond the superego.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

The Impact JSTOR in Prison Has Made on Me

Sex (No!), Drugs (No!), and Rock and Roll (Yes!)

Wild Saints and Holy Fools

Building Classroom Discussions around JSTOR Daily Syllabi

Recent posts.

- Elephants, Decadence, and LGBTQ Records

- The Huts of the Appalachian Trail

- On the Anniversary of Iceland’s Independence

- Nellie Bly Experiences It All

- Ford’s Striking Dagenham Women

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Sigmund Freud's Life, Theories, and Influence

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Keystone / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Psychoanalysis

- Major Works

- Perspectives

- Thinkers Influenced by Freud

- Contributions

Frequently Asked Questions

Psychology's most famous figure is also one of the most influential and controversial thinkers of the 20th century. Sigmund Freud, an Austrian neurologist born in 1856, is often referred to as the "father of modern psychology."

Freud revolutionized how we think about and treat mental health conditions. Freud founded psychoanalysis as a way of listening to patients and better understanding how their minds work. Psychoanalysis continues to have an enormous influence on modern psychology and psychiatry.

Sigmund Freud's theories and work helped shape current views of dreams, childhood, personality, memory, sexuality, and therapy. Freud's work also laid the foundation for many other theorists to formulate ideas, while others developed new theories in opposition to his ideas.

Sigmund Freud Biography

To understand Freud's legacy, it is important to begin with a look at his life. His experiences informed many of his theories, so learning more about his life and the times in which he lived can lead to a deeper understanding of where his theories came from.

Freud was born in 1856 in a town called Freiberg in Moravia—in what is now known as the Czech Republic. He was the oldest of eight children. His family moved to Vienna several years after he was born, and he lived most of his life there.

Freud earned a medical degree and began practicing as a doctor in Vienna. He was appointed Lecturer on Nervous Diseases at the University of Vienna in 1885.

After spending time in Paris and attending lectures given by the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, Freud became more interested in theories explaining the human mind (which would later relate to his work in psychoanalysis).

Freud eventually withdrew from academia after the Viennese medical community rejected the types of ideas he brought back from Paris (specifically on what was then called hysteria ). Freud went on to publish influential works in neurology, including "On Aphasia: A Critical Study," in which he coined the term agnosia , meaning the inability to interpret sensations.

In later years, Freud and his colleague Josef Breuer published "Preliminary Report" and "Studies on Hysteria." When their friendship ended, Freud continued to publish his own works on psychoanalysis.

Freud and his family left Vienna due to discrimination against Jewish people. He moved to England in 1938 and died in 1939.

Sigmund Freud’s Theories

Freud's theories were enormously influential but subject to considerable criticism both now and during his life. However, his ideas have become interwoven into the fabric of our culture, with terms such as " Freudian slip ," "repression," and "denial" appearing regularly in everyday language.

Freud's theories include:

- Unconscious mind : This is one of his most enduring ideas, which is that the mind is a reservoir of thoughts, memories, and emotions that lie outside the awareness of the conscious mind.

- Personality : Freud proposed that personality was made up of three key elements: the id, the ego, and the superego . The ego is the conscious state, the id is the unconscious, and the superego is the moral or ethical framework that regulates how the ego operates.

- Life and death instincts : Freud claimed that two classes of instincts, life and death, dictated human behavior. Life instincts include sexual procreation, survival and pleasure; death instincts include aggression, self-harm, and destruction.

- Psychosexual development : Freud's theory of psychosexual development posits that there are five stages of growth in which people's personalities and sexual selves evolve. These phases are the oral stage, anal stage, phallic stage, latent stage, and genital stage.

- Mechanisms of defense : Freud suggested that people use defense mechanisms to avoid anxiety. These mechanisms include displacement, repression, sublimation, and regression.

Sigmund Freud and Psychoanalysis

Freud's ideas had such a strong impact on psychology that an entire school of thought emerged from his work: psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis has had a lasting impact on both the study of psychology and the practice of psychotherapy.

Psychoanalysis sought to bring unconscious information into conscious awareness in order to induce catharsis . Catharsis is an emotional release that may bring about relief from psychological distress.

Research has found that psychoanalysis can be an effective treatment for a number of mental health conditions. The self-examination that is involved in the therapy process can help people achieve long-term growth and improvement.

Sigmund Freud's Patients

Freud based his ideas on case studies of his own patients and those of his colleagues. These patients helped shape his theories and many have become well known. Some of these individuals included:

- Anna O. (aka Bertha Pappenheim)

- Little Hans (Herbert Graf)

- Dora (Ida Bauer)

- Rat Man (Ernst Lanzer)

- Wolf Man (Sergei Pankejeff)

- Sabina Spielrein

Anna O. was never actually a patient of Freud's. She was a patient of Freud's colleague Josef Breuer. The two men corresponded often about Anna O's symptoms, eventually publishing the book, "Studies on Hysteria" on her case. It was through their work and correspondence that the technique known as talk therapy emerged.

Major Works by Freud

Freud's writings detail many of his major theories and ideas. His personal favorite was "The Interpretation of Dreams ." Of it, he wrote: "[It] contains...the most valuable of all the discoveries it has been my good fortune to make. Insight such as this falls to one's lot but once in a lifetime."

Some of Freud's major books include:

- " The Interpretation of Dreams "

- "The Psychopathology of Everyday Life"

- "Totem and Taboo"

- "Civilization and Its Discontents"

- "The Future of an Illusion"

Freud's Perspectives

Outside of the field of psychology, Freud wrote and theorized about a broad range of subjects. He also wrote about and developed theories related to topics including sex, dreams, religion, women, and culture.

Views on Women

Both during his life and after, Freud was criticized for his views of women , femininity, and female sexuality. One of his most famous critics was the psychologist Karen Horney , who rejected his view that women suffered from "penis envy."

Penis envy, according to Freud, was a phenomenon that women experienced upon witnessing a naked male body, because they felt they themselves must be "castrated boys" and wished for their own penis.

Horney instead argued that men experience "womb envy" and are left with feelings of inferiority because they are unable to bear children.

Views on Religion

Freud was born and raised Jewish but described himself as an atheist in adulthood. "The whole thing is so patently infantile, so foreign to reality, that to anyone with a friendly attitude to humanity it is painful to think that the great majority of mortals will never be able to rise above this view of life," he wrote of religion.

He continued to have a keen interest in the topics of religion and spirituality and wrote a number of books focused on the subject.

Psychologists Influenced by Freud

In addition to his grand and far-reaching theories of human psychology, Freud also left his mark on a number of individuals who went on to become some of psychology's greatest thinkers. Some of the eminent psychologists who were influenced by Sigmund Freud include:

- Alfred Adler

- Erik Erikson

- Melanie Klein

- Ernst Jones

While Freud's work is often dismissed today as non-scientific, there is no question that he had a tremendous influence not only on psychology but on the larger culture as well.

Many of Freud's ideas have become so steeped in public awareness that we oftentimes forget that they have their origins in his psychoanalytic tradition.

Freud's Contributions to Psychology

Freud's theories are highly controversial today. For instance, he has been criticized for his lack of knowledge about women and for sexist notions in his theories about sexual development, hysteria, and penis envy.

People are skeptical about the legitimacy of Freud's theories because they lack the scientific evidence that psychological theories have today.

However, it remains true that Freud had a significant and lasting influence on the field of psychology. He provided a foundation for many concepts that psychologists used and continue to use to make new discoveries.

Perhaps Freud's most important contribution to the field of psychology was the development of talk therapy as an approach to treating mental health problems.

In addition to serving as the basis for psychoanalysis, talk therapy is now part of many psychotherapeutic interventions designed to help people overcome psychological distress and behavioral problems.

The Unconscious

Prior to the works of Freud, many people believed that behavior was inexplicable. He developed the idea of the unconscious as being the hidden motivation behind what we do. For instance, his work on dream interpretation suggested that our real feelings and desires lie underneath the surface of conscious life.

Childhood Influence

Freud believed that childhood experiences impact adulthood—specifically, traumatic experiences that we have as children can manifest as mental health issues when we're adults.

While childhood experiences aren't the only contributing factors to mental health during adulthood, Freud laid the foundation for a person's childhood to be taken into consideration during therapy and when diagnosing.

Literary Theory

Literary scholars and students alike often analyze texts through a Freudian lens. Freud's theories created an opportunity to understand fictional characters and even their authors based on what's written or what a reader can interpret from the text on topics such as dreams, sexuality, and personality.

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist who founded psychoanalysis. Also known as the father of modern psychology, he was born in 1856 and died in 1939.

While Freud theorized that childhood experiences shaped personality, the neo-Freudians (including Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, and Karen Horney) believed that social and cultural influences played an important role. Freud believed that sex was a primary human motivator, whereas neo-Freudians did not.

Sigmund Freud founded psychoanalysis and published many influential works such as "The Interpretation of Dreams." His theories about personality and sexuality were and continue to be extremely influential in the fields of psychology and psychiatry.

Sigmund Freud was born in a town called Freiberg in Moravia, which is now the Czech Republic.

It's likely that Freud died by natural means. However, he did have oral cancer at the time of his death and was administered a dose of morphine that some believed was a method of physician-assisted suicide.

Freud used psychoanalysis, also known as talk therapy, in order to get his patients to uncover their own unconscious thoughts and bring them into consciousness. Freud believed this would help his patients change their maladaptive behaviors.

Freud was the founder of psychoanalysis and introduced influential theories such as: his ideas of the conscious and unconscious; the id, ego, and superego; dream interpretation; and psychosexual development.

A Word From Verywell

While Freud's theories have been the subject of considerable controversy and debate, his impact on psychology, therapy, and culture is undeniable. As W.H. Auden wrote in his 1939 poem, "In Memory of Sigmund Freud":

"...if often he was wrong and, at times, absurd, to us he is no more a person now but a whole climate of opinion."

Grzybowski A, Żołnierz J. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) . J Neurol . 2021;268(6):2299-2300. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-09972-4

Bargh JA. The modern unconscious . World Psychiatry . 2019;18(2):225-226. doi:10.1002/wps.20625

Boag S. Ego, drives, and the dynamics of internal objects . Front Psychol . 2014;5:666. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00666

Meissner WW. The question of drive vs. motive in psychoanalysis: A modest proposal . J Am Psychoanal Assoc . 2009;57(4):807-845. doi:10.1177/0003065109342572

APA Dictionary of Psychology. Psychosexual development . American Psychological Association.

Waqas A, Rehman A, Malik A, Muhammad U, Khan S, Mahmood N. Association of ego defense mechanisms with academic performance, anxiety and depression in medical students: A mixed methods study . Cureus . 2015;7(9):e337. doi:10.7759/cureus.337

Shedler J. The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy . Am Psychol . 2010;65(2):98-109. doi:10.1037/a0018378

Bogousslavsky J, Dieguez S. Sigmund Freud and hysteria: The etiology of psychoanalysis . In: Bogousslavsky J, ed. Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience . S Karger AG. 2014;35:109-125. doi:10.1159/000360244

Grubin D. Young Dr. Freud . Public Broadcasting Service.

Gersick S. Penis envy . In: Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford T, eds. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences . Springer, Cham. 2017. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_616-1

Bayne E. Womb envy: The cause of misogyny and even male achievement? . Womens Stud Int Forum. 2011;34(2):151-160. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2011.01.007

Freud S. Civilization and Its Discontents . Norton.

Yeung AWK. Is the influence of Freud declining in psychology and psychiatry? A bibliometric analysis . Front Psychol. 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631516

Giordano G. The contribution of Freud’s theories to the literary analysis of two Victorian novels: Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre . Int J Engl Lit. 2020;11(2):29-34. doi:10.5897/IJEL2019.1312

APA Dictionary of Psychology. Neo-Freudian . American Psychological Association.

Hoffman L. Un homme manque: Freud's engagement with Alfred Adler's masculine protest: Commentary on Balsam . J Am Psychoanal Assoc . 2017;65(1):99-108. doi:10.1177/0003065117690351

Macleod ADS. Was Sigmund Freud's death hastened? . Intern Med J. 2017;47(8):966-969. doi:10.1111/imj.13504

Kernberg OF. The four basic components of psychoanalytic technique and derived psychoanalytic psychotherapies . World Psychiatry . 2016;15(3):287-288. doi:10.1002/wps.20368

Yale University. In Memory of Sigmund Freud .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Essay on Sigmund Freud and the Psychoanalytic Theory of Personality

Sigmund Freud was born on May 6, 1856, in the Czech Republic. His family moved to Leipzig and settled in Vienna, Austria, where Freud will be educated. His family is Jewish, but Freud himself does not practice the religion (Sigmund Freud, n.d.). Freud began his study of medicine in 1873 at the University of Vienna. Freud collaborated with a physician named Josef Breuer in treating patients with hysteria by recalling painful experiences (Sigmund Freud, n.d.). Freud would also draw inspiration from Jean Charcot, a French neurologist that tutored Freud. Freud would then return to Vienne and set up a clinic for his private practice. This series of events led Freud to develop his theory of psychoanalysis. Honestly, Freud was not drawn to medicine because he desired to engage in medical practice, but because he was intensely curious and passionate about human nature (Ellenberger, 1970). Meeting Both Breuer and Charcot influenced Freud’s eventual pursuit of developing a psychological theory.

A combination of his experiences heavily influenced Freud’s understanding of personality with patients, his self-analyzation of his dreams, and the readings from various sciences and humanities (Feist, Feist, & Roberts, 2018). All these culminated in Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of personality.

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory is a grand theory. This premise denotes that the theory he created covers a vast scope of the human personality and mind. Freud’s theory can be divided into several facets for a clearer understanding of the entire picture. First, there are the provinces of the mind: the conscious and the unconscious (Feist, Feist, & Roberts, 2018). Next, come the dynamics of personality. This premise refers to the sex and aggression impulse in everyone. Supplementary to this are the defense mechanisms. Last, Freud delves into the development of the individual. His theory posits the psychosexual stages of development.

To further understand the provinces of the mind, Freud introduced the conscious and the unconscious. The conscious is the mental awareness that a person has. The conscious plays a very minimal role in his theory. Freud focused on the unconscious in building his theory. The unconscious can be further divided into two other regions: the preconscious and the true unconscious. The difference between these two is that the preconscious contains thoughts that an individual is not conscious of but is readily available when needed. The unconscious contains an individual’s drives, urges, or instincts, not in a person’s awareness (Feist, Feist, & Roberts, 2018). The central theme of Freud’s theory lies within the unconscious. Freud claimed that a person’s unconscious motivates most of an individual’s words, feelings, and actions. He also stated that some parts of a person’s unconscious may have originated from their ancestors; he called this phylogenic endowment (Feist, Feist & Roberts, 2018). As the provinces of the mind have been established, Freud also hypothesized the id, ego, and superego. These elements interact with the outside world. The id, or the pleasure principle, lies entirely in the unconscious. The id is responsible for our desires, and its only function is to seek pleasure. The ego, or the reality principle, has all conscious, unconscious, preconscious elements (Feist, Feist, & Roberts, 2018). The ego is an individual’s method of communicating with the outside world. As the only region of the mind that has contact with the outside world, the ego is also considered the decision-making personality of a person (Feist, Feist, & Roberts, 2018). Last, the superego is the part of the mind that tackles the moral and ideal principles of the person. The superego resides in the unconscious and preconscious. The superego acts as a person’s moral conscience, informing the person on what is right and what is wrong. These three forces of the mind constantly struggle against each other and determine which force rules over a person. An example would be an individual with an overgrown id who may actively seek pleasurable stimuli.

Freud also tackles personality in his theory. Freud claimed that personality in man is our innate drive. The personality theory revolves around two significant drives: eros or sex and Thanatos or aggression (Feist, Feist, & Roberts, 2018). These drives originate from the id but are constantly checked by the ego. The eros, or libido, drive in a person pertains not only to genitalia satisfaction. Freud expresses that eros pertains to all pleasurable acts; this includes love. Thanatos, on the other hand, pertains to an individual’s aggression. The aim of the destructive drive, according to Freud, is to return the organism to an inorganic state. The inorganic condition that Freud is referring to is death. The ultimate aim of the aggressive drive is self-destruction (Feist, Feist, & Roberts, 2018). This premise may take on many forms, such as teasing, anger, or enjoying other people’s suffering.

Freud also included defense mechanisms in his theory. Defense mechanisms help the conscious avoid dealing with sexual and aggressive urges and defend itself from the anxiety that it brings (Feist, Feist, & Roberts, 2018). Examples of this are repression, denial, and projection.