New evidence of the benefits of arts education

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, brian kisida and bk brian kisida assistant professor, truman school of public affairs - university of missouri @briankisida daniel h. bowen dhb daniel h. bowen assistant professor, college of education and human development - texas a&m university @_dhbowen.

February 12, 2019

Engaging with art is essential to the human experience. Almost as soon as motor skills are developed, children communicate through artistic expression. The arts challenge us with different points of view, compel us to empathize with “others,” and give us the opportunity to reflect on the human condition. Empirical evidence supports these claims: Among adults, arts participation is related to behaviors that contribute to the health of civil society , such as increased civic engagement, greater social tolerance, and reductions in other-regarding behavior. Yet, while we recognize art’s transformative impacts, its place in K-12 education has become increasingly tenuous.

A critical challenge for arts education has been a lack of empirical evidence that demonstrates its educational value. Though few would deny that the arts confer intrinsic benefits, advocating “art for art’s sake” has been insufficient for preserving the arts in schools—despite national surveys showing an overwhelming majority of the public agrees that the arts are a necessary part of a well-rounded education.

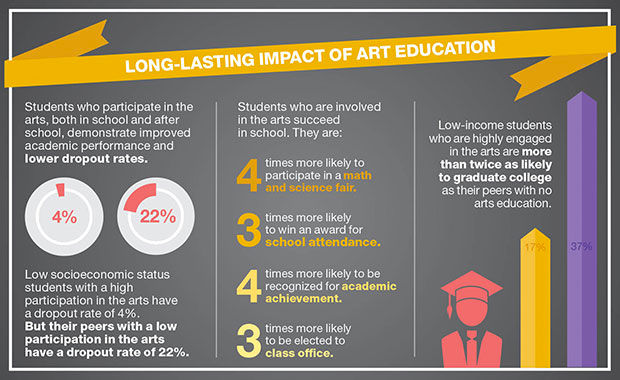

Over the last few decades, the proportion of students receiving arts education has shrunk drastically . This trend is primarily attributable to the expansion of standardized-test-based accountability, which has pressured schools to focus resources on tested subjects. As the saying goes, what gets measured gets done. These pressures have disproportionately affected access to the arts in a negative way for students from historically underserved communities. For example, a federal government report found that schools designated under No Child Left Behind as needing improvement and schools with higher percentages of minority students were more likely to experience decreases in time spent on arts education.

We recently conducted the first ever large-scale, randomized controlled trial study of a city’s collective efforts to restore arts education through community partnerships and investments. Building on our previous investigations of the impacts of enriching arts field trip experiences, this study examines the effects of a sustained reinvigoration of schoolwide arts education. Specifically, our study focuses on the initial two years of Houston’s Arts Access Initiative and includes 42 elementary and middle schools with over 10,000 third- through eighth-grade students. Our study was made possible by generous support of the Houston Endowment , the National Endowment for the Arts , and the Spencer Foundation .

Due to the program’s gradual rollout and oversubscription, we implemented a lottery to randomly assign which schools initially participated. Half of these schools received substantial influxes of funding earmarked to provide students with a vast array of arts educational experiences throughout the school year. Participating schools were required to commit a monetary match to provide arts experiences. Including matched funds from the Houston Endowment, schools in the treatment group had an average of $14.67 annually per student to facilitate and enhance partnerships with arts organizations and institutions. In addition to arts education professional development for school leaders and teachers, students at the 21 treatment schools received, on average, 10 enriching arts educational experiences across dance, music, theater, and visual arts disciplines. Schools partnered with cultural organizations and institutions that provided these arts learning opportunities through before- and after-school programs, field trips, in-school performances from professional artists, and teaching-artist residencies. Principals worked with the Arts Access Initiative director and staff to help guide arts program selections that aligned with their schools’ goals.

Our research efforts were part of a multisector collaboration that united district administrators, cultural organizations and institutions, philanthropists, government officials, and researchers. Collective efforts similar to Houston’s Arts Access Initiative have become increasingly common means for supplementing arts education opportunities through school-community partnerships. Other examples include Boston’s Arts Expansion Initiative , Chicago’s Creative Schools Initiative , and Seattle’s Creative Advantage .

Through our partnership with the Houston Education Research Consortium, we obtained access to student-level demographics, attendance and disciplinary records, and test score achievement, as well as the ability to collect original survey data from all 42 schools on students’ school engagement and social and emotional-related outcomes.

We find that a substantial increase in arts educational experiences has remarkable impacts on students’ academic, social, and emotional outcomes. Relative to students assigned to the control group, treatment school students experienced a 3.6 percentage point reduction in disciplinary infractions, an improvement of 13 percent of a standard deviation in standardized writing scores, and an increase of 8 percent of a standard deviation in their compassion for others. In terms of our measure of compassion for others, students who received more arts education experiences are more interested in how other people feel and more likely to want to help people who are treated badly.

When we restrict our analysis to elementary schools, which comprised 86 percent of the sample and were the primary target of the program, we also find that increases in arts learning positively and significantly affect students’ school engagement, college aspirations, and their inclinations to draw upon works of art as a means for empathizing with others. In terms of school engagement, students in the treatment group were more likely to agree that school work is enjoyable, makes them think about things in new ways, and that their school offers programs, classes, and activities that keep them interested in school. We generally did not find evidence to suggest significant impacts on students’ math, reading, or science achievement, attendance, or our other survey outcomes, which we discuss in our full report .

As education policymakers increasingly rely on empirical evidence to guide and justify decisions, advocates struggle to make the case for the preservation and restoration of K-12 arts education. To date, there is a remarkable lack of large-scale experimental studies that investigate the educational impacts of the arts. One problem is that U.S. school systems rarely collect and report basic data that researchers could use to assess students’ access and participation in arts educational programs. Moreover, the most promising outcomes associated with arts education learning objectives extend beyond commonly reported outcomes such as math and reading test scores. There are strong reasons to suspect that engagement in arts education can improve school climate, empower students with a sense of purpose and ownership, and enhance mutual respect for their teachers and peers. Yet, as educators and policymakers have come to recognize the importance of expanding the measures we use to assess educational effectiveness, data measuring social and emotional benefits are not widely collected. Future efforts should continue to expand on the types of measures used to assess educational program and policy effectiveness.

These findings provide strong evidence that arts educational experiences can produce significant positive impacts on academic and social development. Because schools play a pivotal role in cultivating the next generation of citizens and leaders, it is imperative that we reflect on the fundamental purpose of a well-rounded education. This mission is critical in a time of heightened intolerance and pressing threats to our core democratic values. As policymakers begin to collect and value outcome measures beyond test scores, we are likely to further recognize the value of the arts in the fundamental mission of education.

Related Content

Seth Gershenson

January 13, 2016

Brian Kisida, Bob Morrison, Lynn Tuttle

May 19, 2017

Joan Wasser Gish, Mary Walsh

December 12, 2016

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

Sofoklis Goulas, Isabelle Pula

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Elizabeth D. Steiner, Ashley Woo

136 Irving Street Cambridge, MA 02138

The Values of Arts Education

Arts education builds well-rounded individuals, arts education broadens our understanding of and appreciation for other cultures and histories, arts education supports social and emotional development, arts education builds empathy, reduces intolerance, and generates acceptance of others, arts education improves school engagement and culture, arts education develops valuable life and career skills, arts education strengthens community and civic engagement.

Arts education plays a vital role in the personal and professional development of citizens and, more broadly, the economic growth and social sustainability of communities. Its loss or diminution from the system would be incalculable. And yet, despite widespread support from parents and the general public, arts education still struggles to be prioritized by decision-makers. We believe one reason the arts are not prioritized stems from a disconnect between the perceived value of the arts and the real benefits experienced by students. We often heard in our outreach that the arts are misunderstood; one listening-session participant, a leader in arts education advocacy, noted that “decision-makers may have a flawed vision of what arts learning is in their heads, and they make decisions based on that vision.”

To remedy this, in this section we document the important attributes, values, and skills that come from arts education. We argue that arts education:

- Builds well-rounded individuals;

- Broadens our understanding and appreciation of other cultures and histories;

- Supports social and emotional development;

- Builds empathy, reduces intolerance, and generates acceptance of others;

- Improves school engagement and culture;

- Develops valuable life and career skills; and

- Strengthens community and civic engagement.

Many of these social and emotional benefits are intertwined with the priorities facing our school systems as we recover from the pandemic. These themes are enriched by a broad collection of voices—students, parents, arts educators, artists, and others—who told us about their experiences with arts education and how they have benefited.

“Though I personally have enjoyed and benefited tremendously from arts education, it is in my role as parent that I see most poignantly the power of arts education. I have seen my children think, feel, and connect through the arts in ways exponentially more powerful than they could without. When we moved to a community which did not support art education . . . I not only saw my own children struggle socially, emotionally, and academically; but also saw the devastating effects on the youth community. I am delighted now, in a new community, to see my children perform in musical and theatrical productions as well as to develop habits of inquiry, resourcefulness, and persistence through visual art. These experiences overshadow the toll that lack of arts opportunities took. Yet I grieve for those who do not have such access.”

—erin, parent, camdenton, missouri.

Similar to math, science, or history, the arts are a way of knowing and understanding the world and the complexity of human experience. Arts education builds an appreciation for the arts, and provides students with an introduction to artistic disciplines, techniques, and major movements that serves as a foundation for lifelong engagement. As such, the arts should not be viewed as a frill or subservient to other disciplines. Knowledge of the Renaissance, the Harlem Renaissance, pottery crafting techniques, or the fundamentals of perspective and design holds no less value than knowing the chemical formula for photosynthesis or how to calculate the circumference of a circle. And for many, it will mean much more. Indeed, research from the National Endowment for the Arts ( NEA ) found that childhood arts exposure is the number one predictor of arts participation as an adult. 37 Without that exposure, this window to the world remains hidden.

“I married a humanities professor, poet, and semiprofessional musician who had been saved by music as a child and had the opportunity to grow up playing in the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra. This of course meant that our house has been filled with music and musicians forever. . . . When it came time for our children to play instruments, my husband steered them toward instruments that would complete his future jazz trio. He was still on the trumpet, my son emerged as the piano player, and my daughter was on the upright bass. When they were small, they would pretend or struggle through, but last year before my husband Greg died unexpectedly, there they were playing “All Blues” by Miles Davis in the trio he envisioned. When they are feeling down or need to remember him, they go back to their instruments without prompting and just play. . . . [Art] becomes a means to connect and remember.”

— dr. maria trent, physician-scientist, maryland.

- 37 Rabkin and Hedberg, Arts Education in America .

Alongside the deeper insights into the world that can come from the arts, they also provide a vital link to the past. Art spans time and space and opens a window into experiences distant from us. From the cave paintings of Lascaux to Hokusai’s The Great Wave to Lin Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton , the arts document the richness of human history, preserved for future generations to contemplate and build upon. Arts education uniquely gives students the opportunity to engage with the past in a way that brings history to life and goes beyond textbooks. Expanding the curriculum beyond the Western-centric canon furthers these opportunities for deeper understanding and appreciation across cultures. Research shows that arts education not only increases historical knowledge but also historical empathy, opening up a deep understanding of what it was like to live in different times and places. 38

Art can also offer a way to preserve the cultural heritage of marginalized communities by engaging communities whose histories and culture have been suppressed or forgotten. Jamaica Osorio, an artist and scholar, told us that in her Hawaiian immersion school, arts were deeply integrated:

“So, when we studied literature, we studied these ancient mo‘olelo —these stories, histories, and literatures, and these songs of our kūpuna —of our ancestors—and that was the primary document. . . . I’ve devoted my life to the study of Hawaiian literature and, in particular, literature in Hawaiian, and have devoted my work to trying to represent these texts through poetry in a way that will be relevant and resonant with the people of my generation, who may feel—for whatever reason—distanced or disconnected from that archive.”

At every stage and in every school, the connections the arts open to the past can help deepen a child’s understanding of the world.

“The art classroom is a perfect place to introduce students to a world beyond their own. Through art-historical experiences, students can connect past and present events, realize that history is explored and experienced through art, and appreciate the struggles and triumphs of times they have not lived through.”

—jessica, visual arts educator, altoona, pa.

- 38 Brian Kisida, Laura Goodwin, and Daniel H. Bowen, “ Teaching History through Theater: The Effects of Arts Integration on Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes ,” AERA Open , January 2020; and Greene, Kisida, and Bowen, “Educational Value of Field Trips.”

Arts education is also a key ingredient in social and emotional learning, a growing priority for education policy-makers over the past decade. 39 The arts facilitate personal and emotional growth by providing opportunities for students to reflect on who they are and who they want to be. Artistic works expose students to deep personal perspectives and intimate experiences, and through these experiences students find new ways to see themselves and their role in the world. It is not surprising that many adults can reference key pieces of literature, poetry, and other artworks that have helped define who they are.

Similarly, the process of making art necessitates the formation of one’s own perspective. The need to then share that perspective gives students space to form and refine their own voice. Different arts disciplines provide distinct opportunities for students to learn to express themselves. For instance, Irishia Hubbard, a dance teacher with the Turnaround Arts Network in Santa Ana, California, works with middle school students (grades 6–8) on the dance team. After journaling and talking about experiences of immigration and borders, her students produce, rehearse, and perform a dance exploring those feelings. Ashley, an eighth-grade student, described the experience, observing that “this dance means a lot to me, because at one point in my life I was separated from my brother and my dad.” Stephanie Phillips, the Santa Ana superintendent, added, “they have absolutely blossomed, as performers, but also as expressive advocates of themselves; they are now talking about things that are of concern to them and learning to express them, not only artistically, but in simple terms of how to have collaborative and very constructive conversation.” Chiamaka, an eleventh-grader from North Carolina who shared her perspective with us, stated simply that art “has given me a voice.”

Carly, a twelfth-grader with cerebral palsy from New Mexico, told us that arts education helped her “step outside of my comfort zone.” Finding a place in theater gave her a place to be seen:

“I’ve had a lot of people tell me . . . that they wouldn’t cast me, that they wouldn’t do it, it would be too hard on me, and they basically didn’t want to risk it. And then I finally found a director who gave me my first lead role, and just being up there and realizing that everybody’s looking at me and they’re not just seeing a disability, they’re seeing me expressing myself in the way I loved. I just never wanted them to stop seeing me that way.”

“It is not an overstatement to say the arts saved my life. My arts education, particularly in high school, centered on vocal music, forensic theater, and traditional performance theater. Each of these inherently came with a community of people who—while all similar—taught one another to see the world through myriad eyes. I gained a siblinghood who provided creative and constructive outlets for the breadth of human emotion; I learned what it meant to be an ally; I gained the confidence to be myself and the assurance that ‘myself’ is exactly who the world needs me to be.”

—lynnea, arts administrator, suburban tennessee.

- 39 The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning is one key instance of this. They define social and emotional learning as “the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions” ( https://casel.org/what-is-sel/ ).

The arts have long had a role in bending the arc of history toward justice. Just as the arts help us better understand ourselves, they also improve our ability to empathize with others. As Mary Anne Carter, the twelfth chair of the NEA recently noted, “The arts are a powerful antidote against bigotry and hate. The arts can build bridges, promote tolerance, and heal social divisions.” 40 We have all witnessed the power of the arts to promote understanding, from the ability of plays like Angels in America to challenge how audiences saw AIDS , to the unifying role that music played in the Civil Rights Movement.

Arts education exposes students to a greater diversity of opinions and ideas. This in turn can challenge preconceived notions of others and build greater empathy and acceptance. A growing body of research confirms the power of arts education to contribute to these prosocial behaviors. 41 For instance, research in California public schools revealed that drama activities prompted students to take on different perspectives through interpreting a character’s motivation. 42 Loie, an eighth-grade student from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, told us that through her experiences with arts courses, “I’m able to express my opinions and be open to other people’s opinions. . . . I can look at their experience and learn from it. . . . There’s different ways of looking at things.”

“Effectively communicating that we understand what another person is feeling is one of the greatest gifts we can give to another human being . . . from listening to even just a single movement of music by a classical composer . . . abstract, wordless music can transcend time and ethnicity in its ability to communicate the full depth of human emotion.”

— george, teaching artist (music), bedminster, nj.

- 40 “#WednesdayMotivation,” June 24, 2020, #WednesdayMotivation: Mary Anne Carter on the Power of the Arts, National Endowment for the Arts.

- 41 Sara Konrath and Brian Kisida, “Does Arts Engagement Increase Empathy and Prosocial Behavior? A Review of the Literature,” in Engagement in the City: How Arts and Culture Impact Development in Urban Areas , ed. Leigh N. Hersey and Bryna Bobick (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2021).

- 42 Liane Brouillette, “ How the Arts Help Children to Create Healthy Social Scripts: Exploring the Perceptions of Elementary Teachers ,” Arts Education Policy Review 111 (1) (2009): 20–21.

In a perfect world, students would enthusiastically look forward to coming to school. Educators are continually searching for ways to excite students about learning, combat chronic absenteeism, and curb the dropout rate. Engaging students in their own learning process is not only important for the time they spend in school but is essential to inculcating a lifelong love of learning and discovery.

Arts education is particularly well-suited to combat complacent attitudes toward learning. Indeed, research finds that students enrolled in arts courses have improved attendance, and the effects are larger for students with a history of chronic absenteeism. 43 Related research finds that arts learning generates spaces “full of student passion and apprenticeship style learning.” 44 The arts provide students a sense of ownership and agency over their own education. Students who enroll in a theater class, for example, gain a sense of purpose as they work toward opening night, and they build a community with their peers and teachers as they work together toward a common goal. Alex, an arts educator from Chicago, illustrated it this way:

“I believe that it is imperative for students to have voice and choice in their learning . . . students are more invested and take more risks when they create from the point of what is personal or important to them. . . . When students discover an idea or medium that speaks to them, they become more invested in learning and creating.”

Arts education also improves school engagement by providing different ways of accessing educational content. In a nation with over 50 million K –12 students, schools need a broad set of entry points for students to discover what kinds of learning environments work best for them. Jessica, a visual arts educator from Altoona, Pennsylvania, told us, “Students who may be low achievers in the academic classroom are some of my highest functioning students in the art room. . . . Everyone has strengths and everyone has weaknesses.” Not all students learn the same way, and art offers students with different learning styles another mechanism by which to absorb content and ideas. Jensen, an eleventh-grader from Washington state, told us, “from taking art classes I learned that having a different pace or approach to things is okay, and everyone learns and makes things in their own way. And that really helped with my self-esteem in school and outside of school.”

“I really disliked school and thought it was an incredible waste of time and looked forward to turning sixteen so that I could drop out like my Dad had done. The one thing that kept me in school was that I really loved band. I couldn’t see myself leaving the band behind, and so I stayed in school and even went to college. Not as a music major, but I continued to play in the College Marching and Concert bands. Now I work in Arts Education and hope that the artists we send to perform in schools and teach workshops are finding the students who are bored and dislike school and are giving them a reason to stay.”

—donnajean, arts educator, kendall park, nj.

Finally, the collaborative nature of the arts can build strong bonds among students, teachers, and parents, thus contributing to a more positive school culture. Teachers in schools with higher levels of arts education report greater parental involvement. 45 Erin, the parent from Missouri, relayed this compelling story about her children:

“This year [2020] was, as was the case for most of us around the world, a particularly tough year. My children were uncharacteristically seized with anxiety and dread about returning to school. One child in particular, typically a bright and eager student, despaired the return. It was not her friends but her art teachers—and the experiences they collaboratively created—that completely turned her attitude around. For that, I am forever grateful; for in the midst of dread and despair, art helps us to meet and support one another.”

“I grew up in a dysfunctional family . . . and I wrote about all the loss and damage of growing up in a dysfunctional family—the abuse and the neglect. And when I was a senior in high school, the very last thing that happened before I graduated was someone turned in one of my poems, and it won the poetry contest for the [school’s literary magazine]. It was profound. I wasn’t this zero nothing, and my work had merit. And it planted a seed that really navigated the rest of my life. . . . That little measure of recognition really formed everything, and I’m so grateful for everybody that made that literary magazine exist in this enormous high school. There were lots of sports and lots of clubs and that tiny literary magazine was, I assume for other writers like me, a life raft—a lifesaving raft.”

—mary agnes antonopoulos, copywriter, monroe, ny.

- 43 Bowen and Kisida, The Arts Advantage .

- 44 Jal Mehta, “ Schools Already Have Good Learning, Just Not Where You Think ,” Education Week , February 8, 2017.

- 45 Bowen and Kisida, The Arts Advantage .

Arts education also imparts valuable skills that will serve students in their lives and careers: observation, problem-solving, innovation, and critical thinking. 46 Participating in the arts can also improve communication skills, generate self-esteem, teach collaboration, and increase confidence. Such skills are valuable to artists and non-artists alike. For those interested in careers in the arts, from musicians to music producers, fine artists to graphic designers, arts courses provide an opportunity for career exploration and a foundation for career choices.

“Arts education played an important role in developing my skills and preparing me for that dreadful thing we call ‘adulthood.’ This may be cliche, but it’s true when I say it’s taught me important life skills such as thinking outside the box, being able to adapt quickly to situations, developing that camaraderie with people, and being comfortable in my own skin. Improv is definitely something I benefited from in my arts education. The number one rule of improv is to never say no but always say, ‘Yes, and. . . .’ That’s proven to be key to my success in life—personally and professionally. My arts education taught me how to be confident . . . flexible, creative, how to be a team player, and when to listen and talk. I can’t say for certain if I’d be as successful in my personal or professional development without my arts education, and I certainly appreciate what it’s done for me and don’t take it for granted.”

—aaron kubey, director of artistic sign language, washington, d.c..

Moreover, specific skills covered through arts education directly affect a broad swath of careers outside the core arts careers. Stephanie, an arts educator in suburban California, told us that her main goal in teaching art is “developing creativity and innovation.” From the interior designer relying on color theory to the architect who uses 3 D software to the engineer who incorporates elements of design, the skills embodied in arts education have wide applications. Jensen, an eleventh-grader who had studied at a specialized arts school and wants to pursue a career in medicine, told us, “a lot of the things I learned are skills I would use interacting with people and the world around me, and not just a sheet of paper or something that’s on my computer.” The far-reaching benefits of arts education include work ethic and resilience. As Jade Elyssa A. Rivera, who works in arts education policy and advocacy in California, shared, “The arts were an essential part of my upbringing. It is where I learned the meaning of hard work. It is where I learned that, even in the face of systemic injustices, my dreams are achievable. It is where I learned that, if I just roll up my sleeves and do the work, anything is possible.”

“While I continued to love art and teaching, in 2015 I made a drastic career shift and left the field of education. I found myself working in the private sector for a large retailer doing ISD [instructional systems design] work . . . thinking this would be a new path. While it did end up being a new path, it wasn’t as far from my background as I thought it would be. It was only a few months into this work that I found myself applying for and being accepted for a role based on the fine arts and education background I had been pursuing previously. While it was applied in a corporate sense, I was given the opportunity to photograph, film, and design training for retail employees directly applying principles I had learned throughout my arts education and career for an entirely new and unique audience. Beyond aesthetics and design, I’ve been able to apply the critical thinking skills, view problems from multiple sides, draft ideas, and quickly revise or shift. Many of these were formed through learning about art. . . . Without art and its impact on my life, I would not have the perspective, experiences, or career I do today.”

—ian, former arts educator, arkansas.

- 46 NGA Center for Best Practices, The Impact of Arts Education on Workforce Preparation (Washington, D.C.: National Governors Association, May 2002).

Finally, arts education can lead to socially empowered and civically engaged youths and adults. Equipped with the knowledge, habits, values, and skills provided through arts education, students are well-prepared to promote democratic values and contribute to the health of our economy and culture. 47 Arts education experiences offer community and civic contributions with the potential for positive transformations. For example, Grace, an arts educator in Lake Arrowhead, California, described how, “Over the course of my 27 years of teaching art I have promoted community and civic engagement with schoolwide murals on and off campus.”

Strengthening and valuing communities through the arts also occurs through collaborations between schools and communities. Leslie Imse, a music educator and chair of the Farmington Public Schools K -12 music department, living in Simsbury, Connecticut, shared an example of her school’s engagement with seniors in their community: 48

“In addition to performing at our school concerts, student musicians perform regularly in their school and town community. After the 2008 recession, the music department realized that the population that was hurting the most were the senior citizens in our community. We created a new event for the senior citizens, bringing them to our school cafeteria for a free meal and ‘a show.’ It was so popular in town that we annually have one ‘Senior Citizen Cafe’ in the fall and one in the spring. The relationships that students have made with the senior citizens are meaningful, as our musicians not only prepare music for the older generation but also wait tables and converse with the seniors. . . . This is one of the many service activities that the music department connects with the community.”

Arts education also provides opportunities for students to engage with current events both close to the lives of students and far away. For instance, at Clarence Edwards Middle School in Boston, the eighth-grade visual arts class run by Shari Malgieri follows the news—international, national, and popular—over the entire year and then collaborates on a comprehensive mural about the year as seen by the students. 49

“As a person who facilitates arts-in-education residencies, I’ve watched people of all ages benefit from the arts. . . . I’ve seen teenagers weld beautiful fish from trash they cleaned from a stream to educate the public about the ways pollution threatens wildlife, and heard them say how meaningful it is to know that their work will make a difference. I’ve watched the joy on the faces of folks with intellectual disabilities as they crafted panels for a group quilt that would go on a city-wide tour. . . . Nearly every day of my working life is an encounter with the ways arts in education pulls people together, ignites change (both personal and social), and gives life to deep and lasting happiness.”

—marci, arts facilitator, lancaster, pa.

These aspects of community and civic engagement, in concert with the other benefits of arts education, prepare students to become effective citizens who are socially empowered and civilly engaged adults, equipped with the tools to contribute their own voices to the ever-evolving story of America. As Amanda Gorman, the nation’s first youth poet laureate, expressed, “All art is political. The decision to create, the artistic choice to have a voice, the choice to be heard, is the most political act of all.” 50 How we respond to the deficit in arts education in America—how we prepare our future leaders to refine and use their own voices—will help define our course for generations to come.

- 47 Arts education can also serve as a prevention, intervention, transition, and healing experience for students in the juvenile justice system, where barriers to arts engagement often exist. The Education Commission of the States suggests expanding the arts for incarcerated youth, who disproportionately lack access when removed from their communities and schools. Education Commission of the States, Engaging the Arts across the Juvenile Justice System (Denver: Education Commission of the States, April 2020).

- 48 Many other types of intergenerational arts programs exist that provide opportunities for participants from different generations to develop positive reciprocal relationships. These interactions begin to break down existing stereotypes of ageism and offer a pathway to healthy aging and meaningful community relationships. Intergenerational public schools in Cleveland, Ohio, have been in operation since 2000 and emphasize the importance of experience and relationship-based learning. Adults and elders volunteer at schools, where they engage with young people through the arts and other learning opportunities. Examples of such intergenerational arts projects span multiple disciplines, including theatre (see, for example, Richard Chin, “ This ‘Peter Pan’ Production Truly Is Ageless ,” NextAvenue , April 8, 2016), visual art, and ecology (for example, “ Students’ Concerns for Nature Featured in Art Show ,” Sauk Trail Wolves , n.d.). Many other resources are located on the Generations United website , a national organization that fosters intergenerational learning relationships, linking schools with elders in a variety of sites across the country.

- 49 David Farbman, Dennie Palmer Wolf, and Diane Sherlock, Advancing Arts Education through an Expanded School Day: Lessons from Five Schools (Boston: National Center on Time and Learning, June 2013), 19–31.

- 50 Carren Jao, “ Poetry Is Political: Amanda Gorman’s America ,” KCET , January 20, 2021.

National Endowment for the Arts

- Grants for Arts Projects

- Challenge America

- Research Awards

- Partnership Agreement Grants

- Creative Writing

- Translation Projects

- Volunteer to be an NEA Panelist

- Manage Your Award

- Recent Grants

- Arts & Human Development Task Force

- Arts Education Partnership

- Blue Star Museums

- Citizens' Institute on Rural Design

- Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network

- GSA's Art in Architecture

- Independent Film & Media Arts Field-Building Initiative

- Interagency Working Group on Arts, Health, & Civic Infrastructure

- International

- Mayors' Institute on City Design

- Musical Theater Songwriting Challenge

- National Folklife Network

- NEA Big Read

- NEA Research Labs

- Poetry Out Loud

- Save America's Treasures

- Shakespeare in American Communities

- Sound Health Network

- United We Stand

- American Artscape Magazine

- NEA Art Works Podcast

- National Endowment for the Arts Blog

- States and Regions

- Accessibility

- Arts & Artifacts Indemnity Program

- Arts and Health

- Arts Education

- Creative Placemaking

- Equity Action Plan

- Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)

- Literary Arts

- Native Arts and Culture

- NEA Jazz Masters Fellowships

- National Heritage Fellowships

- National Medal of Arts

- Press Releases

- Upcoming Events

- NEA Chair's Page

- Leadership and Staff

- What Is the NEA

- Publications

- National Endowment for the Arts on COVID-19

- Open Government

- Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- Office of the Inspector General

- Civil Rights Office

- Appropriations History

- Make a Donation

Why Arts Education Matters

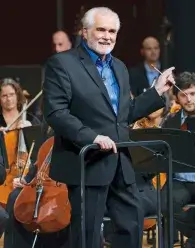

Judith Light. Photo by Jonathan Stoller

Recent Blog Posts

Embracing Your Voice: A Conversation with 2024 Poetry Out Loud National Champion Niveah Glover

Notable Quotable: Kathy Roth-Douquet of Blue Star Families

Celebrating Jewish American Heritage Month!

Stay connected to the national endowment for the arts.

- Our Mission

Creativity and Academics: The Power of an Arts Education

The arts are as important as academics, and they should be treated that way in school curriculum. This is what we believe and practice at New Mexico School for the Arts (NMSA). While the positive impact of the arts on academic achievement is worthwhile in itself, it's also the tip of the iceberg when looking at the whole child. Learning art goes beyond creating more successful students. We believe that it creates more successful human beings.

NMSA is built upon a dual arts and academic curriculum. Our teachers, students, and families all hold the belief that both arts and academics are equally important. Our goal is to prepare students for professional careers in the arts, while also equipping them with the skills and content knowledge necessary to succeed in college. From our personal experience ( and research ), here are five benefits of an arts education:

1. Growth Mindset

Through the arts, students develop skills like resilience, grit, and a growth mindset to help them master their craft, do well academically, and succeed in life after high school. (See Embracing Failure: Building a Growth Mindset Through the Arts and Mastering Self-Assessment: Deepening Independent Learning Through the Arts .) Ideally, this progression will happen naturally, but often it can be aided by the teacher. By setting clear expectations and goals for students and then drawing the correlation between the work done and the results, students can begin to shift their motivation, resulting in a much healthier and more sustainable learning environment.

For students to truly grow and progress, there has to be a point when intrinsic motivation comes into balance with extrinsic motivation. In the early stages of learning an art form, students engage with the activity because it's fun (intrinsic motivation). However, this motivation will allow them to progress only so far, and then their development begins to slow -- or even stop. At this point, lean on extrinsic motivation to continue your students' growth. This can take the form of auditions, tests, or other assessments. Like the impact of early intrinsic motivation, this kind of engagement will help your students grow and progress. While both types of motivation are helpful and productive, a hybrid of the two is most successful. Your students will study or practice not only for the external rewards, but also because of the self-enjoyment or satisfaction this gives them.

2. Self-Confidence

A number of years ago, I had a student enter my band program who would not speak. When asked a question, she would simply look at me. She loved being in band, but she would not play. I wondered why she would choose to join an activity while refusing to actually do the activity. Slowly, through encouragement from her peers and myself, a wonderful young person came out from under her insecurities and began to play. And as she learned her instrument, I watched her transform into not only a self-confident young lady and an accomplished musician, but also a student leader. Through the act of making music, she overcame her insecurities and found her voice and place in life.

3. Improved Cognition

Research connects learning music to improved "verbal memory, second language pronunciation accuracy, reading ability, and executive functions" in youth ( Frontiers in Neuroscience ). By immersing students in arts education, you draw them into an incredibly complex and multifaceted endeavor that combines many subject matters (like mathematics, history, language, and science) while being uniquely tied to culture.

For example, in order for a student to play in tune, he must have a scientific understanding of sound waves and other musical acoustics principles. Likewise, for a student to give an inspired performance of Shakespeare, she must understand social, cultural, and historical events of the time. The arts are valuable not only as stand-alone subject matter, but also as the perfect link between all subject matters -- and a great delivery system for these concepts, as well. You can see this in the correlation between drawing and geometry, or between meter and time signatures and math concepts such as fractions .

4. Communication

One can make an argument that communication may be the single most important aspect of existence. Our world is built through communication. Students learn a multitude of communication skills by studying the arts. Through the very process of being in a music ensemble, they must learn to verbally, physically, and emotionally communicate with their peers, conductor, and audience. Likewise, a cast member must not only communicate the spoken word to an audience, but also the more intangible underlying emotions of the script. The arts are a mode of expression that transforms thoughts and emotions into a unique form of communication -- art itself.

5. Deepening Cultural and Self-Understanding

While many find the value of arts education to be the ways in which it impacts student learning, I feel the learning of art is itself a worthwhile endeavor. A culture without art isn’t possible. Art is at the very core of our identity as humans. I feel that the greatest gift we can give students -- and humanity -- is an understanding, appreciation, and ability to create art.

What are some of the benefits of an arts education that you have noticed with your students?

New Mexico School for the Arts

Per pupil expenditures, free / reduced lunch, demographics:.

The Benefits of Arts Education for K-12 Students

While arts programs often fall victim to budget cuts, they can be an important contributor to students' success at school.

Benefits of Arts Education

Getty Images

Just like after-school sports programs allow students to learn skills not necessarily taught in the classroom, like teamwork and self-discipline, the arts provide students with broad opportunities for growth outside of strictly academic pursuits.

Your child’s art class involves a lot more than just the Crayola marker scribble-scrabble that will end up hanging on your refrigerator.

“Good arts education is not about the product,” says Jamie Kasper, director of the Arts Education Partnership and a former music teacher. “It is about the process of learning.”

Policymakers, school administrators and parents alike may overlook the significance of arts education, but these programs can be a crucial component of your child’s school life. Whether they're practicing lines for a school play or cutting up magazine scraps for a collage, children can use art to tap into their creative side and hone skills that might not be the focus of other content areas, including communication, fine motor skills and emotional intelligence.

“Sometimes folks who are not involved in the arts focus on the product without realizing that that is not the most important part of what we do,” Kasper says.

While arts programs often fall victim to budget cuts, they can be an important contributor to students' overall success at school. Arts education can help kids:

- Engage with school and reduce stress.

- Develop social-emotional and interpersonal skills.

- Enrich their experiences.

- Handle constructive criticism.

- Bolster academic achievement.

- Improve focus.

Engage With School and Reduce Stress

Kasper says she often hears from other educators that art programs are one of the main factors that motivate children to come to school.

"If they don't want to come to school, you're never going to get them," she says. "So why wouldn't you do that thing that makes them want to come to school, that also teaches them these really great skills?"

Michelle Schroeder, the president of the New York State Art Teachers Association and a high school animation teacher, seconds this. She says the arts allow students an opportunity to have fun throughout the day without having to worry so much about the stressors of other content areas. And this is backed by research, too – some studies have shown that the arts, from drama to dance , can have therapeutic effects.

"It's that part of their day where they can have fun and just play with materials, and really not have to worry about the answers on their tests," Schroeder says.

Develop Social-Emotional and Interpersonal Skills

Participating in arts programs – particularly those that focus on more collaborative forms like theater and music – is a good way for students to sharpen their communication and social-emotional skills, experts say.

Camille Farrington, managing director and senior research associate at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, says art classes offer students opportunities to interact with their fellow students in a constructive and creative manner, a process that fuels their social and emotional development. For example, one study published in the Journal of Primary Prevention found that students in low-income schools who participated in an after-school dance program tended to experience heightened self-esteem and social skills.

Building those skills is more important than ever after the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic, says Denise Grail Brandenburg, arts education specialist and team lead at the National Endowment for the Arts. “Arts education can support the social and emotional learning needs of students," Brandenburg wrote in an email, "including helping students learn to manage their emotions and have compassion for others.”

Kasper also says that even with somewhat solitary artistic endeavors like painting or drawing, the act of perfecting one’s technique allows students to come up with creative ways to express and communicate their viewpoints.

“You teach the fundamentals of making the art ... – your instrument, your voice, your body in motion, painting, sculpture, whatever it is – so that students can then take those skills and use them to communicate more effectively,” she says.

Enrich Their Experiences

Human beings have practiced various art forms to express themselves since the dawn of their existence.

“Art immensely improves and enriches the lives of young people,” Farrington says. “It's a core part of being a human being and human history and culture.”

For kids in low-income neighborhoods, where residents may have less access to art and cultural resources that can improve quality of life , school arts programs are especially important. An analysis from the National Endowment for the Arts, drawing on data from four longitudinal studies, found that students with high levels of arts involvement had more positive outcomes in a variety of areas, from high school graduation rates to civic participation.

Just like after-school sports programs allow students to learn skills not necessarily taught in the classroom, like teamwork and self-discipline, Farrington says the arts provide students with broad opportunities for growth outside of strictly academic pursuits.

"One of the things that's really critical to young people of all ages ... is the opportunity to explore a wide variety of different kinds of activities," Farrington says. "Some of them are going to gravitate to one thing, and some are going to gravitate to another thing, but they can't gravitate to them if they've never experienced them."

Handle Constructive Criticism

Unlike many other school subjects, in which questions often have one specific answer, the arts allow for students to come up with a nearly unlimited variety of final products. This means that art teachers often give feedback a little bit differently, particularly with older students.

“They're teaching something and then immediately asking students to demonstrate that skill in a really authentic way, which is different from going to teach something and three months later giving students a test,” Kasper says.

Schroeder says that art teachers typically provide their students with highly individualized, constructive criticism. This allows students to learn how to gracefully receive a critique and respond to it, she says, explaining how and why they developed the artwork that they did.

“In so much of their careers and their future, people are either going to criticize or they're going to suggest improvements, and our students need to become comfortable with receiving feedback from other people,” she says. “So many experiences that they’ll have in an art classroom give them the opportunity to feel what it’s like to have someone question them. There's so much dialogue that happens in the classroom.”

Bolster Academic Achievement

While Farrington says that making art for art’s sake ought to be sufficient justification for school arts programs, research has also shown that arts education can lead to academic gains.

For example, a 2005 study on the impact of a comprehensive arts curriculum in Columbus, Ohio, public schools found that students with the arts program scored higher on statewide tests in math, science and citizenship than students from control schools. This effect was even greater for students from low-income schools. In the NEA analysis, socially and economically disadvantaged children with significant arts education had better academic outcomes – including higher grades and test scores and higher rates of graduation and college enrollment – than their peers without arts involvement.

Different disciplines also provide their own specific cognitive benefits – for example, participating in dance has been shown to sharpen young children's spatial awareness , while making music can help students develop their working memory .

Improve Focus

In addition to the specific benefits of each individual art practice, Kasper says that across the board, the arts are a good way for students to learn impulse control.

Intuitively, it makes sense that the act of concentrating in order to perfect one's craft can help an individual develop the ability to focus closely on other things as well. Research has shown that training in the arts also helps students hone their ability to pay closer attention and practice self-control. In 2009, researchers at the Dana Foundation , which funds neuroscience research and programming, posited based on multiple studies that training in the arts stimulates and strengthens the brain's attention system.

"That's something that I think we forget that kids have to learn," Kasper says.

See the 2022 Best Public High Schools

Tags: public schools , parenting , K-12 education , art

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

Popular Stories

Best Colleges

College Admissions Playbook

You May Also Like

Choosing a high school: what to consider.

Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

Map: Top 100 Public High Schools

Sarah Wood and Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

States With Highest Test Scores

Sarah Wood April 23, 2024

Metro Areas With Top-Ranked High Schools

A.R. Cabral April 23, 2024

U.S. News Releases High School Rankings

Explore the 2024 Best STEM High Schools

Nathan Hellman April 22, 2024

See the 2024 Best Public High Schools

Joshua Welling April 22, 2024

Ways Students Can Spend Spring Break

Anayat Durrani March 6, 2024

Attending an Online High School

Cole Claybourn Feb. 20, 2024

How to Perform Well on SAT, ACT Test Day

Cole Claybourn Feb. 13, 2024

Author: Getty Education Institute for the Arts

Publication Year: 1996

Media Type: Report

How do we teach chiildren about a subject as fluid as art - a discipline that reflects every cultural change, from wars to fashion, ethnicity, and technology? To be meaningful to children, art that is old must connect with the art that makes up their world. When we recognize that art tells the story of humankind, the connection is easily made. Clothing, video games, and MTV, the galleries familiar to young people today, have their historical counterparts.

Art predates writing and provides a visual history that tells us how people dressed, what they ate, how they celebrated life, who their enemies were, what kind of governments they had, and how they buried their dead. Art is the tangible, visible evidence of all peoples around the globe. It can be carbon tested and scientifically documented.

In the long history of humankind, the art-making process has been an integral part of all societies, not a stand-alone enterprise. Given its universality to all learning, we may wonder how art came to be viewed as peripheral to education and a stepchild of public school curricula. The answer lies in the all-too-common view that art is nonfunctional, secular, and separate from society. Of course, it became irrelevant to the mainstream.

Above all else, learning about art from a global perspective will provide a basis for valuing difference. This is a critical issue for our times. Art provides a basis for international understanding like no other subject. Art is the story of humankind, and we are all participants in it.

CONTENTS Arts education for a changing world: An arts education can build students' competencies for life and for work in the 21st century.

Educating for tomorrow's jobs and life skills: Elliot Eisner, Professor of Education and Art, Stanford University, shares his perspective on the values and skills fostered by arts education.

The Arts: Dynamic partner in building strong schools: Ramon Cortines, Executive Director of the Pew Network for Standards-based reform, Stanford University, builds the case for quality arts education as fundamental to school reform.

Perspective: Arts Education for a lifetime of wonder: Dr. Gordon Gee and Dr. Constance Bumgarner Gee.

What kind of jobs? What kind of skills? James S. Houghton, Chairman of the National Skills Standards Board, and Delaine Eastin, California's State Superintendent of Public Instruction, examine the issues facing schools in equipping students with skills for tomorrow's workplace.

What's standard about arts education? Colorado Governor Roy Romer believes arts education is fundamental to producing graduates who meet the high standards demanded by today's world marketplace.

What are they saying about arts education and effective school reform? Leaders of education policy, school administration, and communities from across the nation comment on the critical role of arts education in improving schools.

The future of imagination: Historian, author and host of the PBS series The American Experience , David McCullough provides evidence and reasoning for arts education as key to America's progress.

Perspective: Learning about art from a global perspective: Jaune Quick-to-see Smith.

Arts & Intersections:

Categories: Arts Education

ADDITIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

Series Title:

PUBLISHER INFORMATION

Name: Getty Education Institute for the Arts (GEI) (defunct)

Website URL:

<strong data-cart-timer="" role="text"></strong>

- Arts Integration

Arts in the 21st Century Classroom 5 ways the arts connect to 21st century skills.

Lesson content.

Skills for the Future! The 21st century skills our students need—technology, communication, global awareness, critical thinking, problem-solving—can be readily integrated into arts lessons, and vice versa.

- Get real. Working artists of all kinds use computer technology and collaboration. Our students can do the same, using graphics programs to illustrate their works, creating digital videos, or sharing ideas about dance online.

- Work in the cloud. Use Web 2.0 tools like classroom wikis and shared documents in your arts teaching to encourage collaboration and technology literacy.

- Bring the world into the classroom. The Internet is an amazing source of performance and graphic arts information. Illustrate lessons and lectures with examples of art from around the world to increase global awareness.

- Stay open. Assign open-ended projects that encourage problem-solving, collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking. Art projects are perfect for this. Let students figure out how to paint a mural about electricity, choreograph a dance about chemical bonds, or stage an operetta of the life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Embrace interdisciplinary approaches. Jobs from the 20th century often involved doing the same thing all day, each worker doing a separate piece of the job alone. Today, collaboration and interdisciplinary work are the norm. They should be in the classroom, too. Art instruction belongs in the main classroom with reading, writing, and arithmetic to increase creativity throughout the entire school day.

Arts are Essential!

Current brain research confirms that rich context and multisensory instruction make even simple facts easier to learn and remember. When we’re trying to teach creativity, problem-solving, and collaboration, we can’t expect to succeed with multiple choice quizzes. The arts are more essential than ever in education.

Rebecca Haden

Joanna McKee

October 18, 2019

Article The Key to a Strong Workforce

How to help students learn skills essential to the 21st century workforce in and through arts learning.

- Life Skills

Article Get Wired for Learning

Are you stumped about how to integrate technology into your arts teaching? Check out these 8 tips to put you on the road to tech-savvy arts learning.

Article Growing from STEM to STEAM

Find tips to blend arts, sciences, math and technology by learning how one school district experimented with adding STEAM to their classrooms.

Article Inspired Classrooms

Need to battle off those creativity killers? Here are 7 simple steps for educators to create a classroom environment that is friendly to creativity.

Lesson Creating Comic Strips

In this 3-5 lesson, students will examine comic strips as a form of fiction and nonfiction communication. Students will create original comic strips to convey mathematical concepts.

- Visual Arts

- Drawing & Painting

Lesson Multimedia Hero Analysis

In this 9-12 lesson, students will analyze the positive character traits of heroes as depicted in music, art, and literature. They will gain an understanding of how cultures and societies have produced folk, military, religious, political, and artistic heroes. Students will create original multimedia representations of heroes.

- Literary Arts

- Grades 9-12

- Myths, Legends, & Folktales

Kennedy Center Education Digital Learning

Eric Friedman Director, Digital Learning

Kenny Neal Manager, Digital Education Resources

Tiffany A. Bryant Manager, Operations and Audience Engagement

Joanna McKee Program Coordinator, Digital Learning

JoDee Scissors Content Specialist, Digital Learning

Connect with us!

Generous support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. The content of these programs may have been developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education but does not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. You should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Gifts and grants to educational programs at the Kennedy Center are provided by A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; Annenberg Foundation; the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Bank of America; Bender Foundation, Inc.; Carter and Melissa Cafritz Trust; Carnegie Corporation of New York; DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities; Estée Lauder; Exelon; Flocabulary; Harman Family Foundation; The Hearst Foundations; the Herb Alpert Foundation; the Howard and Geraldine Polinger Family Foundation; William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; the Kimsey Endowment; The King-White Family Foundation and Dr. J. Douglas White; Laird Norton Family Foundation; Little Kids Rock; Lois and Richard England Family Foundation; Dr. Gary Mather and Ms. Christina Co Mather; Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation; The Morningstar Foundation;

The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Music Theatre International; Myra and Leura Younker Endowment Fund; the National Endowment for the Arts; Newman’s Own Foundation; Nordstrom; Park Foundation, Inc.; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; The Irene Pollin Audience Development and Community Engagement Initiatives; Prince Charitable Trusts; Soundtrap; The Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust; Rosemary Kennedy Education Fund; The Embassy of the United Arab Emirates; UnitedHealth Group; The Victory Foundation; The Volgenau Foundation; Volkswagen Group of America; Dennis & Phyllis Washington; and Wells Fargo. Additional support is provided by the National Committee for the Performing Arts.

Social perspectives and language used to describe diverse cultures, identities, experiences, and historical context or significance may have changed since this resource was produced. Kennedy Center Education is committed to reviewing and updating our content to address these changes. If you have specific feedback, recommendations, or concerns, please contact us at [email protected] .

By using this site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions which describe our use of cookies.

Reserve Tickets

Review cart.

You have 0 items in your cart.

Your cart is empty.

Keep Exploring Proceed to Cart & Checkout

Donate Today

Support the performing arts with your donation.

To join or renew as a Member, please visit our Membership page .

To make a donation in memory of someone, please visit our Memorial Donation page .

- Custom Other

5 Skills That Students Gain Through Arts Education

Learn more about the five skills arts education can bring students!

Engaging in art is essential to students and humans alike. As soon as children develop motor skills, they communicate through artistic expression. Today, most schools put the majority of their focus on standardized testing and some negate the arts altogether. Arts education and arts integration has been shown to make school work more enjoyable and makes students think about things in a new way. Giving students the materials for artistic expression can lower stress, improve their memory, and make students feel more socially connected.

Here are five skills students can gain through arts education:

1. Self-Confidence

For many people, stage fright and public speaking are a big fear. Just the thought of standing in front of a group of people can be overwhelming. The skills developed in a theatre class will help many students conquer their fear of public speaking. Arts education will give them the tools and confidence they need to feel prepared to walk on stage.

2. Growth Mindset

Through the arts, students develop a growth mindset to help them master their craft. Students develop the need to continuously grow and do well academically to be able to participate in the arts. Students will study or practice not only for the ability to participate in the arts but also because of the self-enjoyment or satisfaction it gives them.

3. Problem Solving

Artistic projects are created by problem-solving. Students and performers are faced with many questions. How do I portray this character's emotion to the audience? How do I sing this note? What kind of sculpture can I make with this clay? The arts teach students to approach these questions/problems head-on and find a solution and ultimately, in the end, create something beautiful.

4. Risk-Taking

Participation in any art form requires risk. It requires students to step outside of their comfort zone at times. The ability to put yourself out there and perform or be part of something different is a skill that students will need well into adulthood.

5. Communication

Our world is built on communication. Great communication is required in any relationship, personal or business. Students learn a multitude of communication skills by studying the arts. Arts participation requires students to verbally, physically, and emotionally communicate. Not just with each other, but with an audience.

An education that includes the arts is essential to a student's success in developing a fulfilling life. Skills developed through participation in the arts are increasingly important in the workplace and therefore, key to a successful career.

Recommended For You

Creativity, the Arts, and the Future of Work

- Open Access

- First Online: 18 September 2018

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Linda F. Nathan 2 , 3

46k Accesses

8 Citations

Those who study the future tend to imagine worlds where burdens are eased and pleasure and personal freedom are elevated. While the concept of work has not disappeared from their predictions, changing technological and global realities have caused a re-imagining of that world. This chapter explores how to educate young students for work environments in a very different future. Specifically, I demonstrate how creativity and arts learning strengthen students’ ability to manage and navigate that new world and contribute to a sustainable society. I offer an educational case study of a highly successful urban public high school for the arts and argue that its intensive arts education model prepares passionate students who can engage with an uncertain future, even if they are less advantaged.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Creativity, Education and the Future

Creativity, the Arts, and Transformative Learning

Speaking of Creativity: Frameworks, Models, and Meanings

- creativityCreativity

- Design thinkingDesign Thinking

- Boston Police Department

- Twenty-first Century Workforce

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

As long as there have been futurists and science fiction writers, there have been predictions that the future would deliver a world without the drudgery of work and with more leisure time and personal freedom for all. Whether the “age of technology and the machine” (Burton 2015 ) will ever be realized is unclear. Nevertheless, society faces a central challenge of how to better prepare young people for an uncertain future where progress and opportunity—social, economic, and environmental—cannot be assumed.

Education, on some level, contributes to “the common good, enhances national prosperity and supports stable families, neighborhoods and communities” (Pellegrino and Hilton 2012 ). However, this statement assumes there to be a linearity between the present and the future. I believe that in order to prepare students for the future that is unfolding now, an educational approach that incorporates creativity and arts-based learning is critical to developing resilient, adaptive citizens that can build the stable families and communities of the future.

This chapter asks a central question about the role of creativity and arts education: how can this emphasis contribute to a more sustainable society and even the future of work (Hellstrom et al. 2015 )? How do artists think about creativity and how might schools do the same? I consider an educational case study of the Boston Arts Academy and describe teaching and learning at this one institution. I explain how an intensive education in the arts prepares students with passion to engage an uncertain future, even if they have fewer advantages than most American students. My concluding remarks emphasize the essential qualities of persistence, passion, and practice for success in life and work.

The Future of Work

A growing body of literature by philosophers, economists, social scientists, and technologists foretell futures of work that crowd around two distinct outcomes: a dystopia of extreme polarization or an Eden of creativity and cultural production (Brynjolfssonand McAfee 2016 ; Thompson 2015 ; Sundararajan 2015 ).

The practice of work happening in a single place for a fixed period of time has entirely eroded for many professionals today. The workplace can span states, continents, and time zones. With new technologies and digital collaboration tools, co-workers can meet both synchronously or asynchronously no matter where they are located or there preferred working hours. These realities reflect both a demand for more work flexibility and a broader transformation of how we work. Today’s entrepreneurs want to decide how “they should define and tackle specific problems and tasks, and when and where work should be done” (Ake Ouye 2011 ). Couple this with the pressure for greater sustainability, companies now manage workplace design, commuting patterns, air travel practices, greenhouse gas emissions, and food service as part of their operations portfolio. And this trend seems to be increasing as younger workers demand more flexibility in work schedules and alternative workplaces (Hellstrom et al. 2015 ).

With these trends in the workplace, what are the implications for the future of work and the skills needed for future workers? Clearly, workplaces need to distribute the settings where work is conducted. The notion of a Central Office must evolve and respond to the diversity of needs and include ways to support collaboration. As the workplace has become more diffuse, the challenge of keeping workers engaged, focused, and connected to mission and vision becomes more problematic. With less daily face time, how do people stay connected? If workers are spread out geographically, work practices need to adapt. Even though workplaces and work itself may be changing, social skills such as empathy, cooperation, communication, and flexibility remain in high demand. Employers want a workforce that understands how to persist with tasks and learns to communicate both up and down hierarchies, as well as laterally with colleagues. Finally, every employer wants workers who understand how to problem-solve.

As these developments disrupt the workplace, public education systems have largely not kept pace, or have even been included as part of the conversation. Post-secondary education is nearly unaffordable for large segments of the population in the United States. Yet the mantra “College and Career Readiness” was a rallying cry and effectively federal policy during the Obama Administration. Nevertheless, career readiness was a muted tagline as doubts increase that a college degree will prepare graduates for their future careers, or more fundamentally, that they will be as prosperous as their parents. With respect to the uncertain and ambiguous future of work, coherence and direction is lacking in educational policy.

Looking to the Future Through Creativity

The Partnership for 21st Century Skills posits that The 4Cs : Communication, Collaboration, Critical Thinking, and Creativity are the central skills and dispositions that all students must master to be successful in our increasingly complex world (Partnership 2010 ). An education centered in creativity and the arts may hold promise for such a twenty-first Century approach to teaching and learning.

In their seminal book, Hetland et al. ( 2013 ) describe a series of eight studio habits of mind that they observed in various schools and programs with strong visual arts curricula. They identify the habits that artists—and arts teachers—tend to employ as:

Develop Craft : Learning tools, materials, and artist’s practices.

Engage and Persist : Learning to pursue topics of personal interest; develop focus, ways of thinking to persevere.

Envision : Picturing, imagining what cannot be observed.

Express : Creating works that convey ideas, meaning, or emotions.

Observe : Learning to view visual, audio, and written resources more critically.

Reflect : Learning to think and converse about one’s work and processes of making.

Stretch and Explore : Learning to stretch beyond perceived limitations, explore, and learning from errors or accidents.

Understand Art World : Learning about art history and artistic practices and engaging the arts community.

The habits provide insight into the ways arts teachers teach and art students learn, and are not necessarily linear or hierarchical. The first habit, development of craft, involves learning about technique, understanding artistic conventions and the use, practice, and care of materials as well as the organization of studio space. Another habit refers to learning about art worlds beyond the classroom such as art history and artistic communities of practice such as galleries, curators, and critics. The six remaining habits, which are seen in serious and high quality visual arts classes, involve general cognitive and attitudinal dispositions towards learning. These six habits are also used in many daily activities as well as various academic pursuits. Causal research about success in the arts and the relationship to success in academic endeavors is still needed, yet current research suggests that the development of artistic habits of mind supports students’ interests in innovation (Winner et al. 2013 ).

The Hetland et al. research is further supported with studies by Eliot Eisner ( 2002 ). These scholars demonstrate how the arts help students develop flexibility, expression, and the ability to shift direction (Hetland et al. 2013 , p. 7). There is clear evidence that arts learning is not just an “emotive” discipline but one that requires deep reflection and intellectual rigor. In my own work (Nathan 2009 ), I describe how we teach the arts not so that students will get better at other subjects such as math (the now debunked “Mozart effect”), rather we teach the arts because they are necessary for enabling their maximum personal development. The arts are a critical part of a young person’s education because they are vehicles for instruction about tolerance, diversity, and the importance of human understanding. In my experience, as our students develop these studio habits of mind, they tend to achieve more success in school and in life outside of school—a finding which will be demonstrated with a case study later in this chapter.

The literature on imagination also supports the importance of creativity and the arts in education. In socio-emotional studies, imagination involves the ability to envision a productive future, and take steps to become the person you want to be in that future (Killingsworth and Gilbert 2010 ). Young people who are immersed in an education system that values and promotes creative and critical thinking will rise to demand what even they did not think possible. Over my many years, as a faculty, school leader, and teacher, my colleagues and I debated how to define creativity and imagination. In the end, we knew both mattered and we experimented with many different curricular innovations with our students to expand the opportunities for creative and critical thinking through the arts. Yet the question persists: what is creativity and how do artists and designers understand its significance to their work?