- Help & FAQ

Bringing a ‘Whole Adolescent‘ perspective to secondary teacher education: A case study of the use of an adolescent case study

- Human Development and Family Studies

- Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center (PRC)

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

An on-going challenge in teacher education programs is how best to support new teachers in connecting their university coursework with their professional identity development and pedagogical practice in the schools. The reading and writing of case studies is one promising strategy teacher educators have explored as a means of assisting teachers in developing and cultivating a self-reflective, theory and practice reflexive, style of learning in the teacher education classroom and beyond. In the present paper, I present a case study of my own journey as a developmental and educational psychologist responsible for co-teaching a secondary teacher education course called "Adolescent Development for Teachers", in which having student-teachers research and write-up a case study of a single adolescent became the focus of the course and our pedagogy. I describe events that brought about the use of the case study in the course, the influence the use of the case study had on myself as an instructor as well as the students, and what students say are the educational benefits and difficulties of completing the adolescent case study. Implications for infusing a developmental focus into teacher education programs are discussed.

All Science Journal Classification (ASJC) codes

- Environmental Chemistry

- Plant Science

Access to Document

- 10.1080/1047621022000007567

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to citation list in Scopus

Fingerprint

- teacher education Agriculture & Biology 100%

- secondary education Agriculture & Biology 87%

- Teacher Training Medicine & Life Sciences 79%

- teachers Agriculture & Biology 66%

- Developmental Chemical Compounds 63%

- case studies Agriculture & Biology 44%

- education Earth & Environmental Sciences 44%

- Education Engineering & Materials Science 44%

T1 - Bringing a ‘Whole Adolescent‘ perspective to secondary teacher education

T2 - A case study of the use of an adolescent case study

AU - Roeser, Robert W.

PY - 2002/1/1

Y1 - 2002/1/1

N2 - An on-going challenge in teacher education programs is how best to support new teachers in connecting their university coursework with their professional identity development and pedagogical practice in the schools. The reading and writing of case studies is one promising strategy teacher educators have explored as a means of assisting teachers in developing and cultivating a self-reflective, theory and practice reflexive, style of learning in the teacher education classroom and beyond. In the present paper, I present a case study of my own journey as a developmental and educational psychologist responsible for co-teaching a secondary teacher education course called "Adolescent Development for Teachers", in which having student-teachers research and write-up a case study of a single adolescent became the focus of the course and our pedagogy. I describe events that brought about the use of the case study in the course, the influence the use of the case study had on myself as an instructor as well as the students, and what students say are the educational benefits and difficulties of completing the adolescent case study. Implications for infusing a developmental focus into teacher education programs are discussed.

AB - An on-going challenge in teacher education programs is how best to support new teachers in connecting their university coursework with their professional identity development and pedagogical practice in the schools. The reading and writing of case studies is one promising strategy teacher educators have explored as a means of assisting teachers in developing and cultivating a self-reflective, theory and practice reflexive, style of learning in the teacher education classroom and beyond. In the present paper, I present a case study of my own journey as a developmental and educational psychologist responsible for co-teaching a secondary teacher education course called "Adolescent Development for Teachers", in which having student-teachers research and write-up a case study of a single adolescent became the focus of the course and our pedagogy. I describe events that brought about the use of the case study in the course, the influence the use of the case study had on myself as an instructor as well as the students, and what students say are the educational benefits and difficulties of completing the adolescent case study. Implications for infusing a developmental focus into teacher education programs are discussed.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85066225032&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=85066225032&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1080/1047621022000007567

DO - 10.1080/1047621022000007567

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:85066225032

SN - 1522-6514

JO - International Journal of Phytoremediation

JF - International Journal of Phytoremediation

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- About Children & Schools

- About the National Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Literature review, alive program, implications for school social work practice.

- < Previous

Trauma and Early Adolescent Development: Case Examples from a Trauma-Informed Public Health Middle School Program

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jason Scott Frydman, Christine Mayor, Trauma and Early Adolescent Development: Case Examples from a Trauma-Informed Public Health Middle School Program, Children & Schools , Volume 39, Issue 4, October 2017, Pages 238–247, https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdx017

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Middle-school-age children are faced with a variety of developmental tasks, including the beginning phases of individuation from the family, building peer groups, social and emotional transitions, and cognitive shifts associated with the maturation process. This article summarizes how traumatic events impair and complicate these developmental tasks, which can lead to disruptive behaviors in the school setting. Following the call by Walkley and Cox for more attention to be given to trauma-informed schools, this article provides detailed information about the Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience program: a school-based, trauma-informed intervention for middle school students. This public health model uses psychoeducation, cognitive differentiation, and brief stress reduction counseling sessions to facilitate socioemotional development and academic progress. Case examples from the authors’ clinical work in the New Haven, Connecticut, urban public school system are provided.

Within the U.S. school system there is growing awareness of how traumatic experience negatively affects early adolescent development and functioning ( Chanmugam & Teasley, 2014 ; Perfect, Turley, Carlson, Yohannan, & Gilles, 2016 ; Porche, Costello, & Rosen-Reynoso, 2016 ; Sibinga, Webb, Ghazarian, & Ellen, 2016 ; Turner, Shattuck, Finkelhor, & Hamby, 2017 ; Woodbridge et al., 2016 ). The manifested trauma symptoms of these students have been widely documented and include self-isolation, aggression, and attentional deficit and hyperactivity, producing individual and schoolwide difficulties ( Cook et al., 2005 ; Iachini, Petiwala, & DeHart, 2016 ; Oehlberg, 2008 ; Sajnani, Jewers-Dailley, Brillante, Puglisi, & Johnson, 2014 ). To address this vulnerability, school social workers should be aware of public health models promoting prevention, data-driven investigation, and broad-based trauma interventions ( Chafouleas, Johnson, Overstreet, & Santos, 2016 ; Johnson, 2012 ; Moon, Williford, & Mendenhall, 2017 ; Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016 ; Overstreet & Matthews, 2011 ). Without comprehensive and effective interventions in the school setting, seminal adolescent developmental tasks are at risk.

This article follows the twofold call by Walkley and Cox (2013) for school social workers to develop a heightened awareness of trauma exposure's impact on childhood development and to highlight trauma-informed practices in the school setting. In reference to the former, this article will not focus on the general impact of toxic stress, or chronic trauma, on early adolescents in the school setting, as this work has been widely documented. Rather, it begins with a synthesis of how exposure to trauma impairs early adolescent developmental tasks. As to the latter, we will outline and discuss the Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience (ALIVE) program, a school-based, trauma-informed intervention that is grounded in a public health framework. The model uses psychoeducation, cognitive differentiation, and brief stress reduction sessions to promote socioemotional development and academic progress. We present two clinical cases as examples of trauma-informed, school-based practice, and then apply their experience working in an urban, public middle school to explicate intervention theory and practice for school social workers.

Impact of Trauma Exposure on Early Adolescent Developmental Tasks

Social development.

Impact of Trauma on Early Adolescent Development

Traumatic experiences may create difficulty with developing and differentiating another person's point of view (that is, mentalization) due to the formation of rigid cognitive schemas that dictate notions of self, others, and the external world ( Frydman & McLellan, 2014 ). For early adolescents, the ability to diversify a single perspective with complexity is central to modulating affective experience. Without the capacity to diversify one's perspective, there is often difficulty differentiating between a nonthreatening current situation that may harbor reminders of the traumatic experience and actual traumatic events. Incumbent on the school social worker is the need to help students understand how these conflicts may trigger a memory of harm, abandonment, or loss and how to differentiate these past memories from the present conflict. This is of particular concern when these reactions are conflated with more common middle school behaviors such as withdrawing, blaming, criticizing, and gossiping ( Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008 ).

Encouraging cognitive discrimination is particularly meaningful given that the second social developmental task for early adolescents is the re-orientation of their primary relationships with family toward peers ( Henderson & Thompson, 2010 ). This shift may become complicated for students facing traumatic stress, resulting in a stunted movement away from familiar connections or a displacement of dysfunctional family relationships onto peers. For example, in the former, a student who has witnessed and intervened to protect his mother from severe domestic violence might believe he needs to sacrifice himself and be available to his mother, forgoing typical peer interactions. In the latter, a student who was beaten when a loud, intoxicated family member came home might become enraged, anxious, or anticipate violence when other students raise their voices.

Cognitive Development and Emotional Regulation

During normative early adolescent development, the prefrontal cortex undergoes maturational shifts in cognitive and emotional functioning, including increased impulse control and affect regulation ( Wigfield, Lutz, & Wagner, 2005 ). However, these developmental tasks can be negatively affected by chronic exposure to traumatic events. Stressful situations often evoke a fear response, which inhibits executive functioning and commonly results in a fight-flight-freeze reaction. If a student does not possess strong anxiety management skills to cope with reminders of the trauma, the student is prone to further emotional dysregulation, lowered frustration tolerance, and increased behavioral problems and depressive symptoms ( Iachini et al., 2016 ; Saltzman, Steinberg, Layne, Aisenberg, & Pynoos, 2001 ).

Typical cognitive development in early adolescence is defined by the ambiguity of a transitional stage between childhood remedial capacity and adult refinement ( Casey & Caudle, 2013 ; Van Duijvenvoorde & Crone, 2013 ). Casey and Caudle (2013) found that although adolescents performed equally as well as, if not better than, adults on a self-control task when no emotional information was present, the introduction of affectively laden social cues resulted in diminished performance. The developmental challenge for the early adolescent then is to facilitate the coordination of this ever-shifting dynamic between cognition and affect. Although early adolescents may display efficient and logically informed behaviors, they may struggle to sustain these behaviors, especially in the presence of emotional stimuli ( Casey & Caudle, 2013 ; Van Duijvenvoorde & Crone, 2013 ). Because trauma often evokes an emotional response ( Johnson & Lubin, 2015 ), these findings insinuate that those early adolescents who are chronically exposed will have ongoing regulation difficulties. Further empirical findings considering the cognitive effects of trauma exposure on the adolescent brain have highlighted detriments in working memory, inhibition, memory, and planning ability ( Moradi, Neshat Doost, Taghavi, Yule, & Dalgleish, 1999 ).

Using a Public Health Framework for School-Based, Trauma-Informed Services

The need for a more informed and comprehensive approach to addressing trauma within the schools has been widely articulated ( Chafouleas et al., 2016 ; Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011 ; Jaycox, Kataoka, Stein, Langley, & Wong, 2012 ; Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016 ; Perry & Daniels, 2016 ). Overstreet and Matthews (2011) suggested that using a public health model to address trauma in schools will promote prevention, early identification, and data-driven investigation and yield broad-based intervention on a policy and communitywide level. A public health approach focuses on developing interventions that address the underlying causal processes that lead to social, emotional, and cognitive maladjustment. Opening the dialogue to the entire student body, as well as teachers and administrators, promotes inclusion and provides a comprehensive foundation for psychoeducation, assessment, and prevention.

ALIVE: A Comprehensive Public Health Intervention for Middle School Students

Note: ALIVE = Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience.

Psychoeducation

The classroom is a place traditionally dedicated to academic pursuits; however, it also serves as an indicator of trauma's impact on cognitive functioning evidenced by poor grades, behavioral dysregulation, and social turbulence. ALIVE practitioners conduct weekly trauma-focused dialogues in the classroom to normalize conversations addressing trauma, to recruit and rehearse more adaptive cognitive skills, and to engage in an insight-oriented process ( Sajnani et al., 2014 ).

Using a parable as a projective tool for identification and connection, the model helps students tolerate direct discussions about adverse experiences. The ALIVE practitioner begins each academic year by telling the parable of a woman named Miss Kendra, who struggled to cope with the loss of her 10-year-old child. Miss Kendra is able to make meaning out of her loss by providing support for schoolchildren who have encountered adverse experiences, serving as a reminder of the strength it takes to press forward after a traumatic event. The intention of this parable is to establish a metaphor for survival and strength to fortify the coping skills already held by trauma-exposed middle school students. Furthermore, Miss Kendra offers early adolescents an opportunity to project their own needs onto the story, creating a personalized figure who embodies support for socioemotional growth.

Following this parable, the students’ attention is directed toward Miss Kendra's List, a poster that is permanently displayed in the classroom. The list includes a series of statements against adolescent maltreatment, comprehensively identifying various traumatic stressors such as witnessing domestic violence; being physically, verbally, or sexually abused; and losing a loved one to neighborhood violence. The second section of the list identifies what may happen to early adolescents when they experience trauma from emotional, social, and academic perspectives. The practitioner uses this list to provide information about the nature and impact of trauma, while modeling for students and staff the ability to discuss difficult experiences as a way of connecting with one another with a sense of hope and strength.

Furthermore, creating a dialogue about these issues with early adolescents facilitates a culture of acceptance, tolerance, and understanding, engendering empathy and identification among students. This fostering of interpersonal connection provides a reparative and differentiated experience to trauma ( Hartling & Sparks, 2008 ; Henderson & Thompson, 2010 ; Johnson & Lubin, 2015 ) and is particularly important given the peer-focused developmental tasks of early adolescence. The positive feelings evoked through classroom-based conversation are predicated on empathic identification among the students and an accompanying sense of relief in understanding the scope of trauma's impact. Furthermore, the consistent appearance of and engagement by the ALIVE practitioner, and the continual presence of Miss Kendra's list, effectively counters traumatically informed expectations of abandonment and loss while aligning with a public health model that attends to the impact of trauma on a regular, systemwide basis.

Participatory and Somatic Indicators for Informal Assessment during the Psychoeducation Component of the ALIVE Intervention

Notes: ALIVE = Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience. Examples are derived from authors’ clinical experiences.

In addition to behavioral symptoms, the content of conversation is considered. All practitioners in the ALIVE program are mandated reporters, and any content presented that meets criteria for suspicion of child maltreatment is brought to the attention of the school leadership and ALIVE director. According to Johnson (2012) , reports of child maltreatment to the Connecticut Department of Child and Family Services have actually decreased in the schools where the program has been implemented “because [the ALIVE program is] catching problems well before they have risen to the severity that would require reporting” (p. 17).

Case Example 1

The following demonstrates a middle school classroom psychoeducation session and assessment facilitated by an ALIVE practitioner (the first author). All names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Ms. Skylar's seventh grade class comprised many students living in low-income housing or in a neighborhood characterized by high poverty and frequent criminal activity. During the second week of school, I introduced myself as a practitioner who was here to speak directly about difficult experiences and how these instances might affect academic functioning and students’ thoughts about themselves, others, and their environment.

After sharing the Miss Kendra parable and list, I invited the students to share their thoughts about Miss Kendra and her journey. Tyreke began the conversation by wondering whether Miss Kendra lost her child to gun violence, exploring the connection between the list and the story and his own frequent exposure to neighborhood shootings. To transition a singular connection to a communal one, I asked the students if this was a shared experience. The majority of students nodded in agreement. I referred the students back to the list and asked them to identify how someone's school functioning or mood may be affected by ongoing neighborhood gun violence. While the students read the list, I actively monitored reactions and scanned for inattention and active avoidance. Performing both active facilitation of discussion and monitoring students’ reactions is critical in accomplishing the goals of providing quality psychoeducation and identifying at-risk students for intervention.

After inspection, Cleo remarked that, contrary to a listed outcome on Miss Kendra's list, neighborhood gun violence does not make him feel lonely; rather, he “doesn't care about it.” Slumped down in his chair, head resting on his crossed arms on the desk in front of him, Cleo's body language suggested a somatized disengagement. I invited other students to share their individual reactions. Tyreke agreed that loneliness is not the identified affective experience; rather, for him, it's feeling “mad or scared.” Immediately, Greg concurred, expressing that “it makes me more mad, and I think about my family.”

Encouraging a variety of viewpoints, I stated, “It sounds like it might make you mad, scared, and may even bring up thoughts about your family. I wonder why people have different reactions?” Doing so moved the conversation into a phase of deeper reflection, simultaneously honoring the students’ voiced experience while encouraging critical thinking. A number of students responded by offering connections to their lives, some indicating they had difficulty identifying feelings. I reflected back, “Sometimes people feel something, but can't really put their finger on it, and sometimes they know exactly how they feel or who it makes them think about.”

I followed with a question: “How do you think it affects your schoolwork or feelings when you're in school?” Greg and Natalia both offered that sometimes difficult or confusing thoughts can consume their whole day, even while in class. Sharon began to offer a related comment when Cleo interrupted by speaking at an elevated volume to his desk partner, Tyreke. The two began to snicker and pull focus. By the time they gained the class's full attention, Cleo was openly laughing and pushing his chair back, stating, “No way! She DID!? That's crazy”; he began to stand up, enlisting Tyreke in the process. While this disruption may be viewed as a challenge to the discussion, it is essential to understand all behavior in context of the session's trauma content. Therefore, Cleo's outburst was interpreted as a potential avenue for further exploration of the topic regarding gun violence and difficulties concentrating. In turn, I posed this question to the class: “Should we talk about this stuff? I wonder if sometimes people have a hard time tolerating it. Can anybody think of why it might be important? Sharon, I think you were saying something about this.” While Sharon continued to share, Cleo and Tyreke gradually shifted their attention back to the conversation. I noted the importance of an individual follow-up with Cleo.

Natalia jumped back in the conversation, stating, “I think we talk about stuff like this so we know about it and can help people with it.” I checked in with the rest of the class about this strategy for coping with the impact of trauma exposure on school functioning: “So it sounds like these thoughts have a pretty big impact on your day. If that's the case, how do you feel less worried or mad or scared?” Marta quickly responded, “You could talk to someone.” I responded, “Part of my job here is to be a person to talk to one-on-one about these things. Hopefully, it will help you feel better to get some of that stuff off your chest.” The students nodded, acknowledging that I would return to discuss other items on the list and that there would be opportunities to check in with me individually if needed.

On reflection, Cleo's disruption in the discussion may be attributed to his personal difficulty emotionally managing intrusive thoughts while in school. This clinical assumption was not explicitly named in the moment, but was noted as information for further individual follow-up. When I met individually with Cleo, Cleo reported that his cousin had been shot a month ago, causing him to feel confused and angry. I continued to work with him individually, which resulted in a reduction of behavioral disruptions in the classroom.

In the preceding case example, the practitioner performed a variety of public health tasks. Foremost was the introduction of how traumatic experience may affect individuals and their relationships with others and their role as a student. Second, the practitioner used Miss Kendra and her list as a foundational mechanism to ground the conversation and serve as a reference point for the students’ experience. Finally, the practitioner actively monitored individual responses to the material as a means of identifying students who may require more support. All three of these processes are supported within the public health framework as a means toward assessment and early intervention for early adolescents who may be exposed to trauma.

Individualized Stress Reduction Intervention

Students are seen for individualized support if they display significant externalizing or internalizing trauma-related behavior. Students are either self-referred; referred by a teacher, administrator, or staff member; or identified by an ALIVE practitioner. Following the principle of immediate engagement based on emergent traumatic material, individual sessions are brief, lasting only 15 to 20 minutes. Using trauma-centered psychotherapy ( Johnson & Lubin, 2015 ), a brief inquiry addressing the current problem is conducted to identify the trauma trigger connected to the original harm, fostering cognitive discrimination. Conversation about the adverse experience proceeds in a calm, direct way focusing on differentiating between intrusive memories and the current situation at school ( Sajnani et al., 2014 ). Once the student exhibits greater emotional regulation, the ALIVE practitioner returns the student to the classroom in a timely manner and may provide either brief follow-up sessions for preventive purposes or, when appropriate, refer the student to more regular, clinical support in or out of the school.

Case Example 2

The following case example is representative of the brief, immediate, and open engagement with traumatic material and encouragement of cognitive discrimination. This intervention was conducted with a sixth grade student, Jacob (name and identifying information changed to ensure confidentiality), by an ALIVE practitioner (the second author).

I found Jacob in the hallway violently shaking a trash can, kicking the classroom door, and slamming his hands into the wall and locker. His teacher was standing at the door, distressed, stating, “Jacob, you need to calm down and go to the office, or I'm calling home!” Jacob yelled, “It's not fair, it was him, not me! I'm gonna fight him!” As I approached, I asked what was making him so angry, but he said, “I don't want to talk about it.” Rather than asking him to calm down or stop slamming objects, I instead approached the potential memory agitating him, stating, “My guess is that you are angry for a very good reason.” Upon this simple connection, he sighed and stopped kicking the trash can and slamming the wall. Jacob continued to demonstrate physical and emotional activation, pacing the hallway and making a fist; however, he was able to recount putting trash in the trash can when a peer pushed him from behind, causing him to yell. Jacob explained that his teacher heard him yelling and scolded him, making him more mad. Jacob stated, “She didn't even know what happened and she blamed me. I was trying to help her by taking out all of our breakfast trash. It's not fair.”

The ALIVE practitioner listens to students’ complaints with two ears, one for the current complaint and one for affect-laden details that may be connected to the original trauma to inquire further into the source of the trigger. Affect-laden details in case example 2 include Jacob's anger about being blamed (rather than toward the student who pushed him), his original intention to help, and his repetition of the phrase “it's not fair.” Having met with Jacob previously, I was aware that his mother suffers from physical and mental health difficulties. When his mother is not doing well, he (as the parentified child) typically takes care of the household, performing tasks like cooking, cleaning, and helping with his two younger siblings and older autistic brother. In the past, Jacob has discussed both idealizing his mother and holding internalized anger that he rarely expresses at home because he worries his anger will “make her sick.”

I know sometimes when you are trying to help mom, there are times she gets upset with you for not doing it exactly right, or when your brothers start something, she will blame you. What just happened sounds familiar—you were trying to help your teacher by taking out the garbage when another student pushed you, and then you were the one who got in trouble.

Jacob nodded his head and explained that he was simply trying to help.

I moved into a more detailed inquiry, to see if there was a more recent stressor I was unaware of. When I asked how his mother was doing this week, Jacob revealed that his mother's health had deteriorated and his aunt had temporarily moved in. Jacob told me that he had been yelled at by both his mother and his aunt that morning, when his younger brother was not ready for school. I asked, “I wonder if when the student pushed you it reminded you of getting into trouble because of something your little brother did this morning?” Jacob nodded. The displacement was clear: He had been reminded of this incident at school and was reacting with anger based on his family dynamic, and worries connected to his mother.

My guess is that you were a mix of both worried and angry by the time you got to school, with what's happening at home. You were trying to help with the garbage like you try to help mom when she isn't doing well, so when you got pushed it was like your brother being late, and then when you got blamed by your teacher it was like your mom and aunt yelling, and it all came flooding back in. The problem is, you let out those feelings here. Even though there are some similar things, it's not totally the same, right? Can you tell me what is different?

Jacob nodded and was able to explain that the other student was probably just playing and did not mean to get him into trouble, and that his teacher did not usually yell at him or make him worried. Highlighting this important differentiation, I replied, “Right—and fighting the student or yelling at the teacher isn't going to solve this, but more importantly, it isn't going to make your mom better or have your family go any easier on you either.” Jacob stated that he knew this was true.

I reassured Jacob that I could help him let out those feelings of worry and anger connected to home so they did not explode out at school and planned to meet again. Jacob confirmed that he was willing to do that. He was able to return to the classroom without incident, with the entire intervention lasting less than 15 minutes.

In case example 2, the practitioner was available for an immediate engagement with disturbing behaviors as they were happening by listening for similarities between the current incident and traumatic stressors; asking for specific details to more effectively help Jacob understand how he was being triggered in school; providing psychoeducation about how these two events had become confused and aiding him in cognitively differentiating between the two; and, last, offering to provide further support to reduce future incidents.

Germane to the practice of school social work is the ability to work flexibly within a public health model to attend to trauma within the school setting. First, we suggest that a primary implication for school social workers is not to wait for explicit problems related to known traumatic experiences to emerge before addressing trauma in the school, but, rather, to follow a model of prevention-assessment-intervention. School social workers are in a unique position within the school system to disseminate trauma-informed material to both students and staff in a preventive capacity. Facilitating this implementation will help to establish a tone and sharpened focus within the school community, norming the process of articulating and engaging with traumatic material. In the aforementioned classroom case example, we have provided a sample of how school social workers might work with entire classrooms on a preventive basis regarding trauma, rather than waiting for individual referrals.

Second, in addition to functional behavior assessments and behavior intervention plans, school social workers maintain a keen eye for qualitative behavioral assessment ( National Association of Social Workers, 2012 ). Using this skill set within a trauma-informed model will help to identify those students in need who may be reluctant or resistant to explicitly ask for help. As called for by Walkley and Cox (2013) , we suggest that using the information presented in Table 1 will help school social workers understand, identify, and assess the impact of trauma on early adolescent developmental tasks. If school social workers engage on a classroom level in trauma psychoeducation and conversations, the information in Table 3 may assist with assessment of children and provide a basis for checking in individually with students as warranted.

Third, school social workers are well positioned to provide individual targeted, trauma-informed interventions based on previous knowledge of individual trauma and through widespread assessment ( Walkley & Cox, 2013 ). The individual case example provides one way of immediately engaging with students who are demonstrating trauma-based behaviors. In this model, school social workers engage in a brief inquiry addressing the current trauma to identify the trauma trigger, discuss the adverse experience in a calm but direct way, and help to differentiate between intrusive memories and the current situation at school. For this latter component, the focus is on cognitive discrimination and emotional regulation so that students can reengage in the classroom within a short time frame.

Fourth, given social work's roots in collaboration and community work, school social workers are encouraged to use a systems-based approach in partnering with allied practitioners and institutions ( D'Agostino, 2013 ), thus supporting the public health tenet of establishing and maintaining a link to the wider community. This may include referring students to regular clinical support in or out of the school. Although the implementation of a trauma-informed program will vary across schools, we suggest that school social workers have the capacity to use a public health school intervention model to ecologically address the psychosocial and behavioral issues stemming from trauma exposure.

As increasing attention is being given to adverse childhood experiences, a tiered approach that uses a public health framework in the schools is necessitated. Nevertheless, there are some limitations to this approach. First, although the interventions outlined here are rooted in prevention and early intervention, there are times when formal, intensive treatment outside of the school setting is warranted. Second, the ALIVE program has primarily been implemented by ALIVE practitioners; the results from piloting this public health framework in other school settings with existing school personnel, such as school social workers, will be necessary before widespread replication.

The public health framework of prevention-assessment-intervention promotes continual engagement with middle school students’ chronic exposure to traumatic stress. There is a need to provide both broad-based and individualized support that seeks to comprehensively ameliorate the social, emotional, and cognitive consequences on early adolescent developmental milestones associated with traumatic experiences. We contend that school social workers are well positioned to address this critical public health issue through proactive and widespread psychoeducation and assessment in the schools, and we have provided case examples to demonstrate one model of doing this work within the school day. We hope that this article inspires future writing about how school social workers individually and systemically address trauma in the school system. In alignment with Walkley and Cox (2013) , we encourage others to highlight their practice in incorporating trauma-informed, school-based programming in an effort to increase awareness of effective interventions.

Card , N. A. , Stucky , B. D. , Sawalani , G. M. , & Little , T. D. ( 2008 ). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender difference, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment . Child Development, 79 , 1185 – 1229 .

Google Scholar

Casey , B. J. , & Caudle , K. ( 2013 ). The teenage brain: Self control . Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22 ( 2 ), 82 – 87 .

Chafouleas , S. M. , Johnson , A. H. , Overstreet , S. , & Santos , N. M. ( 2016 ). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 144 – 162 .

Chanmugam , A. , & Teasley , M. L. ( 2014 ). What should school social workers know about children exposed to intimate partner violence? [Editorial]. Children & Schools, 36 , 195 – 198 .

Cook , A. , Spinazzola , J. , Ford , J. , Lanktree , C. , Blaustein , M. , Cloitre , M. , et al. . ( 2005 ). Complex trauma in children and adolescents . Psychiatric Annals, 35 , 390 – 398 .

D'Agostino , C. ( 2013 ). Collaboration as an essential social work skill [Resources for Practice] . Children & Schools, 35 , 248 – 251 .

Durlak , J. A. , Weissberg , R. P. , Dymnicki , A. B. , Taylor , R. D. , & Schellinger , K. B. ( 2011 ). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions . Child Development, 82 , 405 – 432 .

Frydman , J. S. , & McLellan , L. ( 2014 ). Complex trauma and executive functioning: Envisioning a cognitive-based, trauma-informed approach to drama therapy. In N. Sajnani & D. R. Johnson (Eds.), Trauma-informed drama therapy: Transforming clinics, classrooms, and communities (pp. 179 – 205 ). Springfield, IL : Charles C Thomas .

Google Preview

Hartling , L. , & Sparks , J. ( 2008 ). Relational-cultural practice: Working in a nonrelational world . Women & Therapy, 31 , 165 – 188 .

Henderson , D. , & Thompson , C. ( 2010 ). Counseling children (8th ed.). Belmont, CA : Brooks-Cole .

Iachini , A. L. , Petiwala , A. F. , & DeHart , D. D. ( 2016 ). Examining adverse childhood experiences among students repeating the ninth grade: Implications for school dropout prevention . Children & Schools, 38 , 218 – 227 .

Jaycox , L. H. , Kataoka , S. H. , Stein , B. D. , Langley , A. K. , & Wong , M. ( 2012 ). Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools . Journal of Applied School Psychology, 28 , 239 – 255 .

Johnson , D. R. ( 2012 ). Ask every child: A public health initiative addressing child maltreatment [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.traumainformedschools.org/publications.html

Johnson , D. R. , & Lubin , H. ( 2015 ). Principles and techniques of trauma-centered psychotherapy . Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Publishing .

Moon , J. , Williford , A. , & Mendenhall , A. ( 2017 ). Educators’ perceptions of youth mental health: Implications for training and the promotion of mental health services in schools . Child and Youth Services Review, 73 , 384 – 391 .

Moradi , A. R. , Neshat Doost , H. T. , Taghavi , M. R. , Yule , W. , & Dalgleish , T. ( 1999 ). Everyday memory deficits in children and adolescents with PTSD: Performance on the Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test . Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40 , 357 – 361 .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 2012 ). NASW standards for school social work services . Retrieved from http://www.naswdc.org/practice/standards/NASWSchoolSocialWorkStandards.pdf

Oehlberg , B. ( 2008 ). Why schools need to be trauma informed . Trauma and Loss: Research and Interventions, 8 ( 2 ), 1 – 4 .

Overstreet , S. , & Chafouleas , S. M. ( 2016 ). Trauma-informed schools: Introduction to the special issue . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 1 – 6 .

Overstreet , S. , & Matthews , T. ( 2011 ). Challenges associated with exposure to chronic trauma: Using a public health framework to foster resilient outcomes among youth . Psychology in the Schools, 48 , 738 – 754 .

Perfect , M. , Turley , M. , Carlson , J. S. , Yohannan , J. , & Gilles , M. S. ( 2016 ). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015 . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 7 – 43 .

Perry , D. L. , & Daniels , M. L. ( 2016 ). Implementing trauma-informed practices in the school setting: A pilot study . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 177 – 188 .

Porche , M. V. , Costello , D. M. , & Rosen-Reynoso , M. ( 2016 ). Adverse family experiences, child mental health, and educational outcomes for a national sample of students . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 44 – 60 .

Sajnani , N. , Jewers-Dailley , K. , Brillante , A. , Puglisi , J. , & Johnson , D. R. ( 2014 ). Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience. In N. Sajnani & D. R. Johnson (Eds.), Trauma-informed drama therapy: Transforming clinics, classrooms, and communities (pp. 206 – 242 ). Springfield, IL : Charles C Thomas .

Saltzman , W. R. , Steinberg , A. M. , Layne , C. M. , Aisenberg , E. , & Pynoos , R. S. ( 2001 ). A developmental approach to school-based treatment of adolescents exposed to trauma and traumatic loss . Journal of Child and Adolescent Group Therapy, 11 ( 2–3 ), 43 – 56 .

Sibinga , E. M. , Webb , L. , Ghazarian , S. R. , & Ellen , J. M. ( 2016 ). School-based mindfulness instruction: An RCT . Pediatrics, 137 ( 1 ), e20152532 .

Tucker , C. , Smith-Adcock , S. , & Trepal , H. C. ( 2011 ). Relational-cultural theory for middle school counselors . Professional School Counseling, 14 , 310 – 316 .

Turner , H. A. , Shattuck , A. , Finkelhor , D. , & Hamby , S. ( 2017 ). Effects of poly-victimization on adolescent social support, self-concept, and psychological distress . Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32 , 755 – 780 .

van der Kolk , B. A. ( 2005 ). Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories . Psychiatric Annals, 35 , 401 – 408 .

Van Duijvenvoorde , A.C.K. , & Crone , E. A. ( 2013 ). The teenage brain: A neuroeconomic approach to adolescent decision making . Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22 ( 2 ), 114 – 120 .

Walkley , M. , & Cox , T. L. ( 2013 ). Building trauma-informed schools and communities [Trends & Resources] . Children & Schools, 35 , 123 – 126 .

Wigfield , A. W. , Lutz , S. L. , & Wagner , L. ( 2005 ). Early adolescents’ development across the middle school years: Implications for school counselors . Professional School Counseling, 9 ( 2 ), 112 – 119 .

Woodbridge , M. W. , Sumi , W. C. , Thornton , S. P. , Fabrikant , N. , Rouspil , K. M. , Langley , A. K. , & Kataoka , S. H. ( 2016 ). Screening for trauma in early adolescence: Findings from a diverse school district . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 89 – 105 .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- About Children & Schools

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1545-682X

- Print ISSN 1532-8759

- Copyright © 2024 National Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE Open Nurs

- v.7; Jan-Dec 2021

Case Study Analysis as an Effective Teaching Strategy: Perceptions of Undergraduate Nursing Students From a Middle Eastern Country

Vidya seshan.

1 Maternal and Child Health Department, College of Nursing, Sultan Qaboos University, P.O. Box 66 Al-Khoudh, Postal Code 123, Muscat, Oman

Gerald Amandu Matua

2 Fundamentals and Administration Department, College of Nursing, Sultan Qaboos University, P.O. Box 66 Al-Khoudh, Postal Code 123, Muscat, Oman

Divya Raghavan

Judie arulappan, iman al hashmi, erna judith roach, sheeba elizebath sunderraj, emi john prince.

3 Griffith University, Nathan Campus, Queensland 4111

Background: Case study analysis is an active, problem-based, student-centered, teacher-facilitated teaching strategy preferred in undergraduate programs as they help the students in developing critical thinking skills. Objective: It determined the effectiveness of case study analysis as an effective teacher-facilitated strategy in an undergraduate nursing program. Methodology: A descriptive qualitative research design using focus group discussion method guided the study. The sample included undergraduate nursing students enrolled in the Maternal Health Nursing Course during the Academic Years 2017 and 2018. The researcher used a purposive sampling technique and a total of 22 students participated in the study, through five (5) focus groups, with each focus group comprising between four to six nursing students. Results: In total, nine subthemes emerged from the three themes. The themes were “Knowledge development”, “Critical thinking and Problem solving”, and “Communication and Collaboration”. Regarding “Knowledge development”, the students perceived case study analysis method as contributing toward deeper understanding of the course content thereby helping to reduce the gap between theory and practice especially during clinical placement. The “Enhanced critical thinking ability” on the other hand implies that case study analysis increased student's ability to think critically and aroused problem-solving interest in the learners. The “Communication and Collaboration” theme implies that case study analysis allowed students to share their views, opinions, and experiences with others and this enabled them to communicate better with others and to respect other's ideas which further enhanced their team building capacities. Conclusion: This method is effective for imparting professional knowledge and skills in undergraduate nursing education and it results in deeper level of learning and helps in the application of theoretical knowledge into clinical practice. It also broadened students’ perspectives, improved their cooperation capacity and their communication with each other. Finally, it enhanced student's judgment and critical thinking skills which is key for their success.

Introduction/Background

Recently, educators started to advocate for teaching modalities that not only transfer knowledge ( Shirani Bidabadi et al., 2016 ), but also foster critical and higher-order thinking and student-centered learning ( Wang & Farmer, 2008 ; Onweh & Akpan, 2014). Therefore, educators need to utilize proven teaching strategies to produce positive outcomes for learners (Onweh & Akpan, 2014). Informed by this view point, a teaching strategy is considered effective if it results in purposeful learning ( Centra, 1993 ; Sajjad, 2010 ) and allows the teacher to create situations that promote appropriate learning (Braskamp & Ory, 1994) to achieve the desired outcome ( Hodges et al., 2020 ). Since teaching methods impact student learning significantly, educators need to continuously test the effectives of their teaching strategies to ensure desired learning outcomes for their students given today's dynamic learning environments ( Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018 ).

In this study, the researchers sought to study the effectiveness of case study analysis as an active, problem-based, student-centered, teacher-facilitated strategy in a baccalaureate-nursing program. This choice of teaching method is supported by the fact that nowadays, active teaching-learning is preferred in undergraduate programs because, they not only make students more powerful actors in professional life ( Bean, 2011 ; Yang et al., 2013 ), but they actually help learners to develop critical thinking skills ( Clarke, 2010 ). In fact, students who undergo such teaching approaches usually become more resourceful in integrating theory with practice, especially as they solve their case scenarios ( Chen et al., 2019 ; Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018 ; Savery, 2019 ).

Review of Literature

As a pedagogical strategy, case studies allow the learner to integrate theory with real-life situations as they devise solutions to the carefully designed scenarios ( Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018 ; Hermens & Clarke, 2009). Another important known observation is that case-study-based teaching exposes students to different cases, decision contexts and the environment to experience teamwork and interpersonal relations as “they learn by doing” thus benefiting from possibilities that traditional lectures hardly create ( Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018 ; Garrison & Kanuka, 2004 ).

Another merit associated with case study method of teaching is the fact that students can apply and test their perspectives and knowledge in line with the tenets of Kolb et al.'s (2014) “experiential learning model”. This model advocates for the use of practical experience as the source of one's learning and development. Proponents of case study-based teaching note that unlike passive lectures where student input is limited, case studies allow them to draw from their own experience leading to the development of higher-order thinking and retention of knowledge.

Case scenario-based teaching also encourages learners to engage in reflective practice as they cooperate with others to solve the cases and share views during case scenario analysis and presentation ( MsDade, 1995 ).

This method results in “idea marriage” as learners articulate their views about the case scenario. This “idea marriage” phenomenon occurs through knowledge transfer from one situation to another as learners analyze scenarios, compare notes with each other, and develop multiple perspectives of the case scenario. In fact, recent evidence shows that authentic case-scenarios help learners to acquire problem solving and collaborative capabilities, including the ability to express their own views firmly and respectfully, which is vital for future success in both professional and personal lives ( Eronen et al., 2019 ; Yajima & Takahashi, 2017 ). In recognition of this higher education trend toward student-focused learning, educators are now increasingly expected to incorporate different strategies in their teaching.

This study demonstrated that when well implemented, educators can use active learning strategies like case study analysis to aid critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaborative capabilities in undergraduate students. This study is significant because the findings will help educators in the country and in the region to incorporate active learning strategies such as case study analysis to aid critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaborative capabilities in undergraduate students. Besides, most studies on the case study method in nursing literature mostly employ quantitative methods. The shortage of published research on the case study method in the Arabian Gulf region and the scanty use of qualitative methods further justify why we adopted the focus group method for inquiry.

A descriptive qualitative research design using focus group discussion method guided the study. The authors chose this method because it is not only inexpensive, flexible, stimulating but it is also known to help with information recall and results in rich data ( Matua et al., 2014 ; Streubert & Carpenter, 2011 ). Furthermore, as evidenced in the literature, the focus group discussion method is often used when there is a need to gain an in-depth understanding of poorly understood phenomena as the case in our study. The choice of this method is further supported by the scarcity of published research related to the use of case study analysis as a teaching strategy in the Middle Eastern region, thereby further justifying the need for an exploratory research approach for our study.

As a recommended strategy, the researchers generated data from information-rich purposively selected group of baccalaureate nursing students who had experienced both traditional lectures and cased-based teaching approaches. The focus group interviews allowed the study participants to express their experiences and perspectives in their own words. In addition, the investigators integrated participants’ self-reported experiences with their own observations and this enhanced the study findings ( Morgan & Bottorff, 2010 ; Nyumba et al., 2018 ; Parker & Tritter, 2006 ).

Eligibility Criteria

In order to be eligible to participate in the study, the participants had to:

- be a baccalaureate nursing student in College of Nursing, Sultan Qaboos University

- register for Maternity Nursing Course in 2017 and 2018.

- attend all the Case Study Analysis sessions in the courses before the study.

- show a willingness to participate in the study voluntarily and share their views freely.

The population included the undergraduate nursing students enrolled in the Maternal Health Nursing Course during the Academic Years 2017 and 2018.

The researcher used a purposive sampling technique to choose participants who were capable of actively participating and discussing their views in the focus group interviews. This technique enabled the researchers to select participants who could provide rich information and insights about case study analysis method as an effective teaching strategy. The final study sample included baccalaureate nursing students who agreed to participate in the study by signing a written informed consent. In total, twenty-two (22) students participated in the study, through five focus groups, with each focus group comprising between four and six students. The number of participants was determined by the stage at which data saturation was reached. The point of data saturation is when no new information emerges from additional participants interviewed ( Saunders et al., 2018 ).Focus group interviews were stopped once data saturation was achieved. Qualitative research design with focus group discussion allowed the researchers to generate data from information-rich purposively selected group of baccalaureate nursing students who had experienced both traditional lectures and case-based teaching approaches. The focus group interviews allowed the study participants to express their perspectives in their own words. In addition, the investigators enhanced the study findings by integrating participants’ self-reported experiences with the researchers’ own observations and notes during the study.

The study took place at College of Nursing; Sultan Qaboos University, Oman's premier public university, in Muscat. This is the only setting chosen for the study. The participants are the students who were enrolled in Maternal Health Nursing course during 2017 and 2018. The interviews occurred in the teaching rooms after official class hours. Students who did not participate in the study learnt the course content using the traditional lecture based method.

Ethical Considerations

Permission to conduct the study was granted by the College Research and Ethics Committee (XXXX). Prior to the interviews, each participant was informed about the purpose, benefits as well as the risks associated with participating in the study and clarifications were made by the principal researcher. After completing this ethical requirement, each student who accepted to participate in the study proceeded to sign an informed consent form signifying that their participation in the focus group interview was entirely voluntary and based on free will.

The anonymity of study participants and confidentiality of their data was upheld throughout the focus group interviews and during data analysis. To enhance confidentiality and anonymity of the data, each participant was assigned a unique code number which was used throughout data analysis and reporting phases. To further assure the confidentiality of the research data and anonymity of the participants, all research-related data were kept safe, under lock and key and through digital password protection, with unhindered access only available to the research team.

Research Intervention

In Fall 2017 and Spring 2018 semesters, as a method of teaching Maternal Health Nursing course, all students participated in two group-based case study analysis exercises which were implemented in the 7 th and 13 th weeks. This was done after the students were introduced to the case study method using a sample case study prior to the study. The instructor explained to the students how to solve the sample problem, including how to accomplish the role-specific competencies in the courses through case study analysis. In both weeks, each group consisting of six to seven students was assigned to different case scenarios to analyze and work on, after which they presented their collective solution to the case scenarios to the larger class of 40 students. The case scenarios used in both weeks were peer-reviewed by the researchers prior to the study.

Pilot Study

A group of three students participated as a pilot group for the study. However, the students who participated in the pilot study were not included in the final study as is general the principle with qualitative inquiry because of possible prior exposure “contamination”. The purpose of piloting was to gather data to provide guidance for a substantive study focusing on testing the data collection procedure, the interview process including the sequence and number of questions and probes and recording equipment efficacy. After the pilot phase, the lessons learned from the pilot were incorporated to ensure smooth operations during the actual focus group interview ( Malmqvist et al., 2019 .

Data Collection

The focus group interviews took place after the target population was exposed to case study analysis method in Maternal Health Nursing course during the Fall 2017 and Spring 2018 semesters. Before data collection began, the research team pilot tested the focus group interview guide to ensure that all the guide questions were clear and well understood by study participants.

In total, five (5) focus groups participated in the study, with each group comprising between four and six students. The focus group interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min. In addition to the interview guide questions, participants’ responses to unanswered questions were elicited using prompts to facilitate information flow whenever required. As a best practice, all the interviews were audio-recorded in addition to extensive field notes taken by one of the researchers. The focus group interviews continued until data saturation occurred in all the five (5) focus groups.

Credibility

In this study, participant's descriptions were digitally audio recorded to ensure that no information was lost. In order to ensure that the results are accurate, verbatim transcriptions of the audio recordings were done supported by interview notes. Furthermore, interpretations of the researcher were verified and supported with existing literature with oversight from the research team.

Transferability

The researcher provided a detailed description about the study settings, participants, sampling technique, and the process of data collection and analyses. The researcher used verbatim quotes from various participants to aid the transferability of the results.

Dependability

The researcher ensured that the research process is clearly documented, traceable, and logical to achieve dependability of the research findings. Furthermore, the researcher transparently described the research steps, procedures and process from the start of the research project to the reporting of the findings.

Confirmability

In this study, confirmability of the study findings was achieved through the researcher's efforts to make the findings credible, dependable, and transferable.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed manually after the lead researcher integrated the verbatim transcriptions with the extensive field notes to form the final data set. Data were analyzed thematically under three thematic areas of a) knowledge development; b) critical thinking and problem solving; and (c) communication and collaboration, which are linked to the study objectives. The researchers used the Six (6) steps approach to conduct a trustworthy thematic analysis: (1) familiarization with the research data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing the themes, (5) defining and naming themes, (6) writing the report ( Nowell et al., 2017 ).

The analysis process started with each team member individually reading and re-reading the transcripts several times and then identifying meaning units linked to the three thematic areas. The co-authors then discussed in-depth the various meaning units linked to the thematic statements until consensus was reached and final themes emerged based on the study objectives.

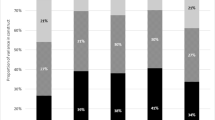

A total of 22 undergraduate third-year baccalaureate nursing students who were enrolled in the Maternal Health Nursing Course during the Academic Years 2017 and 2018 participated in the study, through five focus groups, with each group comprising four to six students. Of these, 59% were females and 41% were males. In total, nine subthemes emerged from the three themes. Under knowledge development, emerged the subthemes, “ deepened understanding of content ; “ reduced gap between theory and practice” and “ improved test-taking ability ”. While under Critical thinking and problem solving, emerged the subthemes, “ enhanced critical thinking ability ” and “ heightened curiosity”. The third thematic area of communication and collaboration yielded, “ improved communication ability ”; “ enhanced team-building capacity ”; “ effective collaboration” and “ improved presentation skills ”, details of which are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Objective Linked Themes and Student Perceptions of Outcome Case Study Analysis.

Theme 1: Knowledge Development

In terms of knowledge development, students expressed delight at the inclusion of case study analysis as a method during their regular theory class. The first subtheme related to knowledge development that supports the adoption of the case study approach is its perceived benefit of ‘ deepened understanding of content ’ by the students as vividly described by this participant:

“ I was able to perform well in the in-course exams as this teaching method enhanced my understanding of the content rather than memorizing ” (FGD#3).

The second subtheme related to knowledge development was informed by participants’ observation that teaching them using case study analysis method ‘ reduced the gap between theory and practice’. This participant's claim stem from the realization that, a case study scenario his group analyzed in the previous week helped him and his colleagues to competently deal with a similar situation during clinical placement the following week, as articulated below:

“ You see when I was caring for mothers in antenatal unit, I could understand the condition better and could plan her care well because me and my group already analyzed a similar situation in class last week which the teacher gave us, this made our work easier in the ward”. (FGD#7).

Another student added that:

“ It was useful as what is taught in the theory class could be applied to the clinical cases.”

This ‘theory-practice’ connection was particularly useful in helping students to better understand how to manage patients with different health conditions. Interestingly, the students reported that they were more likely to link a correct nursing care plan to patients whose conditions were close to the case study scenarios they had already studied in class as herein affirmed:

“ …when in the hospital I felt I could perceive the treatment modality and plan for [a particular] nursing care well when I [had] discussed with my team members and referred the textbook resource while performing case study discussion”. (FGD#17).

In a similar way, another student added:

“…I could relate with the condition I have seen in the clinical area. So this has given me a chance to recall the condition and relate the theory to practice”. (FGD#2) .

The other subtheme closely related to case study scenarios as helping to deepen participant's understanding of the course content, is the notion that this teaching strategy also resulted in ‘ improved test taking-ability’ as this participant's verbatim statement confirms:

“ I could answer the questions related to the cases discussed [much] better during in-course exams. Also [the case scenarios] helped me a great deal to critically think and answer my exam papers” (FGD#11).

Theme 2: Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

In this subtheme, students found the case study analysis as an excellent method to learn disease conditions in the two courses. This perceived success with the case study approach is associated with the method's ability to ‘ enhance students’ critical thinking ability’ as this student declares:

“ This method of teaching increased my ability to think critically as the cases are the situations, where we need to think to solve the situation”. (FGD#5)

This enhanced critical thinking ability attributed to case study scenario analysis was also manifested during patient care where students felt it allowed them to experience a “ flow of patient care” leading to better patient management planning as would typically occur during case scenario analysis. In support of this finding, a participant mentioned that:

“ …I could easily connect the flow of patient care provided and hence was able to plan for [his] management as often required during case study discussion” (FGD#12)

Another subtheme linked with this theme is the “ heightened curiosity” associated with the case scenario discussions. It was clear from the findings that the cases aroused curiosity in the mind of the students. This heightened interest meant that during class discussion, baccalaureate nursing students became active learners, eager to discover the next set of action as herein affirmed:

“… from the beginning of discussion with the group, I was eager to find the answer to questions presented and wanted to learn the best way for patient management” (FGD#14)

Theme 3: Communication and Collaboration

In terms of its impact on student communication, the subtheme revealed that case study analysis resulted in “ improved communication ability” among the nursing students . This enhanced ability of students to exchange ideas with each other may be attributed to the close interaction required to discuss and solve their assigned case scenarios as described by the participant below:

“ as [case study analysis] was done in the way of group discussion, I felt me and my friends communicated more within the group as we discussed our condition. We also learnt from each other, and we became better with time.” (FGD#21).

The next subtheme further augments the notion that case study analysis activities helped to “ enhance team-building capacity” of students as this participant affirmatively narrates:

“ students have the opportunity to meet face to face to share their views, opinion, and their experience, as this build on the way they can communicate with each other and respect each other's opinions and enhance team-building”. (FGD#19).

Another subtheme revealed from the findings show that the small groups in which the case analysis occurs allowed the learners to have deeper and more focused conversations with one another, resulting in “ an effective collaboration between students” as herein declared:

“ We could collaborate effectively as we further went into a deep conversation on the case to solve”. (FGD#16).

Similarly, another student noted that:

“ …discussion of case scenarios helped us to prepare better for clinical postings and simulation lab experience” (FGD#5) .

A fourth subtheme related to communication found that students also identified that case study analysis resulted in “ improved presentation skills”. This is attributed in part to the preparation students have to go through as part of their routine case study discussion activities, which include organizing their presentations and justifying and integrating their ideas. Besides readying themselves for case presentations, the advice, motivation, and encouragement such students receive from their faculty members and colleagues makes them better presenters as confirmed below:

“ …teachers gave us enough time to prepare, hence I was able to present in front of the class regarding the finding from our group.” (FGD#16).

In this study, the researches explored learner's perspectives on how one of the active teaching strategies, case study analysis method impacted their knowledge development, critical thinking, and problem solving as well as communication and collaboration ability.

Knowledge Development

In terms of knowledge development, the nursing students perceived case study analysis as contributing toward: (a) deeper understanding of content, (b) reducing gap between theory and practice, and (c) improving test-taking ability. Deeper learning” implies better grasping and retention of course content. It may also imply a deeper understanding of course content combined with learner's ability to apply that understanding to new problems including grasping core competencies expected in future practice situations (Rickles et al., 2019; Rittle-Johnson et al., 2020 ). Deeper learning therefore occurs due to the disequilibrium created by the case scenario, which is usually different from what the learner already knows ( Hattie, 2017 ). Hence, by “forcing” students to compare and discuss various options in the quest to solve the “imbalance” embedded in case scenarios, students dig deeper in their current understanding of a given content including its application to the broader context ( Manalo, 2019 ). This movement to a deeper level of understanding arises from carefully crafted case scenarios that instructors use to stimulate learning in the desired area (Nottingham, 2017; Rittle-Johnson et al., 2020 ). The present study demonstrated that indeed such carefully crafted case study scenarios did encourage students to engage more deeply with course content. This finding supports the call by educators to adopt case study as an effective strategy.

Another finding that case study analysis method helps in “ reducing the gap between theory and practice ” implies that the method helps students to maintain a proper balance between theory and practice, where they can see how theoretical knowledge has direct practical application in the clinical area. Ajani and Moez (2011) argue that to enable students to link theory and practice effectively, nurse educators should introduce them to different aspects of knowledge and practice as with case study analysis. This dual exposure ensures that students are proficient in theory and clinical skills. This finding further amplifies the call for educators to adequately prepare students to match the demands and realities of modern clinical environments ( Hickey, 2010 ). This expectation can be met by ensuring that student's knowledge and skills that are congruent with hospital requirements ( Factor et al., 2017 ) through adoption of case study analysis method which allows integration of clinical knowledge in classroom discussion on regular basis.

The third finding, related to “improved test taking ability”, implies that case study analysis helped them to perform better in their examination, noting that their experience of going through case scenario analysis helped them to answer similar cases discussed in class much better during examinations. Martinez-Rodrigo et al. (2017) report similar findings in a study conducted among Spanish electrical engineering students who were introduced to problem-based cooperative learning strategies, which is similar to case study analysis method. Analysis of student's results showed that their grades and pass rates increased considerably compared to previous years where traditional lecture-based method was used. Similar results were reported by Bonney (2015) in an even earlier study conducted among biology students in Kings Borough community college students, in New York, United States. When student's performance in examination questions covered by case studies was compared with class-room discussions, and text-book reading, case study analysis approach was significantly more effective compared to traditional methods in aiding students’ performance in their examinations. This finding therefore further demonstrates that case study analysis method indeed improves student's test taking ability.

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

In terms of critical thinking and problem-solving ability, the use of case study analysis resulted in two subthemes: (a) enhanced critical thinking ability and (b) heightened learner curiosity. The “ enhanced critical thinking ability” implies that case analysis increased student's ability to think critically as they navigated through the case scenarios. This observation agrees with the findings of an earlier questionnaire-based study conducted among 145 undergraduate business administration students at Chittagong University, Bangladesh, that showed 81% of respondents agree that case study analysis develops critical thinking ability and enables students to do better problem analysis ( Muhiuddin & Jahan, 2006 ). This observation agrees with the findings of an earlier study conducted among 145 undergraduate business administration students at Chittagong University, Bangladesh. The study showed that 81% of respondents agreed that case study analysis facilitated the development of critical thinking ability in the learners and enabled the students to perform better with problem analysis ( Muhiuddin & Jahan, 2006 ).

More recently, Suwono et al. (2017) found similar results in a quasi-experimental research conducted at a Malaysian university. The research findings showed that there was a significant difference in biological literacy and critical thinking skills between the students taught using socio-biological case-based learning and those taught using traditional lecture-based learning. The researchers concluded that case-based learning enhanced the biological literacy and critical thinking skills of the students. The current study adds to the existing pedagogical knowledge base that case study methodology can indeed help to deepen learner's critical thinking and problem solving ability.

The second subtheme related to “ heightened learner curiosity” seems to suggest that the case studies aroused problem-solving interest in learners. This observation agrees with two earlier studies by Tiwari et al. (2006) and Flanagan and McCausland (2007) who both reported that most students enjoyed case-based teaching. The authors add that the case study method also improved student's clinical reasoning, diagnostic interpretation of patient information as well as their ability to think logically when presented a challenge in the classroom and in the clinical area. Jackson and Ward (2012) similarly reported that first year engineering undergraduates experienced enhanced student motivation. The findings also revealed that the students venturing self-efficacy increased much like their awareness of the importance of key aspects of the course for their future careers. The authors conclude that the case-based method appears to motivate students to autonomously gather, analyze and present data to solve a given case. The researchers observed enhanced personal and collaborative efforts among the learners, including improved communication ability. Further still, learners were more willing to challenge conventional wisdom, and showed higher “softer” skills after exposure to case analysis based teaching method. These findings like that of the current study indicate that teaching using case based analysis approach indeed motivates students to engage more in their learning, there by resulting in deeper learning.

Communication and Collaboration