- Login / Register

‘Nearly a week has passed already since International Nurses Day 2024’

STEVE FORD, EDITOR

- You are here: Assessment skills

Communication skills 2: overcoming the barriers to effective communication

18 December, 2017 By NT Contributor

This article, the second in a six-part series on communication skills, a discusses the barriers to effective communication and how to overcome them

Competing demands, lack of privacy, and background noise are all potential barriers to effective communication between nurses and patients. Patients’ ability to communicate effectively may also be affected by their condition, medication, pain and/or anxiety. Nurses’ and patients’ cultural values and beliefs can also lead to misinterpretation or reinterpretation of key messages. This article, the second in a six-part series on communication skills , suggests practical ways of overcoming the most common barriers to communication in healthcare.

Citation: Ali M (2017) Communication skills 2: overcoming barriers to effective communication Nursing Times ; 114: 1, 40-42.

Author: Moi Ali is a communications consultant, a board member of the Scottish Ambulance Service and of the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Care, and a former vice-president of the Nursing and Midwifery Council.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here

- Click here to see other articles in this series

- Read Moi Ali’s comment

Introduction

It is natural for patients to feel apprehensive about their health and wellbeing, yet a survey in 2016 found that only 38% of adult inpatients who had worries or fears could ‘definitely’ find someone in hospital to talk to about them (Care Quality Commission, 2017). There are numerous barriers to effective communication including:

- Time constraints;

- Environmental issues such as noise and privacy;

- Pain and fatigue;

- Embarrassment and anxiety;

- Use of jargon;

- Values and beliefs;

- Information overload.

Time constraints

Time – or lack of it – creates a significant barrier to communication for nurses (Norouzinia et al, 2016). Hurried communication is never as effective as a leisurely interaction, yet in pressured workplaces, nurses faced with competing demands may neglect the quality of communication. It is important to remember that communication does not need to be time-consuming – a smile, hello, or some ‘small talk’ about the weather may suffice. Even when there is no pressing news to tell individual patients, taking the time to get to know them can prepare the ground for difficult conversations that may need to take place in the future.

In a pressured ward or clinic, conversations between patients and nurses may be delayed or interrupted because of the needs of other patients – for example, they may need to respond to an emergency or pain relief. This can be frustrating for patients who may feel neglected. If interruptions occur it is important to explain to patients that you have to leave and why. Arranging to return within a specified time frame may be enough to reassure them that you are aware that their concerns are important (Box 1).

Box 1. Making time for communication

Nurse Amy Green was allocated a bay of four patients and two side wards for her shift. Halfway through the morning one of her patients in a side ward became very ill and Amy realised that she needed to spend a lot of time with him. She quickly visited her other patients to explain what was happening, and reassured them that she had not forgotten about them. She checked that they were comfortable and not in pain, asked them to ring the call bell if they needed her, and explained that she would return as soon as she could. The patients understood the situation and were reassured that their immediate needs had been assessed and they were not being neglected.

Environmental factors

You may be so familiar with your surroundings that you no longer notice the environmental factors that can create communication difficulties. Background noise in a busy clinic can affect patients’ ability to hear, and some may try to disguise this by nodding and ‘appearing’ to hear. If you think your patient has hearing problems, reduce background noise, find a quiet corner or step into a quiet side room or office. Check whether your patient uses physical aids, such as hearing aids or spectacles and that these are in working order.

Noise and other distractions can impede communication with patients with dementia and other cognitive impairments, who find concentration challenging. If you have to communicate an important message to a patient with poor concentration, it is useful to plan ahead and identify the best place and time to talk. It can be helpful to choose a time when you are less busy, without competing activities such as medicine rounds or meal times to interrupt your discussion.

Patients may be reticent to provide sensitive personal information if they are asked about their clinical history within earshot of other people, such as at a busy reception desk or in a cubicle with just a curtain for privacy. It is important to avoid asking sensitive questions where others may hear patients’ replies. Consider alternative ways of gathering pertinent information, such as asking the patient to complete a written form – but remember that some patients struggle with reading and writing or may need the form to be provided in a different language or have someone translate for them.

Pain and fatigue

We often need to gain important information from patients when they are acutely ill and distressed, and symptoms such as pain can reduce concentration. If you urgently need to gather information, it is important to acknowledge pain and discomfort: “I know that it is painful, but it’s important that we discuss.”

Patients may also be tired from a sleepless night, drowsy after an anaesthetic or experiencing the side-effects of medicines. Communicating with someone who is not fully alert is difficult, so it is important to prioritise the information you need, assess whether it is necessary to speak to the patient and ask yourself:

- Is this the best time for this conversation?

- Can my message wait?

- Can I give part of the message now and the rest later?

When patients cannot give their full attention, consider whether your message could be broken down into smaller pieces so there is less to digest in one go: “I will explain your medication now. I’ll return after lunch to tell you about how physiotherapy may help.” Ask if they would like any of the information repeated.

If you have to impart an important piece of information, acknowledge how the patient is feeling: “I know that you’re tired, but …”. Showing empathy can build rapport and make patients more receptive. It may also be useful to stress the need to pay attention: “It’s important that you listen because …”. Consider repeating the message: “It can be difficult to take everything in when you’re tired, so I just wanted to check that you’re clear about …”. If the communication is important, ask the patient to repeat it back to you to check it has been understood.

Embarrassment and anxiety

Would you feel comfortable undressing in front of a complete stranger, or talking about sex, difficult family circumstances, addictions or bowel problems? Patients’ and health professionals’ embarrassment can result in awkward encounters that may hamper effective communication. However, anticipating potential embarrassment, minimising it, and using straightforward, open communication can ease difficult conversations. For example, in a clinic, a patient may need to remove some clothes for an examination. It is important to be direct and specific. Do not say: “Please undress”, as patients may not know what to remove; give specific instructions: “Please remove your trousers and pants, but keep your shirt on”. Clear directions can ease stress and embarrassment when delivered with matter-of-fact confidence.

Patients may worry about embarrassing you or themselves by using inappropriate terms for anatomical parts or bodily functions. You can ease this embarrassment by introducing words such as “bowel movements” or “penis” into your questions, if you think they are unsure what terminology to use. Ambiguous terms such as “stool”, which have a variety of everyday meanings, should be avoided as they may cause confusion.

Many patients worry about undergoing intimate procedures such as bowel and bladder investigations. Explain in plain English what an examination involves, so that patients know what to expect. Explaining any side-effects of procedures – such as flatulence or vomiting – not only warns patients what to expect but reassures them that staff will not be offended if these occur.

Box 2 provides some useful tips on dealing with embarrassment.

Box 2. Managing embarrassment

- Look out for signs of embarrassment – not just obvious ones like blushing, but also laughter, joking, fidgeting and other behaviours aimed at masking it

- Think about your facial expressions when communicating with patients, and use positive, open body language such as appropriate eye contact or nodding

- Avoid disapproving or judgmental statements by phrasing questions carefully: “You don’t drink more than 10 glasses of wine a week, do you?” suggests that the ‘right’ or desired answer is ‘no’. A neutral, open question will elicit a more honest response: “How many glasses of wine do you drink in a typical week?”

Some patients are reluctant to ask questions, seek clarification or request that information be repeated for fear of wasting nurses’ time. It is important to let them know that their health or welfare is an integral part of your job. They also need to know that there is no such thing as a silly question. Encourage questions by using prompts and open questions such as: “You’re bound to have questions – are there any that I can answer for you now?”; “What else can I tell you about the operation?”. It is also possible to anticipate and address likely anxieties such as “Will it be painful?”; “Will I get better?”; or “Will I die?”.

Jargon can be an important communication aid between professionals in the same field, but it is important to avoid using technical jargon and clinical acronyms with patients. Even though they may not understand, they may not ask you for a plain English translation. It is easy to slip into jargon without realising it, so make a conscious effort to avoid it.

A report on health literacy from the Royal College of General Practitioners (2014) cited the example of a patient who took the description of a “positive cancer diagnosis” to be good news, when the reverse was the case. If you have to use jargon, explain what it means. Wherever possible, keep medical terms as simple as possible – for example, kidney, rather than renal and heart, not cardiac. The Plain English website contains examples of healthcare jargon.

Box 3 gives advice on how to avoid jargon when speaking with patients.

Box 3. Avoiding jargon

- Avoid ambiguity: words with one meaning for a nurse may have another in common parlance – for example, ‘acute’ or ‘stool’

- Use appropriate vocabulary for the audience and age-appropriate terms, avoiding childish or over-familiar expressions with older people

- Avoid complex sentence structures, slang or speaking quickly with patients who are not fluent in English

- Use easy-to-relate-to analogies when explaining things: “Your bowel is a bit like a garden hose”

- Avoid statistics such as “There’s an 80% chance that …” as even simple percentages can be confusing. “Eight in every 10 people” humanises the statistic

Values, beliefs and assumptions

Everyone makes assumptions based on their social or cultural beliefs, values, traditions, biases and prejudices. A patient might genuinely believe that female staff must be junior, or that a man cannot be a midwife. Be alert to patients’ assumptions that could lead to misinterpretation, reinterpretation, or even them ignoring what you are telling them. Think about how you can address such situations; for example explain your role at the outset: “Hello, I am [your name], the nurse practitioner who will be examining you today.”

It is important to be aware of your own assumptions, prejudices and values and reflect on whether they could affect your communication with patients. A nurse might assume that a patient in a same-sex relationship will not have children, that an Asian patient will not speak good English, or that someone with a learning disability or an older person will not be in an active sexual relationship. Incorrect assumptions may cause offence. Enquiries such as asking someone’s “Christian name” may be culturally insensitive for non-Christians.

Information overload

We all struggle to absorb lots of facts in one go and when we are bombarded with statistics, information and options, it is easy to blank them out. This is particularly so for patients who are upset, distressed, anxious, tired, in shock or in pain. If you need to provide a lot of information, assess how the patient is feeling and stick to the pertinent issues. You can flag up critical information by saying: “You need to pay particular attention to this because …”.

Box 4 provides tips on avoiding information overload.

Box 4. Avoiding information overload

- Consider suggesting that your patient involves a relative or friend in complex conversations – two pairs of ears are better than one. However, be aware that some patients may not wish others to know about their health

- Suggest patients take notes if they wish

- With patients’ consent, consider making a recording (or asking whether the patient wishes to record part of the consultation on their mobile phone) so they can replay it later or share it with a partner who could not accompany them

- Give written information to supplement or reinforce the spoken word

- Arrange another meeting if necessary to go over details again or to provide further information

It is vital that all nurses are aware of potential barriers to communication, reflect on their own skills and how their workplace environment affects their ability to communicate effectively with patients. You can use this article and the activity in Box 5 to reflect on these barriers and how to improve and refine your communication with patients.

Box 5. Reflective activity

Think about recent encounters with patients:

- What communication barriers did you encounter?

- Why did they occur?

- How can you amend your communication style to take account of these factors so that your message is not missed, diluted or distorted?

- Do you need support to make these changes?

- Who can you ask for help?

- Nurses need to be aware of the potential barriers to communication and adopt strategies to address them

- Environmental factors such as background noise can affect patients’ ability to hear and understand what is being said to them

- Acute illness, distress and pain can reduce patients’ concentration and their ability to absorb new information

- Anticipating potential embarrassment and taking steps to minimise it can facilitate difficult conversations

- It is important to plan ahead and identify the best place and time to have important conversations

Also in this series

- Communication skills 1: benefits of effective communication for patients

- Communication skills 3: non-verbal communication

- Communication 4: the influence of appearance and environment

- Communication 5: effective listening and observation skills

- Communication skills 6: difficult and challenging conversations

Related files

171220 communication skills 2 overcoming barriers to effective communication.

- Add to Bookmarks

Related articles

Have your say.

Sign in or Register a new account to join the discussion.

Dissecting Communication Barriers in Healthcare: A Path to Enhancing Communication Resiliency, Reliability, and Patient Safety

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Human Factors and Behavioral Neurobiology, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Daytona Beach, Florida.

- 2 Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland.

- PMID: 30418425

- DOI: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000541

Suboptimal exchange of information can have tragic consequences to patient's safety and survival. To this end, the Joint Commission lists communication error among the most common attributable causes of sentinel events. The risk management literature further supports this finding, ascribing communication error as a major factor (70%) in adverse events. Despite numerous strategies to improve patient safety, which are rooted in other high reliability industries (e.g., commercial aviation and naval aviation), communication remains an adaptive challenge that has proven difficult to overcome in the sociotechnical landscape that defines healthcare. Attributing a breakdown in information exchange to simply a generic "communication error" without further specification is ineffective and a gross oversimplification of a complex phenomenon. Further dissection of the communication error using root cause analysis, a failure modes and effects analysis, or through an event reporting system is needed. Generalizing rather than categorizing is an oversimplification that clouds clear pattern recognition and thereby prevents focused interventions to improve process reliability. We propose that being more precise when describing communication error is a valid mechanism to learn from these errors. We assert that by deconstructing communication in healthcare into its elemental parts, a more effective organizational learning strategy emerges to enable more focused patient safety improvement efforts. After defining the barriers to effective communication, we then map evidence-based recovery strategies and tools specific to each barrier as a tactic to enhance the reliability and validity of information exchange within healthcare.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Communication Barriers

- Communication*

- Delivery of Health Care

- Medical Errors / prevention & control

- Patient Safety*

- Reproducibility of Results

- Safety Management

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2024

Comparison of barriers to effective nurse-patient communication in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 wards

- Hamed Bakhshi ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0008-7865-0149 1 ,

- Mohammad Javad Shariati ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0000-5518-698X 1 ,

- Mohammad Hasan Basirinezhad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3672-556X 2 &

- Hossein Ebrahimi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5731-7103 3

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 328 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

180 Accesses

Metrics details

Communication is a basic need of humans. Identifying factors that prevent effective nurse-patient communication allows for the better implementation of necessary measures to modify barriers. This study aims to compare the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication from the perspectives of nurses and patients in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 wards.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted in 2022. The participants included 200 nurses (by stratified sampling method) and 200 patients (by systematic random sampling) referred to two conveniently selected hospitals in Shahroud, Iran. The inclusion criteria for nurses were considered having at least a bachelor’s degree and a minimum literacy level for patients to complete the questionnaires. Data were collected by the demographic information form and questionnaire with 30 and 15 questions for nurses and patients, which contained similar questions to those for nurses, based on a 5-point Likert scale. Data were analysis using descriptive indices and inferential statistics (Linear regression) in SPSS software version 18.

The high workload of nursing, excessive expectations of patients, and the difficulty of nursing work were identified by nurses as the main communication barriers. From the patients’ viewpoints, the aggressiveness of nurses, the lack of facilities (welfare treatment), and the unsanitary conditions of their rooms were the main communication barriers. The regression model revealed that the mean score of barriers to communication among nurses would decrease to 0.48 for each unit of age increase. Additionally, the patient’s residence explained 2.3% of the nurses’ barriers to communication, meaning that native participants obtained a mean score of 2.83 units less than non-native nurses, and there was no statistically significant difference between the COVID and non-COVID wards.

In this study, the domain of job characteristics was identified by nurses as the major barrier, and patients emphasized factors that were in the domain of individual/social factors. There is a pressing need to pay attention to these barriers to eliminate them through necessary measures by nursing administrators.

Peer Review reports

First observed in Wuhan, China, the COVID-19 pandemic is an acute and very severe respiratory syndrome that the World Health Organization has raised as a health problem because of its high spread rate and consequences on an international scale. The number of COVID-19 patients is increasingly on the rise [ 1 , 2 ]. Illness and hospitalization are usually stressful and associated with bad experiences for patients and their family members [ 3 ].

According to Tabandeh Sadeghi et al. (2011) “Communication is a basic need of humans. Any interaction is an opportunity to achieve effective communication and participation in understanding the issue, which leads to the achievement of mutual goals by individuals.” [ 4 ]. The three important aspects of communication that are emphasized the most are the message’s sender, the receiver, and the environment. Communicating is an interaction between the sender and the receiver of the message, and the environment affects them [ 5 , 6 ]. In the context of a hospital, these three aspects of communication can be defined as nurse, patient, and hospital environment, and all three should be considered when examining the obstacles [ 7 ]. “According to Ali Fakhr Movahedi et al. (2012)” Communication is considered a central concept in nursing and an essential part of nursing work [ 8 ]. Patients perceive interaction with nurses as the basis of their treatment [ 9 ]. Nurse-patient communication is an interpersonal process that is created between these two groups during treatment. This process generally includes the start, work, and end stages. Effective communication is an essential aspect of patient care by nurses, and many nursing tasks cannot be performed without this activity [ 10 ]. Effective communication consists of explicit transmission and receipt of message content, in which information is consciously and unconsciously produced by a person and communicated to the recipient through verbal and non-verbal patterns [ 11 ]. The non-verbal aspect of communication plays an essential role and is more important than the verbal aspect of language in emergencies. The mandatory use of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic negatively influenced nurse-patient communication, notably because this tool significantly reduced the messages arising from non-verbal communication channels [ 12 ]. In this regard, Vitale et al. investigated wearing face masks as a communication barrier between nurses and patients. The results showed no differences in the patients’ opinions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic; patients believed that the mask was not a communication barrier, while nurses thought that wearing masks was a communication barrier [ 12 ]. Unfavorable communication can hamper the patient’s recovery and may even permanently deprive the patient of health or life.

In comparison, good communication affects the patient’s recovery more than medication. In fact, nurses will succeed in their tasks when they can communicate well with their patients [ 13 ]. Effective communication can affect pain control, adherence to a treatment regimen, and the patient’s mental health and play an important role in reducing the patient’s anxiety and fear and faster recovery [ 14 ]. During good communication, patients can disclose and express sensitive and personal information. Consequently, nurses can also transfer necessary information, attitudes, or skills [ 4 ]. Identifying factors that prevent effective nurse-patient communication allows for the better implementation of measures required to adjust obstacles [ 15 ].

The first published reports of the deaths of coronavirus-infected doctors during caring for patients indicate that the virus transmission to healthcare workers in healthcare centers is a hazardous issue [ 16 , 17 ]. Under these stressful conditions, nurses must manage long shift hours and the fear of contagion and overcome communication difficulties through layers of personal protective equipment. These problems may disrupt communication with patients and cause less focus of health workers on the psychosocial well-being of patients [ 18 , 19 ]. Baillie states that the lack of time is a clear barrier to communication between emergency nurses and patients [ 20 ]. Meehan et al. also reported that nurses mentioned the lack of time, fatigue, and workload of personnel to be the factors preventing nurse-patient interaction. In the same research, patients cited the issue of gender as a factor preventing their interaction with nurses. However, male and female patients had difficulty communicating with male nurses [ 21 ].

Identifying factors that prevent effective nurse-patient communication makes it possible to elucidate the direction of necessary measures for the planners and executives of the health sector to eliminate or modify barriers. In particular, when these barriers are identified and expressed with a realistic approach, i.e., from nurses’ and patients’ perspectives [ 22 ]. Before this, no study compared barriers to nurse-patient communication in COVID and non-COVID wards. Therefore, this research aims to compare the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication from nurses’ and patients’ perspectives in COVID-19 and NON-COVID-19 wards. Hopefully, identifying these obstacles and planning to solve them as soon as possible will make us have nurses in the future who can communicate well with patients and improve service delivery.

Study design

This cross-sectional descriptive research was conducted on 200 nurses and 200 patients at hospitals affiliated with the Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. The participants included nurses and patients from different wards of two conveniently selected hospitals in Shahroud. To sample nurses by the stratified method, the sample size was first divided by the total number of nurses in the mentioned hospitals to obtain the sampling fraction. According to Mohammadi et al. study, standard deviations reported for all subscales for barrier’s to effective communication (individual/social factors = 6.22), job characteristics = 6.74, patient’s clinical conditions = 4.22), and environmental factors = 9.09) were utilized to estimate the sample size [ 23 ]. Estimation error was considered 0.15 of standard deviation values. The confidence levels and power were considered at 0.95 and 0.8 respectively with a 15% dropout probability. Also, another sample size was calculated similarly using the standard deviation reported in Norouzinia et al. study for patient’s questionnaire equal to 1.96 [ 24 ]. Finally, among the estimated values; the largest number (200) was considered as the sample size of the present study for nurses and patients.

Considering that the total number of nurses is around 700 and the sample size calculated by the statistics consultant is 200 nurses, our sampling fraction was calculated as \(\frac{2}{7}\) . Therefore, \(\frac{2}{7}\) personnel of each department were included in the study. The patients were sampled by a systematically random method using the hospital list, file number, and dates of admission and discharge. The inclusion criteria for nurses were a bachelor’s degree or higher and a minimum literacy level for patients to complete the questionnaire. Moreover, the questionnaire contained questions about the nurses’ work experience or no experience in COVID-19 wards. The duration of working in COVID-19 wards was included in the questionnaire questions, and the duration was considered in the analysis. Data were collected using a questionnaire provided to the nurses through daily visits to various wards of the mentioned hospitals, including emergency, surgery, special care, internal medicine, gastroenterology, cardiology, urology, orthopedics, ICU, CCU, and other wards. The questionnaire was also provided to the patients hospitalized in surgery, special care, internal medicine, gastroenterology, cardiology, urology, ICU, and CCU wards, among others. Due to the reduced coronavirus spread during that period, the information on COVID-19 patients was accessed using hospital information by obtaining permission, and the questionnaire was completed through phone calls.

Measurements

Demographic information form.

It contained questions about information related to age, gender, marital status, language, and residence.

Communication barrier questionnaire

The barriers to effective nurse-patient communication were investigated using the same questionnaire designed by Anoosheh et al. This questionnaire contains 30 items for nurses and aims to evaluate nurses’ views about the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. The response of this questionnaire is in the Likert range (completely false = 1, false = 2, I have no opinion = 3, agree = 4, and completely agree = 5). The nurses’ questionnaire contains four dimensions, and the question numbers of each dimension include individual/social factors (1–8), occupational characteristics (9–17), patient’s clinical conditions (18–21), and environmental factors (22–30). The domain of individual/social factors includes questions such as the gender difference between the patient and the nurse, age difference, aggressiveness of nurses, etc. The domain of job characteristics includes questions about the high workload of nursing, the difficulty of nursing work, the low salaries of nurses, etc. The domain of the patient’s clinical condition also includes questions such as the severity of the disease, the presence of the patient’s companion, etc. The domain of environmental factors: where communication occurs is important. The nurse and the patient should feel calm and safe in the treatment environment. This domain also includes questions such as the Lack of facilities (welfare - treatment) for patients, the unsanitary condition of the patient’s room, the High cost of treating patients, etc. A pilot study was carried out to assess the face validity among nurses. In addition, the content validity was assessed by estimation of content validity ratio and content validity index among nursing educators. The internal consistency for the present questionnaire assessed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient equal to 0.96 [ 25 ].

The patient questionnaire contains 15 questions and aims to evaluate the patients’ views about the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. The response of this questionnaire is in the Likert range (completely false = 1, false = 2, I have no opinion = 3, agree = 4, and completely agree = 5). No separate dimension was considered for the patient questionnaire. The reliability based on internal consistency was reported using Cronbach’s alpha equal to 0.91 [ 25 ]. The total score of the questionnaire is obtained by summing up the total scores of all questions. The score of each dimension is obtained from the sum of scores for each question of that dimension. Higher scores in each dimension indicate the greater strength of that dimension as a barrier to effective nurse-patient communication and vice versa. After completing the communication barrier questionnaire, a separate question was asked from the patients and nurses about whether or not the face mask was a communication barrier. This question was scored with a Likert scale (completely false = 1, false = 2, I have no opinion = 3, agree = 4, and completely agree = 5). The score of this question was measured separately from the nurse-patient communication barrier questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

Initially, necessary permissions were obtained from the Vice Chancellor of Research and Technology and the Research Ethics Council (code of ethics: IR.SHMU.REC.1401.140) at the Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. Necessary coordination was also made with the administrators of two conveniently selected hospitals in Shahroud. After explaining the purpose of the research and answering the questions of nurses and patients regarding the questionnaire and how to complete them, enough time was given to answer them.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential tests (Linear regression) in SPSS software version 18. All variables with a significance level of less than 0.2 are included in the final regression model. A significance level of 0.05 was considered. Considering that one of the purposes of this study is to determine the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication based on demographic information, three participants were excluded from the data analysis due to a lack of demographic information completion.

The average ages of nurses and patients were respectively 33.28 and 38.57 years, and most nurses (85.3%) and patients (61.5%) were females and males, respectively. Other demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1 .

In this study, the mean score obtained for each domain of the barriers to nurse-patient communication was determined from the nurses’ point of view. According to these results, the highest score with an average of 32.41 ± 6.75 related to the domain of job characteristics, and the lowest score with an average of 11.76 ± 3.17 related to the domain of Patient’s Clinical Conditions. Additional information is presented in Table 2 .

The excessive patients’ expectations in the domain of individual/social factors, the high workload of nursing in the domain of job characteristics, the severity of the disease in the domain of the patient’s clinical conditions, and no appreciation for nurses by authorities in the domain of environmental factors were the major communication barriers. The patient-nurse age difference from the domain of individual/social factors, the patient’s contact with multiple nurses with different attitudes from the domain of job characteristics, previous hospitalization history from the domain of the patient’s clinical conditions, and the high cost of patient treatment from the domain of environmental factors were the least important barriers to communication from the nurses’ viewpoints. From the patients’ views, the aggressiveness of nurses and the patient-nurse age difference were the major and the minor barriers to communication, respectively. Face masks were among the minor barriers to nurse-patient communication from the viewpoints of both groups (Table 3 ); this table is placed at the end of the article.

The relationship between nurses’ age and communication barriers was investigated using a regression model. This model was first run as a univariate type, and variables with a significance of < 0.2 were introduced into a multivariate model using the backward method. Finally, the model showed that the nurses’ age variable explained 3.8% of the score variance. In other words, the regression model revealed that the mean score of nurses would decrease to 0.486 for each year of age increase, and there is no statistically significant difference between the COVID and non-COVID wards (Table 4 ).

Additionally, the patient’s residence variable explained 2.3% of the score variance, meaning that native people obtained a mean score of 2.813 units less than non-native people, and there is no statistically significant difference between the COVID and non-COVID wards (Table 5 ).

The present study aimed to determine the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication from the viewpoints of nurses and patients in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 wards in hospitals affiliated with the Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. The results of this study showed that in the domains of barriers to effective communication, nurses reported the highest score in job characteristics and the lowest score in the patient’s clinical conditions. In a study on nursing students at Urmia Midwifery School of Nursing, Habibzadeh et al. (2017) reported the highest and the lowest mean scores for questions related to occupational characteristics and the patient’s clinical conditions [ 26 ], which corresponds to our results. Work congestion conditions increase the work pressure of nurses, leading to fatigue, a situation in which nurses lack enough time to discover the patient’s concerns [ 27 ]. Stress and pressure caused by time constraints often result in miscommunication and reduce the satisfaction of nurses and patients [ 28 ].

The results of this study showed that the high workload of nursing and excessive expectations of patients are mentioned as two major obstacles to effective communication with patients from the point of view of nurses. Anoushe et al. (2015) and Baraz Pordanjani et al. (2016) investigated barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. They reported that nurses identify their workload as a major barrier to effective patient communication [ 15 , 22 ]. However, Habibzadeh et al. (2017) claimed that nurses’ lack of information and skills in patient communication was identified as the main communication barrier [ 26 ]. A possible reason for this discrepancy might be that the current study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, concurrent with the increased workload of nurses compared to the pre-pandemic period.

The difficulty of nursing work, the psychophysical fatigue of nurses, the lack of comfort facilities for nurses, and no appreciation for nurses by administrators are in the next ranks of importance. Similarly, Anoushe et al. (2005) reported the difficulty of nursing work, the lack of comfort facilities for nurses, and psychophysical fatigue among the barriers with more emphasis by nurses [ 22 ]. The notable point is that nurses do not have the opportunity to establish effective communication with patients due to their workload. Furthermore, their work type is hard and tiring, and they do not receive proper benefits or appreciation. In such a situation, one cannot expect good nurse-patient communication, and the conditions affect patients’ moods. As expressed by the patients, this issue also negatively affects the quality of their relationships with patients [ 15 ].

The aggressiveness of nurses mentioned as the main obstacle to effective communication with patients from the patients’ point of view. Likewise, Baraz Pordanjani et al. (2009) found a statistically significant difference between the aggressiveness of nurses from the perspectives of nurses and patients [ 15 ].

Regarding the communication barriers from the patient’s perspective, the lack of facilities (welfare treatment) for them and the unsanitary condition of their rooms were among the factors more emphasized by patients than by the nurses. Interestingly, Baraz Pordanjani et al. observed that nurses believed more than patients that the lack of comfort facilities for patients and the unsanitary condition of their rooms would hinder effective communication [ 15 ]. This contradictory result can result from the difference in facilities and health/treatment conditions of the studied hospitals.

The viewpoints of both nurse and patient groups show that age and class differences do not negatively influence their relationships. Since nurses are responsible for initiating and maintaining communication with patients, it can be claimed that they perform their professional tasks, including communication establishment, regardless of the social class and age of patients, who also acknowledge this issue.

The face mask also obtained a low score from the viewpoints of patients and nurses. Vitale et al. investigated the use of face masks as a communication barrier between nurses and patients. The results indicated no difference in the patients’ opinions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic; that is, patients did not consider the mask a communication barrier, which is consistent with the present study. However, nurses thought that using a mask would be a communication barrier [ 12 ].

The present results revealed a significant relationship between the age of nurses and the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication; as such, the total score of nurses decreased for each year of age increase; However, no statistically significant difference was observed in the comparison of COVID and non-COVID wards. In this regard, Gopichandran et al. (2021) aimed to determine communication barriers between doctors and patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. They claimed that communication barriers decreased with age [ 29 ]. Nurses gain more experience and skills with rising age. Enough experience is also a characteristic that patients consider necessary for nursing work [ 30 ]. “According to Aram Feizi et al. (2006)” Mark (2001) concluded that the experience of the nursing unit could create satisfaction in both nurses and patients [ 30 ]. The possible reason for obtaining different results could be that the COVID-19 vaccination process was carried out slowly in Iran. For this reason, the nurses, both in the COVID and non-COVID wards, considered all patients with unique viewpoints (all of the patients considered potential cases of COVID-19). For this reason, there was no statistical difference between the communication barriers of the COVID and non-COVID departments.

No statistically significant difference was observed between the scores of male and female nurses and the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. Unlike this result, Mohammadi et al. (2013) reported a significant difference between job characteristics, patients’ clinical conditions, environmental factors, and the gender of nurses [ 23 ]. The discrepant results might be caused by the heterogeneous distribution of participants in terms of gender, as 56% of the nurses were male in the study of Mohammadi et al. In comparison, less than 20% of the participants were male nurses in the present study.

The present results showed that the patients’ residence was significantly related to the barriers to effective nurse-patient communication, and native people obtained a lower mean score than non-native people: However, there was no any no significant difference between COVID and NON-COVID wards This result might be because nurses are more informed of the accents and dialects of native patients. Caring for patients speaking different languages and accents can lead to problems in the quantity and quality of nurse-patient communication. When patients and caregivers have different cultural values and languages, communication can cause the inability to exchange information [ 27 ]. Tilki and Okoughan presented evidence that differences in spoken language could hinder effective communication [ 31 ]. On the other hand, the results of the study by Vitale et al. showed that there was no difference between the patients before and during the covid-19 pandemic, which is consistent with the results of the present study [ 12 ].

Limitations

Among the limitations of this study, we can mention the low response rate by nurses and patients, which was completed with the continuous presence of the researcher. Since this research is conducted only in public medical centers affiliated to Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, the results may not be generalizable to centers affiliated with other universities of medical sciences in Iran and non-academic centers such as private medical centers. It is recommended that future research be conducted in larger settings.

This study demonstrated that nurses identified the domain of job characteristics as the most critical barrier among the four domains of barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. Patients more emphasized factors that were in the domain of individual/social factors. There is a pressing need to pay attention to these barriers to eliminate them through necessary measures by nursing officials. Hopefully, the elimination of these barriers in the future will lead to nurses who can communicate well with patients and improve service delivery.

Implications

This research helps to identify barriers to effective communication between nurses and patients. In the field of policy and management, the results of this research can help to plan for effective nurse-patient communication. In the field of education, according to the results of this article, necessary training should be given to nurses and patients regarding communication barriers to help improve communication. There will be a basis for further, more comprehensive research in the field of research. Hopefully, these results can help nursing officials and nurses remove communication barriers and improve service delivery.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, Health Care Workers, and Health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(18):2352–71.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Situation Report– 161. 2020.[cited 2020 June 29] https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200629-covid-19-sitrep-161.pdf?sfvrsn=74fde64e_2 .

Sheldon LK, Barrett R, Ellington L. Difficult communication in nursing. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38(2):141–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Sadeghi T, Dehghan Nayyeri N, Karimi R. Nursing-patient relationship: a comparison between nurses and adolescents perceptions. Iran J Med Ethics History Med. 2011;4(3):69–78.

Google Scholar

Caris-Verhallen WM, De Gruijter IM, Kerkstra A, Bensing JM. Factors related to nurse communication with elderly people. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30(5):1106–17.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kopp P. Better communication with older patients. Professional nurse (London, England). 2001;16(8):1296-9.

Aghamolaei T, Hasani L. Communication barriers among nurses and elderly patients. Hormozgan Med J. 2011;14(4):312–8.

Fakhr-Movahedi A, Negarandeh R, Salsali M. Exploring nurse-patient communication strategies. J Hayat. 2013;18(4):28–46.

Kettunen T, Poskiparta M, Gerlander M. Nurse-patient power relationship: preliminary evidence of patients’ power messages. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47(2):101–13.

Hagerty BM, Patusky KL. Reconceptualizing the nurse-patient relationship. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35(2):145–50.

Clancy CM, Farquhar MB, Sharp BA. Patient safety in nursing practice. J Nurs Care Qual. 2005;20(3):193–7.

Vitale E, Giammarinaro MP, Lupo R, Archetta V, Fortunato RS, Caldararo C, et al. The quality of patient-nurse communication perceived before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: an Italian pilot study. Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S2):e2021035.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jan Mohamady S, Salami S, Abasi Marei F, Masror D, Nazary Jobrany M. F J. Civilization and Nursing.Tehran: Publication Salemi2002. 107-9 p.

Maskor NA, Krauss SE, Muhamad M, Nik Mahmood NH. Communication competencies of oncology nurses in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(1):153–8.

Baraz Pordanjani S, Shariati A, Alijani H, Moein Mosavi B. Assessing barriers of nurse-patient’s effective communication in educational hospitals of Ahwaz. Iran J Nurs Res. 2010;5(16):45–52.

Bowdle A, Munoz-Price LS. Preventing infection of patients and Healthcare workers should be the New Normal in the era of Novel Coronavirus Epidemics. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(6):1292–5.

Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67(5):568–76.

Fritzsche K, Scheib P, Ko N, Wirsching M, Kuhnert A, Hick J, et al. Results of a psychosomatic training program in China, Vietnam and Laos: successful cross-cultural transfer of a postgraduate training program for medical doctors. Biopsychosoc Med. 2012;6(1):17.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Eltaybani S, Igarashi A, Cal A, Lai CK, Carrasco C, Sari DW et al. Long-term care facilities’ response to the COVID‐19 pandemic: An international, cross‐sectional survey. J Adv Nurs. 2023.

Baillie L. An exploration of nurse-patient relationships in accident and emergency. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2005;13(1):9–14.

Cleary M, Edwards C, Meehan T. Factors influencing nurse–patient interaction in the acute psychiatric setting: an exploratory investigation. Aust N Z J Mental Health Nurs. 1999;8(3):109–16.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Anoosheh M, Zarkhah S. Investigating barriers to effective nurse-patient communication. Teb Tazkie. 2006;15(2):49–57.

Mohammadi I, Mozafari M, Beigi EJ, Kaikhavani S. Barriers to effective nurse- patient communication from perspective of nurses employed in Educational hospitals of Ilam. J Neyshabur Univ Med Sci. 2015;2(3):20–7.

Norouzinia R, Aghabarari M, Shiri M, Karimi M, Samami E. Communication barriers perceived by nurses and patients. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(6):65–74.

Anoosheh M, Zarkhah S, Faghihzadeh S, Vaismoradi M. Nurse-patient communication barriers in Iranian nursing. Int Nurs Rev. 2009;56(2):243–9.

Habibzadeh H, Dehgannejad J, Hoseinzadeghan F, Bafandehzendeh M. Barriers to establishing Effective Communication between Nurse and Patient according to nursing students’ viewpoints Urmia nursing and midwifery Faculty. Nurs Midwifery J. 2019;17(9):696–704.

Mazhariazad F, Taghadosi M, Erami E. Challenges of nurse-patient communication in Iran: a review study. Sci J Nurs Midwifery Paramedical Fac. 2019;4(4):15–29.

Jahromi MK, Ramezanli S. Evaluation of barriers contributing in the demonstration of an effective nurse-patient communication in educational hospitals of Jahrom, 2014. Global J Health Sci. 2014;6(6):54.

Gopichandran V, Sakthivel K. Doctor-patient communication and trust in doctors during COVID 19 times-A cross sectional study in Chennai, India. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0253497.

Feizi A, Mohammadi R, Nikravesh M. Factors causing patient’s Trust in Nurse from patients’ perspective. Razi J Med Sci. 2006;13(52):177–87.

Okougha M, Tilki M. Experience of overseas nurses: the potential for misunderstanding. Br J Nurs. 2010;19(2):102–6.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The present study is a research project approved under the number 14010048 at Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. The researchers are grateful to the Vice Chancellor of Research and Technology at Shahroud University of Medical Sciences for the necessary financial support of the present study and the participating nurses and patients.

No funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

Hamed Bakhshi & Mohammad Javad Shariati

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

Mohammad Hasan Basirinezhad

Center for Health Related Social and Behavioral Sciences Research, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

Hossein Ebrahimi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of the article: design and writing of the article (HB, HE), data collection (HB, MS), analysis and interpretation of data (HB, MB), final approval of the submitted version (HE, HB).

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hossein Ebrahimi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

In order to observe ethical considerations, after explaining the study objectives and method to nurses and patients, written informed consent was obtained from them. It should be noted that the principles of the Helsinki Declaration, including the right to enter the research freely, no harm or loss to participants, maintaining the right to withdraw from the study, and confidentiality of information, were observed in this study. Besides, the researchers committed themselves to adhering to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) set out for the publication of the results. This cross-sectional study was approved by the ethics committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences with the registration number: IR.SHMU.REC.1401.140.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bakhshi, H., Shariati, M., Basirinezhad, M. et al. Comparison of barriers to effective nurse-patient communication in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 wards. BMC Nurs 23 , 328 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01947-4

Download citation

Received : 05 August 2023

Accepted : 18 April 2024

Published : 16 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01947-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Communication barriers

- Communication

- Nurse–patient communication

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Ali M. Communication skills 1: benefits of effective communication for patients. Nursing Times. 2017; 113:(12)18-19

Barber C. Communication, ethics and healthcare assistants. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants. 2016; 10:(7)332-335 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjha.2016.10.7.332

Berlo DK. The process of communication; an introduction to theory and practice.New York (NY): Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1960

Bramhall E. Effective communication skills in nursing practice. Nurs Stand. 2014; 29:(14)53-59 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.14.53.e9355

Bumb M, Keefe J, Miller L, Overcash J. Breaking bad news: an evidence-based review of communication models for oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017; 21:(5)573-580 https://doi.org/10.1188/17.CJON.573-580

Caldwell L, Grobbel CC. The importance of reflective practice in nursing. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2013; 6:(3)319-326

Communication skills for workplace success employers look for these communication skills. The Balance (online). 2019. http://tinyurl.com/yyx3eeoy (accessed 27 June 2019)

Evans N. Knowledge is power when it comes to coping with a devastating diagnosis. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2017; 16:(10)8-9 https://doi.org/10.7748/cnp.16.10.8.s7

Gibbs G. Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods.Oxford: Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic; 1988

Gillett A, Hammond A, Martala M. Successful academic writing.Harlow: Pearson Education Limited; 2009

Hanratty B, Lowson E, Holmes L Breaking bad news sensitively: what is important to patients in their last year of life?. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2012; 2:(1)24-28 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000084

Hemming L. Breaking bad news: a case study on communication in health care. Gastrointestinal Nursing. 2017; 15:(1)43-50 https://doi.org/10.12968/gasn.2017.15.1.43

Macmillan Cancer Support. Cancer clinical nurse specialists (Impact Briefs series). 2014. http://tinyurl.com/yb96z88j (accessed 27 June 2019)

Healthcare professionals: acknowledging emotional reactions in newly-diagnosed patients. 2012. http://www.justgotdiagnosed.com (accessed 27 June 2019)

Oelofsen N. Using reflective practice in frontline nursing. Nurs Times. 2012; 108:(24)22-24

Paterson C, Chapman J. Enhancing skills of critical reflection to evidence learning in professional practice. Phys Ther Sport. 2013; 14:(3)133-138 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.03.004

Pincock S. Poor communication lies at heart of NHS complaints, says ombudsman. BMJ. 2004; 328 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7430.10-d

Royal College of Nursing. Revalidation requirements: reflection and reflective discussion. 2019. http://tinyurl.com/yy8l68cy (accessed 27 June 2019)

Schildmann J, Cushing A, Doyal L, Vollmann J. Breaking bad news: experiences, views and difficulties of pre-registration house officers. Palliat Med. 2005; 19:(2)93-98 https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216305pm996oa

Shipley SD. Listening: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2010; 45:(2)125-134 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2010.00174.x

Reflecting on the communication process in health care. Part 1: clinical practice—breaking bad news

Beverley Anderson

Macmillan Uro-oncology Clinical Nurse Specialist, Epsom and St Helier NHS Trust

View articles · Email Beverley

This is the first of a two-part article on the communication process in health care. The interactive process of effective communication is crucial to enabling healthcare organisations to deliver compassionate, high-quality nursing care to patients, in facilitating interactions between the organisation and its employees and between team members. Poor communication can generate negativity; for instance, misperception and misinterpretation of the messages relayed can result in poor understanding, patient dissatisfaction and lead to complaints. Reflection is a highly beneficial tool. In nursing, it enables nurses to examine their practice, identify problems or concerns, and take appropriate action to initiate improvements. This two-part article examines the role of a uro-oncology clinical nurse specialist (UCNS). Ongoing observations and reflections on the UCNS's practice had identified some pertinent issues in the communication process, specifically those relating to clinical practice and the management of practice-related issues and complaints. Part 1 examines the inherent problems in the communication process, with explanation of their pertinence to delivering optimal health care to patients, as demonstrated in four case studies related to breaking bad news to patients and one scenario related to communicating in teams. Part 2 will focus on the management of complaints.

In health care, effective communication is crucial to enabling the delivery of compassionate, high-quality nursing care to patients ( Bramhall, 2014 ) and in facilitating effective interactions between an organisation and its employees ( Barber, 2016 ; Ali, 2017 ). Poor communication can have serious consequences for patients ( Pincock, 2004 ; Barber, 2016 ; Ali, 2017 ). Misperception or misinterpretation of the messages relayed can result in misunderstanding, increased anxiety, patient dissatisfaction and lead to complaints ( McClain, 2012 ; Ali, 2017 ; Bumb et al, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ; Doyle, 2019 ), which, as evidence has shown, necessitates efficient management to ensure positive outcomes for all stakeholders—patients, health professionals and the healthcare organisation ( Barber, 2016 ; Ali, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ; Doyle, 2019 ). Complaints and their management will be discussed in Part 2.

Reflection is a highly beneficial tool ( Oelofsen, 2012 ), one that has played a key role in the author's ongoing examination of her practice. In this context, reflection enables a personal insight into the communication process and highlights the inherent challenges of communication and their pertinence to patient care and clinical practice outcomes ( Bramhall, 2014 ). The author, a uro-oncology clinical nurse specialist (UCNS), is required to ensure that appropriate reassurance and support is given to patients following the receipt of a urological cancer diagnosis ( Macmillan Cancer Support, 2014 ; Hemming, 2017 ). Support consists of effective communication, which is vital to ensuring patients are fully informed and understand their condition, prognosis and treatment and, accordingly, can make the appropriate choices and decisions for their relevant needs ( McClain, 2012 ; Ali, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ; Hemming, 2017 ; Doyle, 2019 ).

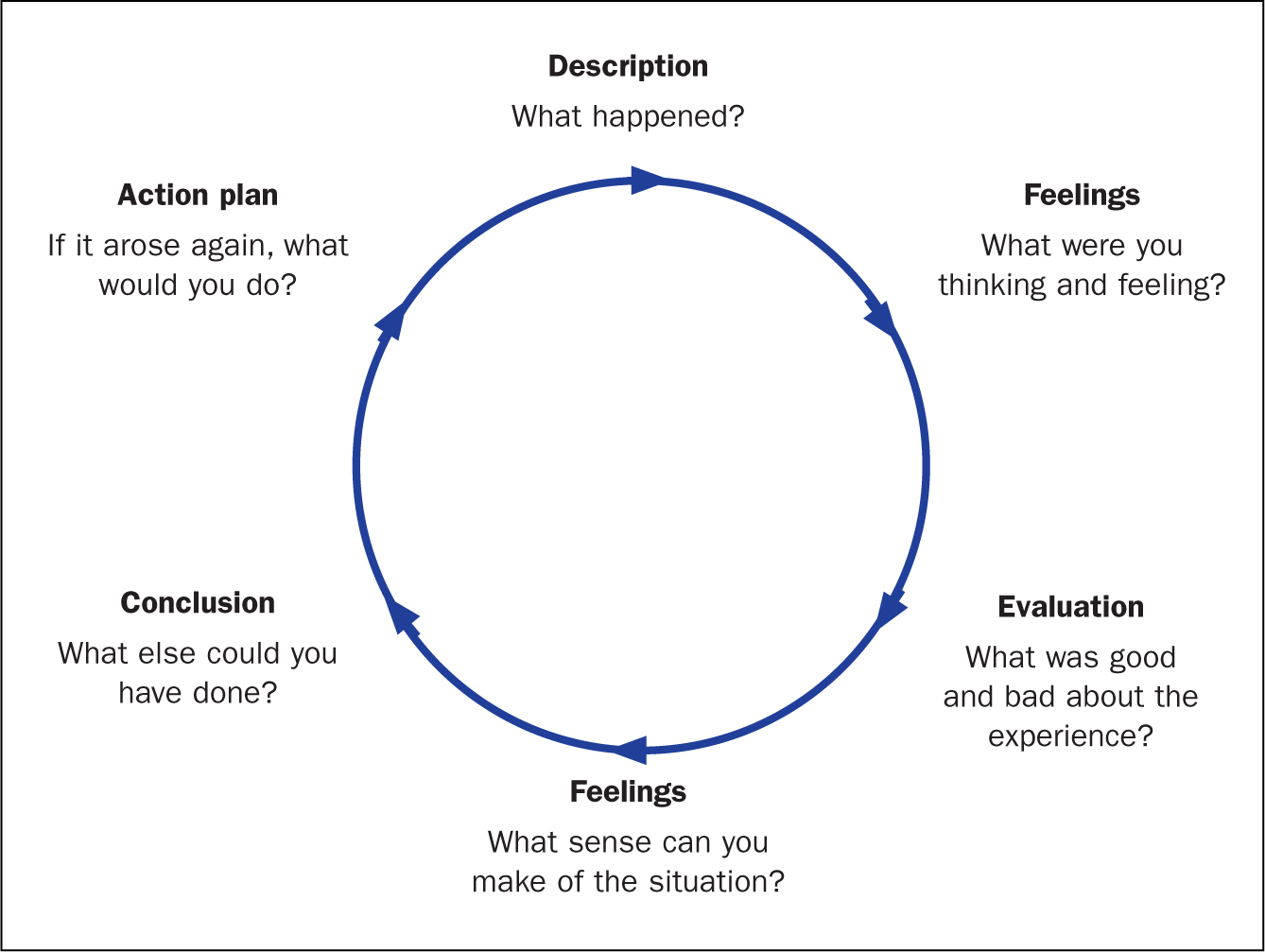

Reflection is a process of exploring and examining ourselves, our perspectives, attributes, experiences, and actions and interactions, which helps us gain insight and see how to move forward ( Gillett et al, 2009:164 ). Reflection is a cycle ( Figure 1 ; Gibbs, 1988 ), which, in nursing, enables the individual to consciously think about an activity or incident, and consider what was positive or challenging and, if appropriate, plan how a similar activity might be enhanced, improved or done differently in the future ( Royal College of Nursing (RCN), 2019 ).

Reflective practice

Reflective practice is the ability to reflect on one's actions and experiences so as to engage in a process of continuous learning ( Oelofsen, 2012 ), while enhancing clinical knowledge and expertise ( Caldwell and Grobbel, 2013 ). A key rationale for reflective practice is that experience alone does not necessarily lead to learning—as depicted by Gibbs' reflective cycle (1988) . Deliberate reflection on experience, emotions, actions and responses is essential to informing the individual's existing knowledge base and in ensuring a higher level of understanding ( Paterson and Chapman, 2013 ). Reflection on practice is a key skill for nurses—it enables them to identify problems and concerns in work situations and in so doing, to make sense of them and to make contextually appropriate changes if they are required ( Oelofsen, 2012 ).

Throughout her nursing career, reflection has been an integral part of the author's ongoing examinations of her practice. The process has enabled numerous opportunities to identify the positive and negative aspects of practice and, accordingly, devise strategies to improve both patient and practice outcomes. Reflection has also been a significant part author's professional development, increasing her nursing knowledge, insight and awareness and, as a result, the author is an intuitive practitioner, who is able to deliver optimal care to her patients.

Communication

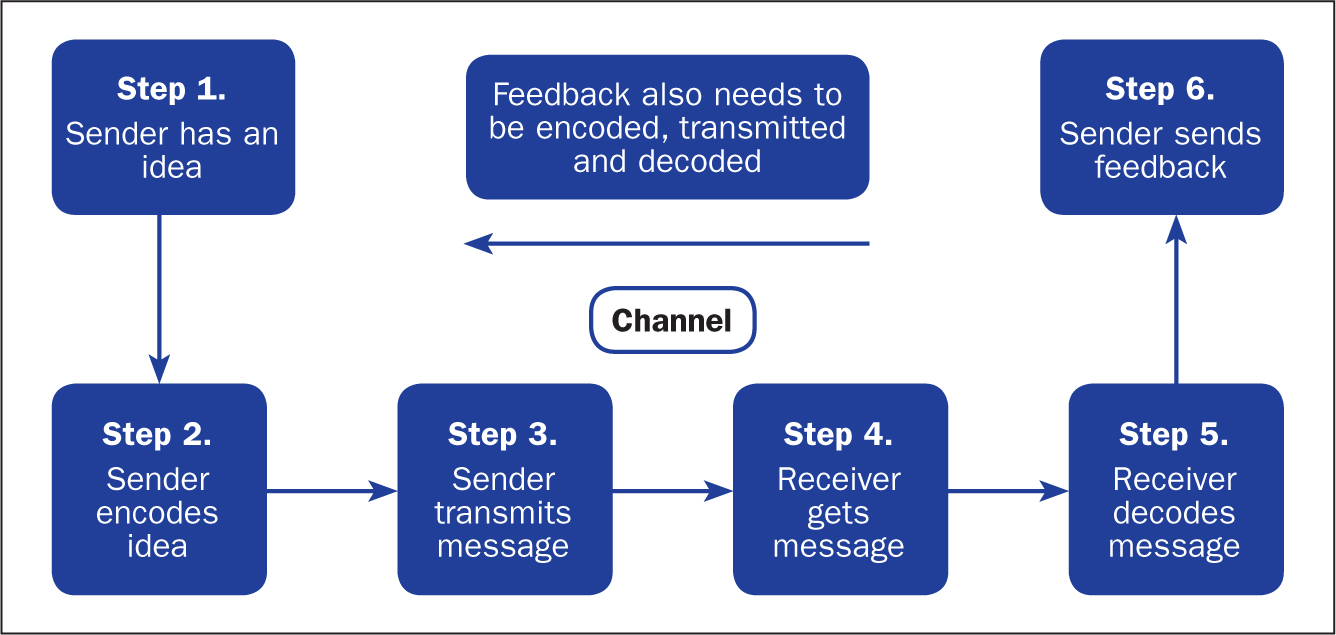

Figure 2 provides a visual image of communication—it is both an expressive, message-sending, and a receptive, message-receiving, process ( Berlo, 1960 ; McClain, 2012 ; Evans, 2017 ). This model was originally designed to improve technical communication, but has been widely applied in different fields ( Berlo, 1960 ). Communication is the sharing of information, thoughts and feelings between people through speaking, writing or body language, via phone, email and social media ( Bramhall, 2014 ; Barber, 2016 ; Doyle, 2019 ). Effective communication extends the concept to require that transmitted content is received and understood by someone in the way it was intended.

The process is more than just exchanging information. It is about the components/elements of the communication process, ie understanding the emotion and intentions behind the information—the tone of voice, as well as the actual words spoken, hearing, listening, perception, honesty, and ensuring that the messages relayed are correctly interpreted and understood ( Bramhall, 2014 ; Barber, 2016 ; Evans, 2017 ; Doyle, 2019 ). It is about considering emotions, such as shock, anger, fear, anxiety and distress ( Bumb et al, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ). Language and conceptual barriers may also negatively impact on the efficacy of the communication being relayed.

Challenges of effective communication

The following sections explain the challenges involved in communication—namely, conveying a cancer diagnosis or related bad news.

Tone of voice and words spoken

According to Barber (2016) , when interacting with patients, especially communicating ‘bad news’ to them, both the tone of voice and the actual words spoken are important. The evidence has shown that an empathetic and sensitive tone is conducive to providing appropriate reassurance and in aiding understanding ( McClain, 2012 ; Evans, 2017 ; Hemming, 2017 ). However, an apathetic and insensitive tone will likely evoke fear, anxiety and distress ( Pincock, 2004 ; Ali, 2017 ; Doyle, 2019 ). In terms of the words used, the use of jargon, or highly technical language and words that imply sarcasm and disrespect, can negatively impact on feelings and self-confidence ( Doyle, 2019 ).

Hearing what is being conveyed is an important aspect of effective communication. When interacting with patients it is vital to consider potential barriers such as language (ie, is the subject highly technical or is English not the patient's first language) and emotions (ie shock, anger, fear, anxiety, distress) ( Bumb et al, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ). A patient may fail to hear crucial information because he or she is distressed during an interaction, or may be unable to fully understand the information being relayed ( Bumb et al, 2017 ). Good communication involves ascertaining what has been heard and understood by the patient, allowing them to express their feelings and concerns, and ensuring these are validated ( Evans, 2017 ).

Listening to the patient

Listening is a deliberate act that requires a conscious commitment from the listener ( Shipley, 2010 ). The key attributes of listening include empathy, silence, attention to both verbal and non-verbal communication, and the ability to be non-judgemental and accepting ( Shipley, 2010 ). Listening is an essential component of effective communication and a crucial element of nursing care ( Shipley, 2010 ; Evans, 2017 ; Doyle, 2019 ). In health care, an inability to fully listen to and appreciate what the patient is saying could result in them feeling that their concerns are not being taken seriously. As observed by the author in practice, effective listening is essential to understanding the patient's concerns.

Perception, interpretation, understanding

Relevant and well-prepared information is key to the patient's perception and interpretation of the messages relayed ( McClain, 2012 ). It is vital to aiding their understanding and to informing their personal choices and decisions. If a patient were to misinterpret the information received, this could likely result in a misunderstanding of the messages being relayed and, consequently, lead to an inability to make clear, informed decisions about their life choices ( McClain, 2012 ; Bramhall, 2014 ).

Fully informing the patient and treating them with honesty, respect and dignity

In making decisions about their life/care, a patient is entitled to all information relevant to their individual situation and needs (including those about the actual and potential risks of treatment and their likely disease trajectory) ( McClain, 2012 ). Information equals empowerment—making a decision based on full information about a prognosis, for example, gives people choices and enables them to put their affairs in order ( Evans, 2017 ). Being honest with a patient not only shows respect for them, their feelings and concerns, it also contributes to preserving the individual's dignity ( Ali, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ; Doyle, 2019 ). However, as observed in practice, a reluctance on the health professional's part to be totally open and honest with a patient can result in confusion and unnecessary emotional distress.

When reflecting on the efficacy of the communication being relayed, it is important for health professionals to acknowledge the challenges and consider how they may actually or potentially impact on the messages being relayed ( McClain, 2012 ; Ali, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ; Doyle, 2019 ).

Communication and the uro-oncology clinical nurse specialist

It is devastating for a patient to receive the news that they have cancer ( Bumb et al, 2017 ). Providing a patient with a cancer diagnosis—the ‘breaking of bad news’, defined as any information that adversely and seriously affects an individual's view of his or her future ( Schildmann et al 2005 )—is equally devastating for the professional ( Bumb et al, 2017 ; Hemming, 2017 ). It is thus imperative to ensure the appropriate support is forthcoming following receipt of bad news ( Evans, 2017 ).

Integral to the delivery of bad news is the cancer CNS, in this context, the UCNS, who is acknowledged to be in the ideal position to observe the delivery of bad news (usually by a senior doctor in the urology clinic), and its receipt by patients ( Macmillan Cancer Support, 2014 ; Hemming, 2017 ), and to offer appropriate support afterwards ( Evans, 2017 ). Support includes allocating appropriate time with the patient, and their family, after the clinic appointment to ensure they have understood the discussion regarding the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment options ( Evans, 2017 ; Hemming, 2017 ). In this instance, effective communication, as well as the time required, is usually tailored to each individual patient, allowing trust to be built ( Bumb et al, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ; Hemming, 2017 ).

In the performance of her role, the UCNS is fully aware of the importance placed on delivering bad news well. She has seen first hand how bad news given in a less than optimal manner can impact on the patient's emotions and their subsequent ability to deal with the results. Hence, her role in ensuring that the appropriate support is forthcoming following the delivery of bad news is imperative. It is important to understand that the delivery of bad news is a delicate task—one that necessitates sensitivity and an appreciation of the subsequent impact of the news on the individual concerned. It should also be acknowledged that while the receipt of bad news is, understandably, difficult for the patient, its delivery is also extremely challenging for the health professional ( Bumb et al, 2017 ).

Communicating bad news

The primary functions of effective communication in this instance are to enhance the patient's experience and to motivate them to take control of their situation ( McClain, 2012 ; Ali, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ; Doyle, 2019 ).

Telling a patient that they have a life-threatening illness such as cancer, or that their prognosis is poor and no further treatment is available to them, is a difficult and uncomfortable task for the health professional ( Bumb et al, 2017 ). It is a task that must be done well nonetheless ( Schildmann, 2005 ). Doing it well is reliant on a number of factors:

- Ensuring communicated information is sensitively delivered ( Hanratty et al 2012 ) to counter the ensuing shock following the patient's receipt of the bad news ( McClain, 2012 )

- Providing information that is clear, concise and tailored to meeting the individual's needs ( Hemming, 2017 )

- Acknowledging and respecting the patient's feelings, concerns and wishes ( Evans 2017 ).

This approach to care is important to empower patients to make the right choices and decisions regarding their life/care, and gives them the chance to ‘put their affairs in order’ ( McClain, 2012 ; Ali, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ).

Choices and decision-making

Case studies 1 and 2 show the importance of honesty, respect, listening and affording dignity to patients by health professionals, in this case senior doctors and the UCNS. The issue of choice and decision-making is highlighted. It is important to note that, while emphasis is placed on patients receiving all the pertinent information regarding their individual diagnosis and needs ( McClain 2012 ), despite receipt of this information, a patient may still be unable to make a definite decision regarding their care. A patient may even elect not to have any proposed treatment, a decision that some health professionals find difficult to accept, but one that must be respected nevertheless ( Ali, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ; Hemming, 2017 ).

Case study 1. Giving a poor prognosis and accepting the patient's decision

Jane Green, aged 48, received a devastating cancer diagnosis, with an extremely poor prognosis. It was evident that the news was not what she expected. She had been convinced that she had irritable bowel syndrome and, hence, a cancer diagnosis was quite a shock. Nevertheless, she had, surprisingly, raised a smile with the witty retort: ‘Cancer, you bastard—how dare you get me.’ Mrs Green had been married to her second husband for 3 years. Sadly, her first husband, with whom she had two daughters, aged 17 and 21, had died from a heart attack at the age of 52. His sudden death was hugely upsetting for his daughters; consequently, Mrs Green's relationship with her girls (as she lovingly referred to them) was extremely close. The legacy of having two parents who had died young was not one Mrs Green wished to pass on to her daughters. Her main concern, therefore, was to minimise the inevitable distress that would ensue, following her own imminent death.

In the relatively short time that Mrs Green had to digest the enormity and implications of her diagnosis, she had been adamant that she did not wish to have any life-prolonging interventions, particularly if they could not guarantee a reasonable extension of her life, and whose effects would impact on the time she had left. This decision was driven by previously having observed her mother-in-law's experience of cancer: its management with chemotherapy and the resultant effect on her body and her eventual, painful demise. Mrs Green's memory of this experience was still vivid, and had heightened her fears and anxieties, and reinforced her wish not to undergo similar treatment.

Mrs Green requested a full and honest discussion and explanation from the consultant urologist and the UCNS regarding the diagnosis and its implications. This included the estimated prognosis, treatment interventions and the relevant risks and benefits—specifically, their likely impact on her quality of life. In providing Mrs Green with this information, the consultant and the UCNS had ensured information was clear and concise, empathetic and sensitive to her needs ( Shipley, 2010 ; Hanratty, et al, 2012 ; Evans, 2017 ; Hemming, 2017 ) and, importantly, that her request for honesty was respected. Not disclosing the entire truth can ‘inadvertently create a false sense of hope for a cure and perceptions of a longer life expectancy’ ( Bumb et al, 2017:574 ). Being honest had empowered Mrs Green to come to terms with both the diagnosis and prognosis, to consider the options as well as the risks and benefits. She had a choice between quantity of life and quality of life. Mrs Green elected for quality of life and, accordingly, made decisions that she felt were in her own, and her family's, best interests.

Despite receiving pertinent information and sound advice on why a patient should agree to treatment intervention, they may still elect not to have any treatment ( Ali, 2017 ; Evans, 2017 ; Hemming, 2017 ). This decision, as observed by the UCNS in practice, is difficult for some health professionals to accept. In Mrs Green's case, accepting her decision not to have any treatment was extremely difficult for both the consultant and the UCNS. In an attempt to try to change Mrs Green's mind, the consultant asked the UCNS to speak to her. The UCNS was aware that the consultant's difficulty to accept the decision was compounded by Mrs Green's age (48) and a desire to give her more time. However, the UCNS had listened closely to Mrs Green's wishes and, in view of her disclosure regarding the experience of her mother-in-law's death, her first husband's untimely death, her fear of upsetting her daughters and her evident determination to keep control of her situation, the UCNS felt compelled to respect her decision.

Following the consultant's request, the UCNS spoke to Mrs Green but, on hearing what she had to say regarding her decision not to have more treatment, concluded that she had to respect Mrs Green's decision. She also clarified whether Mrs Green were willing to continue communication with her GP and ensured that the GP was fully updated regarding current events. Mrs Green had thanked the staff for all their support, but did not wish to continue follow-up with the service. The GP assured the UCNS that she would keep a close eye on Mrs Green and her family.

Case study 2. Giving an honest account of disease progression