VOTD: Turning Up The Heat In Spike Lee's 'Do The Right Thing'

It's been over 30 years since director Spike Lee released the provocative, insightful, and unfortunately prescient racially charged drama Do the Right Thing . The film follows a pizza delivery man named Mookie (played by Lee himself) as he makes the rounds in a Brooklyn neighborhood on one of the hottest days of the year. Tensions rise with the heat, leading to an explosive confrontation between whites, blacks and the law.

Sadly, Do the Right Thing is still relevant to this day as protesters clash with the police in the wake of the unlawful deaths of too many black citizens around the United States. As we watch history unfold, a video essay takes a closer look at one specific element of Do the Right Thing and how it's used to represent the increasing tension between white and black people in Brooklyn.

Do the Right Thing Video Essay

In Do the Right Thing , the sweltering summer heat is a key element in Spike Lee's depiction of escalating tensions between black and white people. Characters are dripping sweat as they walk through the streets of Brooklyn. Some of them try to cool off with the blast of fire hydrants and hoses. But no matter how hard they try, they heat can't be beat. And it's all leading to the fire that burns Sal's pizzeria to the ground in the middle of a riot caused by the main character Mookie.

This is just one of the many ways Spike Lee builds to the tragic conclusion of Do the Right Thing , and that climax is exactly what we're seeing unfold right now around the United States. It's frustrating that what Spike Lee has to say in this movie is still so relevant today. But we're glad a director like him continues to make movies like this, giving a voice to those who continue to be marginalized and oppressed.

Just in case you need some guidance on the full message behind Do the Right Thing , here you go:

- Screenwriting \e607

- Cinematography & Cameras \e605

- Directing \e606

- Editing & Post-Production \e602

- Documentary \e603

- Movies & TV \e60a

- Producing \e608

- Distribution & Marketing \e604

- Fundraising & Crowdfunding \e60f

- Festivals & Events \e611

- Sound & Music \e601

- Games & Transmedia \e60e

- Grants, Contests, & Awards \e60d

- Film School \e610

- Marketplace & Deals \e60b

- Off Topic \e609

- This Site \e600

Watch: What Spike Lee's 'Do the Right Thing' Can Teach You about Editing

True enough: there are few directors who mix cantankerousness and raw brilliance the way Spike Lee does. Also true: much of his genius is in the editing.

"Let the camera tell the story" might be a platitude that some directors aspire to but never reach, but Spike Lee reaches it in film after film. His seminal, angering, unsettling, and timeless film Do the Right Thing , about stormy and explosive race relations in the Brooklyn, NY summer heat, is no exception. This excellent video essay by Nick Coleman takes us through the movie a bit to show which editing tools Lee uses to tell his story, and how he's using them. Below are a few techniques that stood out to us.

Transitions

It is important to remember that the cinematography decides how quickly, how slowly, how smoothly, or how disjunctively a viewer moves through a film. Coleman uses the opening scene of the film as an example. We are treated first to the verbal fireworks ( That's the truth, Ruth! ) of Samuel L. Jackson's Mister Senor Love Daddy; his voice, and his general personal mood, will carry us into the narrative of the movie, along with the camera, which first takes us to the bed of Ossie Davis' (Da) Mayor, who will be a major character in the film. This sequence foreshadows the structure of the rest of the film, in which radio monologues (and music) wipe away one scene and set up another.

When Lee uses the radio as a throughline in his film, he is establishing continuity: he's creating a device by which viewers can recognize that they've moved from one part of a story to another, and also recognize that they're moving through a narrative, with specific plot points. He does this visually as well: when the camera moves away from Love Daddy's radio studio to the apartment of Ossie Davis' character, Coleman marvels, and rightfully so, at the smooth way in which Lee subliminally compares the two places and tells moviegoers that the two spaces he's filming will turn out to be very significant. Lee also uses what Coleman calls "a reestablishing shot," going from one character to another by backing away from one face and zooming in on the other. This could also be called "match on action," meaning that one movement the camera makes mimics the movement that proceeds it.

We should think about what the analytical ramifications of each transition might be.

Avoiding cheat cuts

Coleman swerves a little from the film at hand to address ways in which transition and continuity can be mishandled. He uses Michael Bay's Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen as an example: we should not, per Coleman, simply mimic a camera movement from one scene to another, for the "flow" of a film. Bay does this often, setting the stage for a general lack of articulation. We should instead think about what the analytical ramifications of each transition might be; as we weigh these things, a film can become more powerful. He does praise Bay's use of cross-cutting—in this case cuts from the earth to the sky with little warning—yet another technique, like close-ups or zoom-outs, to mainline the story, or its crucial elements, to readers' brains. If effectively used, as it is here, it has tremendous communicative potential.

Any thoughts about the editing in Do the Right Thing or Lee's other films? Let us know in the comments!

Check Out Sigma’s Slimmed Down 24-70mm F2.8 DG DN II Zoom Lens

This new sigma lens gets an upgrade with a slimmer, more economical, follow-up to the brand’s popular standard zoom for your full-frame mirrorless cameras..

The new version of the SIGMA 24-70mm F2.8 DG DN | Art also gets some helpful upgrades for enhanced optical performance, AF speed, and operability, as well as the aforementioned slimmed down-ness, which should make the new SIGMA 24-70mm F2.8 DG DN II | Art lens a popular, and very baggable, zoom for any of your full-frame mirrorless camera needs.

Let’s take a look at this updated new lens from Sigma and explore how it could be right for your video projects—as well as of course for any photo gigs that might require a solid hybrid lens.

Introducing the SIGMA 24-70mm F2.8 DG DN II | Art

Featuring an advancement in optical design, this new II version of the SIGMA 24-70mm F2.8 DG DN features a shortening of the total optical length, as well as a lens barrel that has been made slimmer by downsizing the zoom mechanisms in the lens.

The lens barrel in particular has been downsized by placing buttons and switches now directly on the lens barrel itself. This means that the weight of the lens has been reduced by approximately 10% compared to the previous version. This lightweight focus group with the high-thrust HLA should make autofocus significantly swifter than the original as well.

Sigma notes that aberrations have been highly corrected through advanced optical design which has been made possible by some further technologies in both design and manufacturing. More specifically, sagittal coma flare is heavily corrected to achieve MTF characteristics surpassing those of the highly acclaimed 24-70mm F2.8 DG DN | Art.

A Full-Frame Mirrorless Zoom

This new SIGMA 24-70mm F2.8 DG DN II | Art should be a great option for any videographers shooting full-frame with their mirrorless cameras and looking to have a solid and reliable fixed zoom that should fill in for any on-the-run or documentary-style projects.

Zoom lenses are getting better and better these days (as well as more affordable), so it’s no surprise to see this update from Sigma making this zoom even more functional and lightweight. The SIGMA 24-70mm F2.8 DG DN II | Art is also set to include a close-focusing distance of 6.7 inches (17cm) at the wide end at 1:2.7 magnification which should add to the overall versatility of the lens.

The II also includes a click/de-click and lockable aperture ring along with an additional AF-L button for vertical orientation still or video capture. Plus a zoom lock switch which will disengage when zooming is a nice touch as well.

Price and Availability

The SIGMA 24-70mm F2.8 DG DN II | Art is online and available to pre-order with an expected availability set for the end of May 2024. You can check out all of the specs and purchase options below.

- Full-Frame | f/2.8 to f/22

- Fast & Lightweight Wide-to-Tele Zoom

- HLA Autofocus

- 6.7" Minimum Focusing Distance

- Aperture Ring with Click & Lock Switches

- FLD, SLD & Aspherical Elements

- Nano Porous & Super Multilayer Coatings

- Dust & Splash Resistant

Sigma 24-70mm f/2.8 DG DN II Art Lens (Leica L)

Featuring improved rendering performance in a shorter and lighter body, Sigma 's flagship Leica L-mount 24-70mm f/2.8 DG DN II Art Lens deploys an advanced optical design for gains in sharpness, resolution, and portability.

static.bhphoto.com

What Are The Best Crime Movies of All Time?

The ending of 'challengers' explained, what are the best adventure movies of all time, what are the best fantasy movies of all time, translating 10 notes from executives that screenwriters hear all the time, check this vfx breakdown of the tv series 'fallout', what is the longest movie in the world, the 'joker' ending explained, what's the average structure of a superhero movie, an ode to marlin, the greatest dad in the seven seas.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Enduring Urgency of Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” at Thirty

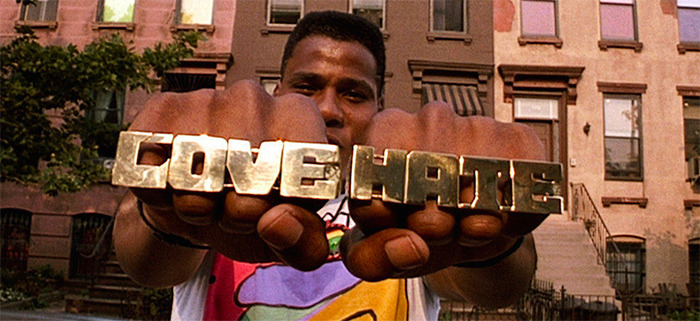

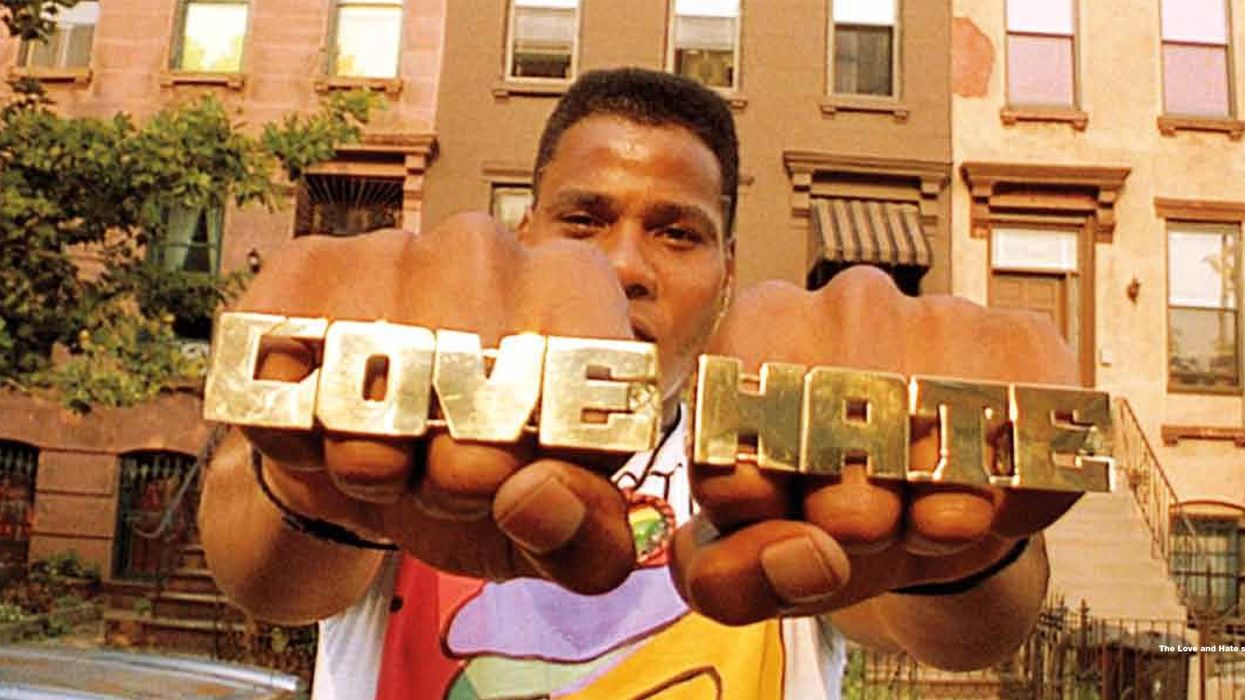

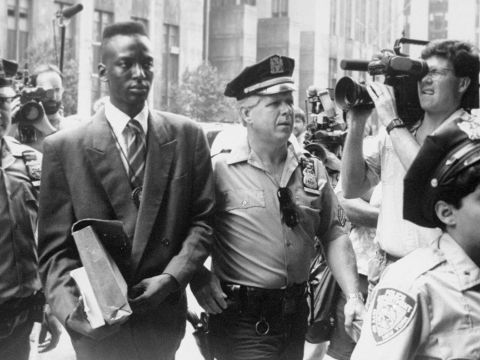

By Richard Brody

Spike Lee’s third feature, “Do the Right Thing,” returns to movie theatres this weekend in honor of the thirtieth anniversary of its release. Lee dedicated the movie, in the end credits, to the families of Eleanor Bumpurs, Michael Griffith, Arthur Miller, Edmund Perry, Yvonne Smallwood, and Michael Stewart—six black people, five of whom were killed by police officers, as the character Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) is, in the film’s climactic scene. (Griffith was killed by a white mob.). Three decades later, with police forces virtually militarized and with the judicial system largely granting officers impunity for killings committed on duty, the shock of the movie is that, even as many cultural and civic aspects that it represents have changed, its core drama—the killing of black Americans by police—continues unabated and largely unredressed.

“Do the Right Thing” isn’t a comprehensive representation of a cross-section of Bedford-Stuyvesant, the Brooklyn neighborhood where it is set, but a vision of private lives with a conspicuous public component—a sense of community and of history that’s a crucial aspect of identity. The movie’s individuals are boldly sketched with expressive exaggerations, not characters with deeply developed psychology but ones who bear the marks, the scars, and the emblems of history, and who also bear the pressure of the white gaze, the police gaze. No less than Lee’s script, his aesthetic offers a sharply original way of looking at the lives of black people—and of looking at life at large from a black person’s perspective. “Do the Right Thing” is grand, vital, and mournful; it is also, crucially, proud, a work not only of the agony of history—and of present-tense oppressions—but also of the historic cultural achievements of black Americans, and it takes its own place in the artistic history that it invokes.

The movie’s bright palette, its sense of contrasts of light and color, its distinctive and prominent addresses by characters looking in high-relief and fish-eye closeup at the viewer, its sense of bold declamation and assertive movement: all suggest a personal sense of style that builds on the cinematically disjunctive methods of the nineteen-sixties. They also evoke a cultural history—visual, dramatic, and tonal—informed by such artists as Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence, Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin and John Coltrane. Lee’s artistic collaborations are central to the movie’s rich sense of an artistic gathering, including the cinematography of Ernest Dickerson, the production design, by Wynn Thomas, and the costume design, by Ruth E. Carter . The score was composed by Lee’s father, Bill Lee, a bassist who has recorded with many major jazz musicians and appears on a wide range of albums, including Clifford Jordan’s classic “ Glass Bead Games .”

“Do the Right Thing” starts where Lee’s 1988 film “School Daze” ends—with a call to “Wake up”—but here it comes through by way of local media and in the context of art. It begins with one of the cinematic voices of the era—with Samuel L. Jackson, in the role of Mister Señor Love Daddy, the d.j. of a radio station operating from a storefront perch, where he’s on the air, watching the streets and orchestrating its moods with music, reporting back on what he sees and inflecting the moment with musings that connect the music to the community at large. In one spectacular monologue, Mister Señor Love Daddy recites his list of dozens of classical black musicians whose records he plays, beginning with Boogie Down Productions and ending with Mary Lou Williams.

The cultural clash at the center of “Do the Right Thing” is one that foreshadows major changes in the recent media landscape. The fast-talking young man called Buggin Out (Giancarlo Esposito) goes to Sal’s pizzeria for a slice, where Sal (Danny Aiello), the sympathetic but hotheaded owner, has photos of celebrities assembled into a “wall of fame.” Buggin Out notices that all of the photographs are of Italian-Americans (including Frank Sinatra, Liza Minnelli, and Joe DiMaggio) and asks why there aren’t any photos of black stars, given that the pizzeria is in a mainly black neighborhood. Sal’s answer—“Get your own place, you can do what you want to do”—doesn’t, of course, satisfy Buggin Out, who tries to organize a boycott of Sal’s. It doesn’t work, but Radio Raheem—who has already incurred Sal’s wrath by refusing to turn down his boom box, playing Public Enemy, in the pizzeria—ultimately decides to join him. (Raheem’s musical passion is also reverently devotional; his gesture is a crucial symbolic act of a black customer bringing his culture into a white-owned space.)

“School Daze” was more overtly tough-minded and more analytical in its portrait of divisions within the student body at a historically black university. In “Do the Right Thing,” Lee depicts a different sort of division, one that’s of deep political import but isn’t directly dramatized: the apparent ideological division between Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, which echoes bitterly through the film’s final tragedy. It’s exemplified in Lee’s placement of a quote from each at the end of the film. Dr. King’s quote begins, “Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral”; Malcolm’s concludes, “I don’t even call it violence when it’s self-defense, I call it intelligence.” The division is both presented and symbolically resolved in the photo of the two leaders together that the character Smiley (Roger Guenveur Smith) decorates and sells—and which Lee puts on the screen after the two quotes.

Lee, as Mookie, the deliveryman for Sal’s, plays a role that symbolized his own position in Hollywood at the time, as an employee of a white-run business and a mediator between it and the black community. When Buggin Out first challenges Sal about the photos on the wall, Mookie walks him out of the pizzeria and admonishes him for putting his job in jeopardy. But after the murder of Raheem, Mookie—at first standing alongside Sal and his sons (John Turturro and Richard Edson) in confronting the crowd in the wake of the killing—walks off, grabs a metal trash can, returns, and throws it through Sal’s window. That action sets Mookie’s neighbors to ransacking the pizzeria—culminating in Smiley lighting the match that torches it, as the elderly woman called Mother Sister (Ruby Dee), wise and bitter and rueful, calls out, “Burn it down.” (She’s one of only three prominently featured women in the movie; there’s another virtual movie lurking behind this one, which pays more attention to the public role of women in the community.)

With “Do the Right Thing,” Lee was letting Hollywood know that it, too, was on the wrong side of history—and was doing not just wrong but harm. Nonetheless, what’s astonishing about the response of Raheem’s friends and neighbors to his murder isn’t the trashing of Sal’s; it’s their restraint—the handful of police officers manage to leave, dragging away Raheem’s body and arresting Buggin Out, with little incident. The rage directed at Sal, for his obtuseness and for his words and acts of hatred, is in its own way symbolic—the blood is on the hands of the police officers, who’d likely go unpunished. It’s their gaze at peaceable black people that foreshadows the trouble to come; it’s their derogatory remarks about the neighborhood, in private conversation with Sal, that suggest the hatred and contempt motivating their official behavior.

In “Do the Right Thing,” Lee—in challenging the cultural segregation of Sal’s wall—challenges the very nature of a public space as private property. Here, too, Lee evokes the burden and the responsibility of history. The very theme of private property in public space was a crucial one in the civil-rights movement, when white segregationists attempted to maintain a ban on black people in their restaurants and stores by asserting that the facility was their private property. The notion was overturned in the definition of “public accommodations” in the Civil Rights Act of 1964; but those laws had nothing to do with another sort of public space, the media as a crucial part of civic life; though the concept is now widely recognized, the practice is still woefully inadequate.

“Do the Right Thing” was released the same year as “Driving Miss Daisy,” which won the Oscar for Best Picture; Lee’s film wasn’t nominated. Today, the industry mainstream, or whatever’s left of it, is at least superficially more diverse, and sometimes substantially so, as with “Creed” and “ Black Panther .” But some things haven’t changed: Lee’s “ BlacKkKlansman ,” which was a Best Picture nominee this year, lost out to “ Green Book ,” another regressive tale of interracial friendship.

History virtually pierces the screen in one image from “Do the Right Thing” that’s unbearable to watch—a closeup of Raheem’s feet, kicking and dangling off the ground, while he’s being choked by the police. It’s an image that evokes a hanging and suggests a lynching; to watch it now is to see it in the context not just of a long and horrific history of acts of racist violence against black Americans but also of the police brutality that, thirty years after the film’s release, continues. “Do the Right Thing” is, regrettably, not a work of history but a film set, in many ways, in the present tense.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Awol Erizku

By John Colapinto

Home / Essay Samples / Entertainment / Do The Right Thing / Gentrification and Class System in the Film “Do The Right Thing”

Gentrification and Class System in the Film "Do The Right Thing"

- Category: Entertainment , Government

- Topic: Do The Right Thing , Film Analysis , Gentrification

Pages: 4 (1959 words)

Views: 3028

- Downloads: -->

Introduction

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Republic Essays

Gentrification Essays

War on Drugs Essays

Voting Essays

Taxation Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->