Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

- The Vox guide to navigating the coronavirus crisis

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

- A syllabus for the end of the world

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

- What day is it today?

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

- Vox is starting a book club. Come read with us!

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Most Popular

The supreme court hands an embarrassing defeat to america’s trumpiest court, the supreme court rules that state officials can engage in a little corruption, as a treat, the frogs of puerto rico have a warning for us, web3 is the future, or a scam, or both, the whole time the boys has been making fun of trumpers the whole time, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

A new book tackles the splendor and squalor of reality TV

Julian Assange’s release is still a lose-lose for press freedom

Why do all the world’s best athletes do Subway commercials?

“Black girl tanning” is the summer’s most radical beauty trend

What this summer’s age-gap escapist fantasies are missing about romance and middle age

The most important Biden Cabinet member you don’t know

Facts on the Ground

The winners and losers of the Biden economy

Biden’s border record: Trump’s claims vs. reality

Why do Americans always think crime is going up?

4 reasons why the Biden-Trump debate could actually matter

Writing about COVID-19 in a college admission essay

by: Venkates Swaminathan | Updated: September 14, 2020

Print article

For students applying to college using the CommonApp, there are several different places where students and counselors can address the pandemic’s impact. The different sections have differing goals. You must understand how to use each section for its appropriate use.

The CommonApp COVID-19 question

First, the CommonApp this year has an additional question specifically about COVID-19 :

Community disruptions such as COVID-19 and natural disasters can have deep and long-lasting impacts. If you need it, this space is yours to describe those impacts. Colleges care about the effects on your health and well-being, safety, family circumstances, future plans, and education, including access to reliable technology and quiet study spaces. Please use this space to describe how these events have impacted you.

This question seeks to understand the adversity that students may have had to face due to the pandemic, the move to online education, or the shelter-in-place rules. You don’t have to answer this question if the impact on you wasn’t particularly severe. Some examples of things students should discuss include:

- The student or a family member had COVID-19 or suffered other illnesses due to confinement during the pandemic.

- The candidate had to deal with personal or family issues, such as abusive living situations or other safety concerns

- The student suffered from a lack of internet access and other online learning challenges.

- Students who dealt with problems registering for or taking standardized tests and AP exams.

Jeff Schiffman of the Tulane University admissions office has a blog about this section. He recommends students ask themselves several questions as they go about answering this section:

- Are my experiences different from others’?

- Are there noticeable changes on my transcript?

- Am I aware of my privilege?

- Am I specific? Am I explaining rather than complaining?

- Is this information being included elsewhere on my application?

If you do answer this section, be brief and to-the-point.

Counselor recommendations and school profiles

Second, counselors will, in their counselor forms and school profiles on the CommonApp, address how the school handled the pandemic and how it might have affected students, specifically as it relates to:

- Grading scales and policies

- Graduation requirements

- Instructional methods

- Schedules and course offerings

- Testing requirements

- Your academic calendar

- Other extenuating circumstances

Students don’t have to mention these matters in their application unless something unusual happened.

Writing about COVID-19 in your main essay

Write about your experiences during the pandemic in your main college essay if your experience is personal, relevant, and the most important thing to discuss in your college admission essay. That you had to stay home and study online isn’t sufficient, as millions of other students faced the same situation. But sometimes, it can be appropriate and helpful to write about something related to the pandemic in your essay. For example:

- One student developed a website for a local comic book store. The store might not have survived without the ability for people to order comic books online. The student had a long-standing relationship with the store, and it was an institution that created a community for students who otherwise felt left out.

- One student started a YouTube channel to help other students with academic subjects he was very familiar with and began tutoring others.

- Some students used their extra time that was the result of the stay-at-home orders to take online courses pursuing topics they are genuinely interested in or developing new interests, like a foreign language or music.

Experiences like this can be good topics for the CommonApp essay as long as they reflect something genuinely important about the student. For many students whose lives have been shaped by this pandemic, it can be a critical part of their college application.

Want more? Read 6 ways to improve a college essay , What the &%$! should I write about in my college essay , and Just how important is a college admissions essay? .

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How our schools are (and aren't) addressing race

The truth about homework in America

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Melinda French Gates Is Going It Alone

- How to Buy Groceries Without Breaking the Bank

- Lai Ching-te Is Standing His Ground

- What’s the Best Pillow Setup for Sleep?

- How Improv Comedy Can Help Resolve Conflicts

- 4 Signs Your Body Needs a Break

- The 15 Best Movies to Watch on a Plane

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Endurance got us through multiple lockdowns, and it’ll help us coming out of the pandemic too

Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Durham University

Disclosure statement

Felix Ringel does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Durham University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

The coronavirus, or rather the measurements taken against it, changed our perception of time . For many, the attempts to prevent the spread of the virus resulted in a feeling that time had come to a standstill.

When the pandemic first hit, this notion of stopped time was at the core of a widespread sense of crisis. For a while, many existed in survival mode, reacting to the demands of the day while unable to plan ahead. However, around the world, humans also began to deploy what in my work as a social anthropologist I call temporal agency – the ability to deliberately restructure, speed up or slow down the times we are living in.

Many of us learnt how to trick time in order to get through the new COVID-19 way of life. People restructured their daily lives by establishing new routines. Many had to navigate the differences between home and home office time, when both were spent in the same place. Some of us even learned how to tentatively plan ahead in a reality where the future was uncertain.

Many lockdowns (at least in the UK) later, I’m still impressed by the creative responses to the pandemic, particularly the many ways in which families and friends learned to share time at a distance. However, the one feature I particularly believe we should carry into the post-pandemic future is not that COVID creativity, but perseverance itself.

Endurance, maintenance and tenacity – the ingredients that make up perseverance – are under-appreciated even in times without crisis. However, they kept us going when life was hardest. Humanity surprised itself by quickly adapting to the new pandemic normal, but what counted more was the perseverance we deployed for more than a year without giving up. Creating a sustainable post-pandemic future will depend on it, too.

Missed opportunities

The pandemic taught us to appreciate, and even celebrate perseverance, not least the continuous daily work of all the heroic frontline workers (whose everyday work we’d taken for granted for too long). It also provided us with a chance to reconsider what’s important in our lives and how we want to organise our societies in the future. Many of us were made aware of what counts and what was missed the most.

Prominent amongst those things are the social relations that make us who we are -– with family members, friends, neighbours and colleagues, even those we had all those unnecessary fights with during lockdown.

Read more: Coronavirus: how the pandemic has changed our perception of time

In the post-pandemic future, we should never again take them for granted, nor all the hugs , kisses and handshakes. We avoid doing that by appreciating the work that goes into maintaining these social relationships.

Apart from time for family and friends, we also yearned for other times -– for travel and leisure, for example. We’d taken for granted the distinction between work and leisure, office and home time, and we’ll have to take time again to renegotiate these distinctions. Whatever we come up with in the end, this new work-life balance will also have to stand the test of time – whether it can endure in the future and we in it.

Endurance and exhaustion

During the pandemic, many people had to come up with new ideas and change their behaviour. But once that change had happened, we were forced to maintain and endure our response to the pandemic.

The daily exercises, weekly Zoom calls with relatives or prolonged homeschooling efforts were all examples of endurance. In many places, perseverance shaped the latter part of the pandemic – it was all about making it through a few more dark winter days and resisting general exhaustion and lockdown fatigue.

Endurance is important to society in general. In a recent paper, I looked into why this matters in the context of urban decline in postindustrial cities .

As cities change, their inhabitants are forced to adapt their behaviour to new social, economic and political circumstances. Through this change, the fight to keep something you love alive requires endurance. Sustaining a social club that struggles to find new members or preserving your local community centre from closure entails plenty of perseverance. Maintaining part of your urban infrastructure that suffers from funding cuts – your youth club or local park – is a revolutionary act, because it withstands the change others intended for it.

This work of maintenance and repair is at the core of our societies . It might look less interesting than attempts at making a difference, but without it everything around us would collapse.

The end of this pandemic will not be a sharp cut. It will be gradual and, as humanity will have to pace itself, there will be more need for endurance. In the best case, the experiences of the pandemic will help us determine what this future should look like.

Although the pandemic will at some point be over, there are enough crises yet that demand our attention: economic, social, ecological and political ones as well as potential future pandemics. The same sense of endurance, sustainability and perseverance will have to characterise our responses to those, too.

It is not enough to wait for a shortcut out of climate change or a cure-all for economic decline. A truly sustainable solution to these crises will have to be maintained in new everyday lives and routines. It will have to work with a different understanding of what human agency is all about.

Like during the pandemic, we not only have to establish new ideas, but make them work in the long run.

- Anthropology

- Coronavirus insights

PhD Scholarship

Clinical Psychologist Counsellor

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Social Media Producer

- Choose Country

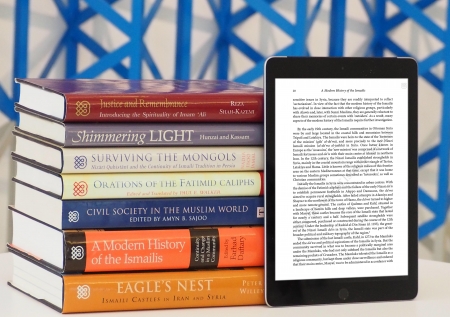

- Ismaili Community

- Ismaili Imamat

Related Websites

- Architecture

- In the Media

- Photo Gallery

- Video Gallery

- Social Media

- Around the World

- Jubilee Programmes

- Our Stories

- Our Culture

Pandemic perseverance: Pursuing your dreams during Covid-19

I always saw the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) as a daunting exam; nevertheless, the fact that so many students would be taking it with me physically gave me some sense of moral support, even if that support was coming from strangers.

I never expected studying for this exam to take such a different turn with the pandemic hitting during my first semester of studying; suddenly, I no longer had the presence of random students trying their best at a beast of an exam, the library corner that I had claimed specifically for MCAT studying, or the friends that I needed to tell me that I could do whatever I set my mind to. Yes, the pandemic shifted the way I had planned to study for this test, but not for a moment did I think that a virus, invisible to the naked eye, could take my focus away from the end goal. In retrospect, our dreams may often take a different path than we initially planned, but we can still arrive where we want.

As a college student, school is so much more than the exams I take and the grades I work towards; it's about people, the walk from biology class to the Activity Center, the spontaneous conversations with professors, and above all, the joy it gives to simply be a recipient of a good education. Even during exams, amongst all the contagious fret and worry that seemed to run through the lecture hall, knowing that friends and strangers were around me, taking the test with me in proximity, had a sort of calming relief as I began my test.

Since the beginning of the Fall semester, I have been studying for the MCAT, a medical school admissions exam. Like many others taking entrance exams, wearing a mask for seven hours was not quite the experience I had imagined. I knew that studying for this test was going to be challenging due to the sheer amount of information that had to be learned, but I hadn’t taken into account the challenge that Covid-19 would bring; I hadn’t fully appreciated what it meant to sit in the library with my friends, cramming for a class. Although I knew my friends across state borders were studying for the exam as well, I couldn’t help but feel a certain demotivation that came along with not seeing them and feeling their energy as we struggled and persevered as a group.

Although my test is now complete, it reminded me of what it means to be in the presence of those who make you feel like while every day may be a struggle, we are always victorious at the end. Covid has been hard for many; as a student, I thought that the convenience of simply having my bedroom as my office would make life so much easier; while that is true to some degree, for me, people matter; the conversations on campus matter; spontaneous moments with professors matter and Covid has somewhat altered that reality, replacing it with a new one.

As humans, we have always adjusted and evolved; in fact, the current pandemic is a testament to that very idea. While every day seems to be prey to the routine of yesterday, it is in fact our ability as a species to continue dreaming, pursuing, and reaching that makes us such a unique community.

Too often during the pandemic I have heard many talk about returning to “normalcy” or going back to the “way things were.” While it may seem like the life we have post-Covid will be a return of our old lives and habits, I believe that we are actually heading into a fresh start, a chance to step into a new way of living.

We all learn something every day and that knowledge makes each day quite different than the previous one; perhaps our very evolution is being put to the test during this pandemic. Can we rise from a strange, unnatural event that has shifted our thinking, our mindset, and our emotions? Can we truly dream during a time when the very institutions that facilitate learning have been diminished to a mere screen? I think we can; as a Jamat, as a community, as a global village, I think we will grow from this time and rise to a better version of ourselves that has learned, that has evolved, that has changed for the better. I know we will. People will always be a part of our lives, because we need each other to survive, to innovate, to create.

This one moment in time may have slightly changed how we interact and how much, but one thing that will remain constant as we evolve is our everlasting need for each other.

Related Articles

LIF members meet in Lisbon

Eid-e Ghadir

Important Links

The Ismaili Imamat

- Aga Khan Development Network

The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Subscribe to the.ismaili newsletter

Stay updated with latest from the.ismaili

- His Highness the Aga Khan

- Imamat Timeline

- What's New

- Imamat News

- Institutional News

- Community News

- Photo Galleries

- Films and Videos

Ismaili Centres

- Ismaili Centre Home

- Ismaili Center Houston

- Ismaili Centre Dubai

- Ismaili Centre Dushanbe

- Ismaili Centre Lisbon

- Ismaili Centre London

- Ismaili Centre Toronto

- Ismaili Centre Vancouver

Institutions and Programmes

- Conciliation and Arbitration Board

- Global Encounters

- Time and Knowledge Nazrana

- Institute of Ismaili Studies

- Aga Khan Museum

- Global Centre for Pluralism

- Aga Khan University

- University of Central Asia

- Aga Khan Hospitals

- Aga Khan Academies

- Aga Khan Schools

- Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture

- PRIVACY POLICY

- Terms & Conditions

©2024 Islamic Publications Limited. This is the official website of the Ismaili Muslim Community

Seven short essays about life during the pandemic

The boston book festival's at home community writing project invites area residents to describe their experiences during this unprecedented time..

My alarm sounds at 8:15 a.m. I open my eyes and take a deep breath. I wiggle my toes and move my legs. I do this religiously every morning. Today, marks day 74 of staying at home.

My mornings are filled with reading biblical scripture, meditation, breathing in the scents of a hanging eucalyptus branch in the shower, and making tea before I log into my computer to work. After an hour-and-a-half Zoom meeting, I decided to take a long walk to the post office and grab a fresh bouquet of burnt orange ranunculus flowers. I embrace the warm sun beaming on my face. I feel joy. I feel at peace.

I enter my apartment and excessively wash my hands and face. I pour a glass of iced kombucha. I sit at my table and look at the text message on my phone. My coworker writes that she is thinking of me during this difficult time. She must be referring to the Amy Cooper incident. I learn shortly that she is not.

Advertisement

I Google Minneapolis and see his name: George Floyd. And just like that a simple and beautiful day transitions into a day of sorrow.

Nakia Hill, Boston

It was a wobbly, yet solemn little procession: three masked mourners and a canine. Beginning in Kenmore Square, at David and Sue Horner’s condo, it proceeded up Commonwealth Avenue Mall.

S. Sue Horner died on Good Friday, April 10, in the Year of the Virus. Sue did not die of the virus but her parting was hemmed by it: no gatherings to mark the passing of this splendid human being.

David devised a send-off nevertheless. On April 23rd, accompanied by his daughter and son-in-law, he set out for Old South Church. David led, bearing the urn. His daughter came next, holding her phone aloft, speaker on, through which her brother in Illinois played the bagpipes for the length of the procession, its soaring thrum infusing the Mall. Her husband came last with Melon, their golden retriever.

I unlocked the empty church and led the procession into the columbarium. David drew the urn from its velvet cover, revealing a golden vessel inset with incandescent tiles. We lifted the urn into the niche, prayed, recited Psalm 23, and shared some words.

It was far too small for the luminous “Dr. Sue”, but what we could manage in the Year of the Virus.

Nancy S. Taylor, Boston

On April 26, 2020, our household was a bustling home for four people. Our two sons, ages 18 and 22, have a lot of energy. We are among the lucky ones. I can work remotely. Our food and shelter are not at risk.

As I write this a week later, it is much quieter here.

On April 27, our older son, an EMT, transported a COVID-19 patient to the ER. He left home to protect my delicate health and became ill with the virus a week later.

On April 29, my husband’s 95-year-old father had a stroke. My husband left immediately to be with his 90-year-old mother near New York City and is now preparing for his father’s discharge from the hospital. Rehab people will come to the house; going to a facility would be too dangerous.

My husband just called me to describe today’s hospital visit. The doctors had warned that although his father had regained the ability to speak, he could only repeat what was said to him.

“It’s me,” said my husband.

“It’s me,” said my father-in-law.

“I love you,” said my husband.

“I love you,” said my father-in-law.

“Sooooooooo much,” said my father-in-law.

Lucia Thompson, Wayland

Would racism exist if we were blind?

I felt his eyes bore into me as I walked through the grocery store. At first, I thought nothing of it. With the angst in the air attributable to COVID, I understood the anxiety-provoking nature of feeling as though your 6-foot bubble had burst. So, I ignored him and maintained my distance. But he persisted, glaring at my face, squinting to see who I was underneath the mask. This time I looked back, when he yelled, in my mother tongue, for me to go back to my country.

In shock, I just laughed. How could he tell what I was under my mask? Or see anything through the sunglasses he was wearing inside? It baffled me. I laughed at the irony that he would use my own language against me, that he knew enough to guess where I was from in some version of culturally competent racism. I laughed because dealing with the truth behind that comment generated a sadness in me that was too much to handle. If not now, then when will we be together?

So I ask again, would racism exist if we were blind?

Faizah Shareef, Boston

My Family is “Out” There

But I am “in” here. Life is different now “in” Assisted Living since the deadly COVID-19 arrived. Now the staff, employees, and all 100 residents have our temperatures taken daily. Everyone else, including my family, is “out” there. People like the hairdresser are really missed — with long straight hair and masks, we don’t even recognize ourselves.

Since mid-March we are in quarantine “in” our rooms with meals served. Activities are practically non-existent. We can sit on the back patio 6 feet apart, wearing masks, do exercises there, chat, and walk nearby. Nothing inside. Hopefully June will improve.

My family is “out” there — somewhere! Most are working from home (or Montana). Hopefully an August wedding will happen, but unfortunately, I may still be “in” here.

From my window I wave to my son “out” there. Recently, when my daughter visited, I opened the window “in” my second-floor room and could see and hear her perfectly “out” there. Next time she will bring a chair so we can have an “in” and “out” conversation all day, or until we run out of words.

Barbara Anderson, Raynham

My boyfriend Marcial lives in Boston, and I live in New York City. We had been doing the long-distance thing pretty successfully until coronavirus hit. In mid-March, I was furloughed from my temp job, Marcial began working remotely, and New York started shutting down. I went to Boston to stay with Marcial.

We are opposites in many ways, but we share a love of food. The kitchen has been the center of quarantine life —and also quarantine problems.

Marcial and I have gone from eating out and cooking/grocery shopping for each other during our periodic visits to cooking/grocery shopping with each other all the time. We’ve argued over things like the proper way to make rice and what greens to buy for salad. Our habits are deeply rooted in our upbringing and individual cultures (Filipino immigrant and American-born Chinese, hence the strong rice opinions).

On top of the mundane issues, we’ve also dealt with a flooded kitchen (resulting in cockroaches) and a mandoline accident leading to an ER visit. Marcial and I have spent quarantine navigating how to handle the unexpected and how to integrate our lifestyles. We’ve been eating well along the way.

Melissa Lee, Waltham

It’s 3 a.m. and my dog Rikki just gave me a worried look. Up again?

“I can’t sleep,” I say. I flick the light, pick up “Non-Zero Probabilities.” But the words lay pinned to the page like swatted flies. I watch new “Killing Eve” episodes, play old Nathaniel Rateliff and The Night Sweats songs. Still night.

We are — what? — 12 agitated weeks into lockdown, and now this. The thing that got me was Chauvin’s sunglasses. Perched nonchalantly on his head, undisturbed, as if he were at a backyard BBQ. Or anywhere other than kneeling on George Floyd’s neck, on his life. And Floyd was a father, as we all now know, having seen his daughter Gianna on Stephen Jackson’s shoulders saying “Daddy changed the world.”

Precious child. I pray, safeguard her.

Rikki has her own bed. But she won’t leave me. A Goddess of Protection. She does that thing dogs do, hovers increasingly closely the more agitated I get. “I’m losing it,” I say. I know. And like those weighted gravity blankets meant to encourage sleep, she drapes her 70 pounds over me, covering my restless heart with safety.

As if daybreak, or a prayer, could bring peace today.

Kirstan Barnett, Watertown

Until June 30, send your essay (200 words or less) about life during COVID-19 via bostonbookfest.org . Some essays will be published on the festival’s blog and some will appear in The Boston Globe.

One Student's Perspective on Life During a Pandemic

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Ethics Resources

- Ethics Spotlight

- COVID-19: Ethics, Health and Moving Forward

The pandemic and resulting shelter-in-place restrictions are affecting everyone in different ways. Tiana Nguyen, shares both the pros and cons of her experience as a student at Santa Clara University.

person sitting at table with open laptop, notebook and pen

Tiana Nguyen ‘21 is a Hackworth Fellow at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. She is majoring in Computer Science, and is the vice president of Santa Clara University’s Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) chapter .

The world has slowed down, but stress has begun to ramp up.

In the beginning of quarantine, as the world slowed down, I could finally take some time to relax, watch some shows, learn to be a better cook and baker, and be more active in my extracurriculars. I have a lot of things to be thankful for. I especially appreciate that I’m able to live in a comfortable house and have gotten the opportunity to spend more time with my family. This has actually been the first time in years in which we’re all able to even eat meals together every single day. Even when my brother and I were young, my parents would be at work and sometimes come home late, so we didn’t always eat meals together. In the beginning of the quarantine I remember my family talking about how nice it was to finally have meals together, and my brother joking, “it only took a pandemic to bring us all together,” which I laughed about at the time (but it’s the truth).

Soon enough, we’ll all be back to going to different places and we’ll be separated once again. So I’m thankful for my living situation right now. As for my friends, even though we’re apart, I do still feel like I can be in touch with them through video chat—maybe sometimes even more in touch than before. I think a lot of people just have a little more time for others right now.

Although there are still a lot of things to be thankful for, stress has slowly taken over, and work has been overwhelming. I’ve always been a person who usually enjoys going to classes, taking on more work than I have to, and being active in general. But lately I’ve felt swamped with the amount of work given, to the point that my days have blurred into online assignments, Zoom classes, and countless meetings, with a touch of baking sweets and aimless searching on Youtube.

The pass/no pass option for classes continues to stare at me, but I look past it every time to use this quarter as an opportunity to boost my grades. I've tried to make sense of this type of overwhelming feeling that I’ve never really felt before. Is it because I’m working harder and putting in more effort into my schoolwork with all the spare time I now have? Is it because I’m not having as much interaction with other people as I do at school? Or is it because my classes this quarter are just supposed to be this much harder? I honestly don’t know; it might not even be any of those. What I do know though, is that I have to continue work and push through this feeling.

This quarter I have two synchronous and two asynchronous classes, which each have pros and cons. Originally, I thought I wanted all my classes to be synchronous, since that everyday interaction with my professor and classmates is valuable to me. However, as I experienced these asynchronous classes, I’ve realized that it can be nice to watch a lecture on my own time because it even allows me to pause the video to give me extra time for taking notes. This has made me pay more attention during lectures and take note of small details that I might have missed otherwise. Furthermore, I do realize that synchronous classes can also be a burden for those abroad who have to wake up in the middle of the night just to attend a class. I feel that it’s especially unfortunate when professors want students to attend but don’t make attendance mandatory for this reason; I find that most abroad students attend anyway, driven by the worry they’ll be missing out on something.

I do still find synchronous classes amazing though, especially for discussion-based courses. I feel in touch with other students from my classes whom I wouldn’t otherwise talk to or regularly reach out to. Since Santa Clara University is a small school, it is especially easy to interact with one another during classes on Zoom, and I even sometimes find it less intimidating to participate during class through Zoom than in person. I’m honestly not the type to participate in class, but this quarter I found myself participating in some classes more than usual. The breakout rooms also create more interaction, since we’re assigned to random classmates, instead of whomever we’re sitting closest to in an in-person class—though I admit breakout rooms can sometimes be awkward.

Something that I find beneficial in both synchronous and asynchronous classes is that professors post a lecture recording that I can always refer to whenever I want. I found this especially helpful when I studied for my midterms this quarter; it’s nice to have a recording to look back upon in case I missed something during a lecture.

Overall, life during these times is substantially different from anything most of us have ever experienced, and at times it can be extremely overwhelming and stressful—especially in terms of school for me. Online classes don’t provide the same environment and interactions as in-person classes and are by far not as enjoyable. But at the end of the day, I know that in every circumstance there is always something to be thankful for, and I’m appreciative for my situation right now. While the world has slowed down and my stress has ramped up, I’m slowly beginning to adjust to it.

Stories of hope, resilience and inspiration during the coronavirus pandemic

Individuals from around the world share their personal stories of hope, resilience, and inspiration during this time.

Bisma Farooq Sheikh India

Coronavirus Lockdown: Boon or Bane “Treat lock down as Boon rather than Bane. This is a golden opportunity to have a great time with family… It is the best time for dual earner couples to spend time with each other. It is an opportunity for kids to have a great time with parents. It is an opportunity to learn new skills. It is an opportunity to enjoy life. Give time to your hobby like gardening, writing, drawing. It is an opportunity to cherish with friends online, it’s time to enjoy more sleep… Life has too much to offer provided we have the right mindset.”

Aimee Karam Lebanon

“It is not about the virus per se, nor about the stress of being confined at home. It is about a large part of the Lebanese people, who due to the current challenging economic crisis and the confinement decreed in the face of the virus adversity, is suffering from fear, loneliness, deep poverty and hunger in times of a deadly pandemic. Living in Lebanon nowadays is an act of surviving adversities in a country of a panoply of human paradoxes, simultaneously inhaling and exhaling tragedies, irreverence but also magnificent and heroic efforts of solidarity. A sense of fundamental anchor is being created where safety and bonding keep the miracle of life alive. One million dollars in one hour, broke the record on the first day of a fundraising campaign with explosions of happiness. Three associations, sharing the values of transparency, political independence, integrity and non-discrimination, joined forces to organize this fundraising, soliciting the Lebanese diaspora in the United States to join hands to help the most disadvantaged. The sum raised has covered boxes of food for 50,000 families, around 175,000 people for one month. People, with an incredible devotion, are distributing boxes of food with love and compassion towards their compatriots with one uniting message: Food is a human right, no one should be hungry!”

Lina Fernanda Vélez Botero Colombia

“In Valle del Cauca, Colombia, psychology leaders who represent the partnership built between the Colombian Association of Psychologists (COLPSIC) and various universities in the region have made it possible for mental health attention to be a priority for citizens and healthcare workers. This was developed within the department's mental health committee against Covid-19 and in governmental strategies available for the community. Through the creation of a platform called calivallecorona.com , the Valle and the Paciific Region community not only have access to care services for their physical health with medical personnel, but also, through the module called Emotional Well-Being , they can access free tele-counseling services to promote emotional well-being. It seeks to offer a model of multidisciplinary care for the community during this health emergency, with a focus on mental health prevention and promotion, also integrating the early detection of complications. For psychology, this is an action of great social impact that responds to current global challenges such as making visible the needs of mental health in the face of the emergency, interdisciplinary work for community welfare in a dialogue of knowledge with other professions such as engineers, psychiatrists and doctors, and achieving an inter-institutional alliance with the public and governmental sectors of Colombia.”

Laura Neulat France

“When Pedro found out he was being transferred to a Covid-19 ward, he was overcome with fear. A young physiotherapist specialized in orthopedics; he enjoyed working at one of Paris’s largest hospitals. Now he was going to spend his days around Covid-19 patients, who needed breathing therapy after leaving the intensive care unit – holding them in his arms, keeping his face near theirs. In our weekly tele-session, a few days before he was due to start his new role; I encouraged him to focus on feelings of safety. I suggested he carry an index card with a thought that made him feel strong, such as The FORCE is with me! I further suggested he focus mentally on that mantra on his way to the hospital; also knowing he had it in his pocket, just in case. Pedro had learned to use mindfulness to regulate emotions and we said he was going to put on his protective equipment in mindfulness, focusing on every piece of equipment and telling himself, This cap keeps me safe , etc. Once all geared up, he would tell himself, I am safe . I feel at times we as psychologists must be able to afford flexibility with our boundaries. So parallel to the sessions, every evening I recorded a 10 second video of my street at 8:00 p.m., when we open windows for the applause to thank health workers, and I sent them to him with two words: Thank you . Pedro texted me Sunday evening: Thank you, I am now ready . At the end of his first day in his new role he texted me: I have just finished my day, it all went all right, I felt strong .”

L. R. Madhujan India

“For people who feel safe at home, the isolation period is the best time to plan for the future. Try to be creative. We can survive all this. We have the strength. Soon, new mornings will come. The flowers will bloom and the streets will become active. The sun will shine more brightly. The aroma is fragrant.”

Liza M. Meléndez-Samó Puerto Rico

“As a university professor, the challenges of moving to virtual classes were not far behind. Even though I had just received a certification in virtual distance education. During this semester I found myself teaching a course on contemporary models of psychotherapy. Two weeks after the quarantine began, the unit I would teach on would be expressive therapies. I was thinking how to translate a dynamic application in the classroom into a virtual activity. At that moment it occurred to me, rather than giving a class, my students needed that space to process the new reality of COVID-19. So, not only did I give a virtual class on expressive therapies, I converted the space into an art therapy live application as well. The goal was that each of them from their homes could express themselves from their homes through four drawings, allowing creativity to flow and emphasizing the process, not the result. By discussing the theories, they analyzed their arts meaning, which in turn promoted laughter and participation among them. Also, the group discussions allowed them to find new meanings, named their concerns and see the positive side of it all. But more importantly allowed them a space to express and reflect on their feelings about everything we are experiencing and how we can count on this tool not only for themselves, but also for their professional work. Curiously, there were repeated drawings, symbols and shapes between them (i.e. spirals). At the end, they told me that this had been the best class they have had online.”

Usha Kiran Subba Nepal

Patience is a Virtue “Once upon a time, there was a very beautiful island surrounded by flowers gardens, streams, and ponds. It was perceived as heaven on the earth peaceful and serine. All birds and animals lived together happily for many years. As the times passed they felt the environment has changed, there were no rains in rainy seasons, the pond was drying, and the garden was dried up and faded. The island has suffered severely from drought. Animals and birds decided to migrate to a new place for livelihood. In the same place, there were a couple of geese, and a tortoise lived on the pond. They were best friends. The geese decided to migrate from there. The tortoise also wanted to move with them, but she was unable to fly. So she pleaded to geese to rescue her from the problem.

It was a great challenge for the geese regarding how it was possible. But they were very kind and did not like to lose their friend so they got an idea to take her together. They brought a long stick with their beaks and asked the tortoise to hold the stick with her mouth tightly. They warned her not to open her mouth at any cost. They flew together and when they reached a new city, city dwellers were wandering to see such an amazing scene in the sky. They called up other people loudly to behold it and enjoy the moment. The tortoise and geese heard a loud noise. The tortoise was much disturbed by the noise and crowd and she opened her mouth to control it. As soon as she did, she had fallen to the ground and passed away.

We conclude the story in Nepali as saying: Bhanne lai Phool ko mala (Storyteller gets flower garland), Sunne lai sun ko mala, (story listener gets gold garland), It will remain in the mind of people forever.”

Oi-ling SIU Hong Kong

“The COVID-19 outbreak has caused immense stress and undermined psychological well-being. Many have been concerned not only about being infected, but also about shortages of hygiene products and food. Wofoo Joseph Lee Consulting and Counselling Psychology Research Centre (WJLCCPRC) at Lingnan University, Hong Kong, promptly launched a press release in February 2020 to advise Hong Kong citizens on how to be resilient to mitigate the psychological impacts of the epidemic. The press release was covered by three local presses and two social media platforms. The online campaign alone reached 146,000 online viewers.”

Zarina Giannone British Columbia

“My story of hope, connection, and inspiration has emerged through volunteerism and giving back to the community that works tirelessly to ensure my safety and wellness. I have coped with the pandemic by working with the British Columbia (B.C.) Psychological Association and the University of British Columbia-Okanagan to spearhead the development of opportunities for doctoral psychology students and trainees to become involved in supporting the recently announced Emergency Telepsychology Services Program, a novel program run by psychologists that provides free telepsychology services to health care workers at the front line of the COVID-19 pandemic in B.C. Some of the ideas that have been raised as potential options for student involvement include developing written clinical content for distribution among health care workers (e.g., coping during COVID-19), offering peer support with other health care students/trainees (e.g., nurses, medical residents), and providing mental health first aid. I have found that getting involved to help alleviate the psychological burden that has arisen due to the COVID-19 pandemic has been an effective way of coping and staying connected. I know that I am not the only one because we have had over 40 students sign up to volunteer in less than 48 hours! This is truly quite remarkable because there are probably less than 100 students enrolled in professional psychology doctoral programs in B.C.!”

Contact International Affairs

You may also like.

Voices of the Global Community

Student resilience during times of crisis.

Anne Liotine & Michael Magee , Harper College

With dueling crises happening in the nation, we entered a period of social unrest related to festering racial inequalities in American society. Protests, rioting, and looting ensued after the Memorial Day death of George Floyd. This action led to a third crisis that has engulfed the nation. With many campuses prepared to welcome students back to campus soon, protests and hate crimes may become another major issue for students to overcome. FBI data has shown an uptick in hate crimes on campuses (Bauman, 2018), and this was prior to the latest string of racial incidents.

Twenty-first century students have had to overcome many tragic events. The terrorist attacks of September 11 th , Hurricane Katrina, economic collapse in 2008, and multiple natural disasters since then. Students have lost everything due to natural disasters and relied on strangers around the country for support (Magee et al., 2007). Many needed the support of counseling services on their new campuses to enhance and develop their ability to persevere through a tough situation (Fernando & Hebert, 2011). During challenging times where resilience is critical to student success, advisors must be prepared to empower and support students to persist.

Determination and resilience, particularly through times of adversity, to reach a desired outcome can be the hallmark of a successful student. Angela Duckworth and her team of researchers define the term grit as “perseverance and passion for long term goals” (Duckworth et al., 2007, p. 1087). Choosing to attend college is not a small decision, especially for first generation students. As college expenses continue to rise, more and more is asked of our students: studying 2–3 hours outside of their courses, working a full-time/part-time job, and taking care of at-home responsibilities. For a college student to be successful, they not only need to have the passion to complete their courses, but they also need to keep in mind their long-term goal, whether that is earning a certificate, associate’s degree, or continuing their education further. In the Duckworth et al. (2007) study, the researchers wanted to understand why some college students are more successful than others. They found that grit increases with age and students with a higher grit score have lower SAT scores but higher GPAs. Resilience is one component of grit that explains some of these phenomena as well as overcoming adversity in the face of challenges (Perkins-Gough, 2013). Being able to pick yourself up from a failure and keep moving forward exemplifies the definition of grit in that a student who may have a lot going on outside of school, will work harder in their courses to understand material receiving a passing grade in a class.

Another noteworthy researcher is Carol Dweck, who studies growth mindset. Her “research has shown that the view you adopt for yourself profoundly affects the way you lead your life. It can determine whether you become the person you want to be and whether you accomplish the things you value” (Dweck, 2016, p. 6). What Dweck (2016) insinuates is that when you have a growth mindset you believe that you can change innate qualities within yourself, whether that is your personality, intelligence artistic or athletic ability. Failure can help drive you towards your next success because you learn and grow from mistakes. It aids you in coming up with creative solutions to move forward and taking action to confront the problems, rather than believing you cannot come back from it (Dweck 2016).

As advisors, we must encourage and promote grit and growth to encourage resilience and persistence. To do this, advisors first need to look inward and determine how we overcame setbacks while working from home. How have we handled a mistake? Do we work towards a creative solution or dwell on the fact that we have failed ourselves and/or our students? Duckworth has a free online assessment that will help determine our personal grit score (Duckworth, 2020). Determining where we are can help us move forward, and the same goes for our students. We can share this resource during our phone/video appointments to then discuss how to persevere through a challenging course or semester.

When it comes to our student’s long-term goals, we can help them break down their habits. For example, if a student wants to earn all As and Bs this semester, what does that look like? What kind of behaviors can advisors encourage they follow through with when they encounter a paper, test or discussion post that has brought down their grade? As the advisor, it will be important to encourage tutoring, utilizing professor’s office hours, creating study groups with peers, and having enough time to prepare. The objective is to help students think outside the box, as well as how to overcome a setback when they should face it.

Online learning can be challenging for students. This can be even further multiplied by students who may not have a laptop or consistent internet at home. Advisors may hear comments from students like, “I just can’t teach myself this material” or “I am not motivated to do the homework.” Part of building resilience and growing their mindset can be breaking down their goals into simpler tasks. If they want to get all As and Bs in their classes this semester, how far in advance are they studying for their tests? How much time are they devoting to their readings? Papers? Have students create a schedule of when they will be doing their homework for each class, blocking off time as if they must attend classes in person on Monday, Wednesday, and Fridays, or Tuesdays and Thursdays. Having smaller goals will help them to not feel overwhelmed by the bigger picture.

College students have overcome many obstacles throughout the history of higher education. However, this may be the most uncertain time as there is a global pandemic, economic depression (and potential recession), combined with civil unrest. How advisors can best help students is to understand where they are coming from, acknowledge the difficulties they have faced and may continue to face, and then help them pick up the pieces to help them sustain their overall long-term goals. Advisors are not meant to have all the answers, but in order to best serve our students in this current situation, it is critical that academic advisors continue to serve as beacons of hope that can help guide our students through these turbulent waters.

Anne Liotine Academic Advisor Harper College [email protected]

Michael Magee Academic Advisor Harper College [email protected]

Bauman, D. (2018, November 14). Hate crimes on campuses are rising, new FBI data show. The Chronicle of Higher Education . https://www.chronicle.com/article/Hate-Crimes-on-Campuses-Are/245093.

Duckworth, A. L. (2020). Grit scale. Angela Duckworth. https://angeladuckworth.com/grit-scale/

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Dweck, C. (2016). Mindset: The new psychology of success . Ballantine Books.

Fernando, D. M., & Hebert, B. B. (2011). Resiliency and recovery: Lessons from the Asian tsunami and Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development , 39 (1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2011.tb00135.x

Fischer, K. (2020, March 11). When coronavirus closes colleges, some students lose hot meals, health care, and a place to sleep. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/When-Coronavirus-Closes/248228

Keshner, A. (2020, May 22). At least 100 lawsuits have been filed by students seeking college refunds – and they open some thorny questions. MarketWatch . https://www.marketwatch.com/story/unprecedented-lawsuits-from-students-suing-colleges-amid-the-coronavirus-outbreak-raise-3-thorny-questions-for-higher-education-2020-05-21.

Magee, M., Cobb, A., Bodrick, J., & San Antonio, L. (2007). Triumph in the face of adversity: Hurricane Katrina’s effect on African American Students’ coping ability with forced transitions. National Association of Student Affairs Professionals Journal , 10 (1), 97–111.

Perkins-Gough, D. (2013, September). The significance of GRIT. Educational Leadership , 71 (1), 14–20. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272078893_The_significance_of_grit

Cite this article using APA style as: Liotine, A., & Magee, M. (2020, September). Student resilience during times of crisis. Academic Advising Today , 43 (3). [insert url here]

Post Comment

In the current issue.

- Assisting Advisees as They Transition to College Academics

- Deconstructing the Cafeteria Model: Educational Plans as an Agent of Change

- The Doctor is in (Advising)

- Assessment for Faculty Advising: A Brief Review and Recommendations

How to Build Resilience During the Post-Pandemic Transition

Being flexible is key to coping with uncertainty..

Posted April 27, 2021 | Reviewed by Devon Frye

- During the past year, COVID-19 has been a chronic stressor. Research has shown that chronic stressors can be psychologically challenging.

- The confusion and stress of the pandemic have damaged many people's confidence in their own capabilities and ability to make good decisions.

- The science of emotion—and in particular, psychological flexibility—can provide an anchor and compass in navigating this unsettling journey.

This post was written by Robert M. Gordon, Psy.D., and Jed N. McGiffin, Ph.D. Dr. Gordon is a member of the Medicine & Addictions workgroup (established by 14 divisions of the American Psychological Association) that sponsors this blog.

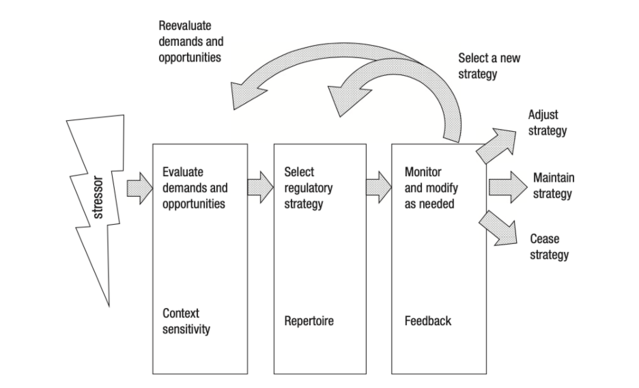

During the past year, COVID-19 has been a chronic stressor , which research has shown to be more psychologically challenging than acute adversity events (Bonanno & Diminich, 2013).

Numerous factors have made COVID-19 potentially traumatic for individuals, including persistent anxiety about being both the agent spreading the virus and the victim of it, the prolonged state of vulnerability and uncertainty as to when the pandemic will end, collective grief and loss, social isolation , and the disruption of daily life (Gordon et al., 2020). The pandemic has precipitated an acute awareness of the fragility of life and aspects of our life that were previously taken for granted (Gold & Zahm, 2020).