Advertisement

Supported by

Gearing Up for the ‘New Normal’

In “The New Normal,” Dr. Jennifer Ashton explores the mental health repercussions of the pandemic and ways to rebuild our overall health.

- Share full article

By Anahad O’Connor

As the chief medical correspondent for ABC News, Dr. Jennifer Ashton has spent the past year helping to make sense of the pandemic for the network’s millions of viewers.

But another aspect of the pandemic that she deals with is the toll it has taken on our nation’s mental health, which she sees on a daily basis at her medical practice in New Jersey, where Dr. Ashton is an obstetrician-gynecologist. In the past year, she says, patient after patient has opened up to her about the crippling stress and uncertainty caused by Covid-19 and their struggles with fear, anxiety, loneliness, frustration and depression.

“I have patients ranging in age from teenagers to women in their 70s and 80s, and they all say this to me,” Dr. Ashton said. “They express it to me almost with this tone that they think there’s something wrong with it. The first thing that I do is I help them recognize that it’s appropriate and it’s OK. Everyone is having these feelings.”

Dr. Ashton explores the psychological toll of the pandemic in her new book, “The New Normal,” which shows us how thinking like a doctor may help us to build resilience and strengthen our overall health. We recently caught up with Dr. Ashton to discuss her thoughts on how the pandemic is affecting our mental health, why it’s essential that we practice self-care during these stressful times, and one of the best hacks she found to improve her diet. Here are edited excerpts from our conversation.

Q. How do you define the “new normal”?

This past year has been filled with so much uncertainty and unfamiliarity. Nothing that we are doing today or have lived through in the last year is normal. The approach that I’ve taken to covering this pandemic has been that of viewing the country as one big patient, and the first step in healing or recovery from any illness is accepting the current situation.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Health

- About the Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Adapting to the culture of ‘new normal’: an emerging response to COVID-19

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jeff Clyde G Corpuz, Adapting to the culture of ‘new normal’: an emerging response to COVID-19, Journal of Public Health , Volume 43, Issue 2, June 2021, Pages e344–e345, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab057

- Permissions Icon Permissions

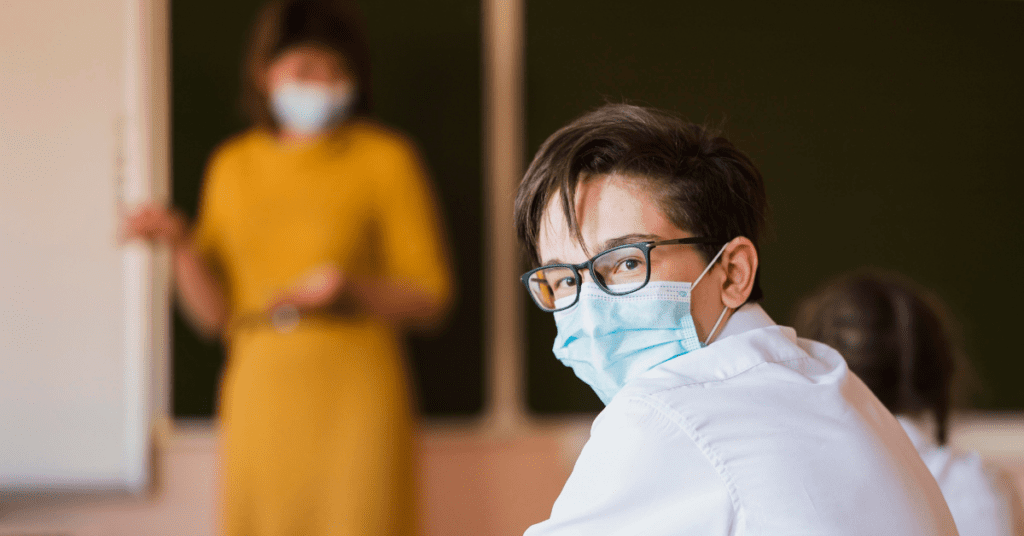

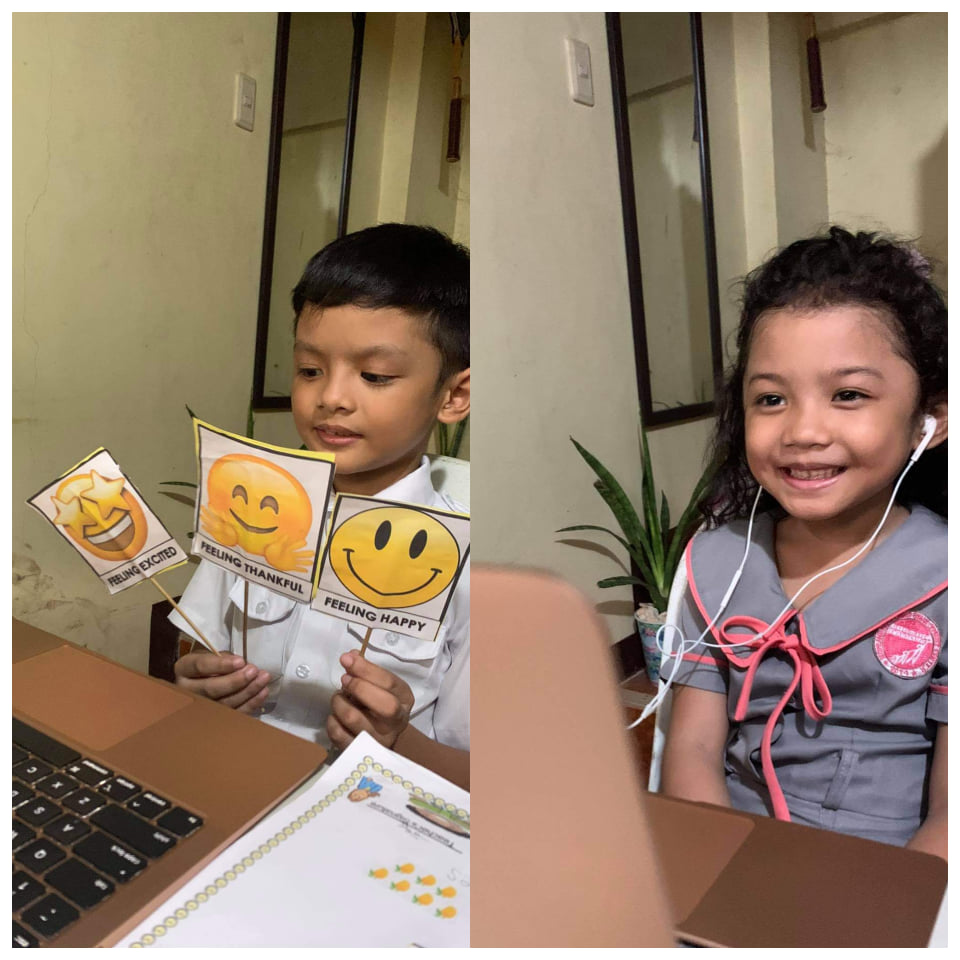

A year after COVID-19 pandemic has emerged, we have suddenly been forced to adapt to the ‘new normal’: work-from-home setting, parents home-schooling their children in a new blended learning setting, lockdown and quarantine, and the mandatory wearing of face mask and face shields in public. For many, 2020 has already been earmarked as ‘the worst’ year in the 21st century. Ripples from the current situation have spread into the personal, social, economic and spiritual spheres. Is this new normal really new or is it a reiteration of the old? A recent correspondence published in this journal rightly pointed out the involvement of a ‘supportive’ government, ‘creative’ church and an ‘adaptive’ public in the so-called culture. However, I argue that adapting to the ‘new normal’ can greatly affect the future. I would carefully suggest that we examine the context and the location of culture in which adaptations are needed.

To live in the world is to adapt constantly. A year after COVID-19 pandemic has emerged, we have suddenly been forced to adapt to the ‘new normal’: work-from-home setting, parents home-schooling their children in a new blended learning setting, lockdown and quarantine, and the mandatory wearing of face mask and face shields in public. For many, 2020 has already been earmarked as ‘the worst’ year in the 21st century. 1 Ripples from the current situation have spread into the personal, social, economic and spiritual spheres. Is this new normal really new or is it a reiteration of the old? A recent correspondence published in this journal rightly pointed out the involvement of a ‘supportive’ government, ‘creative’ church and an ‘adaptive’ public in the so-called culture. 2 However, I argue that adapting to the ‘new normal’ can greatly affect the future. I would carefully suggest that we examine the context and the location of culture in which adaptations are needed.

The term ‘new normal’ first appeared during the 2008 financial crisis to refer to the dramatic economic, cultural and social transformations that caused precariousness and social unrest, impacting collective perceptions and individual lifestyles. 3 This term has been used again during the COVID-19 pandemic to point out how it has transformed essential aspects of human life. Cultural theorists argue that there is an interplay between culture and both personal feelings (powerlessness) and information consumption (conspiracy theories) during times of crisis. 4 Nonetheless, it is up to us to adapt to the challenges of current pandemic and similar crises, and whether we respond positively or negatively can greatly affect our personal and social lives. Indeed, there are many lessons we can learn from this crisis that can be used in building a better society. How we open to change will depend our capacity to adapt, to manage resilience in the face of adversity, flexibility and creativity without forcing us to make changes. As long as the world has not found a safe and effective vaccine, we may have to adjust to a new normal as people get back to work, school and a more normal life. As such, ‘we have reached the end of the beginning. New conventions, rituals, images and narratives will no doubt emerge, so there will be more work for cultural sociology before we get to the beginning of the end’. 5

Now, a year after COVID-19, we are starting to see a way to restore health, economies and societies together despite the new coronavirus strain. In the face of global crisis, we need to improvise, adapt and overcome. The new normal is still emerging, so I think that our immediate focus should be to tackle the complex problems that have emerged from the pandemic by highlighting resilience, recovery and restructuring (the new three Rs). The World Health Organization states that ‘recognizing that the virus will be with us for a long time, governments should also use this opportunity to invest in health systems, which can benefit all populations beyond COVID-19, as well as prepare for future public health emergencies’. 6 There may be little to gain from the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is important that the public should keep in mind that no one is being left behind. When the COVID-19 pandemic is over, the best of our new normal will survive to enrich our lives and our work in the future.

No funding was received for this paper.

UNESCO . A year after coronavirus: an inclusive ‘new normal’. https://en.unesco.org/news/year-after-coronavirus-inclusive-new-normal . (12 February 2021, date last accessed) .

Cordero DA . To stop or not to stop ‘culture’: determining the essential behavior of the government, church and public in fighting against COVID-19 . J Public Health (Oxf) 2021 . doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab026 .

Google Scholar

El-Erian MA . Navigating the New Normal in Industrial Countries . Washington, D.C. : International Monetary Fund , 2010 .

Google Preview

Alexander JC , Smith P . COVID-19 and symbolic action: global pandemic as code, narrative, and cultural performance . Am J Cult Sociol 2020 ; 8 : 263 – 9 .

Biddlestone M , Green R , Douglas KM . Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19 . Br J Soc Psychol 2020 ; 59 ( 3 ): 663 – 73 .

World Health Organization . From the “new normal” to a “new future”: A sustainable response to COVID-19. 13 October 2020 . https: // www.who.int/westernpacific/news/commentaries/detail-hq/from-the-new-normal-to-a-new-future-a-sustainable-response-to-covid-19 . (12 February 2021, date last accessed) .

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| March 2021 | 331 |

| April 2021 | 397 |

| May 2021 | 1,112 |

| June 2021 | 1,714 |

| July 2021 | 1,767 |

| August 2021 | 1,638 |

| September 2021 | 3,977 |

| October 2021 | 8,281 |

| November 2021 | 6,445 |

| December 2021 | 4,287 |

| January 2022 | 6,424 |

| February 2022 | 7,286 |

| March 2022 | 8,709 |

| April 2022 | 7,282 |

| May 2022 | 7,307 |

| June 2022 | 5,175 |

| July 2022 | 2,404 |

| August 2022 | 2,940 |

| September 2022 | 7,021 |

| October 2022 | 7,134 |

| November 2022 | 5,171 |

| December 2022 | 3,236 |

| January 2023 | 3,796 |

| February 2023 | 3,344 |

| March 2023 | 4,316 |

| April 2023 | 2,826 |

| May 2023 | 3,263 |

| June 2023 | 1,742 |

| July 2023 | 988 |

| August 2023 | 1,592 |

| September 2023 | 2,701 |

| October 2023 | 1,847 |

| November 2023 | 1,354 |

| December 2023 | 865 |

| January 2024 | 1,025 |

| February 2024 | 1,232 |

| March 2024 | 1,257 |

| April 2024 | 1,169 |

| May 2024 | 902 |

| June 2024 | 337 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1741-3850

- Print ISSN 1741-3842

- Copyright © 2024 Faculty of Public Health

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE - PMC COVID-19 Collection

COVID-19 Pandemic and Stress: Coping with the New Normal

Anjana bhattacharjee.

1 Dept. of Psychology, Tripura University, Suryamani Nagar, Tripura, India

Tatini Ghosh

COVID-19 is the new face of pandemic. Since the discovery of COVID-19 in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, it has spread all over the world and the numbers are increasing day by day. Anyone can be susceptible to this infection but children, older adults, pregnant women, and people with comorbidity are more vulnerable. The spread of coronavirus resulted in closures of schools, businesses, and public spaces worldwide and forced many communities to enact stay at home orders, causing stress to all irrespective of their age, gender, or socioeconomic status. The sudden and unexpected changes caused by the outbreak of coronavirus are overwhelming for both adults and children, causing stress and evoking negative emotions like fear, anxiety, and depression, among different populations. The aim of the paper is to ascertain how stress during this pandemic inculcates various psychological health issues like depression anxiety, OCD, panic behavior, and so on. Further, the paper is an attempt to identify different general as well as population specific coping strategies to reduce the stress level among individuals and prevent various stress-induced psychological disorders with reference to different theories and research articles.

COVID-19, also known as coronavirus disease, is a severe respiratory disease first discovered in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Since then, it has spread globally. The World Health Organization declared it a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” on the 30 th of January 2020. There were more than 365,000 confirmed cases worldwide by October 2020 ( World Health Organization, 2020 ). According to report by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India (2021), since the inception of COVID-19 in India, there were more than 10,130,000 cases till february 2021. Even though vaccination has started in India and many parts of the world, the COVID-19 cases are still increasing day by day. The common symptoms of coronavirus are fever, cough, shortness of breath, and in some cases no symptoms at all. Anyone can be susceptible to this infection but children, older adults, pregnant women, and people with comorbidity are more vulnerable to this virus ( World Health Organization, 2020 ; National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, 2020 ).

According to the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences ( NIMHANS, 2020 ) the sudden lockdown and restricted mobility, along with isolation and social distancing during the starting of the pandemic, has caused stress, boredom, irritation, adjustment disorder, frustration and aggressive behavior. The sudden drastic change in known usual life acted as a gateway for increasing mental illness. A study shows that any severe epidemic or outbreak in society generally has severe negative effects on the society as well on the lives of humans ( Dodgen et al., 2002 ).

The unexpected outbreak of COVID-19 and its related consequences are causing severe changes in our lifestyle. These sudden changes can be overwhelming for both adults and children causing stress and evoking negative emotions like stress, fear, anxiety, depression among different populations. Several studies stated that the most prevalent mental health issues reported during the pandemic are stress, anxiety, fear, anger, insomnia, and denial. These issues were seen among different population groups ranging from children to older people, frontline workers, and people with pre-existing physical and mental health issues ( Roy et al., 2020 ; Torales et al., 2020 ). Different studies found that stress, anxiety, and depression coincide with the COVID-19 pandemic and due to the ongoing pandemic, there is an increase in the prevalence rate of these mental health issues around the globe ( Mohindra et al., 2020 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ).

A study comprising of 113,285 participants from India, China, Spain, Italy, and Iran revealed that among this surveyed population, the prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress was 20%, 35%, and 53%, respectively, during the pandemic and it seems to be increasing day by day ( Lakhan et al., 2020 ). A similar study found prevalence of post-traumatic stress among the general population has increased from 23.88% to 24.84% during the pandemic ( Cooke et al., 2020 ). A study on racial and ethnic disparity of stress and other mental health conditions during COVID-19 showed that Hispanic adults have four times higher prevalence of psychological stress and mental health issues than any other ethnic groups in the United States, along with increases in substance use and suicidal ideation ( McKnight-Eily et al., 2021 ). Wu et al. (2020) reported in a study that life stress, especially stress associated with uncertainty, has led to mental health disorders. The higher the level of perceived uncertainty stress, the greater the prevalence of mental health disorders. The study further found that the prevalence of mental health disorders due to the COVID-19 pandemic was 22.8%.

Abbott (2021) investigated stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and its related consequences and found that there is an increase in prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression in the U.S. population from 11% to 42% due to this pandemic. The surge in stress among people is also during the rise of new COVID-19 covariant cases. A recent study showed an association between high level of stress, anxiety, and sleep disturbance and the period of social distancing ( Esteves et al., 2021 ).

Currently, several vaccines are being produced and vaccination has started, resulting in the discontinuation of lockdown orders in most countries. Educational institutions and workplaces are reopening and people are returning to the new normal life, maintaining social distancing. Recently Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2021) reported a sudden surge during December 2020 in COVID-19 cases all over the world, due to a new covariant of COVID-19 virus that was first, testified by the Government of United Kingdom (UK) to World Health Organization (WHO). The new variants are reported to be more infectious and spread more easily among people. This is again aggravating the situation and increasing stress in people even after being vaccinated due to excessive fear and uncertainty.

The objectives of this article are two-fold. First it explores how stress plays a significant role in increasing the number of mental health problems during this pandemic. Second, it tries to identify different general as well as population specific coping mechanisms for dealing with this stressful situation with reference to different theories (both on stress and coping) and research articles.

Methodology

This paper reviews secondary data available through conceptual models, various past journals, research papers, and other useful websites related to coronavirus pandemic and its psychological effect on people. Finally, the paper extensively reviews different articles related to psycho-social coping mechanisms to reduce stress level among individuals.

When conducting this review research, related articles were focused on and keywords like “coronavirus,” “coronavirus and mental health,” “COVID-19,” “stress,” “psychological disorder,” and “coping strategies” were used. In order to identify articles that focused on specific terms like, “stress,” “pandemic and mental health,” “depression,” “anxiety,” “post-traumatic stress disorder,” and other related terms were used. The databases that were used for identifying related articles were Google Scholar, Medline, PubMed, NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information), and various other journals. Figure 1

PRISM diagram of systematic literature review process.

The systematic review started with 1137 articles, which were screened and reviewed and some were removed on different grounds. Finally, 106 articles were selected for the review article based on aims and objectives of the paper. The selection process of different articles is shown in the following PRISM flow chart. Finally, conclusions have been made on the basis of findings from different reviewed articles. Figure 2

Table showing discussion.

Theories of Stress

Hans selye’s theory.

In the year of 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, Han Selye elaborated on the Walter Cannon’s theory of fight-or-flight reaction to stress and named it general adaptation syndrome (GAS). In this theory, Han Selye explained GAS as a physiological reaction to stress consisting of three stage reactions, namely: alarm reaction stage, resistance stage, and exhaustion stage ( Selye, 1956 ). When a person faces a stressful situation, alarm reaction stage is initiated. During this stage the body prepares itself for fight-or-flight reaction and makes the necessary physiological changes in body. If the stressor persists, the body progress to the second stage (the resistance stage), where the body reacts in an opposite way of alarm reaction and tries to repair the body from any damage. If the stressor still continues, in the third stage (exhaustion stage), the body’s energy is depleted and the person succumbs to various mental and physical health issues caused by the extreme stress. Selye (1991) further stated that prolonged exposure to extreme stress can cause mental and physical illness, or even death.

The transactional model of Stress

The transactional model of stress developed by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) explained that the feeling of stress is cumulative in nature. The amount of stress we experience is the result of our thoughts, feelings, emotions, and behaviors attached with our evaluation of our external and internal demands. When the demands of the external and internal environment exceed the resources we possess, it causes stress. If the situational demands are more than that of the available resources, it causes stress in multiple ways: acute, episodic or intermittent, and chronic, which further result in physical and mental dysfunction.

Conservation of resources (COR) theory

This theory ( Hobfoll, 1989 ) proposed a framework of stress and what resources are needed to be conserved for physical and mental well-being, in the face of stressors. According to COR theory, the primary motive of human beings is to conserve resources and tools that would help to maintain their overall well-being. COR states that there are four primary kinds of resources (e.g., objects, conditions, personal characteristics, and energies) that help in fostering and protecting well-being. It proposes that individuals lacking in resources will be more vulnerable to experience stress and those with abundant resources will be resilient to stress ( Hobfoll et al., 1996 ).

Holmes and Rahe’s model of stress

Holmes and Rahe’s (1967) developed a model of stress associated with major life changes, which cause stress and ultimately may result in illness. The model states that there is a positive correlation between stress inducing major life changes and illness. In other words, with an increase in major life events, there is greater likelihood of developing subsequent illness.

Stress-disease model

According to the stress-disease model by Kagan and Levi (1971) , there are several components explain how stress can lead to disease. First, stressors or stressful situations (both social or psychological stressors), second, the individual psychobiological programming (genetic and predisposing factors, learning, and previous experiences), third, how an individual reacts to stress. When the three components work together, it leads to the fourth component, that is, precursors of disease, which ultimately leads to the final outcome which is physical illness. This model explains how different physiological pathways can act as a mediator between stress and physical illness/disease ( Levi & Kagan, 1971 ).

Stress-Induced Mental Health Problems During COVID-19

Humans are social animals and it is a human tendency to establish social interactions with others. Due to COVID-19, our social interactions have been cut down, thus resulting in psychological distress ( Usher et al., 2020 ). Brodeur et al. (2004) revealed that the pandemic is severely affecting our mental health and there is an increase in web searches for loneliness, anxiety, depression, suicide, and divorce. Similarly, other studies also showed that epidemic and post-epidemic situations can cause psychological problems like stress, anxiety, and stigma as well as long lasting effects like post-traumatic stress symptoms and physical conditions like migraines and headaches ( Bhugra, 2004 ; Brooks et al., 2020 ; Cheng et al., 2004 ; Duan & Zhu, 2020 ; Fan et al., 2015 ). Post-traumatic stress disorder is a serious concern in the times of the COVID-19 pandemic, and females were found to be more prone psychological problems ( Alshehri et al., 2020 ; Bridgland et al., 2021 ).

In a recent study, Dubey et al. (2020) revealed that the current pandemic situation has not only affected the health of people but also badly affected the economy of the country. It has caused fear amongst people, which they have termed as “coronaphobia.” Many studies have revealed that stress, anxiety, fear, depression, and other psychological disorders are very commonly experienced during pandemic situations. The pandemic stress has a devastating effect on mental health ( Kumar & Nayar, 2021 ; Montano & Acebes, 2020 ; Van Bortel et al., 2016 ). Many studies over the past few decades proved that the impact of psychological stress is harmful for the immune system and the body’s response to vaccines, and these findings are applicable for COVID-19 vaccine as well ( Madison et al., 2021 ; Xiang et al., 2020 ).

A study by Shrilatha and Durga (2020) revealed that during this pandemic there was a rise in the use of social media and smartphones to is more than four hours a day, and the most used app was found to be WHATSAPP . Along with the increase in social media use, the use of other apps like ZOOM and HOUSE PARTY are also increasing since people are working from home ( Chanchani & Mishra, 2020 ). Even though social media helps in connecting with others from home, still there is a big disadvantage to it. During the coronavirus pandemic, social media is overloaded with misinformation and rumors that create more stress, fear, and panic among all ( Kumar & Nayar, 2021 ). Fear of COVID-19 due to misinformation results in the spread of maladaptive, obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Fear of contamination and regular washing of hands are common symptoms of OCD. Stress during COVID-19 and unavailability of proper treatment and therapy can lead to initiation and maintenance of OCD ( Adams et al., 2018 ).

The study of Kashif et al. (2020) revealed that along with the spike in screen usage, there has been a spike in cyber-crime during the coronavirus period. It has been further reported that personal data have also been stolen and hacked. Similar studies showed that there has been an increase in the number of cyber-crimes and cyber frauds since the first case of coronavirus in China and cyber fraud can lead to fear, panic, and stress ( Gross et al., 2016 ; Lallie et al., 2020 ). At such critical times, when hard earned money is lost, it can cause mental distress that may further develop severe psychological disorders. Hence financial loss and hardships can lead to psychological distress ( Bradshaw & Ellison, 2020 ).

Increased stress also plays a key role in substance abuse and addiction ( Sinha, 2001 ), and the stress, anxiety, and increased isolation lead people to indulge in use of psychoactive substances (like smoking, drugs, and alcohol drinking) and other substance dependent behaviors (like excessive use of social media, online gaming, and pornography). This results in substance abuse disorders during the pandemic ( Clay & Parker, 2020 ; Columb et al., 2020 ).

According to the WHO (2020) , due to the current pandemic and related measures taken to control it like social distancing, lockdown, etc., there has been a rise in the hazardous use of alcohol and drug, as well as suicidal ideation and attempts. Similarly, studies by Cheung et al. (2008) and Gardner et al. (2020) showed that pandemics can increase the rate of suicide among older adults. Not only isolation and loneliness but also death of a near one from COVID-19 are also risk factors for the suicidal ideation of an individual ( Sahoo et al., 2020 ). Figure 3

Summary of review on stress induced mental health problems during COVID-19.

Theories of Coping

Haan’s model of coping, defense, and fragmentation.

Norma Haan (1963) proposed a triarchic model of coping and described how the ego processes different stressors of daily life by using coping, defense, and fragmentation. She proposed in her model that “ego process” is a psychological approach in dealing with the stressors of daily life, which ultimately helps in sustaining a realistic connection with the self and the environment ( Haan, 1969 ). Haan (1993) defined three ways of dealing with stressors: coping, defense, and fragmentation. Coping is an effort to overcome the hardships of life by reaching out and within self for resources. Defense is an unconscious mechanism that greatly helps in reducing anxiety from harmful stimuli. Fragmentation is a method to adapt or accept failure when the stress is too extreme to handle/cope and may result in psychotic behavior. Thus, by controlling belief or behavior (defense), an individual can cope with the stressors, whereas when coping or defense fails, fragmentation occurs ( Haan, 1977 ).

Lazarus and Folkman’s theory of coping

Lazarus and Folkman propounded a theory of coping with stress ( Folkman & Lazarus, 1885 , 1991 ; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 ), and the theory emphasized how coping transactionally interacts with cognition and emotion. According to the theory ( Lazarus & Folkman, 1987 ), there are two types of coping, namely: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping deals with focusing with the problem, planning, and taking action and steps proactively about the problem, which may include gathering resources, seeking social support, or taking action to change or to overcome the problematic situation. On the contrary, emotion-focused coping deals with focusing more on the emotions, while dealing and managing the emotions caused due to the stressors. Emotions can be dealt by meditation, yoga, venting out frustrations, focusing on the positive, etc. Folkman (2013) explained that coping involves resorting to both cognitive and behavioral responses to manage the internal and external stressors.

The Hardiness Theory

Kobasa (1979) had defined hardiness as a personality type that helps in overcoming stress related illness. Hardiness is a general feeling of being satisfied with the environment. Maddi and Kobasa’s (1984) , hardiness theory of coping emphasizes that a hardy person would view stressful or challenging situations as a meaningful and interesting situation and an opportunity for personal growth. Such kind of outlook towards challenges helps people to remain healthy during stress. According to the theory, there are three ways to adhere to hardiness as coping: First, “controlling” the beliefs that can influence their environment; second, “commitment” and deep involvement in their tasks and duties; third, viewing “challenges” as an opportunity for growth and working for it.

The sense of coherence theory

Sense of coherence (SOC) ( Antonovsky, 1987 ) refers to a coping technique to deal with life stressors and emotional distress. It a feeling of confidence that both internal and external environment are predictable. According to the sense of coherence theory, there are three elements that are necessary for coping with daily life stressors: comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. People with weak SOC have a pessimistic outlook that things will go wrong in the end, whereas people with strong SOC have a good understanding of life and anticipate that all will turn good in the end. By successfully applying the elements of coherency, it is possible to cope with stress without hampering the physical health.

Stress and coping social support theory

The stress and coping social support theory by Cohen and Wills (1985) explained that social support acts as a coping method that protects the people from the stresses of life and the harmful physical effect of stressors. The theory further suggests that social support promotes adaptive appraisal and coping techniques in dealing with stressful events ( Thoits, 2010 ). According to Glanz et al. (2015) there are four types of social support that assist in coping with stress: emotional support comprising love, care, understanding; information support referring to information, guidance, and counseling; appraisal support referring to providing evaluative help; and finally, instrumental support referring to the physical or action-oriented help.

Suggestive Coping Strategies (General and Specific) During Pandemic

General psycho-social coping techniques.

According to various reports by International and National Institutes, like Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 2021 ; National Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences (NIMHANS), 2020 and World Health Organization, 2020 , different psychological coping strategies have been suggested to reduce stress levels among individuals and to prevent various psychological disorders. COVID-19 has increased people's psychological burden and caused severe stress, which has challenged the resilience and coping ability to overcome hardships ( Polizzi et al., 2020 ). So, it is very requisite of the moment to foster and practice some psycho-social coping strategies to overcome stresses associated with COVID-19.

- 1. Psycho-education refers to educating people about various psychological disorders and their consequences. A study showed that psycho-education has helped people to deal with psychological disorders more successfully than those who were not given psycho-education ( Vieta, 2005 ).

- 2. Acceptance is an important coping mechanism to deal with stressors. If acceptance of the prevailing circumstances is not there, then it can lead to a negative coping strategy known as denial, which is very dangerous. In denial, the person will not follow any guidelines and it may affect others as well. One study shows that acceptance is a good way to cope with stressors and their harmful physical effects ( Lindsay et al., 2018 ).

- 3. Practice Positive Thinking. One negative thought leads to another and it creates a chain reaction of negative thoughts. To break this cycle, positive thinking practice should be adopted. Positive thinking refers to the process of focusing on positive emotions and positive behavioral habits. One study on positive thinking shows that it helps in coping with stress, anxiety, and other psychological disorders as well ( Naseem & Khalid, 2010 ).

- 4. Cognitive redefinition is a psychological coping strategy to redefine or change the way we see, perceive, and feel about any situation or events. Instead of perceiving this current pandemic situation as something very stressful, cognitive redefining can help in perceiving this as time to reconnect with family and to indulge in creative activities and self-care. One study shows that cognitive redefinition or change in mindset is helpful in dealing with stressful situations ( Crum et al., 2013 ).

- 5. Limiting Social Media and News. According to The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, too much information and news about the COVID-19 pandemic can be overwhelming and upsetting, and it can cause panic among the people. So, it has been suggested to limit social media use and listening/reading news about the current pandemic situation. It has also been suggested by WHO to read about it from trusted sources only, as, factual information can help lessen fear and panic.

- 6. Proper Sleep Hygiene. The current pandemic situation is very crucial for everyone and it is very important to be biologically fit so as to reduce the risk of COVID-19 and its associated issues. Studies proved that having proper sleep hygiene can help in dealing with stress, anxiety, mood disturbances, and other mental health problems associated with the current pandemic ( Jakupcak et al., 2020 ; Thoits, 2010 ).

- 7. Physical Fitness. It has been reported that regular physical exercise not only boosts physical health but also helps in mental health by reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. It would be helpful to do regular physical exercises at home during this pandemic to stay fit both physically and mentally ( Altena et al., 2020 ; Muraki et al., 1993 ; Sunder et al., 2020 ).

- 8. Spending Time on Hobbies. Currently, we are either locked at home or have restricted mobility due to the pandemic situation. So, there is an immense amount of time for us at home now. We can utilize the time by indulging in various activities like cooking, painting, gardening, etc. One study shows that people who indulges in hobbies in their leisure time are less likely to have mental health issues than those who do not have hobbies ( Jeoung et al., 2013 ). Reports by NIMHANS advised people to indulge in various activities so as to distract themselves from the constant worrying about the situation.

- 9. Work life Balance. During the current COVID-19 outbreak when many people are working from home to avoid contamination, it has become very important to maintain work–life balance. Work–life balance is the process of maintaining a proper balance between work and other activities of daily life in a way that one does not hamper the other. Studies also prove that maintaining a proper work life balance boosts positive mental health and reduces anxiety and depression among employees ( LaBrie et al., 2010 ).

- 10. Healthy Daily Routine. Day-to-day routines have been disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it negatively hampers our both physical and mental health. Various reports show that unhealthy life styles impede our physical and mental health whereas healthy lifestyle like eating healthy, getting enough sleep, focusing on positive thoughts, etc. can boost healthy mind and body ( Haar et al., 2014 ; Takeda et al., 2015 ).

- 11. Mindfulness Practice. Mindfulness refers to the state of physical and mental awareness of a person, without being affected by the surroundings. There are various mindfulness techniques like meditation, physical exercise, yoga, guiding imagery and spiritual practices. Studies also show that mindfulness practices help in dealing with mental and emotional disorders and also boost physical health ( Call et al., 2014 ; Koenig, 2010 ; Mayo Clinic, 2020 ; Melnyk et al., 2006 ).

- 12. Following Government Guidelines. It is being advised all the time to follow the Government guidelines to curb the COVID-19 outbreak. Some of the guidelines by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India suggest to maintain social distancing, wear face coverings whenever outside, wash hands using soap regularly and avoid public gathering.

- 13. Professional Help. Urgent professional help has to be sought if the person is not able to deal with the sudden life changes and if it is severely hampering their physical and mental health. If people are suffering from any kind of physical and emotional disorder, professional help like consulting a psychologist, counselor, or psychiatrist is advisable ( Wang et al., 2020 ).

- 14. Avoid Stigmatization. There has been negative attitudes and stigma about mental health exist. Due to stigma attached to mental health and mental health care providers, people hesitate to express their mental turmoil or stress, which further leads to serious psychological conditions. So, it is suggested to avoid stigmatizing mental health or mental health professionals and seek help whenever needed ( Yang, 2007 ).

- 15. Good Social Support. Studies reveal that people who have good social support are less likely to have any psychological disorders. People with good social networking will have less or no depression, suicidal thoughts, or suicidal risk in the future ( Duan & Zhu, 2020 ). So, it is important to have good social support during this pandemic situation and to stay connected with family or friends through various online mediums.

Specific coping techniques

Besides the above-mentioned general coping strategies, which are suggested for everyone irrespective of any sociodemographic differences to cope up with a stressful life, there are certain coping techniques that are being followed by people belonging to specific age, gender, and community.

- • Age Specific Coping. People of different age groups face different levels of stress, and hence, their coping techniques are different as well ( Paykel, 1983 ). Cognitive behavior therapy seems to help in reducing PTSD, stress, depression, and anxiety among youth during periods of crisis and improves resilience ( Chen et al., 2014 ) whereas, avoidant coping seems to escalate PTSD ( McGregor et al., 2015 ). Youth also seem to apply approach coping and habitual coping styles ( Steiner et al., 2002 ); active coping followed by social coping and avoidant coping style (Brown et al., 2015). Further studies revealed that older adults seem to prefer problem-focused coping in terms of stressful events ( Chen et al., 2017 ); proactive coping ( Pearman et al., 2021 ); adaptive and active strategies of coping ( Kuria, 2012 ).

- • Gender Specific Coping. Several studies have reported gender-differences in terms of coping strategies ( Matud, 2004 ; Ptacek et al., 1994 ). Men seem to resort to approach coping style (Gan et al., 2009), problem-focused approach ( Sinha & Latha, 2018 ; Tolor & Fehon, 1987 ), rational, detachment and rumination coping style ( Matud, 2004) , and cognitive hardiness ( Beasley et al., 2003 ), whereas women are found to use emotion-focused coping style ( Loukzadeh & Mazloom Bafrooi, 2013 ; Manna et al., 2007 ), avoidance coping style followed by approach coping style ( Gan et al., 2009 ), planned-breather leisure coping method ( Tsaur & Tang, 2012 ), active coping strategies ( Lin, 2016 ), and social support ( Linnabery et al., 2014 ).

- • Community Specific Coping. There are variations in the use of coping strategies based on community and racial differences. White Americans are found to use approach behavior coping style, whereas African-Americans are more likely to use avoidance cognitive coping style ( Anshel et al., 2009 ). Similarly, African-American young adults were found to resort to avoidance coping style in comparison to White young adults, who prefer problem-focused coping ( Van Gundy et al., 2015 ). White women seem to use a self-directing coping style, whereas African-American women more often use religious coping ( Ark et al., 2006 ).

COVID-19 is the new face of the pandemic, and it has put the whole world into a pause. It has become a threat to the entire civilization. The COVID-19 pandemic not only affects physical health but also severely affects the mental health of people, whether infected or not. Nationwide lockdowns, social isolation, and restricted mobility have increased the prevalence of mental health problems, and people all over the world are suffering from loneliness, feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, anxiety, stress, and adjustment disorder. Not only these, dependency on social media and alcohol and other psychoactive substances has increased, which further raises the incidents of domestic violence or intimate partner violence. So, healthcare providers should give attention to both physical and psychological well-being of the people. Hence, it is the need of the hour to follow all the physical measures suggested by the healthcare professionals to prevent COVID-19, along with practicing psycho-social coping strategies for better quality of life and overall sound health and well-being of the individual.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Tatini Ghosh https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7221-9381

- Abbott A. (2021). COVID's mental-health toll: how scientists are tracking a surge in depression . Nature , 590 , 194–195. 10.1038/d41586-021-00175-z. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Adams T. G., Kelmendi B., Brake C. A., Gruner P., Badour C. L., Pittenger C. (2018). The role of stress in the pathogenesis and maintenance of obsessive-compulsive disorder . Chronic Stress , 2 , 2470547018758043. 10.1177/2470547018758043. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alshehri F. S., Alatawi Y., Alghamdi B. S., Alhifany A. A., Alharbi A. (2020). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia . Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal , 28 ( 12 ), 1666–1673. 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.10.013. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Altena E., Baglioni C., Espie C. A., Ellis J., Gavriloff D., Holzinger B., Schlarb A., Frase L., Jernelöv S., Riemann D. (2020). Dealing with sleep problems during home confinementdue to the COVID‐19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT‐I Academy . Journal of Sleep Research , 29 ( 4 ), e13052. 10.1111/jsr.13052. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anshel M. H., Sutarso T., Jubenville C. (2009). Racial and gender differences on sources of acute stress and coping style among competitive athletes . The Journal of Social Psychology , 149 ( 2 ), 159–178. 10.3200/socp.149.2.159-178. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antonovsky A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well : Jossey-Bass. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1987-97506-000 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Ark P. D., Hull P. C., Husaini B. A., Craun C. (2006). Religiosity, religious coping styles, and health service use: racial differences among elderly women . Journal of Gerontological Nursing , 32 ( 8 ), 20–29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16915743/ . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beasley M., Thompson T., Davidson J. (2003). Resilience in response to life stress: the effects of coping style and cognitive hardiness . Personality and Individual Differences , 34 ( 1 ), 77–95. 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00027-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhugra D. (2004). Migration and mental health . Acta Psychiatricascandinavica , 109 ( 4 ), 243–258. 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00246.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradshaw M., Ellison C. G. (20201982). Financial hardship and psychological distress: Exploring the buffering effects of religion . Social Science & Medicine , 71 ( 1 ), 196–204. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.015. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bridgland V. M. E., Moeck E. K., Green D. M., Swain T. L., Nayda D. M., Matson L. A., Hutchison N. P., Takarangi M. K. T. (2021). Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor . Plos One , 16 ( 1 ), e0240146. 10.1371/journal.pone.0240146. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brodeur A., Clark A. E., Fleche S., Powdthavee N. (2004). Assessing the impact of the coronavirus lockdown on unhappiness, loneliness, and boredom using Google Trends . arXiv preprint arXiv:.12129 https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.12129 .

- Brooks S. K., Webster R. K., Smith L. E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence . Lancet , 395 ( 10227 ), 912–920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown S. M., Begun S., Bender K., Ferguson K. M., Thompson S. J. (2015). An exploratory factor analysis of coping styles and relationship to depression among a sample of homeless youth . Community Mental Health Journal , 51 ( 7 ), 818–827. 10.1007/s10597-015-9870-8. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Call D., Miron L., Orcutt H. (2014). Effectiveness of brief mindfulness techniques in reducing symptoms of anxiety and stress . Mindfulness , 5 ( 6 ), 658–668. 10.1007/s12671-013-0218-6. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/managing-stress-anxiety.html .

- Chanchani M., Mishra D. (15th April 2020). “Mobile apps’ usage spikes in lockdown” . Times of India https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/mobile-apps-usage-spikes-in-lockdown/articleshow/75148768.cms .13

- Cheng S. K. W., Wong C. W., Tsang J., Wong K. C. (2004). Psychological distress and negative appraisals in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) . Psychological Medicine , i ( 4 ), 1187–1195. 10.1017/s0033291704002272. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen Y., Peng Y., Xu H., O’Brien W. (2017). Age differences in stress and coping: problem-focused strategies mediate the relationship between age and positive affect . The International Journal of Aging and Human Development , 86 ( 4 ), 347–363. 10.1177/0091415017720890. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen Y., Shen W. W., Gao K., Lam C. S., Chang W. C., Deng H. (2014). Effectiveness RCT of a CBT intervention for youths who lost parents in the Sichuan, China, earthquake . Psychiatric Services , 65 ( 2 ), 259–262. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200470. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheung Y. T., Chau P. H., Yip P. S. (2008). A revisit on older adults’ suicides and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong . International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry , 23 ( 12 ), 1231–1238. 10.1002/gps.2056. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clay J. M., Parker M. O. (2020). Alcohol use and misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: a potential public health crisis? The Lancet. Public Health , 5 ( 5 ), e259. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30088-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen S., Wills T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis . Psychological Bulletin , 98 ( 2 ), 310–357. 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Columb D., Hussain R., O’Gara C. (2020). Addiction psychiatry and COVID-19: Impact on patients and service provision . Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine , 37 ( 3 ), 164–168. 10.1017/ipm.2020.47. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooke J. E., Eirich R., Racine N., Madigan S. (2020). Prevalence of posttraumatic and general psychological stress during COVID-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis . Psychiatry Research , 292 , 113347. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113347. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crum A. J., Salovey P., Achor S. (2013). Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 104 ( 4 ), 716–733. 10.1037/a0031201. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences (NIMHANS) (2020). Mental health in the times of COVID-19 Pandemic, guidelines for general medical and specialised mental health care settings (pp. 1–177). National Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences (NIMHANS). Retrieved from: http://nimhans.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/MentalHealthIssuesCOVID-19NIMHANS.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Dodgen D., LaDue L. R., Kaul R. E. (2002). Coordinating a local response to a national tragedy: Community mental health in Washington, DC after the Pentagon attack . Military Medicine , 167 ( 4 ), 87–89. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12363154/ . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Duan L., Zhu G. (2020). Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic . The Lancet Psychiatry , 7 ( 4 ), 300–302. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dubey S., Biswas P., Ghosh R., Chatterjee S., Dubey M. J., Chatterjee S., Lahiri D., Lavie C. J. (2020). Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 . Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome , 14 ( 5 ), 779–788. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Esteves C. S., Oliveira C. R. D., Argimon I. I. D. L. (2021). Social distancing: Prevalence of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms among Brazilian students during the COVID-19 pandemic . Frontiers in Public Health , 8 , 589966. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.589966. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fan F., Long K., Zhou Y., Zheng Y., Liu X. (2015). Longitudinal trajectories of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among adolescents after the Wenchuan earthquake in China . Psychological Medicine , 45 ( 13 ), 2885–2896. 10.1017/S0033291715000884. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Folkman S. (2013). Stress: Appraisal and Coping . In Gellman M.D., Turner J.R. (Eds), Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine New York, NY: Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_215. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 48 ( 1 ), 150–170. 10.1037//0022-3514.48.1.150. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R. S. (1991). Coping and emotion . In Monat A., Lazarus R. S. (Eds), Stress and Coping: An anthology (pp. 208–227)New York: Columbia University Press. https://www.scirp.org/(S(lz5mqp453edsnp55rrgjct55))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1955093 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Gan Q., Anshel M. H., Kim J. K. (2009). Sources and cognitive appraisals of acute stress as predictors of coping style among male and female Chinese athletes . International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 7 ( 1 ), 68–88. 10.1080/1612197x.2009.9671893. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gardner W., States D., Bagley N. (2020). The Coronavirus and the risks to the elderly in long-term care . Journal of Aging & Social Policy , 32 ( 4-5 ), 310–315. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1750543. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glanz K., Rimer B. K., Viswanath K. (Eds), (2015). John Wiley & Sons. https://www.wiley.com/en-in/Health+Behavior:+Theory,+Research,+and+Practice,+5th+Edition-p-9781118628980 . Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice [ Google Scholar ]

- Gross M. L., Canetti D., Vashdi D. R. (2016). The psychological effects of cyber terrorism . Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists , 72 ( 5 ), 284–291. 10.1080/00963402.2016.1216502. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haan N. (1963). Proposed model of ego functioning: Coping and defense mechanisms in relationship to IQ change . Psychological Monographs , 77 ( 8 ), 1–23. 10.1037/h0093848. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haan N. (1969). A tripartite model of ego functioning values and clinical and research applications . Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease , 148 ( 1 ), 14–30. 10.1097/00005053-196901000-00003. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haan N. (1977). Coping and defending: Processes of self-environment organization : Academic Press. https://www.elsevier.com/books/coping-and-defending/haan/978-0-12-312350-3 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Haan N. (1993). The assessment of coping, defense, and stress . In Goldberger L., Breznitz S. (Eds), Handbook of stress: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects (2nd ed., pp. 258-273)New York: Free Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-97397-013 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Haar J. M., Russo M., Suñe A., Ollier-Malaterre A. (2014). Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures . Journal of Vocational Behaviour , 85 ( 3 ), 361–373. 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.010. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hobfoll S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress . American Psychologist , 44 ( 3 ), 513–524. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hobfoll S. E., Freedy J. R., Green B. L., Solomon S D. (19961996). Coping reactions to extreme stress: The roles of resource loss and resource availability . In Zeidner M, Endler N S. (Eds), Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications (pp. 322–349)New York: Wiley. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-97004-015 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Holmes T. H., Rahe R. H. (1967). The Social Readjustment Rating Scale . Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 11 ( 2 ), 213–218. 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jakupcak M., Vannoy S., Imel Z., Cook J. W., Fontana A., Rosenheck R., McFall M. (2020). Does PTSD moderate the relationship between social support and suicide risk in Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans seeking mental health treatment? Depression and Anxiety , 27 ( 11 ), 1001–1005. 10.1002/da.20722. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jeoung B. J., Hong M. S., Lee Y.C. (2013). The relationship between mental health and health-related physical fitness of university students . Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation , 9 ( 6 ), 544–548. 10.12965/jer.130082. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kagan A., Levi L. (1971). Adaptation of the psychosocial environment to man's abilities and needs . Society, Stress and Disease , 1 , 399–404. 10.1002/da.20722. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashif M., Javed M. K., Pandey D. (2020). A surge in cyber-crime during COVID-19 . Indonesian Journal of Social and Environmental Issues , 1 ( 2 ), 48–52. 10.47540/ijsei.v1i2.22. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kobasa S. C. (1979). Personality and resistance to illness . American Journal of Community Psychology , 7 ( 4 ), 413–423. 10.1007/bf00894383. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Koenig H. G. (2010). Spirituality and mental health . International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies , 7 ( 2 ), 116–122. 10.1002/aps.239. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumar A., Nayar K. R. (2021). COVID 19 and its mental health consequences . Journal of Mental Health , 30 ( 1 ), 1–2. 10.1080/09638237.2020.1757052. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuria W. (2012). Coping with age related changes in the elderly . Available at: https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/42261 .

- LaBrie J. W., Kenney S. R., Lac A. (2010). The use of protective behavioral strategies is related to reduced risk in heavy drinking college students with poorer mental and physical health . Journal of Drug Education , 40 ( 4 ), 361–378. 10.2190/DE.40.4.c. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lakhan R., Agrawal A., Sharma M. (2020). Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress during COVID-19 Pandemic . Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice , 11 ( 4 ), 519–525. 10.1055/s-0040-1716442. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lallie H. S., Shepherd L. A., Nurse J. R., Erola A., Epiphaniou G., Maple C., Bellekens X. (2020). Cyber security in the age of COVID-19: A timeline and analysis of cyber-crime and cyber-attacks during the Pandemic. Computers & Security . arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.11929, 1–20 10.1016/j.cose.2021.102248. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lazarus R. S., Folkman S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping New York. Link: Springer Publishing Company. https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=i-ySQQuUpr8C&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&ots=DgEPjrjeLa&sig=63fQrxM63vph60T1t7U7oIwhVDw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false . [ Google Scholar ]

- Lazarus R. S., Folkman S. (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping . European Journal of Personality , 1 ( 3 ), 141–169. 10.1002/per.2410010304. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levi L., Kagan A. (1971). A synopsis of ecology and psychiatry: Some theoretical psychosomatic considerations, review of some studies and discussion of preventive aspects . Excerpta Medica International Congress Series , 274 , 369–379. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1975-27742-001 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin C. C. (2016). The roles of social support and coping style in the relationship between gratitude and well-being . Personality and Individual Differences , 89 , 13–18. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.032. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindsay E. K., Young S., Smyth J. M., Brown K. W., Creswell J. D. (2018). Acceptance lowers stress reactivity: Dismantling mindfulness training in a randomized controlled trial . Psychoneuroendocrinology , 87 , 63–73. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.09.015. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Linnabery E., Stuhlmacher A. F., Towler A. (2014). From whence cometh their strength: Social support, coping, and well-being of Black women professionals . Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology , 20 ( 4 ), 541–549. 10.1037/a0037873. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Loukzadeh Z., Mazloom Bafrooi N. (2013). Association of coping style and psychological well-being in hospital nurses . Journal of Caring Sciences , 2 ( 4 ), 313–319. 10.5681/jcs.2013.037. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maddi S. R., Kobasa S. C. (1984). The hardy executive: Health under stress : Dow Jones-Irwin. [ Google Scholar ]

- Madison A. A., Shrout M. R., Renna M. E., Kiecolt-Glaser J. K. (2021). Psychological and behavioral predictors of vaccine efficacy: Considerations for COVID-19 . Perspectives on Psychological Science , 16 ( 2 ), 191–203. 10.1177/1745691621989243. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Manna G., Foddai E., Di Maggio M., Pace F., Colucci G., Gebbia N., Russo A. (2007). Emotional expression and coping style in female breast cancer . Annals of Oncology , 18 ( 6 ), vi77–vi80. 10.1093/annonc/mdm231. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Matud M. P. (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles . Personality and Individual Differences , 37 ( 7 ), 1401–1415. 10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mayo Clinic (2020). COVID-19 and your mental health : Mayo Clinic. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/mental-health-covid-19/art-20482731 . [ Google Scholar ]

- McGregor L. S., Melvin G. A., Newman L. K. (2015). Familial Separations, Coping Styles, and PTSD Symptomatology in Resettled Refugee Youth . The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease , 203 ( 6 ), 431–438. 10.1097/nmd.0000000000000312. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McKnight-Eily L. R., Okoro C. A., Strine T. W., Verlenden J., Hollis N. D., Njai R., Mitchell E. W., Board A., Puddy R., Thomas C. (2021). Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of stress and worry, mental health conditions, and increased substance use among adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, April and May 2020 . MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report , 70 ( 5 ), 162–166. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005a3. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Melnyk B. M., Small L., Morrison-Beedy D., Strasser A., Spath L., Kreipe R., Crean H., Jacobson D., Van Blankenstein S. (2006). Mental health correlates of healthy lifestyle attitudes, beliefs, choices, and behaviors in overweight adolescents . Journal of Pediatric Health Care , 20 ( 6 ), 401–406. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.03.004. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ministry of Health and Family welfare, Government of India (2021). Novel Coronavirus (COVID19) . Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/ProtectivemeasuresEng.pdf .

- Mohindra R., Ravaki R., Suri V., Bhalla A., Singh S. M. (2020). Issues relevant to mental health promotion in frontline health care providers managing quarantined/isolated COVID19 patients . Asian Journal of Psychiatry , 51 , 102084. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102084. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Montano R. L. T., Acebes K. M. L. (2020). Covid stress predicts depression, anxiety and stress symptoms of Filipino respondents . International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147-4478) , 9 ( 4 ), 78–103. 10.20525/ijrbs.v9i4.773. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muraki S., Maehara T., Ishii K., Ajimoto M., Kikuchi K. (1993). Gender difference in the relationship between physical fitness and mental health . The Annals of Physiological Anthropology , 12 ( 6 ), 379–384. 10.2114/ahs1983.12.379. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Naseem Z., Khalid R. (2010). Positive thinking in coping with stress and health outcomes: Literature review . Journal of Research & Reflections in Education (JRRE) , 4 ( 1 ), 42–61. http://www.ue.edu.pk/jrre . [ Google Scholar ]

- Paykel E. S. (1983). Methodological aspects of life events research . Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 27 ( 5 ), 341–352. 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90065-x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearman A., Hughes M. L., Smith E. L., Neupert S. D. (2021). Age differences in risk and resilience factors in COVID-19-related stress . The Journals of Gerontology: Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 76 ( 2 ), e38–e44. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa120. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Polizzi C., Lynn S. J., Perry A. (2020). Stress and coping in the time of COVID-19: pathways to resilience and recovery . Clinical Neuropsychiatry , 17 ( 2 ), 59–62. 10.36131/CN20200204. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ptacek J. T., Smith R. E., Dodge K. L. (1994). Gender differences in coping with stress: When stressor and appraisals do not differ . Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin , 20 ( 4 ), 421–430. 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90065-x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roy D., Tripathy S., Kar S. K., Sharma N., Verma S. K., Kaushal V. (2020). Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic . Asian Journal of Psychiatry , 51 , 102083. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sahoo S., Rani S., Parveen S., Pal Singh A., Mehra A., Chakrabarti S., Grover S., Tandup C. (2020). Self-harm and COVID-19 Pandemic: An emerging concern - A report of 2 cases from India (Advance online publication) . Asian Journal of Psychiatry , 51 , 102104. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102104. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Selye H. (1956). The stress of life . McGraw-Hill Book Company. [ Google Scholar ]

- Selye H. (1991). History and present status of the stress concept In: Stress and coping: An Anthology (pp. 21–35). Columbia University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shrilatha S., Durga M. S. J. (2020). The role of social media apps and its cyber-attacks during Covid-19 lockdown at Vellore City . Purakala with ISSN 0971-2143 is an UGC CARE Journal , 31 ( 17 ), 446–461. 10.4103/IJAM.IJAM_50_20. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sinha R. (2001). How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology , 158 ( 4 ), 343–359. 10.1007/s002130100917. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sinha S., Latha G. S. (2018). Coping response to same stressors varies with gender . National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology , 8 ( 7 ), 1053–1057. 10.5455/njppp.2018.8.0206921032018. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steiner H., Erickson S. J., Hernandez N. L., Pavelski R. (2002). Coping styles as correlates of health in high school students . Journal of Adolescent Health , 30 ( 5 ), 326–335. 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00326-3. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sunder P., Prabhu A., Parameswaran U. (2020). Psychosocial interventions for COVID-19-Supporting document . e-Book On Palliative Care Guidelines For Covid-19 Pandemic , 42 , 21–24. https://wp.ufpel.edu.br/francielefrc/files/2020/04/e-book-Palliative-Care-Guidelines-for-COVID19-ver1.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Takeda F., Noguchi H., Monma T., Tamiya N. (2015). How possibly do leisure and social activities impact mental health of middle-aged adults in Japan?: an evidence from a national longitudinal survey . PLoS One , 10 ( 10 ), e0139777. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139777. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thoits P. A. (2010). Perceived social support and the voluntary, mixed, or pressured use of mental health services . Society and Mental Health , 1 ( 1 ), 4–19. 10.1177/2156869310392793. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tolor A., Fehon D. (1987). Coping with stress: A study of male adolescents' coping strategies as related to adjustment . Journal of Adolescent Research , 2 ( 1 ), 33–42. 10.1177/074355488721003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Torales J., O’Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J. M., Ventriglio A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health . International Journal of Social Psychiatry , 66 ( 4 ), 317–320. 10.1177/0020764020915212. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsaur S., Tang Y. (2012). Job stress and well-being of female employees in hospitality: The role of regulatory leisure coping styles . International Journal of Hospitality Management , 31 ( 4 ), 1038–1044. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.12.009. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Usher K., Durkin J., Bhullar N. (2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic and mental health impacts . International Journal of Mental Health Nursing , 29 ( 3 ), 315–318. 10.1111/inm.12726. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Bortel T., Basnayake A., Wurie F., Jambai M., Koroma A. S., Muana A. T., Hann K., Eaton J., Martin S., Nellums L. B. (2016). Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at Individual, Community and International levels . Bulletin of the World Health Organization , 94 ( 3 ), 210–214. 10.2471/BLT.15.158543. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Gundy K. T., Howerton-Orcutt A., Mills M. L. (2015). Race, coping style, and substance use disorder among non-hispanic African American and white young adults in South Florida . Substance Use & Misuse , 50 ( 11 ), 1459–1469. 10.3109/10826084.2015.1018544. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vieta E. (2005). Improving treatment adherence in bipolar disorder through psychoeducation . The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry , 66 ( 1 ), 24–29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15693749/ . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Y., Zhao X., Feng Q., Liu L., Yao Y., Shi J. (2020). Psychological assistance during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China . Journal of Health Psychology , 25 ( 6 ), 733–737. 10.1177/1359105320919177. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization (2020). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak, (No. WHO/2019-nCoV/Mental Health/2020.1) : World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus . [ Google Scholar ]

- Wu D., Yu L., Yang T., Cottrell R., Peng S., Guo W., Jiang S. (2020). The impacts of uncertainty stress on mental disorders of Chinese college students: Evidence from a nationwide study . Frontiers in Psychology , 11 , 243. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00243. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xiang Y. T., Yang Y., Li W., Zhang L., Zhang Q., Cheung T., Ng C. H. (2020). Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed . The Lancet Psychiatry , 7 ( 3 ), 228–229. 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30046-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xiao H., Zhang Y., Kong D., Li S., Yang N. (2020). The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China . Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research , 26 , e923549. 10.12659/MSM.923549. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yang L. H. (2007). Application of mental illness stigma theory to Chinese societies: Synthesis and new direction . Singapore Medical Journal , 48 ( 11 ), 977–985. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17975685/ . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

Adjusting to the new normal: Is COVID-19 ever going to end?

Jump to section

What is the new normal?

What does the new normal look like.

4 impacts of the new normal

How are different generations responding to the new normal?

5 ways to adjust to the new normal

It’s almost two years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Had you told me in March 2020 that COVID-19 would still be around in 2022, I’m not sure I would’ve believed you. But as we all know, living in the age of COVID-19 has become our “new normal.” In a recently released JAMA article, scientists say COVID-19 is here to stay . Much like the flu, it’s anticipated COVID-19 will be endemic.

So, what is the “new normal” as we head into 2022?

While everyone is unique, we all want to live safe, healthy, and fulfilling lives . The truth is we’re remaining flexible and learning as we go. We’re defining (and redefining) what the new normal looks like for our global society, each step of the way.

As you continue your journey to build mental fitness in the face of uncertainty , take these considerations into mind.

A new normal is a state where our global economy and society have settled since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The new normal is evolving as our world adjusts to COVID-19.

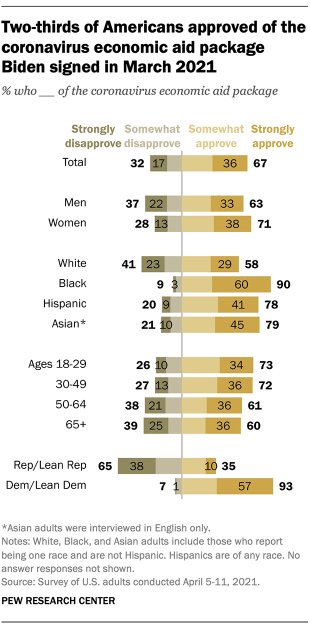

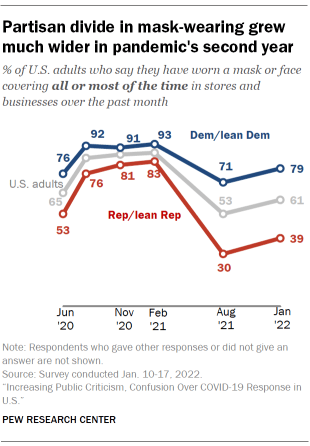

We know we’re not going back to life as we know it in 2019. And that’s OK. According to Pew Research, 91% of Americans say coronavirus has changed their lives . As a global society, we’ve suffered grief, loss, and collective trauma . We’ve experienced lockdowns with massive impacts on the economy and jobs. We’re living with the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on our mental health. We’re navigating uncertainty and the unknown. But we’re resilient. And with change comes opportunity . Together, we’re redefining what “the new normal” looks like for our world.

Every person is unique. There’s not necessarily a one-size-fits-all “new normal” for society. But when we think about our day-to-day lives, there’s a good chance you notice these themes.

Social interactions

If we’re being honest, social interactions could already be awkward pre-pandemic. But with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the new normal has brought on a new set of rules with social interactions. Let’s say you run into an old friend in the grocery store. You haven’t seen this friend in a couple of years. Do you go up and give them a hug? Do you pull down your mask so you’re easily recognizable in the store? Do you keep your distance and wave from six feet? One study looked at the impact of COVID-19 and face masks on our social interactions. Scientists found that we’re less likely to be able to read nonverbal body language , like facial expressions. This impedes our ability to evaluate emotions, which has a drastic impact on how we interact. Paired with social distancing, it impedes how we would typically communicate pre-pandemic.