- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Barriers and Gateways to Communication

- Carl R. Rogers

- F. J. Roethlisberger

This article originally appeared in HBR July–August 1952. Part I: Carl R. Rogers It may seem curious that someone like me, a psychotherapist, should be interested in problems of communication. But, in fact, the whole task of psychotherapy is to deal with a failure in communication. In emotionally maladjusted people, communication within themselves has broken […]

Part I: Carl R. Rogers

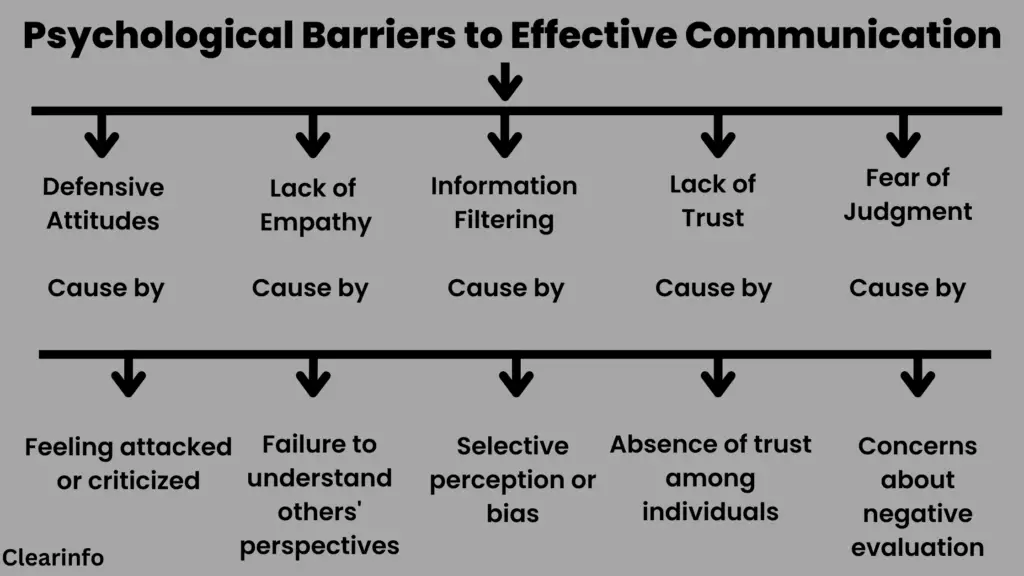

It may seem curious that someone like me, a psychotherapist, should be interested in problems of communication. But, in fact, the whole task of psychotherapy is to deal with a failure in communication. In emotionally maladjusted people, communication within themselves has broken down, and as a result, their communication with others has been damaged. To put it another way, their unconscious, repressed, or denied desires have created distortions in the way they communicate with others. Thus they suffer both within themselves and in their interpersonal relationships.

- CR The late Carl R. Rogers was a professor of psychology at the University of Chicago when he wrote this article. His many books include the groundbreaking Client-Centered Therapy (Houghton Mifflin, 1951).

- FR The late F.J. Roethlisberger was the Wallace Brett Donham Professor of Human Relations at the Harvard Business School. He is the author of Man-in-Organization (Harvard University Press, 1968) and other books and articles.

Partner Center

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 11 February 2019

A qualitative assessment of perceived barriers to effective therapeutic communication among nurses and patients

- Vida Maame Kissiwaa Amoah 2 ,

- Reindolf Anokye ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7669-7057 1 ,

- Dorothy Serwaa Boakye 2 ,

- Enoch Acheampong 1 ,

- Amy Budu-Ainooson 3 ,

- Emelia Okyere 2 ,

- Gifty Kumi-Boateng 2 ,

- Cynthia Yeboah 2 &

- Jennifer Owusu Afriyie 2

BMC Nursing volume 18 , Article number: 4 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

133k Accesses

39 Citations

Metrics details

Therapeutic communication is essential in the provision of quality healthcare to patients. The purpose of this study was to explore the perceived barriers to effective therapeutic communication among patients and nurses at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital,Kumasi.

An exploratory study design was employed using a qualitative approach. A purposive sampling technique was used to select 13 nurses and patients who were interviewed using an unstructured interview guide. Interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic content analysis.

Patient-related characteristics that were identified as barriers to effective therapeutic communication included socio-demographic characteristics, patient-nurse relationship, language, misconception, as well as pain. Nurse-related characteristics such as lack of knowledge, all-knowing attitude, work overload and dissatisfaction were also identified as barriers to effective therapeutic and environmental-related issues such as noisy environment, new to the hospital environment as well as unconducive environment were identified as barriers to effective therapeutic communication among patients and nurses at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital,Kumasi.

Nurse-patient communication is an inseparable part of the patients’ care in every health setting; it is one of the factors that determine the quality of care. Several patient-related characteristics, nurse- related characteristics and environmental-related issues pose as barriers to effective therapeutic communication at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital,Kumasi and have ultimately; resulted in reducing effective communication at the wards. Therefore, all the barriers must be eradicated to promote effective therapeutic communication.

Peer Review reports

Therapeutic communication is essential in the provision of quality healthcare to patients. According to the American Nurses Association [ 1 ], nurses serve the role as patient advocates and must, therefore, preserve a therapeutic and professional nurse-patient relationship in their professional role with specific boundaries to their role. This makes it necessary that nurses adopt techniques in interacting with patients within the clinical setting which is an important part of their work in the provision of healthcare to patients.

Therapeutic communication involves a direct face to face contact with patients that focus on enhancing the physical and emotional well-being of patients [ 2 ]. A variety of techniques are used by nurses in communicating with patients. In therapeutic communication, there is a verbal and non-verbal flow of information between nurses and patients [ 3 ]. The verbal aspect of communication employs the use of words whilst non-verbal communication makes use of non-verbal cues such as eye contact, body language, and facial expression [ 3 ].

Bournes and Mitchell [ 4 ] state, “Health is the way people go on and live what is important to them, moment to moment and day to day”. The recognition of effective therapeutic communication as a critical part of healthcare provision has been highlighted in several studies [ 5 ]. Therapeutic communication has the potency of increasing patients’ knowledge and understanding, enhancing trust and self-health skills, increase adherence, providing comfort and facilitating the management of emotions key to patients’ health and well-being [ 2 ]. Again, it has been well documented in several studies that medical practice is affected with the quality of communication between patients and clinicians as more medical errors occur with less effective communication within the clinical setting [ 6 , 7 ].

Nevertheless, several factors such as the environment/surroundings, circumstances and timing affect the restorative and soothing facets of patients that give significance to therapeutic communication [ 8 ]. For instance, in emergency cases where there will be little time for verbal interaction, the use of non-verbal cues such as the holding of hand could carry much more words to patients [ 8 ]. Even in cases where nurses are much experienced in therapeutic communication, there can still be a gap in communication as sometimes it becomes difficult to understand patients from their own viewpoints [ 8 ].

Therefore, this study sought to investigate the barriers to effective therapeutic communication among patients and nurses at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi.

Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) is a tertiary health facility premise in the environs of Kumasi within the Ashanti Region and ranked as the second largest hospital in Ghana. Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) has a bed capacity of about 1000 with twelve (12) clinical directorates providing healthcare services to the people within the region as well as handling referrals from other closer regions.

Study design

The study employed an exploratory based design which followed a qualitative approach to investigate Nurses’ and Patients’ experiences and views on the barriers to effective therapeutic communication to serve as a springboard for further studies.

Study population

The study population included patients and nurses at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital.

Inclusion criteria

Participants included in the study were individuals who had been admitted for a minimum of 3 to 4 days. This meant that participants would have communicated regularly with the nurses during their stay. Registered nurses employed full-time and having worked for four months or more at KATH were also included.

Exclusion criteria

Unconscious and patients who had not been on admission for up to a minimum of 3 days were excluded from the study. Nurses who were not full time and had not worked for more than 4 months were also excluded.

Techniques, instruments for data collection and analysis

An in-depth interview guide was used as the data collection instrument to gather in-depth information from participants. The interview guide allowed the researcher to probe further in order to understand and explore participant contributions in as much depth as possible. An unstructured interview guide which followed an open-ended approach permitted the in-depth investigation of experiences and views regarding nurse-patient communication. The interview guide contained interview questions on the demographic profile of nurses and patients as well as interview questions on Nurse-related barriers; Patient-related barriers and Environmental-related barriers to Therapeutic Communication.

The interview days and time were discussed with participants and each interview was scheduled at their convenience. Interviews were then audio-taped so that participants’ responses could later be transcribed verbatim. The researcher used two weeks for data collection (3rd March to 17th March 2016) with each interview lasting approximately 45 to 60 min. The collection of data was done by two of the authors (sixth and seventh authors) and assisted by two (2) research assistants. Participants were informed about the time before commencement. The data collected was then transcribed verbatim and analyzed through thematic content analysis. This was done by listening to tape recordings and transcribing the content. The transcript was coded by going through the transcript line by line and paragraph by paragraph, to find significant statements and codes according to the topics addressed. The similarities and contrast within the data were compared by the investigators and data that seemed to cluster together were sorted into categories.

Sampling and sampling techniques

The participants were purposively selected to participate in the study based on the characteristics they exhibited which were of interest to the researchers and were able to provide the needed information. According to Patton [ 9 ], the logic and power of purposeful sampling lie in selecting information-rich cases for in-depth study. A sample of 13 participants was used for the study which was made up of 6 nurses and 7 patients. The interviews were conducted till a saturation point was reached after interviewing the 13th participant. Saturation refers to the point at which new data collected and analyzed does not provide further meaning to the research question [ 10 ].

Validity and reliability

To ensure rigour, or the integrity in which the study was conducted, and ensure the credibility of findings in relation to qualitative research, several steps were taken to enhance the validity and reliability of the study [ 11 ].

Firstly, comparisons were done to find out similarities and differences across accounts to ensure that all different perspectives were represented.

Also, active and continuous reflection was done by the researcher during the interpretation of data to ensure the quality of the data and to mirror participants’ experiences to add credibility to the study. The context of the research and assumptions central to the study were thoroughly described to achieve transferability. The criteria applied were made explicit, according to the purpose and orientation of the study [ 12 ].

Furthermore, other researchers were engaged to reduce research bias and the researchers and supervisor again ensured that the findings, conclusions, and recommendations were braced by the data collected and that the interpretation of the data was meaningful and relevant to the study.

Limitations of the study

The study was conducted at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital which is a single facility and therefore the findings cannot be generalized. Some of the participants were not willing to respond to some of the interview questions due to its sensitive nature. However, these limitations did not influence the findings of this study in any negative way.

Thematic content analysis was used to analyze data collected based on the aims of the study. The results included background characteristics of study participants as well as the main and sub-themes of the study. Three main themes were derived from the data collected. The themes included; patient-related barriers with sub-themes personal/ social characteristics; patient-nurse relationship; language barriers as well as misconception and pain. The nurse related barriers came with sub-themes such as availability of nurses; inadequate knowledge; all-knowing attitude; dissatisfaction as well as the disease state and family interference. The environmental barriers included sub-themes such as noisy environment; new to the hospital environment and unconducive environment.

Background characteristics of study participants

Table 1 shows the background characteristics of the study participants.From the table,five (5) of the study participants were females whiles eight (8) were males. The participants were between the ages of 20 and 50 years and most of them were between the ages of 20 and 30 years. Moreover, six of the participants were married and seven were single. Most of the patient participants have attained their tertiary education while most of the nurses have attained their degree in nursing.

Main findings

Patient-related barriers.

Patient-related barriers are those obstacles directly from patients that inhibit effective therapeutic communication. Sub-themes that emerged are personal/social characteristics, patient-nurse relationship, language barriers, misconception, and pain.

Personal / social characteristics

These included characteristics such as age, religion, ethnicity among others that have the tendency of influencing communication .

One Participant revealed that;

Once they age, conditions such as dementia sets in and this causes their level of interpretation and understanding to go down and it becomes difficult communicating with them. Those at the extremes of age will have difficulty as compared to those who are in their middle ages. Sometimes the younger ones act like they understand what we tell them and they are okay but in actual sense, they do not understand (Participant 2).

One nurse also reported that religious beliefs and culture play a key role;

Some patients are Muslims and would not want females to attend to them but they prefer males. People from different parts of Ghana have different cultures thus, culture and religion, patient status, all do count to add up to the personal barriers. There are also patients who would say no to blood but as a nurse, you have to use your discretion and this can alter effective communication between you and the patient (Participant 13).

A greater number of the nurses admitted that the cultural background of patients affected their communications. One echoed;

Sometimes the culture of some people will require you to bow whenever you attend to or meet them but as a nurse, you work with limited time and therefore cannot be bowing to everyone you meet and this may portray you the nurse as been insolent thus, affecting the level of communication (Participant 11).

Patient-nurse relationship

Patient-Nurse Relationship is essential for effective healthcare delivery. In this study, patients complained about their relationship with the nurses and the way the nurses attend to them when they are in need. The nurses also admitted that the kind of relationship between the client and them also influences the level of effective communication.

One patient admitted that;

Our relationship is okay but I think their swiftness is a little questionable, they sit always but I think maybe it’s because they are busy but for me, their swiftness is not too good just not too good (Participant 1).

Misconception

Misconceptions can distort effective communication. One individual may perceive another to be of a certain trait, character or of a certain attitude.

Patient revealed that;

I think we come with preconceived ideas because of what we hear about the nurses (Participant 2).

Some of us have misconceptions about nurses that they are rude and disrespectful so we already have something in mind before coming to the ward (Participant 3).

Pain is one thing that can change one’s mood and influence his/her behaviour. Participants verbalized how pain act as a barrier to effective therapeutic communication;

Sometimes I don’t blame the patients, because the pain is too much for them to bear, they wouldn’t want to engage themselves in the conversation going on. In fact, whiles you are in pains and someone tries to even communicate with you, you sometimes get angry (Participant 2).

Another participant had this to say:

Because of the fact that the person is suffering and going through a lot when they call the nurses for one or two times and we don’t attend to them they lose their temper and begin to alter insults (Participant 5).

Language can act as a barrier to any form of communication and effective therapeutic communication is not an exception. Some of the patients complained that nurses mostly resorted to the Twi language when most of the patients have difficulties in understanding Twi.

I am a Voltarian and would like the nurses to speak English because I do not understand Twi but they always speak Twi. They should speak in languages that we will understand and I know every nurse can speak English so I do not know why they normally prefer to speak Twi whiles they know some of us cannot speak Twi well (Participant 3).

There was a patient here who was a northerner and could not communicate so whenever he needed something he had to wait for his relatives to come so that he will communicate his needs through them to the nurses (Participant 7).

Ghana is an Anglophone speaking country and most residents don’t speak French. Therefore, if a patient cannot speak English, it will be difficult communicating. Occasionally, foreigners who speak French and other languages and are living in Ghana visit the Hospital. Majority of the nurses commented on how language was a problem to effective therapeutic communication. Nurses complained of having patients from different tribes and countries which makes it difficult for them to communicate effectively.

There are people admitted here who speak French and as for me, I have never spoken French before so it makes it difficult for me to communicate with them. Also, because KATH is a referral point for many hospitals and clinics we admit people from mostly Nigeria and China and its quite difficult talking to those who cannot speak English, sometimes we have to resort to sign language and even that we are not good in it. There was an occassion when we had a patient from Upper West who couldn’t speak Twi so we had to resort to sign language (Participant 12).

Nurse-related barriers

This category includes barriers related to attributes of the nurse. These attributes can be barriers in establishing a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship in the hospital. Six sub-themes emerged from it and they are inadequate knowledge, disease state, availability of nurses, all-knowing attitude, family interference, and dissatisfaction.

Availability of nurses

The Nurses complained that due to the small number of nurses and the workload it becomes difficult attending to all patients as and when they call.

One Nurse revealed;

Workload has been a factor, when nurses have a lot of work to do they will not have time to explain things to patients they will tell the patient ‘don’t you know I am very busy, don’t you know I am overburden’ especially with women whose threshold of managing stress is low as compared to men so that is a point (Participant 11). Ooh! because there are few nurses at the ward sometimes you would want a nurse to attend to you but he or she might be working on another patient so in such case the nurse cannot divide him or herself into two to attend to you both. So you have to wait for quite some time and at times due to stress they end up forgetting that you called them (Participant10).

A patient stressed that;

One thing is that the nurses that are taking care of us are very few. So most at times the nurses here, lets say patients are 31 and only 4 nurses are taking care of us. Anytime you call the nurse, she will be busy doing something else and will tell you that she will be back soon. And as a human being, you can forget about things so easily. So as the nurse is attending to a sick patient, she may also come to your direction and another sick person will also call the nurse so hardly do we communicate with them as often. They are always busy (Participant 6).

Another Nurse commented;

Because there are few nurses at the ward, sometimes you would like a nurse to attend to you but he/she might be working on another patient (Participant 13).

Inadequate knowledge

Most nurses admitted and verbalized that, some nurses had little knowledge on how to communicate with others. Lack of knowledge on therapeutic communication on the part of some nurses also contributed to ineffective therapeutic communication. If there is a close relationship between the patient and the nurse, a patient can speak out all their problems to the nurse.

One of the Nurses echoed;

I will say ignorance or nurse is not well abreast of what effective therapeutic communication is. A nurse who knows what effective therapeutic communication is will use it, especially if the nurse knows what it does to the healing process (Participant 10).

All-knowing attitude

Attitude refers to the predisposition to behave in a certain manner. Majority of the nurses verbalized that because some of the patients have stayed at the ward for a long time and in an era where most patients are educated, they think they know more about the nursing procedures and thus, do not adhere to whatever their health care provider says.

The nurses revealed;

Patients who are learned tend to give a lot of instructions when performing any procedures on them. For example, when they are allergic to pethidine injection they assume every injection you give them is pethidine and will start complaining, this makes communication difficult (Participant 12).

You see when the patients stay on the ward for a very long time, they begin to act that they know everything you do for them. So for instance, when you are dressing their wounds, they go like do this do that trying to dictate or tell you what to do and if you resist they will claim you are all-knowing (Participant 11).

Dissatisfaction

When one is not pleased with a service provider or a process, it may distort effective communication between the individual and another person. Most of the nurses identified dissatisfaction with services provided by nurses as the predominant barrier to effective communication.

I would not say so; I wouldn’t say they are satisfied. Even when you get the time to talk to them the duration of the conversation is usually minimal okay, because of the work overload and the number of nurses to attend to patients you won’t get the time to communicate with our patients. But sometimes we do try but I will say that it is not the best (Participant 10).

Another echoed;

In terms of the level of satisfaction of patients, it may vary from one patient to another. Generally, I will give them 40% because I think they are not satisfied since we don’t explain things thoroughly to them. We don’t normally explain the condition and even the adverse effect of their drugs to them. All these things must be done by us and are not effectively done (Participant 11).

Disease state

All nurses verbalized that, the disease state and mental status of patients also affect the level of communication between nurses and patients.

One of the Nurses’ commented;

When the patient is unconscious or just returned from surgery, it becomes difficult communicating with them and this can also reduce the quality of care provided to them (Participant 1) .

Another Nurse also added;

Currently we have a mental disoriented patient on the ward and in this case, communicating with such a patient is a problem which also leads to ineffective therapeutic communication (Participant 9).

Family interference

A family may interfere in a service process in order to influence outcomes. Another problem that the nurses admitted to facing is family interference in most of the procedures at the ward. Also, the kind of behaviour exhibited by clients’ families also affects how they communicate with them.

A Nurse said;

Sometimes the patient may be very sick and may not need any relatives to be there, they need some rest and when you want to restrict them (relatives) there is trouble. Some want to even dictate to you. They want to plan with you how to care for their relatives. In fact, some of the family members are troublesome (Participant 8).

Another added:

There are some instances where nurses or doctors will give them (relatives) an order; the relatives will rather give the patient drugs from a spiritualist or a herbalist which may lead to contradiction of information which resulting to ineffective therapeutic communication (Participant 13).

Environmental barriers

Environmental barriers are obstacles within the environment that inhibit effective therapeutic communication. Almost all nurses and some of the patients asserted that environmental barriers influence therapeutic communication at the ward. Most of the patients expressed how they felt when things they didn’t expect emerged.

Sub-themes that emerged were a noisy environment, new to the hospital environment smell, work overload, mosquitoes, and unconducive environment.

New to the hospital environment

Adapting to a new environment can be problematic for some people at times, therefore, influencing their ability to communicate effectively.

One Nurse stated;

You see some of the patients are new to the hospital environment and the mere fact that he or she is in the hospital makes them feel that they are really sick and can’t even communicate with the nurses. They are also already anxious the moment they get to the hospital. This alone can delay therapeutic communication (Participant 11).

Noisy environment

Noise can affect any form of communication and in this case therapeutic communication.

The issue of noise is reflected in the following;

Yeah, some patients put on their radio, some talk on top of their voices and even the nurses chat too much especially, when you call them and they are chatting they do not attend to or mind you because they are concentrating on their talking (Participant 9).

Unconducive environment

Communication can be effective only in an environment that is conducive enough for everyone. Participants shared their views on how unconducive the hospital environment is for effective communication. One participant had this to say;

The mosquitoes disturb us because there are no mosquito nets etc. here at night so when you manage to sleep through your own ways and means and the nurses wake us up because time is due for our medications, it becomes a challenge and we need to exercise patience so not to fight or get angry with the nurses that are at the ward (Participant 5).

The hospital settings itself is also a barrier. The fact that sometimes the environment is not conducive enough, it may be too warm or cold. Sometimes the patient will tell you that they don’t like the fan whiles others will say that they don’t like the light (Participant 13).

Discussions

The study explored the barriers to effective therapeutic communication among patients and nurses in Kumasi. The barriers that were explored include nurses related, patient-related, and environment-related barriers. A key demographic characteristic of patients that were identified as a barrier was age. Similarly, Payne et al., [ 13 ], reported that age can serve as a barrier to effective communication. This implies that conditions such as dementia that may set in once you age and causes the level of interpretation and understanding to go down makes it difficult to communicate effectively. Religion was also identified as a barrier as patients who were Muslims would not want females to attend to them but preferred males. People from different parts of Ghana have different cultures and thus patient status, culture, and religion are key barriers to effective therapeutic communication. This implies that religion, age as well as culture has a tendency to influence therapeutic communication. There may be cases where both may belong to the same ethnic group, however, different social orientations and circumstances may affect their communication. Payne et al., [ 13 ], also found generational gaps between the elderly and young nurses as key barriers to effective communication. However, culture and ethnic group were not mentioned by Payne et al., [ 13 ], but reported by Anderson et al., [ 14 ] who emphasized that nurses in interacting with patients from different backgrounds should be sensitive, effective and attach professional attitude.

Language was also identified as a barrier to effective therapeutic communication in this study. Similarly, Quesada [ 15 ] reported that in general, the majority of the nurses and patients report that language barrier is an impediment to quality care. The findings corroborate with this study results where patients complained that nurses mostly resort to the Twi language when some of the patients had difficulties in communicating in Twi. Nurses also complained of having patients from different tribes and countries which also makes it difficult for them to communicate effectively.

This study reports that patients complained that they feel like they have been neglected by nurses because they do not promptly attend to them while nurses also complained that, due to the small number of nurses and the workload it becomes difficult attending to all patients as and at when they call. This gives credence to the findings that heavy work schedules of nurses, tough and intensive nursing tasks and the absence of welfare facilities for nurses obstruct communication as reported by Anoosheh et al., [ 16 ].

This study reported that several patients complain about their relationship with the nurses and lack of attention. Teutsch [ 17 ], reported that nurses undivided attention for patients as they listen to them and observe them gives patients a high level of satisfaction. Interactions with patients therefore eliminate scary thoughts, doubts, and misinterpretations. The researchers do believe that if there is a close relationship between the patient and the nurse, the patient can voice out all their problems to the nurse.

Loghmani, Borhani, and Abbaszadeh [ 18 ] in their studies came to the conclusion that nurse-patient communication is declining due to family interference. This gives credence to this current study reporting that family interference is a barrier to effective therapeutic communication. Most of the patients were dissatisfied due to inattention on the part of the nurses and this was a predominant barrier to effective communication in this study. In a similar study, the majority of patients that recounted their experiences on nursing care felt dissatisfied due to neglect [ 19 ]. According to McQueen [ 20 ], patients in a healthcare facility require information,education, encouragement and support, and nurses are in an ideal position to meet this need.

Conclusions

Nurse-patient communication is an inseparable part of the patients’ care in every health setting; it is one of the factors that determine the quality of care. However, the results of this study have shown that several factors, which are patient-related, nurse- related and environmental-related pose as barriers to effective therapeutic communication and has ultimately, resulted in reducing effective communication which could affect the quality and comprehensive care delivery at the hospital wards. Authorities at the hospital must ensure that all barriers are eradicated to promote effective therapeutic communication.

Abbreviations

Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital

American Nurses Association. Correctional nursing scope and standards of practice. Silver Sping: MD: American Nurses Association; 2013.

Google Scholar

Richard L.S, Gregory M., Neeraj K.A., Ronald M.E. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns Elsevier, 2009: 74(295–301).

Sherko E, Sotiri E, Lika E. Therapeutic communication. JAHR. 2013;4(7):457–66.

Bournes DA, Mitchell GJ. Waiting: the experience of persons in a critical care waiting room. Research in nursing & health. 2002;25(1):58–67.

Article Google Scholar

McGilton K, Robinson HI, Boscart V, Spanjevic L. Communication enhancement: nurse and patient satisfaction outcomes in a complex continuing care facility. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(1):35–44.

Swasey, M. L. Physician, and Patient Communication: A Grounded Theory Analysis of Physician and Patient Web-Logs (doctoral dissertation, southern Utah University. Department of Communication 2013.

Alvarez G, Coiera E. Interdisciplinary communication: an uncharted source of medical error? J Crit Care. 2006;21(3):236–42.

Montgomery CL. Healing through communication: the practice of caring: Sage; 1993.

Patton, M. Q. Qual Res & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). Thousand oaks, CA: Sage, 2015.

Mack N, Woodsong C, MacQueen KM, Guest G, Namey E. Qualitative research methods: a data collector’s field guide; 2005.

Noble H, Smith J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence-Based Nursing 2015:ebnurs-2015.

Patton, M. Q. Qualitative research John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2005.

Payne S, Kerr C, Hawker S, Hardey M, Powell J. The communication of information about older people between health and social care practitioners. Age and aging. 2002;31(2):107–17.

Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Normand J. Culturally competent healthcare systems: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3):68–79.

Quesada GM. Language and communication barriers for health delivery to a minority group. Soc Sci Med. 1967;10(6):323–7.

Anoosheh M, Zarkhah S, Faghihzadeh S, Vaismoradi M. Nurse-patient communication barriers in Iranian nursing. Int Nurs Rev. 2009;56(2):243–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Teutsch C. Patient-doctor communication. Med Clin N Am. 2003;87(5):1115–45.

Loghmani L, Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A. Factors affecting the nurse-patient' family communication in intensive care unit of Kerman: a qualitative study. J Caring Sci. 2014;3(1):67.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rauseo MM. Effective communication in nursing: is it necessary to know your own sociological Bias? 2016.

McQueen A. Nurse-patient relationships, and partnership in hospital care. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9(5):723–31.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes out to the management and staff of Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi as well as all patients and nurses who took part in this study. Further thanks to all whose works on therapeutic communication helped in putting this work together.

There were no external grants received for the conduction of this study. Researchers of this study bear all expenses related to the study.

Availability of data and materials

The whole document, data, materials, and results of this work are available at the Library of the Garden City University College, Kumasi. If someone wants to request the data the corresponding author should be contacted.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Disability and Rehabilitation Studies, Department of Community Health, School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Reindolf Anokye & Enoch Acheampong

Department of Nursing, Garden City University College, Kumasi, Ghana

Vida Maame Kissiwaa Amoah, Dorothy Serwaa Boakye, Emelia Okyere, Gifty Kumi-Boateng, Cynthia Yeboah & Jennifer Owusu Afriyie

School of Public Health, Department of Health Education and Promotion, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Amy Budu-Ainooson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The collection of data was done by sixth and seventh authors (EO and GKB). The secondary data compilation, data analysis, and interpretation were done by the second author (RA). The first and third authors (VMKA and EA) in their individual capacities reviewed the manuscript thoroughly. Authors DSB, ABA, CY and JOA played a significant role during data collection, data analysis, and interpretation. All authors contributed to the designing, preparation of manuscripts, the analysis of the data, proofreading and the final approval process of the manuscript. The authors all approved the submission of this manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Reindolf Anokye .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics (CHRPE) at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). The participants were reassured that information taking will be confidential. Participation was voluntary and participants were informed of their right to pull out of the study at any point of the research which was not going to affect the care they were receiving. Written consent was obtained from participants before they participated in the study. The study was well explained to the participants and also the recording tape was locked to prevent other people from getting access to it. All the participants were given pseudonyms to protect their anonymity. All authors have agreed to the submission of this manuscript for publication.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Amoah, V.M.K., Anokye, R., Boakye, D.S. et al. A qualitative assessment of perceived barriers to effective therapeutic communication among nurses and patients. BMC Nurs 18 , 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0328-0

Download citation

Received : 25 April 2018

Accepted : 28 January 2019

Published : 11 February 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0328-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Therapeutic communication

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Communication →

- 22 May 2024

Banned or Not, TikTok Is a Force Companies Can’t Afford to Ignore

It may be tempting to write off TikTok, the highly scrutinized social media app whose cat clips and dance videos propelled it to the mainstream. However, business leaders could learn valuable lessons about engaging consumers from the world's most-used platform, says Shikhar Ghosh in a case study.

- 15 May 2024

- Research & Ideas

A Major Roadblock for Autonomous Cars: Motorists Believe They Drive Better

With all the advances in autonomous vehicle technology, why aren't self-driving cars chauffeuring more people around? Research by Julian De Freitas, Stuti Agarwal, and colleagues reveals a simple psychological barrier: Drivers are overconfident about their own abilities, so they resist handing over the wheel.

- 09 May 2024

Called Back to the Office? How You Benefit from Ideas You Didn't Know You Were Missing

As companies continue to weigh the benefits and drawbacks of remote work, a study of how knowledge flows among academic researchers by Karim Lakhani, Eamon Duede, and colleagues offers lessons for hybrid workplaces. Does in-person work provide more opportunities for innovation than people realize?

- 06 May 2024

The Critical Minutes After a Virtual Meeting That Can Build Up or Tear Down Teams

Weak communication and misunderstandings during virtual meetings can give way to resentment and rifts when the cameras turn off. Research by Leslie Perlow probes the nuances of digital communication. She offers advice for improving remote teamwork.

- 16 Feb 2024

Is Your Workplace Biased Against Introverts?

Extroverts are more likely to express their passion outwardly, giving them a leg up when it comes to raises and promotions, according to research by Jon Jachimowicz. Introverts are just as motivated and excited about their work, but show it differently. How can managers challenge their assumptions?

- 06 Nov 2023

Did You Hear What I Said? How to Listen Better

People who seem like they're paying attention often aren't—even when they're smiling and nodding toward the speaker. Research by Alison Wood Brooks, Hanne Collins, and colleagues reveals just how prone the mind is to wandering, and sheds light on ways to stay tuned in to the conversation.

.jpg)

- 31 Oct 2023

Checking Your Ethics: Would You Speak Up in These 3 Sticky Situations?

Would you complain about a client who verbally abuses their staff? Would you admit to cutting corners on your work? The answers aren't always clear, says David Fubini, who tackles tricky scenarios in a series of case studies and offers his advice from the field.

- 24 Jul 2023

Part-Time Employees Want More Hours. Can Companies Tap This ‘Hidden’ Talent Pool?

Businesses need more staff and employees need more work, so what's standing in the way? A report by Joseph Fuller and colleagues shows how algorithms and inflexibility prevent companies from accessing valuable talent in a long-term shortage.

- 23 Jun 2023

This Company Lets Employees Take Charge—Even with Life and Death Decisions

Dutch home health care organization Buurtzorg avoids middle management positions and instead empowers its nurses to care for patients as they see fit. Tatiana Sandino and Ethan Bernstein explore how removing organizational layers and allowing employees to make decisions can boost performance.

- 24 Jan 2023

Passion at Work Is a Good Thing—But Only If Bosses Know How to Manage It

Does showing passion mean doing whatever it takes to get the job done? Employees and managers often disagree, says research by Jon Jachimowicz. He offers four pieces of advice for leaders who yearn for more spirit and intensity at their companies.

- 10 Jan 2023

How to Live Happier in 2023: Diversify Your Social Circle

People need all kinds of relationships to thrive: partners, acquaintances, colleagues, and family. Research by Michael Norton and Alison Wood Brooks offers new reasons to pick up the phone and reconnect with that old friend from home.

- 15 Nov 2022

Why TikTok Is Beating YouTube for Eyeball Time (It’s Not Just the Dance Videos)

Quirky amateur video clips might draw people to TikTok, but its algorithm keeps them watching. John Deighton and Leora Kornfeld explore the factors that helped propel TikTok ahead of established social platforms, and where it might go next.

- 03 Nov 2022

Feeling Separation Anxiety at Your Startup? 5 Tips to Soothe These Growing Pains

As startups mature and introduce more managers, early employees may lose the easy closeness they once had with founders. However, with transparency and healthy boundaries, entrepreneurs can help employees weather this transition and build trust, says Julia Austin.

- 15 Sep 2022

Looking For a Job? Some LinkedIn Connections Matter More Than Others

Debating whether to connect on LinkedIn with that more senior executive you met at that conference? You should, says new research about professional networks by Iavor Bojinov and colleagues. That person just might help you land your next job.

- 08 Sep 2022

Gen Xers and Millennials, It’s Time To Lead. Are You Ready?

Generation X and Millennials—eagerly waiting to succeed Baby Boom leaders—have the opportunity to bring more collaboration and purpose to business. In the book True North: Emerging Leader Edition, Bill George offers advice for the next wave of CEOs.

- 05 Aug 2022

Why People Crave Feedback—and Why We’re Afraid to Give It

How am I doing? Research by Francesca Gino and colleagues shows just how badly employees want to know. Is it time for managers to get over their discomfort and get the conversation going at work?

- 23 Jun 2022

All Those Zoom Meetings May Boost Connection and Curb Loneliness

Zoom fatigue became a thing during the height of the pandemic, but research by Amit Goldenberg shows how virtual interactions can provide a salve for isolation. What does this mean for remote and hybrid workplaces?

- 13 Jun 2022

Extroverts, Your Colleagues Wish You Would Just Shut Up and Listen

Extroverts may be the life of the party, but at work, they're often viewed as phony and self-centered, says research by Julian Zlatev and colleagues. Here's how extroverts can show others that they're listening, without muting themselves.

- 24 May 2022

Career Advice for Minorities and Women: Sharing Your Identity Can Open Doors

Women and people of color tend to minimize their identities in professional situations, but highlighting who they are often forces others to check their own biases. Research by Edward Chang and colleagues.

- 12 May 2022

Why Digital Is a State of Mind, Not Just a Skill Set

You don't have to be a machine learning expert to manage a successful digital transformation. In fact, you only need 30 percent fluency in a handful of technical topics, say Tsedal Neeley and Paul Leonardi in their book, The Digital Mindset.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 24 March 2021

Exploring the barriers and facilitators of psychological safety in primary care teams: a qualitative study

- Ridhaa Remtulla ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4037-8959 1 na1 ,

- Arwa Hagana 2 na1 ,

- Nour Houbby 2 na1 ,

- Kajal Ruparell 2 na1 ,

- Nivaran Aojula 2 ,

- Anannya Menon 2 ,

- Santhosh G. Thavarajasingam 2 &

- Edgar Meyer 3

BMC Health Services Research volume 21 , Article number: 269 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

21 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Psychological safety is the concept by which individuals feel comfortable expressing themselves in a work environment, without fear of embarrassment or criticism from others. Psychological safety in healthcare is associated with improved patient safety outcomes, enhanced physician engagement and fostering a creative learning environment. Therefore, it is important to establish the key levers which can act as facilitators or barriers to establishing psychological safety. Existing literature on psychological safety in healthcare teams has focused on secondary care, primarily from an individual profession perspective. In light of the increased focus on multidisciplinary work in primary care and the need for team-based studies, given that psychological safety is a team-based construct, this study sought to investigate the facilitators and barriers to psychological safety in primary care multidisciplinary teams.

A mono-method qualitative research design was chosen for this study. Healthcare professionals from four primary care teams ( n = 20) were recruited using snowball sampling. Data collection was through semi-structured interviews. Thematic analysis was used to generate findings.

Three meta themes surfaced: shared beliefs, facilitators and barriers to psychological safety. The shared beliefs offered insights into the teams’ background functioning, providing important context to the facilitators and barriers of psychological safety specific to each team. Four barriers to psychological safety were identified: hierarchy, perceived lack of knowledge, personality and authoritarian leadership. Eight facilitators surfaced: leader and leader inclusiveness, open culture, vocal personality, support in silos, boundary spanner, chairing meetings, strong interpersonal relationships and small groups.

This study emphasises that factors influencing psychological safety can be individualistic, team-based or organisational. Although previous literature has largely focused on the role of leaders in promoting psychological safety, safe environments can be created by all team members. Members can facilitate psychological safety in instances where positive leadership behaviours are lacking - for example, strengthening interpersonal relationships, finding support in silos or rotating the chairperson in team meetings. It is anticipated that these findings will encourage practices to reflect on their team dynamics and adopt strategies to ensure every member’s voice is heard.

Peer Review reports

Psychological safety is the notion where individuals feel empowered to ask questions, admit mistakes or voice concerns without fear of negative repercussions from their team [ 1 ]. This concept has been explored in varying contexts, including healthcare teams as psychological safety can have an impact on patient safety and quality of care. For healthcare professionals, psychological safety creates an environment of trust and openness to discuss concerns and raise errors [ 2 , 3 ]. This enables focus on providing high quality care, as opposed to managing the expectations around voicing dissent and disagreement. It has also been shown that psychological safety increases physician engagement [ 4 ], reduces burnout [ 5 ] and promotes creativity [ 6 ].

Appelbaum et al. surveyed 106 physicians in the United States in order to investigate the perceptions of psychological safety and various other parameters including the intention to report adverse events. Psychological safety was found to be a direct predictor of the intention to report adverse events by physicians, highlighting the importance of psychological safety in creating safer care for patients [ 7 ]. Yanchus et al. investigated 11,726 healthcare workers including psychiatrists and mental health nurses and determined that psychological safety was a direct predictor of turnover intent, emphasising the value of psychological safety in employee retention [ 8 ].

Indeed, the positive effects of psychological safety are not limited to the individual or team level - rather, they permeate throughout the entire organisational infrastructure. This draws on the concept of organisational resilience, which can be described as how well supported workers within an organisation are by across three specific levels: the individual level, team level, and organisational level [ 9 ]. Organisations which are resilient will facilitate workers to predict when a problem will arise (foresight), help individuals cope with problems which do occur (coping), and finally, find suitable ways to recover from problems and prevent them in the future (recovery) [ 9 ]. In turn, organisational resilience allows for problem management, which in a healthcare setting translates to improved patient safety measures – a typical example of organisational resilience in healthcare is the clinical handover which aims to facilitate foresight, coping and recovery across the three levels of an organisation [ 9 ]. Psychological safety is integral to maintaining organisational resilience. For example, an individual healthcare worker should feel able to raise a concern regarding a patient showing clinical signs of deteriorating (foresight) without fear of repercussions from seniors [ 9 ].

In light of the well-evidenced benefits of psychological safety on healthcare teams, it is imperative to understand the key drivers which either facilitate or act as a barrier to establishing psychological safety. Specific facilitators which have already been identified in the literature include those pertaining to the actions of leaders. For example, inclusive behaviours displayed by a leader such as active invitation and appreciation of opinions from fellow team members regardless of factors such as hierarchical differences between a leader and team member have been shown to facilitate psychological safety, exemplified by Hirak et al’s [ 10 ] study which investigated the correlation between leader inclusiveness and psychological safety within a hospital [ 3 , 11 ]. 224 team members and 55 team leaders consisting of various hospital employees including doctors and nurses were surveyed, and a positive relationship was found to exist within teams with more inclusive leaders [ 10 ].

The literature also links psychological safety with change-oriented leadership. Change-oriented leadership as described by Yuki et al [ 12 ] refer to a set of behaviours which promote innovation and change amongst teams. For example, leaders who monitor the external environment to identify opportunities or potential threats to a team, envision change, encourage innovation from their subordinates and take on personal risk to enact change are seen to be change-oriented leaders. Ortega et al [ 2 ] surveyed 107 nursing teams from various healthcare settings including primary care, intensive care and surgical settings to investigate the relationship between psychological safety and change-oriented leadership. Ortega et al. reported that teams with change-oriented leaders also reported higher psychological safety within teams [ 2 ]. This has great implications for healthcare considering innovation and non-traditional problem-solving strategies have historically proved beneficial for the industry.

Ethical leaders i.e. individuals who demonstrate appropriate conduct themselves and by doing so encourage and model exemplary conduct in their subordinates have also been cited in the literature as encouraging psychological safety [ 13 ]. Gong et al [ 14 ] surveyed the opinions of feedback-seeking behaviour amongst subordinate nurses and nurse leaders – in total, 60 leaders and 458 subordinates were investigated. Teams, where leaders were deemed to be more ethical, were found to have higher levels of psychological safety and feedback-seeking behaviour, particularly in teams with a high-power distance [ 14 ].

Barriers to psychological safety include workplace bullying and hierarchy. Arnetz et al [ 15 ] investigated the experience of workplace bullying amongst 331 registered nurses from a specific American regional healthcare system. 36.9% of responders reported being bullied in the preceding 6 months [ 14 ]. An inverse relationship was found between personal experiences of disengagement with work following personal bullying and psychological safety. Psychological safety was also associated with less personal bullying as well as witnessing others being bullied [ 15 ]. Hierarchy has also been cited in the literature, with Appelbaum et al [ 7 ] investigating the influences of power distance and leader inclusiveness on psychological safety amongst 106 medical residents. A higher perceived power distance predicted lower levels of psychological safety, whilst leader inclusiveness was positively correlated with psychological safety [ 7 ]. Higher levels of psychological safety by consequence were positively correlated with intentions to report adverse medical events, further highlighting the importance of mitigating barriers to psychological safety in order to maintain and improve patient safety.

Whilst the literature makes clear that leaders are crucial in facilitating psychological safety in healthcare teams, there is less focus on how other team members may help to improve the psychological safety of their environment. Circumstances where individuals speak up regardless of the leadership style they work under, suggests that other factors external to the leader are at play in facilitating psychological safety. Given that the literature has a strong focus on the role of the leader, attempts should be made to determine if general team behaviours, environmental factors, team culture or innate personality traits contribute to the psychological safety of a team environment and if so, what these factors may be. Likewise, are there alternative intrinsic or extrinsic factors that individuals may possess which can facilitate or impede the establishment of a psychologically safe environment.

Most of these findings on psychological safety in healthcare teams however, focuses on secondary care, with limited studies examining the application of this construct within primary care teams [ 3 , 11 ]. Arguably, the dynamics of teamwork can vary greatly between primary and secondary care multidisciplinary teams, thus a focused exploration into psychological safety in these teams is warranted.

This qualitative study aimed to identify the specific barriers and facilitators of psychological safety in primary care teams. In the context of this study, barriers and facilitators refer to the various psychological, environmental, interpersonal and organisational aspects of the multidisciplinary teams investigated. This was with a view to establish behaviours that practices can implement to harbour psychologically safe environments.

Given that the aim of this study is to identify barriers and facilitators of psychological safety within primary care teams, an inductive study approach was deemed to be a more suitable study design as opposed to a traditional hypothetico-deductive approach [ 16 ]. The lack of specific premises to prove or disprove in the context of psychological safety further supports the use of an inductive methodology [ 17 ].

Research philosophy and approach

This study utilised a mono-method qualitative research design which uses semi-structured interviews as the only mode of data collection. The present study seeks to investigate multi-disciplinary team members’ perceptions of the facilitators and barriers of PS in primary care teams. Such perspectives and insights can only be explored using a qualitative inquiry which, crucially, uses methods such as open-ended interviewing to surface opinions unconducive to quantification [ 18 ].

This study employed an interpretivist approach which leverages qualitative methods to elicit narratives, capture stories and probe perceptions to articulate and conceptualise aspects of social phenomena which cannot be quantified [ 19 ]. Interpretivism champions subjectivity, and calls on the researcher to engage their own values and beliefs, making their empathetic viewpoint a central part of the research process [ 20 ]. Critical to the interpretivist philosophy is its acknowledgement of multiple realities and therefore, this approach facilitates a deep understanding of participants’ lived experiences [ 21 ].

The very notion that within the same context there exist multiple realities experienced by different people makes an interpretivist approach appropriate for the present study exploring MDT members’ views on PS in primary care teams. By exploring PS through the lens of different MDT members, this research acknowledges the complexity of the social world and seeks to develop a deep understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

This study applies an inductive approach to theory development, which recognises the existence of a gap between observed data and derived conclusions [ 22 ]; a gap filled with underlying complexities which cannot always be distilled to ‘cause and effect’ mechanisms [ 20 ]. Inductive reasoning therefore traverses the rigid structural boundaries which govern deductive approaches and does not seek to mechanistically verify or oppose existing theory. Rather, an inductive approach is limitless. It utilises a ‘bottom up approach’ beginning with primary data collection followed by the identification of patterns and themes in an effort to construct theory [ 23 ]. Consistent with an inductive approach, this study uses qualitative methods focussed on meaning-making, allowing for a detailed exploration of participants’ lived experiences [ 24 ].

Methodology is reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research Checklist [ 25 ].

Snowball sampling enabled the recruitment of a team-focused study population, thus facilitating comparison between the perceptions of different MDT members. This was vital given that psychological safety is a team construct. Utilising snowball sampling methodology, a sample of 20 individuals from four different primary care teams ( n = 5, n = 6, n = 6, n = 3) were obtained. The sampling approach was employed in two stages. First-line participants were recruited through LinkedIn and the Royal Colleges, subject to specified inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1 ). These participants then recruited colleagues from their multidisciplinary team. For example, to recruit the participants in team 1, the head partner GP was contacted through LinkedIn. They then initiated contact with the head nurse from the team which resulted in a sample of five participants in team 1. Their employment information was verified at the time of the interview by asking their role in the practice. The response rate through LinkedIn was approximately 70% and recruitment was completed in one month. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were checked prior to the interview by asking preliminary questions to obtain their professional role. The roles included were general practitioners, practice managers, partners, healthcare assistants and nurses. The demographic information has been anonymised due to the inclusion of direct quotes being used in this report. All recruitment was in line with the approved ethics protocol. A brief synopsis outlining the study purpose and objectives were sent to the participants. Once interest was confirmed, they were provided with a participant information sheet detailing the purpose of the study and information regarding data confidentiality alongside an informed consent form to obtain consent prior to interview conduction. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. This was repeated until no further recruitment occurred [ 26 ] and data saturation was reached. Data saturation was deemed the point at which similar responses were being surfaced in the interviews with repeating rather than novel ideas, referred to by Sandelowski [ 27 ] as ‘informational redundancy’. In qualitative research, significant ambiguity exists around what is deemed an appropriate sample size [ 20 ] with limited guidance on this. Guest et al. 2006 suggest that 12 interviews are sufficient [ 28 ], while Creswell [ 29 ] recommends between 5 and 30 interviews for qualitative research. An accepted sample size of between 5 and 25 participants has been cited for studies utilising semi-structured or in-depth interviews [ 30 ]. Therefore, given the fact that data saturation was achieved at 20 interviews, this was deemed an appropriate sample size for the study.

Data collection

Data was collected using semi-structured interviews (SSIs), as they are adaptable in nature and allow stakeholders to share answers openly and independently [ 31 ]. Interviews with all 20 participants were conducted via video-conferencing (due to Covid-19 restrictions). Video conferencing platforms utilised included Zoom and Skype. Conducting the interviews in this manner offered numerous advantages including; convenience for both the interviewer and the interviewee as well as deducting travel time, thus increasing efficiency of data collection. Furthermore, this facilitates visual interaction with the added advantage that it allows the interviewer and interviewee to remain in their own comfortable locations [ 32 ]. However, video-conferencing limited our non-verbal communication which could have helped contextualise the responses. Overall, utilising video-conferencing proved advantageous in our data collection process. Interviews were audio-recorded, anonymised and stored on a secure drive before being destroyed post-transcription.

The interview schedule was designed to be open-ended to encourage participants to speak freely to allow detailed accounts to be elicited [ 33 ]. This was recommended by the five-step framework by Kallio et al [ 34 ] to create a qualitative interview guide. Kallio et al. recommended first to evaluate if a semi-structured interview is necessary. The conclusion of conducting interviews was reached as this study needed the perceptions and opinions of our participants in order to contextualise their answers. Next, a literature review was conducted to establish existing knowledge and identify the gap the interview needs to fill. This helped us with the third step of devising the questions, which included the main themes and follow up questions.

As per Kallio et al’s fourth step [ 34 ], two pilot interviews with GPs were conducted to verify the initial interview guide developed. The pilot interviews demonstrated significant overlap in the interview guide questions within the subsection “Roles and Responsibilities”, hence this subsection was summarised into three questions. Secondly, the question ‘How do you view your relationship with other team members? was removed since it required extensive clarification in both pilots. Finally, one question was added to the interview protocol, ‘Which member of the team is most influential in ensuring a psychologically safe environment?’, due to both interviewees referring frequently to the influential role of team leaders in facilitating PS within their teams. Yin [ 35 ] advocates the conduction of pilot studies as an effective method for developing ‘relevant lines of informed questioning’, enabling the refinement of data collection methods. The conduction of pilot interviews further informed the modification of the interview guide to ensure data gauged from the questions was sufficient for answering our research question.

The semi-structured interview format allowed for probing questions to be used to encourage participants to develop and elaborate on their responses, facilitating a more detailed inquiry [ 36 ]. All SSIs ranged from 20 to 45 min in duration due to differences in individual availability and commitment of the respondents. This is in line with accepted practice in the literature [ 37 ]. Three researchers (KR, NA and NH) conducted the interviews which introduced different perspectives who were able to individually interpret the participants’ non-verbal cues and the emotional aspects which often do not surface in the transcripts and are only picked up in the interview. The triangulation of researchers [ 38 ] in this manner minimised individual biases and contributed to the validity of our research. An interview schedule ( Supplementary file A ) was devised with open-ended questions to encourage participants to speak freely, facilitating a detailed inquiry [ 33 ].

Data analysis

Braun and Clarke’s six-phase methodology [ 39 ] of thematic analysis was utilised for the interview data. Phase 1 involved three researchers (RR, NH and AH) transcribing the interviews ad verbatim and developing transcript summaries. In line with an inductive approach, within phase 2, ‘in-vivo’ codes were derived from the data. Codes were reviewed and compared at the team level in phase 3 and were subsequently categorised into themes, beginning the process of theory inception. In the fourth phase, candidate themes and subthemes were reviewed against the coded data to ensure intra-theme coherence and against the entire data to ensure representability. Further refinement of themes was undertaken in phase 5 before being used to construct a coherent analytic narrative in phase six.

Reflexive statement

Reflexivity serves as a conscious acknowledgement of the researcher’s assumptions and experiences which influence the research process [ 40 ]. This study was conducted by a team of seven medical students alongside our supervisor, each with varying experiences which have shaped our perceptions of primary care. We are aware of our biases towards hierarchy in healthcare teams. However, to reduce the influence of preconceived biases we used open questions to allow free expression and had three researchers conduct the interviews to ensure triangulation.

This study explored the facilitators and barriers of psychological safety in the four primary care teams. The data analysis yielded three meta-themes: Barriers to psychological safety, facilitators of psychological safety, and shared beliefs.

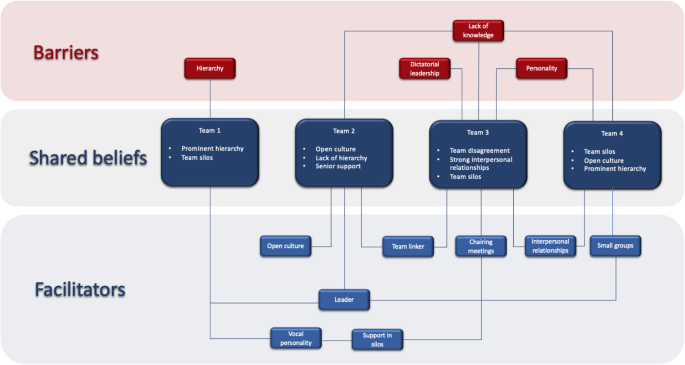

Facilitators and barriers of psychological safety are the main focus of this study, however, the additional meta-theme of shared beliefs was found to be significantly distinct from barriers and facilitators. Notably, the meta-theme shared beliefs refers to the characteristics of the team, including team dynamics and relationships, and hence provides a common basis for the interpretation of how the facilitators and barriers of psychological safety influence the respective primary care team. Figure 1 summarises the shared beliefs across the four primary care teams, as well as their relation to barriers and facilitators of psychological safety.

Illustration of primary care teams with their respective shared beliefs, alongside the barriers and facilitators to psychological safety. Lines connecting barriers and facilitators to shared beliefs indicate contextual relation

The four barriers (hierarchy, lack of knowledge, authoritarian leadership, personality) identified in this study were categorised as either organisational, team-based or individual-level barriers. An overview of the barriers and supporting quotes are shown in Table 2 .

Hierarchy was identified as an organisational level barrier to psychological safety within team 1. This fostered feelings of inferiority and a perception that other members valued their opinions less, increasing hesitancy to voice opinions. Team-based barriers included a lack of knowledge (team 2, 3 and 4) and authoritarian leadership (team 3). The perceived lack of knowledge was attributed to a lack of awareness around the respective discussion topic. This subsequently increased anxiety related to saying something incorrect or appearing as the lone member lacking in knowledge. Furthermore, authoritarian leadership hindered psychological safety with individuals feeling that decisions were enforced rather than discussed. This fostered a lack of ownership and members feeling powerless. Frustrations were two-fold: some participants were discouraged at the domineering approach to decision making, while others expressed concerns over the decisions made.

On an individual level, personality was cited as a barrier to psychological safety. Dominating personalities, particularly of those in leadership roles, acted as a barrier to psychological safety in Teams 3 and 4, by causing unequal dynamics and participation within conversations. Members also expressed that their opinions had to be repeated multiple times to be heard. Furthermore, one team member discussed intrinsic barriers such as shy personality or a fear of public speaking.

Facilitators

The eight key facilitators (leaders and leader inclusiveness, open culture, support in silos, boundary spanner, interpersonal relationships, small groups, vocal personality, chairing meetings) identified in this study were categorised as either team-based or individual-level barriers. An overview of the facilitators and supporting quotes are shown in Table 3 .

Leaders (teams 1,2 and 4) were cited as a prominent facilitator of psychological safety. Within team 1 and 2, leaders exhibiting a friendly attitude, acting in a supportive manner and inviting participation of members made them influential in facilitating psychological safety. An interesting facilitator of psychological safety which surfaced was that of groups of similar individuals in the same profession; silos (teams 1 and 3). Here, psychological safety was facilitated via two mechanisms: identifying within the silo which strengthened voice and empowerment via a silo leader, an individual with reduced power distance who acted as a spokesperson for the group. For example, several members felt more comfortable approaching their nursing team leader or a GP colleague rather than practice leadership directly.

The presence of a boundary spanner, an individual responsible for linking sub-groups within the wider MDT, was cited by participants in teams 2 and 3 as an influential facilitator of psychological safety. Fostering strong interpersonal relationships was an important facilitator of psychological safety in team 3 and 4. One member contrasted their ability to speak up as a longstanding team member compared to being a newcomer, highlighting that knowing the team enabled them to speak up. The presence of a smaller group made participants of Team 4 more comfortable and confident in voicing their opinions.

Individual level facilitators were having a vocal personality and chairing meetings. Vocal personality was a prominent facilitator in teams 1 and 3, with members in team 1 acknowledging their inherent confidence allowed them to voice opinions confidently. An interesting facilitator reported in team 3 was chairing meetings. Some participants referred to the dual perspective of the chairing role, describing that it facilitated them to speak up but they, in turn, acted as a facilitator for others.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first qualitative team-based study investigating barriers and facilitators of psychological safety in primary care teams. Obtaining the viewpoints of different healthcare professionals across four primary care teams enabled intra- and inter-group analysis, on the background of shared beliefs, which provided a contextual representation of the team dynamic. The themes that surfaced from this study can be considered at three levels; organisation, team and individual levels.

Barriers and facilitators of psychological safety emerged at an individual level, with personality influencing team dynamics significantly. Whilst the literature reporting on healthcare teams highlights how the behaviour and personality of a leader specifically can be a barrier to psychological safety [ 4 , 41 , 42 , 43 ], the impacts of dominating personalities amongst other team members is less explored. A shy personality was reported as a barrier, and whilst this may be viewed as an innate characteristic, the influence of the team in negating this should be considered. In contrast, a vocal personality emerged as a facilitator of psychological safety in this study. A relationship between personal control and voicing behaviours has been documented in healthcare literature, whereby individuals with greater autonomy feel empowered to speak up [ 44 ], however there is less exploration of the impacts of personality on speaking up behaviours in the context of psychological safety. These findings indicate that psychological safety relies on exploring the personality of both oneself and others in a team in order to establish how individuals can be best supported in the work environment.

Furthermore, our results identified barriers and facilitators at the team level. Our findings revealed that leadership roles are influential as facilitators or barriers to psychological safety. Teams 1,2 and 4 highlighted leaders who displayed support and inclusiveness as facilitators of psychological safety. Where leadership was not cited as a facilitator, it surfaced as a barrier in the form of authoritarian leadership. Literature corroborates this, highlighting a correlation between effective or inclusive leadership and psychological safety in healthcare teams [ 2 , 7 , 12 , 18 , 21 , 45 , 46 , 47 ]. In contrast, leader unreceptiveness has been reported as a barrier to raising patient concerns [ 18 , 19 ]. A key differentiator between the teams is their leadership structure in the GP practice. Members of a mono-leadership referred to their leader centralising control; this phenomenon may not have emerged in teams with multiple GP partners in the leadership structure. Although this authoritarian leadership style presents benefits in certain situations, such as emergencies occurring commonly in secondary care which require fast decision making by a single leader [ 48 ],, this is arguably less applicable and useful in primary care. Crucially, high-performing healthcare organisations are associated with broad leadership distributions [ 49 ]; our findings suggest that this should be reflected in primary care.