- Open access

- Published: 29 May 2023

Experiences of water immersion during childbirth: a qualitative thematic synthesis

- E. Reviriego-Rodrigo 1 ,

- N. Ibargoyen-Roteta 1 ,

- S. Carreguí-Vilar 2 ,

- L. Mediavilla-Serrano 3 ,

- S. Uceira-Rey 4 ,

- S. Iglesias-Casás 5 ,

- A. Martín-Casado 6 ,

- A. Toledo-Chávarri 7 ,

- G. Ares-Mateos 8 ,

- S. Montero-Carcaboso 3 ,

- B. Castelló-Zamora 9 ,

- N. Burgos-Alonso 10 ,

- A. Moreno-Rodríguez 11 ,

- N. Hernández-Tejada 12 &

- C. Koetsenruyter 13

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 23 , Article number: 395 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4498 Accesses

1 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

The increasing demand for childbirth care based on physiological principles has led official bodies to encourage health centers to provide evidence-based care aimed at promoting women’s participation in informed decision-making and avoiding excessive medical intervention during childbirth. One of the goals is to reduce pain and find alternative measures to epidural anesthesia to enhance women’s autonomy and well-being during childbirth. Currently, water immersion is used as a non-pharmacological method for pain relief.

This review aimed to identify and synthesize evidence on women’s and midwives’ experiences, values, and preferences regarding water immersion during childbirth.

A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence were conducted. Databases were searched and references were checked according to specific criteria. Studies that used qualitative data collection and analysis methods to examine the opinions of women or midwives in the hospital setting were included. Non-qualitative studies, mixed-methods studies that did not separately report qualitative results, and studies in languages other than English or Spanish were excluded. The Critical Appraisal Skills Program Qualitative Research Checklist was used to assess study quality, and results were synthesized using thematic synthesis.

Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. The qualitative studies yielded three key themes: 1) reasons identified by women and midwives for choosing a water birth, 2) benefits experienced in water births, and 3) barriers and facilitators of water immersion during childbirth.

Conclusions

The evidence from qualitative studies indicates that women report benefits associated with water birth. From the perspective of midwives, ensuring safe water births requires adequate resources, midwives training, and rigorous standardized protocols to ensure that all pregnant women can safely opt for water immersion during childbirth with satisfactory results.

Peer Review reports

Childbirth is a significant event in a woman’s life, with short- and long-term consequences that extend beyond her own health. It can also impact the well-being of her child and family, as well as her future reproductive choices and mode of delivery. A long-term follow-up study has found that positive birth experiences can enhance a woman’s self-confidence and self-esteem throughout her life [ 1 ].

In recent years, the demand for care based on the physiology of childbirth has prompted official bodies to encourage evidence-based care in health centers, aimed at empowering women to make informed decisions and minimizing obstetric intervention and medicalization during childbirth. One of the objectives is to reduce pain and explore alternative measures to epidural analgesia that increase women’s autonomy and well-being during childbirth. One such measure is water immersion, which is currently being used as a non-pharmacological method of pain relief [ 2 ].

The Cochrane systematic review “Immersion in water during labor and birth,“ by Cluett et al, defines “water immersion” as the practice of submerging a pregnant woman’s abdomen in water during any stage of labor, including dilation, expulsive, and delivery. On the other hand, “water birth” refers to the delivery of the newborn underwater [ 3 ].

Examining the experiences of mothers and midwives with water immersion is crucial, given the current emphasis on evidence-based care, efficient resource management, and the evaluation of a more humane model that reduces unnecessary interventions during labor. By reducing the need for medical interventions, water immersion may provide a more natural and positive birth experience for both mother and baby.

The objective of this qualitative synthesis of evidence was to investigate the experiences of women and midwives with water immersion during labor.

Systematic review of evidence

We conducted a systematic review of qualitative and mixed-methods studies, utilizing the SPIDER acronym (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type) to guide our review [ 4 ].

Our study sample included nulliparous or multiparous women in labor with singleton pregnancies who were healthy and at low risk of complications. In addition, we also included midwives and other professionals who were involved in obstetric care. The focus of our investigation was on the phenomenon of interest, which pertains to the experiences of women and midwives during water birth. Our study was limited to research conducted in hospital settings.

We considered published qualitative studies, studies with mixed methods designs, and surveys with free-text answer options, provided that the qualitative data could be extracted separately and had been formally analyzed using structured approaches such as thematic analysis or content analysis. We assessed the results by analyzing the narrative perspectives, experiences, and viewpoints of both pregnant women and midwives.

Our review included primary research studies and systematic reviews of qualitative studies published in English or Spanish. By synthesizing and analyzing these studies, we aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the experiences of women and midwives with water immersion during labor.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Inclusion criteria.

We included studies that utilized qualitative research methods, such as ethnographic observations, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and open-ended survey questions. Studies with appropriate analysis methods, including thematic analysis, narrative analysis, framework analysis, and grounded theory, were also included [ 5 ]. Mixed-methods studies were only considered if they clearly described their qualitative data collection and analysis methods and provided in-depth findings and interpretations. We limited our review to studies published from 2009 to 2022. Including papers from 2009 allowed for a comprehensive review of literature on water immersion in labor and birth, as the first Cochrane review by Cluett et al. in that year was a significant milestone in the development of research in this area.

Exclusion criteria

We have excluded studies conducted outside the hospital setting, such as home births, from our analysis. Additionally, we have excluded studies that were published in languages other than English or Spanish.

By carefully selecting studies that met our inclusion criteria and excluding those that did not, we aimed to ensure that our review provided a comprehensive and high-quality synthesis of the experiences of women and midwives with water immersion during labor.

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted a comprehensive search to identify all relevant studies, updating it until August 2022. We limited our search to studies published in English or Spanish from 2009 onwards. We searched several databases, including The Cochrane Library (Wiley), Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) [Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)], Pubmed/Medline, Embase (OvidWeb), Web of Science (WOS), PsycINFO (OvidWeb), and Cinahl (EBSCOhost), using a combination of controlled and free language terms, such as “Labor”, “Natural Childbirth”, “Waterbirth” or “Water immersion”. The search strategies were adapted to each database, with the use of MESH descriptors and qualifiers to increase specificity when necessary. Alerts were set up in Medline (PubMed) and Embase (OVID) to identify any documents published up to August 2022. We also manually searched the literature cited in the selected studies to locate any relevant information not retrieved in the previous steps.

After completing the searches, we removed any duplicate citations, and the remaining records were uploaded to RefWorks reference manager. To assist with preparing systematic reviews, we used Ryyan, a software designed for this purpose.

Selection of studies

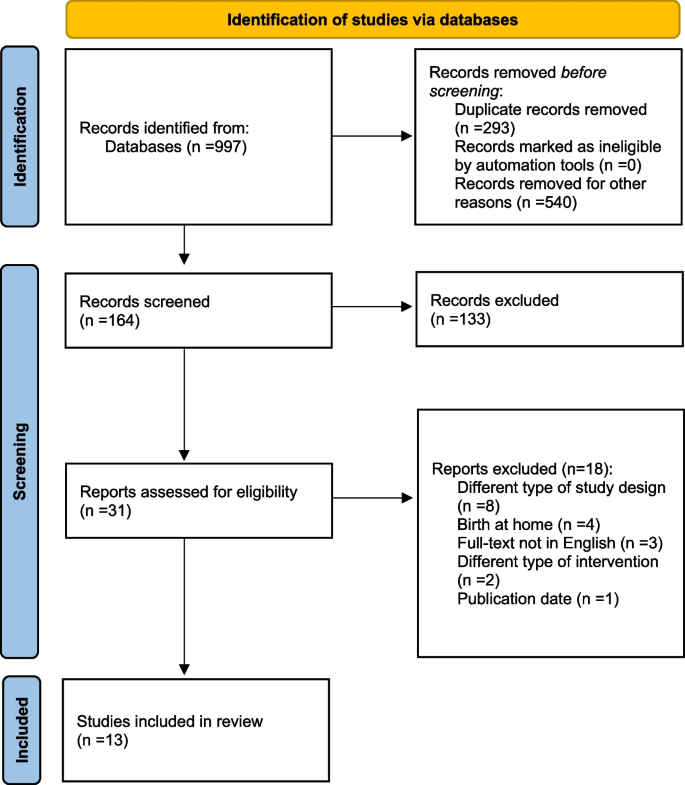

We imported all search results into Rayyan, and removed any duplicates. Subsequently, two review authors independently assessed the retrieved search results against the inclusion criteria. This screening process involved two stages: first, screening titles and abstracts, and then assessing the full-text articles. Employing two reviewers to screen the studies was advantageous as it allowed for an in-depth exploration of the relevance and meaning of the study findings. To arrive at a final selection, we held discussions until a consensus was reached, based on the study eligibility criteria. The entire screening process is summarized in a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1 ), which outlines the number of studies removed and retained at each stage.

PRISMA flow chart of included studies

Quality appraisal/ assessment of methodological limitations

Prior to comparing findings and reaching a consensus, two reviewers conducted an assessment of methodological limitations for each paper using the Spanish version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool for qualitative studies (CASPe) [ 6 ]. Any disagreements between the reviewers were addressed and discussed until a consensus was reached. It is important to note that we did not exclude any studies based on our assessment of methodological limitations.

In the case of the systematic review of qualitative studies, the “Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research” tool [ 7 ] was applied.

Data extraction and thematic synthesis

We employed a standardized data collection form to extract the relevant data. Thematic synthesis was conducted, following the approach developed by Thomas and Harden [ 5 ]. To ensure a comprehensive analysis, all text in the results or findings sections of the included studies, including participant quotations and interpretations by the authors of the studies, were treated as data.

The lead reviewer (ER) extracted the data into tables and assigned codes to each line of text, based on its meaning and content, in accordance with the method outlined by Thomas and Harden [ 5 ]. These codes were then organized into descriptive themes, some of which corresponded with the original findings of the included studies. Next, the codes were grouped into logical and meaningful clusters in a hierarchical tree structure to form descriptive themes and sub-themes. Finally, the descriptive themes were developed into analytical themes, which enabled us to extend the analysis beyond the original studies.

Internal/external review

The project’s research team conducted an internal review of the work. After completing this stage, the work underwent an external review process, with recognized experts in the field providing feedback to ensure its quality, accuracy, and validity. Before participating in the review, the experts completed a document declaring any potential conflicts of interest.

Included studies and quality assessment

Thirteen studies were identified for the review using PRISMA process (Fig. 1 ).

Characteristics of the included studies

The 13 studies included in this analysis were published between 2013 and 2020, and 9 investigated both the first and second stages of labor, while 4 studies focused solely on the second stage of labor. Eight countries are represented across the studies, Australia ( n = 4), United Kingdom ( n = 2), Sweden ( n = 2), Canada ( n = 1), Portugal ( n = 1), Greece ( n = 1), Scotland ( n = 1), and UU.EE ( n = 1). Methodological approaches varied and qualitative methods used for purposes of data collection from women and midwives, most commonly involved interviews.

Nine studies focussed on women’s experience of water immersion during childbirth (Clews et al., 2019; Poder et al., 2020; Fair et al., 2020; Gonçalves et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2018; Ulfsdottir et al., 2018; Antonakou et al., 2018; McKenna et al., 2013; Carlsson et al., 2020) [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ], one study (Milosevic et al., 2019) [ 17 ] that explores the factors that determine the use of immersion during childbirth according to the point of view of both women and midwives and medical professionals (obstetricians, neonatologists and pediatricians), and three more studies on midwives’ experience with water immersion during childbirth (Cooper et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2018; Nicholls et al., 2016 [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

Tables 1 , 2 and 3 provide a detailed overview of the study characteristics, including information about the author(s)/country, date, study design, participants, method of data collection, method of analysis, recruitment method and setting, study focus, and main findings.

The quality of these studies was evaluated using the CASPe tool, which is widely recognized as a reliable assessment method. For easy reference, the Supplementary Material includes summary tables that provide an overview of the quality of evidence presented in the included studies.

Mothers’ experiences with water immersion during labor and birth

Clews et al. [ 8 ] conducted a metasynthesis of qualitative studies on women’s experiences with water birth. They found four primary themes, which included the mother’s knowledge of water birth, their perception of a physiologic birth, water, autonomy, and control, and water birth easing the transition. The authors concluded that water birth can be an empowering experience for those who choose it and reinforces women’s sense of autonomy and control during the birthing process.

The study conducted by Poder et al. [ 9 ] aimed to identify factors that influence women’s decision to choose water birth or not. They used focus groups to create a validated questionnaire utilizing Discrete Choice Experiments (DCE). The questionnaire considered various attributes that women consider important in making their decision, including type of delivery, duration of labor, pain sensation, risk of severe tearing, risk of newborn death, and general condition (Apgar score at 5 min).

The study by Fair et al. [ 10 ] explored the decision-making process of women who planned to give birth in water. Women sought information from the internet and social networks and desired to limit medical interventions during childbirth. Support from doulas and midwives played a critical role in their decision-making process, while many experienced resistance from family, friends, and colleagues. Although not all women gave birth in water, most reported positive experiences and felt empowered. They encouraged other women to consider water birth and expressed a desire to have a water birth in the future.

In the study conducted by Gonçalves et al. [ 11 ] in Portugal, semi-structured interviews were conducted with mothers who had experienced one or more water births before they were no longer offered by the public health system. The analysis resulted in the identification of seven categories, but the study primarily focuses on two categories: the benefits of water immersion during childbirth, including pain relief and the ability to witness the birth of the child, and the satisfaction of women with the experience.

The study conducted by Lewis et al. in 2018 [ 12 ] aimed to explore the motivations, facilitating and hindering factors, and the birth experiences of women who gave birth in water in a tertiary public hospital in Australia. Telephone interviews were conducted with 296 women 6 weeks after giving birth. Of the participants, only 31% were able to have a water birth, with multiparous women having a higher success rate than primiparous women. Women who planned for a water birth cited pain relief, preference, association with natural childbirth, calming atmosphere, and recommendation as reasons. Support, particularly from midwives, played a crucial role in the success of water birth. The study did not specify which obstetric complications prevented of the women from giving birth in water.

Ulfsdottir et al. [ 13 ] conducted in-depth interviews with primiparous and multiparous mothers three to five months after giving birth. and found that water birth created a comfortable, home-like space that helped women feel relaxed, safe, and in control during childbirth. Three categories emerged: “synergy between body and mind,“ “privacy and discretion,“ and “natural and pleasant.“ The study suggested that water birth could enhance the childbirth experience, but the hospital where the study was conducted provided ongoing support, which may have contributed to positive experiences regardless of whether participants had a water birth or not.

Antonakau et al. [ 14 ] conducted a study on the experiences of women who gave birth using water birth in private facilities in Greece. The study identified three themes: water birth is a natural way of giving birth, healthcare professionals give contradictory messages regarding water births, and the supportive role of partners during the process. All participants reported a positive experience, with water immersion helping them manage pain and feel empowered after birth, resulting in successful breastfeeding for over a year. However, women had difficulty finding healthcare professionals who supported their choices, while they felt very supported by their partners. It is important to note that the participants were a homogenous group, primarily older, more educated, and financially able to afford private maternity care.

McKenna’s study [ 15 ] explored the experiences of women who had a water birth after a previous cesarean section in a Scottish midwifery-led unit. The study found that water birth minimized medical intervention, maximized physical and psychological benefits, and allowed women to have greater control and choice during childbirth. The study also highlighted the women’s management of potential risks associated with water birth and their interactions with healthcare providers, family, and friends.

Carlsson et al. [ 16 ] study included women who gave birth in water. The study identified physical and psychological benefits, including pain relief and improved relaxation, as well as negative experiences such as equipment problems and concerns related to water birth. Participants noted a lack of reliable information on water births and had to seek supplementary information online. The study highlights the need for accessible and reliable information on water births.

Mothers’ and midwives’ experiences with water immersion during labor and birth

Milosevic et al. [ 17 ] conducted a study to investigate factors that influence the use of water immersion during childbirth. The study employed online focus groups with women and midwives, as well as interviews with medical professionals. Eligibility criteria were found to limit access to water births, and obstetrician-led units were described as overly medicalized settings with limited provision of water births. Midwives were found to increase access to water births by proactively offering it as an option during childbirth and providing information to women about water birth during antenatal care.

Midwives’ experiences with water immersion during labor and birth

Cooper, Nicholls, and Lewis have conducted three studies to investigate the experiences of midwives with water immersion during labor or birth [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. These studies shed light on the benefits and challenges associated with water immersion, as well as the attitudes of midwives towards this birthing option. By examining midwives’ perspectives, these studies provide valuable insights into the implementation and promotion of water immersion.

A study by Cooper et al. [ 18 ] investigated the policies and guidelines for water immersion during labor and birth in Australia, as well as midwives’ experiences and perspectives. The study included a literature search, interviews, and an online questionnaire, and found that midwives must be accredited to facilitate water immersion to promote access to this option. However, midwives faced barriers related to accreditation and inconsistent guidelines across facilities. The study suggests the need for standardized guidelines and improved training opportunities for midwives to ensure the safe and effective use of water immersion during labor and birth. Overall, the study highlights the importance of promoting access to water immersion as a birthing option while ensuring appropriate training and guidelines for healthcare professionals.

Lewis et al. [ 19 ] examined midwives’ perceptions of their education, knowledge, and practice of water immersion during labor and birth in Australia. The study used a two-phase mixed-methods approach, including a questionnaire and focus groups. The results of the questionnaire showed that 93% of midwives felt confident attending water births after attending an average of seven water births, and they enjoyed facilitating water immersion. The focus groups identified several positive aspects of caring for women during water immersion, such as instinctive birth and a woman-centered environment, as well as challenges related to learning through observation and the need for support to enable water births. Overall, the study highlights midwives’ positive experiences and the importance of training and support to ensure safe and effective water immersion during labor and birth.

The study by Nicholls et al. [ 20 ] emphasizes the importance of midwives’ competence and confidence in supporting water births according to local clinical practice guidelines. Interviews with 16 midwives and a focus group with 10 others identified three categories related to confidence acquisition: pre-pathway factors, pathway to confidence, and maintenance of confidence. The study identified three categories that affect midwives’ confidence in supporting water births: 1) factors before entering the profession, 2) factors that contribute to confidence development, and 3) factors that help maintain confidence.

The study’s findings have three significant implications for midwifery practice. Firstly, it is recommended that graduate students and midwives work in maternity wards led by midwives who support normal physiological birth. Secondly, it is suggested that learning directly from experienced midwives who can address their specific needs would benefit maternity wards. Lastly, it is emphasized that midwives have a crucial role as “protectors” of normal physiological birth, and mandatory attendance at sessions highlighting this role and the current evidence supporting normal birth, including water immersion during labor, is necessary.

Thematic synthesis

To summarize the most significant findings from the qualitative studies on water immersion in childbirth, several tables have been created based on the themes that emerged from the studies. Thematic synthesis identified the following three themes:

Theme 1. Reasons for choosing water birth.

This theme investigates the factors that influenced women’s decision to use water immersion during childbirth, such as pain relief, relaxation, and a desire for a more natural birth experience. Some professionals also cited benefits to the baby, such as reducing stress and facilitating a smoother transition to the outside world.

Theme 2. Benefits of water immersion.

This theme includes the positive experiences reported by women who used water immersion during labor and birth, such as reduced pain, increased relaxation, and a greater sense of control. Midwives and other health professionals also noted benefits, including improved maternal-fetal bonding and a decreased need for medical interventions.

Theme 3. Barriers and facilitators of water immersion:

This theme includes factors that can either hinder or promote the use of water immersion during childbirth. For example, midwives’ attitudes and training were identified as critical facilitators, while hospital policies and protocols were seen as significant barriers. Other factors included access to appropriate facilities and equipment, communication and coordination among healthcare providers, and support from partners and family members.

Tables 4 , 5 and 6 provide a comprehensive overview of the themes and subthemes present in the included studies. These tables serve as a visual representation of the key concepts and ideas that emerged from the analysis of the data.

Table 4 presents the reasons for choosing a water birth based on the findings of the included studies.

The table includes 5 identified reasons for choosing water birth and the sources of the evidence supporting each reason. The reasons were identified by four studies: Clews et al. (2019), Poder et al. (2020), Fair et al. (2020), and Lewis et al. (2018) [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 ].

The most common reasons for choosing a water birth, as reported the studies, include prior knowledge of water birth [ 8 , 12 ], recommendation by others [ 8 , 12 ], relaxation and decreased anxiety [ 9 , 12 ], sense of comfort and well-being [ 9 ], desire for natural birth [ 10 , 12 ], pain relief during labor [ 9 , 12 ]. Other reported benefits of water birth include reduced likelihood of perineal tearing [ 9 ], shortened active phase of labor [ 9 ], no increased risk of newborn mortality compared to conventional delivery [ 9 ], no adverse effect on newborn’s general condition (Apgar test) [ 9 ], and no increased risk of infection for the newborn [ 9 ].

Overall, the table suggests that women may choose water birth for various reasons, such as personal preference and potential benefits, without increasing the risk of adverse outcomes for the newborn.

Table 5 summarizes the identified benefits of water birth, along with the sources of evidence supporting each benefit.

Table 5 summarizes the reported benefits of water birth as identified by women who had experienced it, as well as midwives who have supported such births. The benefits include a greater feeling of autonomy and control over the childbirth process [ 8 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 16 , 19 ], increased opportunities for experiencing a more natural childbirth [ 8 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 16 , 19 ], easing the transition into motherhood [ 8 ], providing pain relief without relying on medical interventions [ 11 , 12 , 16 ], allowing the opportunity to witness the birth of the child [ 11 ], the option of immersion in water [ 11 , 12 ], immersion in water for increased mobility and a sense of lightness [ 11 , 16 ], tranquility, improved breathing, and relaxation leading to synergy between body and mind [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 16 , 19 ], more privacy and discretion during the childbirth process [ 13 ], minimizing the medicalization of childbirth, resulting in less use of analgesia and oxytocin [ 10 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 ], a feeling of positive experience [ 8 , 10 , 11 , 12 ], a feeling of success in childbirth [ 11 ], and more physical and psychological benefits [ 15 , 16 ].

Overall, the table highlights the various benefits of water birth as reported by women and midwives, including physical and psychological advantages, which may encourage women to consider water birth as a viable option for childbirth.

Additionally, Table 6 presents a comprehensive overview of the barriers and facilitators that have been identified in the studies analyzed.

Table 6 provides a summary of the barriers and facilitators identified in the studies included in this analysis related to water immersion during childbirth. The references in the table include several studies that investigated water immersion during childbirth, such as Fair et al. 2020 [ 10 ], Lewis et al. 2018 [ 12 ], Antonakou et al. 2018 [ 14 ], McKenna et al. 2013 [ 15 ], Carlsson et al. 2020 [ 16 ], Milosevic et al. 2019 [ 17 ], Cooper et al. 2019 [ 18 ], Lewis et al. 2018 (midwives) [ 19 ], and Nicholls et al. 2016 [ 20 ].

The table lists various factors that could either impede or promote water immersion during childbirth.

The barriers to water immersion during childbirth identified in this study include safety concerns related to potential risks associated with waterbirth after cesarean section [ 15 ] and obstetric complications [ 12 ]. The lack of support from family members and healthcare professionals was also identified as a barrier to water immersion during childbirth [ 10 ].

On the other hand, several facilitators of water immersion in childbirth were identified, including the availability of bathtubs and appropriate usage techniques [ 17 ], clear and consistent eligibility criteria for water immersion during childbirth [ 17 ], and support from health professionals [ 10 , 12 , 14 , 17 , 20 ]. Moreover, training and support for healthcare professionals attending water immersion childbirths, including proper techniques and safety precautions, also facilitate successful water immersion childbirths [ 12 , 17 , 18 , 20 ].

Finally, provision of clear and accurate information to pregnant women about the benefits and risks of water immersion childbirths, promotion of water immersion through education [ 16 , 17 ], and a culture of support for water immersion during childbirth were identified as crucial facilitators for successful water immersion childbirths.

To ensure safe water births, midwives emphasize the importance of having adequate resources, consistent protocols, specialized training, and a supportive culture towards water immersion during childbirth. This support should come from all healthcare professionals involved in the birth process, not just midwives. By ensuring these factors are in place, midwives can confidently attend water births and provide the best care for the mother and baby.

This article examines qualitative studies that explore the experiences of women and healthcare teams caring for mother-newborn pairs.

The results of the qualitative studies suggest that women who choose to use water immersion during labor often have a positive and empowering experience, leading to a more natural childbirth and increased satisfaction [ 8 ]. However, the studies also identified various barriers such as potential obstetric complications, lack of support from family members and healthcare professionals, and inadequate resources and facilities for water births. To offer this service safely and effectively, facilities must have proper equipment, maintenance and cleaning protocols, action protocols, and contingency plans for potential complications. Healthcare professionals must also receive specialized training in water birth practices, and the resource must be readily available upon request [ 10 , 12 ].

One of the studies [ 9 ] examined the factors that can influence a woman’s decision to have a water birth and found that the most significant factors were pain reduction, the risk of neonatal mortality, the risk of severe perineal tears, slightly better general condition of the newborn (as indicated by the Apgar test), and reduction of the duration of the active phase of labor. The study also highlighted the importance of providing accurate and comprehensive information to pregnant women about water immersion during childbirth, as many women reported not receiving enough information on this option.

Two studies conducted by Carlsson et al. (2020) [ 16 ] and Milosevic et al. (2019) [ 17 ] revealed the insufficient provision of information about water births during antepartum classes and midwife consultations. Furthermore, it is essential to incorporate the systematic collection of data obtained from the use of water birth to address the quality-of-care indicators during childbirth. This approach will ensure that pregnant women who choose water births during labor receive the highest level of safe and quality care.

During the final stage of writing this article, the study by Feeley C. et al., 2021 [ 21 ] was retrieved through alerts. This study is a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies and used GRADE-CERQual [ 22 ] to evaluate the results. The meta-synthesis included seven studies to evaluate the impact of water immersion during labor [ 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 23 , 24 , 25 ], out of which four were part of the systematic review [ 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. The findings revealed that women who used water immersion during any stage of labor facilitated women’s physical and psychological needs, offering effective analgesia and a versatile tool that women can adapt and influence to best suit their individual needs. Women who used warm water immersion for labor and/or birth described the experience as liberating, transformative, and empowering, resulting in a positive birth experience. Based on these results, the study suggests that maternity professionals and services should improve women’s access to water immersion and offer it as a standard method to of pain relief during labor for low-risk pregnant women.

Qualitative studies have consistently shown that women who have experienced water births associate numerous benefits with the practice. These benefits include reduced pain and discomfort during labor, a greater sense of relaxation and control, increased satisfaction with the birth experience, and improved maternal and fetal outcomes. Additionally, water immersion during labor has been found to reduce the need for pharmacological pain relief, interventions such as episiotomy, and operative deliveries. These findings highlight the potential benefits of water immersion as a safe and effective option for women during labor and delivery.

Midwives emphasize the importance of adequate resources, standardized and rigorous protocols, training for midwives, and a supportive culture for water immersion during childbirth, with input from all professionals involved in attending the birth, including those who care for both mothers and newborns.

It is recommended to improve the information provided to women regarding pain relief options, establish common protocols for water births in NHS hospitals, standardize training for these deliveries, and increase human and material resources to ensure that all pregnant women have the possibility of safely and satisfactorily using hot water immersion during labor, regardless of their location.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Maimburg RD, Væth M, Dahlen H. Women’s experience of childbirth - a five year follow-up of the randomised controlled trial “Ready for Child Trial. Women Birth. 2016;29(5):450–4.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mallén Pérez L, Terré Rull C, Palacio Riera M. Inmersión en agua durante el parto: revisión bibliográfica. Matronas Prof. 2015;16(3):108–13.

Google Scholar

Cluett ER, Burns E, Cuthbert A. Immersion in water during labour and birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD000111.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A, Beyond PICO. The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8: 45.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cano Arana A, González Gil T, Cabello López JB. por CASPe. Plantilla para ayudarte a entender un estudio cualitativo. En: CASPe. Guías CASPe de Lectura Crítica de la Literatura Médica. Alicante: CASPe; 2010. pp. 3–8. Cuaderno III.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;27(12): 181.

Article Google Scholar

Clews C, Church S, Ekberg M. Women and waterbirth: a systematic meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Women Birth. 2020;33(6):566–73.

Poder TG, Carrier N, Roy M, Camden C. A discrete choice experiment on women’s preferences for water immersion during labor and birth: identification, refinement and selection of attributes and levels. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;16(6):1936.

Fair CD, Crawford A, Houpt B, Latham V. After having a waterbirth, I feel like it’s the only way people should deliver babies”: the decision making process of women who plan a waterbirth. Midwifery. 2020;82:102622.

Gonçalves M, Coutinho E, Pareira V, Nelas P, Chaves C, Duarte J. Woman’s satisfaction with her water birth experience. Comput Support Qual Res. 2018;861:255.

Lewis L, Hauck YL, Crichton C, Barnes C, Poletti C, Overing H, Keyes L, Thomson B. The perceptions and experiences of women who achieved and did not achieve a waterbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;10(1):23.

Ulfsdottir H, Saltvedt S, Ekborn M, Georgsson S. Like an empowering micro-home: a qualitative study of women’s experience of giving birth in water. Midwifery. 2018;67:26–31.

Antonakou A, Kostoglou E, Papoutsis D. Experiences of greek women of water immersion during normal labour and birth. A qualitative study Eur J Midwifery. 2018;12(2):7.

McKenna JA, Symon AG. Water VBAC: exploring a new frontier for women’s autonomy. Midwifery. 2014;30(1):e20-5.

Carlsson T, Ulfsdottir H. Waterbirth in low-risk pregnancy: an exploration of women’s experiences. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(5):1221–31.

Milosevic S, Channon S, Hughes J, Hunter B, Nolan M, Milton R, Sanders J. Factors influencing water immersion during labour: qualitative case studies of six maternity units in the United Kingdom. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;23(1):719.

Cooper M, Warland J, McCutcheon H. Practitioner accreditation for the practice of water immersion during labour and birth: results from a mixed methods study. Women Birth. 2019;32(3):255–62.

Lewis L, Hauck YL, Butt J, Western C, Overing H, Poletti C, Priest J, Hudd D, Thomson B. Midwives’ experience of their education, knowledge and practice around immersion in water for labour or birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;19(1):249.

Nicholls S, Hauck YL, Bayes S, Butt J. Exploring midwives’ perception of confidence around facilitating water birth in western Australia: a qualitative descriptive study. Midwifery. 2016;33:73–81.

Feeley C, Cooper M, Burns E. A systematic meta-thematic synthesis to examine the views and experiences of women following water immersion during labour and waterbirth. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(7):2942–56.

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13(Suppl 1):2.

Hall SM, Holloway IM. Staying in control: women's experiences of labour in water. Midwifery. 1998;14(1):30–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0266-6138(98)90112-7 .

Maude RM, Foureur MJ. It's beyond water: stories of women's experience of using water for labour and birth. Women Birth. 2007;20(1):17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2006.10.005 . Epub 2006 Dec 14.

Sprague, Annie G. An investigation into the use of water immersion upon the outcomes and experience of giving birth [Thesis]. Australian Catholic University; 2004. https://doi.org/10.4226/66/5a94ac625e498 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals and organizations: Arantza Romano Igartua, Mª del Puerto Landa Ortiz de Zárate, Fernando Arizmendi, and Joxe Arizmendi from the Area of Documentation and Specialized Libraries of the Department of Health of the Basque Government, Directorate of Health Research and Innovation. They also thank José Asua Batarrita, who is currently retired from Osteba, Department of Health of the Basque Government; Anaitz Leunda Iñurritegui from Osteba, Health Technology Assessment, Knowledge Management and Evaluation, Basque Foundation for Health Innovation and Research (BIOEF); Rosa María López Rodríguez, Program Director of the Women’s Health Observatory, General Directorate of Public Health, Ministry of Health; José Luis Quintas Díez, Vice-Minister of Health of the Basque Government; and Ignacio Rucandio Alonso, External Technical Support from the Women’s Health Observatory, General Directorate of Public Health, Ministry of Health.

No specific funding has been required to develop this article. The financial support for the activities of the Spanish Network of Agencies for Assessing National Health System Technologies and Performance (RedETS) is provided by the Spanish Ministry of Health.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Osteba, Health Technology Assessment, Knowledge Management and Evaluation, Basque Foundation for Health Innovation and Research (BIOEF), Barakaldo-Bizkaia, Spain

E. Reviriego-Rodrigo & N. Ibargoyen-Roteta

La Plana University Hospital, Villarreal-Castellón, Spain

S. Carreguí-Vilar

Osakidetza, OSI Debabarrena, Mendaro Hospital, Mendaro-Gipuzkoa, Spain

L. Mediavilla-Serrano & S. Montero-Carcaboso

Hospital da Barbanza, Ribeira-A Coruña, Spain

S. Uceira-Rey

Hospital do Salnés, Vilagarcía de Arousa-Pontevedra, Spain

S. Iglesias-Casás

Universidad Internacional de La Rioja UNIR, Logroño-La Rioja, Spain

A. Martín-Casado

Canary Islands Health Research Institute Foundation, Network for Research on Chronicity, Primary Care, and Health Promotion (RICAPPS), The Spanish Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment and Services of the National Health System (RedETS), Madrid, Spain

A. Toledo-Chávarri

Pediatrics Department, Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid, Spain

G. Ares-Mateos

Documentary of the Department of Health of the Basque Government, Territorial Delegation of Health of Bizkaia, Bilbao, Spain

B. Castelló-Zamora

Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Nursery, UPV/EHU, ES, Leioa, Spain

N. Burgos-Alonso

Osakidetza, OSI Araba, Hospital Txagorritxu, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain

A. Moreno-Rodríguez

People with Intellectual Disabilities, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain

N. Hernández-Tejada

Mayan Center, Maternity, Yoga and Accompaniment, Bilbao, Spain

C. Koetsenruyter

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ER was involved in all aspects of the project, including contributing to the conception and design of the study, as well as coordinating its various stages. ER and NIR both contributed to the interpretation of study results and reviewed relevant documents. SCV, LMS, SUR, SIC, AMC, SMC, and GAM provided a clinical perspective by reviewing the article and sharing their experiences with immersion in water during labor and birth. Their valuable insights have greatly contributed to the quality of this work. ATCh made significant contributions to the development of methods for conducting thematic analysis in qualitative studies. BCZ designed the search strategies, organized the articles in a bibliographic reference manager, retrieved articles, and developed the documentation methodology. NBA has conducted a thorough review of the manuscript with a focus on its public health implications. AMR, NHT, and CK have reviewed the manuscript, analyzed the importance of outcome variables, and provided ideas to improve it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to E. Reviriego-Rodrigo .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval for this study was not required in accordance with national legislation and institutional requirements due to fact that the data presented are anonymous, present no potential for identification of specific individuals with the dissemination of the research results, and are not considered to be sensitive or confidential in nature.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Reviriego-Rodrigo, E., Ibargoyen-Roteta, N., Carreguí-Vilar, S. et al. Experiences of water immersion during childbirth: a qualitative thematic synthesis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23 , 395 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05690-7

Download citation

Received : 11 January 2023

Accepted : 08 May 2023

Published : 29 May 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05690-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Natural childbirth

- Water Immersion

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

ISSN: 1471-2393

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Aug. 15, 2022

Emory University School of Nursing assistant professor Priscilla Hall, PhD, contributed to a recent meta-analysis study on water births that is gaining far-reaching recognition. The study shows that water births provide clear benefits for mothers and their babies, with fewer complications than standard care methods. The new research involving Hall is receiving significant attention from medical professionals and media sources such as “Good Morning America.”

Water birth is when a woman in labor gives birth in a deep bath or birthing pool. The newborn starts breathing as soon as his or her face emerges from the surface of the water. Water birth is relatively uncommon in the United States, and is considered an alternative care modality, despite being an intervention that is safe and valuable to birthing women. The reasons for the lack of availability of this intervention are complex, but one contributing factor is a lack of information about water birth safety in medical education.

“This makes the intervention feel foreign to physicians and facilitates the assumption that water birth is an alternative form of care primarily for midwifery patients in out of hospital settings,” Hall says. “This meta-analysis study was focused mostly on hospital-based care, the setting where physicians provide care and where 98% of U.S. births happen. The study’s focus on the hospital setting made it meaningful to physicians and gave it broader attention.”

The study was done in collaboration with researchers from Oxford Brookes University, with Ethel Burns, PhD, as primary investigator, Jennifer Vanderlaan, PhD, from the University of Nevada Las Vegas, and Claire Feeley, PhD, from King’s College in London. A synthesis of the available evidence led the team to conclude that water births in an obstetric setting have numerous benefits, including lower pain levels and reduced heavy bleeding in labor. The study also showed that waterbirths lead to higher satisfaction levels for mothers and improved odds of avoiding perineal tears or lacerations.

The Royal College of Midwives expressed support for the study , stating, “Research showing the safety and positive benefits for women having a water birth has been welcomed by the Royal College of Midwives. The research showed that women having a water birth in a hospital obstetric unit had fewer medical interventions and complications during and after the birth.”

This meta-analysis research confirms that water births are safe for women, and Hall hopes that medical professionals will consider the intervention as a viable option for all low-risk women, regardless of the birth setting.

“I would like to see water tubs in every hospital. The research shows that water births are safe to offer as a birthing modality. I am hopeful that the attention this study receives will move things in that direction.”

For more information about this study, click here .

About the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing

Emory University's Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing produces nurse leaders who are transforming healthcare through science, education, practice, and policy. Graduates go on to become national and international leaders in patient care, public health, government, research, and education. Others become qualified to seek certification as nurse practitioners and nurse-midwives. The doctor of nurse practice (DNP) program trains nurse anesthetists and advanced leaders in healthcare administration. The school also maintains a PhD program in partnership with Emory's Laney Graduate School. For more information, visit https://www.nursing.emory.edu/ .

About Priscilla Hall, PhD

Hall lectures in the areas of maternal child nursing and midwifery and works in the maternity simulation lab at the Emory University Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing. She received her PhD from Emory’s Laney Graduate School, where she received the Silver Bowl Award for outstanding work as a PhD candidate. Her dissertation was titled: “Keeping it together and falling apart: women’s experiences of childbirth.” Prior to her academic work, Hall was in clinical practice as a nurse midwife, and she is currently engaged in midwifery practice in the homebirth setting.

- School of Nursing

- Woodruff Health Sciences Center

Recent News

Download emory news photo.

By downloading Emory news media, you agree to the following terms of use:

Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License

By exercising the Licensed Rights (defined below), You accept and agree to be bound by the terms and conditions of this Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License ("Public License"). To the extent this Public License may be interpreted as a contract, You are granted the Licensed Rights in consideration of Your acceptance of these terms and conditions, and the Licensor grants You such rights in consideration of benefits the Licensor receives from making the Licensed Material available under these terms and conditions.

Section 1 – Definitions.

- Adapted Material means material subject to Copyright and Similar Rights that is derived from or based upon the Licensed Material and in which the Licensed Material is translated, altered, arranged, transformed, or otherwise modified in a manner requiring permission under the Copyright and Similar Rights held by the Licensor. For purposes of this Public License, where the Licensed Material is a musical work, performance, or sound recording, Adapted Material is always produced where the Licensed Material is synched in timed relation with a moving image.

- Copyright and Similar Rights means copyright and/or similar rights closely related to copyright including, without limitation, performance, broadcast, sound recording, and Sui Generis Database Rights, without regard to how the rights are labeled or categorized. For purposes of this Public License, the rights specified in Section 2(b)(1)-(2) are not Copyright and Similar Rights.

- Effective Technological Measures means those measures that, in the absence of proper authority, may not be circumvented under laws fulfilling obligations under Article 11 of the WIPO Copyright Treaty adopted on December 20, 1996, and/or similar international agreements.

- Exceptions and Limitations means fair use, fair dealing, and/or any other exception or limitation to Copyright and Similar Rights that applies to Your use of the Licensed Material.

- Licensed Material means the artistic or literary work, database, or other material to which the Licensor applied this Public License.

- Licensed Rights means the rights granted to You subject to the terms and conditions of this Public License, which are limited to all Copyright and Similar Rights that apply to Your use of the Licensed Material and that the Licensor has authority to license.

- Licensor means the individual(s) or entity(ies) granting rights under this Public License.

- Share means to provide material to the public by any means or process that requires permission under the Licensed Rights, such as reproduction, public display, public performance, distribution, dissemination, communication, or importation, and to make material available to the public including in ways that members of the public may access the material from a place and at a time individually chosen by them.

- Sui Generis Database Rights means rights other than copyright resulting from Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases, as amended and/or succeeded, as well as other essentially equivalent rights anywhere in the world.

- You means the individual or entity exercising the Licensed Rights under this Public License. Your has a corresponding meaning.

Section 2 – Scope.

- reproduce and Share the Licensed Material, in whole or in part; and

- produce and reproduce, but not Share, Adapted Material.

- Exceptions and Limitations . For the avoidance of doubt, where Exceptions and Limitations apply to Your use, this Public License does not apply, and You do not need to comply with its terms and conditions.

- Term . The term of this Public License is specified in Section 6(a) .

- Media and formats; technical modifications allowed . The Licensor authorizes You to exercise the Licensed Rights in all media and formats whether now known or hereafter created, and to make technical modifications necessary to do so. The Licensor waives and/or agrees not to assert any right or authority to forbid You from making technical modifications necessary to exercise the Licensed Rights, including technical modifications necessary to circumvent Effective Technological Measures. For purposes of this Public License, simply making modifications authorized by this Section 2(a)(4) never produces Adapted Material.

- Offer from the Licensor – Licensed Material . Every recipient of the Licensed Material automatically receives an offer from the Licensor to exercise the Licensed Rights under the terms and conditions of this Public License.

- No downstream restrictions . You may not offer or impose any additional or different terms or conditions on, or apply any Effective Technological Measures to, the Licensed Material if doing so restricts exercise of the Licensed Rights by any recipient of the Licensed Material.

- No endorsement . Nothing in this Public License constitutes or may be construed as permission to assert or imply that You are, or that Your use of the Licensed Material is, connected with, or sponsored, endorsed, or granted official status by, the Licensor or others designated to receive attribution as provided in Section 3(a)(1)(A)(i) .

Other rights .

- Moral rights, such as the right of integrity, are not licensed under this Public License, nor are publicity, privacy, and/or other similar personality rights; however, to the extent possible, the Licensor waives and/or agrees not to assert any such rights held by the Licensor to the limited extent necessary to allow You to exercise the Licensed Rights, but not otherwise.

- Patent and trademark rights are not licensed under this Public License.

- To the extent possible, the Licensor waives any right to collect royalties from You for the exercise of the Licensed Rights, whether directly or through a collecting society under any voluntary or waivable statutory or compulsory licensing scheme. In all other cases the Licensor expressly reserves any right to collect such royalties.

Section 3 – License Conditions.

Your exercise of the Licensed Rights is expressly made subject to the following conditions.

Attribution .

If You Share the Licensed Material, You must:

- identification of the creator(s) of the Licensed Material and any others designated to receive attribution, in any reasonable manner requested by the Licensor (including by pseudonym if designated);

- a copyright notice;

- a notice that refers to this Public License;

- a notice that refers to the disclaimer of warranties;

- a URI or hyperlink to the Licensed Material to the extent reasonably practicable;

- indicate if You modified the Licensed Material and retain an indication of any previous modifications; and

- indicate the Licensed Material is licensed under this Public License, and include the text of, or the URI or hyperlink to, this Public License.

- You may satisfy the conditions in Section 3(a)(1) in any reasonable manner based on the medium, means, and context in which You Share the Licensed Material. For example, it may be reasonable to satisfy the conditions by providing a URI or hyperlink to a resource that includes the required information.

- If requested by the Licensor, You must remove any of the information required by Section 3(a)(1)(A) to the extent reasonably practicable.

Section 4 – Sui Generis Database Rights.

Where the Licensed Rights include Sui Generis Database Rights that apply to Your use of the Licensed Material:

- for the avoidance of doubt, Section 2(a)(1) grants You the right to extract, reuse, reproduce, and Share all or a substantial portion of the contents of the database, provided You do not Share Adapted Material;

- if You include all or a substantial portion of the database contents in a database in which You have Sui Generis Database Rights, then the database in which You have Sui Generis Database Rights (but not its individual contents) is Adapted Material; and

- You must comply with the conditions in Section 3(a) if You Share all or a substantial portion of the contents of the database.

Section 5 – Disclaimer of Warranties and Limitation of Liability.

- Unless otherwise separately undertaken by the Licensor, to the extent possible, the Licensor offers the Licensed Material as-is and as-available, and makes no representations or warranties of any kind concerning the Licensed Material, whether express, implied, statutory, or other. This includes, without limitation, warranties of title, merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, non-infringement, absence of latent or other defects, accuracy, or the presence or absence of errors, whether or not known or discoverable. Where disclaimers of warranties are not allowed in full or in part, this disclaimer may not apply to You.

- To the extent possible, in no event will the Licensor be liable to You on any legal theory (including, without limitation, negligence) or otherwise for any direct, special, indirect, incidental, consequential, punitive, exemplary, or other losses, costs, expenses, or damages arising out of this Public License or use of the Licensed Material, even if the Licensor has been advised of the possibility of such losses, costs, expenses, or damages. Where a limitation of liability is not allowed in full or in part, this limitation may not apply to You.

- The disclaimer of warranties and limitation of liability provided above shall be interpreted in a manner that, to the extent possible, most closely approximates an absolute disclaimer and waiver of all liability.

Section 6 – Term and Termination.

- This Public License applies for the term of the Copyright and Similar Rights licensed here. However, if You fail to comply with this Public License, then Your rights under this Public License terminate automatically.

Where Your right to use the Licensed Material has terminated under Section 6(a) , it reinstates:

- automatically as of the date the violation is cured, provided it is cured within 30 days of Your discovery of the violation; or

- upon express reinstatement by the Licensor.

- For the avoidance of doubt, the Licensor may also offer the Licensed Material under separate terms or conditions or stop distributing the Licensed Material at any time; however, doing so will not terminate this Public License.

- Sections 1 , 5 , 6 , 7 , and 8 survive termination of this Public License.

Section 7 – Other Terms and Conditions.

- The Licensor shall not be bound by any additional or different terms or conditions communicated by You unless expressly agreed.

- Any arrangements, understandings, or agreements regarding the Licensed Material not stated herein are separate from and independent of the terms and conditions of this Public License.

Section 8 – Interpretation.

- For the avoidance of doubt, this Public License does not, and shall not be interpreted to, reduce, limit, restrict, or impose conditions on any use of the Licensed Material that could lawfully be made without permission under this Public License.

- To the extent possible, if any provision of this Public License is deemed unenforceable, it shall be automatically reformed to the minimum extent necessary to make it enforceable. If the provision cannot be reformed, it shall be severed from this Public License without affecting the enforceability of the remaining terms and conditions.

- No term or condition of this Public License will be waived and no failure to comply consented to unless expressly agreed to by the Licensor.

- Nothing in this Public License constitutes or may be interpreted as a limitation upon, or waiver of, any privileges and immunities that apply to the Licensor or You, including from the legal processes of any jurisdiction or authority.

Creative Commons is not a party to its public licenses. Notwithstanding, Creative Commons may elect to apply one of its public licenses to material it publishes and in those instances will be considered the “Licensor.” The text of the Creative Commons public licenses is dedicated to the public domain under the CC0 Public Domain Dedication . Except for the limited purpose of indicating that material is shared under a Creative Commons public license or as otherwise permitted by the Creative Commons policies published at creativecommons.org/policies , Creative Commons does not authorize the use of the trademark “Creative Commons” or any other trademark or logo of Creative Commons without its prior written consent including, without limitation, in connection with any unauthorized modifications to any of its public licenses or any other arrangements, understandings, or agreements concerning use of licensed material. For the avoidance of doubt, this paragraph does not form part of the public licenses.

Rebecca Dekker

The Evidence on: Waterbirth

Originally published on July 8, 2014, and updated on February 14, 2024, by Rebecca Dekker, PhD, RN. Copyright Evidence Based Birth®. All Rights Reserved.

Please read our Disclaimer and Terms of Use . For a printer-friendly PDF, become an EBB Pro Member to access our complete library.

What is Waterbirth, and How is it Different than Water Immersion in Labor?

With water immersion in labor , you get into a tub or pool of warm water during the first stage of labor, before your baby is born. In a waterbirth , you remain in the water during the pushing phase and actual birth of the baby (Nutter et al., 2014a). The baby is then brought to the surface of the water after birth. With a waterbirth, the third stage of labor (when the placenta is born) may take place in or out of the water.

Researchers use the term land birth or conventional birth to refer to a birth in which the baby is born on dry land—not in a tub. And the word hydrotherapy can be used to describe the therapeutic use of water during labor and/or birth.

Waterbirth was first reported in an 1805 medical journal and became more popular in the 1980s and 1990s. The safety of water immersion during labor is well accepted (Cluett and Burns, 2018; Shaw- Battista, 2017). However, doctors and midwives, as well as health care professionals from various countries, often disagree on whether waterbirth is safe.

The purpose of this article is to provide you with the evidence on the safety and health outcomes of waterbirth. Then, we will share an overall summary of the pros and cons of waterbirth.

Before we dive into the evidence on waterbirth, it’s important to understand the impact that laboring in water—regardless of whether you give birth in the water—has on the labor process.

For example, one review of seven randomized trials with 2,615 participants looked at water immersion during labor (before normal land birth) and found that laboring in water posed no extra risks to birthing person or baby (Shaw-Battista, 2017). Water labor helped relieve pain, (leading to less use of pain medication), and led to lower anxiety, better fetal positioning in the pelvis, less use of medications to speed up labor, and higher satisfaction with privacy and the ability to move around.

By the very nature of waterbirth, a birthing person who births in water must also labor in water (for at least a few minutes, but sometimes for hours) prior to the actual waterbirth. Therefore, it is not possible to completely untangle the benefits of water immersion in labor from those of waterbirth. So, with this in mind let us now review what research has demonstrated about waterbirth outcomes.

Overview of Evidence on Waterbirth

In the early 2000s, the American Academy of Pediatrics released their first statement about waterbirth, in which they said: 1) there had not been research on waterbirth, 2) waterbirth posed only dangers for newborns, and 3) there were no benefits for mothers.

But the truth is that researchers from all around the world had been studying waterbirth for decades—and most of the research had found (and continues to find) that with low-risk births, the benefits of waterbirth greatly outweigh the risks.

Waterbirth research includes:

- Randomized, controlled trial s—participants are randomly assigned (like flipping a coin) to give birth in water or give birth on land, and their outcomes are compared.

- Observational studies —researchers enroll people in the study, measure if they have a waterbirth or not, and compare health outcomes. These studies can be prospective (meaning people were enrolled in the study before they gave birth and followed forward in time) or retrospective (meaning researchers look back in time at births that already happened).

- Meta-analyses and systematic reviews —researchers combine data from many randomized trials and/or observational studies to look for overarching trends.

- Qualitative research —researchers use patient interviews or written text to describe what it feels like to have a waterbirth.

- Case studies —each case study contains a report of a single bad outcome (usually a very rare outcome).

Randomized Controlled Trials on Waterbirth

There have been five randomized trials on waterbirth, and so far, they show that waterbirth benefits include:

- Lower pain scores.

- Less use of pain medication during labor.

- Less use of artificial oxytocin (also known as Pitocin®).

- Shorter labors on average.

- Higher rate of normal vaginal birth (birth without the use of forceps, vacuum, or surgery).

- Higher rate of intact perineum (meaning the tissue between the vagina and rectum remains untorn and uncut).

- Less use of episiotomy (a surgical cut to the perineum).

- Greater satisfaction with the birth.

Three trials looked specifically at the effects of giving birth in the water (water immersion was not used earlier in labor) (Nikodem 1999; Woodward & Kelly 1994; Chaichian et al. 2009), and two trials included laboring in water plus waterbirth (Ghasemi et al. 2013; Gayiti et al. 2015).

Table 1: Randomized, controlled trials of waterbirth

Unpublished Student Thesis

One of these trials is an unpublished student thesis from South Africa (Nikodem, 1999). In this study, 60 people were randomly assigned to waterbirth and 60 people to land birth. There was no water labor—participants assigned to waterbirth entered the pool at the start of the pushing phase. The researchers found that the waterbirth group was more satisfied with their birth experience (78% vs. 58%), and that more people who had waterbirths said the pain was less than they expected it to be (57% vs. 28%). They found no difference in overall trauma to the birth canal between groups. The researchers defined trauma to the birth canal as labial tears, perineal tears, or injury to the vaginal wall.

Small Trial with Too Much Crossover

The second trial took place in the United Kingdom (U.K.) (Woodward & Kelly, 2004). In this study, only 10 out of 40 people who were assigned to the waterbirth group actually gave birth in water. Since most people didn’t stay in their assigned groups (this is called crossover), we cannot draw any conclusions from this study.

Small Trial that showed Waterbirth Benefits

The third trial took place in Iran. The researchers assigned 53 people to waterbirth and 53 people to land birth (Chaichian et al. 2009). Everyone in the waterbirth group gave birth in water. The researchers did not find any differences in newborn outcomes, but they found quite a few differences in maternal health outcomes between groups.

Waterbirth led to:

- A higher rate of normal vaginal birth (100% vs. 79.2%)

- A shorter active phase of labor (114 minutes vs. 186 minutes)

- A shorter third stage of labor (6 minutes vs. 7.3 minutes)

- Less use of artificial oxytocin (0% vs. 94.3%)

- Less use of any pain medications (3.8% vs. 100%)

- A 23% lower rate of episiotomy

- A 12% higher rate of perineal tears (reporting that most were mild tears)

There were no differences between groups in the length of the pushing phase of labor or the rate of breastfeeding.

After this trial from Iran was published, two more randomized trials have come out on waterbirth—one from Iran and one from China.

Largest Randomized Trial so far with 200 Participants

A 2013 Iranian trial (Ghasemi et al. 2013) randomly assigned 100 people to waterbirth and 100 people to land birth, making it the largest randomized trial ever done on waterbirth. In the end, 83 people ended up staying in the waterbirth group and 88 people stayed in the land birth group. It’s not clear why people left the study. This study was published in Persian, and we were able to get details thanks to volunteer translators (Personal correspondence, Clausen and Basati, 2017).

The study found that birthing people randomly assigned to the waterbirth group (all of whom labored in water) had a lower chance of needing a Cesarean later in labor compared to the land birth group (5% versus 16%). Participants in the waterbirth group reported less pain than the land birth group, but the researchers did not give any details on how pain was measured.

There was less meconium (baby’s first stool) in the amniotic fluid with waterbirth (2% versus 24%) and fewer low Apgar scores with waterbirth compared to land birth. An Apgar score is a test of how well the baby is doing at birth. A low Apgar score means that the baby may require more medical assistance.

Another Randomized Trial found Benefits to Waterbirth

A study that took place in China (Gayiti et al. 2015) randomly assigned 60 participants to waterbirth and 60 participants to land birth. Everyone who was randomly assigned to the waterbirth group gave birth in the water.

The researchers did not find any differences in newborn health outcomes between groups, but they found several maternal health benefits to waterbirth. Compared to the land birth group, the waterbirth group had a higher rate of intact perineum (25% vs. 8%). The waterbirth group also had a much lower rate of episiotomy (2% vs. 20%), and lower pain scores. The total length of labor was also shorter in the waterbirth group, by an average of 50 minutes. They did not find any difference in the amount of blood loss between groups.

What are the Limitations of these Randomized Trials?

In all these trials, there was no evidence of harm from waterbirth. However, these studies were too small to tell differences in rare health problems. Researchers estimate that there would need to be at least 2,000 people in a waterbirth trial to see at least two rare events occurring (Burns et al. 2012). In one Australian study, only 15% of low-risk research participants said they would be open to being randomly assigned to a waterbirth or land birth (Allen et al. 2022). This means researchers would need to approach 13,000 laboring people to have the 2,000 needed for a waterbirth randomized trial.

Randomized, controlled trials are often considered to be the “gold standard” in research. But when studying an intervention like waterbirth, it can be very hard to carry out a large, randomized, controlled trial. Some birthing people feel very strongly about waterbirth and are not willing to be randomly assigned to waterbirth or land birth. Others may be assigned to have a waterbirth, but then must leave the tub early for some reason.

Because large, randomized trials are unlikely to be published in future due to these constraints, we must turn to other types of evidence about waterbirth. In observational (non-randomized) studies, researchers do not attempt to control who gives birth in the water versus on land, but they record where people choose to give birth and measure their health outcomes.

In the next section, we will look at large analyses where they combined data from randomized trials and observational studies.

Table 2: Meta-Analysis on Randomized Trials and/or Observational Studies on Waterbirth

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Since 2009, there have been seven systematic reviews or meta-analyses, where researchers combined research from randomized trials and/or observational studies on waterbirth. For a summary of their findings, see Table 2.

As time has gone on, researchers have been able to include more and more studies in these meta-analyses, giving us lots of information about the safety of waterbirth.

The largest, highest-quality, and most important review on waterbirth was published by Burns et al. in 2022. This review included 36 studies (25 of which examined waterbirths) from hospital and community birth settings from the year 2000 through 2021, resulting in 157,546 participants in the analysis.

The researchers found that laboring and/or giving birth in the water was associated with the following health results compared to no water immersion:

- Less use of Pitocin® to speed up labor.

- Less use of injectable opioids for pain management.

- Less use of epidurals.

- Reduced pain levels.

- Higher rates of intact perineum (positive outcome), but only in obstetric settings; in midwifery settings there were no differences between groups.

- Lower rates of episiotomy.

- Lower risk of postpartum hemorrhage.

- Lower rates of maternal infection.

- Higher rates of maternal satisfaction.

And there were no differences between the laboring and/or giving birth in water group vs. the standard care group with regard to:

- Rates of amniotomy (artificial breaking of the waters).

- Rates of Cesarean (but Cesarean rates were very low overall; average of 3.6%)

- Shoulder dystocia.

- Obstetric anal sphincter injury (3rd or 4th degree tears).

- Need for manual removal of the placenta.

- 5-minute APGAR scores.

- Need for newborn resuscitation.

- Transient fast breathing of the newborn.

- Newborn respiratory distress.

- Newborn death.

- Breastfeeding initiation.

There was a higher risk of the following with waterbirth:

- Cord avulsion (also known as snapping of the umbilical cord after birth, which we will discuss later).

Largest Observational Study on Waterbirth

One of the problems with observational studies is that unlike a randomized trial (when people are randomly assigned to groups), you can’t guarantee that people in the waterbirth group will have similar baseline characteristics to those in the land birth group. For example, it’s expected that people with complications will be asked to “get out of the tub” by the provider, or they might not be offered a water immersion in labor because of risk factors. As a result, waterbirth outcomes are usually better in observational studies—partly because people who end up birthing in water had uncomplicated childbirth experiences.

To address this problem, Bovbjerg et al. (2021) published the largest observational study on waterbirth ever, in which they studied 17,530 waterbirths and 17,530 land births that were matched for more than 80 factors (such as demographics, obstetric history, health conditions, and more). The process they used to match participants, called propensity scoring , resulted in the two groups being as similar as possible at baseline—except that one group was exposed to waterbirth, and the other was not. The researchers only included births that took place at home or in freestanding birth centers, not hospitals.