Wrightslaw Way

Special Education Law and Advocacy

Class Ratios: TEACHER TO STUDENT RATIOS IN SPECIAL ED CLASSROOMS

Catherine: Our high school just reduced the number of SPED classrooms, while cutting staff, and are adding more students. What is the legal limit for the amount of students they can put in a classroom, and how many adults do they need to have? I strongly believe they can’t meet FAPE with the way the classes are now arranged.

I work in a daycare, and I work in a classroom that is supposed to be for 1 1/2-year-old children. My ratio for my class is 9:1 (kids:teachers) and I have 3 autistic children in my class also. 2 out of the 3 is at the high-end of the spectrum. Me and the A.M. teacher have been pushing for another teacher to be with us throughout the day for about a year now because on top of those 3 autistic kids, we have 2 biters, and 4 kids that like to push and hit. Our directors don’t put our mental health first they put their needs before anything else. They’ve been firing staff left and right, getting new kids and now other kids are waitlisted and they complain about being understaffed. I want to know what the legal ratio for children on the spectrum is (no matter how mild the severity is) to teacher.

God bless all stressed and burnt out teachers out there.

A formal complaint was filed and upheld against my district for not offering a continuum of services and identifying service minutes based on school schedules. The remediation remedy has been to place students in a study skills class. They will receive math one semester and reading the next. Previous to the complaint, they were receiving 1 hour 15 minutes daily for each. The sped teacher in the study skills class is banned from accessing the IEP and from attending IEP meetings because she filed the complaint. Is this legal?

Federal rules (IDEA) say a parent can invite anyone to an IEP meeting that they feel can be of help. That would include this teacher. This is a question for your state education agency or special ed attorney. Your state parent training and information project, or disability rights office may also be of help. http://www.parentcenterhub.org/find-your-center

Hi, I have 19 students in self-contained 2nd grade classroom with 8 being on IEPs and a few others on 504’s with “push in” support of 1.15 hours a day- (when not pulled to sub., work on IEPs or attend meetings). Needless to say, it’s not a smooth year and I’m doing my best with trying to keep the kids progressing, however, I’m struggling as the they are “acting out” on me and each other. I know the ESE kids need mostly 1.1 instruction but can’t do it with being mostly alone with them throughout the day. What is the ratio for this type of “inclusion”?… or is it really a SPED class with lack of necessary support? Thank you

Hi Linda, Just now seeing this, so I hope you will receive the notification.

I am a special ed teacher in KY. I teach resource social studies, so it’s a 10:1 ratio and up to 11, if needed. After 11 students, I receive a stipend per diem for each student.

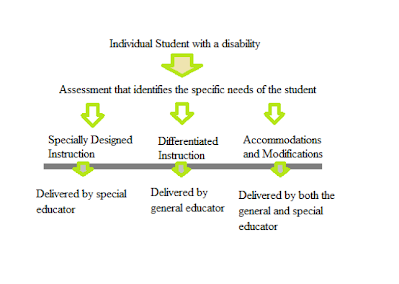

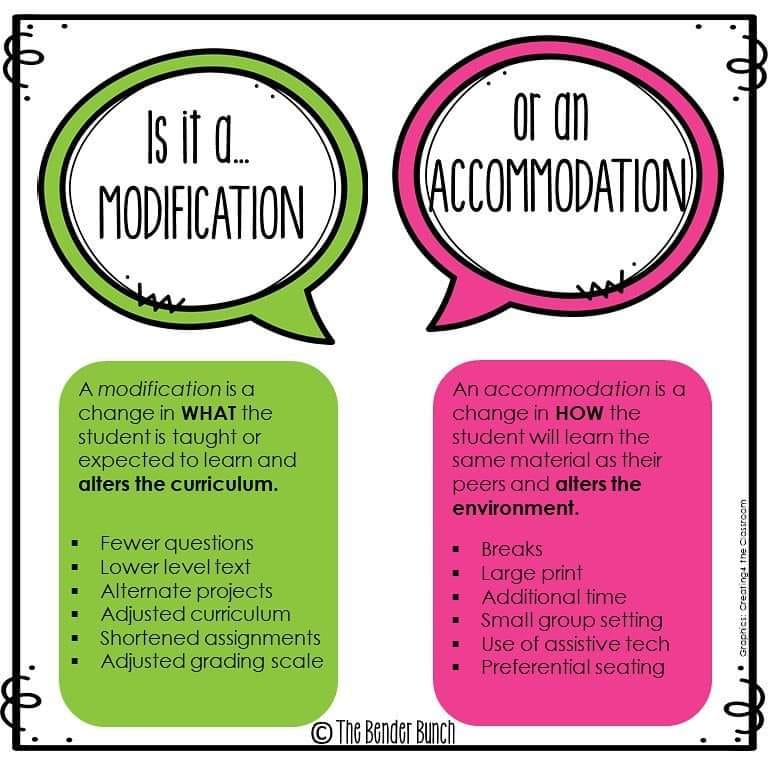

It sounds like you are in a co-teaching situation where you would have a special education teacher teach alongside you and give the federally mandated special education services your students with IEPs need. The ONLY one legally allowed to provide Specially Designed Instruction to your IEP kids is the certified special ed teacher!! No offense, unless you are certified to teach spec ed, you should not have the responsibility. No wonder you are feeling overwhelmed! You really need to check the LRE (least restrictive environment) on the IEPs. This explains in what learning environment the student will receive their services. Nowadays, it seems that ALL teachers have to provide accommodations and modifications to every student because of the fallout after the pandemic….ugh. I applaud your efforts.

First thing, read those IEPs!! Then find out the LRE and how many minutes they should receive on said service. That will tell you if you should really be teaching them. There are many special ed students totally,100% mainstreamed however, they should have in the very least, a caseworker monitoring and collecting data to report progress every six weeks! Find who this person is in your building. Hopefully, you’ll get the answers you need! Best of luck and let me know how it turns out, I hope that your situation has improved since last year.

Take care! Julia in KY

Is it legal to have middle and high school EBD students in a classroom together? I work at an alternative school in Kentucky and I feel as though having a 6th grader and a 10th grader in the same classroom together will not turn out well, especially when both students can be aggressive.

Is there a limit to the number of IEP students that can be assigned to one general education classroom teacher (in Ohio)?

Your state education agency, or parent training & information project would be the ones to ask.

In NYS. What is the percent of IEP students allowed in a general Ed class with only that general Ed teacher in it?

Lance, you need to check your state education regulations to find an answer. If this is covered, it is likely to vary from state to state.

IN FLORIDA?

You need to research the class ratio issues in your state. As Chuck suggested, your state Parent Training Info (PTI) Center can help. This page has links to all PTIs: https://www.parentcenterhub.org/find-your-center/

Is it legal to have grades k-6 in one contained special education classroom?

That would depend on state laws, and rules. Depending on the impact on individual students, it could be a violation of FAPE.

The legal question is whether each child in this K-6 self-contained classroom is receiving a free appropriate education that is tailored to the child’s unique needs. Hard to imagine that this is possible.

If there are 120 students in 4 classrooms, how many students are there in 1 class room. (Hint: think proportions)

30 and 29 of the students are in special education. By putting the one general education student in the class they can call it co-taught.

what if there is no coteacher in the class. How many speds can be in a collaborative setting or monitored setting before another teacher or aid needs to be in the class

If there is a limit, it would be set by the state education agency.

30. Are you asking how many kids are in a special education classroom or a general education class?

I will be starting my transition class (18 to 21 year olds) next fall with 21 students. They cognitively range from 31 year to almost at level. 2 have severe behavior issues, 1 parent who sues the district and accuses teachers constantly, several need toileting and feeding and we’re supposed to have them out in the community in job experiences. I can’t even imagine how I can give any of these students the help they need, which makes me feel terrible. Are there any limits or help I can get.

I suggest starting with the campus, & district special ed leadership. IEPs can & should list the supports staff need to implement it. Ask to meet with staff who are knowledgeable of transition in general, staff who are knowledgeable of these students. Nationally, & probably at the state level their should be information on transition. Also explore what is available thru the state vocational agencies.

I co-teach in a CWC with an excellent special ed teacher. Each year, though, the counselors are putting more and more students with IEPs in our class. This year, we have 63% of the students in the CWC with IEPs. Does anyone know if there is a Missouri law/standard for the ratio of reg ed students to those with IEPs?

24% of my classes are listed as needing Special Education services. What are the best practices for me to teach them successfully in a Foreign Language classroom?

IDEA rules say that the IEP must address the supports that the staff need to implement the IEP, & its goals. If that is not happening, you can request that the district provide help to learn best practices.

Esteban, Chuck’s advice is good.

We have an article on Wrightslaw about this: “Support For School Personnel and Parent Training: Often Overlooked Keys To Success” is at https://www.wrightslaw.com/advoc/articles/support.bardet.htm

If you share the article with your supervisor and/or principal, you may get the support you need.

I teach in Georgia. I am the regular education teacher with a co-teacher in all my classes. Some of my classes have more special education students than regular education students. Is there a ratio of regular ed students to special ed students that constitute inclusion? I feel that with classes that are heavy with special education students, more so than regular education students, is illegal according to IDEA. I’m not sure of the law so I want to double check before I question. For example, one of my classes has 12 special education students and 6 regular education students.

Many districts in GA have waivers for class sizes and I believe most co-taught classes are like you described (more special education students than general education students). It’s not helpful for any student but because of the waivers with the state, they seem to be able to get away with it.

This is two years later, but I am a high school ELA teacher, and I have an English III class with 15 IEPs and 7 gen ed students. I don’t think that’s fair to the students.

Is there a law prohibiting general ed students with no Iep to attend a resource room with special ed students?

Regular education students should never be a special education classroom. Part of an IEP states this and when a parent signs, they are agreeing their students can be in a special education classroom.

IDEA, the federal special ed law, does not address the issue of general ed students in a resource room where kids with IEPs go to get special education services.

Do you know — for a fact — that general ed students are going to a resource room although they don’t have IEPs and don’t receive special ed services?

Using “incidental benefit” I have been taught the students with an IEP can access the instruction occurring within a sped setting if it’s something they need and “there is room”

What is the legal amount of student with disabilites in a mild/mod classroom to adult ratio in a public school in California? Thank you!

I work in a California middle school as a paraprofessional with 4 Special Ed students who fall under my responsibility. We have no SDC teacher or classroom at this school. Is this illegal? Is the school out of compliance?

Your state education agency would have to answer that, if the district or teacher associations won’t tell you.

I am a middle school art teacher with general education classes. Some of my classes have rosters of 34 and 35 learners including self-contained students with no aide. Last year our district Art Office required an increase in reading in Art. This year our district Art Office requires that we increase writing in Art classes. I feel bad that I have been unable to meet my wonderful students’ unique needs. I recognize that IDEA’s erroneous classification of visual art as “non-academic” caused these incorrect policies to be adopted. I had hoped ESSA would help art education but my class size has increased and all aide support has disappeared since it was passed. Unfortunately, our union is not allowed to discuss class size, I am told. Is there any other suggestion to correct rostering policies?

In such situations like this I feel that the best approach is to focus on the situation at your campus with your student & not district policies. You can try to find supporters at your campus & community to develop a plan to improve the situation for your students. Are parent volunteers allowed on your campus?

It’s so disappointing that we all seem to be in different levels of the same boat. I have 27 special education students at this time. Collectively, they have 10 hours of resource minutes included in their IEPs and I have six hours of possible classroom time to support them. My schedule overlaps so much that some students are only receiving assistance from me for 10-15 minutes each day, regardless of the fact that their IEPs require 30-90 minutes of resource help each day. I am fortunate that I have four paraprofessionals who cover all of the inclusion minutes that are on top of the students’ resource minutes. Power on, friends, and know that you do make a difference even if no one acknowledges it!

I am literally in the same boat! I had 27 now 29. I am fortunate enough if I even get to spend a full 15 minutes with them. How do you handle this if you don’t mind me asking. Love to pick your brain!

Not every state education agency has rules or laws regarding this. Other sources of “caseload limits” or “class size” may be in the teacher’s or classified staff’s collective bargaining agreements. And it’s also important to remember, ratios may reflect “best practices” advisories from the state education agency, but not be actual citations of law.

There are legal limits to the number of special education students per teacher or aide as well as legal limits to classroom totals. These ratios are determined by the students’ placement.

Andrea, The student-teacher ratios are usually different from one state to another. In most if not all states, the ratios are determined by the State Department of Education. Many states give guestimated student-teacher ratios so it can be next to impossible to get a firm number.

From everything I have read, there are no laws protecting special day class teachers for classroom or caseload. CA has recommendations from the SELPA and everything else, in our district anyway, is negotiated to amend our contract. I sent a letter to the state because I was providing all our resource services and special day class simultaneously. The state is aware this SHOULD be addressed, but still nothing has been done.

Is there a law for teacher to student ratio for kindergarten? I have 2 students width Down syndrome and one with autism makes a total of 19 without any one on one teachers aid or no help.

Is there a law i ref/ to the total class load limit for a teacher in sp. ed for SC? I have no more than 8 per class but I have a total of 37. Austistic spectrum and LD and ADHD. TY

In Ca resource teachers cannot have more than 28 unless the district files a waiver, which requires more aide support and the Ed specialist is to agree to the terms, more than 32 is never allowed in a resource specialist’s caseload

Is 28 student limit this for elementary, middle, or high school?

I teach preschool, I have 20 students in my classroom. I currently have 4 IEP’s with another 3 who are being evaluated and will also qualify. My question is how many students can be in a classroom, how many children total and then how many IEP’s?

If there is a rule on this, it would be made by your state education agency. They or teacher associations should be able to tell you.

this year at our school all of the special needs students in the middle school have the same schedule, some of the day they are with a special ed teacher which is fine but the classes (science, social studies, etc) that they are not i they have one para for all of the students. Is this legal?

Depending on their IEP, maybe. If the IEP says co-taught for the full segment for 5 days a week then a special education teacher needs to be in there. However, if the IEP only says co-taught for a smaller amount of time, then a para is legal. Many students don’t need specialized instruction for the whole time and a para is an excellent option for the remainder of the time.

When I started the school year, I had 23 students on my caseload, but now I have 38. I know that is 10 over the limit, but I also want to point out that there are 65 students on our campus, and I have over half of those students whereas the other teachers have less than 30 altogether. If they are not going to provide any assistance, should I be paid more? I think the only reason they are doing this is that the district was just sued for over 800K for an issue not related to Special Education

Does California have a law that limits the number of students with IEPs in a general education classroom? Is there a ratio of gen Ed v special Ed students that if reached the class is no longer a gen Ed class?

We are in a teacher shortage crisis at my school in TN. I am not doing the job I was hired for because their was not a low incidence teacher hired. I am the only teacher right now that can write IEP’s which means, I am expected to case manage low incidence and inclusion, and we are getting new students everyday needing an IEP in 30 days. that will put me well over 40 students alone. Is this legal to put teachers in this situation?

hello, what is the maximum number of students with IEPs allowed in a resource class room in Michigan

what is the ratio for integrated special ed classroom between teacher and aid in california

middle school life skills unit i have 10 students 2 on wheel chairs 4 on diapers 3 runners some attend class with para assistance weekday is the ratio

In the state of texas

What is the teacher to student ratio needed for an aide in a special education classroom in Illinois?

I teach in Arizona. I have a class of 26 students with 15 classified as special needs or on an IEP. There is no way to partner up helpers and I don’t have any aides or para support. My question is there a law that says what percentage of the class can be special education. There are 3 other classrooms that the students can be split evenly but because the district cut support they put them all in one room and then provided me with NO support.

I need the same information for the state of Florida

Did you ever get an answer?

I have 38 students 14 ESE and the rest Esol level 1 and reading levels at 1… I have 5 classes with high numbers and my 6th class with 14 Resource Autistic… I leave work tired and my back on fire. What has education become?

Hi. In Virginia, can anyone tell me how many SPED students must a school have to get one full time SPED teacher? For example, let’s say you have students from varying mild disability areas such as LD, ED, OHI, and maybe one ID. If you have a small class size, can you get a full-time teacher or would you have to settle for a part-time teacher?

Google “how many special education students are needed to earn state funding in VA” These resources sound like they will answer your question. You can also contact the state education agency.

Hi. I am a special ed teacher in NYS. I have a class ratio labeled 12:1:2. Are two TAs still required if I have less than 12 students?

In Missouri it seems self contained classrooms at the elementary level can have a 9:1 ratio of students to teacher. We are moving to get rid of the self contained classroom by moving to class with a class/Co teaching system. However, the numbers of LD students in the regular ed classroom is going up. Is there a limit of IEP students that can be in the COTeaching Classroom, as their is in the self contained class?

How many students with IEP’s can a general education class have before it no longer is considered a general education setting?

That would be based on the state’s rule. Some states have no rule on this.

Where would I find this for Florida?

It may be on the FL dept of Ed website, but you might need to call them or your state parent training and information project should know. http://www.parentcenterhub.org/find-your-center

I am a self-contained primary specialized learning disability teacher in Nevada. I have 15 students in my class and no aid. Is this legal? My admin has not hired anyone even though they have known since August that there is no aid for this class.

That is considered a 15:1 and it is totally legal as long as the students IEP says they are to be in a 15:1. If it says 12:1:1 or 6:1:1, then there should be an aid.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Chapter Leader Hub Overview

- Chapter Leader Update Archives

- Involving your members in legislation and political action

- Using the Chapter Leader Update to expand your chapter newsletter

- Due process and summons

- How to Read a Seniority List

- Our Contract in Action

- Request a school visit

- SBO Guidance

- Training Materials 2022

- Consultation

- Consultation committees

- Inviting guest speakers to chapter meetings

- Roles, rights and responsibilities

- APPR complaint

- Key arbitration awards

- Other types of grievances

- School reorganization grievances

- The grievance procedure

- News for chapter leaders

- Paperwork & operational issues

- Professional conciliation

- Safety and health

- Article 8C of the teachers' contract

- Chapter Leader Hub

- Chapter News

- Chapter Calendar

- Dues Information

- Health Benefits

- Newsletters

- Retirement Plans

- About the Chapter

- About The Chapter

- Chapter Updates

- Representatives

- You Should Know

- Chapter Representatives

- Hospital Schools

- Acid neutralization tanks

- Chemical Removal

- Dissection practices

- Duties of the Lab Specialist

- Evaluating lab procedures

- Evaluations

- Fire extinguishers

- Flammable and combustible liquids

- Hours of the lab specialist

- How toxic is toxic?

- Lab safety rules for students

- Mercury removal

- Minimizing hazards

- Purchasing Q&A

- Safety shower Q&A

- Spill control kits

- Using Classrooms

- Hourly Rate

- Leap to Teacher

- Certification

- Re-Start Program

- Sign up for UFT emails

- School counselor hours

- Contract History

- DOE Payroll Portal H-Bank access

- Protocol For Influenza-like Illness

- Joint Intentions and Commitments

- Article One — Recognition

- Article Two — Fair Practices

- Article Three — Salaries

- Article Four — Pensions

- Article Five — Health and Welfare Fund Benefits

- Article Six — Damage or destruction of property

- Article Seven — Hours

- Article Eight — Seniority

- Article Nine — Paid Leaves

- Article Ten — Unpaid Leaves

- Article Eleven — Safety

- Article Twelve — Excessing, Layoff, Recall and Transfers

- Article Thirteen — Education Reform

- Article Fourteen — Due Process and Review Procedures

- Article Fifteen — Complaint and Grievance Procedures

- Article Sixteen — Discharge Review Procedure

- Article Seventeen — Rules and Regulations

- Article Eighteen — Matters Not Covered

- Article Nineteen — Check-Off

- Article Twenty — Agency Fee Deduction

- Article Twenty One — Conformity to Law - Saving Clause

- Article Twenty Two — No Strike Pledge

- Article Twenty Three — Notice – Legislation Action

- Article Twenty Four — Joint Committee

- Article Twenty Five — Charter Schools

- Article Twenty Six — Duration

- Appendix A — New Continuum Dispute Resolution Memorandum

- Appendix B — Pension Legislation

- Appendix C — False Accusations

- Licensing and per session

- Newsletters & Meeting Notes

- Speech Chapter Lending Library

- Better Speech and Hearing Month

- You Should Know/Key Links

- Speech Memorandums of Agreement

- Our contract

- Salary schedule

- Frequently Asked Questions

- About the ADAPT Network Chapter

- Just for Fun

- UFT Course Catalog

- Birch Family Services Chapter Representatives

- Course Catalog

- About the Block Institute

- Just For Fun

- Why Unionize?

- Join the UFT now!

- Our History

- Informal (legally-exempt) Provider Rights

- Executive Board

- Provider Grant program offerings

- Share with a friend

- Preguntas Frecuentes

- Provider Wellness text messaging

- Retirement Plan

- Bureau of Child Care Borough Offices

- Bloodborne Pathogens

- Fire Safety

- Know Your Regs: 10 Common DOH Violations

- Prevent Child Abuse

- Safety Tips

- Information for Parents

- DOH protocol

- Helpful tips to avoid payment problems

- How To Obtain A License

- How to renew a license

- Know Your Regs

- Tax Credit Help for Providers

- Tax Guide For Providers

- What to do if you have a payment problem

- About the chapter

- Prescription Drugs

- Chapter news

- Federation of Nurses/UFT Contracts

- Charter Schools

- A Brief History of the Chapter

- Resources for School Security Supervisors

- What is Workers’ Compensation?

- What to Do If You Are Hurt on the Job

- Workers’ Comp Forms for School Security Supervisors

- Join the RTC

- Fifteen benefits of the RTC

- RTC Meeting Minutes

- RTC Newsletters

- RTC Election 2024

- Retired Paraprofessionals Support

- Contacts for UFT retirees

- Outreach sections

- UFT Florida

- Pension benefits

- Retiree health benefits

- Day at the University

- Reflections in Poetry and Prose

- Si Beagle Course Corrections

- Si Beagle Learning Center locations

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Community Partners

- Events calendar

- At Your School

- In the School System

- Great Outings for Parents and Children

- Making the Most of Parent-Teacher Conferences

- Parent Calendar

- Sign up for Emails and Texts

- Advocacy and disability organizations

- Special Education Resources

- Dial-A-Teacher

- Be BRAVE Against Bullying

- Sign up for text alerts

- Carbon Free and Healthy Schools

- Dromm Scholarship in Memory of Patricia Filomena

- Gun violence resources for educators

- Research on school shootings

- Budget cuts by City Council district

- Enrollment-based budget cuts

- Fix Tier Six

- Small class size FAQ

- Support 3-K and pre-K

- UFT Disaster Relief Fund

- New Member Checklist

- Political Endorsements

- UFT 2024 city legislative priorities

- UFT 2024 state legislative priorities

- UFT Lobby Day

- Contact your representatives

- Art Teachers

- English Language Arts

- Foreign Language Teachers

- Humane Education Committee Board

- Humane Education Committee Newsletters

- A Trip to the Zoo

- Elephants in the Wild and in Captivity

- Humans and the Environment

- Monkeys and Apes

- Pigeons in the City

- Whales and Our World

- Alternatives to Dissection in Biology Education

- Animals Raised on Farms

- Award-Winning Student Projects

- Endangered Animals and the Fur Trade

- High School Students' Attitudes Toward Animals

- Projects in Progress

- Research that Advances Human Health Without Harming Animals

- The Great Apes

- The Study of Natural Insect Populations

- Toxic Substances and Trash in Our Environment

- Viewing of Wildlife in Natural Habitats

- Math Teachers Executive Board

- Committee Chair Bio

- Physical Education

- Social Studies Committee Executive Board

- African Heritage

- Albanian American Heritage

- Asian American Heritage

- Caribbean (Caricomm)

- Hellenic American

- Hispanic Affairs

- Charter for Change

- Italian American

- Jewish Heritage

- Muslim Educators

- Applying for a Reasonable Accommodation

- Capably Disabled FAQ

- Capably Disabled Useful Links

- Climate & Environmental Justice

- Divine Nine

- UFT Players Executive Board

- Women's Rights

- UFT student certificates

- Latest news & updates

- UFT programs & services

- AAPI Teaching Resources

- Black History Month

- Celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month

- Climate education teaching resources

- Juneteenth Curriculum Resources

- Pride Teaching Resources

- Teaching about race and social justice

- Women's History Curriculum Resources

- World AIDS Day

- Background information

- Educator and community voice

- Supporting all learners

- Class trips

- Funding classroom projects

- Inside My Classroom

- Instructional planning

- Learning Curve

- Linking to Learning

- Google Classroom Tutorials

- Middle school

- High school

- Multilingual learners

- Special education

- Online activity builders

- Teacher To Teacher

- ELL Complaint Form

- Tips for newly-arrived ELLs

- Commonly used terms

- Appeal ineffective rating checklist

- For your records

- Measures of Student Learning

- Measures of Teacher Practice

- Teachers covered by Advance

- The S / U system

- The first 90 days

- Jobs for current members

- Prospective applicants

- Transfer opportunities

- New Teacher To-Do List

- Professional growth

- FAQ on city health plans

- Paraprofessionals

- Functional chapters

- Staying connected

- Your school

- New Teacher Diaries

- New Teacher Profiles

- New Teacher Articles

- Elementary School

- Social Workers

- CTLE requirements

- Course Catalog Terms & Conditions

- Mercy College

- New York Institute of Technology

- Touro University

- Graduate Education Online Learning

- Undergraduate College Courses

- Identification and Reporting of Child Abuse and Maltreatment/Neglect Workshop

- Needs of Children with Autism

- Violence and Prevention Training

- Dignity for All Students

- Introducing Professional Learning

- Designing A Professional Learning Program

- Professional Book Study

- Lesson Study

- School Librarians

- What's New

- Jan/Feb 2024 P-Digest posts

- Mar/Apr 2024 P-Digest posts

- Nov/Dec 2023 P-Digest posts

- Sept/Oct 2023 P-Digest posts

- Chancellor’s Regulations

- 2023 compliance updates

- DOE Resources

- District 75 Resources

- Federal Laws, Regulations and Policy Guidance

- Amending IEPs

- Copies of IEPs

- Special Education Intervention Teacher

- Class composition

- Collaboration

- Interim SETSS

- Class ratios & variances

- Service delivery

- Know Your Rights

- Program Preference and Special Ed

- Direct and indirect services

- Minimum and maximum service requirements

- Group size, composition and caseload

- Location of services

- Functional grouping

- Arranging SETSS services

- Interim SETSS services

- District 75 SETSS

- File a complaint online

- Special education teacher certification

- Staffing ratios

- Support services part-time

- Research and best practices

- State laws, regulations & policy guidance

- Student discipline

- Guidance from 2022-23

- Academic & Special Ed Recovery

- Principals Digest items

- Career and Technical Education

- Questions or Concerns

- Around the UFT

- Noteworthy Graduates

- Today's History Lesson

- National Labor & Education News

- Awards & Honors

- Chapter Leader Shoutout

- Member Profiles

- New York Teacher Archive

- Editorial Cartoons

- President's Perspective

- VPerspective

- Press Releases

- RTC Chapter Leader Column

- RTC Information

- RTC Second Act

- RTC Section Spotlight

- RTC Service

- Serving Our Community

- Field Trips

- Linking To Learning

- For Your Information

- Grants, Awards and Freebies

- Know Your Benefits

- Q & A on the issues

- Secure Your Future

- Your well-being

Special class staffing ratios

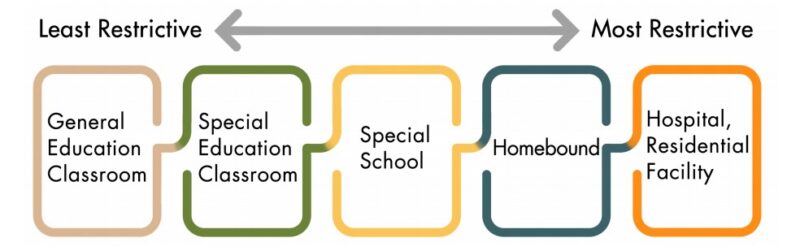

Special classes offer different levels of staffing intensity depending upon the intensity of a student's academic and/or management needs. Special class maximum sizes may range from six to 15. Staffing for classes will be one teacher and up to four paraprofessionals. Students recommended for a more intensive student to staff ratio require more intensive and constant adult supervision to engage in learning. When a student is recommended for special class services, the IEP must state the number of students who will be in the class and the specific ratio of special education teachers and paraprofessionals.

Special Class Staffing Ratio 12:1 (elementary and junior/middle levels in NYC only) and 15:1 (high school)

- no more than 12 or 15 students per class depending on level

- one full-time special education teacher

Serves students whose academic and/or behavioral needs require specialized/specially designed instruction which can best be accomplished in a self-contained setting.

Special Class Staffing Ratio 12:1:1

- no more than 12 students per class

- one full-time paraprofessional

Serves students whose academic and/or behavioral management needs interfere with the instructional process, to the extent that additional adult support is needed to engage in learning and who require specialized/specially designed instruction which can best be accomplished in a self-contained setting.

Special Class Staffing Ratio 8:1:1

- no more than eight students per class

Serves students whose management needs are severe and chronic requiring intensive constant supervision, a significant degree of individualized attention, intervention and intensive behavior management as well as additional adult support.

Special Class Staffing Ratio 6:1:1

- no more than six students per class

Serves students with very high needs in most or all need areas, including academic, social and/or interpersonal development, physical development and management. Student's behavior is characterized as aggressive, self-abusive or extremely withdrawn and with severe difficulties in the acquisition and generalization of language and social skill development. These students require very intense individual programming, continual adult supervision, (usually) a specific behavior management program, to engage in all tasks and a program of speech/language therapy (which may include augmentative/alternative communication).

Special Class Staffing Ratio 12:1:4

- one additional staff person (paraprofessional) for every three students

Serves students with severe and multiple disabilities with limited language, academic and independent functioning. These students require a program primarily of habilitation and treatment, including training in daily living skills and the development of communication skills, sensory stimulation and therapeutic interventions.

Upon application and documented educational justification to the State Education Department, approval may be granted to exceed the special class sizes. The class size may not be exceeded unless and until the State Education Department grants the variance.

- State Regulations: 8 NYCRR § 200.6(h)

- DOE Continuum of Special Education services - (Also can be found on DOE Info Hub - login required to access )

- Meet Our Staff

- Privacy Practices

Dr. Laurie H.C. Philipps & Associates We are a Family Practice that provides solutions for children, adolescents, and adults. School Consultation and Advocacy is our strength.

(847) 558-6986

- Neuropsychological Testing for Adults

- Pediatric Neuropsychological Testing

- Forensic (Legal) Assessments

- ADHD Testing

- OCD Treatment

- Dyscalculia (Mathematics Learning Disorder)

- Learning Disorder (Written Expression)

- Executive Dysfunction

- Trauma and Abuse

- Learning Disorder (Reading)

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder/Conduct Disorder

- Couples Counseling

- Behavioral Parental Training

- School Consultation & Advocacy

- School Accommodations

- IEPs and 504 Plans

- SAT/ACT Extended Time

- Accommodations for College Students

- College Application and Admissions Consulting

- Academic Probation Advocacy

- Concussion Assessment

- Pediatric Concussion Assessment

- TBI Assessment

- Biofeedback

0 comments

How Many Students With IEPs Can Be in a Regular Classroom?

By NeuroHealth Arlington Heights

February 3, 2021

As school starts and students settle into their routines, teachers take the time to learn about each of their students. This includes monitoring behaviors, noting progress or lack of progress on assignments, and reading data from standardized assessments. For some teachers, it may be time to reassess students in order to make decisions about placement for those with special needs .

One of the options for specialized instruction of students with special needs is to keep them in the regular education classroom either with or without a special education co-teacher. What is the allowed ratio of students with special needs to regular ed students? Does it change if there is a co-teacher present? NeuroHealth Arlington Heights invites you to learn more about the IEP (individualized education plan) process, placement options for special education students, and how a robust co-taught classroom may be the best option for some students with special needs.

What Is an IEP?

An IEP is an educational plan that’s put in place for students who have been identified with a disability that impacts their education. The educational plan consists of annual goals, supplementary aids and services, related services, times for specialized instruction, and present levels of performance.

A team that must consist of a regular education teacher, parent/guardian, an LEA (local education agency, generally a school administrator), and a special education teacher meets annually to discuss the strengths and concerns in regards to that student. Based on the input from every team member and the data collected, the team will formulate an educational plan for that student.

Contact Us Today

What Is Specialized Instruction?

Specialized instruction is instruction provided to students with disabilities . This instruction can adapt the methodology, delivery, or content a teacher uses to help disabled students have equal access to the regular education curriculum. Some students require specialized instruction in order for them to make progress and close the gap in their education. Without this specialized instruction, they could potentially fall further behind their peers.

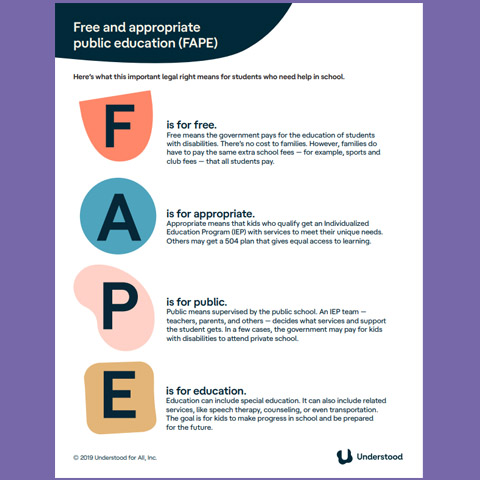

Students with disabilities can receive specialized instruction in many different ways, including in the general education classroom with proper support and modifications or accommodations, using check-ins and check-outs, through a resource room, in a co-taught classroom, in a special education classroom, at a separate school, within a residential facility, or in a homebound or hospital setting. The IEP determines the least restrictive environment for the child to receive the specialized instruction they need to make educational gains and close the gap between a general education student and the student with special needs.

What Is a Co-Taught Classroom?

A co-taught classroom consists of a general education teacher and a special education teacher delivering instruction together in a general education classroom. In this type of setting, it’s the responsibility of both teachers to plan instruction, know every student’s needs, share responsibilities and roles, and implement learning opportunities for all students. This method of teaching can be very impactful if implemented with integrity.

How Many Students With IEPs Should Be in a General Education Classroom?

The number of students in a classroom will vary. Ideally, a smaller class size is always preferable. In a typical classroom, the number of students ranges from 15 to 22 with one general education teacher. In a special education classroom where students receive specialized instruction in a small group setting, class sizes typically range from 3 to 10 students. This classroom will have one special education teacher and possibly a paraprofessional. Class size can change when providing specialized instruction in the general education setting for students with IEPs.

In a typical classroom setting, the rule of thumb is to have no more than a 70/30 split between students with and without disabilities. This rule is a guideline. In some cases, it may be as close to a 50/50 split. The students with disabilities in these classrooms may or may not be pulled out to receive specialized instruction throughout the day. The needs of the students should be the determining factor in how many students with IEPs are in a general education classroom with no support.

Students with disabilities will stay in the general education classroom and receive their specialized instruction from special education and regular education teachers. In this type of co-taught classroom setting, the number of students with IEPs could be slightly higher. However, it’s important to have a good mix of students. This allows some students to act as role models or leaders for those students who might struggle in certain areas.

With two teachers in the general education classroom, it’s possible to increase the total number of students, but closely maintaining the 70/30 split is ideal. Again, the needs of the students should determine how many students with an IEP are in the co-taught classroom.

Why Should a Student With an IEP Be in the General Education Classroom?

Students who have a disability have the right to a free and appropriate public education in a nonrestrictive environment. This means that a student with a disability should be placed with their same-aged peers as much as possible but still have their educational needs met. Students with disabilities can bring a new perspective to the classroom, and they learn so much from their peers who model appropriate behavior and academic readiness.

Peers that do not have a disability can also learn from their peers who have a disability. They can learn how to interact with them appropriately and better understand who they are as a person. Having the opportunity to have a child with an IEP be a part of the general education setting can be a powerful thing, especially when a dynamic co-teaching environment is established.

The number of students with an IEP in a general education classroom can vary between school districts and states. You’ll want to use caution when more than 30% of the class comprises students with an IEP. If the numbers are too high, all students could potentially suffer, as their educational needs may not be met. Sticking to the 70/30 split is a highly recommended guideline.

If you feel your student could benefit from the specialized instruction of an IEP and aren’t sure where to start, contact the experts at NeuroHealth Arlington Heights or call us at ( 847) 754-9343. School consultation and advocacy are our strengths, regardless of age or ability.

Schedule A Consultation

NeuroHealth Arlington Heights

About the author

For over 20 years, NeuroHealth Arlington Heights has been offering neuropsychological and psychological assessments and treatments for people of all ages. These assessments and treatments address Behavioral, Emotional, & Social Issues, Neurocognitive Functions, and Neurodevelopmental Growth.

Sorry, we did not find any matching results.

We frequently add data and we're interested in what would be useful to people. If you have a specific recommendation, you can reach us at [email protected] .

We are in the process of adding data at the state and local level. Sign up on our mailing list here to be the first to know when it is available.

Search tips:

• Check your spelling

• Try other search terms

• Use fewer words

Student-to-teacher ratio, public schools

The student-to-teacher ratio is equal to the number of students who attend a school divided by the number of teachers in the school. In public schools, the ratio has hovered around 16 students for every teacher in the past two decades.

Data Adjustments

How much does the government spend on education?

Related Metrics

Preprimary enrollment

4.39 million

K-12 enrollment

56.28 million

Public School Staff

6.63 million

Explore Student-to-teacher ratio, public schools

Interact with the data, state display, sign up for the newsletter, data delivered to your inbox.

Keep up with the latest data and most popular content.

TEACHER/STUDENT RATIO IN SPECIAL EDUCATION CLASSES

WHEREAS, special education is an individualized instructional system; and

WHEREAS, the special education instructor must evaluate all of the pupils assigned to his/her class on an individual basis; and

WHEREAS, the special education instructor must provide the teaching and non-teaching personnel with the appropriate information and materials necessary for proper instruction; and

WHEREAS, the decrease of one or more pupils does not diminish the total instructional operation involved:

RESOLVED, that the AFT strive to have the special education teacher/student ratio remain the same when a teaching assistant and/or other personnel is assigned to the classroom or to an individual students/students within the instructional framework of special education.

Please note that a newer resolution, or portion of a resolution, may have superseded an earlier resolution on the same subject. As a result, with the exception of resolutions adopted at our most recent AFT convention, resolutions do not necessarily reflect current AFT policies.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Campbell Syst Rev

- v.19(3); 2023 Sep

- PMC10346380

The effects of small class sizes on students' academic achievement, socioemotional development and well‐being in special education: A systematic review

Anja bondebjerg.

1 VIVE—The Danish Centre for Social Science Research, Copenhagen Denmark

Nina Thorup Dalgaard

Trine filges, bjørn christian arleth viinholt, associated data.

Class size reductions in general education are some of the most researched educational interventions in social science, yet researchers have not reached any final conclusions regarding their effects. While research on the relationship between general education class size and student achievement is plentiful, research on class size in special education is scarce, even though class size issues must be considered particularly important to students with special educational needs. These students compose a highly diverse group in terms of diagnoses, functional levels, and support needs, but they share a common need for special educational accommodations, which often entails additional instructional support in smaller units than what is normally provided in general education. At this point, there is however a lack of clarity as to the effects of special education class sizes on student academic achievement and socioemotional development. Inevitably, such lack of clarity is an obstacle for special educators and policymakers trying to make informed decisions. This highlights the policy relevance of the current systematic review, in which we sought to examine the effects of small class sizes in special education on the academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being of children with special educational needs.

The objective of this systematic review was to uncover and synthesise data from studies to assess the impact of small class sizes on the academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being of students with special educational needs. We also aimed to investigate the extent to which the effects differed among subgroups of students. Finally, we planned to perform a qualitative exploration of the experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education.

Search Methods

Relevant studies were identified through electronic searches in bibliographic databases, searches in grey literature resources, searches using Internet search engines, hand‐searches of specific targeted journals, and citation‐tracking. The following bibliographic databases were searched in April 2021: ERIC (EBSCO‐host), Academic Search Premier (EBSCO‐host), EconLit (EBSCO‐host), APA PsycINFO (EBSCO‐host), SocINDEX (EBSCO‐host), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (ProQuest), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), and Web of Science (Clarivate, Science Citation Index Expanded & Social Sciences Citation Index). EBSCO OPEN Dissertations was also searched in April 2021, while the remaining searches for grey literature, hand‐searches in key journals, and citation‐tracking took place between January and May 2022.

Selection Criteria

The intervention in this review was a small special education class size. Eligible quantitative study designs were studies that used a well‐defined control or comparison group, that is, studies where there was a comparison between students in smaller classes and students in larger classes. Children with special educational needs in grades K‐12 (or the equivalent in European countries) in special education were eligible. In addition to exploring the effects of small class sizes in special education from a quantitative perspective, we aimed to gain insight into the lived experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education contexts, as they are presented in the qualitative research literature. The review therefore also included all types of empirical qualitative studies that collected primary data and provided descriptions of main methodological issues such as selection of informants, data collection procedures, and type of data analysis. Eligible qualitative study designs included but were not limited to studies using ethnographic observation or field work formats, or qualitative interview techniques applied to individual or focus group conversations.

Data Collection and Analysis

The literature search yielded a total of 26,141 records which were screened for eligibility based on title and abstract. From these, 262 potentially relevant records were retrieved and screened in full text, resulting in seven studies being included: three quantitative and five qualitative studies (one study contained both eligible quantitative and qualitative data). Two of the quantitative studies could not be used in the data synthesis as they were judged to have a critical risk of bias and, in accordance with the protocol, were excluded from the meta‐analysis on the basis that they would be more likely to mislead than inform. The third quantitative study did not provide enough information enabling us to calculate an effect size and standard error. Meta‐analysis was therefore not possible. Following quality appraisal of the qualitative studies, three qualitative studies were judged to be of sufficient methodological quality. It was not possible to perform a qualitative thematic synthesis since in two of these studies, findings particular to special education class size were scarce. Therefore, only descriptive data extraction could be performed.

Main Results

Despite the comprehensive searches, the present review only included seven studies published between 1926 and 2020. Two studies were purely quantitative (Forness, 1985; Metzner, 1926) and from the U.S. Four studies used qualitative methodology (Gottlieb, 1997; Huang, 2020; Keith, 1993; Prunty, 2012) and were from the US (2), China (1), and Ireland (1). One study, MAGI Educational Services (1995), contained both eligible quantitative and qualitative data and was from the U.S.

Authors' Conclusions

The major finding of the present review was that there were virtually no contemporary quantitative studies exploring the effects of small class sizes in special education, thus making it impossible to perform a meta‐analysis. More research is therefore thoroughly needed. Findings from the summary of included qualitative studies reflected that to the special education students and staff members participating in these studies, smaller class sizes were the preferred option because they allowed for more individualised instruction time and increased teacher attention to students' diverse needs. It should be noted that these studies were few in number and took place in very diverse contexts and across a large time span. There is a need for more qualitative research into the views and experiences of teachers, parents, and school administrators with special education class sizes in different local contexts and across various provision models. But most importantly, future research should strive to represent the voices of children and young people with special needs since they are the experts when it comes to matters concerning their own lives.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. little evidence exists on the effects of small class sizes in special education.

Despite carrying out extensive literature searches, the authors of this review found only seven studies exploring the question of class size in special education. The authors therefore call for more research from quantitative and qualitative researchers alike, such that practitioners and administrators may find guidance in their endeavours to create the best possible school provisions for all children with special educational needs.

1.2. What is this review about?

While research on the relationship between general education class size and student achievement is plentiful, research on class size in special education is scarce, even though class size issues must be considered particularly important to students with special educational needs. This systematic review sought to examine the effects of small class sizes in special education on the academic achievement, socioemotional development and well‐being of children with special educational needs.

Furthermore, the review aimed to perform a qualitative exploration of the views of children, teachers and parents concerning class size conditions in special education.

A secondary objective was to explore how potential moderators (e.g. performance at baseline, age, and type of special educational need) affected the outcomes.

What is the aim of this review?

The objective of this Campbell systematic review was to synthesise data from existing studies to assess the impact of small class sizes in special education on students' academic achievement, socioemotional outcomes and well‐being.

1.3. What studies are included?

This review included seven studies, of which two were quantitative, four were qualitative, and one was both quantitative and qualitative. It was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis, nor a qualitative thematic synthesis. The included studies were critically assessed, coded for descriptive data, and narratively summarised.

One quantitative study was assessed to be of sufficient methodological quality following risk of bias assessment. Unfortunately, it was not possible to extract an effect size from this study since it did not report the required information and the study authors could not be contacted.

Three qualitative studies were assessed to be of sufficient methodological quality following qualitative critical appraisal.

1.4. What are the main findings of this review?

There are surprisingly few studies exploring the effects of small class sizes in special education on any outcomes. The included qualitative studies find that smaller class sizes are the most preferred option among students with special educational needs, their teachers and school principals. This is because of the possibilities afforded in terms of individualised instruction time and increased teacher attention to the needs of each student.

1.5. What do the findings of this review mean?

The impact of small class sizes in special education is under‐researched both within the quantitative and the qualitative literature.

Future research should aim to fill this knowledge gap from diverse methodological perspectives, paying close attention to the views of parents, teachers, administrators and, most importantly, the children and young people whose everyday lives are spent in the various special education provisions.

1.6. How up‐to‐date is this review?

Searches in bibliographic databases and EBSCO OPEN Dissertations were performed in April 2021, while the remaining searches for grey literature, hand searches in key journals, and citation tracking took place between January and May 2022.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. description of the condition.

Class size reductions in general education are some of the most researched educational interventions in social science, yet researchers have not reached any final conclusions regarding their effects. While some researchers point to small and insignificant differences between varying class sizes, others find positive and significant effects of small class sizes on, for example, children's academic outcomes. In a previous Campbell Systematic Review on small class sizes in general education, Filges ( 2018 ) found evidence suggesting, at best, a small effect on reading achievement, whereas there was a negative, but statistically insignificant, effect on mathematics.

While research on the relationship between general education class size and student achievement is plentiful, research on class size in special education is scarce (see e.g., McCrea, 1996 ; Russ, 2001 ; Zarghami, 2004 ), even though class size issues must be considered particularly important to students with special educational needs. These students compose a highly diverse group, but they share a common need for special educational accommodations, which often entails additional instructional support in smaller units than what is usually provided in general education. Special education class sizes may vary greatly, both across countries and regions, as well as across different student groups, but will usually be small relative to general education classrooms. In most cases, placement in special education, as opposed to, for example, inclusion in general education, is based exactly on the child's need for close adult support in a smaller unit, where instruction can be tailored to the needs of each child and a calmer, more structured environment can be created. Following this, one may assume that there are advantages to small class sizes in special education, in that children are placed in a suitable environment with the support they need to thrive and learn (for a discussion of perceptions on the benefits of special education, see e.g., Kavale, 2000 ). However, there may also be challenges to small class sizes, for example, in terms of the opportunities available for building friendships.

It should be noted that class size in special education is connected to other structural factors such as, for example, student–teacher ratio and type of special education provision. In this review, we focus on class size since our main interest lies in exploring the specific mechanisms behind being in a smaller group. However, we have paid close attention to the relatedness and potential overlap between class size and concepts such as student/teacher ratio or caseload (for more about these concepts, see Description of the intervention). When it comes to the type of special education provision, we have included all types of settings where children with special educational needs are grouped together for instruction (i.e., segregated schools/classes/groups/units to which only students with special educational needs attend).

Finally, class size issues, both in general and in special education, are associated with ongoing discussions on educational spending and budgetary constraints. Hence, in school systems imposed with financial constraints, small class sizes in special education settings may be deemed too expensive. As a result, children with special educational needs may be placed in larger units with potential adverse effects on their learning and well‐being. At this point, there is however a lack of clarity as to the effects of small class sizes in special education on student academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being. Inevitably, such lack of clarity is an obstacle for special educators and policymakers trying to make informed decisions. This highlights the policy relevance of the current systematic review, in which we examined the effects of small class sizes in special education on the academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being of children with special educational needs. In working towards this aim, we planned to apply an approach consisting of both a statistical meta‐analysis (if possible from the studies found through our searches) and an exploration of the experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education, as reported in qualitative studies. We chose to include studies applying a qualitative methodology because the combination of quantitative and qualitative methods had the potential to provide a deeper insight into the complexity of class size questions in special education, including the voices of children and teachers who spend their everyday lives in special education contexts.

2.2. Description of the intervention

Special education in this review refers to educational settings designed to provide instruction exclusively for children with special educational needs. In such settings, both the instructional and physical classroom environment may be adjusted to accommodate the specific needs of the student group, as in the use of individual work tables and visual aids (pictograms) for children on the autism spectrum. We have included studies of all kinds of special education settings that are attended only by children with special educational needs (i.e., segregated special education settings as opposed to inclusion settings where children with and without special educational needs are taught together). We have included both part‐ and full‐time special education provisions (with an example of a part‐time provision being resource rooms attended by students with specific learning difficulties within one or more academic subjects). Furthermore, no limits have been imposed concerning the placement of special education provisions, that is, we have included both separate special schools and special education classes, units or resource rooms lodged within mainstream schools. We acknowledge that significant variations exist in special education provisions across time (e.g., due to new developments in pedagogical approaches and learning aids) and between (as well as within) countries, just as we are aware of the diversity between special education provisions, for example, in terms of how they are staffed and to which degree they are specialised to work with particular student groups. Our approach has therefore been to be inclusive in our search and screening process by not imposing limits on publication date or study location and by defining special education as all kinds of provisions where children with any type of special educational need are grouped together for instruction for any given amount of time (for our definition of what constitutes a special educational need, see Types of participants).

In this review, it is important to distinguish between the following terms: class size , student–teacher ratio , and caseload . Class size refers to the number of students present in a classroom at a given point in time. Student–teacher ratio refers to the number of students per teacher within a classroom or an educational setting. Furthermore, some studies may apply the term caseload which is typically defined as the number of students with individual education plans (IEPs) for whom a teacher serves as ‘case manager’ (Minnesota Department, 2000 ). In this review, the intervention is a small class size. Thus, studies only considering student–teacher ratios or caseloads are not eligible.

Our rationale for focusing on class size is based in the belief that although class size and student–teacher ratios or caseloads in special education are related, they involve somewhat different assumptions about how a small class size as opposed to a larger one might change the opportunities for students and teachers. With class size, the mechanism in play is based on assumptions about the dynamics of a smaller group and the belief that with smaller groups, teachers are better able to develop an in‐depth understanding of student needs through more focused interactions, better assessment, and fewer disciplinary problems (Ehrenberg, 2001 ; Filges, 2018 ). The size of the group in itself will often be of specific importance to students with special educational needs, for example, students diagnosed with sensory processing disorders, making them sensitive to noise and movement, or students with ASD who struggle with reading social cues in larger groups. For such students, being in a larger class would likely feel overwhelming and stressful, no matter the student–teacher ratio.

Student–teacher ratio and caseload are also of great importance, but do not take in the specific mechanisms of being in a smaller group which we find to be central in special education. We acknowledge the relatedness of these concepts to class size and are aware that terms may in some cases overlap. We paid attention to this when searching for studies by adding a search term for student–teacher ratio and when screening the studies.

It is possible that the intensity of the intervention, that is, the size of a change in class size and the initial class size from which this change is made, can play a role in determining the intervention effect. For intensity, the question is: how small does a class have to be to optimise the advantage? In general education for example, large gains are attainable when class size is below 20 students (Biddle, 2002 ; Finn, 2002 ), but gains are also attainable if class size is not below 20 students (Angrist, 1999 ; Borland, 2005 ; Fredriksson, 2013 ; Schanzenbach, 2007 ). It has been argued that the impact of class size reductions of different sizes and from different baseline class sizes is reasonably stable and more or less linear when measured per student (Angrist, 2009 ; Schanzenbach, 2007 ). Other researchers argue that the effect of class size is not only non‐linear but also non‐monotonic, implying that an optimal class size exists (Borland, 2005 ). Thus, the question of whether the size of a change in class size and the initial class size from which the change is made matters for the magnitude of intervention effects is still an open question. For this reason, we planned to include intensity (size of change in special education class size and initial class size) as a moderator if it was possible given the information presented in the included studies.

2.3. How the intervention might work

Due to the specialised and varied nature of special needs provision, issues of class size in this area are likely to be complex (Ahearn, 1995 ). However, small class sizes may promote student engagement and instructional individualisation, which is of particular importance to students with special educational needs. A research report from 1997 evaluating increases in resource room instructional group size in New York City public schools may serve to illustrate the importance of individualisation in special education (Gottlieb, 1997 ). The report indicated that increases in instructional group sizes from 5 to at most 8 students per teacher led to decreases in the reading achievement scores of resource room students. Resource room teachers reported diminished opportunities for sufficiently helping students. Furthermore, observations revealed little time spent on individual instruction.

Small class sizes may be better suited to address the potential physical and psychological challenges of students with special educational needs, for example, by providing closer adult‐child interaction, better accommodation of individual needs, and a more focused social interaction with fewer peers. Thus, smaller class sizes in special education may have a positive impact on both academic achievement and socioemotional development as well as on student well‐being at school.

On the other hand, small class sizes may limit the possibilities for finding compatible peers with whom to build friendships, hence leading to adverse effects on student's social and personal well‐being at school. This may also impact on the options available for building social skills, which are vital to, for example, students with autism‐spectrum‐disorders. Furthermore, small class sizes may lead to decreased variation in academic and social skills within the class, limiting the potential for positive peer effects on student academic learning and socioemotional development (e.g., learning from peers with more advanced academic skills).

As reflected in the above discussion about the potential benefits (or lack thereof) pertaining to smaller class sizes in special education, the effects of any given change in class size may occur both within the realm of academic achievement as well as across socioemotional domains (covering children's psychological, emotional, and social adjustment, as well as mental health) and in terms of student well‐being (defined as children's subjective quality of life, pleasant emotions, happiness, and low levels of stress and negative moods); each of these domains (academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being) are therefore included as key outcomes in the present review.

2.4. Why it is important to do this review

As previously noted, there is a lack of clarity as to the impact of small class sizes in special education on student academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being, making it difficult for special educators and policymakers to make informed decisions. Furthermore, class size alterations are associated with ongoing discussions on educational spending and budgetary constraints, highlighting the policy relevance of strengthening the knowledge base through a systematic review of the available literature.

Few authors have tried to review the available literature on special education class sizes, and these reviews have not followed rigorous, systematic frameworks, such as that applied in a Campbell systematic review. McCrea ( 1996 ) conducted a review on special education and class size including a sample of American studies. These studies pointed to some effects of class size on the learning environment in class as well as on student achievement and behaviour, especially at the elementary level. Furthermore, in an article exploring the class size literature, Zarghami ( 2004 ) examined the effects of appropriate class size and caseload on special education student academic achievement. The authors were not able to identify a single best way to determine appropriate class and group sizes for special education instruction. However, they pointed to the existence of well‐qualified teachers as an important factor in increasing student achievement. Finally, Ahearn ( 1995 ) analysed state special education regulations on class size/caseload in the U.S. and reviewed research on class size in general education and special education. The report showed that state requirements for class size/caseload in special education programmes were much more specific and complicated than those for general education, and that the specialised nature and variety of the services delivered to students with special educational needs, combined with the restrictions attributable to specific student disabilities, contributed to those complications. In line with the article by Zarghami ( 2004 ), Ahearn ( 1995 ) concluded that there was no single best way to determine class sizes for special education programmes, adding that the information available was inadequate.

The above mentioned reviews did not apply the extensive, systematic literature searches and critical appraisals that are performed in a Campbell systematic review. Furthermore, they date back 15 years or more, which means that they do not include newer developments in special education research. Therefore, we find that the present review fills a research gap by providing an up‐to‐date overview of what (little) research is available exploring the effects of small class sizes in special education and the views of children, parents, and teachers who experience different issues related to special education class size. In this sense, the main contribution of the review lies in shedding light on the fact that more research is still needed to gain knowledge into the complexities of class size in special education.

3. OBJECTIVES

The objective of this systematic review was to uncover and synthesise data from studies to assess the impact of small class sizes on the academic achievement, socioemotional development, and well‐being of students in special education. We also aimed to investigate the extent to which the effects differed among subgroups of students. Furthermore, we aimed to perform a qualitative exploration of the experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education.

4.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

4.1.1. types of studies.

The screening of potentially eligible studies for this review was performed according to inclusion criteria related to types of study designs, types of participants, types of interventions, and types of outcome measures, all of which are described in the following sections (for the screening guide, see Supporting Information: Appendix 2 ). These criteria were also specified in the published protocol (Bondebjerg, 2021 ).

To summarise what is known about the possible causal effects of small special education class sizes, we included all quantitative study designs that used a well‐defined control or comparison group, that is, studies that compared outcomes for groups of students in smaller versus larger special education classes. This is further outlined in the section Assessment of risk of bias in included studies , and the methodological appropriateness of the included quantitative studies was assessed according to the risk of bias.

The quantitative study designs included in the review were:

- 1. Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (allocated at either the individual or cluster level, for example, class/school/geographical area etc.),

- 2. Non‐randomised studies (where allocation had occurred in the course of usual decisions, was not controlled by the researcher, and included a comparison of two or more groups of participants, that is, at least a treated group and a control group).

For non‐randomised studies, where the change in class size occurred in the course of usual decisions (e.g., due to policies mandating class size alterations), we assessed whether the authors demonstrated sufficient pre‐reatment group equivalence on key participant characteristics.

Studies using single group pre‐post comparisons were not included. Non‐randomised studies using an instrumental variable approach were also not included—see Supporting Information: Appendix 1 ( Justification of exclusion of studies using an instrumental variable (IV) approach ) for our rationale for excluding studies of these designs. A further requirement to all types of studies (randomised as well as non‐randomised) was that they were able to identify an intervention effect. Studies where, for example, small classes were present in one school only and the comparison group was larger classes at another school (or more schools for that matter), would not be able to separate the treatment effect from the school effect.

The treatment in this review was a small class size. To investigate the effects of small class sizes, we included studies that compared students in smaller classes with students in larger classes. This meant that we included both studies where the intervention consisted of a reduction in class size and studies where there was an increase in class size, since both types of studies (if robustly conducted) would allow us to compare the outcomes of children in smaller classes with those of children in larger classes. We only included studies that used measures of class size and measures of outcome data at the individual or class level. We excluded studies that relied on measures of class size and measures of outcomes aggregated to a level higher than the class (e.g., school or school district).

In addition to exploring the causal effects of small class sizes in special education through an analysis of quantitative studies meeting the criteria above, we aimed to gain qualitative insight into the experiences of children, teachers, and parents with class size issues in special education contexts. To this end, we included all types of empirical qualitative studies that collected primary data and provided descriptions of main methodological issues such as informant selection, data collection procedures, and type of data analysis. Eligible qualitative studies may apply a wealth of data collection methods, including (but not limited) to participant observations, in‐depth interviews, or focus groups.