Back to Map

War in Yemen

Center for Preventive Action

Fighting between Houthi rebels and the Saudi coalition that backs Yemen’s internationally recognized government has largely subsided , but Houthis have repeatedly attacked ships transiting the Red Sea in response to Israel's war on Hamas. Dialogue between the Houthis and Saudi Arabia, along with Iranian-Saudi normalization , has provided hope for a negotiated solution. However, talks have yielded little progress and have been punctuated by violence . The Southern Transitional Council (STC) has also renewed calls for an independent southern Yemeni state, complicating peace prospects, and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) attacks have surged . Meanwhile, the humanitarian crisis has not improved; 21.6 million people need aid, including 11 million children, and more than 4.5 million are displaced.

Yemen’s civil war began in 2014 when Houthi insurgents—Shiite rebels with links to Iran and a history of rising up against the Sunni government— took control of Yemen’s capital and largest city, Sanaa, demanding lower fuel prices and a new government. Following failed negotiations, the rebels seized the presidential palace in January 2015, leading President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi and his government to resign . Beginning in March 2015, a coalition of Gulf states led by Saudi Arabia launched a campaign of economic isolation and air strikes against the Houthi insurgents, with U.S. logistical and intelligence support.

In February 2015, after escaping from Sanaa, Hadi rescinded his resignation, complicating the UN-supported transitional council formed to govern from the southern port city of Aden. However, a Houthi advance forced Hadi to flee Aden for exile in Saudi Arabia. While he attempted to return to Aden later that year, he ultimately ruled as president in exile .

The intervention of regional powers in Yemen’s conflict, including Iran and Gulf states led by Saudi Arabia, also drew the country into a regional proxy struggle along the broader Sunni-Shia divide . In June 2015, Saudi Arabia implemented a naval blockade to prevent Iran from supplying the Houthis. In response, Iran dispatched a naval convoy , raising the risk of military escalation between the two countries. The militarization of Yemen’s waters also drew the attention of the U.S. Navy, which has continued to seize Yemen-bound Iranian weapons. The blockade has been at the center of the humanitarian crisis throughout the conflict. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have also led an unrelenting air campaign, with their coalition carrying out over twenty-five thousand air strikes . These strikes have caused over nineteen thousand civilian casualties , and from 2021 to 2022 the Houthis responded with a spate of drone attacks on Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

On the battleground, the Houthis made fast progress at the start of the war, moving eastward to Marib and pushing south to Aden in early 2015. However, a Saudi intervention pushed the Houthis back north and west until the frontlines stabilized . A UN effort to broker peace talks between allied Houthi rebels and the internationally recognized Yemeni government stalled in the summer of 2016. In the south and east of the country, a growing al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) threatened the government’s control, though its influence has since waned .

In July 2016, the Houthis and the government of former President Saleh, ousted in 2011 after nearly thirty years in power, announced the formation of a political council to govern Sana’a and much of northern Yemen. However, in December 2017, Saleh broke with the Houthis and called for his followers to take up arms against them. Saleh was killed and his forces were defeated within two days . Meanwhile, Hadi and the internationally recognized governments faced their own challenge: the Southern Transitional Council (STC) . Established in 2017, the STC grew out of the southern separatist movement that predates the civil war and controls areas in the southwest around and including Aden. A 2019 Saudi-brokered deal incorporated the STC into the internationally-recognized governments, but the faction could still present challenges .

In 2018, coalition forces made an offensive push on the coast northward to the strategic city of Hodeidah, the main seaport for northern Yemen. The fighting ended in a ceasefire and commitments to withdraw troops from the city; the ceasefire largely held , but fighting continued elsewhere. Taiz, Yemen’s third largest city, also remained a key point of contention, having been blockaded by the Houthis since 2015. In 2020, the UAE officially withdrew from Yemen, but it maintains extensive influence in the country.

In February 2021, Houthi rebels launched an offensive to seize Marib, the last stronghold of Yemen’s internationally recognized government, and in early March, Houthi rebels conducted missile air strikes in Saudi Arabia, including targeting oil tankers and facilities and international airports. The Saudi-led coalition responded to the increase in attacks with air strikes targeting Sanaa. The offensive was the deadliest clash since 2018, killing hundreds of fighters and complicating peace processes.

Meanwhile, the conflict has taken a heavy toll on Yemeni civilians, making Yemen the world’s worst humanitarian crisis . The UN estimates that 60 percent of the estimated 377,000 deaths in Yemen between 2015 and the beginning of 2022 were the result of indirect causes like food insecurity and lack of accessible health services. Two-thirds of the population, or 21.6 million Yemenis, remain in dire need of assistance . Five million are at risk of famine, and a cholera outbreak has affected over one million people. All sides of the conflict are reported to have violated human rights and international humanitarian law.

An economic crisis continues to compound the ongoing humanitarian crisis. In late 2019, the conflict led to the splintering of the economy into two broad economic zones under territories controlled by the Houthis and the Saudi-backed government. In the fall of 2021, the sharp depreciation of Yemen’s currency, particularly in government-controlled areas, significantly reduced people’s purchasing power and pushed many basic necessities even further out of reach, leading to widespread protests across cities in southern Yemen. Security forces forcefully responded to the protests.

Separate from the ongoing civil war, the United States is suspected of conducting counterterrorism operations in Yemen, relying mainly on air strikes to target al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and militants associated with the self-proclaimed Islamic State. The United States is deeply invested in combating terrorism and violent extremism in Yemen, having collaborated with the Yemeni government on counterterrorism since the bombing of the USS Cole in 2000. Since 2002, the United States has carried out nearly four hundred strikes in Yemen. In April 2016, the United States deployed a small team of forces to advise and assist Saudi-led troops to retake territory from AQAP. In January 2017, a U.S. Special Operations Forces raid in central Yemen killed one U.S. service member, several suspected AQAP-affiliated fighters, and an unknown number of Yemeni civilians. Breaking from previous U.S. policy, President Joe Biden announced an end to U.S. support for Saudi-led offensive operations in Yemen in February 2021 and revoked its designation of the Houthis as a terrorist organization. In January 2024, the Houthis were redesignated as a terrorist organization due to their recent attacks on ships in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.

In April 2022, Yemen’s internationally recognized but unpopular president, Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi, resigned after ten years in power to make way for a new seven-member presidential council more representative of Yemen’s political factions. Rashad al-Alimi, a Hadi advisor with close ties to Saudi Arabia and powerful Yemeni politicians, chairs the new council.

Though a six-month UN-brokered cease-fire officially lapsed in October 2022, both sides have since refrained from major escalatory actions and hostility levels remain low. Peace talks between Saudi and Houthi officials, mediated by Oman, resumed in April 2023, accompanying ongoing UN mediation efforts. However, concrete progress remains elusive , and the first official Houthi visit to the Saudi capital since the war began, on September 14, yielded nothing beyond optimistic statements. The discussions were reportedly centered around a complete reopening of Houthi-controlled ports and Sanaa airport, reconstruction efforts, and a timeline for foreign forces to withdraw from Yemen. Negotiations have also been overshadowed by the suspension of the only commercial air route out of Sanaa and a late September Houthi drone strike that killed four Bahraini members of the Saudi-led coalition.

Talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia in April 2023, mediated by China, have raised hopes of a political settlement to end the conflict in Yemen. The talks led to a breakthrough agreement to re-establish diplomatic relations and re-open both sides' embassies after years of tension and hostility. Iran’s UN mission said that the agreement could accelerate efforts to renew the lapsed cease-fire.

While hostility between the two warring sides remains low, AQAP’s political violence surged in May and June, reaching the highest monthly level since November 2022. Most of the violence has been centered around Yemen’s Abyan and Shawba governates, where AQAP has used drones and IEDs to target forces affiliated with the STC. In August 2023, AQAP launched an explosion that killed a military commander and three soldiers from the Security Belt Forces, an armed group loyal to the STC. Earlier that month, AQAP fighters killed five troops from another force affiliated with the separatist council. The recent use of drones by AQAP in Yemen’s south is likely an attempt to reassert its influence in the area despite its waning influence, and some speculate that this sudden and sustained use of drones signals external support. Additionally, AQAP has continued its anti-separatist efforts, with another attack in early October targeting and wounding five STC-backed fighters.

Three days following the October 7 attack on Israel, Yemen’s Houthi leader Abdel-Malek al-Houthi warned that if the United States intervenes in the Hamas-Israel War directly, the group will respond by taking military action. In mid-October, U.S. officials announced that the USS Carney downed several Houthi cruise missiles and drones fired toward Israel. The Houthis continued to launch several rounds of missiles and drones until it officially announced entry into the war to support Palestinians in the Gaza Strip on October 31. Houthi attacks of the same nature continued into November. On November 19, the Houthis hijacked a commercial ship in the Red Sea and have since attacked at least thirty-three others with drones, missiles, and speed boats as of late January 2024. As a result, major shipping companies have stopped using the Red Sea—through which almost 15 percent of global seaborne trade passes—and have rerouted to take longer and costlier journeys around Southern Africa instead. The situation has resulted in heightened shipping and insurance costs, stoking fears of a renewed cost-of-living crisis. In response to the consistent Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, the United States and United Kingdom carried out coordinated air strikes on Houthi targets in Yemen on January 11 and January 22. It is unclear whether the attacks will cease in the near future, with the Houthis vowing to persist in their military operations until a ceasefire is agreed to in the Gaza Strip and aid is allowed into the enclave.

Latest News

Sign up for our newsletter, receive the center for preventive action's quarterly snapshot of global hot spots with expert analysis on ways to prevent and mitigate deadly conflict..

On The Site

Photo by yeowatzup on Wikimedia Commons

How U.S. Policy in Yemen Went Tragically Wrong

May 13, 2024 | M'Baye, Fatou | Current Affairs , Middle East Studies , Politics

Alexandra Stark—

On October 8, 2016, an airstrike by the Saudi-led coalition struck a crowded funeral hall in Sanaa, Yemen, killing at least 140 people and wounding an additional 600, including children. The strike was shocking to many Americans, not only because of the tragic death toll, but because of how it happened: according to Human Rights Watch , remnants of a U.S.-manufactured bomb were identified at the site.

This was eight years after President Obama was elected with the promise that he would end the United States’ “ dumb wars ” in the Middle East. So how, and why, was a U.S.-made weapon contributing to the deaths of children in Yemen?

The answer is important—and not just to humanitarians who are concerned about preventing harm to Yemeni civilians. It’s important because it can help us to understand why even well-intentioned U.S. policy in the Middle East often goes so tragically wrong.

For decades, U.S. policy in Yemen has been shaped by narrowly defined U.S. security interests, from countering the Soviet Union’s influence in the region during the Cold War to combating terrorist organizations after 9/11. It was not about what could contribute to the well-being of Yemenis.

Before Houthi insurgents rose up and captured the capital in 2014, setting off the civil war, U.S. policy in Yemen was framed by its own counterterrorism interests. The United States faced the dilemma of how to fight Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)—a terrorist organization linked to an attempted bombing on a U.S.-bound airliner in 2009 among other threats—without risking another quagmire in the Middle East. To effectively prevent terrorism without a larger U.S. investment, the U.S. partnered with Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s government and launched the occasional drone or missile strike. At first, American officials thought this approach was so successful that they dubbed it “ the Yemen model ” and advertised its success through early 2015, when the country was overrun by civil war.

The Yemen model has not worked because this framework is too narrow. It meant that Obama administration officials were unable to see that their corrupt government partner had started to wobble, even before the Arab Spring protests washed over the country in 2011. And it meant that in March 2015, when Saudi Arabia asked for support in their military intervention against the Houthis, U.S. officials felt they had to go along. They wanted to maintain the United States’ important security relationship with Gulf partners, even though one official said that the decision felt like “getting into a car with a drunk driver.”

Later on, some U.S. officials would acknowledge that “we were wrong to think that cautious and at times conditional support for the war in Yemen would influence Saudi and Emirati policy.” Still, under the Trump administration, the U.S. doubled down on its support for the coalition until the October 2018 assassination of Saudi regime critic Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi agents.

In February 2021, President Biden announced that the United States would be “stepping up our diplomacy to end the war in Yemen,” and in April 2022, the UN managed to negotiate a truce . The truce has, more or less, held up even though the Houthis continue to attack commercial vessels in the Red Sea and U.S. still launches strikes on Houthi targets.

In the meantime, though, U.S. support had contributed to a war that caused “one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises,” according to Oxfam , causing over 12,000 civilian deaths and forcing almost 4 million people to flee the fighting. Eighty percent of Yemen’s population, or 24 million people, now relies on emergency aid. Aid groups have warned that the turmoil in the Red Sea could contribute to the ongoing humanitarian crisis and create additional barriers for the humanitarian organizations delivering lifesaving support in Yemen.

The lessons of the Yemen model therefore remain potent a decade on, as another devastating conflict rages in Gaza. A narrow focus on maintaining U.S. security partnerships, counter-terrorism operations, and countering Iranian influence did not achieve U.S. security goals in Yemen. What might a new approach look like? It could focus on the well-being of people in Yemen and across the region, instead of on only narrowly defined U.S. security interests.

Alexandra Stark is an associate policy researcher at RAND, a nonprofit, nonpartian research institution, and a fellow at New America’s International Security Program. Her award-winning work has been published in academic and public outlets.

Recent Posts

- Ep. 137 – Interacting with Color

- Our Palestine Question: A Conversation with Geoffrey Levin

- What the Founders Didn’t Know—But Their Children Did—About the Constitution

- Loneliness and Screens: Causes and Consequences

- Why Does Paris Look the Way it Does?

- Writing a Life

Sign up for updates on new releases and special offers

Newsletter signup, shipping location.

Our website offers shipping to the United States and Canada only. For customers in other countries:

Mexico and South America: Contact TriLiteral to place your order. All Others: Visit our Yale University Press London website to place your order.

Shipping Updated

Learn more about Schreiben lernen, 2nd Edition, available now.

- Search UNH.edu

- Search Inquiry Journal

Commonly Searched Items:

- Academic Calendar

- Feature Article

- Research Articles

- Commentaries

- Mentor Highlights

- Editorial Staff

Yemen and the Dynamics of Foreign Intervention in Failed States

Yemen, a small nation at the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula, has been mired in political strife and unrest since its government was overthrown in 2014 by the Houthis, a minority Shiite tribal group. Soon after, foreign intervention began, with Saudi Arabia joining the fight alongside the remains of the Yemen government authorities against the Houthis. In 2015, Iran began supporting their ally the Houthis with economic aid and materials, but not with direct military involvement. What ensued has been labeled one of the worst modern-day humanitarian crises, and it rages on to this day.

The author, Bryn Lauer

With no end to the conflict in sight, Yemen now has the status of a failed state, one with no governmental authority or rule of law. This humanitarian tragedy raises many unanswered questions about the effects of foreign intervention on failed states: Why has Yemen’s civil war continued? Why is Saudi Arabia siding with a country lacking a working government? What does Iran have to gain by allying with the Houthis, and why hasn’t it intervened directly? Has Yemen as a failed state exacerbated the conflict? What is at stake for each actor?

The use of the term failed state is debated by political science researchers. Definitions of the term range from complete anarchy to a functioning government with weak institutions. In this article I use the term failed state for two reasons: (1) it places greater emphasis on the system of governance as a path to civil war than on extremism and terrorism (Cordesman and Molot, 2019), and (2) it has been used explicitly as justification for intervention by Saudi Arabia. I use political scientist Robert Rotberg’s commonly accepted definition of a failed state: a state which is unable to provide political goods to its inhabitants and experiences high levels of internal violence (Rotberg, 2003). My project aims to shed light on the dynamic between failed states and foreign intervention, with Yemen as a case study. I became interested in this subject because of an international politics course I took at SUNY Binghamton and have followed Yemen closely since then. After transferring to the University of New Hampshire (UNH) and completing an internship at the Department of State in the Office of Investment Affairs, I received an Undergraduate Research Award, with Dr. Elizabeth Carter as my faculty mentor, and turned my interest into a concrete research project.

Summarizing Yemen’s history over the past several decades remains a challenge, which is why I focus on the key events in this background section. Yemen’s conflict is multifaceted, with regional and domestic actors at play, a history of governmental instability, economic constraints, political fallout, and strained alliances.

The Houthis make up 5 to 10 percent of the population in Yemen. Although a revolutionary Shiite Muslim group, the Houthis’ plight began as a political one during the rule of Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh from 1978 to 2011 (Haykel, 2021). For years, authoritarian President Saleh used corruption and oppression to unify the government and to repress dissent. The Houthis’ goal was to assert themselves as a dominant political group to bring an end to political marginalization and discrimination. These sentiments then cultivated six wars between the Houthis and the central government from 2004 to 2010. In 2011, President Saleh resigned because of mounting tension among supporters and was replaced by Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, but Hadi’s leadership lasted only three years and included unsuccessful attempts at reform before the Houthis seized Sana’a, the highly populated capital of Yemen, thereby waging war once again on the government of Yemen. With no true foundation in place, Yemen’s government fell swiftly by January 2015, when President Hadi and other politicians were forced to resign. President Hadi fled to Saudi Arabia. Yemen’s sovereignty became porous, the remaining domestic institutions ceased to operate, and foreign actors have had free rein to exert their influence over the region since 2015.

On March 26, 2015, shortly after the Houthis overthrew Hadi’s government, Saudi Arabia launched its first military involvement in Yemen with Operation Decisive Storm, and air strikes, ground troops, and economic sanctions were deployed almost immediately (Nußberger, 2017; Gunaratne, 2018). The launch of Operation Decisive Storm in 2015 was Saudi Arabia’s first deviation from its norm of unassertive foreign policy toward Yemen (Stenslie, 2013). Saudi Arabia justified its active, open military engagement with Yemen by claiming it was countering Iranian influence while defending itself against fallout from a failed state.

Airstrike by Saudi Arabia in Sana’a, Yemen, 2015. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Throughout the fighting, Saudi Arabia and many prominent Western scholars have accused Iran of supporting the Houthis. Iran has historically kept a limited role in Yemeni affairs and did not become an active ally of the Houthis until Saudi Arabia’s direct involvement in 2015. However, during the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, which were a series of anti-government protests that ricocheted throughout the Middle East, Iran had provided limited aid to the Houthis. The Houthis are not dependent on Iran and are not under their direct control (Vatanka, 2015; Milani, 2015). Nonetheless, Iran has increasingly provided more arms to the Houthis as a direct response to escalation in fighting from Saudi coalition forces (Nichols and Landay, 2021).

As of spring 2022, the conflict is continuing to escalate, United Nations mediation attempts have repeatedly failed, and there remains no internationally recognized government in place (Aljazeera, 2022; Reuters, 2022). As of 2022, 24 million Yemenis need assistance, 100,000 Yemenis have been killed since the start of the conflict in 2015, and 4 million remain displaced (Global Conflict Tracker, 2022).

Martin Griffiths, a UN Special Envoy to Yemen who has attempted diplomacy between the Yemeni and Houthi factions, noted that the crisis in Yemen is man-made, and that ending the war is a choice. Yet Mr. Griffiths, and others in the international community who support this premise, fail to specify exactly what allowed Yemen’s crisis to become man-made in the first place. I was interested in researching the reasons behind foreign interference in a failed state because, intuitively, intervention should be a means to end a conflict. In Yemen, the conflict has only been exacerbated, and I wanted to know what went wrong and why.

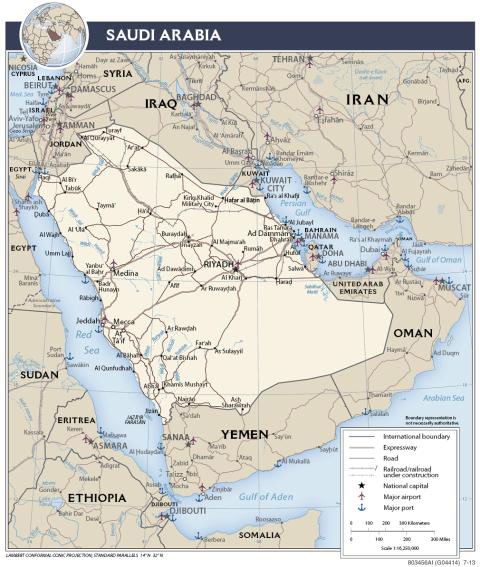

This map shows Yemen in relation to Saudi Arabia, Iran, and other regional countries. Source: Wikimedia Commons

To uncover why regional foreign actors interfere in failed states—specifically, Yemen—I planned several phases of research, each of which would take several weeks. First, I planned to look at when and how Yemen became a failed state, including its weaknesses, when and why each foreign and domestic actor intervened, and the overall geopolitical and societal trends of each actor. Next, I planned to examine empirical evidence from the start of the conflict in 2014 to the present, including military data, domestic and economic data, and peace data. For the final weeks of my research time, I planned to compile theories about the motives of Saudi Arabia, the Houthis, and Iran. This was done via literature review, whereby I examined the rhetoric of each actor toward Yemen and looked at the contemporary policies and overall belief system of each actor. I planned to conclude my research time by drawing conclusions and drafting an argument that would address my research goal. All research was conducted remotely using sources accessible online.

I used a variety of sources over the course of my research, including both political science and history journal articles. For empirical evidence, I relied upon data collected from the World Bank, the Yemen Data Project and Civilian Impact Monitoring Project, as well as online articles from MediaWire, Reuters, and Al Jazeera. Specifically, I collected data on the change in Saudi military expenditures, civilian casualties, coalition air raids, political violence, unemployment, government institutions, rule of law, markets, poverty, GDP, supply chains, migration flows, and peace attempts before and during the war. This data was critical, as it allowed me to quantify the potential impact of interference on factors relating to violence, political stability, and economics in a failed state—specifically, Yemen.

I adapted my research plan on numerous occasions. Most of my research was composed of searching the history of Yemen, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the Houthis on EBSCOHost. From there, I selected data on the conflict and pieced together an argument. When I needed to fill in gaps, I searched news articles. My research was nonlinear, because the ideas grew as I went along, thereby causing me to deviate from my original plan as needed.

Results: Three Opportunities

My research suggests that foreign actors may perceive the cost of intervening in a failed state—a space devoid of authority—as low and therefore simply too good an opportunity to pass up to influence regional power. In pursuing opportunities to intervene in a failed state, foreign actors may exacerbate the conflict and plunge the state into chronic instability. After concluding my research, including my review of the articles and databases mentioned in my methods section, I argue that failed states create three opportunities for actors who intervene.

The first is the Opportunity for Security, in which foreign actors may perceive failed states to be security threats to their own inhabitants and to neighboring countries. Therefore, actors looking to gain favor domestically and regionally may claim to intervene to defend the inhabitants of the failed state while protecting themselves from regional spillover.

The second is the Opportunity for Influence. Because failed states are unable to defend themselves militarily and are unable to pursue diplomatic measures, foreign actors perceive intervention as low risk, and victorious foreign actors gain the opportunity of influencing the restructuring of the government of the failed state in their favor.

The third is the Opportunity for Amplifying Power, in which actors who intervene can amplify their regional power by securing a swift victory at a low cost.

Saudi Arabia: Opportunity for Amplifying Power

With its intervention in the conflict in Yemen, Saudi Arabia claims to pursue the Opportunity for Security, but the reality shows that it pursues the Opportunity for Amplifying Power. Despite claiming to defend the Yemeni people and restore the Hadi government, the extent and intensity of Saudi Arabia’s military efforts, their unwillingness to cooperate in peace talks with the Houthis and other actors or abide by ceasefires, their blocking of food and medicinal imports, and deliberate attacks on civilian infrastructure such as hospitals indicate they are uninterested in the well-being of Yemen’s inhabitants and its stability. Actors insecure in regional power likely pursue more aggressive intervention as a desperate attempt to amplify their regional status. Saudi Arabia’s regional power status has been waning since 2014, driven largely by their dwindling oil reserves and unsuccessful interventions in Iraq after 2003 and Lebanon in 2008 (Council, 2011), which evidences their motivation behind intervention.

As mentioned previously, Saudi Arabia has not acted in a way that suggests it is concerned with a strong Yemeni state, and especially not one as an ally. Driving Yemen into further instability has created a breeding ground for terrorism, illegal immigration, and regional spillover. Under the guise that it is pursuing the Opportunity for Security, Saudi Arabia has been able to justify its intervention as countering Iranian influence while defending itself against fallout from a failed state. In reality, Saudi Arabia’s intentions extend further than self-defense. By pursuing the Opportunity for Amplifying Power, Saudi Arabia has supported an illegitimate government, destroyed critical infrastructure, killed innocent civilians, refused to accept anything other than complete victory over the Houthis, and blocked imports, thereby guaranteeing Yemen’s instability for years to come.

Iran: Opportunity for Influence

Iran’s intervention in Yemen suggests that it is pursuing the Opportunity for Influence. In contrast with Saudi Arabia, Iran is more stable in regional power. This is evidenced by Iran’s national sovereignty and fierce independence, and that it aligns itself with “Neither East nor West” (Maloney, 2017). Stable actors do not seek to use failed states to boost their status and can instead pursue opportunities related to “soft power”—building support domestically and regionally through positive attraction and persuasion (Nye, 1990). Iran seeks to align itself with marginalized groups—in the case of Yemen, the Houthis—to gain in soft power by being viewed as a “champion of the oppressed and marginalized” (Juneau, 2016). This is the same strategy Iran applied in Iraq and Afghanistan, where it exerted soft power through reconstruction aid, infrastructure development, media, and financial investments (Wehrey et al., 2009).

Rather than engage militarily in Yemen, Iran has supported the Houthis from a safe distance. During the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, Iran provided limited aid to the group. By the time the Yemeni government was overthrown in 2014, Iran supplied some arms and economic support to the Houthis, and as of 2022 it continues to keep its distance (IISS, 2019). Iran’s goal is to establish ties to the Houthis should they secure victory and restructure the government. Although Iran does not directly seek to state-build in Yemen, the opportunity to maintain a steady presence with the Houthis has been low-cost and low-risk.

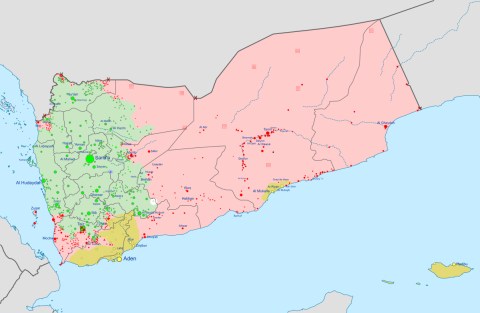

Map of the Yemeni civil war and Saudi Arabian intervention as of 2021. Red is controlled by the Hadi-led government; green is Houthi controlled; and yellow is controlled by the Southern Transitional Council, a secessionist organization in southern Yemen. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Current Situation

As of January 2022, the war continues to drag on, despite Saudi Arabia’s expectation of a quick and decisive victory. Both Saudi Arabia and the Houthis are intensifying their efforts, and Iran continues to steadily support the Houthis with arms. To complicate the situation even further, the United Arab Emirates, which has been part of Saudi Arabia’s coalition since 2015, has shown signs of increasing its role in the conflict for its own ends. All this means that peace is still far out of reach. For years, Saudi officials promised that progress was being made in their fight. Instead, Saudi Arabia finds itself struggling to exit Yemen, which has further exemplified its deteriorating regional power. It is likely that Saudi Arabia overestimated its military prowess and strategy. By using a “blank check” strategy for fighting the Houthis, Saudi Arabia has demonstrated its lack of understanding of the conflict (Horton, 2020). When compared with the fractured and weakly governed Yemeni army supported by Saudi Arabia, the Houthis have repeatedly been successful against coalition forces by striking fast and staying mobile, and, according to some Western experts, are poised to defeat the coalition forces despite the odds (Horton, 2020).

If a peace settlement is reached through Saudi Arabia and Iran brokering a peace agreement between the Houthi and Hadi regimes, the question remains: What is to prevent intervention from occurring every time an internal conflict arises? If Yemen and other failed states experience conflicts via revolution or civil war, what can prevent external actors from intervening? As this research has demonstrated, the incentive to intervene in failed states is a powerful one. Reworking a state’s entire structure of government is complex, and there is no one-size-fits-all.

Given that Saudi Arabia sought to amplify its power, its inability to conquer an easy target will be a major blow to its regional power status. If Iran is to cease support, it is likely that the Houthis would be capable of surviving on their own. Having sought gains in soft power, Iran will not lose out as extensively. Regardless, the real loser at the end of the conflict will be Yemen. The real calamity is that unchecked intervention has degraded the state and created further conflict. Under the guise of championing the oppressed, Saudi Arabia, the Houthis, and Iran have all made for a grave future for Yemen. I hope that readers will see through the layers of complexity of the Yemen conflict and better understand why foreign intervention can be dangerous and costly.

By studying the conflict in Yemen so deeply, I have garnered a greater appreciation for research in international politics. I underestimated how in-depth and complex the research process is. Most importantly, I have learned that research is not rigid; it morphs and grows with each new discovery, and often more questions arise than answers. Because of this research, I now think about the world in terms of opportunities and incentives, on the global and personal level. My next goal is to apply the ideas that I theorized in this project to an exploration of international politics from a financial incentive perspective. This perspective is important to include in the research of world affairs, because, more often than not, money is at the heart of conflicts. After graduation, I hope to follow my passion for researching international conflict and to publish more of my writing on the subject.

Thank you to Mr. Dana Hamel, who made this research possible through a generous endowment, as well as the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research staff. Dr. Elizabeth Carter, thank you for inspiring me to pursue international politics research in your United States in World Affairs class. I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to complete this project and for those who helped me along this journey.

Allinson, Tom. (2019). Yemen’s Houthi rebels: Who are they and what do they want? DW: 01.10.2019. www.dw.com/en/yemens-houthi-rebels-who-are-they-and-what-do-they-want/a-50667558 .

Al Jazeera. (2022). How the Yemen conflict flare-up affects its humanitarian crisis. https:/www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/18/yemens-humanitarian-crisis-at-a-glance .

Council on Foreign Relations Press. (2011). Saudi Arabia in the new Middle East. https://www.cfr.org/report/saudi-arabia-new-middle-east .

Cordesman, A., and Molot, M. (2019). Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, and Yemen: The long-term civil challenges and host country threats from “failed state” wars. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). https://www.csis.org/analysis/afghanistan-iraq-syria-libya-and-yemen .

Global Conflict Tracker. (2022, March 11). War in Yemen. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/war-yemen .

Gunaratne, R., and Johnsen, G. (2018). When did the war in Yemen begin? https://www.lawfareblog.com/when-did-war-yemen-begin .

Haykel, B. (2021). The Houthis, Saudi Arabia and the war in Yemen. https://www.hoover.org/research/houthis-saudi-arabia-and-war-yemen .

Hodali, D. (2021). “Saudi Arabia has lost the war in Yemen.” https://www.dw.com/en/saudi- arabia-has-lost-the-war-in-yemen/a-57007568 .

Horton, M. (2020). Hot issue—the Houthi art of war: Why they keep winning in Yemen. https://jamestown.org/program/hot-issue-the-houthi-art-of-war-why-they-keep-winning-in-yemen/ .

IISS (2019). Chapter five: Yemen. Iran’s networks of influence in the Middle East. Routledge. https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-dossiers/iran-dossier .

Juneau, T. (2016). Iran’s policy towards the Houthis in Yemen: A limited return on a modest investment. International Affairs, 92 (3), 648.

Maloney, S. (2017). The roots and evolution of Iran’s regional strategy. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/the-roots-drivers-and-evolution-of-iran-s-regional-strategy/ .

Milani, M. (2015, April 19). Iran’s game in Yemen: Why Tehran isn’t to blame for the civil war. Foreign Affairs . https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/iran/2015-04-19/irans-game-yemen .

Nichols, M., and Landay, J. (2021). Iran provides Yemen’s Houthis “lethal” support, U.S. official says. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-usa-idUSKBN2C82H1 .

Nußberger, B. (2017). Military strikes in Yemen in 2015: Intervention by invitation and self-defence in the course of Yemen’s “model transitional process.” Journal on the Use of Force and International Law, 4 (1), 110–160.

Nye, J. S. (1990). Soft power. Foreign Policy, 80 , 153–171. https://doi.org/10.2307/1148580 .

Reuters. (2022, January 21). U.N. chief condemns deadly Saudi-led coalition strike in Yemen. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/several-killed-air-strike-detention-centre-yemens-saada-reuters-witness-2022-01-21/.

Rotberg, R. (2016). Failed states, collapsed states, weak states: Causes and indicators. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/statefailureandstateweaknessinatimeofterror_chapter.pdf .

Stenslie, S. (2013). Not too strong, not too weak: Saudi Arabia’s policy towards Yemen. Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/162439/87736bc4da8b0e482f9492e6e8baacaf.pdf .

Wehrey, F., et al. (2009). Assertiveness and caution in Iranian strategic culture. In Dangerous but not omnipotent: Exploring the reach and limitations of Iranian power in the Middle East (pp. 7–38). Rand Corporation.

Vatanka, A. (2014). Iran, Saudi Arabia find common ground in Yemen. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2014/11/iran-yemen-saudi-arabia-houthi-islah.html .

Author and Mentor Bios

Bryn Lauer will graduate from the University of New Hampshire in spring 2022 with a bachelor of science degree in business administration: finance. She hopes to pursue work as a financial economist with a concentration in international affairs. Originally from Durham, New Hampshire, Bryn became interested in international conflict after taking some international politics classes and participating in an internship at the U.S. Department of State. Because of Yemen’s unique position as a failed state, Bryn wanted to understand the motivations of outside actors intervening and how their actions impacted the conflict there. To pursue her research interests, Bryn received an Undergraduate Research Award through the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research. From the project Bryn gained a deep understanding of the history of Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Houthis, as well as learned a lot about the research process itself. Given the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bryn unfortunately was unable to conduct field research abroad, so she had to rely only on information that was published in databases. This presented a challenge for Bryn, because she had to be able to work through contradicting data to find information that focused specifically on the effects of external intervention of foreign states. Despite the challenges, Bryn was able to piece together the data, history, and geopolitics to develop her own theories, making the research her own.

Elizabeth Carter has been an assistant professor of political science at the University of New Hampshire since 2015. She specializes in comparative politics, political economy, and Western European politics. Dr. Carter met Bryn in her U.S. and World Affairs course and was delighted to serve as her research mentor after being impressed with an essay on Yemen that Bryn had written for the class. Though she has mentored several undergraduate students for both undergraduate honors theses and as part of Hamel Center Undergraduate Research Awards, this was Dr. Carter’s first time mentoring a student who submitted an article to Inquiry . Dr. Carter is proud of the great work that Bryn conducted. In addition, Dr. Carter says that it was wonderful to have the experience of enhancing her understanding of a region, like Yemen, that she had not researched much herself, especially with the rigorous research and applications of political science theories and framework that Bryn incorporated into her work. Dr. Carter believes that it’s important for researchers to make research more accessible to broader audiences across multiple disciplines, not just to those engaged in that particular field.

Contact the author

Copyright 2022, Bryn Lauer

- Research Article

Inquiry Journal

Spring 2022 issue.

- Sustainability

- Embrace New Hampshire

- University News

- The Future of UNH

- Campus Locations

- Calendars & Events

- Directories

- Facts & Figures

- Academic Advising

- Colleges & Schools

- Degrees & Programs

- Undeclared Students

- Course Search

- Study Abroad

- Career Services

- How to Apply

- Visit Campus

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Net Price Calculator

- Graduate Admissions

- UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law

- Housing & Residential Life

- Clubs & Organizations

- New Student Programs

- Student Support

- Fitness & Recreation

- Student Union

- Health & Wellness

- Student Life Leadership

- Sport Clubs

- UNH Wildcats

- Intramural Sports

- Campus Recreation

- Centers & Institutes

- Undergraduate Research

- Research Office

- Graduate Research

- FindScholars@UNH

- Business Partnerships with UNH

- Professional Development & Continuing Education

- Research and Technology at UNH

- Request Information

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- The war in Yemen, as seen by ordinary Yemenis

Bushra al-Maqtari has collected their testimonies in “What Have You Left Behind?”

What Have You Left Behind? By Bushra al-Maqtari. Translated by Sawad Hussain. Fitzcarraldo Editions; 256 pages; £12.99

F OR a conflict that has caused arguably the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, the war in Yemen is often described in the most inhuman ways. It is another front in the long struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran, or one of those bewildering civil wars that defies comprehension. It is a morality play for Americans frustrated with their country’s relationship with Saudi Arabia. It is a full-employment programme for foreign diplomats fond of banal statements about peace talks.

Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

In “What Have You Left Behind?” Bushra al-Maqtari, a journalist, adds a human element to the conflict. This is not the sort of book you take to the beach or skim before bed. Ms Maqtari started touring her country in 2015 to collect testimonies from ordinary Yemenis. What emerged is simply a string of those testimonies, each one more horrific than the last.

Here is Adel Rassam, recounting his family’s flight from the port city of Aden as militias approached: “Panic filled the air like a restless spirit in the wind.” There is Hafsa Munawis, whose sister was killed when their workplace, a potato-chip factory in Sana’a, was hit by an airstrike. “The missile had landed in the fryer with all that boiling hot oil.” Tahani al-Qudsi’s daughters and niece were killed by militia shelling in Taiz. “Pain is engraved on our faces,” she says. “Just write what you see.”

Each chapter ends with a list of the names and ages of those killed in the events just recounted. The names are too many, the ages often far too young. Some were killed by the Houthis , a Shia militant group that seized the capital in 2014 and still controls much of the country. Others were killed by a coalition of Arab countries, led by Saudi Arabia , that invaded the following year to dislodge the Houthis.

The identities of their killers do not much matter: this is not a war story, as war stories are often told. There are no heroes. The antagonists are never glimpsed. No one delivers stirring paeans to freedom or the glorious nation. There is only death, suffering and fear. “Only victims are real in this war, victims crushed by violence,” Ms Maqtari writes in her introduction.

But even trying to humanise the war underscores its inhumanity. Some of Ms Maqtari’s subjects reminisce about the past. Rarely do they imagine the future. Neither the Houthis nor the coalition have grand plans for rebuilding a shattered country. The goal is simply to wield power. “What are they fighting over? What is worth all this death?” asks one interviewee, Munira al-Hamidi. She answers her own question: “Neither of them have a reason.”

These words ring true elsewhere in the region as well. In Libya and Syria killing became a goal in and of itself. In places like Iraq and Iran, state violence plays a similar role, albeit on a lesser scale: it is a way for corrupt, useless factions to stay in office. Too much of the Middle East is a zero-sum competition for power.

The war in Yemen is now in its eighth year. That it has dragged on so long is partly thanks to the input of external actors. No one in Ms Maqtari’s book mentions America or Iran directly. Even Saudi Arabia appears infrequently, and often as a footnote. Yet they loom large in every anecdote. The bombs dropped by coalition aeroplanes were probably made in America; the guns used by militiamen may have been supplied by Iran.

No one mentions the UN either. Since April, when it first brokered a two-month ceasefire, violence in Yemen has been ebbing. The truce was prolonged twice. Diplomats were optimistic that this might herald a lasting peace. Yemenis were not.

Sure enough, earlier this month, the truce lapsed: the Houthis would not agree to another extension. Many Yemenis worry that the lull will soon end. The UN has raised less than half the money it needs for humanitarian aid; a new eight-man presidential council meant to broker an end to the conflict is busy arguing among itself. The combatants may no longer know why they are at war. But for the victims, the fighting is all too real. ■

This article appeared in the Culture section of the print edition under the headline “No heroes, only victims”

Culture October 29th 2022

- Binyamin Netanyahu’s memoir is a fascinating study of power

- The joys of pan de muerto, a sweet tribute to departed loved ones

- Siddhartha Mukherjee’s new book is a tour d’horizon of cell theory

- Pinocchio is the hero of our time

- “Papyrus” is a lively history of books in the ancient world

From the October 29th 2022 edition

Discover stories from this section and more in the list of contents

More from Culture

Cautious optimism reigns at Art Basel this year

The continued downturn many feared seems not to have materialised

Exit Kohli? T20 cricket is about to change

The shortest form of the game is becoming even more fiery

What a row over sponsorship reveals about art and Mammon

It betrays childish misconceptions about money, morality and power

How Les Bleus went from zeroes to heroes

“Va-Va-Voom” chronicles the turnaround of the French men’s national team

Famous Birthdays wants to be the Wikipedia for Gen Z

From mega to micro stars, this is a validation that cannot be paid for

Is now the right time to publish a novel by Louis-Ferdinand Céline?

A newly translated book by an antisemitic French novelist is sure to spark debate

- Get involved

- Assessing the impact of war in Yemen - English pdf (8.8 MB)

- تحميل التقرير باللغة العربية pdf (8.8 MB)

- Assessing the impact of war in Yemen - German pdf (13.9 MB)

- Assessing the impact of war in Yemen - Japanese pdf (26.4 MB)

Assessing the Impact of War in Yemen: Pathways for Recovery

November 23, 2021.

We are pleased to present the third and final report of the Impact of War trilogy series. UNDP Yemen has once again partnered with the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures. The report, Assessing the Impact of War in Yemen: Pathways for Recovery , continues to apply integrated modeling techniques to better understand the dynamics of the conflict and its impact on development in Yemen.

Released in November 2021, this report explores post-conflict recovery and finds that war has continued to devastate the country; the conflict’s death toll has already grown 60 per cent since 2019. However, if a sustainable and implementable peace deal can be reached, there is still hope for a brighter future in Yemen.

Seven different recovery scenarios were modeled to better understand prospects and priorities for recovery and reconstruction in Yemen. The analysis identified key leverage points and recommendations for a successful recovery – including empowering women, making investments in agriculture, and leveraging the private sector. Moreover, by combining these, it is possible to save hundreds of thousands of additional lives and put Yemen on a path not only to catch up with – but to surpass – its pre-war SDG trajectory by 2050.

Through achieving a peace deal, pursuing an integrated recovery strategy, and leveraging key transformative opportunities, it is indeed possible for Yemen to make up for lost time and offer better opportunities to the next generation.

PREVIOUS REPORTS

In April 2019, the first of three reports, Assessing the Impact of War on Development in Yemen , commissioned by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Yemen, revealed that the war had already set back development by more than two decades and caused more deaths from indirect causes such as hunger and disease than deaths from conflict-related violence.

The second report, Assessing the Impact of War in Yemen on Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) , released in September 2019, predicted that if conflict persists past 2019, Yemen will have the greatest depth of poverty, second poorest imbalance in gender development, lowest caloric intake per capita, second greatest reduction in economic activity relative to 2014, and second greatest income inequality of any country in the world.

Document Type

Regions and countries, sustainable development goals, related publications, publications, promoting an open and inclusive public sphere.

This set of three documents outline how UNDP leverages its unique comparative advantage to advance the principles of openness and inclusion within governance sy...

Putting a Stop to Gender Violence through Community Actio...

This brief shares the successes and lessons learned of the methodology used to inform and encourage the creation of women leaders networks in other contexts and...

The politics of inequality: Why are governance systems no...

Starting from a theoretical framework that conceptualizes policy outcomes as the result of complex interactions between actors, institutions and discourses, thi...

Guidance Note on Supporting Community-Based Reintegration...

Communities are increasingly recognized as playing a fundamental role in addressing the challenges and opportunities involved in the reintegration of individual...

Pathways to Achieving the Global 10-10-10 HIV Targets

This review focuses on initiatives led by key populations and people living with HIV documented in peer reviewed and grey literature published between January 2...

Navigating Towards a Nature-Positive Future: Strategic Up...

This report outlines the progress of the knowledge uptake efforts in eight countries: Cameroon, Colombia, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, Trinidad and Tob...

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, unpacking the european parliament election results, u.s.-india clean energy partnership for 450 gw, nuclear weapons and foreign policy: a conversation with hpsci chairman mike turner, biotech innovation and bayh-dole: a fireside chat with gillian m. fenton.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Critical Minerals Security

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation Project

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- Warfare, Irregular Threats, and Terrorism Program

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

The War in Yemen: Hard Choices in a Hard War

Photo: Saleh Al-Obeidi/AFP/Getty Images

Table of Contents

Report by Anthony H. Cordesman

Published May 9, 2017

Available Downloads

- Download PDF file of "The War in Yemen: Hard Choices in a Hard War" 1468kb

By Anthony H. Cordesman

The Middle East is filled with grim wars in failed states—Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen—none of which have good options for a lasting peace. The situation in Yemen, however, has moved beyond crisis, to the point of humanitarian nightmare. It has become a stalemate where the casualties from actual combat are limited, but where the fighting has produced a stalemate that has left the entire country without meaningful governance and security, and has crippled an already desperately poor economy.

The Burke Chair at CSIS has released a new report on the war in Yemen, entitled “The War in Yemen: Hard Choices in a Hard War.” The report is available on the CSIS web site at: csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/170509_Yemen_Hard_Choices_Hard_War.pdf?Hv3JAIjcvSh5eBGPB44sP4r4lCn1kJyG

At present, Yemen remains divided between two major factions: a mix of Houthi Shi’ite rebels and military supporters of its former president Ali Abdullah Saleh , and the Saudi and UAE-backed faction that supports a government led by his replacement in a one candidate election: Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi.

Some two years of fighting have reached a near stalemate in which the Houthi-Saleh faction controls the capital and much of the populated northwest, and the Saudi-UAE-Hadi faction have taken Aden and other cities, and has a decisive edge in air power, but lack the ground forces to drive the Houthi-Saleh faction out of the areas it now controls. At the same time, other warring factions like Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and various tribal groups add to the fighting and instability in much of the rest of the country.

The result has become a massive humanitarian crisis that will continue to grow until the fighting ends. It has already inflicted a level of economic damage so serious that Yemen may take a take a decade or more to fully recover—even if the fighting does not resume and some form of effective national unity and governance is established.

Like Syria and Somalia, Yemen is a nation that lacks the resources to quickly recover. Worse, it has become a nation that will then find it difficult to move towards some form of sustained post-war development. No one can help Yemen unless it can acquire a level of unity and quality of governance that will allow it to help itself, but even then, it will have no clear prospect of growth and stability without massive outside aid.

This presents major problems in terms of conflict termination, and in finding some kind of U.S. policy option that can help give Yemen a meaningful future. Putting an end to the conflict can only be a first step in easing Yemen’s growing agony. No ceasefire or settlement that leaves a weak, ineffective, and divided government in power can end Yemen’s humanitarian crisis or allow it to move forward.

Real peace and stability can only come if Yemen can reach a level of unity it has lacked in the past, create a modern enough central government to actually focus on recovery and development, and attract major levels of outside aid. Simply ending the fighting may reduce its level of suffering in the short term, but will inevitably prolong it and may well be a prelude to new levels of conflict.

This presents the problem that the United States must seek some solution that will either fully defeat the Houthi and Saleh faction, or find some kind of compromise that will lead the Houthi-Saleh faction to accept an effective central government. At the same time, even the most decisive military victory by the Saudi and UAE-backed government of Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi offers little hope of effective leadership. The Hadi government may be more secular and free of Iranian influence, but it is far from clear it can lead or govern effectively.

Like America’s role in its other “failed state wars,” winning a war will only be meaningful if it is the prelude to winning a peace. Like it or not, this means giving nation building the same priority as winning some form of military victory. If anything, this may well be the greater challenge.

Read the entire report at https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/170509_Yemen_Hard_Choices_Hard_War.pdf?Hv3JAIjcvSh5eBGPB44sP4r4lCn1kJyG

Anthony H. Cordesman

Programs & projects.

- Terrorism and Counterinsurgency

- Patterns in Global Terrorism

- U.S. Strategic and Defense Efforts

- MENA Stability Reports and Studies

- Saudi Arabia, the GCC, and the Gulf

- Doctoral Students

- Counter/Argument: A Middle East Podcast

- By Discipline

- Middle East Briefs

- Crown Conversations

- On Hamas and Israel

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events and Recordings

- Open Positions

- Research and Study Grants

- Scholarships, Fellowships and Internships

- Degree Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Brandeis Online

- Summer Programs

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Financial Aid

- Summer School

- Centers and Institutes

- Funding Resources

- Housing/Community Living

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Our Jewish Roots

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Administration

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- 75th Anniversary

- Campus Calendar

- Directories

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Crown Center for Middle East Studies

Understanding yemen: before, during, and after conflict.

A Conversation with Yasmeen al-Eryani and Stacey Philbrick Yadav