Journalism | Definition, Purpose & Types

Corrie Whitmer has worked in the professional writing field for four years. She has a master’s degree in professional writing from Carnegie Mellon University and a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. She has been published in Pharmacy Today magazine and Unfading Daydream.

Ashley has a JD degree and is an attorney. She has extensive experience as a prosecutor and legal writer, and she has taught and written various law courses.

Maria has taught University level psychology and mathematics courses for over 20 years. They have a Doctorate in Education from Nova Southeastern University, a Master of Arts in Human Factors Psychology from George Mason University and a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Flagler College.

Table of Contents

What is journalism, the purpose of journalism, why is journalism important, journalism terms.

- Types of Journalism

What Do Journalists Do?

Lesson summary, critique the journalist.

In this activity, students will use what they have learned to critique multiple styles of journalism.

- Popular magazines (Teen Fashion, Psychology Today, People)

- Newspapers (local and nationally recognized)

- Other periodicals/news magazines (Wall Street Journal, News Day)

- Internet published news sites

Instructions

- Choose at least three articles from different styles of journalistic reporting. Make sure at least one is from a popular magazine and one is from an internet news site.

- The answers to the five 'Ws' given in the lesson.

- The level of objectivity and lack of bias apparent in the article.

- Evidence of verification attempts and accuracy in reporting.

- Were they all as good at answering the five main questions?

- Did they all show objectivity and lack of bias?

- Were they all verified and accurate?

- Do you think newspapers offer more journalistic attributes than magazine articles do? Why or why not?

- Does it matter how well known the source of the material is? Why or why not?

- Finally, reflect on how journalists can influence their readers through the use of, or lack of use of, good journalism.

- How does this rather suspect source compare to the others you have chosen?

- Does it pass the requirements of objectivity, bias, verification and accuracy?

- The five Ws are answered in this article, but in vague terms such as 'last year' instead of a specific date.

- The journalist does not seem to exhibit any bias and the writing is objective, giving both sides of the issue.

- Verification is the area in which this piece of journalism weakens drastically. The author verifies information through unnamed sources that have dubious links to the main subjects of the article. It is impossible to tell if the information is accurate based on this article.

What do journalists do on a daily basis?

What journalists do every day varies heavily by what type of journalism they do. However, all journalists do research, talk to sources, and organize information into informative stories.

What skills do you need to be a journalist?

Journalists need to be able to do investigations, conduct interviews, and put information together in ways that make sense. Thus, they need to be excellent at research, one-on-one communication, and writing.

What is the role of a journalist?

Journalists gather information on a topic and then organize it into an engaging and clear story. They may do this for a newspaper, a TV news outlet, a podcast, or any other communication media.

What is the main purpose of journalism?

The main purpose of journalism is to provide the public with accurate, timely information about the world. Journalists inform their audience by reporting on what is most relevant to them.

A basic journalism definition is the gathering, assembling, and presentation of news . Journalists produce many different types of content for various media, but their work is tied together by the fact that they all focus on nonfiction information related in some way to current events. Additionally, journalism is usually performed in association with some sort of news outlet that gathers journalistic pieces and provides them to the public.

So, as an example, a nonfiction article on a recent election would qualify as journalism, while a nonfiction discussion of construction methods used by the Aztec Empire would not. However, an archaeological dig discovering new information about Aztec construction would be an appropriate topic for a journalism piece. Exactly how recent the news imparted in a journalism piece is varies heavily, but in general journalistic pieces will be tied to something recent enough that it could have an impact on reader's lives in some way.

To unlock this lesson you must be a Study.com Member. Create your account

An error occurred trying to load this video.

Try refreshing the page, or contact customer support.

You must c C reate an account to continue watching

Register to view this lesson.

As a member, you'll also get unlimited access to over 88,000 lessons in math, English, science, history, and more. Plus, get practice tests, quizzes, and personalized coaching to help you succeed.

Get unlimited access to over 88,000 lessons.

Already registered? Log in here for access

Resources created by teachers for teachers.

I would definitely recommend Study.com to my colleagues. It’s like a teacher waved a magic wand and did the work for me. I feel like it’s a lifeline.

You're on a roll. Keep up the good work!

Just checking in. are you still watching.

- 0:02 What Is Journalism?

- 2:05 The Role of Journalism

- 3:03 Objectivity & Bias

- 5:09 Verification & Accuracy

- 6:11 Lesson Summary

When producing pieces, journalists work to providing the public with information that is relevant to their lives. It is important that journalism is not only accurate but also useful. The best journalism informs about events, issues, and people that impact society or affect daily life.

In a democratic society, journalism takes on the additional role of ensuring that citizens have the information they need to understand their government and vote in their best interests. Democratic societies function best when the voters understand the candidates and the issues at play in their elections; journalism is key to disseminating this information. In addition to providing information to voters, journalists can uncover corruption and act as whistleblowers.

Journalism is an essential component of a democratic society. Nations with freedom of the press tend to function better than those with restrictions on journalists. Countries with extensive restrictions on their press are often not democratic at all.

| Country | 2020 World Press Freedom Ranking | 2020 EIU Democracy Ranking | Example of Press Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | 1 | 1 | In 2004, Norway updated the clause in their constitution that guarantees freedom of the press to further indicate that the government is responsible for ensuring a thriving, diverse news media sector. |

| Costa Rica | 5 | 18 | Costa Rica is famed for being one of the best countries for journalists in Latin America. News outlets in Costa Rica provide consistent coverage of the environmental issues facing the country and of electoral news. |

| Italy | 41 | 30 | In the 1970's, journalist Roberto Saviano published his investigation of organized crime in Naples in the book . He was placed under police protection after its publication. |

| USA | 44 | 25 | The US press has also taken an active role in uncovering government corruption, from the 1972 Watergate scandal to recent investigations into racial bias in policing. However, the country also has an uneven record of whistleblower protections and has jailed several whistleblowers, including Chelsea Manning and David Hale. |

| Russia | 150 | 124 | Russia is known to retaliate against journalists who criticize its government. Anna Politkovskaya, known for covering human rights violations by the Russian government in Chechnya for Moscow newspaper , was jailed, threatened, and even poisoned over the course of her career. She was killed in 2006, and the head of surveillance for the Moscow police force was among those jailed for involvement in her death. |

| China | 177 | 151 | Chinese citizen journalist Zhang Zhan, whose smartphone videos criticized the Chinese government's handling of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, was given a four-year jail sentence in May 2020 on charges of "picking quarrels and provoking trouble." This charge is frequently used against government critics in China. |

Journalists call the first part of a written news piece the lede (also spelled lead). Ledes vary in length from a single sentence to a paragraph, but all are written with the purpose of drawing readers into their story. The most common structure for a news story is the inverted pyramid (also called funnel), in which the information in the piece is organized from most to least important.

Journalists also have specialized words for various parts of the journalistic process. For example, doing research for a story is called investigating , providing detailed nonfiction information on a topic is reporting , and getting information from someone by talking to them is called interviewing . People interviewed for a story are known as sources . A press conference is an event at which a politician or public figure speaks to a large number of journalists at once.

A key concept within journalism is the "Five W's" used by journalists. These five questions guide journalists while they identify, investigate, and report on news. The "Five W's" are:

- Who: Who was involved?

- What: What occurred?

- Where: Where did this occur?

- When: When did it happen?

- Why: Why did it happen?

A good news story should address every one of these questions.

There are as many types of journalists as there are journalistic subjects. Here are some common types of reporters who work for news media, along with definitions of their areas of focus.

- Breaking news reporters cover recent events of public interest. They can be considered generalists, and often write about a variety of subjects. These journalists are the ones most people think of when asked about the definition of a reporter

- Investigative reporters produce detailed, long-form reports on subjects that are poorly or incompletely understood by the general public. Most, but not all, investigative reporting focuses on corruption or systemic failure in governments or the private sector.

- Crime reporters focus on news about criminal justice. They cover arrests and trials, as well as trends among criminals and how citizens can protect themselves from various crimes.

- Politics reporters focus specifically on political topics. Their work encompasses elections, new laws, political scandals, and other subjects related to the government

- Health and Wellness journalists focus on news that is relevant to health and healthcare. Their articles concern research into various diseases, dieting trends, new information about various medications, and other topics relevant to public health.

- Arts and Lifestyle reporters focus on culture, media, and leisure topics. These reporters produce content such as movie reviews, recipes, articles on interior design, and advice columns.

- Sports reporters cover sports, from local children's leagues all the way up to the Olympics .

- Celebrity reporters write about prominent people, including actors, musicians, and influencers. They may conduct interviews with their subjects or simply report on their recent actions.

- Editorial, opinion, and op-ed writers produce articles with a clear, stated bias, often with the goal of persuading readers to agree with their opinions. Some media organizations keep an opinion writer on staff, while others rely on guest writers for this content.

There are dozens of different ways to communicate news, meaning that journalism jobs vary heavily depending on what news medium the journalist is working in and what kind of news they report on. However, almost all journalism jobs have some tasks in common. Journalists across mediums work to identify interesting news, do research on the subject of their stories, and identify potential interview subjects. Nearly all journalists conduct interviews, arrange the information they've gathered into a coherent story, and then work with editors to ensure that their work is high quality.

A sports journalist who works for a local paper might start this process by checking the local sports schedule. They attend games, interview coaches and players, and possibly even take some of their own photographs. After submitting a draft to their editor, they incorporate any suggestions the editor made and then submit their work for publication. At any given moment, they are probably working on several stories at once.

A politics journalist who works for a national news show would similarly work on multiple stories at once. But their stories would start with official press releases or social media posts from politicians. Unlike the local sports journalist, who typically takes notes or makes an audio recording of interviews, they conduct interviews on camera, some of them live. Their editing process involves splicing interview clips together into a brief, informative story.

The Role of a Journalist

Journalists are responsible for providing their audience with timely, factual information about the world around them. They gather information and present it to their audience in a logical and engaging way. Because they report on news, journalists are sometimes also called reporters . The definition of reporter and that of journalist are usually interchangeable, but the latter is considered more formal.

Journalists do not work alone; they collaborate with people in other roles to get out the news. But while both a news producer and a journalist have a role in deciding what news will be presented and how, the journalist is the one who actually does the investigation. Similarly, newscasters play a big role in presenting the news, but they are only journalists if they are also the ones responsible for gathering the information they present.

The news industry id often referred to as the media . A news media definition would be the entirety of outlets engaged in the business of delivering the news through print, broadcast and online vehicles.

Objectivity and Accuracy

Journalism is valuable to society because, in its best form, it provides the public with trustworthy information about current events. As a result, journalists often prioritize objectivity and balance while discussing the news. When a journalist talks about being objective, they mean ensuring that they are presenting news in a way that doesn't incorporate their own emotions or seek to influence those of the reader. Balance in a news story means that if the news story discusses a contentious topic, all sides of the issue are given equal attention. Reputable journalists are very careful about avoiding even the appearance of bias; they know that if they fail to be objective and balanced in their reporting, their audience will no longer trust them.

To ensure the accuracy of their work, journalists also put emphasis on verification . In other words, they strive to ensure that any information they present can be backed up, preferably with multiple sources. This ensures that the work they do is accurate, or truthful.

When journalists neglect these values, the results are often serious. During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, Fox News repeatedly released false or misleading stories and social media posts that were critical of the COVID-19 vaccine and vaccine mandates. These stories ultimately contributed to vaccine skepticism and refusal in the US. In addition to incorrect reports from respected outlets, modern social media is full of completely fabricated news, often from made-up outlets, that is passed around without context or fact-checking.

In contrast, when a responsible journalist notices that they have presented something untrue as fact, they will often print a retraction . Retractions are corrections to published stories that often appear at the end of the piece.

Journalism is the name for a profession in which people gather information, put it together in ways that are easy to understand, and present it to the public. Journalists specifically focus on providing factual accounts related to recent events. Journalists use a variety of different types of media to convey information, but they share a primary goal of informing media consumers. In democracies, journalism is also critical to ensuring that voters are informed about their government and the issues at play in elections. More democratic societies generally have better protections on freedom of the press.

Journalists call the first section of a news article the lede , while the typical structure of an article is called the inverted pyramid. Journalists refer to the process of researching for a story as investigating , while they call talking to someone as part of that research an interview . The people they interview are called sources, and a meeting during which a public feature speaks to many journalists at once is a press conference. Journalists also use a set of questions known as the "Five W's" (who, what, where, when and why) as a structure for gathering and organizing information.

There are a variety of different types of reporters, each focused on different types of news. The precise tasks a journalist does each day vary heavily depending on their medium and the type of journalism they do, but all journalists gather information, craft it into a coherent story, and present it to the public. As journalists are responsible for reporting on news, they are also known as reporters.

Objectivity and balance are extremely important to journalists. An objective reporter avoids any choices that could indicate that their opinions are affecting how they cover a topic. Meanwhile, balance means showcasing every side of any issue they discuss. Journalists also endeavor to provide accurate information by ensuring that their stories can be verified by multiple sources. Journalists who are careless about accuracy and bias can do real damage. If a journalist publishes something false, the correct thing for them to do is to issue a retraction that acknowledges the issues with what they initially published.

Video Transcript

What is journalism.

One person was taken to the Burn Center at Parkland Hospital after flames ripped through an East Dallas apartment complex.

This was the first line of a current newspaper article. Did you read a newspaper this morning? Maybe you watched the news on television or heard headlines broadcast on the radio. These are forms of journalism . Journalism is the act of gathering and presenting news and information. The term 'journalism' also refers to the news and information itself. It's important to notice the variety of information media today. The news and information can be presented in many different ways, including articles, reports, broadcasts, or even tweets.

Journalism is a form of communication, but it's distinct from other forms. It is unique because it's a one-way message, or story, from the journalist to the audience. It's most unique because the message isn't the journalist's personal story or subjective thoughts. Instead, the journalist acts as a conduit, narrating an objective story about something that happened or is happening, based on his or her observations and discoveries. This type of storytelling comes in many different forms, including:

- Breaking news

- Feature stories

- Investigative reports

Journalism's unique storytelling comes in the form of reporting. To report simply means to convey the facts of the story. Even in editorials and reviews, the journalist is conveying facts about the experience. The story can be analytical or interpretive and still be journalism. In general, reporting comes from interviewing, studying, examining, documenting, assessing, and researching. New journalists are often taught to report on the five Ws , so you'll notice that most pieces of journalism include some or all of these:

- Who was it?

- What did they do?

- Where were they?

- When did it happen?

- Why did it happen?

The Role of Journalism

Journalism serves many different roles. Foremost, it serves to inform the public. It's an open medium, meaning the intended audience includes the entire community or public. Once the journalist reports the information - or sends the communication - that information is available to anyone wishing to receive it.

For that reason, journalism is an essential component in a democratic society. The freer the society, like the United States, the more news and information is available to the public. Citizens tend to be well-informed on issues affecting their communities, government, and everyday dealings. On the other hand, North Korea allows only limited access to independent news sources and almost no access to the Internet. The vast majority of news and information comes from the official Korean Central News Agency, which reports mainly on statements from the political leadership. This leaves citizens with only one, filtered point of view.

Objectivity & Bias

This type of bias is a key issue in journalism. Journalism is based on objectivity , meaning journalists must make every effort to report the news and information without allowing their preconceptions to influence the stories. There's a general acceptance that journalists, like all people, have inherent personal and cultural biases. These prejudices can be positive, negative, or neutral, and many are subconscious. Some biases are even thought to be organization-wide. For example, many people believe Fox News is biased toward the Republican Party, while MSNBC is biased toward the Democratic Party.

In the early 1900s, especially in the 1920s, there was a concerted push toward greater objectivity in journalism. After years of political propaganda and reporting based simply on 'realism', experts pushed for a consistent process for testing information that more closely resembled a scientific method.

When previously using a theory of realism, journalists were only tasked with finding and presenting the information. The common belief was that the truth would naturally surface through the conveyance of facts in the proper order - from most important to least important. However, the 'facts' were often slanted and ordered according to the journalist's prejudices.

Using a theory of objectivity, the facts are tested prior to reporting so that the information is conveyed in a transparent manner. This might mean the journalist manages his or her bias, rather than completely removing it. For example, this lesson expresses a bias toward a free society with an open media forum. To be transparent simply means to present the facts so that the audience can decide for themselves what to believe.

Today's journalism students are taught to study the evidence, check their sources, and validate all information. There isn't a common method for achieving objectivity, though most journalists say they've learned the art of objective reporting by working with and observing other, more seasoned journalists.

Verification & Accuracy

The main goal is to present truthful and accurate information through verification , or making sure that the information is accurate. This requires not just gathering and presenting, but assessing.

Many experts believe accuracy to be the first tenet of journalism. Journalism is a conveyance of facts, and is therefore non-fiction. Journalists and organizations lose credibility when they misrepresent the facts. For example, CNN and several other news organizations came under fire when they prematurely announced an arrest had been made in the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings. In fact, the arrest was made more than two days later.

One way to achieve accuracy is, again, through transparency. Journalists are encouraged to give their audiences all of the information they gathered. This might mean gathering sources from many different sides of an issue, and admitting what they don't know about a story. That way, audiences can verify the information for themselves.

Journalism is the act of gathering and presenting news and information, though the term is also used to refer to the news and information itself. It's a type of storytelling that comes in many different forms and is a key component to a democratic society.

Journalism can come in many forms, from newspaper articles to live tweets at an event. Journalists are taught to focus on the five Ws which are the who, what, where, why, and when of a story.

However, journalists must be careful to manage bias and report with objectivity , or a management or lack of personal or cultural bias. This means journalists must make every effort to convey information without allowing their preconceptions to influence the stories. To boost credibility, journalists must verify , or make sure of the accuracy of their information so they report with accuracy. This means they must assess the information before presenting it.

Unlock Your Education

See for yourself why 30 million people use study.com, become a study.com member and start learning now..

Already a member? Log In

Recommended Lessons and Courses for You

Related lessons, related courses, recommended lessons for you.

Journalism | Definition, Purpose & Types Related Study Materials

- Related Topics

Browse by Courses

- Economics 101: Principles of Microeconomics

- CLEP Principles of Management Prep

- Quantitative Analysis

- Business 111: Principles of Supervision

- Business 109: Intro to Computing

- CLEP Financial Accounting Prep

- Principles of Management: Certificate Program

- CLEP Principles of Macroeconomics Prep

- Introduction to Financial Accounting: Certificate Program

- Financial Accounting: Homework Help Resource

- Financial Accounting: Tutoring Solution

- UExcel Introduction to Macroeconomics: Study Guide & Test Prep

- Business 104: Information Systems and Computer Applications

- Effective Communication in the Workplace: Certificate Program

- Effective Communication in the Workplace: Help and Review

Browse by Lessons

- Introduction to Journalism: History & Society

- Contemporary Journalism & Its Role in Society

- Herfindahl Index Overview, Formula & Scale

- Income Elasticity of Demand: Definition, Formula & Example

- Income Elasticity of Demand | Formula & Examples

- Direct vs. Indirect Labor | Definition, Costs & Examples

- Inflationary Gap Definition & Calculations

- Census Definition, Purpose & Procedure

- Econometrics | Definition, Method & Examples

- Plowback Ratio | Meaning, Formula & Calculation

- Intrinsic Value of Stocks Example & Calculation

- World Economy | Overview, Statistics & History

- Building Relationships in the Workplace

- Managing Different Generations in the Workplace

Create an account to start this course today Used by over 30 million students worldwide Create an account

Explore our library of over 88,000 lessons

- Foreign Language

- Social Science

- See All College Courses

- Common Core

- High School

- See All High School Courses

- College & Career Guidance Courses

- College Placement Exams

- Entrance Exams

- General Test Prep

- K-8 Courses

- Skills Courses

- Teacher Certification Exams

- See All Other Courses

- Create a Goal

- Create custom courses

- Get your questions answered

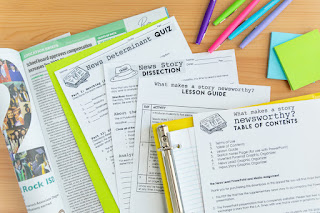

Teaching Journalism: 5 Journalism Lessons and Activities

You and your students will absolutely love these journalism lessons! The beginning of a new school year can be hectic for journalism teachers who are tasked with simultaneously teaching new journalism students who don’t have any journalism experience while also planning and publishing content for the school newspaper.

If your class is anything like mine, it is a mix of returning and new students. This year, I only have three returning students, so it is almost like I am starting entirely from scratch.

Here are 5 journalism lessons to teach at the beginning of the year

1. staff interview activity.

One of the very first assignments I have my students do is partner up with a fellow staff member that they don’t know and interview them. This activity works on two things: first, it helps the class get to know one another. Secondly, it helps students proactive their interviewing skills in a low-stakes environment.

For this activity, I have students come up with 10 interview questions, interview one another and do a quick write-up so that students can have practice recording their interviews.

Before this activity, I go over interviewing skills with my students. We discuss the dos and don’ts of interviewing, we brainstorm good interviewing questions, and we talk about the need to go beyond simple answer questions.

2. Staff Bio

Another great activity for the beginning of the year is to have students write their staff bio. This provides students with an opportunity to write in the third person while also providing the most important information.

For my staff bios, I give students 80-100 words. I have them write their bios in the third person and in the present tense.

3. Collaborative News Story

For our first news story of the school year, I like to write one collaboratively as a staff. We go over the basics of journalism writing and then write together in one Google Doc. I do this as a learning activity so that new staff can see how we write journalistically. First, I have students work together in small groups to write the lead. Then, as a class, we craft one together. From there, we move on to building the story.

As we write the story, as a staff, we can then see what kind of information we need. I assign small groups of students to interview people and find quotes. Those groups then add that information to the story.

Once it is written, we edit and review the story together before it is published. This activity is particularly helpful because students get to see how we format quotes in our stories, how we refer to students and teachers in our stories, and how we go about the news-gathering process.

Once our collaborative story is done, new staff then have the green light to begin writing their own stories.

4. The News Determinants

You can also read more in-depth about the news determinants with this blog post about teaching the five news determinants .

5. AP Style Writing

As students are writing their first stories, I like to teach students about AP Style . I use this instructional presentation, and students assemble their AP Style mini flip books that they use as a reference all year long.

The news determinants and AP Style lessons are included in my journalism curriculum with many other resources that will make teaching and advising the middle school or high school newspaper much easier.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

Journalism Online

Real Information For Real People

What is Journalism? 7 Answers for Future Journalists

Most of us know the Five Ws (and H) that are otherwise known as reporters’ questions. Did you know WHO developed them? We give credit to an English rhetorician named Thomas Wilson (1524-1581). He introduced the method in 1560, calling them the “seven circumstances” of medieval rhetoric. In his version, the seven questions were who, what, where, by what or whose help did events occur. Next are why, how, and when. Combined, these questions form the foundation of journalism.

In the centuries since, journalism has developed into both an art form as well as a formal profession. What is Journalism? It’s far more than just reporting. Being a journalist means embracing an identity that involves a specific set of values that journalists and reporters have clung to through every historical, political, and cultural change since the Middle Ages.

WHAT Is Journalism?

As a discipline, Journalism is the gathering, preparation, and distribution of news, features, and commentary. Delivery platforms are print as well as digital media. Printed media includes traditional newspapers, books, and magazines. Electronic media consists of a myriad of outlets, including blogs, podcasts, social media, radio, and television.

In all elective democracies, journalism is a professional identity for journalists who identify their role within society as an exclusive one. In the United States and other democratic nations, journalists have vehemently defended their profession, ethics, and ideology.

WHEN Does Journalism Support Democracy?

The link between democratic societies and journalism generates more questions about the nature of the profession. It also makes you wonder how and why the definition of journalism changes along with history. Journalism aids in the democratic process by reporting political and societal events. Through reporting, citizens understand current campaign happenings, debate results, and voting activities. In doing so, they also hold the government accountable.

Journalists also force citizens and the government alike to address public interest issues that the society would otherwise not see. Such issues become detrimental to freedom and democracy when we fail to address them. Thus, the media helps society to evolve and balance itself. At the local level, it creates public forums, disseminates information to citizens, and acts as a conduit of sorts for processes that healthy societies need to thrive.

All this works together to create tolerances that, in turn, foster cultural diversity. By keeping the people informed, journalism keeps people united and aligned.

WHERE Do We See the Cultural Impact of Journalism?

Aside from gathering and reporting information, Journalism impacts culture because it interacts with the arts and other disciplines. Whatever art, literature, music, or other cultural event is happening, media brings it to the people’s attention. Through event calendars, reviews, editorials, and so on, people are aware of performances, rituals, and creative offerings that would otherwise go unnoticed. This is how journalism contributes to the culture, adding to the greater good.

WHEN Did the Definition of Journalism Change?

The values and ideology within the field of Journalism adapt to cultural and technological change. After all, you now know that Journalism is far more than just obtaining and delivering news. American society grows more multicultural and diverse each year, let alone each decade. Also, the explosion of multimedia has challenged the very definition of Journalism.

The Twentieth Century changed more than just the delivery platforms for distributing the news. Through radio and television news, journalists could report the news instantly. No longer did we have to wait for the morning headlines. Listeners and viewers could tune into scheduled broadcasts. Emerging news stories were reported through emergency broadcasts.

Journalism and Social Media

With the advent of the Internet came the rise of social media. Legitimate as well as non-credible (“ yellow journalism ” and fake news) stories could be instantaneously shared with millions of people across social networks. Because like-minded people tend to post images and stories of their related interests, bias is created.

Also, the established integrity that journalists and investigative reporters embrace is called into question as more and more online sites and publications pop up without established credibility. Many feel that multimedia platforms are chiseling away at the traditional expectation that a professional journalist meticulously checks all the facts before publishing. On the other hand, the race to break a story first puts incredible pressure on reporters. Being the first to deliver is itself another form of credibility that, ironically, threatens the integrity of the profession.

One can post a fake news story with relative ease, and this poses a threat to the profession. Some go as far as to say that it threatens a free press and democracy itself.

What do you think? Where does Facebook and Twitter fit into your understanding of Journalism? Share your opinion in the comments!

WHY Consider a Career in Journalism?

Journalism is a challenging career, to say the least. However, it’s also a career that carries a great deal of personal integrity and professional identity. If you’re naturally inquisitive, or a storyteller by nature, you’re primed for a career as a reporter.

Successful reporters find themselves sent to places unknown. Depending on your specialty, you may even travel to unstable places. Or, you may be sent on an assignment with little notice. If all this seems exciting rather than upsetting, then Journalism may indeed be for you.

Journalists spend the majority of their time talking with people. If you’re good at interviewing and establishing the rapport needed to get answers, then you have a skill worth developing. Gathering sources and other information means you’ll be moving throughout the day. So, if your ideal job is NOT in a cubicle for 8.5 hours a day, remember that a journalist’s desk is almost always unoccupied.

Journalism requires you to be passionate about your work. It’s demanding but rewarding when you think about the integrity you’re pouring into every word of every article.

HOW Do I Become a Journalist?

Aside from the characteristics we discussed in the previous section, you do need a few other things to become a journalist. First, you need writing experience, even if it’s just practice. You’ll also need a bachelor’s degree from an accredited college or university.

Once you are in the field, understand that most of the work falls under contracting and freelance. If you’re willing to move to a media hub like New York City, Atlanta, or Washington DC, you’re more likely to find a salaried position. A word of warning, however, reporter jobs for print publications are shrinking in number.

You might also like

Jeff Derderian Covers The New Warning Systems Being Installed to Curb Connecticut’s Wrong-Way Driving Incidents

Which Story is Right? How To Know Where to Find News You Can Trust

Shopping with a conscience.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The profession

Present-day journalism.

- What was James Joyce’s family like?

- Why is Jonathan Swift an important writer?

- What was Jonathan Swift’s family like when he was growing up?

- What is Jonathan Swift best known for?

- How did Karl Marx die?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- American Press Institute - Journalism Essentials

- Saskatchewan Polytechnic Pressbooks - Disinformation: Dealing with the Disaster - Journalism and Editing

- Social Sciences LibreTexts - Types of Journalism

- journalism - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Recent News

journalism , the collection, preparation, and distribution of news and related commentary and feature materials through such print and electronic media as newspapers , magazines , books , blogs , webcasts, podcasts, social networking and social media sites, and e-mail as well as through radio , motion pictures , and television . The word journalism was originally applied to the reportage of current events in printed form, specifically newspapers, but with the advent of radio, television, and the Internet in the 20th century the use of the term broadened to include all printed and electronic communication dealing with current affairs.

The earliest known journalistic product was a news sheet circulated in ancient Rome: the Acta Diurna , said to date from before 59 bce . The Acta Diurna recorded important daily events such as public speeches. It was published daily and hung in prominent places. In China during the Tang dynasty , a court circular called a bao , or “report,” was issued to government officials. This gazette appeared in various forms and under various names more or less continually to the end of the Qing dynasty in 1911. The first regularly published newspapers appeared in German cities and in Antwerp about 1609. The first English newspaper, the Weekly Newes , was published in 1622. One of the first daily newspapers, The Daily Courant , appeared in 1702.

At first hindered by government-imposed censorship , taxes, and other restrictions, newspapers in the 18th century came to enjoy the reportorial freedom and indispensable function that they have retained to the present day. The growing demand for newspapers owing to the spread of literacy and the introduction of steam- and then electric-driven presses caused the daily circulation of newspapers to rise from the thousands to the hundreds of thousands and eventually to the millions.

Magazines , which had started in the 17th century as learned journals, began to feature opinion-forming articles on current affairs, such as those in the Tatler (1709–11) and the Spectator (1711–12). Appearing in the 1830s were cheap mass-circulation magazines aimed at a wider and less well-educated public, as well as illustrated and women’s magazines. The cost of large-scale news gathering led to the formation of news agencies , organizations that sold their international journalistic reporting to many different individual newspapers and magazines. The invention of the telegraph and then radio and television brought about a great increase in the speed and timeliness of journalistic activity and, at the same time, provided massive new outlets and audiences for their electronically distributed products. In the late 20th century, satellites and later the Internet were used for the long-distance transmission of journalistic information.

Journalism in the 20th century was marked by a growing sense of professionalism . There were four important factors in this trend: (1) the increasing organization of working journalists, (2) specialized education for journalism, (3) a growing literature dealing with the history , problems, and techniques of mass communication , and (4) an increasing sense of social responsibility on the part of journalists.

An organization of journalists began as early as 1883, with the foundation of England’s chartered Institute of Journalists. Like the American Newspaper Guild, organized in 1933, and the Fédération Nationale de la Presse Française, the institute functioned as both a trade union and a professional organization.

Before the latter part of the 19th century, most journalists learned their craft as apprentices, beginning as copyboys or cub reporters. The first university course in journalism was given at the University of Missouri (Columbia) in 1879–84. In 1912 Columbia University in New York City established the first graduate program in journalism, endowed by a grant from the New York City editor and publisher Joseph Pulitzer . It was recognized that the growing complexity of news reporting and newspaper operation required a great deal of specialized training. Editors also found that in-depth reporting of special types of news, such as political affairs, business, economics , and science , often demanded reporters with education in these areas. The advent of motion pictures, radio, and television as news media called for an ever-increasing battery of new skills and techniques in gathering and presenting the news. By the 1950s, courses in journalism or communications were commonly offered in colleges.

The literature of the subject—which in 1900 was limited to two textbooks, a few collections of lectures and essays, and a small number of histories and biographies—became copious and varied by the late 20th century. It ranged from histories of journalism to texts for reporters and photographers and books of conviction and debate by journalists on journalistic capabilities, methods, and ethics .

Concern for social responsibility in journalism was largely a product of the late 19th and 20th centuries. The earliest newspapers and journals were generally violently partisan in politics and considered that the fulfillment of their social responsibility lay in proselytizing their own party’s position and denouncing that of the opposition. As the reading public grew, however, the newspapers grew in size and wealth and became increasingly independent. Newspapers began to mount their own popular and sensational “crusades” in order to increase their circulation. The culmination of this trend was the competition between two New York City papers, the World and the Journal , in the 1890s ( see yellow journalism ).

The sense of social responsibility made notable growth as a result of specialized education and widespread discussion of press responsibilities in books and periodicals and at the meetings of the associations. Such reports as that of the Royal Commission on the Press (1949) in Great Britain and the less extensive A Free and Responsible Press (1947) by an unofficial Commission on the Freedom of the Press in the United States did much to stimulate self-examination on the part of practicing journalists.

By the late 20th century, studies showed that journalists as a group were generally idealistic about their role in bringing the facts to the public in an impartial manner. Various societies of journalists issued statements of ethics, of which that of the American Society of Newspaper Editors is perhaps best known.

Although the core of journalism has always been the news, the latter word has acquired so many secondary meanings that the term “ hard news ” gained currency to distinguish items of definite news value from others of marginal significance. This was largely a consequence of the advent of radio and television reporting, which brought news bulletins to the public with a speed that the press could not hope to match. To hold their audience, newspapers provided increasing quantities of interpretive material—articles on the background of the news, personality sketches, and columns of timely comment by writers skilled in presenting opinion in readable form. By the mid-1960s most newspapers, particularly evening and Sunday editions, were relying heavily on magazine techniques, except for their content of “hard news,” where the traditional rule of objectivity still applied. Newsmagazines in much of their reporting were blending news with editorial comment.

Journalism in book form has a short but vivid history. The proliferation of paperback books during the decades after World War II gave impetus to the journalistic book, exemplified by works reporting and analyzing election campaigns, political scandals, and world affairs in general, and the “new journalism” of such authors as Truman Capote , Tom Wolfe , and Norman Mailer .

The 20th century saw a renewal of the strictures and limitations imposed upon the press by governments. In countries with communist governments, the press was owned by the state, and journalists and editors were government employees. Under such a system, the prime function of the press to report the news was combined with the duty to uphold and support the national ideology and the declared goals of the state. This led to a situation in which the positive achievements of communist states were stressed by the media, while their failings were underreported or ignored. This rigorous censorship pervaded journalism in communist countries.

In noncommunist developing countries , the press enjoyed varying degrees of freedom, ranging from the discreet and occasional use of self-censorship on matters embarrassing to the home government to a strict and omnipresent censorship akin to that of communist countries. The press enjoyed the maximum amount of freedom in most English-speaking countries and in the countries of western Europe.

Whereas traditional journalism originated during a time when information was scarce and thus highly in demand, 21st-century journalism faced an information-saturated market in which news had been, to some degree , devalued by its overabundance. Advances such as satellite and digital technology and the Internet made information more plentiful and accessible and thereby stiffened journalistic competition. To meet increasing consumer demand for up-to-the-minute and highly detailed reporting, media outlets developed alternative channels of dissemination, such as online distribution, electronic mailings, and direct interaction with the public via forums, blogs, user-generated content, and social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter .

In the second decade of the 21st century, social media platforms in particular facilitated the spread of politically oriented “fake news,” a kind of disinformation produced by for-profit Web sites posing as legitimate news organizations and designed to attract (and mislead) certain readers by exploiting entrenched partisan biases. During the campaign for the U.S. presidential election of 2016 and after his election as president in that year, Donald J. Trump regularly used the term “fake news” to disparage news reports, including by established and reputable media organizations, that contained negative information about him.

Lesson Plan November 17, 2017

The Paradise Papers: A Lesson in Investigative Journalism

Printable PDFs/Word Documents for this Lesson:

- Full lesson for students [PDF] [Word]

- Project Description for the Paradise Papers [PDF]

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

- Describe the process, identify the purpose, and evaluate the impact of investigative journalism

- Evaluate the use of different types of media in acheiving particular aims

- Create a resource that clearly and engagingly conveys information about the Paradise Papers

BREAKING NEWS! On your desk, you will find an envelope with a number written on it and a note card inside. On that note card, there is a tip —a piece of news about your school, neighborhood, or community that someone powerful doesn't want you to know. Your source (the person who left the envelope for you) has chosen to remain anonymous, meaning you don't know who they are. Your source's information might be true or untrue.

1. Brainstorm on your own:

- What steps could you take to determine whether this information is true and what the fuller story behind it is?

- What would be the benefits and drawbacks of keeping this information secret while you investigated it further?

- If you shared this information, who would be affected and how?

2. Find a partner who has an envelope with the same number as your own. Take 3 minutes to merge the steps you brainstormed into a single action plan, and discuss how you can most effectively work together. Then, take another two minutes to discuss what you will do with the information once you have thoroughly investigated it.

3. Discuss as a class:

- What advantages and disadvantages can you see to working with a partner on your investigation?

A few students should share their tip, plan for investigation, and plan for distributing information. The class can then discuss the potential impact of that story.

Introducing the Lesson:

UNESCO defines investigative journalism as "the unveiling of matters that are concealed either deliberately by someone in a position of power, or accidentally, behind a chaotic mass of facts and circumstances - and the analysis and exposure of all relevant facts to the public."

Investigative reporting projects can begin in many ways. Sometimes, a journalist notices a problem or something suspicious themselves and decides to research it some more. Other times, they receive a tip from a source and work to determine whether it is true and what the full story is. In still other cases, a source might provide a leak (send secret information), supplying all the necessary documentation, but requiring the journalist to piece together a narrative from the information and find a way to present it to the public.

- Are you familiar with any investigative journalism stories?

- What do you think is the difference between investigative journalism and other types of journalism?

Today, we are going to learn more about investigative journalists and their work by examining the Paradise Papers, a project from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). This project exposes how political leaders, businesspeople, and the wealthy elite around the world use offshore entities to avoid taxes and cover up wrongdoing. With about 400 journalists working on 6 continents and in 30 languages to examine 13.4 million files for nearly an entire year, it is one of the largest investigative journalism projects in history.

Following this lesson, you will create a resource to clearly and engagingly convey information you have learned from the Paradise Papers to a lay audience, a vital part of investigative journalism.

Introducing Resource 1: " The True Story Behind the Secret Nine-Month Paradise Papers Investigation "

1. After watching the video, work individually or with a partner to create a short summary of what the Paradise Papers are and why they matter.

2. In the video, ICIJ Deputy Director Marina Walker says, "At ICIJ, the mission is to uncover those urgent stories of public interest that go beyond what any particular journalist or media organization can accomplish on his or her own." Consider:

- What is the ICIJ? How does it differ from other news outlets/organizations you are familiar with?

- How would you define a "story of public interest"?

- Why does the ICIJ work with journalists based all over the world?

3. This video introduces many reporters and shows them doing the behind-the-scenes work of investigative journalism. Discuss as a class:

- How would you describe the day-to-day work of an investigative journalist, based on what the video showed? What are their workplaces like? Did anything surprise you?

- What skills do you think are essential for an investigative journalist to have, and why?

- How does the job differ for journalists in different countries?

- What are some of the dangers of investigative journalism, and how do journalists cope with them?

- Investigative journalist Will Fitzgibbon mentions ICIJ's emphasis on releasing all information simultaneously as a team. What are some of the advantages and disadvantages to reporting this way?

Introducing Resource 2: Paradise Papers

1. Read the project description of the Paradise Papers on the Pulitzer Center website. Discuss: how do the summary and statement of import you wrote with your partner compare?

2. Next, explore the interactive within the project, " Paradise Papers: The Influencers ."

- What is your initial reaction to the interactive? How does it make you feel?

- Click through to read the stories about Wilbur Ross. What sections are included in the story, and what purpose do they serve? Do you find the information convincing? Easy to understand? Interesting?

- Take a look at one of the supporting documents . What is your initial reaction? How does it make you feel?

- What do you think the purpose of this interactive is? How effective is it in serving this purpose?

Activity and Discussion:

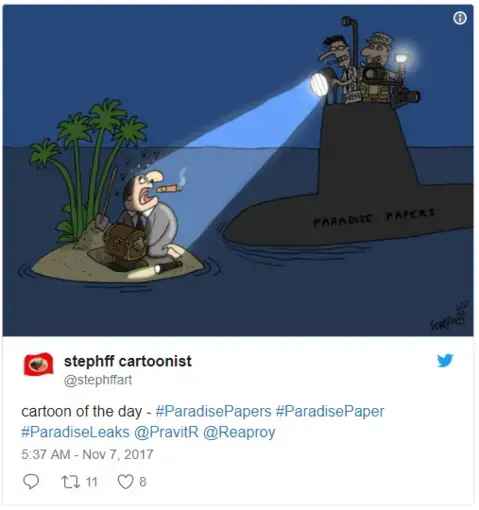

1. Summarize each of the following political cartoons in your own words:

It's unlikely that any private citizen is going to sit down and read 13.4 million files, no matter how significant their value. As such, it is the job of the investigative reporters involved to mine that data for digestible, engaging stories that the public needs and wants to hear.

2. Explore the Paradise Papers investigation on the Pulitzer Center and ICIJ websites. Make a list of the different ways the ICIJ has found to tell this story.

3. In small groups, compare your lists. Consider:

- For each item on your list, who do you think the target audience is?

- What do you think are the most effective ways in which the stories of the Paradise Papers have been told thus far?

- Can you identify any audience(s) these stories are unlikely to reach as a result of the ways it is currently being told?

- What additional ways would it be possible to tell these stories?

- What impacts have the Paradise Papers had already, and what further impact can you foresee?

4. Each group should share their main takeaway(s) from their conversation with the class.

Extension Activity:

1. Building on your final discussion, identify a target audience that you think should know about the Paradise Papers investigation. Create a resource that summarizes the following in a way that will resonate with your target audience:

- What are the Paradise Papers?

- Why are they important?

- How did journalists investigate the story?

You can create a video, infographic, lesson plan, or any other resource. You may alternatively plan a large-scale resource (for example, a museum installation or a play) that you describe in detail but do not execute.

2. Present your resource to the class. Following your presentation, discuss the strengths, weaknesses, and possible impact of such a resource.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.7

Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.2

Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.

Examples of tips you can write in students’ envelopes include:

- The company that supplies your school cafeteria with vegetables has continued selling spinach that might be contaminated with E. coli bacteria despite a recent recall.

- The recycling at the biggest company in your town does not actually get recycled at all; instead, the company sends it off to the landfill while claiming state tax benefits on the recycling equipment and process costs they don’t, in reality, have.

- Maintenance staff at your school is being paid less than minimum wage.

Ensure that students know these are hypothetical examples and not real tips.

To better understand the purpose/impact of this type of reporting and to contextualize the Paradise Papers, it may be useful for students to have some background in U.S. investigative journalism history. To assign as homework or review as a class, this list of noteworthy moments for investigative reporting in the U.S. from the Brookings Institution is one starting place.

Introducing Resource 1: “The True Story Behind the Secret Nine-Month Paradise Papers Investigation”

Depending on time constraints, students can be assigned to watch this video before class, or an excerpt (i.e. 0:00-12:50) can be screened.

Please help us understand your needs better by filling out this brief survey!

REPORTING FEATURED IN THIS LESSON PLAN

Snax Haven – How to Hide the Secret Sauce Recipe and Save Millions

Paradise Papers

ICIJ's global investigation that reveals the offshore activities of some of the world’s most...

Paradise Papers: The Influencers

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Basic newswriting: Learn how to originate, research and write breaking-news stories

Syllabus for semester-long course on the fundamentals of covering and writing the news, including how identify a story, gather information efficiently and place it in a meaningful context.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by The Journalist's Resource, The Journalist's Resource January 22, 2010

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/home/syllabus-covering-the-news/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

This course introduces tomorrow’s journalists to the fundamentals of covering and writing news. Mastering these skills is no simple task. In an Internet age of instantaneous access, demand for high-quality accounts of fast-breaking news has never been greater. Nor has the temptation to cut corners and deliver something less.

To resist this temptation, reporters must acquire skills to identify a story and its essential elements, gather information efficiently, place it in a meaningful context, and write concise and compelling accounts, sometimes at breathtaking speed. The readings, discussions, exercises and assignments of this course are designed to help students acquire such skills and understand how to exercise them wisely.

Photo: Memorial to four slain Lakewood, Wash., police officers. The Seattle Times earned the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Reporting for their coverage of the crime.

Course objective

To give students the background and skills needed to originate, research, focus and craft clear, compelling and contextual accounts of breaking news in a deadline environment.

Learning objectives

- Build an understanding of the role news plays in American democracy.

- Discuss basic journalistic principles such as accuracy, integrity and fairness.

- Evaluate how practices such as rooting and stereotyping can undermine them.

- Analyze what kinds of information make news and why.

- Evaluate the elements of news by deconstructing award-winning stories.

- Evaluate the sources and resources from which news content is drawn.

- Analyze how information is attributed, quoted and paraphrased in news.

- Gain competence in focusing a story’s dominant theme in a single sentence.

- Introduce the structure, style and language of basic news writing.

- Gain competence in building basic news stories, from lead through their close.

- Gain confidence and competence in writing under deadline pressure.

- Practice how to identify, background and contact appropriate sources.

- Discuss and apply the skills needed to interview effectively.

- Analyze data and how it is used and abused in news coverage.

- Review basic math skills needed to evaluate and use statistics in news.

- Report and write basic stories about news events on deadline.

Suggested reading

- A standard textbook of the instructor’s choosing.

- America ‘s Best Newspaper Writing , Roy Peter Clark and Christopher Scanlan, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2006

- The Elements of Journalism , Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, Three Rivers Press, 2001.

- Talk Straight, Listen Carefully: The Art of Interviewing , M.L. Stein and Susan E. Paterno, Iowa State University Press, 2001

- Math Tools for Journalists , Kathleen Woodruff Wickham, Marion Street Press, Inc., 2002

- On Writing Well: 30th Anniversary Edition , William Zinsser, Collins, 2006

- Associated Press Stylebook 2009 , Associated Press, Basic Books, 2009

Weekly schedule and exercises (13-week course)

We encourage faculty to assign students to read on their own Kovach and Rosentiel’s The Elements of Journalism in its entirety during the early phase of the course. Only a few chapters of their book are explicitly assigned for the class sessions listed below.

The assumption for this syllabus is that the class meets twice weekly.

Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 Week 8 | Week 9 | Week 10 | Week 11 | Week 12 | Weeks 13/14

Week 1: Why journalism matters

Previous week | Next week | Back to top

Class 1: The role of journalism in society

The word journalism elicits considerable confusion in contemporary American society. Citizens often confuse the role of reporting with that of advocacy. They mistake those who promote opinions or push their personal agendas on cable news or in the blogosphere for those who report. But reporters play a different role: that of gatherer of evidence, unbiased and unvarnished, placed in a context of past events that gives current events weight beyond the ways opinion leaders or propagandists might misinterpret or exploit them.

This session’s discussion will focus on the traditional role of journalism eloquently summarized by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel in The Elements of Journalism . The class will then examine whether they believe that the journalist’s role has changed or needs to change in today’s news environment. What is the reporter’s role in contemporary society? Is objectivity, sometimes called fairness, an antiquated concept or an essential one, as the authors argue, for maintaining a democratic society? How has the term been subverted? What are the reporter’s fundamental responsibilities? This discussion will touch on such fundamental issues as journalists’ obligation to the truth, their loyalty to the citizens who are their audience and the demands of their discipline to verify information, act independently, provide a forum for public discourse and seek not only competing viewpoints but carefully vetted facts that help establish which viewpoints are grounded in evidence.

Reading: Kovach and Rosenstiel, Chapter 1, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignments:

- Students should compare the news reporting on a breaking political story in The Wall Street Journal , considered editorially conservative, and The New York Times , considered editorially liberal. They should write a two-page memo that considers the following questions: Do the stories emphasize the same information? Does either story appear to slant the news toward a particular perspective? How? Do the stories support the notion of fact-based journalism and unbiased reporting or do they appear to infuse opinion into news? Students should provide specific examples that support their conclusions.

- Students should look for an example of reporting in any medium in which reporters appear have compromised the notion of fairness to intentionally or inadvertently espouse a point of view. What impact did the incorporation of such material have on the story? Did its inclusion have any effect on the reader’s perception of the story?

Class 2: Objectivity, fairness and contemporary confusion about both

In his book Discovering the News , Michael Schudson traced the roots of objectivity to the era following World War I and a desire by journalists to guard against the rapid growth of public relations practitioners intent on spinning the news. Objectivity was, and remains, an ideal, a method for guarding against spin and personal bias by examining all sides of a story and testing claims through a process of evidentiary verification. Practiced well, it attempts to find where something approaching truth lies in a sea of conflicting views. Today, objectivity often is mistaken for tit-for-tat journalism, in which the reporters only responsibility is to give equal weight to the conflicting views of different parties without regard for which, if any, are saying something approximating truth. This definition cedes the journalist’s responsibility to seek and verify evidence that informs the citizenry.

Focusing on the “Journalism of Verification” chapter in The Elements of Journalism , this class will review the evolution and transformation of concepts of objectivity and fairness and, using the homework assignment, consider how objectivity is being practiced and sometimes skewed in the contemporary new media.

Reading: Kovach and Rosenstiel, Chapter 4, and relevant pages of the course text.

Assignment: Students should evaluate stories on the front page and metro front of their daily newspaper. In a two-page memo, they should describe what elements of news judgment made the stories worthy of significant coverage and play. Finally, they should analyze whether, based on what else is in the paper, they believe the editors reached the right decision.

Week 2: Where news comes from

Class 1: News judgment

When editors sit down together to choose the top stories, they use experience and intuition. The beginner journalist, however, can acquire a sense of news judgment by evaluating news decisions through the filter of a variety of factors that influence news play. These factors range from traditional measures such as when the story took place and how close it was to the local readership area to more contemporary ones, such as the story’s educational value.

Using the assignment and the reading, students should evaluate what kinds of information make for interesting news stories and why.

In this session, instructors might consider discussing the layers of news from the simplest breaking news event to the purely enterprise investigative story.

Assignment: Students should read and deconstruct coverage of a major news event. One excellent source for quality examples is the site of the Pulitzer Prizes , which has a category for breaking news reporting. All students should read the same article (assigned by the instructor), and write a two- or three-page memo that describes how the story is organized, what information it contains and what sources of information it uses, both human and digital. Among the questions they should ask are:

- Does the first (or lead) paragraph summarize the dominant point?

- What specific information does the lead include?

- What does it leave out?

- How do the second and third paragraphs relate to the first paragraph and the information it contains? Do they give unrelated information, information that provides further details about what’s established in the lead paragraph or both?

- Does the story at any time place the news into a broader context of similar events or past events? If so, when and how?

- What information in the story is attributed , specifically tied to an individual or to documentary information from which it was taken? What information is not attributed? Where does the information appear in the sentence? Give examples of some of the ways the sources of information are identified? Give examples of the verbs of attribution that are chosen.

- Where and how often in the story are people quoted, their exact words placed in quotation marks? What kind of information tends to be quoted — basic facts or more colorful commentary? What information that’s attributed is paraphrased , summing up what someone said but not in their exact words.

- How is the story organized — by theme, by geography, by chronology (time) or by some other means?

- What human sources are used in the story? Are some authorities? Are some experts? Are some ordinary people affected by the event? Who are some of the people in each category? What do they contribute to the story? Does the reporter (or reporters) rely on a single source or a wide range? Why do you think that’s the case?

- What specific facts and details make the story more vivid to you? How do you think the reporter was able to gather those details?

- What documents (paper or digital) are detailed in the story? Do they lend authority to the story? Why or why not?

- Is any specific data (numbers, statistics) used in the story? What does it lend to the story? Would you be satisfied substituting words such as “many” or “few” for the specific numbers and statistics used? Why or why not?

Class 2: Deconstructing the story

By carefully deconstructing major news stories, students will begin to internalize some of the major principles of this course, from crafting and supporting the lead of a story to spreading a wide and authoritative net for information. This class will focus on the lessons of a Pulitzer Prize winner.

Reading: Clark/Scanlan, Pages 287-294

Assignment: Writers typically draft a focus statement after conceiving an idea and conducting preliminary research or reporting. This focus statement helps to set the direction of reporting and writing. Sometimes reporting dictates a change of direction. But the statement itself keeps the reporter from getting off course. Focus statements typically are 50 words or less and summarize the story’s central point. They work best when driven by a strong, active verb and written after preliminary reporting.

- Students should write a focus statement that encapsulates the news of the Pulitzer Prize winning reporting the class critiqued.

Week 3: Finding the focus, building the lead

Class 1: News writing as a process

Student reporters often conceive of writing as something that begins only after all their reporting is finished. Such an approach often leaves gaps in information and leads the reporter to search broadly instead of with targeted depth. The best reporters begin thinking about story the minute they get an assignment. The approach they envision for telling the story informs their choice of whom they seek interviews with and what information they gather. This class will introduce students to writing as a process that begins with story concept and continues through initial research, focus, reporting, organizing and outlining, drafting and revising.

During this session, the class will review the focus statements written for homework in small breakout groups and then as a class. Professors are encouraged to draft and hand out a mock or real press release or hold a mock press conference from which students can draft a focus statement.

Reading: Zinsser, pages 1-45, Clark/Scanlan, pages 294-302, and relevant pages of the course text

Class 2: The language of news

Newswriting has its own sentence structure and syntax. Most sentences branch rightward, following a pattern of subject/active verb/object. Reporters choose simple, familiar words. They write spare, concise sentences. They try to make a single point in each. But journalistic writing is specific and concrete. While reporters generally avoid formal or fancy word choices and complex sentence structures, they do not write in generalities. They convey information. Each sentence builds on what came before. This class will center on the language of news, evaluating the language in selections from America’s Best Newspaper Writing , local newspapers or the Pulitzers.

Reading: Relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Students should choose a traditional news lead they like and one they do not like from a local or national newspaper. In a one- or two-page memo, they should print the leads, summarize the stories and evaluate why they believe the leads were effective or not.

Week 4: Crafting the first sentence

Class 1: The lead

No sentence counts more than a story’s first sentence. In most direct news stories, it stands alone as the story’s lead. It must summarize the news, establish the storyline, convey specific information and do all this simply and succinctly. Readers confused or bored by the lead read no further. It takes practice to craft clear, concise and conversational leads. This week will be devoted to that practice.

Students should discuss the assigned leads in groups of three or four, with each group choosing one lead to read to the entire class. The class should then discuss the elements of effective leads (active voice; active verb; single, dominant theme; simple sentences) and write leads in practice exercises.

Assignment: Have students revise the leads they wrote in class and craft a second lead from fact patterns.

Class 2: The lead continued

Some leads snap or entice instead of summarize. When the news is neither urgent nor earnest, these can work well. Though this class will introduce students to other kinds of leads, instructors should continue to emphasize traditional leads, typically found atop breaking news stories.

Class time should largely be devoted to writing traditional news leads under a 15-minute deadline pressure. Students should then be encouraged to read their own leads aloud and critique classmates’ leads. At least one such exercise might focus on students writing a traditional lead and a less traditional lead from the same information.

Assignment: Students should find a political or international story that includes various types (direct and indirect) and levels (on-the-record, not for attribution and deep background) of attribution. They should write a one- or two-page memo describing and evaluating the attribution. Did the reporter make clear the affiliation of those who expressed opinions? Is information attributed to specific people by name? Are anonymous figures given the opportunity to criticize others by name? Is that fair?

Week 5: Establishing the credibility of news

Class 1: Attribution