- How to Write an Effective Conference Summary: A Comprehensive Guide

- Not classified

How to Write an Effective Conference Summary

Writing a conference report is not just about putting words on paper; it’s about distilling the essence of an event to engage and inform your audience. To craft a compelling conference summary, start by asking yourself crucial questions: What is the purpose of the summary? Who is the target audience? Is it a brief one-hour keynote or an extensive 5-day conference with multiple parallel sessions? Tailoring your approach to these considerations ensures that your summary serves its intended purpose.

I still remember about 20 years ago. I had just started my first job at the Idiap research institute after my studies. I discovered that young researchers who had worked hard on their thesis would go and present their work at international scientific conferences and come back with a 5-line report: “I liked the presentation of this paper, this one and this one again”. And that was it. I thought there had to be another way, in addition to the “proceedings” containing all the peer-reviewed articles, to keep track of these events. And so, in 2007, the Klewel company was born. But now let’s get back to the topic of this post: How to Write an Effective Conference Summary.

Setting the Stage: The 5 Ws and QQOQCP

Begin by covering the basics using the 5 Ws method (Who, What, Where, When, Why), with the addition of ‘How’ and sometimes ‘How much’ (represented by the acronym QQOQCP). These questions provide a framework for presenting essential information and setting the scene for your readers.

For instance, if you’re summarizing a one-day conference with approximately 10 speakers, consider incorporating the key details using the 5 Ws and QQOQCP to create a well-rounded overview.

Record and Repeat: Maximizing Conference Content

If possible, record the conference to facilitate accurate note-taking and ensure that every nuance is captured. This practice is particularly valuable for events featuring multiple speakers, as it allows you to revisit and accurately represent each presentation.

While attending the conference, take diligent notes. Utilize effective techniques such as transcribing directly onto your computer. Conference reporting demands technical proficiency, and we’ll provide you with some helpful pointers to navigate this process.

Structuring Your Report

Simplify the process by replicating the program structure in your summary. If the conference offers video content, leverage it by referring to on-demand videos for each presentation. This not only streamlines the summary but also directs readers to additional resources.

Uncover Key Insights: Interviews and Participant Feedback

Tap into the wealth of knowledge possessed by conference organizers. Conduct interviews to glean insights into influential speakers, emerging concepts, and trends within the field. This journalist-like approach enriches your summary by providing a comprehensive understanding of the event.

Engage with participants and speakers to identify key points and new features. Encourage them to share their perspectives on the most impactful aspects of the conference. A journalist’s knack for asking insightful questions can reveal the pulse of the field.

Innovative Formats: Moving Beyond Standard Text

Consider experimenting with various formats for your conference summary. While the traditional text document is effective, explore innovative options like after-movies. A well-crafted after-movie captures the event’s atmosphere, offering a visual and emotive experience that text alone cannot convey.

Some conferences enlist professional illustrators to create visual summaries in the form of drawings. While this may seem unconventional, coupling illustrations with concise text provides a panoramic view of the event without delving into the specifics of each presentation.

The Takeaway: Share the Essence

Ultimately, the goal is to distill the most crucial points into a “Take home” message. By sharing these key insights, your conference summary becomes a valuable resource that not only informs but also inspires new participants to engage with future events.

In summary, writing an effective conference summary requires a strategic approach, incorporating thoughtful questions, comprehensive coverage, and innovative presentation formats. By mastering these elements, you can create summaries that resonate with your audience and elevate the impact of the conferences you cover.

Ready to Elevate Your Conference Experience?

Writing a compelling conference summary is just the beginning of what we do at Klewel. If you’re looking to capture, broadcast, and share the essence of your conferences seamlessly, we’re here to help. Contact us at Klewel to explore how our cutting-edge services can transform your events into lasting experiences. Whether you need professional recording, innovative after-movies, or engaging visual summaries, our team is ready to enhance your conference journey. Let’s make your next event unforgettable together. Reach out to us today !

Related posts

How to Make Your Next Conference Unforgettable?

Unlocking the Power of On-Demand Videos in the Conference Arena

What is the difference between a webcast and a webinar?

Making a short presentation based on your research: 11 tips

Markus goldstein, david evans.

Over the past few weeks, we’ve both spent a fair amount of time at conferences. Given that many conferences ask researchers to summarize their work in 15 to 20 minutes, we thought we’d reflect on some ideas for how to do this, and – more importantly – how to do it well.

- You have 15 minutes. That’s not enough time to use the slides you used for that recent 90-minute academic seminar. One recent presentation one of us saw had 52 slides for 15 minutes. No amount of speed talking will get you through this in anything resembling coherence. (And quit speed talking, anyway. This isn’t a FedEx commercial !) There is no magic number of slides since the content you’ll have and how you talk will vary. But if you have more than 15 slides, then #2 is doubly important.

- Practice. This is the great thing about a 15-minute talk: You can actually afford to run through it, out loud. Running through it once in advance can reveal to you – wow! – that it’s actually a 25-minute talk and you need to cut a bunch. Of course, the first time through the presentation it may take a bit longer than you will when you present, but if you have any doubts, practice again (bringing your prep time to a whopping 30 minutes plus a little bit).

- You need a (short) narrative. What is the main story you are trying to tell with this paper? Fifteen minutes works better for communicating a narrative then for taking an audience through every twist and turn of your econometric grandeur. Deciding on your narrative will help with the discipline in the points that follow.

- A model or results? Even if your audience is all academics, you don’t have academic seminar time. So the first thing to do is to figure out which is more important to get across – your model or your empirical results. Then trim the other one down to one slide, max. If the results are your focus (usually the case for us), give the audience a sense of how the model is set up, and what the main implications are as they pertain to the results you will show. Conversely, if it’s the model that’s more important, the empirical results will come later and you can just give the very brief highlights that bolster the key points.

- The literature. Really, really minimal. If you do it at all, choose only the papers that you are either going to build on in a major way or contradict. For some types of discussants, it may help to include them, even if they don’t meet the other criteria. Marc Bellemare takes an even stronger stance: “Never, ever have a literature review in your slides. If literature reviews are boring to read in papers, they are insanely boring to listen to during presentations.”

- Program details. Here it’s a bit of a balance. The audience needs a flavor for the program, they need to understand what it did and how it’s different from other things (particularly other things with some kinds of evidence). But only in exceptional cases (as in, it’s a really different program for theoretical reasons, or you don’t have more than process results yet) do you want this to eat up a lot of your time.

- You don’t have time to go through the nitty gritty of the data. We get that every detail about the survey was fascinating (we spend a lot of our lives thinking about this). But if it’s not key to the story, save it for a longer presentation (or another paper). And if you’re doing a primarily theoretical paper, this is a bullet on one slide.

- Balance and summary stats. Key summary stats that tell the audience who the people are might make the cut, but 3 slides of every variable that you’ll use are going to be slides you either rip through (telling the audience nothing) or waste most of your time on. Summarize the summary stats. On balance tests: you are either balanced or not. If you are, this gets a bullet at most (you can also just say that). If you’re not, tell us what’s up and why we should or should not worry.

- Pre-analysis plan. If you had it, mention it (quickly). If not, don’t. It’s not critical here.

- A picture may be worth 1,000 numbers. Sometimes, taking that really packed table which is currently in 12 point font and turning it into a graph is going to help you with self-control and help your audience with comprehension. Put the significant results in a bar chart, and use asterisks to tell folks which are significant.

- A special warning about presenting your job market paper. When I (Markus) submitted my job market paper to a journal, the referee report came back noting that this was surely a job market paper since it had 40(!) tables. Key example of how everything matters when you just spent four years of your life collecting each observation. Discipline. You have (or will have) an elevator pitch from the job market – use this to trim your presentation.

- Marc Bellemare has a great series of “22 tips for conference and seminar presentations,” many of which apply to short presentations: “Always provide a preview of your results. This isn’t a murder mystery: it’s only when people know where you’re taking them that they can enjoy the scenery along the way.”

- Jeff Leek has a great guide to giving presentations of different lengths, and what your goal should be: “As a scientist, it is hard to accept that the primary purpose of a talk is advertising, not science.” This is doubly true for a 15-minute talk.

- The AEA Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession has a top 10 list. “Never cut and paste a table from your paper onto a slide. These tables are never easy to read and only irritate your audience. Instead, choose a few results that you want to highlight and present them on a slide in no smaller than 28 font.” We’ve pretty much all done this. It’s bad practice. (“I’m sorry you can’t read this table.” “Oh really, then why did you cut and paste that giant table from your paper into the presentation?!”)

- I (Dave) go back and re-read Jesse Shapiro’s guide on “ How to Give an Applied Micro Talk ” from time to time. It’s more geared toward a full-length seminar, but the advice is so good I can’t resist plugging it here.

Lead Economist, Africa Gender Innovation Lab and Chief Economists Office

Senior Fellow, Center for Global Development

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

- Public Lectures

- Faculty & Staff Site >>

Presenting Your Research at Academic Conferences

Academic conferences allow you to:

- Start developing your research agenda. Get useful feedback on your research as you convert conference papers into journal articles.

- Gain visibility with future colleagues, employers, and future collaborators.

- Start networking and meet people (other graduate students, future colleagues and mentors, researchers you admire).

- Interview for jobs.

Which conferences?

Most UW departments are well-represented at key national academic conferences.

Many professional associations have divisions that may reflect your department’s areas of expertise. Graduate students also find it useful to present their research at topic-specific conferences. Check with faculty to see which organizations hold conferences where it would be appropriate for your research to be presented.

When and how?

Deadlines for conferences are usually noted on academic organizations’ websites. When considering how to submit your research, be sure to check submission requirements. Some conferences require full papers, while others will consider only abstracts. Be sure to adhere to these details and all deadlines, and be sure to submit your work to a relevant division! (What constitutes “relevant?” Check abstracts and programs from previous years’ conferences.)

At the conference…

Some departments provide funds that allow you to travel to conferences to present your research. In addition to talking about your research in a variety of ways, take advantage of being at the conference to learn about the field, meet other people, and participate.

Presenting your research

You will be judged first and foremost on your research, which means that you should strive for a great presentation. In other words:

- Know what attendees at this particular conference expect, e.g., reading your paper vs. summarizing your paper? PowerPoint slides?

- Know your research and what it contributes to the larger body of research.

- Never, ever, exceed the allotted time! Think of your presentation as a headline service. You cannot cover all points, so select the ones you believe are most important.

How to navigate the conference

Read the conference program; attend the sessions that interest you, but don’t plan every hour.

Be ready with a brief “elevator talk” about your research. Conferences are very busy times, and people will not have time to hear a full explication of all your research projects.

Identify the individuals you would like to meet and ask your mentor/adviser to introduce you.

Introduce yourself to people. Many graduate students feel as if they know no one, so you’re not alone. If you are interested in meeting faculty and “big names,” walk up to them when they appear to have a spare moment, and talk about how you are using their research in your own work. Chances are they will want to learn more about you and your work.

Attend graduate forums and receptions.

Socialize at receptions held by various departments and schools.

Regardless of the sessions you attend and the people you meet, always remain professional. You want to be remembered for your research and professional demeanor, not anything else!

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

APSA 2019 roundup: Research on political socialization, campaign spending and misinformation

The annual meeting of the American Political Science Association took place in Washington, D.C., in September, with researchers from around the world showcasing new findings. Below are brief summaries of some of the research presented at the conference (though the meeting covered many other subjects, and our researchers couldn’t attend every panel). Several of these papers relate to past Pew Research Center work on misinformation and survey methodology .

As is true of many academic conferences, some of these results may be preliminary and could be revised, and several of the papers are not yet published in peer-reviewed journals. The full conference program is available here .

Researchers are learning more about early political socialization. Researchers from the University of Notre Dame looked at the formative years of political life using a nationally representative sample of teens ages 15 to 18. They showed that teen girls were particularly energized by the 2018 midterm election, and that, compared with boys, girls’ belief that they can make a difference politically (such as by writing elected officials, protesting or otherwise making their voices heard) improved dramatically.

In another project, a team of political scientists interviewed over 1,000 elementary school-aged children in the U.S. to assess their feelings toward government and political leaders. The researchers found that half of the children they interviewed had some kind of partisan attachment by the time they were 12, and that these children were not shy about expressing negative views about those they disagreed with politically.

TV remains the focus for political advertising spending by political campaigns, but social media is becoming important as well. Researchers presented a deep dive on political advertising during the 2018 election, with a look at political advertising on Facebook and TV in particular. Among their findings: While more political candidates created ads on Facebook than TV during this election, they spent much less to do so on the social media platform. And compared with TV, ads on Facebook were less geared toward persuading a broad audience to vote for a candidate (or against another), especially via policy-oriented appeals, and more toward building support for a candidate through fundraising.

Emerging techniques to fight misinformation are seeing some success. Replies to a tweet containing an erroneous claim about raw milk helped reduce perceptions that such milk is healthy and safe, according to an experimental study conducted on Mechanical Turk by researchers from Georgetown University , the University of Minnesota and the University of Iowa . The researchers found that the tone of the reply didn’t seem to matter: Uncivil corrections (“Oh come on, don’t be stupid. Everyone knows that pasteurizing milk doesn’t affect its nutrients”) were as effective as more civil corrections.

Computational methods reveal “hidden” forms of lawmaking. Several papers highlighted new efforts to use computational methods to track how legislative ideas are recycled and transferred in Congress.

Using computational similarity measures to identify recurring bill sections across 13 Congresses, a team of researchers developed a method to track “unorthodox lawmaking,” in which legislators enact policy by attaching content from their own prior, unsuccessful bills to new legislation – sponsored by other lawmakers – that becomes law. Expanding on existing measures of legislative effectiveness, the authors introduced a new measure (known as LawProM) that accounts for the passage of these “hitchhiker bills,” which they find are more common among female members of Congress.

In another paper , researchers focused more broadly on both successful and failed hitchhiker bills, using a supervised machine learning approach to identify 15,000 such bills across 11 Congresses. The study found that hitchhiker bills are more likely to be enacted into law when they are attached to bills sponsored by a committee chair or a member of the majority party, and when the bill and hitchhiker sponsors have greater ideological differences (which may help broaden a bill’s bipartisan appeal).

Innovative work in survey measurement. Many political scientists work with public opinion data, and several papers highlighted innovation in survey measurement and design. For example, researchers from the University of North Carolina presented an exploratory study about measuring the policy issues that are seen by the public as most important. Rather than asking generally about the most important issues for the country , they asked individuals about a series of issues and whether they, personally, had given a lot of thought to each one. The conclusion: People had distinct issues of personal importance. The findings suggest that public opinion research would benefit from more careful understanding of segments of the population that are intensely interested in particular areas.

Separately, in a thorough examination of who is more likely to respond “don’t know” to survey questions, a researcher from the University of California at San Diego found that women are consistently more likely to do so than men. Using the American National Election Studies archive, the analysis found that this gender gap has decreased over time, but persists. The study also showed that women often will seek more information about an issue prior to offering their opinions, suggesting that part of the gap in “don’t know” responses is accounted for by different information thresholds between men and women.

- Methodological Research

Bradley Jones is a former senior researcher focusing on politics at Pew Research Center .

Galen Stocking is a senior computational social scientist focusing on journalism research at Pew Research Center .

Michael Barthel is a former senior researcher focusing on journalism research at Pew Research Center .

Patrick van Kessel is a former senior data former scientist at Pew Research Center .

Online opt-in polls can produce misleading results, especially for young people and Hispanic adults

Who are you the art and science of measuring identity, q&a: how we used large language models to identify guests on popular podcasts, q&a: how – and why – we’re changing the way we study tech adoption, state of the news media methodology, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Scholarly Publishing

- Introduction

- Choosing Publishers - Considerations and risks

- Making your thesis into a book

- Which conference to attend

Evaluating conferences

Attending conferences, publication counting.

- Conference rankings

Professional sites

Conference directories, conference papers/proceedings.

- When choosing a journal

- Journals selection/ evaluation

- Open Research guide

- UOM Researcher publishing support

- Author Profiles

Which conference to attend?

- Think, Check, Attend

The Think, Check, Attend checklist includes nine questions to ask about organisers and sponsors of conferences, six questions about the agenda of the conferences and the editorial committee, and four more about the conference proceedings.

As a first step, try completing the Conference Checker form.

Ensure that you protect yourself and publish only in reputable and recognised conferences. You may have limited time and budget at your disposal. Therefore always evaluate carefully if the conference you are considering is right for you. Some guiding questions are presented below.

- What is the research field of the conference?

- How frequent do the conference occur?

- Who will be attending the conference? ~ Academics; ~ Administrators; ~Counselors; ~ Educators; ~ Social Scientists; ~ Researchers

- Which conferences do others in your communities of practices attend?

- How many people get together at this conference?

- How likely is it that a paper might get accepted for the conference program?

- How is the conference viewed by your colleagues or peers?

- Are abstracts released as published abstracts?

- Are paper submissions sent out for peer review?

- Will conference papers be published in proceedings afterwards?

- Why are you considering this conference?

Selecting a conference

It is just as important to evaluate which conferences to focus on as it is to evaluate the integrity of journals.

Evaluate conferences - use Think, Check, Attend

Attend conferences as a method of staying current and testing new work . You can also network with colleagues in your research field. Presenting at conferences have the added benefit of personalising your work and providing a face and voice to it. You can use it to test how your work is received and use the feedback received to build your work further before aiming to publish in journals and other forms of academic publishing.

- There are several ways in which articles in conference proceedings may be accredited. Both hinge on peer review.

- Check if conference proceedings gets published and if you will get recognised for your work.

- You might need to submit the completed paper for pre-conference peer review. Some of the papers are then selected for presentation and publication.

- Other conferences invites post-conference submission for peer-review.

- If this is allowed, get your conference paper or poster more visible after the conference by posting links to it on your blog and social media profiles.

Read about the value of conferences

To have a conference publication counted and recognised as an academic research output in Australia, the following definitions are worth noting.

For the purposes of ERA , research is defined as the creation of new knowledge and/or the use of existing knowledge in new and creative ways to generate new concepts, methodologies, inventions and understandings. This could include synthesis of previous research so it produces new and creative outputs.

Publication data collected for the Higher Education Research Data Collection (HERDC) publication component recognises four traditional publication categories: (Eligible publications are defined in the HERDC specifications for the given year)

A1 - Books (as authored research)

B1 - Chapters in Scholarly Books

C1 - Articles in Scholarly Refereed journals

E1 - Conference publication - Full paper - Refereed

Not counted

- book reviews

- letters to the editor

- non-scholarly, non-research articles

- articles in newspapers and popular magazines

- reviews of art exhibitions, concerts and theatre productions; medical case histories or data reports, that are not full journal articles

- commentaries and brief communications of original research that are not subject to peer review

- articles designed to inform practitioners in a professional field, such as a set of guidelines or the state of knowledge in a field)

- papers that appear only in a volume handed out or sold to conference participants (e.g. “Program and Abstracts” books)

- invited papers

- papers presented at minor conferences, workshops or seminars that are not regarded as having national significance

- conference papers assessed only by an editorial board

- conference papers accepted for presentation (and publication) on the basis of peer review of a submitted extract or abstract only

- one page abstracts or summaries of poster presentations )

Core Rankings

The CORE Conference Ranking provides assessments of major conferences in the computing disciplines. The rankings are managed by the CORE Executive Committee, with periodic rounds for submission of requests for addition or reranking of conferences. Decisions are made by academic committees based on objective data requested as part of the submission process.

Conferences are assigned to one of the following categories:

A* - flagship conference (leading venue in a discipline area)

A – excellent conference (highly respected in a discipline area)

B – good conference (well regarded in a discipline area)

C – other ranked conference (venues meet minimum standards)

- Australasian (audience primarily Australians/ New Zealanders)

- Unranked – no ranking decision yet

- National – (runs primarily in a single country, Chairs from that country – not sufficiently known to be ranked)

- Regional – (similar to National – may cover a region)

Rankings are determined by citation rates, acceptance rates, visibility and track record of the hosts, the management of the technical program, etc.

If you follow a particular research community or professional association, these bodies often promote events and conferences to their members.

Some of these bodies are listed below.

- Australian Academy of the Humanities

- The Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Mathematical and Statistical Frontiers (ACEMS)

- Engineers Australia

- Institute of Public Accountants

- Migration Institute of Australia

- School Library Association of Victoria

There are vetted tools to help researchers identify recognised conferences in their respective fields.

Further there are conference portals and -directories created by companies with potential commercial interests in creating the lists and promoting the conferences. Always evaluate information sources used to make strategic decisions carefully.

Directories and databases (Library subscriptions)

Commercial conference directories.

- Web of Science

- << Previous: Making your thesis into a book

- Next: When choosing a journal >>

- Last Updated: May 14, 2024 3:45 PM

- URL: https://unimelb.libguides.com/Scholarly_publishing

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Surveys Academic Research

Research Summary: What is it & how to write one

The Research Summary is used to report facts about a study clearly. You will almost certainly be required to prepare a research summary during your academic research or while on a research project for your organization.

If it is the first time you have to write one, the writing requirements may confuse you. The instructors generally assign someone to write a summary of the research work. Research summaries require the writer to have a thorough understanding of the issue.

This article will discuss the definition of a research summary and how to write one.

What is a research summary?

A research summary is a piece of writing that summarizes your research on a specific topic. Its primary goal is to offer the reader a detailed overview of the study with the key findings. A research summary generally contains the article’s structure in which it is written.

You must know the goal of your analysis before you launch a project. A research overview summarizes the detailed response and highlights particular issues raised in it. Writing it might be somewhat troublesome. To write a good overview, you want to start with a structure in mind. Read on for our guide.

Why is an analysis recap so important?

Your summary or analysis is going to tell readers everything about your research project. This is the critical piece that your stakeholders will read to identify your findings and valuable insights. Having a good and concise research summary that presents facts and comes with no research biases is the critical deliverable of any research project.

We’ve put together a cheat sheet to help you write a good research summary below.

Research Summary Guide

- Why was this research done? – You want to give a clear description of why this research study was done. What hypothesis was being tested?

- Who was surveyed? – The what and why or your research decides who you’re going to interview/survey. Your research summary has a detailed note on who participated in the study and why they were selected.

- What was the methodology? – Talk about the methodology. Did you do face-to-face interviews? Was it a short or long survey or a focus group setting? Your research methodology is key to the results you’re going to get.

- What were the key findings? – This can be the most critical part of the process. What did we find out after testing the hypothesis? This section, like all others, should be just facts, facts facts. You’re not sharing how you feel about the findings. Keep it bias-free.

- Conclusion – What are the conclusions that were drawn from the findings. A good example of a conclusion. Surprisingly, most people interviewed did not watch the lunar eclipse in 2022, which is unexpected given that 100% of those interviewed knew about it before it happened.

- Takeaways and action points – This is where you bring in your suggestion. Given the data you now have from the research, what are the takeaways and action points? If you’re a researcher running this research project for your company, you’ll use this part to shed light on your recommended action plans for the business.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

If you’re doing any research, you will write a summary, which will be the most viewed and more important part of the project. So keep a guideline in mind before you start. Focus on the content first and then worry about the length. Use the cheat sheet/checklist in this article to organize your summary, and that’s all you need to write a great research summary!

But once your summary is ready, where is it stored? Most teams have multiple documents in their google drives, and it’s a nightmare to find projects that were done in the past. Your research data should be democratized and easy to use.

We at QuestionPro launched a research repository for research teams, and our clients love it. All your data is in one place, and everything is searchable, including your research summaries!

Authors: Prachi, Anas

MORE LIKE THIS

Trend Report: Guide for Market Dynamics & Strategic Analysis

May 29, 2024

Cannabis Industry Business Intelligence: Impact on Research

May 28, 2024

Top 10 Dynata Alternatives & Competitors

May 27, 2024

What Are My Employees Really Thinking? The Power of Open-ended Survey Analysis

May 24, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Event Website Publish a modern and mobile friendly event website.

- Registration & Payments Collect registrations & online payments for your event.

- Abstract Management Collect and manage all your abstract submissions.

- Peer Reviews Easily distribute and manage your peer reviews.

- Conference Program Effortlessly build & publish your event program.

- Virtual Poster Sessions Host engaging virtual poster sessions.

- Customer Success Stories

- Wall of Love ❤️

How to Present Your Research (Guidelines and Tips)

Published on 01 Feb 2023

Presenting at a conference can be stressful, but can lead to many opportunities, which is why coming prepared is super beneficial.

The internet is full to the brim with tips for making a good presentation. From what you wear to how you stand to good slide design, there’s no shortage of advice to make any old presentation come to life.

But, not all presentations are created equal. Research presentations, in particular, are unique.

Communicating complex concepts to an audience with a varied range of awareness about your research topic can be tricky. A lack of guidance and preparation can ruin your chance to share important information with a conference community. This could mean lost opportunities in collaboration or funding or lost confidence in yourself and your work.

So, we’ve put together a list of tips with research presentations in mind. Here’s our top to-do’s when preparing to present your research.

Take every research presentation opportunity

The worst thing you could do for your research is to not present it at all. As intimidating as it can be to get up in front of an audience, you shouldn’t let that stop you from seizing a good opportunity to share your work with a wider community.

These contestants from the Vitae Three Minute Thesis Competition have some great advice to share on taking every possible chance to talk about your research.

Double-check your research presentation guidelines

Before you get started on your presentation, double-check if you’ve been given guidelines for it.

If you don’t have specific guidelines for the context of your presentation, we’ve put together a general outline to help you get started. It’s made with the assumption of a 10-15 minute presentation time. So, if you have longer to present, you can always extend important sections or talk longer on certain slides:

- Title Slide (1 slide) - This is a placeholder to give some visual interest and display the topic until your presentation begins.

- Short Introduction (2-3 slides) - This is where you pique the interest of your audience and establish the key questions your presentation covers. Give context to your study with a brief review of the literature (focus on key points, not a full review). If your study relates to any particularly relevant issues, mention it here to increase the audience's interest in the topic.

- Hypothesis (1 slide) - Clearly state your hypothesis.

- Description of Methods (2-3 slides) - Clearly, but briefly, summarize your study design including a clear description of the study population, the sample size and any instruments or manipulations to gather the data.

- Results and Data Interpretation (2-4 slides) - Illustrate your results through simple tables, graphs, and images. Remind the audience of your hypothesis and discuss your interpretation of the data/results.

- Conclusion (2-3 slides) - Further interpret your results. If you had any sources of error or difficulties with your methods, discuss them here and address how they could be (or were) improved. Discuss your findings as part of the bigger picture and connect them to potential further outcomes or areas of study.

- Closing (1 slide) - If anyone supported your research with guidance, awards, or funding, be sure to recognize their contribution. If your presentation includes a Q&A session, open the floor to questions.

Plan for about one minute for each slide of information that you have. Be sure that you don’t cram your slides with text (stick to bullet points and images to emphasize key points).

And, if you’re looking for more inspiration to help you in scripting an oral research presentation. University of Virginia has a helpful oral presentation outline script .

A PhD Student working on an upcoming oral presentation.

Put yourself in your listeners shoes

As mentioned in the intro, research presentations are unique because they deal with specialized topics and complicated concepts. There’s a good chance that a large section of your audience won’t have the same understanding of your topic area as you do. So, do your best to understand where your listeners are at and adapt your language/definitions to that.

There’s an increasing awareness around the importance of scientific communication. Comms experts have even started giving TED Talks on how to bridge the gap between science and the public (check out Talk Nerdy to Me ). A general communication tip is to find out what sort of audience will listen to your talk. Then, beware of using jargon and acronyms unless you're 100% certain that your audience knows what they mean.

On the other end of the spectrum, you don’t want to underestimate your audience. Giving too much background or spending ages summarizing old work to a group of experts in the field would be a waste of valuable presentation time (and would put you at risk of losing your audience's interest).

Finally, if you can, practice your presentation on someone with a similar level of topic knowledge to the audience you’ll be presenting to.

Use scientific storytelling in your presentation

In scenarios where it’s appropriate, crafting a story allows you to break free from the often rigid tone of scientific communications. It helps your brain hit the refresh button and observe your findings from a new perspective. Plus, it can be a lot of fun to do!

If you have a chance to use scientific storytelling in your presentation, take full advantage of it. The best way to weave a story for your audience into a presentation is by setting the scene during your introduction. As you set the context of your research, set the context of your story/example at the same time. Continue drawing those parallels as you present. Then, deliver the main message of the story (or the “Aha!”) moment during your presentation’s conclusion.

If delivered well, a good story will keep your audience on the edge of their seats and glued to your entire presentation.

Emphasize the “Why” (not the “How”) of your research

Along the same lines as using storytelling, it’s important to think of WHY your audience should care about your work. Find ways to connect your research to valuable outcomes in society. Take your individual points on each slide and bring things back to the bigger picture. Constantly remind your listeners how it’s all connected and why that’s important.

One helpful way to get in this mindset is to look back to the moment before you became an expert on your topic. What got you interested? What was the reason for asking your research question? And, what motivated you to power through all the hard work to come? Then, looking forward, think about what key takeaways were most interesting or surprised you the most. How can these be applied to impact positive change in your research field or the wider community?

Be picky about what you include

It’s tempting to discuss all the small details of your methods or findings. Instead, focus on the most important information and takeaways that you think your audience will connect with. Decide on these takeaways before you script your presentation so that you can set the scene properly and provide only the information that has an added value.

When it comes to choosing data to display in your presentation slides, keep it simple. Wherever possible, use visuals to communicate your findings as opposed to large tables filled with numbers. This article by Richard Chambers has some great tips on using visuals in your slides and graphs.

Hide your complex tables and data in additional slides

With the above tip in mind: Just because you don’t include data and tables in your main presentation slides, doesn’t mean you can’t keep them handy for reference. If there’s a Q&A session after your presentation (or if you’ll be sharing your slides to view on-demand after) one great trick is to include additional slides/materials after your closing slide. You can keep these in your metaphorical “back pocket” to refer to if a specific question is asked about a data set or method. They’re also handy for people viewing your presentation slides later that might want to do a deeper dive into your methods/results.

However, just because you have these extra slides doesn’t mean you shouldn’t make the effort to make that information more accessible. A research conference platform like Fourwaves allows presenters to attach supplementary materials (figures, posters, slides, videos and more) that conference participants can access anytime.

Leave your audience with (a few) questions

Curiosity is a good thing. Whether you have a Q&A session or not, you should want to leave your audience with a few key questions. The most important one:

“Where can I find out more?”

Obviously, it’s important to answer basic questions about your research context, hypothesis, methods, results, and interpretation. If you answer these while focusing on the “Why?” and weaving a good story, you’ll be setting the stage for an engaging Q&A session and/or some great discussions in the halls after your presentation. Just be sure that you have further links or materials ready to provide to those who are curious.

Conclusion: The true expert in your research presentation

Throughout the entire process of scripting, creating your slides, and presenting, it’s important to remember that no one knows your research better than you do. If you’re nervous, remind yourself that the people who come to listen to your presentation are most likely there due to a genuine interest in your work. The pressure isn’t to connect with an uninterested audience - it’s to make your research more accessible and relevant for an already curious audience.

Finally, to practice what we preached in our last tip: If you’re looking to learn more about preparing for a research presentation, check out our articles on how to dress for a scientific conference and general conference presentation tips .

5 Best Event Registration Platforms for Your Next Conference

By having one software to organize registrations and submissions, a pediatric health center runs aro...

5 Essential Conference Apps for Your Event

In today’s digital age, the success of any conference hinges not just on the content and speakers bu...

Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

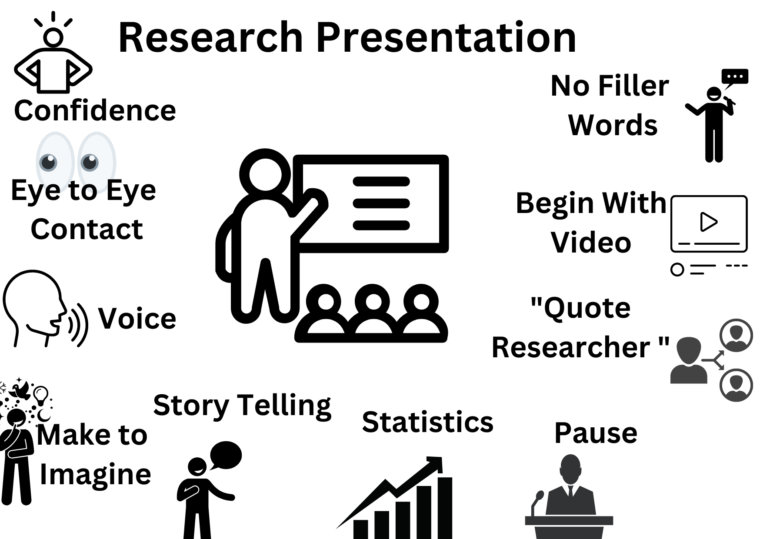

12 Proven Tips to Make an Effective Research Presentation as an Invited Speaker

Guidance from an Experienced Mentor

The evolution of my presentation skills, what is there in this post for you, research presentation tip #1: start confidently, research presentation tip #2: eye to eye contact with the audience, research presentation tip #3: welcome your audience, research presentation tip #4: adjust your voice.

- Research Presentation Tip #5: Memorize your Opening Line

- Research Presentation Tip #6: Use the words “ 'Think for while', 'Imagine', 'Think of', 'Close Your Eyes' ”

Research Presentation Tip #7: Story Telling

Research presentation tip #8: facts and statistics.

- Research Presentation Tip #9: Power of "Pause"

Research Presentation Tip #10: Quote a Great Researcher

Research presentation tip #11: begin with a video, research presentation tip #12: avoid using filler words, side benefits of giving great research presentations, how should i dress for my invited talk at a research conference, can i share my conference presentation slides after my talk with the audience, shall i entertain questions in between my presentation as an invited speaker to a research conference, can you give some tips for a successful q&a session:.

- How to handle questions where I don't know the answers in my presentation?

Introduction

In this blog post, I’ll be sharing with you some invaluable tips for delivering an effective research presentation, drawn from my own journey through academia. These tips are not just theoretical; they’re the result of my own experiences and the guidance I received along the way.

When I first embarked on my PhD journey, the prospect of presenting my research to an audience filled me with a mixture of excitement and apprehension. Like many researchers, I was eager to share my findings and insights, but I lacked the confidence and experience to do so effectively.

It wasn’t until I had been immersed in my research for nearly a year, clarifying my domain, objectives, and problem statements, that I was presented with an opportunity to speak about my work. However, despite my preparation, I found myself struggling to convey my ideas with clarity and confidence.

Fortunately, I was not alone in this journey. At the event where I was scheduled to present my research, there was another presenter—an experienced professor—who took notice of my nerves and offered his guidance. He generously shared with me a set of tips that would not only improve my presentation that day but also become the foundation for my future presentations.

As I incorporated these tips into my presentations, I noticed a remarkable improvement in my ability to engage and inform my audience. Each tip—from starting confidently to utilizing storytelling and incorporating facts and statistics—contributed to a more polished and impactful presentation style.

As an invited speaker, delivering an effective research presentation is essential to engage and inform your audience. A well-crafted presentation can help you communicate your research findings, ideas, and insights in a clear, concise, and engaging manner.

However, many presenters face challenges when it comes to delivering a successful presentation. Some of these challenges include nervousness, lack of confidence, and difficulty connecting with the audience.

In this article, we will discuss tips to help you make an effective research presentation as an invited speaker. We will cover strategies to prepare for your presentation, ways to deliver your presentation with confidence and impact, and common mistakes to avoid.

By following these tips, you can improve your presentation skills and create a compelling and engaging talk that resonates with your audience.

Tips to Make an Effective Research Presentation

- Tip 1: Start confidently

- Tip 2: Eye To Eye Contact With the Audience

- Tip 3: Welcome Your Audience

- Tip 4: Adjust your Voice

- Tip 5: Memorize your Opening Line

- Tip 6: Use the words “ ‘Think for while’, ‘Imagine’, ‘Think of’, ‘Close Your Eyes’ ”

- Tip 7: Story Telling

- Tip 8: Facts and Statistics

- Tip 9: Power of “Pause”

- Tip 10: Quote a Great Researcher

- Tip 11: Begin with a Video

- Tip 12: Avoid using Filler Words

Starting your presentation confidently is essential as it sets the tone for the rest of your presentation. It will help you grab your audience’s attention and make them more receptive to your message. Here are a few ways you can start confidently.

- Begin with a self-introduction: Introduce yourself to the audience and establish your credibility. Briefly mention your educational background, your professional experience, and any relevant achievements that make you an authority on the topic. For example, “Good morning everyone, my name is John and I’m a researcher at XYZ University. I have a Ph.D. in molecular biology, and my research has been published in several reputable journals.”

- Introduce the topic: Clearly state the purpose of your presentation and provide a brief overview of what you’ll be discussing. This helps the audience understand the context of your research and what they can expect from your presentation. For example, “Today, I’ll be presenting my research on the role of DNA repair mechanisms in cancer development. I’ll be discussing the current state of knowledge in this field, the methods we used to conduct our research and the novel insights we’ve gained from our findings.”

- Start with a strong opening statement: Once you’ve introduced yourself and the topic, start your presentation confidently with a statement that captures the audience’s attention and makes them curious to hear more. As mentioned earlier, you could use a strong opening statement, a powerful visual aid, or show enthusiasm for your research. For example:

- “Have you ever wondered how artificial intelligence can be used to predict user behaviour? Today, I’ll be sharing my research on the latest AI algorithms and their potential applications in the field of e-commerce.”

- “Imagine a world where cybersecurity threats no longer exist. My research is focused on developing advanced security measures that can protect your data from even the most sophisticated attacks.”

- “Think for a moment about the amount of data we generate every day. My research focuses on how we can use machine learning algorithms to extract meaningful insights from this vast amount of data, and ultimately drive innovation in industries ranging from healthcare to finance.”

By following these steps, you’ll be able to start your research presentation confidently, establish your credibility and expertise, and create interest in your topic.

Speaking confidently as an invited speaker can be a daunting task, but there are ways to prepare and feel more confident. One such way is through practising yoga. Yoga is a great tool for reducing stress and anxiety, which can be major barriers to confident public speaking.

By practising yoga, you can learn to control your breathing, calm your mind, and increase your focus and concentration. All of these skills can help you feel more centred and confident when it’s time to give your presentation.

If you’re interested in learning more about the benefits of yoga, check out our blog post on the subject YOGA: The Ultimate Productivity Hack for Ph.D. Research Scholars and Researchers .

If you’re ready to dive deeper and start your own yoga practice, be sure to download my e-book on :

Unlock Your Research Potential Through Yoga: A Research Scholar’s Companion

A large number of audiences in the presentation hall make you feel jittery and lose your confidence in no time. This happens because you are seeing many of the audience for the first time and you don’t know their background and their knowledge of the subject in which you are presenting.

The best way to overcome this fear is to go and attack the fear itself. That is come at least 10-15 minutes early to the conference room and start interacting with the people over there. This short span of connectivity with a few of the audience will release your tension.

When you occupy the stage for presenting, the first thing you need to do is gaze around the room, establish one-to-one eye contact, and give a confident smile to your audience whom you had just met before the start of the presentation.

Just gazing around the presentation hall will make you feel connected to everyone in the hall. Internally within your mind choose one of the audience and turn towards him/her make eye contact and deliver a few sentences, then proceed to the next audience and repeat the same set of steps.

This will make everyone in the room feel that you are talking directly to them. Make the audience feel that you are engaging with them personally for this topic, which makes them invest fully in your topic.

The third tip for making an effective research presentation is to welcome your audience. This means taking a few minutes to greet your audience, introduce yourself, and set the tone for your presentation. Here are a few ways you can welcome your audience:

- Greet your audience: Start by greeting your audience with a smile and a warm welcome. This will help you establish a connection with your audience and put them at ease.

- Introduce yourself: Introduce yourself to the audience and give a brief background on your expertise and how it relates to your presentation. This will help your audience understand your qualifications and why you’re the right person to be delivering the presentation.

- Explain the purpose of your presentation: Explain to your audience why you’re presenting your research and what they can expect to learn from your presentation. This will help your audience understand the context of your research and what they can expect from your presentation.

- Set the tone: Set the tone for your presentation by giving a brief overview of your presentation structure and what your audience can expect throughout your presentation. This will help your audience understand what to expect and keep them engaged.

Here are a few examples of how you can welcome your audience:

- If you’re presenting to a group of industry professionals, welcome them by acknowledging their expertise and experience. This will show that you value their knowledge and experience.

- If you’re presenting to a group of students or academics, welcome them by acknowledging their interest in your research area. This will help you establish a connection with your audience and show that you’re excited to share your research with them.

- If you’re presenting to a mixed audience, welcome them by acknowledging their diversity and the different perspectives they bring to the presentation. This will help you set an inclusive tone and show that you’re open to different viewpoints.

Overall, welcoming your audience is an important aspect of delivering an effective research presentation. It helps you establish a connection with your audience, set the tone for your presentation, and keep your audience engaged throughout your presentation.

In my earlier days of presentations, I just used to go on stage and start my presentations without greeting anyone. Later I learned stage etiquette with the help of my fellow research scholars and underwent professional etiquette courses .

The fourth tip for making an effective research presentation is to adjust your voice. This means using your voice effectively to convey your message and engage your audience. Here are a few ways you can adjust your voice during your research presentation:

- Speak clearly: Speak clearly and enunciate your words so that your audience can understand what you’re saying. Avoid speaking too fast or mumbling, which can make it difficult for your audience to follow your presentation.

- Use a varied pace: Use a varied pace to keep your audience engaged. Speak slowly and clearly when you’re making important points, and speed up when you’re discussing less important points. This will help you maintain your audience’s attention throughout your presentation.

- Use a varied pitch: Use a varied pitch to convey emotion and emphasize important points. Lower your pitch when you’re discussing serious or important topics, and raise your pitch when you’re excited or enthusiastic.

- Use pauses: Use pauses to emphasize important points and give your audience time to reflect on what you’re saying. Pausing also helps to break up your presentation and make it easier for your audience to follow.

Here are a few examples of how you can adjust your voice during your research presentation:

- If you’re discussing a complex or technical topic, speak slowly and clearly so that your audience can understand what you’re saying. Use pauses to emphasize important points and give your audience time to reflect on what you’re saying.

- If you’re discussing an exciting or enthusiastic topic, raise your pitch and use a varied pace to convey your excitement to your audience. This will help you engage your audience and keep them interested in your presentation.

- If you’re discussing a serious or emotional topic, lower your pitch and use a slower pace to convey the gravity of the situation. Use pauses to emphasize important points and give your audience time to process what you’re saying.

Overall, adjusting your voice is an important aspect of delivering an effective research presentation. It helps you convey your message clearly, engage your audience, and keep their attention throughout your presentation.

Many researchers are less talkative and speak with a very low voice and this makes their concepts unheard by other researchers. To overcome this drawback, they go for vocal coaching to improve their voice modulation.

Research Presentation Tip #5: Memorize your Opening Line

The fifth tip for making an effective research presentation is to memorize your opening line. This means having a powerful and memorable opening line that will grab your audience’s attention and set the tone for your presentation. Here are a few ways you can create a memorable opening line:

- Use a quote or statistic: Start your presentation with a powerful quote or statistic that relates to your research. This will grab your audience’s attention and show them why your research is important.

- Use a story or anecdote: Use a personal story or anecdote to illustrate the importance of your research. This will help you connect with your audience on an emotional level and show them why your research is relevant to their lives.

- Ask a question: Ask your audience a thought-provoking question that relates to your research. This will help you engage your audience and get them thinking about your topic.

Once you’ve created a memorable opening line, it’s important to memorize it so that you can deliver it confidently and without hesitation. Here are a few examples of powerful opening lines:

- “In the United States, someone dies of a drug overdose every seven minutes. Today, I want to talk to you about the opioid epidemic and what we can do to prevent it.”

- “When I was a child, my grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Today, I want to share with you the latest research on Alzheimer’s and what we can do to slow its progression.”

- “Have you ever wondered why some people are more resilient than others? Today, I want to talk to you about the science of resilience and how we can use it to overcome adversity.”

Overall, memorizing your opening line is an important aspect of delivering an effective research presentation. It helps you grab your audience’s attention, set the tone for your presentation, and establish your credibility as a speaker.

Remembering the concepts at the right time and in the right sequence is critical for every researcher. Few of my research scholars face the problem of forgetting everything once they reach the stage for presentation. To overcome this difficulty I gift them with one of my favourite books on improving memory power: “Limitless by Jim Quick” . This book has changed many lives. You can also try.

Research Presentation Tip #6: Use the words “ ‘Think for while’, ‘Imagine’, ‘Think of’, ‘Close Your Eyes’ ”

The sixth tip for making an effective research presentation is to use specific phrases that encourage your audience to think, imagine, and engage with your presentation. Here are a few examples of phrases you can use to encourage your audience to engage with your presentation:

- “Think for a moment about…” This phrase encourages your audience to reflect on a particular point or idea that you’ve just discussed. For example, “Think for a moment about the impact that climate change is having on our planet.”

- “Imagine that…” This phrase encourages your audience to visualize a particular scenario or idea. For example, “Imagine that you’re living in a world without access to clean water. How would your daily life be affected?”

- “Think of a time when…” This phrase encourages your audience to reflect on their own experiences and relate them to your presentation. For example, “Think of a time when you felt overwhelmed at work. How did you manage that stress?”

- “Close your eyes and picture…” This phrase encourages your audience to use their imagination to visualize a particular scenario or idea. For example, “Close your eyes and picture a world without poverty. What would that look like?”

By using these phrases, you can encourage your audience to actively engage with your presentation and think more deeply about your research. Here are a few examples of how you might incorporate these phrases into your presentation:

- “Think for a moment about the impact that our use of plastics is having on our environment. Each year, millions of tons of plastic end up in our oceans, harming marine life and polluting our planet.”

- “Imagine that you’re a scientist working to develop a cure for a deadly disease. What kind of research would you conduct, and what challenges might you face?”

- “Think of a time when you had to overcome a significant challenge. How did you persevere, and what lessons did you learn from that experience?”

- “Close your eyes and picture a world where renewable energy is our primary source of power. What benefits would this have for our planet, and how can we work together to make this a reality?”

Overall, using phrases that encourage your audience to think and engage with your presentation is an effective way to make your research presentation more impactful and memorable.

The seventh tip for making an effective research presentation is to incorporate storytelling into your presentation. Storytelling is a powerful way to connect with your audience, illustrate your points, and make your research more engaging and memorable.

People love stories, but your story has to be relevant to your research. You can craft a story about an experience you had and tell how you could able to define your research problem based on the experience you had. This makes your presentation both interesting and incorporates information about the work you are carrying out.

Storytelling or sharing your own experience is the best way to connect with your audience. Many researchers use this technique and it remains one of the most critical pieces to becoming an effective presenter.

Here are a few examples of how you can incorporate storytelling into your presentation:

- Personal stories: Use a personal story to illustrate the importance of your research. For example, if you’re researching a new cancer treatment, you might share a story about a friend or family member who has been affected by cancer. This personal connection can help your audience relate to your research on a more emotional level.

- Case studies: Use a case study to illustrate how your research has been applied in the real world. For example, if you’re researching the impact of a new educational program, you might share a case study about a school that has implemented the program and seen positive results.

- Historical examples: Use a historical example to illustrate the significance of your research. For example, if you’re researching the impact of climate change, you might share a story about the Dust Bowl of the 1930s to illustrate the devastating effects of drought and soil erosion.

- Analogies: Use an analogy to explain complex concepts or ideas. For example, if you’re researching the workings of the brain, you might use the analogy of a computer to help your audience understand how neurons communicate with each other.

By incorporating storytelling into your presentation, you can help your audience connect with your research on a more personal level and make your presentation more memorable. Here are a few examples of how you might incorporate storytelling into your presentation:

- “When my mother was diagnosed with cancer, I felt helpless and afraid. But thanks to the groundbreaking research that is being done in this field, we now have more treatment options than ever before. Today, I want to share with you the latest research on cancer treatments and what we can do to support those who are fighting this disease.”

- “Imagine for a moment that you’re a small business owner trying to grow your online presence. You’ve heard that search engine optimization (SEO) is important for driving traffic to your website, but you’re not sure where to start. That’s where my research comes in. By analyzing millions of search queries, I’ve identified the key factors that search engines use to rank websites. Using this information, I’ve developed a new algorithm that can help businesses like yours optimize their websites for better search engine rankings. Imagine being able to reach more customers and grow your business, all thanks to this new algorithm. That’s the power of my research.”

In these examples, the speaker is using storytelling to help the audience understand the real-world impact of their research in a relatable way. By framing the research in terms of a relatable scenario, the speaker is able to engage the audience and make the research feel more relevant to their lives. Additionally, by highlighting the practical applications of the research, the speaker is able to demonstrate the value of the research in a tangible way.

Here I recommend without any second thought “ Storytelling with Data: A Data Visualization Guide for Business Professionals ” by Cole Nussbaumer Knaflic. This is one of the powerful techniques to showcase data in the form of graphs and charts.

The eighth tip for making an effective research presentation is to incorporate facts and statistics into your presentation. Facts and statistics can help you communicate the significance of your research and make it more compelling to your audience.

Make your audience curious about your topic with a fact they didn’t know. Explaining the importance of your topic to your audience is essential. Showcasing data and statistics to prove a point remains a critical strategy not just at the beginning but also throughout. Statistics can be mind-numbing but if there is some compelling information that can help further the conversation.

Here are a few examples of how you might use facts and statistics in your research presentation:

- Contextualize your research: Use statistics to provide context for your research. For example, if you’re presenting on the prevalence of a particular disease, you might start by sharing statistics on how many people are affected by the disease worldwide.

- Highlight key findings: Use facts and statistics to highlight the key findings of your research. For example, if you’re presenting on new drug therapy, you might share statistics on the success rate of the therapy and how it compares to existing treatments.

- Support your arguments: Use facts and statistics to support your arguments. For example, if you’re arguing that a particular policy change is needed, you might use statistics to show how the current policy is failing and why a change is necessary.

- Visualize your data: Use graphs, charts, and other visual aids to help illustrate your data. This can make it easier for your audience to understand the significance of your research. For example, if you’re presenting on the impact of climate change, you might use a graph to show the rise in global temperatures over time.

Here’s an example of how you might use facts and statistics in a research presentation:

“Did you know that over 80% of internet users own a smartphone? That’s a staggering number when you think about it. And with the rise of mobile devices, it’s more important than ever for businesses to have a mobile-friendly website. That’s where my research comes in.

By analyzing user behaviour and website performance data, I’ve identified the key factors that make a website mobile-friendly. And the results are clear: mobile-friendly websites perform better in search engine rankings, have lower bounce rates, and are more likely to convert visitors into customers. By implementing the recommendations from my research, businesses can improve their online presence and reach more customers than ever before.”

In this example, the speaker is using statistics to provide context for their research (the high prevalence of smartphone ownership) and to support their argument (that businesses need to have mobile-friendly websites).

By emphasizing the benefits of mobile-friendly websites (better search engine rankings, lower bounce rates, and higher conversion rates), the speaker is able to make the research more compelling to their audience. Finally, by using concrete examples (implementing the recommendations from the research), the speaker is able to make the research feel actionable and relevant to the audience.

In my blog posts on the benefits of using graphs and tables in research presentations, I have presented different ways that these tools can enhance the impact and effectiveness of your research presentation. By incorporating graphs and tables, you can help your audience to engage more deeply with your research and better grasp the significance of your findings. To learn more about the benefits of using graphs and tables in research presentations, check out my blog posts listed below, on the subject.

- Maximizing the Impact of Your Research Paper with Graphs and Charts

- Best Practices for Designing and Formatting Tables in Research Papers

You can also refer the book “Information Visualization: An Introduction” for getting more clarity on the representation of facts and statistics.

Research Presentation Tip #9: Power of “Pause”

The ninth tip for making an effective research presentation is to use the power of “pause.” Pausing at key moments in your presentation can help you emphasize important points, allow your audience to process information, and create a sense of anticipation.

We are all uncomfortable when there is a pause. Yet incorporating pause into your presentation can be a valuable tool causing the audience to be attentive to what you are going to say next.

A pause is an effective way to grab attention. There are two ways you might use this technique. After you are introduced, walk on stage and say nothing. Simply pause for three to five seconds and wait for the full attention of the audience. It’s a powerful opening. Depending on the audience, you might need to pause for longer than five seconds.

At another point in your presentation, you might be discussing the results or you are about to provide important information, that’s when you pause to grab attention. You’ll probably feel uncomfortable when you first try this technique, but it’s worth mastering.

Here are a few examples of how you might use the power of the pause in your research presentation:

- Emphasize key points: Pause briefly after making an important point to allow your audience to absorb the information. For example, if you’re presenting on the benefits of a new product, you might pause after stating the most compelling benefits to give your audience time to reflect on the information.

- Create anticipation: Pause before revealing a key piece of information or making a surprising statement. This can create a sense of anticipation in your audience and keep them engaged. For example, if you’re presenting on the results of a study, you might pause before revealing the most surprising or unexpected finding.

- Allow time for reflection: Pause after asking a thought-provoking question to give your audience time to reflect on their answer. This can help create a more interactive and engaging presentation. For example, if you’re presenting on the impact of social media on mental health, you might pause after asking the audience to reflect on their own social media use.

- Control the pace: Use pauses to control the pace of your presentation. Pausing briefly before transitioning to a new topic can help you signal to your audience that you’re about to move on. This can help prevent confusion and make your presentation more organized.

Here’s an example of how you might use the power of the pause in a research presentation:

“Imagine being able to reduce the risk of heart disease by 50%. That’s the potential impact of my research. By analyzing the diets and lifestyles of over 10,000 participants, I’ve identified the key factors that contribute to heart disease. And the results are clear: by making a few simple changes to your diet and exercise routine, you can significantly reduce your risk of heart disease. So, what are these changes? Pause for effect. It turns out that the most important factors are a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, regular exercise, and limited alcohol consumption.”

In this example, the speaker is using the pause to create anticipation before revealing the most important findings of their research. By pausing before revealing the key factors that contribute to heart disease, the speaker is able to create a sense of anticipation and emphasize the importance of the information. By using the power of the pause in this way, the speaker is able to make their research presentation more engaging and memorable for the audience.

The tenth tip for making an effective research presentation is to quote a great researcher. By including quotes from respected researchers or experts in your field, you can add credibility to your presentation and demonstrate that your research is supported by other respected professionals.

Quoting someone who is a well-known researcher in your field is a great way to start any presentation. Just be sure to make it relevant to the purpose of your speech and presentation. If you are using slides, adding a picture of the person you are quoting will add more value to your presentation.

Here are a few examples of how you might use quotes in your research presentation:

- Begin with a quote: Starting your presentation with a quote from a respected researcher can help set the tone and establish your credibility. For example, if you’re presenting on the benefits of exercise for mental health, you might begin with a quote from a well-known psychologist or psychiatrist who has researched the topic.

- Use quotes to support your argument: Including quotes from experts who support your argument can help reinforce your ideas and add credibility to your presentation. For example, if you’re presenting on the importance of early childhood education, you might include a quote from a respected educational psychologist who has studied the topic.