Chapter 5: The problem of free will and determinism

The problem of free will and determinism

Matthew Van Cleave

“You say: I am not free. But I have raised and lowered my arm. Everyone understands that this illogical answer is an irrefutable proof of freedom.”

-Leo Tolstoy

“Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills.”

-Arthur Shopenhauer

“None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.”

-Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

The term “freedom” is used in many contexts, from legal, to moral, to psychological, to social, to political, to theological. The founders of the United States often extolled the virtues of “liberty” and “freedom,” as well as cautioned us about how difficult they were to maintain. But what do these terms mean, exactly? What does it mean to claim that humans are (or are not) free? Almost anyone living in a liberal democracy today would affirm that freedom is a good thing, but they almost certainly do not all agree on what freedom is. With a concept as slippery as that of free will, it is not surprising that there is often disagreement. Thus, it will be important to be very clear on what precisely we are talking about when we are either affirming or denying that humans have free will. There is an important general point here that extends beyond the issue of free will: when debating whether or not x exists, we must first be clear on defining x, otherwise we will end up simply talking past each other . The philosophical problem of free will and determinism is the problem of whether or not free will exists in light of determinism. Thus, it is crucial to be clear in defining what we mean by “free will” and “determinism.” As we will see, these turn out to be difficult and contested philosophical questions. In this chapter we will consider these different positions and some of the arguments for, as well as objections to, them.

Let’s begin with an example. Consider the 1998 movie, The Truman Show . In that movie the main character, Truman Burbank (played by Jim Carrey), is the star of a reality television show. However, he doesn’t know that he is. He believes he is just an ordinary person living in an ordinary neighborhood, but in fact this neighborhood is an elaborate set of a television show in which all of his friends and acquaintances are just actors. His every moment is being filmed and broadcast to a whole world of fans that he doesn’t know exists and almost every detail of his life has been carefully orchestrated and controlled by the producers of the show. For example, Truman’s little town is surrounded by a lake, but since he has been conditioned to believe (falsely) that he had a traumatic boating accident in which his father died, he never has the desire to leave the small little town and venture out into the larger world (at least at first). So consider the life of Truman as described above. Is he free or not? On the one hand, he gets to do pretty much everything he wants to do and he is pretty happy. Truman doesn’t look like he’s being coerced in any explicit way and if you asked him if he was, he would almost certain reply that he wasn’t being coerced and that he was in charge of his life. That is, he would say that he was free (at least to the same extent that the rest of us would). These points all seem to suggest that he is free. For example, when Truman decides that he would rather not take a boat ride out to explore the wider world (which initially is his decision), he is doing what he wants to do. His action isn’t coerced and does not feel coerced to him. In contrast, if someone holds a gun to my head and tells me “your wallet or your life!” then my action of giving him my wallet is definitely coerced and feels so.

On the other hand, it seems clear the Truman’s life is being manipulated and controlled in a way that undermines his agency and thus his freedom. It seems clear that Truman is not the master of his fate in the way that he thinks he is. As Goethe says in the epigraph at the beginning of this chapter, there’s a sense in which people like Truman are those who are most helplessly enslaved, since Truman is subject to a massive illusion that he has no reason to suspect. In contrast, someone who knows she is a slave (such as slaves in the antebellum South in the United States) at least retains the autonomy of knowing that she is being controlled. Truman seems to be in the situation of being enslaved and not knowing it and it seems harder for such a person to escape that reality because they do not have any desire to (since they don’t know they are being manipulated and controlled).

As the Truman Show example illustrates, it seems there can be reasonable disagreement about whether or not Truman is free. On the one hand, there’s a sense in which he is free because he does what he wants and doesn’t feel manipulated. On the other hand, there’s a sense in which he isn’t free because what he wants to do is being manipulated by forces outside of his control (namely, the producers of the show). An even better example of this kind of thing comes from Aldous Huxley’s classic dystopia, Brave New World . In the society that Huxley envisions, everyone does what they want and no one is ever unhappy. So far this sounds utopic rather than dystopic. What makes it dystopic is the fact that this state of affairs is achieved by genetic and behavioral conditioning in a way that seems to remove any choice. The citizens of the Brave New World do what they want, yes, but they seems to have absolutely no control over what they want in the first place. Rather, their desires are essentially implanted in them by a process of conditioning long before they are old enough to understand what is going on. The citizens of Brave New World do what they want, but they have no control over what the want in the first place. In that sense, they are like robots: they only have the desires that are chosen for them by the architects of the society.

So are people free as long as they are doing what they want to—that is, choosing the act according to their strongest desires? If so, then notice that the citizens of Brave New World would count as free, as would Truman from The Truman Show , since these are both cases of individuals who are acting on their strongest desires. The problem is that those desires are not desires those individuals have chosen. It feels like the individuals in those scenarios are being manipulated in a way that we believe we aren’t. Perhaps true freedom requires more than just that one does what one most wants to do. Perhaps true freedom requires a genuine choice. But what is a genuine choice beyond doing what one most wants to do?

Philosophers are generally of two main camps concerning the question of what free will is. Compatibilists believe that free will requires only that we are doing what we want to do in a way that isn’t coerced—in short, free actions are voluntary actions. Incompatibilists , motivated by examples like the above where our desires are themselves manipulated, believe that free will requires a genuine choice and they claim that a choice is genuine if and only if, were we given the choice to make again, we could have chosen otherwise . I can perhaps best crystalize the difference between these two positions by moving to a theological example. Suppose that there is a god who created the universe, including humans, and who controls everything that goes on in the universe, including what humans do. But suppose that god does this not my directly coercing us to do things that we don’t want to do but, rather, by implanting the desire in us to do what god wants us to do. Thus human beings, by doing what the want to do, would actually be doing what god wanted them to do. According to the compatibilist, humans in this scenario would be free since they would be doing what they want to do. According to the incompatibilist, however, humans in this scenario would not be free because given the desire that god had implanted in them, they would always end up doing the same thing if given the decision to make (assuming that desires deterministically cause behaviors). If you don’t like the theological example, consider a sci-fi example which has the same exact structure. Suppose there is an eccentric neuroscientist who has figured out how to wire your brain with a mechanism by which he can implant desire into you.

Suppose that the neuroscientist implants in you the desire to start collecting stamps and you do so. However, you know none of this (the surgery to implant the device was done while you were sleeping and you are none the wiser).

From your perspective, one day you find yourself with the desire to start collecting stamps. It feels to you as though this was something you chose and were not coerced to do. However, the reality is that given this desire that the neuroscientist implanted in you, you could not have chosen not to have started collecting stamps (that is, you were necessitated to start collecting stamps, given the desire). Again, in this scenario the compatibilist would say that your choice to start collecting stamps was free (since it was something you wanted to do and did not feel coerced to you), but the incompatibilist would say that your choice was not free since given the implantation of the desire, you could not have chosen otherwise.

We have not quite yet gotten to the nub of the philosophical problem of free will and determinism because we have not yet talked about determinism and the problem it is supposed to present for free will. What is determinism?

Determinism is the doctrine that every cause is itself the effect of a prior cause. More precisely, if an event (E) is determined, then there are prior conditions (C) which are sufficient for the occurrence of E. That means that if C occurs, then E has to occur. Determinism is simply the claim that every event in the universe is determined. Determinism is assumed in the natural sciences such as physics, chemistry and biology (with the exception of quantum physics for reasons I won’t explain here). Science always assumes that any particular event has some law-like explanation—that is, underlying any particular cause is some set of law- like regularities. We might not know what the laws are, but the whole assumption of the natural sciences is that there are such laws, even if we don’t currently know what they are. It is this assumption that leads scientists to search for causes and patterns in the world, as opposed to just saying that everything is random. Where determinism starts to become contentious is when we move into the human sciences, such as psychology, sociology, and economics. To illustrate why this is contentious, consider the famous example of Laplace’s demon that comes from Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1814:

We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.

Laplace’s point is that if determinism were true, then everything that every happened in the universe, including every human action ever undertaken, had to have happened. Of course humans, being limited in knowledge, could never predict everything that would happen from here out, but some being that was unlimited in intelligence could do exactly that. Pause for a moment to consider what this means. If determinism is true, then Laplace’s demon would have been able to predict from the point of the big bang, that you would be reading these words on this page at this exact point of time. Or that you had what you had for breakfast this morning. Or any other fact in the universe. This seems hard to believe, since it seems like some things that happen in the universe didn’t have to happen. Certain human actions seem to be the paradigm case of such events. If I ate an omelet for breakfast this morning, that may be a fact but it seems strange to think that this fact was necessitated as soon as the big bang occurred. Human actions seem to have a kind of independence from web of deterministic web of causes and effects in a way that, say, billiard balls don’t.

Given that the cue ball his the 8 ball with a specific velocity, at a certain angle, and taking into effect the coefficient of friction of the felt on the pool table, the exact location of the 8 ball is, so to speak, already determined before it ends up there. But human behavior doesn’t seem to be like the behavior of the 8 ball in this way, which is why some people think that the human sciences are importantly different than the natural sciences. Whether or not the human sciences are also deterministic is an issue that helps distinguish the different philosophical positions one can take on free will, as we will see presently. But the important point to see right now is that determinism is a doctrine that applies to all causes, including human actions. Thus, if some particular brain state is what ultimately caused my action and that brain state itself was caused by a prior brain state, and so on, then my action had to occur given those earlier prior events. And that entails that I couldn’t have chosen to act otherwise, given that those earlier events took place . That means that the incompatibilist position on free will cannot be correct if determinism is true. Recall that incompatibilism requires that a choice is free only if one could have chosen differently, given all the same initial conditions. But if determinism is true, then human actions are no different than the 8 ball: given what has come before, the current event had to happen. Thus, if this morning I cooked an omelet, then my “choice” to make that omelet could not have been otherwise. Given the complex web of prior influences on my behavior, my making that omelet was determined. It had to occur.

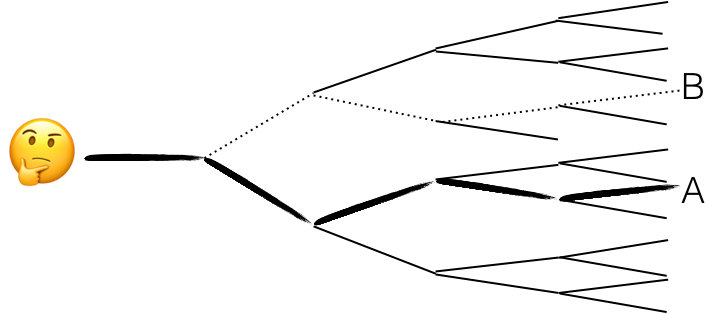

Of course, it feels to us, when contemplating our own futures, that there are many different possible ways our lives might go—many possible choices to be made. But if determinism is true, then this is an illusion. In reality, there is only one way that things could go, it’s just that we can’t see what that is because of our limited knowledge. Consider the figure below. Each junction in the figure below represents a decision I make and let’s suppose that some (much larger) decision tree like this could represent all of the possible ways my life could go. At any point in time, when contemplating what to do, it seems that I can conceive of my life going many different possible ways. Suppose that A represents one series of choices and B another. Suppose, further, that A represents what I actually do (looking backwards over my life from the future). Although from this point in time it seems that I could also have made the series of choices represented in B, if determinism is true then this is false. That is, if A is what ends up happening, then A is the only thing that ever could have happened . If it hasn’t yet hit you how determinism conflicts with our sense of our own possibilities in life, think about that for a second.

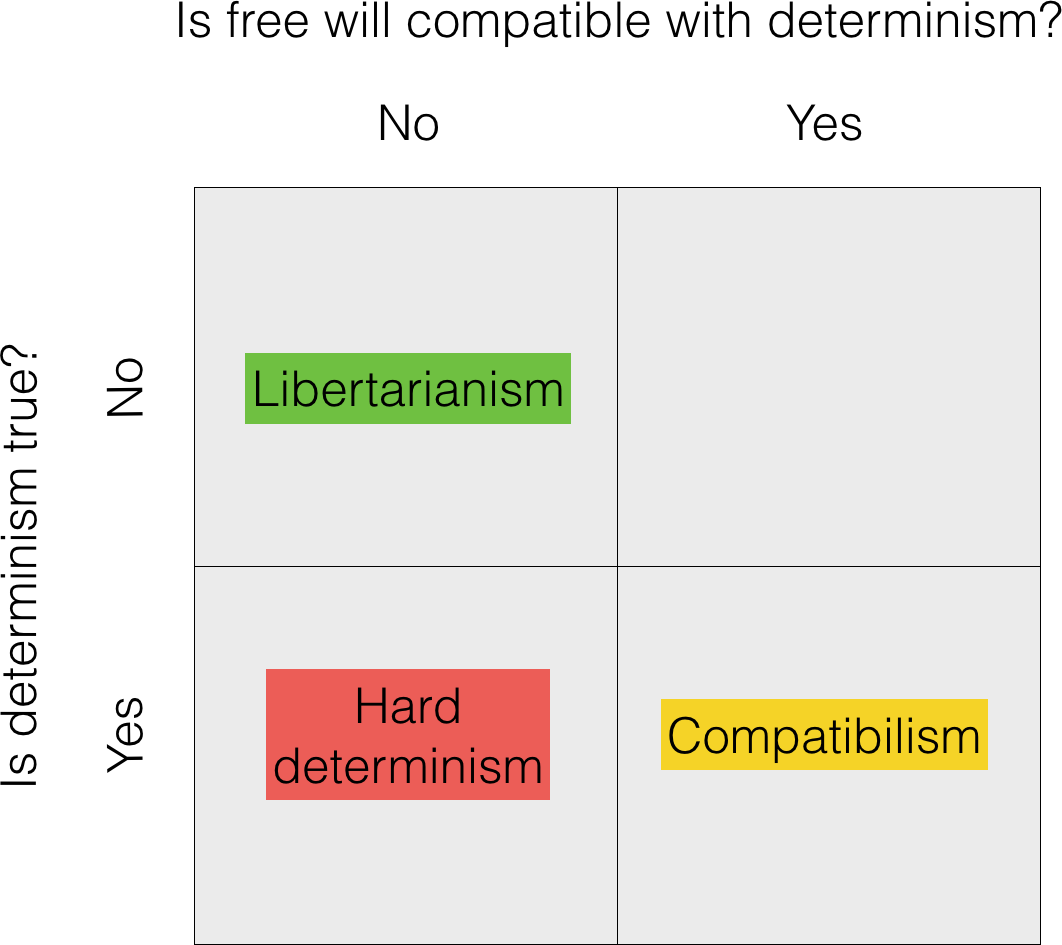

As the foregoing I hope makes clear, the incompatibilist definition of free will is incompatibile with determinism (that’s why it’s called “incompatibilist”). But that leaves open the question of which one is true. To say that free will and determinism are logically incompatible is just to say that they cannot both be true, meaning that one or the other must be false. But which one? Some will claim that it is determinism which is false. This position is called libertarianism (not to be confused with political libertarianism, which is a totally different idea). Others claim that determinism is true and that, therefore, there is no free will. This position is called hard determinism. A third type of position, compatibilism , rejects the incompatibilist definition of freedom and claims that free will and determinism are compatible (hence the name). The table below compares these different positions. But which one is correct? In the remainder of the chapter we will consider some arguments for and against these three positions on free will and determinism.

Libertarianism

Both libertarianism and hard determinism accept the following proposition: If determinism is true, then there is no free will. What distinguishes libertarianism from hard determinism is the libertarian’s claim that there is free will. But why should we think this? This question is especially pressing when we recognize that we assume a deterministic view in many other domains in life. When you have a toothache, we know that something must have caused that toothache and whatever cause that was, something else must have caused that cause. It would be a strange dentist who told you that your toothache didn’t have a cause but just randomly occurred. When the weather doesn’t go as the meteorologist predicts, we assume there must be a cause for why the weather did what it did. We might not ever know the cause in all its specific details, but assume there must be one. In cases like meteorology, when our scientific predictions are wrong, we don’t always go back and try to figure out what the actual causes were—why our predictions were wrong. But in other cases we do. Consider the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1986. Years later it was finally determined what led to that explosion (“O-ring” seals that were not designed for the colder condition of the launch). There’s a detailed deterministic physical explanation that one could give of how the failure of those O-rings led to the explosion of the Challenger. In all of these cases, determinism is the fundamental assumption and it seems almost nothing could overturn it.

But the libertarian thinks that the domain of human action is different than every other domain. Humans are somehow able to rise above all of the influences on them and make decisions that are not themselves determined by anything that precedes them. The philosopher Roderick Chisholm accurately captured the libertarian position when he claimed that “we have a prerogative which some would attribute only to God: each of us, when we really act, is a prime mover unmoved. In doing what we do, we cause certain events to happen, and nothing and no one, except we ourselves, causes us to cause those events to happen” (Chisholm, 1964). But why should we think that we have such a godlike ability? We will consider two arguments the libertarian makes in support of her position: the argument from intuitions and the argument from moral responsibility.

The argument from intuitions is based on the very strong intuition that there are some things that we have control over and that nothing causes us to do those things except for our own willing them. The strongest case for this concerns very simple actions, such as moving one’s finger. Suppose that I hold up my index finger and say that I am going to move it to the right or the to the left, but that I have not yet decided which way to move it. At the moment before I move my finger one way or the other, it truly seems to me that my future is open.

Nothing in my past and nothing in my present seems to be determining me to move my finger to the right or to the left. Rather, it seems to me that I have total control over what happens next. Whichever way I move my finger, it seems that I could have moved it the other way. So if, as a matter of fact, I move my finger to the right, it seems unquestionably true that I could have moved it to the left (and vice versa, mutatis mutandis ). Thus, in cases of simple actions like moving my finger to the right or left, it seems that the strong incompatibilist definition of freedom is met: we have a very strong intuition that no matter what I actually did, I could have chosen otherwise, were I to be given that exact choice again . The libertarian does not claim that all human actions are like this. Indeed, many of our actions (perhaps even ones that we think are free) are determined by prior causes. The libertarian’s claim is just that at least some of our actions do meet the incompatibilist’s definition of free and, thus, that determinism is not universally true.

The argument from moral responsibility is a good example of what philosophers call a transcendental argument . Transcendental arguments attempt to establish the truth of something by showing that that thing is necessary in order for something else, which we strongly believe to be true, to be true. So consider the idea that normally developed adult human beings are morally responsible for their actions. For example, if Bob embezzles money from his charity in order to help pay for a new sports car, we would rightly hold Bob accountable for this action. That is, we would punish Bob and would see punishment as appropriate. But a necessary condition of holding Bob responsible is that Bob’s action was one that he chose, one that he was in control of, one that he could have chosen not to do. Philosophers call this principle ought implies can : if we say that someone ought (or ought not) do something, this implies that they can do it (that is, they are capable of doing it). The ought implies can principle is consistent with our legal practices. For example, in cases where we believe that a person was not capable of doing the right thing, we no longer hold them morally or criminally liable. A good example of this within our legal system is the insanity defense: if someone was determined to be incapable of appreciating the difference between right and wrong, we do not find them guilty of a crime. But notice what determinism would do to the ought implies can principle. If everything we ever do had to happen (think Laplace’s demon), that means that Bob had to embezzle those funds and buy that sports car. The universe demanded it. That means he couldn’t not have done those things. But if that is so, then, by the ought implies can principle, we cannot say that he ought not to have done those things. That is, we cannot hold Bob morally responsible for those things. But this seems absurd, the libertarian will say.

Surely Bob was responsible for those things and we are right to hold him responsible. But the only we way can reasonably do this is if we assume that his actions were chosen—that he could have chosen to do otherwise than he in fact chose. Thus, determinism is incompatible with the idea that human beings are morally responsible agents. The practice of holding each other to be morally responsible agents doesn’t make sense unless humans have incompatibilist free will—unless they could have chosen to do otherwise than they in fact did. That is the libertarian’s transcendental argument from moral responsibility.

Hard determinism

Hard determinism denies that there is free will. The hard determinist is a “tough-minded” individual who bravely accepts the implication of a scientific view of the world. Since we don’t in general accept that there are causes that are not themselves the result of prior causes, we should apply this to human actions too. And this means that humans, contrary to what they might believe (or wish to believe) about themselves, do not have free will. As noted above, hard determininsm follows from accepting the incompatibilist definition of free will as well as the claim that determinism is universally true. One of the strongest arguments in favor of hard determinism is based on the weakness of the libertarian position. In particular, the hard determinist argues that accepting the existence of free will leaves us with an inexplicable mystery: how can a physical system initiate causes that are not themselves caused?

If the libertarian is right, then when an action is free it is such that given exactly the same events leading up to one’s action, one still could have acted otherwise than they did. But this seems to require that the action/choice was not determined by any prior event or set of events. Consider my decision to make a cheese omelet for breakfast this morning. The libertarian will say that my decision to make the cheese omelet was not free unless I could have chosen to do otherwise (given all the same initial conditions). But that means that nothing was determining my decision. But what kind of thing is a decision such that it causes my actions but is not itself caused by anything? We do not know of any other kind of thing like this in the universe. Rather, we think that any event or thing must have been caused by some (typically complex) set of conditions or events. Things don’t just pop into existence without being caused . That is as fundamental a principle as any we can think of. Philosophers have for centuries upheld the principle that “nothing comes from nothing.” They even have a fancy Latin phrase for it: ex nihilo nihil fir [1] . The problem is that my decision to make a cheese omelet seems to be just that: something that causes but is not itself caused. Indeed, as noted earlier, the libertarian Roderick Chisholm embraces this consequence of the libertarian position very clearly when he claimed that when we exercise our free will,

“we have a prerogative which some would attribute only to God: each of us, when we really act, is a prime mover unmoved. In doing what we do, we cause certain events to happen, and nothing and no one, except we ourselves, causes us to cause those events to happen” (Chisholm, 1964).

How could something like this exist? At this point the libertarian might respond something like this:

I am not claiming that something comes from nothing; I am just claiming that our decisions are not themselves determined by any prior thing. Rather, we ourselves, as agents, cause our decisions and nothing else causes us to cause those decisions (at least in cases where we have acted freely).

However, it seems that the libertarian in this case has simply pushed the mystery back one step: we cause our decisions, granted, but what causes us to make those decisions? The libertarian’s answer here is that nothing causes us. But now we have the same problem again: the agent is responsible for causing the decision but nothing causes the agent to make that decision. Thus we seem to have something coming from nothing. Let’s call this argument the argument from mysterious causes. Here’s the argument in standard form:

- The existence of free will implies that when an agent freely decides to do something, the agent’s choice is not caused (determined) by anything.

- To say that something has no cause is to violate the ex nihilo nihil fit principle.

- But nothing can violate the ex nihilo nihil fit principle.

- Therefore, there is no free will (from 1-3)

The hard determinist will make a strong case for premise 3 in the above argument by invoking basic scientific principles such as the law of conservation of energy, which says that the amount of energy within a closed system stays that same. That is, energy cannot be created or destroyed. Consider a billiard ball. If it is to move then it must get the required energy to do so from someplace else (typically another billiard ball knocking into it, the cue stick hitting it or someone tilting the pool table). To allow that something could occur without any cause—in this case, the agent’s decision—would be a violation of the conservation of energy principle, which is as basic a scientific principle as we know. When forced to choose between uphold such a basic scientific principle as this and believing in free will, the hard determinist opts for the former. The hard determinist will put the ball in the libertarian’s court to explain how something could come from nothing.

I will close this section by indicating how these problems in philosophy often ramify into other areas of philosophy. In the first place, there is a fairly common way that libertarians respond to the charge that their view violates basic principles such as ex nihilo nihil fit and, more specifically, the physical law of conservation of energy. Libertarians could claim that the mind is not physical—a position known in the philosophy of mind as “substance dualism” (see philosophy of mind chapter in this textbook for more on substance dualism). If the mind isn’t physical, then neither are our mental events, such our decisions.

Rather, all of these things are nonphysical entities. If decisions are nonphysical entities, there is at least no violation of the physical laws such as the law of conservation of energy. [2] Of course, if the libertarian were to take this route of defending her position, she would then need to defend this further assumption (no small task). In any case, my main point here is to see the way that responses to the problem of free well and determinism may connect with other issue within philosophy. In this case, the libertarian’s defense of free will may turn out to depend on the defensibility of other assumptions they make about the nature of the mind. But the libertarian is not the only one who will need to ultimately connect her account of free will up with other issues in philosophy. Since hard determinists deny that free will exists, it seems that they will owe us some account of moral responsibility. If, moral responsibility requires that humans have free will (see previous section), then in denying free will we seem to also be denying that humans have moral responsibility. Thus, hard determinists will face the objection that in rejecting free will they also destroy moral responsibility.

But since it seems we must hold individuals morally to account for certain actions (such as the embezzler from the previous section), the hard determinist

needs some account of how it makes sense to do this given that human being don’t have free will. My point here is not to broach the issue of how the hard determinist might answer this, but simply to show how hard determinist’s position on the problem of free will and determinism must ultimately connect with other issues in philosophy, such issues in metaethics [3] . This is a common thing that happens in philosophy. We may try to consider an issue or problem in isolation, but sooner or later that problem will connect up with other issues in philosophy.

Compatibilism

The best argument for compatibilism builds on a consideration of the difficulties with the incompatibilist definition of free will (which both the libertarian and the hard determinist accept). As defined above, compatibilists agree with the hard determinists that determinism is true, but reject the incompatibilist definition of free will that hard determinists accept. This allows compatbilists to claim that free will is compatible with determinism. Both libertarians and hard compatibilists tend to feel that this is somehow cheating, but the compatibilist attempts to convince us arguing that the strong incompatibilist definition of freedom is problematic and that only the weaker compatibilist definition of freedom—free actions are voluntary actions—will work. We will consider two objections that the compatibilist raises for the incompatibilist definition of freedom: the epistemic objection and the arbitrariness objection . Then we will consider the compatibilist’s own definition of free will and show how that definition fits better with some of our common sense intuitions about the nature of free actions.

The epistemic objection is that there is no way for us to ever know whether any one of our actions was free or not. Recall that the incompatibilist definition of freedom says that a decision is free if and only if I could have chosen otherwise than I in fact chose, given exactly all the same conditions. This means that if we were, so to speak, rewind the tape of time and be given that decision to make over again, we could have chosen differently. So suppose the question is whether my decision to make a cheese omelet for breakfast was free. To answer this question, we would have to know when I could have chosen differently. But how am I supposed to know that ? It seems that I would have to answer a question about a strange counterfactual : if given that decision to make over again, would I choose the same way every time or not? How on earth am I supposed to know how to answer that question? I could say that it seems to me that I could make a different decision regarding making the cheese omelet (for example, I could have decided to eat cereal instead), but why should I think that that is the right answer? After all, how things seem regularly turn out to be not the case—especially in science. The problem is that I don’t seem to have any good way of answering this counterfactual question of what I would choose if given the same decision to make over again. Thus the epistemic objection [4] is that since I have no way of knowing whether I would/wouldn’t make the same decision again, I can never know whether any of my actions are free.

The arbitrariness objection is that it turns our free actions into arbitrary actions. And arbitrary actions are not free actions. To see why, consider that if the incompatibilist definition is true, then nothing determines our free choices, not even our own desires . For if our desires were determining our choices then if we were to rewind the tape of time and, so to speak, reset everything— including our desires —the same way, then given those same desires we would choose the same way every time. And that would mean our choice was not free, according to the incompatbilist. It is imperative to remember that incompatibilism says that if an action is not free if it is determined ( including if it is determined by our own desires ). But now the question is: if my desires are not causing my decision, what is? When I make a decision, where does that decision come from, if not from my desires and beliefs? Presumably it cannot come from nothing ( ex nihilo nihil fit ). The problem is that if the incompatibilist rejects that anything is causing my decisions, then how can my decisions be anything but arbitrary?

Presumably an arbitrary decision—a decision not driven by any reason at all—is not an exercise of my freedom. Freedom seems to require that we are exercising some kind of control over my actions and decisions. If my action or decision is arbitrary that means that no reason or explanation of the action/decision can be given. Here’s the arbitrariness objection cast as a reductio ad absurdum argument:

- A free choice is one that isn’t determined by anything, including our desires. [incompatibilist definition of freedom]

- If our own desires are not determining our choices, then those choices are arbitrary.

- If a choice is arbitrary then it is not something over which we have control

- If a choice isn’t something over which we have control, then it isn’t a free choice

- Therefore, a free choice is not a free choice (from 1-4)

A reductio ad absurdum argument is one that starts with a certain assumption and then derives a contradiction from that assumption, thereby showing that assumption must be false. In this case, the incompatibilist’s definition of a free choice leads to the contradiction that something that is a free choice isn’t a free choice.

What has gone wrong here? The compatibilist will claim that what has gone wrong is incompatibilist’s idea that a free action must be one that isn’t caused/determined by anything. The compatibilist claims that free actions can still be determined, as long as what is determining them is our own internal reasons, over which we have some control, rather than external things over which we have no control. Free choices, according to the compatibilist, are just choices that are caused by our own best reasons . The fact that, given the exact same choices, I couldn’t have chosen otherwise doesn’t undermine what freedom is (as the incompatibilist claims) but defines what it is. Consider an example. Suppose that my goal is to spend the shortest amount of time on my commute home from work so that I can be on time for a dinner date. Also suppose, for simplicity, that there are only three possible routes that I can take: route 1 is the shortest, whereas route 2 is longer but scenic and 3 is more direct but has potentially more traffic, especially during rush hour. I am leaving early from work today so that I can make my dinner date but before I leave, I check the traffic and learn that there has been a wreck on route 1. Thus, I must choose between routes 2 and 3. I reason that since I am leaving earlier, route 3 will be the quickest since there won’t be much traffic while I’m on my early commute home. So I take route 3 and arrive home in a timely manner: mission accomplished. The compatibilist would say that this is a paradigm case of a free action (or a series of free actions). The decisions I made about how to get home were drive both by my desire to get home quickly and also by the information I was operating with. Assuming that that information was good and I reasoned well with it and was thereby able to accomplish my goal (that is, get home in a timely manner), then my action is free. My action is free not because my choices were undetermined, but rather because my choices were determined (caused) by my own best reasons—that is, by my desires and informed beliefs. The incompatibilist, in contrast, would say that an action is free only if I could have chosen otherwise, given all the same conditions again. But think of what that would mean in the case above! Why on earth would I choose routes 1 or 2 in the above scenario, given that my most pressing goal is to be able to get to my dinner date on time? Why would anyone knowingly choose to do something that thwarts their primary goals? It doesn’t seem that, given the set of beliefs and desires that I actually had at the time, I could have chosen otherwise in that situation. Of course, if you change the information I had (my beliefs) or you change what I wanted to accomplish (my desires), then of course I could have acted otherwise than I did. If I didn’t have anything pressing to do when I left work and wanted a scenic and leisurely drive home in my new convertible, then I probably would have taken route 2! But that isn’t what the incompatibilist requires for free will. As we’ve seen, they require the much stronger condition that one’s action be such that it could have been different even if they faced exactly the same condition over again. But in this scenario that would be an irrational thing to do. Of course, if one’s goal were to be irrational and to thwart one’s own desires, I suppose they could do that. But that would still seem to be acting in accordance with one’s desires.

Many times free will is treated as an all or nothing thing, either humans have it or they don’t. This seems to be exactly how the libertarian and hard determinist see the matter. And that makes sense given that they are both incompatibilists and view free will and determinism like oil and water—they don’t mix. But it is interesting to note that it is common for us to talk about decisions, action, or even whole lives (or periods of a life) as being more or less free . Consider the Goethe quotation at the beginning of this chapter: “none are more enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.” Here Goethe is conceiving of freedom as coming in degrees and claiming that those who think they are free but aren’t as less free than those who aren’t free and know it. But this way of speaking implies that free will and determinism are actually on a continuum rather than a black and white either or. The compatibilist can build this fact about our ordinary ways of speaking about freedom into an argument for their position. Call this the argument from ordinary language . The argument from ordinary language is that only compatibilism is able to accommodate our common way of speaking about freedom coming in degrees—that is, as actions or decisions being more or less free. The libertarian can’t account for this since the libertarian sees freedom as an all or nothing matter: if you couldn’t have done otherwise then your action was not truly free; if you could have done otherwise, then it was. In contrast, the compatibilist is able to explain the difference between more/less free action on the continuum. For the compatibilist, the freest actions are those in which one reasons well with the best information, thus acting for one’s own best reasons, thus furthering one’s interests. The least free actions are those in which one lacks information and reason poorly, thus not acting for one’s own best reasons, thus not furthering one’s interests. Since reasoning well, being informed, and being reflective are all things that come in degrees (since one can possess these traits to a greater or lesser extent) and since these attribute define what free will is for the compatibilist, it follows that free will comes in degrees. And that means that the compatibilist is able to make sense or a very common way that we talk about freedom (as coming in degrees) and thus make sense of ourselves, whereas the libertarian isn’t.

There’s one further advantage that compatibilists can claim over libertarians. Libertarians defend the claim that there are at least some cases where one exercises one’s free will and that this entails that determinism is false. However, this leaves totally open the extent of human free will. Even if it were true that there are at least some cases where humans exercise free will, there might not be very many instances and/or those decisions in which we exercise free will might be fairly trivial (for example, moving one’s finger to the left or right). But if it were to turn out that free will was relatively rare, then even if the libertarian were correct that there are at least some instances where we exercise free will, it would be cold comfort to those who believe in free will. Imagine: if there were only a handful of cases in your life where your decision was an exercise of your free will, then it doesn’t seem like you have lived a life which was very free. In other words, in such a case, for all practical purposes, determinism would be true.

Thus, it seems like the question of how widespread free will is is an important one. However, the libertarian seems unable to answer it for reasons that we’ve already seen. Answering the question requires knowing whether or not one could have acted otherwise than one in fact did. But in order to know this, we’d have to know how to answer a strange counterfactual—whether I could have acted differently given all the same conditions. As noted earlier (“the epistemic objection”), this raises a tough epistemological question for the libertarian: how could he ever know how to answer this question? And so how could he ever know whether a particular action was free or not? In contrast, the compatibilist can easily answer the question of how widespread free will is: how “free” one’s life is depends on the extent to which one’s actions are driven by their own best reasons. And this, in turn, depends on factors such as how well-informed, reflective, and reasonable a person is. This might not always be easy to determine, but it seems more tractable than trying to figure out the truth conditions of the libertarian’s counterfactual.

In short, it seems that compatibilism has significant advantages over both libertarianism and hard determinism. As compared to the libertarian, compatibilism gives a better answer to how free will can come in degrees as well as how widespread free will is. It also doesn’t face the arbitrariness objection or the epistemic objection. As compared to the hard determinist, the compatibilist is able to give a more satisfying answer to the moral responsibility issue. Unlike the hard determinist, who sees all action as equally determined (and so not under our control), the compatibilist thinks there is an important distinction within the class of human actions: those that are under our control versus those that aren’t. As we’ve seen above, the compatibilist doesn’t see this distinction as black and white, but, rather, as existing on a continuum. However, a vague boundary is still a boundary. That is, for the compatibilist there are still paradigm cases in which a person has acted freely and thus should be held morally responsible for that action (for example, the person who embezzles money from a charity and then covers it up) and clear cases in which a person hasn’t acted freely (for example, the person who was told to do something by their boss but didn’t know that it was actually something illegal). The compatibilist’s point is that this distinction between free and unfree actions matters, both morally and legally, and that we would be unwise to simply jettison this distinction, as the hard determinist does. We do need some distinction within the class of human actions between those for which we hold people responsible and those for which we don’t. The compatibilist’s claim is that they are able to do with while the hard determinist isn’t. And they’re able to do it without inheriting any of the problems of the libertarian position.

Study questions

- True or false: Compatibilists and libertarians agree on what free will is (on the concept of free will).

- True or false: Hard determinists and libertarians agree that an action is free only when I could have chosen otherwise than I in fact chose.

- True or false: the libertarian gives a transcendental argument for why we must have free will.

- True or false: both compatibilists and hard determinists believe that all human actions are determined.

- True or false: compatibilists see free will as an all or nothing matter: either an action is free or it isn’t; there’s no middle ground.

- True or false: compatibilists think that in the case of a truly free action, I could have chosen otherwise than I in fact did choose.

- True or false: One objection to libertarianism is that on that view it is difficult to know when a particular action was free.

- True or false: determinism is a fundamental assumption of the natural sciences (physics, chemistry, biology, and so on).

- True or false: the best that support the libertarian’s position are cases of very simple or arbitrary actions, such as choosing to move my finger to the left or to the right.

- True or false: libertarians thinks that as long as my choices are caused by my desires, I have chosen freely.

For deeper thought

- Consider the Shopenhauer quotation at the beginning of the chapter. Which of the three views do you think this supports and why?

- Consider the movie The Truman Show . How would the libertarian and compatibilist disagree regarding whether or not Truman has free will?

- Consider the Tolstoy quote at the beginning of the chapter. Which of the three views does this support and why?

- Consider a child being raised by white supremacist parents who grows up to have white supremacist views and to act on those views. As a child, does this individual have free will? As an adult, do they have free will? Defend your answer with reference to one of the three views.

- Consider the eccentric neuroscientist example (above). How might a compatibilist try to show that this isn’t really an objection to her view? That is, how might the compatibilist show that this is not a case in which the individual’s action is the result of a well-informed, reflective choice?

- Actually, the phrase was originally a Latin phrase, not an English one because at the time in Medieval Europe philosophers wrote in Latin. ↵

- On the other hand, if these nonphysical decisions are supposed to have physical effects in the world (such as causing our behaviors) then although there is no problem with the agent’s decision itself being uncaused, there would still be a problem with how that decision can be translated into the physical world without violating the law of conservation of energy. ↵

- One well-known and influential attempt to reconcile moral responsibility with determinism is P.F. Strawson’s “Freedom and Resentment” (1962). ↵

- The term “epistemic” just denotes something relating to knowledge. It comes from the Greek work episteme, which means knowledge or belief. ↵

Introduction to Philosophy Copyright © by Matthew Van Cleave is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with MIND?

- About The Mind Association

- Editorial Board and Other Officers

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Determinism, freedom, and moral responsibility: essays in ancient philosophy , by susanne bobzien.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Brad Inwood, Determinism, Freedom, and Moral Responsibility: Essays in Ancient Philosophy , by Susanne Bobzien, Mind , 2022;, fzac007, https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzac007

- Permissions Icon Permissions

It is the separability of an incorporeal soul from the body that brings the theories and debates on freedom to a new level. Aristotle’s hylomorphism and Epicurean and Stoic materialism do not permit a human soul to survive the destruction or demise of the human body. This is not so with Platonist and Christian philosophy.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Editorial Board

- Contact The Mind Association

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2113

- Print ISSN 0026-4423

- Copyright © 2024 Mind Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Freedom and Determinism

Joseph Keim Campbell, Michael O'Rourke, and David Shier (eds.), Freedom and Determinism , MIT Press, 2004, 352pp, $35.00 (pbk), ISBN 0262532573.

Reviewed by Eddy Nahmias, Georgia State University

The free will debate has taken off in recent decades, driven largely by Peter van Inwagen's revitalization of incompatibilism, Harry Frankfurt's ammunition for compatibilism, interesting libertarian theories, and well-developed compatibilist theories. In the last few years this work has been collected into numerous volumes. [1] The latest is Freedom and Determinism , edited by Joseph Keim Campbell, Michael O'Rourke, and David Shier, and drawn from papers presented at the 2001 meeting of the Inland Northwest Philosophy Conference. [2]

This volume offers five essays in which well-known philosophers in the field offer reviews of their positions, along with nine essays that offer interesting new arguments (see below). There is not too much overlap in content with the other recent collections on free will, and many of the important positions and arguments in the current debates are covered, with the notable exceptions of agent-causation theories and recent skeptical positions about the existence of free will and moral responsibility. [3] Unfortunately, however, the book is not ideal for either of its two potential markets. Many of its selections are too narrow and technical for non-specialists (including most students) who want an introduction to the contemporary debates. And for more advanced audiences, most of its review pieces cover familiar ground, limiting the book's primary appeal to the new work, some of which is tangential to the more central debates. Having said this, there is still much to offer both of these audiences, and several essays are indispensable for philosophers engaged in the free will debate, including a few that discuss tangential issues that should be more central to the traditional debates.

The volume's essays can be categorized in two ways: review essays vs. essays presenting new arguments, and (more reviewer-relative) "must-read" essays vs. "optional" essays. After I summarize and occasionally critique the essays below, I label them according to these categories:

R = primarily review of author's previous work

N = primarily new discussion

ME = must-read for expert in free will debate

MS = must-read for student (or other non-specialist)

OE = optional-read for expert

OS = optional-read for student

I hope this exercise will help this review serve what I take to be one of its intended purposes -- to inform potential readers whether they will want to get the book, and if so, which parts of it to spend their valuable time reading. [4]

Introduction, "Freedom and Determinism: A Framework," by Campbell, O'Rourke, and Shier:

This chapter does an excellent job of describing the central debates and positions in the literature and then providing useful summaries of the fourteen chapters that follow. The authors define various conceptions of freedom, offer five central questions in the debate, and introduce van Inwagen's Consequence argument (and its unavoidability operator Beta ) and Frankfurt cases. My only qualm is with their stipulation that the concept "free will" refer to having alternatives for action (3). [ME, MS]

1) "Determinism: What We Have Learned and What We Still Don't Know" by John Earman:

Earman offers a very technical review of his work on the status of determinism in modern physics. For those who are not proficient in the philosophy of physics, this chapter is not accessible. This is unfortunate since Earman makes several significant points philosophers often overlook regarding the thesis of determinism. He explains why "there is no simple and clean answer" to the question "If we believe modern physics, is the world deterministic or not?" (43). It has yet to be "determined" whether the best interpretation of quantum mechanics will be consistent with determinism. [5] I take this conclusion to bolster the claim that whether humans are (and have ever been) free and responsible should not be "held hostage" to future discoveries by physicists (see Fischer on p. 197). But now I've gone and exposed my compatibilist tendencies! While I'm at it, Earman also explains why determinism does not entail predictability, undermining what I take to be one of the intuitive sources for the thought that determinism precludes free will (i.e., that it would make us predictable and manipulable). [R, OE, OS]

2) "Freedom and the Power of Preference" by Keith Lehrer:

Lehrer's essay reviews his impressive compatibilist theory developed in Metamind (1990), based on the idea that free action is action performed in accord with one's preferences (including one's "ultrapreference" to reason about one's preferences in ways one prefers). Preferences, unlike desires, are not passive and are subject to evaluation. Here, Lehrer adds the condition that free agents must have the preference structure they have because they prefer to have it. This condition aims to avoid manipulation counterexamples in which agents have their preference structure only because another agent creates it in them. In typical compatibilist fashion, Lehrer accepts that one's preference structure can be free though fully caused but not if it is caused in certain ways (e.g., by manipulation), and he also offers a conditional analysis of being able to prefer otherwise. Finally, he offers responses to the Consequence argument, pointing out (accurately) that the argument depends heavily on one's understanding of ability and of laws of nature: "If one builds incompatibility with freedom into the definition of laws by defining the latter in such terms, then incompatibility will be the result" (68). Incompatibilists will be skeptical of these responses, as well as Lehrer's attempt to invoke "mutual causal support and dependency" (57) to address concerns about infinite regresses of preferences. Nonetheless, they will have to work to develop these objections, as Lehrer's essay offers the most plausible, comprehensive defense of a compatibilist theory in this volume. [R, ME, MS]

3) "Agency, Responsibility, and Indeterminism: Reflections on Libertarian Theories of Free Will" by Robert Kane:

Kane, meanwhile, offers the volume's only comprehensive defense of a libertarian theory of free will. His view will be familiar to anyone who has read his outstanding book, The Significance of Free Will (1996), or his more recent defenses of it. While there is nothing new in this essay, for those unfamiliar with his work, it helpfully presents Kane's views on why, rather than just alternative possibilities (AP), "UR [ultimate responsibility] should be moved to center stage in free will debates" (74), and why indeterminism in decision-making need not undermine control. As usual, Kane succeeds in showing why event-causal libertarianism is no worse than compatibilist theories but fails in showing why it is any better (at least in grounding moral responsibility). And as usual, he does so in clear and eminently readable prose. [R, OE, MS]

4) "Trying to Act" by Carl Ginet:

Ginet's essay is less lucid. It is filled with variables and complex examples used to develop a detailed analysis of four disjunctive sufficient conditions for an agent's trying to act. For specialists interested in this question, the essay will be illuminating. But Ginet does not explain how his analysis connects with questions of freedom or moral responsibility (including his own incompatibilist arguments), so it seems out of place in this volume. And it will be inaccessible to most non-specialists. [N, OE, OS]

5) "The Sense of Freedom" by Dana Nelkin:

Nelkin addresses a topic too often neglected in free will debates, the nature of rational deliberation and its connection to the belief in freedom. She argues that rational deliberators necessarily have a sense that they are free and argues that this sense of freedom does not entail a belief in indeterminism but rather a belief that one's actions are up to oneself such that one is accountable for them, where this belief derives from seeing oneself as responsive to reasons. Deliberation requires a belief that one can typically succeed in reaching a decision and implementing it, so in this sense one must believe one has the ability to act on one's deliberations, though this does not commit one to a belief that each of one's alternatives for action are undetermined by prior conditions. Nelkin's conclusion challenges libertarians who claim that our experience of deliberation manifests a belief in indeterminism, and it offers the first step in an antiskeptical argument that uses our sense of freedom to show that we actually are free. [N, ME, OS]

6) "Libertarian Openness, Blameworthiness, and Time" by Ishtiyaque Haji:

Like Nelkin, Haji addresses a neglected but important issue, whether responsibility must be backwards-looking. He challenges the traditional thesis ("blame past") that an agent can only be blamed for an action after he has performed it, a thesis that is supported by the intuitive idea that an agent cannot be blamed for an action (or its consequences) unless he can do otherwise, and if he can do otherwise, one cannot know what he will do until he has in fact done it. Haji shrewdly applies Frankfurt cases to this idea to develop a case where one can know that an agent will kill before he does, suggesting that it is appropriate to blame the agent before he has done anything wrong. Though the complexity of Haji's cases may be confusing me, it seems that they only show that one can blame someone for making a decision before he actually carries it out and only if there are conditions that ensure the decision will be acted on. But libertarians could concede this point and maintain that an agent cannot be blamed for a (free) decision until it has been made. And for reasons familiar to Frankfurt-case devotees, the debate will then turn to whether Frankfurt cases can cut off all undetermined robust alternatives so as to suggest that an agent can be blameworthy without having an alternative decision available. Haji's note 7 (p. 148) suggests that his cases will be less effective against libertarians (e.g., Kane and van Inwagen) who emphasize the importance of an agent's indecisiveness for free actions (an emphasis that I take to weaken the plausibility of libertarianism). I think that the final section of Haji's essay is more interesting than the technical discussion that precedes it. There he points out that different conceptions of moral responsibility influence one's view of the temporal questions and suggests that his own "self-disclosure" view does not entail "blame past" since an agent can disclose what she morally stands for before she acts on it. [N, ME, OS]

7) "Moderate Reasons-responsiveness, Moral Responsibility, and Manipulation" by Todd Long:

Long brings the issue of manipulation into the discussion, an issue I believe is taking center stage in the free will debate since one of the strongest remaining arguments for incompatibilism is that there is no principled way to distinguish between an agent who satisfies compatibilist conditions because she was causally determined to do so and an agent who satisfies the same conditions because she was manipulated by another agent to do so. Long uses this point in the context of a Frankfurt case to put pressure on Fischer and Ravizza's reasons-responsive (RR) compatibilist theory. Long suggests that the same RR mechanism can issue in the same decision in both the non-manipulated (actual) branch of a Frankfurt case and in the manipulated (counterfactual) branch, because the manipulator can drive the desired decision by changing the inputs (e.g., reasons) to the RR mechanism rather than by bypassing the RR mechanism and using a process that is not RR. Long thinks this forces Fischer and Ravizza either to supplement their theory by explaining the difference between the two branches or to accept that an agent who acts on an RR mechanism can be responsible even if severely manipulated. Like Haji, Long uses Frankfurt cases in a creative and illuminating way. I think he is right to conclude that his case need not undermine this compatibilist account but that it does force compatibilists to deal with manipulation cases. And I think they can do so. They can begin by pointing out that manipulation by a goal-directed agent cuts off alternatives that "blind" causal processes do not. A manipulator can adjust his manipulation however required to achieve his goals; natural causal processes do not have goals. So, for a determined agent, had things gone differently (and determinism does not preclude this since the past and laws are not necessary), the agent could act differently; whereas, for a manipulated agent, had things gone differently, the manipulator would find a way to make sure the agent did not act differently. At a minimum, this difference, I suspect, drives our intuitions that many types of manipulation are clearly freedom-compromising whereas our intuitions about determinism's relationship to free will are not so clear. [6] Another difference is that responsibility can be shared among agents so that a manipulator may (intuitively if not justifiably) "drain away" some, though perhaps not all, of the responsibility from the manipulated agent, though the latter may still be partially responsible (e.g., she may have developed beliefs and desires that take only minimal tinkering to issue -- through an RR mechanism -- in a blameworthy choice). Long's lucid essay effectively brings attention to these important issues. [N, ME, MS]

8) "Which Autonomy?" by Nomy Arpaly:

Arpaly's main point is that the concept of autonomy is used in too many ways to be functional as a label for the condition(s) required for agents to be morally responsible. I agree (I'd like us to use "free will" to label those conditions -- contra the editors' use of it). However, I think the concept of agent autonomy is the one on Arpaly's list most compatibilists are analyzing, though some think agent autonomy requires authenticity , and Arpaly, as she does in her other work, offers interesting literary counterexamples to the necessity of authenticity for responsibility. Though it would be a rhetorical mistake for compatibilists to use "autonomy" while giving "free will" to the incompatibilists, it would not be as confusing as Arpaly suggests so long as authors are clear about what they mean by "autonomy" and its precise relations to moral responsibility (as, for example, Al Mele is). Arpaly also worries that such accounts of autonomy are often too stringent to serve as viable conditions for attributing responsibility (e.g., 176), but this worry neglects the possibility that these accounts are -- or should be -- put in terms of capacities agents possess and exercise to varying degrees that map (perhaps imperfectly) onto the degree to which agents should be held accountable for their actions. Finally, Arpaly, like Long, draws attention to the problem of differentiating between manipulation and other causal histories, including ones like conversion that involve rapid and extreme changes in one's character and preference structure (183-4). This problem is significant, but again, I think it is not insurmountable. [N, OE, OS]

9) "The Transfer of Nonresponsibility" by John Martin Fischer:

Fischer's essay reviews his counterexamples to the "direct argument" for the incompatibility of determinism and moral responsibility, which employs a principle of transfer of nonresponsibility (e.g., if A is not responsible for p, and if p then q and A is not responsible for this fact, then A is not responsible for q). Fischer offers new responses to objections from Eleanor Stump and Michael McKenna that focus on the fact that his counterexamples require overdetermination or preemption, and he concludes that his argument can withstand these objections, at least enough to maintain what he accurately labels a "dialectical stalemate" (defined on 198-199). I think Fischer is right that, in the face of the numerous stalemates that litter the free will debate, the burden of proof is on the incompatibilist. Fischer puts this in terms of the attractions of compatibilism (e.g., it makes it more likely we are morally responsible). I would add that incompatibilist arguments have the burden because they rely on a conception of free will that makes more demanding metaphysical claims than compatibilist alternatives. [7] [R, OE, OS]

10) "Van Inwagen on Free Will" by Peter van Inwagen (of course!):

Van Inwagen, on the other hand, takes the dialectical complexity of the free will debate to suggest "mysterianism," the view that, while we obviously have free will, it seems incompatible with both determinism and indeterminism and hence impossible. So, it is a mystery how free will exists. Unlike Fischer, van Inwagen thinks it must (somehow) be that free will is compatible with in determinism since he thinks his Consequence argument succeeds in showing free will is incompatible with determinism. Beginning with the genesis of this argument, van Inwagen offers a comprehensive summary of four decades of van Inwagen's thoughts on free will. He proceeds through his "restrictivism" (the view that acts of free will are rare because they occur only when we make close-call decisions), his response to Frankfurt's assault on the necessity of alternative possibilities, his rethinking of principle Beta , and finally his mysterianism, including his concluding point that agent causation cannot help make sense of free will. It's a shame that "van Inwagen has thought little about free will in the last ten years" (222). He seems to take the view regarding most objections to his positions that he takes regarding Frankfurt cases, that "as far as he is concerned, his original arguments for this position are the only answer to these counter-arguments that was really needed" (222). But it would be helpful to see how he would respond to other impressive responses to the Consequence argument, since it remains the most influential argument for incompatibilism (I take the view that most other incompatibilist and skeptical arguments, such as Galen Strawson's, rely on the same basic premises and principles as the Consequence argument). For instance, it would be nice to see how van Inwagen would respond to the objections that John Perry advances in the subsequent chapter. [R, OE, MS]

11) "Compatibilist Options" by John Perry:

Perry's essay is, along with Lehrer's and Long's, the highlight of this volume. Perry offers important distinctions among various accounts of laws of nature and of abilities to set up his responses to the Consequence argument. These responses will not be convincing to most incompatibilists but they do convince me of two points: first, that the free will debate revolves largely around one's understanding of laws of nature -- and specifically, whether the laws are reductionistic or include laws regarding human choices -- as well as one's understanding of cognitive abilities (or capacities); and second, that the debate about the Consequence argument, including how to understand laws and abilities, illustrates further examples of Fischer's "dialectical stalemates." Perry distinguishes between strong and weak accounts of laws of nature. In contrast to the strong (necessitarian) account of laws, the weak account takes laws to be descriptions of true generalizations. This Humean view suggests that, contrary to a crucial premise in the Consequence argument, a determined agent is able to act otherwise in that if she did act otherwise, a law that describes her choice would be different. [8] Perry does not find this view attractive but takes another tack by distinguishing different accounts of ability. In contrast to the strong account, the weak account of ability says that an agent is able to perform an action even if it is "settled" that she will not perform it. [9] Though Perry does not put it quite this way, I take him to be distinguishing between general capacities agents have to perform types of actions (including making choices) and particular occasions on which agents exercise (or fail to exercise) those capacities to act in certain ways, and to be arguing that we have the freedom-relevant ability to act in ways we do not act as long as we possess the relevant capacities to do so at the time, even if it is settled (e.g., determined) that we will not exercise our capacities in that way on this particular occasion (see 245). Since I've always been dubious of the suggestion that determinism entails that "does not" implies "cannot" (248), Perry's argument convinces me. And it demands that incompatibilists be more explicit about what abilities they have in mind when they conclude from Consequence-style arguments that determinism entails that agents lack the ability to do otherwise. [N, ME, MS]

12) "Freedom and Contextualism" by Richard Feldman:

Feldman raises objections to John Hawthorne's exploratory application of contextualism to the free will debate. Though he raises important critiques of Hawthorne's account, I think Feldman does not explore some of the possibilities for contextualism in this debate or important neighboring ideas, such as Manuel Vargas' "revisionism." [10] Contextualism about freedom claims that the truth-value of a statement about free action (and presumably moral responsibility) depends on the context of the utterance of the statement. In ordinary contexts it may be true that a determined action is free even if the same action may not count as free in a philosophical context. Feldman ignores the "may" in these claims and argues that this position concedes too much to the incompatibilist. But a compatibilist contextualist need not concede the truth of incompatibilism in philosophical contexts but instead use contextualist ideas as an error theory to explain what contextual factors lead some people (e.g., some philosophers) to accept incompatibilist arguments when the context is "demanding," while most people (including these philosophers) continue to act in the "real world" with the belief that we are free and responsible despite being ignorant about whether we are determined or not. Feldman is certainly right that contextualism does not answer the question of why, within philosophical contexts, intuitions diverge about free will (as with knowledge), leading to those pesky "dialectical stalemates." [N, OE, OS]

13) "Buddhism and the Freedom of the Will: Pali and Mahayanist Responses" by Nicholas Gier and Paul Kjellberg:

The volume ends with two essays that, in my opinion, could have been excluded. Non-Western approaches to Western philosophical problems can be illuminating, including Buddhist approaches to free will. [11] But Gier and Kjellberg's essay tries to do too much, dealing with several different Buddhist perspectives on causation and the self in addition to freedom and responsibility. I think I understood enough to say that it looks as though Buddhists are either compatibilists or skeptics about free will. And I appreciated the authors' discussion of why our version of the free will problem arose in the Modern era in light of Descartes' fracturing the inner and outer worlds and Newtonian physics' painting causation as mechanistic, linear interactions. [N, OE, OS]

14) "After Compatibilism and Incompatibilism" by Ted Honderich:

Honderich's "rapid paper" (311) reads like a talk and offers a sketchy version of his expansive and interesting views on the free will problem. He is right that there are conflicting conceptions and intuitions about free will but too quick to suggest that this entails that philosophers aren't debating some generally shared concept or that his "attitudinism" thereby offers a satisfying resolution. He is also right that any solution to debates about freedom and responsibility will turn on (perhaps radical) responses to the thorny problems of consciousness and causation. But in this essay Honderich does not tell us much about what such responses might look like. [R, OE, OS]

Freedom and Determinism thus offers several useful outlines of influential arguments in the free will debates and several interesting responses to these arguments and new discussions of neglected topics that bear on them. Some chapters seem out of place or too sketchy. But most have something valuable to offer the expert, the novice, or both.

[1] From (roughly) most to least expertise required of the reader: The Oxford Handbook of Free Will , edited by Robert Kane (Oxford, 2002), Moral Responsibility and Alternative Possibilities , edited by David Widerker and Michael McKenna (Ashgate, 2003), Free Will, 2 nd edition , edited by Gary Watson (Oxford, 2003), Agency and Responsibility , edited by Ekstrom (Westview, 2001), and Free Will , edited by Robert Kane (Blackwell, 2002).

[2] The volume is not just a conference proceedings. The dozens of contributors to the conference were invited to submit their essays for review and revision, from which the volume's 14 chapters were selected.

[3] Such skepticism is the position that free will and moral responsibility do not exist (or are even impossible), as represented by philosophers such as Derk Pereboom and Galen Strawson (van Inwagen's chapter offers arguments that might lead one to skepticism). The volume also does not cover less active areas of the free will debate, such as logical fatalism or God's foreknowledge, nor does it address relevant work in the cognitive sciences.

[4] Another way to divide up the essays is according to whether they support an incompatibilist position (libertarian vs. skeptical) or a compatibilist position. In fact, only two essays support incompatibilism (both libertarian), Kane's and van Inwagen's (chapters 3 and 10). The others either support compatibilism (chapters 2, 5, 6, 9, and 11), do not deal with the compatibility question (chapters 1, 4, and 8) or are best read as neutral between the two positions (chapters 7, 12, 13, and 14).

[5] In fact, Earman argues for the surprising conclusion that classical Newtonian physics, but not quantum mechanics or special relativity, is inconsistent with determinism (23-28).

[6] For thoughts along these lines, see Gideon Yaffe's "Indoctrination, Coercion and Freedom of the Will," Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 67 (2003): 335-356. For discussion of prephilosophical intuitions about the determinism and free will, see Nahmias, Morris, Nadelhoffer, and Turner's "Is Incompatibilism Intuitive?," Philosophy and Phenomenological Research (forthcoming).

[7] See Nahmias et al. , "Is Incompatibilism Intuitive?" (forthcoming).

[8] Perry distinguishes his discussion from David Lewis' similar response by avoiding the need for Lewis' "local miracles." For a more detailed discussion of how a Humean conception of laws influences the compatibility question, see Helen Beebee and Al Mele's "Humean Compatibilism," Mind 111 (2002): 235-241.

[9] An agent's doing A at t is "settled" if there is some proposition (or set of propositions) P that is made true prior to t and P entails the proposition that the agent does A at t. Hence, determinism would entail that all human actions are settled in that a proposition P (describing the world at some time prior to any human actions and the laws of nature) entails any proposition describing a human action. Perry offers an important discussion of how to understand the idea of a proposition being "made true" (234-237).