337 Climate Change Research Topics & Examples

You will notice that there are many climate change research topics you can discuss. Our team has prepared this compilation of 185 ideas that you can use in your work.

📝 Key Points to Use to Write an Outstanding Climate Change Essay

🏆 best climate change title ideas & essay examples, 🥇 most interesting climate change topics to write about, 🎓 simple & easy research titles about climate change, 👍 good research topics about climate change, 🔍 interesting topics to write about climate change, ⭐ good essay topics on climate change, ❓ climate change essay questions.

A climate change essay is familiar to most students who learn biology, ecology, and politics. In order to write a great essay on climate change, you need to explore the topic in great detail and show your understanding of it.

This article will provide you with some key points that you could use in your paper to make it engaging and compelling.

First of all, explore the factors contributing to climate change. Most people know that climate change is associated with pollution, but it is essential to examine the bigger picture. Consider the following questions:

- What is the mechanism by which climate change occurs?

- How do the activities of large corporations contribute to climate change?

- Why is the issue of deforestation essential to climate change?

- How do people’s daily activities promote climate change?

Secondly, you can focus on solutions to the problems outlined above.

Climate change essay topics often provide recommendations on how individuals and corporations could reduce their environmental impact. These questions may help to guide you through this section:

- How can large corporations decrease the influence of their operations on the environment?

- Can you think of any examples of corporations who have successfully decreased their environmental footprint?

- What steps can people take to reduce pollution and waste as part of their daily routine?

- Do you believe that trends such as reforestation and renewable energy will help to stop climate change? Why or why not?

- Can climate change be reversed at all, or is it an inescapable trend?

In connection with these topics, you could also discuss various government policies to address climate change. Over the past decades, many countries enacted laws to reduce environmental damage. There are plenty of ideas that you could address here:

- What are some famous national policies for environmental protection?

- Are laws and regulations effective in protecting the environment? Why or why not?

- How do environmentally-friendly policies affect individuals and businesses?

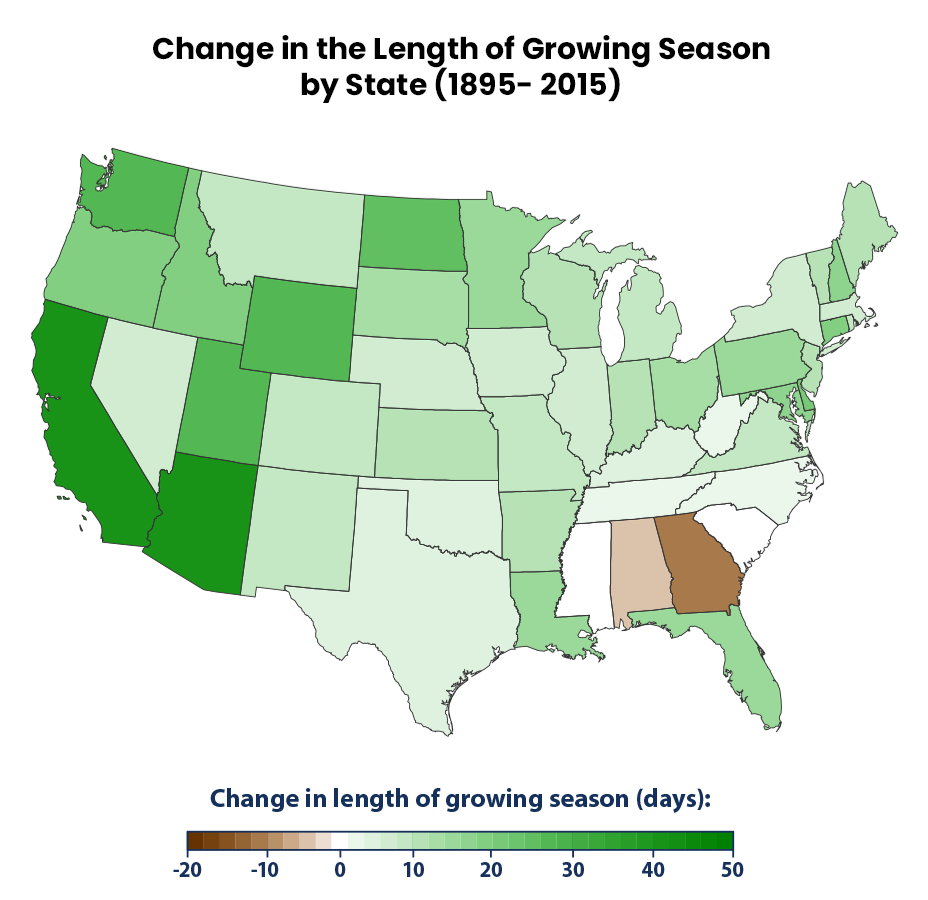

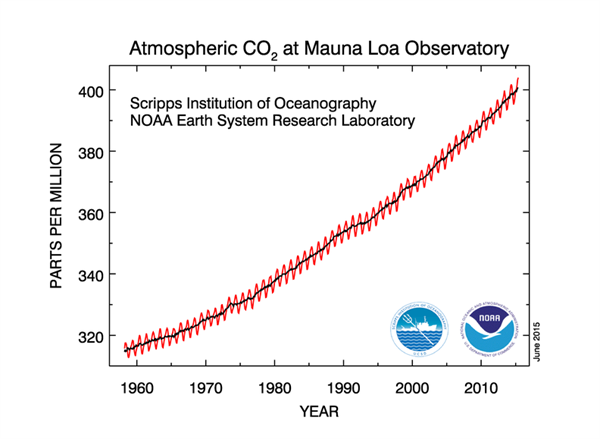

- Are there any climate change graphs that show the effectiveness of national policies for reducing environmental damage?

- How could government policies on climate change be improved?

Despite the fact that there is definite proof of climate change, the concept is opposed by certain politicians, business persons, and even scientists.

You could address the opposition to climate change in your essay and consider the following:

- Why do some people think that climate change is not real?

- What is the ultimate proof of climate change?

- Why is it beneficial for politicians and business persons to argue against climate change?

- Do you think that climate change is a real issue? Why or why not?

The impact of ecological damage on people, animals, and plants is the focus of most essay titles on global warming and climate change. Indeed, describing climate change effects in detail could earn you some extra marks. Use scholarly resources to research these climate change essay questions:

- How has climate change impacted wildlife already?

- If climate change advances at the same pace, what will be the consequences for people?

- Besides climate change, what are the impacts of water and air pollution? What does the recent United Nations’ report on climate change say about its effects?

- In your opinion, could climate change lead to the end of life on Earth? Why or why not?

Covering at least some of the points discussed in this post will help you write an excellent climate change paper! Don’t forget to search our website for more useful materials, including a climate change essay outline, sample papers, and much more!

- Climate Change – Problems and Solutions It is important to avoid cutting trees and reduce the utilization of energy to protect the environment. Many organizations have been developed to enhance innovation and technology in the innovation of eco-friendly machines.

- Causes and Effects of Climate Changes Climate change is the transformation in the distribution patterns of weather or changes in average weather conditions of a place or the whole world over long periods.

- Is Climate Change a Real Threat? Climate change is a threat, but its impact is not as critical as wrong political decisions, poor social support, and unstable economics.

- Global Warming as Serious Threat to Humanity One of the most critical aspects of global warming is the inability of populations to predict, manage, and decrease natural disruptions due to their inconsistency and poor cooperation between available resources.

- Climate Change Causes and Predictions These changes are as a result of the changes in the factors which determine the amount of sunlight that gets to the earth surface.

- The Role of Technology in Climate Change The latter is people’s addiction, obsession, and ingenuity when it comes to technology, which was the main cause of climate change and will be the primary solution to it as well.

- Climate Change and Its Impacts on the UAE Currently, the rise in temperature in the Arctic is contributing to the melting of the ice sheets. The long-range weather forecast indicates that the majority of the coastal areas in the UAE are at the […]

- The Role of Science and Technology in International Relations Regarding Climate Change This paper examines the role of science and technology as it has been used to address the challenge of climate change, which is one of the major issues affecting the global societies today.

- Climate Change: Human Impact on the Environment This paper is an in-depth exploration of the effects that human activities have had on the environment, and the way the same is captured in the movie, The Eleventh Hour.

- Climate Change and Extreme Weather Conditions The agreement across the board is that human activities such as emissions of the greenhouse gases have contributed to global warming.

- Climate Change: Mitigation Strategies To address the latter views, the current essay will show that the temperature issue exists and poses a serious threat to the planet.

- Global Warming and Human Impact: Pros and Cons These points include the movement of gases in the atmosphere as a result of certain human activities, the increase of the temperature because of greenhouse gas emissions, and the rise of the oceans’ level that […]

- Climate Change – Global Warming For instance, in the last one century, scientists have directly linked the concentration of these gases in the atmosphere with the increase in temperature of the earth.

- Climate Change Needs Human Behavior Change The thesis of this essay is that human behavior change, including in diet and food production, must be undertaken to minimize climate change, and resulting misery.

- Climate Change for Australian Magpie-Lark Birds Observations in the northern parts of Australia indicate that Magpie-lark birds move to the coast during the dry season and return back during the wet season.

- Climate Change’s Negative Impact on Biodiversity This essay’s primary objective is to trace and evaluate the impact of climate change on biological diversity through the lens of transformations in the marine and forest ecosystems and evaluation of the agricultural sector both […]

- Climate Change and Role of Government He considers that the forest’s preservation is vital, as it is the wellspring of our human well-being. As such, the legislature can pass policies that would contribute to safeguarding our nation’s well-being, but they do […]

- The Impact of Climate Change on Food Security Currently, the world is beginning to encounter the effects of the continuous warming of the Earth. Some of the heat must be reflected in space to ensure that there is a temperature balance in the […]

- Climate Change Impacts on Ocean Life The destruction of the ozone layer has led to the exposure of the earth to harmful radiation from the sun. The rising temperatures in the oceans hinder the upward flow of nutrients from the seabed […]

- Technology Influence on Climate Change Undoubtedly, global warming is a portrayal of climate change in the modern world and hence the need for appropriate interventions to foster the sustainability of the environment.

- Climate Change Impact on Bangladesh Today, there are a lot of scientists from the fields of ecology and meteorology who are monitoring the changes of climate in various regions of the world.

- Climate Change, Development and Disaster Risk Reduction However, the increased cases of droughts, storms, and very high rainfalls in different places are indicative of the culmination of the effects of climate change, and major disasters are yet to follow in the future.

- The Climate Change Articles Comparison In a broader sense, both articles address the concept of sustainability and the means of reinforcing its significance in the context of modern global society to prevent further deterioration of the environment from happening.

- Global Warming and Climate Change: Annotated Bibliography The author shows the tragedy of the situation with climate change by the example of birds that arrived too early from the South, as the buds begin to bloom, although it is still icy.

- Starbucks: Corporate Social Responsibility and Global Climate Change Then in the 90s and onwards to the 21st century, Starbucks coffee can be seen almost anywhere and in places where one least expects to see a Starbucks store.

- Climate Change Impacts on the Aviation Industry The last two research questions focus on investigating the challenges experienced by stakeholders in the aviation industry in reducing the carbon blueprint of the sector and discussing additional steps the aviation industry can take to […]

- Climate Change: The Complex Issue of Global Warming By definition, the greenhouse effect is the process through which the atmosphere absorbs infrared radiation emitted from the Earth’s surface once it is heated directly by the sun during the day.

- Global Climate Change and Environmental Conservation There may be a significantly lesser possibility that skeptics will acknowledge the facts and implications of climate change, which may result in a lower desire on their part to adopt adaptation. The climate of Minnesota […]

- Climate Change’s Impact on Crop Production I will address the inefficiencies of water use in our food production systems, food waste, and the impact of temperature on crop yield.

- Climate Change: The Day After Tomorrow In the beginning of the film “The Day After Tomorrow”, the main character, Professor Jack Hall, is trying to warn the world of the drastic consequences of a changing climate being caused by the polluting […]

- Climate Change and Renewable Energy Options The existence of various classes of world economies in the rural setting and the rise of the middle class economies has put more pressure on environmental services that are highly demanded and the use of […]

- Climate Change Definition and Description The wind patterns, the temperature and the amount of rainfall are used to determine the changes in temperature. Usually, the atmosphere changes in a way that the energy of the sun absorbed by the atmosphere […]

- Transportation Impact on Climate Change It is apparent that the number of motor vehicles in the world is increasing by the day, and this translates to an increase in the amount of pollutants produced by the transportation industry annually.

- Maize Production and Climate Change in South Africa Maize farming covers 58% of the crop area in South Africa and 60% of this is in drier areas of the country.

- Climate Change and Its Effects on Tourism in Coastal Areas It is hereby recommended that governments have a huge role to play in mitigating the negative effects of climate change on coastal towns.

- Global Warming: Justing Gillis Discussing Studies on Climate Change Over the years, environmental scientists have been heavily involved in research regarding the changes in climate conditions and effects that these changes have on the environment.

- The Global Warming Problem and Solution Therefore, it is essential to make radical decisions, first of all, to reduce the use of fossil fuels such as oil, carbon, and natural gas. One of the ways of struggle is to protest in […]

- Climate Change and Threat to Animals In the coming years, the increase in the global temperatures will make many living populations less able to adapt to the emergent conditions or to migrate to other regions that are suitable for their survival.

- Climate Change in Communication Moreover, environmental reporting is not accurate and useful since profits influence and political interference affect the attainment of truthful, objective, and fair facts that would promote efficiency in newsrooms on environmental reporting.

- Global Warming and Effects Within 50 Years Global warming by few Scientists is often known as “climate change” the reason being is that according to the global warming is not the warming of earth it basically is the misbalance in climate.

- Technology’s Impact on Climate Change To examine the contribution of technology to climate change; To present a comprehensive review of technologically-mediated methods for responding to global flooding caused by anthropogenic climate change; To suggest the most effective and socially just […]

- Global Warming and Climate Change: Fighting and Solutions The work will concentrate on certain aspects such as the background of the problem, the current state of the problem, the existing literature on the problem, what has already been attempted to solve the problem, […]

- Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) in Reducing the Effects of Climate Change The concept remains relevant since it provides fundamental incentives that enable managers to determine the feasibility nature of a project and its viability.

- The Negative Effects of Climate Change in Cities This is exemplified by the seasonal hurricanes in the USA and the surrounding regions, the hurricanes of which have destroyed houses and roads in the past.

- Negative Impacts of Climate Change in the Urban Areas and Possible Strategies to Address Them The current essay is an attempt to outline the problems caused by the negative impacts of climate change in the urban areas.

- How Aviation Impacts Climate Change A measurement of the earth’s radiation budget imbalance brought on by changes in the quantities of gases and aerosols or cloudiness is known as radiative forcing.

- Research Driven Critique: Steven Maher and Climate Change The ravaging effects of Covid-19 must not distract the world from the impending ramifications of severe environmental and climatic events that shaped the lives of a significant portion of the population in the past year.

- Evidence of Climate Change The primary reason for the matter is the melting of ice sheets, which adds water to the ocean. The Republic of Maldives is already starting to feel the effects of global sea-level rise now.

- Technological and Policy Solutions to Prevent Climate Change Scientists and researchers across the globe are talking about the alarming rates of temperature increase, which threaten the integrity of the polar ice caps.

- Climate Change in Abu Dhabi Abu Dhabi is an emirate in the country and it could suffer some of the worst effects of climate change in the UAE.

- Global Warming: People Impact on the Environment One of the reasons for the general certainty of scientists about the effects of human activities on the change of climate all over the globe is the tendency of climate change throughout the history, which […]

- Energy Conservation for Solving Climate Change Problem The United States Environmental Protection Agency reports that of all the ways energy is used in America, about 39% is used to generate electricity.

- Global Warming and Its Effects on the Environment This paper explores the impacts of global warming on the environment and also suggests some of the measures that can be taken to mitigate the impact of global warming on the environment.

- Climate Change as a Global Security Threat It is important to stress that agriculture problems can become real for the USA as well since numerous draughts and natural disasters negatively affect this branch of the US economy.

- The Key Drivers of Climate Change The use of fossil fuel in building cooling and heating, transportation, and in the manufacture of goods leads to an increase in the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere.

- Anthropogenic Climate Change Since anthropogenic climate change occurs due to the cumulative effect of greenhouse gases, it is imperative that climatologists focus on both immediate and long term interventions to avert future crises of global warming that seem […]

- Saving the Forest and Climate Changes The greenhouse gases from such emissions play a key role in the depletion of the most essential ozone layer, thereby increasing the solar heating effect on the adjacent Earth’s surface as well as the rate […]

- Climate Change: Causes and Effects Orbital variations lead to changes in the levels of solar radiation reaching the earth mainly due to the position of the sun and the distance between the earth and the sun during each particular orbital […]

- Impact of Food Waste on Climate Change In conclusion, I believe that some of the measures that can be taken to prevent food waste are calculating the population and their needs.

- Climate Change and Resource Sustainability in Balkan: How Quickly the Impact is Happening In addition, regarding the relief of the Balkans, their territory is dominated by a large number of mountains and hills, especially in the west, among which the northern boundary extends to the Julian Alps and […]

- Climate Change: Renewable Energy Sources Climate change is the biggest threat to humanity, and deforestation and “oil dependency” only exacerbate the situation and rapidly kill people. Therefore it is important to invest in the development of renewable energy sources.

- Climate Change and the Allegory of the Cave Plato’s allegory of the cave reflects well our current relationship with the environment and ways to find a better way to live in the world and live with it.

- Climate Change, Economy, and Environment Central to the sociological approach to climate change is studying the relationship between the economy and the environment. Another critical area of sociologists ‘ attention is the relationship between inequality and the environment.

- The Three Myths of Climate Change In the video, Linda Mortsch debunks three fundamental misconceptions people have regarding climate change and sets the record straight that the phenomenon is happening now, affects everyone, and is not easy to adapt.

- Terrorism, Corruption, and Climate Change as Threats Therefore, threats affecting countries around the globe include terrorism, corruption, and climate change that can be mitigated through integrated counter-terror mechanisms, severe punishment for dishonest practices, and creating awareness of safe practices.

- Climate Change’s Impact on Hendra Virus Transmission to humans occurs once people are exposed to an infected horse’s body fluids, excretions, and tissues. Land clearing in giant fruit bats’ habitats has exacerbated food shortages due to climate change, which has led […]

- Beef Production’s Impact on Climate Change This industry is detrimental to the state of the planet and, in the long term, can lead to irreversible consequences. It is important to monitor the possible consequences and reduce the consumption of beef.

- Cities and Climate Change: Articles Summary The exponential population growth in the United States of America and the energy demands put the nation in a dilemma. Climate change challenges are experienced as a result of an increase in greenhouse gas emissions […]

- The Impact of Climate Change on Vulnerable Human Populations The fact that the rise in temperatures caused by the greenhouse effect is a threat to humans development has focused global attention on the “emissions generated from the combustion” of fossil fuels.

- Food Waste Management: Impact on Sustainability and Climate Change How effective is composting food waste in enhancing sustainability and reducing the effects of climate change? The following key terms are used to identify and scrutinize references and study materials.”Food waste” and sustain* “Food waste” […]

- Protecting the Environment Against Climate Change The destruction of the ozone layer, which helps in filtering the excessive ray of light and heat from the sun, expose people to some skin cancer and causes drought.

- Climate Change and Immigration Issues Due to its extensive coverage of the aspects of climate migration, the article will be significant to the research process in acquiring a better understanding of the effects of climate change on different people from […]

- Global Warming: Speculation and Biased Information For example, people or organizations that deny the extent or existence of global warming may finance the creation and dissemination of incorrect information.

- Impacts of Climate Change on Ocean The development of phytoplankton is sensitive to the temperature of the ocean. Some marine life is leaving the ocean due to the rising water temperature.

- Impact of Climate Change on the Mining Sector After studying the necessary information on the topic of sustainability and Sustainability reports, the organization was allocated one of the activities that it performs to maintain it.

- Climate Change: Historical Background and Social Values The Presidential and Congress elections in the US were usually accompanied by the increased interest in the issue of climate change in the 2010s.

- Communities and Climate Change Article by Kehoe In the article, he describes the stringent living conditions of the First Nations communities and estimates the dangers of climate change for these remote areas.

- Discussion: Reverting Climate Change Undertaking some of these activities requires a lot of finances that have seen governments setting aside funds to help in the budgeting and planning of the institutions.

- Was Climate Change Affecting Species? It was used because it helps establish the significance of the research topic and describes the specific effects of climate change on species.

- Climate Change Attitudes and Counteractions The argument is constructed around the assumption that the deteriorating conditions of climate will soon become one of the main reasons why many people decide to migrate to other places.

- How Climate Change Could Impact the Global Economy In “This is How Climate Change Could Affect the World Economy,” Natalie Marchand draws attention to the fact that over the next 30 years, global GDP will shrink by up to 18% if global temperatures […]

- Effective Policy Sets to Curb Climate Change A low population and economic growth significantly reduce climate change while reducing deforestation and methane gas, further slowing climate change. The world should adopt this model and effectively increase renewable use to fight climate change.

- Climate Change: Social-Ecological Systems Framework One of the ways to understand and assess the technogenic impact on various ecological systems is to apply the Social-Ecological Systems Framework.

- The Climate Change Mitigation Issues Indeed, from the utilitarian perspective, the current state of affairs is beneficial only for the small percentage of the world population that mostly resides in developed countries.

- The Dangers of Global Warming: Environmental and Economic Collapse Global warming is caused by the so-called ‘Greenhouse effect’, when gases in Earth’s atmosphere, such as water vapor or methane, let the Sun’s light enter the planet but keep some of its heat in.

- Wildfires and Impact of Climate Change Climate change has played a significant role in raise the likelihood and size of wildfires around the world. Climate change causes more moisture to evaporate from the earth, drying up the soil and making vegetation […]

- Aviation, Climate Change, and Better Engine Designs: Reducing CO2 Emissions The presence of increasing levels of CO2 and other oxides led to the deterioration of the ozone layer. More clients and partners in the industry were becoming aware and willing to pursue the issue of […]

- Climate Change as a Problem for Businesses and How to Manage It Additionally, some businesses are directly contributing to climate change due to a lack of measures that will minimise the emission of carbon.

- Climate Change and Disease-Carrying Insects In order to prevent the spreading of the viruses through insects, the governments should implement policies against the emissions which contribute to the growth of the insects’ populations.

- Aspects of Global Warming Global warming refers to the steadily increasing temperature of the Earth, while climate change is how global warming changes the weather and climate of the planet.

- David Lammy on Climate Change and Racial Justice However, Lammy argues that people of color living in the global south and urban areas are the ones who are most affected by the climate emergency.

- Moral Aspects of Climate Change Addresses However, these approaches are anthropocentric because they intend to alleviate the level of human destruction to the environment, but place human beings and their economic development at the center of all initiatives.

- Feminism: A Road Map to Overcoming COVID-19 and Climate Change By exposing how individuals relate to one another as humans, institutions, and organizations, feminism aids in the identification of these frequent dimensions of suffering.

- Global Warming: Moral and Political Challenge That is, if the politicians were to advocate the preservation of the environment, they would encourage businesses completely to adopt alternative methods and careful usage of resources.

- Climate Change: Inconsistencies in Reporting An alternative route that may be taken is to engage in honest debates about the issue, which will reduce alarmism and defeatism.

- Climate Change: The Chornobyl Nuclear Accident Also, I want to investigate the reasons behind the decision of the USSR government to conceal the truth and not let people save their lives.

- “World on the Edge”: Managing the Causes of Climate Change Brown’s main idea is to show the possibility of an extremely unfortunate outcome in the future as a result of the development of local agricultural problems – China, Iran, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and others – […]

- The Straw Man Fallacy in the Topic of Climate Change The straw man fallacy is a type of logical fallacy whereby one person misrepresents their opponent’s question or argument to make it easier to respond.

- Gendering Climate Change: Geographical Insights In the given article, the author discusses the implications of climate change on gender and social relations and encourages scholars and activists to think critically and engage in debates on a global scale.

- Climate Change and Its Consequences for Oklahoma This concept can be defined as a rise in the Earth’s temperature due to anthropogenic activity, resulting in alteration of usual weather in various parts of the planet.

- Climate Change Impacts in Sub-Saharan Africa This is why I believe it is necessary to conduct careful, thorough research on why climate change is a threat to our planet and how to stop it.

- Climate Change: Global Warming Intensity Average temperatures on Earth are rising faster than at any time in the past 2,000 years, and the last five of them have been the hottest in the history of meteorological observations since 1850.

- The Negative Results of Climate Change Climate change refers to the rise of the sea due to hot oceans expanding and the melting of ice sheets and glaciers.

- Addressing Climate Change: The Collective Action Problem While all the nations agree that climate change is a source of substantial harm to the economy, the environment, and public health, not all countries have similar incentives for addressing the problem. Addressing the problem […]

- Health Issues on the Climate Change However, the mortality rate of air pollution in the United States is relatively low compared to the rest of the world.

- Collective Climate Change Responsibility The fact is that individuals are not the most critical contributors to the climate crisis, and while ditching the plastic straw might feel good on a personal level, it will not solve the situation.

- Climate Change and Challenges in Miami, Florida The issue of poor environment maintenance in Miami, Florida, has led to climate change, resulting in sea-level rise, an increase of flood levels, and droughts, and warmer temperatures in the area.

- Global Perspectives in the Climate Change Strategy It is required to provide an overview of those programs and schemes of actions that were used in the local, federal and global policies of the countries of the world to combat air pollution.

- Climate Change as Systemic Risk of Globalization However, the integration became more complex and rapid over the years, making it systemic due to the higher number of internal connections.

- Impact of Climate Change on Increased Wildfires Over the past decades, America has experienced the most severe fires in its history regarding the coverage of affected areas and the cost of damage.

- Creating a Policy Briefing Book: Climate Change in China After that, a necessary step included the evaluation of the data gathered and the development of a summary that perfectly demonstrated the crucial points of this complication.

- Natural Climate Solutions for Climate Change in China The social system and its response to climate change are directly related to the well-being, economic status, and quality of life of the population.

- Climate Change and Limiting the Fuel-Powered Transportation When considering the options for limiting the extent of the usage of fuel-powered vehicles, one should pay attention to the use of personal vehicles and the propensity among most citizens to prefer diesel cars as […]

- Climate Change Laboratory Report To determine the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere causing global warming in the next ten decades, if the estimated rate of deforestation is maintained.

- Climate Change: Causes, Impact on People and the Environment Climate change is the alteration of the normal climatic conditions in the earth, and it occurs over some time. In as much as there are arguments based around the subject, it is mainly caused by […]

- Climate Change and Stabilization Wages The more the annual road activity indicates that more cars traversed throughout a fiscal year, the higher the size of the annual fuel consumption. The Carbon Capture and Storage technology can also reduce carbon emissions […]

- UK Climate Change Act 2008 The aim of the UK is to balance the levels of greenhouse gases to circumvent the perilous issue of climate change, as well as make it probable for people to acclimatize to an inevitable climate […]

- Sustainability, Climate Change Impact on Supply Chains & Circular Economy With recycling, reusing of materials, and collecting waste, industries help to fight ecological issues, which are the cause of climate change by saving nature’s integrity.

- Climate Change Indicators and Media Interference There is no certainty in the bright future for the Earth in the long-term perspective considering the devastating aftereffects that the phenomenon might bring. The indicators are essential to evaluate the scale of the growing […]

- Climate Change: Sustainability Development and Environmental Law The media significantly contributes to the creation of awareness, thus the importance of integrating the role of the news press with sustainability practices.

- How Climate Change Affects Conflict and Peace The review looks at various works from different years on the environment, connections to conflict, and the impact of climate change.

- Toyota Corporation: The Effects of Climate Change on the Word’s Automobile Sector Considering the broad nature of the sector, the study has taken into account the case of Toyota Motor Corporation which is one of the firms operating within the sector.

- The Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture However, the move to introduce foreign species of grass such as Bermuda grass in the region while maintaining the native grass has been faced by challenges related to the fiscal importance of the production.

- Health and Climate Change Climate change, which is a universal problem, is thought to have devastating effects on human and animal health. However, the precise health effects are not known.

- The Issue of Climate Change The only confirmed facts are the impact of one’s culture and community on willingness to participate in environmental projects, and some people can refuse to join, thereby demonstrating their individuality.

- Climate Change as a Battle of Generation Z These issues have attracted the attention of the generation who they have identified climate change as the most challenging problem the world is facing today.

- Climate Change and Health in Nunavut, Canada Then, the authors tend to use strict and formal language while delivering their findings and ideas, which, again, is due to the scholarly character of the article. Thus, the article seems to have a good […]

- Climate Change: Anticipating Drastic Consequences Modern scientists focus on the problem of the climate change because of expecting the dramatic consequences of the process in the future.

- The Analysis of Process of Climate Change Dietz is the head of the Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity at the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

- The Way Climate Change Affects the Planet It can help analyze past events such as the Pleistocene ice ages, but the current climate change does not fit the criteria. It demonstrates how slower the change was when compared to the current climate […]

- Polar Bear Decline: Climate Change From Pole to Pole In comparison to 2005 where five of the populations were stable, it shows that there was a decline in stability of polar bear population.

- Preparing for the Impacts of Climate Change The three areas of interest that this report discusses are the impacts of climate change on social, economic and environmental fronts which are the key areas that have created a lot of debate and discussion […]

- Strategy for Garnering Effective Action on Climate Change Mitigation The approach should be participatory in that every member of the community is aware of ways that leads to climate change in order to take the necessary precaution measures. Many member nations have failed to […]

- Impact of Global Climate Change on Malaria There will be a comparison of the intensity of the changes to the magnitude of the impacts on malaria endemicity proposed within the future scenarios of the climate.

- Climate Change Economics: A Review of Greenstone and Oliver’s Analysis The article by Greenstone and Oliver indicates that the problem of global warming is one of the most perilous disasters whose effects are seen in low agricultural output, poor economic wellbeing of people, and high […]

- Rainforests of Victoria: Potential Effects of Climate Change The results of the research by Brooke in the year 2005 was examined to establish the actual impacts of climate change on the East Gippsland forest, especially for the fern specie.

- Pygmy-Possum Burramys Parvus: The Effects of Climate Change The study will be guided by the following research question: In what ways will the predicted loss of snow cover due to climate change influence the density and habitat use of the mountain pygmy-possum populations […]

- Climate Change and the Occurrence of Infectious Diseases This paper seeks to explore the nature of two vector-borne diseases, malaria, and dengue fever, in regards to the characteristics that would make them prone to effects of climate change, and to highlight some of […]

- Links Between Methane, Plants, and Climate Change According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, it is the anthropogenic activities that has increased the load of greenhouse gases since the mid-20th century that has resulted in global warming. It is only the […]

- United Nations Climate Change Conference In the Kyoto protocol, members agreed that nations needed to reduce the carbon emissions to levels that could not threaten the planet’s livelihoods.

- The Involve of Black People in the Seeking of Climate Change Whereas some researchers use the magnitude of pollution release as opposed to closeness to a hazardous site to define exposure, others utilize the dispersion of pollutants model to comprehend the link between exposure and population.

- Climate Change Dynamics: Are We Ready for the Future? One of the critical challenges of preparedness for future environmental changes is the uncertainty of how the climate system will change in several decades.

- How Climate Change Impacts Ocean Temperature and Marine Life The ocean’s surface consumes the excess heat from the air, which leads to significant issues in all of the planet’s ecosystems.

- Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Plan for Abu Dhabi City, UAE Abu Dhabi is the capital city of the UAE and the Abu Dhabi Emirate and is located on a triangular island in the Persian Gulf.

- Global Pollution and Climate Change Both of these works address the topic of Global pollution, Global warming, and Climate change, which are relevant to the current situation in the world.

- Climate Change: The Key Issues An analysis of world literature indicates the emergence in recent years of a number of scientific publications on the medical and environmental consequences of global climate change.

- Climate Change Is a Scientific Fallacy Even in the worst-case scenario whereby the earth gives in and fails to support human activities, there can always be a way out.

- Climate Change: Change Up Your Approach People are becoming aware of the relevance of things and different aspects of their life, which is a positive trend. However, the share of this kind of energy will be reduced dramatically which is favorable […]

- Climate Change: The Broken Ozone Layer It explains the effects of climate change and the adaptation methods used. Vulnerability is basically the level of exposure and weakness of an aspect with regard to climate change.

- Climate Change and Economic Growth The graph displays the levels of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the years before our time with the number 0 being the year 1950.

- Tropic of Chaos: Climate Change and the New Geography of Violence The point of confluence in the cattle raids in East Africa and the planting of opium in the poor communities is the struggle to beat the effects of climatic changes.

- Personal Insight: Climate Change To my mind, economic implications are one of the most concerning because the economy is one of the pillars of modern society.

- A Shift From Climate Change Awareness Under New President Such statements raised concerns among American journalists and general population about the future of the organization as one of the main forces who advocated for the safe and healthy environment of Americans and the global […]

- Human Influence on Climate Change Climate changes are dangerous because they influence all the living creatures in the world. Thus, it is hard to overestimate the threat for humankind the climate changes represent.

- Environmental Studies: Climate Changes Ozone hole is related to forest loss in that the hole is caused by reaction of different chemicals that are found in the atmosphere and some of these gases, for example, the carbon dioxide gas […]

- Global Warming: Negative Effects to the Environment The effect was the greening of the environment and its transformation into habitable zones for humans The second system has been a consequence of the first, storage.

- Global Warming Problem Overview: Significantly Changing the Climate Patterns The government is not in a position to come up with specific costs that are attached to the extent of environmental pollution neither are the polluters aware about the costs that are attached to the […]

- Desert, Glaciers, and Climate Change When the wind blows in a relatively flat area with no vegetation, this wind moves loose and fine particles to erode a vast area of the landscape continuously in a process called deflation.

- Global Change Biology in Terms of Global Warming A risk assessment method showed that the current population could persist for at least 2000 years at hatchling sex ratios of up to 75% male.

- The Politics of Climate Change, Saving the Environment In the first article, the author expresses his concern with the problem of data utilization on climate change and negative consequences arising from this.

- Global Warming Issues Review and Environmental Sustainability

- Neolithic Revolution and Climate Change

- Global Warming: Ways to Help End Global Warming

- Biofuels and Climate Change

- The Influence of Global Warming and Pollution on the Environment

- How Global Warming Has an Effect on Wildlife?

- Climate Change Risks in South Eastern Australia

- The Politics and Economics of International Action on Climate Change

- Climate Change: Influence on Lifestyle in the Future

- Climate Change During Socialism and Capitalistic Epochs

- Climate Change and Public Health Policies

- Climate Changes: Cause and Effect

- Global Warming: Causes and Consequences

- World Trade as the Adjustment Mechanism of Agriculture to Climate Change by Julia & Duchin

- Chad Frischmann: The Young Minds Solving Climate Change

- Climate Change and the Syrian Civil War Revisited

- Public Health Education on Climate Change Effects

- Research Plan “Climate Change”

- Diets and Climate Change

- The Role of Human Activities on the Climate Change

- Corporations’ Impact on Climate Change

- Climate Change Factors and Countermeasures

- Climate Change Effects on Population Health

- Climate Change: Who Is at Fault?

- Climate Change: Reducing Industrial Air Pollution

- Global Climate Change and Biological Implications

- Weather Abnormalities and Climate Change

- Global Warming, Its Consequences and Prevention

- Climate Change and Risks for Business in Australia

- Climate Change Solutions for Australia

- Climate Change, Industrial Ecology and Environmental Chemistry

- “Climate Change May Destroy Alaskan Towns” Video

- Climate Change Effects on Kenya’s Tea Industry

- Dealing With the Climate Change Issues

- Environmental Perils: Climate Change Issue

- Technologically Produced Emissions Impact on Climate Change

- City Trees and Climate Change: Act Green and Get Healthy

- Climate Change and American National Security

- Anthropogenic Climate Change and Policy Problems

- Climate Change, Air Pollution, Soil Degradation

- Climate Change in Canada

- International Climate Change Agreements

- Polar Transformations as a Global Warming Issue

- Moral Obligations to Climate Change and Animal Life

- Climate Change Debates and Scientific Opinion

- Earth’s Geologic History and Global Climate Change

- CO2 Emission and Climate Change Misconceptions

- Geoengineering as a Possible Response to Climate Change

- Climate Change: Ways of Eliminating Negative Effects

- Climate Change Probability and Predictions

- Climate Changes and Human Population Distribution

- Climate Change as International Issue

- Climate Change Effects on Ocean Acidification

- Climate Change Governance: Concepts and Theories

- Climate Change Management and Risk Governance

- United Nation and Climate Change

- Human Rights and Climate Change Policy-Making

- Climate Change: Anthropological Concepts and Perspectives

- Climate Change Impacts on Business in Bangladesh

- Environmental Risk Perception: Climate Change Viewpoints

- Pollution & Climate Change as Environmental Risks

- Climate Change: Nicholas Stern and Ross Garnaut Views

- Challenges Facing Humanity: Technology and Climate Change

- Climate Change Potential Consequences

- Climate Change in United Kingdom

- Climate Change From International Relations Perspective

- Climate Change and International Collaboration

- International Security and Climate Change

- Climate and Conflicts: Security Risks of Global Warming

- Climate Change Effects on World Economy

- Climate Change Vulnerability in Scotland

- Global Warming and Climate Change

- Responsible Factors for Climate Change

- Organisational Sustainability and Climate Change Strategy

- The Effect of Science on Climate Change

- “Climate Change: Turning Up the Heat” by Barrie Pittock

- Vulnerability of World Countries to Climate Change

- Anthropogenic Climate Change

- The Implementation of MOOCs on Climate Change

- The Climate Change and the Asset-Based Community Development

- Climate Change Research Studies

- Environmental Issue – Climate Change

- Climate Change Negative Health Impacts

- Managing the Impacts of Climate Change

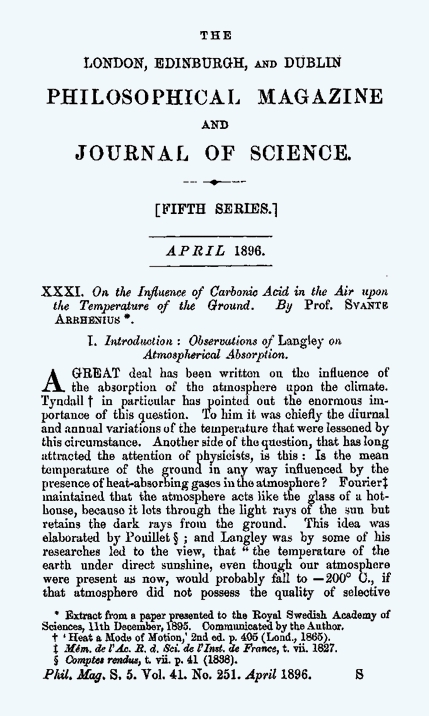

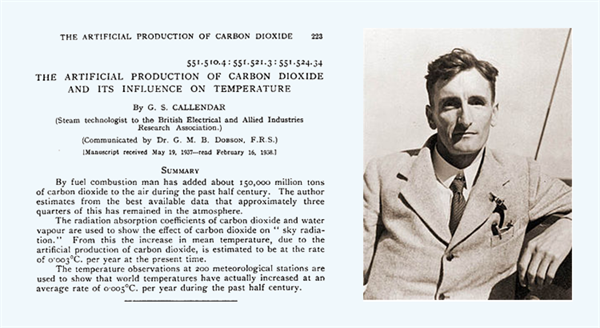

- Early Climate Change Science

- Views Comparison on the Problem of Climate Change

- Climate Change and Corporate World

- Climate Change Affecting Coral Triangle Turtles

- Introduction to Climate Change: Major Threats and the Means to Avoid Them

- Climate Change and Its Effects on Indigenous Peoples

- Asian Drivers of Global Change

- The Causes and Effects of Climate Change in the US

- Metholdogy for Economic Discourse Analysis in Climate Change

- The Impact of Climate Change on New Hampshire Business

- Climate Change Effects on an Individual’s Life in the Future

- Ideology of Economic Discourse in Climate Change

- The Role of Behavioural Economics in Energy and Climate Policy

- The Economic Cost of Climate Change Effects

- Transforming the Economy to Address Climate Change and Global Resource Competition

- Climate Change: Is Capitalism the Problem or the Solution?

- Climate Change: Floods in Queensland Australia

- Impact of Climate Change and Solutions

- Climate Change and Its Global Implications in Hospitality and Tourism

- Climate Changes: Snowpack

- Climate Change and Consumption: Which Way the Wind Blows in Indiana

- The United Nation’s Response to Climate Change

- Need for Topic on Climate Change in Geography Courses

- Critical Review: “Food’s Footprint: Agriculture and Climate Change” by Jennifer Burney

- Economics and Human Induced Climate Change

- Biology of Climate Change

- Business & Climate Change

- Global Warming Causes and Unfavorable Climatic Changes

- Spin, Science and Climate Change

- Climate Change, Coming Home: Global Warming’s Effects on Populations

- Social Concepts and Climate Change

- Climate Change and Human Health

- Climate Changes: Human Activities and Global Warming

- Tourism and Climate Change Problem

- Public Awareness of Climate Changes and Carbon Footprints

- Climate Change: Impact of Carbon Emissions to the Atmosphere

- Problems of Climate Change

- Solving the Climate Change Crisis Through Development of Renewable Energy

- Climate Change Is the Biggest Challenge in the World That Affects the Flexibility of Individual Specie

- Climate Changes

- Ways to Reduce Global Warming

- Climate Change Definition and Causes

- Climate Change: Nearing a Mini Ice Age

- Global Warming Outcomes and Sea-Level Changes

- China Climate Change

- Protecting Forests to Prevent Climate Change

- Climate Change in Saudi Arabia and Miami

- Effects of Global Warming on the Environment

- Threat to Biodiversity Is Just as Important as Climate Change

- Does Climate Change Affect Entrepreneurs?

- Does Climate Change Information Affect Stated Risks of Pine Beetle Impacts on Forests

- Does Energy Consumption Contribute to Climate Change?

- Does Forced Solidarity Hinder Adaptation to Climate Change?

- Does Risk Communication Really Decrease Cooperation in Climate Change Mitigation?

- Does Risk Perception Limit the Climate Change Mitigation Behaviors?

- What Are the Differences Between Climate Change and Global Warming?

- What Are the Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture in North East Central Europe?

- What Are the Policy Challenges That National Governments Face in Addressing Climate Change?

- What Are the Primary Causes of Climate Change?

- What Are the Risks of Climate Change and Global Warming?

- What Does Climate Change Mean for Agriculture in Developing Countries?

- What Drives the International Transfer of Climate Change Mitigation Technologies?

- What Economic Impacts Are Expected to Result From Climate Change?

- What Motivates Farmers’ Adaptation to Climate Change?

- What Natural Forces Have Caused Climate Change?

- What Problems Are Involved With Establishing an International Climate Change?

- What Role Has Human Activity Played in Causing Climate Change?

- Which Incentives Does Regulation Give to Adapt Network Infrastructure to Climate Change?

- Why Climate Change Affects Us?

- Why Does Climate Change Present Potential Dangers for the African Continent?

- Why Economic Analysis Supports Strong Action on Climate Change?

- Why Should People Care For the Perceived Event of Climate Change?

- Why the Climate Change Debate Has Not Created More Cleantech Funds in Sweden?

- Why Worry About Climate Change?

- Will African Agriculture Survive Climate Change?

- Will Carbon Tax Mitigate the Effects of Climate Change?

- Will Climate Change Affect Agriculture?

- Will Climate Change Cause Enormous Social Costs for Poor Asian Cities?

- Will Religion and Faith Be the Answer to Climate Change?

- Flood Essay Topics

- Ecosystem Essay Topics

- Atmosphere Questions

- Extinction Research Topics

- Desert Research Ideas

- Greenhouse Gases Research Ideas

- Recycling Research Ideas

- Water Issues Research Ideas

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 337 Climate Change Research Topics & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/climate-change-essay-examples/

"337 Climate Change Research Topics & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/climate-change-essay-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '337 Climate Change Research Topics & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "337 Climate Change Research Topics & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/climate-change-essay-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "337 Climate Change Research Topics & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/climate-change-essay-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "337 Climate Change Research Topics & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/climate-change-essay-examples/.

317 Climate Change Essay Topics

Looking for fresh and original climate change titles for your assignment? Look no further! Check out this list of excellent climate change topics for essays, research papers, and presentations. Need some additional inspiration? Click on the links to access helpful climate change essay samples!

🏆 Best Essay Topics on Climate Change

📚 catchy climate change essay topics, 👍 good climate change research topics & essay examples, 🎓 most interesting climate change research titles, 🌶️ hot climate change topics for research, 💡 simple climate change essay ideas, ✍️ climate change essay topics for college, ❓ climate change research paper questions, ✅ climate change topics for presentation, 🔎 current climate change topics for research, ⭐ climate change research topics: our list’s benefits.

- The Problem of Global Warming and Ways of Its Solution

- Environmental Health Theory and Climate Change

- Climate Change: The Impact of Technology

- Food Security: The Impact of Climate Change

- Tree Planting and Climate Change

- Climate Change Impacts

- Global Warming and Ozone Depletion

- Global Warming is Not a Myth All facts points out that the ranging debate on whether global warming is a myth or reality has been squarely won by the global warming proponents.

- Climate Change in Africa and How to Address It According to environmental scientists, Africa is exposed to the effects of climatic alterations subject to its elevated levels of poverty, and dependence on rain-fed farming.

- How Climate Changes Affect Coastal Areas Natural disasters and hazards caused by climate change are especially the cases during modern times, as the number of toxic substances and polluting elements is increasing every year.

- Energy Crisis and Climate Change The global community needs to adopt an energy efficient behavior and invest in the exploration of sustainable energy resources.

- Solving the Climate Change Crisis by Using Renewable Energy Sources Climate change has caused extreme changes in temperature and weather patterns on planet Earth, thus threatening the lives of living organisms.

- Extreme Weather and Global Warming The Global warming is a bad phenomenon that is causing to see level raise, change weather pattern, and create alteration in animal life.

- Climate Change Impacts on Oceans The consequences of climate change on seawater have had harmful impacts, including irreversible damage to the water’s natural environment and ecological system.

- Climate Change and Future Generations The consequences of global warming can be extremely dire for future generations. Temperature, if increased by one and a half degrees, will push natural systems to a turning point.

- Effects of Global Warming: Essay Example According to environmentalists and other nature conservatives, Africa would be the worst hit continent by the effects of global warming despite emitting less greenhouse gases.

- Climate Change and Corporate Responsibility The problem of climate change is not new, but it becomes more and more crucial nowadays. The first changes in climate were observed during the industrial period, from the 1750s.

- Social Issue: Climate Change The topic of climate change was chosen to learn more in the modern sense about the phenomenon that most people have heard about for decades.

- Climate Change: Concept and Theories Climate change has become a concern of scientists rather recently. There are numerous theories as to the reasons for this process, but there are still no particular answers.

- Global Warming Effects on the Environment and Animals Global warming is a threat to the survival and well-being of human and animal life. This discussion aims to provide the effects of the current global warming threats.

- How Global Warming Affects Wildlife Global warming is a matter of great concern since it affects humans and wildlife directly, and this issue should be addressed appropriately.

- Al Gore’s Speech on Global Warming Using two essential constituents of a subtle rhetoric analysis for speech or text, the paper scrutinizes Al Gore’s speech on global warming.

- Climate Changes Impact on Agriculture and Livestock The project evaluates the influences of climate changes on agriculture and livestock in different areas in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

- Climate Change and Global Warming Global warming is a subject that has elicited a heated debate for a long time. This debate is commonplace among scholars and policy makers.

- Impact of Climate Change on Property Development and Management This essay will focus on the BBC article, COP26 promises could limit global warming to 1.8C, with a specific focus on the impact of climate change on property development.

- Climate Change in Terms of Project Management The primary aim of the following paper is to define the notion of climate change in terms of project management, risk management, and business communication.

- Water Scarcity as Effect of Climate Change Climate change is the cause of variability in the water cycle, which also reduces the predictability of water availability, demand, and quality, aggravating water scarcity.

- Security and Climate Change Climate change has been happening at an unprecedented rate over the last decade to become a major global concern.

- How Climate Change Impacts Aviation The issue of climate change and its impact on the aviation industry has been a developing story lately due to the two-way relationship between them.

- Electric Vehicles and Their Impact on Climate Change Internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEV) that have dominated the market over the recent decades are now giving way to electric vehicles (EV) experiencing rapid growth.

- The Problem of Climate Change in the 21st Century Climate change is among the top threats facing the world in the 21st century, and it deserves prioritization when planning how to move the country and the globe forward.

- “The Basics of Climate Change” Blog The author of “The Basics of Climate Change” reveals the main concepts about the balance between the input and output of energy on Earth that directly relate to the climate.

- Global Warming: Myth or Reality? Global warming can be described as a progressive increase in the earth’s temperature as a result of a trap to greenhouse gases within its atmosphere.

- Fast Fashion and Its Impacts on Global Warming Fast fashion contributes to this change in weather conditions due to its improper disposal, leading to the release of emissions into the atmosphere, thus causing global warming.

- The Effect of Global Warming and the Future Global warming effects are the social and environmental changes brought-about by the increase in global temperatures.

- Climate Change: A Global Concern The phenomenon of climate change has attracted a notable amount of attention, the early 1990s being the point at which the phenomenon in question became a worldwide concern.

- Climate Change as a Healthcare Priority Human-caused climate change significantly impacts the ecological situation and many areas of human life, such as health care.

- Philosophers’ Theories on Climate Change The paper demonstrates two philosophers’ theories on climate change, namely Laura Westra and Graham Long. The thoughts and ideas are evaluated by using a hypothetical situation.

- Global Warming and Business Ethics Business ethics is significant in promoting effective industrial activities that promote environmental conservation and reduce global warming.

- Climate Change and Accessibility to Safe Water The paper discusses climate change’s effect on water accessibility, providing graphs on water scarcity and freshwater use and resources.

- Discussion of Impact of Climate Change in Society Modern scholars and environmentalists acknowledge that climate change is a major challenge affecting the global society today.

- Climate Change and Impact on Human Health In this paper, two academic articles that discuss the problem of climate change and its impact on human health will be reviewed.

- Climate Change Policies and Regulation The current changes in climate patterns have attracted attention from researchers and institutions as they endeavor to formulate and implement policies.

- Multinational Corporations and Climate Change The current essay revolves around the topic of climate change and economic activities. In the essay, the author focuses on MNCs and their role in environmental conservation.

- Climate Change and Global Health Climate change is among the most discussed topics in various fields, as it has overarching effects on many aspects of human life.

- The Controversies of Climate Change This paper discusses the issue of climate change by considering the arguments presented by both the proponents and opponents based on ethical principles and sources of moral value.

- Global Warming: Causes, Factors and Effects The main factors that have been attributed to the resulting global warming are the green house gas effects, differences in the solar and also volcanoes.

- Climate Change and Environmental Degradation Creating a planning model for climate change and environmental degradation requires a comprehensive approach that considers multiple factors.

- Climate Change and Resource Scarcity The paper states that Sustainable Development Goal 13, Climate Action, is the United Nations’ goal to take urgent action to combat climate change.

- Climate Change as an Ethical Issue Although global warming is a hotly debated topic, some groups claim that the issue is not as acute as it is presented.

- The Effect of Climate Change on Weather Climate change is resulting in weather extremes that are affecting millions of people around the world in recent times.

- Investing in Climate Change vs. Space Exploration Efforts aimed at investing in climate change versus outer space exploration will be compared in this essay, and their consequences will be analyzed.

- Social Challenges of Climate Change Climate change is among the most pressing global issues, and it is not easy to find a solution that will work for everyone.

- Greenhouse Effect as a Cause of Global Warming The report serves an informative function and is designed to explore the nature of global warming through the greenhouse effect.

- Climate Change From the Anthropological Perspective The adaptive nature of the anthropological development of humanity explains the contemporary global problems, and climate change may be assessed from the human adaptation perspective.

- The Global Impact of Climate Change Into Our Homes and Families A home is a significant part of someone’s life. That’s why it is always considered as part of basic needs. They give people a sense of belonging and security.

- The Importance of Addressing Climate Change Climate change is a topical issue, and the way humanity will choose to address it will determine whether major negative consequences can be avoided.

- Journal and Newspaper Collection on Global Warming This paper comments on Journal/ newspaper article on global warming from major newspapers and journals around the world

- Car Emissions and Global Warming The emissions problem that is caused by the excessive use of cars is an issue that affects most of the modern world and needs to be addressed as soon as possible to prevent further adverse impact.

- Health Issues Caused by Climate Change The elevation of temperature changes the weather patterns and causes intensive snowstorms, heatwaves, floods, droughts, rising sea levels, and wildfires.

- Climate Change and Related Issues in Canada The essay argues that modern sources of scientific knowledge about climate change can drastically change people’s attitudes to an eco-friendly lifestyle.

- Napa Valley Wine Industry and Climate Change The current competitive landscape of the Napa Valley is formed from a multitude of stakeholders of varying sizes. The work studies climate change and the Napa Valley wine industry.

- Climate Change and Its Evidence The review of common claims about global warming made it possible to say that in spite of some skeptical opinions, it might be really happening.

- Global Warming Causes and Impacts This paper endeavors to delineate the history of global warming, the causality and every potential revelation towards diminution of the impacts of global warming.

- Solubility of Carbon Dioxide Related to Climate Change The solubility of carbon dioxide is directly related to climate change because oceans absorb excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

- Climate Change and Global Warming Awareness If people continue to have misconceptions about global warming, climate change will negatively impact weather, food security, and biodiversity.

- Climate Changes Effects on the North and South Pole Global climate change has led to major problems in the North and South Pole ecosystems, with many animals losing their homes and even becoming endangered.

- “The Impact of Climate Change Mitigation Strategies on Animal Welfare” by Shields and Orme-Evans The paper states that for animal welfare to improve, climate change mitigation strategies should encompass systematic changes in the industry.

- Climate Change and the Media Biases This essay’s purpose is to address the media bias concerning the rising global warming and climate change, referring to news articles made by scientists and various scholars.

- Climate Change and Food Production Cycle In order to address the problem of climate change in relation to the overproduction of food, a more responsible attitude toward its consumption.

- The Impact of Climate Change on the United States Climate change is a serious issue faced by the United States, and it has various effects, including in the spheres of economy, animal habitat, and health of the population.

- The Catholic Response to the Climate Change Catholic Church joined other global climate change movements such as Action for climate change by the United Nations to champion a safer and sustainable ecosystem by 2050.

- Climate Change: Dangers and Prevention This paper explores anthropogenic and natural causes of climate change examine its potential outcomes and presents actions aimed at stabilizing the climate.

- How Climate Change Increases the Risk of Hurricanes Hurricanes generate significant financial loss particularly in areas with a high degree of development activities.

- Human Impact on the Environment Leading to Climate Change An elevated amount of greenhouse gases results in the retention of solar energy in the low levels of the atmosphere, which in turn brings to the melting of glaciers.

- Sustainable Development: The Climate Change Issues Climate change, spurred by economic and population growth, has affected humans and natural systems in every country on every continent.

- Climate Change as a Challenge to Australia Climate change is characterised by changes in the weather conditions brought about by emissions from industries as well as emissions from agriculture.

- Global Warming and Mitigation Strategies The paper outlines causes of global warming and possible impact on human beings. There is also an evaluation of strategies applied in realization of environmental sustainability.

- Climate Change and Its Potential Impact on Agriculture and Food Supply The global food supply chain has been greatly affected by the impact of global climate change. There are, however, benefits as well as drawbacks to crop production.

- Climate Change and Social Responsibility in the UAE The UAE is rapidly developing for several decades already, which has a positive influence on the well-being of the population.

- Remote Sensing Applications to Climate Change Remote sensing is defined as the measurement of information and area property on the Earth’ surface by means of satellites and aircrafts.

- Climate Change and Human Heath Climate change has been rated among the top issues which have continued to draw much concern and interest in modern study and research.

- Car Emission Effects on Global Warming Car emissions are expected to aid policy makers in national governments, automobile manufacturers, fuel industry CEOs and city planners.

- Climate Change: Impact on Extreme Weather Events The article summarizes the scientific paper on the impact of climate change on extreme weather events worldwide.

- Desertification and Climate Change Desertification can be prevented by holistic and planned grazing. This transformation can lead to better outcomes in the fight against climate change.

- Climate Change and Creation of Earth Day Climate change enables communities to create environmental initiatives, industries to update their manufacturing, and politicians to influence the problem through their campaigns.

- How Climate Change Influenced Global Migration Migration and conflict have become the most important reasons causing researchers’ interest in climate change.

- Carbon Markets and Climate Change Many climatological concepts predict a rise in worldwide average temperature over the succeeding few decades centered on tripling atmospheric carbon oxide levels.

- How Human Activities Cause Climate Change Scientists and various leaders globally have seriously debated the causes of climate change. This essay involves a discussion of how human activities cause climate change.

- Consequences of Global Warming Although the opinions about the causes of climate change are diverse, the effects of human activities and natural elements are similar and lead to global warming.

- Water Scarcity Due to Climate Change This paper focuses on the adverse impact that water scarcity has brought today with the view that water is the most valuable element in running critical processes.

- Climate Change in Environmentally Vulnerable Countries The repercussions of climate change are global in character and unprecedented in size, ranging from changing weather patterns to sea level rise.

- Climate Change and Carbon Dioxide Emissions Climate change is in large part caused by human action, and the continued industrial development of the world can be accredited to exacerbating the problem further than ever.

- Climate Change and Environmental Anxiety Individuals must develop a strategy to be able to resist climate change. In addition, there is a need for a global plan to restrain the influence of global warming.

- Causes of Climate Change and Ways to Reduce It Despite the effects, investing in green energy, increasing vegetation cover, and conducting public education are some measures that can be taken to reduce climate change.

- Anthropogenic Influence on Climate Change Throughout History The objective of this paper is to discuss the anthropogenic influence on climate change through history and adaptations during the glaciation period.

- Web-Based Organizational Discourses: Climate Change This paper pertains to the investigation of argumentation formation within the process of interaction with organizations holding similar and opposite opinions and viewpoints.

- Economic Model for Global Warming The adoption of various economic models is a superior strategy that appears promising and capable of guiding policymakers and nations to tackle the predicament of climate change.

- Modern Environmental Issues: Climate Change Climate change had taken place before humans evolved, but the issue lies in the one, which is caused by direct human intervention.

- Global Warming and Climate Change Climate change is caused by greenhouse gas emissions resulting from human activities, mainly through the energy and transport sectors.

- The Impact of Climate Change on Inflectional Diseases This paper will examine the increasing spread of infectious diseases as one of the effects of climate change, as well as current and possible measures to overcome it.

- Global Warming: Issue Analysis Global warming is a term commonly used to describe the consequences of man- made pollutants overloading the naturally-occurring greenhouse gases causing an increase of the average global temperature.

- Global Warming: Causes and Consequences Global warming is the result of high levels of greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, water vapor, methane, and ozone) in the earth’s atmosphere.

- Global Warming as a Humanity’s Fault World leaders were forced to hold discussions in Kigali, Rwanda, in late 2016 to establish a deal addressing mechanisms to be adopted to curb global warming.

- The Issue of Global Climate Change and the Use of Global Ethic Modern technologies such as “the use of satellites have made it easier for scientists to analyze climate on a global scale”.

- Questions on Information Revolution and Global Warming The information revolution characterizes the period of change propelled by the development of computer technology. Technological advancements impact people’s lives.

- The Climate Change Issue in the Political Agenda One of the significant challenges modern societies have in combating the harmful impacts of climate change is the political agenda, which obscures the more comprehensive picture.

- Climate Change: The Negative Effects Climate change impacts the world through weather changes. Extreme weather events are becoming more common and more severe. Climate change is also causing the ocean to acidify.

- Climate Change Threats to Global Hospitality Industry Climate change is a growing threat to the global hospitality industry, and humanity must take action to mitigate its impact.

- Climate Change as a Global Problem One of the global problems of our time is global warming. This problem is relevant not in any particular country but all over the world.

- Is the Threat of Global Warming Real? Increases in Earth’s average temperature over an extended period are called global warming. Greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere have recently increased.

- Climate Change Threats in Public Perception Diverse social, economic, ecological, and geopolitical variables that operate on multiple scales contribute to different levels of human vulnerability to climate change threats.

- The Key to Addressing Climate Change in Modern Business Globalisation, industrialisation, and rise of global corporations promoted the increased topicality of the climate change topic and its transformation into a shared problem.

- Overpopulation, Climate Change, and Security Issues This research paper examines such social and environmental issues as overpopulation, urbanization, climate change, food security, and air pollution.

- Climate Change: Nature Communications Climate change is one of the main concerns in contemporary global society. This subject is an issue of great contention, with different sides disagreeing.

- Global Warming: Understanding Causes of Event Global warming is a phenomenon characterized by the gradual increase of the temperature of the earth’s atmosphere.

- Climate Change and Its Impact on the Weather Climate change is a serious issue nowadays, considering that it is bound to affect my generation and the next ones.

- Climate Change: Impact on Lemurs Climate change and other environmental issues severely impact the lifestyle and behaviors of lemurs. High temperatures make lemurs spend more time on the ground.

- Climate Change: Causes, Dynamics, and Effects It is crucial to provide a description of the problem of the climate crisis, its causes and effects, and possible prevention measures.

- Ethical, Moral, and Christian Views on Climate Change Strategies Climate change strategies pose ethical, moral, and religious concerns that influence people to bring change and conserve the environment.

- The History of Climate Change and Global Warming Issue The paper states that the history of climate change and the solutions communities opted for are critical to tackling the current global warming issue.

- Greenpeace’s Climate Change Article Review The article What Are the Solutions to Climate Change by Greenpeace explains the ways climate change can be resolved while using comprehensive terms and being concise.

- Worldwide Effects of Global Warming The article conveys Trenberth’s message about the far-reaching implications of global warming on climate and the urgent need for collective action to address its consequences.

- Climate Change and Health: Public Health Human activity influences the environment in various ways, from climate change acceleration to the increasing deforestation that can cause another global pandemic.

- Global Warming and Climate Change and Their Impact on Humans Climate change and global warming are significant issues with negative impacts on all aspects of human life; for example, they disrupt the food web, hurting humans and wildlife.

- Earth Day and the Climate Change Agenda This research paper examines the social significance and ecological value of Earth Day in the face of the climate change agenda.

- The Earth Day and Climate Change Climate change remains a relevant topic despite over fifty years of efforts since the establishment of Earth Day in 1970.

- The Climate Change Impact on Sea Levels and Coastal Zones This paper summarizes the effects of climate change on seawater levels and subsequent effects on the coastal zones.

- Importance of Climate Change Issue Decision The situation of climate change is the central issue of the 21st century, and its solution is a turning point in history.

- Climate Change Mitigation Strategies and Animals The thesis of the article is clear and identifies two main points, which are the problem that the global discussion does not propose sufficient methods to solve the issue.

- The Climate Change: Project Topic Exploration Climate change is an environmental problem that relates to an increase in the Earth’s average surface temperature.