John Locke: Natural Rights to Life, Liberty, and Property

Locke's writings did much to inspire the american revolution..

A number of times throughout history, tyranny has stimulated breakthrough thinking about liberty . This was certainly the case in England with the mid-17th-century era of repression, rebellion, and civil war. There was a tremendous outpouring of political pamphlets and tracts. By far the most influential writings emerged from the pen of scholar John Locke .

He expressed the radical view that government is morally obliged to serve people, namely by protecting life, liberty, and property. He explained the principle of checks and balances to limit government power. He favored representative government and a rule of law . He denounced tyranny . He insisted that when government violates individual rights, people may legitimately rebel.

These views were most fully developed in Locke’s famous Second Treatise Concerning Civil Government , and they were so radical that he never dared sign his name to it. He acknowledged authorship only in his will. Locke’s writings did much to inspire the libertarian ideals of the American Revolution . This, in turn, set an example which inspired people throughout Europe, Latin America, and Asia.

Thomas Jefferson ranked Locke, along with Locke’s compatriot Algernon Sidney, as the most important thinkers on liberty. Locke helped inspire Thomas Paine ’s radical ideas about revolution. Locke fired up George Mason. From Locke, James Madison drew his most fundamental principles of liberty and government. Locke’s writings were part of Benjamin Franklin’s self-education, and John Adams believed that both girls and boys should learn about Locke. The French philosopher Voltaire called Locke “the man of the greatest wisdom. What he has not seen clearly, I despair of ever seeing.”

It seems incredible that Locke, of all people, could have influenced individuals around the world. When he set out to develop his ideas, he was an undistinguished Oxford scholar. He had a brief experience with a failed diplomatic mission. He was a physician who long lacked traditional credentials and had just one patient. His first major work wasn’t published until he was 57. He was distracted by asthma and other chronic ailments.

There was little in Locke’s appearance to suggest greatness. He was tall and thin. According to biographer Maurice Cranston, he had a “long face, large nose, full lips, and soft, melancholy eyes.” Although he had a love affair which, he said, “robbed me of the use of my reason,” he died a bachelor.

Some notable contemporaries thought highly of Locke. Mathematician and physicist Isaac Newton cherished his company. Locke helped Quaker William Penn restore his good name when he was a political fugitive, as Penn had arranged a pardon for Locke when he had been a political fugitive. Locke was described by the famous English physician Dr. Thomas Sydenham as “a man whom, in the acuteness of his intellect, in the steadiness of his judgement, … that is, in the excellence of his manners, I confidently declare to have, amongst the men of our time, few equals and no superiors.”

Family Background

John Locke was born in Somerset, England, August 29, 1632. He was the eldest son of Agnes Keene, daughter of a small-town tanner, and John Locke, an impecunious Puritan lawyer who served as a clerk for justices of the peace.

When young Locke was two, England began to stumble toward its epic constitutional crisis . The Stuart King Charles I, who dreamed of the absolute power wielded by some continental rulers, decreed higher taxes without approval of Parliament. They were to be collected by local officials like his father. Eight years later, the Civil War broke out, and Locke’s father briefly served as a captain in the Parliamentary army. In 1649, rebels beheaded Charles I. But all this led to the Puritan dictatorship of Oliver Cromwell.

Locke had a royalist and Anglican education, presumably because it was still a ticket to upward mobility. One of his father’s politically connected associates nominated 15-year-old John Locke for the prestigious Westminster School. In 1652, he won a scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford University’s most important college, which trained men mainly for the clergy. He studied logic, metaphysics, Greek, and Latin . He earned his bachelor of arts degree in 1656, then continued work toward a master of arts and taught rhetoric and Greek. On the side, he spent considerable time studying with free spirits who, at the dawn of modern science and medicine, independently conducted experiments.

Having lived through a bloody civil war, Locke seems to have shared the fears expressed by fellow Englishman Thomas Hobbes , whose Leviathan (1651) became the gospel of absolutism . Hobbes asserted that liberty brought chaos, that the worst government was better than no government—and that people owed allegiance to their ruler, right or wrong. In October 1656, Locke wrote a letter expressing approval that Quakers—whom he called “mad folks”—were subject to restrictions. Locke welcomed the 1660 restoration of the Stuart monarchy and subsequently wrote two tracts that defended the prerogative of government to enforce religious conformity.

In November 1665, as a result of his Oxford connections, Locke was appointed to a diplomatic mission aimed at winning the Elector of Brandenburg as an ally against Holland. The mission failed, but the experience was a revelation. Brandenburg had a policy of toleration for Catholics, Calvinists, and Lutherans , and there was peace. Locke wrote his friend Robert Boyle, the chemist: “They quietly permit one another to choose their way to heaven; and I cannot observe any quarrels or animosities amongst them on account of religion.”

Locke and Shaftesbury

During the summer of 1666, the rich and influential Anthony Ashley Cooper visited Oxford where he met Locke who was then studying medicine. Cooper suffered from a liver cyst that threatened to become swollen with infection. Cooper asked Locke, apparently competent, courteous, and amusing, to be his personal physician. Accordingly, Locke moved into a room at Cooper’s Exeter House mansion in London. Locke was about to embark on adventures which would convert him to a libertarian .

Cooper was born an aristocrat, served in the King’s army during the Civil War, switched to the Puritan side, and commanded Puritan soldiers in Dorset. But he was dismissed amidst Puritan purges. He was arrested for conspiring to overthrow the Puritan Commonwealth and bring back the Stuarts. King Charles II elevated him to the peerage—he became Lord Ashley, then the Earl of Shaftesbury—and joined the King’s Privy Council.

Soon Shaftesbury spearheaded opposition to the Restoration Parliaments, which enacted measures enforcing conformity with Anglican worship and suppressing dissident Protestants. He became a member of the four-man cabinet and served briefly as Lord High Chancellor, the most powerful minister. Shaftesbury championed religious toleration for all (except Catholics) because he had seen how intolerance drove away talented people and how religious toleration helped Holland prosper. He invested in ships, some for the slave trade. He developed Carolina plantations. Locke is believed to have drafted virtually the entire Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina , providing for a parliament elected by property owners, a separation of church and state , and—surprisingly—military conscription.

Shaftesbury’s liver infection worsened, and Locke supervised successful surgery in 1668. The grateful Shaftesbury encouraged Locke to develop his potential as a philosopher. Thanks to Shaftesbury, Locke was nominated for the Royal Society, where he mingled with some of London’s most fertile minds. In 1671, with a half-dozen friends, Locke started a discussion group to talk about the principles of morality and religion . This led him to further explore the issues by writing early drafts of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding .

Shaftesbury retained Locke to analyze toleration, education, trade, and other issues, which spurred Locke to expand his knowledge. For example, Locke opposed government regulation of interest rates :

The first thing to be considered is whether the price of the hire of money can be regulated by law; and to that, I think generally speaking that ’tis manifest that it cannot. For, since it is impossible to make a law that shall hinder a man from giving away his money or estate to whom he pleases, it will be impossible by any contrivance of law, to hinder men … to purchase money to be lent to them. …

Locke was in the thick of just about everything Shaftesbury did. Locke helped draft speeches. He recorded the progress of bills through Parliament. He kept notes during meetings. He evaluated people considered for political appointments. Locke even negotiated the marriage terms for Shaftesbury’s son and served as tutor for Shaftesbury’s grandson.

Shaftesbury formed the Whig party, and Locke, then in France, carried on a correspondence to help influence Parliamentary elections. Shaftesbury was imprisoned for a year in the Tower of London, then he helped pass the Habeas Corpus Act (1679), which made it unlawful for government to detain a person without filing formal charges or to put a person on trial for the same charge twice. Shaftesbury pushed “exclusion bills” aimed at preventing the king’s Catholic brother from royal succession.

Countering Stuart Absolutism

In March 1681, Charles II dissolved Parliament, and it soon became clear that he did not intend to summon Parliament again. Consequently, the only way to stop Stuart absolutism was rebellion. Shaftesbury was the king’s most dangerous opponent, and Locke was at his side. A spy named Humphrey Prideaux reported on Locke’s whereabouts and on suspicions that Locke was the author of seditious pamphlets.

In fact, Locke was contemplating an attack on Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha, or The Natural Power of Kings Asserted (1680), which claimed that God sanctioned the absolute power of kings. Such an attack was risky since it could easily be prosecuted as an attack on King Charles II. Pamphleteer James Tyrrell, a friend whom Locke had met at Oxford, left unsigned his substantial attack on Filmer, Patriarcha Non Monarcha or The Patriarch Unmonarch’d ; and Tyrrell had merely implied the right to rebel against tyrants. Algernon Sidney was hanged, in part, because the king’s agents discovered his manuscript for Discourses Concerning Government .

Locke worked in his bookshelf-lined room at Shaftesbury’s Exeter House, drawing on his experience with political action. He wrote one treatise which attacked Filmer’s doctrine. Locke denied Filmer’s claim that the Bible sanctioned tyrants and that parents had absolute authority over children. Locke wrote a second treatise, which presented an epic case for liberty and the right of people to rebel against tyrants. While he drew his principles substantially from Tyrrell, he pushed them to their radical conclusions: namely, an explicit attack on slavery and defense of revolution.

Exile in Holland

As Charles II intensified his campaign against rebels, Shaftesbury fled to Holland in November 1682 and died there two months later. On July 21, 1683, Locke might well have seen the powers that be at Oxford University burn books they considered dangerous. It was England’s last book burning. When Locke feared his rooms would be searched, he initially hid his draft of the two treatises with Tyrrell. Locke moved out of Oxford, checked on country property he had inherited from his father, then fled to Rotterdam September 7.

The English government tried to have Locke extradited for trial and presumably execution. He moved into one Egbertus Veen’s Amsterdam house and assumed the name “Dr. van der Linden.” He signed letters as “Lamy” or “Dr. Lynne.” Anticipating that the government might intercept mail, Locke protected friends by referring to them with numbers or false names. He told people he was in Holland because he enjoyed the local beer.

Meanwhile, Charles II had converted to Catholicism before he died in February 1685. Charles’s brother became King James II, who began promoting Catholicism in England. He defied Parliament. He replaced Anglican Church officials and sheriffs with Catholics. He staffed the army with Catholic officers. He turned Oxford University’s Magdalen College into a Catholic seminary.

In Holland, Locke worked on his masterpiece, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding , which urged people to base their convictions on observation and reason. He also worked on a “letter” advocating religious toleration except for atheists (who wouldn’t swear legally binding oaths) and Catholics (loyal to a foreign power).

Catholicism loomed as the worst menace to liberty because of the shrewd French King Louis XIV. He waged war for years against England and Holland—France had a population around 20 million, about four times larger than England and 10 times larger than Holland.

On June 10, 1688, James II announced the birth of a son, and suddenly there was the specter of a Catholic succession. This convinced Tories, as English defenders of royal absolutism were known, to embrace Whig ideas of rebellion. The Dutchman William of Orange, who had married Mary, the Protestant daughter of James II, agreed to assume power in England as William III and recognize the supremacy of Parliament. On November 5, 1688, William crossed the English Channel with ships and soldiers. James II summoned English forces, but they were badly split between Catholics and Protestants. Within a month, James II fled to France. This was the “Glorious Revolution,” so-called because it helped secure Protestant succession and Parliamentary supremacy without violence.

Locke resolved to return home, but there were regrets. For example, he wrote the minister and scholar Philip van Limborch:

I almost feel as though I were leaving my own country and my own kinsfolk; for everything that belongs to kinship, good will, love, kindness—everything that binds men together with ties stronger than that of blood—I have found among you in abundance. … I seem to have found in your friendship alone enough to make me always rejoice that I was forced to pass so many years amongst you.

Locke sailed on the same ship as the soon-to-be Queen Mary, arriving in London, February 11, 1689. During the next 12 months, his major works were published, and suddenly he was famous.

A Letter Concerning Toleration

Limborch published Locke’s Epistola de Tolerantia in Gouda, Holland, in May 1689—Locke wrote in Latin presumably to reach a European audience. The work was translated as A Letter Concerning Toleration and published in October 1689. Locke did not take religious toleration as far as his Quaker compatriot William Penn—Locke was concerned about the threat atheists and Catholics might pose to the social order—but he opposed persecution. He went beyond the Toleration Act (1689), specifically calling for toleration of Anabaptists, Independents, Presbyterians, and Quakers.

“The Magistrate,” he declared,

ought not to forbid the Preaching or Professing of any Speculative Opinions in any Church, because they have no manner of relation to the Civil Rights of the Subjects. If a Roman Catholick believe that to be really the Body of Christ, which another man calls Bread, he does no injury therby to his Neighbour. If a Jew do not believe the New Testament to be the Word of God, he does not thereby alter any thing in mens Civil Rights. If a Heathen doubt of both Testaments, he is not therefore to be punished as a pernicious Citizen.

Locke’s Letter brought replies, and he wrote two further letters in 1690 and 1692.

Locke’s Two Treatises on Government

Locke’s two treatises on government were published in October 1689 with a 1690 date on the title page. While later philosophers have belittled it because Locke based his thinking on archaic notions about a “state of nature,” his bedrock principles endure. He defended the natural law tradition whose glorious lineage goes back to the ancient Jews: the tradition that rulers cannot legitimately do anything they want because there are moral laws applying to everyone.

“Reason, which is that Law,” Locke declared, “teaches all Mankind, who would but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his Life, Health, Liberty, or Possessions.” Locke envisioned a rule of law:

have a standing Rule to live by, common to every one of that Society, and made by the Legislative Power erected in it; A Liberty to follow my own Will in all things, where the Rule prescribes not; and not to be subject to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, Arbitrary Will of another Man.

Locke established that private property is absolutely essential for liberty: “every Man has a Property in his own Person . This no Body has any Right to but himself. The Labour of his Body, and the Work of his Hands, we may say, are properly his.” He continues: “The great and chief end therefore, of Mens uniting into Commonwealths, and putting themselves under Government, is the Preservation of their Property .”

Locke believed people legitimately turned common property into private property by mixing their labor with it, improving it. Marxists liked to claim this meant Locke embraced the labor theory of value, but he was talking about the basis of ownership rather than value.

He insisted that people, not rulers, are sovereign. Government, Locke wrote, “can never have a Power to take to themselves the whole or any part of the Subjects Property , without their own consent. For this would be in effect to leave them no Property at all.” He makes his point even more explicit: rulers “must not raise Taxes on the Property of the People, without the Consent of the People , given by themselves, or their Deputies.”

Locke had enormous foresight to see beyond the struggles of his own day, which were directed against monarchy:

’Tis a Mistake to think this Fault [tyranny] is proper only to Monarchies; other Forms of Government are liable to it, as well as that. For where-ever the Power that is put in any hands for the Government of the People, and the Preservation of their Properties, is applied to other ends, and made use of to impoverish, harass, or subdue them to the Arbitrary and Irregular Commands of those that have it: There it presently becomes Tyranny , whether those that thus use it are one or many.

Then Locke affirmed an explicit right to revolution:

whenever the Legislators endeavor to take away, and destroy the Property of the People , or to reduce them to Slavery under Arbitrary Power, they put themselves into a state of War with the People, who are thereupon absolved from any farther Obedience, and are left to the common Refuge, which God hath provided for all Men, against Force and Violence. Whensoever therefore the Legislative shall transgress this fundamental Rule of Society; and either by Ambition, Fear, Folly or Corruption, endeavor to grasp themselves, or put into the hands of any other an Absolute Power over the Lives, Liberties, and Estates of the People; By this breach of Trust they forfeit the Power , the People had put into their hands, for quite contrary ends, and it devolves to the People, who have a Right to resume their original Liberty.

To help assure his anonymity, he dealt with the printer through his friend Edward Clarke. Locke denied rumors that he was the author, and he begged his friends to keep their speculations to themselves. He cut off those like James Tyrrell who persisted in talking about Locke’s authorship. Locke destroyed the original manuscripts and all references to the work in his writings. His only written acknowledgment of authorship was in an addition to his will, signed shortly before he died. Ironically, the two treatises caused hardly a stir during his life.

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

Locke’s byline did appear with An Essay Concerning Human Understanding , published December 1689, and it established him as England’s leading philosopher. He challenged the traditional doctrine that learning consisted entirely of reading ancient texts and absorbing religious dogmas. He maintained that understanding the world required observation. He encouraged people to think for themselves. He urged that reason be the guide. He warned that without reason, “men’s opinions are not the product of any judgment or the consequence of reason but the effects of chance and hazard, of a mind floating at all adventures, without choice and without direction.” This book became one of the most widely reprinted and influential works on philosophy.

In 1693, Locke published Some Thoughts Concerning Education , which offered many ideas as revolutionary now as they were then. Thomas Hobbes had insisted that education should promote submission to authority, but Locke declared education is for liberty. Locke believed that setting a personal example is the most effective way to teach moral standards and fundamental skills, which is why he recommended homeschooling. He objected to government schools. He urged parents to nurture the unique genius of each child.

Locke denounced the tendency of many teachers to worship power.

All the entertainment and talk of history is of nothing almost but fighting and killing: and the honour and renown that is bestowed on conquerors (who are for the most part but the great butchers of mankind) further mislead growing youth, who … come to think slaughter the laudable business of mankind, and the most heroic of virtues.

Locke was asked by his new patron, Sir John Somers, a member of Parliament, to counter the claims of East India Company lobbyists who wanted the government to interfere with money markets. This resulted in Locke’s first published essay on economics, Some Consideration of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest, and Raising the Value of Money (1691), which appeared anonymously. He explained that market action follows natural laws and that government intervention is counterproductive. When individuals violated government laws like usury laws restricting interest rates, Locke blamed government for enacting the laws. Locke warned against debasing money and urged that the Mint issue full-weight silver coins. His view prevailed.

Locke helped expand freedom of the press. He did this by twice opposing renewal of the Act for the Regulation of Printing. The second time, in 1694, he was successful. He stressed the evils of monopoly, saying “I know not why a man should not have liberty to print whatever he would speak.”

Despite his love of liberty, Locke supported the establishment of the Bank of England in 1694. Its aim was to help the government finance wars against Louis XIV. It loaned money to the government in exchange for gaining a monopoly on dealing in gold bullion, bills of exchange, and currency. Locke, financially comfortable thanks to Shaftesbury’s investment advice, became an original subscriber.

In 1696, King William III named Locke a Commissioner on the Board of Trade, which included responsibility for managing England’s colonies, import restrictions, and poor relief. As far as the poor were concerned, according to one friend, “He was naturally compassionate and exceedingly charitable to those in want. But his charity was always directed to encourage working, laborious, industrious people, and not to relieve idle beggars.” Locke retired from the Board of Trade four years later.

Locke’s Final Years

Sir Francis Masham and his wife, Damaris, had invited Locke to spend his last years at Oates, their red brick Gothic-style manor house in North Essex, about 25 miles from London. He had a ground-floor bedroom and an adjoining study with most of his 5,000-volume library. He insisted on paying: a pound per week for his servant and himself, plus a shilling a week for his horse.

Locke gradually became infirm. He lost most of his hearing. His legs swelled up. By October 1704, he could hardly arise to dress. He broke out in sweats. Around 3 o’clock in the afternoon, Saturday, October 28, Locke was sitting in his study with Lady Masham. Suddenly, he brought his hands to his face, shut his eyes, and died. He was 72. He was buried in the High Laver churchyard.

During the 1720s, the English radical writers John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon popularized Locke’s political ideas in Cato’s Letters , a popular series of essays published in London newspapers, and these had the most direct impact on American thinkers. Locke’s influence was most apparent in the Declaration of Independence, the constitutional separation of powers, and the Bill of Rights.

Meanwhile, Voltaire had promoted Locke’s ideas in France. Ideas about the separation of powers were expanded by Baron de Montesquieu. Locke’s doctrine of natural rights appeared at the outset of the French Revolution, in the Declaration of the Rights of Man, but his belief in the separation of powers and the sanctity of private property never took hold there. Hence, the Reign of Terror.

Then Locke virtually vanished from intellectual debates. A conservative reaction engulfed Europe as people associated talk about natural rights with rebellion and Napoleon’s wars. In England, Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham ridiculed natural rights, proposing that public policy be determined by the greatest-happiness-for-the-greatest-number principle. But both conservatives and Utilitarians proved intellectually helpless when governments demanded more power to rob people, jail people, and even commit murder in the name of doing good.

During recent decades, some thinkers like novelist-philosopher Ayn Rand and economist Murray Rothbard revived a compelling moral case for liberty. They provided a meaningful moral standard for determining whether laws are just. They drew the clearest possible line beyond which neither a ruler, nor a majority, nor a bureaucrat, nor anyone else in government could legitimately go. They inspired millions as they sounded the battle cry that people everywhere are born with equal rights to life, liberty, and property. They stood on the shoulders of John Locke.

Jim Powell , senior fellow at the Cato Institute, is an expert in the history of liberty. He has lectured in England, Germany, Japan, Argentina and Brazil as well as at Harvard, Stanford and other universities across the United States. He has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Esquire, Audacity/American Heritage and other publications, and is author of six books.

More By Jim Powell

Turgot: The Man Who First Put Laissez-Faire Into Action

William Penn Was America’s First Great Champion for Liberty and Peace

How Ben Franklin Invented the American Dream

Mary Wollstonecraft: Libertarian Feminist

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, the declaration, the constitution, and the bill of rights.

by Jeffrey Rosen and David Rubenstein

At the National Constitution Center, you will find rare copies of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. These are the three most important documents in American history. But why are they important, and what are their similarities and differences? And how did each document, in turn, influence the next in America’s ongoing quest for liberty and equality?

There are some clear similarities among the three documents. All have preambles. All were drafted by people of similar backgrounds, generally educated white men of property. The Declaration and Constitution were drafted by a congress and a convention that met in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia (now known as Independence Hall) in 1776 and 1787 respectively. The Bill of Rights was proposed by the Congress that met in Federal Hall in New York City in 1789. Thomas Jefferson was the principal drafter of the Declaration and James Madison of the Bill of Rights; Madison, along with Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson, was also one of the principal architects of the Constitution.

Most importantly, the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are based on the idea that all people have certain fundamental rights that governments are created to protect. Those rights include common law rights, which come from British sources like the Magna Carta, or natural rights, which, the Founders believed, came from God. The Founders believed that natural rights are inherent in all people by virtue of their being human and that certain of these rights are unalienable, meaning they cannot be surrendered to government under any circumstances.

At the same time, the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are different kinds of documents with different purposes. The Declaration was designed to justify breaking away from a government; the Constitution and Bill of Rights were designed to establish a government. The Declaration stands on its own—it has never been amended—while the Constitution has been amended 27 times. (The first ten amendments are called the Bill of Rights.) The Declaration and Bill of Rights set limitations on government; the Constitution was designed both to create an energetic government and also to constrain it. The Declaration and Bill of Rights reflect a fear of an overly centralized government imposing its will on the people of the states; the Constitution was designed to empower the central government to preserve the blessings of liberty for “We the People of the United States.” In this sense, the Declaration and Bill of Rights, on the one hand, and the Constitution, on the other, are mirror images of each other.

Despite these similarities and differences, the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are, in many ways, fused together in the minds of Americans, because they represent what is best about America. They are symbols of the liberty that allows us to achieve success and of the equality that ensures that we are all equal in the eyes of the law. The Declaration of Independence made certain promises about which liberties were fundamental and inherent, but those liberties didn’t become legally enforceable until they were enumerated in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. In other words, the fundamental freedoms of the American people were alluded to in the Declaration of Independence, implicit in the Constitution, and enumerated in the Bill of Rights. But it took the Civil War, which President Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address called “a new birth of freedom,” to vindicate the Declaration’s famous promise that “all men are created equal.” And it took the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1868 after the Civil War, to vindicate James Madison’s initial hope that not only the federal government but also the states would be constitutionally required to respect fundamental liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights—a process that continues today.

Why did Jefferson draft the Declaration of Independence?

When the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in 1775, it was far from clear that the delegates would pass a resolution to separate from Great Britain. To persuade them, someone needed to articulate why the Americans were breaking away. Congress formed a committee to do just that; members included John Adams from Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin from Pennsylvania, Roger Sherman from Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston from New York, and Thomas Jefferson from Virginia, who at age 33 was one of the youngest delegates.

Although Jefferson disputed his account, John Adams later recalled that he had persuaded Jefferson to write the draft because Jefferson had the fewest enemies in Congress and was the best writer. (Jefferson would have gotten the job anyway—he was elected chair of the committee.) Jefferson had 17 days to produce the document and reportedly wrote a draft in a day or two. In a rented room not far from the State House, he wrote the Declaration with few books and pamphlets beside him, except for a copy of George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights and the draft Virginia Constitution, which Jefferson had written himself.

The Declaration of Independence has three parts. It has a preamble, which later became the most famous part of the document but at the time was largely ignored. It has a second part that lists the sins of the King of Great Britain, and it has a third part that declares independence from Britain and that all political connections between the British Crown and the “Free and Independent States” of America should be totally dissolved.

The preamble to the Declaration of Independence contains the entire theory of American government in a single, inspiring passage:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

When Jefferson wrote the preamble, it was largely an afterthought. Why is it so important today? It captured perfectly the essence of the ideals that would eventually define the United States. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” Jefferson began, in one of the most famous sentences in the English language. How could Jefferson write this at a time that he and other Founders who signed the Declaration owned slaves? The document was an expression of an ideal. In his personal conduct, Jefferson violated it. But the ideal—“that all men are created equal”—came to take on a life of its own and is now considered the most perfect embodiment of the American creed.

When Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address during the Civil War in November 1863, several months after the Union Army defeated Confederate forces at the Battle of Gettysburg, he took Jefferson’s language and transformed it into constitutional poetry. “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” Lincoln declared. “Four score and seven years ago” refers to the year 1776, making clear that Lincoln was referring not to the Constitution but to Jefferson’s Declaration. Lincoln believed that the “principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society,” as he wrote shortly before the anniversary of Jefferson’s birthday in 1859. Three years later, on the anniversary of George Washington’s birthday in 1861, Lincoln said in a speech at what by that time was being called “Independence Hall,” “I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender” the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

It took the Civil War, the bloodiest war in American history, for Lincoln to begin to make Jefferson’s vision of equality a constitutional reality. After the war, the Declaration’s vision was embodied in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, which formally ended slavery, guaranteed all persons the “equal protection of the laws,” and gave African-American men the right to vote. At the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, when supporters of gaining greater rights for women met, they, too, used the Declaration of Independence as a guide for drafting their Declaration of Sentiments. (Their efforts to achieve equal suffrage culminated in 1920 in the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote.) And during the civil rights movement in the 1960s, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said in his famous address at the Lincoln Memorial, “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

In addition to its promise of equality, Jefferson’s preamble is also a promise of liberty. Like the other Founders, he was steeped in the political philosophy of the Enlightenment, in philosophers such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, Francis Hutcheson, and Montesquieu. All of them believed that people have certain unalienable and inherent rights that come from God, not government, or come simply from being human. They also believed that when people form governments, they give those governments control over certain natural rights to ensure the safety and security of other rights. Jefferson, George Mason, and the other Founders frequently spoke of the same set of rights as being natural and unalienable. They included the right to worship God “according to the dictates of conscience,” the right of “enjoyment of life and liberty,” “the means of acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety,” and, most important of all, the right of a majority of the people to “alter and abolish” their government whenever it threatened to invade natural rights rather than protect them.

In other words, when Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence and began to articulate some of the rights that were ultimately enumerated in the Bill of Rights, he wasn’t inventing these rights out of thin air. On the contrary, 10 American colonies between 1606 and 1701 were granted charters that included representative assemblies and promised the colonists the basic rights of Englishmen, including a version of the promise in the Magna Carta that no freeman could be imprisoned or destroyed “except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” This legacy kindled the colonists’ hatred of arbitrary authority, which allowed the King to seize their bodies or property on his own say-so. In the revolutionary period, the galvanizing examples of government overreaching were the “general warrants” and “writs of assistance” that authorized the King’s agents to break into the homes of scores of innocent citizens in an indiscriminate search for the anonymous authors of pamphlets criticizing the King. Writs of assistance, for example, authorized customs officers “to break open doors, Chests, Trunks, and other Packages” in a search for stolen goods, without specifying either the goods to be seized or the houses to be searched. In a famous attack on the constitutionality of writs of assistance in 1761, prominent lawyer James Otis said, “It is a power that places the liberty of every man in the hands of every petty officer.”

As members of the Continental Congress contemplated independence in May and June of 1776, many colonies were dissolving their charters with England. As the actual vote on independence approached, a few colonies were issuing their own declarations of independence and bills of rights. The Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776, written by George Mason, began by declaring that “all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

When Jefferson wrote his famous preamble, he was restating, in more eloquent language, the philosophy of natural rights expressed in the Virginia Declaration that the Founders embraced. And when Jefferson said, in the first paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, that “[w]hen in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another,” he was recognizing the right of revolution that, the Founders believed, had to be exercised whenever a tyrannical government threatened natural rights. That’s what Jefferson meant when he said Americans had to assume “the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them.”

The Declaration of Independence was a propaganda document rather than a legal one. It didn’t give any rights to anyone. It was an advertisement about why the colonists were breaking away from England. Although there was no legal reason to sign the Declaration, Jefferson and the other Founders signed it because they wanted to “mutually pledge” to each other that they were bound to support it with “our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” Their signatures were courageous because the signers realized they were committing treason: according to legend, after affixing his flamboyantly large signature John Hancock said that King George—or the British ministry—would be able to read his name without spectacles. But the courage of the signers shouldn’t be overstated: the names of the signers of the Declaration weren’t published until after General George Washington won crucial battles at Trenton and Princeton and it was clear that the war for independence was going well.

What is the relationship between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution?

In the years between 1776 and 1787, most of the 13 states drafted constitutions that contained a declaration of rights within the body of the document or as a separate provision at the beginning, many of them listing the same natural rights that Jefferson had embraced in the Declaration. When it came time to form a central government in 1776, the Continental Congress began to create a weak union governed by the Articles of Confederation. (The Articles of Confederation was sent to the states for ratification in 1777; it was formally adopted in 1781.) The goal was to avoid a powerful federal government with the ability to invade rights and to threaten private property, as the King’s agents had done with the hated general warrants and writs of assistance. But the Articles of Confederation proved too weak for bringing together a fledgling nation that needed both to wage war and to manage the economy. Supporters of a stronger central government, like James Madison, lamented the inability of the government under the Articles to curb the excesses of economic populism that were afflicting the states, such as Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts, where farmers shut down the courts demanding debt relief. As a result, Madison and others gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 with the goal of creating a stronger, but still limited, federal government.

The Constitutional Convention was held in Philadelphia in the Pennsylvania State House, in the room where the Declaration of Independence was adopted. Jefferson, who was in France at the time, wasn’t among them. After four months of debate, the delegates produced a constitution.

During the final days of debate, delegates George Mason and Elbridge Gerry objected that the Constitution, too, should include a bill of rights to protect the fundamental liberties of the people against the newly empowered president and Congress. Their motion was swiftly—and unanimously—defeated; a debate over what rights to include could go on for weeks, and the delegates were tired and wanted to go home. The Constitution was approved by the Constitutional Convention and sent to the states for ratification without a bill of rights.

During the ratification process, which took around 10 months (the Constitution took effect when New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify in late June 1788; the 13th state, Rhode Island, would not join the union until May 1790), many state ratifying conventions proposed amendments specifying the rights that Jefferson had recognized in the Declaration and that they protected in their own state constitutions. James Madison and other supporters of the Constitution initially resisted the need for a bill of rights as either unnecessary (because the federal government was granted no power to abridge individual liberty) or dangerous (since it implied that the federal government had the power to infringe liberty in the first place). In the face of a groundswell of popular demand for a bill of rights, Madison changed his mind and introduced a bill of rights in Congress on June 8, 1789.

Madison was least concerned by “abuse in the executive department,” which he predicted would be the weakest branch of government. He was more worried about abuse by Congress, because he viewed the legislative branch as “the most powerful, and most likely to be abused, because it is under the least control.” (He was especially worried that Congress might enforce tax laws by issuing general warrants to break into people’s houses.) But in his view “the great danger lies rather in the abuse of the community than in the legislative body”—in other words, local majorities who would take over state governments and threaten the fundamental rights of minorities, including creditors and property holders. For this reason, the proposed amendment that Madison considered “the most valuable amendment in the whole list” would have prohibited the state governments from abridging freedom of conscience, speech, and the press, as well as trial by jury in criminal cases. Madison’s favorite amendment was eliminated by the Senate and not resurrected until after the Civil War, when the 14th Amendment required state governments to respect basic civil and economic liberties.

In the end, by pulling from the amendments proposed by state ratifying conventions and Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights, Madison proposed 19 amendments to the Constitution. Congress approved 12 amendments to be sent to the states for ratification. Only 10 of the amendments were ultimately ratified in 1791 and became the Bill of Rights. The first of the two amendments that failed was intended to guarantee small congressional districts to ensure that representatives remained close to the people. The other would have prohibited senators and representatives from giving themselves a pay raise unless it went into effect at the start of the next Congress. (This latter amendment was finally ratified in 1992 and became the 27th Amendment.)

To address the concern that the federal government might claim that rights not listed in the Bill of Rights were not protected, Madison included what became the Ninth Amendment, which says the “enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” To ensure that Congress would be viewed as a government of limited rather than unlimited powers, he included the 10th Amendment, which says the “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Because of the first Congress’s focus on protecting people from the kinds of threats to liberty they had experienced at the hands of King George, the rights listed in the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights apply only to the federal government, not to the states or to private companies. (One of the amendments submitted by the North Carolina ratifying convention but not included by Madison in his proposal to Congress would have prohibited Congress from establishing monopolies or companies with “exclusive advantages of commerce.”)

But the protections in the Bill of Rights—forbidding Congress from abridging free speech, for example, or conducting unreasonable searches and seizures—were largely ignored by the courts for the first 100 years after the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791. Like the preamble to the Declaration, the Bill of Rights was largely a promissory note. It wasn’t until the 20th century, when the Supreme Court began vigorously to apply the Bill of Rights against the states, that the document became the centerpiece of contemporary struggles over liberty and equality. The Bill of Rights became a document that defends not only majorities of the people against an overreaching federal government but also minorities against overreaching state governments. Today, there are debates over whether the federal government has become too powerful in threatening fundamental liberties. There are also debates about how to protect the least powerful in society against the tyranny of local majorities.

What do we know about the documentary history of the rare copies of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights on display at the National Constitution Center?

Generally, when people think about the original Declaration, they are referring to the official engrossed —or final—copy now in the National Archives. That is the one that John Hancock, Thomas Jefferson, and most of the other members of the Second Continental Congress signed, state by state, on August 2, 1776. John Dunlap, a Philadelphia printer, published the official printing of the Declaration ordered by Congress, known as the Dunlap Broadside, on the night of July 4th and the morning of July 5th. About 200 copies are believed to have been printed. At least 27 are known to survive.

The document on display at the National Constitution Center is known as a Stone Engraving, after the engraver William J. Stone, whom then Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned in 1820 to create a precise facsimile of the original engrossed version of the Declaration. That manuscript had become faded and worn after nearly 45 years of travel with Congress between Philadelphia, New York City, and eventually Washington, D.C., among other places, including Leesburg, Virginia, where it was rolled up and hidden during the British invasion of the capital in 1814.

To ensure that future generations would have a clear image of the original Declaration, William Stone made copies of the document before it faded away entirely. Historians dispute how Stone rendered the facsimiles. He kept the original Declaration in his shop for up to three years and may have used a process that involved taking a wet cloth, putting it on the original document, and creating a perfect copy by taking off half the ink. He would have then put the ink on a copper plate to do the etching (though he might have, instead, traced the entire document by hand without making a press copy). Stone used the copper plate to print 200 first edition engravings as well as one copy for himself in 1823, selling the plate and the engravings to the State Department. John Quincy Adams sent copies to each of the living signers of the Declaration (there were three at the time), public officials like President James Monroe, Congress, other executive departments, governors and state legislatures, and official repositories such as universities. The Stone engravings give us the clearest idea of what the original engrossed Declaration looked like on the day it was signed.

The Constitution, too, has an original engrossed, handwritten version as well as a printing of the final document. John Dunlap, who also served as the official printer of the Declaration, and his partner David C. Claypoole, who worked with him to publish the Pennsylvania Packet and Daily Advertiser , America’s first successful daily newspaper founded by Dunlap in 1771, secretly printed copies of the convention’s committee reports for the delegates to review, debate, and make changes. At the end of the day on September 15, 1787, after all of the delegations present had approved the Constitution, the convention ordered it engrossed on parchment. Jacob Shallus, assistant clerk to the Pennsylvania legislature, spent the rest of the weekend preparing the engrossed copy (now in the National Archives), while Dunlap and Claypoole were ordered to print 500 copies of the final text for distribution to the delegates, Congress, and the states. The engrossed copy was signed on Monday, September 17th, which is now celebrated as Constitution Day.

The copy of the Constitution on display at the National Constitution Center was published in Dunlap and Claypoole’s Pennsylvania Packet newspaper on September 19, 1787. Because it was the first public printing of the document—the first time Americans saw the Constitution—scholars consider its constitutional significance to be especially profound. The publication of the Constitution in the Pennsylvania Packet was the first opportunity for “We the People of the United States” to read the Constitution that had been drafted and would later be ratified in their name.

The handwritten Constitution inspires awe, but the first public printing reminds us that it was only the ratification of the document by “We the People” that made the Constitution the supreme law of the land. As James Madison emphasized in The Federalist No. 40 in 1788, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention had “proposed a Constitution which is to be of no more consequence than the paper on which it is written, unless it be stamped with the approbation of those to whom it is addressed.” Only 25 copies of the Pennsylvania Packet Constitution are known to have survived.

Finally, there is the Bill of Rights. On October 2, 1789, Congress sent 12 proposed amendments to the Constitution to the states for ratification—including the 10 that would come to be known as the Bill of Rights. There were 14 original manuscript copies, including the one displayed at the National Constitution Center—one for the federal government and one for each of the 13 states.

Twelve of the 14 copies are known to have survived. Two copies —those of the federal government and Delaware — are in the National Archives. Eight states currently have their original documents; Georgia, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania do not. There are two existing unidentified copies, one held by the Library of Congress and one held by The New York Public Library. The copy on display at the National Constitution Center is from the collections of The New York Public Library and will be on display for several years through an agreement between the Library and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania; the display coincides with the 225th anniversary of the proposal and ratification of the Bill of Rights.

The Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are the three most important documents in American history because they express the ideals that define “We the People of the United States” and inspire free people around the world.

Read More About the Constitution

The constitutional convention of 1787: a revolution in government, on originalism in constitutional interpretation, democratic constitutionalism, modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

This essay delves into the profound significance of the phrase “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” within the American ethos. Rooted in the Declaration of Independence, these words embody the core values shaping the nation. The concept of “life” extends beyond mere existence, emphasizing the right to lead a meaningful and fulfilling life, fundamental to the American dream. “Liberty” reflects the ongoing narrative of freedom, from colonial struggles to civil rights movements, highlighting the pursuit of individual rights free from oppressive constraints. The essay concludes with a reflection on the dynamic nature of America’s commitment to these ideals, evolving with societal changes and expanding to address contemporary challenges such as climate change and social justice. Ultimately, “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” serve as keystones in an ongoing conversation, inspiring Americans to navigate present challenges while aspiring to build a more inclusive and fulfilling society for future generations. Additionally, PapersOwl presents more free essays samples linked to Life.

How it works

In the pantheon of American ideals, few phrases resonate as deeply as “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” These words, immortalized in the Declaration of Independence, encapsulate the core values that have shaped the American spirit and continue to influence the nation’s ethos.

At its heart, the concept of “life” in this trinity represents more than mere existence. It encompasses the right to live a meaningful and fulfilling life—one that transcends the basic necessities of survival. Americans cherish the freedom to pursue their passions, to create, and to carve out a unique identity.

This liberty to navigate the journey of life according to one’s values is at the very foundation of the American dream.

Liberty, the second pillar of this triad, embodies the freedom from oppressive constraints and the ability to exercise individual rights. America’s history is punctuated by struggles for freedom, from the fight against colonial rule to the civil rights movements that sought to dismantle racial segregation. The pursuit of liberty is an ongoing narrative, a story etched in the struggles of individuals who fought and continue to fight for the right to live unencumbered by undue restrictions.

The pursuit of happiness, the crowning jewel in this trio, lends a distinctive flavor to the American dream. It acknowledges that happiness is not just a desirable outcome but a noble pursuit in itself. It recognizes the diversity of human aspirations and the multitude of paths individuals may choose to find fulfillment. From the artist seeking creative expression to the entrepreneur pursuing innovation, the pursuit of happiness empowers individuals to shape their destiny and contribute to the collective mosaic of American society.

America’s commitment to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is a dynamic force that evolves with the times. In the 21st century, the pursuit of happiness extends beyond personal endeavors to encompass a broader societal responsibility. As the nation grapples with issues like climate change, social justice, and economic inequality, the concept of happiness expands to include the well-being of future generations and the sustainability of the planet.

The American experiment has not been without its challenges, and the quest for a balance between individual freedom and collective responsibility continues. Striking this delicate equilibrium is a perpetual work in progress—a journey as essential as the destination. The interplay of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is not a static formula but a dynamic equation, responsive to the evolving needs of a society that seeks to uphold its foundational principles while adapting to the complexities of a changing world.

In conclusion, “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” are not mere words; they are the keystones of the American identity. They represent an ongoing conversation about the nature of freedom, the essence of a meaningful life, and the pursuit of individual and collective fulfillment. As Americans navigate the challenges of the present and the uncertainties of the future, the enduring ideals encapsulated in this triad continue to shape the nation’s character and inspire its people to strive for a better, more inclusive, and fulfilling society.

Cite this page

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness. (2024, Jan 26). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/life-liberty-and-the-pursuit-of-happiness/

"Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness." PapersOwl.com , 26 Jan 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/life-liberty-and-the-pursuit-of-happiness/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/life-liberty-and-the-pursuit-of-happiness/ [Accessed: 8 Jun. 2024]

"Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness." PapersOwl.com, Jan 26, 2024. Accessed June 8, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/life-liberty-and-the-pursuit-of-happiness/

"Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness," PapersOwl.com , 26-Jan-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/life-liberty-and-the-pursuit-of-happiness/. [Accessed: 8-Jun-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/life-liberty-and-the-pursuit-of-happiness/ [Accessed: 8-Jun-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

The Pursuit of Happiness

What most people don’t know, however, is that Locke’s concept of happiness was majorly influenced by the Greek philosophers, Aristotle and Epicurus in particular. Far from simply equating “happiness” with “pleasure,” “property,” or the satisfaction of desire, Locke distinguishes between “imaginary” happiness and “true happiness.” Thus, in the passage where he coins the phrase “pursuit of happiness,” Locke writes:

“ The necessity of pursuing happiness [is] the foundation of liberty . As therefore the highest perfection of intellectual nature lies in a careful and constant pursuit of true and solid happiness ; so the care of ourselves, that we mistake not imaginary for real happiness, is the necessary foundation of our liberty. The stronger ties we have to an unalterable pursuit of happiness in general, which is our greatest good, and which, as such, our desires always follow, the more are we free from any necessary determination of our will to any particular action…” (1894, p. 348)

In this passage, Locke indicates that the pursuit of happiness is the foundation of liberty since it frees us from attachment to any particular desire we might have at a given moment. So, for example, although my body might present me with a strong urge to indulge in that chocolate brownie, my reason knows that ultimately the brownie is not in my best interest. Why not? Because it will not lead to my “true and solid” happiness which indicates the overall quality or satisfaction with life. If we go back to Locke, then, we see that the “pursuit of happiness” as envisaged by him and by Jefferson was not merely the pursuit of pleasure, property, or self-interest (although it does include all of these). It is also the freedom to be able to make decisions that results in the best life possible for a human being, which includes intellectual and moral effort. We would all do well to keep this in mind when we begin to discuss the “American” concept of happiness.

Read full passage from An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

A little Background

John Locke (1632-1704) was one of the great English philosophers, making important contributions in both epistemology and political philosophy. His An Essay Concerning Human Understanding , published in 1681, laid the foundation for modern empiricism, which holds that all knowledge derives from sensory experience and that man is born a “blank slate” or tabula rasa . His two Treatises of Government helped to pave the way for the French and American revolutions. Indeed, Voltaire simply called him “le sage Locke” and key parts of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America are lifted from his political writings. Thomas Jefferson once said that “Bacon, Locke and Newton are the greatest three people who ever lived, without exception.” Perhaps his greatest contribution consists in his argument for natural rights to life, liberty, and property which precede the existence of the state. Modern-day libertarians hail Locke as their intellectual hero.

Happiness as “True Pleasure”

In his An Essay Concerning Human Understanding , Locke attempted to do for the mind what Newton had done for the physical world: give a completely mechanical explanation for its operations by discovering the laws that govern its behavior. Thus he explains the processes by which ideas are abstracted from the impressions received by the mind through sense-perception. As an empiricist, Locke claims that the mind begins with a completely blank slate, and is formed solely through experience and education. The doctrines of innate ideas and original sin are brushed aside as relics of a pre-Newtonian mythological worldview. There is no such thing as human nature being originally good or evil: these are concepts that get developed only on the basis of experiencing pain and pleasure.

When it comes to Locke’s concept of happiness, he is mainly influenced by the Greek philosopher Epicurus , as interpreted by the 17th Century mathematician Pierre Gassendi. As he writes:

If it be farther asked, what moves desire? I answer happiness and that alone. Happiness and Misery are the names of two extremes, the utmost bound where we know not…But of some degrees of both, we have very lively impressions, made by several instances of Delight and Joy on the one side and Torment and Sorrow on the other; which, for shortness sake, I shall comprehend under the names of Pleasure and Pain, there being pleasure and pain of the Mind as well as the Body…Happiness then in its full extent is the utmost Pleasure we are capable of, and Misery the utmost pain. (1894, p.258)

Like Epicurus, however, Locke goes on to qualify this assertion, since there is an important distinction between “true pleasures and “false pleasures.” False pleasures are those that promise immediate gratification but are typically followed by more pain. Locke gives the example of alcohol, which promises short term euphoria but is accompanied by unhealthy affects on the mind and body. Most people are simply irrational in their pursuit of short-term pleasures, and do not choose those activities which would really give them a more lasting satisfaction. Thus Locke is led to make a distinction between “imaginary” and “real” happiness:

“ The necessity of pursuing happiness [is] the foundation of liberty . As therefore the highest perfection of intellectual nature lies in a careful and constant pursuit of true and solid happiness ; so the care of ourselves, that we mistake not imaginary for real happiness, is the necessary foundation of our liberty. The stronger ties we have to an unalterable pursuit of happiness in general, which is our greatest good, and which, as such, our desires always follow, the more are we free from any necessary determination of our will to any particular action…” (1894, p. 348)

In this passage Locke makes a very interesting observation regarding the “pursuit of happiness” and human liberty. He points out that happiness is the foundation of liberty, insofar as it enables us to use our reason to make decisions that are in our long-term best-interest, as opposed to those that simply afford us immediate gratification. Thus we are able to abstain from that glass of wine, or decide to help a friend even when we would rather stay at home and watch television. Unlike the animals which are completely enslaved to their passions , our pursuit of happiness enables us to rise above the dictates of nature. As such, the pursuit of happiness is the foundation of morality and civilization. If we had no desire for happiness, Locke suggests, we would have remained in the state of nature just content with simple pleasures like eating and sleeping. But the desire for happiness pushes us onward, to greater and higher pleasures. All of this is driven by a fundamental sense of the “uneasiness of desire” which compels us to fulfill ourselves in ever new and more expansive ways.

Everlasting Happiness

If Locke had stopped here, he would be unique among the philosophers in claiming that there is no prescription for achieving happiness, given the diversity of views about what causes happiness. For some people, reading philosophy is pleasurable whereas for others, playing football or having sex is the most pleasurable activity. Since the only standard is pleasure, there would be no way to judge that one pleasure is better than another. The only judge of what happiness is would be oneself.

But Locke does not stop there. Indeed, he notes that there is one fear that we all have deep within, the fear of death. We have a sense that if death is the end, then everything that we do will have been in vain. But if death is not the end, if there is hope for an afterlife, then that changes everything. If we continue to exist after we die, then we should act in such ways so as to produce a continuing happiness for us in the afterlife. Just as we abstain from eating the chocolate brownie because we know its not ultimately in our self-interest, we should abstain from all acts of immorality, knowing that there will be a “payback” in the next life. Thus we should act virtuously in order to ensure everlasting happiness:

“When infinite Happiness is put in one scale, against infinite Misery in the other; if the worst that comes to a Pious Man if he mistakes, be the best that the wicked can attain to, if he be in the right, Who can without madness run the venture?”

Basically, then, Locke treats the question of human happiness as a kind of gambling proposition. We want to bet on the horse that has the best chance of creating happiness for us. But if we bet on hedonism, we run the risk of suffering everlasting misery . No rational person would wish that state for oneself. Thus, it is rational to bet on the Christian horse and live the life of virtue , clearly, outlining a connection between spirituality, or religion, and happiness, with the perspective conditional on Christianity instead of religion or any other specific religion. At worst, we will sacrifice some pleasures in this life. But at best, we will win that everlasting prize at happiness which the Bible assures us. “Happy are those who are righteous, for they shall see God,” as Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount tells us.

In contrast to Thomas Aquinas , who made a pretty firm distinction between the “imperfect happiness” of life on earth and the “perfect happiness” of life in heaven, Locke maintains that there is continuity. The pleasures we experience now are “very lively impressions” and give us a sweet foretaste of the pleasures we will experience in heaven. Happiness, then, is not some vague chimera that we chasing after, nor can we really be deluded about whether we are happy or not. We know what it is to experience pleasure and pain, and thus we know what we will experience in the afterlife.

Happiness and Political Liberty

The relation between Locke’s political views and his view of happiness should be pretty clear from what has been said. Since God has given each person the desire to pursue happiness as a law of nature, the government should not try to interfere with an individual’s pursuit of happiness. Thus we have to give each person liberty: the freedom to live as he pleases, the freedom to experience his or her own kind of happiness so long as that freedom is compatible with the freedom of others to do likewise. Thus we derive the basic right of liberty from the right to pursue happiness. Even though Locke believed the path of virtue to be the “best bet” towards everlasting happiness, the government should not prescribe any particular path to happiness. First of all, it is impossible to compel virtue since it must be freely chosen by the individual. Furthermore, history has shown that attempts to impose happiness upon the people invariably result in profound unhappiness. Locke’s viewpoint here is prophetic when we look at the failure of 20 th Century attempts to achieve utopia, whether through Fascism, Communism, or Nationalism.

Locke’s view of happiness includes the following elements:

- The desire for happiness is a natural law that is implanted into us by God and motivates everything we do.

- Happiness is synonymous with pleasure, Unhappiness with pain

- We must distinguish “false pleasures” which promise immediate gratification but produce long-term pain from “true pleasures” which are intense and long lasting

- The pursuit of happiness is the foundation of individual liberty, since it gives us the ability to make decisions that are in our long-term best interest

- Since there is a diversity of natures, what causes happiness completely depends on the individual and his or her own experience of pleasure and pain

- The best bet would be to live a life of virtue so one can win everlasting happiness. Betting on a life of hedonistic pleasure is “irrational” given the prospect of infinite misery

- The pursuit of happiness is also the foundation of political liberty. Since God has given everyone the desire to pursue happiness as a natural right, the government should not interfere with anyone’s pursuit of happiness so long as it doesn’t interfere with other’s right to pursue happiness.

Further Readings

There are other philosopher that can help you to improve your happiness:

- Socrates on Happiness

- Confucius on Happiness

- Mencius and Happiness

Start Your Journey to Happiness. Register Now!

Pursuit-of-Happiness.org ©2024

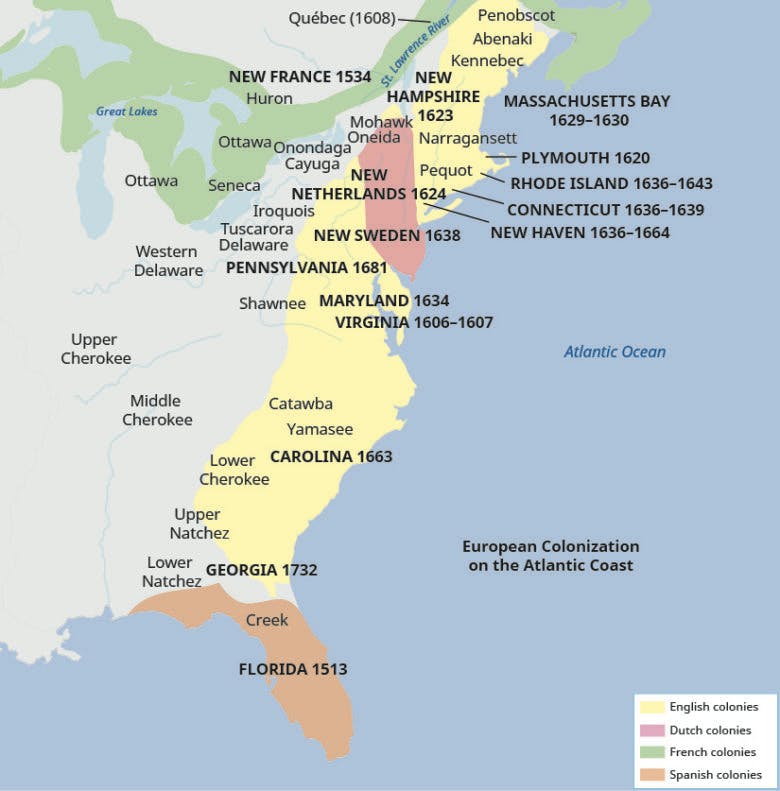

Chapter 2 Introductory Essay: 1607-1763

Written by: W.E. White, Christopher Newport University

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the context for the colonization of North America from 1607 to 1754

Introduction

The sixteenth-century brought changes in Europe that helped reshape the whole Atlantic world of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. These events were the rise of nation states, the splintering of the Christian church into Catholic and Protestant sects, and a fierce competition for global commerce. Spain aggressively protected its North American territorial claims against imperial rivals, for example. When French Protestant Huguenots established Fort Caroline (Jacksonville, Florida, today) in 1564, Spain attacked and killed the settlers the following year. France, Britain, and Holland wanted their own American colonies, and privateers from these countries used safe havens along the coast of North America to raid Spanish treasure ships. But North America did not hold the gold and silver found in Spanish possessions in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Peru. In the end, Spain concentrated on these more profitable portions of its empire, and other European nation states began to establish their own claims in North America.

Europe’s political, religious, and economic rivalries were fought in both European wars and in a struggle for colonies throughout the Atlantic. England’s Queen Elizabeth I supported Protestant revolts in Catholic France and the Spanish Netherlands, which put her at odds with Spain’s Catholic monarch, Philip II. So did her support for English privateers such as Sir Frances Drake, Sir George Summers, and Captain Christopher Newport, who preyed on Spanish treasure ships and commerce. In 1584, Elizabeth ignored the Spanish claim to all of North America and issued a royal charter to Sir Walter Raleigh, encouraging him and a group of investors to explore, colonize, and rule the continent.

Sixteenth-century Europe was defined by the rise of nation-states and the division of Christianity due to the Protestant Reformation. Increased competition for wealth fueled by both developments spilled over into the New World, and by the early seventeenth century, Spain, Portugal, England, France, and the Netherlands all had a presence in North America.

England, France, and the Netherlands

By 1600, the stage had been set for competition between the European nations colonizing the Americas, and several quickly established footholds. The Spanish founded St. Augustine (in what is now Florida) in 1565. In 1607, English adventurers arrived at Jamestown in the Virginia colony (see The English Come to America Narrative).

The French established Quebec in what today is Canada, in 1608. Spanish Santa Fe (in what is now New Mexico) was founded in 1610. The Dutch established Albany (now the capital of New York) as a trading center on the Hudson River in 1614, and New Amsterdam (called New York City today) in 1624. English Separatists, now known as Pilgrims, established Plymouth Colony in 1620. Ten years later, in 1630, Puritans established the Massachusetts Bay Colony. European settlement grew exponentially. Seventeenth-century North America became a place where diverse nations—European and Native American—came into close contact.

By the 1650s, the English, French, and Dutch were well established in North America. French traders used the waterways to move ever deeper into the interior of the continent from their toehold in Quebec, trading with American Indians. French Jesuit priests lived peacefully with American Indians, learned their languages, recorded their society norms and customs, and worked to convert them to Christianity. Europeans traded imported goods to American Indians for beaver and other furs that brought high profits in Europe (see The Fur Trade Narrative). The American Indians’ economy and culture, and relationships with other native tribes, were changed by their new focus on the fur trade and by the metal tools and firearms the Europeans offered. By the mid-1700s, the French had claimed the St. Lawrence River Valley, the Great Lakes region, and the whole of the Mississippi River Valley.