Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods

Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on August 20, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analyzing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps:

- Determine who will participate in the survey

- Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person)

- Design the survey questions and layout

- Distribute the survey

- Analyze the responses

- Write up the results

Surveys are a flexible method of data collection that can be used in many different types of research .

Table of contents

What are surveys used for, step 1: define the population and sample, step 2: decide on the type of survey, step 3: design the survey questions, step 4: distribute the survey and collect responses, step 5: analyze the survey results, step 6: write up the survey results, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about surveys.

Surveys are used as a method of gathering data in many different fields. They are a good choice when you want to find out about the characteristics, preferences, opinions, or beliefs of a group of people.

Common uses of survey research include:

- Social research : investigating the experiences and characteristics of different social groups

- Market research : finding out what customers think about products, services, and companies

- Health research : collecting data from patients about symptoms and treatments

- Politics : measuring public opinion about parties and policies

- Psychology : researching personality traits, preferences and behaviours

Surveys can be used in both cross-sectional studies , where you collect data just once, and in longitudinal studies , where you survey the same sample several times over an extended period.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Before you start conducting survey research, you should already have a clear research question that defines what you want to find out. Based on this question, you need to determine exactly who you will target to participate in the survey.

Populations

The target population is the specific group of people that you want to find out about. This group can be very broad or relatively narrow. For example:

- The population of Brazil

- US college students

- Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands

- Customers of a specific company aged 18-24

- British transgender women over the age of 50

Your survey should aim to produce results that can be generalized to the whole population. That means you need to carefully define exactly who you want to draw conclusions about.

Several common research biases can arise if your survey is not generalizable, particularly sampling bias and selection bias . The presence of these biases have serious repercussions for the validity of your results.

It’s rarely possible to survey the entire population of your research – it would be very difficult to get a response from every person in Brazil or every college student in the US. Instead, you will usually survey a sample from the population.

The sample size depends on how big the population is. You can use an online sample calculator to work out how many responses you need.

There are many sampling methods that allow you to generalize to broad populations. In general, though, the sample should aim to be representative of the population as a whole. The larger and more representative your sample, the more valid your conclusions. Again, beware of various types of sampling bias as you design your sample, particularly self-selection bias , nonresponse bias , undercoverage bias , and survivorship bias .

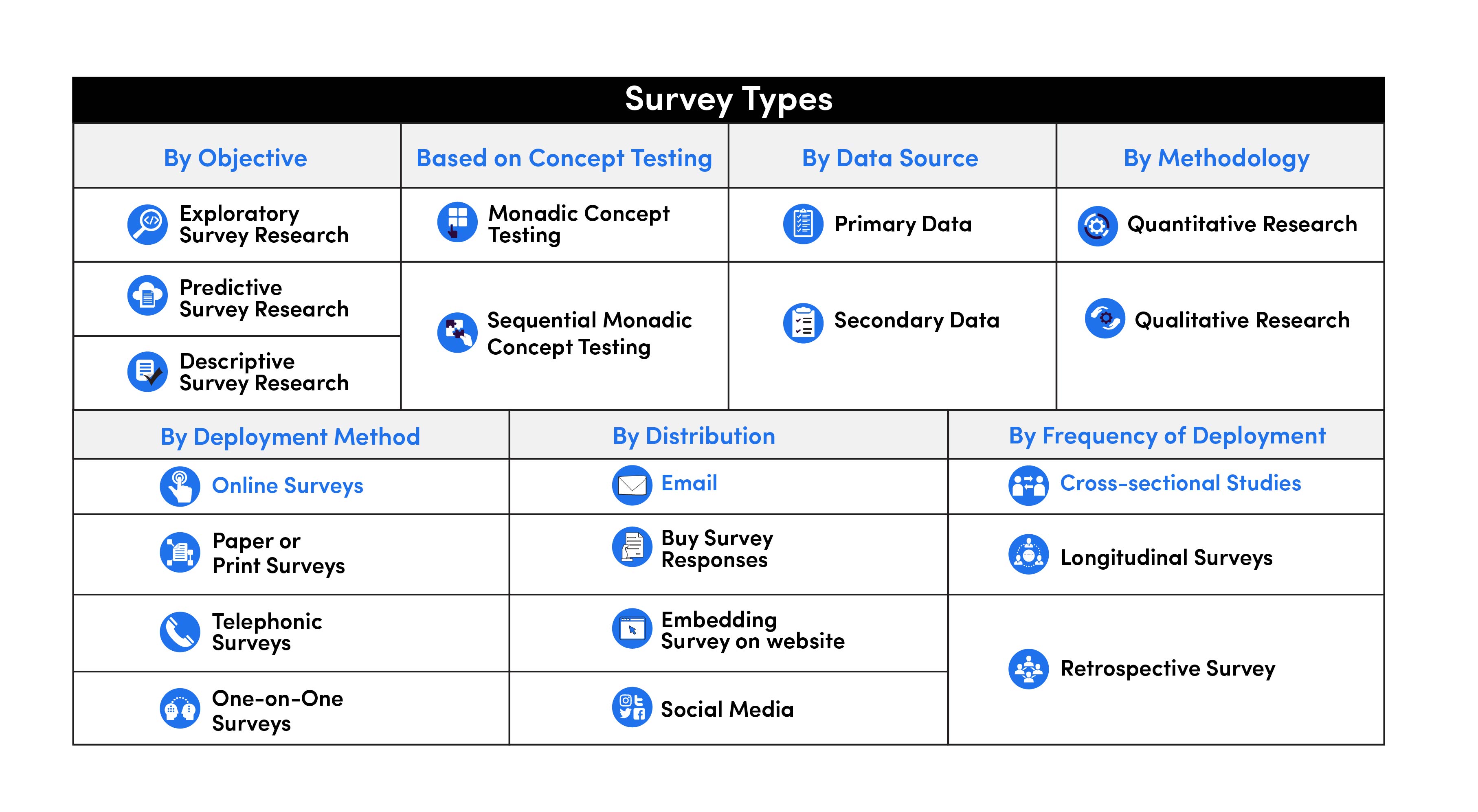

There are two main types of survey:

- A questionnaire , where a list of questions is distributed by mail, online or in person, and respondents fill it out themselves.

- An interview , where the researcher asks a set of questions by phone or in person and records the responses.

Which type you choose depends on the sample size and location, as well as the focus of the research.

Questionnaires

Sending out a paper survey by mail is a common method of gathering demographic information (for example, in a government census of the population).

- You can easily access a large sample.

- You have some control over who is included in the sample (e.g. residents of a specific region).

- The response rate is often low, and at risk for biases like self-selection bias .

Online surveys are a popular choice for students doing dissertation research , due to the low cost and flexibility of this method. There are many online tools available for constructing surveys, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms .

- You can quickly access a large sample without constraints on time or location.

- The data is easy to process and analyze.

- The anonymity and accessibility of online surveys mean you have less control over who responds, which can lead to biases like self-selection bias .

If your research focuses on a specific location, you can distribute a written questionnaire to be completed by respondents on the spot. For example, you could approach the customers of a shopping mall or ask all students to complete a questionnaire at the end of a class.

- You can screen respondents to make sure only people in the target population are included in the sample.

- You can collect time- and location-specific data (e.g. the opinions of a store’s weekday customers).

- The sample size will be smaller, so this method is less suitable for collecting data on broad populations and is at risk for sampling bias .

Oral interviews are a useful method for smaller sample sizes. They allow you to gather more in-depth information on people’s opinions and preferences. You can conduct interviews by phone or in person.

- You have personal contact with respondents, so you know exactly who will be included in the sample in advance.

- You can clarify questions and ask for follow-up information when necessary.

- The lack of anonymity may cause respondents to answer less honestly, and there is more risk of researcher bias.

Like questionnaires, interviews can be used to collect quantitative data: the researcher records each response as a category or rating and statistically analyzes the results. But they are more commonly used to collect qualitative data : the interviewees’ full responses are transcribed and analyzed individually to gain a richer understanding of their opinions and feelings.

Next, you need to decide which questions you will ask and how you will ask them. It’s important to consider:

- The type of questions

- The content of the questions

- The phrasing of the questions

- The ordering and layout of the survey

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

There are two main forms of survey questions: open-ended and closed-ended. Many surveys use a combination of both.

Closed-ended questions give the respondent a predetermined set of answers to choose from. A closed-ended question can include:

- A binary answer (e.g. yes/no or agree/disagree )

- A scale (e.g. a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree )

- A list of options with a single answer possible (e.g. age categories)

- A list of options with multiple answers possible (e.g. leisure interests)

Closed-ended questions are best for quantitative research . They provide you with numerical data that can be statistically analyzed to find patterns, trends, and correlations .

Open-ended questions are best for qualitative research. This type of question has no predetermined answers to choose from. Instead, the respondent answers in their own words.

Open questions are most common in interviews, but you can also use them in questionnaires. They are often useful as follow-up questions to ask for more detailed explanations of responses to the closed questions.

The content of the survey questions

To ensure the validity and reliability of your results, you need to carefully consider each question in the survey. All questions should be narrowly focused with enough context for the respondent to answer accurately. Avoid questions that are not directly relevant to the survey’s purpose.

When constructing closed-ended questions, ensure that the options cover all possibilities. If you include a list of options that isn’t exhaustive, you can add an “other” field.

Phrasing the survey questions

In terms of language, the survey questions should be as clear and precise as possible. Tailor the questions to your target population, keeping in mind their level of knowledge of the topic. Avoid jargon or industry-specific terminology.

Survey questions are at risk for biases like social desirability bias , the Hawthorne effect , or demand characteristics . It’s critical to use language that respondents will easily understand, and avoid words with vague or ambiguous meanings. Make sure your questions are phrased neutrally, with no indication that you’d prefer a particular answer or emotion.

Ordering the survey questions

The questions should be arranged in a logical order. Start with easy, non-sensitive, closed-ended questions that will encourage the respondent to continue.

If the survey covers several different topics or themes, group together related questions. You can divide a questionnaire into sections to help respondents understand what is being asked in each part.

If a question refers back to or depends on the answer to a previous question, they should be placed directly next to one another.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Before you start, create a clear plan for where, when, how, and with whom you will conduct the survey. Determine in advance how many responses you require and how you will gain access to the sample.

When you are satisfied that you have created a strong research design suitable for answering your research questions, you can conduct the survey through your method of choice – by mail, online, or in person.

There are many methods of analyzing the results of your survey. First you have to process the data, usually with the help of a computer program to sort all the responses. You should also clean the data by removing incomplete or incorrectly completed responses.

If you asked open-ended questions, you will have to code the responses by assigning labels to each response and organizing them into categories or themes. You can also use more qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis , which is especially suitable for analyzing interviews.

Statistical analysis is usually conducted using programs like SPSS or Stata. The same set of survey data can be subject to many analyses.

Finally, when you have collected and analyzed all the necessary data, you will write it up as part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper .

In the methodology section, you describe exactly how you conducted the survey. You should explain the types of questions you used, the sampling method, when and where the survey took place, and the response rate. You can include the full questionnaire as an appendix and refer to it in the text if relevant.

Then introduce the analysis by describing how you prepared the data and the statistical methods you used to analyze it. In the results section, you summarize the key results from your analysis.

In the discussion and conclusion , you give your explanations and interpretations of these results, answer your research question, and reflect on the implications and limitations of the research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analyzing data from people using questionnaires.

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviors. It is made up of 4 or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with 5 or 7 possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyze your data.

The priorities of a research design can vary depending on the field, but you usually have to specify:

- Your research questions and/or hypotheses

- Your overall approach (e.g., qualitative or quantitative )

- The type of design you’re using (e.g., a survey , experiment , or case study )

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods (e.g., questionnaires , observations)

- Your data collection procedures (e.g., operationalization , timing and data management)

- Your data analysis methods (e.g., statistical tests or thematic analysis )

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/survey-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, questionnaire design | methods, question types & examples, what is a likert scale | guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analysing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps:

- Determine who will participate in the survey

- Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person)

- Design the survey questions and layout

- Distribute the survey

- Analyse the responses

- Write up the results

Surveys are a flexible method of data collection that can be used in many different types of research .

Table of contents

What are surveys used for, step 1: define the population and sample, step 2: decide on the type of survey, step 3: design the survey questions, step 4: distribute the survey and collect responses, step 5: analyse the survey results, step 6: write up the survey results, frequently asked questions about surveys.

Surveys are used as a method of gathering data in many different fields. They are a good choice when you want to find out about the characteristics, preferences, opinions, or beliefs of a group of people.

Common uses of survey research include:

- Social research: Investigating the experiences and characteristics of different social groups

- Market research: Finding out what customers think about products, services, and companies

- Health research: Collecting data from patients about symptoms and treatments

- Politics: Measuring public opinion about parties and policies

- Psychology: Researching personality traits, preferences, and behaviours

Surveys can be used in both cross-sectional studies , where you collect data just once, and longitudinal studies , where you survey the same sample several times over an extended period.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Before you start conducting survey research, you should already have a clear research question that defines what you want to find out. Based on this question, you need to determine exactly who you will target to participate in the survey.

Populations

The target population is the specific group of people that you want to find out about. This group can be very broad or relatively narrow. For example:

- The population of Brazil

- University students in the UK

- Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands

- Customers of a specific company aged 18 to 24

- British transgender women over the age of 50

Your survey should aim to produce results that can be generalised to the whole population. That means you need to carefully define exactly who you want to draw conclusions about.

It’s rarely possible to survey the entire population of your research – it would be very difficult to get a response from every person in Brazil or every university student in the UK. Instead, you will usually survey a sample from the population.

The sample size depends on how big the population is. You can use an online sample calculator to work out how many responses you need.

There are many sampling methods that allow you to generalise to broad populations. In general, though, the sample should aim to be representative of the population as a whole. The larger and more representative your sample, the more valid your conclusions.

There are two main types of survey:

- A questionnaire , where a list of questions is distributed by post, online, or in person, and respondents fill it out themselves

- An interview , where the researcher asks a set of questions by phone or in person and records the responses

Which type you choose depends on the sample size and location, as well as the focus of the research.

Questionnaires

Sending out a paper survey by post is a common method of gathering demographic information (for example, in a government census of the population).

- You can easily access a large sample.

- You have some control over who is included in the sample (e.g., residents of a specific region).

- The response rate is often low.

Online surveys are a popular choice for students doing dissertation research , due to the low cost and flexibility of this method. There are many online tools available for constructing surveys, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms .

- You can quickly access a large sample without constraints on time or location.

- The data is easy to process and analyse.

- The anonymity and accessibility of online surveys mean you have less control over who responds.

If your research focuses on a specific location, you can distribute a written questionnaire to be completed by respondents on the spot. For example, you could approach the customers of a shopping centre or ask all students to complete a questionnaire at the end of a class.

- You can screen respondents to make sure only people in the target population are included in the sample.

- You can collect time- and location-specific data (e.g., the opinions of a shop’s weekday customers).

- The sample size will be smaller, so this method is less suitable for collecting data on broad populations.

Oral interviews are a useful method for smaller sample sizes. They allow you to gather more in-depth information on people’s opinions and preferences. You can conduct interviews by phone or in person.

- You have personal contact with respondents, so you know exactly who will be included in the sample in advance.

- You can clarify questions and ask for follow-up information when necessary.

- The lack of anonymity may cause respondents to answer less honestly, and there is more risk of researcher bias.

Like questionnaires, interviews can be used to collect quantitative data : the researcher records each response as a category or rating and statistically analyses the results. But they are more commonly used to collect qualitative data : the interviewees’ full responses are transcribed and analysed individually to gain a richer understanding of their opinions and feelings.

Next, you need to decide which questions you will ask and how you will ask them. It’s important to consider:

- The type of questions

- The content of the questions

- The phrasing of the questions

- The ordering and layout of the survey

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

There are two main forms of survey questions: open-ended and closed-ended. Many surveys use a combination of both.

Closed-ended questions give the respondent a predetermined set of answers to choose from. A closed-ended question can include:

- A binary answer (e.g., yes/no or agree/disagree )

- A scale (e.g., a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree )

- A list of options with a single answer possible (e.g., age categories)

- A list of options with multiple answers possible (e.g., leisure interests)

Closed-ended questions are best for quantitative research . They provide you with numerical data that can be statistically analysed to find patterns, trends, and correlations .

Open-ended questions are best for qualitative research. This type of question has no predetermined answers to choose from. Instead, the respondent answers in their own words.

Open questions are most common in interviews, but you can also use them in questionnaires. They are often useful as follow-up questions to ask for more detailed explanations of responses to the closed questions.

The content of the survey questions

To ensure the validity and reliability of your results, you need to carefully consider each question in the survey. All questions should be narrowly focused with enough context for the respondent to answer accurately. Avoid questions that are not directly relevant to the survey’s purpose.

When constructing closed-ended questions, ensure that the options cover all possibilities. If you include a list of options that isn’t exhaustive, you can add an ‘other’ field.

Phrasing the survey questions

In terms of language, the survey questions should be as clear and precise as possible. Tailor the questions to your target population, keeping in mind their level of knowledge of the topic.

Use language that respondents will easily understand, and avoid words with vague or ambiguous meanings. Make sure your questions are phrased neutrally, with no bias towards one answer or another.

Ordering the survey questions

The questions should be arranged in a logical order. Start with easy, non-sensitive, closed-ended questions that will encourage the respondent to continue.

If the survey covers several different topics or themes, group together related questions. You can divide a questionnaire into sections to help respondents understand what is being asked in each part.

If a question refers back to or depends on the answer to a previous question, they should be placed directly next to one another.

Before you start, create a clear plan for where, when, how, and with whom you will conduct the survey. Determine in advance how many responses you require and how you will gain access to the sample.

When you are satisfied that you have created a strong research design suitable for answering your research questions, you can conduct the survey through your method of choice – by post, online, or in person.

There are many methods of analysing the results of your survey. First you have to process the data, usually with the help of a computer program to sort all the responses. You should also cleanse the data by removing incomplete or incorrectly completed responses.

If you asked open-ended questions, you will have to code the responses by assigning labels to each response and organising them into categories or themes. You can also use more qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis , which is especially suitable for analysing interviews.

Statistical analysis is usually conducted using programs like SPSS or Stata. The same set of survey data can be subject to many analyses.

Finally, when you have collected and analysed all the necessary data, you will write it up as part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper .

In the methodology section, you describe exactly how you conducted the survey. You should explain the types of questions you used, the sampling method, when and where the survey took place, and the response rate. You can include the full questionnaire as an appendix and refer to it in the text if relevant.

Then introduce the analysis by describing how you prepared the data and the statistical methods you used to analyse it. In the results section, you summarise the key results from your analysis.

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviours. It is made up of four or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with five or seven possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyse your data.

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analysing data from people using questionnaires.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/surveys/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a likert scale | guide & examples.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- French Abstracts

- Portuguese Abstracts

- Spanish Abstracts

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal for Quality in Health Care

- About the International Society for Quality in Health Care

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ISQua

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

What is survey research, advantages and disadvantages of survey research, essential steps in survey research, research methods, designing the research tool, sample and sampling, data collection, data analysis.

- < Previous

Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

KATE KELLEY, BELINDA CLARK, VIVIENNE BROWN, JOHN SITZIA, Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research, International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 15, Issue 3, May 2003, Pages 261–266, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzg031

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Survey research is sometimes regarded as an easy research approach. However, as with any other research approach and method, it is easy to conduct a survey of poor quality rather than one of high quality and real value. This paper provides a checklist of good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Its purpose is to assist the novice researcher to produce survey work to a high standard, meaning a standard at which the results will be regarded as credible. The paper first provides an overview of the approach and then guides the reader step-by-step through the processes of data collection, data analysis, and reporting. It is not intended to provide a manual of how to conduct a survey, but rather to identify common pitfalls and oversights to be avoided by researchers if their work is to be valid and credible.

Survey research is common in studies of health and health services, although its roots lie in the social surveys conducted in Victorian Britain by social reformers to collect information on poverty and working class life (e.g. Charles Booth [ 1 ] and Joseph Rowntree [ 2 ]), and indeed survey research remains most used in applied social research. The term ‘survey’ is used in a variety of ways, but generally refers to the selection of a relatively large sample of people from a pre-determined population (the ‘population of interest’; this is the wider group of people in whom the researcher is interested in a particular study), followed by the collection of a relatively small amount of data from those individuals. The researcher therefore uses information from a sample of individuals to make some inference about the wider population.

Data are collected in a standardized form. This is usually, but not necessarily, done by means of a questionnaire or interview. Surveys are designed to provide a ‘snapshot of how things are at a specific time’ [ 3 ]. There is no attempt to control conditions or manipulate variables; surveys do not allocate participants into groups or vary the treatment they receive. Surveys are well suited to descriptive studies, but can also be used to explore aspects of a situation, or to seek explanation and provide data for testing hypotheses. It is important to recognize that ‘the survey approach is a research strategy, not a research method’ [ 3 ]. As with any research approach, a choice of methods is available and the one most appropriate to the individual project should be used. This paper will discuss the most popular methods employed in survey research, with an emphasis upon difficulties commonly encountered when using these methods.

Descriptive research

Descriptive research is a most basic type of enquiry that aims to observe (gather information on) certain phenomena, typically at a single point in time: the ‘cross-sectional’ survey. The aim is to examine a situation by describing important factors associated with that situation, such as demographic, socio-economic, and health characteristics, events, behaviours, attitudes, experiences, and knowledge. Descriptive studies are used to estimate specific parameters in a population (e.g. the prevalence of infant breast feeding) and to describe associations (e.g. the association between infant breast feeding and maternal age).

Analytical studies

Analytical studies go beyond simple description; their intention is to illuminate a specific problem through focused data analysis, typically by looking at the effect of one set of variables upon another set. These are longitudinal studies, in which data are collected at more than one point in time with the aim of illuminating the direction of observed associations. Data may be collected from the same sample on each occasion (cohort or panel studies) or from a different sample at each point in time (trend studies).

Evaluation research

This form of research collects data to ascertain the effects of a planned change.

Advantages:

The research produces data based on real-world observations (empirical data).

The breadth of coverage of many people or events means that it is more likely than some other approaches to obtain data based on a representative sample, and can therefore be generalizable to a population.

Surveys can produce a large amount of data in a short time for a fairly low cost. Researchers can therefore set a finite time-span for a project, which can assist in planning and delivering end results.

Disadvantages:

The significance of the data can become neglected if the researcher focuses too much on the range of coverage to the exclusion of an adequate account of the implications of those data for relevant issues, problems, or theories.

The data that are produced are likely to lack details or depth on the topic being investigated.

Securing a high response rate to a survey can be hard to control, particularly when it is carried out by post, but is also difficult when the survey is carried out face-to-face or over the telephone.

Research question

Good research has the characteristic that its purpose is to address a single clear and explicit research question; conversely, the end product of a study that aims to answer a number of diverse questions is often weak. Weakest of all, however, are those studies that have no research question at all and whose design simply is to collect a wide range of data and then to ‘trawl’ the data looking for ‘interesting’ or ‘significant’ associations. This is a trap novice researchers in particular fall into. Therefore, in developing a research question, the following aspects should be considered [ 4 ]:

Be knowledgeable about the area you wish to research.

Widen the base of your experience, explore related areas, and talk to other researchers and practitioners in the field you are surveying.

Consider using techniques for enhancing creativity, for example brainstorming ideas.

Avoid the pitfalls of: allowing a decision regarding methods to decide the questions to be asked; posing research questions that cannot be answered; asking questions that have already been answered satisfactorily.

The survey approach can employ a range of methods to answer the research question. Common survey methods include postal questionnaires, face-to-face interviews, and telephone interviews.

Postal questionnaires

This method involves sending questionnaires to a large sample of people covering a wide geographical area. Postal questionnaires are usually received ‘cold’, without any previous contact between researcher and respondent. The response rate for this type of method is usually low, ∼20%, depending on the content and length of the questionnaire. As response rates are low, a large sample is required when using postal questionnaires, for two main reasons: first, to ensure that the demographic profile of survey respondents reflects that of the survey population; and secondly, to provide a sufficiently large data set for analysis.

Face-to-face interviews

Face-to-face interviews involve the researcher approaching respondents personally, either in the street or by calling at people’s homes. The researcher then asks the respondent a series of questions and notes their responses. The response rate is often higher than that of postal questionnaires as the researcher has the opportunity to sell the research to a potential respondent. Face-to-face interviewing is a more costly and time-consuming method than the postal survey, however the researcher can select the sample of respondents in order to balance the demographic profile of the sample.

Telephone interviews

Telephone surveys, like face-to-face interviews, allow a two-way interaction between researcher and respondent. Telephone surveys are quicker and cheaper than face-to-face interviewing. Whilst resulting in a higher response rate than postal surveys, telephone surveys often attract a higher level of refusals than face-to-face interviews as people feel less inhibited about refusing to take part when approached over the telephone.

Whether using a postal questionnaire or interview method, the questions asked have to be carefully planned and piloted. The design, wording, form, and order of questions can affect the type of responses obtained, and careful design is needed to minimize bias in results. When designing a questionnaire or question route for interviewing, the following issues should be considered: (1) planning the content of a research tool; (2) questionnaire layout; (3) interview questions; (4) piloting; and (5) covering letter.

Planning the content of a research tool

The topics of interest should be carefully planned and relate clearly to the research question. It is often useful to involve experts in the field, colleagues, and members of the target population in question design in order to ensure the validity of the coverage of questions included in the tool (content validity).

Researchers should conduct a literature search to identify existing, psychometrically tested questionnaires. A well designed research tool is simple, appropriate for the intended use, acceptable to respondents, and should include a clear and interpretable scoring system. A research tool must also demonstrate the psychometric properties of reliability (consistency from one measurement to the next), validity (accurate measurement of the concept), and, if a longitudinal study, responsiveness to change [ 5 ]. The development of research tools, such as attitude scales, is a lengthy and costly process. It is important that researchers recognize that the development of the research tool is equal in importance—and deserves equal attention—to data collection. If a research instrument has not undergone a robust process of development and testing, the credibility of the research findings themselves may legitimately be called into question and may even be completely disregarded. Surveys of patient satisfaction and similar are commonly weak in this respect; one review found that only 6% of patient satisfaction studies used an instrument that had undergone even rudimentary testing [ 6 ]. Researchers who are unable or unwilling to undertake this process are strongly advised to consider adopting an existing, robust research tool.

Questionnaire layout

Questionnaires used in survey research should be clear and well presented. The use of capital (upper case) letters only should be avoided, as this format is hard to read. Questions should be numbered and clearly grouped by subject. Clear instructions should be given and headings included to make the questionnaire easier to follow.

The researcher must think about the form of the questions, avoiding ‘double-barrelled’ questions (two or more questions in one, e.g. ‘How satisfied were you with your personal nurse and the nurses in general?’), questions containing double negatives, and leading or ambiguous questions. Questions may be open (where the respondent composes the reply) or closed (where pre-coded response options are available, e.g. multiple-choice questions). Closed questions with pre-coded response options are most suitable for topics where the possible responses are known. Closed questions are quick to administer and can be easily coded and analysed. Open questions should be used where possible replies are unknown or too numerous to pre-code. Open questions are more demanding for respondents but if well answered can provide useful insight into a topic. Open questions, however, can be time consuming to administer and difficult to analyse. Whether using open or closed questions, researchers should plan clearly how answers will be analysed.

Interview questions

Open questions are used more frequently in unstructured interviews, whereas closed questions typically appear in structured interview schedules. A structured interview is like a questionnaire that is administered face to face with the respondent. When designing the questions for a structured interview, the researcher should consider the points highlighted above regarding questionnaires. The interviewer should have a standardized list of questions, each respondent being asked the same questions in the same order. If closed questions are used the interviewer should also have a range of pre-coded responses available.

If carrying out a semi-structured interview, the researcher should have a clear, well thought out set of questions; however, the questions may take an open form and the researcher may vary the order in which topics are considered.

A research tool should be tested on a pilot sample of members of the target population. This process will allow the researcher to identify whether respondents understand the questions and instructions, and whether the meaning of questions is the same for all respondents. Where closed questions are used, piloting will highlight whether sufficient response categories are available, and whether any questions are systematically missed by respondents.

When conducting a pilot, the same procedure as as that to be used in the main survey should be followed; this will highlight potential problems such as poor response.

Covering letter

All participants should be given a covering letter including information such as the organization behind the study, including the contact name and address of the researcher, details of how and why the respondent was selected, the aims of the study, any potential benefits or harm resulting from the study, and what will happen to the information provided. The covering letter should both encourage the respondent to participate in the study and also meet the requirements of informed consent (see below).

The concept of sample is intrinsic to survey research. Usually, it is impractical and uneconomical to collect data from every single person in a given population; a sample of the population has to be selected [ 7 ]. This is illustrated in the following hypothetical example. A hospital wants to conduct a satisfaction survey of the 1000 patients discharged in the previous month; however, as it is too costly to survey each patient, a sample has to be selected. In this example, the researcher will have a list of the population members to be surveyed (sampling frame). It is important to ensure that this list is both up-to date and has been obtained from a reliable source.

The method by which the sample is selected from a sampling frame is integral to the external validity of a survey: the sample has to be representative of the larger population to obtain a composite profile of that population [ 8 ].

There are methodological factors to consider when deciding who will be in a sample: How will the sample be selected? What is the optimal sample size to minimize sampling error? How can response rates be maximized?

The survey methods discussed below influence how a sample is selected and the size of the sample. There are two categories of sampling: random and non-random sampling, with a number of sampling selection techniques contained within the two categories. The principal techniques are described here [ 9 ].

Random sampling

Generally, random sampling is employed when quantitative methods are used to collect data (e.g. questionnaires). Random sampling allows the results to be generalized to the larger population and statistical analysis performed if appropriate. The most stringent technique is simple random sampling. Using this technique, each individual within the chosen population is selected by chance and is equally as likely to be picked as anyone else. Referring back to the hypothetical example, each patient is given a serial identifier and then an appropriate number of the 1000 population members are randomly selected. This is best done using a random number table, which can be generated using computer software (a free on-line randomizer can be found at http://www.randomizer.org/index.htm ).

Alternative random sampling techniques are briefly described. In systematic sampling, individuals to be included in the sample are chosen at equal intervals from the population; using the earlier example, every fifth patient discharged from hospital would be included in the survey. Stratified sampling selects a specific group and then a random sample is selected. Using our example, the hospital may decide only to survey older surgical patients. Bigger surveys may employ cluster sampling, which randomly assigns groups from a large population and then surveys everyone within the groups, a technique often used in national-scale studies.

Non-random sampling

Non-random sampling is commonly applied when qualitative methods (e.g. focus groups and interviews) are used to collect data, and is typically used for exploratory work. Non-random sampling deliberately targets individuals within a population. There are three main techniques. (1) purposive sampling: a specific population is identified and only its members are included in the survey; using our example above, the hospital may decide to survey only patients who had an appendectomy. (2) Convenience sampling: the sample is made up of the individuals who are the easiest to recruit. Finally, (3) snowballing: the sample is identified as the survey progresses; as one individual is surveyed he or she is invited to recommend others to be surveyed.

It is important to use the right method of sampling and to be aware of the limitations and statistical implications of each. The need to ensure that the sample is representative of the larger population was highlighted earlier and, alongside the sampling method, the degree of sampling error should be considered. Sampling error is the probability that any one sample is not completely representative of the population from which it has been drawn [ 9 ]. Although sampling error cannot be eliminated entirely, the sampling technique chosen will influence the extent of the error. Simple random sampling will give a closer estimate of the population than a convenience sample of individuals who just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Sample size

What sample size is required for a survey? There is no definitive answer to this question: large samples with rigorous selection are more powerful as they will yield more accurate results, but data collection and analysis will be proportionately more time consuming and expensive. Essentially, the target sample size for a survey depends on three main factors: the resources available, the aim of the study, and the statistical quality needed for the survey. For ‘qualitative’ surveys using focus groups or interviews, the sample size needed will be smaller than if quantitative data is collected by questionnaire. If statistical analysis is to be performed on the data then sample size calculations should be conducted. This can be done using computer packages such as G * Power [ 10 ]; however, those with little statistical knowledge should consult a statistician. For practical recommendations on sample size, the set of survey guidelines developed by the UK Department of Health [ 11 ] should be consulted.

Larger samples give a better estimate of the population but it can be difficult to obtain an adequate number of responses. It is rare that everyone asked to participate in the survey will reply. To ensure a sufficient number of responses, include an estimated non-response rate in the sample size calculations.

Response rates are a potential source of bias. The results from a survey with a large non-response rate could be misleading and only representative of those who replied. French [ 12 ] reported that non-responders to patient satisfaction surveys are less likely to be satisfied than people who reply. It is unwise to define a level above which a response rate is acceptable, as this depends on many local factors; however, an achievable and acceptable rate is ∼75% for interviews and 65% for self-completion postal questionnaires [ 9 , 13 ]. In any study, the final response rate should be reported with the results; potential differences between the respondents and non-respondents should be explicitly explored and their implications discussed.

There are techniques to increase response rates. A questionnaire must be concise and easy to understand, reminders should be sent out, and method of recruitment should be carefully considered. Sitzia and Wood [ 13 ] found that participants recruited by mail or who had to respond by mail had a lower mean response rate (67%) than participants who were recruited personally (mean response 76.7%). A most useful review of methods to maximize response rates in postal surveys has recently been published [ 14 ].

Researchers should approach data collection in a rigorous and ethical manner. The following information must be clearly recorded:

How, where, how many times, and by whom potential respondents were contacted.

How many people were approached and how many of those agreed to participate.

How did those who agreed to participate differ from those who refused with regard to characteristics of interest in the study, for example how were they identified, where were they approached, and what was their gender, age, and features of their illness or health care.

How was the survey administered (e.g. telephone interview).

What was the response rate (i.e. the number of usable data sets as a proportion of the number of people approached).

The purpose of all analyses is to summarize data so that it is easily understood and provides the answers to our original questions: ‘In order to do this researchers must carefully examine their data; they should become friends with their data’ [ 15 ]. Researchers must prepare to spend substantial time on the data analysis phase of a survey (and this should be built into the project plan). When analysis is rushed, often important aspects of the data are missed and sometimes the wrong analyses are conducted, leading to both inaccurate results and misleading conclusions [ 16 ]. However, and this point cannot be stressed strongly enough, researchers must not engage in data dredging, a practice that can arise especially in studies in which large numbers of dependent variables can be related to large numbers of independent variables (outcomes). When large numbers of possible associations in a dataset are reviewed at P < 0.05, one in 20 of the associations by chance will appear ‘statistically significant’; in datasets where only a few real associations exist, testing at this significance level will result in the large majority of findings still being false positives [ 17 ].

The method of data analysis will depend on the design of the survey and should have been carefully considered in the planning stages of the survey. Data collected by qualitative methods should be analysed using established methods such as content analysis [ 18 ], and where quantitative methods have been used appropriate statistical tests can be applied. Describing methods of analysis here would be unproductive as a multitude of introductory textbooks and on-line resources are available to help with simple analyses of data (e.g. [ 19 , 20 ]). For advanced analysis a statistician should be consulted.

When reporting survey research, it is essential that a number of key points are covered (though the length and depth of reporting will be dependent upon journal style). These key points are presented as a ‘checklist’ below:

Explain the purpose or aim of the research, with the explicit identification of the research question.

Explain why the research was necessary and place the study in context, drawing upon previous work in relevant fields (the literature review).

State the chosen research method or methods, and justify why this method was chosen.

Describe the research tool. If an existing tool is used, briefly state its psychometric properties and provide references to the original development work. If a new tool is used, you should include an entire section describing the steps undertaken to develop and test the tool, including results of psychometric testing.

Describe how the sample was selected and how data were collected, including:

How were potential subjects identified?

How many and what type of attempts were made to contact subjects?

Who approached potential subjects?

Where were potential subjects approached?

How was informed consent obtained?

How many agreed to participate?

How did those who agreed differ from those who did not agree?

What was the response rate?

Describe and justify the methods and tests used for data analysis.

Present the results of the research. The results section should be clear, factual, and concise.

Interpret and discuss the findings. This ‘discussion’ section should not simply reiterate results; it should provide the author’s critical reflection upon both the results and the processes of data collection. The discussion should assess how well the study met the research question, should describe the problems encountered in the research, and should honestly judge the limitations of the work.

Present conclusions and recommendations.

The researcher needs to tailor the research report to meet:

The expectations of the specific audience for whom the work is being written.

The conventions that operate at a general level with respect to the production of reports on research in the social sciences.

Anyone involved in collecting data from patients has an ethical duty to respect each individual participant’s autonomy. Any survey should be conducted in an ethical manner and one that accords with best research practice. Two important ethical issues to adhere to when conducting a survey are confidentiality and informed consent.

The respondent’s right to confidentiality should always be respected and any legal requirements on data protection adhered to. In the majority of surveys, the patient should be fully informed about the aims of the survey, and the patient’s consent to participate in the survey must be obtained and recorded.

The professional bodies listed below, among many others, provide guidance on the ethical conduct of research and surveys.

American Psychological Association: http://www.apa.org

British Psychological Society: http://www.bps.org.uk

British Medical Association: http://www.bma.org.uk .

UK General Medical Council: http://www.gmc-uk.org

American Medical Association: http://www.ama-assn.org

UK Royal College of Nursing: http://www.rcn.org.uk

UK Department of Health: http://www.doh.gov

Survey research demands the same standards in research practice as any other research approach, and journal editors and the broader research community will judge a report of survey research with the same level of rigour as any other research report. This is not to say that survey research need be particularly difficult or complex; the point to emphasize is that researchers should be aware of the steps required in survey research, and should be systematic and thoughtful in the planning, execution, and reporting of the project. Above all, survey research should not be seen as an easy, ‘quick and dirty’ option; such work may adequately fulfil local needs (e.g. a quick survey of hospital staff satisfaction), but will not stand up to academic scrutiny and will not be regarded as having much value as a contribution to knowledge.

Address reprint requests to John Sitzia, Research Department, Worthing Hospital, Lyndhurst Road, Worthing BN11 2DH, West Sussex, UK. E-mail: [email protected]

London School of Economics, UK. Http://booth.lse.ac.uk/ (accessed 15 January 2003 ).

Vernon A. A Quaker Businessman: Biography of Joseph Rowntree (1836–1925) . London: Allen & Unwin, 1958 .

Denscombe M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-scale Social Research Projects . Buckingham: Open University Press, 1998 .

Robson C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-researchers . Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1993 .

Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to their Development and Use . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 .

Sitzia J. How valid and reliable are patient satisfaction data? An analysis of 195 studies. Int J Qual Health Care 1999 ; 11: 319 –328.

Bowling A. Research Methods in Health. Investigating Health and Health Services . Buckingham: Open University Press, 2002 .

American Statistical Association, USA. Http://www.amstat.org (accessed 9 December 2002 ).

Arber S. Designing samples. In: Gilbert N, ed. Researching Social Life . London: SAGE Publications, 2001 .

Heinrich Heine University, Dusseldorf, Germany. Http://www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de/aap/projects/gpower/index.html (accessed 12 December 2002 ).

Department of Health, England. Http://www.doh.gov.uk/acutesurvey/index.htm (accessed 12 December 2002 ).

French K. Methodological considerations in hospital patient opinion surveys. Int J Nurs Stud 1981 ; 18: 7 –32.

Sitzia J, Wood N. Response rate in patient satisfaction research: an analysis of 210 published studies. Int J Qual Health Care 1998 ; 10: 311 –317.

Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M et al. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. Br Med J 2002 ; 324: 1183 .

Wright DB. Making friends with our data: improving how statistical results are reported. Br J Educ Psychol 2003 ; in press.

Wright DB, Kelley K. Analysing and reporting data. In: Michie S, Abraham C, eds. Health Psychology in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2003 ; in press.

Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Data dredging, bias, or confounding. Br Med J 2002 ; 325: 1437 –1438.

Morse JM, Field PA. Nursing Research: The Application of Qualitative Approaches . London: Chapman and Hall, 1996 .

Wright DB. Understanding Statistics: An Introduction for the Social Sciences . London: SAGE Publications, 1997 .

Sportscience, New Zealand. Http://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/index.html (accessed 12 December 2002 ).

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| January 2017 | 546 |

| February 2017 | 1,306 |

| March 2017 | 1,894 |

| April 2017 | 654 |

| May 2017 | 558 |

| June 2017 | 672 |

| July 2017 | 1,008 |

| August 2017 | 1,402 |

| September 2017 | 1,804 |

| October 2017 | 1,956 |

| November 2017 | 2,383 |

| December 2017 | 12,150 |

| January 2018 | 14,746 |

| February 2018 | 14,347 |

| March 2018 | 19,522 |

| April 2018 | 22,008 |

| May 2018 | 21,049 |

| June 2018 | 16,327 |

| July 2018 | 15,714 |

| August 2018 | 16,971 |

| September 2018 | 13,090 |

| October 2018 | 13,950 |

| November 2018 | 18,006 |

| December 2018 | 14,269 |

| January 2019 | 13,561 |

| February 2019 | 14,618 |

| March 2019 | 18,228 |

| April 2019 | 21,143 |

| May 2019 | 19,192 |

| June 2019 | 14,610 |

| July 2019 | 13,374 |

| August 2019 | 14,002 |

| September 2019 | 17,582 |

| October 2019 | 18,119 |

| November 2019 | 15,591 |

| December 2019 | 10,684 |

| January 2020 | 10,063 |

| February 2020 | 10,358 |

| March 2020 | 10,819 |

| April 2020 | 15,267 |

| May 2020 | 8,603 |

| June 2020 | 11,066 |

| July 2020 | 10,600 |

| August 2020 | 10,331 |

| September 2020 | 12,058 |

| October 2020 | 11,934 |

| November 2020 | 11,938 |

| December 2020 | 9,337 |

| January 2021 | 9,580 |

| February 2021 | 12,962 |

| March 2021 | 12,776 |

| April 2021 | 12,545 |

| May 2021 | 10,295 |

| June 2021 | 6,443 |

| July 2021 | 6,310 |

| August 2021 | 6,980 |

| September 2021 | 6,884 |

| October 2021 | 7,713 |

| November 2021 | 9,433 |

| December 2021 | 6,886 |

| January 2022 | 7,206 |

| February 2022 | 7,517 |

| March 2022 | 8,644 |

| April 2022 | 8,995 |

| May 2022 | 8,402 |

| June 2022 | 5,556 |

| July 2022 | 3,849 |

| August 2022 | 3,901 |

| September 2022 | 4,495 |

| October 2022 | 5,624 |

| November 2022 | 5,794 |

| December 2022 | 4,603 |

| January 2023 | 5,501 |

| February 2023 | 5,148 |

| March 2023 | 6,984 |

| April 2023 | 7,545 |

| May 2023 | 6,876 |

| June 2023 | 4,578 |

| July 2023 | 4,286 |

| August 2023 | 4,431 |

| September 2023 | 4,664 |

| October 2023 | 5,736 |

| November 2023 | 6,022 |

| December 2023 | 4,633 |

| January 2024 | 4,965 |

| February 2024 | 4,645 |

| March 2024 | 6,754 |

| April 2024 | 6,545 |

| May 2024 | 5,452 |

| June 2024 | 1,745 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3677

- Print ISSN 1353-4505

- Copyright © 2024 International Society for Quality in Health Care and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

ScienceSphere.blog

Mastering The Art Of Writing A Survey Paper: A Step-By-Step Guide

Table of Contents

Importance of survey papers in academic research

Survey papers play a crucial role in academic research as they provide a comprehensive overview of a specific topic or field. These papers serve as valuable resources for researchers, students, and professionals who want to gain a deeper understanding of a subject. By synthesizing existing literature, survey papers help to identify research gaps, highlight key findings, and offer insights into future research directions.

Survey papers are essential for the following reasons:

Summarizing existing knowledge: Survey papers consolidate and summarize the existing body of knowledge on a particular topic. They provide a comprehensive overview of the research conducted in the field, making it easier for readers to grasp the key concepts and findings.

Identifying research gaps: By analyzing the existing literature, survey papers help researchers identify areas where further investigation is needed. They highlight the gaps in knowledge and suggest potential research questions that can contribute to the advancement of the field.

Saving time and effort: Instead of going through numerous individual research papers, survey papers offer a consolidated source of information. Researchers can save time and effort by referring to a well-structured survey paper that provides a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Providing a foundation for new research: Survey papers serve as a foundation for new research. They provide researchers with a solid understanding of the existing literature, enabling them to build upon previous studies and contribute to the field’s knowledge.

Purpose of the blog post

The purpose of this blog post is to guide aspiring researchers and students on how to write an effective survey paper. It will provide a step-by-step approach to help them navigate through the process of selecting a topic, conducting a literature review, outlining the structure, writing the paper, editing and proofreading, formatting and presentation, and finalizing the survey paper.

By following the guidelines outlined in this blog post, readers will be equipped with the necessary tools and knowledge to produce a high-quality survey paper that adds value to the academic community. Whether they are writing a survey paper for a course assignment, a research project, or a publication, this blog post will serve as a comprehensive resource to help them excel in their writing endeavors.

In the next section, we will delve into the basics of survey papers, including their definition, different types, and the benefits of writing one.

Understanding the Basics

A survey paper is a comprehensive review of existing literature on a specific topic or research area. It aims to provide a summary and analysis of the current state of knowledge in the field. Understanding the basics of survey papers is crucial for researchers and academics who wish to contribute to the existing body of knowledge. Here, we will explore the definition of a survey paper, different types of survey papers, and the benefits of writing one.

Definition of a survey paper

A survey paper, also known as a review paper or a literature review, is a type of academic paper that synthesizes and analyzes existing research on a particular topic. It goes beyond summarizing individual studies and aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the field. The goal of a survey paper is to identify trends, patterns, and gaps in the existing literature .

Different types of survey papers

There are several types of survey papers, each with its own purpose and focus. Some common types include:

Traditional survey papers : These provide a broad overview of the topic, covering various aspects and subtopics. They aim to present a comprehensive summary of the existing literature.

Focused survey papers : These focus on a specific aspect or subtopic within a broader field. They delve deeper into a particular area of interest and provide a more detailed analysis.

Systematic review papers : These follow a specific methodology for selecting and analyzing studies. They aim to minimize bias and provide an objective assessment of the available evidence.

Meta-analysis papers : These involve statistical analysis of data from multiple studies to draw conclusions and identify patterns or relationships.

Benefits of writing a survey paper

Writing a survey paper offers several benefits for researchers and academics:

Understanding the research landscape : Conducting a comprehensive literature review allows researchers to gain a deep understanding of the current state of knowledge in their field. It helps identify gaps, controversies, and areas that require further investigation.

Contributing to the field : By synthesizing and analyzing existing research, survey papers provide valuable insights and perspectives. They can help shape the direction of future research and contribute to the advancement of knowledge.

Building credibility : Publishing a well-written survey paper enhances the author’s reputation and credibility in the academic community. It demonstrates expertise in the field and the ability to critically evaluate and synthesize existing research.

Identifying research opportunities : Survey papers often highlight areas where further research is needed. They can inspire new research questions and guide researchers towards fruitful avenues of investigation.

In conclusion, understanding the basics of survey papers is essential for researchers and academics. It involves knowing the definition of a survey paper, different types of survey papers, and the benefits of writing one. By conducting a comprehensive literature review and synthesizing existing research, survey papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge in a particular field. They provide valuable insights, identify research gaps, and guide future research directions.

Choosing a Topic

Choosing the right topic is a crucial step in writing a survey paper. It sets the foundation for your research and determines the direction of your paper. Here are some key considerations when selecting a topic:

Identifying a Research Gap

To begin, you need to identify a research gap in the existing literature. Look for areas where there is limited or conflicting information, unanswered questions, or emerging trends. This will ensure that your survey paper adds value to the academic community by filling a knowledge gap .

Selecting a Specific Area of Interest

Once you have identified a research gap, narrow down your focus by selecting a specific area of interest within that gap. Choose a topic that aligns with your expertise and interests . This will make the writing process more enjoyable and allow you to bring a unique perspective to the paper.

Ensuring the Topic is Relevant and Significant

When choosing a topic, it is important to consider its relevance and significance. Select a topic that is timely and has practical implications . This will make your survey paper more valuable to readers and increase its impact. Additionally, consider the potential for future research and the broader implications of your chosen topic.

To ensure the relevance and significance of your topic, you can:

- Review recent publications and conference proceedings to identify emerging trends and hot topics in your field.

- Consult with experts and mentors to get their insights and suggestions on potential topics.

- Consider the practical applications of your chosen topic and how it can contribute to real-world problem-solving.

By following these steps, you can choose a topic that is both interesting to you and valuable to the academic community. Remember, the topic you choose will shape the entire survey paper, so take the time to select it wisely.

In conclusion, choosing a topic for your survey paper involves identifying a research gap, selecting a specific area of interest, and ensuring the topic is relevant and significant. By following these guidelines, you can set the stage for a well-rounded and impactful survey paper.

Conducting a Literature Review

Conducting a thorough literature review is a crucial step in writing a survey paper. It involves searching for relevant sources, evaluating their credibility, and organizing and summarizing the literature. This section will guide you through the process of conducting a literature review effectively.

Searching for relevant sources

When conducting a literature review, it is essential to search for relevant sources that contribute to your understanding of the topic. Here are some tips to help you find the right sources:

Utilize academic databases : Academic databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, and IEEE Xplore are excellent resources for finding scholarly articles, conference papers, and research studies related to your topic.

Use appropriate keywords : Use specific keywords and phrases that accurately represent your research topic. This will help you narrow down your search and find relevant sources more efficiently.

Explore citation lists : Look for relevant sources in the reference lists of articles and papers you have already found. This can lead you to additional sources that are highly relevant to your research.

Consider different publication types : Apart from academic journals, consider including books, reports, theses, and dissertations in your literature review. These sources can provide valuable insights and perspectives on your topic.

Evaluating the credibility of the sources

It is crucial to evaluate the credibility and reliability of the sources you include in your literature review. Here are some factors to consider when assessing the credibility of a source:

Author’s expertise : Check the credentials and expertise of the author(s) of the source. Look for their affiliations, qualifications, and previous research experience in the field.

Publication venue : Consider the reputation and impact factor of the journal or conference where the source was published. High-quality venues often have a rigorous peer-review process, ensuring the reliability of the research.

Currency of the source : Ensure that the source is up-to-date and reflects the current state of research in the field. This is particularly important in rapidly evolving areas of study.

Peer-reviewed sources : Prefer sources that have undergone a peer-review process. Peer-reviewed articles are evaluated by experts in the field, ensuring the quality and validity of the research.

Organizing and summarizing the literature

Once you have gathered relevant sources, it is essential to organize and summarize the literature effectively. Here are some steps to help you with this process:

Create a citation database : Maintain a database or spreadsheet to keep track of the sources you have found. Include important details such as author names, publication year, title, and relevant notes.

Identify key themes and subtopics : Analyze the literature to identify common themes and subtopics that emerge from the sources. This will help you organize your survey paper and provide a logical flow of ideas.

Summarize the main findings : Write concise summaries of the main findings and key points from each source. Focus on the aspects that are most relevant to your research question or objective.

Identify gaps and controversies : Pay attention to any gaps or controversies in the literature. These can be areas where further research is needed or where different studies present conflicting results.

By following these steps, you can conduct a comprehensive literature review that forms the foundation of your survey paper. Remember to critically analyze and synthesize the information from various sources to provide a balanced and informative overview of the topic.

Outlining the Structure

When writing a survey paper, it is crucial to have a well-structured outline that guides the flow of your content. A clear and organized structure not only helps you present your ideas effectively but also makes it easier for readers to navigate through your paper. In this section, we will discuss the key components of outlining the structure of a survey paper.

The introduction sets the stage for your survey paper and provides essential background information to the readers. It should capture their attention and clearly state the research question or objective of your paper.

Background information : Start by providing a brief overview of the topic and its significance in the field. This helps readers understand the context and relevance of your survey paper.

Research question/objective : Clearly state the main research question or objective that your paper aims to address. This helps readers understand the purpose and focus of your survey.

The main body of your survey paper should be well-organized and structured to present your findings and analysis in a coherent manner. Consider the following points when outlining the main body:

Subtopics and their organization : Identify the key subtopics or themes that you will cover in your survey. These subtopics should be logically organized to provide a smooth flow of ideas. You can use headings and subheadings to clearly indicate the different sections of your paper.

Inclusion of relevant studies and findings : Within each subtopic, include relevant studies, research papers, and findings that contribute to the understanding of the topic. Make sure to cite and reference these sources properly to give credit to the original authors.

The conclusion of your survey paper should summarize the key points discussed in the main body and provide insights for future research directions. Consider the following elements when outlining the conclusion:

Summary of key points : Provide a concise summary of the main findings and insights from your survey. This helps readers grasp the main takeaways from your paper.

Future research directions : Discuss potential areas for further research or gaps that need to be addressed in the field. This encourages readers to explore new avenues and continue the scholarly conversation.

Having a well-structured outline for your survey paper ensures that you cover all the necessary components and present your ideas in a logical and coherent manner. It helps you stay focused and organized throughout the writing process.

Remember to review and revise your outline as needed to ensure that it aligns with the specific requirements and preferences of your survey paper. A well-structured survey paper not only enhances your credibility as a researcher but also contributes to the academic community’s knowledge and understanding of the topic.

Writing the Survey Paper

Writing a survey paper requires careful planning and organization to ensure that the information is presented in a clear and coherent manner. In this section, we will discuss the key steps involved in writing a survey paper.

The introduction of a survey paper plays a crucial role in capturing the reader’s attention and setting the tone for the rest of the paper. It should begin with an engaging opening statement that highlights the importance of the topic. The research question or objective should be clearly stated to provide a roadmap for the paper.