- Constructed scripts

- Multilingual Pages

Differences between writing and speech

Written and spoken language differ in many ways. However some forms of writing are closer to speech than others, and vice versa. Below are some of the ways in which these two forms of language differ:

Writing is usually permanent and written texts cannot usually be changed once they have been printed/written out.

Speech is usually transient, unless recorded, and speakers can correct themselves and change their utterances as they go along.

A written text can communicate across time and space for as long as the particular language and writing system is still understood.

Speech is usually used for immediate interactions.

Written language tends to be more complex and intricate than speech with longer sentences and many subordinate clauses. The punctuation and layout of written texts also have no spoken equivalent. However some forms of written language, such as instant messages and email, are closer to spoken language.

Spoken language tends to be full of repetitions, incomplete sentences, corrections and interruptions, with the exception of formal speeches and other scripted forms of speech, such as news reports and scripts for plays and films.

Writers receive no immediate feedback from their readers, except in computer-based communication. Therefore they cannot rely on context to clarify things so there is more need to explain things clearly and unambiguously than in speech, except in written correspondence between people who know one another well.

Speech is usually a dynamic interaction between two or more people. Context and shared knowledge play a major role, so it is possible to leave much unsaid or indirectly implied.

Writers can make use of punctuation, headings, layout, colours and other graphical effects in their written texts. Such things are not available in speech

Speech can use timing, tone, volume, and timbre to add emotional context.

Written material can be read repeatedly and closely analysed, and notes can be made on the writing surface. Only recorded speech can be used in this way.

Some grammatical constructions are only used in writing, as are some kinds of vocabulary, such as some complex chemical and legal terms.

Some types of vocabulary are used only or mainly in speech. These include slang expressions, and tags like y'know , like , etc.

Writing systems : Abjads | Alphabets | Abugidas | Syllabaries | Semanto-phonetic scripts | Undeciphered scripts | Alternative scripts | Constructed scripts | Fictional scripts | Magical scripts | Index (A-Z) | Index (by direction) | Index (by language) | Index (by continent) | What is writing? | Types of writing system | Differences between writing and speech | Language and Writing Statistics | Languages

Page last modified: 23.04.21

728x90 (Best VPN)

Why not share this page:

If you like this site and find it useful, you can support it by making a donation via PayPal or Patreon , or by contributing in other ways . Omniglot is how I make my living.

Get a 30-day Free Trial of Amazon Prime (UK)

- Learn languages quickly

- One-to-one Chinese lessons

- Learn languages with Varsity Tutors

- Green Web Hosting

- Daily bite-size stories in Mandarin

- EnglishScore Tutors

- English Like a Native

- Learn French Online

- Learn languages with MosaLingua

- Learn languages with Ling

- Find Visa information for all countries

- Writing systems

- Con-scripts

- Useful phrases

- Language learning

- Multilingual pages

- Advertising

Te Kete Ipurangi Navigation:

Te kete ipurangi user options:.

- Navigate in: te reo Māori

Search community

Searching ......

- Skip to content

English - ESOL - Literacy Online website navigation

- Home EESOLL

- English Online home

- Teaching as inquiry

- Knowledge of English

- Knowledge of the learner

- Resources, research, and professional support

- Planning using inquiry

- English and e-Learning

- Bringing It Together: Phrases

- Direct and Indirect Speech

- Exploring Visual Language

- Exploring Written Language

- Genres and Conventions

- Language Rules and Conventions

- Letters and Sounds

- Looking at Written Language

- Making Comparisons

- Moving Images

- Oral Language: Introduction

- Other Forms of Variation

- Pattern of Text: Genre

- Pronunciation English

- Putting Words Together

Speaking and Writing

- Standard English

- Static Images

- The Grammar Toolbox

- The Grammar Toolbox: Introduction

- The Language of Conversation

- Vernacular English

- Visual Language

- Word Class: Adjectives

- Word Class: Adverbs

- Word Class: Conjunctions

- Word Class: Nouns

- Word Class: Prepositions

- Word Class: Pronouns

- Word Class: Verbs

- Words and Meaning

- Written Language

- Teaching & learning sequences

- Teacher resource exchange

- Progress and achievement

- Qualifications/NCEA

- We're moving to a new home - Tāhūrangi

- Junior Journal 65 now online!

- Meet the project team

- Contact English Online

- Literacy Online home

- ESOL Online home

- Instructional Series home

- English Online >

- Planning for my students’ needs >

- Exploring language >

In his 1975 Report, A Language for Life, Lord Bullock said, "Not enough account is taken of the fundamental differences that exist between speech and writing."

Spoken and written language are obviously different, with different purposes. Written language is permanent: the reader can go back over it again and again if the meaning is not immediately clear. This is not possible with speech, which is fleeting and ephemeral. Writing does not usually involve direct interaction, except for personal letters and perhaps some computer based communication such as e-mail.

Children learn to speak before they learn to read and write. Learning to speak appears to happen naturally within the home, whereas learning to read and write is usually associated with the beginning of formal schooling. Thus, we often assume that written language is more difficult to learn, and we perceive speech as less complex than written language. This is not the case: oral language is just as linguistically complex as written language, but the complexity is of a different kind. The inevitable differences in the structures and use of speech and writing come about because they are produced in very different communicative situations.

The greatest differences between speaking and writing are those between formal written texts and very informal conversation. Because it is permanent, writing provides opportunities for more careful organisation and more complex structures.

Formal spoken language is often preplanned, but most spoken language is spontaneous and rapid and usually involves thinking on the spot. It has simpler constructions and fillers such as um and er. It has repetitions and rephrasing. It has intonation patterns and pauses that convey meaning and also attitudes.

All these oral characteristics help the listener to understand the speech. It is usually much more difficult for listeners to interpret language that is read aloud from a written text, where the language is more dense and lacks the pauses and fillers that give us time to absorb the spoken message. Lectures or talks that are read from a script are usually more difficult to follow than those that are delivered with the speaker looking at the audience and improvising from outline notes.

Some constructions probably occur only in writing.

Henry supposed Sylvia to be unwell.

Likewise, some words and constructions are likely to occur only in spoken English: words like thingamajig and whatchamecallit, and phrases like bla bla bla.

"Our teacher just said - told us there was nouns and verbs and adverbs and bla bla bla - you know ..."

Conversations also contain small words which do not appear in writing. In analysing conversations, we are often surprised to realise how many times words like well or just or oh appear.

The following transcript is of the talk of teenagers playing the board game "Scruples".

C: Do you put them face down - hang on

C: Then we get one ballot card each and you put them aside until the vote is called

V: Oh - sorry

C: Did we decide you were the dealer - yes - we did

V: Oh - that was right

C: Oh it's just that the player to the left of the dealer starts play by becoming the first - asking the player to pose a dilemma

H: Oh - what do I do - oh I take one of these

C: Oh - hang on hang on

Words like oh and well have been assigned a number of names. They can be called discourse markers or conversation markers.

They do not fit into the word classes in The Grammar Toolbox.

She is not well. (well = adjective)

She is well qualified. (well = adverb)

In conversation, "well" appears frequently but not as an adjective or an adverb.

Well what do you think? Well I'm not really sure.

These conversational markers are very hard to translate into another language, and they are difficult to define consistently or analyse structurally. Yet they occur constantly in speech. When second language learners begin to use these markers in speaking English, the fluency of their conversation improves.

Comparing Speaking and Writing

Speaking and writing are different, and each should be seen in its own terms.

In the past, writing was often regarded as the primary medium, and casual speech was seen as a sloppy or incorrect version of the written form. Speech was evaluated as if it were writing.

The basic unit of written language is the sentence.

The basic unit of spoken language is the tone group.

The following two text samples are from the same person and tell about the same incident.

Transcript of a recording:

um, well it was something that happened |

when I was living in Western Samoa |

um, I rented a house |

and, er, my bedroom |

my bedroom was actually separate |

separate from the rest of the house |

and, one night |

um, it was quite late |

I was lying in bed |

I was awake |

and, er, my flatmate |

was away at the airport |

meeting some relatives |

and so I was all alone |

and I started hearing noises |

on the roof |

of my bedroom |

it was a tin roof |

and um, I heard footsteps |

and creaking sounds |

on the the tin |

and an, another noise |

I couldn’t quite |

tell what it was |

but it but it was something strange |

and I was scared |

really scared |

um, and my problem was |

I couldn’t |

get to a phone |

unlocking my bedroom door |

walking across the lawn |

unlocking the front door |

and going into the house |

the thought of doing this |

while there was somebody on the roof |

[laughs] er, w-was not very, er |

possible so |

there I am |

lying there |

what on earth will I do |

and I finally |

figured that |

probably the person there |

thought there was no one home |

and was just trying to break in |

trying to rob the place |

so I had a brainwave |

[laughs] and immediately the person ran |

across the roof |

and jumped off |

er, and landed on the lawn |

I heard a thud |

um, so then I unlocked the door |

and went across to the house |

and phoned the police |

well they were |

they were there |

really quickly |

I'd say within a couple of minutes |

A written account of the incident by the same person:

When I lived in Western Samoa I shared a rented house with a flatmate.

Late one night when he was away meeting some relatives at the airport, I heard strange noises like footsteps on the tin roof of my bedroom, which was separate from the rest of the house.

In order to get to a phone, I would have had to walk over to the main part of the house and unlock the front door.

I decided against this course of action, switching the light on instead, and this had the desired effect of driving away the intruder, who obviously had been thinking there was no one home.

Whoever it was ran across the roof and jumped off, landing with an audible thud on the lawn before running away.

The police arrived very soon after I had called them.

These two examples clearly illustrate the following differences between speech and writing:

Speech uses tone groups, and a tone group can convey only one idea. Writing uses sentences, and a sentence can contain several ideas.

A fundamental difference between casual speech and writing is that speech is spontaneous whereas writing is planned.

Repetition is usually found in speech. Writing avoids repetition.

Repetition of words and phrases:

27 and 28: scared

34 and 36: unlocking

Repetition of syntactic frames:

34: unlocking my bedroom door

35: walking across the lawn

Written language avoids repetition. Writers try to find synonyms rather than repeating the same words and phrases.

The spoken text gives us an insight into the speaker's thoughts.

24 and 25: I couldn't quite tell what it was.

27: I was scared.

46 and 47: and I finally figured that

In spoken language, we use intensifiers.

27 and 28: and I was scared | really scared

Because spoken language is interactive, direct address is used - "I" and "you".

22: you know

Spoken narrative can use the timeless present, which would be unusual in a written text. It adds to the immediacy of the story.

42, 43, 44: there I am | lying there | thinking

A spoken version usually gives an account of events in the order in which they occurred because this is easier to do.

59 to 64: then I unlocked the door | went across to the house | and phoned the police | and they were there | really quickly |

In the written form, the order of events can be changed.

Sentence (f): The police arrived very soon after I had called them.

The spoken and written versions differ in syntax.

The tone groups in the spoken version are sometimes complete clauses but almost always very simple ones.

2: SVA; 5: SVC; 15: SVO

Often, the tone groups are a mixture of clauses and clause fragments that add more information to the clause.

5: my bedroom was actually separate

6: separate from the rest of the house

In the written form, the information is not presented one idea at a time but in a much more condensed way, incorporating several ideas.

3: I rented a house.

Sentence (a): When I lived in Western Samoa I shared a rented house with a flatmate.

The information in sentence (b) is conveyed by 21 tone groups in the spoken account (7-28).

In the spoken text, there is the possibility of direct speech that would be unusual in a written text.

there I am | lying there | thinking | what on earth will I do. (42-45)

This enables the speaker to gain a powerful effect by using the full possibilities of intonation.

The ability to use complex clauses and embedded phrases and clauses is acquired much later in life. We can use these structures because we have time to plan when we write. When we speak, we do not have time to plan: we structure our discourse as we go along, repeating words and phrases and using the simpler constructions that we learn early in life. In the transcript above, we can see this clearly with the subjects of the clauses. In almost all cases, these are simple: by far the majority are I or it. More complex are my bedroom (4) and my problem (29). The most complicated is: the thought of doing this while there was somebody on the roof. It is interesting that after this, the speaker needs to pause; she laughs and gets in something of a muddle: w-was not very er possible (40, 41).

The two texts illustrate sharp differences between speaking and writing. This narrative may not have been entirely spontaneous because the story had been told before, and this rehearsal could explain some of the complexities in the spoken version. Even so, it is much more fragmented and oriented towards a listener than the written version. The written version is planned, integrated, and primarily oriented towards conveying a message.

Spoken and written language can be seen as the ends of a continuum. Above, we have described features of spontaneous speech and planned writing. Often, however, the distinctions between spoken and written language are not so clear cut. A university lecture, a prepared speech, a sermon might be examples of spoken English, in so far as they are delivered verbally. But because they usually began in a written form, they are likely to be closer to written language than to casual spoken language. Personal letters, diaries, and e-mail correspondences are in the written form but are very likely to contain features of spoken language.

In this section, we have deliberately concentrated on the language of conversation rather than the language of oratory, prepared speeches, debates, or other formal forms. We made this decision for two reasons. One was that some teachers appear to think of the classroom study of oral language almost exclusively in terms of prepared and planned speaking but do not consider spontaneous speech. The second was that teachers probably know very little about the structure of conversation. It is important that conversation be understood, not only because it is the most common use of spoken language in our lives but also so that teachers recognise the important distinctions between speaking and writing. Neither form of language is better than the other: the two forms are different and should each be seen in their own terms.

What do these differences mean for speakers and writers?

| have eye contact with the listeners | do not usually write with their readers present |

| point to or refer to things in their environment | cannot assume a shared environment with their readers |

| expect encouragement and co-operation from listeners to produce conversation | have to create and sustain their own belief in what they are doing |

| use intonation, stress, loudness, and body language to help make their meaning clear | use graphic cues such as punctuation, paragraphing, bold print, and diagrams to help make their meaning clear |

| rephrase or repeat when they think their message is not clear | take time to think and rethink as they write, often revising and editing their work |

| know that all their hesitations will be heard by, and acceptable to, the listener. | know that the reader will not see any rephrasings and alterations they make to the text in the process of writing. |

From Speakers to Writers

When children are learning to write, their starting points are their understanding of the syntax and structure of oral language. The ability to write begins from a sound foundation in oral language. The interrelationships of speech and writing can be seen in writers' acquisition of written language at the "emergent" and "early" stages. Initially, children's oral language greatly outstrips their ability in written language. As children master the mechanics of writing and develop a method of approximating spelling, they are able to put down on paper what they can already say. At the "early" stage of writing, children's writing catches up with their spoken language, and their writing has many of the personal, context-bound qualities of their speech. Students' writing and speech diverge as they become fluent writers. Their writing takes on its own distinctive structures and patterns of organisation. Often, too, fluent writers' speech incorporates some features of their writing.

The popular belief that written language is speech plus the conventions of print underestimates the demonstrable differences between oral and written language. Although oral work is undeniably of great value in students' learning in general, it does not specifically help them acquire the grammatical patterns they need in their writing. The models of written language patterns come from children's reading, and having read to them, good models of written language.

Natural language is often referred to as being important in texts for young learner readers. "Natural language" does not mean writing that reflects the oral language patterns of children: rather, it refers to the use of authentic "book" or written language that uses natural rhythms and conveys real meaning, in contrast to the artificial and meaningless structures that were used in many early reading texts in the past. Compare:

Mrs Delicious got a truck full of flour for the biggest cake in the world. (natural language)

Joy Cowley: The Biggest Cake in the World

(Wellington: Department of Education, 1983)

Go up to my ox. Is she on an ox?

An early reading text

The oral language patterns that are natural to young children are extremely difficult to read, and teachers should not oversimplify the links between written and spoken language. It is essential that students' early reading provides good models of written language. Although the topics and vocabulary reflect children's experiences and interests, the structure of these texts is those of written language and may be unfamiliar to some students. If teachers have an explicit awareness of these differences, they are better able to help students move from the familiarity of spoken language to the unknown forms and functions of written language. The two forms then enrich each other in a two-way process.

It is not only the nature of the spoken and written texts themselves that differs but also the understanding of the relationship between speakers and listeners on the one hand and readers and writers on the other. In discussing the co-operative principle of conversation, we outlined the understandings that listeners and speakers have of conversation. Young children's early writings show that they understand the nature of conversation and that their expectations of readers are similar to those they have of listeners.

We can help children bridge the gap between spoken and written language by keeping in mind the new understandings about texts and audiences that children are developing.

If we look again at Grice's Maxims from the point of view of writers, we can see the shifts in understanding that students need to make.

Maxim of quality

Speakers are expected to tell the truth. They should not say things they know to be false or for which they lack adequate evidence. However, the first written texts we introduce young children to are most likely to be fiction, and we expect children to write fiction. To be imaginative and creative in writing is often highly valued, whereas in conversation it is frowned upon.

Maxim of quantity

Speakers are expected to be brief, giving sufficient but not too much information. In writing, however, young children need to elaborate to make their meaning clear. One of the first things a teacher encourages a beginning writer to do is to add information to their text. This is done in much the same way as in conversation, through questioning the writer and asking for more detail.

Maxim of relation

Speakers' responses are expected to be appropriate and relevant. Much of students' spoken language is in response to something someone else has said.

It is not difficult to see why students, especially beginner writers, have difficulty generating text on their own. Thinking of new topics to talk about, and new and exciting ways of expressing ideas, are not things speakers in conversation need to consider.

Maxim of manner

Speakers' responses are expected to be clear and avoid ambiguities. Information in speech is usually given in a linear or chronological order. Young children do not use complex grammatical constructions in their talk, and therefore these are not present in their writing. It takes time to learn that, in writing, information can be organised in many different ways.

It would be extremely frustrating to hold a conversation with someone who used the strategies often used in writing to build suspense. In spoken language, we encourage speakers to "get to the point", whereas in written narrative, we encourage young children to take time setting the scene.

Challenges for the Learner

Students need to be helped to "think through" what they want to write.

When speaking, children produce oral language in interactive settings. However, when writing, they are learning to produce a text without prompts and responses from the reader.

Students need to be helped to understand that writing is more explicit than speech.

The absence of the reader poses a problem for children, who often have difficulty imagining their audience. Their writing often has the implicitness of speech with much left unsaid, because learner writers assume that their readers bring a shared understanding to the text.

Students need to be helped to become familiar with the structures of written language.

When learning to write, children are faced with learning a new syntactic, semantic, and textual unit - the sentence. Sentences are a feature of writing rather than of speech. In speech, clauses tend to follow each other in a linear way without necessarily having a known end-point. The sentence, on the other hand, needs to be capable of standing alone. It requires planning, and a decision has to be made as to which is to be the main clause and what will be its supporting structures. Understanding and using the concept of a sentence requires more than the ability to use capital letters and full stops.

Learning to write involves learning new ways of thinking. As Gunther Kress has written in Learning to Write, it involves "learning new forms of syntactical and textural structure, new genre, and new ways of relating to unknown addressees".

Exploring language content page

Exploring Language is reproduced by permission of the publishers Learning Media Limited on behalf of Ministry of Education, P O Box 3293, Wellington, New Zealand, © Crown, 1996.

Published on: 25 Feb 2009

- About this site

- About this site |

- Contact TKI |

- Accessibility |

- Copyright and privacy |

- Copyright in Schools |

© Crown copyright.

Difference between Speech and Writing

Speech and writing are two primary forms of communication, each with its own characteristics and conventions.

What Is Speech?

Speech is the act of expressing thoughts, ideas, and emotions through spoken language. It involves the production of sounds using the vocal apparatus, which includes the lungs, vocal cords, mouth, and tongue.

What Is Writing?

Writing is a method of human communication that involves the representation of language through a system of symbols, usually known as letters or characters. It is a visual and permanent form of communication that allows for the recording and dissemination of information across time and space.

| Oral, transient, immediate. Delivered in real-time, with intonation, pauses, and body language adding meaning. | Written, permanent, can be edited. Delivered through text, allowing for planning and revision. | |

| Often spontaneous and informal. Allows for on-the-fly corrections, repetitions, and fillers (e.g., “um,” “uh”). | Typically planned and structured. Offers opportunities for editing and refining before the final version is presented. | |

| Interactive and dynamic. Immediate feedback and engagement from the audience (e.g., through questions, applause, or non-verbal cues). | Generally one-way. Feedback is delayed and often less direct (e.g., through comments, reviews, or responses). | |

| Informal and conversational. Uses contractions, slang, and idiomatic expressions more freely. Often includes non-standard grammar and incomplete sentences. | More formal and standardized. Adheres to grammatical rules and employs a more extensive vocabulary. Sentences are typically complete and well-structured. | |

| Speech relies on nonverbal cues like body language and tone of voice. | Writing uses punctuation and formatting to convey the same information. | |

| Relies heavily on context, tone, and non-verbal cues for meaning. Ambiguities can be clarified in real-time. | Must be explicit and self-contained. Less reliance on contextual clues, as the reader might not share the same immediate context. | |

| and less likely to be recorded (except in specific contexts like speeches, lectures, or broadcasts). | Permanent and can be archived. Creates a lasting record that can be referenced and revisited. | |

| Processed in real-time, which can demand more immediate cognitive effort. The speaker and listener must process and respond quickly. | Allows for reflection and deeper processing. Both the writer and reader can take their time to comprehend and analyze the content. |

Both speech and writing have their unique strengths and are suited to different contexts and purposes. Speech, with its immediacy and interactivity, is ideal for dynamic, real-time communication. Writing, with its permanence and precision, is perfect for detailed, thoughtful, and lasting communication. By understanding these differences, we can leverage the strengths of each mode to enhance our communication effectiveness in various situations.

Download the Word of the day

Related Posts:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Download the Word coach App on your Android phone

Word Coach - IELTS and GRE Vocabulary Builder & word coach Quiz (10 Words a Day) application helps, you and your friends to improve English Vocabulary and help you become the smartest among your group.

Speaking versus Writing

The pen is mightier than the spoken word. or is it.

Josef Essberger

The purpose of all language is to communicate - that is, to move thoughts or information from one person to another person.

There are always at least two people in any communication. To communicate, one person must put something "out" and another person must take something "in". We call this "output" (>>>) and "input" (<<<).

- I speak to you (OUTPUT: my thoughts go OUT of my head).

- You listen to me (INPUT: my thoughts go INto your head).

- You write to me (OUTPUT: your thoughts go OUT of your head).

- I read your words (INPUT: your thoughts go INto my head).

So language consists of four "skills": two for output (speaking and writing); and two for input (listening and reading. We can say this another way - two of the skills are for "spoken" communication and two of the skills are for "written" communication:

Spoken: >>> Speaking - mouth <<< Listening - ear

Written: >>> Writing - hand <<< Reading - eye

What are the differences between Spoken and Written English? Are there advantages and disadvantages for each form of communication?

When we learn our own (native) language, learning to speak comes before learning to write. In fact, we learn to speak almost automatically. It is natural. But somebody must teach us to write. It is not natural. In one sense, speaking is the "real" language and writing is only a representation of speaking. However, for centuries, people have regarded writing as superior to speaking. It has a higher "status". This is perhaps because in the past almost everybody could speak but only a few people could write. But as we shall see, modern influences are changing the relative status of speaking and writing.

Differences in Structure and Style

We usually write with correct grammar and in a structured way. We organize what we write into sentences and paragraphs. We do not usually use contractions in writing (though if we want to appear very friendly, then we do sometimes use contractions in writing because this is more like speaking.) We use more formal vocabulary in writing (for example, we might write "the car exploded" but say "the car blew up") and we do not usually use slang. In writing, we must use punctuation marks like commas and question marks (as a symbolic way of representing things like pauses or tone of voice in speaking).

We usually speak in a much less formal, less structured way. We do not always use full sentences and correct grammar. The vocabulary that we use is more familiar and may include slang. We usually speak in a spontaneous way, without preparation, so we have to make up what we say as we go. This means that we often repeat ourselves or go off the subject. However, when we speak, other aspects are present that are not present in writing, such as facial expression or tone of voice. This means that we can communicate at several levels, not only with words.

One important difference between speaking and writing is that writing is usually more durable or permanent. When we speak, our words live for a few moments. When we write, our words may live for years or even centuries. This is why writing is usually used to provide a record of events, for example a business agreement or transaction.

Speaker & Listener / Writer & Reader

When we speak, we usually need to be in the same place and time as the other person. Despite this restriction, speaking does have the advantage that the speaker receives instant feedback from the listener. The speaker can probably see immediately if the listener is bored or does not understand something, and can then modify what he or she is saying.

When we write, our words are usually read by another person in a different place and at a different time. Indeed, they can be read by many other people, anywhere and at any time. And the people reading our words, can do so at their leisure, slowly or fast. They can re-read what we write, too. But the writer cannot receive immediate feedback and cannot (easily) change what has been written.

How Speaking and Writing Influence Each Other

In the past, only a small number of people could write, but almost everybody could speak. Because their words were not widely recorded, there were many variations in the way they spoke, with different vocabulary and dialects in different regions. Today, almost everybody can speak and write. Because writing is recorded and more permanent, this has influenced the way that people speak, so that many regional dialects and words have disappeared. (It may seem that there are already too many differences that have to be learned, but without writing there would be far more differences, even between, for example, British and American English.) So writing has had an important influence on speaking. But speaking can also influence writing. For example, most new words enter a language through speaking. Some of them do not live long. If you begin to see these words in writing it usually means that they have become "real words" within the language and have a certain amount of permanence.

Influence of New Technology

Modern inventions such as sound recording, telephone, radio, television, fax or email have made or are making an important impact on both speaking and writing. To some extent, the divisions between speaking and writing are becoming blurred. Emails are often written in a much less formal way than is usual in writing. With voice recording, for example, it has for a long time been possible to speak to somebody who is not in the same place or time as you (even though this is a one-way communication: we can speak or listen, but not interact). With the telephone and radiotelephone, however, it became possible for two people to carry on a conversation while not being in the same place. Today, the distinctions are increasingly vague, so that we may have, for example, a live television broadcast with a mixture of recordings, telephone calls, incoming faxes and emails and so on. One effect of this new technology and the modern universality of writing has been to raise the status of speaking. Politicians who cannot organize their thoughts and speak well on television win very few votes.

English Checker

- aspect: a particular part or feature of something

- dialect: a form of a language used in a specific region

- formal: following a set of rules; structured; official

- status: level or rank in a society

- spontaneous: not planned; unprepared

- structured: organized; systematic

Note : instead of "spoken", some people say "oral" (relating to the mouth) or "aural" (relating to the ear).

© 2011 Josef Essberger

Spoken vs. Written Language

Spoken vs. written language (pdf).

Office / Department Name

Oral Communication Center

Contact Name

Amy Gaffney

Oral Communication Center Director

Help us provide an accessible education, offer innovative resources and programs, and foster intellectual exploration.

Site Search

What are the differences between writing and speaking?

Part of Language and Literacy Writing

Experimenting with language

- count 3 of 35

How to write a sentence

- count 4 of 35

How to write statement sentences

- count 5 of 35

The slippery grammar of spoken vs written English

Senior Lecturer in Linguistics, University of Waikato

Disclosure statement

Andreea S. Calude receives funding from the Royal Society Marsden Grant and Catalyst Seeding Grant .

University of Waikato provides funding as a member of The Conversation NZ.

University of Waikato provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

My grammar checker and I are on a break. Due to irreconcilable differences, we are no longer on speaking terms.

It all started when it became dead set on putting commas before every single “which”. Despite all the angry underlining, “this is a habit which seems prevalent” does not need a comma before “which”. Take it from me, I am a linguist.

This is just one of many challenging cases where grammar is slippery and hard to pin down. To make matters worse, it appears that the grammar we use while speaking is slightly different to the grammar we use while writing. Speech and writing seem similar enough – so much so that for centuries, people (linguists included) were blind to the differences.

Read more: How students from non-English-speaking backgrounds learn to read and write in different ways

There’s issues to consider

Let me give you an example. Take sentences like “there is X” and “there are X”. You may have been taught that “there is” occurs with singular entities because “is” is the present singular form of “to be” – as in “there is milk in the fridge” or “there is a storm coming”.

Conversely, “there are” is used with plural entities: “there are twelve months in a year” or “there are lots of idiots on the road”.

What about “there’s X”? Well, “there’s” is the abbreviated version of “there is”. That makes it the verb form of choice when followed by singular entities.

Nice theory. It works for standard, written language, formal academic writing, and legal documents. But in speech, things are very different .

It turns out that spoken English favours “there is” and “there’s” over “there are”, regardless of what follows the verb: “there is five bucks on the counter” or “ there’s five cars all fighting for that Number 10 spot ”.

A question of planning

This is not because English is going to hell in a hand basket, nor because young people can’t speak “proper” English anymore.

Linguists Jen Hay and Daniel Schreier scrutinised examples of old recordings of New Zealand English to see what happens in cases where you might expect “there” followed by plural, (or “there are” or “there were” for past events) but where you find “there” followed by singular (“there is”, “there’s”, “there was”).

They found that the contracted form “there’s” is a go-to form which seems prevalent with both singular and plural entities. But there’s more. The greater the distance between “be” and the entity following it, the more likely speakers are to ignore the plural rule.

“There is great vast fields of corn” is likely to be produced because the plural entity “fields” comes so far down the expression, that speakers do not plan for it in advance with a plural form “are”.

Even more surprisingly, the use of the singular may not always necessarily have much to do with what follows “there is/are”. It can simply be about the timing of the event described. With past events, the singular form is even more acceptable. “There was dogs in the yard” seems to raise fewer eyebrows than “there is dogs in the yard”.

Nothing new here

The disregard for the plural form is not a new thing (darn, we can’t even blame it on texting). According to an article published last year by Norwegian linguist Dania Bonneess , the change towards the singular form “there is” has been with us in New Zealand English ever since the 19th century. Its history can be traced at least as far back as the second generation of the Ulster family of Irish emigrants .

Editors, language commissions and prescriptivists aside, everyday New Zealand speech has a life of its own, governed not so much by style guides and grammar rules, but by living and breathing individuals.

It should be no surprise that spoken language is different to written language. The most spoken-like form of speech (conversation) is very unlike the most written-like version of language (academic or other formal or technical writing) for good reason.

Speech and writing

In conversation, there is no time for planning. Expressions come out more or less off the cuff (depending on the individual), with no ability to edit, and with immediate need for processing. We hear a chunk of language and at the same time as parsing it, we are already putting together a response to it – in real time.

This speed has consequences for the kind of language we use and hear. When speaking, we rely on recycled expressions, formulae we use over and over again, and less complex structures.

For example, we are happy enough writing and reading a sentence like:

That the human brain can use language is amazing.

But in speech, we prefer:

It is amazing that the human brain can use language.

Both are grammatical, yet one is simpler and quicker for the brain to decode.

And sometimes, in speech we use grammatical crutches to help the brain get the message quicker. A phrase like “the boxes I put the files into” is readily encountered in writing, but in speech we often say and hear “the boxes I put the files into them”.

We call these seemingly unnecessary pronouns (“them” in the previous example) “shadow pronouns”. Even linguistics professors use these latter expressions no matter how much they might deny it.

Speech: a faster ride

There is another interesting difference between speech and writing: speech is not held up on the same rigid prescriptive pedestal as writing, nor is it as heavily regulated in the same way that writing is scrutinised by editors, critics, examiners and teachers.

This allows room in speech for more creativity and more language play, and with it, faster change. Speech is known to evolve faster than writing, even though writing will eventually catch up (at least for some changes).

I would guess that by now, most editors are happy enough to let the old “whom” form rest and “who” take over (“who did you give that book to?”).

- New Zealand

- Linguistics

- Spoken language evolution

- written language

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 185,500 academics and researchers from 4,982 institutions.

Register now

Supporting writers since 1790

Essay Guide

Our comprehensive guide to the stages of the essay development process. Back to Student Resources

Display Menu

- Writing essays

- Essay writing

- Being a writer

- Thinking critically, thinking clearly

Speaking vs. Writing

- Why are you writing?

- How much is that degree in the window?

- Academic writing

- Academic writing: key features

- Personal or impersonal?

- What tutors want – 1

- What tutors want – 2

- Be prepared to be flexible

- Understanding what they want – again

- Basic definitions

- Different varieties of essay, different kinds of writing

- Look, it’s my favourite word!

- Close encounters of the word kind

- Starting to answer the question: brainstorming

- Starting to answer the question: after the storm

- Other ways of getting started

- How not to read

- You, the reader

- Choosing your reading

- How to read: SQ3R

- How to read: other techniques

- Reading around the subject

- Taking notes

- What planning and structure mean and why you need them

- Introductions: what they do

- Main bodies: what they do

- Conclusions: what they do

- Paragraphs and links

- Process, process, process

- The first draft

- The second draft

- Editing – 1: getting your essay into shape

- Editing – 2: what’s on top & what lies beneath

- Are you looking for an argument?

- Simple definitions

- More definitions

- Different types of argument

- Sources & plagiarism

- Direct quotation, paraphrasing & referencing

- MLA, APA, Harvard or MHRA?

- Using the web

- Setting out and using quotations

- Recognising differences

- Humanities essays

- Scientific writing

- Social & behavioural science writing

- Beyond the essay

- Business-style reports

- Presentations

- What is a literature review?

- Why write a literature review?

- Key points to remember

- The structure of a literature review

- How to do a literature search

- Introduction

- What is a dissertation? How is it different from an essay?

- Getting it down on paper

- Drafting and rewriting

- Planning your dissertation

- Planning for length

- Planning for content

- Abstracts, tone, unity of style

- General comments

Speaking vs writing 1: Alan buys milk

Another way to think about what’s involved in writing clearly is to think about the differences between speaking and writing. Because both use words, we assume they are the same but they are very different. The following example will help you think about the differences. Picture this: it’s Saturday morning, the family’s just sat down to breakfast when Dad realises there’s no milk. So he asks his eldest son Alan to go and get some. He says: “Drat! No milk – I can’t eat my cornflakes without some nice cold milk. Just pop out to the mini-mart, would you Alan? Better get a two pinta. Oh, and you’ll find some money in my jacket pocket.”

Speaking vs writing 2: a robot buys milk

Now picture this: imagine you had to write a computer program to tell a robot to go and buy milk. Where would you start? You would have to think of the most logical order for all the actions the robot would need to perform in order to buy milk. Dad’s instruction to Alan assumes that Alan already knows all sorts of information: where his jacket is, which pocket he usually keeps his money, where the mini-mart is, the visual difference between a one pint and two pint carton. The robot will know none of these things unless you put them in the program. You would also have to give the program a logical name or title so that when the program loaded the robot’s brain would be able to distinguish it from all the other programs in its memory. So in your writing at university, don’t be afraid to be obvious. One of the reasons tutors set essays is so you can show what you know.

Speaking vs writing 3: look at me when I’m talking to you

Another crucial difference between speaking and writing is that we can see people when we talk to them. We transmit and receive all sorts of non-verbal information when we’re talking to them. Think about the effect it has on you when someone talks to you but keeps staring at the floor and never looks at you once. We communicate all sorts of information by facial expression, hand gestures, tone of voice. We can’t do any of these things in a piece of writing. We have to find different ways of doing them; and we have to be sure that our writing isn’t doing things we don’t want it to.

Speaking vs writing 4: know what I mean?

Another crucial difference between speaking and writing is that speaking is informal, less structured, more colloquial – know what I mean? When we speak, we often start sentences in the middle. An important part of writing at university is to understand who you are writing for. To put this another way, when you are writing an essay you are not down the pub with your mates. In an essay, you can’t put things like the following sentence I once read in a first draft: “Apparently, imperialism has been going for ages – how weird is that?” The person who reads your essay will expect you to write in a serious and considered way.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association

- Certification

- Publications

- Continuing Education

- Practice Management

- Audiologists

- Speech-Language Pathologists

- Academic & Faculty

- Audiology & SLP Assistants

What Is Speech? What Is Language?

[ en Español ]

Jorge is 4 years old. It is hard to understand him when he talks. He is quiet when he speaks, and his sounds are not clear.

Vicki is in high school. She has had learning problems since she was young. She has trouble reading and writing and needs extra time to take tests.

Maryam had a stroke. She can only say one or two words at a time. She cannot tell her son what she wants and needs. She also has trouble following simple directions.

Louis also had a stroke. He is able to understand everything he hears and speaks in full sentences. The problem is that he has slurred speech and is hard to understand.

All of these people have trouble communicating. But their problems are different.

What Is Speech?

Speech is how we say sounds and words. Speech includes:

Articulation How we make speech sounds using the mouth, lips, and tongue. For example, we need to be able to say the “r” sound to say "rabbit" instead of "wabbit.”

Voice How we use our vocal folds and breath to make sounds. Our voice can be loud or soft or high- or low-pitched. We can hurt our voice by talking too much, yelling, or coughing a lot.

Fluency This is the rhythm of our speech. We sometimes repeat sounds or pause while talking. People who do this a lot may stutter.

What Is Language?

Language refers to the words we use and how we use them to share ideas and get what we want. Language includes:

- What words mean. Some words have more than one meaning. For example, “star” can be a bright object in the sky or someone famous.

- How to make new words. For example, we can say “friend,” “friendly,” or “unfriendly” and mean something different.

- How to put words together. For example, in English we say, “Peg walked to the new store” instead of “Peg walk store new.”

- What we should say at different times. For example, we might be polite and say, “Would you mind moving your foot?” But, if the person does not move, we may say, “Get off my foot!”

Language and Speech Disorders

We can have trouble with speech, language, or both. Having trouble understanding what others say is a receptive language disorder. Having problems sharing our thoughts, ideas, and feelings is an expressive language disorder. It is possible to have both a receptive and an expressive language problem.

When we have trouble saying sounds, stutter when we speak, or have voice problems, we have a speech disorder .

Jorge has a speech disorder that makes him hard to understand. So does Louis. The reason Tommy has trouble is different than the reason Louis does.

Maryam has a receptive and expressive language disorder . She does not understand what words mean and has trouble using words to talk to others.

Vicki also has a language disorder . Reading and writing are language skills. She could also have problems understanding others and using words well because of her learning disability.

Where to Get Help

SLPs work with people who have speech and language disorders. SLPs work in schools, hospitals, and clinics, and may be able to come to your home.

To find a speech-language pathologist near you, visit ProFind .

In the Public Section

- Hearing & Balance

- Speech, Language & Swallowing

- About Health Insurance

- Adding Speech & Hearing Benefits

- Advocacy & Outreach

- Find a Professional

- Advertising Disclaimer

- Advertise with us

ASHA Corporate Partners

- Become A Corporate Partner

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) is the national professional, scientific, and credentialing association for 234,000 members, certificate holders, and affiliates who are audiologists; speech-language pathologists; speech, language, and hearing scientists; audiology and speech-language pathology assistants; and students.

- All ASHA Websites

- Work at ASHA

- Marketing Solutions

Information For

Get involved.

- ASHA Community

- Become a Mentor

- Become a Volunteer

- Special Interest Groups (SIGs)

Connect With ASHA

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association 2200 Research Blvd., Rockville, MD 20850 Members: 800-498-2071 Non-Member: 800-638-8255

MORE WAYS TO CONNECT

Media Resources

- Press Queries

Site Help | A–Z Topic Index | Privacy Statement | Terms of Use © 1997- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association

Speaking and Writing: Similarities and Differences

by Alan | May 2, 2017 | Communication skills , public speaking , writing

Similarities and Differences Between Speaking and Writing

There are many similarities between speaking and writing. While I’ve never considered myself a writer by trade, I have long recognized the similarities between writing and speaking. Writing my book was the single best thing I’ve ever done for my business. It solidified our teaching model and clarified and organized our training content better than any other method I’d ever tried.

A few weeks ago I was invited by a client to attend a proposal writing workshop led by Robin Ritchey . Since I had helped with the oral end of proposals, the logic was that I would enjoy (or gain insight) from learning about the writing side. Boy, were they right. Between day one and two, I was asked by the workshop host to give a few thoughts on the similarities of writing to speaking. These insights helped me recognize some weaknesses in my writing and also to see how the two crafts complement each other.

Similarities between Speaking and Writing

Here are some of the similarities I find between speaking and writing:

- Rule #1 – writers are encouraged to speak to the audience and their needs. Speakers should do the same thing.

- Organization, highlight, summary (tell ‘em what you’re going to tell them, tell them, tell them what you told them). Structure helps a reader/listener follow along.

- No long sentences. A written guideline is 12-15 words. Sentences in speaking are the same way. T.O.P. Use punctuation. Short and sweet.

- Make it easy to find what they are looking for (Be as subtle as a sledgehammer!) .

- Avoid wild, unsubstantiated claims. If you are saying the same thing as everyone else, then you aren’t going to stand out.

- Use their language. Avoid internal lingo that only you understand.

- The audience needs to walk away with a repeatable message.

- Iteration and thinking are key to crafting a good message. In writing, this is done through editing. A well prepared speech should undergo the same process. Impromptu is slightly different, but preparing a good structure and knowing a core message is true for all situations.

- Build from an outline; write modularly. Good prose follows from a good structure, expanding details as necessary. Good speakers build from a theme/core message, instead of trying to reduce everything they know into a time slot. It’s a subtle mindset shift that makes all the difference in meeting an audience’s needs.

- Make graphics (visuals) have a point. Whether it’s a table, figure, or slide, it needs to have a point. Project schedule is not a point. Network diagram is not a point. Make the “action caption” – what is the visual trying to say? – first, then add the visual support.

- Find strong words. My editor once told me, “ An adverb means you have a weak verb. ” In the workshop, a participant said, “ You are allowed one adverb per document. ” Same is true in speaking – the more powerful your words, the more impact they will have. Really (oops, there was mine).

- Explain data, don’t rely on how obvious it is. Subtlety doesn’t work.

Differences between Speaking and Writing

There are also differences. Here are three elements of speaking that don’t translate well to (business) writing:

- Readers have some inherent desire to read. They picked up your book, proposal, white paper, or letter and thus have some motivation. Listeners frequently do not have that motivation, so it is incumbent on the speaker to earn attention, and do so quickly. Writers can get right to the point. Speakers need to get attention before declaring the point.

- Emotion is far easier to interpret from a speaker than an author. In business writing, I would coach a writer to avoid emotion. While it is a motivating factor in any decision, you cannot accurately rely on the interpretation of sarcasm, humor, sympathy, or fear to be consistent across audience groups. Speakers can display emotion through gestures, voice intonations, and facial expressions to get a far greater response. It is interesting to note that these skills are also the most neglected in speakers I observe – it apparently isn’t natural, but it is possible.

- Lastly, a speaker gets the benefit of a live response. She can answer questions, or respond to a quizzical look. She can spend more time in one area and speed through another based on audience reaction. And this also can bring an energy to the speech that helps the emotion we just talked about. With the good comes the bad. A live audience frequently brings with it fear and insecurity – and another channel of behaviors to monitor and control.

Speaking and writing are both subsets of the larger skill of communicating. Improving communication gives you more impact and influence. And improving is something anyone can do! Improve your speaking skills at our Powerful, Persuasive Speaking Workshop and improve your writing skills at our Creating Powerful, Persuasive Content Workshop .

Communication matters. What are you saying?

This article was published in the May 2017 edition of our monthly speaking tips email, Communication Matters. Have speaking tips like these delivered straight to your inbox every month. Sign up today and receive our FREE download, “Twelve Tips that will Save You from Making a Bad Presentation.” You can unsubscribe at any time.

Enter your email for once monthly speaking tips straight to your inbox…

GET FREE DOWNLOAD “Twelve Tips that will Save You from Making a Bad Presentation” when you sign up. We only collect, use and process your data according to the terms of our privacy policy .

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Recent posts.

- Reading Scripts

- Your First Words

- The Problem with “Them”

- Same Old Same Ol’

- I Don’t Have Time to Prepare

- Don’t Sound like you’re Reading

- Bad PowerPoint

- Desperate Times, Desperate Measures

- Three Phrases to Avoid When Trying to Convince

Enter your email for once monthly speaking tips straight to your inbox!

FREE eBOOK DOWNLOAD when you sign up . We only collect, use and process your data according to the terms of our privacy policy.

Thanks. Your tips are on the way!

MillsWyck Communications

Pin It on Pinterest

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- The four main types of essay | Quick guide with examples

The Four Main Types of Essay | Quick Guide with Examples

Published on September 4, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An essay is a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade. There are many different types of essay, but they are often defined in four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive essays.

Argumentative and expository essays are focused on conveying information and making clear points, while narrative and descriptive essays are about exercising creativity and writing in an interesting way. At university level, argumentative essays are the most common type.

| Essay type | Skills tested | Example prompt |

|---|---|---|

| Has the rise of the internet had a positive or negative impact on education? | ||

| Explain how the invention of the printing press changed European society in the 15th century. | ||

| Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself. | ||

| Describe an object that has sentimental value for you. |

In high school and college, you will also often have to write textual analysis essays, which test your skills in close reading and interpretation.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Argumentative essays, expository essays, narrative essays, descriptive essays, textual analysis essays, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about types of essays.

An argumentative essay presents an extended, evidence-based argument. It requires a strong thesis statement —a clearly defined stance on your topic. Your aim is to convince the reader of your thesis using evidence (such as quotations ) and analysis.

Argumentative essays test your ability to research and present your own position on a topic. This is the most common type of essay at college level—most papers you write will involve some kind of argumentation.

The essay is divided into an introduction, body, and conclusion:

- The introduction provides your topic and thesis statement

- The body presents your evidence and arguments

- The conclusion summarizes your argument and emphasizes its importance

The example below is a paragraph from the body of an argumentative essay about the effects of the internet on education. Mouse over it to learn more.

A common frustration for teachers is students’ use of Wikipedia as a source in their writing. Its prevalence among students is not exaggerated; a survey found that the vast majority of the students surveyed used Wikipedia (Head & Eisenberg, 2010). An article in The Guardian stresses a common objection to its use: “a reliance on Wikipedia can discourage students from engaging with genuine academic writing” (Coomer, 2013). Teachers are clearly not mistaken in viewing Wikipedia usage as ubiquitous among their students; but the claim that it discourages engagement with academic sources requires further investigation. This point is treated as self-evident by many teachers, but Wikipedia itself explicitly encourages students to look into other sources. Its articles often provide references to academic publications and include warning notes where citations are missing; the site’s own guidelines for research make clear that it should be used as a starting point, emphasizing that users should always “read the references and check whether they really do support what the article says” (“Wikipedia:Researching with Wikipedia,” 2020). Indeed, for many students, Wikipedia is their first encounter with the concepts of citation and referencing. The use of Wikipedia therefore has a positive side that merits deeper consideration than it often receives.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

An expository essay provides a clear, focused explanation of a topic. It doesn’t require an original argument, just a balanced and well-organized view of the topic.

Expository essays test your familiarity with a topic and your ability to organize and convey information. They are commonly assigned at high school or in exam questions at college level.

The introduction of an expository essay states your topic and provides some general background, the body presents the details, and the conclusion summarizes the information presented.

A typical body paragraph from an expository essay about the invention of the printing press is shown below. Mouse over it to learn more.

The invention of the printing press in 1440 changed this situation dramatically. Johannes Gutenberg, who had worked as a goldsmith, used his knowledge of metals in the design of the press. He made his type from an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, whose durability allowed for the reliable production of high-quality books. This new technology allowed texts to be reproduced and disseminated on a much larger scale than was previously possible. The Gutenberg Bible appeared in the 1450s, and a large number of printing presses sprang up across the continent in the following decades. Gutenberg’s invention rapidly transformed cultural production in Europe; among other things, it would lead to the Protestant Reformation.

A narrative essay is one that tells a story. This is usually a story about a personal experience you had, but it may also be an imaginative exploration of something you have not experienced.

Narrative essays test your ability to build up a narrative in an engaging, well-structured way. They are much more personal and creative than other kinds of academic writing . Writing a personal statement for an application requires the same skills as a narrative essay.

A narrative essay isn’t strictly divided into introduction, body, and conclusion, but it should still begin by setting up the narrative and finish by expressing the point of the story—what you learned from your experience, or why it made an impression on you.

Mouse over the example below, a short narrative essay responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” to explore its structure.

Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class.

Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different.

A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones.

The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind.

A descriptive essay provides a detailed sensory description of something. Like narrative essays, they allow you to be more creative than most academic writing, but they are more tightly focused than narrative essays. You might describe a specific place or object, rather than telling a whole story.

Descriptive essays test your ability to use language creatively, making striking word choices to convey a memorable picture of what you’re describing.

A descriptive essay can be quite loosely structured, though it should usually begin by introducing the object of your description and end by drawing an overall picture of it. The important thing is to use careful word choices and figurative language to create an original description of your object.

Mouse over the example below, a response to the prompt “Describe a place you love to spend time in,” to learn more about descriptive essays.

On Sunday afternoons I like to spend my time in the garden behind my house. The garden is narrow but long, a corridor of green extending from the back of the house, and I sit on a lawn chair at the far end to read and relax. I am in my small peaceful paradise: the shade of the tree, the feel of the grass on my feet, the gentle activity of the fish in the pond beside me.

My cat crosses the garden nimbly and leaps onto the fence to survey it from above. From his perch he can watch over his little kingdom and keep an eye on the neighbours. He does this until the barking of next door’s dog scares him from his post and he bolts for the cat flap to govern from the safety of the kitchen.

With that, I am left alone with the fish, whose whole world is the pond by my feet. The fish explore the pond every day as if for the first time, prodding and inspecting every stone. I sometimes feel the same about sitting here in the garden; I know the place better than anyone, but whenever I return I still feel compelled to pay attention to all its details and novelties—a new bird perched in the tree, the growth of the grass, and the movement of the insects it shelters…

Sitting out in the garden, I feel serene. I feel at home. And yet I always feel there is more to discover. The bounds of my garden may be small, but there is a whole world contained within it, and it is one I will never get tired of inhabiting.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Though every essay type tests your writing skills, some essays also test your ability to read carefully and critically. In a textual analysis essay, you don’t just present information on a topic, but closely analyze a text to explain how it achieves certain effects.

Rhetorical analysis

A rhetorical analysis looks at a persuasive text (e.g. a speech, an essay, a political cartoon) in terms of the rhetorical devices it uses, and evaluates their effectiveness.

The goal is not to state whether you agree with the author’s argument but to look at how they have constructed it.

The introduction of a rhetorical analysis presents the text, some background information, and your thesis statement; the body comprises the analysis itself; and the conclusion wraps up your analysis of the text, emphasizing its relevance to broader concerns.

The example below is from a rhetorical analysis of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech . Mouse over it to learn more.

King’s speech is infused with prophetic language throughout. Even before the famous “dream” part of the speech, King’s language consistently strikes a prophetic tone. He refers to the Lincoln Memorial as a “hallowed spot” and speaks of rising “from the dark and desolate valley of segregation” to “make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” The assumption of this prophetic voice constitutes the text’s strongest ethical appeal; after linking himself with political figures like Lincoln and the Founding Fathers, King’s ethos adopts a distinctly religious tone, recalling Biblical prophets and preachers of change from across history. This adds significant force to his words; standing before an audience of hundreds of thousands, he states not just what the future should be, but what it will be: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” This warning is almost apocalyptic in tone, though it concludes with the positive image of the “bright day of justice.” The power of King’s rhetoric thus stems not only from the pathos of his vision of a brighter future, but from the ethos of the prophetic voice he adopts in expressing this vision.

Literary analysis

A literary analysis essay presents a close reading of a work of literature—e.g. a poem or novel—to explore the choices made by the author and how they help to convey the text’s theme. It is not simply a book report or a review, but an in-depth interpretation of the text.

Literary analysis looks at things like setting, characters, themes, and figurative language. The goal is to closely analyze what the author conveys and how.

The introduction of a literary analysis essay presents the text and background, and provides your thesis statement; the body consists of close readings of the text with quotations and analysis in support of your argument; and the conclusion emphasizes what your approach tells us about the text.

Mouse over the example below, the introduction to a literary analysis essay on Frankenstein , to learn more.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

At high school and in composition classes at university, you’ll often be told to write a specific type of essay , but you might also just be given prompts.

Look for keywords in these prompts that suggest a certain approach: The word “explain” suggests you should write an expository essay , while the word “describe” implies a descriptive essay . An argumentative essay might be prompted with the word “assess” or “argue.”

The vast majority of essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Almost all academic writing involves building up an argument, though other types of essay might be assigned in composition classes.

Essays can present arguments about all kinds of different topics. For example:

- In a literary analysis essay, you might make an argument for a specific interpretation of a text

- In a history essay, you might present an argument for the importance of a particular event

- In a politics essay, you might argue for the validity of a certain political theory

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). The Four Main Types of Essay | Quick Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 19, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/essay-types/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, how to write an expository essay, how to write an essay outline | guidelines & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

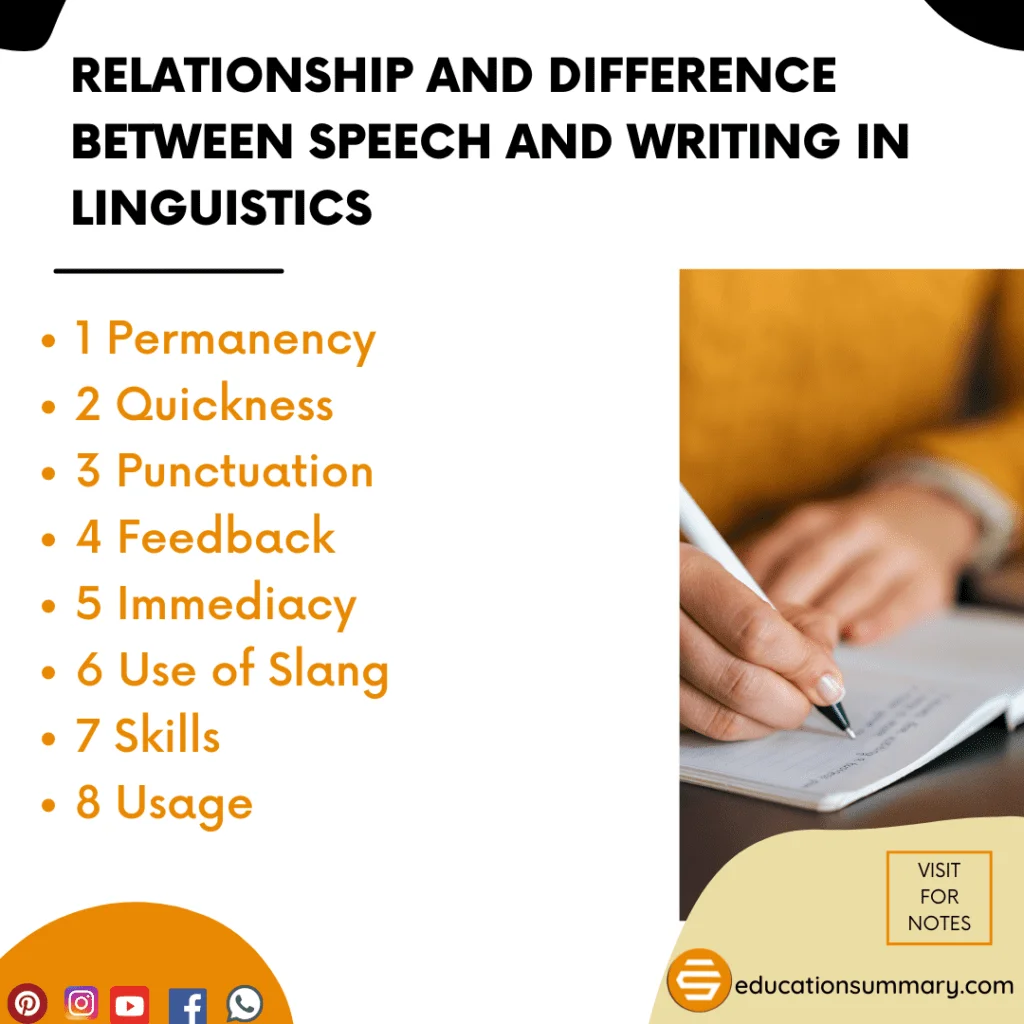

Relationship and Difference Between Speech and Writing in Linguistics

Back to: Pedagogy of English- Unit 4