POLYAS Election Glossary

We provide explanations and background information on elections, voting rights and digital democracy

Joint Chiefs of Staff

Voter Education

Voter education means providing citizens of a democracy with basic information about participating in elections. Voter education is often provided by the state itself, often through a national electoral commission, so it is therefore important that it is politically non-partisan. Government departments that focus on voter education are often highly scrutinized by a third party. In addition, there are various private institutions whose mission it is to strengthen democratic values by increasing voter education. The focus is often on how to vote rather than who to vote for. An appropriate voter education would provide citizens with knowledge regarding:

- How to register to vote – most democracies require citizens to first register as a prerequisite to voting in elections or referenda

- How to complete ballot papers – filling out ballots incorrectly can mean an individual’s vote is misrepresented in the final count or counted as invalid . Therefore, clearly demonstrating how ballots are to be correctly filled out is essential

- The electoral system – it is important that citizens know how their votes will contribute to the final result in an election. Is the election conducted under a system of proportional representation or first past the post ? Does it involve a more complicated preferential voting system?

- Proportional representation in the election glossary

- First Past the Post explained in the Election Glossary!

- Electoral System explained in the Election Glossary!

Online Voting

How it works!

Live Voting

About POLYAS

Digital Democracy

Sign up for free

The Role of Voter Education in Strengthening Democracy

“Democracy in the contemporary world demands, among other things, an educated and informed people.” ~ Elizabeth Bishop “The control of information is something the elite always does, particularly in a despotic form of government. Information, knowledge, is power. If you can control information, you can control people.” ~ Tom Clancy

In the information age, when the fate of nations hinges on the choices of their citizens, voter education emerges as a beacon of hope. It’s not just an accessory to the democratic process, but rather the cornerstone upon which a thriving democracy is built.

However, this is also an era of rapidly evolving political landscapes and information overload. In such an environment, the importance of voter education cannot be overstated. When we understand how voter education empowers citizens and strengthens democracy — and apply that knowledge at the ballot box — we ensure that the voices of the people truly guide the course of our country.

Read on to learn more about the significance of voter education and the state of civic education in America.

What Does Voter Education Mean?

Voter education comes in many forms. It starts with a basic understanding of civics and how our electoral system is supposed to work, and it extends to researching candidates and issues before we cast our votes.

How many times have you looked at a ballot and wondered who half of the candidates are and what they stand for? It’s no longer enough to look at a D or an R behind a name. There are many more choices on a ballot than whichever establishment candidate is running for president.

For example:

What is the function of a Secretary of State?

What does a circuit court judge do, and what is the record of the people running for this position in your area?

Who are your local school board candidates and how do they affect public education?

What are the ballot initiatives and how might they impact your life?

These questions are much more fundamental to your everyday quality of life, and most people can't answer them.

For example, the right to work seems like a people-powered concept, but a careful reading of what’s in Right to Work proposals will uncover that they are actually pro-business and anti-union. Whether you’re a business owner or a worker, that distinction is fundamental to how you choose to vote on such a proposal.

Join the GoodParty.org Discord

Voter Education and Candidate Research

Voter education takes various forms to ensure that citizens are well-prepared to perform their civic duties. For example, general voter education focuses on the foundational knowledge needed to navigate the electoral process.

It includes:

Understanding the election timeline, such as key dates like voter registration deadlines, primary elections, and general elections.

Voter registration procedures like how to register to vote or update voter information.

The mechanics of voting, including how to cast a ballot, where to vote, and what to expect at the polling place.

Knowing the difference between primary, general, and special elections, and understanding their significance

Beyond the basics, voter education should equip citizens with the skills to thoroughly research candidates and their policy positions. This includes:

Candidate profiles : Accessing information about candidates running for various offices, including their background, experience, and priorities.

Policy analysis : Using tools and resources to help voters assess the policy platforms of candidates and parties.

Fact-checking and media literacy: Learning how to discern credible sources of information and identify misinformation.

Candidate forums and debates : Participating in forums where candidates discuss their views and answer questions from the public.

By providing citizens with these essential types of voter education, we empower them to make informed decisions and actively participate in the democratic process. In the current climate of abundant and easily manipulated information, these skills are more critical than ever.

The State of Voter Education in America

Ours is a country that prides itself on the power of the people. As such, the saying that knowledge is power couldn’t be more true.

However, the state of civic education in America demonstrates that we are giving that power away. The earlier we learn basic civics, the better informed and engaged we are as a country.

Unfortunately, most Americans couldn’t pass a standard civics test . While many states do require civics classes at the high school level, there is no federal mandate requiring education in civics .

Many Americans don’t formally study civics or political science until they’re in college, if at all.

According to data collected from state departments of education and the Education Commission of the States:

Only nine states and Washington, D.C. schools require a full year of civics to graduate from high school

30 states require one semester of civics

11 states have no civics requirement for graduation

States with the highest rates of youth civic engagement also prioritize civics education

Here are four big reasons why voting matters , and why voter education matters more:

#1: Voting is the Foundation of Democracy

Democracy, as it’s known today, traces its roots to ancient Greece. It’s a system of government where power rests with the people, and they exercise it through periodic elections. However, for democracy to function, an informed and engaged electorate is required.

The United States is a representative democracy , and this complicates matters somewhat. As we’ve seen over the past three years, knowledge of how our electoral system works is critical to ensuring that our voices are truly heard and that the people we entrust to represent our interests are doing so in an honest, transparent manner.

This is where voter education steps in as a fundamental requirement.

#2: Voting Means Empowering Citizens

Voter education is akin to the proverbial key that unlocks the door to active participation in the democratic process. When citizens are well-informed about their rights, responsibilities, and the issues at stake, they become more confident and motivated to engage in the electoral process.

This extends to:

Knowledge of Rights and Responsibilities: Voter education provides knowledge about the rights and responsibilities of citizens. Understanding the electoral system, voter registration procedures, and how to cast a vote ensures that citizens can fully exercise their power without intimidation or confusion.

Informed Decision-Making: Informed voters make better choices. They’re better equipped to evaluate candidates, parties, and their policy positions critically. This leads to a more enlightened electorate that selects their representatives based on merit and alignment with their values rather than being swayed by personalities, empty promises, or divisive rhetoric.

Civic Engagement: Voter education extends beyond the act of voting. It encourages citizens to actively participate in civic life while fostering a sense of community and shared responsibility for the well-being of society. This can include volunteering, attending town hall meetings, and advocating for causes they believe in.

#3: Voting Strengthens Democracy

A well-informed electorate is the bedrock of a strong and resilient democracy. Here are four ways in which voter education contributes to the overall health of our democratic institutions:

Accountability : Elected officials are more likely to be held accountable when voters are educated. Citizens can monitor their representatives' actions, assess their performance, and vote them out if they fail to deliver on their promises or act against the public interest.

Reduced Polarization: Voter education encourages rational discourse and informed decision-making. When citizens understand the nuances of various issues, they are less susceptible to the polarization driven by sensationalism and misinformation.

Inclusivity: Voter education promotes inclusivity by ensuring that all eligible citizens have access to information about the electoral process. It helps bridge the gap between different socio-economic groups, reducing the risk of marginalized communities being disenfranchised.

Long-Term Planning: Educated voters are more likely to support policies that have long-term benefits for society, rather than short-sighted solutions. This contributes to the stability and sustainability of a nation.

#4: Voting Ensures that the Voices of the People Are Heard

One of the central tenets of democracy is that it should reflect the will of the people. However, this can only happen if every citizen's voice is heard and their vote counts.

Voter education plays a pivotal role in ensuring that the democratic process remains inclusive and representative by:

Mitigating Voter Suppression: In some cases, voter suppression tactics are employed to prevent certain groups from voting. Voter education can help citizens recognize and resist such tactics, safeguarding the integrity of the electoral process.

Countering Disinformation: In an age of digital misinformation, voter education is a powerful antidote. It equips citizens with the critical thinking skills needed to discern credible information from fake news, preventing manipulation and misinformation from distorting their decisions.

Increasing Voter Turnout: A well-informed electorate is more likely to turn out to vote. When voter education campaigns are robust and accessible, voter turnout tends to increase, leading to a more representative democracy.

Join Our Community of Independent Voters and Candidates

Voter education is the lynchpin that holds our democracy together. It empowers citizens, strengthens democratic institutions, and ensures that the voices of the people are able to shape the destiny of their nation. In a world where information is everywhere but often misleading, voter education steers us towards a more just and equitable society.

The true power of democracy lies not just in the act of voting, but in the informed choices we make at the ballot box. Voter education isn’t a luxury; it’s a necessity.

Learn more about the choices that make our country more progressive, functional, and inclusive. GoodParty.org offers a treasure trove of candidate resources and information about exciting independent candidates running for office at all levels of government.

Talking Elections: Voter Education

By Claire DeSoi 10.27.2020

https://electionlab.mit.edu/articles/talking-elections-voter-education

Shining Stars

Expectations.

In Episode 3 of our video series Talking Elections , we wanted to take a look at voter education which is an important topic that doesn’t get enough notice in the elections community. There is a lot of information that voters need to know to vote and have their votes counted accurately, from registration deadlines and the documentation they might need to register to the location of polling places, voter identification requirements and how to properly mark their ballots as they’re counted.

There are special challenges in voting in the midst of Covid where things are changing so fast — especially on an emergency basis sometimes within hours of the polls opening. This is why this topic is so relevant now.

We were joined by three guests on this episode: Mara Suttmann-Lea of Connecticut College, Lia Merivaki of Mississippi State, and Veronica Degraffenreid of the Pennsylvania Department of State.

What are the challenges that state and local officials face when they design and implement voter education efforts?

Mara: Lia and I have both worked in mapping out what voter education looks like across the states, and it has proven to be a challenging endeavor in and of itself. But there are a couple of things that we have noticed during our research and also just in our conversations that we have with local election officials and state election officials. There is a lack of resources for implementing high-quality voter education plans. This is something that we’ve seen in some of the state statutes. We look at questions about whether mandates for voter education at the local level are funded, but it’s also come up just in conversations that we’ve had with local election officials: about dealing with unfunded mandates for voter education. The centralization, or lack thereof, of authority over voter education within a given state can also be a potential challenge. Oversight and implementing voter education plans can be difficult in states with localities that have a lot of autonomy from their state governments (here in Connecticut that’s the case). Of course some amount of flexibility is needed because different jurisdictions have different needs, but that lack of centralization can be a potential challenge as well.

Also, looking at the scope of voter education across the United States for assessing the quality of voter education as a whole, there’s really a lack of consistency and what those policies look like and having a baseline definition standard of voter education so voters are going to experience a lot of variation in the types of education that they have access to depending on where they live. Of course, this isn’t surprising given what we know about how decentralized election administration is in the United States, but it is something that is worth noting if we think of voter education is something that every voter should have access to.

What are some exemplary efforts of voter education that others can emulate?

Lia: Just a disclaimer: what is reported is most likely a small fraction of what is actually happening across the states and at the local level because we cannot possibly know and collect all the information that is necessary to make an assessment right. And states don’t really need to reinvent the wheel; we know that there are some things that work, and if done consistently, they can make a difference.

For example, small efforts such as a PSA announcement or printing an ad with a local newspaper or radio — those are standard things that we should expect localities are doing but we’re not really sure they are done uniformly, mainly because of resources.

Some exemplary things that we have observed as a minimum intervention includes sending information to voters before Election Day. That seems intuitive, but it might not be. Of course, you might have to deal with issues with mail returning and that starts a chain of events.

Social media presence: we have seen there are some localities that have been active on social media and they’re out in the community. Voters reach out to their local officials and those officials respond. Now there have been some initiatives to include the community broadly defined, like connecting with local high schools, holding registration drives, and working with other organizations. Connecticut is one of the states that has a competition for high schools to do registration drives. Trying to bring the community along — that’s a great example of how states can build these partnerships and local resources.

Voters rely on their local elected officials and we know that from research that voters trust their local election officials and they seek them for information. So being out there, being proactive and reaching out to the community — we have found these small interventions have been fruitful. Being on the loop constantly is necessary because we have seen that there are some efforts to spread some misinformation or some inaccurate information regardless of the intentions. So local officials have to find a way to be on top of it, to get control over the information flow, because that appears to be the biggest challenge.

In terms of voter education there are many things that can be done and the lack of definition is it challenge but at the same time, states and localities have tools that they can use without necessarily thinking outside the box that “oh we have to find that strategy and that recipe to get everyone at the same time” and that’s easier said than done because voters need different things and they can be reached out in different ways.

What strategies have you pursued to get important information out to voters about how things have changed in the midst of the fact that Pennsylvania voting modes were going to be changing anyway?

Veronica: There was historic legislation in Pennsylvania in 2019, which is one of the reasons why I came for a new challenge for myself professionally. They’re going to be doing a lot of new things in this state. Voter outreach and education were very much on the minds of the staff here at the Pennsylvania Department of State.

In 2019, with that historic legislation, all registered Pennsylvania voters can now apply for a mail-in ballot without needing to have an excuse, and they can vote from the comfort of their home. Since this method of voting is new to Pennsylvania, this state was already very much engaged in a program called #Ready2Vote. It wasn’t just an afterthought. We were also helping to educate voters about new voting systems, so those things were already happening prior to the change of the primary. Now, with the change of the primary date, certainly our outreach not only included educating voters about the new voting method but also about letting voters know about the date change and then also what efforts counties would be taking to keep voters and poll workers safe on Election Day, in response to Covid-19.

Voting by mail became even more critical with respect to our outreach as it was the way that voters, if they felt uncomfortable about voting in person on Election Day, could apply for a mail-in ballot. The voter can vote from the comfort of their home.

There’s a dedicated outreach team here with the Pennsylvania Department of State. We meet weekly with other interdepartmental staff, and we discuss and strategize on our outreach efforts. It is part of the business model so that we can quickly adapt as needed and it makes us responsive to our community.

One of the things that we did specifically right after the change of the primary date was update the website because that is the place that most people visit if they want to know what’s happening. Key details included: register to vote on time, request a ballot on time, and now because we’re getting close to that primary date, return your ballot by the deadline.

We quickly adapted our targeted media campaign so that included TV and radio. We mailed a postcard to Pennsylvania households informing them about the new primary date and the option of voting by mail and how to apply online for this.

Social media are part of our campaign efforts. We created a neat unboxing video. If you have kids you know exactly what that is, like open up the make-up or open up the new iPhone to see what that experience is. We recorded a similar video to help educate voters about what to expect when they get their ballot in the mail: what’s in the envelope and then of course what to do with the materials in the envelope and how to return their ballot and with it the effort of do it correctly so it will be counted and send it in on time.

New to our Department are webinars that we’ve been putting out kind of like this because we can no longer go in person and do presentations. Leveraging the use of technology is important. Things have changed in recent years since I first started in elections, so this state is developing methods of sending targeted emails to voters so voters when they apply for either online voter registration or requesting their ballot, they can opt in to receive emails. We also inform voters by email to track that process — i.e., “okay we got your application,” “it’s been processed,” “your ballot is in the mail,” “we got your ballot.” Even now because we’re so close to the election we’re sending targeted emails to voters who have requested a ballot and who have not yet returned their ballot to let them know that we need for you to get your ballot back in time and that the deadline is coming up.

When thinking ahead to education for November, what are you learning from this round that you think can be applied? What new and different sorts of things will get implemented in approaching the general election?

Veronica: We’re going to continue to do what we’ve been doing. Part of that is just adapting to change, and certainly listening to the needs of our community and the counties. Our strategy is to always be poised, to be nimble enough to quickly get information out when the information is needed just in time, but being poised to do that quickly. We have an outreach team. We will continue to educate voters about mail-in voting as well as the things that they can do to stay safe even throughout the general election year.

Some new things that we’re considering is maybe adding text messaging after the primary, and we have begun to use trusted validators so that they can help get the message out and so that includes using election officials or athletes or businesses to help expand on that vote-by-mail effort. Pennsylvania’s new law allows for us to continue to know that we have to continue to get information out because there’s so many new things that are in Pennsylvania’s law for this year, and so we’ll continue to do those efforts throughout 2020.

Claire DeSoi is the communications director for the MIT Election Data + Science Lab.

Back to Main

Related Articles

Retaining Election Officials in a Time of Uncertainty

Evaluating Practitioner Interventions to Increase Trust in Elections

By Jennifer Gaudette, Seth Hill, Thad Kousser, Mackenzie Lockhart, and Mindy Romero

Civics Education Helps Create Young Voters and Activists

Youth voter turnout is notoriously low in the U.S., especially when social-studies classes are notably absent.

It’s widely known that young adults in the United States tend to vote at lower rates than older Americans, but it’s easy to gloss over just how stunning the numbers really are—especially at a time of such intense political polarization and divisiveness. Only half of eligible adults between the ages of 18 and 29 voted in the 2016 presidential election that sent Donald Trump to the White House. During the 2014 midterm elections two years earlier, the youth-voter-turnout rate was just 20 percent, the lowest ever recorded in history, according to an analysis of Census data .

These troubling voting rates follow decades of declining civics education. Starting in the 1960s, robust civics instruction , which usually took place through three standard high-school courses, started to atrophy. It’s likely not a coincidence, then, given evidence suggesting a link between civics education and voter participation, that the 1960s coincided with a slump in the rate of young adults who cast ballots.

The history of young people and voter turnout in America

A newly released survey by the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation illustrates the sorry state of civics education today: Just one in three Americans would pass the U.S. citizenship test. It’s not a test known for its difficulty: The vast majority of citizenship-seeking immigrants pass easily. (A real question on the test: “Identify whether Rhode Island, Oregon, Maine, or South Dakota is a state that borders Canada.”) Only 13 percent of the 1,000 survey respondents, nearly all American-born, could say when the Constitution was ratified (1788, if you were wondering), and fewer than half could identify which countries the U.S. fought against in World War II. Among the most egregious examples from the survey: Two percent of respondents identified climate change as the cause of the Cold War.

According to a report published earlier this year, just nine states and the District of Columbia require one year of government or civics classes in high school. But beyond that, most existing civics-education efforts focus on kids in high school and college who are of voting age or close to it—not younger children. For example, one of the most high-profile national initiatives to improve civics education in recent years has homed in on the tail end of the K–12 trajectory, seeking to make passage of the U.S.-citizenship test a graduation requirement nationwide . Today, 29 states have some kind of citizenship-test law on the books, according to Lucian Spataro, the CEO of the group Civics Education Initiative.

Some observers emphasize that to really ensure that kids learn the importance of civics, schools should start lessons much earlier. Ideally, says Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg of Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, civic engagement should inspire students to translate knowledge about government and policy making into action—from volunteering and community organizing to lobbying and voting. For kids to really understand that connection, advocates say civics learning should start at a young age.

Only a couple of states, such as Florida , have civics-education requirements for middle schoolers, even though that’s when students nationwide take a standardized civics test as part of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Middle school is also a time in students’ educational trajectory that is better structured for such education than later stages, when school becomes broken down into more distinct disciplines that make it difficult to integrate this kind of instruction seamlessly, says Kawashima-Ginsberg. And kids at this age undergo dramatic developmental and intellectual changes that render them particularly ripe for understanding the importance of civics. Likewise, if high school is the first time kids get exposure to the subject matter, teachers may struggle to motivate them. Other advocates go even farther, saying that civics lessons should start as early as kindergarten , when kids begin to read and discuss identity.

This type of early civics education might connect with students more easily if it’s woven into the existing fabric of everyday schooling—for example, into a science lesson on pollution, or a history class where students are learning about Native Americans. Civics shouldn’t just be taught in one separate class; it should be a staple of education, “the lima beans on the curricular plate of the elementary student’s day,” as Paul Fitchett, an education professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, put it in a interview with the education-news outlet Chalkbeat .

That Florida requires schools to introduce civics in elementary school may help to explain why the state has seen steady improvement in students’ civics proficiency: In 2017, 70 percent of seventh-graders passed the state exam, up from 61 percent in 2014. And a Washington Monthly article even attributed the activism of teens at Parkland, Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School—where 17 students were shot and killed in February— to the state’s early civics requirement. In launching a nationwide movement for stronger gun control, wrote the authors Frank Islam and Ed Crego, the students have “been the beneficiaries of what is arguably one of the nation’s most comprehensive and successful efforts to teach civic knowledge and engagement.”

Besides the Parkland teens, young people have been especially enthusiastic about politics of late, but it means little unless they translate it into a trip to the ballot box in November. And the early signs aren’t promising: A recent poll from Gallup indicates that just 26 percent of 18-to-29-year-olds say they intend to vote in the November midterms, compared to 82 percent of Americans 65 and older.

8 reasons why education may be pivotal in the 2020 election (and beyond)

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, douglas n. harris douglas n. harris nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy , professor and chair, department of economics - tulane university @douglasharris99.

June 3, 2019

Among politicos, education is not usually considered a top-tier issue in presidential elections. The issue tends to get overshadowed by other issues where the president is the obvious leader and decisionmaker—defense, security, climate change, health care, Social Security, and economic affairs. Education, in contrast, has been seen as a state and local issue. But times have changed, especially when it comes to Democratic primaries.

It is worth starting with a brief recap of the recent federal role in K-12 education. President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind (NCLB) law in 2001 represented an unprecedented increase in the federal role in K-12 education at the time. President Barack Obama increased the federal role even more—introducing $100 billion in federal education spending (prompted by the financial crisis) and leveraging NCLB to make deals with states that allowed the U.S. Department of Education, through a waiver process, to pressure states to adopt the Obama administration’s preferred accountability-driven policies without getting congressional approval. Indirectly, this gave the federal government a hand in academic standards, which had been previously left to the states, and in teacher evaluation, which few governments, at any level, had ever really tried to touch.

Republicans saw this as executive overreach and Democrats became more disenchanted with the policies themselves, especially their focus on high-stakes testing. This led to the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which pulled federal law back to something closer to, and a bit less aggressive than, the original NCLB (but still more active than the pre-NCLB era). Many long-term members of Congress even recanted their original support for NCLB and their support for ESSA was meant to send just that message.

Given the NCLB-ESSA story, one might think the federal role would fade as a political issue in presidential elections, but this has not happened. In fact, I argue that education might be more important than ever in the 2020 election and for years to come:

1. Education is becoming more important in daily life

In perception and reality, education is becoming more and more important to parents and the long-term life success of their children. It is also a key cog in the macroeconomy, with over $1 trillion in spending annually (mostly from public sources ). These are the underlying forces that led to NCLB and the importance of education has only continued to grow. The sector has simply become too important for politicians at any level to ignore.

2. Early childhood education

Education has increasingly become a pocketbook issue as the share of women in the workforce has increased. Working parents need someone to care for their children, and given what we know about social and cognitive growth in the early years, publicly-funded early childhood education has many potential advantages. Meanwhile, federal policy has been remarkably stagnant, still rooted in LBJ-era policies like Head Start and federal tax credits. The issue is ripe for policy change and offers yet another reason for voters and presidential candidates to pay attention to education. Support for early childhood is very high in polls , with bipartisan appeal.

3. Higher education

The federal government has long played a significant, though quiet, role in funding colleges and universities with Pell Grants, student loans, and regulations. However, as student loan debt has skyrocketed, the federal government is a natural place to look for solutions. While more contentious than early childhood, many of these ideas also poll well across the political spectrum.

4. Tight state budgets

Education—especially any new programs addressing early childhood education and college affordability—requires resources, something in short supply at the state and local levels. Health care and pension benefits are taking on a larger and larger share of state spending. States have also shown a strong inclination to cut higher education first when budgets are tight. The federal government, with its borrowing power, almost has to be involved in any major spending effort.

5. Inequality problems

Inequality is real and fast-rising issue, and one of the key concerns among Democrats. Income inequality is partly caused by unequal educational opportunity (though not as much as some education advocates would have it). Early childhood education is also a factor in gender-based income inequality since child care and early education are central to allowing women—still the primary caregivers—to have equal access to opportunities in the labor market.

6. Political practicality

More so than other issues, because most people interact with public education in some way, education positions can be used to attract support from very specific constituencies. Want to attract younger voters? Promise more money for higher education, like free college and loan forgiveness. Want to attract African-Americans? Support for historically black colleges and universities. Want to attract rural voters? Create a rural education proposal. Want to attract women? Focus on early childhood education. Education is the Swiss army knife of policy and politics.

7. Diploma and Gender Divides

In the early 2000s, voters with more formal education voted fairly equally for Democrats and Republicans. Not anymore —53% of college-educated white voters went for Democrats in 2018 compared with 37% of non-college-educated whites (I could not find the same numbers for people of color or the whole population). It stands to reason that voters with more formal education are especially likely to see education as an important policy issue. Education is also more of a pocketbook issue for women, who also vote disproportionately for Democrats.

8. Betsy DeVos

DeVos is one of the more reviled figures in what is, for Democrats, a highly reviled Trump administration. Her lack of experience in education (especially public schools), early glaring missteps (“guns and bears”?), and strong support for vouchers and online schooling, generally opposed by Democrats, make her an easy target for generic political attacks. (Not that it matters for purposes here, but her ideas also lack research support to recommend them.)

For all of these reasons, education will be a major issue on the minds of Democratic voters. One poll has it among the top five issues for Democratic voters . Only health care beats it (and only slightly). This rising importance may also be long-lasting. The first seven factors above seem like structural changes, unlikely to shift with the political winds. Reinforcing this point, the candidates are coming out with major education policy proposals on an almost daily basis (more to come in later posts).

The rising importance of education as an issue in the party is not the only reason that it will matter more in 2020.

For more on the importance of education in the upcoming election, read this piece that focuses on the state of the Democratic primary and teacher unions.

Related Content

Anna Saavedra, Morgan Polikoff, Dan Silver, Amie Rapaport

March 23, 2021

Robert Kelchen

May 17, 2019

Douglas N. Harris

June 26, 2019

Early Childhood Education Higher Education K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Sana Sinha, Nicolas Zerbino, Jon Valant, Rachel M. Perera

October 10, 2023

Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg

October 6, 2023

Elias Blinkoff, Molly Scott, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek

November 21, 2022

Educating Voters

We host hundreds of events and programs every year to educate voters about candidates in thousands of federal, state and local races, as well as distribute millions of educational materials about state and local elections.

Share this:

Why It Matters

The leaders we elect make decisions that affect our daily lives. Elections are our chance to stand up for what matters most to us and to have an impact on the issues that affect us, our communities, our families and our future.

What We're Doing

We host hundreds of candidate debates and forums across the country each year and provide straightforward information about candidates and ballot issues. Through print and online resources, including VOTE411.org , we equip voters with essential information about the election process in each state, including polling place hours and locations, ballot information, early or absentee voting rules, voter registration deadlines, ID requirements and more.

Take Action

Empower voters with knowledge.

Find election information you need at VOTE411.org

Support our work to empower Americans with knowledge

Spread the word about voting by sharing this page with your friends and family on social media

Join your local or state League to empower voters in your community!

Every June, the League, our partners, and people around the country await the US Supreme Court’s (SCOTUS) opinions on critical issues like access to the ballot, redistricting, reproductive rights, and more. This blog reflects on several end-of-term cases from the last decade or so that have had a major impact on democracy.

This story was originally published in News Now Warsaw on June 19, 2024.

A new group is working to revive efforts to establish a League of Women Voters chapter in Kosciusko County, Indiana.

Heading into the 2024 general elections, access to free, trusted, and unrestricted information will be essential to empowering an informed and engaged electorate. Elections at the federal, state, and local levels will directly affect the communities that libraries serve and the issues their users care about. Access to nonpartisan civic information that breaks down the barriers to ballot casting is critical to ensuring all Americans can engage in the democratic process.

- See More of the League's Latest

Stay Updated

Keep up with the League's voter education efforts.

Donate and support our work

to empower Americans with civic knowledge.

The Importance of the Educated Voter

Posted by Roger Brooks on November 5, 2018

The act of voting is the most important contribution every single eligible voter can make to insure the health of our democracy. Yet year after year, a discouraging number of eligible voters choose not to pull the levers of power. In advance of the midterm elections, Facing History CEO Roger Brooks stops to consider the impact of non-voters, and worse, uninformed voters in an OpEd published on CNN.com:

Electoral no-shows, citizens who choose not to vote, constitute the most powerful bloc in American politics. In the 2016 elections, the 102.7 million no-shows vastly outnumbered the 62.9 million who voted for Donald Trump and the 65.8 million who voted for Hillary Clinton. Educating the electorate is the surest way to increase motivation to turnout so that election results might better match the will of the people.

It’s not elitist to insist on educating voters. Indeed, students who learn about moral reasoning, building arguments and evaluating historical events show significant increases in civic literacy and in rates of voting in America.

Topics: Democracy , voting

Written by Roger Brooks

Subscribe to Email Updates

Recent posts, posts by topic.

- Choosing to Participate (70)

- Facing Technology (69)

- History (67)

- Democracy (62)

- Black History (58)

- Teaching Resources (57)

- Holocaust (54)

- Facing History and Ourselves (52)

- American History (51)

- Facing History Resources (48)

- Identity (48)

- Antisemitism (45)

- Classrooms (45)

- Teaching (45)

- Media Skills (42)

- Teachers (42)

- current events (37)

- Holocaust and Human Behavior (36)

- Online Learning (36)

- Professional Development (35)

- Holocaust Education (33)

- Civil Rights (32)

- Genocide/Collective Violence (32)

- Safe Schools (32)

- Racism (31)

- Human Rights (30)

- To Kill a Mockingbird (30)

- Civil Rights Movement (28)

- Race and Membership (28)

- Student Voices (28)

- Immigration (27)

- Students (27)

- Reading List (26)

- Teaching Strategies (26)

- Upstanders (25)

- Critical Thinking (24)

- Listenwise (24)

- Reconstruction (23)

- Women's History Month (23)

- Facing History Together (22)

- Memory (22)

- School Culture (22)

- Schools (22)

- Survivor Testimony (22)

- EdTech (20)

- Today's News Tomorrow's History (20)

- International (19)

- Armenian Genocide (18)

- Universe of Obligation (18)

- Asian American and Pacific Islander History (17)

- English Language Arts (17)

- Social Media (17)

- genocide (17)

- Flipped Classroom (16)

- Innovative Classrooms (16)

- Native Americans (16)

- Holocaust and Human Behaviour (15)

- Margot Stern Strom Innovation Grants (15)

- Back-To-School (14)

- New York (14)

- civil discourse (14)

- Contests (13)

- Human Behavior (13)

- Empathy (12)

- Bullying (11)

- Neighborhood to Neighborhood (11)

- Community (10)

- Equity in Education (10)

- Events (10)

- Indigenous (10)

- Journalism (10)

- Stereotype (10)

- Voting Rights (10)

- global terrorism (10)

- Community Conversations (9)

- Refugees (9)

- United Kingdom (9)

- difficult conversations (9)

- Bullying and Ostracism (8)

- In the news (8)

- Online Tools (8)

- Reading (8)

- Religious Tolerance (8)

- Webinars (8)

- Common Core State Standards (7)

- Diversity (7)

- Latinx History (7)

- Memorials (7)

- Refugee Crisis (7)

- South Africa (7)

- Upstander (7)

- Webinar (7)

- Writing (7)

- Facing Ferguson (6)

- Jewish Educational Partisan Foundation (6)

- Judgement and Legacy (6)

- Memphis (6)

- Readings (6)

- Social-Emotional Learning (6)

- The Nanjing Atrocities (6)

- Decision-making (5)

- Harper Lee (5)

- Jewish Education Program (5)

- Literature (5)

- Museum Studies (5)

- Public Radio (5)

- Raising Ethical Children (5)

- Sounds of Change (5)

- StoryCorps (5)

- reflection (5)

- Assessment (4)

- Bryan Stevenson (4)

- Common Core (4)

- Cyberbullying (4)

- Learning (4)

- Lesson Plans (4)

- Social Justice (4)

- Social and Emotional Learning (4)

- Teaching Strategy (4)

- We and They (4)

- international holocaust remembrance day (4)

- Beacon Academy (3)

- Benjamin B. Ferencz (3)

- Cleveland (3)

- Eugenics/Race Science (3)

- Experiential education (3)

- IWitness (3)

- Indigenous History (3)

- Japanese American Incarceration (3)

- Photography (3)

- Restorative Justice (3)

- Roger Brooks (3)

- Salvaged Pages (3)

- The BULLY Project (3)

- The Great Listen (3)

- Twitter (3)

- media literacy (3)

- news literacy (3)

- student activism (3)

- transgender (3)

- white supremacy (3)

- workshop (3)

- Black History Month (2)

- Brussels (2)

- Bystander (2)

- Chicago (2)

- Civil War (2)

- David Isay (2)

- Day of Learning (2)

- Digital Divide (2)

- Essay Contest (2)

- Facing History Library (2)

- Giving Tuesday (2)

- Go Set a Watchman (2)

- International Justice (2)

- Lesson Plan (2)

- Los Angeles (2)

- Lynsey Addario (2)

- Margaret Stohl (2)

- New York Times (2)

- Northern Ireland (2)

- Online Workshop (2)

- Parents (2)

- Partisans (2)

- San Francisco Bay Area (2)

- September 11 (2)

- Shikaya (2)

- Slavery (2)

- Sonia Nazario (2)

- Spoken Word (2)

- The Allstate Foundation (2)

- Toronto (2)

- Weimar Republic (2)

- Zaption (2)

- civic education (2)

- climate change (2)

- environmental justice (2)

- islamophobia (2)

- primary sources (2)

- resistance (2)

- Auschwitz (1)

- Black Teachers (1)

- Brave Space (1)

- Cambodia (1)

- Canadian History (1)

- Caregivers (1)

- Colombia (1)

- Deborah Prothrow-Stith (1)

- Desegregation (1)

- Don Cheadle (1)

- Douglas Blackmon (1)

- Explorations (1)

- Farewell to Manzanar (1)

- Haitian Revolution (1)

- Hurricane Katrina (1)

- Indigenous Peoples' Day (1)

- Insider (1)

- International Women's Day (1)

- Isabel Wilkerson (1)

- Latin America (1)

- Lesson Ideas (1)

- Literacy Design Collaborative (1)

- Marc Skvirsky (1)

- Margot Stern Strom (1)

- Memorial (1)

- Mental Health Awareness (1)

- Race and Membership in American History: Eugenics (1)

- Reach Higher Initiative (1)

- Rebuke to Bigotry (1)

- Red Scarf Girl (1)

- Religion (1)

- Residential Schools (1)

- Socratic Seminar (1)

- Summer Seminar (1)

- Truth and Reconciliation (1)

- Urban Education (1)

- Using Technology (1)

- Vichy Regime (1)

- Wes Moore (1)

- Whole School Work (1)

- anti-Muslim (1)

- archives (1)

- coming-of-age literature (1)

- cross curricular teaching and learning (1)

- differentiated instruction (1)

- facing history pedagogy (1)

- literacy (1)

- little rock 9 (1)

- new website (1)

- xenophobia (1)

Voter education is more important than ever before

Gerald Sastra/The Cougar

The 2020 presidential election is coming up and as voters, our voices have a right to be heard. It’s important that we vote and act based on facts over opinions so that we can accurately vote and make a decision that will benefit us and our country in the long run.

The best way to do this is to educate ourselves on politics, the voting process, the candidates and the issues surrounding the election so that we know what we are getting ourselves into when we show up to vote.

This is called voter education and it is a vital step in voting because when we vote, we are ultimately deciding the future of not only ourselves, but our country and those around us.

Facts over bias

Yes, voting is ultimately making a decision based on your specific opinions or bias, but oftentimes, people have preconceived opinions about certain topics and issues in which they only pay attention to how they as an individual will be affected.

In reality, it’s the whole country and a large population of people who are affected.

This is why it is crucial that every voter makes an effort to educate themselves on politics. It doesn’t hurt to listen to differing opinions from yours, unless they are truly discriminatory and destructive.

Going out of your way to explore different opinions on varying issues can often be eye opening because you get the opportunity to learn why some people have certain beliefs.

Additionally, you can have very insightful conversations with others in which you can see things from new perspectives.

However, just listening to other perspectives as well as your own isn’t enough to be an educated voter. This is where the internet, teachers and even textbooks come into play.

Being an educated and successful voter calls for some background knowledge on the voting process and the issues surrounding the election.

This means that people should take some time out of their days to simply search, “things I need to know about the 2020 election” or even just “things to know before I vote.”

Opening a textbook or reaching out to professors won’t hurt anyone, in fact, it will most likely help you and the people around you because it allows for people to become enlightened so that everyone can make educated and well thought out decisions for something as important as the future of our country.

2020 Presidential Election

It is important to be an active voter and participate in every election, or as many as possible, but it’s no secret that voter turnout is typically higher when it comes to presidential elections.

This year on Nov. 3, our presidential election is to be held.

Although time is running out to both register to vote and to educate yourselves on the different aspects of politics and voting, it definitely is not too late to do either.

Politics essentially run our country and as eligible voters, it’s important that people take advantage of their right to vote and make the most out of it through educating ourselves and those around us.

Kimberly Argueta is a political science freshman who can be reached at [email protected]

You may also like

Pride discourse is counterproductive to its mission

Felons should not be allowed to serve as president

UH dorms are not worth the rising price tags

AI art in advertisements is unethical, unwanted

More students need to know their free speech rights

More UH students should be able to learn about genocide

Leave a comment x.

- Open Search Search

- Information for Information For

Youth Who Learned about Voting in High School More Likely to Become Informed and Engaged Voters

The 2020 presidential election is fast approaching, and the next few months will be critical for voter registration, education, and mobilization. Campaigns and grassroots organizers are revamping their outreach strategies to make the most of this final stretch, and it’s also an important time for K-12 schools to acknowledge and embrace their role in preparing young people for electoral participation. As educators are forced to rethink their instructional approach in light of COVID-19 disruptions, new research from a recent CIRCLE youth survey underscores the power of high school teachers encouraging students to vote and teaching them how to register to vote. Our survey offers a deeper understanding of the extent to which young people, ages 18-29, benefited from these experiences in high school and describes the impact of voter education and encouragement on youth attitudes and civic behavior. [1]

Our top findings reveal that:

- Nearly two-thirds of respondents (64%) report having been encouraged to vote in high school, while half (50%) say they were taught how to register to vote

- Who received civic encouragement or instruction in high school varies by race: two out of every three White students (67%) remember having being encouraged to vote in high school compared with one in two Black students (54%)

- Youth who reported having been either encouraged to vote or taught how to register to vote in high school are more likely to vote and participate in other civic activities, more knowledgeable about voting processes, and more invested in and attentive to the 2020 election than other youth

- Students who had not received encouragement to vote from teachers in high school were more than twice as likely to agree with the statement “Voting is a waste of time” as those who had been encouraged: 26% vs. 12%

- Young people who learned about voting procedures in high school are more prepared for voting today: they were more likely than their peers to know if their states had online voter registration, and at least 10 percentage points more likely to respond that they had seen information on how to vote by mail, and to state that they would know where to go to find information on voting if their state’s election was shifted to all mail-in ballots

About the Survey: The first wave of the CIRCLE/Tisch College 2020 Youth Survey was fielded from May 20 to June 18, 2020. The survey covered adults between the ages of 18 and 29 who will be eligible to vote in the United Stated by the 2020 General Election. The sample was drawn from the Gallup Panel, a probability-based panel that is representative of the U.S. adult population, and from the Dynata Panel, a non-probability panel. A total of 2,232 eligible adults completed the survey, which includes oversamples of 18- to 21-year-olds (N=671), Asian American youth (N=306), Black youth (N=473), Latino youth (N=559) and young Republicans (N=373). Of the total completes, 1,019 were from the Gallup Panel and 1,238 were from the Dynata Panel. Unless stated otherwise, ‘youth’ refers to those ages 18- to 29-years old. The margin of error for the poll, taking into account the design effect from weighting, is +/- 4.1 percentage points. Margins of error for racial and ethnic subgroups range from +/-8.1 to 11.0 percentage points.

Access to Civic Instruction and Encouragement in High School Varies

Our survey indicates that half of young people in the U.S. have received instruction on how to register to vote (50%), and a majority have received encouragement to vote from teachers in high school (64%). While the survey offers limited insight into the quality or depth of these educational experiences, and does not imply causality, the data highlights a relationship between these experiences and outcomes that educators and allies across the country can build on to strengthen civics education in schools. Past CIRCLE research has found that young people who recall having received a better civics education are more likely to be civically engaged . These new results further illustrate the relationship between civic instruction and civic behavior.

Ensuring impact, however, begins with ensuring access. Our findings reveal inequities in who receives voter education and encouragement in high school, with disparities according to students’ race/ethnicity and region.

While almost two in three students overall (64%) report having been encouraged to vote in high school, this was true for just over half of Black students (54%). Additionally, 50% of 18- to 29-year-olds remember explicitly having received instruction in how to register to vote, and a slightly lower percentage of Black youth say they remember such instruction—though this difference is small. This data echoes past CIRCLE findings that White students and students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds were exposed to more promising practices in civics education than other students .

Lastly, by examining the responses of respondents of different ages (who would have been in school at different times) we tried to identify any trends in whether such voter instruction and/or encouragement has changed over time. While we found some evidence to suggest that colleges are doing better teaching and encouraging students to vote than they have in the past, we observed no clear aggregate changes over time nationally in whether voting is/is not taught or encouraged in high schools.

Voter Education and Encouragement in High School Associated With Stronger Civic Behavior and Attitudes

Our survey finds that there is a strong and consistent relationship between young people’s self-reported high school experiences with voter education and encouragement, and their interest/engagement in civic participation later in life.

While just over a quarter (26%) of survey respondents who did not remember being encouraged to vote in high school agreed with the phrase “Voting is a waste of time,” this number dropped by half (to 12%) among young people who had received encouragement to vote in high school. Similarly, one in four young people (25%) whose high school years lacked this form of civic encouragement agreed with the statement “I don’t know enough to vote;” this rate dropped ten percentage points (to 15%) among youth whose high school teachers had offered encouragement to vote.

Youth who remembered receiving voter instruction or encouragement in high school also reported higher rates of participation across a range of civic activities, some explicitly political and some not.

For example, youth who were encouraged or taught how to register to vote in high school were at least 10 percentage points more likely to have volunteered on or donated money to a political campaign. They were also at least 12 percentage points more likely to have served in a leadership role in a community organization, attended a march or demonstration, or advocated for policy change. According to self-reported voter turnout from our survey, in both the 2016 and 2018 elections young people who had received both encouragement and instruction on voting in high school voted at a rate 7 percentage points higher than youth who received neither.

Educators Can Play an Important Role in Expanding Equitable Voter Participation

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic adds a new layer of challenges and complexity to enabling and inspiring youth electoral participation this fall. But among all of the other educational priorities, helping youth navigate what they are seeing and hearing about civic life right now is crucial. Our survey suggests that youth who received instruction on registering to vote or encouragement to do so in high school are more invested in the 2020 election than youth who did not receive either, and that they will be better prepared to navigate changes to eligibility rules and election procedures in the months ahead.

Regardless of how long ago youth were in high school, those who received encouragement or instruction about voting from secondary school teachers are paying more attention to the 2020 election than their peers who did not have these experiences in school. That said, they’re not always more likely to believe that the election’s outcomes will significantly impact their communities. Students who had these experiences in high school are not only more attentive to what’s going on in the election; they’re more informed as well. And our analysis revealed that students who had been both encouraged to vote and taught how to register to vote in high school were the best prepared to navigate modern election procedures.

Survey respondents who had either been encouraged to vote or taught how to register in high school were 10+ percentage points more likely to have seen information about how to vote by mail than students who had neither experience, and this likelihood grew among young people who were both encouraged and taught to register to vote in high school.

The same was also true for young people’s self-reported ability to find information about casting a ballot if their state’s election shifts to all-mail: 76% of youth who had been taught about voter registration and encouraged to vote in high school said they’d know where to get such information, compared to just 49% of their peers who had had neither experience. Likewise, 60% of youth in our survey who had received both encouragement and instruction on voting in high school correctly identified whether or not their state offered online voter registration, compared to 42% of youth who had not been afforded either experience.

When young people were both encouraged to vote and taught how to register to vote in school, these experiences seem to have had a compounding effect. Students who were exposed to both types of ‘civic support’ were more likely to have tried to convince other young people to vote. About half (49%) of young people who had only reported being taught how to register to vote in high school had worked to convince their peers to register , and 54% of youth who had been encouraged to vote in high school had tried to register others. However, among youth who had been both taught and encouraged to vote, 59% reported they’ve worked to register peers.

This analysis demonstrates that high school teachers’ guidance about, and enthusiasm for, student voting is important insofar as it not only impacts young people’s knowledge about current voting processes; it also builds students’ sense of skill or confidence navigating election information and prepares them to stay abreast of future changes to election systems. That said, high quality implementation and instruction should be an important consideration. A more detailed account of young people’s experiences would go a long way towards understanding differences in the implementation and the effects of these strategies on various outcomes.

Making the Most of the Months Ahead

The data is clear: young people’s experiences being taught and encouraged to vote in high school matter, and young people and young voters have the potential to impact elections in many ways this fall

It’s also clear that, because of COVID-19, schooling this fall is not business as usual. As educators, administrators, and parents work collaboratively to shape what students’ educational experiences look like in the months ahead, they must include voting and elections as part of that conversation for the sake of youth engagement in 2020 and for years to come.

They may start by looking at their state’s policies and statutes and clarifying what opportunities their state offers for engaging students in learning about or participating in elections. Educators and others can turn also to the Teaching for Democracy Alliance (TFDA), a 17-member coalition coordinated by CIRCLE, for resources on how to embed civic learning within classrooms, schools, and districts. We recommend teachers and administrators adopt an approach that is both holistic— incorporating media literacy, classroom discussion, and Action Civics/experiential learning alongside voter registration and education —and explicit, providing young people direct access to accurate and detailed information on registration and voting procedures. We cannot take for granted that young people will access this information on their own just because it is available online. Past CIRCLE studies have revealed that young people often prefer utilizing these online tools with the guidance of trusted adults, such as teachers, so that they can ask questions and ensure they’re filling out forms correctly.

In a year when teachers and administrators are facing extraordinary challenges, the challenge of helping youth be ready to vote remains one of the most crucial. It holds the potential to impact young people’s participation in the November elections and in the civic life of their communities for years to come.

[1] This analysis is centered around two questions from the CIRCLE/Tisch College 2020 Youth Survey: “Did/have teachers in high school encouraged you to vote?” and “Did you learn about where and how to register to vote in high school?” We report on responses to these questions, and we use these questions as a filter for analyzing how participants answered other survey questions.

Authors: Sarah Andes, Abby Kiesa, Rey Junco, Alberto Medina

Voter Education: 6 Keys to Understanding the Nuances of Voting

Voting is a cornerstone of a civically engaged life, offering every person a voice in the collective direction of their community and nation. In an era where information – and misinformation – is at our fingertips, it’s both a privilege and a responsibility to be informed, especially when it comes to our democratic processes.

Casting an informed vote isn’t just about choosing a preferred candidate; it’s about understanding how that choice will affect our daily lives for the years to come. Voter education is the avenue that leads to such an informed decision. It is the responsibility of both the individual and the larger societal systems to ensure voters understand the candidates and ballot. Here are some tips on how to become more informed and some resources to help you do so.

The Power of Local Elections

While presidential elections often command a lot of attention, it’s local elections that have the most immediate and tangible impact on our daily lives. In most major cities, fewer than 15% of voters turn out to vote in their mayoral election. And because there are fewer voters in local elections , your vote carries tremendous power.

Elected officials at the local level, from school board members to mayors and city council members, shape policies on everything from public transportation to local taxes to educational reforms and more.

Given the smaller voter pool in local elections, each ballot cast carries more significant weight, making it an invaluable opportunity for individuals to influence their immediate surroundings and advocate for the issues that matter most to them.

Where to Find Resources

To be an informed voter, a little homework is in order. Start by finding out if your state offers an app for voting. Apps can offer access to the upcoming ballot, tell you where to vote, help you update your registration, vote by absentee ballot and more.

To learn more about who and what is on the ballot, check local newspapers and community websites, which frequently offer insightful profiles of candidates and provide breakdowns of local issues. Nonpartisan websites such as Vote411 offer a comprehensive look at your ballot, from the top offices to the local issues, and provide insights on measures and candidate stances. This resource was launched by the League of Women Voters Education Fund and tailors election information to your specific location, ensuring you have all the details you need to cast your vote confidently. Similarly, Ballotpedia serves as an objective online encyclopedia of neutral, detailed information about elections at all levels.

Interpreting the Ballot

Ballots can sometimes present a challenge to voters, especially when measures are described in dense legal language. To truly grasp the meaning and implications of these measures, voters should turn to nonpartisan resources like the websites listed above or attend local community forums that offer clear and concise explanations.

When researching candidates, it’s beneficial to peruse candidates’ official websites and social media pages. These platforms often provide a candid view of the candidate’s priorities and standpoints on various issues. But what if a candidate doesn’t necessarily have a robust website that answers your questions?

Engage with Local Officials

The beauty of local governance lies in its accessibility. Local officials, unlike their national counterparts, tend to be more reachable and responsive to their constituents. If there’s ever uncertainty about a candidate’s stance on an issue, or if there’s a desire to voice a concern, you shouldn’t hesitate to send an email or make a phone call.

This kind of direct engagement not only provides valuable insights but also informs officials about the issues that matter to their community. Additionally, attending town hall meetings or public forums hosted in local community centers, schools or libraries offers a direct channel to engage with and learn from candidates.

Make Sure You’re Registered to Vote

It may sound like an unnecessary step if you’ve registered to vote in the past, but it’s not uncommon for voter registrations to be purged. At least 17 million voters were purged nationwide between 2016 and 2018.

Purging voter rolls is a necessary and important process. Registered voters can be purged for a number of reasons, including death, moving and committing a felony among others. The reason can vary by state , but once your record is purged, you become ineligible to cast your ballot. Before the next election, check to see if your registration is active.

Now It’s Time to Vote

A thriving democracy relies on the active and informed participation of its citizens. By dedicating time to understanding the local landscape—both the candidates and the issues—you become an integral part of shaping your community’s future direction.

In the realm of local elections, your vote isn’t just a voice; it’s a call to action. As election day approaches, be prepared to wield that power, knowing fully the impact and influence of your choice.

Share this post

We are champions of civic engagement with a mission to inspire, equip and mobilize people to take action that changes the world.

- Civic Century

- Civic Circle

- Civic Culture

- Civic Engagement

Skip to content. | Skip to navigation

- Subscribe to the ACE Newsletter

- English

- Español

- العربية

- Français

- Swahili

Personal tools

- Practitioners' Network

ELECTORAL FRAMEWORK

Electoral participation, electoral management, electoral integrity, electoral operations.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Voter Education. Voter education means providing citizens of a democracy with basic information about participating in elections. Voter education is often provided by the state itself, often through a national electoral commission, so it is therefore important that it is politically non-partisan. Government departments that focus on voter ...

Voter education is the power source that makes a representative democracy effective. Learn what voter education means and why it matters so much for our democracy. ... In such an environment, the importance of voter education cannot be overstated. When we understand how voter education empowers citizens and strengthens democracy — and apply ...

Voter education sensitize the electorate on the importance of participating in elections. Voter education provides the background attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge among citizens that stimulate and consolidate democracy. During an election, this education will ensure effective organization and activism by citizens in support of parties and/or ...

In Episode 3 of our video series Talking Elections, we wanted to take a look at voter education which is an important topic that doesn't get enough notice in the elections community.There is a lot of information that voters need to know to vote and have their votes counted accurately, from registration deadlines and the documentation they might need to register to the location of polling ...

Voter education is the act of providing voters with basic information about the voting process and elections. Voter education materials can be delivered through events, websites, mailings, and advertising. Some topics covered by voter education materials include how to register to vote, viewing a sample ballot, or providing information about ...

And the early signs aren't promising: A recent poll from Gallup indicates that just 26 percent of 18-to-29-year-olds say they intend to vote in the November midterms, compared to 82 percent of ...

Voter education can make a major contribution to electoral integrity. Voter education programs disseminate balanced and objective information on what citizens need to know in order to exercise their right to vote. They provide information on voters' rights and obligations in the electoral process and explain the importance of voting.

The final results of the 2022 midterm election in the United States are in. Journalists tell us that a key issue for voters was preservation of democracy. A recent NPR/PBS NewsHour /Marist poll ...

the importance of voting and the impact of the youth vote, as well as how to be an informed voter, and then helped students register to ... nonpartisan voter education events, including Voter Registration Day, Early Voting Day, an Accessibility and Voting panel with the Miami-Dade County Supervisor of Elections, and a

In this article, we assess whether voters who live in states where state election officials (EOs) invested in voter education have higher levels of confidence in vote counting. We argue state investment in voter education strengthens voter confidence by improving voter experiences and creating a culture of voter education, both of which facilitate transparency in elections. We measure state ...

The issue is ripe for policy change and offers yet another reason for voters and presidential candidates to pay attention to education. Support for early childhood is very high in polls, with ...

Donate and support our work. We host hundreds of events and programs every year to educate voters about candidates in thousands of federal, state and local races, as well as distribute millions of educational materials about state and local elections.

The Importance of the Educated Voter. The act of voting is the most important contribution every single eligible voter can make to insure the health of our democracy. Yet year after year, a discouraging number of eligible voters choose not to pull the levers of power. In advance of the midterm elections, Facing History CEO Roger Brooks stops to ...

The 2018 midterm elections saw an extraordinary increase in youth participation, but the youngest eligible voters —those aged 18 and 19— still voted at significantly lower rates. That age disparity in youth turnout has long been intractable, but it is far from inevitable. At the national, state, and local levels, there are steps we can take ...

Basic Voter Education typically addresses voters' motivation and preparedness to participate fully in elections. It pertains to relatively more complex types of information about voting and the electoral process and is concerned with concepts such as the link between basic human rights and voting rights; the role, responsibilities and rights of ...

1. A Voice in Decision-Making: Voting provides us with the opportunity to express our opinions and choose representatives who will make decisions on our behalf. By casting a vote, you have a chance to select leaders who align with your values and who will work towards addressing the issues that matter most to you, your family, and your community.

Politics essentially run our country and as eligible voters, it's important that people take advantage of their right to vote and make the most out of it through educating ourselves and those around us. Kimberly Argueta is a political science freshman who can be reached at [email protected]. This is called voter education, and it is ...

In fact, where we see the importance and necessity of public voter education campaigns demonstrated so clearly is whenever the state of Texas has made major changes to voting laws that require proactive, early efforts to educate the public on a mass scale so Texas voters know how they may be impacted come Election Day.

Civic learning that reaches all youth, includes media literacy, and helps foster a democratic school climate is key to growing voters. The following is adapted, with minor changes, from the CIRCLE Growing Voters report and framework published in 2022. We include recommendations for teachers, administrators, and others in the K-12 school ...

The 2020 presidential election is fast approaching, and the next few months will be critical for voter registration, education, and mobilization. Campaigns and grassroots organizers are revamping their outreach strategies to make the most of this final stretch, and it's also an important time for K-12 schools to acknowledge and embrace their role in preparing young people for electoral ...

Voter education is the avenue that leads to such an informed decision. It is the responsibility of both the individual and the larger societal systems to ensure voters understand the candidates and ballot. ... Purging voter rolls is a necessary and important process. Registered voters can be purged for a number of reasons, including death ...

The economy, education and healthcare are top of mind of West Virginia Republican voters, with around 63% calling the quality of local public education "fair" or "poor," according to new polling data.

Balancing voter education programmes against these other interventions is important in ensuring that budgets are not inflated. Costs of voter education programmes can and should be based on cost-per-voter estimates. It may be argued, and is on occasion argued, that elections, however expensive, are cheaper than war or endemic community conflict.

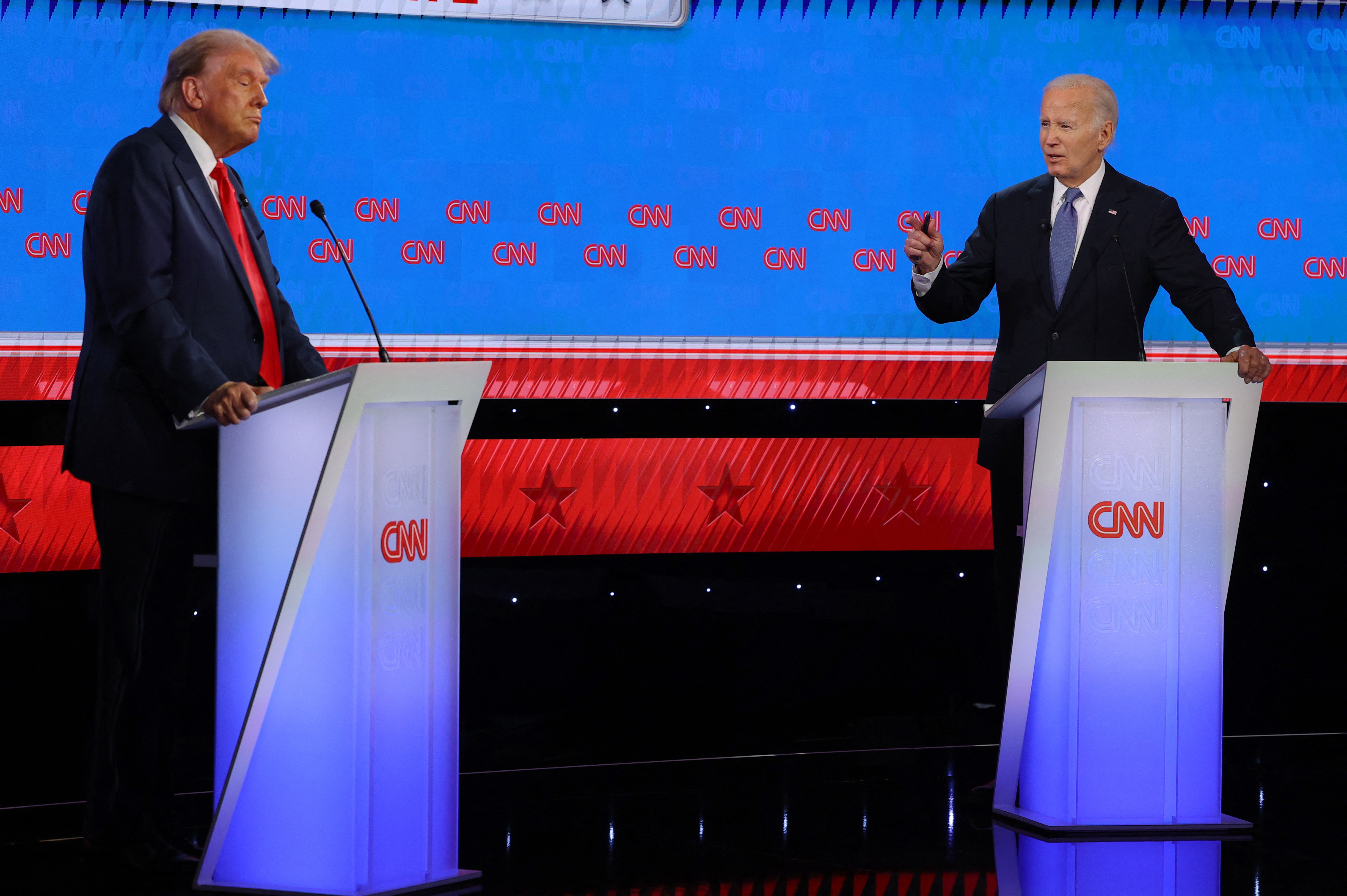

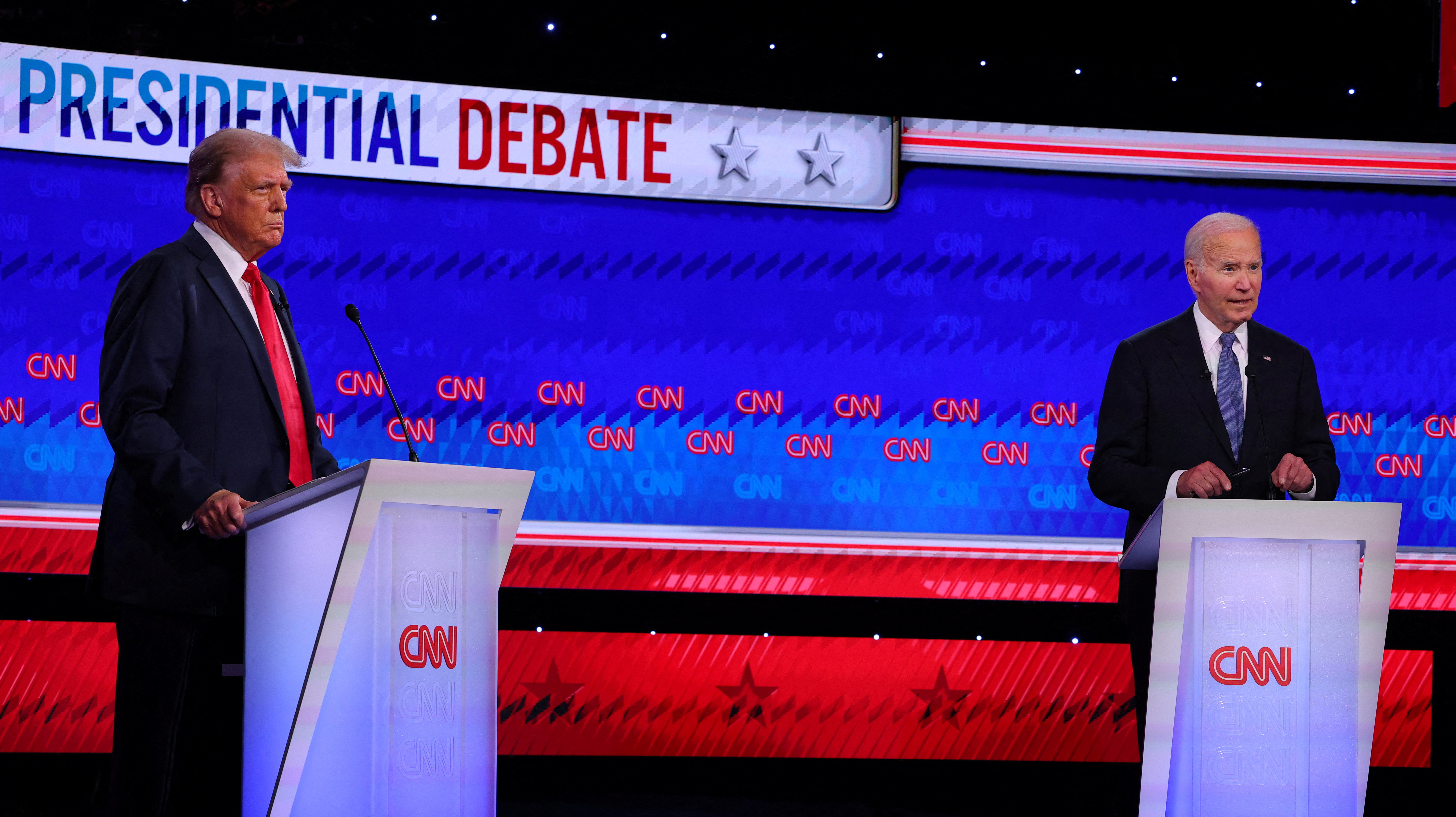

U.S. President Joe Biden and his Republican rival Donald Trump traded attacks on abortion and their handling of the economy in their debate on Thursday night, giving voters a rare side-by-side ...

In an effort to encourage more postsecondary students to register and vote, Education for All (EFA), a group of over 250 college presidents, mostly from community colleges, has created the Student Voting Brief, a strategy guide for institutional leadership, CEOs, and partners to help instill civic participation and successful campus voting initiatives.