Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Chapter 6: Progressivism

Dr. Della Perez

This chapter will provide a comprehensive overview of Progressivism. This philosophy of education is rooted in the philosophy of pragmatism. Unlike Perennialism, which emphasizes a universal truth, progressivism favors “human experience as the basis for knowledge rather than authority” (Johnson et. al., 2011, p. 114). By focusing on human experience as the basis for knowledge, this philosophy of education shifts the focus of educational theory from school to student.

In order to understand the implications of this shift, an overview of the key characteristics of Progressivism will be provided in section one of this chapter. Information related to the curriculum, instructional methods, the role of the teacher, and the role of the learner will be presented in section two and three. Finally, key educators within progressivism and their contributions are presented in section four.

Characteristics of Progressivim

6.1 Essential Questions

By the end of this section, the following Essential Questions will be answered:

- In which school of thought is Perennialism rooted?

- What is the educational focus of Perennialism?

- What do Perrenialists believe are the primary goals of schooling?

Progressivism is a very student-centered philosophy of education. Rooted in pragmatism, the educational focus of progressivism is on engaging students in real-world problem- solving activities in a democratic and cooperative learning environment (Webb et. al., 2010). In order to solve these problems, students apply the scientific method. This ensures that they are actively engaged in the learning process as well as taking a practical approach to finding answers to real-world problems.

Progressivism was established in the mid-1920s and continued to be one of the most influential philosophies of education through the mid-1950s. One of the primary reasons for this is that a main tenet of progressivism is for the school to improve society. This was sup posed to be achieved by engaging students in tasks related to real-world problem-solving. As a result, progressivism was deemed to be a working model of democracy (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.2 A Closer Look

Please read the following article for more information on progressivism: Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find. As you read the article, think about the following Questions to Consider:

- How does the author define progressive education?

- What does the author say progressive education is not?

- What elements of progressivism make sense, according to the author?

Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find

6.3 Essential Questions

- How is a progressivist curriculum best described?

- What subjects are included in a progressivist curriculum?

- Do you think the focus of this curriculum is beneficial for students? Why or why not?

As previously stated, progressivism focuses on real-world problem-solving activities. Consequently, the progressivist curriculum is focused on providing students with real-world experiences that are meaningful and relevant to them rather than rigid subject-matter content.

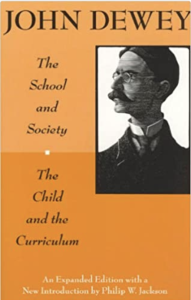

Dewey (1963), who is often referred to as the “father of progressive education,” believed that all aspects of study (i.e., arithmetic, history, geography, etc.) need to be linked to materials based on students every- day life-experiences.

However, Dewey (1938) cautioned that not all experiences are equal:

The belief that all genuine education comes about through experience does not mean that all experiences are genuinely or equally educative. Experience and education cannot be directly equated to each other. For some experiences are mis-educative. Any experience is mis-education that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth or further experience (p. 25).

An example of miseducation would be that of a bank robber. He or she many learn from the experience of robbing a bank, but this experience can not be equated with that of a student learning to apply a history concept to his or her real-world experiences.

Features of a Progressive Curriculum

There are several key features that distinguish a progressive curriculum. According to Lerner (1962), some of the key features of a progressive curriculum include:

- A focus on the student

- A focus on peers

- An emphasis on growth

- Action centered

- Process and change centered

- Equality centered

- Community centered

To successfully apply these features, a progressive curriculum would feature an open classroom environment. In this type of environment, students would “spend considerable time in direct contact with the community or cultural surroundings beyond the confines of the classroom or school” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 74). For example, if students in Kansas were studying Brown v. Board of Education in their history class, they might visit the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka. By visiting the National Historic Site, students are no longer just studying something from the past, they are learning about history in a way that is meaningful and relevant to them today, which is essential in a progressive curriculum.

- In what ways have you experienced elements of a progressivist curriculum as a student?

- How might you implement a progressivist curriculum as a future teacher?

- What challenges do you see in implementing a progressivist curriculum and how might you overcome them?

Instruction in the Classroom

6.4 Essential Questions

- What are the main methods of instruction in a progressivist classroom?

- What is the teachers role in the classroom?

- What is the students role in the classroom?

- What strategies do students use in a progressivist classrooms?

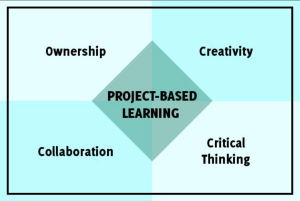

Within a progressivist classroom, key instructional methods include: group work and the project method. Group work promotes the experienced-centered focus of the progressive philosophy. By giving students opportunities to work together, they not only learn critical skills related to cooperation, they are also able to engage in and develop projects that are meaningful and have relevance to their everyday lives.

Promoting the use of project work, centered around the scientific method, also helps students engage in critical thinking, problem solving, and deci- sion making (Webb et. al., 2010). More importantly, the application of the scientific method allows progressivists to verify experi ence through investigation. Unlike Perennialists and essentialists, who view the scientific method as a means of verifying the truth (Webb et. al., 2010).

Teachers Role

Progressivists view teachers as a facilitator in the classroom. As the facilitator, the teacher directs the students learning, but the students voice is just as important as that of the teacher. For this reason, progressive education is often equated with student-centered instruction.

To support students in finding their own voice, the teacher takes on the role of a guide. Since the student has such an important role in the learning, the teacher needs to guide the students in “learning how to learn” (Labaree, 2005, p. 277). In other words, they need to help students construct the skills they need to understand and process the content.

In order to do this successfully, the teacher needs to act as a collaborative partner. As a collaborative partner, the teachers works with the student to make group decisions about what will be learned, keeping in mind the ultimate out- comes that need to be obtained. The primary aim as a collaborative partner, according to progressivists, is to help students “acquire the values of the democratic system” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 75).

Some of the key instructional methods used by progressivist teachers include:

- Promoting discovery and self-directly learning.

- Integrating socially relevant themes.

- Promoting values of community, cooperation, tolerance, justice, and democratic equality.

- Encouraging the use of group activities.

- Promoting the application of projects to enhance learning.

- Engaging students in critical thinking.

- Challenging students to work on their problem solving skills.

- Developing decision making techniques.

- Utilizing cooperative learning strategies. (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.5 An Example in Practice

Watch the following video and see how many of the bulleted instructional methods you can identify! In addition, while watching the video, think about the following questions:

- Do you think you have the skills to be a constructivist teacher? Why or why not?

- What qualities do you have that would make you good at applying a progressivist approach in the classroom? What would you need to improve upon?

Based on the instructional methods demonstrated in the video, it is clear to see that progressivist teachers, as facilitators of students learning, are encouraged to help their stu dents construct their own understanding by taking an active role in the learning process. Therefore, one of the most com- mon labels used to define this entire approach to education to- day is: constructivism .

Students Role

Students in a progressivist classroom are empowered to take a more active role in the learning process. In fact, they are encourage to actively construct their knowledge and understanding by:

- Interacting with their environment.

- Setting objectives for their own learning.

- Working together to solve problems.

- Learning by doing.

- Engaging in cooperative problem solving.

- Establishing classroom rules.

- Evaluating ideas.

- Testing ideas.

The examples provided above clearly demonstrate that in the progressive classroom, the students role is that of an active learner.

6.6 An Example in Practice

Mrs. Espenoza is an 6th grade teacher at Franklin Elementary. She has 24 students in her class. Half of her students are from diverse cultural- backgrounds and are receiving free and reduced lunch. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, Mrs. Espenoza does not use traditional textbooks in her classroom. Instead, she uses more real-world resources and technology that goes beyond the four walls of the classroom. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, she seeks out members of the community to be guest presenters in her classroom as she believes this provides her students with an way to interact with/learn about their community. Mrs. Espenoza also believes it is important for students to construct their own learning, so she emphasizes: cooperative problem solving, project-based learning, and critical thinking.

6.7 A Closer Look

For more information about progressivism, please watch the following videos. As you watch the videos, please use the “Questions to Consider” as a way to reflect on and monitor your own learnings.

• What additional insights did you gain about the progressivist philosophy?

• Can you relate elements of this philosophy to your own educational experiences? If so, how? If not, can you think of an example?

Key Educators

6.8 Essential Questions

- Who were the key educators of Progressivism?

- What impact did each of the key educators of Progressivism have on this philosophy of education?

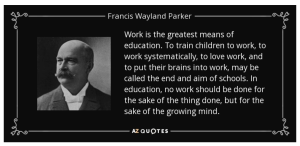

The father of progressive education is considered to be Francis W. Parker. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts, and later became the head of the Cook County Normal School in Chicago (Webb et. al., 2010). John Dewey is the American educator most commonly associated with progressivism. William H. Kilpatrick also played an important role in advancing progressivism. Each of these key educators, and their contributions, will be further explored in this section.

Francis W. Parker (1837 – 1902)

Francis W. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts (Webb, 2010). Between 1875 – 1879, Parker developed the Quincy plan and implemented an experimental program based on “meaningful learning and active understanding of concepts” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 1). When test results showed that students in Quincy schools outperformed the rest of the school children in Massachusetts, the progressive movement began.

Based on the popularity of his approach, Parker founded the Parker School in 1901. The Parker School

“promoted a more holistic and social approach, following Francis W. Parker’s beliefs that education should include the complete development of an individual (mental, physical, and moral) and that education could develop students into active, democratic citizens and lifelong learners” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 2).

Parker’s student-centered approach was a dramatic change from the prescribed curricula that focused on rote memorization and rigid student disciple. However, the success of the Parker School could not be disregarded. Alumni of the school were applying what they learned to improve their community and promote a more democratic society.

John Dewey (1859 – 1952)

John Dewey’s approach to progressivism is best articulated in his book: The School and Society

(1915). In this book, he argued that America needed new educational systems based on “the larger whole of social life” (Dewey, 1915, p. 66). In order to achieve this, Dewey proposed actively engaging students in inquiry-based learning and experimentation to promote active learning and growth among students.

As a result of his work, Dewey set the foundation for approaching teaching and learning from a student-driven perspective. Meaningful activities and projects that actively engaging the students’ interests and backgrounds as the “means” to learning were key (Tremmel, 2010, p. 126). In this way, the students could more fully develop as learning would be more meaningful to them.

6.9 A Closer Look

For more information about Dewey and his views on education, please read the following article titled: My Pedagogic Creed. This article is considered Dewey’s famous declaration concerning education as presented in five key articles that summarize his beliefs.

My Pedagogic Creed

William H. Kilpatrick (1871-1965)

Kilpatrick is best known for advancing progressive education as a result of his focus on experience-centered curriculum. Kilpatrick summarized his approach in a 1918 essay titled “The Project Method.” In this essay, Kilpatrick (1918) advocated for an educational approach that involves

“whole-hearted, purposeful activity proceeding in a social environment” (p. 320).

As identified within The Project Method, Kilpatrick (1918) emphasized the importance of looking at students’ interests as the basis for identifying curriculum and developing pedagogy. This student-centered approach was very significant at the time, as it moved away from the traditional approach of a more mandated curriculum and prescribed pedagogy.

Although many aspects of his student-centered approach were highly regarded, Kilpatrick was also criticized given the diminished importance of teachers in his approach in favor of the students interests and his “extreme ideas about student- centered action” (Tremmel, 2010, p. 131). Even Dewey felt that Kilpatrick did not place enough emphasis on the importance of the teacher and his or her collaborative role within the classroom.

Reflect on your learnings about Progressivism! Create a T-chart and bullet the pros and cons of Progressivism. Based on your T-chart, do you think you could successfully apply this philosophy in your future classroom? Why or why not?

Chapter 6: Progressivism Copyright © 2023 by Dr. Della Perez. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

progressive education

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- StateUniversity.com - Progressive Education

progressive education , movement that took form in Europe and the United States during the late 19th century as a reaction to the alleged narrowness and formalism of traditional education . One of its main objectives was to educate the “whole child”—that is, to attend to physical and emotional, as well as intellectual , growth. The school was conceived of as a laboratory in which the child was to take an active part—learning through doing. The theory was that a child learns best by actually performing tasks associated with learning. Creative and manual arts gained importance in the curriculum, and children were encouraged toward experimentation and independent thinking. The classroom, in the view of Progressivism’s most influential theorist, the American philosopher John Dewey , was to be a democracy in microcosm.

(Read Arne Duncan’s Britannica essay on “Education: The Great Equalizer.”)

The sources of the progressive education movement lay partly in European pedagogical reforms from the 17th through the 19th century, ultimately stemming partly from Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s É mile (1762), a treatise on education, in the form of a novel, that has been called the charter of childhood. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Rousseau’s theories were given practical application in a number of experimental schools. In Germany , Johann Bernhard Basedow established the Philanthropinum at Dessau (1774), and Friedrich Froebel founded the first kindergarten at Keilhau (1837). In Switzerland , Johann Pestalozzi dedicated himself, in a succession of schools, to the education of poor and orphaned children. Horace Mann and his associates worked to further the cause of universal, nonsectarian education in the United States.

Throughout the late 19th century, a proliferation of experimental schools in England extended from Cecil Reddie ’s Abbotsholme (1889) to A.S. Neill’s Summerhill, founded in 1921. On the European continent some pioneers of progressive educational methods were Maria Montessori in Italy; Ovide Decroly in Belgium; Adolphe Ferrière in Geneva; and Elizabeth Rotten in Germany. The progressive educational ideas and practices developed in the United States, especially by John Dewey, were joined with the European tradition after 1900. In 1896 Dewey founded the Laboratory Schools at the University of Chicago to test the validity of his pedagogical theories.

From its earliest days progressive education elicited sharp and sustained opposition from a variety of critics. Humanists and idealists criticized its naturalistic orientation, its Rousseauean emphasis on interesting and freeing the child, and its cavalier treatment of the study of classic literature and classical languages.

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era

- > Volume 16 Issue 4

- > PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY: THE ENDURING...

Article contents

Progressive education in the 21st century: the enduring influence of john dewey.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 November 2017

This essay examines three schools in New York City—the City and Country School founded in 1914—and two founded in 1974 and 1984—Central Park East Elementary School 1 and Central Park East Secondary School—with respect to how they reflected Deweyan pedagogic practices and Dewey's belief in democratic education. 1 It analyzes whether such pedagogic practices can be maintained over time. City and Country, founded by Caroline Pratt, reflected many of Dewey's ideas and remains true to its founder's vision today. CPE 1 founded by Deborah Meier with five teachers reflected the progressive ideas of its founder, many of which were consistent with Deweyan philosophy. It remains progressive although there have been recent attempts to make it more traditional. CPESS, founded by Deborah Meier, reflected both Deweyan philosophy and the ideas of Theodore Sizer. After Meier left in the 1990s, the school became less progressive and eventually was closed and then reopened as a traditional high school. These histories indicate that Dewey's work on education was at the core of all of these schools’ philosophies and practices. Although there have been uneven successes in keeping Dewey's progressive practices alive, they demonstrate that Dewey's work is relevant and is being practiced today.

Access options

1 This article is adapted from Semel , Susan F. , Sadovnik , Alan R. , and Coughlan , Ryan W. , Schools of Tomorrow, Schools of Today: Progressive Education in the 21st Century ( 2nd ed. ). ( New York : Peter Lang , 2016 ) CrossRef Google Scholar , chs. 1, 2, 8, 9, 10.

2 See Semel, Sadovnik, and Coughlan, Schools of Tomorrow , for a detailed description of these schools, as well as six other schools and a detailed analysis of the history of progressive education based on them.

3 Dewey , John “ My Pedagogic Creed ” in Dworkin , Martin S. , ed., Dewey on Education ( New York : Teachers College Press , 1959 ), 19 – 32 Google Scholar PubMed (originally published 1897); “The School and Society” in Dworkin, Dewey on Education , 33–90 (originally published 1899). “The Child and the Curriculum” in Dworkin, Dewey on Education , 91–111 (originally published 1902); and Dewey, “Democracy and Education” in Dworkin, Dewey on Education , 45.

4 Dworkin, Dewey on Education, 22.

5 Ibid ., 93.

6 Ibid ., 41.

7 Ibid ., 40.

8 Ibid ., 81–99.

9 Ibid ., 20.

10 Ibid ., 21–22.

11 Robertson , Emily , “ Is Dewey's Educational Vision Still Viable ,” Review of Research in Education 18 ( 1992 ): 341 Google Scholar . See Semel and Sadovnik, Schools of Tomorrow , for a detailed discussion of this “progressive paradox.”

12 John , and Dewey , Evelyn , Schools of To-Morrow ( New York : E .P. Dutton , 1915 ) Google Scholar .

13 For a complete discussion of Caroline Pratt's early years, see Pat Carlton, Caroline Pratt: A Biography (Unpublished PhD diss., Columbia University Teachers College, 1986).

14 See Antler , Joyce , Lucy Sprague Mitchell: The Making of a Modern Woman ( New Haven, CT : Yale University Press , 1987 ), 237 Google Scholar ; Carlton, Caroline Pratt , 144, for more detailed descriptions.

15 Pratt , Caroline , I Learn From Children ( New York : Simon and Schuster , 1948 ), 8 Google Scholar PubMed .

16 Ibid ., 9.

17 Jean W. Murray, “Philosophy and Practice at City and Country”, City and Country (Unpublished materials prepared for student teachers, c. 1950), n.p.

18 See Semel , Susan , “ Female Founders and the Progressive Paradox ” in James , Michael . Ed., Social Reconstruction Through Education: The Philosophy, History, and Curricula of a Radical Ideal ( Norwood, NJ : Ablex , 1995 ), 89 – 108 Google Scholar .

19 Pratt , Caroline , I Learn from Children , City and Country Centennial Edition ( New York : City and Country School , 2014 ) Google Scholar PubMed .

20 Kate Turley, I Learn from Children , City and Country Centennial Edition, 267.

21 Personal communications with Vivian Wallace and Lucy Matos.

22 Weber returned from her studies in England in the mid-1960s. She started the first Open Corridor at P.S. 123 in Harlem in 1967. An account can be found in the fall 1977 edition of the “Workshop Center for Open Education's Notes.” This is a ten-year retrospective of the Open Corridor program. In another source, Weber wrote, “I was full of wonder at what I had seen of children's learning, for example in English infant schools, where there was a rich surround of environment and easy relationships that joined them in what was focusing their attention and responded to their attention with recognition of the importance of this focus for them.” William Ayers, To Become a Teacher: Making a Difference in Children's Lives. (New York: Teachers College Press, 1995), 127.

23 Dewey , John , School and Society ( Chicago : University of Chicago Press , 1915 ) Google Scholar ; and Dewey , John , The Child and the Curriculum ( Chicago : University of Chicago Press , 1902 ) Google Scholar .

24 Kate Taylor, “East Harlem School's Utopian Spirit Devolves Into War,” New York Times , May 19, 2016, A20.

25 See Andrew R. Ratner and Ali Nagle, “A Look into KIPP: Culture Through the Prism of Progressive Schools” in Semel, Sadovnik, and Coughlan, Schools of Tomorrow , ch. 11; Delpit , Lisa , Other People's Children: Cultural Conflict in the Classroom ( New York : New Press , 1995 ) Google Scholar .

26 Kate Taylor, “East Harlem Principal Out After Yearlong Fight,” New York Times , May 15, 2017, A25.

27 Sizer , Ted , Horace's Compromise: The Dilemma of the American High School ( Boston : Houghton Mifflin , 1984 ) Google Scholar .

28 Semel , Susan F. and Sadovnik. , Alan R. “ The Contemporary Small School Movement: Lessons from the History of Progressive Education ,” Teachers College Record 110 : 9 ( 2008 ): 1774 -–71 Google Scholar . See Semel, Sadovnik, and Coughlan, Schools of Tomorrow , ch. 3, for a detailed discussion of the Dalton Plan and the history of the school.

29 Hall , Richard , Organizations: Structure and Process ( 2nd ed. ) ( Englewood Cliffs, NJ : Prentice Hall , 1977 ) Google Scholar .

30 New York City public school Chancellor Dennis M. Walcott promised that he will look for a site to house the middle school so that it could open in time for the 2014–2015 academic year.

31 Attewell , Paul and Gerstein , Dean R. , “ Government Policy and Local Practice ,” American Sociological Review 44 ( 1979 ): 311 –27 CrossRef Google Scholar .

32 Attewell and Gerstein, “Government Policy and Local Practice.”

33 See Mary Anne Raywid, “A School That Really Works: Urban Academy” in Semel, Sandovnik, and Coughlan, Schools of Tomorrow , 289–312.

34 See Semel, Sadovnik, and Coughlan, Schools of Tomorrow , for a detailed discussion of democratic education for all and pp. 53–98 for a detailed discussion of the Dalton School.

35 See “American Promise,” PBS Documentary, 2013, for an examination of the lives of two African American male students at Dalton.

36 See Anyon , Jean , Ghetto Schooling: The Political Economy of Urban Educational Reform ( New York : Teachers College Press , 1997 ) Google Scholar ; Bowles , Samuel and Gintis , Herbert , Schooling in Capitalist America: Liberal Educational Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life ( New York : Basic Books , 1977 ) Google Scholar ; Cookson , Peter W. Jr. , Class Rules: Exposing Inequality in American High Schools ( New York : Teachers College Press , 2013 ) Google Scholar for an examination of how education in the United States reproduces social class inequality.

37 See, for example, Paul L. Tractenberg, Gary Orfield, and Greg Flaxman, “New Jersey's Apartheid and Intensely Segregated Urban Schools: Powerful Evidence of an Inefficient and Unconstitutional State Education System,” Rutgers University, Institute on Education Law and Policy, for an analysis of racial segregation in Essex County, New Jersey.

38 Frankenberg , Erica and Orfield , Gary , Lessons in Integration: Realizing the Promise of Racial Diversity in American Schools ( Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press , 2007 ) Google Scholar .

39 Meier , Deborah , The Power of Their Ideas ( Boston : Beacon , 1995 ) Google Scholar .

40 Sadovnik , Alan R. , “ Schools, Social Class and Youth: A Bernsteinian Analysis ” in Weis , Lois , The Way Class Works ( New York : Routledge , 2008 ), 315 –29 Google Scholar .

41 Dewey , John , Experience and Education ( Chicago : Simon and Schuster , 1938 ) Google Scholar .

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 16, Issue 4

- Alan R. Sadovnik (a1) , Susan F. Semel (a2) , Ryan W. Coughlan (a3) , Bruce Kanze (a2) and Alia R. Tyner-Mullings (a3)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537781417000378

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

John Dewey: Portrait of a Progressive Thinker

His ideas altered the education of children worldwide .

John Dewey in 1950.

—Bettmann / Getty Images

“I believe that education is the fundamental method of social progress and reform.” —John Dewey

“He was loved, honored, vilified, and mocked as perhaps no other major philosopher in American history.” —Larry Hickman

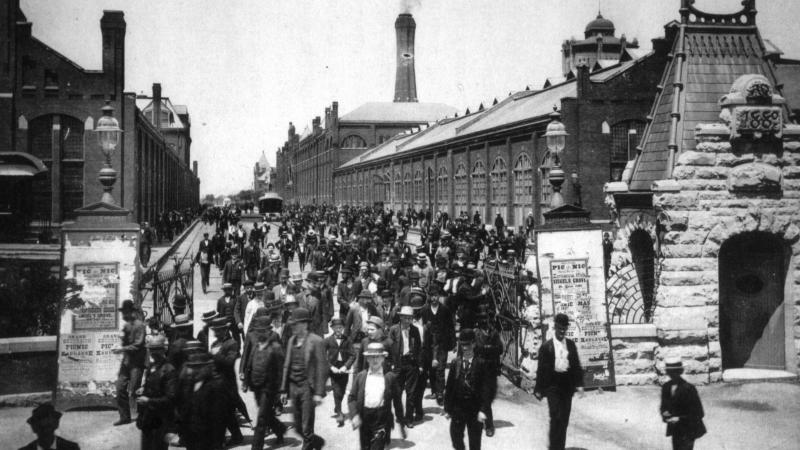

In the 1894 Pullman strike, workers fought against having their wages cut. Dewey saw the turmoil as symbolic of a rapidly changing America in need of school reform.

—Wikimedia Commons

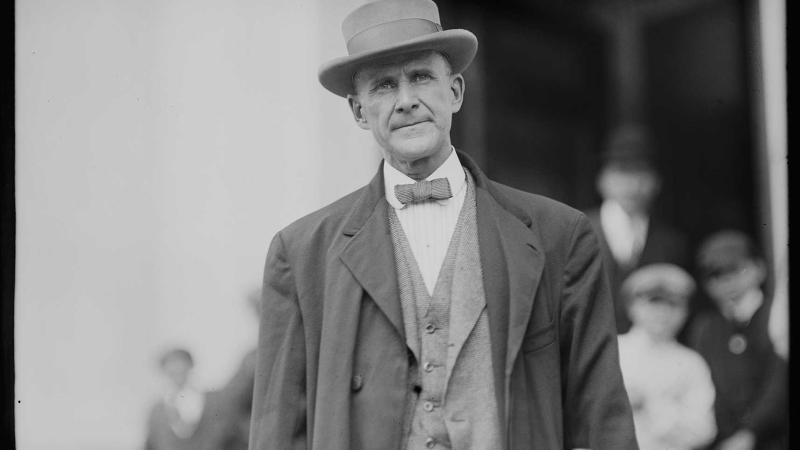

Dewey praised the Pullman strikers’ leader Eugene V. Debs—head of the American Railway Union—and the strikers’ “fanatic sincerity and earnestness.”

—Harris & Ewing photograph, 1912 / Library of Congress

In July 1894, a train carrying a young philosopher from Ann Arbor, Michigan, pulled into Chicago Union Station. Its arrival was delayed by striking workers of the American Railway Union, who were made furious by the Pullman Company’s decision to cut their wages. The strike ended two weeks later, took the lives of thirty people, and symbolized a rapidly changing America dominated by corporations that set laborers against owners.

The philosopher had entered a city whose population was exploding with immigrants, many of whom were illiterate; a city of half-built skyscrapers and noisome meatpacking plants; a city with a new university funded by John D. Rockefeller, the University of Chicago, whose Gothic buildings and eminent faculty would rival those of Harvard and Yale. John Dewey had arrived to chair the philosophy and pedagogy department. Once in the city, he visited the strikers, applauded their “fanatic sincerity and earnestness,” praised their leader Eugene Debs, and condemned President Cleveland’s suppression of the strike. Worried about working for a university dedicated to laissez-faire capitalism, Dewey found himself becoming more of a populist, more of a socialist, more sympathetic to the settlement house pioneered by Jane Addams, and more skeptical of his childhood Christianity. He would conclude that a changing America needed different schools.

In 1899, Dewey published the pamphlet that made him famous, The School and Society , and promulgated many key precepts of later education reforms. Dewey insisted that the old model of schooling—students sitting in rows, memorizing and reciting—was antiquated. Students should be active, not passive. They required compelling and relevant projects, not lectures. Students should become problem solvers. Interest, not fear, should be used to motivate them. They should cooperate, not compete.

Boys in Armstrong Technical High School in Washington, D.C., construct models of airplanes in 1942 to be used by the U.S. Navy. Dewey advocated for democratized education that was relevant and practical.

—Marjory Collins / Library of Congress

The key to the new education was “manual training.” Before the factory system and the growth of cities, children handled animals, crops, and tools. They were educated by nature “with real things and materials.” Dewey lamented the disappearance of the idyllic village and the departure of children’s modesty, reverence, and implicit obedience. He was, however, no reactionary: “It is radical conditions which have changed, and only an equally radical change in education suffices.” Urban children needed to sew, cook, and work with metal and wood. Manual training should not, however, be mere vocational education or a substitute for the farm. It should be scientific and experimental, an introduction to civilization.

“You can concentrate the history of all mankind into the evolution of flax, cotton, and wool fibers into clothing,” asserted Dewey. He described a class where students handled wool and cotton. As they discovered how hard it was to separate seeds from cotton, they came to understand why their ancestors wore woolen clothing. Working in groups to make models of the spinning jenny and the power loom, they learned cooperation. Together they understood the role of water and steam, analyzed the textile mills of Lowell, and studied the distribution of the finished cloth and its impact on everyday life. They learned science, geography, and physics without textbooks or lectures. Learning by doing replaced learning by listening.

Manual training revolved around the study of occupations to develop both the hand and the intellect. To know and to do were equally valuable. Cooperative learning encouraged a democratic classroom, which promoted a democratic society without elites, ethnic divisions, or economic inequality. Throughout his life, Dewey believed that humans were social beings inclined to be cooperative, not selfish individuals predisposed to conflict. Always he praised democracy as a way of life and scientific intelligence as the key to reform.

America in 1900 was preoccupied with the clash between capital and labor, debating how to make the worker more than an appendage to the machine. To science, geography, and physics, Dewey added another advantage: meaning. While the typical student did not go on to high school or attend college, manual training conducted by a skilled teacher could stimulate the imagination, enlarge the sympathies, and acquaint young people with scientific intelligence. Dewey was outraged that “thousands of young ones . . . are practically ruined . . . in the Chicago schools every year.” His new education sought to encourage students to continue in school and combat the increase in juvenile delinquency. It looked to produce an inquiring student who could change America.

Running through The School and Society is a suspicion of the intellectual who wants to monopolize knowledge and keep it abstract. Dewey opposed the academic curriculum revolving around classical languages and high culture, which he believed suited an aristocracy, not a democracy. “The simple facts of the case are that in the great majority of human beings,” he wrote, “the distinctively intellectual interest is not dominant. They have the so-called practical impulse and disposition.” With more and more Americans enrolled in schools, educators had to acknowledge this fact. Learning had to be democratized and made relevant and practical. “The school must represent present life.”

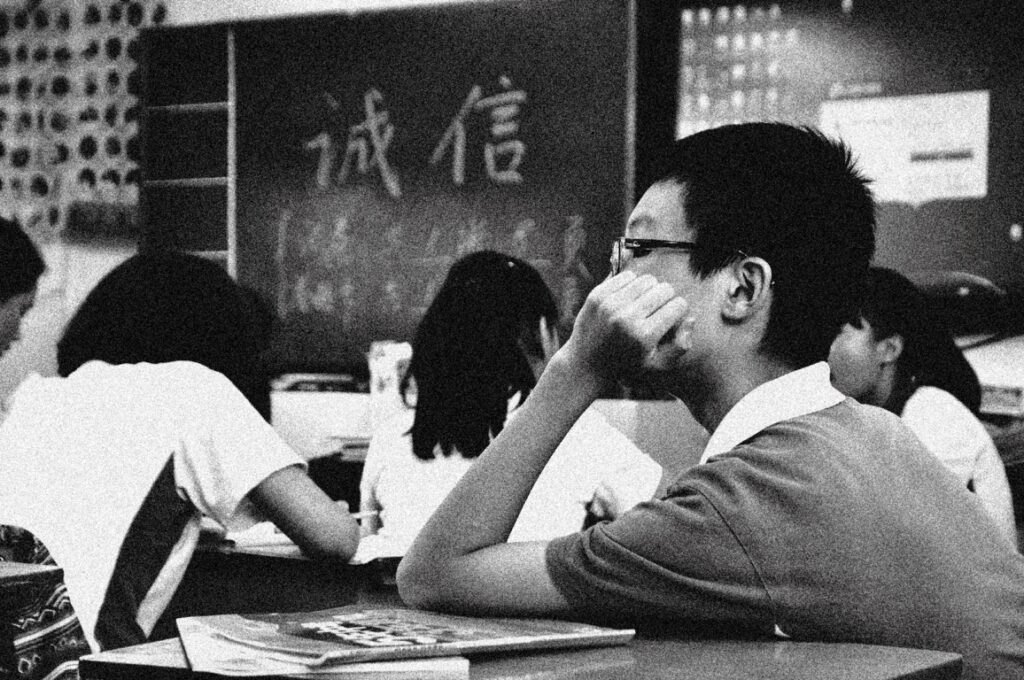

Classes modeled on Dewey’s principles emphasize cooperation over competition.

—Mauritius images GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Who was this philosopher who believed that children are curious and good, who would introduce them to civilization through wool and cotton, who would create cooperative classrooms that would end divisions between managers and workers and democratize America? Dewey lived from the Civil War to the Cold War, wrote 37 books, and published 766 articles in 151 journals. In his lifetime, he was hailed as America’s preeminent philosopher. Historian Henry Steele Commager called him “the guide, the mentor, and the conscience of the American people.” In China, he was called a “second Confucius.”

John Dewey grew up in Burlington, Vermont, the son of a pious, high-minded mother and a well-read grocer father. Shy and withdrawn, the young Dewey read voraciously and graduated from the University of Vermont. Uncertain about a career, he moved to Oil City, Pennsylvania, to teach Latin and algebra at the local high school. An average teacher but an ambitious intellectual, he decided to become a philosopher and fought to gain admission to Johns Hopkins University, which was dedicated to original research. He graduated with a PhD in philosophy. The president of Johns Hopkins, Daniel Coit Gilman, encouraged Dewey to accept an offer to teach at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor but suggested that he curtail his “reclusive and bookish habits.”

At Michigan, a newly confident Dewey published a psychology textbook and fell in love with one of his students, Alice Chipman (later described by their daughter as a woman “with a brilliant mind which cut through sham and pretense”). Influenced by Alice, Dewey paid more attention to social problems. They started a family and, observing his children, he applied his psychological insights to their upbringing, becoming increasingly more interested in education, so that his children might escape what he felt were the shortcomings of the schools he attended as a child.

One of his students in Michigan described Dewey as “a tall, dark, thin young man with long black hair, and a soft, penetrating eye, and looks like a cross between a Nihilist and a poet.” A colleague at Michigan found him “simple, modest, utterly devoid of any affectation or self-consciousness, and makes many friends and no enemies.” Later associates would corroborate this positive portrait, stressing Dewey’s ability to accept criticism, his willingness to give credit to others, and his intellectual and physical vigor. After a lunch (hosted by T. S. Eliot) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Bertrand Russell praised Dewey: “To my surprise I liked him very much. He has a large slow-moving mind, very empirical and candid . . . [he] impressed me very greatly, both as a philosopher and as a lovable man.” Self-effacing but not introspective, Dewey spoke little about himself, writing neither memoirs nor an autobiography.

Dewey, who seemed to fit the model of the quintessential reserved New Englander, was surprisingly complex. Arriving in Chicago during the strike, he mused, “I am something of an anarchist.” Slightly bohemian, he encouraged his children to go barefoot even in winter, and he and his wife walked naked around the house. He socialized with radicals in Greenwich Village. To understand prostitution, he visited Chicago’s brothels. He wrote passionate love letters to his wife and rhapsodized over the endearing qualities of his children. Once reclusive, he happily worked on philosophic tracts as his children crawled around his desk. His friend Max Eastman noted, “Dewey is at his best with one child climbing up his pants leg and another fishing in his inkwell.” At the age of 58, he had a brief romance (possibly platonic) with Anzia Wezierska, who wrote novels and short stories about the immigrant experience. He wrote poems to her and for himself about the anxiety of philosophizing, poems without literary flair that he never expected would be published.

Away from his family, Dewey could slip into melancholy. In 1894, he wrote to Alice, “I think yesterday was the bluest day I have ever spent.” He was twice visited by catastrophe. While vacationing in Italy in the fall of 1894, his youngest son, Morris, died of diphtheria at age two and a half, a loss from which he and Alice never fully recovered. Ten years later, during his second European trip, his eight-year-old son, Gordon, contracted typhoid fever and died in Ireland. “I shall never understand why he was taken from the world,” wrote Dewey.

Dewey marched in a suffragette parade and campaigned for women’s right to vote. He celebrated as his mentors Ella Flagg Young, the superintendent of Chicago Public Schools, and Jane Addams, the founder of Hull House. He rejected his mother’s query, “Are you right with Jesus?,” but sprinkled his essay “My Pedagogic Creed” with religious imagery. Who were Dewey’s heroes? Thomas Jefferson and Walt Whitman, the apostles of democracy; William James, the founder of pragmatism; and Eugene Debs, the champion of radical reform.

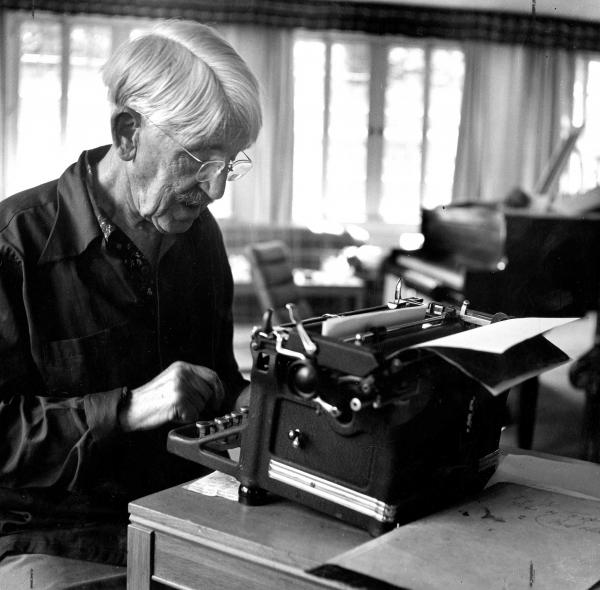

Suspicious of capitalism, this philosopher, the father of six children, had to deal with money. He demanded raises from college presidents, taught extra classes, and moved from apartment to apartment nine times between 1905 and 1914 in a gentrified New York. A workaholic, he pounded away at his typewriter and stopped reading for six months because of eyestrain.

Why were students drawn to Dewey? He was not a mesmerizing lecturer, sitting at a table in front of the class with a single piece of paper and thinking aloud. Irving Edman (who became a philosopher) was initially repelled by this method, but looking over his notes, he soon realized “what had seemed so rambling . . . was of extraordinary coherence, texture and brilliance.” Dewey’s former student and later colleague, the philosopher J. H. Randall Jr., described a man who was “simple, sturdy, unpretentious, quizzical, shrewd, devoted, fearless, genuine.” Dewey had, according to biographer Jay Martin, “a general spiritedness and joviality . . . that attracted people of all ages, genders and races.”

After leaving Ann Arbor and following his dramatic entrance into Chicago during the Pullman Strike, Dewey spent ten years at the University of Chicago, becoming more radical and more famous. Before he published his groundbreaking essay, Dewey had to test his half-formed ideas in a real school, thus he and his wife ran the Lab School at the University of Chicago from 1894 to 1905. Classes were small and select. Dewey drew on the expertise of Chicago’s professors to create age-appropriate curriculums, stressing discovery and cooperation and the talents of creative teachers to implement it. The Dewey school was distinctly middle class, with motivated students and supportive parents.

Visitors came from all over America and Dewey’s vision spread, so much so that he and his daughter Evelyn co-authored the 1915 book Schools of Tomorrow , a celebration of progressive pedagogy, complete with 27 photographs of children at work and play. In these schools, students visited fire stations, post offices, and city halls. They grew their own gardens, cooked, cobbled shoes, and tutored younger students. They staged plays dramatizing historical events. Pretending to be the heroes of the Trojan War, they held battles at recess with wooden swords and barrel-cover shields. Reading, writing, spelling, and calculating would be acquired naturally in conjunction with projects: “Studying alone out of a book is an isolated and unsocial performance,” the Deweys reminded readers of Schools of Tomorrow . The schools portrayed were chiefly elementary, and it is important to remember that Dewey’s reforms were rarely extended to rapidly growing high schools and less tractable adolescents.

In the John Dewey School in Denver in 1964, eighth graders create mosaic murals to decorate school corridors and offices. The activity demonstrates the Dewey principle of manual training—active rather than passive learning, “with real things and materials.”

—Ed Maker / Denver Post via Getty Images

Following a long-simmering conflict with University of Chicago President William Rainey Harper, Dewey—now prominent—moved to Columbia University in 1905. He remained there until 1930, teaching, lecturing in schools and community centers, traveling abroad to advise foreign educators, and writing articles for learned journals and popular magazines like the New Republic . Dewey believed that a philosopher should not only reflect but also act, both to improve society and to participate in “the living struggles and issues of his age.” His tools: reason, science, pragmatism. His goal: democracy, not only in politics and the economy but also as an ethical ideal, as a way of life.

As an activist and public intellectual, Dewey made a stunning series of contributions. He founded the American Association of University Professors and helped organize the New York City Teachers Union. He supported efforts that led to the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the American Civil Liberties Union. He worked in settlement houses to help assimilate immigrants, spoke out against the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, defended Bertrand Russell when Russell’s morals were questioned, and sided with historian Harold Rugg when Rugg’s books were censored. In response to feelings of guilt he harbored about his support for World War I, Dewey led a crusade that culminated in the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact, an influential though controversial treaty outlawing war.

During the 1920s, Dewey’s influence became international. He traveled with Alice to Japan in 1919, where he criticized the emperor cult, and lived in China for more than two years, giving two hundred lectures. The Chinese called him “Mr. Democracy” and “Mr. Science.” His books have been translated into Mandarin, and scholars at the Center for Dewey Studies at Southern Illinois University remind me that his emphasis on discovery and ethics has influenced contemporary Chinese educators trying to encourage creativity and virtue in students. Dewey went on to travel to Turkey, South Africa, and Mexico, advising governments on how to improve their educational systems. Today, in eleven countries, ranging from Italy to Argentina, that traditionally educate their students with lectures, memorization, and exams, there are Dewey centers that look to humanize education and consider the wider aspects of his philosophy.

John Dewey’s seventieth birthday on October 20, 1929, just before the stock market crash, became a national event. He had received numerous honorary degrees, declarations from foreign nations, and a portrait bust by the famous sculptor Jacob Epstein. From all over the world came telegrams, including tributes from Supreme Court Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes and Felix Frankfurter. Twenty-five hundred notables crowded into the Astor Hotel’s Grand Ballroom to hear Dewey compared to Ben Franklin and praised by historian James Harvey Robinson as “the chief spokesman of our age and the chief thinker of our days.”

Surrounded by children in 1949, John Dewey celebrates his ninetieth birthday at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City.

—Gado Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Not all Americans praised John Dewey. From his days at the Experimental School in Chicago until his death in 1952, he was the object of sharp criticism. Some parents in Chicago claimed that after a morning of chaotic play in the Dewey school, they had to teach their children how to read and write. Immigrants in New York City violently protested against manual training in 1915. They wanted a classical education so that their children could go to college and become professionals. Theologian Reinhold Niebuhr found Dewey’s view of human nature too optimistic, his view of society utopian.

The controversy surrounding Dewey continued after his death. “The 1950s was a horrible decade for progressive educators,” notes educational historian Diane Ravitch. In Educational Wastelands: The Retreat from Learning in Our Public Schools (1953), Arthur Bestor mocked the fad of “life adjustment” and called for a return of the “academic curriculum.” Admiral Hiram Rickover, the father of the nuclear-powered submarine, attributed Russia’s achievement with Sputnik to Dewey and his followers. In Life magazine, President Eisenhower blamed America’s educational failings on “John Dewey’s teachings.”

The controversy continues today. Analytic philosophers have little use for a sage who was not interested in arcane disputes over language. The champion of cultural literacy, E. D. Hirsch, insists that the education-school professors who lionize Dewey instruct future teachers to eschew facts, completion, testing, and lectures. In 2011, Human Events , a conservative weekly, listed Democracy and Education among the most dangerous books published in the past two hundred years.

Perhaps Dewey’s greatest liability was his style. Concerning clarity, the nineteenth-century philosopher Herbert Spencer once wrote: “To so present ideas that they may be apprehended with the least possible effort.” Dewey read Spencer but did not follow this advice. The editor of the New Republic regularly rewrote Dewey’s submissions. Defenders detect profundity beneath obscurity and argue that Dewey deliberately adopted an antirhetorical writing style. Critics demand clarity and example, maybe some rhythm and grace—missing in a philosopher who had no ear for music. I have met many contemporary teachers who have heard of John Dewey. I have not met one who has read his works, except reluctantly.

Of course, any philosopher who becomes famous can expect critiques and may become attractive to followers who will distort his or her message. The distortion will be magnified when the philosopher writes a lot, especially in an abstract and imprecise style. As a result, sweet-tempered John Dewey, who welcomed dialog and experimentation, is blamed for any change that opponents can label “progressive”: open classrooms, cooperative learning, life adjustment, language reading, the attacks on Latin and canonical books, the slighting of the gifted and talented, declining test scores. The assaults can be expanded to include social ills as well as educational shortcomings: communism, creeping socialism, juvenile delinquency, declining patriotism, a weakened military, and a less productive economy. Both Catholics and Communists reviled Dewey.

Patiently, Dewey defended himself. He reminded his educational disciples that students should not be allowed to do whatever they please, that planning and organization must accompany freedom, and that teachers should be guides as well as subject matter experts. While many forms of progressive education were spreading in America, he insisted in his 1938 book, Experience and Education , that education should not be without direction.

What are we to make of John Dewey? His FBI file mentioned his carelessly combed gray hair, disheveled attire, and monotonous drawl. They might have added that he was agnostic in religion and radical in politics. He was a good husband and father and a generous colleague. Optimistic, hard-working, idealistic, he rejected the Lost Generation’s cynicism and Sigmund Freud’s pessimism and preoccupation with the unconscious. Biographer Alan Ryan notes, “He was uninterested in either his own or other people’s private miseries.” He did not comment on sexuality, the obsession of contemporary America. Unlike evolutionary psychologists, he believed nurture was more powerful than nature. He overcame a natural timidity to become a giant in the world of philosophy and insisted on a new role for the philosopher, combining contemplation with action.

The words authority , discipline , deferred gratification , tradition , hierarchy , and order , were not part of his vocabulary. He favored community , equality, activity , freedom . He had no use for McGuffey Readers, designed to instill character, patriotism, and love of God. He criticized the Gilded Age, the Roaring Twenties, and the New Deal. He believed in unions, strikes, government planning, and redistribution of income. Opposed to laissez-faire capitalism, he was convinced that leaders were more dangerous than the masses.

Rejecting the specialization of contemporary philosophers, Dewey tackled logic, ethics, aesthetics, and epistemology. He commented on war and peace, labor unions, and capitalists. Above all, he transformed schools, connecting students to real life, encouraging them to become critical thinkers and idealists.

The philosopher and educator, photographed here in 1946, wrote 37 books and published 766 articles over his lifetime.

—JHU Sheridan Libraries / Gado Images / Getty

What is Dewey’s legacy? President Lyndon Johnson (once a teacher) extolled “Dr. Johnny” and connected Dewey’s ideas to the Great Society. Southern Illinois University has created a center for Dewey studies and published 37 volumes of his writings as well as twenty-four thousand pieces of his correspondence. The former editor, Larry Hickman, tells me there has been a revival of interest in Dewey after years of neglect. He argues that Dewey’s pluralism encourages “global citizenship.” He notes that after World War II, Japanese educators turned to Dewey and adds that he has a following among millions of Japanese Buddhists.

There is a John Dewey Society in America and John Dewey Study Centers around the world. Deborah Meier, the only elementary school teacher ever to receive a MacArthur “Genius” award, repeatedly cites Dewey’s influence on her democratic, project- and community-based schools. The Coalition for Essential Schools, whose slogan is “less is more,” is based on Dewey progressivism. Left-leaning public intellectuals and professors Cornel West and Noam Chomsky champion Dewey as an enemy of elites and founder of participatory democracy. The late Richard Rorty, an iconoclastic and controversial but prominent philosopher, rediscovered Dewey in the 1980s and praised Dewey’s pragmatism, political engagement, and vision for a democratic utopia (which Rorty says will never happen).

Echoing Dewey’s conclusion in “My Pedagogic Creed,” many contemporary psychologists insist that human beings are wired to be social, craving group activity and connections. In addition to evidence from brain imaging unavailable in Dewey’s time, they cite the ubiquity of iPhones and the power of Facebook. Communitarians who feel America’s celebration of individualism has gone too far quote Dewey.

“Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp,” advised Robert Browning, Dewey’s favorite poet. Dewey was a radical reformer, a socialist, a secular humanist, a meliorist, even a utopian. He dreamed of an America without sexism or racism or ethnic divisions, a community that respected capitalists as well as craftspeople and that cultivated both science and art. His dense, turgid philosophical tracts are now of interest primarily to academicians; his more readable journalism remains of use to historians; his educational writings prove the most influential.

Contemporary Americans have opted for testing, standards, competition, choice, and academic curriculums. Education reports emphasize national security, jobs, and the achievement gap, not discovery, manual training, or community. Deliberately antiprogressive charter schools, such as the KIPP Schools and Success Academies, try to overcome the achievement gap and end poverty by content, competition, and discipline. They stress grit, not joy. Teachers, denied the status Dewey thought so important, still stand in front of the class and talk. Progressive schools are few and seem most effective in small schools staffed by “true believers.”

Still, glimmers of Dewey’s dream remain. In the New Haven middle school of my thirteen-year-old grandson, the social studies teacher started the year by asking, “Why study history?” The mathematics teacher showed the movie Stand and Deliver . The language arts teacher asked each student to share with the class their thoughts about their individually selected summer reading book. My grandson chose a trilogy, The Hunger Games , not in the canon. The science teacher asked them to construct a model bridge out of one piece of paper and Scotch tape. To build community, the principal suspended classes, led the students outside, and asked each to start a conversation with someone he or she had not talked to before that morning.

Today most K–12 teachers still believe in content, competition, evaluation, and discipline. Simultaneously, they believe in relevance, projects, group learning, and choice. The Common Core Standards, approved by most states, stress rigor but at the same time emphasize inquiry and understanding. John Dewey would be moderately pleased with a pragmatic nation that combines traditional education with the insights of progressives.

Peter Gibbon is a Senior Research Scholar at the Boston University School of Education and the author of A Call to Heroism: Renewing America’s Vision of Greatness (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2002). He has directed four Teaching American History programs and is currently the director of an NEH Summer Seminar, “Philosophers of Education: Major Thinkers from the Enlightenment to the Present.”

Funding information

NEH has awarded 19 grants, totaling $3,091,240, on John Dewey to Southern Illinois University for publication of the Collected Works, in 37 volumes, and an electronic edition of Dewey’s correspondence.

Republication statement

The text of this article is available for unedited republication, free of charge, using the following credit : “Originally published as “John Dewey: Portrait of a Progressive Thinker” in the Spring 2019 issue of Humanities magazine, a publication of the National Endowment for the Humanities.” Please notify us at @email if you are republishing it or have any questions.

John Dewey on Education: Selected Writings by Reginald A. Archambault, ed., University of Chicago Press, 1964. Understanding John Dewey: Nature and Cooperative Intelligence by James Campbell, Open Court, 1995. Democracy and Education by John Dewey, The Macmillan Company, 1916. Schools of Tomorrow by John Dewey and Evelyn Dewey, Grindl Press, 2016. The Education of John Dewey: A Biography by Jay Martin, Columbia University Press, 2002. The Metaphysical Club by Louis Menand, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2001. John Dewey and the High Tide of American Liberalism by Alan Ryan, W. W. Norton & Company, 1995.

SUBSCRIBE FOR HUMANITIES MAGAZINE PRINT EDITION Browse all issues Sign up for HUMANITIES Magazine newsletter

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

- Corpus ID: 146746279

JOHN DEWEY AND PROGRESSIVISM IN AMERICAN EDUCATION

- Lucian Radu

- Published 2011

- Philosophy, Education

12 Citations

Learning through a scientific approach from the philosophy of progressivism, konsep pendidikan merdeka belajar perspektif filsafat progresivisme (the emancipated learning concept of education in progressivism philosophy perspective), education for public good in the age of coloniality: implications for pedagogy, the philosophy of contemporary education and its implications for the development of islamic education, authentic learning in african post-secondary education and the creative economy, overview of theories, models and political discourse on education, democracy and freedom, philippines: strength and weakness of science curricula, a comparative analysis of al-ghazali and montessori’s principles of child education (analisis komparatif terhadap prinsip-prinsip al-ghazali dan montessori dalam pendidikan kanak-kanak ), critical analysis on how learner-related factors affect application of progressivists' learner-centered approaches in teaching and learning of mathematics: a case of meru south sub- county, tharaka nithi county, kenya., teaching philosophy statement for physics teachers: let’s think about.

- Highly Influenced

12 References

Democracy and education : an introduction to the philosophy of education, the influence of darwin on philosophy, education for a changing civilization: three lectures delivered on the luther laflin kellogg foundation at rutgers university, 1926, the practical character of reality, școala și doctrinele pedagogice în secolul xx, progressive education at the crossroads, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Pragmatism and Progressivism in the Educational Thought and Practices of Booker T. Washington

2013, Philosophical Studies in Education

Related Papers

Donald Generals

American Literature

Laura Fisher

Journal of Policy History

Richard Valelly

Greg Gabrellas

La Shun Carroll

This paper explores the rationale behind Booker T. Washington’s vocationalist philosophy of education for the then recently emancipated black population. Through the use of a critical thinking framework, an analysis of remarks from key speeches and his life according to scholars providing Washington’s prescriptive argument and rhetoric is undertaken. Despite Washington’s intentions, the argument for his vocational approach is demonstrated to be oppressive, myopic, and circular in its logic. The author proposes a framework for understanding the counterintuitive development of vocationalist philosophy based on the dichotomous nature of the human experience’s value-construct and context misalignment. Concordant or discordant dualities that result from misalignment are explained and how to reconcile Washington’s Vocationalism with opposing the philosophy of W.E.B. Du Bois due to equivalence or consistency of values with theoretical constru...

Amy Guthrie

Michael Ivan Hartono

The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism

The Journal of Technology Studies

Elwood Watson

TR Berry , Michael Jennings

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Negro Education

Brian Jones

Fredrick Douglass Dixon

Anna Pochmara

Transit Circle: Revista Brasileira de Estudos Americanosot

José E N D O E N Ç A Martins

The Southern Literary Journal Volume XXXIX Spring 2007 No. 2, p. 1-23

Susanna Ashton

Marybeth Gasman

58 Villanova Law Review 471

Taunya Banks

Education and Capitalism: Struggles for Learning and Liberation

LaGarrett King , Anthony L. Brown

Online Submission

Reviews in American History

Anja Werner

Freedom Schools

Harry C Boyte

History of Education

Nick Juravich

Derrick Alridge

Philosophy of Education

Campbell Scribner

Journal of curriculum theorizing

Alexander Pratt

Review of Research in Education

William Tate

Journal of Black Studies

M. Keith Claybrook

Jeryl Raphael

Rebekah McCloud

InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies

Hugh Schuckman

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

PHILO-notes

Free Online Learning Materials

Progressivism in Education

Progressivism is an educational philosophy that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the United States. It emphasizes the importance of student-centered learning, experiential learning, and the development of critical thinking skills. In this essay, we will explore the meaning of progressivism in education, its key principles and practices, and its impact on modern education.

Meaning of Progressivism in Education

Progressivism is an educational philosophy that emphasizes the importance of student-centered learning. According to progressivists, students should be actively involved in their own learning process and should be encouraged to think critically and creatively. Progressivists believe that education should be based on the needs and interests of students and should be designed to help them become responsible and active members of society.

Key Principles of Progressivism in Education

1. Student-Centered Learning: Progressivism emphasizes the importance of student-centered learning. According to this philosophy, students should be actively involved in their own learning process and should be encouraged to think critically and creatively.

2. Experiential Learning: Progressivism emphasizes the importance of experiential learning. According to this philosophy, students should be given the opportunity to learn through hands-on experiences and real-world activities.

3. Critical Thinking Skills: Progressivism emphasizes the importance of critical thinking skills. According to this philosophy, students should be encouraged to question assumptions, analyze information, and develop their own ideas and opinions.

4. Active Learning: Progressivism emphasizes the importance of active learning. According to this philosophy, students should be encouraged to participate in discussions, debates, and other activities that promote learning.

5. Community Involvement: Progressivism emphasizes the importance of community involvement. According to this philosophy, students should be encouraged to participate in community activities and should be taught to be responsible and active members of society.

Practices of Progressivism in Education

1. Project-Based Learning: Project-based learning is a key practice of progressivism. According to this philosophy, students should be given the opportunity to work on real-world projects that are designed to help them develop critical thinking skills and learn through hands-on experiences.

2. Inquiry-Based Learning: Inquiry-based learning is another key practice of progressivism. According to this philosophy, students should be encouraged to ask questions, explore ideas, and develop their own understanding of the world around them.

3. Student-Led Discussions: Progressivism emphasizes the importance of student-led discussions. According to this philosophy, students should be encouraged to participate in discussions and debates and should be given the opportunity to share their own ideas and opinions.

4. Active Participation: Progressivism emphasizes the importance of active participation. According to this philosophy, students should be encouraged to participate in their own learning process and should be given the opportunity to take ownership of their education.

Impact of Progressivism on Modern Education

The impact of progressivism on modern education can be seen in a variety of ways. For example:

1. Student-Centered Learning: Many modern classrooms are designed to be student-centered, with an emphasis on hands-on learning, collaboration, and critical thinking skills.

2. Experiential Learning: Many modern schools offer programs and activities that are designed to help students learn through real-world experiences, such as internships, community service projects, and study abroad programs.

3. Active Learning: Many modern classrooms encourage active learning, with an emphasis on student participation in discussions, debates, and other activities.

4. Technology Integration: Many modern schools are integrating technology into the classroom, with an emphasis on using technology to enhance student learning and engagement.

5. Standards-Based Education: Many modern schools are adopting standards-based education, which emphasizes the importance of setting clear learning objectives and assessing student progress based on those objectives.

Why Progressivism Is Important in the Field of Education?

In education, there is a need for constant progress to ensure that students are getting the best possible education.

This means that educators must always be learning new techniques and approaches and adapting to the latest changes in their field.

Progressive educators are critical to this process, working tirelessly to push for change and innovation.

This blog post will explore the importance of progressivism in education and discuss why it is essential for the field.

Let’s get started.

Importance of Progressivism in the Field of Education:

Progressivism is a philosophy of education that emphasizes the need for students to learn through their own experiences and be actively involved in their own learning process.

It stresses the importance of learning by doing and encourages students to be curious and questioning.

Progressivism also emphasizes the need for educators to be flexible and responsive to the needs of individual students.

There are several reasons why progressivism is important in the field of education.

Emphasizes Active Learning

One of the most important aspects of progressive education is that students should be actively involved in their own learning.

This means that students should be given opportunities to explore their own interests and discover new things.

It also means that they should be encouraged to ask questions and think critically about the information they are presented with.

Encourages Creativity

Creative expression is an important aspect of progressive education.

This means that students should be given opportunities to express themselves creatively and explore their own ideas, which will help them learn in new ways with less risk or frustration than they would otherwise experience if left unchecked by outside influences such as parents who wantonly discourage exploration at every turn because “you can’t do anything worthwhile.”

Innovation is essential to success.

It means that you should encourage your kids, come up with new solutions for problems, and not be afraid of thinking outside the box!

Teaches Students How to Think, Not What to Think

One of the most important goals of progressive education is to teach students how to think, not what to think.

This is done by encouraging them to ask questions and think critically about the information they are presented with.

It is also important to provide them with multiple perspectives on any given issue to develop their own opinions.

Encourages Social Interaction

Progressive education also emphasizes the importance of social interaction.

This means that students should be given opportunities to work together and interact.

It is believed that this kind of interaction is essential for learning.

Promotes Individualized Instruction

Another important aspect of progressive education is the idea of individualized instruction.

This means that each student should be given instruction tailored to his or her own needs and abilities.

It is believed that this kind of instruction is more effective than one-size-fits-all instruction because it allows students to learn at their own pace and in their way.

Encourages Democratic Values

Progressive education also emphasizes the importance of democratic values.

This means that students should be taught to participate in their own governance and make decisions about their own education.

It is believed that this kind of education will promote democratic values and citizenship.

Encourages Lifelong Learning

Finally, progressive education emphasizes the importance of lifelong learning.

This means that students should be given opportunities to continue learning even after leaving the formal education system.

It is believed that this will help them succeed in their careers and personal lives.

Did You Know?

The progressive education movement began in the late 19th century due to the traditional, didactic educational methods that were prevalent at the time.

Proponents of progressive education believed that students should be actively engaged in their own learning and should be taught how to think, not just what to think.

The progressive education movement was spearheaded by John Dewey , who is considered the father of modern education .

Dewey’s ideas about education were based on his belief that learning should be a social process.

He believed that students should learn by doing and be allowed to explore their own interests.

Dewey’s ideas about education were controversial at the time, but they have had a lasting impact on the field of education. Today, many of the principles of progressive education are still used in schools worldwide.

John Dewey, an American educator and key figure in progressivism, wanted his students to have a democratic experience at school.

Instead of having one teacher who knew everything, there was known to stand up front talking all day long.

According to John’s philosophy on education, he believed that the kids themselves should be active participants during class time with opportunities for hands-on involvement, which stressed experiential learning over preparation based solely upon lectures or reading assignments.

How Is Progressivism Applied in the Classroom?

There is no one answer to this question, as progressivism can be applied in many ways in the classroom, depending on the class’s particular goals and objectives.

However, some common ways in which progressivism may be applied in the classroom include:

Student-Centered Learning

Student-centered learning is a method of instruction that focuses on the needs and interests of individual students.

This means that the curriculum is designed to meet the needs of each student and that students are given opportunities to direct their own learning.

Discovery Learning

Discovery learning is a revolutionary teaching method that encourages students’ natural ability and thirst for new information.

In addition, the method emphasizes self-discovery, which means they’re given plenty of opportunities in classrooms and outside them, exploring everything around them with questions at hand!

Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning is an innovative method of instruction that gives your students opportunities to work on long-term projects with real-world applications.

This means they will be able complete hands-on tasks, collaborate in groups (or even alone), and apply what’s learned throughout the course across various disciplines!

Cooperative Learning

Cooperative learning is a classroom environment that encourages student collaboration and competition.

In this sort, students are allowed to work on projects with their peers and learn from one another’s mistakes or successes!

It also helps them build stronger relationships with their peers, which can also lead to success outside of school!

Experiential Learning

Experiential learning is an exciting and engaging way for students to gain insight into their world.

Taking part in activities, watching videos, or reading articles about topics relevant to your course goals will give you new perspectives that can help guide future decisions!