.png)

- Apr 5, 2021

Euripides' Medea: Tragic Heroine or Malignant Villain? - by Lucy Moore

Euripides: Greek tragedian

King Aeetes of Colchis: Son of Helios, brother of Circe and Pasiphae

Jason: Greek mythological hero, leader of the Argonauts, husband to Medea

Golden Fleece: Golden wooled fleece belonging to the winged ram Chyrsomallos

Eponymous: Naming something after a person

Psychoanalytical: Investigating the interaction between consciousness and unconsciousness

Feminist Theory: Explanation of how gender systems work

Proto-feminist: The use of modern feminism when feminism as a concept was unknown

Euripides’ Greek tragedy ‘Medea’ was first composed in 431 BCE and explored the psyche and behaviours of Medea, the daughter of King Aeetes of Colchis and wife of Jason. The plot revolves around Medea’s descent into a complete rage infused revenge journey after her husband beds the Princess of Corinth. Her vengeance comes by murdering the princess and also the sons she shared with Jason. Euripides’ play has been dissected through many literary lenses throughout history: through the mediums of Psychoanalytical discovery, Feminist Theory and politics, just to name a few. Coming from a feminist point of view, the depiction of Medea can be seen on two polarising panels: on one side, she is a proto-feminist who is used to highlight the misogynistic attitudes of the contemporary periods and how women were simply restricted within their domestic sphere; however, on the other side she is the epitome of all that men feared that women could become: murderess, temptress and seductress. For many years the scholarly argument has raged whether Euripides’ intention was to portray his eponymous character as the ‘Tragic Heroine’ or the ‘Malignant Villain’ – was he trying to highlight societal and gender woes of the time, or was he simply a part of the patriarchal system that silenced the voices and freedom of women?

Medea’s main redemption as the tragic heroine is through the lens of feminism. Throughout the play, Medea defends her behaviour through her advocating for the rights of women as an extension of her own gender. Due to the patriarchal perspective of the period, women were seen as ‘mad’, with the idea that their womb would rage havoc around their body and would be tamed once they were impregnated – once again subconsciously highlighting the idea that a man was the only remedy to calm and tranquilise a woman. From the beginning of the tragedy, it is seen as one of Medea’s main motives to fight against the injustice women faced. When in public, to ensure she is listened to and respected, she restrains her temper and instead presents a logical and reasoned argument on behalf of women, as at the centre of Medea’s heart, she truly believes “there is no justice in the world for censorious eyes”. The idea of Medea as a tragic heroine through the lens of feminism would be an effective analysis from a modern-day point of view – perhaps Euripides did wish for the audience to sympathise and feel Medea’s pathos, or it could be his attempt to humanise the already demonised Medea to give her an arc, or simply to just make a mockery of Medea’s attempt to rationalise her fervent behaviour.

Medea’s relationship with her husband affects both her presentations as the tragic heroine and as the malignant villain. When Medea finds out about her husband’s disloyalty, her wails are heard offstage, which divides the attention between Medea’s heartbreak and Jason’s behaviour; full-fledged attention is not placed upon Medea’s outburst. On one hand, Euripides portrays Jason as a callous, cold-hearted husband but on the other, the playwright chastises Medea for her deception towards Jason. Throughout the play, Jason’s nature is unemotional but also manipulative: he finds pride in his tempestuous ploys but is naive enough to fail to recognise the deceit that is playing around him. Within the story of Medea and Jason, it is hard to dispute that Medea (in the beginning) did remain dedicated and loyal to her husband; she made significant sacrifices in regard to retaining the Golden Fleece and she undermines her own family values so Jason can fulfil his wish of wealth and security.

However, Euripides makes sure to remind the audience of Medea’s equal manipulative persona which leads her to the characterisation of the malignant villain. Medea is aware that Jason desires an obedient, calm, respectful wife to have as his trophy prize and therefore in order to conceal her plans, she pretends to be submissive which causes Jason to not suspect anything from her behaviour. Her main intention is to destroy Jason’s livelihood, which no longer consisted of her, just as he destroyed her trust and security and in the eyes of society, got off scot-free. Even though Medea’s deceit and manipulation are made explicit to the audience, it can be an honest revelation of how the suppression of female femineity within the domestic sphere can cause bubbling madness for an individual. Medea’s emotions are constantly suppressed by Jason’s dismissive nature towards her by labelling her grievances as sexual jealousy, and therefore she finds herself falling down into a gendered manmade rabbit hole of madness and tragic decline.

Medea’s own psychology and approach to the world around her is a monumental part of the weighing scales of her character trope. The only main indicator that Medea is aware of her destructive state is through her outwitting King Creon in order to accomplish her vengeance. Despite this, the rest of Medea’s psyche can be seen as her deterioration into madness. Her zealous exclamations to the Nurse and the Tutor, in particular, are key examples of the protagonist’s heartfelt despair and anger at her current situation – most predominately in a domestic space, as this is where women were confined to. It can be seen really that Euripides’ main intention is to show the psychological damage that extreme anguish and hatred can have upon someone’s behaviour and rational thought: the despondency paralyses Medea’s thought processes which leaves her causing and inflicting pain on others without realising it.

Overall, even though Euripides does attempt to portray Medea as the malignant villain, under all the layers, especially to a modern audience, she is truly the tragic heroine. The mental and domestic suppression Medea suffers at the hands of Jason and the patriarchal society causes her to spiral and become the villain the Greek audience would have deemed her as. But from a modern perspective, with a better understanding of sexist attitudes and misogynistic feelings, today’s audience can see that Medea truly is the tragic heroine and also, a victim of societal and domestic gendered abuse. A woman who held ascendancy as a princess became the archetype of evilness in female identity, when in fact, her nature and morality should have been seen as the product of her environment, not her own desired intentions.

Academus Education is an online learning platform providing free Classics Education to students through summer schools, articles and digital think tanks. If you wish to support us, please check out our range of merchandise, available now on Redbubble.

Recent Posts

The Greek Island as a place of allure: Cyprus, Naxos, and Love Island - by Morg Daniels

Aphrodite's Nudity: Empowering or Humiliating? - by Jess Huang

Glory on the track: what parallels can we draw between today’s Formula 1 and Ancient Chariot Races?

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Drama Criticism › Analysis of Euripides’ Medea

Analysis of Euripides’ Medea

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 13, 2020 • ( 0 )

When Medea, commonly regarded as Euripides’ masterpiece, was first per-formed at Athens’s Great Dionysia, Euripides was awarded the third (and last) prize, behind Sophocles and Euphorion. It is not difficult to understand why. Euripides violates its audience’s most cherished gender and moral illusions, while shocking with the unimaginable. Arguably for the first time in Western drama a woman fully commanded the stage from beginning to end, orchestrating the play’s terrifying actions. Defying accepted gender assumptions that prescribed passive and subordinate roles for women, Medea combines the steely determination and wrath of Achilles with the wiles of Odysseus. The first Athenian audience had never seen Medea’s like before, at least not in the heroic terms Euripides treats her. After Jason has cast off Medea—his wife, the mother of his children, and the woman who helped him to secure the Golden Fleece and eliminate the usurper of Jason’s throne at Iolcus—in order to marry the daughter of King Creon of Corinth, Medea responds to his betrayal by destroying all of Jason’s prospects as a husband, father, and presumptive heir to a powerful throne. She causes a horrible death of Jason’s intended, Glauce, and Creon, who tries in vain to save his daughter. Most shocking of all, and possibly Euripides’ singular innovation to the legend, Medea murders her two sons, allowing her vengeful passion to trump and cancel her maternal affections. Clytemnestra in Aeschylus’s Oresteia conspires to murder her husband as well, but she is in turn executed by her son, Orestes, whose punishment is divinely and civilly sanctioned by the trilogy’s conclusion. Medea, by contrast, adds infanticide to her crimes but still escapes Jason’s vengeance or Corinthian justice on a flying chariot sent by the god Helios to assist her. Medea, triumphant after the carnage she has perpetrated, seemingly evades the moral consequences of her actions and is shown by Euripides apotheosized as a divinely sanctioned, supreme force. The play simultaneously and paradoxically presents Medea’s claim on the audience’s sympathy as a woman betrayed, as a victim of male oppression and her own divided nature, and as a monster and a warning. Medea frightens as a female violator and overreacher who lets her passion overthrow her reason, whose love is so massive and all-consuming that it is transformed into self-destructive and boundless hatred. It is little wonder that Euripides’ defiance of virtually every dramatic and gender assumption of his time caused his tragedy to fail with his first critics. The complexity and contradictions of Medea still resonate with audiences, while the play continues to unsettle and challenge. Medea, with literature’s most titanic female protagonist, remains one of drama’s most daring assaults on an audience’s moral sensibility and conception of the world.

Euripides is ancient Greek drama’s great iconoclast, the shatterer of consoling illusions. With Euripides, the youngest of the three great Athenian tragedians of the fifth century b.c., Attic drama takes on a disturbingly recognizable modern tone. Regarded by Aristotle as “the most tragic of the poets,” Euripides provided deeply spiritual, moral, and psychological explorations of exceptional and domestic life at a time when Athenian confidence and certainty were moving toward breakup. Mirroring this gathering doubt and anxiety, Euripides reflects the various intellectual, cultural, and moral controversies of his day. It is not too far-fetched to suggest that the world after Athens’s golden age in the fifth century became Euripidean, as did the drama that responded to it. In several senses, therefore, it is Euripides whom Western drama can claim as its central progenitor.

Euripides wrote 92 plays, of which 18 have survived, by far the largest number of works by the great Greek playwrights and a testimony both to the accidents of literary survival and of his high regard by following generations. An iconoclast in his life and his art, Euripides set the prototype for the modern alienated artist in opposition. By contrast to Aeschylus and Sophocles, Euripides played no public role in the life of his times. An intellectual and artist who wrote in isolation (tradition says in a cave in his native Salamis), his plays won the first prize at Athens’s annual Great Dionysia only four times, and his critics, particularly Aristophanes, took on Euripides as a frequent tar-get. Aristophanes charged him with persuading his countrymen that the gods did not exist, with debunking the heroic, and with teaching moral degeneration that transformed Athenians into “marketplace loungers, tricksters, and scoundrels.” Euripides’ immense reputation and influence came for the most part only after his death, when the themes and innovations he pioneered were better appreciated and his plays eclipsed in popularity those of all of the other great Athenian playwrights.

Critic Eric Havelock has summarized the Euripidean dramatic revolution as “putting on stage rooms never seen before.” Instead of a palace’s throne room, Euripides takes his audience into the living room and presents the con-fl icts and crises of characters who resemble not the heroic paragons of Aeschylus and Sophocles but the audience themselves—mixed, fallible, contradictory, and vulnerable. As Aristophanes accurately points out, Euripides brought to the stage “familiar affairs” and “household things.” Euripides opened up drama for the exploration of central human and social questions embedded in ordinary life and human nature. The essential component of all Euripides’ plays is a challenging reexamination of orthodoxy and conventional beliefs. If the ways of humans are hard to fathom in Aeschylus and Sophocles, at least the design and purpose of the cosmos are assured, if not always accepted. For Euripides, the ability of the gods and the cosmos to provide certainty and order is as doubtful as an individual’s preference for the good. In Euripides’ cosmogony, the gods resemble those of Homer’s, full of pride, passion, vindictiveness, and irrational characteristics that pattern the world of humans. Divine will and order are most often in Euripides’ dramas replaced by a random fate, and the tragic hero is offered little consolation as the victim of forces that are beyond his or her control. Justice is shown as either illusory or a delusion, and the myths are brought down to the level of the familiar and the recognizable. Euripides has been described as drama’s first great realist, the playwright who relocated tragic action to everyday life and portrayed gods and heroes with recognizable human and psychological traits. Aristotle related in the Poetics that “Sophocles said he drew men as they ought to be, and Euripides as they were.” Because Euripides’ characters offer us so many contrary aspects and are driven by both the rational and the irrational, the playwright earns the distinction of being considered the first great psychological artist in the modern sense, due to his awareness of the complex motives and ambiguities that make up human identity and determine behavior.

Tragedy: An Introduction

Euripides is also one of the first playwrights to feature heroic women at the center of the action. Medea dominates the stage as no woman character had ever done before. The play opens with Medea’s nurse confirming how much Medea is suffering from Jason’s betrayal and the tutor of Medea’s children revealing that Creon plans to banish Medea and her two sons from Corinth. Medea’s first words are an offstage scream and curse as she hears the news of Creon’s judgment. The Nurse’s sympathetic reaction to Medea’s misery sounds the play’s dominant theme of the danger of passion overwhelming reason, judgment, and balance, particularly in a woman like Medea, unschooled in suffering and used to commanding rather than being commanded. Better, says the Nurse, to have no part of greatness or glory: “The middle way, neither high nor low is best. . . . Good never comes from overreaching.” Medea then takes the stage to win the sympathy of the Chorus, made up of Corinthian women. Her opening speech has been described as one of literature’s earliest feminist manifestos, in which she declares, “Of all creatures on earth, we women are the most wretched,” and goes on to attack dowries that purchase husbands in exchange for giving men ownership of women’s bodies and fate, arranged marriages, and the double standard:

When a man grows tired of his wife and home, He is free to look about for someone new. We wives are forced to count on just one man. They say, we live safe at home while men go to battle. I’d rather stand three times in the front line than bear one child!

Medea wins the Chorus’s complicit silence on her intended intrigue to avenge herself on Jason and their initial sympathy as an aggrieved woman. She next confronts Creon to persuade him to postpone his banishment order for one day so she can arrange a destination and some support for her children. Medea’s servility and deference to Creon and the sentimental appeal she mounts on behalf of her children gain his concession. After he departs, Medea reveals her deception of and contempt for Creon, announcing that her vengeance plot now extends beyond Jason to include both Creon and his daughter.

There follows the first of three confrontational scenes between Medea and Jason, the dramatic core of the play. Euripides presents Jason as a selfsatisfied rationalist, smoothly and complacently justifying the violations of his love and obligation to Medea as sensible, accepted expedience. Jason asserts that his self-interest and ambition for wealth and power are superior claims over his affection, loyalty, and duty to the woman who has betrayed her parents, murdered her brother, exiled herself from her home, and conspired for his sake. Medea rages ineffectually in response, while attempting unsuccessfully to reach Jason’s heart and break through an egotism that shows him incapable of understanding or empathy. As critic G. Norwood has observed, “Jason is a superb study—a compound of brilliant manners, stupidity, and cynicism.” In the drama’s debate between Medea and Jason, the play brilliantly sets in conflict essential polarities in the human condition, between male/female, husband/wife, reason/passion, and head/heart.

Before the second round with Jason, Medea encounters Aegeus, king of Athens, who is in search of a cure for his childlessness. Medea agrees to use her powers as a sorceress to help him in exchange for refuge in Athens. Aristotle criticized this scene as extraneous, but a case can be made that Aegeus’s despair over his lack of children gives Medea the idea that Jason’s ultimate destruction would be to leave him similarly childless. The evolving scheme to eliminate Jason’s intended bride and offspring sets the context for Medea’s second meeting with Jason in which she feigns acquiescence to Jason’s decision and proposes that he should keep their children with him. Jason agrees to seek Glauce’s approval for Medea’s apparent selfsacrificing generosity, and the children depart with him, carrying a poisoned wedding gift to Glauce.

First using her children as an instrument of her revenge, Medea will next manage to convince herself in the internal struggle that leads to the play’s climax that her love for her children must give way to her vengeance, that maternal affection and reason are no match for her irrational hatred. After the Tutor returns with the children and a messenger reports the horrible deaths of Glauce and Creon, Medea resolves her conflict between her love for her children and her hatred for Jason in what scholar John Ferguson has called “possibly the finest speech in all Greek tragedy.” Medea concludes her self-assessment by stating, “I know the evil that I do, but my fury is stronger than my will. Passion is the curse of man.” It is the struggle within Medea’s soul, which Euripides so powerfully dramatizes, between her all-consuming vengeance and her reason and better nature that gives her villainy such tragic status. Her children’s offstage screams finally echo Medea’s own opening agony. On stage the Chorus tries to comprehend such an unnatural crime as matricide through precedent and concludes: “What can be strange or terrible after this?” Jason arrives too late to rescue his children from the “vile murderess,” only to find Medea beyond his reach in a chariot drawn by dragons with the lifeless bodies of his sons beside her. The roles of Jason and Medea from their first encounter are here dramatically reversed: Medea is now triumphant, refusing Jason any comfort or concession, and Jason ineffectually rages and curses the gods for his destruction, now feeling the pain of losing everything he most desired, as he had earlier inflicted on Medea. “Call me lioness or Scylla, as you will,” Medea calls down to Jason, “. . . as long as I have reached your vitals.”

Medea’s titanic passions have made her simultaneously subhuman in her pitiless cruelty and superhuman in her willful, limitless strength and determination. The final scene of her escape in her god-sent flying chariot, perhaps the most famous and controversial use of the deus ex machina in drama, ultimately makes a grand theatrical, psychological, and shattering ideological point. Medea has destroyed all in her path, including her human self, to satisfy her passion, becoming at the play’s end, neither a hero nor a villain but a fear-some force of nature: irrational, impersonal, destructive power that sweeps aside human aspirations, affections, and the consoling illusions of mercy and order in the universe.

Share this:

Categories: Drama Criticism , Literature

Tags: Analysis of Euripides’ Medea , Bibliography of Euripides’ Medea , Character Study of Euripides’ Medea , Criticism of Euripides’ Medea , Essays of Euripides’ Medea , Euripides , Euripides’ Medea , Literary Criticism , Medea , Medea Play , Medea Play Analysis , Medea Play as a Tragedy , Medea Play Summary , Medea Play Theme , Notes of Euripides’ Medea , Plot of Euripides’ Medea , Simple Analysis of Euripides’ Medea , Study Guide of Alexander Pope's Imitations of Horace , Study Guides of Euripides’ Medea , Summary of Euripides’ Medea , Synopsis of Euripides’ Medea , Themes of Euripides’ Medea

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Medea is an enchantress and the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis (a city on the coast of the Black Sea). In Greek mythology , she is best known for her relationship with the Greek hero Jason, which is famously told in Greek tragedy playwright Euripides ' (c. 484-407 BCE) Medea and Apollonius of Rhodes ' (c. 295 BCE) epic Argonautica .

Throughout history, Medea is portrayed as a strong, ruthless, bloodthirsty woman who betrayed her own people and killed her brother and children. Yet, despite her life being touched by many tragedies and scandals (most caused by her own hand), she remained resilient, becoming immortal and living out her days in the paradise of the Elysian Fields.

Birth & Family

Medea is the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis and Eidyia, the daughter of Oceanus and Tethys, as well as the granddaughter of Helios , the god of the sun, and the niece of Circe , another famous sorceress in Greek mythology .

The famous daughter of Ocean, Perseus , Bore to her mate, untiring Helios, Circe and King Aeëtes. He, the son Of Helios. Who brings light to mortal men, Was married to Iduia the fair-cheeked Daughter of Ocean, earth's last stream, by will Of the immortals , and subdued by love Through golden Aphrodite 's work, she bore To him Medea with the graceful feet. ( Hesiod , Theogony , 953-962)

Medea & Jason

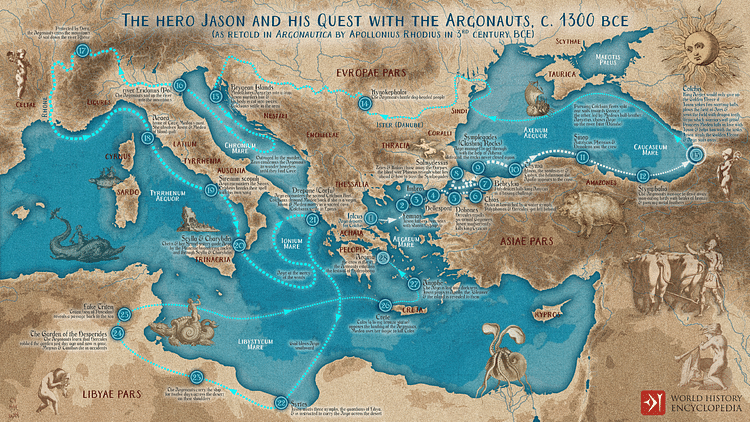

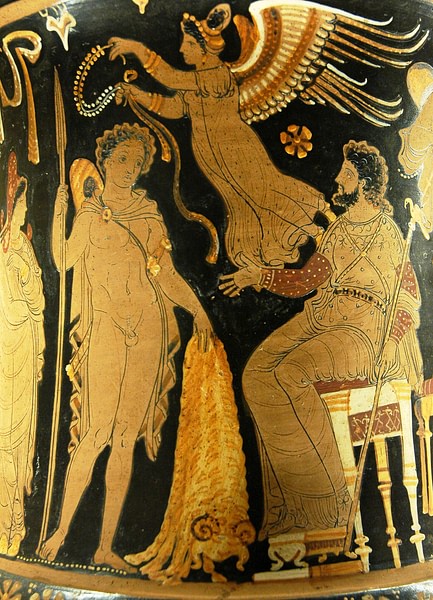

Jason challenged his uncle Pelias for the throne of Iolcus and accepted the mission of retrieving the Golden Fleece . The goddesses on Mount Olympus took great interest in this quest, and Aphrodite persuaded her son, Eros, to strike Medea with his arrow, making her fall in love with Jason.

Jason and the Argonauts arrived in Colchis to ask Medea's father, King Aeëtes, for the Golden Fleece. King Aeëtes agreed to give Jason the Golden Fleece, but only if he could complete a series of tasks. First, he had to yoke two fire-breathing bulls, then plough a field and sow it with serpent's teeth, which would then transform into warriors. Jason grew anxious, but Medea offered to help him by giving him a magic ointment made from the crocus flower to spread on his sword, shield, and body. This ointment would protect him from the fiery breath of the bull. Medea asked for one thing in return for her help; for Jason to marry her and take her away from Colchis.

King Aeëtes refused to hand over the Golden Fleece once Jason had successfully completed the deadly tasks. Waiting for night to fall, Medea led Jason to the fleece, which was guarded by a ferocious dragon. She put the dragon into a drug-induced sleep, and they took the fleece, stealing away into the night on the Argo . Aeëtes gathered his men, including Medea's brother Apsyrtus, to pursue the Argo . When Apsyrtus drew close, Medea killed him, chopped him into pieces and threw them into the ocean to slow down her father's pursuit, and the Argonauts were able to get away.

They arrived in Corcyra (on the island of Corfu ), the land of the Phaeacians, where a Colchian flotilla found them. The Colchians demanded that Medea be surrendered to them. King Alcinoüs of the Phaeacians agreed, but only if Jason and Medea had not yet laid together. Jason quickly arranged their wedding and led Medea into a cave to consummate their relationship.

On their way to Crete , they were attacked by the bronze giant Talus, who threw boulders at them. Talus had a vein of ichor, the lifeblood of the gods, which was replenished through his ankle. Medea gave Talus the evil eye, causing Talus to knock his ankle against a rock and dislodge the plug that held in the ichor. Weakened, he fell off a cliff and into the sea, allowing Jason and the Argonauts to continue on their way.

The Death of King Pelias

After a voyage of four months, Jason returned to Iolcus to present the Golden Fleece to King Pelias. He learned that Pelias had killed his parents and his infant brother in his absence and swore to take revenge. Medea volunteered to kill Pelias herself, leaving Iolcus free for the Argonauts to take.

Medea disguised herself and her handmaidens as old crones and claimed that Artemis had come to Iolcus to bring it good fortune. They trampled through the streets of Iolcus, waking Pelias, who asked what Artemis required of him. Medea replied that Artemis wanted to reward his piety by making him young once again. Pelias was hesitant until Medea transformed herself back into a young woman and demonstrated how her magic could bring a dead, cut-up ram back to life as a young, feisty lamb. In reality, a young lamb was hidden in a hollow image of Artemis.

Medea enlisted the help of Pelias' daughters, who cut him into pieces and took them to Medea. Medea placed the pieces of Pelias into her cauldron and cooked them for several hours until they became a thick, gooey stew. She apologised to Pelias' daughters and admitted that she must have left out an ingredient. Jason and Medea left Iolcus for good, leaving the throne to Pelias' son Acastus.

In some versions of the myth, the murder of Pelias is carried out due to the wishes of the goddess Hera , who harboured a hatred for Pelias after he had failed to honour her. She decided that the beautiful but dangerous Medea would be the perfect person to bring about his end.

Medea's Revenge

Medea and Jason travelled to Corinth , where they lived happily for several years, having two sons together. Over time, Jason became dissatisfied with his relationship with Medea and decided to marry Glauce, the daughter of King Creon. An enraged Medea reminded Jason of his promise to her and plotted her revenge. She sent Jason and Glauce a wedding gift – a beautiful golden crown and a white robe. As soon as Glauce put them on, unquenchable flames leapt from her and consumed the whole wedding party, except for Jason.

However, Medea's revenge did not stop there. The best-known depictions of Medea's story state that she killed her and Jason's children.

Now hear what follows: I weep for what I must do; for then I'll kill my children. No one will give relief. When I've annihilated Jason's house, I'll leave this place, flee from the murder of my dear sons, that unholy act I've steeled myself for, friends. (Euripides, Medea , 791-797)

Medea fled Corinth on a chariot pulled by winged serpents after the horrific murder of her sons.

Medea in Exile

Medea first travelled to Thebes , where the Greek hero Heracles ( Hercules ) had promised to offer her refuge if Jason ever left her. She cured him of his madness after he killed his children. However, King Creon was king of the Thebans, and they resented having his murderer in their midst.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

She next travelled to Athens after King Aegeus promised her safety from her enemies. She married him and promised to cure his infertility. She bore Aegeus a son called Medus. Theseus , Aegeus' older son, arrived in Athens, and Medea knew he would take her child's place on the throne after Aegeus had died. She made Aegeus believe that Theseus had arrived in Athens as a spy and persuaded him to invite Theseus to a feast. Aegeus offered Theseus a goblet of wine, unaware that Medea had already poisoned it with wolfsbane. As Theseus raised the goblet to his lips, Aegeus noticed the serpents that were carved on Theseus' sword and knocked the goblet from his hand before he could drink from it.

Aegeus and Theseus reunited, and Aegeus publicly acknowledged him as his son. Theseus pursued Medea, but she hid under a magical cloud and left Athens with her son Medus. There is some debate over whether Medea persuaded Aegeus to send Theseus to face Poseidon 's white bull .

After Athens, Medea travelled to Italy , where she taught the Marrubians (people from Central Italy) snake charming and the healing arts. She briefly stopped in Thessaly , where she competed in a beauty competition against the Nereid Thetis . She married an Asian king whose name has been lost to time.

Learning that Aeëtes had been usurped from the throne in Colchis, Medea travelled there with her son Medus who killed her uncle Perses and helped to place Aeëtes back on the throne. Some traditions mention that she reconciled with Jason and lived with him in Corinth, but most maintain that Jason had grown old, weary, and depressed, wandering from one place to another. He sat down next to the decaying Argo , reminiscing when the prow suddenly fell and instantly killed him. Medea became immortal and lived in the Elysian Fields, where according to some stories, she married Achilles instead of Helen of Troy .

Medea As a Character

Over the years, there have been many studies and essays written about Medea and her place in Greek mythology. Even the ancient writers who wrote about her portrayed her in different ways. Euripides described her as a foreign woman finding her way in a strange land who had been betrayed by a cheating and cruel husband and took desperate and extreme measures to get her revenge. In Seneca 's (4 BCE to 65 CE) Medea , she is depicted as a ruthless sorceress who puts herself first. While Euripides has Medea kill her children off-stage, Seneca has her kill them on stage. Apollonius of Rhodes writes Medea as a vulnerable young woman who uses her magic to find her strength.

A recurring theme throughout the story of Medea is her power over life and death; she gives birth, she makes the old young again, and she kills. She embodies feminine anger at being abandoned by her lover and is a horrifying example of how far somebody will go when pushed too far.

It is no surprise that Medea's tragic, horrible story has inspired many works of art throughout history, beginning with Euripides' much-loved tragedy Medea , which was first performed in 431 BCE. She is featured in many books, TV shows and movies, including Geoffrey Chaucer 's (c. 1340s-1400) The Legend of Good Women , Jason and Medeia by John Gardner (1933-1982), the movie Jason and the Argonauts (1963), and the Italian movie Medea (1969) with the famous Greek soprano Maria Callas in the leading role. In more recent times, she has appeared as a character in the BBC TV series Atlantis (2013-2015) and in Rick Riordan's Percy Jackson and the Olympians book series.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Gagarin, Michael. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths[May 15, 2018] Graves, Robert. Viking, 2018.

- Hesiod & Theognis & Wender, Dorothea & Wender, Dorothea. Hesiod and Theognis . Penguin Classics, 1976.

- Medea - The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia Accessed 13 Jan 2023.

- Ovid & Raeburn, David & Feeney, Denis. Metamorphoses. Penguin Classics, 2004.

- Powell, Barry B. Classical Myth. Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Salisbury, Joyce E. Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World. ABC-CLIO, 2001.

- Sophocles & Aeschylus & Euripides & Lefkowitz, Mary & Romm, James. The Greek Plays. Modern Library, 2017.

- Woodard, Roger D. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

What is the main message of medea, why is medea a tragedy, why did medea turn evil, related content.

Medea (Play)

The Value of Family in Ancient Greek Literature

Golden Fleece

Jason & the Argonauts

Interview: Circe by Madeline Miller

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Independently published (2019) |

| , published by Dark Horse Books (2024) |

| , published by Dover Publications (1993) |

| , published by Atria Books (2024) |

| , published by Oxford University Press (2009) |

Cite This Work

Miate, L. (2023, January 16). Medea . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Medea/

Chicago Style

Miate, Liana. " Medea ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified January 16, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/Medea/.

Miate, Liana. " Medea ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 16 Jan 2023. Web. 15 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Liana Miate , published on 16 January 2023. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

1997.07.19, Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, Philosophy and Art

Joachim vogeler , louisana state university, [email protected].

As James Clauss reminds us in the preface, this excellent collection of twelve essays on Medea grew out of a panel organized by Sarah Johnston for the 1991 meeting of the American Philological Association in Chicago. An excellent introduction by Sarah Johnston outlines the scope of this collection and provides a superb and concise summary of the twelve essays on Medea. According to Johnston, “Medea was represented by the Greeks as a complex figure, fraught with conflicting desires and exhibiting an extraordinary range of behavior” (6). After sketching Medea’s mythic history from antiquity to the twentieth century and her reception in literary and art history, Johnston explores how Medea’s complexity continues to challenge our imaginations, confront our deepest feelings, and make us realize “that behind the delicate order we have sought to impose upon our world lurks chaos” (17). Without specifying to which theories in the field of psychology she is referring, Johnston elaborates on the dichotomy of self and other which she identifies as a common element in many of the essays. A complex Medea figure unites “the opposing concepts of self and other, as she veers between desirable and undesirable behavior, between Greek and foreigner; it also allows [authors and artists] to raise the disturbing possibility of otherness lurking within self —the possibility that the ‘normal’ carry within themselves the potential for abnormal behavior, that the boundaries expected to keep our world safe are not impermeable” (8). The juxtaposition of self and other serves as the theoretical background against which Johnston contrasts the twelve essays of this collection.

In part one, entitled “Mythic Representations,” the first four essays trace the possible origins and developments of Medea as mythological figure. In part two, entitled “Literary Portraits,” the next four essays focus on the Medea figure in Pindar, Euripides, Apollonius, and Ovid. Part three, “Under Philosophical Investigation,” examines the influence Medea had on ancient philosophers who dealt with the effects of passion on the human psyche. The fourth and final part, “Beyond the Euripidean Stage,” features the influence of Euripides’ Medea on ancient vase painting and the modern stage. The editors should also be commended for compiling a very useful and extensive bibliography of almost all works cited in the papers, an index locorum, and a general index. This collection of essays on Medea displays an amazing coherence for an endeavor of this kind, and paints a very coherent and complex picture of an influential mythological figure. Most authors in this collection also make illuminating cross-references to the essays of their fellow contributors. As with any well researched project on a literary theme, scholars as well as students ought to be very pleased with a most up-to-date publication such as this 1997 work. My only point of criticism would be to note that a project taking such a comprehensive approach should be familiar with the work of Jacques Lacan, and that it would have been helpful if the editors had included a psychoanalytic investigation of Medea’s passion. Nonetheless, I expect the present volume to become a standard textbook and an obvious starting point for any students of the Medea figure. A brief survey of the twelve essays will demonstrate the scope and the quality of this project.

Fritz Graf, known for his introduction to Greek Mythology (1993), opens part one of this collection on “Mythic Representations” with an essay entitled “Medea, the Enchantress from Afar: Remarks on a Well-Known Myth.” Distinguishing between “vertical tradition” (different versions of the same mythic episode, developed over the course of centuries) and “horizontal tradition” (different versions of the same mythic episode within the same time frame), Graf furnishes an overview of Medea’s episodes in Colchis, Iolcus, Corinth, Athens, and Persia. After analyzing the themes and variations within both of these traditions and noting the consistencies and tensions between them, Graf identifies two unifying elements that tie together all the stories about Medea: her foreigness and her initiatory role. “[S]he is a foreigner, who lives outside of the known world or comes to a city from outside; each time she enters a city where she dwells, she comes from a distant place, and when she leaves the city, she again goes to a distant place” (38). Medea’s representation as the other corresponds with Johnston’s introductory remarks that, as “a geographical and cultural stranger … repeatedly exiled within Greece,” Medea implicitly demonstrates how the outsider, the other, is a threat to the inside, to the self” (14). In Graf’s second unifying theme, he identifies Medea as being “connected with a whole line of narratives that clearly are associated with initiation rites” (42). We can understand Medea as “initiatrix” when she helps Jason to overcome the dangers he must undergo in his “initiation ritual” to acquire the fleece and claim the throne back home.

In “Corinthian Medea and the Cult of Hera Akraia,” Sarah Johnston argues that no single author invented the image of the murderous mother and that fifth-century authors inherited an infanticidal Medea from the mythical tradition. This mythical figure may have been an earlier goddess of the Corinthians who “evolved out of a paradigm found in the folk beliefs of Greece and many other Mediterranean cultures—the reproductive demon, who persecuted pregnant women and young children” (14). According to Johnston, the paradigm of the reproductive demon “is likely to have been associated with the Corinthian cult of Hera Akraia” (45). As a mother who lost her children because of Hera’s refusal to protect them and help nurture them to maturity, Corinthian Medea originally emblematized the results of Hera’s neglect and/or anger (64). According to Johnston, this loss would have caused Medea to become a reproductive demon that killed other mothers’ children. At the end of Johnston’s stimulating essay, however, she has to admit that the specific reasons why the Colchian and Corinthian Medea were joined together are beyond our secure recovery (67). In an excellent essay on “Medea as Foundation-Heroine,” Nita Krevans explores Medea’s role as founder of cities. With foundations in antiquity centering primarily on male founders, the traditional roles for heroines in myth include “that of the eponymous nymph, who brings to life the metaphor of woman-as-landscape” (72), “that of the dynastic heroine, mother of a founder or of a line of local rulers” (73), and that of “the missing girl … sought by a male kinsman (or kinsmen)” (74). Often foundations are associated with a mother’s heroic child, leaving little more than a footnote for heroines. Although some foundation stories portray Medea in these traditional roles, other appearances “form a striking exception when seen against this backdrop…. [F]or every version in which she seems to follow the normal scheme, there is a variant that portrays her as a defiant anomaly” (75). With the foundation of Tomi, for example, which is associated with Apsyrtus, “we arrive at a complete inversion of the ‘kidnapped heroine’ motif” (78). Medea is the kidnapping sister, not the victim. The inversion of the gender roles sees the female as kidnapper and the male as helpless victim. Likewise, (female) Medea appears as a powerful prophet of divine status who instructs future (male) settlers about the location and destiny of their colony (78-79). The presentation of Medea in powerful, masculine roles is virtually incompatible with female fertility (80). Although Medea’s prophetic powers and divine attributes challenge the traditional boundaries between male and female, most foundation tales focus on Medea’s “extraordinary capacity for destruction” which make her “a heroine not of foundation but of annihilation” (82). Jan Bremmer’s essay asks: “Why Did Medea Kill Her Brother Apsyrtus?” rather than any other family member. After examining the specifics of this “treacherous, sacrilegious, and brutal murder” (88) as it has been described in various ancient sources, Bremmer conducts a detailed comparison of Greek sibling relationships. He concludes that brother-brother relationships and sister-sister relationships were not as close as brother-sister relationships, and it was the opposite-sex relationships on which the Greeks placed the greatest importance. In ancient (and in contemporary) Greece, “brothers [are] supposed to guard the honor, and in particular the sexual honor, of their sisters” (95). Compared with same sex sibling relationships, “brother-sister conflicts are very rare in Greek Myth” (96) and the “close contact between sisters and brothers must have continued even after the sister’s marriage” (95). “[T]he brother was responsible for the sister, and she was dependent upon him” (100). Medea’s murder of her brother Apsyrtus had such a great impact because “Medea not only committed the heinous act of spilling family blood, she also permanently severed all ties to her natal home and the role that it would normally play in her adult life. Through Apsyrtus’ murder, she simultaneously declared her independence from her family and forfeited her right to any protection from it…. There was only one way for Medea to go, then: she had to follow Jason and never look back” (100). Bremmer concludes his convincing analysis with the assumption that Medea’s fratricide elicited great feelings of horror from the Greek audience—because we hardly find any artistic representations of Apsyrtus’ murder on Greek vases (100). In “Medea as Muse: Pindar’s Pythian 4,” Dolores M. O’Higgins suggests that Pindar presents Medea as a muselike figure. In archaic Greece, people distrusted human and divine females (103-104). “For the Greeks all women were no less than a race apart. Medea most fully exemplifies the potential disloyalty present in all wives, living as necessary but suspect aliens in their husbands’ houses” (122). Foreign, female intelligence—both Medea’s and that of the Muse—had to be appropriated before the male hero, Jason, or the male poet, Pindar, could use it to his own advantage (107-108). “Traditionally, the process of song making,” O’Higgins explains, “was a joint effort…. The human bard requires a song of the Muses” (108). Pindar relied on female Muses, to create his song, and at the same time, the Muses had the capacity to dangerously intoxicate or even paralyze the poet or his audience (110). For a fuller understanding of Pythian 4, it is important to realize that Pindar also presents Medea as powerful, prophetic female, “a Muse of sorts” (114). Pindar changes the traditional parameters of the poet “as the passive vessel for information” (117), and he appropriates his Muse by basically telling her what to sing about. Pindar also appropriates Medea, the former Colchian “Muse,” who first immobilized Jason’s opponents, but then has herself fallen victim to the poetic skills of Jason—or Pindar, as O’Higgins suggests (123). “Jason ultimately may have failed in harnessing the supernatural abilities of Medea, but Pindar has not; he tames the dangerous Muse,” O’Higgins concludes (126). In “Becoming Medea: Assimilation in Euripides,” Deborah Boedeker observes that the Medea figure was not yet firmly established when Euripides composed his play. “Besides the deliberate infanticide, alternative Medeas were still possible” (127), and even within a single episode, an author was able to and ultimately had to make choices in motivating and designing the story line. Boedeker suggests that Euripides gives his protagonist her overpowering presence and canonical status by employing poetic mechanisms, namely a series of similes and metaphors, to categorize his heroine initially. During the course of the play, “Medea is gradually dissociated from such apparently obvious definitions of what she is … [and] subtly assimilated to several figures in her own story, such as Aphrodite, Jason, and the princess” (128). Medea’s implicit assimilation to other figures by mutual resemblances in diction and action gives her “an almost unbearably focused power and allows her action a certain claim to reciprocal justice” (148). “She destroys her enemies by becoming more like them, ruins them for being too much like herself. Ultimately Euripides’ Medea expands to the point where she obliterates the other characters in her myth, fully transcending—and eradicating—her own once-limited identity as woman, wife, mother, mortal” (148). Medea’s self has been consumed by the other, Johnston concludes in her introduction (11), the former victim has turned victimizer—a development for which we can both pity and fear Medea. In “Conquest of the Mephistophelian Nausicaa: Medea’s Role in Apollonius’ Redefinition of the Epic Hero,” James J. Clauss argues persuasively that Apollonius assigns Jason to the traditional role of hero, and that Medea usurps the role of “helper-maiden,” contributing to the Argonautic expedition by helping him to complete the contest (149-150). Jason, however, is not an independent hero like Heracles, who completes his contests by himself, but “thoroughly dependent on the assistance of others” (151). Jason’s brand of leadership and heroism finds its expression in “his ability to make deals with foreigners” (155). Comparing Jason and Medea to Odysseus and Nausicaa, Clauss demonstrates that Jason’s contest is not of a military kind; Medea represents his real contest and she is completely charmed by Jason’s beauty and his diplomatic skills: “To conquer Medea is to win the fleece, the opposite of the usual folktale motif, which has the young hero perform the contest to win the bride” (167). The often clueless and all too ordinary Jason ultimately succeeds as he secures the golden fleece but Apollonius’ heroism is of a different kind, with a Jason relying heavily on Medea as a powerful and indispensable “helper-maiden” (175). The implicit comparison with Nausicaa reveals Medea’s otherness who “possesses the ability to create a Heracles or destroy a man of bronze” (176). Carole E. Newlands takes a comparative approach in analyzing the dissonant structure of the full Medea story in her brilliant essay “The Metamorphosis of Ovid’s Medea.” While his Medea is initially portrayed sympathetically as a young girl whose irrational passion drives her to help Jason, in the second part of Ovid’s narrative (7.7-424), Medea appears exclusively as a witch who has lost her human characteristics. After sketching Medea’s story of the young maiden turning murderess, Newlands compares the bipartite structure of Ovid’s narrative with other marriage tales in Metamorphoses 6, 7, and 8. By juxtaposing the myths of Procne, Philomela, and Tereus (6.424-676), Scylla and Minos (8.1-151), Procris and Cephalus (7.694-862), and Boreas and Orthyia (6.677-721) with the myth of Medea, Ovid approaches urgent moral issues and offers us varying studies of the female as victim and criminal without making moral judgments. “By splitting the Medea of the Metamorphoses into two incompatible types, Ovid suggests the difficulties and inconsistencies in the rewriting of the tradition (191). … But Ovid does not explain the reason for Medea’s transformation into a sorceress and semidivine, evil being” (192), he just offers us refracted images. “Ovid adds complexity to the story of Medea by juxtaposing it with stories that are simultaneously similar and different,” Newlands concludes (207). She continues by suggesting that “Ovid’s marriage group of tales illustrates how society both denies a woman power and rejects her when she uses it” (208). By presenting two very different Medeas, Ovid creates an open-ended story that leaves the ultimate judgment to the reader. John M. Dillon’s brief essay “Medea Among Philosophers” raises many questions for the reader—as Johnston acknowledges in her introduction (10)—without providing answers. Focusing on Medea 1078-1080, Dillon shows how Euripides’ text is employed in philosophical circles to buttress the argument of different philosophical schools (215). Galen and Platonist philosophers would view Medea’s subjugation of her reason to her passion as an argument that the human tripartite soul possesses an irrational part, whereas Chrysippus and the Stoics use Medea to argue for the unity of the soul (212). Medea remains “the paradigmatic example of a disordered soul” for ancient philosophers (218), Dillon concludes. Regrettably, none of the contributors to this collection employs a psychoanalytic approach in discussing Medea’s passion and the state of her soul. “Serpents in the Soul: A Reading of Seneca’s Medea ” is an abbreviated version of chapter 12 of Martha C. Nussbaum’s book The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994). In her fascinating essay, Nussbaum argues that as an author Seneca is “an elusive, complex, and contradictory figure, a figure deeply committed both to Stoicism and to the world, both to purity and to the erotic” (246). While “Seneca’s Medea provides a clear expression of the strongest and least circular of the Stoic arguments against passion” (223), the play—and tragedy in general—are “profoundly committed to the values that Plato and Stoicism wish to reject” (247). Medea’s problem is not her love per se but her inappropriate, immoderate love for Jason. However, as Seneca tells us, there is “no erotic passion that reliably stops short of its own excess” (221). He questions the Aristotelian notion “that we can have passionate love in our lives and still be people of virtue and appropriate action” (220). Seneca argues that passionate love creates “a life of continued gaping openness to violation, a life in which pieces of the self are groping out into the world and pieces of the world are dangerously making their way into the insides of the self” (222). Extrapolating from this argument, Seneca’s Medea claims that love may even include the wish to kill. According to Nussbaum, it is not surprising that love, anger, and grief lie close to one another in the heart; these are all judgments, differing only in the precise content of the proposition, that ascribe so much importance to one unstable external being (228). Echoing Lacanian ideas, Nussbaum writes: “Desire is the beginning of the death of the self” (232). Two minor images, that of the bridle and the wave, and a central image, that of the snake, recur throughout Seneca’s play, exemplifying Medea’s passionate love. While love challenges the virtue of Stoic morality, either way of living, a life of love or a life of morality, seems to be imperfect. In her conclusion, Nussbaum returns to Seneca’s concept of mercy as a possible source of gentleness to both self and other, even when wrongdoing has been found—until rage gives way to understanding (248). Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood takes our heroine beyond the stage and investigates the dramatic and iconographical explorations of the Medea figure. In “Medea at a Shifting Distance: Images and Euripidean Tragedy,” Sourvinou-Inwood demonstrates how Euripides’ Athenian audience would perceive Medea’s character through a series of shifting relationships. Euripides constructed Medea’s character in the course of the tragedy using the three schemata of “normal woman,” “good woman” and bad woman” (254). These schemata were important crystallizations of the ancient assumptions that helped Euripides direct audience response (255). Euripides created the Medea figure by deploying a series of what Sourvinou-Inwood calls “zooming devices” and “distancing devices.” Noticing a difference in representations of Medea in Greek dress and oriental dress, Sourvinou-Inwood suggests that Medea was wearing Greek dress throughout Euripides’ play but oriental dress when she appeared in the chariot after murdering her children (289-290). The oriental dress would have enhanced the effect of distancing Medea from the Greek “good” or “normal” woman. “The change in her costume is marked by Jason’s claim, after Medea has appeared in the chariot of the Sun at [ Medea ] 1339-40, that no Greek woman would have dared to do the dreadful thing she did” (291). The zooming and distancing of Medea, the alteration of Medea in oriental dress and Medea in Greek dress allows the exploration of male fears concerning women and deconstructs the oppositional relationship between the “good Greek male self” and the “bad oriental female other” (294-296). In the end, through a series of shifting relationships, Euripides’ Medea allows the more complex perception that “the barbarian is not so different from the self” (296). The final essay in this fine collection offers a look at “Medea as Politician and Diva: Riding the Dragon into the Future.” And indeed, characterizing Medea as a revolutionary symbol, as the exploited other who may fight back, Marianne McDonald not only summarizes some of the other contributors’ main points in the closing essay but also provides a brief summary of the literary history of the various Medea dramatizations taking the reader into the twentieth century and beyond. This essay, which any scholar in comparative literature will appreciate highly, may also stimulate classicists to draw on the rich reception of the Medea theme in their teaching of the myth. McDonald contrasts the 1988 Medea play by Irish playwright Brendan Kennelly with an unpublished opera by Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis which was performed in Bilbao, Spain in 1991 and in Athens in 1993. Kennelly deals with questions of imperialism, the exploitation of women by men, Ireland by England, and he shows us a victimized Medea who victoriously fights back. Theodorakis, in contrast, emphasizes the emotional element in Medea over the rational, and “evokes Euripides’ interpretative genius through the symbolic associations of the music” (317). McDonald views Theodorakis’ opera “as another splendid example of how a modern work can elucidate this ancient text” (314). If nothing else, McDonald’s presentation raises a certain curiosity to explore these two and other modern works dealing with the Medea theme. “The twentieth century is especially rich in reworkings of this myth” (297), she claims, and the publication of the most recent Medea novel by German writer Christa Wolf, Medea: Stimmen (Munich: Luchterhand Literaturverlag, 1996) serves as another good example to support her argument. “Both Kennelly and Theodorakis,” McDonald concludes this remarkable collection of essays, “bring Euripides into modern times and into modern nations. In their own ways, they are true to Euripides and aim at the heart” (323).

Join Now to View Premium Content

GradeSaver provides access to 2362 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 11008 literature essays, 2769 sample college application essays, 926 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Analysis of Medea as a Tragic Character Michael Kliegl

What lends tragic literature its proximity to human nature is that the border between being a tragic villain and a tragic hero is extremely thin.

A question that this statement will certainly bring up is whether there is such a thing as a hero or a villain or whether these terms are defined by the ideals of the society. Tragedies such as Macbeth or Oedipus Rex feature a character with heroic traits who falls victim to a personal flaw or an outside circumstance which finally pushes that character into becoming a villain. Macbeth's greed and hunger for power are the causes for his descent into madness and villainy, and Oedipus falls victim to fate because of his pride and finally ends up tearing his eyes out and running into exile. A similar progression can also be followed in Euripides' Medea. Medea is a play about a woman, Medea, who is betrayed by her husband, Jason, and expelled from the city. In an outburst of treacherous but cleverly planned rage, she avenges herself by first poisoning Jason's new fiancé and then killing her own children, thus leaving Jason without distinction. Though Medea possesses certain traits of a victim and a heroine, it is impossible to identify her character as solely one of these. In...

GradeSaver provides access to 2312 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 10989 literature essays, 2751 sample college application essays, 911 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Already a member? Log in

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

English Works

Revision: Is Medea a hero or a villain?

One of your most important tasks is to work out of Medea is a heroine or tyrant and the tension between passion and reason.

- Euripides suggests that Medea also has a legitimate grievance and so is not solely responsible for the tragedy. To the extent that Medea presents her grievances on behalf of “we women”, and to the extent that she criticises her unjust treatment, Euripides encourages the audience to sympathise with her desperate plight.

- Euripides also suggests that she has been wilfully treated by Jason : in the 5 th century patriarchal society she has few rights as soon-to-be divorced woman and this adds to her grievances.

- When the chorus describe her as a “child killer”, Euripides suggests that she has overstepped the boundaries of justice.

- Euripides presents Jason as a cold-hearted husband who prides himself on being able to negotiate the tempestuous whims of others. Euripides suggests that one of his biggest errors of judgement is to misunderstand or downplay the depth of Medea’s passion and grievances. Accordingly, the playwright suggests that Jason is partly to blame and contributes to the tragedy. (Whilst he appears level-headed and “clever”, “superior” in his ability to think, he underestimates Medea’s capacity to dissemble.

- Euripides shows the damage that can occur owing to extremes of emotion – both love and hatred. In particular, the playwright suggests that hatred festers and leads to shameful excuses on behalf of Medea who condones the suffering she inflicts on others. As the Nurse laments, tragedy arises from sorrow, which “is the real cause of deaths and disasters and families destroyed”.

- Euripides also suggests that Jason’s phlegmatic and insensitive streak fails to anticipate the danger that lurks within. Only a very extreme action, it seems, can penetrate his barriers.

Views and values:

On the one hand, Medea is depicted as a heroic figure who passionately defends the rights of “we women”

- Victim and passionate fight for justice: Medea fights against the injustice on behalf of all women, and from the outset, Lamentably, concedes that “there is no justice in the world’s censorious eyes.”.

- Medea draws attention to the desperate fate of “we women” who are “the most wretched”. “When for the extravagant sum, we have bought a husband, we must then accept him as possessor of our body.”

- Her passionate exclamations (“what misery. What wretchedness!”) and desperate questions (“Am I not wronged?”) to the Nurse and the tutor lay bare her incredible despair and anguish. ND. At first, the audience only hears Medea’s incredible anguish from the domestic space. However, she tries to temper and restrain her personal anguish and, as she enters the male public place, presents a logical and reasoned argument on behalf of “we women”.

- ND As the “Women of Corinth”, Euripides depicts the chorus as a group of fair-minded representatives of the community who support Medea’s campaign for justice, and who, acting as one body, “suffer” with the “house” of Jason. “My own heart suffers too When Jason’s house is suffering”. They agree to abide by Medea’s pleas to “say nothing”, which makes them complicit.

- Sacrifices: She has made significant sacrifices in helping Jason secure the Golden Fleece. The Golden Fleece also represents tradition and wealth, family and security. By helping Jason steal the Golden Fleece, Medea compromises her own family’s tradition and undermines family values.

- Medea incited violence among family members and renounced her homeland. (She killed her brother and incited violence against Peleas. As the Nurse reminds us, in the prologue, “When Peleas’ daughters, at her instance, killed their father”.) “I was taken as plunder from a land”. She has no one “of my own blood to turn to in this extremity”.

- ND The chorus also states, the life of a “stateless refugee”, which is “intolerable” and “desperate” is the “most pitiful of all griefs”. “Death is better.” “Of all pains and hardships none is worse Than to be deprived of your native land.”

- Euripides ensures that the audience views Medea sympathetically. The chorus alludes to a new time when the “female sex is honoured”. Euripides suggests that the “male poets of past ages” who will “go out of fashion”; such poets “never bestowed the lyric inspiration/Through female understanding”.

Medea can be just as ruthless and manipulative as Jason. She deceives both Creon and Jason

The sharp-sighted Medea deceives both Jason and Creon’s family for her own purposes: “Do you think I would ever have fawned so on this man, except to gain my purpose, carry out my schemes?”.

- Medea outwits King Creon and begs for an extra day, which enables her to fulfil her hideous scheme. (Later, she will extract a promise from Aegeus because of his desire for children.)

- Medea appeals to Creon’s paternal feelings realising that homeland and children are critical to a man’s sense of self, his status and his vanity. Creon yields, although with considerable misgivings. He fears Medea and knows that she has considerable skills. (she can be clever and has significant “magic skills”)

- Medea deceives Jason by acknowledging his desire for an obedient and repentant wife. Her false declaration of submission to Jason, her confession that she was a foolish emotional woman, lures him to his doom. “I talked things over with myself, she tells him, “and reproached myself bitterly”. “Why do I act like a mad woman? … What you did was best for me… I confess I was full of bad thoughts”. Medea knows that her best way to conceal her motives and implement her plan is to pretend to be submissive. It works. Jason is hoodwinked: he thinks that she has changed and become “sensible”, that is adopts Jason’s views and values.

MEDEA AS TYRANT PARAGRAPH

The chorus suggests that Medea crosses the line by killing her children and turns herself into a despicable “child-killer”. By killing the children, Medea’s righteous cause tips into cold-blooded revenge Euripides criticises her motives as she becomes obsessed with sparing herself the scorn of her enemies.

- Likewise, her courage turns into stubborn ruthlessness.

- Clearly, her ploy to use the children as tools in her revenge agenda is shameful and horrifying. She betrays her maternal instincts in order to hurt Jason in the most agonising way possible.

- ND: During her two key soliloquies, during which she steels herself to commit the double murder, she reveals her personal struggle with her conscience. Euripides depicts her warring selves, as she consider the deed from the perspective of the third person: “Oh my heart, don’t don’t do it! Oh miserable heart. Let them be! Spare your children”.

- Medea also reveals her acute awareness: “I understand/The Horror of what I am going to do; but anger/The spring of all life’s horror, masters my resolve”.

- She seeks to justify her actions through recourse to her divine links but the audience must question whether she is simply trying to conceal or justify her heinous/hideous/shocking actions.

- Already at the beginning of the play, E draws attention to her murderess acts that have been committed out of a sense of passion and love, fortune and fame. To this end, she exploits her children to harm Jason in the most agonising way possible, which in Greek society was through the children. “…” (aware that it will hurt both Jason and Creon at their most vulnerable)

- She is dominated by a sense of honour and increasingly motivated by the need to spare herself the enemy’s scorn and derision. She fears, more than anything, the mockery of her enemies. “The laughter of my enemies I will not endure.”

Conflict: tension : between positive/negative passion (reason versus passion)

Literary devices: Medea is depicted as someone who is aware of the full horror of the deed. “ I understand the horror of what I am going to do.” (“I am well aware how terrible a crime I am about to commit but passion is master of my reason”) and this leads to a great deal of tension. During key soliloquys prior to the murder, Euripides depicts Medea’s agony as she contemplates the war caused by her love for her children and her resolve to murder her sons (the nurse says, “She hates her sons”) At one stage, Medea, as the motherly “I” considers the deed from the perspective of the third person and argues with the revengeful persona “you”: “Oh my heart, don’t don’t do it! Oh, miserable heart, Let them be! Spare your children! We’ll all live together, Safely in Athens; and they will make you happy … No.” (49-50)

She is desperate at the thought of killing her children (“My misery is my own heart, which will not relent All was for nothing – these years of rearing you – my aching weariness; my wild pains”) “Arm yourself, my heart: the thing That you must do is fearful, yet inevitable. Why wait then? My accursed hand, come take the sword; Take it and forward to your frontier of despair.” (55)

The emotional/irrational Jason : his problems

Euripides characterises Jason as a cold-hearted and condescending husband, who callously betrays Medea in order to gain royal favours. He consistently belittles and dismisses Medea’s grievances as a case of sexual jealousy. “My children; now out of mere sexual jealousy/You murder them”.

Jason overlooks the role that Medea played in helping him gain the Golden Fleece. He has the audacity to level at Medea the charge of traitor: “When I brought you from your palace in a land of savages into a Greek home – you, a living curse, already A traitor both to your father and your native land”, and conveniently overlooks the fact that she sacrificed her honour for his reward. He believes that he secured the Golden Fleece without her help.

He continues the patriarchal system that gives priority to male choices and behaviour. He later agrees that Glauce ought to listen to him: “If my wife values me at all she will yield to me (965/ 46). “If I count for anything in my wife’s eyes, she will prefer me to wealth, I have no doubt” (75)

Whereas the Nurse is sympathetic towards Medea because of her grief, Jason refers to “seamanship” imagery to suggest that he must navigate and weather Medea’s emotional storm. “I’ll furl all but an inch Of sail and ride it out.”

He unleashes insults at Medea and labels her the “polluted fiend, child-murderer”; “The curse of children’s blood be on you! Avenging justice blast your being!” He calls her a “Tuscan Scylla” “but more savage”. (58).

ALSO THINK ABOUT:

Divine links and support:

Medea seeks to present her scheme as one that has divine support, especially given the difficult task of securing the Golden Fleece for Jason. She defends her actions and her decision to kill the children on the grounds that she has God’s help and that “to such a life glory belongs”. “With God’s help I know will punish (Jason)”. (802- 42) She begs the Gods to help, “O Zeus O Justice” (767-40). She uses her magical skills to help solve Aegeus’ fertility problem and so arranges convenient exile. (She also later suggests, (1015/77 (1015/48). “the Gods and my own evil-hearted plots, have led to this”. (this is what the gods and I devised, I and my foolish heart”. Is this a selfish motive, or one that is selflessly protecting the honour of the Gods?

After her deed, Medea appears in the chariot “drawn by dragons, with the bodies of the two children beside her”. (58 – 1316) We learn that the “chariot moves out of sight” (1410, 60) as the chorus talks about the “unexpected” that “God makes possible”. Euripides does suggest that there is perhaps a divine element in Medea’s actions. Is there a higher cause, that is perhaps beyond human understanding? Or does he critique people’s all-too-quick tendency to find a scapegoat for our worst impulses?

The depth of Medea’s love is evident in the fact that she has sacrificed so much for Jason. The intertextual references to the Golden Fleece, impress upon the audience the sacrificial nature of Medea’s character and the depth of her passion for this Greek outsider who ventured to the “barbaric” lands to seek redress for his own family background … . She was “mad with love” for Jason. She has a very deep affection which is why she is so angry at his betrayal. She admits, too, that he would not have succeeded in gaining the Fleece without her support and magical skills. “it was I, Who killed it (the golden fleece) and so lit the torch of your success. I willingly deceived my father; left my home; With you I came to Iolcus by Mount Pelion, Showing much love and little wisdom. There I put King Pelias to the most horrible of deaths By his own daughter’s hands, and ruined his whole house.”

Extreme Passion

Medea is motivated by her excessive passion for her husband, Jason that turns to excessive hatred upon his betrayal. In many ways, these two emotions intertwine to give a complex portrayal of a woman who is deeply wounded because Jason believes that Glauce will become a more advantageous bride.

Furiously angry, and paralysed by grief, “(she lies collapsed in agony”), Medea commits the “hideous crime” against the royal house and gloats in both Creon’s and his daughter’s death, telling the Messenger, “you’ll give me double pleasure if their death was horrible”. Her “passionate indignation” at Jason’s betrayal leads to the double murder of her children as well, as she is determined to inflict the same amount of pain and grief upon her treacherous husband. She admits that she understands the “full horror” of what she is about to do , but concedes that “anger masters my resolve”. Euripides uses the mythological background of the golden fleece to highlight Medea’s former passion, the violence she has incited against her family, and her incredible sacrifice as she pursues Jason to Corinth to become the “stateless refugee”.

Euripides uses the mythological background of the golden fleece to draw attention to Medea’s strong passion for Jason, which leads to incredible sacrifice as she becomes the “stateless refugee”. Significantly, Euripides constructs the opening scene so that the audience can hear Medea’s wailing voice offstage, because of the news that he has chosen the “royal bed”. Euripides depicts Medea as the beleaguered heroine who is paralysed by grief (‘she lies collapsed in agony”) because of her loss.

She admits that understands the “full horror” of what she is about to do , but “anger masters my resolve” . The double tragedy confirms the Nurse’s warning right from the start, to “ “watch out for that savage nature…stubborn will and unforgiving nature” that seeks to inflict upon others the humiliation and anger she feels so deeply. In this regard, Euripides shows the damage that can occur owing to extremes of emotion – both love and hatred. In particular, the playwright suggests that hatred festers and leads to shameful excuses on behalf of Medea who condones the suffering she inflicts on others. As the Nurse laments, tragedy arises from sorrow, which “is the real cause of deaths and disasters and families destroyed”.

- See some essay-writing tips on Medea

- Return to Medea: Study Page

- Return to Summary Notes on Medea

Ono što vodi muškarce u sljedećoj krizi i želi, kao u najavi, mijenja “suprugu od 40 godina od dvije do 20”, izvor informacija razumljivo. Ali zašto mladi daju takve prijedloge? Koje prednosti i nedostaci, odvajajući se naboranom rukom, srcem, radeći više poput švicarskog sata i čvrstog računa u banci, čitati o ženi.ru.

For Sponsorship and Other Enquiries

Keep in touch.

Essay Service Examples Literature Medea

Is Medea A Tragic Hero?

- Proper editing and formatting

- Free revision, title page, and bibliography

- Flexible prices and money-back guarantee

Our writers will provide you with an essay sample written from scratch: any topic, any deadline, any instructions.

Cite this paper

Related essay topics.

Get your paper done in as fast as 3 hours, 24/7.

Related articles

Most popular essays

In Euripides’ ancient Greek tragedy ‘Medea,’ he explores how women are disadvantaged in society in...

- Perspective

Body-image is a multidimensional, subjective and dynamic concept that encompasses a person’s...

Traditions for centuries have defined gender roles in societies. Some critics today may declare...

Revenge is a significant theme in most Greek tragedies as it is perceived as a means of justice by...

Body image is the perception that a person has of their physical self and the thoughts and...

- Gender Roles

Female characters in gothic texts both challenge and reinforce prevailing standards of gender...

- Literary Criticism

The catastrophic Greek tragedy, “Medea” deals with the maltreatment faced by the titular character...

Euripedes’ play opens in Conrith with Medea in a state of conflict. Not only does her husband...

Love continues through Euripides’s Medea. Euripides’s Medea is an ancient Greek tragedy based on...

Join our 150k of happy users

- Get original paper written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

Fair Use Policy

EduBirdie considers academic integrity to be the essential part of the learning process and does not support any violation of the academic standards. Should you have any questions regarding our Fair Use Policy or become aware of any violations, please do not hesitate to contact us via [email protected].

We are here 24/7 to write your paper in as fast as 3 hours.

Provide your email, and we'll send you this sample!

By providing your email, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy .

Say goodbye to copy-pasting!

Get custom-crafted papers for you.

Enter your email, and we'll promptly send you the full essay. No need to copy piece by piece. It's in your inbox!

Is Medea a Tragic Hero?

This essay will explore whether the character Medea from Euripides’ play can be considered a tragic hero. It will analyze the classical definition of a tragic hero and assess how Medea fits into this framework. The discussion will focus on Medea’s noble qualities, her tragic flaw, and the consequences of her actions. The piece will also examine the play’s themes of revenge, justice, and the role of women in Ancient Greek society to understand Medea’s complex character and her tragic trajectory. On PapersOwl, there’s also a selection of free essay templates associated with Hero.

How it works

The story of Medea has is often debated by modern scholars, to which they are trying to assign who is the true tragic hero in the story. Greek audiences used to conclude that Jason was the tragic hero. However, now it is argued that Madea better demonstrates the real tragic hero in the story.

Is Medea a Tragedy?

The term hero is obtained from a Greek word that means a person who faces misfortune, or displays courage in the face of danger.