- Global Issues

- Community Projects

- Creative Writing

- Storytelling

- Problem-Solving Method

- Real World Issues

- Future Scenarios

- Authentic Assessments

- 5Cs of Learning

- Youth Protection

- DEIB Commitment

- International Conference

- Find FPS Near Me

- Partner With Us

Food Security

How might food security issues of availability, access, and affordability essential for living a healthy life impact society in the future?

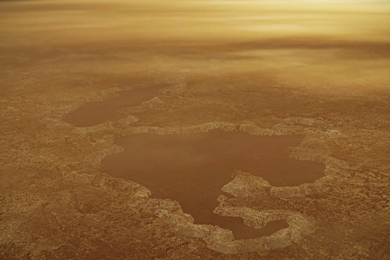

Rising Sea Levels

How might we address the impact of rising sea levels on coastlines, industries, and people in the future?

Agricultural Industry

How might the agricultural industry adapt to the needs of feeding a growing world population in the future?

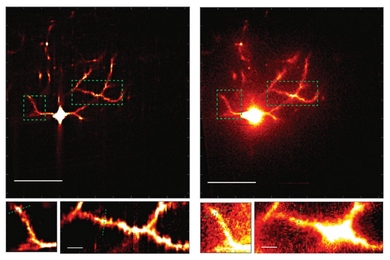

Nanotechnology

How might the use of nanotechnology in medicine, healthcare, and other industries affect humanity in the future?

The full list of 50+ years of solving real world challenges

See a comprehensive list of all the Future Problem Solving competition topics from 1974 to today.

Air Quality

How will the quality of air, a globally shared resource essential for human health and prosperity, impact us in the future?

Changing with the times: environmental sustainability issues

See how Future Problem Solving environment topic-related challenges evolved through the decades.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

How will the emerging uses of artificial intelligence (AI) impact how we work, live, play, and learn in the future?

Have a topic idea?

Featured articles.

Future Problem Solving Students – A Five Year Study

A comparison of reading and mathematics performance between students participating in a future problem solving program and nonparticipants.

Data from the The Minnesota Comprehensive Assessment (MCA) was collected by Grandview Middle School and provided to Scholastic Testing Service, Inc. for statistical analysis.

Findings reported by Scholastic Testing Service, Inc. Performance data on the MCA was collected from 2010-2014 for students in grade 6 at Grandview Middle School in Mound, MN (Westonka Public School District). Students were identified as either FPS: students participating in a Future Problem Solving program, or Non-FPS: students not participating in the program. Summary statistics using Reading and Mathematics Scaled Scores were developed for each group of students by year and across years. To determine if the mean scores across the years were significantly different, t-tests were used. A Cohen’s d test was then performed to measure the effect of the size of the found differences.

In all cases, students participating in the Future Problem Solving Program performed significantly higher on the MCA in both areas of Mathematics and Reading.

Effects of Group Training in Problem-Solving Style on Future Problem-Solving Performance

The journal of creative behavior (jcb) of the creative education foundation.

Seventy-five participants from one suburban high school formed 21 teams with 3–4 members each for Future Problem Solving (FPS). Students were selected to participate in either the regular FPS or an enhanced FPS, where multiple group training activities grounded in problem-solving style were incorporated into a 9-week treatment period.

An ANCOVA procedure was used to examine the difference in team responses to a creative problem-solving scenario for members of each group, after accounting for initial differences in creative problem-solving performance, years of experience in FPS, and creative thinking related to fluency, flexibility, and originality. The ANCOVA resulted in a significant difference in problem-solving performance in favor of students in the treatment group (F(1, 57) = 8.21, p = .006, partial eta squared = .126, medium), while there were no significant differences in years of experience or creativity scores. This result led researchers to conclude that students in both groups had equivalent creative ability and that participation in the group activities emphasizing problem-solving style significantly contributed to creative performance.

In the comparison group, a total of 47% had scores that qualified for entry to the state competition. In contrast, 89% of the students in the treatment group had scores that qualified them for the state bowl. None of the teams from the comparison group qualified for the international competition, while two teams from the treatment group were selected, with one earning sixth place.

The results of this study suggest that problem-solving performance by team members can be improved through direct instruction in problem-solving style, particularly when there is a focus on group dynamics.

The Journal of Creative Behavior, Vol. 0, Iss. 0, pp. 1–12 © 2017 by the Creative Education Foundation, Inc. DOI: 10.1002/jocb.176

Future Problem Solving Program International—Second Generation Study

“how important was future problem solving in the development of your following skill sets”.

In 2011, a team of researchers from the University of Virginia submitted a report titled “Future Problem Solving Program International—Second Generation Study.” (Callahan, Alimin, & Uguz, 2012). The study, based on a survey, collected data from over 150 Future Problem Solving alumni to understand the impact of their participation in Future Problem Solving as students or volunteers.

Percentage of Alumni Rating Important and Extremely Important in Developing Skill Sets

- 96% Look at the “Big Picture”

- 93% Critical Thinking

- 93% Teamwork and Collaboration

- 93% Identify and Solve Problems

- 93% Time Management

- 90% Researching

- 90% Evaluation and Decision Making

- 86% Creativity and Innovation

- 86% Written Communication

The report captured alumni’s positive experiences as students in Future Problem Solving and documented that the alumni continued to utilize the FPS-structured approach to solving problems in their adult lives.

Executive Director

A seasoned educator, April Michele has served as the Executive Director since 2018 and been with Future Problem Solving more than a decade. Her background in advanced curriculum strategies and highly engaging learning techniques translates well in the development of materials, publications, training, and marketing for the organization and its global network. April’s expertise includes pedagogy and strategies for critical and creative thinking and providing quality educational services for students and adults worldwide.

Prior to joining Future Problem Solving, April taught elementary and middle grades, spending most of her classroom career in gifted education. She earned the National Board certification (NBPTS) as a Middle Childhood/Generalist and later served as a National Board assessor for the certification of others. In addition, April facilitated the Theory and Development of Creativity course for the state of Florida’s certification of teachers. She has also collaborated on a variety of special projects through the Department of Education. Beyond her U.S. education credentials, she has been trained for the International Baccalaureate Middle Years Programme (MYP) in Humanities.

A graduate of the University of Central Florida with a bachelor’s in Elementary Education and the University of South Florida with a master’s in Gifted Education, April’s passion is providing a challenging curriculum for 21st century students so they are equipped with the problem-solving and ethical leadership skills they need to thrive in the future. As a board member in her local Rotary Club, she facilitates problem solving in leadership at the Rotary Youth Leadership Awards (RYLA). She is also a certified Project Management Professional (PMP) from the Project Management Institute and earned her certificate in Nonprofit Management from the Edyth Bush Institute at Rollins College.

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

10 Problem-solving strategies to turn challenges on their head

Jump to section

What is an example of problem-solving?

What are the 5 steps to problem-solving, 10 effective problem-solving strategies, what skills do efficient problem solvers have, how to improve your problem-solving skills.

Problems come in all shapes and sizes — from workplace conflict to budget cuts.

Creative problem-solving is one of the most in-demand skills in all roles and industries. It can boost an organization’s human capital and give it a competitive edge.

Problem-solving strategies are ways of approaching problems that can help you look beyond the obvious answers and find the best solution to your problem .

Let’s take a look at a five-step problem-solving process and how to combine it with proven problem-solving strategies. This will give you the tools and skills to solve even your most complex problems.

Good problem-solving is an essential part of the decision-making process . To see what a problem-solving process might look like in real life, let’s take a common problem for SaaS brands — decreasing customer churn rates.

To solve this problem, the company must first identify it. In this case, the problem is that the churn rate is too high.

Next, they need to identify the root causes of the problem. This could be anything from their customer service experience to their email marketing campaigns. If there are several problems, they will need a separate problem-solving process for each one.

Let’s say the problem is with email marketing — they’re not nurturing existing customers. Now that they’ve identified the problem, they can start using problem-solving strategies to look for solutions.

This might look like coming up with special offers, discounts, or bonuses for existing customers. They need to find ways to remind them to use their products and services while providing added value. This will encourage customers to keep paying their monthly subscriptions.

They might also want to add incentives, such as access to a premium service at no extra cost after 12 months of membership. They could publish blog posts that help their customers solve common problems and share them as an email newsletter.

The company should set targets and a time frame in which to achieve them. This will allow leaders to measure progress and identify which actions yield the best results.

Perhaps you’ve got a problem you need to tackle. Or maybe you want to be prepared the next time one arises. Either way, it’s a good idea to get familiar with the five steps of problem-solving.

Use this step-by-step problem-solving method with the strategies in the following section to find possible solutions to your problem.

1. Identify the problem

The first step is to know which problem you need to solve. Then, you need to find the root cause of the problem.

The best course of action is to gather as much data as possible, speak to the people involved, and separate facts from opinions.

Once this is done, formulate a statement that describes the problem. Use rational persuasion to make sure your team agrees .

2. Break the problem down

Identifying the problem allows you to see which steps need to be taken to solve it.

First, break the problem down into achievable blocks. Then, use strategic planning to set a time frame in which to solve the problem and establish a timeline for the completion of each stage.

3. Generate potential solutions

At this stage, the aim isn’t to evaluate possible solutions but to generate as many ideas as possible.

Encourage your team to use creative thinking and be patient — the best solution may not be the first or most obvious one.

Use one or more of the different strategies in the following section to help come up with solutions — the more creative, the better.

4. Evaluate the possible solutions

Once you’ve generated potential solutions, narrow them down to a shortlist. Then, evaluate the options on your shortlist.

There are usually many factors to consider. So when evaluating a solution, ask yourself the following questions:

- Will my team be on board with the proposition?

- Does the solution align with organizational goals ?

- Is the solution likely to achieve the desired outcomes?

- Is the solution realistic and possible with current resources and constraints?

- Will the solution solve the problem without causing additional unintended problems?

5. Implement and monitor the solutions

Once you’ve identified your solution and got buy-in from your team, it’s time to implement it.

But the work doesn’t stop there. You need to monitor your solution to see whether it actually solves your problem.

Request regular feedback from the team members involved and have a monitoring and evaluation plan in place to measure progress.

If the solution doesn’t achieve your desired results, start this step-by-step process again.

There are many different ways to approach problem-solving. Each is suitable for different types of problems.

The most appropriate problem-solving techniques will depend on your specific problem. You may need to experiment with several strategies before you find a workable solution.

Here are 10 effective problem-solving strategies for you to try:

- Use a solution that worked before

- Brainstorming

- Work backward

- Use the Kipling method

- Draw the problem

- Use trial and error

- Sleep on it

- Get advice from your peers

- Use the Pareto principle

- Add successful solutions to your toolkit

Let’s break each of these down.

1. Use a solution that worked before

It might seem obvious, but if you’ve faced similar problems in the past, look back to what worked then. See if any of the solutions could apply to your current situation and, if so, replicate them.

2. Brainstorming

The more people you enlist to help solve the problem, the more potential solutions you can come up with.

Use different brainstorming techniques to workshop potential solutions with your team. They’ll likely bring something you haven’t thought of to the table.

3. Work backward

Working backward is a way to reverse engineer your problem. Imagine your problem has been solved, and make that the starting point.

Then, retrace your steps back to where you are now. This can help you see which course of action may be most effective.

4. Use the Kipling method

This is a method that poses six questions based on Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “ I Keep Six Honest Serving Men .”

- What is the problem?

- Why is the problem important?

- When did the problem arise, and when does it need to be solved?

- How did the problem happen?

- Where is the problem occurring?

- Who does the problem affect?

Answering these questions can help you identify possible solutions.

5. Draw the problem

Sometimes it can be difficult to visualize all the components and moving parts of a problem and its solution. Drawing a diagram can help.

This technique is particularly helpful for solving process-related problems. For example, a product development team might want to decrease the time they take to fix bugs and create new iterations. Drawing the processes involved can help you see where improvements can be made.

6. Use trial-and-error

A trial-and-error approach can be useful when you have several possible solutions and want to test them to see which one works best.

7. Sleep on it

Finding the best solution to a problem is a process. Remember to take breaks and get enough rest . Sometimes, a walk around the block can bring inspiration, but you should sleep on it if possible.

A good night’s sleep helps us find creative solutions to problems. This is because when you sleep, your brain sorts through the day’s events and stores them as memories. This enables you to process your ideas at a subconscious level.

If possible, give yourself a few days to develop and analyze possible solutions. You may find you have greater clarity after sleeping on it. Your mind will also be fresh, so you’ll be able to make better decisions.

8. Get advice from your peers

Getting input from a group of people can help you find solutions you may not have thought of on your own.

For solo entrepreneurs or freelancers, this might look like hiring a coach or mentor or joining a mastermind group.

For leaders , it might be consulting other members of the leadership team or working with a business coach .

It’s important to recognize you might not have all the skills, experience, or knowledge necessary to find a solution alone.

9. Use the Pareto principle

The Pareto principle — also known as the 80/20 rule — can help you identify possible root causes and potential solutions for your problems.

Although it’s not a mathematical law, it’s a principle found throughout many aspects of business and life. For example, 20% of the sales reps in a company might close 80% of the sales.

You may be able to narrow down the causes of your problem by applying the Pareto principle. This can also help you identify the most appropriate solutions.

10. Add successful solutions to your toolkit

Every situation is different, and the same solutions might not always work. But by keeping a record of successful problem-solving strategies, you can build up a solutions toolkit.

These solutions may be applicable to future problems. Even if not, they may save you some of the time and work needed to come up with a new solution.

Improving problem-solving skills is essential for professional development — both yours and your team’s. Here are some of the key skills of effective problem solvers:

- Critical thinking and analytical skills

- Communication skills , including active listening

- Decision-making

- Planning and prioritization

- Emotional intelligence , including empathy and emotional regulation

- Time management

- Data analysis

- Research skills

- Project management

And they see problems as opportunities. Everyone is born with problem-solving skills. But accessing these abilities depends on how we view problems. Effective problem-solvers see problems as opportunities to learn and improve.

Ready to work on your problem-solving abilities? Get started with these seven tips.

1. Build your problem-solving skills

One of the best ways to improve your problem-solving skills is to learn from experts. Consider enrolling in organizational training , shadowing a mentor , or working with a coach .

2. Practice

Practice using your new problem-solving skills by applying them to smaller problems you might encounter in your daily life.

Alternatively, imagine problematic scenarios that might arise at work and use problem-solving strategies to find hypothetical solutions.

3. Don’t try to find a solution right away

Often, the first solution you think of to solve a problem isn’t the most appropriate or effective.

Instead of thinking on the spot, give yourself time and use one or more of the problem-solving strategies above to activate your creative thinking.

4. Ask for feedback

Receiving feedback is always important for learning and growth. Your perception of your problem-solving skills may be different from that of your colleagues. They can provide insights that help you improve.

5. Learn new approaches and methodologies

There are entire books written about problem-solving methodologies if you want to take a deep dive into the subject.

We recommend starting with “ Fixed — How to Perfect the Fine Art of Problem Solving ” by Amy E. Herman.

6. Experiment

Tried-and-tested problem-solving techniques can be useful. However, they don’t teach you how to innovate and develop your own problem-solving approaches.

Sometimes, an unconventional approach can lead to the development of a brilliant new idea or strategy. So don’t be afraid to suggest your most “out there” ideas.

7. Analyze the success of your competitors

Do you have competitors who have already solved the problem you’re facing? Look at what they did, and work backward to solve your own problem.

For example, Netflix started in the 1990s as a DVD mail-rental company. Its main competitor at the time was Blockbuster.

But when streaming became the norm in the early 2000s, both companies faced a crisis. Netflix innovated, unveiling its streaming service in 2007.

If Blockbuster had followed Netflix’s example, it might have survived. Instead, it declared bankruptcy in 2010.

Use problem-solving strategies to uplevel your business

When facing a problem, it’s worth taking the time to find the right solution.

Otherwise, we risk either running away from our problems or headlong into solutions. When we do this, we might miss out on other, better options.

Use the problem-solving strategies outlined above to find innovative solutions to your business’ most perplexing problems.

If you’re ready to take problem-solving to the next level, request a demo with BetterUp . Our expert coaches specialize in helping teams develop and implement strategies that work.

Boost your productivity

Maximize your time and productivity with strategies from our expert coaches.

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

8 creative solutions to your most challenging problems

5 problem-solving questions to prepare you for your next interview, what are metacognitive skills examples in everyday life, what is lateral thinking 7 techniques to encourage creative ideas, 31 examples of problem solving performance review phrases, leadership activities that encourage employee engagement, learn what process mapping is and how to create one (+ examples), how much do distractions cost 8 effects of lack of focus, can dreams help you solve problems 6 ways to try, similar articles, the pareto principle: how the 80/20 rule can help you do more with less, thinking outside the box: 8 ways to become a creative problem solver, 3 problem statement examples and steps to write your own, what is tacit knowledge, and how does it benefit the workplace, contingency planning: 4 steps to prepare for the unexpected, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What Are Problem-Solving Skills? Definition and Examples

- Share on Twitter Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn Share on LinkedIn

Forage puts students first. Our blog articles are written independently by our editorial team. They have not been paid for or sponsored by our partners. See our full editorial guidelines .

Why do employers hire employees? To help them solve problems. Whether you’re a financial analyst deciding where to invest your firm’s money, or a marketer trying to figure out which channel to direct your efforts, companies hire people to help them find solutions. Problem-solving is an essential and marketable soft skill in the workplace.

So, how can you improve your problem-solving and show employers you have this valuable skill? In this guide, we’ll cover:

Problem-Solving Skills Definition

Why are problem-solving skills important, problem-solving skills examples, how to include problem-solving skills in a job application, how to improve problem-solving skills, problem-solving: the bottom line.

Problem-solving skills are the ability to identify problems, brainstorm and analyze answers, and implement the best solutions. An employee with good problem-solving skills is both a self-starter and a collaborative teammate; they are proactive in understanding the root of a problem and work with others to consider a wide range of solutions before deciding how to move forward.

Examples of using problem-solving skills in the workplace include:

- Researching patterns to understand why revenue decreased last quarter

- Experimenting with a new marketing channel to increase website sign-ups

- Brainstorming content types to share with potential customers

- Testing calls to action to see which ones drive the most product sales

- Implementing a new workflow to automate a team process and increase productivity

Problem-solving skills are the most sought-after soft skill of 2022. In fact, 86% of employers look for problem-solving skills on student resumes, according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers Job Outlook 2022 survey .

It’s unsurprising why employers are looking for this skill: companies will always need people to help them find solutions to their problems. Someone proactive and successful at problem-solving is valuable to any team.

“Employers are looking for employees who can make decisions independently, especially with the prevalence of remote/hybrid work and the need to communicate asynchronously,” Eric Mochnacz, senior HR consultant at Red Clover, says. “Employers want to see individuals who can make well-informed decisions that mitigate risk, and they can do so without suffering from analysis paralysis.”

Showcase new skills

Build the confidence and practical skills that employers are looking for with Forage’s free job simulations.

Problem-solving includes three main parts: identifying the problem, analyzing possible solutions, and deciding on the best course of action.

>>MORE: Discover the right career for you based on your skills with a career aptitude test .

Research is the first step of problem-solving because it helps you understand the context of a problem. Researching a problem enables you to learn why the problem is happening. For example, is revenue down because of a new sales tactic? Or because of seasonality? Is there a problem with who the sales team is reaching out to?

Research broadens your scope to all possible reasons why the problem could be happening. Then once you figure it out, it helps you narrow your scope to start solving it.

Analysis is the next step of problem-solving. Now that you’ve identified the problem, analytical skills help you look at what potential solutions there might be.

“The goal of analysis isn’t to solve a problem, actually — it’s to better understand it because that’s where the real solution will be found,” Gretchen Skalka, owner of Career Insights Consulting, says. “Looking at a problem through the lens of impartiality is the only way to get a true understanding of it from all angles.”

Decision-Making

Once you’ve figured out where the problem is coming from and what solutions are, it’s time to decide on the best way to go forth. Decision-making skills help you determine what resources are available, what a feasible action plan entails, and what solution is likely to lead to success.

On a Resume

Employers looking for problem-solving skills might include the word “problem-solving” or other synonyms like “ critical thinking ” or “analytical skills” in the job description.

“I would add ‘buzzwords’ you can find from the job descriptions or LinkedIn endorsements section to filter into your resume to comply with the ATS,” Matthew Warzel, CPRW resume writer, advises. Warzel recommends including these skills on your resume but warns to “leave the soft skills as adjectives in the summary section. That is the only place soft skills should be mentioned.”

On the other hand, you can list hard skills separately in a skills section on your resume .

Forage Resume Writing Masterclass

Learn how to showcase your skills and craft an award-winning resume with this free masterclass from Forage.

Avg. Time: 5 to 6 hours

Skills you’ll build: Resume writing, professional brand, professional summary, narrative, transferable skills, industry keywords, illustrating your impact, standing out

In a Cover Letter or an Interview

Explaining your problem-solving skills in an interview can seem daunting. You’re required to expand on your process — how you identified a problem, analyzed potential solutions, and made a choice. As long as you can explain your approach, it’s okay if that solution didn’t come from a professional work experience.

“Young professionals shortchange themselves by thinking only paid-for solutions matter to employers,” Skalka says. “People at the genesis of their careers don’t have a wealth of professional experience to pull from, but they do have relevant experience to share.”

Aaron Case, career counselor and CPRW at Resume Genius, agrees and encourages early professionals to share this skill. “If you don’t have any relevant work experience yet, you can still highlight your problem-solving skills in your cover letter,” he says. “Just showcase examples of problems you solved while completing your degree, working at internships, or volunteering. You can even pull examples from completely unrelated part-time jobs, as long as you make it clear how your problem-solving ability transfers to your new line of work.”

Learn How to Identify Problems

Problem-solving doesn’t just require finding solutions to problems that are already there. It’s also about being proactive when something isn’t working as you hoped it would. Practice questioning and getting curious about processes and activities in your everyday life. What could you improve? What would you do if you had more resources for this process? If you had fewer? Challenge yourself to challenge the world around you.

Think Digitally

“Employers in the modern workplace value digital problem-solving skills, like being able to find a technology solution to a traditional issue,” Case says. “For example, when I first started working as a marketing writer, my department didn’t have the budget to hire a professional voice actor for marketing video voiceovers. But I found a perfect solution to the problem with an AI voiceover service that cost a fraction of the price of an actor.”

Being comfortable with new technology — even ones you haven’t used before — is a valuable skill in an increasingly hybrid and remote world. Don’t be afraid to research new and innovative technologies to help automate processes or find a more efficient technological solution.

Collaborate

Problem-solving isn’t done in a silo, and it shouldn’t be. Use your collaboration skills to gather multiple perspectives, help eliminate bias, and listen to alternative solutions. Ask others where they think the problem is coming from and what solutions would help them with your workflow. From there, try to compromise on a solution that can benefit everyone.

If we’ve learned anything from the past few years, it’s that the world of work is constantly changing — which means it’s crucial to know how to adapt . Be comfortable narrowing down a solution, then changing your direction when a colleague provides a new piece of information. Challenge yourself to get out of your comfort zone, whether with your personal routine or trying a new system at work.

Put Yourself in the Middle of Tough Moments

Just like adapting requires you to challenge your routine and tradition, good problem-solving requires you to put yourself in challenging situations — especially ones where you don’t have relevant experience or expertise to find a solution. Because you won’t know how to tackle the problem, you’ll learn new problem-solving skills and how to navigate new challenges. Ask your manager or a peer if you can help them work on a complicated problem, and be proactive about asking them questions along the way.

Career Aptitude Test

What careers are right for you based on your skills? Take this quiz to find out. It’s completely free — you’ll just need to sign up to get your results!

Step 1 of 3

Companies always need people to help them find solutions — especially proactive employees who have practical analytical skills and can collaborate to decide the best way to move forward. Whether or not you have experience solving problems in a professional workplace, illustrate your problem-solving skills by describing your research, analysis, and decision-making process — and make it clear that you’re the solution to the employer’s current problems.

Looking to learn more workplace professional skills? Check out Two Sigma’s Professional Skills Development Virtual Experience Program .

Image Credit: Christina Morillo / Pexels

Related Posts

6 negotiation skills to level up your work life, how to build conflict resolution skills: case studies and examples, what is github uses and getting started, upskill with forage.

Build career skills recruiters are looking for.

How to improve your problem solving skills and build effective problem solving strategies

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps, 18 free facilitation resources we think you’ll love.

- 47 useful online tools for workshop planning and meeting facilitation

Effective problem solving is all about using the right process and following a plan tailored to the issue at hand. Recognizing your team or organization has an issue isn’t enough to come up with effective problem solving strategies.

To truly understand a problem and develop appropriate solutions, you will want to follow a solid process, follow the necessary problem solving steps, and bring all of your problem solving skills to the table.

We’ll first guide you through the seven step problem solving process you and your team can use to effectively solve complex business challenges. We’ll also look at what problem solving strategies you can employ with your team when looking for a way to approach the process. We’ll then discuss the problem solving skills you need to be more effective at solving problems, complete with an activity from the SessionLab library you can use to develop that skill in your team.

Let’s get to it!

What is a problem solving process?

- What are the problem solving steps I need to follow?

Problem solving strategies

What skills do i need to be an effective problem solver, how can i improve my problem solving skills.

Solving problems is like baking a cake. You can go straight into the kitchen without a recipe or the right ingredients and do your best, but the end result is unlikely to be very tasty!

Using a process to bake a cake allows you to use the best ingredients without waste, collect the right tools, account for allergies, decide whether it is a birthday or wedding cake, and then bake efficiently and on time. The result is a better cake that is fit for purpose, tastes better and has created less mess in the kitchen. Also, it should have chocolate sprinkles. Having a step by step process to solve organizational problems allows you to go through each stage methodically and ensure you are trying to solve the right problems and select the most appropriate, effective solutions.

What are the problem solving steps I need to follow?

All problem solving processes go through a number of steps in order to move from identifying a problem to resolving it.

Depending on your problem solving model and who you ask, there can be anything between four and nine problem solving steps you should follow in order to find the right solution. Whatever framework you and your group use, there are some key items that should be addressed in order to have an effective process.

We’ve looked at problem solving processes from sources such as the American Society for Quality and their four step approach , and Mediate ‘s six step process. By reflecting on those and our own problem solving processes, we’ve come up with a sequence of seven problem solving steps we feel best covers everything you need in order to effectively solve problems.

1. Problem identification

The first stage of any problem solving process is to identify the problem or problems you might want to solve. Effective problem solving strategies always begin by allowing a group scope to articulate what they believe the problem to be and then coming to some consensus over which problem they approach first. Problem solving activities used at this stage often have a focus on creating frank, open discussion so that potential problems can be brought to the surface.

2. Problem analysis

Though this step is not a million miles from problem identification, problem analysis deserves to be considered separately. It can often be an overlooked part of the process and is instrumental when it comes to developing effective solutions.

The process of problem analysis means ensuring that the problem you are seeking to solve is the right problem . As part of this stage, you may look deeper and try to find the root cause of a specific problem at a team or organizational level.

Remember that problem solving strategies should not only be focused on putting out fires in the short term but developing long term solutions that deal with the root cause of organizational challenges.

Whatever your approach, analyzing a problem is crucial in being able to select an appropriate solution and the problem solving skills deployed in this stage are beneficial for the rest of the process and ensuring the solutions you create are fit for purpose.

3. Solution generation

Once your group has nailed down the particulars of the problem you wish to solve, you want to encourage a free flow of ideas connecting to solving that problem. This can take the form of problem solving games that encourage creative thinking or problem solving activities designed to produce working prototypes of possible solutions.

The key to ensuring the success of this stage of the problem solving process is to encourage quick, creative thinking and create an open space where all ideas are considered. The best solutions can come from unlikely places and by using problem solving techniques that celebrate invention, you might come up with solution gold.

4. Solution development

No solution is likely to be perfect right out of the gate. It’s important to discuss and develop the solutions your group has come up with over the course of following the previous problem solving steps in order to arrive at the best possible solution. Problem solving games used in this stage involve lots of critical thinking, measuring potential effort and impact, and looking at possible solutions analytically.

During this stage, you will often ask your team to iterate and improve upon your frontrunning solutions and develop them further. Remember that problem solving strategies always benefit from a multitude of voices and opinions, and not to let ego get involved when it comes to choosing which solutions to develop and take further.

Finding the best solution is the goal of all problem solving workshops and here is the place to ensure that your solution is well thought out, sufficiently robust and fit for purpose.

5. Decision making

Nearly there! Once your group has reached consensus and selected a solution that applies to the problem at hand you have some decisions to make. You will want to work on allocating ownership of the project, figure out who will do what, how the success of the solution will be measured and decide the next course of action.

The decision making stage is a part of the problem solving process that can get missed or taken as for granted. Fail to properly allocate roles and plan out how a solution will actually be implemented and it less likely to be successful in solving the problem.

Have clear accountabilities, actions, timeframes, and follow-ups. Make these decisions and set clear next-steps in the problem solving workshop so that everyone is aligned and you can move forward effectively as a group.

Ensuring that you plan for the roll-out of a solution is one of the most important problem solving steps. Without adequate planning or oversight, it can prove impossible to measure success or iterate further if the problem was not solved.

6. Solution implementation

This is what we were waiting for! All problem solving strategies have the end goal of implementing a solution and solving a problem in mind.

Remember that in order for any solution to be successful, you need to help your group through all of the previous problem solving steps thoughtfully. Only then can you ensure that you are solving the right problem but also that you have developed the correct solution and can then successfully implement and measure the impact of that solution.

Project management and communication skills are key here – your solution may need to adjust when out in the wild or you might discover new challenges along the way.

7. Solution evaluation

So you and your team developed a great solution to a problem and have a gut feeling its been solved. Work done, right? Wrong. All problem solving strategies benefit from evaluation, consideration, and feedback. You might find that the solution does not work for everyone, might create new problems, or is potentially so successful that you will want to roll it out to larger teams or as part of other initiatives.

None of that is possible without taking the time to evaluate the success of the solution you developed in your problem solving model and adjust if necessary.

Remember that the problem solving process is often iterative and it can be common to not solve complex issues on the first try. Even when this is the case, you and your team will have generated learning that will be important for future problem solving workshops or in other parts of the organization.

It’s worth underlining how important record keeping is throughout the problem solving process. If a solution didn’t work, you need to have the data and records to see why that was the case. If you go back to the drawing board, notes from the previous workshop can help save time. Data and insight is invaluable at every stage of the problem solving process and this one is no different.

Problem solving workshops made easy

Problem solving strategies are methods of approaching and facilitating the process of problem-solving with a set of techniques , actions, and processes. Different strategies are more effective if you are trying to solve broad problems such as achieving higher growth versus more focused problems like, how do we improve our customer onboarding process?

Broadly, the problem solving steps outlined above should be included in any problem solving strategy though choosing where to focus your time and what approaches should be taken is where they begin to differ. You might find that some strategies ask for the problem identification to be done prior to the session or that everything happens in the course of a one day workshop.

The key similarity is that all good problem solving strategies are structured and designed. Four hours of open discussion is never going to be as productive as a four-hour workshop designed to lead a group through a problem solving process.

Good problem solving strategies are tailored to the team, organization and problem you will be attempting to solve. Here are some example problem solving strategies you can learn from or use to get started.

Use a workshop to lead a team through a group process

Often, the first step to solving problems or organizational challenges is bringing a group together effectively. Most teams have the tools, knowledge, and expertise necessary to solve their challenges – they just need some guidance in how to use leverage those skills and a structure and format that allows people to focus their energies.

Facilitated workshops are one of the most effective ways of solving problems of any scale. By designing and planning your workshop carefully, you can tailor the approach and scope to best fit the needs of your team and organization.

Problem solving workshop

- Creating a bespoke, tailored process

- Tackling problems of any size

- Building in-house workshop ability and encouraging their use

Workshops are an effective strategy for solving problems. By using tried and test facilitation techniques and methods, you can design and deliver a workshop that is perfectly suited to the unique variables of your organization. You may only have the capacity for a half-day workshop and so need a problem solving process to match.

By using our session planner tool and importing methods from our library of 700+ facilitation techniques, you can create the right problem solving workshop for your team. It might be that you want to encourage creative thinking or look at things from a new angle to unblock your groups approach to problem solving. By tailoring your workshop design to the purpose, you can help ensure great results.

One of the main benefits of a workshop is the structured approach to problem solving. Not only does this mean that the workshop itself will be successful, but many of the methods and techniques will help your team improve their working processes outside of the workshop.

We believe that workshops are one of the best tools you can use to improve the way your team works together. Start with a problem solving workshop and then see what team building, culture or design workshops can do for your organization!

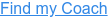

Run a design sprint

Great for:

- aligning large, multi-discipline teams

- quickly designing and testing solutions

- tackling large, complex organizational challenges and breaking them down into smaller tasks

By using design thinking principles and methods, a design sprint is a great way of identifying, prioritizing and prototyping solutions to long term challenges that can help solve major organizational problems with quick action and measurable results.

Some familiarity with design thinking is useful, though not integral, and this strategy can really help a team align if there is some discussion around which problems should be approached first.

The stage-based structure of the design sprint is also very useful for teams new to design thinking. The inspiration phase, where you look to competitors that have solved your problem, and the rapid prototyping and testing phases are great for introducing new concepts that will benefit a team in all their future work.

It can be common for teams to look inward for solutions and so looking to the market for solutions you can iterate on can be very productive. Instilling an agile prototyping and testing mindset can also be great when helping teams move forwards – generating and testing solutions quickly can help save time in the long run and is also pretty exciting!

Break problems down into smaller issues

Organizational challenges and problems are often complicated and large scale in nature. Sometimes, trying to resolve such an issue in one swoop is simply unachievable or overwhelming. Try breaking down such problems into smaller issues that you can work on step by step. You may not be able to solve the problem of churning customers off the bat, but you can work with your team to identify smaller effort but high impact elements and work on those first.

This problem solving strategy can help a team generate momentum, prioritize and get some easy wins. It’s also a great strategy to employ with teams who are just beginning to learn how to approach the problem solving process. If you want some insight into a way to employ this strategy, we recommend looking at our design sprint template below!

Use guiding frameworks or try new methodologies

Some problems are best solved by introducing a major shift in perspective or by using new methodologies that encourage your team to think differently.

Props and tools such as Methodkit , which uses a card-based toolkit for facilitation, or Lego Serious Play can be great ways to engage your team and find an inclusive, democratic problem solving strategy. Remember that play and creativity are great tools for achieving change and whatever the challenge, engaging your participants can be very effective where other strategies may have failed.

LEGO Serious Play

- Improving core problem solving skills

- Thinking outside of the box

- Encouraging creative solutions

LEGO Serious Play is a problem solving methodology designed to get participants thinking differently by using 3D models and kinesthetic learning styles. By physically building LEGO models based on questions and exercises, participants are encouraged to think outside of the box and create their own responses.

Collaborate LEGO Serious Play exercises are also used to encourage communication and build problem solving skills in a group. By using this problem solving process, you can often help different kinds of learners and personality types contribute and unblock organizational problems with creative thinking.

Problem solving strategies like LEGO Serious Play are super effective at helping a team solve more skills-based problems such as communication between teams or a lack of creative thinking. Some problems are not suited to LEGO Serious Play and require a different problem solving strategy.

Card Decks and Method Kits

- New facilitators or non-facilitators

- Approaching difficult subjects with a simple, creative framework

- Engaging those with varied learning styles

Card decks and method kids are great tools for those new to facilitation or for whom facilitation is not the primary role. Card decks such as the emotional culture deck can be used for complete workshops and in many cases, can be used right out of the box. Methodkit has a variety of kits designed for scenarios ranging from personal development through to personas and global challenges so you can find the right deck for your particular needs.

Having an easy to use framework that encourages creativity or a new approach can take some of the friction or planning difficulties out of the workshop process and energize a team in any setting. Simplicity is the key with these methods. By ensuring everyone on your team can get involved and engage with the process as quickly as possible can really contribute to the success of your problem solving strategy.

Source external advice

Looking to peers, experts and external facilitators can be a great way of approaching the problem solving process. Your team may not have the necessary expertise, insights of experience to tackle some issues, or you might simply benefit from a fresh perspective. Some problems may require bringing together an entire team, and coaching managers or team members individually might be the right approach. Remember that not all problems are best resolved in the same manner.

If you’re a solo entrepreneur, peer groups, coaches and mentors can also be invaluable at not only solving specific business problems, but in providing a support network for resolving future challenges. One great approach is to join a Mastermind Group and link up with like-minded individuals and all grow together. Remember that however you approach the sourcing of external advice, do so thoughtfully, respectfully and honestly. Reciprocate where you can and prepare to be surprised by just how kind and helpful your peers can be!

Mastermind Group

- Solo entrepreneurs or small teams with low capacity

- Peer learning and gaining outside expertise

- Getting multiple external points of view quickly

Problem solving in large organizations with lots of skilled team members is one thing, but how about if you work for yourself or in a very small team without the capacity to get the most from a design sprint or LEGO Serious Play session?

A mastermind group – sometimes known as a peer advisory board – is where a group of people come together to support one another in their own goals, challenges, and businesses. Each participant comes to the group with their own purpose and the other members of the group will help them create solutions, brainstorm ideas, and support one another.

Mastermind groups are very effective in creating an energized, supportive atmosphere that can deliver meaningful results. Learning from peers from outside of your organization or industry can really help unlock new ways of thinking and drive growth. Access to the experience and skills of your peers can be invaluable in helping fill the gaps in your own ability, particularly in young companies.

A mastermind group is a great solution for solo entrepreneurs, small teams, or for organizations that feel that external expertise or fresh perspectives will be beneficial for them. It is worth noting that Mastermind groups are often only as good as the participants and what they can bring to the group. Participants need to be committed, engaged and understand how to work in this context.

Coaching and mentoring

- Focused learning and development

- Filling skills gaps

- Working on a range of challenges over time

Receiving advice from a business coach or building a mentor/mentee relationship can be an effective way of resolving certain challenges. The one-to-one format of most coaching and mentor relationships can really help solve the challenges those individuals are having and benefit the organization as a result.

A great mentor can be invaluable when it comes to spotting potential problems before they arise and coming to understand a mentee very well has a host of other business benefits. You might run an internal mentorship program to help develop your team’s problem solving skills and strategies or as part of a large learning and development program. External coaches can also be an important part of your problem solving strategy, filling skills gaps for your management team or helping with specific business issues.

Now we’ve explored the problem solving process and the steps you will want to go through in order to have an effective session, let’s look at the skills you and your team need to be more effective problem solvers.

Problem solving skills are highly sought after, whatever industry or team you work in. Organizations are keen to employ people who are able to approach problems thoughtfully and find strong, realistic solutions. Whether you are a facilitator , a team leader or a developer, being an effective problem solver is a skill you’ll want to develop.

Problem solving skills form a whole suite of techniques and approaches that an individual uses to not only identify problems but to discuss them productively before then developing appropriate solutions.

Here are some of the most important problem solving skills everyone from executives to junior staff members should learn. We’ve also included an activity or exercise from the SessionLab library that can help you and your team develop that skill.

If you’re running a workshop or training session to try and improve problem solving skills in your team, try using these methods to supercharge your process!

Active listening

Active listening is one of the most important skills anyone who works with people can possess. In short, active listening is a technique used to not only better understand what is being said by an individual, but also to be more aware of the underlying message the speaker is trying to convey. When it comes to problem solving, active listening is integral for understanding the position of every participant and to clarify the challenges, ideas and solutions they bring to the table.

Some active listening skills include:

- Paying complete attention to the speaker.

- Removing distractions.

- Avoid interruption.

- Taking the time to fully understand before preparing a rebuttal.

- Responding respectfully and appropriately.

- Demonstrate attentiveness and positivity with an open posture, making eye contact with the speaker, smiling and nodding if appropriate. Show that you are listening and encourage them to continue.

- Be aware of and respectful of feelings. Judge the situation and respond appropriately. You can disagree without being disrespectful.

- Observe body language.

- Paraphrase what was said in your own words, either mentally or verbally.

- Remain neutral.

- Reflect and take a moment before responding.

- Ask deeper questions based on what is said and clarify points where necessary.

Active Listening #hyperisland #skills #active listening #remote-friendly This activity supports participants to reflect on a question and generate their own solutions using simple principles of active listening and peer coaching. It’s an excellent introduction to active listening but can also be used with groups that are already familiar with it. Participants work in groups of three and take turns being: “the subject”, the listener, and the observer.

Analytical skills

All problem solving models require strong analytical skills, particularly during the beginning of the process and when it comes to analyzing how solutions have performed.

Analytical skills are primarily focused on performing an effective analysis by collecting, studying and parsing data related to a problem or opportunity.

It often involves spotting patterns, being able to see things from different perspectives and using observable facts and data to make suggestions or produce insight.

Analytical skills are also important at every stage of the problem solving process and by having these skills, you can ensure that any ideas or solutions you create or backed up analytically and have been sufficiently thought out.

Nine Whys #innovation #issue analysis #liberating structures With breathtaking simplicity, you can rapidly clarify for individuals and a group what is essentially important in their work. You can quickly reveal when a compelling purpose is missing in a gathering and avoid moving forward without clarity. When a group discovers an unambiguous shared purpose, more freedom and more responsibility are unleashed. You have laid the foundation for spreading and scaling innovations with fidelity.

Collaboration

Trying to solve problems on your own is difficult. Being able to collaborate effectively, with a free exchange of ideas, to delegate and be a productive member of a team is hugely important to all problem solving strategies.

Remember that whatever your role, collaboration is integral, and in a problem solving process, you are all working together to find the best solution for everyone.

Marshmallow challenge with debriefing #teamwork #team #leadership #collaboration In eighteen minutes, teams must build the tallest free-standing structure out of 20 sticks of spaghetti, one yard of tape, one yard of string, and one marshmallow. The marshmallow needs to be on top. The Marshmallow Challenge was developed by Tom Wujec, who has done the activity with hundreds of groups around the world. Visit the Marshmallow Challenge website for more information. This version has an extra debriefing question added with sample questions focusing on roles within the team.

Communication

Being an effective communicator means being empathetic, clear and succinct, asking the right questions, and demonstrating active listening skills throughout any discussion or meeting.

In a problem solving setting, you need to communicate well in order to progress through each stage of the process effectively. As a team leader, it may also fall to you to facilitate communication between parties who may not see eye to eye. Effective communication also means helping others to express themselves and be heard in a group.

Bus Trip #feedback #communication #appreciation #closing #thiagi #team This is one of my favourite feedback games. I use Bus Trip at the end of a training session or a meeting, and I use it all the time. The game creates a massive amount of energy with lots of smiles, laughs, and sometimes even a teardrop or two.

Creative problem solving skills can be some of the best tools in your arsenal. Thinking creatively, being able to generate lots of ideas and come up with out of the box solutions is useful at every step of the process.

The kinds of problems you will likely discuss in a problem solving workshop are often difficult to solve, and by approaching things in a fresh, creative manner, you can often create more innovative solutions.

Having practical creative skills is also a boon when it comes to problem solving. If you can help create quality design sketches and prototypes in record time, it can help bring a team to alignment more quickly or provide a base for further iteration.

The paper clip method #sharing #creativity #warm up #idea generation #brainstorming The power of brainstorming. A training for project leaders, creativity training, and to catalyse getting new solutions.

Critical thinking

Critical thinking is one of the fundamental problem solving skills you’ll want to develop when working on developing solutions. Critical thinking is the ability to analyze, rationalize and evaluate while being aware of personal bias, outlying factors and remaining open-minded.

Defining and analyzing problems without deploying critical thinking skills can mean you and your team go down the wrong path. Developing solutions to complex issues requires critical thinking too – ensuring your team considers all possibilities and rationally evaluating them.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix #issue analysis #liberating structures #problem solving You can help individuals or groups avoid the frequent mistake of trying to solve a problem with methods that are not adapted to the nature of their challenge. The combination of two questions makes it possible to easily sort challenges into four categories: simple, complicated, complex , and chaotic . A problem is simple when it can be solved reliably with practices that are easy to duplicate. It is complicated when experts are required to devise a sophisticated solution that will yield the desired results predictably. A problem is complex when there are several valid ways to proceed but outcomes are not predictable in detail. Chaotic is when the context is too turbulent to identify a path forward. A loose analogy may be used to describe these differences: simple is like following a recipe, complicated like sending a rocket to the moon, complex like raising a child, and chaotic is like the game “Pin the Tail on the Donkey.” The Liberating Structures Matching Matrix in Chapter 5 can be used as the first step to clarify the nature of a challenge and avoid the mismatches between problems and solutions that are frequently at the root of chronic, recurring problems.

Data analysis

Though it shares lots of space with general analytical skills, data analysis skills are something you want to cultivate in their own right in order to be an effective problem solver.

Being good at data analysis doesn’t just mean being able to find insights from data, but also selecting the appropriate data for a given issue, interpreting it effectively and knowing how to model and present that data. Depending on the problem at hand, it might also include a working knowledge of specific data analysis tools and procedures.

Having a solid grasp of data analysis techniques is useful if you’re leading a problem solving workshop but if you’re not an expert, don’t worry. Bring people into the group who has this skill set and help your team be more effective as a result.

Decision making

All problems need a solution and all solutions require that someone make the decision to implement them. Without strong decision making skills, teams can become bogged down in discussion and less effective as a result.

Making decisions is a key part of the problem solving process. It’s important to remember that decision making is not restricted to the leadership team. Every staff member makes decisions every day and developing these skills ensures that your team is able to solve problems at any scale. Remember that making decisions does not mean leaping to the first solution but weighing up the options and coming to an informed, well thought out solution to any given problem that works for the whole team.