- What Is Back Pain?

- Tests & Diagnosis

- Living With

- View Full Guide

An Overview of Spondylolisthesis

What Is Spondylolisthesis?

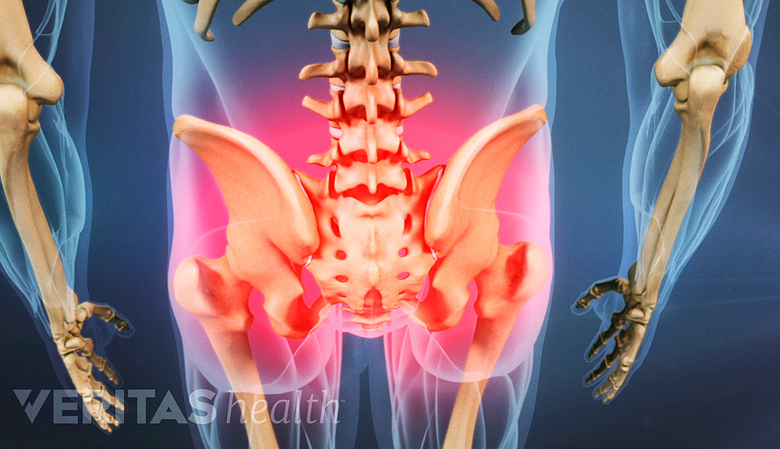

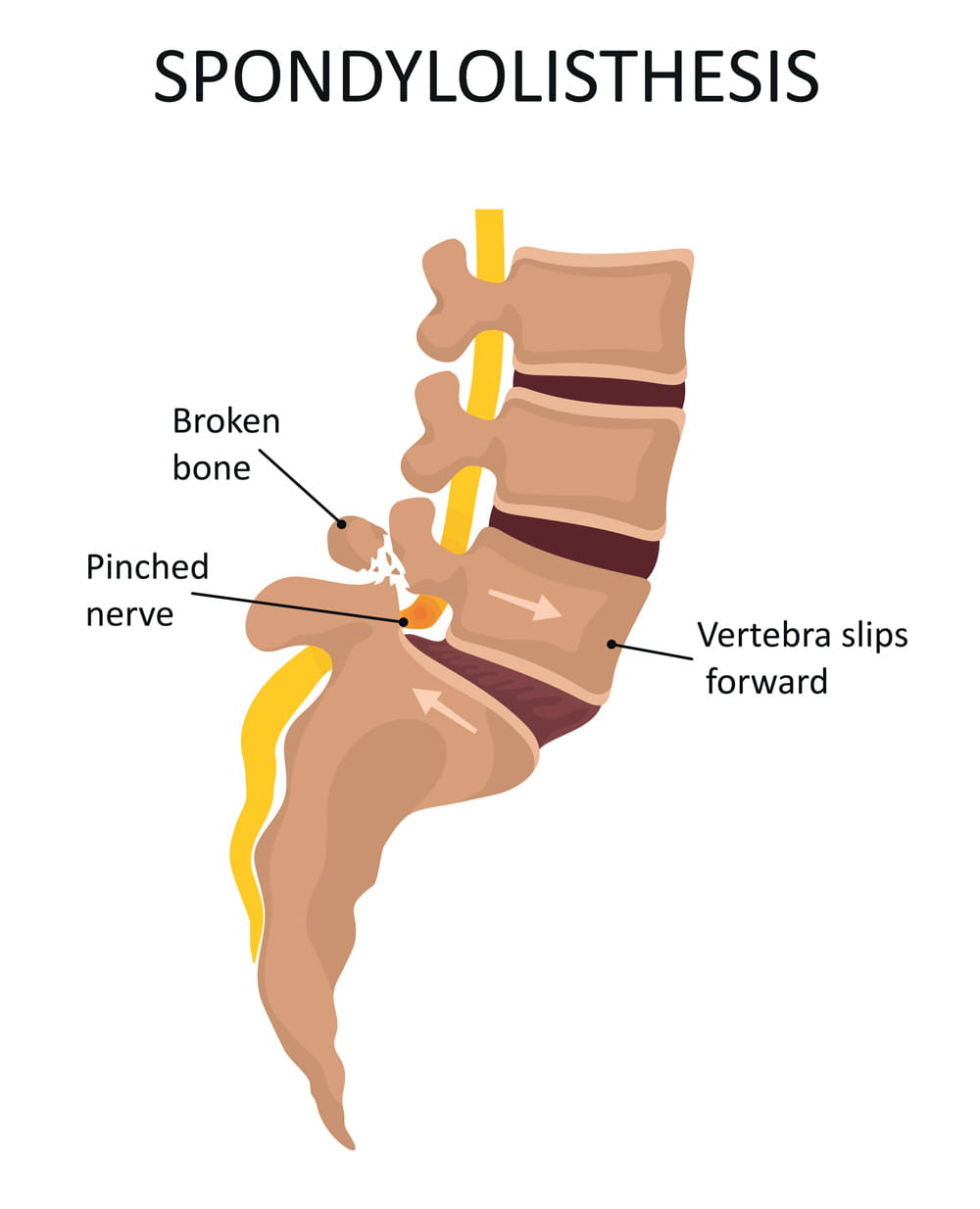

Spondylolisthesis (pronounced spahn-duh-low-liss-thee-sus) is a condition in which one of the bones in your spine (the vertebrae) slips out of place and moves on top of the vertebra next to it.

It usually happens at the base of your spine (lumbar spondylolisthesis). When the slipped vertebra puts pressure on a nerve, it can cause pain in your lower back or legs.

Spondylolisthesis Symptoms

Sometimes, people with this condition don't notice anything is wrong. But you can have symptoms that include:

- Lower back pain

- Muscle tightness and stiffness

- Pain in your buttocks

- Pain that spreads down your legs (due to pressure on nerve roots)

- Pain that gets worse when you move around

- Tight hamstrings (muscles in the back of your thighs)

- Trouble standing or walking

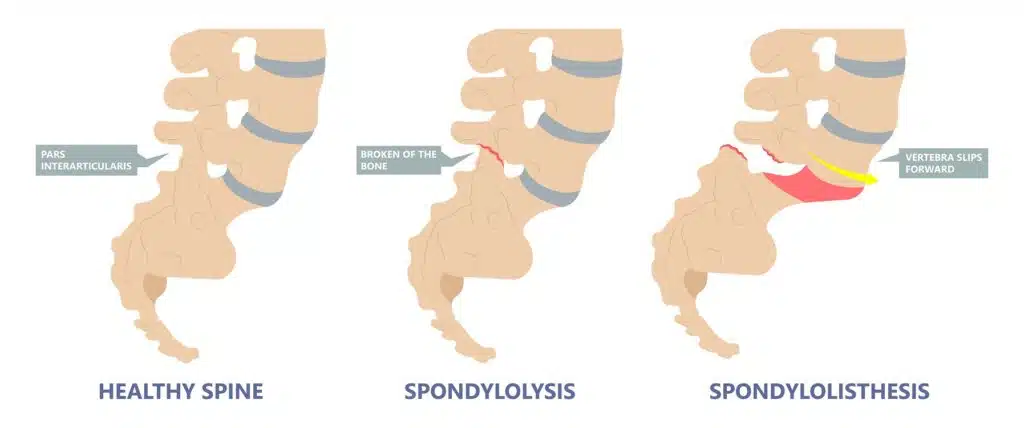

Spondylolisthesis vs. Spondylolysis

Spondylolysis (pronounced spahn-duh-loll-iss-us) and spondylolisthesis are different conditions of the spine, though they're sometimes related. Both conditions cause pain in your lower back .

Spondylolysis is a weakness or small fracture (crack) in one of your vertebrae. This usually affects your lower back, but it can also happen in the middle of your back or your neck. It's most often found in kids and teens, especially those involved in sports that repeatedly overstretch the lower spine, like football or gymnastics.

It's not uncommon for people with spondylolysis to also have spondylolisthesis. That's because the weakness or fracture in your vertebra may cause it to move out of place.

Types of Spondylolisthesis

Doctors divide this condition into six main types, determined by cause.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis: This is the most common type. As people age, the disks that cushion vertebrae can become worn, dry out, and get thinner. This makes it easier for the vertebra to slip out of place.

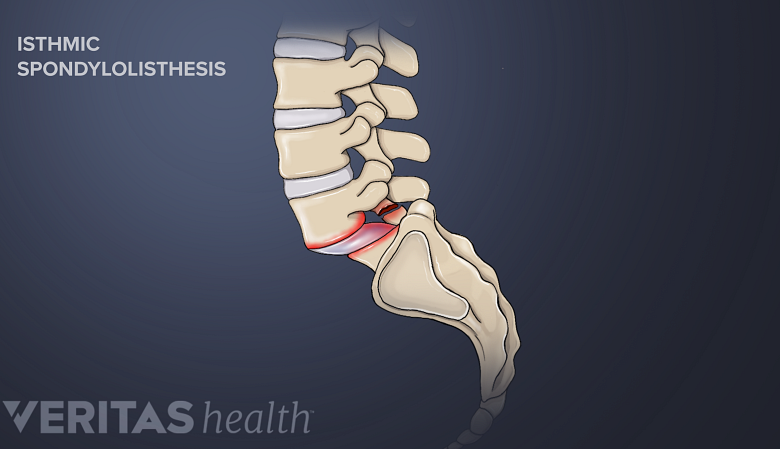

Isthmic spondylolisthesis: This type is caused by spondylosis. A crack in the vertebra can lead it to slip backward, forward, or over a bone below. It may affect kids and teens who do gymnastics, do weightlifting, or play football because they repeatedly overextend their lower backs. But it also sometimes happens when you're born with vertebrae whose bone is thinner than usual.

Congenital spondylolisthesis: Also known as dysplastic spondylolisthesis, this happens when your vertebrae are aligned incorrectly due to a birth defect.

Traumatic spondylolisthesis: In this type, an injury (trauma) to the spine causes the vertebra to move out of place.

Pathological spondylolisthesis: This type is caused by another spine condition, such as osteoporosis or a spinal tumor.

Postsurgical spondylolisthesis: Also called iatrogenic spondylolisthesis, this happens when a vertebra slips out of place after spinal surgery.

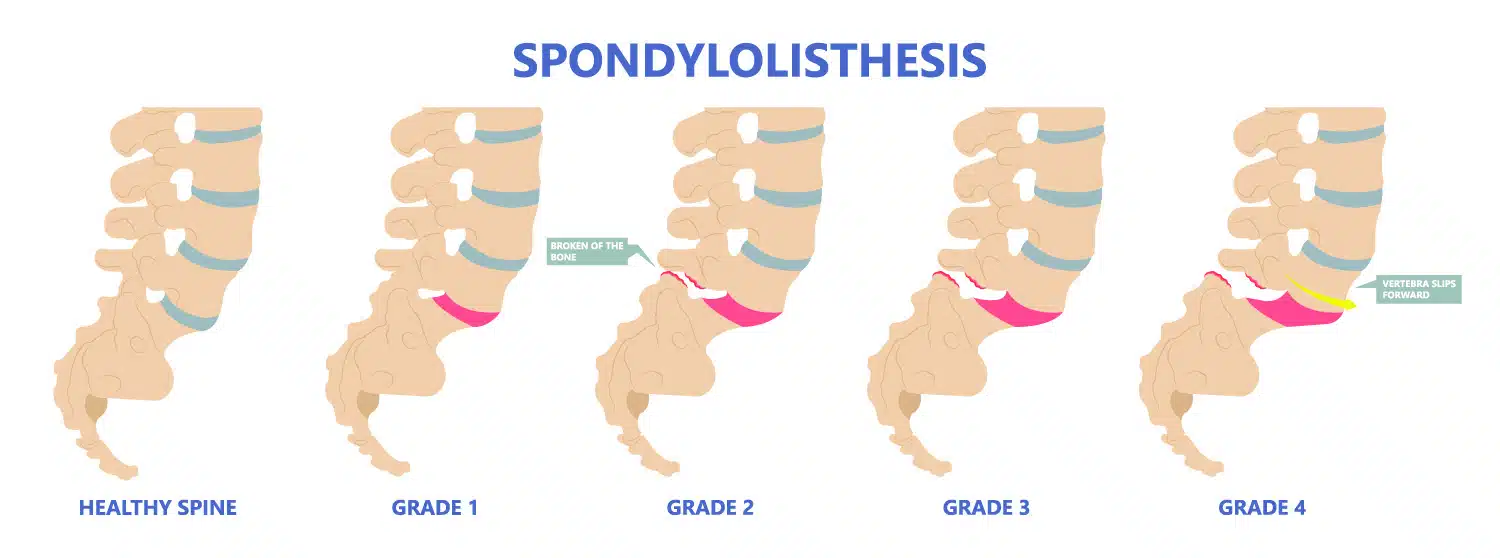

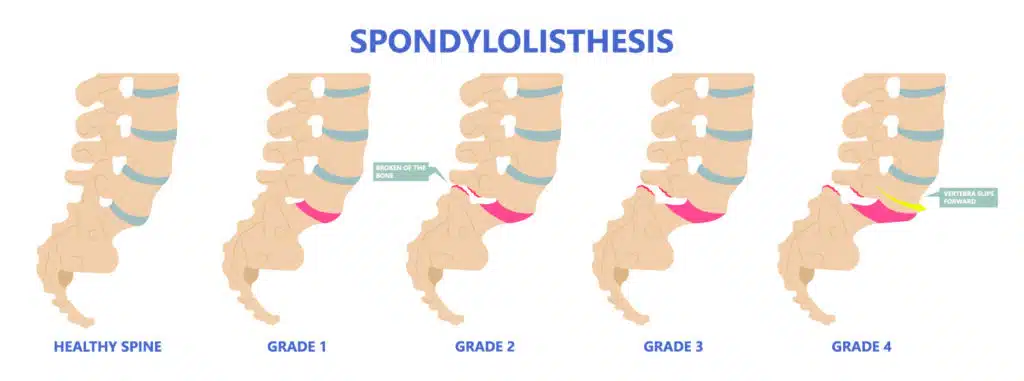

Grades of Spondylolisthesis

Your doctor may give your spondylolisthesis a grade based on how serious it is. The most common grading system is called Meyerding's classification and includes:

- Grade I : The most common grade, this is defined as 1%-25% slippage of the vertebra

- Grade II : Up to 50% slippage of the vertebra

- Grade III : Up to 75% slippage

- Grade IV : 76%-100% slippage

- Grade V : More than 100% slippage, also known as spondyloptosis

Grades I and II are considered low grade. Grades III and up are considered high grade.

Spondylolisthesis Causes and Risk Factors

Causes of spondylolisthesis include:

- Wear and tear with age

- Birth defects

- Spondylolysis

- Injury to the spine

- Another condition such as a spinal tumor or osteoporosis

- Spinal surgery

You're more likely to get this condition if you:

- Take part in sports that put stress on your spine

- Were born with thinner areas of vertebrae that are prone to breaking and slipping

- Are 50 or older

- Have a degenerative spinal condition

Spondylolisthesis Diagnosis

If your doctor thinks you might have this condition, they'll ask about your symptoms and run imaging tests to see if a vertebra is out of place. These tests may include:

These tests can also help your doctor determine a grade for your spondylolisthesis.

Spondylolisthesis Treatments

The treatment you'll need depends on what grade of spondylolisthesis you have, as well as your age, symptoms, and your medical history. Low grade can usually be treated with physical therapy or medications. With high grade, you may need surgery, especially if you're in a lot of pain.

Nonsurgical treatment options include:

- Rest : You may need to take some time off from sports and other vigorous activities.

- Medications : Your doctor may recommend over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medicines to relieve your pain, such as ibuprofen or naproxen.

- Injections : Steroid shots in the area where you have pain can bring relief.

- Physical therapy : Daily exercises that stretch and strengthen your supportive abdominal and lower back muscles can lower your pain.

- Braces : For children with fractures in the vertebrae (spondylolysis), a back brace can restrict movement so the fractures can heal.

Spondylolisthesis Surgery

If you have high-grade spondylolisthesis or if you still have serious pain and disability after nonsurgical treatments, you may need surgery. This usually means spinal decompression, often along with spinal fusion.

Spinal surgery is always done under general anesthesia , which means you're asleep during the operation.

Spinal decompression: Decompression lessens the pressure on the nerves in your spine to relieve pain. There are several techniques your surgeon can use to give your nerves more room. They may remove bone from your spine, take out part or all of a disk, or make the opening in your spinal canal larger. Your surgeon might need to use all these methods during your surgery.

Spinal fusion: In spinal fusion, the doctor joins, or fuses, the affected vertebrae together to prevent them from slipping again. After this surgery, you may have a bit less flexibility in your spine.

Pars repair: This surgery repairs fractures in the vertebrae using small wires or screws. Sometimes, a bone graft is used to reinforce the fracture so it can heal better.

After spinal surgery, you'll likely need to stay in the hospital for at least a day. Most people can go home within a week. You may be able to stand or even walk the day after the operation. You may go home with pain medication to ensure that your recovery is as easy as possible.

You'll need to limit physical activity for 8-10 weeks after your surgery so your spine can heal. But you should still move around and even walk every day. This can make your recovery go faster and help keep complications at bay.

Around 10-12 weeks after your surgery, you'll start physical therapy to stretch and strengthen your muscles and help you move more easily. Ideally, you should have physical therapy for a year.

For the first year after your surgery, you'll need to see your surgeon about every 3 months. You'll likely have X-rays taken at these follow-ups to make sure your spine is healing well.

Spondylolisthesis Complications

Serious spondylolisthesis sometimes leads to another condition called cauda equina syndrome . This is a serious condition in which nerve roots in part of your lower back called the cauda equina get compressed. It can cause you to lose feeling in your legs. It also can affect your bladder.

This is a medical emergency. If left untreated, cauda equina syndrome can lead to a loss of bladder control and paralysis.

See your doctor if you:

- Have trouble controlling your bladder or bowels

- Notice numbness or a strange sensation between your legs or on your buttocks, inner thighs, backs of your legs, feet, or heels

- Have pain or weakness in a leg or both legs that may cause stumbling

The symptoms may come on slowly and vary in how serious they are.

Spondylolisthesis Outlook

For most people, rest and nonsurgical treatments bring long-term relief within several weeks. But sometimes, spondylolisthesis comes back again after treatment. This happens more often when it was a higher grade.

If you've had surgery, you'll most likely do well afterward. Most people get back to normal activities within a few months. But your spine may not be as flexible as it was before.

Spondylolisthesis is when one of your vertebrae moves out of place. This sometimes leads to back pain and other symptoms. It can be usually treated with rest, medication, and/or physical therapy. But serious cases may require surgery.

Spondylolisthesis FAQs

What is the main cause of spondylolisthesis?

In adults, it most often happens when cartilage and bones in the spine become worn from conditions such as arthritis. It's more common in people age 50 and older. In kids and teens, the most common causes are either a spinal birth defect or injury to the spine.

Is spondylolisthesis a serious condition?

For most people, it's not serious. Many people have few symptoms or no symptoms at all. It's only a problem when it causes pain or limits your ability to move. If that happens, you'll need to see a doctor for treatment.

Top doctors in ,

Find more top doctors on, related links.

- Back Pain News

- Back Pain Reference

- Back Pain Slideshows

- Back Pain Quizzes

- Back Pain Videos

- Back Pain Medications

- Find a Neurologist

- Find a Pain Medicine Specialist

- WebMDRx Savings Card

- Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Drug Interaction Checker

- Osteoporosis

- Pain Management

- Pill Identifier

- Second Opinions

- SI Joint Pain

- More Related Topics

Spondylolisthesis: Definition, Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

by Dave Harrison, MD • Last updated November 26, 2022

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

What is Spondylolisthesis?

The spine is comprised of 33 bones, called vertebra , stacked on top of each other interspaced by discs . Spondylolisthesis is a condition where one vertebra slips forward or backwards relative to the vertebra below. More specifically, retrolisthesis is when the vertebra slips posteriorly or backwards, and anterolisthesis is when the vertebra slips anteriorly or forward.

Spondylosis vs Spondylolisthesis

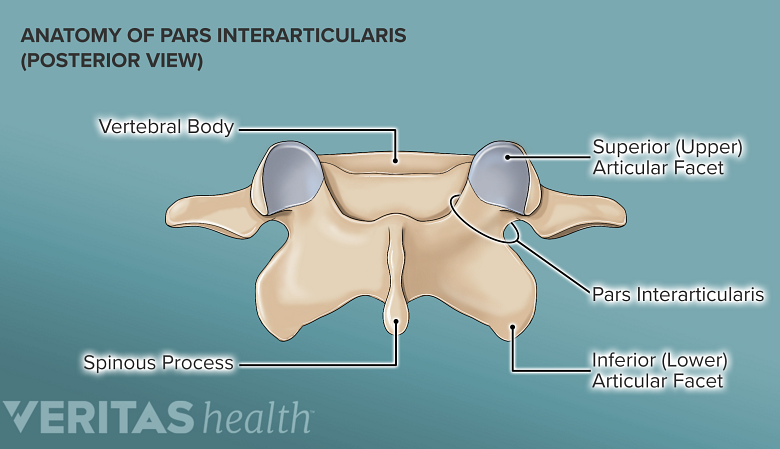

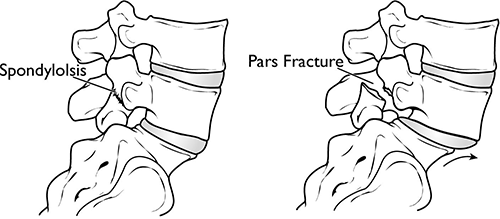

Spondylosis and Spondylolisthesis are different conditions. They can be related but are not the same. Spondylosis refers to a fracture of a small bone, called the pars interarticularis, which connects the facet joint of the vertebra to the one below. This may lead to instability and ultimately slippage of the vertebra. Spondylolisthesis, on the other hand, refers to slippage of the vertebra in relation to the one below.

Types and Causes of Spondylolisthesis

There are several types of spondylolisthesis, often classified by their underlying cause:

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

Degenerative spondylolisthesis is the most common cause, and is due to general wear and tear on the spine. Overtime, the bones and ligaments which hold the spine together may become weak and unstable.

Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

Isthmic spondylolisthesis is the result of another condition, called “ spondylosis “. Spondylosis refers to a fracture of a small bone, called the pars interarticularis, which connects the facet joint of the vertebra to the one below. If this interconnecting bone is broken, it can lead to slippage of the vertebra. This can sometimes occur during childhood or adolsence but go unnoticed until adulthood when degenerative changes cause worsening slippage.

Congenital Spondylolisthesis

Congenital spondylolisthesis occurs when the bones do not form correctly during fetal development

Traumatic Spondylolisthesis

Traumatic spondylolisthesis is the result of an injury such as a motor vehicle crash

Pathologic Spondyloslisthesis

Pathologic spondylolisthesis is when other disorders weaken the points of attachment in the spine. This includes osteoporosis, tumors, or infection that affect the bones and ligaments causing them to slip.

Iatrogenic Spondylolisthesis

Iatrogenic spondylolisthesis is the result of a prior surgery. Some operations of the spine, such as a laminectomy, may lead to instability. This can cause the vertebra to slip post operatively.

Spondylolisthesis Grades

Spondylolisthesis is classified based on the degree of slippage relative to the vertebra below

- Grade 1 : 1 – 25 % forward slip. This degree of slippage is usually asymptomatic.

- Grade 2: 26 – 50 % forward slip. May cause mild symptoms such as stiffness and pain in your lower back after physical activity, but it’s not severe enough to affect your everyday activities.

- Grade 3 : 51 – 75 % forward slip. May cause moderate symptoms such as pain after physical activity or sitting for long periods.

- Grade 4: 76 – 99% forward slip. May cause moderate to severe symptoms.

- Grade 5: Is when the vertebra has slipped completely of the spinal column. This is a severe condition known as “spondyloptysis”.

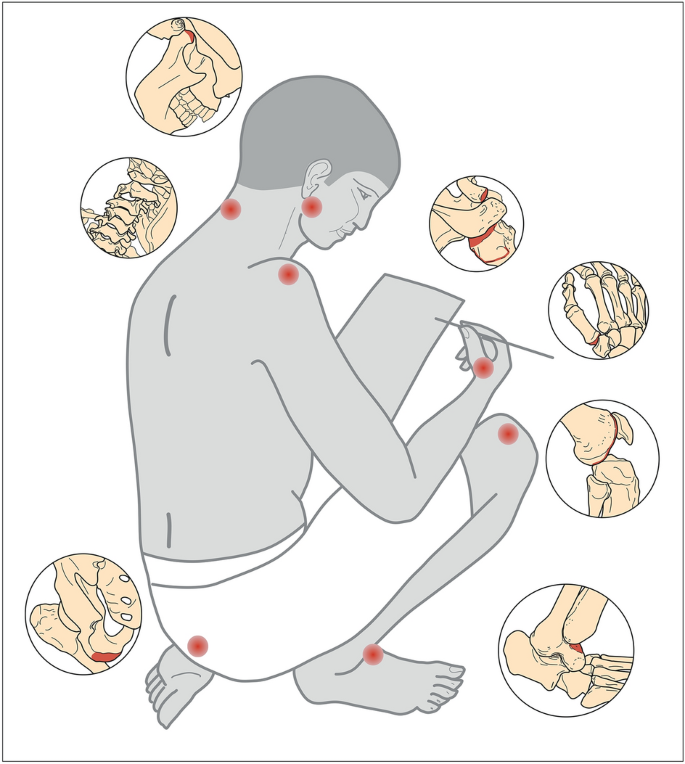

Symptoms of Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis can cause compression of spinal nerves and in severe cases, the spinal cord. The symptoms will depend on which vertebra is affected.

Cervical Spondylolisthesis (neck)

- Arm numbness or tingling

- Arm weakness

Lumbar Spondylolisthesis (low back)

- Buttock pain

- Leg numbness or tingling

- Leg weakness

Diagnosing Spondylolisthesis

Your doctor may order imaging tests to confirm the diagnosis and determine the severity of your spondylolisthesis. The most common imaging tests used include:

- X-rays : X-rays can show the alignment of the vertebrae and any signs of slippage.

- CT scan: A CT scan can provide detailed images of the bones and soft tissues in your back, allowing your doctor to see any damage or abnormalities.

- MRI: An MRI can show the spinal cord and nerves, as well as any herniated discs or other soft tissue abnormalities.

Treatments for Spondylolisthesis

Medications.

For those experiencing pain, oral medications are first line treatments. This includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or in severe cases opioids or muscle relaxants (with extreme caution). Topical medications such as lidocaine patches are also sometimes used.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy can help improve mobility and strengthen muscles around your spine to stabilize your neck and lower back. You may also receive stretching exercises to improve flexibility and balance exercises to improve coordination.

Surgery is reserved for severe cases of spondylolisthesis in which there is a high degree of instability and symptoms of nerve compression.

In these cases a spinal fusion may be necessary. This surgery joins two or more vertebra together using rods and screws, in order to improve stability.

Reference s

- Alfieri A, Gazzeri R, Prell J, Röllinghoff M. The current management of lumbar spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Sci. 2013 Jun;57(2):103-13. PMID: 23676859.

- Stillerman CB, Schneider JH, Gruen JP. Evaluation and management of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Neurosurg. 1993;40:384-415. PMID: 8111991.

About the Author

Dave Harrison, MD

Dr. Harrison is a board certified Emergency Physician with a part time appointment at San Francisco General Medical Center and is an Assistant Clinical Professor-Volunteer at the UCSF School of Medicine. Dr. Harrison attended medical school at Tufts University and completed his Emergency Medicine residency at the University of Southern California. Dr. Harrison manages the editorial process for SpineInfo.com.

- skip to Cookie Notice

- skip to Main Navigation

- skip to Main Content

- skip to Footer

- Find a Doctor

- Find a Location

- Appointments & Referrals

- Patient Gateway

- Español

- Leadership Team

- Quality & Safety

- Equity & Inclusion

- Community Health

- Education & Training

- Centers & Departments

- Browse Treatments

- Browse Conditions A-Z

- View All Centers & Departments

- Clinical Trials

- Cancer Clinical Trials

- Cancer Center

- Digestive Healthcare Center

- Heart Center

- Mass General for Children

- Neuroscience

Orthopaedic Surgery

- Information for Visitors

- Maps & Directions

- Parking & Shuttles

- Services & Amenities

- Accessibility

- Visiting Boston

- International Patients

- Medical Records

- Billing, Insurance & Financial Assistance

- Privacy & Security

- Patient Experience

- Explore Our Laboratories

- Industry Collaborations

- Research & Innovation News

- About the Research Institute

- Innovation Programs

- Education & Community Outreach

- Support Our Research

- Find a Researcher

- News & Events

- Ways to Give

- Patient Rights & Advocacy

- Website Terms of Use

- Apollo (Intranet)

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- See us on LinkedIn

- Print this page

Spondylolysis & Spondylolisthesis

Orthopaedic spine center.

- 617-724-8636

Contact Information

Phone: 617-724-8636 Fax: 617-726-7587

Our spine team sees patients at these locations:

Mass General - Boston 55 Fruit Street Yawkey Center for Outpatient Care, Suite 3A Boston, MA 02114

Orthopaedics at Mass General Brigham Healthcare Center (Waltham) 52 Second Avenue Building 52, 1st Floor, Suite 1150 Waltham, MA 02451

Newton-Wellesley Spine Center 159 Wells Avenue Newton, MA 02459

Mass General Brigham Healthcare Center (Danvers) 102-104 Endicott Street Danvers, MA 01923

Mass General Brigham Healthcare Center (20 Patriot Place, Foxborough) 20 Patriot Place Foxborough, MA 01923

Explore Spondylolysis & Spondylolisthesis

What is spondylolysis.

Spondylolysis is a condition when the fifth (last) vertebra of the lumbar (lower) spine is fractured.

What is Spondylolisthesis?

Spondylolisthesis is a condition when the spondylolysis (fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra) weakens the bone so much that it cannot maintain proper position and vertebrae start to shift out of place.

Who is affected by Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis?

Adolescent athletes, especially football players, gymnasts and weight lifters, are prone to spondylolysis. Sports that require athletes to put a great deal of stress on their lower backs, and athletes that are required to constantly overextend their back are more prone to spondylolysis.

Symptoms of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis often do not present right away, and when they do present, it can feel like muscle strain across the lower back. Spondylolisthesis can also cause muscle spasms.

After taking a medical history and performing a thorough physical exam, your doctor probably will request that you have an x-ray, CT scan or an MRI scan, which will be able to show the spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

Nonsurgical treatment

For most people with spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis, your doctor will try nonsurgical treatments first. Resting and taking a break from any sports or other physical activities is a good idea to give the fracture time to heal. Your doctor also might recommend physical therapy and exercise to strengthen muscles in your back and abdomen, which can help stabilize your spine. Anti-inflammatory medications (like ibuprofen) may be recommended to reduce pain, discomfort and inflammation.

In more severe cases, a back brace or back support might be used to stabilize the spine. And epidural steroid injections can help reduce inflammation and pain. The steroid is injected into the space surrounding the spine.

Surgical treatment

Surgery may be recommended if none of the nonsurgical treatment options help keep the pain at a tolerable level. Surgery for spondylolisthesis typically is a spinal fusion and sometimes involves screws and rods to hold everything together as the fusion heals. Another type of surgery that is used sometimes is called a vertebral body replacement.

Meet our Spine Team

Contact the orthopaedic spine center..

Have questions about spondylolysis & spondylolisthesis? Get in touch.

Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is slippage of a lumbar vertebra in relation to the vertebra below it. Anterior slippage (anterolisthesis) is more common than posterior slippage (retrolisthesis). Spondylolisthesis has multiple causes. It can occur anywhere in the spine and is most common in the lumbar and cervical regions. Lumbar spondylolisthesis may be asymptomatic or cause pain when walking or standing for a long time. Treatment is symptomatic and includes physical therapy with lumbar stabilization.

There are five types of spondylolisthesis, categorized based on the etiology:

Type I, congenital: caused by agenesis of superior articular facet

Type II, isthmic: caused by a defect in the pars interarticularis (spondylolysis)

Type III, degenerative: caused by articular degeneration as occurs in conjunction with osteoarthritis

Type IV, traumatic: caused by fracture, dislocation, or other injury

Type V, pathologic: caused by infection, cancer, or other bony abnormalities

Spondylolisthesis usually involves the L3-L4, L4-L5, or most commonly the L5-S1 vertebrae.

Types II (isthmic) and III (degenerative) are the most common.

Type II often occurs in adolescents or young adults who are athletes and who have had only minimal trauma; the cause is a weakening of lumbar posterior elements by a defect in the pars interarticularis (spondylolysis). In most younger patients, the defect results from an overuse injury or stress fracture with the L5 pars being the most common level.

Type III (degenerative) can occur in patients who are > 60 and have osteoarthritis ; this form is six times more common in women than men.

Anterolisthesis requires bilateral defects for type II spondylolisthesis. For type III (degenerative) there is no defect in the bone.

ZEPHYR/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Spondylolisthesis is graded according to the percentage of vertebral body length that one vertebra subluxes over the adjacent vertebra:

Grade I: 0 to 25%

Grade II: 25 to 50%

Grade III: 50 to 75%

Grade IV: 75 to 100%

Spondylolisthesis is evident on plain lumbar x-rays. The lateral view is usually used for grading. Flexion and extension views may be done to check for increased angulation or forward movement.

Mild to moderate spondylolisthesis (anterolisthesis of ≤ 50%), particularly in the young, may cause little or no pain. Spondylolisthesis can predispose to later development of foraminal stenosis . Spondylolisthesis is generally stable over time (ie, permanent and limited in degree).

Treatment of spondylolisthesis is usually symptomatic. Physical therapy with lumbar stabilization exercises may be helpful.

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Cookie Preferences

Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Spondylolisthesis: Individualized approach for optimal outcomes

March 27, 2021

High-grade spondylolisthesis has diverse etiologies and presentations, as well as multiple treatment options. Mayo Clinic spinal surgeons tailor treatment to the individual patient to maximize outcomes and avoid future revision surgery.

"We treat many patients who had surgery elsewhere that used inadequate sacral and pelvic fixation. Inadequate fixation leads to higher rates of failed fusion, which requires more-complex surgery to repair," says Jeremy L. Fogelson, M.D. , a neurosurgeon specializing in spine care at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. "When we perform an initial surgery for spondylolisthesis, we take a safe but aggressive approach to fixation if needed."

Treating complex curvature

Preoperative X-ray shows severe spinal curvature in a 30-year-old woman with high-grade congenital spondylolisthesis. She presented at Mayo Clinic with intractable back pain and leg pain, which did not resolve with nonoperative treatments.

Successful fusion

Postoperative X-ray shows treatment with a fusion from L4 to S1, including pelvic fixation with S2 alar-iliac screws, and fixation into L5 with S1 to L5 transdiscal screws. Her pain was resolved and the fusion successfully healed, with eventual removal of the iliac screws.

As a high-volume center, Mayo Clinic regularly sees children and adults with congenital or degenerative spondylolisthesis. Full-body electro-optical system (EOS) imaging, a low-radiation X-ray technology, is routinely used for diagnosis. Mayo Clinic, which has a long history of imaging expertise, was among the first centers in the United States to offer EOS .

" EOS allows us to evaluate the entire spine as well as whole-body and leg alignment," Dr. Fogelson says. "We can factor in all features — cervical spine misalignment, bent knees or hips, leg-length discrepancy — into our treatment plan."

If surgery is needed, Mayo Clinic bases the approach not on a surgeon's preference but on the patient's condition. "We are able to perform the fusion posteriorly, anteriorly or laterally, or in some combination, depending on the individual patient's needs," Dr. Fogelson says. Less invasive surgical techniques also can be used.

In addition to neurosurgeons, Mayo Clinic's spondylolisthesis care team includes specialists in neurology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and pain medicine. "We work from the beginning of each case with our colleagues in those specialties, to make sure we've maximized any nonoperative treatment possibilities," Dr. Fogelson says.

If surgery is needed, Mayo Clinic's neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons routinely collaborate on complex spinal procedures. 3D spinal navigation can be used to guide the placement of spinal hardware, and intraoperative CT checks screw placement. All members of the care team have spinal deformity expertise, including nurses and anesthesiologists dedicated to caring for patients during complex spinal procedures.

Mayo Clinic also works to learn more about optimal surgical approaches to spondylolisthesis. Within the field of spinal surgery, iliac fixation has sometimes been avoided, due to concerns about screws loosening over time and eventually requiring surgical removal related to pain. To investigate one aspect of this issue, Mayo Clinic is participating in a multicenter clinical trial comparing the outcomes of patients having multilevel lumbar fusion with or without simultaneous sacroiliac joint fusion.

Postoperative rehabilitation is an important aspect of treatment. At Mayo Clinic, rehabilitation care is provided by specialists in pain medicine and in physical medicine and rehabilitation, as well as physical and occupational therapists who routinely work with people who have had spinal deformity surgery.

A commitment to rehabilitation, combined with skilled surgical techniques, allows for positive results from spondylolisthesis surgery. "People facing lumbar fixation surgery often worry about loss of motion in the spine and further disability," Dr. Fogelson says. "But once the pain generator is fixed, most patients gain function. Spinal fusion can have very good outcomes when performed well and for the right reasons."

For more information

SI-BONE Inc. SI Joint Stabilization in Long Fusion to the Pelvis (SILVIA). ClinicalTrials.gov.

Receive Mayo Clinic news in your inbox.

- Medical Professionals

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- See All Locations

- Primary Care

- Urgent Care Facilities

- Emergency Rooms

- Surgery Centers

- Medical Offices

- Imaging Facilities

- Browse All Specialties

- Diabetes & Endocrinology

- Digestive & Liver Diseases

- Ear, Nose & Throat

- General Surgery

- Neurology & Neurosurgery

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Orthopaedics

- Pain Medicine

- Pediatrics at Guerin Children’s

- Urgent Care

- Medical Records Request

- Insurance & Billing

- Pay Your Bill

- Advanced Healthcare Directive

- Initiate a Request

- Help Paying Your Bill

Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is a displacement of a vertebra in which the bone slides out of its proper position onto the bone below it. Most often, this displacement occurs following a break or fracture.

Surgery may be necessary to correct the condition if too much movement occurs and the bones begin to press on nerves.

Other complications may include:

- Chronic back pain

- Sensation changes

- Weakness of the legs

- Temporary or permanent damage of spinal nerve roots

- Loss of bladder control

When a vertebra slips out of proper alignment, discs can be damaged. To surgically correct this condition, a spinal surgeon removes the damaged disc. The slipped vertebra is then brought back into line, relieving pressure on the spinal nerve.

Types of spondylolisthesis include:

- Dysplastic spondylolisthesis , caused by a defect in part of the vertebra

- Isthmic spondylolisthesis , may be caused by repetitive trauma and is more common in athletes exposed to hyperextension motions

- Degenerative spondylolisthesis , occurs with cartilage degeneration because of arthritic changes in the joints

- Traumatic spondylolisthesis , caused by a fracture of the pedicle, lamina or facet joints as a result of direct trauma or injury to the vertebrae

- Pathologic spondylolisthesis , caused by a bone defect or abnormality, such as a tumor

Symptoms may vary from mild to severe. In some cases, there may be no symptoms at all.

Spondylolisthesis can lead to increased lordosis (also called swayback), and in later stages may result in kyphosis, or round back, as the upper spine falls off the lower.

Symptoms may include:

- Lower back pain

- Muscle tightness (tight hamstring muscle)

- Pain, numbness or tingling in the thighs and buttocks

- Tenderness in the area of the vertebra that is out of place

- Weakness in the legs

- Stiffness, causing changes in posture and gait

- A semi-kyphotic posture (leaning forward)

- A waddling gate in advanced cases

- Lower-back pain along the sciatic nerve

- Changes in bladder function

Spondylolisthesis may also produce a slipping sensation when moving into an upright position and pain when sitting and trying to stand.

Spondylolisthesis may appear in children as the result of a birth defect or sudden injury, typically occurring between the fifth bone in the lower back (lumbar vertebra) and the first bone in the sacrum (pelvis).

In adults, spondylolisthesis is the result of abnormal wear on the cartilage and bones from conditions such as arthritis , trauma from an accident or injury, or the result of a fracture, tumor or bone abnormality.

Sports that place a great deal of stress on bones may cause additional deterioration, fractures and bone disease, which may cause the bones of the spine to become weak and shift out of place.

A simple X-ray of the back will show any cracks, fractures or vertebrae slippage that are the signs of spondylolisthesis.

A CT scan or an MRI may be used to further diagnose the extent of the damage and possible treatments.

Treatment for spondylolisthesis will depend on the severity of the vertebra shift. Stretching and exercise may improve some cases as back muscles strengthen.

Non-invasive treatments include:

- Heat/Ice application

- Pain medicine (Tylenol and/or NSAIDS)

- Physical therapy

- Epidural injections

Surgery may be needed to fuse the shifted vertebrae if the patient has:

- Severe pain that does not get better with treatment

- A severe shift of a spine bone

- Weakness of muscles in a leg or both legs

Surgical process realigns the vertebrae, fixing them in place with a small rod that is attached with a pedicle screw, adding stability to the spine with or without the addition to an interbody (bone graft or cage) placed between the vertebra from the side or front.

Choose a doctor and schedule an appointment.

Get the care you need from world-class medical providers working with advanced technology.

Cedars-Sinai has a range of comprehensive treatment options.

(1-800-233-2771)

Available 7 days a week, 6 am - 9 pm PT

Expert Care for Life™ Starts Here

Looking for a physician.

- Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

By: Adaku Nwachuku, DO, Physiatrist

Peer-Reviewed

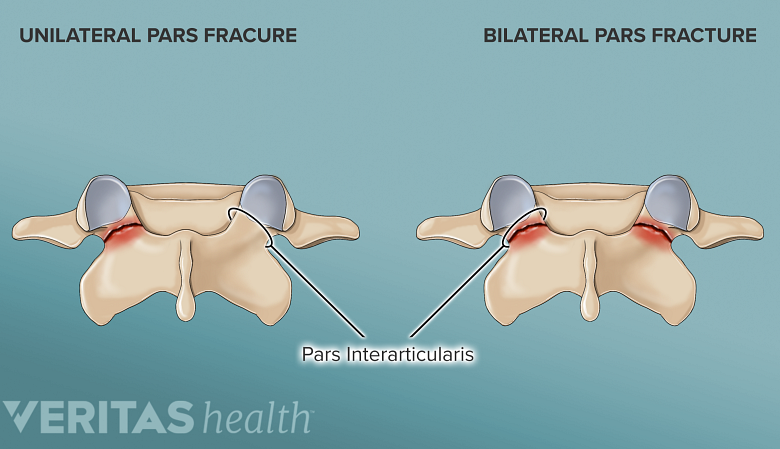

Spondylolysis refers to a defect in the short, flat strip of bone called pars interarticularis (or pars). The pars is located at the back of the spine and forms a bridge (or isthmus) between the upper and lower joint surfaces of each facet of a vertebra (spinal bone).

Show Transcript

Lumbar spondylolysis is a condition in the lower back where there is a defect or fracture in the part of the vertebra known as the pars interarticularis. The pars interarticularis, also known as the isthmus, is a segment of bone that connects the facet joints at the back of the spine. It is a small, thin part of the lamina that has a poor blood supply, which makes it susceptible to stress fractures.

Fractures of the pars interarticularis, known as spondylolysis, usually occur at the L5-S1 level,and rarely at L4-L5 or higher. They can occur on one side of the vertebra or on both.

Spondylolysis usually occurs in children between the ages of 5 and 7. It is sometimes called the “gymnastics fracture” because it is associated with sports that require a lot of bending backward. It is thought that repetitive stress on the spine has a cumulative effect that causes the pars interarticularis to break.

Spondylolysis sometimes causes spondylolisthesis, which is when one vertebra slips forward on the vertebra below it.

Symptoms include a deep ache in the lower back, pain that is worse with movement, and tightness in the hamstrings. If the vertebral slippage is severe, nerve roots can be compressed.

However, most people do not experience symptoms from lumbar spondylolysis at all, and those who do tend to develop problems in adulthood or in adolescence.

Spondylolisthesis is a condition where a vertebra slips forward over the vertebra below it. When spondylolisthesis occurs due to spondylolysis, the condition is called isthmic spondylolisthesis .

Spondylolysis and isthmic spondylolisthesis rarely cause pain, but when symptoms do occur, they typically affect children and adolescents. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/ , 2 Studnicka K, Ampat G. Lumbosacral Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2022 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560679/ , 3 Mikhael MM, Shapiro GS, Wang JC. High-grade adult isthmic L5-s1 spondylolisthesis: a report of intraoperative slip progression treated with surgical reduction and posterior instrumented fusion. Global Spine J. 2012;2(2):119-124. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1307257 Spondylolysis occurs in the lumbar spine (low back) and primarily affects the L5 vertebra. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

In This Article:

- Symptoms and Diagnosis of Spondylolysis

- Spondylolysis Treatment

Lumbar Spondylolysis Video

Understanding spondylolysis.

A stress fracture of the pars can occur on one side or both sides.

Spondylolysis occurs when a stress fracture in the pars does not fuse or heal completely as a part of the bone’s natural healing process, leaving the bone permanently split into two pieces. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Research shows that the pars is subjected to the greatest force compared to any other structure in the lumbar spine, making it vulnerable to stress fractures. In susceptible individuals, the pars may fracture, heal, and fracture again—repeatedly. 4 Burton MR, Dowling TJ, Mesfin FB. Isthmic Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441846/

The fracture can involve the right pars, left pars, or both. Pars fractures involving both sides (also called bilateral fractures) are more common than one-sided (or unilateral) fractures. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

A stress fracture of the pars can occur as a result of 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/ , 4 Burton MR, Dowling TJ, Mesfin FB. Isthmic Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441846/ :

- Hereditary causes that make the pars more likely to fracture

- Weak bone tissue in the pars that is present at birth (congenital)

- Abnormally long pars bone

- Sudden trauma to the spine

The condition is more common in genetically susceptible children and adolescents who frequently participate in activities or sports that involve repeated forward bending and rotation of the spine. These actions, coupled with the genetic defect or weak bone tissue, cause excessive microtrauma to the growing, immature pars interarticularis, leading to a fracture. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Classic Symptoms and Signs of Spondylolysis

A dull ache in the lower back and buttock area is a common symptom of spondylolysis.

Spondylolysis pain feels like a dull ache that spans across the low back area. The buttocks and the back of the thigh may also feel sore, and the muscles in these areas tend to feel stiff or tight. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Bending backward or performing twisting movements increases spondylolysis pain in the low back. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

If there is associated isthmic spondylolisthesis, the symptoms may differ and include nerve pain, tingling, and leg weakness based on the severity of the vertebral slippage and spinal nerve compression. 4 Burton MR, Dowling TJ, Mesfin FB. Isthmic Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441846/

See Isthmic Spondylolisthesis Symptoms

Spondylolysis Causes and Risk Factors

Activities and sports that have a high impact on the spine may cause pars fractures.

In addition to those with high genetic susceptibility, the following individuals are also likely to be affected by spondylolysis 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/ :

- Males (spondylolysis is twice as likely to occur in males than females)

- Children who are diagnosed with abnormal bone and nerve conditions such as spina bifida occulta, Marfan syndrome, or osteogenesis imperfecta

- Adolescents who are actively involved in high-impact sports

- Adults diagnosed with spinal osteopetrosis (weak, brittle bone)

Spondylolysis is usually identified during adolescence, around the age of 15, when symptoms start to manifest. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Specific sports that increase the likelihood of a pars fracture are 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/ :

- Gymnastics and weightlifting

- Football, soccer, and rugby

- Basketball and volleyball

- Swimming (butterfly and breaststroke)

Approximately 4% of 6-year-old children and 6% of teenagers aged 14 have this condition. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Progression of Spondylolysis to Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

When spondylolysis causes the vertebra to slip forward, it results in spondylolisthesis.

When a bilateral stress fracture of the pars interarticularis does not heal, the affected vertebra becomes incapable of bearing the heavy loads of the spine, causing the upper and lower surfaces of the facet joints to disconnect and separate. This separation makes the vertebra lose connection with the rest of the spine, resulting in isthmic spondylolisthesis – a forward slippage of the vertebral body, typically in a horizontal pattern. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Spondylolysis typically impacts the L5 vertebra in approximately 90% of cases, and if the condition progresses, L5 slips over S1. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

If only one of the pars interarticularis bone gets fractured (unilateral spondylolysis), the condition does not progress to isthmic spondylolisthesis. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

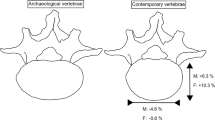

While spondylolysis is more common in adolescent males, the progression to isthmic spondylolisthesis is more common in adolescent females. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Spondylolisthesis can also occur due to degenerative changes in the spine ( degenerative spondylolisthesis ), trauma (traumatic spondylolisthesis), or bone diseases, such as spinal cancer (pathologic spondylolisthesis).

Why Spondylolysis Is More Common in Adolescents

The bone along the outer side of the upper joint surface of the facets has a small, rounded projection called the mammillary process. This bony projection serves as an attachment point for the thin strips of deep spinal multifidi muscles, which stabilize the facet joints and provide stability to the spine. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

The mammillary process is not completely formed until the age of 25, making the facet joint complex (which includes the pars) vulnerable to injury. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

A similar structure called the neural arch (an arch of bone at the back of a vertebra) also does not develop until the age of 25, contributing to the risk of spondylolysis and subsequent spondylolisthesis. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Progression to spondylolisthesis is less likely to occur in adults compared to adolescents. 5 Gagnet P, Kern K, Andrews K, Elgafy H, Ebraheim N. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: A review of the literature. J Orthop. 2018 Mar 17;15(2):404-407. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.03.008. PMID: 29881164; PMCID: PMC5990218.

The Course of Spondylolysis

Spondylolysis is not considered a serious condition and typically has an excellent long-term outlook when treated appropriately. For individuals with no symptoms, treatment, activity restriction, or other precautions are not needed. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

How long spondylolysis takes to heal

For symptomatic patients, complete healing generally occurs within 6 to 12 weeks of nonsurgical treatments. One-sided pars fractures heal sooner than bilateral fractures. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

In cases that have progressed to spondylolisthesis, the bone may not heal completely but the symptoms usually subside with treatment. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Return to work or play after spondylolysis

Over 75% of patients achieve complete relief from their symptoms with nonsurgical treatments. 1 , In adolescents, the healing process is more favorable, with approximately 92% of adolescent athletes returning to competitions after conservative treatment. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Surgery for spondylolysis is rare and when considered, about 90% of young athletes have a successful return to sports activities. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Potential complications of spondylolysis

While rare, if left untreated, spondylolysis may progress to spondylolisthesis and subsequent nerve or spinal cord damage if the vertebral slippage is severe. 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

Spondylolysis may also accelerate the progression of co-occurring degenerative spinal conditions, such as degenerative disc disease and spondylosis, potentially leading to severe spinal stenosis and lumbar radiculopathy . 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

When to See a Doctor for Spondylolysis

Progressive weakness and numbness in the legs may require immediate medical attention.

Certain red flags suggest potential complications or severe underlying issues associated with spondylolysis and must be evaluated immediately by a medical professional. These signs and symptoms include but are not limited to:

- Progressive neurological symptoms. Progressive weakness, numbness, or tingling in the legs, or feet may indicate severe nerve compression due to spondylolysis-related spinal instability.

- Unrelenting pain. Experiencing intense and unrelenting back pain, especially after a traumatic event or fall, indicates a more serious injury or fracture.

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction. Difficulty controlling bowel or bladder movements, or experiencing urinary or fecal incontinence, may indicate cauda equina syndrome , a rare but severe complication of spondylolysis that requires urgent medical attention.

- Sudden worsening of symptoms. If the existing symptoms suddenly intensify, it could indicate a significant progression of the condition or a related complication.

- Pain at rest or night pain. Pain that persists when resting or worsens at night might indicate a more severe underlying problem, such as a spinal tumor .

- Fever or signs of infection. Fever, chills, and signs of infection (redness, swelling, or a discharge) around the back area may suggest an infection in the spine , which requires urgent medical assessment and treatment.

Recognizing these red flag signs and symptoms is vital to ensure timely intervention and prevent potential complications associated with spondylolysis.

See When Back Pain May Be a Medical Emergency

Medical Professionals Who Treat Spondylolysis

If spondylolysis is suspected, it is advisable to consult with a qualified healthcare professional for a thorough evaluation and personalized treatment plan. Physiatrists (PM&R specialists), sports management specialists, orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, and chiropractors have specialized training in managing musculoskeletal disorders and can effectively treat spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.

- 1 McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Jan 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

- 2 Studnicka K, Ampat G. Lumbosacral Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2022 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560679/

- 3 Mikhael MM, Shapiro GS, Wang JC. High-grade adult isthmic L5-s1 spondylolisthesis: a report of intraoperative slip progression treated with surgical reduction and posterior instrumented fusion. Global Spine J. 2012;2(2):119-124. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1307257

- 4 Burton MR, Dowling TJ, Mesfin FB. Isthmic Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441846/

- 5 Gagnet P, Kern K, Andrews K, Elgafy H, Ebraheim N. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: A review of the literature. J Orthop. 2018 Mar 17;15(2):404-407. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.03.008. PMID: 29881164; PMCID: PMC5990218.

Dr. Adaku Nwachuku is a physiatrist with Privium Consultants, where she specializes in treating musculoskeletal and spine pain. Dr. Nwachuku has been published in the Oxford Handbook of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation as well as in several medical journals. She also coordinates and participates in medical missions to Nigeria.

- Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis "> Share on Facebook

- Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis "> Share on Pinterest

- Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis "> Share on X

- Subscribe to our newsletter

- Print this article

- Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis &body=https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/spondylolisthesis/spondylolysis-and-spondylolisthesis&subject= Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis "> Email this article

Editor’s Top Picks

Isthmic spondylolisthesis symptoms, spinal fusion surgery for isthmic spondylolisthesis, isthmic spondylolisthesis video, answers to common spondylosis questions, degenerative spondylolisthesis video.

Popular Videos

Sciatica Causes and Symptoms Video

Cervical Disc Replacement Surgery Video

Lower Back Strain Video

3 Gentle Stretches to Prevent Neck Pain Video

Undergoing a Spinal Fusion?

Learn how bone growth stimulation therapy can help your healing process

Sponsored by Orthofix

Health Information (Sponsored)

- Learn How Bone Growth Therapy Can Help You

- Don't Push Through the Pain: Contact the Experts at Cedars-Sinai

- Suffering from Lumbar Spinal Stenosis? Obtain Long Term Pain Relief

- Take the Chronic Pain Quiz

Utility Menu

- Request an Appointment

Popular Searches

- Adult Primary Care

Orthopedic Surgery

Spondylolisthesis.

Select your language:

In spondylolisthesis, one of the bones in your spine — called a vertebra — slips forward and out of place. This may occur anywhere along the spine, but is most common in the lower back (lumbar spine). In some people, this causes no symptoms at all. Others may have back and leg pain that ranges from mild to severe.

(Left) In spondylolysis, a fracture often occurs at the pars interarticularis. (Right) Because of the pars fracture, only the front part of the bone slips forward.

What are the different types of spondylolisthesis?

Many types of spondylolisthesis can affect adults. The two most common types are degenerative and spondylolytic. There are other less common types of spondylolisthesis, such as slippage caused by a recent, severe fracture or a tumor.

What is degenerative spondylolisthesis?

As we age, general wear and tear causes changes in the spine. Intervertebral discs begin to dry out and weaken. They lose height, become stiff, and begin to bulge. This disc degeneration is the start to both arthritis and degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS).

As arthritis develops, it weakens the joints and ligaments that hold your vertebrae in the proper position. The ligament along the back of your spine (ligamentum flavum) may begin to buckle. One of the vertebrae on either side of a worn, flattened disc can loosen and move forward over the vertebra below it. This can narrow the spinal canal and put pressure on the spinal cord. This narrowing of the spinal canal is called spinal stenosis and is a common problem in patients with DS.

Women are more likely than men to have DS, and it is more common in patients who are older than 50. A higher incidence has been noted in the African-American population.

What is spondylolytic spondylolisthesis?

One of the bones in your lower back can break and this can cause a vertebra to slip forward. The break most often occurs in the area of your lumbar spine called the pars interarticularis.

In most cases of spondylolytic spondylolisthesis, the pars fracture occurs during adolescence and goes unnoticed until adulthood. The normal disc degeneration that occurs in adulthood can then stress the pars fracture and cause the vertebra to slip forward. This type of spondylolisthesis is most often seen in middle-aged men.

Because a pars fracture causes the front (vertebra) and back (lamina) parts of the spinal bone to disconnect, only the front part slips forward. This means that narrowing of the spinal canal is less likely than in other kinds of spondylolisthesis, such as DS in which the entire spinal bone slips forward.

What are the symptoms of degenerative spondylolisthesis?

Patients with DS often visit the doctor's office once the slippage has begun to put pressure on the spinal nerves. Although the doctor may find arthritis in the spine, the symptoms of DS are typically the same as symptoms of spinal stenosis. For example, DS patients often develop leg and/or lower back pain. The most common symptoms in the legs include a feeling of vague weakness associated with prolonged standing or walking.

Leg symptoms may be accompanied by numbness, tingling, and/or pain that is often affected by posture. Forward bending or sitting often relieves the symptoms because it opens up space in the spinal canal. Standing or walking often increases symptoms.

What are the symptoms of spondylolytic spondylolisthesis?

Most patients with spondylolytic spondylolisthesis do not have pain and are often surprised to find they have the slippage when they see it in x-rays. They typically visit a doctor with low back pain related to activities. The back pain is sometimes accompanied by leg pain.

How is a spondylolisthesis diagnosed?

Doctors diagnose both DS and spondylolytic spondylolisthesis using the same examination tools.

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your back. This will include looking at your back and pushing on different areas to see if it hurts. Your doctor may have you bend forward, backward, and side- to-side to look for limitations or pain.

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

X-rays. These tests visualize bones and will show whether a lumbar vertebra has slipped forward. X-rays will show aging changes, like loss of disc height or bone spurs. X-rays taken while you lean forward and backward are called flexion-extension images. They can show instability or too much movement in your spine.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This study can create better images of soft tissues, such as muscles, discs, nerves, and the spinal cord. It can show more detail of the slippage and whether any of the nerves are pinched.

Computed tomography (CT). These scans are more detailed than x-rays and can create cross-section images of your spine.

How is spondylolisthesis treated without surgery?

Although nonsurgical treatments will not repair the slippage, many patients report that these methods do help relieve symptoms.

Physical therapy and exercise . Specific exercises can strengthen and stretch your lower back and abdominal muscles.

Medication . Pain killers and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines may relieve pain.

Steroid injections . Cortisone is a powerful anti-inflammatory. Cortisone injections around the nerves or in the "epidural space" can decrease swelling, as well as pain. It is not recommended to receive these, however, more than three times per year. These injections are more likely to decrease pain and numbness, but will not relieve weakness of the legs.

When should someone with degenerative spondylolisthesis be treated with surgery?

Patients should consider surgery for degenerative spondylolisthesis if they have tried the nonsurgical treatments for 3 to 6 months with no improvement.

Before committing to surgery, your provider will take a close look at the extent of the arthritis in your spine and whether your spine has excessive movement.

DS patients who are candidates for surgery are usually not able to walk or stand, and have a poor quality of life due to the pain and weakness.

When should someone with spondylolytic spondylolisthesis be treated with surgery?

Patients should consider surgery for spondylolytic spondylolisthesis if they have tried the nonsurgical treatments for at least 6 to 12 months with no improvement.

If the slippage is getting worse or the patient has progressive neurologic symptoms, such as weakness, numbness, or falling, and/or symptoms of cauda equina syndrome, surgery may help.

How is spondylolisthesis treated with surgery?

Surgery for both DS and spondylolytic spondylolisthesis includes removing the pressure from the nerves and spinal fusion.

Removing the pressure involves opening up the spinal canal. This procedure is called a laminectomy. Spinal fusion is essentially a "welding" process. The basic idea is to fuse together the painful vertebrae so that they heal into a single, solid bone.

Departments and Programs Who Treat This Condition

Spine surgery.

Popular Services

- Patient & Visitor Guide

Committed to improving health and wellness in our Ohio communities.

Health equity, healthy community, classes and events, the world is changing. medicine is changing. we're leading the way., featured initiatives, helpful resources.

- Refer a Patient

Spondylolisthesis

We design a unique treatment plan for your condition of spondylolisthesis and take into account your life goals., what is spondylolisthesis.

Low back pain, leg pain and weakness in the legs can happen if the bone that’s out of position significantly narrows the spinal column and begins to press on nerves.

Causes of spondylolisthesis

- Birth defect of the vertebral joint – This usually occurs in the lower spine where the lumbar spine and sacrum come together

- Stress “micro-fracture” in the bone due to overstretching and overuse – This can occur with sports activities such as gymnastics, weight lifting, ice skating and football

- Aging or overuse-related wear on the spinal joints

Rest and anti-inflammatory medication resolve most cases.

If it’s more severe, you may need physical therapy or surgery.

Spondylolisthesis grades

Doctors commonly describe spondylolisthesis as either high-grade or low-grade, depending on how severe your condition is. Grades are from 1 to 4.

- Low-grade (grade 1 and grade 2) usually occurs in adolescents and is considered less severe. Low-grade doesn’t typically require surgery.

- High-grade (grade 3 and grade 4) may require surgery if you’re experiencing severe pain.

The grade of your condition is based on how far away from proper alignment your spine has become.

Spondylolisthesis symptoms

In many cases, people who have spondylolisthesis don’t have any symptoms. You may not be aware you have the condition until an X-ray is taken for an unrelated reason. If you do have symptoms, the most common are:

- Lower back pain that feels like a muscle strain

- Muscle spasms or tightness in your hamstring

- Lower back pain that worsens with activity and improves with rest

- Difficulty walking or standing

- Pain when bending over

- Stiffness in your back

- Pain extending down from your lower back to your thighs

If you have high-grade spondylolisthesis, you may experience tingling, numbness or weakness in one or both legs.

Diagnosing spondylolisthesis

Following a thorough medical history, physical and neurological exams, our spine surgeons may recommend any of the following tests to confirm whether a bone in your spine is out of alignment. All tests are available at Ohio State Spine Care :

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

- Electromyography (EMG) to test your muscles and nerves

Spondylolisthesis treatment

Ohio State’s Spine Care team has the benefit of extra expertise from treating many people with spondylolisthesis. Because of this, the Spine Care team, composed of orthopedic and neurological specialists, is uniquely qualified to determine whether you’re likely to benefit from nonsurgical treatment. We also recommend lifestyle changes to prevent future problems with your spine.

We offer treatments ranging from physical therapy to the most complex spine surgeries. Physicians, therapists and other care providers work together to provide you with options that increase mobility and reduce pain.

Most people who come to Ohio State Spine Care don’t require surgery.

Lifestyle changes

- Exercise, such as Pilates or yoga, to strengthen muscles in your back

- Quitting smoking

- Guidance on weight loss to reduce pressure on your spine

Nonsurgical treatments

- Physical therapy – We’ll work with you one-on-one to customize a treatment plan for your needs and goals

- Spine orthobiologics use substances in your body to activate the healing process naturally

- Wearing a back brace to limit spine movement

- Medication for pain management

Most people return slowly to full function, including athletic activity.

Spondylolisthesis surgery

You may need surgery if a spinal bone that has slipped is likely to cause damage to nerves and the surrounding spinal structure, or if it’s causing severe pain or muscle weakness in one or both legs.

Our surgeons can perform minimally invasive surgery to correct the symptoms of spondylolisthesis. The surgeon makes tiny incisions in the back and works through a tube to minimize skin and muscle damage, reduce blood loss and reduce postsurgical pain.

At Ohio State, we can use both minimally invasive surgery and conventional surgical techniques for these procedures:

- Decompression surgery (laminectomy) to remove part of the vertebra and relieve pressure on your spinal cord or nerves

- Spinal fusion surgery to fuse a severely slipped bone with the vertebra below it and restore stability to the spinal column

Most people who have decompression or fusion surgery can return to full function, including athletic activities.

Ohio State conducts innovative research in the laboratory, as well as through clinical trials.

Those who have a pinched nerve may be eligible to participate in one of the following areas of research at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

Biomechanical testing: We’re doing biomechanical testing to assess the spine before and after surgery. A specialized vest helps us assess your spinal movement and measure the effectiveness of surgery. It ultimately may provide valuable information about which treatment methods will best increase mobility and function of the spine.

Back pain consortium: We’re members of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM). Membership in this elite organization allows us to engage with other top U.S. medical centers in global research studies on back pain. As we measure our results against established international standards, we share best practices and elevate our standard of care.

Enroll in a clinical trial

- Learn more about spine care at Ohio State Download our guide

Patient Education Animation Library

How would you like to schedule.

Don’t have MyChart? Create an account

Subscribe. Get just the right amount of health and wellness in your inbox.

Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is where one of the bones in your spine, called a vertebra, slips forward. It can be painful, but there are treatments that can help.

It may happen anywhere along the spine, but is most common in the lower back.

Check if you have spondylolisthesis

The main symptoms of spondylolisthesis include:

- pain in your lower back, often worse when standing or walking and relieved when sitting or bending forward

- pain spreading to your bottom or thighs

- tight hamstrings (the muscles in the back of your thighs)

- pain, numbness or tingling spreading from your lower back down 1 leg ( sciatica )

Spondylolisthesis does not always cause symptoms.

Spondylolisthesis is not the same as a slipped disc . This is when the tissue between the bones in your spine pushes out.

Non-urgent advice: See a GP if:

- you have lower back pain that does not go away after 3 to 4 weeks

- you have pain in your thighs or bottom that does not go away after 3 to 4 weeks

- you're finding it difficult to walk or stand up straight

- you're worried about the pain or you're struggling to cope

- you have pain, numbness and tingling down 1 leg for more than 3 or 4 weeks

What happens at your GP appointment

If you have symptoms of spondylolisthesis, the GP may examine your back.

They may also ask you to lie down and raise 1 leg straight up in the air. This is painful if you have tight hamstrings or sciatica caused by spondylolisthesis.

The GP may arrange an X-ray to see if a bone in your spine has slipped forward.

You may have other scans, such as an MRI scan , if you have pain, numbness or weakness in your legs.

Treatments for spondylolisthesis

Treatments for spondylolisthesis depend on the symptoms you have and how severe they are.

Common treatments include:

- avoiding activities that make symptoms worse, such as bending, lifting, athletics and gymnastics

- taking anti-inflammatory painkillers such as ibuprofen or stronger painkillers on prescription

- steroid injections in your back to relieve pain, numbness and tingling in your leg

- physiotherapy to strengthen and stretch the muscles in your lower back, tummy and legs

The GP may refer you to a physiotherapist, or you can refer yourself in some areas.

Waiting times for physiotherapy on the NHS can be long. You can also get it privately.

Surgery for spondylolisthesis

The GP may refer you to a specialist for back surgery if other treatments do not work.

Types of surgery include:

- spinal fusion – the slipped bone (vertebra) is joined to the bone below with metal rods, screws and a bone graft

- lumbar decompression – a procedure to relieve pressure on the compressed spinal nerves

The operation is done under general anaesthetic , which means you will not be awake.

Recovery from surgery can take several weeks, but if often improves many of the symptoms of spondylolisthesis.

Talk to your surgeon about the risks and benefits of spinal surgery.

Causes of spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis can:

- happen as you get older – the bones of the spine can weaken with age

- run in families

- be caused by a tiny crack in a bone (stress fracture) – this is more common in athletes and gymnasts

Page last reviewed: 01 June 2022 Next review due: 01 June 2025

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.

Alan G. Shamrock ; Chester J. Donnally III ; Matthew Varacallo .

Affiliations

Last Update: August 7, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Spondylolysis refers to a posterior defect in the vertebral body at the pars interarticularis. Usually, this defect is due to trauma or from a chronic repetitive loading and hyperextension. If this instability results in translation of the vertebral body, spondylolisthesis has occurred. This process requires a fracture or deformation of the posterior spine elements creating an elongation of the pars. This condition occurs in all ages with the underlying cause varying based on the age group. This activity describes the pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of lumbar spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for affected patients.

- Identify the different types of spondylolisthesis, differentiating the patholological features that distinguish each variety.

- Outline the components of a proper evaluation and assessment of a patient presenting with lumbar spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis, including any indicated imaging studies.

- Describe management strategies for spondylolisthesis, based on which variant of the condition with which the patient presents.

- Review the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with lumbar spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis.

- Introduction

Spondylolysis refers to a posterior defect of the vertebral body occurring at the pars interarticularis. [1] Typically, this defect results from trauma or chronic repetitive loading and hyperextension. If this instability leads to translation of the vertebral body, this is spondylolisthesis. [1] [2] This process requires either a fracture or deformation of the posterior spinal elements resulting in elongation of the pars interarticularis. This condition can potentially occur in all age groups, with the underlying cause varying based on age. If the slip progresses to the point of neurologic compromise, then surgical intervention may be necessary to decompress and stabilize affected segments. [3] Absent any motor deficits, a nonoperative course of analgesia, activity modification, and injections should be the initial therapeutic approach for several months. [4]

Isthmic spondylolisthesis refers to a defect within the pars interarticularis usually from repetitive microtrauma and accounts for the vast majority of cases in children and adolescents. [1] [5]

Degenerative spondylolisthesis is the most common form of spondylolisthesis seen in adults. [6] It is due to chronic degenerative changes at the posterior elements resulting in the incompetence of the surrounding ligamentous structures, leading to elongation and slippage. [6]

Acutely, a traumatic spondylolisthesis can occur following a high-energy injury flexion/extension that causes a fracture-dislocation at the posterior elements. [7]

Another type is dysplastic spondylolisthesis which is a result of an abnormal formation of the posterior elements resulting in this subsequent instability. [8]

- Epidemiology

The rates of spondylosis and spondylolisthesis vary widely by age group. In the pediatric population, spondylosis is present in about 5% of the population, most commonly (90%) at the L5 to S1 motion segment, although pathology at L4 is more likely to be symptomatic. [1] [9] Long-term studies estimate that about 15% of those with a defect (spondylosis) will develop a slip (spondylolisthesis). [10] [11] Regarding adults, lumbar spondylolisthesis without a defect in the pars is present in 5% of men, 10% of women. [12] It is not always symptomatic. This degenerative type usually occurs at the L4 to L5 levels (versus isthmic noted at L5 to S1). [6] Degenerative spondylolisthesis is an acquired type of spondylolisthesis occurring much more frequently and gradually in the adult population. [6] Cohorts with degenerative spondylolisthesis will rarely develop a high-grade spondylolisthesis. [13] Furthermore, the chronic natural history of this disease process is such that with further degenerative changes, the vertebral segments may eventually stabilize, and the patients can have subsequent clinical improvements. [13]

- Pathophysiology

Repetitive micro-traumas from hyperextension lead to elongated or absent pars interarticularis. This force applies additional stress to the facet joints and subsequent hypermobility leading to advanced degeneration of the disc space. [14] The reduced disc and facet stability results in the translation of the vertebral body, creating a stenotic effect on the exiting nerve roots and/or the spinal canal. In the traumatic setting, flexion-distraction energy may cause a localized vertebral body failure at this segment, predisposing the patient to chronic issues if instability develops.

- History and Physical

Initial evaluation of lower back pain initiates by obtaining a history from the patient. This history should pertain to the timeline of pain, radiation of pain, and inciting events. The clinician should pay careful attention to prior episodes of trauma. Low-grade slips and stenotic spinal canals may decompress and relieve pain with leaning forward or sitting. It is crucial to note patient comments such as decreased pain with pushing a grocery cart or walking upstairs as both common actions have the spinal column in forwarding flexion. [15] It is also important in any evaluation of extremity issues to inspect circulation as vascular claudication may mirror or mimic the neurogenic problems.

Classically patients may complain of pain radiating down both buttocks and lower extremities. An evaluation of the patient's walking is also critical to better assess the daily impact that pain or neurological deficits cause. All physical examinations will include assessing the neurologic function of the arms, legs, bladder, and bowels. The keys to a thorough exam are organization and patience. One should evaluate not only strength but also sensation and reflexes. It is also essential to inspect the skin along the back and document the presence of tenderness to compression or palpable step-off.